Abstract

Optimizing resource allocation is crucial for enhancing Total Factor Productivity (TFP). This study investigates the impact of differentiated industrial land supply (DILS) on industrial Total Factor Productivity (ITFP), a topic essential for optimizing territorial spatial layouts and promoting high-quality industrial development. Using panel data from 282 Chinese cities (2007–2021) and a Spatial Durbin Model (SDM), we analyze the spatiotemporal effects of this factor. The results indicate a weakening trend in DILS over time, with a spatial pattern of lower intensity in the east and higher intensity in the west, while ITFP shows an upward trend, with higher levels in the east. Nationally, increased DILS impedes ITFP growth, a finding with robust implications for alternative approaches. This impact demonstrates significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity: at the macro-scale, eastern China shows an inverted U-shape, while the central and western regions exhibit negative impacts. At the meso-scale, the Yangtze River Economic Belt shows negative effects, while the Yellow River Basin displays an inverted U-shape. At the micro-scale, major city clusters show varied relationships (inverted U-shaped, positive, or negative). We conclude that DILS generally hinders ITFP, with effects intensifying and varying significantly across narrowing spatial scales, underscoring the need for region-specific land policies to support high-quality industrial development. This study enriches our theoretical understanding of how resource allocation affects ITFP and provides practical guidance for optimizing industrial land use.

1. Introduction

Enhancing industrial Total Factor Productivity (ITFP) constitutes a primary pathway for achieving high-quality industrial development. It represents an important avenue for building a modernized economic system and advancing manufacturing prowess. However, China’s current Total Factor Productivity (TFP) growth rate remains at approximately 40–60% of that observed in developed European and American economies [1,2]. Technological progress and resource allocation efficiency stand as two key drivers of TFP growth. As China rapidly narrows its technological gap with global initiatives, the difficulty of achieving further technological breakthroughs intensifies. However, China’s administrative intervention has significant potential to improve resource allocation efficiency compared with market-dominated economies. Consequently, optimizing resource allocation has emerged as a central strategy for boosting TFP at the current development stage. In China, industrial land serves not only as a spatial carrier for the real economy and a key production factor but also as a strategic resource for attracting governmental investment. Its allocation patterns and supply methods are characterized by strong administrative intervention, which directly impacts the efficiency of industrial land utilization and related resource configurations [3,4]. Over the past three decades, the local government-led model of low-cost, low-threshold, large-scale homogeneous industrial land supply has significantly contributed to China’s rapid economic growth. Nevertheless, this extensive model has exacerbated land resource misallocation and hindered TFP improvement [5,6]. Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, optimizing land resource allocation and enhancing TFP have been consistently emphasized.

To reform this homogeneous supply paradigm, some local governments have explored differentiated industrial land supply (DILS) strategies tailored to distinct industrial characteristics. By establishing tiered land pricing structures, they create cost gradients across industries to indirectly screen users. For instance, Shanghai allocated 1297 mu of industrial land to Tesla in 2018 at CNY 750,000 per mu, slightly below the city’s average industrial land price of CNY 770,000 per mu that year. Similarly, Hefei supplied 1061 mu to BYD in 2022 at CNY 100,000 per mu, substantially undercutting the local average of CNY 260,000 per mu. Multiple provinces, including Jiangsu, have implemented differentiated pricing policies, permitting land premiums for priority industries to be set at 70% of the minimum standard price for corresponding land grades. The literature has examined the formation mechanisms and impacts of differentiated land supply. Research indicates that this strategy is driven by interregional development competition and land supply constraints [7], enhances spatial allocation efficiency of land resources, promotes industrial upgrading and regional coordination [8], and exerts an overall positive yet regionally variable effect on industrial green development [9].

As a strategy for construction land allocation, DILS is, in essence, a mechanism for resource allocation. Although direct analyses of its impact on TFP remain relatively scarce, research exploring the influence of resource allocation on TFP is well established and mature. Studies have demonstrated that resource allocation patterns significantly affect production efficiency, a finding substantiated across diverse fields, including agriculture, urban economics, and regional economics [10,11,12,13,14]. Specifically, the efficiency of resource allocation has been shown to exert a substantial influence on TFP and economic growth, whereas resource misallocation tends to undermine TFP growth potential and economic expansion [15]. Consequently, optimizing resource allocation is widely regarded as a critical pathway for enhancing overall productivity within an economy. Focusing on industrial economic development, a subset of research has examined the impact on industrial growth from perspectives such as resource allocation, resource misallocation, and resource allocation efficiency [15,16,17,18,19]. Further refining this lens, another research stream has concentrated specifically on land resource allocation. For instance, studies have analyzed the effects of land-use regulation and industrial land markets on industrial productivity [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Others have investigated the influence of specific supply mechanisms—such as the output-based land allocation policy (muchanlunyingxiong) and the standardized land parcel system (biaozhundi)—as well as issues of land resource mismatch and spatial mismatch on ITFP [26,27,28]. These inquiries have subsequently delineated the transmission channels of these effects, including technological innovation, structural optimization, and industrial agglomeration [29], while also revealing spatiotemporal heterogeneity from the perspectives of regional variation and dynamic evolution [9].

Despite enriching theories of resource allocation, TFP, and economic geography, the literature exhibits two critical gaps. First, few studies specifically examine DILS and its direct impact on ITFP. Second, systematic analyses of its spatiotemporal heterogeneity remain scarce, particularly multi-scalar regional comparisons spanning the macro-, meso-, and micro-levels. Addressing these gaps, this study investigates the impact and spatiotemporal heterogeneity of DILS regarding ITFP. Its marginal contributions manifest in three dimensions. First, it establishes a nationwide empirical foundation by measuring DILS and ITFP at the city level across 282 cities from 2007 to 2021, characterizing their spatiotemporal evolution to inform national policymaking. Second, it directly investigates the impact of DILS on ITFP, providing direct evidence on the relationship between DILS and ITFP. Third, it systematically examines spatial heterogeneity across hierarchical scales, including the eastern, central, western, southern, and northern regions at the macro-level; the Yangtze River Economic Belt and Yellow River Basin at the meso-level; and seven national city clusters at the micro-level, including the Yangtze River Delta. By incorporating the quadratic terms of core explanatory variables, the analysis explores the non-linear effects of these factors, offering scientific insights for spatiotemporally optimized land policies.

Given the above practical context and theoretical gaps, the remainder of this study is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the characteristics and theoretical analysis of DILS and constructs a theoretical framework for its impact on ITFP. Section 3 details the research methodology and data, including the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) and the measurement of core variables and data sources. Section 4 presents and discusses the results, covering the national-level impact and multi-scalar heterogeneous effects. Finally, Section 5 concludes by summarizing the key findings and proposing actionable policy implications, as well as directions for future research.

