Abstract

The SDG 15.3.1 framework provides a standardized approach using land use/land cover (LULC) change, land productivity, and soil organic carbon (SOC) dynamics to assess land degradation. However, SDG 15.3.1. faces limitations like coarse resolutions of Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2, particularly for fine-scale studies. Accordingly, this paper integrates Very Deep Super-Resolution (VDSR) for downscaling Landsat-8 imagery to 1 m resolution and the Vegetation Health Index (VHI) into SDG 15.3.1 to enhance detection in the heterogeneous Loiret region, France—a temperate agricultural hub featuring mixed croplands and peri-urban interfaces—using 2017 as baseline and 2024 as target. Results demonstrated that 1 m resolution detected more degraded LULC areas than coarser scales. SOC degradation was minimal (0.15%), concentrated in transitioned zones. VHI reduced overestimation of productivity declines compared to the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index by identifying more stable areas and 2.69 times less degradation in integrated assessments. The “One Out, All Out” rule classified 2.6% (using VHI) and 7.1% (using NDVI) of the region as degraded, mainly in peri-urban and cropland hotspots. This approach enables metre-scale land degradation mapping that remains effective in heterogeneous landscapes where fine-scale LULC changes drive degradation and would be missed at lower resolutions. However, future ground validation and longer timelines are essential to enhance the presented methodology.

1. Introduction

Land degradation, characterized by the persistent decline in soil and vegetation productivity [1], represents a critical global challenge that undermines agriculture [2] and ecosystem services, thereby affecting sustainable development [3]. Globally, the erosion of 75 billion tons of soil each year imposes around $400 billion annual global losses, equivalent to about $70 per person per year [4]. As of 2023, at least 100 million hectares are degraded yearly [2]. Crop yields, soil fertility, ecosystem services, water availability, and biodiversity are particularly threatened by land degradation with far-reaching consequences [5]. Agriculture claims at least 40% of Earth’s land surface, with more than half of farmed lands already degraded [6]. According to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification’s (UNCCD) first-ever Financial Needs Assessment (2024) [7], 1 billion USD are and will be required daily between 2025 and 2030 to restore degraded lands and build resilience. From an investment point of view, 2.6 trillion USD will be needed by 2030 to address ecosystem service restoration [7]. Therefore, combatting land degradation requires advanced monitoring tools to inform sustainable land management and ensure agricultural resilience.

Despite its devastating impacts, means for objectively measuring the extent and severity remains one of the biggest and most urgent challenges [8]. Conceptually, SDG 15.3.1 defines land degradation as: “The reduction or loss of the biological or economic productivity and complexity of rain-fed cropland, irrigated cropland, or range, pasture, forest, and woodlands resulting from a combination of pressures, including land use and management practices” [9,10]. Here, “biological productivity and complexity” refers to ecosystem health metrics like vegetation vigour and biomass accumulation, while “economic productivity and complexity” encompasses sustained yield potential and functional resilience.

This framework provides a standardized approach to assess land degradation globally, employing three sub-indicators: land use/land cover (LULC) change [11], land productivity via the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) trends for tracking vegetation productivity [12], and soil organic carbon (SOC) dynamics [13]. Supported by the UNCCD, this framework leverages remote sensing data from LANDSAT (30 m resolution) and Sentinel-2 (10 m resolution) to map degradation globally and regionally. Complementary frameworks, such as UNCCD’s Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) [14] and Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) soil health assessments [15], integrate remote sensing with ground observations to guide restoration efforts. These tools enable policymakers to identify degradation hotspots, supporting targeted interventions.

The three sub-indicators of SDG 15.3.1 were selected by the UNCCD to balance scientific robustness with global applicability using Earth observation data [7]. LULC change detects persistent human-induced conversion (e.g., cropland to built-up) [16]. Land productivity dynamics act as a sensitive early-warning proxy for declining biological and economic productivity [16]. SOC stock change captures long-term soil degradation. The conservative “One Out, All Out” integration rule ensures that any negative signal in a single sub-indicator triggers a degraded classification [17]. This method prioritizes precautionary policy action toward achieving LDN at national and global scales. However, despite the robustness of SDG 15.3.1, significant limitations hinder its ability to capture fine-scale degradation [18], particularly in heterogeneous agricultural landscapes. Some of the limitations are conceptual, such as the oversimplification of land degradation [19], considering land degradation a static process, and limited representations. Other limitations are technical and have subsequent implications on methodological applications. The majority of technical limitations stem from those related to remote sensing. In this paper, the focus will be on the latter.

Accordingly, the purpose of this study is to address SDG 15.3.1’s limitations for temperate, heterogeneous landscapes [13,20] by integrating advanced remote sensing techniques. For that purpose, the Loiret region will be used as a case study to test the efficacy of the proposed method for detecting fine-scale degradation patterns. This study fully respects this global design and reporting logic: the exact same three sub-indicators were retained, the same transition matrices for LULC were used, the same SOC stock-change factors were applied, and the identical integration rule was followed.

The proposed enhancements (1 m Very Deep Super-Resolution (VDSR)-downscaled imagery for LULC classification and substitution of NDVI with VHI for the productivity sub-indicator) operate exclusively within the official methodological boundaries. They also increase spatial detail to provide more detailed representations of land degradation. The “One Out, All Out” integration rule was applied across LULC change, productivity trends (2017–2024), and SOC dynamics (baseline 2017 to target 2024) to produce an enhanced degradation map. Accordingly, the resulting degradation map can offer policymakers more precise hotspot delineation for targeted restoration, soil conservation measures, and agri-environmental scheme allocation. By enhancing spatial resolution (VDSR) and incorporating thermal stress information (VHI), an attempt to develop further the remote sensing angle of SDG 15.3.1 is proposed.

Based on the above-mentioned elements, this study aims to address the two following aspects:

- The resolutions of Landsat (30 m) and Sentinel-2 (10 m) are not fine enough to detect subtle changes linked to land use pressure.

- Integrating the Vegetation Health Index (VHI) can provide complementary insights into land productivity assessments and might offer finer findings compared to the use of NDVI alone.

For this purpose, machine learning (ML) techniques such as Random Forest (RF) [21] and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [22] were used to improve classification accuracy and degradation mapping. This was performed by integrating multi-temporal and multi-spectral data. However, achieving a higher resolution remains challenging, as most satellite datasets are constrained by native resolutions [23]. Super-resolution and advanced vegetation indices offer promising solutions to these challenges. VDSR models leverage deep learning to enhance satellite imagery resolution [24], outperforming traditional interpolation methods like bicubic or pansharp [25]. Moreover, they enable downscaling of Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 imagery to allow fine-scale detection of degradation patterns. Similarly, VHI, by integrating the Vegetation Condition Index (VCI) and Temperature Condition Index (TCI), provides a more comprehensive assessment of vegetation health than NDVI [26]. Despite these advancements, integrating super-resolution and VHI into SDG 15.3.1 frameworks remains underexplored, particularly in mixed agricultural landscapes [27]. To test the potential of these advancements, two hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1:

Spatial downscaling to 1 m resolution will detect more degraded LULC areas than coarser resolutions (30 m and 10 m) by better capturing heterogeneous transitions in mixed agricultural landscapes.

Hypothesis 2:

The use of VHI will reduce overestimation of productivity declines compared to NDVI by incorporating thermal moderation, leading to more accurate identification of stable vs. degraded areas.

These hypotheses drive the exploration of advanced remote sensing and ML to address spatial and methodological limitations, contributing to the development of the SDG 15.3.1 framework and more globally to land degradation mapping. The added value of the proposed methodology lies in its replicability, enabling metre-scale land degradation mapping in heterogeneous landscapes.

2. Materials and Methods

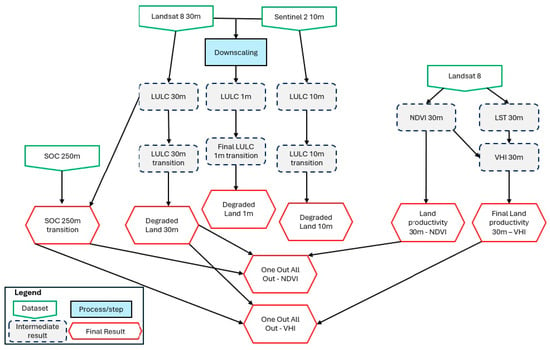

This section outlines the methodological framework for assessing land degradation in the Loiret region. The proposed method articulates the integration of remote sensing data, processing, index calculations, and SDG 15.3.1 sub-indicator analyses. The approach leverages advanced techniques such as VDSR downscaling and VHI computation to enhance spatial resolution. The full workflow, from data acquisition to integrated assessment, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the full study workflow, illustrating data processing, sub-indicator calculations, and integration steps.

