Abstract

Agricultural intensification is increasingly putting pressure on biodiversity, aquatic environments, and the climate, with impacts varying by landscape vulnerability. Integrated approaches that account for spatial variation and optimize multifunctionality are essential for sustainable land management under competing demands. This study applied high-resolution farm and geographical data within a simple, easily replicable geospatial method to assess single and multiple benefits across selected indicators, Environment, Climate, Nature, Economy, and Policy, when implementing a land-use change, exemplified by a theoretical beef system at the landscape scale, where the required land area was estimated to meet a predefined production goal. Agricultural fields were selected in an accumulative, stepwise manner, beginning with those most suitable according to the five indicators, until the target land area was reached. Prioritizing the most suitable fields revealed synergies between Climate and Nature indicators, as well as between Nature and fields with low economic value. While targeting multiple benefits (three or more indicators) reduced the total area selected and associated national-scale gains, it increased per-hectare benefits and maintained significant local advantages. This study demonstrates that integrating multiple indicators into land-use prioritization can enhance per-hectare benefits and maintain substantial local advantages, even when national-scale gains decline. The proposed method provides a practical, transparent tool for identifying multifunctional land-use opportunities and initiating dialogue with stakeholders, supporting more sustainable and context-sensitive land management under competing demands.

1. Introduction

Agricultural intensification over recent decades has substantially increased pressures on multiple environmental indicators, including biodiversity loss, degradation of natural habitats, nitrogen (N) pollution of aquatic ecosystems, and rising greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1,2]. These impacts occur at varying spatial scales and intensities, depending on the vulnerability and context of the surrounding landscape. At the same time, human-induced climate change has been linked to both local and global phenomena, such as extreme weather events and species extinctions [3], further amplifying the urgency for sustainable land-use strategies. Current policy and research efforts often encourage farmers to adopt targeted measures, such as reducing nitrogen leaching or mitigating GHG emissions, through land-use changes [4,5]. However, these single-focus approaches risk overlooking opportunities for co-benefits across multiple indicators, which is particularly critical in regions where land availability is constrained by competing demands from agriculture, conservation, and societal needs [6]. Addressing this challenge requires integrated approaches that optimize multifunctionality, ensuring that land-use changes deliver environmental, climatic, and biodiversity benefits while maintaining economic viability and policy compliance.

1.1. Need for Multifunctionality

Maximizing multiple benefits from a single piece of land is especially critical in agriculturally dominated countries, where land availability is often a limiting factor [7]. In Denmark, for instance, several policy targets are currently high on the political agenda [8]. These include achieving good ecological status in surface and coastal waters by reducing nitrogen loads to the coast by 45,000 tons per year; retiring carbon-rich soils from agricultural use to mitigate climate change; and reversing biodiversity loss by designating large, untouched natural areas. These goals are expected to be met without substantially compromising agricultural production [8,9], prompting the need for land to deliver in terms of various services.

1.2. Multiple Benefits

The capacity to deliver multiple or even singular benefits across environmental, climatic, biodiversity, and socio-economic indicators through sustainable agricultural practices is strongly influenced by landscape-scale spatial variability. This principle, long recognized in ecological research, is now gaining prominence in policy frameworks that emphasize multifunctionality [10]. Denmark offers a clear example: the country is transitioning from intensive agriculture toward more sustainable systems, with policy goals requiring that approximately 10% of farmland be retired from production while remaining areas adopt less intensive practices. Selecting the most suitable areas for such changes is critical, as benefits regarding nitrogen reduction, biodiversity enhancement, and climate mitigation vary substantially across landscapes [11]. For instance, nitrogen (N) loads to coastal waters, driven by fertilizer inputs, depend on local soil and hydrological conditions, particularly the degree of denitrification occurring between agricultural land and coastal ecosystems [1,12]. This denitrification process (NO3− → N2), previously referred to as N retention, reflects the ability of subsurface environments to transform nitrate into nitrogen gas through microbial activity, thereby reducing nutrient transport from source (agricultural fields) to recipient ecosystems (coastal waters) [13].

Introducing less N-demanding crops, such as grass, into areas currently dominated by, e.g., cereal crops, particularly in regions with low N retention, could reduce nitrogen loads to coastal waters. If these areas also contain soils with high carbon content, the conversion may simultaneously benefit the climate, as less greenhouse gas (GHG) is emitted from soils that are managed less intensively [14]. Additionally, crop choice directly influences carbon sequestration, with grasslands generally storing more carbon than cereal fields [15]. Biodiversity may also benefit most from nature-friendly land-use changes in landscapes already characterized by high biodiversity, compared to those with lower baseline biodiversity [16,17,18,19]. Spatial suitability for specific land-use changes can further depend on political priorities, such as those promoted through the greening of the EU Common Agricultural Policy [20]. Recent policy developments under the CAP and the European Green Deal have supported sustainable agricultural measures that are particularly well-suited to field margins and irregularly shaped plots [21]. In practice, this creates increased opportunities for farmers to apply for subsidies aimed at enhancing environmental quality, biodiversity, and climate resilience—especially in areas that are less productive or more difficult to manage due to field irregularity [21].

Therefore, there is a growing need to identify areas that optimize multiple indicators following specific land-use changes, rather than focusing solely on the benefits of a given production system [22,23] or the spatial distribution of individual indicators [24,25].

1.3. Importance of Stakeholder Engagement and Decision-Support Tools

While spatial models and biophysical indicators provide crucial insights for optimizing land-use changes, their effectiveness ultimately depends on active participation from stakeholders, farmers, landowners, and local communities who make decisions locally. Engaging these groups early in the process fosters trust, enhances legitimacy, and ensures that proposed measures match practical constraints and local priorities [26,27]. Participatory methods also promote transparency around data and assumptions, minimize perceptions of top–down control, and create opportunities for co-designing solutions that balance environmental goals with socio-economic needs [28]. Without such engagement, even scientifically sound models face limited adoption, hindering their ability to deliver multifunctional benefits at scale [29].

Decision-support tools that use multifunctional land-use assessment and GIS technologies can play a key role in this process. GIS-based models allow stakeholders to see spatial differences in indicators like nitrogen leaching, carbon storage potential, biodiversity richness, and economic value, making complex trade-offs easier to understand and discuss. These tools can integrate multiple datasets into clear maps and scenario analyses, enabling collaborative exploration of “what-if” situations and supporting informed decisions to improve multifunctionality. However, it is essential to avoid overwhelming stakeholders with overly complex or data-heavy tools before they are fully refined and user-friendly. Tools should be introduced gradually, ensuring they are accessible, easy to interpret, and aligned with stakeholders’ decision-making abilities. When combined with participatory workshops or interactive platforms, well-designed, simple GIS-based assessments can bridge the gap between scientific analysis and local knowledge, empowering stakeholders to identify solutions that are both environmentally effective and socially acceptable [26,27].

1.4. GIS-Based Decision Models for Multifunctionality Assessment

Both complex and simple GIS-based decision models have been used to identify the most suitable areas for implementing specific land-use changes, based on geographically varying indicators [25,28]. These models include Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) [28], weighted overlay techniques [25], and straightforward overlay approaches [29,30,31]. In Italy, a spatial weighted overlay method was applied [25], incorporating 11 spatial indicators to support local communities and stakeholder engagement. This approach provided a visual tool to demonstrate how different land-use decisions could produce localized benefits. The resulting map-based understanding of spatial value served as a foundation for further land management decisions [27]. However, complex tools can encounter difficulties after deployment due to high data demands, technical complexity, and insufficient manpower to maintain and update datasets [32,33]. Conversely, simpler GIS methods, such as targeted overlay and stepwise selection, offer a transparent, computationally efficient, and easily replicable alternative. These methods can lower barriers to stakeholder engagement by providing intuitive outputs and reducing reliance on specialized expertise, making them especially suitable for early-stage planning or situations with limited resources and technical capacity [26]. Furthermore, simplicity improves adaptability, allowing models to be scaled or adjusted as new data becomes available without sacrificing usability or stakeholder trust.

