Relationship Between Built-Up Spatial Pattern, Green Space Morphology and Carbon Sequestration at the Community Scale: A Case Study of Shanghai

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Data Sources

2.4. Methods

2.4.1. Calculation Method of Carbon Sequestration

2.4.2. Hotspot and Coldspot Analysis

2.4.3. Factors Affecting the Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Communities

2.4.4. Interpretable Machine Learning Methods for Revealing Complex Factor Influences

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Pattern of Carbon Sequestration

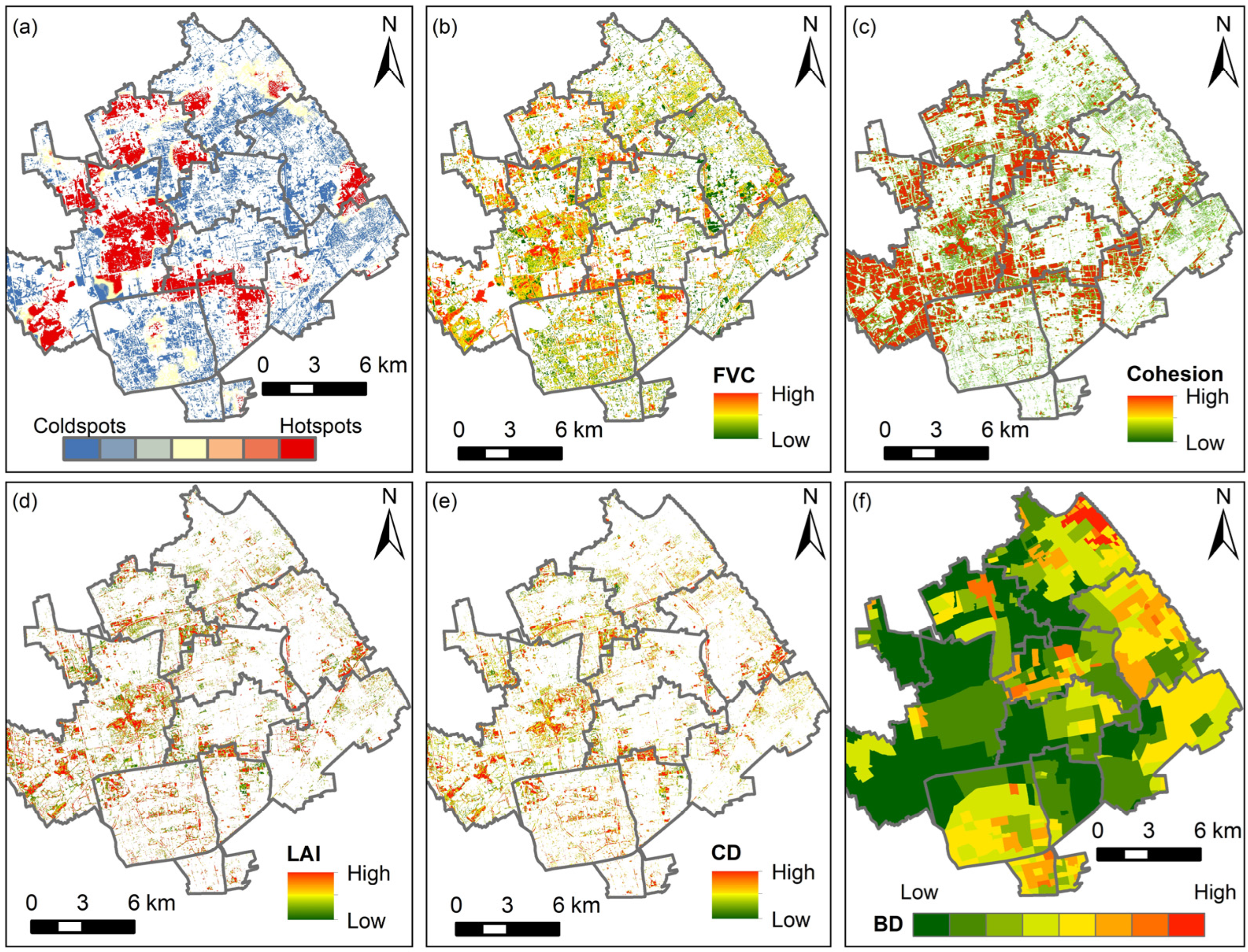

3.2. Spatial Patterns of Carbon Sequestration Hotspots and Coldspots

