Abstract

Agricultural regions in humid tropical climates are often assumed to be water secure due to high annual rainfall, yet periodic drought remains a major constraint on production. This study demonstrates the application of the Normalized Difference Drought Index (NDDI) to identify drought-affected agricultural land in West Sumatera, Indonesia. Despite mean annual rainfall exceeding 3000 mm, rice yields in the Batang Anai Subdistrict declined from 5.28 t/ha in 2018 to 4.20 t/ha in 2022, suggesting an increased drought stress. A spatial analysis integrated administrative boundaries, land use maps, monthly rainfall records (2014–2023), and MOD09A1 V6 MODIS imagery. The NDDI was derived sequentially from the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI). The results show that 51.65% of agricultural land (7175 ha) exhibited average NDDI values of 0.09–0.14 over 2018–2023, with the highest drought intensity in 2022, when 4441 ha were classified as moderate drought. Land use under drought conditions was dominated by plantations (58.6%), rice fields (39.5%), and dry fields (1.9%). The NDDI method can more effectively capture localized drought impacts, making it valuable for operational drought monitoring systems. These findings highlight the vulnerability of humid tropical agricultural systems to drought and underscore the need for sustainable water management and early warning strategies based on remote sensing.

1. Introduction

Drought events in tropical regions have shown an increasing trend, driven by climate change, which affects agricultural output significantly. Several studies have been conducted to examine the significance of drought in agriculture, even in tropical regions that were historically less affected. Historical data reveal crop yield anomalies in response to multiscale drought indices, providing vital insights into vulnerable crop areas [1]; an extended dry season duration poses severe threats to crop growth and productivity, emphasizing the urgency for adaptive agricultural practices [2]. Drought can also be a direct threat to plant physiology [3,4] and affects various ecosystem types, including tropical forests, resulting in biomass loss and economic setbacks, particularly in agriculture and tourism [5]. Similarly, the discussion on the exacerbating effects of climate phenomena such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation on agricultural drought in the Peruvian Andes also emphasizes the importance of drought in tropical environments [6]. Moreover, other studies have indicated that the agricultural sector in tropical regions is not a monolithic entity; it comprises multiple cropping systems that react differently to drought stress. For instance, sugarcane hybrids show a significant variation in resilience to drought, emphasizing the importance of selecting appropriate genotypes that can withstand drought conditions [7]. A further study shows that the work on supplemental irrigation demonstrates that innovative management practices can enhance the water use efficiency of crops under drought stress, thus preserving food production during adverse climatic events [8].

Due to the significant impact of drought on agriculture in tropical areas, several studies have analyzed the effects of drought using various methods, for instance, emphasizing the correlation between agricultural drought risk and meteorological indices, specifically using the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) [9], exploring the interplay between hydrological and agricultural drought in the Corong River Basin [10], employing seasonal indices to study rainfed agriculture in the Athi-Galana-Sabaki River Basin [11], utilizing remote sensing technologies to monitor drought distributions in the Sukabumi Regency, Indonesia [12], assessing drought sensitivity using meteorological and vegetation indices in Dak Nong, Vietnam [13], analyzing drought impacts on water use efficiency across different climatic regions [14], examining the influence of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on agricultural drought in the Peruvian Andes [6], and studying the probabilistic linkages from meteorological and agricultural drought [15].

One of the factors hindering drought disaster mitigation in tropical areas is the difficulty in predicting the timing and duration of droughts in a particular region. The occurrence of multiple droughts has been attributed to the disparate distribution of rainfall within a specific region. This discrepancy in rainfall distribution has led to a disparity between the available water supply and the rice field production, particularly in regions with limited rainfall [16]. This phenomenon is indicative of the problems affecting rice production, with one hypothesis proposing a correlation with water availability due to drought, both meteorological and agronomic, despite the region’s reputation for high rainfall. Consequently, the identification of drought is imperative to facilitate the implementation of effective measures. Potential drought can be identified by using remote sensing [17], models based on long short-term memory (LSTM) [18], which provide observation data on a global and temporal scale, and the collection and processing of harmonized data [17]. The use of machine learning is also effective in drought monitoring [19] and drought forecasting [20], while demonstrating a high accuracy in capturing complex climatic dynamics. Nonetheless, these approaches exhibit certain limitations when using high-quality, high-resolution datasets [19], sporadic and incomplete datasets in rural areas [18], extensive feature engineering and the risk of model overfitting [20], and a lack of ground-based measurements for calibrating accurate models [21]. The variability in data quality can lead to discrepancies in drought assessments and reduce the effectiveness of predictive models. The Normalized Difference Drought Index (NDDI) has emerged as an effective tool for assessing agricultural land drought conditions by using Landsat imagery [22], drought intensity and behavior [23], and drought monitoring through remote sensing [12], offering real-time and adaptive modeling capabilities for evaluating agricultural droughts [24] and also providing accurate assessments of drought in tropical agricultural landscapes compared to traditional methods [25].

A study of data from the Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS) of the Padang Pariaman Regency reveals a downward trend in rice productivity in the Batang Anai Subdistrict from year to year. In 2018, rice productivity was documented at 5.28 tons per hectare. This figure subsequently declined in 2019 to 4.75 t/ha and subsequently increased in 2020 to 5.02 t/ha. In 2021 and 2022, productivity decreased to 4.44 and 4.20 tper ha, respectively [26]. This condition suggests problems impacting rice production, one of which is thought to be related to disruptions in water availability due to drought, both meteorologically and agronomically, although the region is known to have high rainfall, with an average monthly rainfall of 3000 mm [27]. This study aims to quantify and explain the spatial–temporal variability of drought stress in agricultural landscapes based on a case study of Batang Anai between 2018 and 2023 using remotely sensed indices (NDVI, NDWI, and NDDI). By integrating multi-year MODIS data with local climatic and land use information, we seek to (i) evaluate how vegetation and surface moisture dynamics interact under variable rainfall regimes and (ii) assess the potential of NDDI as a diagnostic tool for tropical agricultural drought monitoring and early warning. This approach extends beyond simple drought mapping by establishing a quantitative framework for understanding drought processes in high-rainfall environments, thereby contributing to improved water management and climate adaptation strategies for tropical agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