In Denmark, weighted overlays were used to develop scenarios for identifying optimal locations to introduce mini wetlands [30]. Other studies adopted simpler methods without weighting, for instance, a targeted geospatial stepwise approach to identify fields best suited for conversion from cereal to grass, aiming to achieve multiple benefits, primarily a reduction in coastal nitrogen loads [29]. Additionally, in a further study, it was demonstrated that converting areas from intensive agriculture to set-aside land often coincides with regions of high existing nature value and low agricultural economic productivity [34]. This spatial co-occurrence presents an opportunity to enhance environmental and ecological outcomes in a cost-effective manner.

These types of models, whether using overlay techniques with or without weighting, can be valuable tools in stakeholder involvement processes [27]. However, their effectiveness in driving actual landscape change may depend less on technical sophistication and more on the degree to which stakeholders feel genuinely included in the decision-making process [35]. For instance, involving stakeholders in assigning indicator weights and ensuring transparency around the underlying data and assumptions can foster trust and legitimacy [36]. Without such engagement, even well-designed models risk being perceived as top–down or technocratic, potentially limiting their practical impact. This suggests that simpler decision-support models, equipped with intuitive visualization tools and user-friendly interfaces, may be more effective in facilitating stakeholder participation, particularly when they allow for a decoupling from scientific gatekeeping [26]. Yet, while simplicity can enhance accessibility, it may also oversimplify complex trade-offs or mask uncertainties inherent in spatial data and model assumptions [37]. Therefore, the challenge lies in striking a balance: developing models that are both scientifically robust and socially inclusive, without compromising the integrity of the analysis or the agency of the stakeholders involved [26,37].

1.5. Aim of Study

This study addresses the potential spatial variation in landscape suitability to a land-use change from cereal production to more sustainable production. Potential land-use change could involve taking land out of production, such as forestation, rewetting of agricultural areas, setting aside, or changes in farm management, such as introducing less nitrogen-demanding crops or mixed systems. Replacing cereal with set aside, forest, or grass is expected to reduce management intensity and fertilizer inputs [38], enhance soil carbon sequestration [38] and increase biodiversity potential compared to cereal-based systems [39]. Additionally, grass can serve as a substitute for imported protein fodder, as protein can be extracted through biorefining and fed to monogastric animals [40,41]. And the fibre fraction from this process can be fed to livestock. It is hypothesized that the effectiveness of a new land use in delivering benefits across various indicators will depend on the measure used and the specific landscape context. Here, the land-use change is exemplified with a shift from conventional cereal cultivation to a theoretical beef system composed of grass–clover and wooded zones. The system represents an alternative sustainable system, inspired by the provenance project outcomes [42] and a general direction in societal policies. Hence, all effect calculations are based on this system. Similar calculations could be made for other land-use changes. More precisely, the system is expected to deliver on most indicators in landscapes characterized by high nitrogen loads from agricultural runoff to coastal areas, high biodiversity, elevated carbon levels, low economic land value, and where land-use policies have previously led to significant gains in production outcomes.

The narrow approach seen in current policy and research efforts is problematic in regions where land availability is constrained by competing demands from agriculture, conservation, and societal needs. There is a clear research gap in understanding how spatial variation in the landscape influences the effectiveness of integrated land-use changes that optimize multifunctionality and deliver environmental, climate, and biodiversity benefits while maintaining economic viability and policy compliance. Addressing this gap is critical for developing practical, stakeholder-friendly tools that support informed decision-making and integrated land management strategies. Therefore, this study aims to (i) assess spatial variation in landscape suitability for land-use change from cereal production to a theoretical beef system composed of grass–clover and wooded zones; (ii) evaluate potential co-benefits across five indicators, Environment, Climate, Nature, Economy and Policy, individually and in combination; (iii) develop a simple, transparent and user-friendly method for identifying multifunctional land-use opportunities; (iv) analyze trade-offs and synergies among indicators under different land-use scenarios to inform sustainable policy and management.

2. Materials and Methods

The analysis is based on a complete geographical dataset representing all agricultural fields from 2018 with linked values for the 5 selected indicators. From this combined dataset, where each entry corresponds to an agricultural field polygon, is it possible to choose stepwise the best fields to initiate the theoretical beef system for each indicator separately (single benefits, Section 2.4) and in combination (multiple benefits, Section 2.5). Benefits for a specific indicator occur when a field is selected based on a given indicator.

For further elaboration on the theoretical beef system, see Supplementary Material.

2.1. Study Area and Agricultural Data

The studied landscape represents the entire Danish area. Denmark, situated in northern Europe (55°43′ N 12°34′ E, area = 43,000 km2) (Figure 1a), has a population of 5,800,000, and the landscape is dominated by agriculture, which covers 62% of the area. Geography is characterized by sandy soils to the west and clay soils to the east, separated by a north-to-south ridge with a maximum elevation of 172 m.

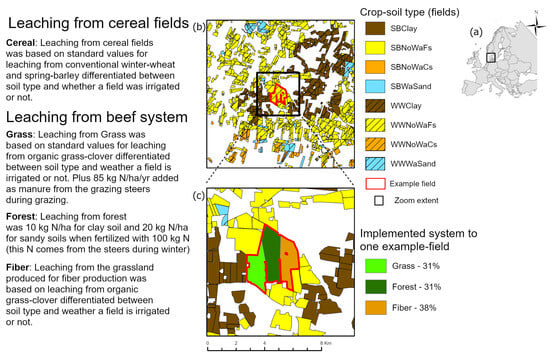

Figure 1.

Location of study site (a), illustration of the field-conversion process, and calculation of nitrogen leaching from the field before introduction of the system (b) and after (c). SB = spring barley, WW = winter wheat, NoWa = no irrigation, Wa = irrigation, Fs = fine sand, Cs = Coarse sand. % indicates the proportion of the field for each zone (grazing zone, energy-forest zone, and fibre zone).

In 2018, Denmark had 2,665,535 ha of total agricultural land [9], divided into 594,216 agricultural fields. By only including cereal fields of a minimum of 1.3 ha to sustain a minimum of two steers (calculated from fodder need and grass dry matter yields), the number of potential fields was 142,631 fields with a total of 1,078,783 ha. The system was only allowed on cereal fields (spring barley and winter wheat), since it has been suggested that this crop type be replaced with grass used for protein extraction, due to lower N leaching from the rootzone and higher biodiversity compared to cereals [15,29].

The Danish case stands out in Europe for its exceptional accessibility and high-quality agricultural and geospatial data. Unlike in some other European countries, where data availability is often fragmented, restricted, or aggregated at coarse spatial scales, Denmark offers highly granular, standardized datasets that are openly accessible for research. For example, the Danish Ministry of Agriculture Agency [9] provides detailed field-level information, including crop type and management practices, which is perhaps less available elsewhere in Europe. In addition, Denmark maintains comprehensive geospatial datasets derived from standardized modelling approaches that integrate satellite imagery with ground-based sampling [43,44]. This level of integration and transparency contrasts with practices in other European contexts, where agricultural data may be limited to differing regional statistics, and geospatial information may lack harmonization or sufficient resolution.