2.1. Study Area

The Loiret region, located in north-central France along the Loire River, spans approximately 6775 km2 and presents diverse landscapes and mixed land use. The analysis using the NASA SRTM Digital Elevation Model 30 m [28] showed the region’s predominantly flat terrain. An ERA5 [29] analysis showed a mild continental climate with oceanic influence, featuring an average annual temperature of 11 °C and annual precipitation of approximately 640 mm. This climate, with distinct seasonal shifts, supports a rich agricultural landscape, characterized by fertile soils [30]. While global land degradation often manifests in drylands through desertification and drought-induced productivity losses, temperate regions like the Loiret department in north-central France face distinct pressures [31]. The region’s agricultural landscape faces degradation pressures from nutrient leaching and decline in organic matter, particularly in peri-urban fringes where urban expansion fragments habitats [32]. This makes the Loiret region a suitable area for studying land degradation and its impact on agricultural productivity in temperate regions.

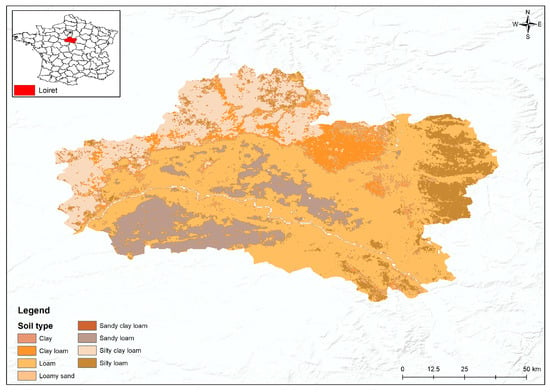

The soil texture (Figure 2) in the Loiret region is diverse. As part of this study, a spatial analysis was conducted in 2025 using zonal statistics in Google Earth Engine (GEE) [33] (Google Inc., 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA, USA) on the OpenLandMap dataset [30]. This analysis revealed loam as the predominant texture, covering approximately 3373 km2 (49.8% of the total area), followed by silty clay loam at 1206 km2 (17.8%), sandy loam at 863 km2 (12.7%), silt loam at 695 km2 (10.3%), clay loam at 637 km2 (9.4%), and a negligible area of sandy clay loam at 2 km2 (0.03%). In terms of susceptibility to land degradation, medium-textured soils like silt loam and silty clay loam are most vulnerable due to their high silt content. This susceptibility promotes poor aggregate stability and facilitates detachment by water runoff [34]. Sandy loams, while less extensive, are additionally susceptible to wind erosion in exposed, low-residue crop systems [35].

Figure 2.

Description of the study area, highlighting the distribution of different soil characteristics/classes of the Loiret region in France. Scale: 1:750,000. Source: Spatial data from Landsat-8 and soil texture [30], processed in GEE.

2.2. Datasets

The datasets used in this study, along with their characteristics, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the utilized datasets in this study.

2.3. Downscaling LANDSAT Imagery

LANDSAT images are originally provided at a resolution of 30 m, often not sufficient for fine-scale land degradation mapping [11]. To achieve a spatial resolution of 1 m for Landsat-8 bands, a VDSR model was implemented. The approach exploited the spatial relationship between Landsat-8 (30 m) and Sentinel-2 (10 m) corresponding bands. A scaling factor of 3 (30 m ÷ 10 m) was used, as it enables iterative downscaling to finer resolutions. Corresponding bands (e.g., Landsat-8 Red Band 4 with Sentinel-2 Red Band 4) were paired to ensure spectral consistency and minimize temporal discrepancies. Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 band images were preprocessed in GEE for quality and compatibility, including min–max normalization to [0, 1] and padding for convolutional operations.

The VDSR-29 model, implemented using TensorFlow’s Keras API (version 2.20.0), was designed to downscale Landsat-8 bands to 1 m resolution by fusing with higher-resolution Sentinel-2 bands as spatial guidance. The architecture comprised 29 convolutional layers: an initial layer with 64 filters (1 × 1 kernel, ReLU activation), followed by 28 layers organized into 14 blocks (each consisting of two 1 × 1 convolutions with batch normalization and ReLU activation). Filter counts progressively increased across blocks from 64 to 512 and interspersed with three max-pooling layers (kernel = 1 × 1) for feature extraction. The process was topped with a sub-pixel convolution upsampling module (×3 factor) to reconstruct the final high-resolution output. A skip connection added the bicubic-upsampled Landsat-8 input to the residual output. This enhances training stability and preserves low-frequency spectral details from Landsat-8 while incorporating Sentinel-2’s structural priors. For each band pair, training data were generated by extracting 512 × 512 pixel patches from co-registered Landsat-8 (30 m input to simulate low resolution) and Sentinel-2 (10 m to simulate high resolution). Stride was set to 128 and a maximum of 25,000 patches to balance computational efficiency and data representation. The patch dataset was split into 80% training and 20% validation sets with a random state of 42 for reproducibility. The model was trained separately for each spectral band to capture band-specific characteristics. The model used the Adam optimizer and mean squared error loss augmented with perceptual loss for realism. Training ran for 25 epochs, with early stopping (patience = 5, monitoring validation loss) and learning rate reduction (factor = 0.5, patience = 4), to prevent overfitting and optimize performance.

Downscaling of Landsat was conducted iteratively in three stages (30 m to 10 m, 10 m to 3.33 m, and 3.33 m to 1.11 m) for each band. This leveraged the trained VDSR model to progressively enhance resolution, followed by a final interpolation step to reach 1 m. Patches were reconstructed into a seamless image with overlapping regions normalized by averaging contribution counts to ensure smooth transitions. Each 1 m band image was saved as a GeoTIFF file, preserving geospatial metadata from the original Landsat-8 image. This process was repeated for each band (Red, Blue, Green, NIR, SWIR), producing a set of high-resolution bands suitable for detailed spectral and spatial analysis.

This iterative downscaling approach enhanced the spatial resolution of Landsat-8 bands, leveraging the VDSR model’s ability to learn fine-scale details from Sentinel-2 data.

2.4. Calculation of Environmental Indices in Google Earth Engine

LST was corrected to ensure accurate representation of surface thermal conditions. This step is essential for deriving the TCI and VHI used in assessing vegetation stress. LST correction is based on methodology outlined in [36], applying specific corrections to the Landsat-8 thermal band (Band 10) before implementing the regression-based approach. Corrections included the following:

- Cloud Masking: Clouds were masked using ee.Algorithms.Landsat.simpleCloudScore with a 10% threshold, excluding contaminated pixels via ee.Image.updateMask.

- Emissivity Correction: Surface emissivity was estimated from 1 m NDVI-derived fractional vegetation cover (FvF_vFv).

- Local Time Difference Correction: Solar declination angle (δ\deltaδ) was adjusted for local time based on longitude and acquisition timestamp.

- Cosine of Zenith Angle: Solar zenith angle cosine (cos(θz)\cos(\theta_z)cos(θz)) was calculated to account for illumination effects.

- Zenith Angle Correction for Flat Surfaces: Applied uniformly using solar zenith angle.

- Solar Zenith Angle: Integrated into the radiative transfer model to adjust for solar radiation.

The next step involved calculating the NDVI using the difference between the near-infrared and red bands.

NDVI: Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

NIR: Near-infrared band

Red: Red band

VHI, comprising TCI and VCI, was calculated using the following:

VCI: Vegetation Condition Index

NDVI: Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

TCI: Temperature Condition Index

LST: Land Surface Temperature

VHI: Vegetation Health Index

For VCI and TCI computations, the “historical” maxima and minima were derived from the full multi-year study period collection (2017–2024) of seasonal median images. This step was performed to determine the typical range of seasonal variability across the study period. This allows the comparison of VCI and TCI values against a series of observed values rather than a single reference year. Specifically, for each pixel and season, NDVI_max/min and LST_max/min represented the 95th/5th percentiles across the 8-year series. The choice of median values mitigates outlier influences from extreme weather while capturing inter-annual variability or sensor issues.