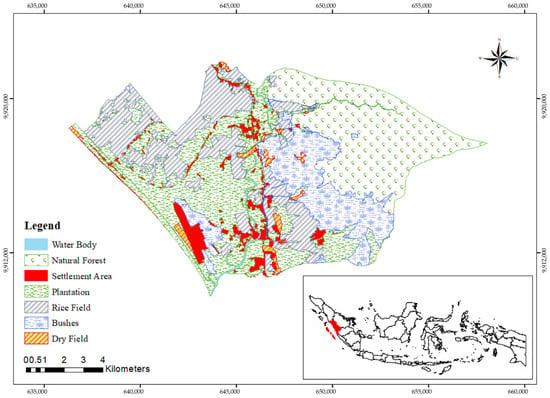

The Batang Anai Subdistrict, located in the Padang Pariaman Regency, is one of the areas with relatively high rainfall, with an average annual rainfall of 4009 mm over a 10-year period (2014–2023) [27]; notwithstanding, rice production exhibited a decline from 5.28 to 4.20 t/ha from 2018 to 2022 [26]. From an astronomical perspective, the Batang Anai Subdistrict is situated within the equatorial region, with its geographical coordinates ranging from 0°50′30″ North Latitude to 100°27′00″ East Longitude, and with an elevation range of approximately 0 to 1550 m above sea level. The mean minimum temperature in the study area is in the range of 21.34 °C, while the mean maximum temperature is in the range of 31.08 °C. The total research area obtained from the spatial data processing results of the Geospatial Information Agency (BIG) is 13,893 ha. The land use categories within the research area include eight types: rice fields (2932 ha), plantations (4039 ha), primary forest (3606 ha), settlements and activity areas (813 ha), scrubland (2116 ha), dry fields (204 ha), ponds (3 ha), and rivers (180 ha). Figure 1 presents a map delineating the land use within the Batang Anai Subdistrict. The present study focuses exclusively on the utilization of agricultural areas, specifically in the context of rice fields, plantations, and dry fields, which collectively encompass an area of 7175 ha.

Figure 1.

Land use map of Batang Anai Subdistrict. The land use map was created by overlaying the administrative boundary map with the land use map obtained from Geospatial Information Agency of West Sumatra. This overlay was created using ArcMap Ver. 10.8.

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Land Use Map of Batang Anai Subdistrict

The Batang Anai Subdistrict land use map was retrieved from the website www.tanahair.indonesia.go.id (accessed on 8 January 2025) in shapefile (.shp) format. The land use data were obtained by combining all existing land use data in shapefile format. Subsequently, the complete .shp file set was merged, and the land use data were clipped with the administrative boundary shapefile of the Batang Anai Subdistrict using clip feature tools. This process enabled the acquisition of the land use data for the Batang Anai Subdistrict.

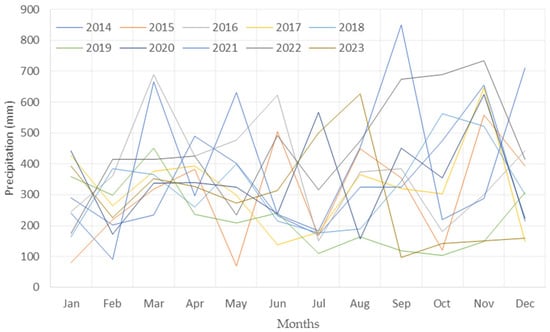

2.2.2. Monthly Rainfall Data (2014–2023)

The dataset used for this study spans a period of ten years, from 2014 to 2023, and includes monthly rainfall measurements. These data served as the foundation for the selection of images utilized in the analysis. The image period that was selected for the analysis sample was determined based on the month with the lowest average rainfall. The data were obtained from the West Sumatra Climatology Station of the Indonesian Meteorological, Climatological and Geophysical Agency (BMKG). The mean monthly precipitation for the specified interval was determined and is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Monthly average rainfall of Batang Anai Subdistrict for the years 2014–2023 (in mm), given original records of rainfall obtained from report of BMKG West Sumatera.

Monthly average rainfall data for the Batang Anai Subdistrict (2014–2023) were also used to compute precipitation anomalies relative to the long-term monthly mean. Anomalies were calculated as the percentage deviation of each month’s rainfall from the 10-year average, allowing for the identification of months and years experiencing below-normal rainfall, indicative of potential drought events. Table 1 below shows precipitation anomalies in the Batang Anai Subdistrict from 2014 to 2023.

Table 1.

Precipitation anomalies in Batang Anai Subdistrict from 2014 to 2023. The anomalies were calculated as the percentage deviation of each month’s rainfall from the 10-year average.

Monthly precipitation anomalies for the Batang Anai Subdistrict (2014–2023) were calculated as the percentage deviation from the long-term monthly mean. Negative anomalies indicate below-average rainfall, suggesting potential drought conditions, while positive anomalies reflect above-average precipitation. Several months in 2015, 2017, 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2023 exhibited pronounced negative anomalies (>50% below the mean), corroborating periods of reduced rainfall that may influence agricultural drought patterns. This analysis provides context for interpreting NDDI-derived drought indices within the study area.

2.2.3. Data Image MODIS MOD09A1 V6

The selection of the MODIS data image employed is predicated on the month with the lowest mean rainfall, as recorded by rainfall data collected between 2014 and 2023. The MODIS MOD09A1 V6 data image was obtained from www.earthdata.nasa.gov. The initial format of the MODIS data image is Hierarchical Data Format (HDF), allowing data to be grouped into groups and subgroups. Three distinct spectra were utilized in this study, including red (R), near-infrared (NIR), and shortwave infrared (SWIR), with wavelengths of 645 nanometers (nm), 875 nm, and 2130 nm, respectively [28]. These wavelengths are then grouped into specific bands. Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of the MODIS data image set, categorized according to band group [29].

Table 2.

Grouping of MOD09A1 image data; surface reflectance obtained from the MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) sensor on NASA’s Terra satellite. The system comprises seven channels, with a spatial resolution of 500 m and a temporal span of eight days. This study utilized Band 1, Band 2, and Band 7.

The wavelengths utilized in this study will fall within Band 1 (for wavelengths of 645 nm), Band 2 (for wavelengths of 875 nm), and Band 7 (for wavelengths of 2130 nm). Therefore, calculations were made in accordance with the NDVI and NDWI equations, which are demonstrated in Formulas (1) and (2) below:

The NDVI was analyzed using Band 1 (R) and 2 (NIR), while the NDWI was analyzed using Band 2 (NIR) and 7 (SWIR). Data image processing was executed in ArcMap Ver. 10.8. The initial step entailed the exportation of data from Band 1, 2, and 7 into the .img format. The next step was to perform the geometric correction of the images by aligning the projection system between the images and layers. The MODIS MOD09A1 images utilize a sinusoidal projection technique, resulting in an apparent skewing of the images when adjusted to global projection. The coordinate system in use is WGS 1984 UTM Zone 47S. Image projection adjustments are performed using the Project Raster feature. The final step in this process is to multiply the value of each band by a scale factor of 0.0001 using the Raster Calculator feature. All sources of analytical data used in this study are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary table of main data sources and their purposes of use in research.