2. Characteristics and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Characteristics of DILS

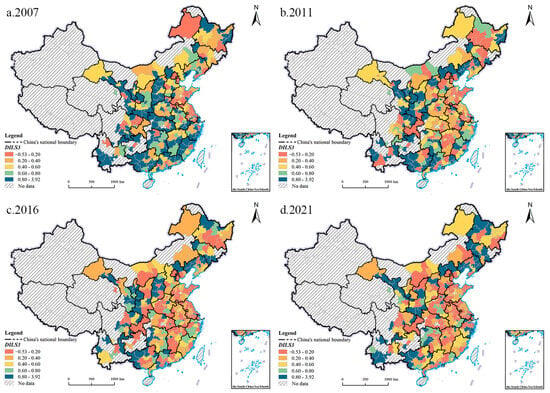

DILS is a strategy whereby local governments adopt varied land supply approaches encompassing methods, pricing, scale, and usage conditions for industrial projects. This strategy is implemented based on national development strategies, regional functional positioning, industrial policy orientation, and ecological conservation objectives. This study specifically focuses on price differentiation within this framework. Establishing differentiated land prices for distinct industries constitutes an operationally straightforward approach subject to minimal policy constraints. Under China’s prevailing land supply policies, legal frameworks, and institutional systems, this method can be implemented compliantly with low operational costs and manageable risks. Given that industrial land is primarily allocated through listing-based mechanisms, local governments retain substantial discretionary power in this process [30,31]. They frequently employ both overt and subtle micro-level interventions to extend price concessions, thereby attracting targeted industries to their jurisdictions [32,33]. This manifests concretely as preferential low-price land allocations for emerging industries aligned with national strategic priorities while simultaneously imposing elevated entry barriers for sectors characterized by overcapacity or high pollution levels. Alternative differentiated approaches such as flexible lease terms, rent-then-transfer arrangements, or hybrid lease–transfer models remain in exploratory phases [34]. These innovative models lack mature policy frameworks and standardized operational guidelines, representing frontier reforms undergoing continuous refinement. For local governments, implementing these alternatives incurs substantial institutional, managerial, and temporal costs spanning initial scheme design through post-transfer supervision, alongside inherent implementation risks. Consequently, price-differentiated supply has emerged as the predominant method for advancing sector-specific industrial development strategies within established policy frameworks. The empirical evidence presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2, with calculation methodologies elaborated in Section 2.2, demonstrates distinct characteristics in local governments’ differentiated pricing practices. Notably, the differentiation degree measured through the nine-category algorithm (DILS9) is lower than that derived from the three-category algorithm (DILS3). This measurement discrepancy indicates that broadening the definitional scope of high-tech industries reduces the observed intensity of differentiation. It further proves that high-tech sectors, particularly narrowly defined and consensus-based advanced industries, receive substantially differentiated treatment compared with traditional industries.

Figure 1.

Spatial and temporal variations in differentiated industrial land supply for three-category algorithm (DILS3). Source: Drawn by the authors.

Figure 2.

Spatial and temporal variations in differentiated industrial land supply for nine-category algorithm (DILS9). Source: Drawn by the authors.

2.2. Theoretical Analysis

2.2.1. Theoretical Framework

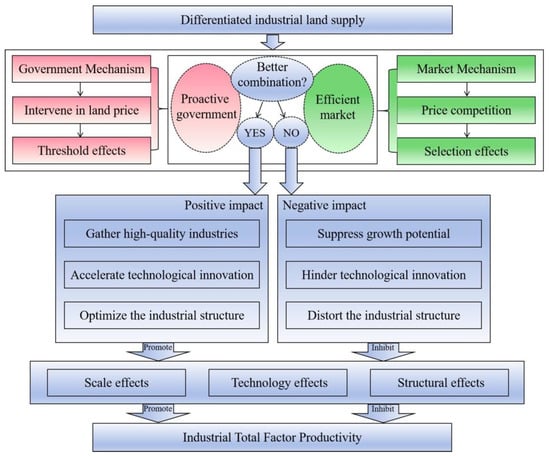

TFP fundamentally embodies the qualities of production factors such as technology and talent, coupled with the efficiency of resource allocation. It represents the comprehensive productivity of all elements within an economic system [16]. As China’s industrialization advances into a stage prioritizing quality and efficiency enhancement, driving high-quality industrial development necessitates extending TFP improvements to the industrial sector. ITFP specifically measures development efficiency after accounting for input factors and intermediate goods, encompassing two critical components: the rate of change in industrial resource allocation efficiency and industrial technological progress [35]. Consequently, elevating ITFP inherently relies on the structural reorganization of production factors and synergistic “technology–organization” innovation to achieve leaps in marginal output. DILS directly influences industrial enterprises through threshold effects and selection effects [36,37,38]. It subsequently impacts ITFP via three transmission mechanisms: scale effects, technology effects, and structural effects. Scale effects adjust the factor aggregation capacity of enterprise clusters through land supply elasticity. Technology effects encourage innovation in production functions via land-use barriers. Structural effects drive productivity differentiation through sector-targeted land allocation. The underlying connotations and specific influence mechanisms of these effects are detailed below. Figure 3 illustrates this theoretical framework.

Figure 3.

Theoretical framework. Source: Drawn by the authors.

As a hybrid government–market land supply instrument, DILS shapes ITFP through dual pathways. The government mechanism centers on policy intervention, creating threshold effects by guiding the agglomeration of priority industries aligned with local development plans through differentiated pricing and access restrictions while simultaneously raising entry barriers for inefficient, high-pollution, or energy-intensive sectors [3,36]. The market mechanism generates selection effects through price-based competitive screening, forcing inefficient firms to exit due to cost pressures and enabling surviving efficient firms to enhance aggregate productivity through resource reallocation [39]. Synergy between government and market mechanisms yields mutually reinforcing outcomes. Policy directives establish strategic priorities for market screening, while market forces ensure dynamic adaptability in resource allocation, collectively channeling production factors toward high-value-added sectors [40,41,42]. This synergy elevates ITFP by fostering industrial agglomeration, accelerating technological innovation, and optimizing industrial structures. Conversely, dysfunctional interaction between these mechanisms creates conflict and efficiency losses. Government interventions may supplant market screening functions, while market failures exacerbate rigid resource misallocation, collectively trapping production factors in inefficient sectors [43,44]. This dynamic suppresses ITFP through intensified industrial homogenization, stifles innovation vitality, and entrenches structural rigidities. Specifically, the positive and negative impacts generated through scale effects, technological effects, and structural effects are as follows:

- (1)

- Positive impacts: With scale effects, differentiated supply spatially concentrates firms, reducing inter-firm transaction costs and logistics expenses, thereby enabling specialization and economies of scale [45]. Market competition further refines firm selection, reallocating resources toward high-productivity sectors [46,47]. With technological effects, reduced land costs free up capital for R&D investment in high-tech firms, accelerating technology spillovers and diffusion within agglomerated spaces [48]. Concurrently, competitive pressure compels traditional firms to undertake technological upgrades. With structural effects, differentiated pricing promotes industrial upgrading toward higher value-added activities, optimizes cross-sector resource allocation efficiency, and fosters a synergistic development pattern integrating traditional industry enhancement with emerging industry expansion [39]. Market mechanisms dynamically steer resources toward high-return fields.

- (2)

- Negative impacts: With scale effects, excessive administrative intervention may divert land resources toward connected yet inefficient relationship firms, distorting price signals and undermining the market’s screening function [49]. Subsidy-dependent zombie firms occupy land quotas, eroding potential scale economies from agglomeration. With technological effects, market distortions may distort technological upgrade pathways. Traditional firms facing elevated land costs curtail R&D expenditures, dampening innovation incentives [50]. High-tech firms, incentivized to retain policy benefits, may prioritize short-term imitative projects over fundamental innovation to secure subsidies or preferential land [51]. Over-suppression of traditional industries risks supply chain fragmentation, increasing production costs for high-tech firms and diminishing technology-driven TFP contributions. With structural effects, adverse selection may emerge where inefficient emerging firms acquire low-cost land through rent-seeking, while efficient traditional firms exit [40]. This not only directly lowers aggregate TFP but also disrupts regional industrial chain integrity, heightening vulnerability and industrial hollowing. Prolonged policy support for inefficient firms further diverts resources toward regulatory compliance rather than substantive innovation, reinforcing path dependency and creating structural bubbles [38].