However, while using multi-year seasonal medians for VCI and TCI reduces outlier effect, this approach has several limitations. For instance, it can mask short-term or subtle changes and may undermine the impact of extreme and rapid onset weather events. Seasonal aggregation also reduces temporal resolution, limiting the detection of short-lived stress episodes. Nonetheless, the proposed method reduces short-term noise while capturing “observed” seasonal and inter-annual variability in vegetation and temperature conditions that can be used for comparison. VHI was then computed annually by using the median seasonal values, ensuring alignment with SDG 15.3.1’s focus.

These indices collectively support land degradation assessment by linking biophysical changes to SDG 15.3.1 sub-indicators like land productivity and soil health [16]. The calculations used the Landsat-8 bands at 30 m resolution for the purpose of comparing between LD using NDVI and VHI.

2.5. Calculation of Land Degradation Following SDG 15.3.1 Framework

To capture temporal variation in land cover and productivity over the annual/seasonal cycles, all sub-indicator analyses incorporated multi-temporal composites. For LULC change (sub-indicator 1), this entailed computing annual median reflectance (detailed in 2.5.1), stacked as input features to the classifier for phenology-robust mapping. SOC change (sub-indicator 2) used static baseline-to-target transitions, as soil carbon responds more slowly to annual variability. Productivity dynamics (sub-indicator 3) similarly relied on seasonal medians for trend detection (detailed in Section 2.5.3). This approach aligns with SDG 15.3.1’s emphasis on persistent signals while accommodating Loiret’s dynamic landscapes.

2.5.1. Sub-Indicator 1: Land Use and Land Cover Changes

In the SDG 15.3.1 framework, land degradation is assessed through LULC change as a proxy for persistent human-induced alterations that reduce ecosystem productivity [11]. This transition focuses on transitions from natural or semi-natural land cover (e.g., forest, grassland) to less productive or artificial states (e.g., bare soil, built-up areas). This shift often implies changes in land use from conservation or agriculture to intensive exploitation or abandonment [37]. LULC analysis enables scalable detection of transitions via standardized matrices (e.g., UNCCD transition rules classifying forest-to-urban as degrading) [16]. For this study, LULC was operationalized by using a nine-class typology adapted from the Google Dynamic World near-real-time dataset [38] (water (1), trees (2), grass (3), flooded vegetation (4), crops (5), shrub and scrub (6), built (7), bare (8), and snow and ice (9)). Classes “snow and ice” (9), “water” (1), and “flooded vegetation” (4) were excluded from the transition and degradation analysis because (i) permanent snow and ice do not exist in the Loiret region, (ii) major water bodies showed no detectable change between 2017 and 2024, and (iii) flooded vegetation corresponds mainly to protected wetlands and marsh-like areas of the Loire Valley with stable extent over the study period [39]. This emphasizes cover attributes detectable in multi-spectral imagery, ensuring direct comparability with global SDG 15.3.1 reporting.

LULC classifications for 2017 (baseline) and 2024 (target year) were generated for the study area at 30 m (Landsat-8), 10 m (Sentinel-2), and 1 m (downscaled VDSR) resolutions. For each year, all the available cloud-free Landsat-8 Surface Reflectance (Tier 1) scenes covering the Loiret region throughout the entire year (January–December) were used. After cloud/cloud-shadow masking (<10% cloud cover per scene and additional pixel-level QA masking), the median reflectance value per band was calculated separately. These five median composites (Blue, Green, Red, NIR, SWIR bands) were stacked and fed into a single supervised Random Forest classifier (ee.Classifier.smileRandomForest, 150 trees, max depth 25). This multi-year approach strongly reduces the influence of short-term cloud contamination and extreme seasonal vegetation states (e.g., bare soil in winter vs. peak greenness in summer). This method provides a robust and balanced representation of each land cover class. However, shifting patterns of seasonal or overall cloud cover under climate change would require measures to avoid bias linked to changes in times and periods of visibility—or even in some cases in which parts of a region are affected by these changes.

To train the RF classifier, a dataset of 25,000 points was sampled across the region using stratified random sampling. Points were distributed proportionally across the nine classes based on their spatial extent in the dataset for 2017. The dataset was split into 80% for training and 20% for validation. For each resolution and year, LULC rasters were generated by applying the trained RF classifier to the respective imagery and indices. The methodology identifies degraded, improved, and stable areas by classifying LULC transitions:

- From natural to artificial land cover (e.g., forest to urban);

- From natural vegetation to less vegetated states (e.g., forest to grassland or bare land).

Positive changes, such as grassland to forest, are also considered. The analysis was conducted in GEE to leverage its computational efficiency and geospatial data handling capabilities.

The transition analysis was achieved by adding the 2017 LULC raster (multiplied by 100 to encode the “from” class) to the 2024 LULC raster (encoding the “to” class), resulting in a transition. The transition codes were classified into three categories based on their impact on land degradation (Table 2):

Table 2.

Land cover transitions and correspondence to land degradation classes as per SDG 15.3.1 framework. (Note: Classes “snow and ice”, “water”, and “flooded vegetation” were omitted from the transition matrix because they either do not occur permanently or exhibited no detectable change during the study period in the Loiret region).

- Degraded: Transitions indicating a loss of natural cover or ecosystem function, such as trees to grass {203}, trees to built {207}, or crops to bare {508}.

- Improved: Transitions reflecting positive changes, such as grass to trees {302} or bare to crops {805}.

- Stable: Transitions where the land cover remained unchanged (e.g., trees to trees {202}) or involved no significant degradation or improvement (e.g., water to water {101}).

The transition image was remapped, assigning values of −1 (degraded), 0 (stable), and 1 (improved) based on the predefined transition lists. To quantify the extent of degradation, improvement, and stability, the area of each class was calculated in ha.

Land cover change analysis and transition-based degradation mapping were performed over the entire Loiret region at all three resolutions (30 m, 10 m, and 1 m). Four representative zoomed-in zones were subsequently selected for detailed visual comparison and illustration in the results. Selection criteria for these zones were as follows:

- Presence of clear land cover transitions between 2017 and 2024;

- Mixture of degradation and improvement signals;

- Representation of typical peri-urban, intensive agricultural, and forest landscapes of the Loiret.

These four zones are, therefore, illustrative examples only; all quantitative results reported in the study (area statistics, percentages, and final integrated degradation maps) refer to the full regional extent.

2.5.2. Sub-Indicator 2: Soil Organic Carbon Changes

To complement the LULC degradation assessment, the SOC change analysis was performed using the original OpenLandMap soil organic carbon dataset [40] at its native 250 m spatial resolution. Although several downscaling approaches (bilinear, bicubic, and machine-learning-based) were tested to bring the SOC stock and change layers to finer resolutions (30 m, 10 m, and 1 m), all the attempts produced considerable spatial artefacts and large uncertainties.

SOC loss was calculated for the period of 2017–2024 by analyzing LULC transitions from baseline (2017) to target (2024), focusing on pixels where land cover changed. IPCC climate regions were incorporated to account for the influence of temperature and precipitation on SOC dynamics, using climate-specific stock change factors to estimate SOC changes due to LULC transitions. Climate-specific stock change factors (f), as provided in the UNCCD Good Practice Guidance [16], were applied to estimate SOC changes for each LULC transition.

These factors reflect the expected proportional change in SOC stocks after a land cover change, assuming a 20-year equilibrium period. SOC loss or gain for each transitioned pixel was calculated as follows: The baseline SOC content (g/kg) was converted to SOC stock (tC/m2) using soil bulk density [41] and pixel area (62,500 m2). The target SOC stock for 2024 was estimated by multiplying the baseline SOC stock by the climate-specific stock change factor (f), scaled linearly for the 7-year period (2017–2024) using a factor of 7/20 (since UNCCD assumes equilibrium after 20 years). Pixels with a SOC loss ≥ 10% were classified as degraded (−1), a gain ≥ 10% as improved (+1), and changes between −10% and +10% as stable (0), aligning with UNCCD thresholds. The resulting SOC change map provides a spatially explicit estimate of carbon loss or gain (in g/m2) for each transitioned pixel, contributing to the LULC-based land degradation assessment by quantifying the impact of land cover changes on soil carbon stocks.

2.5.3. Sub-Indicator 3: Land Productivity Dynamics Analysis

To assess land degradation through land productivity dynamics, both the classical method using the NDVI and the advanced method using the VHI were implemented. This analysis was conducted at 30 m resolution covering the period from 2017 to 2024.