2.3. Data Processing

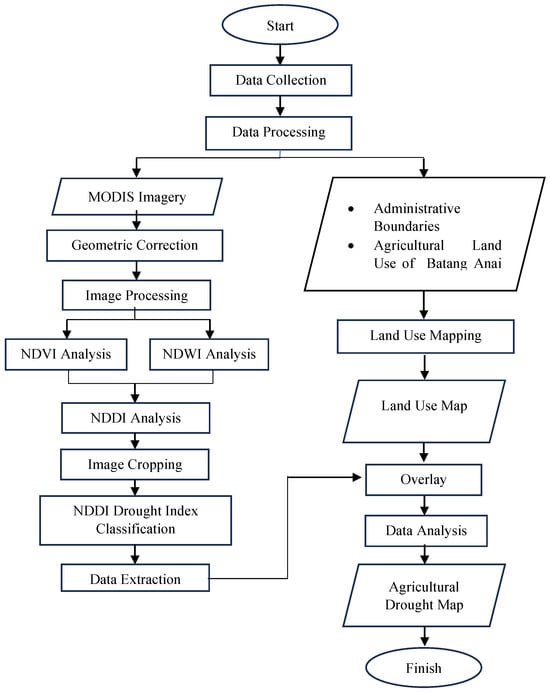

2.3.1. Workflow

The research process generally comprises three distinct stages: (1) The preparation of land use maps, which entails the overlaying of the regional boundary map with the land use map obtained from BIG. (2) The processing of image data derived from MODIS imagery. This entails performing geometric corrections, selecting image data that represents the conditions of the analysis area, and continuing with NDVI, NDWI, and NDDI analysis. The use of wavelengths of 875 nm and 645 nm in NDDI analysis represents the maximum limit, as chlorophyll readings below 645 nm cannot be taken due to the strong absorption of chlorophyll. Meanwhile, wavelengths of 875 nm and 2130 nm in NDWI capture vegetation liquid water changes and vegetation covered area, but are less sensitive to atmospheric scattering effects [30]. The calculation of NDWI and NDVI results in NDDI, which has a wider range of values than a simple NDVI-NDWI differentiation and can be used for the analysis of drought at local scales [31]. (3) The integration of NDDI values with the land use map will generate a spatial drought distribution for the Batang Anai Subdistrict. The purpose of study workflow is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

To obtain the NDDI value, it is necessary to first perform NDVI and NDWI analysis. The NDVI calculation utilizes NIR and R waves (Equation (1)), and the NDWI calculation employs NIR and SWIR waves (Equation (2)). The right side of the flowchart illustrates the generation of a base map, which is required to plot the drought level obtained from NDDI analysis in the study area.

2.3.2. MODIS Data Imagery

The selection of images was made on the basis of the month in which the lowest recorded rainfall was observed. This was accomplished in order to reduce the influence of clouds, improve visual quality, and optimize the interpretation of surface reflectance data, particularly in the analysis of vegetation and drought indices such as NDVI, NDWI, and NDDI [32]. In general, high cloud cover during the rainy season has been demonstrated to have an adverse effect on the acquisition of optical imagery. This is due to the fact that such imagery is highly dependent on clear atmospheric conditions [33,34,35]. Therefore, the selection of an optimal time for image acquisition is imperative to ensure that the data obtained are free from atmospheric interference and accurately reflect the actual surface conditions. The preliminary analysis of 10-year rainfall data presented in Table 1 indicates that July is the month with the lowest rainfall and corresponds to the period with the lowest vegetation moisture and the most stable atmospheric conditions, making it an appropriate month for NDDI-based drought assessment. Four MODIS data image sets are available in July; therefore, it is necessary to select one of these images for each year. Table 4 presents the available MODIS data image and the selection of images taken for the study.

Table 4.

Data image MODIS records and cloud percentage derived from MODIS. Cloud percentage was calculated by using StateQA in ArcMap. Image data are manually selected from the date with the lowest cloud percentage.

When calculating the cloud percentage from images, visual methods are avoided due to their subjectivity. Alternatively, the StateQA sub-datasets are applied in ArcMap Ver. 10.8, which contains pixel quality information in binary form (bit flags) to remove clouds, cloud shadows, and snow [36]. Information regarding cloud conditions is contained in bits 0 and 1 of StateQA [37]. The selection of analyzed pixels was restricted to the boundaries of the study area, ensuring that only MODIS pixels falling within the Batang Anai Subdistrict were included in the analysis. Cloud-affected pixels were identified using the StateQA layer from the MOD09A1 V6 product, which was processed in ArcMap Ver. 10.8. Pixels classified as cloudy were assigned a binary value of 0, while cloud-free pixels were assigned a value of 1. This binary mask was then summarized numerically to calculate the proportion of cloud contamination across each composite period. No additional thresholding criteria were applied beyond the inherent MODIS QA classifications. All spatial filtering, raster masking, and pixel extraction processes were conducted using the Extract by Mask, Raster Calculator, and Zonal Statistics tools in ArcMap Ver. 10.8. Consequently, the images selected for analysis were those with the lowest cloud cover to minimize potential data distortion.

After identifying the MODIS image, the following step involves the calculation of NDVI, as outlined in Formula (1). This calculation is performed in ArcMap Ver. 10.8 software using the Raster Calculator feature. The same steps are used to calculate the NDWI, using Equation (2). After the acquisition of the NDVI and NDWI values, the calculation of the NDDI can be performed using Formula (3) below:

The subsequent step involves the utilization of the Extract by Mask feature in ArcMap to obtain the image results of the analysis based on the research location. Following this, the image values are classified based on class using the Reclassify feature in ArcMap. The NDVI and NDWI classes are then classified according to their respective indices in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

Classification of NDVI by [38]. This figure is utilized as a reference for NDVI classification due to its derivation from Landsat 8 image measurements, which possesses a correlation value (R) of 0.84 with Quickbird images.

Table 6.

Classification of NDWI by [38]. This figure is utilized as a reference for NDWI classification due to its derivation from Landsat 8 image measurements, which possesses a correlation value (R) of 0.82 with Quickbird images.

Additionally, the classification of NDDI values will be referenced in Table 7.

Table 7.

Classification of NDDI by [28] These classifications are derived from U.S. Drought Monitor (USDM) maps. The USDM summarizes information from several drought indices and indicators.

Although the NDDI thresholds originally proposed by Gu et al. were developed for semi-arid ecosystems, they were adopted in this study as absolute spectral indicators of vegetation moisture stress rather than as eco-region–specific drought classifications. These thresholds are based on the physical behavior of SWIR and red reflectance under conditions of canopy desiccation, which is consistent across vegetation types regardless of climate zone. Because the purpose of this analysis was to identify the relative intensities of dry conditions within a humid tropical landscape, the NDDI thresholds serve as a standardized reference that allows for the consistent categorization of spectral drought severity over time. Furthermore, the use of externally established thresholds prevents introducing subjective or data-driven class boundaries that may vary by season or land cover, thereby maintaining methodological comparability with previous NDDI-based studies. The number of pixels is then converted into land area units using the Raster to Polygon feature in ArcMap. The final step in obtaining the area of drought distribution in the Batang Anai Subdistrict is to overlay the NDDI with the Batang Anai Subdistrict land use map. The resulting map will be displayed in Section 4.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of NDVI

The NDVI indicates the presence of vegetation cover [39]. NDVI transformation was employed in this study to analyze the relationship between vegetation conditions and the potential for drought in agricultural land in the Batang Anai Subdistrict. High NDVI values are indicative of areas with high levels of vegetation greenness, while low NDVI values are indicative of areas with low levels of vegetation greenness. This assumption is based on the concept that the NDVI is derived from the ratio between NIR and red light reflectance [40]. The presence of dense vegetation, characterized by an abundance of green leaves, has been observed to result in a greater reflection of NIR light and an increased absorption of R light. This phenomenon leads to an elevated NDVI value. The NDVI values for the Batang Anai Subdistrict are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Index range of NDVI of Batang Anai Subdistrict. NDVI calculation according to Equation (1) using the Raster Calculator feature in ArcMap Ver. 10.8. The average range of NDVI falls between 0.66 and 0.70, indicating that this value falls into the high vegetation classification.