2.2. Selected Land-Use Change—Theoretical Beef System

The selected land-use change is a theoretical beef system previously developed in the research project “Provenance” [42]. It is composed of castrated bulls (steers) that should be outside year-round and with a herd size of two individuals as a minimum. The occupied area of the system is composed of three zones: (1) grazing zone, (2) energy-forest zone, (3) fibre zone (Figure 1b). In the summer period (growth season), the steers are kept in the grazing zone where their fodder is based solely on grazing. During the winter, the animals are kept in the energy forest, where they can seek shelter behind trees. The tree composition in this zone should be a combination of willow and poplar, which can be harvested from the system every tenth year for energy [45], and more permanent species such as oak, which has been described as beneficial in agroforest systems [46]. In this energy forest, the steers are fed with the fibre derived from the grass grown in the fibre zone during the growth season through the biorefinery process [47]. Calculated land use (ha) in the grazing and fibre zone is based on the fodder needed to support one steer annually [48] and weighted grass dry-matter yields per ha fertilized with 0 kg N [15] (see more on system calculations in Supplementary Material).

The defined goal is based on the current Danish beef consumption, which is 55,042 tons [49]. When accounting for meat from dairy cows, meat from heifers not used for replacement in milk production, and the sex ratio and death rate of male calves, the beef from male calves is reduced to 26,644 tons. Hence, if this amount is covered by meat from our steers, it should be possible to slaughter 98,681 steers (26,644 ton/0.270 tons) from the system each year. Since the steer is 2 years old at slaughter time, the number of steers in our system is doubled to 197,362, which, based on the system’s design (Supplementary Material), is equal to 128,285 ha in all.

2.3. Spatial-Varying Indicators Used in the Model

Suitable areas to initiate the conceptual system across the 142,631 fields—1,078,783 ha—were characterized by five spatially varying indicators (and a random selection for comparison) that would benefit from the system (Table 1). These were Environment, Climate, Nature, Economy, and Policy and were described as follows:

Environment—as nitrogen load to the coast: nitrogen (N) load to the coast was calculated as a proxy for the Environment indicator. N load to the coast per ha was calculated according to Odgaard et al. [29], by using N leaching values to the root zone from the area before implementing the system (Figure 1b) and after (Figure 1c), combined with N retention. N leaching from cereal is based on cereal type (spring barley or winter wheat), potential irrigation, and the soil type of the field [15,34]. Soil type was based on a raster dataset in a 30.4 × 30.4 m resolution, where each cell holds the soil type content as a percentage—e.g., sand, clay, silt, humus, etc. [43] (Figure 1b). N leaching after implementing the system was calculated for each zone (Figure 1c). The grazing zone is fertilized with manure from steers, which is naturally deposited. The amount of N in this zone is the difference between N in intake and N accumulated in the live weight gain, which gives 85 kg N per steer/yr. N leaching from the forest zone is based on pre-calculated values of 10 kg N/ha from clay soils and 20 kgN/ha from sandy soils [45] (Figure 1). Finally, N leaching from the fibre zone is based on standard values as calculated from [15] (Figure 1). Since the grass in this zone is always free of animals, N leaching values are reported for grass with zero fertilizer but with N fixation (50 kg N/ha) to include legumes.

N retention is the percentage reduction in NO3− to N2 in groundwater, surface waters, and soils from agricultural land to the coast. The N load was calculated for the agricultural area before and after introducing the system to be able to compare how much N was reduced by introducing the system and is explained based on N leaching and N retention as follows:

N load = N leaching × (N retention − 100)/100

Climate—as the carbon percentage in the soil: the risk of carbon emission was calculated using the carbon% in the soil. It was based on geographical soil data in a 30.4 × 30.4 m resolution, where each cell holds the carbon content as a percent [44]. As a proxy for carbon emissions, we used the carbon percentage directly, as fields with a high carbon content are more prone to emitting carbon during management than those with a low carbon content. The mean carbon percent was calculated for all agricultural fields.

Nature—as a combination of biodiversity and wilderness: as a proxy of nature richness, we used an overlay of the Danish biodiversity map [50] and wilderness map [51], both in a recalculated resolution of 100 × 100 m as from [34]. The biodiversity map is built up of three overall data types [50]: (1) spatial varying polygon data (forest parcels, fields, protected nature areas, water streams, cities, etc.), (2) species data (presence/absence in 10 × 10 km, point data of observations, habitat spots and areas), and (3) proxy data (spatial varying data which can be linked to species presence such as eutrophication, water dynamics, and cultivation). The wilderness map is built on spatially varying data describing human population density [51], distance from 13 human artefacts such as airports, harbours, etc., CORINE land cover data, and the ruggedness of the terrain calculated as the standard deviation of terrain curvature. In our analysis, we combined the biodiversity and wilderness maps. The value in the combined dataset serves as a proxy for the amount of nature in a cell, ranging from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates the most nature. The mean of this raster was calculated for all fields. When several fields have the same value, it is not possible to distinguish between them or select one over the other. In this case, the fields were ranked by field size, with large fields prioritized first.

Economy—as soil value as “Land rent”: land rent was calculated based on [34] and describes the soil value of a field by including the production cost and market price [52]. This is the value the farmer will receive if the field is rented out, including all costs such as labour, seed, etc. We targeted the system toward fields with a low land rent per ha to keep high-value fields in production.

Policy—as the calculated perimeter of a field divided by the field area, as “Field structural challenges—irregular fields”: as a proxy for the Policy indicator, we calculated the perimeter/area ratio of a field; high values reflect irregular fields that are more prone to being selected for an agricultural land-use change due to current land-use policies and subsidies.

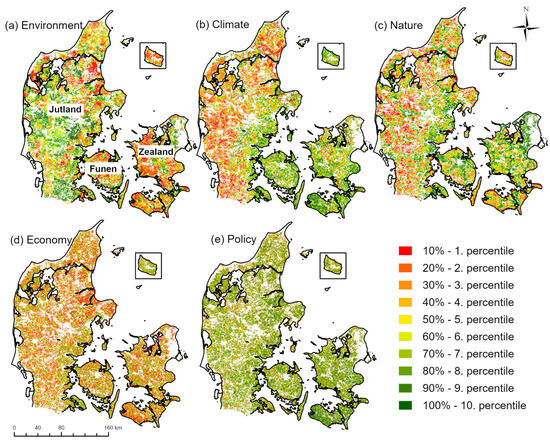

All agricultural fields were ranked according to each indicator from 1 to 142,631 (the number of cereal fields in the study); 1 indicates the most suitable field to introduce the system (Figure 2). In cases of equal indicator value, field size is used, choosing the largest field first.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of the five indicators included in the model for cereal fields larger than 1.3 ha (in total, 1,078,783 ha) in Denmark. The 1st percentile (red colours) illustrates fields located in an area that would benefit the most if the new theoretical beef system were introduced, and the 10th percentile (green colours) illustrates fields that would help the least for each indicator separately. Identification of each central part of Denmark (Jutland, Funen, and Zealand) is inserted in (a). Boxes show the Danish island Bornholm located in the Baltic Sea.

Table 1.

Spatial-varying indicators, abbreviations of the specific indicators, and explanations for relevant data and methods, including references and how fields were targeted within the dataset for the individual indicators (Environment, Climate, Nature, Economy, Policy) in italics. The geographical distribution of the indicators can be seen in Figure 2. See also the appendix for more details on the data behind each indicator.

Table 1.