The analysis leverages the Mann–Kendall statistical test and Sen’s slope estimator to detect trends and quantify their magnitude, with inter-annual variability assessed via the coefficient of variation (CV). For each season, the median NDVI and VHI were computed across the filtered images. VHI values were normalized to the range [−1, 1] to standardize the data for trend analysis. The Mann–Kendall test was applied to compute the z-score (indicating trend significance and direction), while Sen’s slope was calculated to estimate the rate of change per year. Inter-annual variability was assessed by calculating the coefficient of variation (CV), defined as the standard deviation of the seasonal median NDVI or VHI divided by the mean, computed over the 2017–2024 period.

The methodology evaluates trends in NDVI and VHI during the different seasons to classify land productivity into five categories based on the z-score, slope, and CV, following the SDG 15.3.1 framework for land productivity dynamics. The classification criteria, determined empirically through analysis of the data distributions (e.g., histograms of z-score, slope, and CV), were applied consistently for both NDVI and VHI. The categories and criteria are as follows:

- Increasing: Significant positive trend (z-score > 0.5).

- Stable: No significant trend (absolute z-score < 0.5) with low variability (CV < 0.2).

- Stable but Stressed: No significant trend (absolute z-score < 0.5) with high variability (CV > 0.2), indicating potential land use stress.

- Declining Early: Negative trend (z-score < −0.5) with a weak slope (slope > −0.01), suggesting early signs of degradation.

- Declining Severe: Negative trend (z-score < −0.5) with a strong slope (slope < −0.01), indicating persistent degradation.

These thresholds (z-score = 0.5, slope = −0.01, CV = 0.2) were derived by inspecting the statistical distributions of the trend and variability metrics within the study area, ensuring applicability. The classification was implemented to evaluate the z-score, slope, and CV rasters, producing a productivity map with values ranging from 1 (increasing) to 5 (declining severe) and complementing land productivity dynamics analysis.

Seasons were defined using standard meteorological divisions to ensure consistency with global remote sensing practices and SDG 15.3.1 trend analyses: winter (DJF: December–February), spring (MAM: March–May), summer (JJA: June–August), and autumn (SON: September–November). These partitions capture key phenological phases in Loiret’s temperate climate, where the primary growing season spans approximately March to October for dominant rain-fed cereals. The growing season is followed by post-harvest bare or cover-cropped periods in winter. Regional cropping systems emphasize annual rotations to maintain soil fertility and mitigate pests. Perennials and agroforestry elements are less prevalent but targeted in peri-urban restoration efforts. While these practices introduce temporal heterogeneity (e.g., green cover in winter vs. bare fallow), the use of median composites per season mitigates short-term anomalies.

The seasonal and yearly NDVI and VHI outputs were used to compare land degradation dynamics across different seasons, identifying seasonal and yearly variations in productivity categories. Yearly NDVI and VHI were calculated to integrate with LULC analysis under the SDG 15.3.1 “One Out All Out” rule, combining land productivity trends with land cover data to determine overall land degradation status.

Complementing Land Productivity Dynamics Analysis

To further characterize the distributions of NDVI and VHI values across the image collection and inform threshold selection for productivity classification, histograms of pixel values were computed for each index using GEE’s ee.Reducer.histogram() function. The reducer was applied to the seasonal median NDVI and VHI collections (2017–2024) over the Loiret region, with a fixed bucket width of approximately 0.00195 (derived from the default scaling for the {−1, 1} range). This resulted in adaptive binning based on the data range, yielding 524 bins for VHI (range: −0.474 to 0.548) and 671 bins for NDVI (range: −0.536 to 0.773). Histograms were aggregated across all images in the collection to produce overall distributions, with frequencies rounded to integers for analysis. Statistical summaries (mean, median, standard deviation) and percentage breakdowns by value ranges (<0, 0–0.5, ≥0.5) were calculated to evaluate distribution shapes and differences between indices.

2.6. SDG 15.3.1’s One Out, All Out Approach

The “One Out, All Out” principle was applied using the full set of three official SDG 15.3.1 sub-indicators (land cover change, soil organic carbon change, and land productivity dynamics) simultaneously [16].

Two parallel integrated land degradation results were produced at 30 m resolution:

- LULC change (30 m) + SOC change (250 m) + Land Productivity Dynamics calculated using NDVI (30 m)

- LULC change (30 m) + SOC change (250 m) + Land Productivity Dynamics calculated using VHI (30 m)

This conservative approach (i.e., One Out, All Out) ensures that any pixel exhibiting degradation in at least one sub-indicator is classified as degraded, prioritizing the identification of areas at risk. Prior to integration, the yearly land productivity classifications (for both NDVI and VHI) were remapped from their 1–5 scale to the −1, 0, 1 scale to align with LULC and SOC sub-indicators. The remapping was as follows: increasing (1) to 1 (improved), stable (2) and stable but stressed (3) to 0 (stable), and declining early (4) and declining severe (5) to −1 (degraded). This remapping considers only significant declining trends as degradation while treating stressed but stable areas as non-degraded, consistent with UNCCD guidelines emphasizing persistent productivity loss [16].

The integration process was executed by aligning the output rasters from the land cover change, soil organic carbon, and yearly productivity analyses to a consistent spatial grid at 30 m resolutions. For each pixel, the final degradation status was determined by taking the minimum value, where a value of −1 (degraded) in any sub-indicator resulted in a degraded classification. A uniform value of 1 (improved) across all sub-indicators yielded an improved classification. The value 0 was classified as stable. This approach was applied separately for NDVI- and VHI-based productivity classifications to evaluate their relative sensitivity. The resulting land degradation maps provide a spatially explicit representation of degradation status across the Loiret region.

2.7. Model Validation, Error Analysis, and Sensitivity Tests

To validate the VDSR downscaling and RF LULC classification, performance metrics were compared against benchmarks from similar studies on Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 imagery. For VDSR, key metrics including Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) were produced. In our implementation, VDSR achieved an average PSNR of 28.5 dB, SSIM of 0.87, and RMSE of 0.035 across bands, outperforming bicubic interpolation (PSNR 24.2 dB, SSIM 0.82, RMSE 0.048) by 18% in PSNR and 7% in SSIM, consistent with reported improvements of 2–5 dB in satellite SR applications [42,43]. These metrics were evaluated on the 20% validation set, confirming enhanced detail reconstruction for 1 m outputs.

For the RF classifier (150 trees, max depth 25), overall accuracy (OA) was 94.5% and Kappa coefficient was 0.92 at 1 m resolution, compared to 91.2% OA and 0.88 Kappa at 30 m and 92.8% OA and 0.90 Kappa at 10 m, based on the 10% validation points, and this aligned with the literature benchmarks (e.g., 93–98% OA for Sentinel/Landsat RF LULC). A confusion matrix showed high accuracies (>90%) for key classes like crops and built areas, with minor confusion in transitional classes (e.g., grass vs. shrub). Error sources include temporal mismatches in Landsat–Sentinel pairing and atmospheric effects. Sensitivity tests varied VDSR epochs (20–30) and RF trees (100–200), showing <3% change in metrics, indicating robustness.

3. Results

Section 3 presents the outcomes of the land degradation assessment in the Loiret region, highlighting the impacts of spectral downscaling and VHI’s inclusion on detection accuracy. Findings include comparisons across resolutions for LULC changes, minimal SOC degradation, seasonal productivity dynamics via NDVI and VHI, and integrated degradation maps. These analyses demonstrate enhanced granularity and sensitivity, supporting the study’s contribution to SDG 15.3.1.

3.1. LULC Change Analysis at Different Resolutions

The LULC change analysis examined transitions between 2017 (baseline) and 2024 (target) across the Loiret region at 30 m (Landsat-8), 10 m (Sentinel-2), and 1 m (VDSR) resolutions. The complete LULC maps are not shown as separate figures because the primary focus of this study lies in the land degradation outcomes derived from LULC transitions rather than in the intermediate LULC products themselves. The analysis classified changes into degraded, stable, and improved categories based on predefined transition rules (Table 2), revealing how higher resolutions enhanced detection of fine-scale degradation patterns. In Loiret’s predominantly agricultural landscape, where farmland covers approximately 60% of the region and has undergone consolidation into larger operations (average 115 ha, higher than France’s 69 ha national average) [44], degraded transitions often reflect peri-urban pressures near Orléans.