The population standard deviation of 0.0366 and sample standard deviation of 0.0377 from NDVI datasets indicate a low degree of variability, which demonstrates the uniformity of the calculated values. The lowest average NDVI value recorded was 0.61 in dry fields in 2023. This is because agricultural cultivation in dry fields is less prevalent than in the other two areas, resulting in the smallest vegetation cover. Conversely, the plantation area with the highest NDVI value of 0.74 in 2019 indicates that this region has predominant agricultural cultivation. The NDVI value range falls into the high vegetation classification. More discussion can be found in Section 4.

3.2. Analysis of NDWI

The NDWI is calculated based on the ratio between SWIR and NIR reflectance. Prior to conducting the NDWI analysis, water bodies in the study area were not included in the analysis. The calculation is predicated on the assumption that the NDWI value is directly proportional to the water availability value. The moisture index values for the Batang Anai Subdistrict are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Index range of NDWI of Batang Anai Subdistrict. NDWI calculation according to Equation (2) using the Raster Calculator feature in ArcMap Ver. 10.8. The average range of NDWI falls between 0.52 and 0.57, indicating that this value falls into the high moisture classification.

The lowest NDWI value, recorded in the dry fields area in 2022, was 0.46, suggesting that the water availability in dry fields is quite low. This finding aligns with the results of the NDVI, which also indicate a decline in vegetation in areas with limited water availability. The NDWI value range is indicative of a high moisture content. More discussion can be found in Section 4.

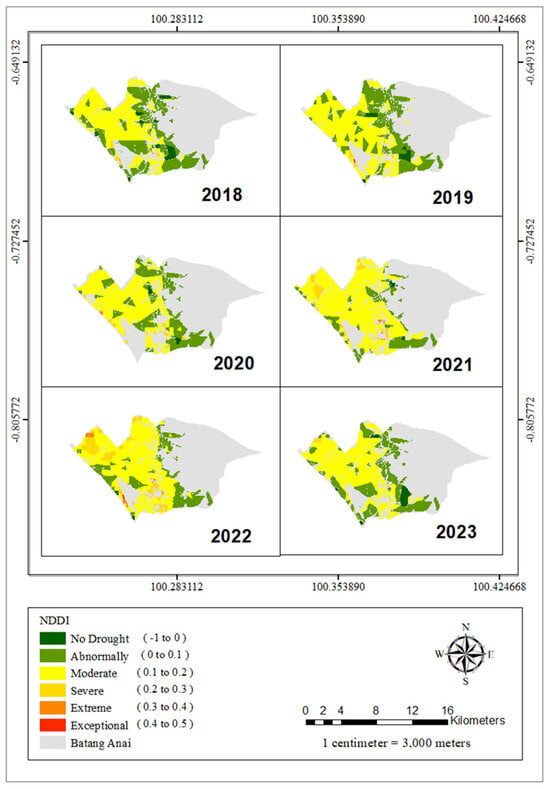

3.3. Analysis of NDDI

This study employed NDDI analysis to ascertain the extent of drought in agricultural land in the Batang Anai Subdistrict. The vegetation index and the moisture index are interrelated in the analysis of drought; therefore, this study posits that drought can occur when both the vegetation index and the moisture index decrease. An area is said to be experiencing drought if the vegetation index and moisture index values are significantly low, namely <0.5 for the vegetation index and <0.3 for the moisture index [28]. The drought index value for agricultural land in the Batang Anai Subdistrict is presented in Table 10, and the spatial distribution of NDDI is presented in Figure 4.

Table 10.

Index range of NDDI of Batang Anai Subdistrict. NDDI calculation according to Equation (3) using the Raster Calculator feature in ArcMap Ver. 10.8. The average range of NDDI falls between 0.09 and 0.14, indicating that this value falls into the low and moderate drought categories.

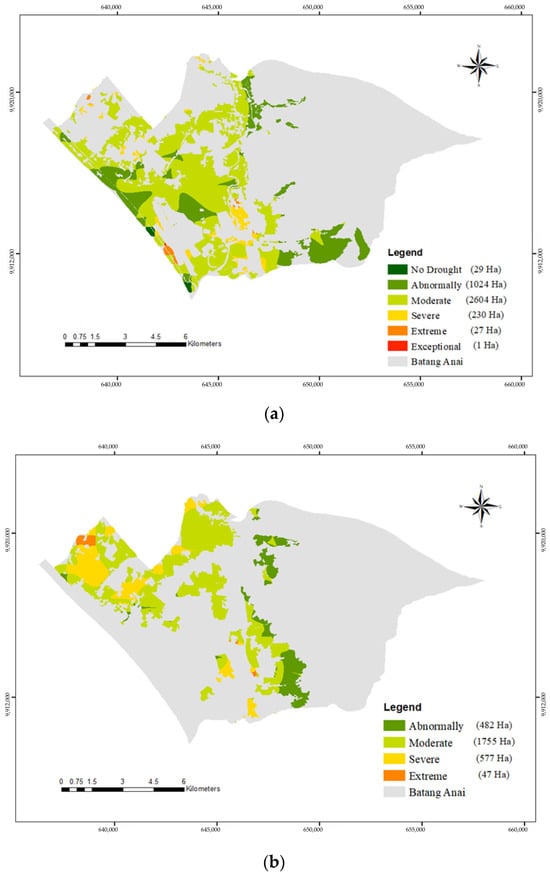

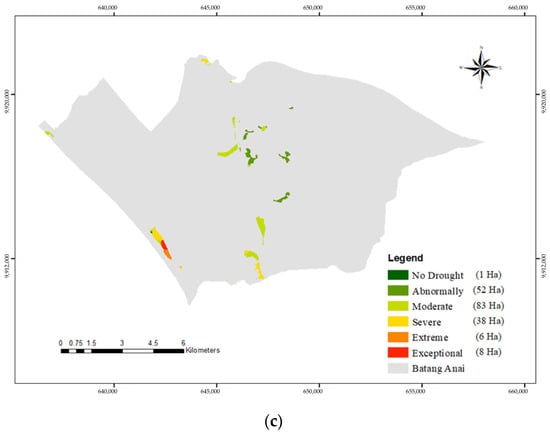

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution maps of NDDI over the Batang Anai Subdistrict, 2018–2023. The image was obtained by overlaying the overall NDDI values with a land use map specifically for agricultural areas, which was obtained during the map analysis process (see Figure 3). To obtain the NDDI value, it is necessary to first perform NDVI and NDWI analysis. The NDVI calculation utilizes NIR and R waves (Equation (1)), and the NDWI calculation employs NIR and SWIR waves (Equation (2)).