2.2.2. Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity

Analyzing the impact of DILS on ITFP necessitates explicit consideration of spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Significant regional disparities in economic development levels, land resource endowments, and external trade advantages, combined with dynamic shifts in policy environments and market conditions over time, demand granular analysis across temporal and spatial dimensions [52,53].

Temporal heterogeneity arises because the impact is not static but rather evolves dynamically with macroeconomic fluctuations, policy adjustment cycles, industrial development stages, and market demand variations [3]. During periods of economic prosperity or policy encouragement, robust market demand, abundant capital liquidity, and strong governmental support synergistically enhance the effectiveness of differentiated supply in optimizing resource allocation and fostering industrial agglomeration, thereby significantly boosting ITFP. Conversely, under economic downturns or policy tightening, weakened market demand, capital constraints, and increased regulatory restrictions diminish policy effectiveness. The pace of technological innovation and industrial upgrading further modulates temporal efficacy. During phases of rapid technological advancement, differentiated supply channels resources more efficiently toward innovative, efficient, and environmentally sustainable enterprises, accelerating ITFP gains. In contrast, periods of technological stagnation constrain potential benefits.

Spatial heterogeneity stems from China’s pronounced regional economic disparities, often characterized as a dual-track development pattern. Vast differences in industrialization levels across regions lead to significant geographical variation in policy outcomes [4]. In economically advanced regions featuring optimized industrial structures and vibrant innovation ecosystems, firms typically possess superior technological capabilities, higher resource utilization efficiency, and greater market adaptability. Consequently, differentiated land supply policies in these contexts are more effectively leveraged by enterprises to achieve substantial ITFP improvements. By contrast, less developed regions marked by monolithic industrial structures and weaker innovation capacities present firms with challenges such as capital scarcity, technological bottlenecks, and limited market access. These constraints inhibit firms’ ability to capitalize on policy incentives, attenuating the TFP-enhancing impact of differentiated supply. Uneven policy implementation, underdeveloped market institutions, and inherent resource scarcities prevalent in these areas further exacerbate spatial heterogeneity.

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Research Methodology

Given the spatial spillover characteristics inherent to ITFP (TFP), this study adopts spatial econometric models for empirical analysis. Common spatial econometric specifications include the Spatial Error Model (SEM), Spatial Lag Model (SLM), and Spatial Durbin Model (SDM). The SDM framework represents a more general form that encompasses SEM and SLM, effectively capturing relationships between variables. Consequently, we construct an SDM specification, with subsequent model selection guided by diagnostic test outcomes to examine the impact of DILS on ITFP. The formal expression of the SDM is provided by Equation (1):

In Equation (1), ITFPit denotes the dependent variable, representing ITFP. DILSit constitutes the core explanatory variable, measuring local governments’ DILS. β0 signifies the constant term. γ represents the spatial autoregressive coefficient, quantifying the influence of neighboring units on the dependent variable of the focal unit. Wij is the spatial weight matrix, where captures the interactive effects of the dependent variable between city i and city j. β1 and β2 are regression coefficients. X denotes the matrix of control variables. θ1 and θ2 indicate the spatial lag coefficients of the core explanatory and control variables, respectively. λi accounts for spatial fixed effects, μt for time fixed effects, and εit for the stochastic error term.

This study employs a contiguity-based weight matrix as the primary spatial weight matrix, where Wij = 1 if cities i and j share a common border, and Wij = 0 otherwise. This selection is justified by the results in Section 4.1.2, which demonstrate that Moran’s I indices of the core variables attain maximal absolute values under the contiguity matrix, indicating the most pronounced spatial effects. Robustness checks further utilize geographical distance matrices, economic distance matrices, and geographical–economic nested matrices [4,38,54]. Following methodological guidelines established by Elhorst and related studies [55], the spatial econometric estimation procedure comprises three sequential steps. First, Lagrange Multiplier (LM) and robust LM tests determine whether spatial econometric models are statistically warranted. Second, Likelihood Ratio (LR) and Wald tests identify the optimal model specification between SDM, SEM, and SLM. Third, the Hausman test discriminates between fixed-effects and random-effects estimators.

3.2. Variable Description and Data Sources

3.2.1. Variable Description

The dependent variable is ITFP (ITFP). This study employs Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) to measure ITFP for the following reasons [56,57]. The traditional Solow Residual Approach (SRA) assumes all production units operate on the technological frontier, failing to distinguish between technical efficiency losses and stochastic shocks, which may overestimate or underestimate actual efficiency. While Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) requires no preset production function and accommodates multiple inputs and outputs, it entirely neglects stochastic elements, rendering results vulnerable to outlier distortion. By contrast, SFA employs a parametric production function and a composite error term. This framework quantifies technical efficiency losses while filtering out disturbances from uncontrollable random factors. Therefore, it is better suited for the complex and uncertain production environments characteristic of the industrial sector. Furthermore, SFA supports statistical tests to validate model specification, yielding results with greater economic interpretability and robustness. This study adopts the panel data SFA model framework established by Battese and Coelli. A translog production function form is specified. This form offers greater flexibility than the Cobb–Douglas specification, as it does not impose a priori restrictions on substitution elasticities and can better approximate actual production technology:

where i denotes the city, and t denotes the year. Outputit is the desirable output, measured by real industrial GDP (CNY 100 million, deflated using 2007 as the base year). Input factors include the following: (1) industrial capital stock (Kit, CNY 100 million), calculated using the perpetual inventory method, Kit = Iit + (1 − δ)Kit, where Iit is the real fixed asset investment in year t; (2) industrial employment (Lit, 10,000 persons); and (3) industrial energy consumption (Eit, 10,000 tons of standard coal equivalent). T is a time trend term included to capture technological progress. vit is the classic random error term, assumed to be independently and identically distributed as vit ~ i.i.d. N(0, ). uit ≥ 0 is the non-negative technical inefficiency term, representing the distance of actual output from the theoretical maximum frontier output, and it is assumed to follow a non-negative truncated normal distribution uit ~ N+(μ, ).

The growth rate of ITFP is jointly determined by changes in technical efficiency and the rate of technological progress. After estimating the model parameters via maximum likelihood, the technical efficiency (TE) for city i in year t can be calculated by the conditional expectation, TEit = E[exp(−uit)|εit], where εit = vit − uit. This TE value ranges between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 indicating higher efficiency. The rate of technological progress (TP) is calculated as the partial derivative of the production function with respect to the time trend:

TPit represents a percentage change rate, which can be positive, negative, or zero, indicating the advancement, regression, or stagnation of the technological frontier, respectively.