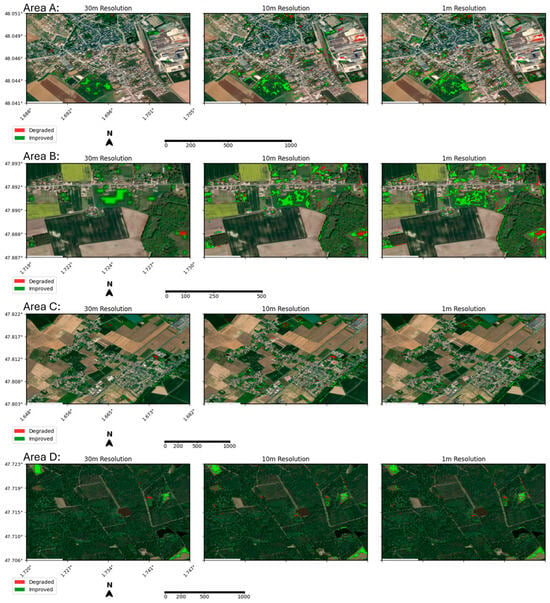

Figure 3 illustrated side-by-side comparisons of land degradation detection at the three resolutions for four zones, with colour-coded areas highlighting degraded (red), stable/no change (hidden), and improved (green) statuses. The 1 m resolution map showed greater detail in capturing small-scale transitions, such as localized urban expansion or field-level vegetation loss, which appeared blurred or aggregated at coarser resolutions. For instance, fragmented patches of degradation along field boundaries or within mixed land covers were more distinctly outlined at 1 m, providing better insights into processes that were not visible at 30 m or 10 m.

Figure 3.

Comparison of land degradation detection between 30 m, 10 m, and 1 m for four zones (Area A: Patay city, Area B: Les Caillots city, Area C: Baule city, Area D: forest near Villiers city. Scale: 1:5000. Source: Downscaled Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 imagery processed via VDSR and RF in GEE, using a Google Earth image as a background.

Table 3 summarizes the areas (in ha) classified as degraded, stable, and improved for each zone and resolution. At 1 m resolution, degraded areas totaled 6.4 ha in Zone 1, 5.4 ha in Zone 2, 10.6 ha in Zone 3, and 8.4 ha in Zone 4. Stable areas dominated across all zones, ranging from 261.1 ha (Zone 3) to 821.6 ha (Zone 1). Improved areas were smaller, such as 19.5 ha in Zone 1 and 2.3 ha in Zone 3. In comparison, at 10 m resolution, degraded areas were lower: 4.1 ha (Zone 1), 3.7 ha (Zone 2), 9.9 ha (Zone 3), and 5.7 ha (Zone 4). At 30 m, degraded areas were the smallest: 0.6 ha (Zone 1), 1.0 ha (Zone 2), 8.7 ha (Zone 3), and 0.8 ha (Zone 4). Comparisons across resolutions highlighted increases in detected degraded areas at higher resolutions. For Zone 1, the 1 m resolution detected approximately 10.6 times more degraded area than 30 m (6.4 ha vs. 0.6 ha), representing a 957% increase, and 1.57 times more than 10 m (a 57% increase). In Zone 3, the largest degraded zone, 1 m identified 1.22 times more than 30 m (a 22% increase) and 1.08 times more than 10 m (an 8% increase). Improved areas also increased at finer resolutions; for example, in Zone 1, 1 m detected 1.75 times more than 30 m (a 75% increase). These patterns indicated that coarser resolutions underestimated transitions, aggregating small, degraded patches into stable categories.

Table 3.

Areas (ha) classified as degraded, stable, and improved across four zones at 1 m, 10 m, and 30 m resolutions (2017–2024).

3.2. SOC Change Analysis

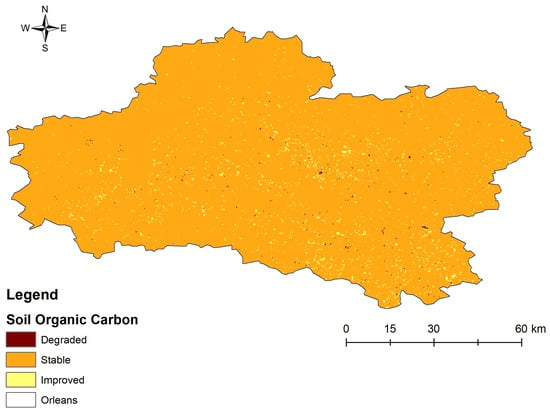

The SOC change analysis quantified losses and gains between 2017 and 2024 across the entire Loiret region at the native 250 m resolution, incorporating LULC transitions and climate-specific stock change factors to assess degradation under the SDG 15.3.1 framework. Pixels with ≥10% SOC loss were classified as degraded, ≥10% gain as improved, and changes between −10% and +10% as stable.

The analysis classified 1050 ha as degraded, representing 0.15% of the region; 665,390 ha as stable, accounting for 97.85%; and 13,430 ha as improved, comprising 1.97% of the total area (approximately 679,800 ha = 6798 km2). Degraded areas were primarily associated with transitions involving loss of natural cover, such as from crops to bare land or trees to built-up areas. The degraded area’s SOC stocks declined due to reduced organic inputs and increased disturbance. Improved areas corresponded to positive transitions, like bare land to crops or grass to trees, which enhanced SOC accumulation through increased vegetation cover and root biomass. Stable areas dominated, reflecting minimal LULC changes or transitions with negligible impact on SOC, such as within-class stability (e.g., crops to crops).

Figure 4 depicted SOC change hotspots, with degraded pixels (red) clustered in peri-urban zones near Orléans and scattered agricultural fields, where urbanization or intensive farming led to carbon depletion. Improved pixels (yellow) appeared in reforested or restored agricultural areas. Stable regions (orange) covered most of the rural landscapes. The spatial distribution aligned with LULC patterns from Section 3.1, as degraded SOC zones overlapped with areas of urban expansion or vegetation loss in the zoomed zones, indicating a linkage between land cover shifts and soil health. Comparisons with LULC results suggested that SOC changes amplified degradation signals in transitioned areas. For instance, the small, degraded SOC extent (0.15%) contrasted with higher LULC degradation in specific zones, highlighting SOC’s slower response to short-term changes. The 7-year period (scaled by 7/20 for equilibrium assumptions) captured subtle dynamics. The coarse 250 m resolution aggregated fine-scale variations, potentially underestimating localized losses in heterogeneous fields.

Figure 4.

SOC classified as degraded, stable, and improved (2017–2024) Scale: 1:950,000. Source: Section 2.5.2 Sub-indicator 2: Soil Organic Carbon Changes.

3.3. Land Productivity Dynamics Analysis

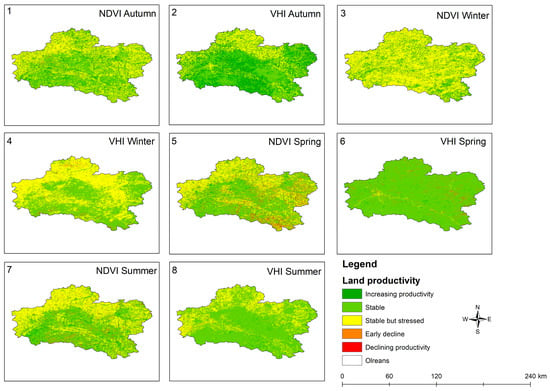

The land productivity dynamics analysis evaluated trends in NDVI and VHI across the Loiret region from 2017 to 2024 on a seasonal basis at 30 m resolution, using statistically significant Mann–Kendall trends (z-score thresholds) and Sen’s slope to classify areas into increasing, stable, stable but stressed, declining early, and declining severe categories. Only significant trends were considered changing; non-significant pixels were classified as stable.

Table 4 summarized seasonal areas (in ha) for each category using NDVI and VHI. For NDVI, winter showed the largest stable but stressed area (462,850 ha, 67.8% of the region), followed by autumn (310,560 ha, 45.5%), while spring had the highest declining severe (38,760 ha, 5.7%) and summer the highest declining early (10,490 ha, 1.5%). Stable areas varied, ranging from 96,090 ha (winter, 14.1%) to 390,280 ha (spring, 57.2%). Increasing areas were highest in autumn (146,120 ha, 21.4%) and lowest in spring (31,340 ha, 4.6%). For VHI, stable areas dominated more prominently, from 220,350 ha (autumn, 32.3%) to 649,610 ha (spring, 95.2%), with stable but stressed reduced (e.g., 9730 ha in spring, 1.4%). Declining severe was lower overall for VHI (e.g., 14,150 ha in spring, 2.1%). Declining early remained minimal (e.g., 180 ha in spring, <0.1%).