The NDDI value range in the Batang Anai Subdistrict is 0.08 to 0.16, with a general upward trend from 2018 to 2022, followed by a slight decrease in 2023. The observed NDDI range of 0.08–0.16 in the Batang Anai Subdistrict indicates generally moist to mildly dry surface conditions where vegetation is largely healthy, but some upland or non-irrigated fields show early signs of moisture stress [41]. In the context of rice fields, the NDDI value exhibited a range that was not significantly disparate from the resulting ranges from Du et al. [42], which were from −0.1 to 0.55, and from Salas et al. [23], which were 0 to 0.3. Because the NDDI values remain well below commonly reported severe drought ranges, there is no indication of a prolonged hydrological drought at the Subdistrict scale during the study period; rather, the landscape appears resilient to short dry spells but sensitive to longer rainfall deficits [43]. The drought classification produced for agricultural areas in the Batang Anai Subdistrict is classified as low and moderate. The interpretation of NDDI refers specifically to the classification scale adopted in this study and may not directly represent drought intensity under different tropical environmental conditions. More discussion can be found in Section 4.

3.4. Drought Distribution in Agricultural Areas in Batang Anai Subdistrict

The NDDI value provides an overview of the distribution of agricultural areas’ drought occurring in the Batang Anai Subdistrict. The mean NDDI value presented in Table 10 was derived from the NDDI figures for each pixel, which exhibited significant variability. This figure is employed to observe the distribution of drought in agricultural areas in the Batang Anai Subdistrict. The distribution of drought is illustrated in Table 11 below.

Table 11.

Drought distribution area of the agricultural areas in the Batang Anai Subdistrict. The index range of the NDDI value was reanalyzed spatially in ArcMap Ver. 10.8 (see Table 10) to produce the total area affected by drought and the level of drought experienced.

The Batang Anai Subdistrict exhibits a range of land drought levels, though these variations are minimal. In the agricultural areas of the Batang Anai Subdistrict, the two most prevalent drought levels are low and moderate, at 32.30% and 60.93%, respectively. The remaining drought levels, which encompass most of the remaining area, account for less than 5% of the total area.

The primary focus of this study is on the drought levels that require attention, specifically those designated as severe, extreme, and very extreme. The objective is to examine the specific agricultural areas that have been impacted by the ongoing drought. Consequently, the present study considers the year 2022 as the year of occurrence, during which the most extensive spread of drought occurred for the three drought levels that are the focus of this discussion, as illustrated in Table 11 above. The distribution map depicting the drought status of agricultural areas for the year 2022 is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Spatial drought level distributions of agricultural areas in 2022. The moderate drought level has the widest distribution of area for plantations at 2604 ha (a), rice fields at 1755 ha (b), and dry fields at 83 ha (c).

The extent of drought-affected agricultural areas in 2022 is presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

Drought distribution of agricultural areas in 2022 based on drought levels. Of these figures, the most notable are the moderate drought levels affecting 58.6% of plantation areas and severe and extreme drought levels affecting 68.3% and 58.1%, respectively.

The drought was most severe in the low-lying areas of the western district, in proximity to the coast. The low-lying areas in the Batang Anai Subdistrict are in the west, stretching along the coast at an elevation of 0–10 m above sea level. Meanwhile, to the east is a hilly area with an altitude ranging from 10 to 1000 m above sea level [44]. The east region is not experiencing an agricultural drought due to its natural forests and bushes.

4. Discussion

This study will first re-emphasize the use of a 1-month resolution (in July), a pixel size of image data at 500 pixels, the possibility of cloud cover, and pixel calculations, which will enable more accurate research to be conducted in the future. NDVI values that have variations in near-infrared wave reflection are attributable to differences in canopy shape and the planting distance of vegetation in each agricultural land use [45]. Changes in NDVI values, particularly in rice fields, are influenced by the pre-harvest and post-harvest periods, during which water bodies shift [46], and from the tillering to the heading period, causing NDVI readings to change [47]. This condition impacts the resulting NDVI value, thereby demonstrating a variability in index values among different vegetation types, as illustrated in Table 8.

The impact of plant vegetation on soil water retention is significant, particularly in the context of root systems where root water uptake can apparently increase the soil water retention capacity by providing an additional negative pressure and inducing micro-fissures and macropores in the rhizosphere soil [48]. Vegetation, such as woodlands and shrublands, plays a crucial role in water storage due to its ability to distribute roots within the soil surface layer. This distribution results in varied water retention values at depths ranging from 0 to 30 cm, highlighting the importance of considering root distribution in determining water retention dynamics [49]. Conversely, as shown in Table 9, the highest NDWI is observed in the plantation class, where ample water availability enables the cultivation of a more extensive array of vegetation and where this index is sensitive to vegetation liquid water change [30]. NDWI values are susceptible to manipulation by vegetation density, which exhibits a direct proportionality to water retention capacity. Since the NDWI is a measure of liquid water molecules in vegetation canopies that interact with the incoming solar radiation [30], it demonstrates that regions exhibiting substantial vegetation coverage demonstrate superior water binding capacity in comparison to those areas characterized by minimal vegetation cover [50].

The increase in the NDDI in Table 10 was influenced by a decrease in rainfall, which resulted in a decrease in the moisture level of agricultural areas. The rainfall in July 2019, with an NDDI range of 0.11, was the lowest recorded for that month, a phenomenon influenced by a weak El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and a positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD). This phenomenon exerts an indirect influence on the duration of the dry season and the susceptibility to drought [51]. According to the BMKG, the period from June to August of 2022 was characterized by a neutral ENSO and a negative IOD, where in this study it is given the NDDI range of 0.14. This phenomenon typically leads to an increase in precipitation [27]. Large-scale climate oscillations, such as the ENSO, alter tropical precipitation patterns, which in turn influence soil moisture reserves and set the stage for agricultural drought. Deficits in soil moisture reduce actual evapotranspiration, stress vegetation, and increase the NDDI, thereby linking climatic forcing, land-surface processes, and crop water stress. Remote-sensing studies confirm that the propagation from rainfall anomalies will contribute to soil moisture/evapotranspiration anomalies, in turn affecting vegetation stress. This mechanism is observable globally in tropical agricultural settings [41,52,53,54]. This finding suggests that the El Niño phenomenon is not the only factor that can influence the occurrence of drought, but drought is also influenced by a variety of factors, including rainfall distribution, climate, and topography, among others [55]. To provide a quantitative linkage between remotely sensed drought signals and observed precipitation, we computed Pearson correlation coefficients between the annual total precipitation (2018–2023) and the mean annual NDDI classified by land use as in Table 10. The Pearson correlation (r) was computed as the covariance of precipitation and NDDI divided by the product of their standard deviations. The analysis yielded r = 0.774 for plantations, r = 0.857 for rice fields, and r = 0.434 for dry fields. The relatively strong positive correlations for plantations and rice fields indicate a clear year-to-year covariation between annual precipitation totals and the NDDI signal in these land use classes, whereas dry fields show a weaker association. These results must be interpreted with caution: the record length is short (six annual observations), which limits statistical power and precludes robust attribution; NDDI integrates surface drying and vegetation response, which can lag or lead precipitation anomalies, and local factors (irrigation, crop phenology, and land management changes) may modulate the remotely sensed signal. Notably, because we adopted the NDDI thresholds from Gu et al. [28] as standardized references of drought intensity, the observed positive associations suggest that additional processes (such as irrigation timing or vegetation phenology) may influence the index behavior in our humid tropical context.