Spatial-varying indicators, abbreviations of the specific indicators, and explanations for relevant data and methods, including references and how fields were targeted within the dataset for the individual indicators (Environment, Climate, Nature, Economy, Policy) in italics. The geographical distribution of the indicators can be seen in Figure 2. See also the appendix for more details on the data behind each indicator.

| Spatial-Varying Indicator | Abbreviation | Data and References |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | Envi | Nitrogen load to the coast based on N leaching from agricultural fields to the rootzone (field scale) [53] in combination with soil type [43] and how much N is retained from source to recipient (national covering polygons of approximately 1500 ha)—rootzone to coast in this case [13]. This has been calculated using Equation (1), targeting fields with a high N load per ha. |

| Climate | Clim | Risk of carbon emission. Carbon % in the soil based on a national soil raster in 33.4 × 33.4 m resolution, where the carbon content in percent of the topsoil horizon (0–20 cm) has been modelled [44]. The mean carbon % for each field is used as a proxy for climate, targeting fields with high carbon%. |

| Nature | Nat | Nature richness—proxy. A national raster biodiversity (10 × 10 m resolution, updated to 2018) [50] and a national wilderness map (100 × 100 m resolution) [51] are combined in 100 × 100 m resolution, and the mean in each field is calculated as a score, targeting fields with high nature. |

| Economy | Eco | Land rent. Soil value of each field based on production costs, including seeds, fertilizer, irrigation, chemicals, labour, and machines and other equipment, subtracted from crop market prices in DkK at the field scale [52], targeting fields with a low land rent. |

| Policy | Pol | Field structural challenges—irregular fields. Field polygons were used to calculate the perimeter of a field divided by field area (LBST 2018) using ArcGIS Pro, targeting large perimeter in relation to area—high values |

| Random | - | The sorting data was based on random numbers for each field, ranking from 1 to 142,631 |

2.4. A Model to Assess the Single Benefits for Environment, Climate, Nature, Economy, and Policy Indicators

The ranked values for all five indicators (Figure 2) were combined into a single master table with 142,631 rows, corresponding to the number of cereal fields in Denmark, and five columns corresponding to the five indicators.

A targeted method [34] was used to define the most suitable agricultural fields to explore the theoretical system based on the five spatially varying indicators separately. The analysis behind the method used was based on the overlay and spatial analyst toolset in ArcGIS Pro (ESRI ArcGIS Pro, version 3.4), followed by descriptive statistics to visualize the results.

The principle of the targeted method is to select areas (in this case, agricultural fields) in a landscape that are most suitable for a land-use change, based on one or several spatially varying indicators. Areas can be chosen until a specific goal is reached—for example, in relation to production, environmental goals, or the economy. In this study, for the single benefits, fields were selected in an accumulative, stepwise manner, starting with the most suitable field (delivering on one or more of the indicators), until the goal of producing 197,362 steers was reached (128,285 ha).

Areas selected as suitable for the system were thereafter characterized based on descriptors of agriculture, N load reduction to the coast, land rent, and nature, while meeting the standards for agricultural area, beef production, and carbon sequestration potential. This allowed for a comparison of the five target approaches based on the five indicators. Carbon sequestration potential (not to be confused with the indicator for climate) was based on the theory that grass stores an additional 0.6 ton C /ha/yr. in the soil compared to cereal [15] and the energy forest composed of willow stores 0.18 t C/ha/yr [54].

2.5. Comparison of Pairwise and Multiple Indicator Benefits

The results from the single-benefit analysis were further analyzed for spatial co-occurrence, where multiple benefits occur, that is, an overlay of five geographic maps—one for each indicator (Figure 2). Pairwise benefits were defined as coincidences where benefits occurred for two indicators simultaneously on one field. In contrast, multiple benefits were identified as coincidences when this occurred across three or more indicators. Hence, in the search for multifunctionality, the statistical interconnection between the indicators is not relevant.

3. Results

3.1. Single-Indicator Benefits of Introducing the New Beef-Cattle System

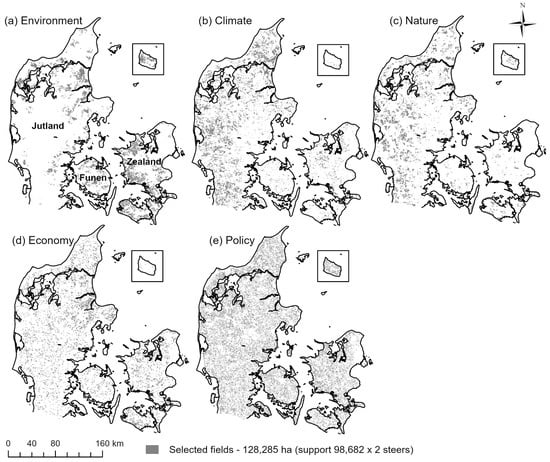

Focusing on single benefits, the spatial distribution of fields chosen to initiate the beef system shows a non-random spatial pattern for Environment, Climate, and Nature and a random relationship for Economy and Policy (Figure 3), corresponding to the spatial pattern of the indicators (Figure 2). Targeting fields for Environment (which causes less nitrogen load to the coast) results in selecting fields mostly from Eastern Jutland, along with areas in the north running from east to west, and the western part of Zealand. Additionally, targeting for Climate (reducing the risk of carbon emissions) or Nature (enhancing existing nature) mainly leads to selecting fields in western Denmark. Meanwhile, targeting for the Economy (low-value fields) and Policy (irregular fields, especially suitable for environmental farm subsidies) shows a more random distribution of selected fields, with a few hotspots.

Figure 3.

Geographic distribution of the cereal fields selected to convert to the theoretical beef system for the five indicators in Denmark. Fields with the highest single-benefit potential are selected first (1. percentile, 2. percentile, etc.), resulting in 128,285 ha across all indicators. Boxes show the Danish island Bornholm located in the Baltic Sea.

The total area selected to sustain 89,681 steers is 128,285 ha for all indicators (Table 2). The characteristics of number of steers, meat production, and carbon sequestration are all area-dependent and are therefore similar across all indicators (Table 2). The number of agricultural fields selected varies depending on the selection indicator, with a tendency for fewer, larger fields to be chosen with the Economy indicator and more, smaller fields with the Policy indicator (6105 and 46,134 fields, respectively; Table 2). The Policy indicator is also the most expensive selection method, losing approximately EUR 24.5 M in production (Table 2), indicating that quite a lot of the small fields targeted with this measure are grown with high-value crops. Note that the gross output of the theoretical beef system has not been accounted for here. Reduced N loads are highest when selecting for Environment, followed by Economy (3318 and 1761 tons, respectively, Table 2). In comparison, selecting for Climate, Nature, or Policy will reduce N loads as much as selecting fields at random (Table 2). Finally, the nature index value is highest using Nature as an indicator (1372, Table 2), whereas the remaining four indicators do not differ much for this characteristic. Hence, using the Policy indicator as a selection method seems to target fields characterized by being many, small, and high-income, whereas using Economy as a selection method results in a few large fields characterized by low income and reduced N load to the coast (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the area selected when targeting each of the spatial-varying indicators separately, which is the area chosen in grey in Figure 3. The characteristics calculated are as follows: number of agricultural fields, N load reduction to the coast (N load from cereal minus N load from the beef system), land rent (sum of the value of each field—that is, the Economy indicator from Table 1), and the nature value index (sum of the value of each field * 103, derived from the Nature indicator in Table 1). N load reduction min = 0.02 ton per field and max = 2.26 ton per field, land rent min = 3 ERU per field and max = 1174 EUR per field, nature index value min = 0.6 per field and max = 0.9 per field. The table shows N load reduction, carbon sequestration, nature, and land rent when 100% of the goal is reached.