Table 4.

Seasonal areas (ha) in land productivity categories for NDVI and VHI (2017–2024).

Figure 5 compares NDVI and VHI maps seasonally, illustrating VHI’s finer detection of thermal anomalies in vegetated areas. Comparisons revealed that VHI detected more increasing areas in autumn (271,520 ha vs. NDVI’s 146,130 ha, 1.86 times more) but far less declining severe in winter (8130 ha vs. 2940 ha, though higher in absolute terms for VHI here). In spring, VHI identified less declining early (180 ha vs. NDVI’s 3550 ha, 19.7 times less) but similar severe declines (14,150 ha vs. 38,760 ha, 64% less). Autumn showed VHI detecting 28 times less declining early (10 ha vs. 320 ha) and 16 times less severe (280 ha vs. 4550 ha), suggesting better differentiation of variability. Summer exhibited VHI with 13 times less declining early (40 ha vs. 10,490 ha) and 3.6 times less severe (3420 ha vs. 12,310 ha), emphasizing thermal moderation in productivity assessments. Thermal moderation, in this context, refers to VHI’s integration of TCI alongside VCI. Combining the strength of LST and NDVI provides a more balanced detection of vegetative stress [26], known to be a significant driver/manifestation of land degradation. The rationale behind this statement is that neglecting temperature stress on vegetation can quickly lead to losing forests, orchards or perennials (besides lasting effects on soil microbiota and soil texture that affect annual crops). This has been somehow disregarded in national reporting for some years. Undermining this aspect can lead to large-scale abandonment of crop lands, which in turn exposes lands to further land degradation drivers such as soil erosion.

Figure 5.

Comparison between land degradation using NDVI and VHI on a seasonal basis. Scale: 1:1,750,000. Source: Mann–Kendall trends. Numbers 1–8 represent the title of each sub-figure.

Temperature moderation results in fewer false positives in declining categories, as seen in summer and autumn, where VHI reclassifies NDVI-detected declines as stable if elevated temperatures explain the vegetation response. This reclassification provides a more resilient and context-aware metric for heterogeneous landscapes. The results demonstrated VHI’s advantages in detecting field-level stress, providing more nuanced insights than NDVI alone, particularly in heterogeneous landscapes.

To examine the overall pixel value distributions of NDVI and VHI across the 2017–2024 period, aggregated histograms were generated. The NDVI distribution exhibited a mean of 0.518, median of 0.507, and standard deviation of 0.125, with values ranging from −0.536 to 0.773. Approximately 0.57% of pixels were negative, 47.80% fell between 0 and 0.5 (indicating moderate vegetation health), and 51.63% were ≥0.5 (suggesting healthy to vigourous vegetation). In contrast, the VHI distribution had a lower mean of 0.254, median of 0.233, and standard deviation of 0.118, with values ranging from −0.474 to 0.548. Here, 1.41% of pixels were negative, 98.54% were between 0 and 0.5, and only 0.05% were ≥0.5, reflecting a shift toward lower health scores due to thermal influences. Bins are spaced at 0.002 intervals, with frequencies representing total pixel counts (11.29 million per index). These distributions highlight NDVI’s tendency to capture higher vegetation vigour, with a peak around 0.5–0.6, while VHI shows a broader spread in the 0.1–0.4 range, indicating greater sensitivity to stress conditions that align with the observed reductions in declining categories during seasonal analyses.

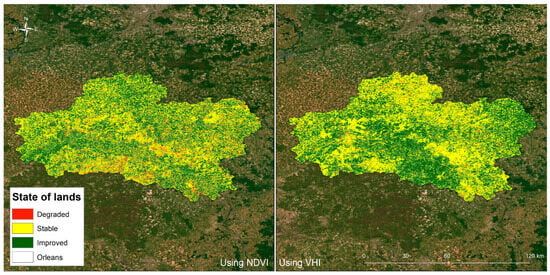

3.4. Integrated Assessment (“One Out, All Out”)

The “One Out, All Out” methodology integrates the three SDG 15.3.1 sub-indicators to provide a comprehensive assessment of land degradation across the Loiret region from 2017 to 2024 at 30 m resolution. This conservative rule classifies pixels as degraded if any sub-indicator showed degradation, improved only if all indicated improvement, and stable otherwise, prioritizing risk identification. The final integrated land degradation assessment using the “One Out, All Out” principle was performed exclusively at 30 m resolution for both the NDVI-based and VHI-based maps. Producing integrated maps at 10 m or 1 m would require either (i) artificial downscaling of the SOC layer (which we explicitly avoided because it introduced unrealistic artefacts) or (ii) omitting the SOC sub-indicator entirely. The later would deviate from the official three-indicator SDG 15.3.1 framework. The added value of the 10 m and especially 1 m resolutions is therefore fully retained and demonstrated in the LULC-change sub-indicator alone, where finer-scale transitions are clearly detectable, but the precautionary, three-indicator integration remains at 30 m.

Table 5 summarized the areas (in ha) classified as degraded, stable, and improved for both NDVI- and VHI-based integrations. For the NDVI-based assessment, degraded areas totaled 48,440 ha (7.1% of the region), stable areas 357,490 ha (52.4%), and improved areas 275,720 ha (40.4%). In contrast, the VHI-based assessment identified less degradation, with 17,990 ha degraded (2.6%), 375,690 ha stable (55.1%), and 287,970 ha improved (42.2%). These results reflected the remapping of productivity categories, where declining trends (early and severe) were assigned as −1 (degraded), stable and stressed as 0 (stable), and increasing as 1 (improved), ensuring alignment with LULC and SOC outputs.

Table 5.

Areas (ha) classified as degraded, stable, and improved using the “One Out, All Out” approach for NDVI- and VHI-based integrations (2017–2024).

Figure 6 compared the NDVI- and VHI-based degradation maps, with degraded areas (red) more widespread in the NDVI integration, while VHI showed concentrated hotspots. Stable regions (yellow) dominated both maps, covering central rural expanses, and improved areas (green) clustered in restored forests or vegetated fields.

Figure 6.

Degraded, stable, and improved classification using the “One Out, All Out” approach for NDVI- and VHI-based integrations (2017–2024). Scale: 1:955,000.

Comparisons between the two integrations highlighted NDVI’s higher sensitivity to degradation, detecting 2.69 times more degraded area than VHI (48,440 ha vs. 17,990 ha, a 169% increase), likely due to its focus on vegetation density without thermal moderation. VHI, incorporating temperature stress, classified more areas as stable (5.1% higher proportion) and improved (4.4% higher), suggesting that it better differentiated variability (i.e., changes in land state) from persistent decline in heterogeneous landscapes. VHI’s lower degradation extent indicated reduced false positives in stressed but resilient areas, like seasonally dry croplands. These integrated results underscored the region’s overall stable status, with degradation affecting a minor portion (2.6–7.1%), primarily in agricultural and peri-urban zones, while improvements in 40.4–42.2% of the region indicated areas of productivity gain. The approach provided a spatially explicit overview, revealing that VHI enhanced nuance in productivity assessments compared to NDVI, consistent with its advantages in stress detection.

4. Discussion

Theoretically, this study proposed remote sensing-based advances to the SDG 15.3.1 framework, demonstrating that (i) VDSR downscaling increases land degradation detection (supporting Hypothesis 1, with up to 957% more degraded areas identified at 1 m resolution); and (ii) VHI refines productivity assessments (supporting Hypothesis 2, with 2.69 times less degradation in integrated analyses). This refinement complements the framework’s applicability in heterogeneous landscapes. The results of this study demonstrated the efficacy of spectral downscaling and advanced indices in enhancing land degradation detection under the SDG 15.3.1 framework. Validation metrics confirm the improvements, with VDSR reducing RMSE by ~27% over bicubic methods and RF achieving > 94% accuracy at 1 m, supporting reliable detection despite potential errors from data mismatches.

The LULC change analysis at varying resolutions revealed that the 1 m downscaled imagery captured more fine-scale transitions than coarser 30 m or 10 m data, with degraded areas increasing. This aligns with previous findings on the limitations of native satellite resolutions in detecting subtle land use pressures, such as fine-scale land cover changes [45]. The observed patterns, where coarser resolutions aggregated small, degraded patches into stable categories, underscored the risk of underestimation in mixed land use areas.