The total agricultural areas affected by drought, as presented in Table 12, cover moderate drought and low drought for 58.6% and 65.8% of plantation areas, respectively. Rice fields were also significantly impacted, particularly by moderate, severe, and extreme drought, covering 39.5%, 68.3%, and 58.1%, respectively. Several factors have been identified as contributing to the occurrence of droughts in plantations and rice fields, particularly in the context of environmental drivers. This includes low rainfall and El Niño conditions [56]. Furthermore, soil texture represents one such factor, as disparities in soil particle size, such as sandy soil and clay soil, give rise to discrepancies in the water-holding capacity of the soil. This, in turn, exerts a substantial influence on crop responses to drought [57]. Although irrigation is intended to compensate for insufficient rainfall in designated areas, the improper scheduling of irrigation, such as suboptimal irrigation [58], the interplay between irrigation practices and drought management strategies [59], and the combination of controlled flooding and intermittent irrigation [60] will affect soil biological properties, ultimately influencing crop productivity under drought conditions. Furthermore, the capacity of the land to absorb water is influenced by slope and topography factors. Steep slopes tend to experience runoff and exacerbate drought conditions, while flat land, though capable of draining water, is susceptible to flooding if not managed effectively by drainage systems [61]. To conclude, this study demonstrates that the NDDI, derived from MODIS surface reflectance, provides a practical and cost-efficient approach for monitoring short-term vegetation moisture stress in humid tropical landscapes such as Batang Anai. The method has the potential to be applied to other regions, particularly those where cloud-free optical data remain sufficiently available to retrieve consistent temporal signals. However, its applicability may be constrained in areas with persistent cloud cover, strong seasonal land surface heterogeneity, or intensive irrigation management, where NDDI alone may not fully capture drought processes. Moreover, the use of fixed thresholds adapted from Gu et al. [28] requires careful consideration when transferring the method to regions with different background vegetation phenology, soil moisture regimes, or disturbance dynamics.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that drought stress can emerge in humid tropical regions despite high annual rainfall, as revealed through the application of the Normalized Difference Drought Index (NDDI). The utilization of the NDDI can explain the correlation between vegetation cover and surface moisture dynamics with drought conditions experienced by agricultural areas. The utilization of satellite imagery, such as Sentinel-2, which boasts a resolution ranging from 10 to 60 m, allows for seamless integration with other remote data sources, thereby ensuring more robust analytical outcomes [62]. The integration of multi-year MODIS imagery, rainfall records, and land use data provided a consistent framework for identifying spatial–temporal drought variability in agricultural systems of the Batang Anai Subdistrict. The analysis revealed that most agricultural land experienced a low to moderate drought intensity, with plantations and rice fields being the most affected land use types. Although similar approaches have been applied in non-tropical regions, this analysis examined NDDI dynamics across multiple land use categories within a tropical humid environment, where vegetation phenology, soil moisture behavior, and drought formation processes differ substantially from arid or temperate settings. The integration of multi-year NDDI trends (2018–2023) with land use stratification reveals a land use-specific drought sensitivity, as evidenced by the distinct Pearson correlation patterns (plantation: 0.774; rice fields: 0.857; dry fields: 0.434). These findings highlight that drought manifestation in tropical humid landscapes is not uniform but strongly moderated by land management practices.

Beyond mapping drought occurrence, this study underscores the scientific potential of NDDI as a diagnostic and early warning tool for characterizing vegetation–water interactions and their implications for agricultural resilience. The combined use of NDVI, NDWI, and NDDI establishes a scalable approach for tracking ecosystem responses to moisture deficits across multiple spatial and temporal scales. Furthermore, the result of this study supports local authorities in prioritizing vulnerable agricultural zones for intervention and enables farmers to adopt adaptive practices, such as adjusting planting schedules or implementing water-saving measures. The findings offer evidence-based guidance for public policy formulation, including targeted drought relief programs, investment in irrigation and water management infrastructure, and the development of regional climate adaptation strategies for high-risk agricultural areas.

While this study provides valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations related to the MODIS imagery used—specifically its relatively coarse spatial resolution (500 m), the reliance on a single month of observations, and potential cloud interference. Future studies could address these constraints by incorporating higher-resolution or multi-temporal datasets to enhance accuracy and robustness. Another future challenge should focus on linking NDDI-derived drought indices with crop productivity metrics and soil moisture observations to better quantify the agronomic impact of drought intensity and duration. Incorporating higher-resolution satellite data, ground validation, and machine learning integration would enhance predictive capability and support adaptive water management strategies for tropical agricultural systems facing increasing climatic variability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.I.; methodology, F.I.; software, A.E.P.; validation, A.E.P., F.I., and N.S.; formal analysis, A.E.P.; data curation, A.E.P.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S.; writing—review and editing, N.S. and V.F.; visualization, A.E.P.; supervision, V.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in (Geospatial Information Agency (BIG) (www.tanahair.indonesia.go.id, accessed on 8 January 2025)) (NASA Earth data (https://earthdata.nasa.gov, accessed on 8 January 2025)). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from (Indonesian Meteorological, Climatological and Geophysical Agency (BMKG) West Sumatra Climatology Station) and are available at (https://www.bmkg.go.id/cuaca/prakiraan-cuaca/13, accessed on 8 January 2025) with the permission of (Indonesian Meteorological, Climatological and Geophysical Agency (BMKG) West Sumatra Cli-matology Station).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used (Scite.ai) for the purposes of (generating text and finding studies). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BNPB | National Disaster Management Agency |

| BMKG | Meteorological, Climatological and Geophysical Agency of West Sumatera |

| BIG | Geospatial Information Agency |

| IOD | Indian Ocean Dipole Mode |

| IRBI | Indonesian Disaster Risk Index |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Wet Index |

| NDDI | Normalized Difference Drought Index |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| R | Red |