3.2. Pairwise and Multiple Benefits of Introducing the Theoretical System

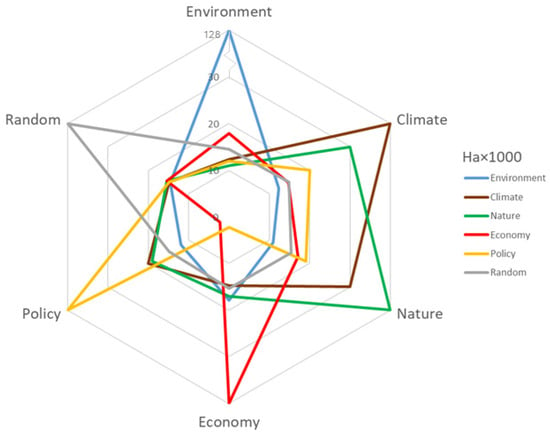

The overlay of the five ways to select the best-suited 128,285 ha to initiate the theoretical system illustrated in Figure 3 shows considerable variation in the areal spatial co-occurrence (Figure 4). For example, the area (128,285 ha) selected when targeting for the Environment indicator illustrates simultaneously benefit for Economy on ca. 18,000 ha and for Climate, Nature, and Policy from 11,000 ha to 12,000 ha—all different from selecting Random (Figure 4). The most significant spatial co-occurrence is the area chosen using either Climate or Nature as an indicator. Here, there is a strong, similar pattern that incorporates 30,000 ha of the agricultural landscape (Figure 4). Selecting for Climate or Nature also shows spatial co-occurrence with fields benefiting Policy (irregular fields). In contrast, benefits for Economy shows the least spatial co-occurrence with Policy and most spatial co-occurrence with Environment (Figure 4). Targeting Policy shows highest spatial co-occurrence with Climate and Nature and minimal spatial co-occurrence with fields with a low profit—Economy (Figure 4). Targeting fields randomly shows a spatial co-occurrence with approximately 15,000 ha for all indicators (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Results of the pairwise analysis illustrated by the spatial co-occurrence between one of each targeted indicator and the other four indicators separately (Environment = blue, Climate = brown, Nature = green, Economy = red, Policy = yellow). Note that the outer axis scale jumps from 30,000 to 128,000 ha for better visualization.

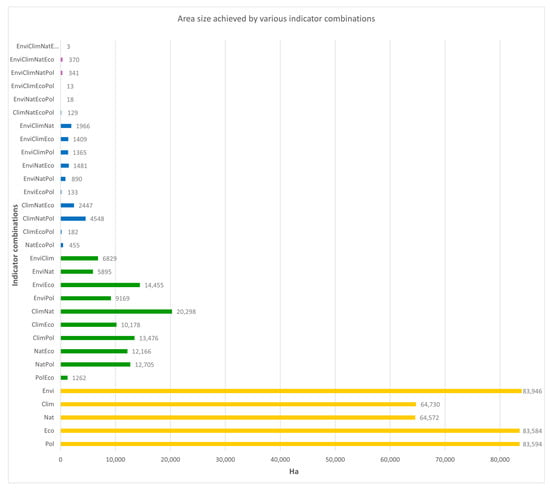

Thirty-one indicator combinations occur (Figure 5). The agricultural area decreases as the number of benefits increases (Figure 5, Table 3). This also results in fewer fields, reduced overall N load, lower costs, less affected nature, reduced agricultural area, fewer steers, and greater carbon sequestration, with more benefits (Table 3). Still, N load reduction, land rent, and nature increase per ha with an increasing number of indicators that show spatial co-occurrence (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Agricultural area (ha) where 2, 3, 4, or 5 indicators show spatial co-occurrence when selecting the best area to initiate the beef system, ranked according to the number of indicators that show spatial co-occurrence (red, purple, blue, and green) and agricultural area (ha) where the indicators show no spatial co-occurrence (yellow). Note that the sum of all indicator combinations in which one specific indicator is seen adds up to 128,285 ha.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the area selected when using one indicator and when 2, 3, 4, or 5 indicators show spatial co-occurrence. The characteristics calculated are as follows: number of agricultural fields, N load reduction to the coast (N load from cereal minus N load from the beef system), land rent (sum of the value of each field—that is, the Economy indicator (Table 1)), nature (sum of the value of each field—that is, the Nature indicator (Table 1)), agricultural area in ha, number of steers, total beef production, carbon sequestration under the assumption that grass stores additional 0.6 ton C /ha/yr in the soil compared to cereal [15], and the energy forest composed of willow stores 0.18 t C/ha/yr. [54]. Numbers in brackets represent the value per agricultural area.

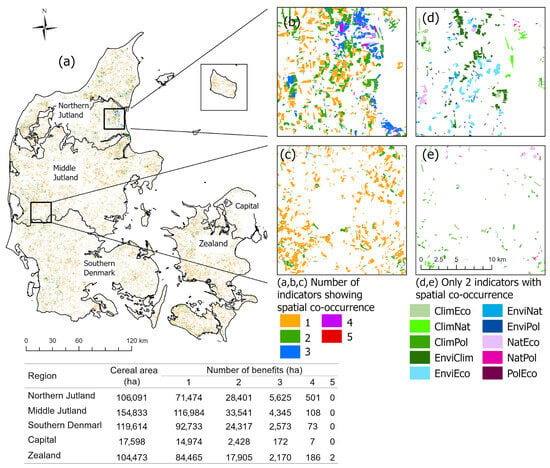

The spatial distribution of overlapping indicators shows a mosaic-like landscape in hotspots where more than one indicator is prioritized (Figure 6a,b,d), while other areas tend to deliver mainly on one indicator (Figure 6a,c). Furthermore, the number of benefits varies across small distances, resulting in landscapes composed of fields with 1–5 benefits over a relatively small extent (Figure 6b,d).

Figure 6.

The national geographical distribution of agricultural fields where 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 indicators show spatial co-occurrence when selecting the most suitable area to initiate the alternative beef system: (a) the national map, (b–e) zoomed-in examples. The table shows regional statistics. Boxes show the Danish island Bornholm located in the Baltic Sea.

4. Discussion

A geospatial method using overlay and spatial analysis in GIS has been applied to evaluate the environmental, climatic, natural, economic, and political impacts of a theoretical beef production system. The analysis demonstrates that targeted implementation yields net-positive outcomes across all five indicators, Environment, Climate, Nature, Economy, and Policy, at both local and national scales, outperforming random site selection.

4.1. Targeting for One Spatial-Varying Indicator

The areas selected to convert from cereal to the theoretical beef system highly depend on the spatial distribution of the spatial-varying drivers (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Furthermore, the reduction in N load from agricultural areas to the coast, the cost of conversion, and effects on nature vary depending on which of the five indicators are selected (Table 2). This is not surprising and shows an effect of the targeted selection method compared to a random selection. For example, targeting solely for Environment (decreasing coastal N load) reduces N load by 3000 t, whereas targeting for any of the other indicators will decrease coastal N loads by half only (Table 2). Targeting for Economy has the least economic impact, compared to targeting for Policy (small irregular fields), which is the most expensive (Table 2). The high gross output from irregular fields may keep the farmers from changing production type or taking land out of production. Hence, to facilitate a change towards sustainable change, there need to be other benefits to overcome the potential economic loss.

4.2. Targeting for Two or More Spatially Varying Indicators—Pairwise and Multiple Benefits

For the pairwise benefits, there is a general synergy between selected agricultural fields, which deliver highly on the Climate indicator (high carbon% in the soil) and the Nature indicator (Figure 4). Selecting for these two indicators also delivers on Policy by capturing irregular fields. Still, targeting the system towards areas with high potential for Nature tends to show spatial co-occurrence slightly more with areas that are also favourable for Economy, as they have low value. Hence, converting cereal fields, which have a high potential to deliver on the Nature indicator alone, could at the same time benefit both climate and policy and to some extent the economy. Selecting for Policy or Economy alone, both show spatial co-occurrence with areas that deliver on Environment, Climate, and Nature, but they do not deliver on each other (Figure 4). Hence, there is a trade-off between areas that benefit Policy and Economy. Still, delivering on both these indicators may eventually benefit the farmer by changing less valuable fields or the least convenient, remote, irregular field, with the latter being more likely to ease the transition towards a greener agriculture policy. Furthermore, the actual economic loss may be limited since extensive systems require less input [22].