3.3. Analysis of Factors Affecting Carbon Sequestration

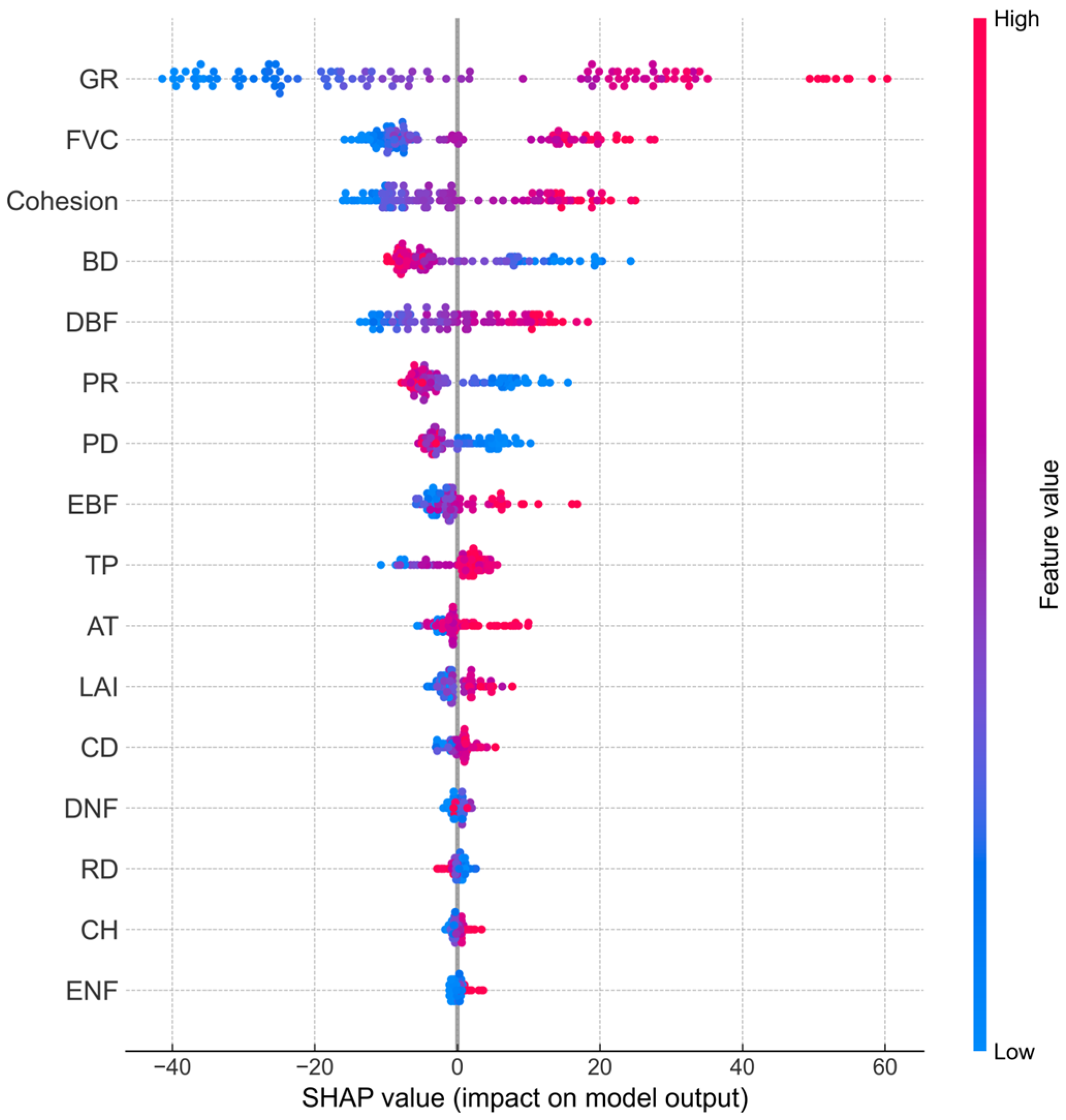

3.3.1. Analysis of the Contribution of Each Factor to Carbon Sequestration

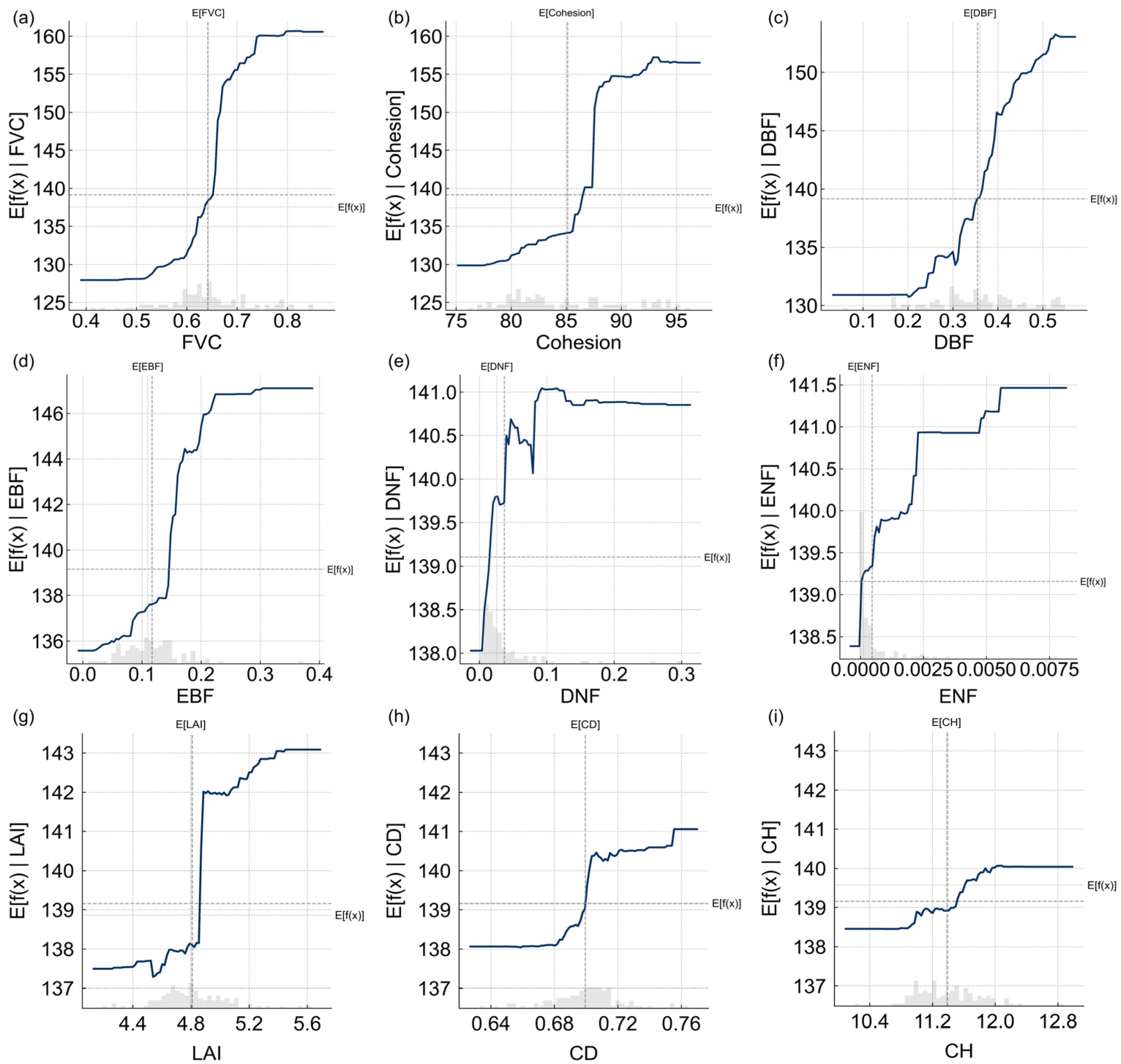

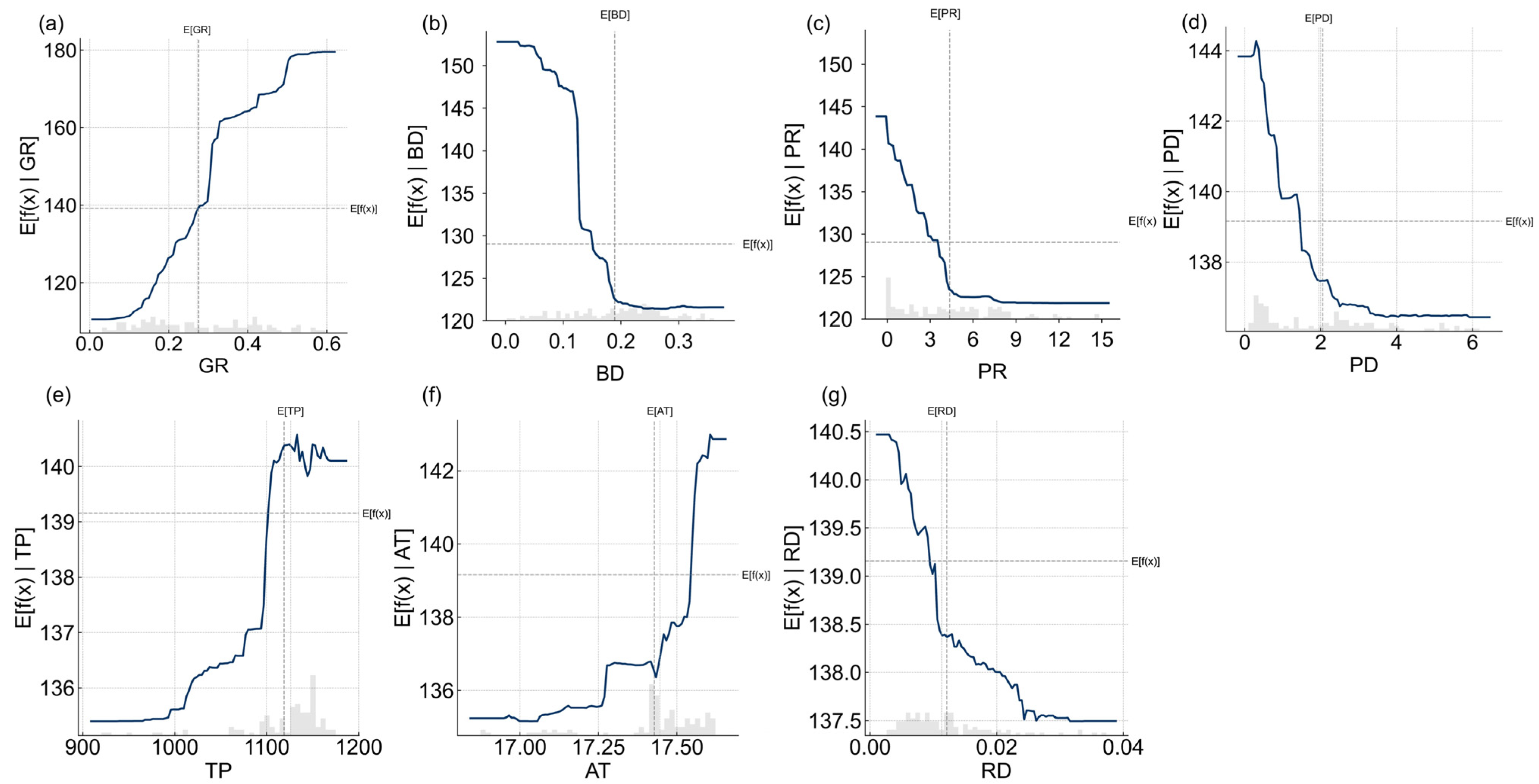

3.3.2. Marginal Effect Analysis of Factors on Carbon Sequestration

- (1)