| SWIR | Shortwave Infrared |

| TVI | Thermal Vegetation Index |

References

- Hendrawan, V.S.A.; Kim, W.; Touge, Y.; Shi, K.; Komori, D. A Global-Scale Relationship Between Crop Yield Anomaly and Multiscalar Drought Index Based on Multiple Precipitation Data. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 014037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lian, X.; Slette, I.J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, A.; Piao, S. Rising Ecosystem Water Demand Exacerbates the Lengthening of Tropical Dry Seasons. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalakrishna, K.N.; Hugar, R.; Rajashekar, M.K.; Jayant, S.B.; Talekar, S.C.; Virupaxi, P.C. Simulated Drought Stress Unravels Differential Response and Different Mechanisms of Drought Tolerance in Newly Developed Tropical Field Corn Inbreds. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orek, C. A Review of Drought-Stress Responsive Genes and Their Applications for Drought Stress Tolerance in Cassava (Manihot Esculenta Crantz). Discov. Biotechnol. 2024, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, A.G.; Giardina, C.P.; Giambelluca, T.W.; Brewington, L.; Chen, Y.L.; Chu, P.S.; Fortini, L.B.; Hall, D.; Helweg, D.A.; Keener, V.W.; et al. A Century of Drought in Hawaiʻi: Geospatial Analysis and Synthesis Across Hydrological, Ecological, and Socioeconomic Scales. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruedas, D.P.R.A.; Moggiano, N. ENSO Influence on Agricultural Drought Identified by SPEI Assessment in the Peruvian Tropical Andes, Mantaro Valley. Manglar 2023, 20, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.R.; Alarmelu, S.; Vasantha, S.; Sheelamary, S.; Anusheela, V.; Kumar, R.; Chhabra, M.L.; Mutharasu, S.; Karthick, M. Drought Resilience Evaluation of Sugarcane (Saccharum Spp.) Hybrids in Indian Tropical and Sub-Tropical Climates. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2024, 84, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, E.S.; Lacerda, C.F.d.; Mesquita, R.O.; Melo, A.S.d.; Ferreira, J.; Teixeira, A.d.S.; Lima, S.C.R.V.; Sales, J.R.d.S.; Silva, J.d.S.; Gheyi, H.R. Supplemental Irrigation With Brackish Water Improves Carbon Assimilation and Water Use Efficiency in Maize Under Tropical Dryland Conditions. Agriculture 2022, 12, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawan, A.; Komori, D.; Hendrawan, V.S.A. Correlation Analysis of Agricultural Drought Risk on Wet Farming Crop and Meteorological Drought Index in the Tropical-Humid Region. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2023, 153, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affandy, N.A.; Iranata, D.; Anwar, N.; Maulana, M.A.; Wardoyo, W.; Prastyo, D.D.; Sukojo, B.M. The Relationship Between Hydro-Agricultural Drought in the Corong River Basin: A Causal Time Series Regression Model. Civ. Eng. Dimens. 2024, 26, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tete, J.N.; Makokha, G.O.; Ngesa, O.; Muthami, J.N.; Odhiambo, B.W. Spatio-Temporal Agricultural Drought Quantification in a Rainfed Agriculture, Athi-Galana-Sabaki River Basin. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2024, 16, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, A.; Setiadi, H. Distribution of Drought on Agricultural Land in Palabuhanratu District Sukabumi Regency. J. Geogr. Media Inf. Pengemb. Dan Profesi Kegeografian 2023, 20, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, L.V.; Thủy, T.T.T. Drought Sensitivity Analysis of Meteorological and Vegetation Indices in Dak Nong, Vietnam. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 4968–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, F.; Yang, J.; Wu, T.; Wang, S.; Zhao, X.; Tariq, A. Impact Assessment of Agricultural Droughts on Water Use Efficiency in Different Climatic Regions of Punjab Province Pakistan Using MODIS Time Series Imagery. Hydrol. Process. 2024, 38, e15232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahhane, Y.; Ongoma, V.; Hadri, A.; Kharrou, M.H.; Hakam, O.; Chehbouni, A. Probabilistic Linkages of Propagation from Meteorological to Agricultural Drought in the North African Semi-Arid Region. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1559046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizah, E.N.; Wijaya, A.P.; Sabri, L.M. Analisis Daerah Rawan Kekeringan Lahan Sawah di Kabupaten Purworejo Menggunakan Sistem Informasi Geografis. Elipsoida J. Geod. Dan Geomatika 2023, 6, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vicente, V.; Clark, J.R.; Corradi, P.; Aliani, S.; Arias, M.; Bochow, M.; Bonnery, G.; Cole, M.; Cózar, A.; Donnelly, R.; et al. Measuring Marine Plastic Debris from Space: Initial Assessment of Observation Requirements. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Ch, W.; García-Ortiz, J. A Long Short-Term Memory-Based Prototype Model for Drought Prediction. Electronics 2023, 12, 3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Henchiri, M.; Seka, A.M.; Nanzad, L. Drought Monitoring and Performance Evaluation Based on Machine Learning Fusion of Multi-Source Remote Sensing Drought Factors. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.H.; Duc, P.; Luong, T.H.; Duc, T.T.; Ngoc, T.T.; Minh, T.N.; Nguyễn, M.T. Application of Artificial Intelligence to Forecast Drought Index for the Mekong Delta. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L. Ensemble Learning Based on Remote Sensing Data for Monitoring Agricultural Drought in Major Winter Wheat-Producing Areas of China. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2023, 48, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzakiyah, I.F.; Saraswati, R.; Pamungkas, F.D. The Potential of Agricultural Land Drought Using Normalized Difference Drought Index in Ciampel Subdistrict Karawang Regency. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2022, 12, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Martínez, F.; Valdés-Rodríguez, O.A.; Palacios-Wassenaar, O.M.; Márquez-Grajales, A.; Hernández, L.D.R. Methodological Estimation to Quantify Drought Intensity Based on the NDDI Index With Landsat 8 Multispectral Images in the Central Zone of the Gulf of Mexico. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1027483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F.A.; Suryawati, S.; Supriyadi, S.; Basuki, B. Google Earth Engine for Spatio-Temporal Drought Monitoring in Bangkalan, Indonesia. Bio Web Conf. 2024, 99, 05006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujiyo, M.; Nurdianti, R.; Komariah, K.; Sutarno, S. Agricultural Land Dryness Distribution Using the Normalized Difference Drought Index (NDDI) Algorithm on Landsat 8 Imagery in Eromoko, Indonesia. Environ. Nat. Resour. J. 2023, 21, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariaman, B.P.S.K.P. (Ed.) Kecamatan Batang Anai Dalam Angka 2024; BPS Kabupaten Padang Pariaman: Kabupaten Padang Pariaman, Indonesia, 2024; pp. 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Syaiful; Darma, A.S.; Legianto; Budianto; Syahril; Agus, N.I.; Amiran, B. Buletin Iklim Sumatera Barat 05; Stasiun Klimatologi Padang Pariaman: Kabupaten Padang Pariaman, Indonesia, 2022; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Brown, J.F.; Verdin, J.P.; Wardlow, B. A five-year analysis of MODIS NDVI and NDWI for grassland drought assessment over the central Great Plains of the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, E.F.; Roger, J.C.; Ray, J.P. Modis Surface Reflactance User’s Guide Collection 6; Nasa Eosdis Land Processes Daac: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2015; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B.-C. NDWI—A normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-L.; Wu, J.-J. Crop Drought Monitoring using MODIS NDDI over Mid-Territory of China. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2008—2008 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 7–11 July 2008; pp. III-883–III-886. [Google Scholar]