The fact that (1) Nature is well represented when optimizing for low Economy (Figure 4) and (2) Nature is well represented when optimizing for Policy, which, again does not show spatial co-occurrence with Economy (Figure 5), indicates that nature located on soils of little value is captured in the case of (1), and nature located on high-productive, more expensive soils is captured in the case of (2). Hence, even though much of nature is captured by targeting either the Economy or Policy, the type of nature can vary. Targeting for low Economy might capture some of the rare nature areas in Denmark, such as nutrient-poor heaths and meadows, whereas targeting for Policy might capture carbon-rich, low-lying nature areas. Still, targeting Policy is by far the most expensive (Table 2). Hence, there could be a trade-off in whether one should take fields targeted by Policy and that are difficult to manage due to irregularity (Policy) and are nature-rich (Nature) but have high value (Economy), or the more regular fields that have rich nature (Nature) and are of low value when out of production. In either scenario, there is a benefit for the farmer, either economically or in terms of ease of management (Policy—irregular fields) and for nature.

When targeting more than two indicators (multiple benefits), the possible land area to initiate the system decreases substantially (Table 3) and, likewise, the potential benefits. For example, 244 tons of N are removed when three indicators are targeted. In contrast, only 20 tons are removed if four indicators are to be targeted. Despite this substantial lowering in potential area with multiple benefits, the effect per ha increases with a smaller area (Table 3). Therefore, initiating the system with consideration in areas where more than one indicator delivers could yield high local effects—despite the relatively small area available.

4.3. Spatial Distribution of the Pairwise and Multiple Benefits

The analysis of the benefits delivered by the indicators reveals that in addition to the overall trends described above, there are local variations in selected areas. Previous research has demonstrated spatial variation in what drives human land use, depending on local sociotechnical and geophysical drivers [55]. In this study, the spatial variation in distributions of the number of indicators that deliver in the landscape (Figure 6a–c) and how they pair up (Figure 6d,e) is illustrated. This is likely dependent on a combination of regional variation in, for example, land-use type [24,56] and in the indicators (Figure 2). When two or more indicators are targeted, some local areas display a mosaic-like pattern (Figure 6b). In contrast, locally, other areas tend to be solely dominated by only one spatial indicator (Figure 6c). Areas which tend to show a high density of different benefit combinations (Figure 6b,d) could reflect areas where there is already a high variation in land use present, and this pattern is therefore driven by local variation in land use. For example, such a pattern is shown in the northern area (Figure 6b,d), where the landscape is characterized by both agriculture and many different natural types, such as bogs, wetlands, meadow areas, and forests, and by relatively steep terrain near flatter terrain. This area has also been shown to display a multifunctional landscape that meets various indicators [24].

Furthermore, areas that are distinctive in terms of landscape type, either by being dominated by agriculture or, for example, relatively steep slopes, tend to deliver more similar services, such as agricultural services on flatter terrains and services, e.g., from forests on steep terrain [24]. In line with the latter, previous research has stated that, for example, forests tend to be situated on relatively steep slopes in Denmark, especially in areas with a high topographic heterogeneity [56]. This is also the case for the current study, where simpler landscapes, such as some of the agricultural Midwestern parts of Jutland, tend to be dominated by fields delivering on only one indicator (Figure 6c). These local variations in the number of indicators and how they pair up could support farmers and other stakeholders in knowledge sharing and decision-making. It would also be advisable to conduct further research to identify which areas could be worth further investigation, depending on the purpose.

4.4. Addressing the Research Aim, Strengths, and Limitations of the Study

This study aims to address a research gap in understanding how spatial variation in the landscape influences the effectiveness of integrated land-use changes that optimize multifunctionality and deliver environmental, climate, and biodiversity benefits while maintaining economic viability and policy compliance. To bridge this gap, our study applies high-resolution farm and geographical data within a simple, replicable geospatial framework to evaluate both single and multiple benefits of land-use change across five key indicators: Environment, Climate, Nature, Economy, and Policy. By prioritizing fields based on spatial suitability and integrating multiple indicators, we demonstrate how multifunctionality can be optimized at the landscape scale. This approach not only reveals synergies and trade-offs among indicators but also provides a practical, transparent tool that stakeholders can use to identify land-use opportunities, supporting informed decision-making and integrated land management strategies.

Our study is based on a geographical data overlay and the Spatial Analyst toolset in GIS, offering a methodologically more straightforward approach than more complex frameworks such as Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA). While MCDA models can provide nuanced evaluations, they are often less transparent, more time-consuming, and more challenging to communicate effectively to stakeholders [31,37]. In contrast, the simple overlay method employed in this research is easily accessible, computationally efficient, visually intuitive, and well-suited for stakeholder engagement processes. Real-time weighting of spatial indicators can be applied to simulate future scenarios and facilitate participatory decision-making [25]. It is important to note that the results presented are based on national, case-specific conditions. If the model is to be applied in an international context, it is essential to incorporate regionally appropriate data for specific indicators to ensure relevance and accuracy. Despite its strengths, the study has several limitations. First, the conceptual system is designed for implementation in individual fields. In practice, this assumption may be unrealistic, as farmers typically plan across their entire landholding, optimizing the distribution of the farm system’s three zones, grassland, forest, and agroforestry, at the whole-farm level. An alternative approach could involve collaboration among multiple farmers interested in transitioning their practices.

While the results are promising, these are not ready for direct implementation. The conceptual model remains theoretical, and practical application would require further research into farm-level decision-making, stakeholder engagement, and integration within broader agricultural systems. This challenge is widely recognized in the literature: complex decision-support tools often fail to achieve adoption when they are introduced before being sufficiently refined or adapted to user needs [26,37]. Studies on participatory modelling emphasize that usability and transparency are critical for legitimacy and stakeholder trust [27,36]. Overloading farmers and landowners with overly technical or data-heavy tools can create barriers rather than solutions, as seen in cases where sophisticated Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) frameworks were abandoned due to complexity [25]. In contrast, simpler, intuitive tools, such as targeted overlay approaches, are more likely to initiate dialogue and foster co-design processes [29]. Therefore, the tool presented here should be regarded as a first step in development, offering a transparent and accessible framework that can evolve through iterative improvements, participatory workshops, and scenario-based refinements. Future versions should incorporate dynamic weighting and interactive features to align with best practices in participatory decision-making while maintaining scientific robustness.

5. Conclusions

The results presented here highlight spatial variations in the multiple benefits, and their combinations, achieved through land-use change in existing cereal fields in Denmark. The geospatial analysis provides a valuable tool for identifying local trends and relationships among indicators. The same indicators and model framework could be applied to future studies with varying objectives, assessing the impacts of alternative scenarios at the field, farm, landscape, national, and international scales. This represents a promising avenue for further research. In Denmark, policy-led guidance currently promotes climate, nitrogen, and biodiversity measures, often targeting individual indicators. The method presented here could help optimize the spatial targeting of these measures, identify areas where they can deliver the most significant impact, and potentially address multiple indicators simultaneously. This is particularly relevant in regions where land availability is a limiting factor in achieving environmental and societal goals [6].

However, benefits may be amplified when neighbouring fields contribute complementary strengths across different indicators. As landscapes are increasingly studied for their capacity to deliver societal benefits alongside ecological protection, there is a growing need to assess the impacts of various agri-food systems at the landscape scale. Such evaluations can support both individual farmers and policymakers in making informed land-use decisions and may prove critical to the success or failure of landscape-level sustainability efforts.

Technical tools alone are not sufficient. Their success depends on active stakeholder engagement. Farmers, landowners, and local communities are central to implementing land-use changes, and involving them early fosters trust, legitimacy, and alignment with practical realities. Decision-support tools, such as GIS-based models, can make complex trade-offs more tangible by visualizing spatial variability in indicators such as nitrogen leaching, carbon storage potential, biodiversity richness, and economic value. Yet, these tools must remain accessible and user-friendly; overloading stakeholders with overly complex or data-heavy systems risks undermining adoption. The tool presented here should be regarded as a first step in development, offering a transparent and straightforward approach that can initiate dialogue and support participatory processes. Future iterations should build on this foundation to incorporate dynamic weighting, scenario testing, and interactive features that enhance usability and stakeholder ownership.