The core explanatory variable is DILS (DILS). Drawing on the characteristics outlined in Section 2.1 and referencing relevant research [7], DILS measurement and data processing adhere to three principles. First, given inherent price disparities across locations, land grade differentiation must be incorporated when quantifying supply differentiation. Second, high-tech industrial sectors should be defined according to the Classification of High-Tech Industries (Manufacturing) issued by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, focusing on advanced manufacturing. Third, preliminary DILS estimates should be adjusted to disentangle the influence of economic fluctuations due to the strong correlation between land prices and regional economic development levels. The formal expression for the degree of price-differentiated supply is

In Equation (2), i denotes city, t year, and j land grade. NHTp and HTq represent land transaction prices for non-high-tech and high-tech industries, respectively. EDit indicates the economic development level of city i in year t. Based on industrial policy orientation and technological intensity, this study classifies three high-threshold sectors with strong innovation spillovers—pharmaceutical manufacturing, computer and communication equipment, and instrumentation (C27, C39, C40)—as high-tech industries. This classification reflects local governments’ targeted support for strategic emerging industries and is the basis for calculating DILS using Equation (2), generating the “three-category algorithm” variable (DILS3). DILS3 functions as the primary core explanatory variable in subsequent empirical analysis. To mitigate potential measurement bias from a single classification and verify robustness, high-tech industries are expanded to nine categories, including chemical raw materials, general equipment, and specialized equipment (C26, C27, C34, C35, C37, C38, C39, C40, C43). This broader classification is similarly applied to Equation (2), yielding the “nine-category algorithm” variable (DILS9).

Control variables referenced from prior studies encompass seven dimensions [3,4,17,27,29]. Economic development level (EDL) is measured by per capita GDP (10,000 CNY/person), influencing ITFP through capital availability for technological upgrades and market demand. Industrial structure (IS), represented by the ratio of secondary to tertiary industry output, affects ITFP via resource allocation efficiency. Population density (PD), calculated as year-end resident population (10,000 people) divided by administrative area (km2), influences ITFP through agglomeration effects and factor competition. The fiscal self-sufficiency rate (FSR), defined as the ratio of local general public budget revenue to expenditure, impacts ITFP through local government investment capacity and market interventions. Science and technology expenditure (STE), expressed as the percentage of urban science expenditure in total local general public budget expenditure, affects ITFP via technological innovation and resource conversion efficiency. Financial development level (FD), measured by the ratio of year-end financial institution loan balances to regional GDP, influences ITFP through financing efficiency and capital allocation. Informatization level (IL), gauged by the number of broadband internet subscribers (10,000 households/city), affects ITFP by optimizing production processes and enabling technology adoption.

3.2.2. Data Sources

The DILS data originate from the China Land Market Net (www.landchina.com), a nationwide construction land transaction information platform established by the Ministry of Natural Resources. This comprehensive database records every parcel-level land transaction conducted by local governments across China, including detailed information on land area, price, and designated use. A total of over 650,000 industrial land transaction records spanning 2007 to 2021 were systematically extracted. High-tech and non-high-tech industrial sectors were classified according to the Industrial Classification for High-Tech Industries issued by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, based on industry categories. Data required for ITFP calculation and control variables were sourced from the China Macroeconomic Database (https://ceidata.cei.cn) administered by the State Information Center’s China Economic Information Network, supplemented by the China City Statistical Yearbook, the China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy, and relevant annual statistical bulletins on national economic and social development or government work reports issued by their respective cities.

3.2.3. Research Sample

Considering data availability, this study employs 282 prefecture-level cities and municipalities directly under the central government as fundamental research units, covering the period 2007–2021. This sample selection is justified by three considerations. First, China’s Urban Management Law explicitly designates city- and county-level local governments as entities holding land conveyance authority. While municipal-level data are readily accessible, county-level data acquisition presents significant challenges. Consequently, this study aligns with prevailing research practices by utilizing city-level data [4,38]. Second, as high-level administrative units with unique land market dynamics and economic activities, municipalities directly under the central government retain land conveyance authority. Their inclusion enables a more comprehensive understanding of differentiated land supply strategies. Third, data scarcity for certain prefecture-level cities in remote regions necessitated the final selection of 282 prefecture-level and higher cities. The year 2007 marks the starting point because the China Land Market Net achieved nationwide coverage that year, consistent with established research protocols [4,42]. The 2021 endpoint was determined using the latest available data in statistical yearbooks. Additionally, the data for this study were gathered from multiple sources. Rigorous data cleaning and validation procedures were conducted to construct a balanced panel dataset, ensuring the quality of the final dataset. Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable construction process and descriptive statistical analysis results.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Core Variables

4.1.1. Temporal Characteristic Analysis

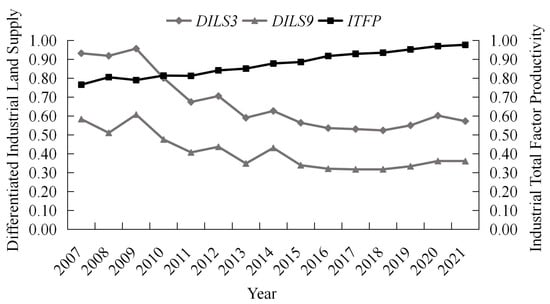

Figure 4 illustrates that the degree of DILS (DILS3 and DILS9) exhibits a gradual decline from 0.57 in 2007 to 0.36 in 2021, representing an average annual decrease of approximately 3.65%. This trend indicates a narrowing gap between land prices for non-high-tech and high-tech industries under local government intervention, reflecting a systematic reduction in governmental intervention intensity. In areas with identical land grades, market dynamics typically assign higher land prices to high-tech industries due to their greater value-added capacity and ability to absorb elevated land costs. Strong governmental intervention historically distorted this pattern by granting excessive concessions to high-tech sectors while imposing higher barriers on non-high-tech industries, resulting in artificially lower land prices for high-tech uses. The diminishing differentiation suggests reduced preferential treatment for high-tech industries or lowered thresholds for non-high-tech sectors, signifying weakened price intervention and enhanced marketization. This aligns with the 19th CPC National Congress’s emphasis on market-oriented factor allocation as a key reform task and the State Council’s Comprehensive Reform Pilot Plan for Market-Oriented Allocation of Production Factors (Guobanfa [2021] No. 51), collectively indicating progressive refinement of market mechanisms for industrial land allocation. Nevertheless, localized fluctuations reveal non-linear policy adjustments. For instance, transient increases in DILS3 and DILS9 occurred in 2009 and 2020, likely linked to strengthened industrial support policies following the 2008 global financial crisis and temporary relief measures during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. During economic downturns, local governments implemented targeted interventions such as enhanced land concessions for high-tech industries to mitigate market failures. Such countercyclical measures remained short-term and failed to reverse the overarching declining trajectory.

Figure 4.

Trends in differentiated industrial land supply and industrial Total Factor Productivity. Source: Drawn by the authors.

As depicted in Figure 4, ITFP (ITFP) demonstrates a sustained upward trajectory from 0.77 in 2007 to 0.98 in 2021, with an average annual growth rate of 1.74%. As noted in Section 2.2, ITFP growth primarily derives from technological progress and optimized resource allocation efficiency. This improvement may be due to two factors: diminishing governmental intervention in industrial land supply, enabling market-driven optimization of resource allocation, and strategic industrial transformation toward high-quality development, enhancing innovation capacity. However, growth momentum displayed significant phase-specific variations. The annual growth rate averaged 1.7% in 2007–2010, edged up to 1.8% in 2010–2012, but plummeted to 1.0% in 2021, signaling marginal diminishing pressures. Potential causes include efficiency gains from resource allocation approaching diminishing returns and escalating innovation difficulties as China transitions from imitative innovation toward independent exploratory innovation.