The SOC analysis indicated minimal overall degradation (0.15%), with losses concentrated in transitioned areas like crops to bare land, reflecting slow soil carbon responses to short-term changes as noted in UNCCD guidelines [7]. This complemented LULC results, amplifying signals in peri-urban zones, though the coarse 250 m baseline likely masked localized variations, echoing critiques of global SOC datasets in regional applications [46].

The land productivity dynamics further highlighted VHI advantages over NDVI in sensitivity to vegetation stress. Seasonal trends showed that NDVI detected higher stressed and severe declines (e.g., 67.8% stable but stressed in winter), while VHI classified more areas as stable (up to 95.2% in spring). VHI identified 1.86 times more increasing productivity in autumn, indicating better differentiation of thermal impacts. This supported the working hypothesis that VHI, by integrating TCI and VCI, provides a more robust assessment in stressed conditions, where NDVI’s atmospheric sensitivity often overestimates decline.

The aggregated pixel distributions further support VHI’s enhanced sensitivity compared to NDVI, as evidenced by its lower mean (0.254 vs. 0.518) and concentration of values in the 0–0.5 range (98.54% vs. 47.80%). This shift likely arises from VHI’s thermal moderation, where elevated LST values during stress periods (e.g., summer heat) temper NDVI signals. This tempering results in fewer overestimations of decline and a more conservative assessment of vegetation health. In the Loiret region’s mixed agricultural landscape, NDVI’s higher proportion of values ≥ 0.5 (51.63%) may reflect robust cropland productivity, but VHI’s distribution underscores subtle thermal impacts that could inform early degradation warnings, aligning with SDG 15.3.1 goals for monitoring.

While VHI’s incorporation of thermal data refines short-term variability detection to guide targeted interventions (e.g., irrigation in stressed fields), this thermal integration also prompts reflection on longer-term climate dynamics. In temperate zones like Loiret, accumulating thermal stresses could exacerbate underlying degradation processes, underscoring the need for adaptive SDG 15.3.1 applications that integrate multi-decadal trends and scenario modelling for resilience planning.

The integrated “One Out, All Out” assessment revealed 2.6–7.1% degradation, with NDVI yielding higher degraded areas (2.69 times more than VHI), suggesting VHI reduces false positives in resilient but variable croplands. These findings align with global degradation estimates in a broader context.

Beyond SDG 15.3.1 policy applications, the enhanced 1 m resolution and VHI sensitivity of the proposed approach could potentially be combined with other datasets and monitoring approaches for targeted land management. Possible fields of application could, for instance, include farm-scale interventions such as variable-rate fertilization in erosion hotspots or irrigation optimization. Scalability to other temperate regions with similar mixed land uses is promising, as VDSR and VHI integration could refine Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) targets and areas of intervention.

In terms of limitations, the 1 m resolution risked over-classification of momentary changes as degradation which was decreased by using the median images per year, potentially inflating estimates in dynamic agricultural zones. SOC uncertainties arose from the coarse baseline and reliance on IPCC factors, which may not fully capture local soil variability. LST corrections could introduce errors in cloudy conditions. The 7-year period limited equilibrium assumptions for SOC, and the absence of ground validation constrained result reliability. Future directions include incorporating high-resolution soil surveys and additional indices like the Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index for refined stress detection. Long-term temporal analyses over decades could track trends more robustly. Projecting these trends by including observed and projected climate extremes as explanatory variables would help disentangle climate-driven vegetation stress from management-induced degradation. This approach would further refine the interpretation of VHI-based productivity trends under changing climatic conditions. Ground-based surveys in hotspots could validate remote sensing outputs, addressing false positives and supporting adaptive management strategies. For scalability, the methodology supports long-term monitoring through annual/seasonal GEE ingestion of new images for real-time degradation tracking and cross-regional applications to other temperate zones with similar mixed land uses, refining global LDN efforts under UNCCD.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed the integration of VDSR downscaling and the VHI into the SDG 15.3.1 framework for more precise land degradation mapping. The 1 m resolution imagery improved detection of fine-scale LULC transitions, revealing up to 10 times more degraded areas than coarser resolutions. VHI enhanced productivity assessments by better capturing thermal stress compared to NDVI, reducing overestimation of declines in heterogeneous croplands. SOC analysis indicated minimal overall degradation, complementing LULC and productivity sub-indicators. The “One Out, All Out” integration highlighted 2.6–7.1% of the region as degraded, primarily in agricultural and peri-urban zones. Theoretically, these findings contribute to the SDG 15.3.1 framework by advancing multi-scale remote sensing integration and enabling dynamic assessments. Policy-wise, the approach informs targeted interventions, such as soil conservation in hotspots, potentially reducing economic losses from degradation and aiding global efforts. These findings underscore the potential of advanced remote sensing to provide precise, actionable insights for sustainable land management, supporting targeted land management and food security in similar mixed landscapes.

In conclusion, while the current generation of global SOC datasets still constrains official SDG 15.3.1 reporting to 30 m or coarser, the increase in LULC-related degraded area achieved by the 1 m VDSR-downscaled imagery demonstrates that super-resolution techniques are key for land degradation mapping. The added value to of the proposed methodology is its replicability that allows the following:

- (i)

- The technical feasibility of producing land degradation maps at metre-scale.

- (ii)

- The method’s relevance in heterogeneous landscapes where LULC change is the main degradation driver, and metre-scale changes are significant and would be missed by lower-resolution monitoring.

In terms of limitations, it is important to mention that some conceptual issues remain. These are linked both to intrinsic problems with multiple-purpose monitoring approaches, as well as to the combination of spatially fine-grained mapping of land use and land cover changes, with temporally coarse monitoring. Although the study proposes to address limitations with “static” perspectives on land degradation, the chosen approach relies on assumptions that are better suited to overall stable conditions, rather than considering dynamic processes, evolving interactions, and cumulative effects. The decision to disregard extremes and variability also limits the relevance of the approach under climate change, as well as with respect to targeted interventions at farm-scale or local levels, similar to the neglection of temperature stress on vegetation. Future research should incorporate ground validation and extended temporal scales once available to refine these methodologies, ultimately contributing to global efforts in combating land degradation and achieving Land Degradation Neutrality.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14122439/s1.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by N.E.B. and M.A.S. The first draft of the manuscript was written by N.E.B., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Conceptualization, N.E.B., M.A.S., R.D.S. and R.N.; methodology, N.E.B.; formal analysis, N.E.B.; investigation, N.E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.E.B. and M.A.S.; writing—review and editing, N.E.B., M.A.S., R.D.S. and R.N.; supervision, M.A.S., R.D.S. and R.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data and methods used in Google Earth Engine are available in the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| Fv | Fractional Vegetation Cover |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LDN | Land Degradation Neutrality |

| LULC | Land Use/Land Cover |

| LST | Land Surface Temperature |

| NDBI | Normalized Difference Built-up Index |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SOC | Soil Organic Carbon |

| SWIR | Short Wave Infrared |

| TCI | Temperature Condition Index |

| TIRS | Thermal Infrared Sensor |

| UNCCD | United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| VCI | Vegetation Condition Index |

| VDSR | Very Deep Super-Resolution |

| VHI | Vegetation Health Index |

References

- Safriel, U.N. The Assessment of Global Trends in Land Degradation. In Climate and Land Degradation; Sivakumar, M.V.K., Ndiang’ui, N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 1–38. ISBN 978-3-540-72438-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, G.S. Land Degradation and Challenges of Food Security. Rev. Eur. Stud. 2019, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.-Z.; Tan, M.-Z.; Gong, Z.-T. Soil Degradation: A Global Problem Endangering Sustainable Development. J. Geogr. Sci. 2002, 12, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, E.M. Response to Land Degradation; Bridges, E.M., Hannam, I.D., Oldeman, L.R., de Vries, F.W.T.P., Scherr, S.J., Sombatpanit, S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780429187957. [Google Scholar]