Finally, specific land-use changes and agricultural measures are highly relevant in the current and near-future policy context, as political demands intensify for greener, more climate-friendly farming that continues to deliver agricultural products. These pressures may catalyze a shift toward more integrated and collaborative systems, offering new opportunities for innovation and transformation in agricultural landscapes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14122426/s1, Figure S1: The alternative beef-cattle system and illustration of summer and winter application; Table S1: Fodder and land use to produce one steer with a slaughter weight of 270 kg.

Author Contributions

M.V.O.: conceptualization, methodology, data collection, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, project administration. T.K.: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization. T.D.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization. S.V.I.: formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was initiated during the Provenance project funded by the Danish Innovation Foundation, continued in the www.MIXED-project.eu (Grant agreement NO. 862357), funded by the Horizon Europe Framework Program, the CIRKULÆR project funded by the Danish Agricultural Agency Climate Action Program, the MIBICYCLE EU Joint Programming Initiative on Agriculture, Food Security and Climate Change (FACCE-JPI) project, and the LandCRAFT.dk Landscape Research in Sustainable Agricultural Future Pioneer Center and the Sustainscapes.org Center for Sustainable Landscapes under Global Change Novo Nordic Research Foundation Challenge program.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [MVO], upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to send our warmest thanks to Chris Kjeldsen, who contributed to the early phases of this paper, but passed away during the Provenance project which he initiated—we will always be grateful for his inspiration and spirit as a very special colleague.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hansen, B.; Aamand, J.; Blicher-Mathiesen, G.; Christiansen, A.V.; Claes, N.; Dalgaard, T.; Frederiksen, R.R.; Jacobsen, B.H.; Jakobsen, R.; Kallesøe, A. Assessing groundwater denitrification spatially is the key to targeted agricultural nitrogen regulation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgaard, T.; Olesen, J.E.; Petersen, S.O.; Petersen, B.M.; Jørgensen, U.; Kristensen, T.; Hutchings, N.J.; Gyldenkærne, S.; Hermansen, J.E. Developments in greenhouse gas emissions and net energy use in Danish agriculture–How to achieve substantial CO2 reductions? Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 3193–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barret, K. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. In IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, M.T.; Hermansen, J.E.; Cederberg, C.; Herzog, F.; Vale, J.; Jeanneret, P.; Sarthou, J.-P.; Friedel, J.K.; Balázs, K.; Fjellstad, W. Characterization factors for land use impacts on biodiversity in life cycle assessment based on direct measures of plant species richness in European farmland in the ‘Temperate Broadleaf and Mixed Forest’ biome. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 580, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graversgaard, M.; Jacobsen, B.H.; Hoffmann, C.C.; Dalgaard, T.; Odgaard, M.V.; Kjaergaard, C.; Powell, N.; Strand, J.A.; Feuerbach, P.; Tonderski, K. Policies for wetlands implementation in Denmark and Sweden–historical lessons and emerging issues. Land. Use Policy 2021, 101, 105206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES Secretariat. 2019. Available online: https://www.ccacoalition.org/resources/global-assessment-report-biodiversity-and-ecosystem-services-intergovernmental-science-policy-platform-biodiversity-and-ecosystem-service-full-report (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Barnes, D.K.A.; Sands, C.J.; Paulsen, M.L.; Moreno, B.; Moreau, C.; Held, C.; Downey, R.; Bax, N.; Stark, J.; Zwerschke, N. Societal importance of Antarctic negative feedbacks on climate change: Blue carbon gains from sea ice, ice shelf and glacier losses. Sci. Nat. 2021, 108, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriculture, D.M.O. Aftale om Grøn Omstilling. Deal on the Green Transition 2021. Available online: https://fm.dk/media/a2iphsxf/aftale-om-groen-omstilling-af-dansk-landbrug_a.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2024). (In Danish).