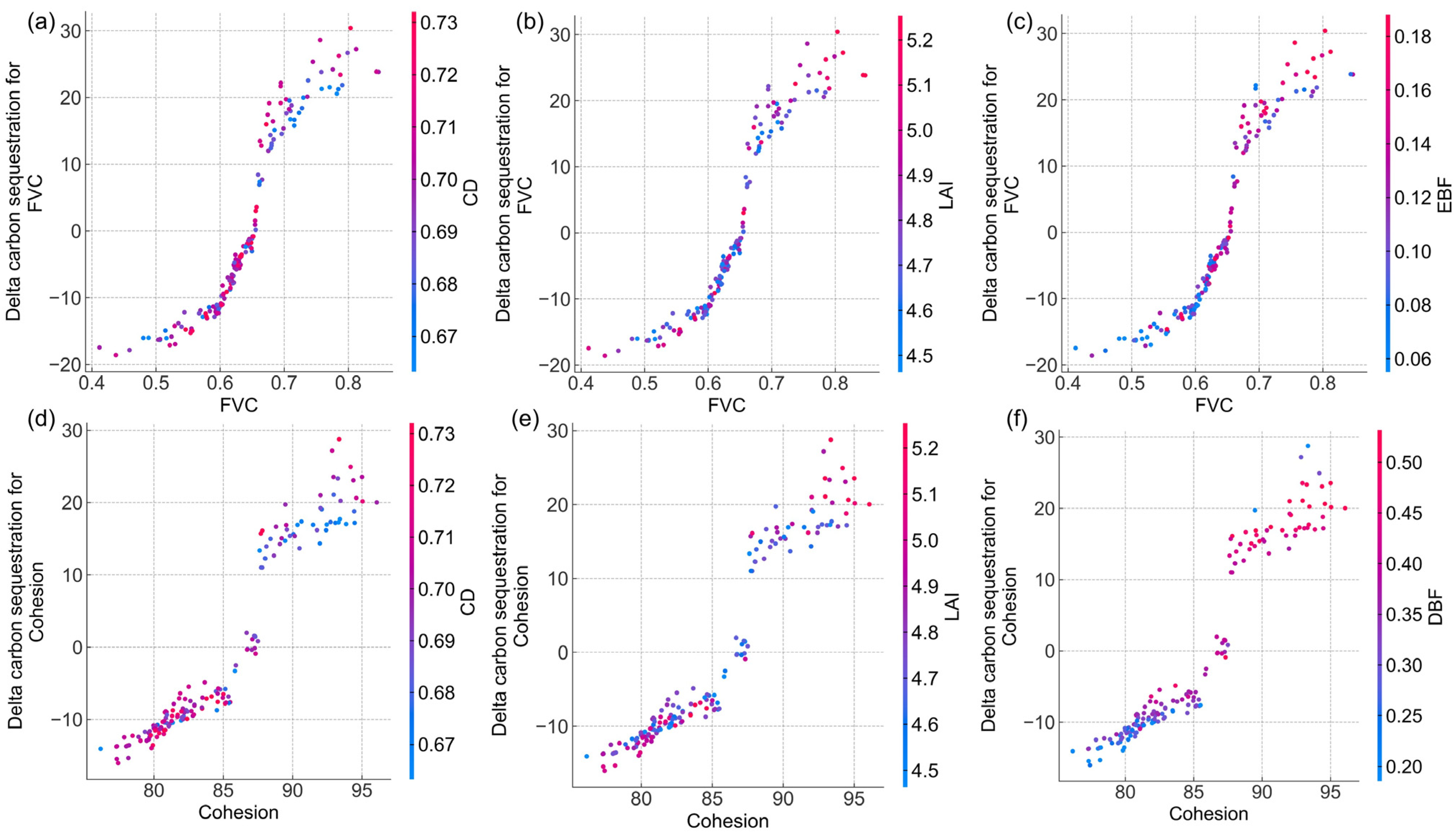

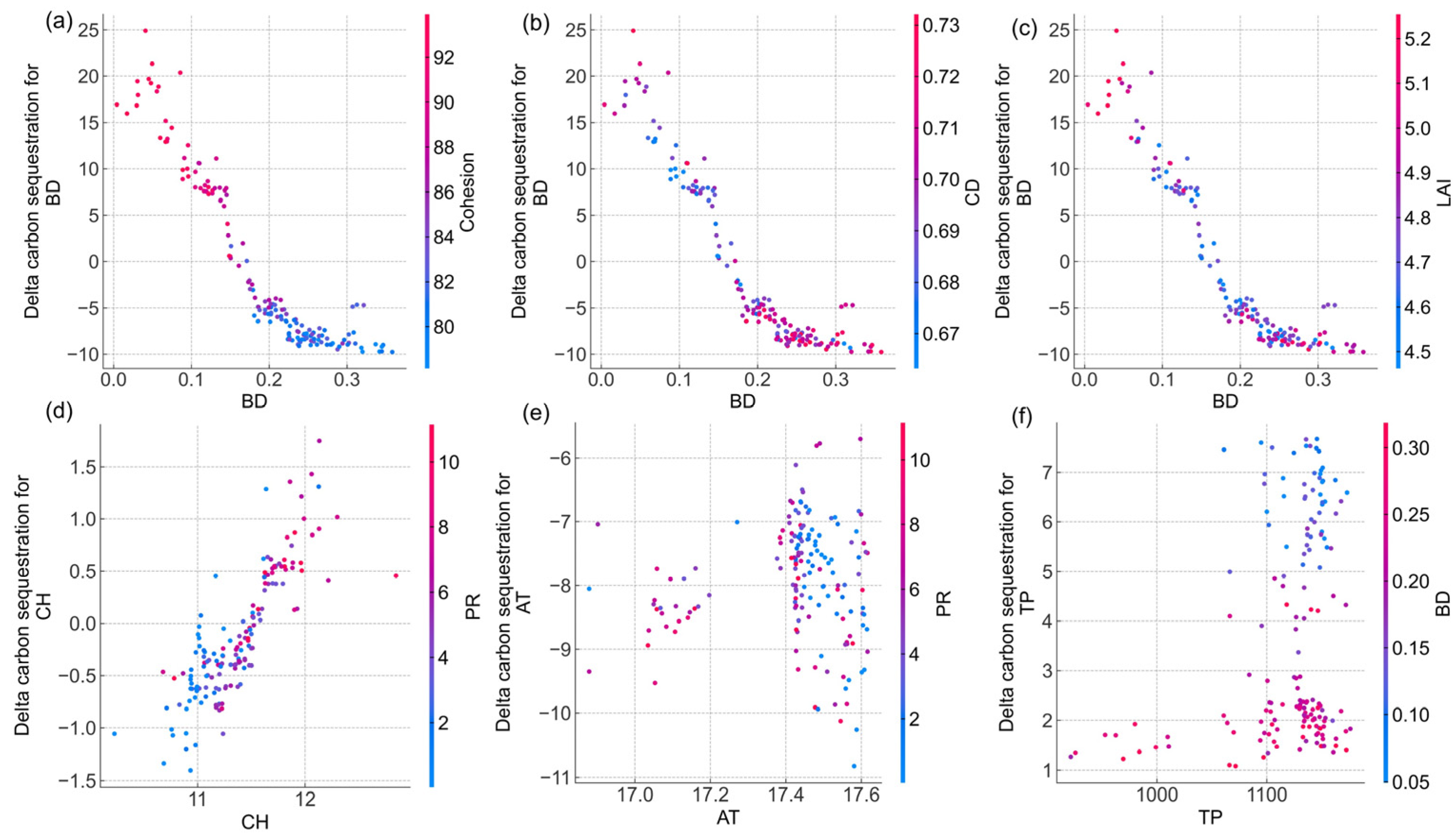

- Green space morphology factors

- (2)

- Built-up spatial pattern factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Canopy Structure Enhances the Effects of Two-Dimensional Green Space Factors on Carbon Sequestration