- Ekka, P.; Patra, S.; Upreti, M.; Kumar, G.; Kumar, A.; Saikia, P. Land Degradation and Its Impacts on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. In Land and Environmental Management Through Forestry; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar, A.; Dunne, D.; Viglione, G. UN Land Report: Five Key Takeaways for Climate Change, Food Systems and Nature Loss; Carbon Brief: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). Investing in Land’s Future: Financial Needs Assessment for UNCCD; UNCCD: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Al Sayah, M.J.; Abdallah, C.; Der Sarkissian, R.; Abboud, M. A Framework for Investigating the Land Degradation Neutrality—Disaster Risk Reduction Nexus at the Sub-National Scales. J. Arid. Environ. 2021, 195, 104635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Rambaud, P.; Finegold, Y.; Jonckheere, I.; Martin-Ortega, P.; Jalal, R.; Adebayo, A.D.; Alvarez, A.; Borretti, M.; Caela, J.; et al. Monitoring Sustainable Development Goal Indicator 15.3.1 on Land Degradation Using SEPAL: Examples, Challenges and Prospects. Land 2024, 13, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Das, S.; Gorain, S.; Dutta, S.; Roy Choudhury, M.; Das, S. Land Degradation Neutrality: A Pathway to Achieving Sustainable Development Goals and Ecosystem Resilience. Discov. Soil 2025, 2, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Woodcock, C.E.; Bullock, E.L.; Arévalo, P.; Torchinava, P.; Peng, S.; Olofsson, P. Monitoring Temperate Forest Degradation on Google Earth Engine Using Landsat Time Series Analysis. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 265, 112648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Gong, J.; Dang, D.; Dou, H.; Lyu, X. Quantitative Analysis of Natural and Anthropogenic Factors Influencing Vegetation NDVI Changes in Temperate Drylands from a Spatial Stratified Heterogeneity Perspective: A Case Study of Inner Mongolia Grasslands, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Bentley, L.; Feeney, C.; Lofts, S.; Robb, C.; Rowe, E.C.; Thomson, A.; Warren-Thomas, E.; Emmett, B. Land Degradation Neutrality: Testing the Indicator in a Temperate Agricultural Landscape. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 346, 118884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasek, P.; Akhtar-Schuster, M.; Orr, B.J.; Luise, A.; Rakoto Ratsimba, H.; Safriel, U. Land Degradation Neutrality: The Science-Policy Interface from the UNCCD to National Implementation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 92, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFAO. FAO Soils Portal-Degradation/Restoration; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: http://www.fao.org/soils-portal/soil-degradation-restoration/en/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Sims, N.C.; Newnham, G.J.; England, J.R.; Guerschman, J.; Cox, S.J.D.; Roxburgh, S.H.; Viscarra Rossel, R.A.; Fritz, S.; Wheeler, I. Good Practice Guidance. SDG Indicator 15.3.1, Proportion of Land That Is Degraded Over Total Land Area. Version 2.0; United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva, O.V.; Kust, G.S. Land Assessment in Russia Based on the Concept of Land Degradation Neutrality. Reg. Res. Russ. 2020, 10, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, T.; Garcia, C.L.; Teich, I.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Kabo-Bah, A.T.; Yang, Z.; Jia, X.; Lu, Q.; et al. A 30-Meter Resolution Global Land Productivity Dynamics Dataset from 2013 to 2022. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, N.C.; England, J.R.; Newnham, G.J.; Alexander, S.; Green, C.; Minelli, S.; Held, A. Developing Good Practice Guidance for Estimating Land Degradation in the Context of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 92, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillaci, C.; Vieira, D.S.; Jones, A.; Montanarella, L.; Wojda, P. IACS65AA—Soil Case Studies—Land Degradation Index; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- D’Acunto, F.; Dubovyk, O.; Raghuvanshi, N.; Marinello, F.; Iodice, F.; Pezzuolo, A. A Multi-Model Framework Based on Remote Sensing to Assess Land Degradation in Rural Areas. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouikhi, F.; Abbes, A.B.; Farah, I.R. An End-to-End Pipeline Based on a Two-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network for Monitoring Desertification in Africa Using Remote Sensing Images. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 193, 106622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, G.; Chatenoux, B.; Benvenuti, A.; Lacroix, P.; Santoro, M.; Mazzetti, P. Monitoring Land Degradation at National Level Using Satellite Earth Observation Time-Series Data to Support SDG15—Exploring the Potential of Data Cube. Big Earth Data 2020, 4, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, T.; Li, J.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y. Single-Image Super Resolution of Remote Sensing Images with Real-World Degradation Modeling. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.U.; Ekhtiari, N.; Almeida, R.M.; Rieke, C. Super-Resolution of Multispectral Satellite Images Using Convolutional Neural Networks. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, V-1-2020, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, C.; Maftei, C. Remote Sensing Evaluation of Drought Effects on Crop Yields Across Dobrogea, Romania, Using Vegetation Health Index (VHI). Agriculture 2025, 15, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Zhao, W.; Zhan, T.; Yan, Y.; Pereira, P. Land Degradation Neutrality: A Review of Progress and Perspectives. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 144, 109530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, T.G.; Rosen, P.A.; Caro, E.; Crippen, R.; Duren, R.; Hensley, S.; Kobrick, M.; Paller, M.; Rodriguez, E.; Roth, L.; et al. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. Rev. Geophys. 2007, 45, RG2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). ERA5: Fifth Generation of ECMWF Atmospheric Reanalyses of the Global Climate. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=overview (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Hengl, T. Soil Texture Classes (USDA System) for 6 Soil (0, 10, 30, 60, 100 and 200 cm) at 250 m; Zenodo: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nkonya, E.; Anderson, W.; Kato, E.; Koo, J.; Mirzabaev, A.; von Braun, J.; Meyer, S. Global Cost of Land Degradation. In Economics of Land Degradation and Improvement—A Global Assessment for Sustainable Development; Nkonya, E., Mirzabaev, A., von Braun, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 117–165. ISBN 978-3-319-19168-3. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.P.; Wattenbach, M.; Smith, P.; Meersmans, J.; Jolivet, C.; Boulonne, L.; Arrouays, D. Spatial Distribution of Soil Organic Carbon Stocks in France. Biogeosciences 2011, 8, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Meusburger, K.; Ballabio, C.; Borrelli, P.; Alewell, C. Soil Erodibility in Europe: A High-Resolution Dataset Based on LUCAS. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 479–480, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, P.; Ballabio, C.; Panagos, P.; Montanarella, L. Wind Erosion Susceptibility of European Soils. Geoderma 2014, 232–234, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Beyrouthy, N.; Al Sayah, M.; Der Sarkissian, R.; Nedjai, R. Enhancing Urban Temperature Monitoring Through High-Resolution Remote Sensing and Advanced Data Processing Techniques. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2025, 156, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, H.K.; Salmon, J.M. Mapping the World’s Degraded Lands. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 57, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.F.; Brumby, S.P.; Guzder-Williams, B.; Birch, T.; Hyde, S.B.; Mazzariello, J.; Czerwinski, W.; Pasquarella, V.J.; Haertel, R.; Ilyushchenko, S.; et al. Dynamic World, Near Real-Time Global 10 m Land Use Land Cover Mapping. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service Eau et Biodiversité, Département Données et Expertise. Guide Pour La Prise En Compte Des Zones Humides Dans Un Dossier « loi Sur l’eau » Ou Un Document d’urbanisme; Direction régionale de l’Environnement, de l’Aménagement et du Logement du Centre-Val de Loire: Centre-Val de Loire, France, 2016. Available online: https://www.centre-val-de-loire.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/guideZH-centre-valdeloire-janvier2016_cle273a77.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Hengl, T.; Wheeler, I. Soil Organic Carbon Content in × 5 g/kg at 6 Depths (0, 10, 30, 60, 100 and 200 cm) at 250 m Resolution; Zenodo: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hengl, T. Soil Bulk Density (Fine Earth) 10 × Kg/m-cubic at 6 Standard Depths (0, 10, 30, 60, 100 and 200) at 250 m Resolution; Zenodo: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; He, K.; Tang, X. Image Super-Resolution Using Deep Convolutional Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 38, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, P.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, D.; Huang, Z.; Hou, X.; Cottrell, G. Understanding Convolution for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; pp. 1451–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Département du Loiret: Structures et Productions. Recensement Agricole 2020. Available online: https://draaf.centre-val-de-loire.agriculture.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Etudes_RA_45_cle0ef5e6-1.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Prokop, P. Remote Sensing of Severely Degraded Land: Detection of Long-Term Land-Use Changes Using High-Resolution Satellite Images on the Meghalaya Plateau, Northeast India. Remote Sens. Appl. 2020, 20, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillaci, C.; Jones, A.; Vieira, D.; Munafò, M.; Montanarella, L. Evaluation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 15.3.1 Indicator of Land Degradation in the European Union. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).