A “reversed dynamic relationship” characterizes the interplay between these variables. Short-term enhancements in differentiation intensity corresponded with decelerated ITFP growth, while the long-term decline in differentiation coincided with steady ITFP expansion. For example, when DILS3 decreased by 0.08 units in 2012–2014, concurrent annual ITFP growth rose from 1.8% (2010–2012) to 2.0%. Conversely, a 0.07-unit rebound in DILS3 in 2017–2020 was concomitant with a decline in ITFP growth from 1.7% (2015–2017) to 1.3% (2017–2020), further dropping to 0.7% in 2021. This pattern suggests a potential negative correlation between DILS and ITFP.

4.1.2. Spatial Characteristics Analysis

The spatial distribution of DILS (DILS3 and DILS9) is detailed in Section 2.1 (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Significant spatial heterogeneity exists, revealing an “east—weak; west—strong” gradient pattern. Both Figure 1 and Figure 2 indicate that eastern regions are predominantly blue, reflecting weaker differential land supply intensity, while western regions are mainly red, indicating stronger differential land supply intensity. This pattern may stem from the relatively weak industrial structure foundation and locational advantages in western regions, necessitating more substantial land price incentives to attract high-tech industries compared to the east. In 2007, the overall differential land supply intensity was relatively high, but it decreased significantly by 2021; nevertheless, the east–west gradient pattern remained pronounced.

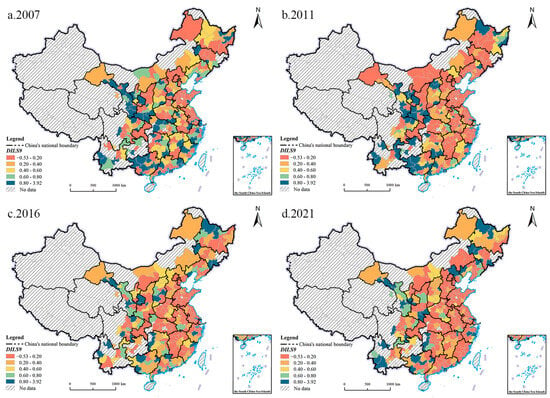

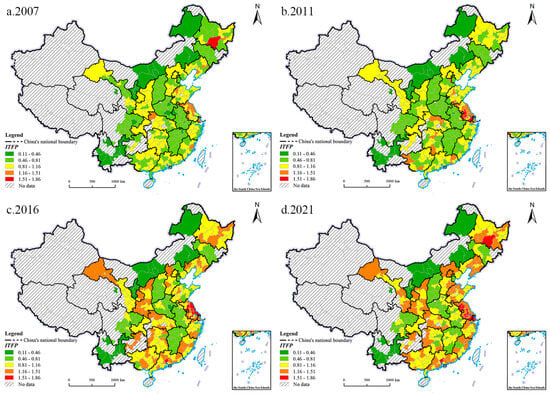

The spatial distribution of ITFP (ITFP) is shown in Figure 5. ITFP also exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity, characterized by an “east—high; west—low” gradient. Figure 5 demonstrates that eastern regions are primarily orange and red, indicating higher ITFP levels, while central and western regions are predominantly yellow and green, reflecting lower TFP levels. This disparity likely arises from higher technological innovation capacity and resource allocation efficiency in eastern regions. Although ITFP was generally low in 2007, it improved markedly by 2021, with the east—high/west—low gradient pattern persisting.

Figure 5.

Spatiotemporal variations in industrial Total Factor Productivity. Source: Drawn by the authors.

To further explore the spatial characteristics of DILS and ITFP—and to validate the prerequisites for spatial econometric modeling—this study employs Moran’s I index to identify spatial autocorrelation. Table 2 presents the spatial autocorrelation test results for the annual averages of the two core variables from 2007 to 2021. Regardless of the spatial weight matrix applied, the Moran’s I indices for both DILS and ITFP are statistically significant at the 1% or 10% level, confirming significant positive spatial autocorrelation in these variables.

Table 2.

Spatial autocorrelation tests for core variables.

4.2. National-Level Effects

A series of tests, including the Lagrange Multiplier (LM), Likelihood Ratio (LR), Wald, and Hausman tests, was conducted, sequentially guiding the selection of a fixed-effects Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) for regression analysis (The full results are available from the authors upon request.). The national-level regression results from the SDM are shown in Table 3. Regardless of whether the contiguity matrix, geographic distance matrix, economic distance matrix, or nested matrix is used, the coefficients of the core explanatory variables (DILS3 and DILS9) are negative and statistically significant at the 5% level. The regression coefficients for DILS3 are −0.0120, −0.0127, −0.0124, and −0.0126, while those for DILS9 are −0.0186, −0.0197, −0.0184, and −0.0188. This indicates that DILS has a significant negative impact on ITFP. To mitigate potential endogeneity issues, such as simultaneous causality, we performed regression analysis using the one-period lagged variable of DILS (L.DILS3 and L.DILS9). The results, presented in Table 4, are largely consistent with those in Table 3, confirming the robustness of the regression findings. We hypothesize that this negative impact may arise because an increase in the degree of differentiation intensifies government intervention, which could subsequently reduce resource allocation efficiency and hinder the improvement of ITFP. Combined with the characteristics evident in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 4—showing a gradual decline in the degree of land supply differentiation—the results suggest that reducing the degree of DILS can significantly enhance ITFP. In other words, as the degree of differentiation gradually decreases, excessive administrative intervention weakens, the market-screening function of land prices strengthens, and a more effective synergy between government and market mechanisms is achieved. This facilitates the release of scale, technology, and structural effects from industrial agglomeration, thereby promoting the growth of ITFP.

Table 3.

Regression results: Impact of differentiated industrial land supply (DILS3/DILS9) on industrial Total Factor Productivity.

Table 4.

Robustness test.

To examine potential temporal heterogeneity in this relationship, the quadratic terms of the core explanatory variables (DILS32 and DILS92) were incorporated into the model. The regression results in Table 5 show that both the linear (DILS3 and DILS9) and quadratic terms (DILS32 and DILS92) are significantly negative at the 10% or 15% level across all spatial matrices. This implies that the TFP-enhancing effect of reducing DILS does not exhibit an inflection point but instead operates as a persistent and intensifying force. A plausible explanation is that as policy intervention recedes, market-based resource allocation gains momentum, with minimal government distortion and efficient market coordination jointly accelerating ITFP growth [3,58].

Table 5.

Regression results with quadratic terms: impact of differentiated industrial land supply on industrial Total Factor Productivity.