- Dwi Kurnia, K. Analisis Potensi Kekeringan Lahan Sawah Dengan Menggunakan Metode Normalized Differency Drought Index (NDDI) dan Thermal Vegetation Index (TVI). Studi Kasus: Kabupaten Bantul, in Teknik Geodesi. Bachelor’s Thesis, Institut Teknologi Nasional Malang, Malang, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt, I.D.R.; Schultz, B.; Rizzi, R.; Sanches, I.D.A.; Formaggio, A.R.; Atzberger, C.; Mello, M.P.; Immitzer, M.; Trabaquini, K.; Foschiera, W.; et al. Cloud Cover Assessment for Operational Crop Monitoring Systems in Tropical Areas. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, J.W.; Bogdanoff, A.S.; Campbell, J.R.; Cummings, J.; Westphal, D.L.; Smith, N.J.; Zhang, J. Estimating Infrared Radiometric Satellite Sea Surface Temperature Retrieval Cold Biases in the Tropics Due to Unscreened Optically Thin Cirrus Clouds. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2017, 34, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikriyah, V.N. Mapping Land Cover Based on Time Series Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) Data in Klaten, Indonesia. J. Geogr. Lingkung. Trop. 2020, 3, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, M.; Wegmann, M.; Kübert-Flock, C. Quantifying the Response of German Forests to Drought Events via Satellite Imagery. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Lü, D.; Wang, C.; Lü, Y.; Wu, X. Spatiotemporal Patterns and Driving Factors of Ecological Vulnerability on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Based on the Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukojo, B.M.; Prayoga, M.P. Pemanfaatan Teknologi Penginderaan Jauh dan Sistem Informasi Geografis Untuk Analisis Spasial Tingkat Kekeringan Wilayah Kabupaten Tuban. Geoid J. Geod. Surv. GPS GIS Penginderaan Jauh Hidrogr. Pertanah. 2018, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasaiba, M.; Saud, A. Pemanfaatan Citra Landsat 8 Oli/Tirs Untuk Identifikasi Kerapatan Vegetasi Menggunakan Metode Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) Di Kota Ambon. J. Geogr. 2022, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Singgalen, Y.A. Penerapan Metode Spatio-Temporal Analysis dalam Analisis Dinamika Tutupan dan Penggunaan Lahan Berbasis NDVI dan NDWI. Kaji. Ilmian Inform. Dan Komput. 2023, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.P.; Jagtap, M.P.; Khatri, N.; Madan, H.; Vadduri, A.A.; Patodia, T. Exploration and advancement of NDDI leveraging NDVI and NDWI in Indian semi-arid regions: A remote sensing-based study. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.L.T.; Bui, D.D.; Nguyen, M.; Lee, H. Satellite-Based, Multi-Indices for Evaluation of Agricultural Droughts in a Highly Dynamic Tropical Catchment, Central Vietnam. Water 2018, 10, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, U.; Das, T.K. Enhancing agricultural drought monitoring with the Integrated Agricultural Drought Index (IADI): A multi-source remote sensing approach. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 75, 8599–8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariaman, P.P. Mengenal Padang Pariaman. 2025. Available online: https://padangpariamankab.go.id/blog/profil_tampil/wilayah (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Zou, X.; Mõttus, M. Sensitivity of Common Vegetation Indices to the Canopy Structure of Field Crops. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Tian, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wan, W.; Liu, K. Research on Rice Fields Extraction by NDVI Difference Method Based on Sentinel Data. Sensors 2023, 23, 5876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Liang, S.; Chen, Y.; Ma, H.; Li, W.; He, T.; Tian, F.; Zhang, F. A comprehensive review of rice mapping from satellite data: Algorithms, product characteristics and consistency assessment. Sci. Remote Sens. 2024, 10, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Li, P.; Fei, W.; Wang, J. Effects of vegetation roots on the structure and hydraulic properties of soils: A perspective review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, F.; Zhou, M.; Zhu, B.; Wang, H. Converting Cropland to Forest Improves Soil Water Retention Capacity by Changing Soil Aggregate Stability and Pore-Size Distribution. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, A.S.; Hadi, M.P.; Nurjani, E. Analisis spasial temporal zona rawan kekeringan lahan pertanian berbasis remote sensing. J. Teknosains 2022, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armei Saputra, M.P.R. Dampak El Niño dan IOD Positif Terhadap Lama Musim Kemarau dan Pertanian di Sumatera Barat; ANTARA SUMBAR: Sumatera Barat, Indonesia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-J.; Kim, N.; Lee, Y. Development of Integrated Crop Drought Index by Combining Rainfall, Land Surface Temperature, Evapotranspiration, Soil Moisture, and Vegetation Index for Agricultural Drought Monitoring. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagci, A.L.; Yilmaz, M.T. Mapping and Monitoring of Soil Moisture, Evapotranspiration, and Agricultural Drought. In Agro-geoinformatics: Theory and Practice; Di, L., Üstündağ, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, K.; Gessner, U.; Hochschild, V. Identifying Droughts Affecting Agriculture in Africa Based on Remote Sensing Time Series between 2000–2016: Rainfall Anomalies and Vegetation Condition in the Context of ENSO. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulana, I.F.; Sudaryatno, S.; Jatmiko, R.H. Identifikasi Sebaran Kerentanan Kekeringan Menggunakan Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) di Kabupaten Temanggung. J. Teknosains 2021, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memenun; Wati, T. Analisis Karakteristik Kakeringan Lahan Padi Sawah Di Wilayah Utara Provinsi Jawa Barat. J. Tanah Dan Iklim 2019, 43, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Harefa, D. The Influence of Soil Texture Types on Land Resilience to Drought in South Nias. J. Sapta Agrica 2025, 4, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamaria, S.; Arhonditsis, G.B. A Framework for Evaluating Irrigation Impact on Water Balance and Crop Yield Under Different Soil Moisture Conditions. Hydrol. Process. 2025, 39, e70232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F.; Arshad, A.; Mirchi, A.; Khaliq, T.; Zeng, X.; Rahman, M.M.; Dilawar, A.; Pham, Q.B.; Mahmood, K. Observed Changes in Crop Yield Associated With Droughts Propagation via Natural and Human-Disturbed Agro-Ecological Zones of Pakistan. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Wang, J.J.; Kongchum, M.; Harrell, D.L.; Adotey, N.; Haider, M.A.; Gaston, L.A.; Jeong, C. Soil Enzyme Activities and Health Indicator Characteristics in Furrow-irrigated and Flooded Rice Production Systems. Agrosystems Geosci. Environ. 2025, 8, e70094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewry, J.J.; Carrick, S.; Penny, V.; Dando, J.; Koele, N. Effect of Irrigation on Soil Physical Properties on Temperate Pastoral Farms: A Regional New Zealand Study. Soil Res. 2022, 60, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, D.; Simwanda, M.; Salekin, S.; Nyirenda, V.R.; Murayama, Y.; Ranagalage, M. Sentinel-2 Data for Land Cover/Use Mapping: A Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).