4.2. Carbon Sequestration Interactions Between Green Space Morphology Factors and Building Morphology Factors

4.3. Comparison and Insights with Studies at Different Scales

4.4. Limitations and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grimm, N.B.; Faeth, S.H.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Redman, C.L.; Wu, J.; Bai, X.; Briggs, J.M. Global Change and the Ecology of Cities. Science 2008, 319, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.T.; Jia, B.Q.; Li, F.; Ma, J.; Liu, X.P.; Feng, F.; Liu, H.L. Effects of multi-scale structure of blue-green space on urban forest carbon density: Beijing, China case study. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 883, 163682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretero, E.M.; Moreno, G.; Duplancic, A.; Abud, A.; Vento, B.; Jauregui, J.A. Urban forest of Mendoza (Argentina): The role of Morus alba (Moraceae) in carbon storage. Carbon Manag. 2017, 8, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y. The role of urban green infrastructure in offsetting carbon emissions in 35 major Chinese cities: A nationwide estimate. Cities 2015, 44, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, D.E.; Carreiro, M.M.; Cherrier, J.; Grulke, N.E.; Jennings, V.; Pincetl, S.; Pouyat, R.V.; Whitlow, T.H.; Zipperer, W.C. Coupling biogeochemical cycles in urban environments: Ecosystem services, green solutions, and misconceptions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariluoma, M.; Ottelin, J.; Hautamäki, R.; Tuhkanen, E.-M.; Mänttäri, M. Carbon sequestration and storage potential of urban green in residential yards: A case study from Helsinki. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; He, B.-J. A standardized assessment framework for green roof decarbonization: A review of embodied carbon, carbon sequestration, bioenergy supply, and operational carbon scenarios. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2023, 182, 113376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xie, S.; Zhao, S.Q. Valuing urban green spaces in mitigating climate change: A city-wide estimate of aboveground carbon stored in urban green spaces of China’s Capital. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 1717–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Yue, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Piao, S.L. Forestation at the right time with the right species can generate persistent carbon benefits in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e230498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X. A new framework for analysis of the spatial patterns of 15-minute neighbourhood green space to enhance carbon sequestration performance: A case study in Nanjing, China. Ecol. Indic 2023, 156, 111196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Meng, W.; Yuan, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, H. Mapping carbon sinks in megacity ecosystem: Accuracy estimation coupling experiment and satellite data based on GEE. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol 2024, 22, 11017–11036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Z.G.; Edmondson, J.L.; Heinemeyer, A.; Leake, J.R.; Gaston, K.J. Mapping an urban ecosystem service: Quantifying above-ground carbon storage at a city-wide scale. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 48, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.L.; Han, H.T.; Feng, Y.; Song, P.T.; He, R.Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, K.H.; Du, C.Y.; Ge, S.D.; et al. Scale-dependent and driving relationships between spatial features and carbon storage and sequestration in an urban park of Zhengzhou, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 164916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.M.; Brandt, M.; Yue, Y.M.; Tong, X.W.; Wang, K.L.; Fensholt, R. The carbon sink potential of southern China after two decades of afforestation. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2022EF002674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, D.J.; Greenfield, E.J. Tree and impervious cover change in U.S. cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, E.G.; Xiao, Q.F.; Aguaron, E. A new approach to quantify and map carbon stored, sequestered and emissions avoided by urban forests. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 120, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Rich, P.M.; Gower, S.T.; Norman, J.M.; Plummer, S. Leaf area index of boreal forests: Theory, techniques, and measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1997, 102, 29429–29443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.; Wang, S.; Wei, F.L.; Shen, M.G.; Fu, B.J. Inconsistent changes in NPP and LAI determined from the parabolic LAI versus NPP relationship. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Xv, D.; Tang, J.; Lu, J.; Wu, Y. Assessing the effects of urban green spaces metrics and spatial structure on LST and carbon sinks in Harbin, a cold region city in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 113, 105659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissert, L.F.; Salmond, J.A.; Schwendenmann, L. Photosynthetic CO2 uptake and carbon sequestration potential of deciduous and evergreen tree species in an urban environment. Urban Ecosyst. 2017, 20, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, E.Y.; Wu, H.F.; Feng, D.L. Carbon storage estimation and strategy optimization under low carbon objectives for urban attached green spaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; Cheng, S. Multi-scenario simulation of spatial structure and carbon sequestration evaluation in residential green space. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.J.; Zhou, M.D.; Zhu, A.T.; Shi, S.C.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Y.Z.; Li, S.S.; Fan, T.S. Evolution, reconfiguration and low-carbon performance of green space pattern under diverse urban development scenarios: A machine learning-based simulation approach. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Jiang, Y.F.; Liu, Y.Q.; Sun, Y.C.; Li, C.J. The impact of landscape spatial morphology on green carbon sink in the urban riverfront area. Cities 2024, 148, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.J.; Helmus, M.R.; Behm, J.E. Green infrastructure space and traits (GIST) model: Integrating green infrastructure spatial placement and plant traits to maximize multifunctionality. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choi, Y.; Sung, H.C.; Yoo, Y.; Lim, N.O.; Kim, Y.; Shin, Y.; Jeong, D.; Sun, Z.; Jeon, S.W. Evaluation of the function of suppressing changes in land use and carbon storage in green belts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 187, 106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.W.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.B.; Wu, Y.F.; Wang, J.W.; Wu, S.D.; He, Y.M. Urbanization promotes carbon storage or not? The evidence during the rapid process of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 121061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.W.; Shao, Z.F.; Li, D.R.; Huang, X.; Altan, O.; Wu, S.X.; Li, Y.Z. Isolating the direct and indirect impacts of urbanization on vegetation carbon sequestration capacity in a large oasis city: Evidence from Urumqi, China. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 26, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, T.; Haase, D.; Lausch, A. Effectiveness trade-off between green spaces and built-up land: Evaluating trade-off efficiency and its drivers in an expanding city. Remote. Sens. 2025, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, C.; Chen, G.; Singh, K.K. The impact of urban residential development patterns on forest carbon density: An integration of LiDAR, aerial photography and field mensuration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 136, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.W.; Wang, L.; Stathopoulos, T.; Marey, A.M. Urban microclimate and its impact on built environment—A review. Build. Environ. 2023, 238, 110334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, R.; Rui, J.; Yu, Y. Revealing the impact of urban spatial morphology on land surface temperature in plain and plateau cities using explainable machine learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 118, 106046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, Z.W.; Wu, X.G.; Wang, J.; Zhang, P.D.; Ma, D.; Liu, Y. Building shading affects the ecosystem service of urban green spaces: Carbon capture in street canyons. Ecol. Model. 2020, 431, 109178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I.D.; Oke, T.R. Local climate zones for urban temperature studies. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2012, 93, 1879–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Li, Y.G. The impact of building density and building height heterogeneity on average urban albedo and street surface temperature. Build. Environ. 2015, 90, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.F.; Liu, Y.Q.; Sun, Y.C.; Li, X.H. Distribution of CO2 Concentration and its spatial influencing indices in urban park green space. Forests 2023, 14, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.G.; Huang, H.S.; Tu, K.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.H.; Yang, Q.S.; Acerman, A.C.; Guo, N.; et al. Effects of plant community structural characteristics on carbon sequestration in urban green spaces. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhang, S.Q. Assessing and explaining rising global carbon sink capacity in karst ecosystems. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 477, 143862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Q.; Huang, Y. Determinants of soil organic carbon sequestration and its contribution to ecosystem carbon sinks of planted forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 3163–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.H.; Wang, C.; Sun, Z.K.; Hao, Z.Z.; Day, D.S. How do urban forests with different land use histories influence soil organic carbon? Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 83, 127918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Wang, L.Y.; Li, R.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, D.S. Unveiling the nonlinear relationships and co-mitigation effects of green and blue space landscapes on pm2.5 exposure through explainable machine learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 122, 106234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, A.; Talvitie, I.; Ottelin, J.; Heinonen, J.; Junnila, S. Carbon sequestration and storage potential of urban residential environment—A review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84, 104027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Cai, J.; Xu, Y.M.; Liu, Y.H.; Yao, M.M. Carbon sinks in urban public green spaces under carbon neutrality: A bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.Q.; Liu, S.G.; Zhou, D.C. Prevalent vegetation growth enhancement in urban environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 2016, 113, 6313–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, E.Y.; Yao, J.; Zhang, X.H.; Chen, L.S. Explore the spatial pattern of carbon emissions in urban functional zones: A case study of Pudong, Shanghai, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Li, X.; Liu, X.P.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, M. Tele-connecting China’s future urban growth to impacts on ecosystem services under the shared socioeconomic pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Liu, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Clinton, N.; Ji, L.; Li, W.; Bai, Y.; et al. Stable classification with limited sample: Transferring a 30-m resolution sample set collected in 2015 to mapping 10-m resolution global land cover in 2017. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. 1 km monthly temperature and precipitation dataset for China from 1901 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yang, K.; Tang, W.J.; Lu, H.; Qin, J.; Chen, Y.Y.; Li, X. The first high-resolution meteorological forcing dataset for land process studies over China. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Woodward, F.I. Dynamic responses of terrestrial ecosystem carbon cycling to global climate change. Nature 1998, 393, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.Q.; Pan, Y.Z.; Zhang, J.S. Estimation of net primary productivity of Chinese terrestrial vegetation based on remote sensing. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2007, 31, 413–434. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.L.; Chen, J.; Gao, F.; Chen, X.H.; Masek, J.G. An enhanced spatial and temporal adaptive reflectance fusion model for complex heterogeneous regions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 2610–2623. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.J.; Zhang, L.W.; Yan, J.P.; Wang, P.T.; Hu, N.K.; Cheng, W.; Fu, B.J. Mapping the hotspots and coldspots of ecosystem services in conservation priority setting. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.X.; Zhang, L.W.; Li, X.P.; Zhao, W.D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.Z.; Wang, H.; Jiao, L. A spatially explicit framework for assessing ecosystem service supply risk under multiple land-use scenarios in the Xi’an Metropolitan Area of China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 2754–2770. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, W.W.; Zhu, Z.D.; Sun, H.; Ma, B.R.; Yang, L. Development of machine learning models for the prediction of the compressive strength of calcium-based geopolymers. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, A.; Gregr, E.J.; Chan, K.M.A. Data leakage jeopardizes ecological applications of machine learning. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 1743–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcock, S.; Hooftman, D.A.P.; Neugarten, R.A.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Barredo, J.I.; Hickler, T.; Kindermann, G.; Lewis, A.R.; Lindeskog, M.; Martinez-Lopez, J.; et al. Model ensembles of ecosystem services fill global certainty and capacity gaps. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadf5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Teng, M.; Ji, H.; Zhang, J.; He, W.; Ye, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, P. High planting density and leaf area index of masson pine forest reduce crown transmittance of photosynthetically active radiation. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 20, e00759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukeš, P.; Stenberg, P.; Rautiainen, M. Relationship between forest density and albedo in the boreal zone. Ecol. Model. 2013, 261–262, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Wang, S.Q.; Dai, J.H.; Wang, J.B.; Chen, J.; Shugart, H.H. Forest Greening Increases Land Surface Albedo During the Main Growing Period Between 2002 and 2019 in China. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos 2021, 126, e2020JD033582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusinen, N.; Stenberg, P.T.; Korhonen, L.; Rautiainen, M.; Tomppo, E. Structural factors driving boreal forest albedo in Finland. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 175, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Liu, H.; Wu, J.; Lin, W.M. Investigating impacts of urban morphology on spatio-temporal variations of solar radiation with airborne LIDAR data and a solar flux model: A case study of downtown Houston. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 4359–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Akpinar, D.; Nakhli, S.A.A.; Bowser, M.; Imhoff, E.; Yi, S.C.; Imhoff, P.T. Improving stormwater infiltration and retention in compacted urban soils at impervious/pervious surface disconnections with biochar. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 360, 121032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Tang, S.; Zhang, J.; Guo, W. Quantifying the relationship between urban blue-green landscape spatial pattern and carbon sequestration: A case study of Nanjing’s central city. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, D.; Peng, L.; Li, X.; Song, T.; Zhan, F. Heterogeneity and Influencing Factors of Carbon Sequestration Efficiency of Green Space Patterns in Urban Riverfront Residential Blocks. Forests 2025, 16, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.Z.; Xiong, L.Y.; Zhuang, D.F.; Liu, X.Y. MODIS-based Approach to Estimate Terrestrial Gross Photosynthesis. Prog. Geogr. 2004, 23, 10–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Trusilova, K.; Churkina, G. The response of the terrestrial biosphere to urbanization: Land cover conversion, climate, and urban pollution. Biogeosciences 2008, 5, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T. Examining urban heat island relations to land use and air pollution: Multiple endmember spectral mixture analysis for thermal remote sensing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2013, 6, 1749–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.N.; Chang, Q.; Li, X.Y. Promoting sustainable carbon sequestration of plants in urban greenspace by planting design: A case study in parks of Beijing. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, A.; Vigevani, I.; Corsini, D.; Wężyk, P.; Bajorek-Zydroń, K.; Failla, O.; Cagnolati, E.; Mielczarek, L.; Comin, S.; Gibin, M.; et al. CO2-assimilation, sequestration, and storage by urban woody species growing in parks and along streets in two climatic zones. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C. Y Green-space preservation and allocation for sustainable greening of compact cities. Cities 2004, 21, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Bae, J.; Yoo, G. Urban roadside greenery as a carbon sink: Systematic assessment considering understory shrubs and soil respiration. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penne, C.; Ahrends, B.; Deurer, M.; Böttcher, J. The impact of the canopy structure on the spatial variability in forest floor carbon stocks. Geoderma 2010, 158, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.T.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Y.F.Z.; Kim, M.T.; Cui, X.L. Examining the Microclimate Pattern and Related Spatial Perception of the Urban Stormwater Management Landscape: The Case of Rain Gardens. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Wang, L.; Yao, Y.L.; Jing, Z.W.; Zhai, Y.L.; Ren, Z.B.; He, X.Y.; Li, R.N.; Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, Y.Y.; et al. Nonlinear relationships between canopy structure and cooling effects in urban forests: Insights from 3D structural diversity at the single tree and community scales. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 118, 106012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Bao, Y.; Qin, Z.; Xin, X.; Bao, Y.; Bayarsaikan, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chuntai, B. Modeling net primary productivity of terrestrial ecosystems in the semi-arid climate of the Mongolian Plateau using LSWI-based CASA ecosystem model. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2016, 46, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Detail | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Green space data | LULC in 2017 | https://data-starcloud.pcl.ac.cn (accessed on 12 October 2024) |