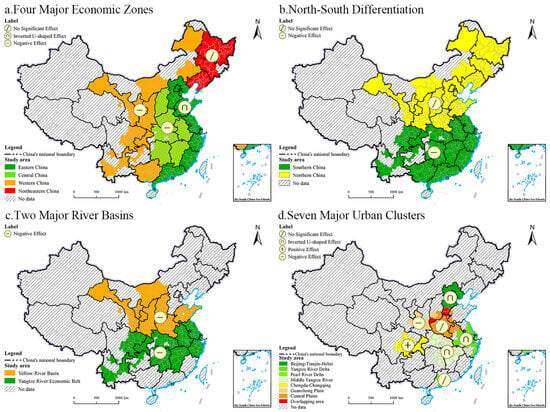

4.3. Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity Effects

To systematically test whether the impact of DILS on ITFP varies across different geographical and economic contexts, this study constructs a three-scale “macro–meso–micro” spatial analytical framework of (Figure 6). The design of this framework is based on the following considerations. On the one hand, China’s regional development exhibits the distinct characteristics of “regional block disparities” (macro-scale), “strategic axis differentiation” (meso-scale), and “cluster-based development” (micro-scale). The effect of DILS is likely to be heterogeneous due to the influence of structural factors at these different scales, such as the stage of development, resource endowment, degree of economic agglomeration, and level of integration. On the other hand, this framework aligns directly with regional strategies and governance units at different national administrative levels, thereby enhancing the policy relevance of the research. Specifically, (1) at the macro-scale, divisions are made according to the four major standard economic regions (eastern, central, western, and northeastern China) and the geographical north–south divide [5,59]. (2) At the meso-scale, the focus is on the Yangtze River Economic Belt and the Yellow River Basin [60,61], two typical river basins covered by national strategies. (3) At the micro-scale, seven national-level city clusters approved by the State Council are selected: Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei, the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, Chengdu–Chongqing, the Yangtze River Midstream, the Guanzhong Plain, and the Central Plains [62,63]. The regression results for the different spatial scales are presented in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 and are summarized schematically in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Summary map of the multi-scale research areas and heterogeneous regional impacts. Source: Drawn by the authors.

Table 6.

Regression results at regional level.

Table 7.

Regression results at basin level.

The regression results for regions divided at the macro-scale (Table 6) indicate significant heterogeneity in the impact of DILS on ITFP across the four major economic regions. The eastern region exhibits a significant “inverted U-shaped” pattern. Taking the results from the geographical distance matrix as an example, the coefficient for the linear term of DLPS3 is 0.0305 (p < 0.05), and the coefficient for the quadratic term is −0.0229 (p < 0.01). The calculated inflection point is located at approximately DLPS3 ≈ 0.67, highlighting the marginal cost of excessive intervention. In contrast, the central and western regions show a significantly negative linear impact: the DLPS3 coefficient for the central region ranges from −0.0139 to −0.0220 (p < 0.1~0.05), and for the western region from −0.0127 to −0.0152 (p < 0.1~0.05). This implies that a one-unit increase in DLPS3 may reduce ITFP by approximately 1.3 to 2.2 percentage points. No statistically significant impact is observed in the northeast region. Regarding the north–south divide, the southern region shows a significantly negative DLPS3 coefficient in the linear model (approximately −0.016, p < 0.05) and a significantly negative quadratic term coefficient in the quadratic model (approximately −0.009, p < 0.05), suggesting a potential accelerating negative non-linear relationship. No statistically significant effect is observed in the northern region.

According to the regression results for river basins divided at the meso-scale (Table 7), the Yellow River Basin shows a marginally negative linear relationship in the quadratic model, with DLPS3 coefficients ranging from −0.0168 to −0.0178 (p < 0.15~0.05). The Yangtze River Economic Belt, however, exhibits a significant non-linear pattern: the quadratic term coefficients are consistently negative (approximately −0.0072 to −0.0080, p < 0.1~0.05), while the linear terms are not significant. This indicates that DILS may have a diminishing marginal inhibitory effect on TFP, rather than an inverted U-shaped pattern of initial promotion followed by inhibition.

The regression results for city clusters divided at the micro-scale (Table 8) reveal that the Chengdu–Chongqing city cluster demonstrates a consistently positive and significant DLPS3 coefficient (0.0430~0.0679, p < 0.1~0.01). A one-unit increase in DLPS3 could enhance TFP by approximately 4.3 to 6.8 percentage points. The Yangtze River Delta city cluster displays a clear inverted U-shaped pattern: using the geographical distance matrix results, the linear term coefficient is 0.0624 (p < 0.05), and the quadratic term coefficient is −0.0412 (p < 0.05), with an inflection point at DLPS3 ≈ 0.76. For the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei city cluster, the quadratic term coefficients are significantly negative and have the largest absolute values among all models (e.g., −0.1307 for the geographical distance matrix, p < 0.01), indicating its inverted U-shaped curve is the steepest and that this region is extremely sensitive to the intensity of DILS. The Yangtze River Midstream city cluster shows an inverted U-shaped pattern, with the quadratic term being significantly negative under certain matrices. The Guanzhong Plain city cluster exhibits a significantly negative linear impact, with the effect size (a 5.1% to 6.2% decrease in TFP per one-unit increase in DLPS3) being the most pronounced among all regions. No statistically significant impact is observed for the Pearl River Delta and Central Plains city clusters.

Table 8.

Regression results at urban agglomeration level.

We posit that the potential reasons for these observed disparities are as follows. First, the inverted U-shaped effects in eastern China, the Yangtze River Delta, and Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei likely stem from their robust industrial foundations and initial synergy between market mechanisms and targeted land supply policies. Differential land provision reduces costs for high-tech enterprises, fosters industrial agglomeration, and enhances scale economies and technology spillovers [45], thereby elevating TFP. However, excessive administrative intervention beyond market-adjustment thresholds eventually triggers resource misallocation, congestion effects, and subsidy-dependent inefficiencies [49], which suppress TFP growth. In ecologically sensitive regions like the Middle Yangtze River, stringent environmental regulations increase firms’ compliance costs, crowding out R&D investments and further dampening TFP [50].

Second, the significantly negative impacts in central/western China and the Guanzhong Plain may be due to their pursuit of industrial relocation from eastern regions through differential land pricing. Inadequate supporting infrastructure (e.g., logistics networks and talent pools) impedes cluster formation, while high transaction costs undermine scale economies and market competitiveness. Consequently, inefficient firms persist through subsidies, exacerbating resource misallocation and hindering TFP growth [40]. Conversely, southern China and the Yangtze River Economic Belt exhibit mitigated negative effects due to their relatively market-oriented land supply systems, where reduced policy intervention strengthens market mechanisms and supports TFP enhancement.

Third, Chengdu–Chongqing’s uniquely positive effect benefits from strategic advantages under the “Twin-City Economic Circle” initiative. As a pivotal node connecting the Belt and Road Initiative and the Yangtze River Economic Belt—bolstered by the China-Europe Railway Express and New International Land–Sea Trade Corridor—it achieves synergistic policy–market integration. Strategic land supply lowers costs for high-tech industries, successfully attracting advanced manufacturing and strategic emerging sectors from eastern China [40,48]. This facilitates electronic and automotive industrial clusters, driving sustained TFP growth.

Finally, statistically insignificant effects in northeastern/northern China and the Central Plains may reflect counteracting socioeconomic and institutional forces. Industrial decline, talent outflows, stringent ecological and arable land protection policies, and intra-regional disparities likely neutralize local governments’ land supply adjustments, resulting in no net impact on ITFP.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

Based on panel data from 282 prefecture-level and above cities in China (2007–2021), this study employs an SDM to empirically examine the impact of DILS on ITFP and its spatiotemporal heterogeneity. This research not only expands our theoretical understanding of how resource allocation influences ITFP but also provides empirical evidence and policy insights for promoting high-quality industrial development through optimized industrial land allocation. The conclusions are summarized as follows.