- Danish Agricultural Agency. LandbrugsGIS–Download Kortdata–Landbrugsstyrelsen. 2018. Available online: https://landbrugsgeodata.fvm.dk/ (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Danish Environmental Protection Agency 2025. Available online: https://mgtp.dk/groent-danmark/english-a-greener-denmark (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- O’Farrell, P.J.; Anderson, P.M. Sustainable multifunctional landscapes: A review to implementation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2010, 2, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.; Refsgaard, J.; Olesen, J.E.; Børgesen, C.D. Potential benefits of a spatially targeted regulation based on detailed N-reduction maps to decrease N-load from agriculture in a small groundwater dominated catchment. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 595, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Højberg, A.L.; Windolf, J.; Børgesen, C.D.; Troldborg, L.; Tornbjerg, H.; Blicher-Mathiesen, G.; Thodsen, H.; Erntsen, V. National Kvælstofmodel: Oplandsmodel til Belastning og Virkemidler. Bilag. 2015. Available online: https://data.geus.dk/pure-pdf/National_kv%C3%A6lstofmodel_oplandsmodel_metoderapport_sep2015.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Wang, X. No tillage increases soil organic carbon storage and decreases carbon dioxide emission in the crop residue-returned farming system. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermansen, J.E.; Jørgensen, U.; Lærke, P.E.; Manevski, K.; Boelt, B.; Jensen, S.K.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Dalsgaard, T.K.; Danielsen, M.; Asp, T.; et al. Green Biomass-Protein Production Through Biorefining; DCA-Nationalt Center for Fødevarer og Jordbrug: Tjele, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen, A.; Franco, A.M.; Early, R.I.; Fox, R.; Wintle, B.; Thomas, C.D. Prioritizing multiple-use landscapes for conservation: Methods for large multi-species planning problems. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 272, 1885–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiron, M.; Berg, Å.; Pärt, T. Do skylarks prefer autumn sown cereals? Effects of agricultural land use, region and time in the breeding season on density. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 150, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firbank, L.; Smart, S.; Crabb, J.; Critchley, C.; Fowbert, J.; Fuller, R.; Gladders, P.; Green, D.; Henderson, I.; Hill, M. Agronomic and ecological costs and benefits of set-aside in England. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 95, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, F.; Bolger, T. Effects of set-aside management on birds breeding in lowland Ireland. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 117, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. CAP 2023_27: Key Policy Objectives of the CAP 2023–27—European Commission 2023. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/common-agricultural-policy/cap-overview/cap-2023-27/key-policy-objectives-cap-2023-27_en (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Dalgaard, T.; Jacobsen, N.M.; Odgaard, M.V.; Pedersen, B.F.; Ejrnæs, R. Potentiale for Småbiotoper i Danmark. 2019. Available online: https://pure.au.dk/portal/da/publications/potentiale-for-sm%C3%A5biotoper-i-danmark/ (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Wetlesen, M.S.; Åby, B.A.; Vangen, O.; Aass, L. Simulations of feed intake, production output, and economic result within extensive and intensive suckler cow beef production systems. Livest. Sci. 2020, 241, 104229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picasso, V.D.; Modernel, P.D.; Becoña, G.; Salvo, L.; Gutierrez, L.; Astigarraga, L. Sustainability of meat production beyond carbon footprint: A synthesis of case studies from grazing systems in Uruguay. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.G.; Odgaard, M.V.; Bøcher, P.K.; Dalgaard, T.; Svenning, J.-C. Bundling ecosystem services in Denmark: Trade-offs and synergies in a cultural landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Panaro, S.; Poli, G. A spatial decision support system for multifunctional landscape assessment: A transformative resilience perspective for vulnerable inland areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinov, A.; Bousquet, F. Modelling with stakeholders. Environ. Model. Softw. 2010, 25, 1268–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Weber, D.; De Bie, K. Assessing the value of public lands using public participation GIS (PPGIS) and social landscape metrics. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 53, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustaoglu, E.; Sisman, S.; Aydınoglu, A. Determining agricultural suitable land in peri-urban geography using GIS and Multi Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) techniques. Ecol. Model. 2021, 455, 109610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odgaard, M.V.; Olesen, J.E.; Graversgaard, M.; Børgesen, C.D.; Svenning, J.-C.; Dalgaard, T. Targeted set-aside: Benefits from reduced nitrogen loading in Danish aquatic environments. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 247, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odgaard, M.V.; Turner, K.G.; Bøcher, P.K.; Svenning, J.-C.; Dalgaard, T. A multi-criteria, ecosystem-service value method used to assess catchment suitability for potential wetland reconstruction in Denmark. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 77, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markieta, M.; Rinner, C. Using Distributed Map Overlay and Layer Opacity for Visual Multi-Criteria Analysis. Geomatica 2014, 68, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Martínez, J.F.; Beltran, V.; Martínez, N.L. Decision support systems for agriculture 4.0: Survey and challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 170, 105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weersink, A.; Fraser, E.; Pannell, D.; Duncan, E.; Rotz, S. Opportunities and challenges for big data in agricultural and environmental analysis. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2018, 10, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odgaard, M.V.; Knudsen, M.T.; Hermansen, J.E.; Dalgaard, T. Targeted grassland production–A Danish case study on multiple benefits from converting cereal to grasslands for green biorefinery. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 223, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, S.V.; MacDonald, M.A.; van der Velden, N.; van Soesbergen, A.; Convery, I.; Mansfield, L.; Holt, C.D. Using the Ecosystem Services assessment tool TESSA to balance the multiple landscape demands of increasing woodlands in a UK national park. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 68, 101644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, N.A.; Ptak, E.N.; Graversgaard, M.; Iversen, S.; Reed, M.S.; de Vries, J.R.; Ingram, J.; Mills, J.; Neumann, R.K.; Kjeldsen, C. Social capital factors affecting uptake of sustainable soil management practices: A literature review. Emerald Open Res. 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J. GIS-based land-use suitability analysis: A critical overview. Prog. Plan. 2004, 62, 3–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, U.; Kristensen, T.; Jørgensen, J.R.; Kongsted, A.G.; De Notaris, C.; Nielsen, C.; Mortensen, E.Ø.; Ambye-Jensen, M.; Jensen, S.K.; Stødkilde-Jørgensen, L. Green Biorefining of Grassland Biomass. 2021. Available online: https://dcapub.au.dk/djfpublikation/djfpdf/DCArapport193.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Tamburini, G.; Aguilera, G.; Öckinger, E. Grasslands enhance ecosystem service multifunctionality above and below-ground in agricultural landscapes. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 59, 3061–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termansen, M.; Gylling, M.; Jørgensen, U.; Hermansen, J.; Hansen, L.; Knudsen, M.; Adamsen, A.; Ambye-Jensen, M.; Jensen, M.; Jensen, S. Green Biomass. 2016. Available online: https://pure.au.dk/ws/files/99837274/DCArapport073net.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Jørgensen, U.; Jensen, S.K.; Ambye-Jensen, M. Coupling the benefits of grassland crops and green biorefining to produce protein, materials and services for the green transition. Grass Forage Sci. 2022, 77, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, C.; Thorsøe, M.H.; Roell, Y.E.; Peng, Y.; Beucher, A.M.; Greve, M.B.; Greve, M.H.; Møller, A.B.; Jacobsen, N.M.; Odgaard, M.V. Provenance i Danmark:-En Kortlægning af Muligheder og Barrierer for Udvikling af Fødevareerhvervet Med Udgangspunkt i Typeprodukter; DCA-Nationalt Center for Fødevarer og Jordbrug: Tjele, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, K.; Kheir, R.B.; Greve, M.B.; Bøcher, P.K.; Malone, B.P.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B.; Greve, M.H. High-Resolution 3-D Mapping of Soil Texture in Denmark. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2013, 77, 860–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.; Hartemink, A.E.; Minasny, B.; Bou Kheir, R.; Greve, M.B.; Greve, M.H. Digital mapping of soil organic carbon contents and stocks in Denmark. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksen, J.; Jensen, N.P.; Jaconsen, H.B. Virkemidler Til Realisering af 2. Generations Vandplaner og Målrettet Arealregulering; DCA-Nationalt Center for Fødevarer og Jordbrug: Tjele, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pantera, A.; Papadopoulos, A.; Papanastasis, V.P. Valonia oak agroforestry systems in Greece: An overview. Agrofor. Syst. 2018, 92, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termansen, M.; Gylling, M.; Jørgensen, U.; Hermansen, J.; Hansen, L.B.; Knudsen, M.T.; Adamsen, A.P.S.; Ambye-Jensen, M.; Jensen, M.V.; Jensen, S.K.; et al. Grøn Biomasse; Aarhus University: Aarhus Centrum, Denmark, 2015; pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen, L.; Kristensen, T.; Nielsen, N.I.; Spleth, P.; Henriksson, M.; Swensson, C.; Hessle, A.; Vestergaard, M. Greenhouse gas emissions from beef production systems in Denmark and Sweden. Livest. Sci. 2015, 174, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.N.; Fagt, S.; Groth, V.M.; Christensen, T.; Biltoft-Jensen, A.; Matthiessen, J.; Andersen, L.N.; Kørup, K.; Hartkopp, H.; Ygil, H.K.; et al. Danskernes Kostvaner 2003–2008 Zander,Katrin;Risius,Antje;Feucht,Yvonne;Janssen,Meike;Hamm,Ulrich. 2010, pp. 6–129. Available online: https://www.food.dtu.dk/-/media/institutter/foedevareinstituttet/publikationer/pub-2010/danskernes-kostvaner-2003-2008.pdf?la=da&hash=3E4BA27FFF1BBC0AEF85CEC17A06CD789B1611E9 (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Ejrnæs, R.; Petersen, A.H.; Bladt, J.; Bruun, H.H.; Moeslund, J.E.; Wiberg-Larsen, P.; Rahbek, C. Biodiversitetskort for Danmark; Udviklet i Samarbejde Mellem Center for Makroøkologi, Evolution og Klima på Københavns Universitet og Institut for Bioscience ved Aarhus Universitet; Aarhus Universitet, DCE-Nationalt Center for Miljø og Energi: Aarhus Centrum, Denmark, 2014; pp. 1–96. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, A.; Bøcher, P.K.; Svenning, J.-C. Where are the wilder parts of anthropogenic landscapes? A mapping case study for Denmark. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2015, 144, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.B.; Vogdrup-Schmidt, M.; Dubgaard, A.; Normander, B.; Jørgensen, L.B.; Kristensen, I.T.; Dalgaard, T. Detaljeret Beskrivelse af Multikriterieanalyse(MCA)-Model Anvendt i Projektet “Fremtidens Landbrug”; Københavns Universitet, Frederiksberg: Institut for Fødevare og Ressourceøkonomi: Rolighedsvej, Danmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, K. Reestimation and Further Development in the Model N-LES, N-LES@ UDA3 to N-LES@ UDA4; Århus Universitet, Det Jordbrugsvidenskabelige Fakultet: Aarhus, Denmark, 2008; Report number 139. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen, J.E.; Lund, P.P.; JØrgensen, U.; Kristensen, T.; Elsgaard, L.; Sørensen, P.; Lassen, J. Virkemidler til Reduktion af Klimagasser i Landbruges; DCA-Nationalt Center for Fødevarer og Jordbrug: Tjele, Denmark, 2018; pp. 3–106. [Google Scholar]

- Odgaard, M.V.; Dalgaard, T.; Bøcher, P.K.; Svenning, J.-C. Site-specific modulators control how geophysical and socio-technical drivers shape land use and land cover. Geo Geogr. Environ. 2018, 5, e00060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odgaard, M.V.; Bøcher, P.K.; Dalgaard, T.; Moeslund, J.E.; Svenning, J.-C. Human-driven topographic effects on the distribution of forest in a flat, lowland agricultural region. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).