| Remote sensing data | Landsat 8 OLI | https://www.gscloud.cn/ (accessed on 24 March 2023) |

| MOD09A1 | https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 24 March 2023) | |

| Sentinel-2 | https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 20 October 2024) | |

| Forest stand type data | Evergreen-broadleaf forest | Classified using machine learning algorithms based on Sentinel-2 remote sensing imagery and ground-truth samples |

| Evergreen-needleleaf forest | ||

| Deciduous-broadleaf forest | ||

| Deciduous-needleleaf forest | ||

| Meteorological data | Monthly maximum temperature | http://www.geodata.cn (accessed on 24 March 2023) |

| Monthly average temperature | ||

| Monthly precipitation | ||

| Solar radiation | http://data.tpdc.ac.cn (accessed on accessed on 24 March 2023) | |

| Built-up spatial patterns data | Main road | https://www.openstreetmap.org/ (accessed on 2 November 2024) |

| Distribution of buildings | ||

| Population density | https://www.worldpop.org/ (accessed on 25 November 2024) | |

| Canopy structure data | Canopy height | Obtained by processing airborne LiDAR data |

| Canopy density | ||

| Leaf area index |

| Index | Description | Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| FVC | Percentage of the vertical projection area of vegetation on the ground within a unit area. | , where NDVI denotes the Normalised Difference Vegetation Index. denotes the NDVI for areas with no vegetation or bare land and that for areas with complete vegetation cover. |

| CD | Ratio of the vertical projection area of tree canopies on the ground to the total forest area, which serves as a key metric of forest structural attributes and density. | Obtained through the processing of LiDAR data. |

| LAI | Proportion of total plant leaf area per unit land area, which represents the quantity and distribution of plant leaves. | |

| CH | Vertical distance from the ground to the top of the plant canopy, which represents the growth condition of individual or collective plants. | |

| EBF | Characterised by their broad leaves that remain green throughout the year; exhibit extended periods of CS. | Ratio of evergreen-broadleaf forest area to total green space area within a community. |

| DBF | Shed their leaves during the non-growing season, resulting in pronounced seasonality in their CS capacity. | Ratio of deciduous-broadleaf forest area to total green space area within the community. |

| ENF | Characterised by their small needle-like leaves; exhibit extended and continuous periods of CS. | Ratio of evergreen-needleleaf species area to total green space area within the community. |

| DNF | Exhibits seasonal leaf abscission, resulting in pronounced seasonality in its CS process. | Ratio of deciduous-needleleaf species area to total green space area within the community. |

| Cohesion | Characterises the spatial continuity and degree of aggregation of vegetation distribution within the landscape. | Calculated by Fragstats 4.2 software. |

| Index | Description | Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| GR | Proportion of green space within the area | Ratio of total green spaces to land area within the community |

| BD | Density of building distribution within the area | Total base area of community buildings divided by the land area |

| PR | Proportion of area of all above-ground buildings to the land area; a key index of spatial utilisation intensity considering the number of building floors | Ratio of the total above-ground building area to the land area within the community |

| RD | Indexes the density of roads within the area | Ratio of the total length of major roads to the total land area within the community |

| PD | Number of people per unit area, representing the degree of population aggregation | Derived from WorldPop population density data |

| AT | Characterises the temperature conditions within the area | Calculated by the mean of the annual average temperatures for each community |

| TP | Indexes the annual precipitation levels within the area | Obtained by the mean of the annual total precipitation for each community |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, L.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Huang, J. Relationship Between Built-Up Spatial Pattern, Green Space Morphology and Carbon Sequestration at the Community Scale: A Case Study of Shanghai. Land 2025, 14, 2437. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122437

Peng L, Jiang Y, Li X, Li C, Huang J. Relationship Between Built-Up Spatial Pattern, Green Space Morphology and Carbon Sequestration at the Community Scale: A Case Study of Shanghai. Land. 2025; 14(12):2437. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122437

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Lixian, Yunfang Jiang, Xianghua Li, Chunjing Li, and Jing Huang. 2025. "Relationship Between Built-Up Spatial Pattern, Green Space Morphology and Carbon Sequestration at the Community Scale: A Case Study of Shanghai" Land 14, no. 12: 2437. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122437

APA StylePeng, L., Jiang, Y., Li, X., Li, C., & Huang, J. (2025). Relationship Between Built-Up Spatial Pattern, Green Space Morphology and Carbon Sequestration at the Community Scale: A Case Study of Shanghai. Land, 14(12), 2437. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122437