First, regarding spatiotemporal characteristics of core variables, DILS intensity exhibits a declining temporal trend and a spatial “east—weak; west—strong” gradient. ITFP demonstrates an increasing temporal trajectory and a spatial “east–high; west–low” pattern. Both variables display significant spatial autocorrelation.

Second, at the national level, DILS exerts a significant negative impact on ITFP, with this effect intensifying over time. Robustness checks employing two methods to measure the degree of DILS (DILS3 and DILS9), multiple spatial weight matrices, and a lagged explanatory variable to alleviate potential endogeneity concerns all yield consistent conclusions.

Third, substantial spatiotemporal heterogeneity exists across scales. At the macro-regional scale, eastern China shows an inverted U-shaped relationship, central and western China exhibit negative effects, and northeastern China displays no significant impact. The north–south division reveals a significantly negative effect in southern China but no significant effect in the north. At the meso-basin scale, both the Yangtze River Economic Belt and the Yellow River Basin demonstrate a negative effect. At the micro-urban agglomeration scale, Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei, the Middle Yangtze River, and the Yangtze River Delta display inverted U-shaped relationships; Chengdu–Chongqing shows a positive effect; Guanzhong Plain exhibits a negative effect; and the Pearl River Delta and Central Plains present no significant effects.

5.2. Recommendations

Given the overall negative impact of localized DILS policies on ITFP and their significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity, we propose a shift from one-size-fits-all approaches to differentiated, refined policy optimization and dynamic, collaborative governance. Specific recommendations are outlined below.

To mitigate the adverse effects of DILS, policymakers should reduce governmental intervention and strengthen market-oriented mechanisms. This entails replacing administrative-led supply logic with a flexible land supply framework centered on enterprise productivity and market demand. Administrative preferences for specific industries and land-use classifications should be minimized. Establishing a secondary land market circulation system and promoting models such as “lease-before-transfer” and “long-term leasing” can reduce land allocation distortions. Concurrently, enhancing property rights protection and market-based pricing mechanisms—while minimizing non-economic interventions—will enable market-driven supply–demand adjustments to replace differential supply policies, thereby stimulating endogenous enterprise dynamism and TFP growth.

To address multi-scale spatiotemporal heterogeneity—where policy impacts amplify as spatial units narrow—a nested “macro–meso–micro” collaborative governance system is imperative. At the macro-level, a dynamic differential land quota adjustment mechanism should be established across the four major economic regions, accounting for north–south disparities. At the meso-level, the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins require dual eco-industrial adaptation strategies, balancing ecological constraints and industrial development. At the micro-level, urban agglomerations should develop cross-regional land quota trading platforms, with revenues directed toward traditional industry upgrades and ecological compensation to harmonize efficiency and spatial equity. Furthermore, a multi-scale policy simulation system powered by territorial spatial informatics should be deployed to model cross-level policy transmission effects. Digital twin technology can preempt conflicts (e.g., between ecological redlines and industrial agglomeration) and optimize policy compatibility. Through coordinated multilevel policy design and dynamic feedback, a governance paradigm of “macro-regional direction setting, meso-basin constraint enforcement, and micro-cluster linkage facilitation” will transform industrial land supply from fragmented management toward integrated efficiency enhancement, enabling spatially coordinated ITFP advancement.

5.3. Discussion

This study empirically examines the impact of DILS (DILS) on industrial Total Factor Productivity (TFP) and its spatiotemporal heterogeneity by constructing a multi-scale spatial analytical framework. The core finding reveals that, at the national level, an increase in the degree of DILS generally inhibits the improvement of ITFP, and this negative effect shows an intensifying trend. This key finding challenges the traditional policy assumption that solely relies on administrative price intervention to guide industrial upgrading and subsequently enhance productivity. Its theoretical significance lies in revealing that in a transitioning economy, when governments attempt to implement industrial policy by distorting factor prices (such as land), it may conflict with market-screening mechanisms. This can lead to resources failing to be allocated to the most productive sectors, thereby creating a paradox between governmental intent and market efficiency. By applying resource allocation theory specifically to the industrial land factor and utilizing spatial econometric models to capture policy spillover effects, this study deepens our understanding of how “resource misallocation” transmits through specific factor markets and ultimately affects macro-level productivity.

Methodologically, the contribution of this study lies in the systematic identification and quantification of spatiotemporal heterogeneity in the impact. By dividing the national sample into macro-regions, meso-river basins, and micro-city clusters, we found that the direction (positive, negative, or inverted U-shaped) and intensity of the impact significantly diverge as the spatial scale narrows. This methodological advancement indicates that the evaluation of land policy effects must go beyond an overall national or macro-regional perspective and deeply consider the moderating role of local contexts. For instance, the positive effect observed in the Chengdu–Chongqing city cluster may benefit from its unique strategic positioning and relatively complete industrial chain ecosystem, enabling targeted land concessions to effectively attract clusters of efficient firms. Conversely, the “inverted U-shaped” relationship in eastern regions suggests that moderate, market-compatible differentiated policies may be beneficial within a certain threshold, but excessive intervention turns detrimental. This multi-scale heterogeneity analysis framework provides an empirically referable path for future research on the effects of localized industrial policies.

However, this study has several limitations that point the way for future research. Although we employed various spatial weight matrices for robustness checks and conducted alternative measurements of core variables, potential endogeneity issues in the model—such as local governments possibly formulating DILS strategies based on anticipated productivity changes or industrial upgrading needs—require further consideration in future research by seeking more effective instrumental variables or constructing quasi-experimental designs using policy shocks. Furthermore, the mechanism analysis in this study is mainly based on theoretical deduction and indirect empirical patterns. Future work could more directly test how DILS ultimately affects productivity through specific channels, such as firm entry and exit, investment decisions, and innovative behaviors, using case studies or firm-level microdata.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and Q.W.; methodology, J.W.; software, J.W. and Y.L.; validation, Y.L. and H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, J.W. and H.W.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, H.W. and Q.W.; project administration, J.W. and Q.W.; funding acquisition, J.W. and Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number: 42301297; the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China, grant number: 22YJC630132; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number: 42571323.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Luckstead, J.; Choi, S.M.; Devadoss, S.; Mittelhammer, R.C. China’s catch-up to the US economy: Decomposing TFP through investment-specific technology and human capital. Appl. Econ. 2014, 46, 3995–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagnini, G.; Giombini, G.; Travaglini, G. The productivity gap among major european countries, USA and japan. Ital. Econ. J. 2021, 7, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Li, H.; Deng, Z. The impact of land leasing strategies on industrial green total factor productivity: Insights from Chinese cities. Land Use Policy 2025, 156, 107607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Yao, S.; Han, F.; Zhang, Q. Does misallocation of land resources reduce urban green total factor productivity? An analysis of city-level panel data in China. Land Use Policy 2022, 122, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Peng, C.; Liu, G.; Du, A.M.; Boateng, A. The impact of industrial land prices and regional strategical interactions on environmental pollution in China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 98, 103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Li, M. The impact of land resource mismatch and land marketization on pollution emissions of industrial enterprises in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Huang, J. Research on the competition strategy of local governments’ differentiated land leasing for investment attraction: Evidence from micro-level land transactions. J. China Univ. Geosci. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 21, 124–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Huang, J.; Zou, W. Selective land supply, industrial structure adjustment and urban innovation. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 24–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, J. Impact of local governments’ differentiated land pricing on industrial green development in the Yangtze River Delta: From both global and local perspectives. China Land Sci. 2023, 37, 51–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Heresi, R. Reallocation and productivity in resource-rich economies. J. Int. Econ. 2023, 145, 103843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S. A simple accounting framework for the effect of resource misallocation on aggregate productivity. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2012, 26, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollrath, D. How important are dual economy effects for aggregate productivity? J. Dev. Econ. 2009, 88, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britos, B.; Hernandez, M.A.; Robles, M.; Trupkin, D.R. Land market distortions and aggregate agricultural productivity: Evidence from Guatemala. J. Dev. Econ. 2022, 155, 102787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, M.; Escobal, J. The impact of Peru’s land reform on national agricultural productivity: A synthetic control study. Land Use Policy 2025, 157, 107619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryzhenkov, M. Resource misallocation and manufacturing productivity: The case of Ukraine. J. Comp. Econ. 2016, 44, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.T.; Klenow, P.J. Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in China and India. Q. J. Econ. 2009, 124, 1403–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lei, X.; Yang, F.; Zhao, N. Financial friction, resource misallocation and total factor productivity: Theory and evidence from China. J. Appl. Econ. 2021, 24, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Li, H. Government-led resource allocation and firm productivity: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2025, 90, 102638. [Google Scholar]

- Dheera-Aumpon, S. Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in ThaiLand. Asian-Pac. Econ. Lit. 2014, 28, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.-S.; Ho, W.K. Land-use planning and market adjustment under de-industrialization: Restructuring of industrial space in Hong Kong. Land Use Policy 2015, 43, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.; Russell, L.; Taylor-Russell, C. Market Activity and Industrial Development. Urban Stud. 1995, 32, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Russell, L.; Taylor-Russell, C. Land for Industrial Development; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.S.; Gallent, N. Industrial land planning and development in South Korea: Current problems and future directions. Third World Plan. Rev. 2000, 22, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howland, M. Planning for industry in a post-industrial world: Assessing industrial land in a suburban economy. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 77, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, N.G.; Hoelzel, N.Z. Smart growth’s blind side: Sustainable cities need productive urban industrial Land. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2012, 78, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, J.; Shao, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, Q. Impact of urban industrial land spatial misallocation on industrial total factor productivity in China. Resour. Sci. 2022, 44, 2511–2524. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Guo, G.; Peng, S.; Wang, J. Impact and mechanism of the standard land supply model on urban green total factor productivity: Empirical evidence from a PSM-DID approach. China Land Sci. 2023, 37, 56–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Y. Land use tournaments and urban green total factor productivity: Evidence from the reform in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 86, 794–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Ren, Z.; Wu, Y.; Luo, Q. Urban industrial land misallocation and green total factor productivity: Evidence from China’s Yellow River Basin regions. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2024, 63, 646–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liang, J.; Fang, J.; He, H.; Chen, F. How do industrial land price and environmental regulations affect spatiotemporal variations of pollution-intensive industries? Regional analysis in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 333, 130035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tian, L.; Cao, Y.; Yang, L. Industrial land supply at different technological intensities and its contribution to economic growth in China: A case study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Du, X. Strategic interaction in local governments’ industrial land supply: Evidence from China. Urban. Stud. 2016, 54, 1328–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Skitmore, M.; Song, Y.; Hui, E.C.M. Industrial land price and its impact on urban growth: A Chinese case study. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Policy evolution, key problems and reform path of market-oriented allocation of industrial land. Reform Econ. Syst. 2023, 3, 99–107. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Lv, B. Total factor productivity of Chinese industrial firms: Evidence from 2007 to 2017. Appl. Econ. 2021, 53, 6910–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, Y.; Gong, Y. How regional urban land misallocation impedes green technological progress: Cost effects and spatial strategic interaction. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Q.; Mei, L. How did development zones affect China’s land transfers? The scale, marketization, and resource allocation effect. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, H.; Song, M.; Ma, L. Intersecting sustainability and governance: The impact of industrial land price distortion on carbon emission efficiency in China. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 176, 103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Wang, J.; Sun, H.; Guo, Z. How does the spatial misallocation of land resources affect urban industrial transformation and upgrading? Evidence from China. Land 2022, 11, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Golosov, M.; Tsyvinski, A. Markets Versus Governments: Political Economy of Mechanisms; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, UK, 2006; p. 12224. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, A.W. Chapter 42 the land market and government intervention. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 3, pp. 1637–1669. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Land allocation and industrial agglomeration: Evidence from the 2007 reform in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2024, 171, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta-Chaudhuri, M. Market failure and government failure. J. Econ. Perspect. 1990, 4, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.D.T.S.; Chen, S.X.; Li, B.; Tang, S.H.K. Can land misallocation be a greater barrier to development than capital? Evidence from manufacturing firms in Sri Lanka. Econ. Model. 2023, 126, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Ben, T. Impact of government and industrial agglomeration on industrial land prices: A Taiwanese case study. Habitat. Int. 2009, 33, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J. Does the land price subsidy still exist against the background of market reform of industrial land? Land 2021, 10, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Qin, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, H. Can price regulation increase land-use intensity? Evidence from China’s industrial land market. Reg. Sci. Urban. Econ. 2020, 81, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Yuan, X.; Jing, Q. Impact of land prices on corporate carbon emission intensity. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Ma, W. Government intervention in city development of China: A tool of land supply. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Peng, S.; Yan, S.; Guo, G.; Wu, Q. Impact of chinese local government-led construction land supply strategies on urban innovation and its spatiotemporal differences. China World Econ. 2023, 31, 161–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Lin, R.; Zhu, D. Impact of rising industrial land prices on land-use efficiency in China: A study of underpriced land price. Land Use Policy 2025, 151, 107490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, B. Do land price variation and environmental regulation improve chemical industrial agglomeration? A regional analysis in China. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, D.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Land marketization and urban innovation capability: Evidence from China. Habitat. Int. 2022, 122, 102540. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Sieber, S.; Long, K. How does the concentration of spatial allocation of urban construction land across cities affect carbon emission intensity in China? Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhorst, J.P. Matlab software for spatial panels. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2014, 37, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampe, H.W.; Hilgers, D. Trajectories of efficiency measurement: A bibliometric analysis of DEA and SFA. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 240, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Yu, X. The Enigmas of TFP in China: A meta-analysis. China Econ. Rev. 2012, 23, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Jiang, X.; Gong, M. How land transfer marketization influence on green total factor productivity from the approach of industrial structure? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Shen, H.; Xin, Z.; Pan, Y. Trust and land Lease: The role of informal institutions in land market in rural China. Habitat. Int. 2025, 164, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, S.; Gong, X.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, R.; Duan, H.; Jiang, P. A comparative study of green growth efficiency in Yangtze River Economic Belt and Yellow River Basin between 2010 and 2020. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D.; Li, J. A comparative study on urban land use eco-efficiency of Yangtze and Yellow rivers in China: From the perspective of spatiotemporal heterogeneity, spatial transition and driving factors. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151, 110331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ma, S.; Zheng, Y.; Xiao, X. Integrated regional development: Comparison of urban agglomeration policies in China. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Wu, Q.; Wei, Y.D. How does industrial agglomeration affect urban land use efficiency? A spatial analysis of Chinese cities. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).