Abstract

Soil organic carbon (SOC) plays a crucial role in climate change mitigation by regulating atmospheric CO2 and maintaining ecosystem balance; however, its stability is influenced by land use in anthropized areas such as the tropical Andes. This study developed a dynamic compartmental model based on ordinary differential equations to simulate carbon fluxes among litter, humus, and microbial biomass under four land uses in the Las-Piedras River basin (Popayán, Colombia): riparian forest (RF), ecological restoration (ER), natural-regeneration (NR), and livestock (LS). The model includes two decomposition rate constants: k1, for the transformation of fresh organic matter, and k2, for the turnover of humified organic matter. It was calibrated using field data on soil physicochemical and biological properties, as well as carbon inputs and outputs. The results showed clear differences in SOC dynamics among land uses: RF had the highest SOC stocks (148.7 Mg ha−1) and microbial biomass, while LS showed the lowest values and the greatest deviation due to compaction and low residue input. The humus fraction remained the most stable pool (k2 ≈ 10−4 month−1), confirming its recalcitrant nature. Overall, the model reproduced SOC behavior accurately (MAE = 0.01–0.30 Mg ha−1) and provides a framework for improving soil carbon management in mountain ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Carbon sequestration refers to the capture of atmospheric C and its storage in the soil [1]. Soils have considerable potential to store C, but many are also undergoing continuous losses [2]. Soil organic carbon (SOC) is one of the largest terrestrial carbon reservoirs, resulting from organic matter inputs from plants and organisms as well as the decomposition of soil organic matter; therefore, SOC plays a crucial role in regulating the global climate, soil fertility, and ecosystem functioning [3]. However, in high-mountain tropical ecosystems such as those found in the Colombian Andes, the capacity to store SOC is strongly influenced by factors such as soil and climate conditions, vegetation type, and land use practices [4].

The conversion of natural forests to agricultural or grazing lands in tropical Andean ecosystems has resulted in a dramatic reduction in SOC, negatively affecting soil structure, fertility, and resilience [5]. The loss of natural cover due to land-use change has raised concerns about the depletion of SOC stocks through soil organic matter (SOM) mineralization and surface runoff caused by extensive grazing and intensive agriculture [6]. The removal of natural vegetation and the modification of organic inputs have a direct impact on soil structure, fertility, and biogeochemical dynamics. It has been estimated that such transformations can reduce SOC by more than 50% in the top 30 cm of the soil profile after decades of agricultural use [7]. Measuring SOC in the upper 30 cm is recommended for national inventories, given that SOC at greater depths tends to be stable or recalcitrant, with long residence times and low decomposition rates. By contrast, SOC storage in the topsoil is more dynamic due to microbial activity and continuous inputs and outputs of SOM [8].

In the context of climate change and agricultural frontier expansion, modeling SOC storage dynamics is necessary to understand processes and to project responses under different scenarios of climate change or anthropogenic disturbances [9]. Understanding decomposition, mineralization, and humification processes, as well as quantifying the magnitude and rate of carbon fluxes among soil compartments, is essential for explaining SOC storage dynamics [10]. In this sense, models have proven to be a valuable tool to assess the effects of physicochemical and biological factors on SOC under different land-use changes and management practices [11]. Some models manage to simulate key interactions and feedback mechanisms, providing insights into how soil carbon responds to both natural and anthropogenic disturbances [12].

Despite the extensive development of SOC models such as RothC, CENTURY, DNDC, and DayCent, most were parameterized for temperate or agricultural ecosystems and rarely account for the climatic heterogeneity and steep altitudinal gradients of tropical Andean regions, which strongly influence carbon stabilization and turnover processes [13,14,15]. These global models often overlook site-specific microbial dynamics, rapid litter turnover, and the strong influence of land-use change on carbon stabilization pathways [16,17]. In this context, developing models tailored to tropical mountain systems is essential to represent SOC fluxes and their controlling mechanisms accurately. The model proposed in this study introduces a novel approach by explicitly integrating field-based edaphic, biological, and management variables into a compartmental framework calibrated for Andean soils. This allows the evaluation of humified carbon (k2) as an indicator of long-term stability and supports the design of adaptive soil management strategies to enhance carbon sequestration in mountain ecosystems [18]. Unlike previous SOC models such as RothC, CENTURY, and MIMICS [10,11,19], which were developed for temperate or agricultural regions, the proposed framework simplifies the microbial–enzyme approach to enable calibration under the data-scarce conditions typical of tropical Andean Andisols. By explicitly coupling field-measured litter, humus, and microbial biomass with carbon fluxes, this model captures site-specific microbial and management effects often overlooked by global-scale models.

Building upon these considerations, the present study aims to develop a compartmental model based on ordinary differential equations that describes the flow of carbon among litter, humus, and microbial biomass [20], under different land-use systems in tropical Andean ecosystems. Four representative land covers were evaluated: riparian forest (RF), ecological restoration (ER), natural regeneration (NR), and livestock systems (LS). Using key edaphic variables, input data (e.g., litter carbon and monthly litterfall incorporation), and output data (e.g., basal soil respiration), the proposed model provides a tool for advancing sustainable carbon management in mountain landscapes undergoing anthropogenic transformations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The research was carried out in the Las Piedras River watershed, Cauca, Colombia (2°21′35″ N, 76°33′10″ W), which covers 66.26 km2 and is characterized by undulating terrain with slopes of 16–50%. Soils are Andisols derived from volcanic ash, with sandy loam texture (~10% clay), acidic pH (4.6–5.0), high Al saturation, and low Ca, Mg, and P contents. The climate corresponds to equatorial montane conditions, with sub-Andean and Andean bioclimatic zones, mean annual temperatures of 10.4–18.4 °C, and total annual precipitation of approximately 1630 mm. Rainfall is seasonal, with about 1460 mm during the wet period (October–May) and 500 mm during the dry period (June–September).

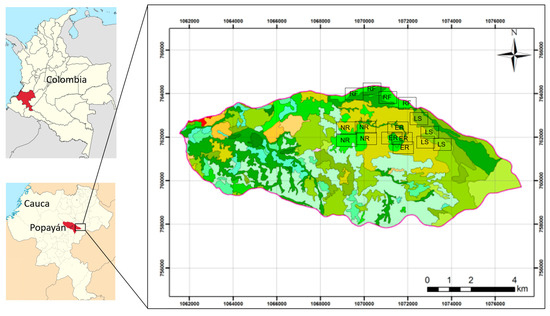

Four representative land covers were selected: riparian forest (RF), ecological restoration (ER), natural regeneration (NR), and livestock systems (LS), reflecting different levels of anthropogenic intervention and their relevance for soil organic carbon storage in mountain ecosystems (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area and distribution of different land uses: riparian forest (RF), ecological restoration (ER), natural regeneration (NR), and livestock (LS). Coordinates are expressed in UTM (meters), Datum WGS84, Zone 18° N.

2.2. Sampling Design and Site Selection

Within each land-use system—RF, ER, NR and LS—three representative plots (20 × 20 m) were selected based on vegetation cover, slope (<35%), accessibility, and homogeneity of management history. These land covers represent a gradient of anthropogenic intervention from near-pristine (RF) to highly managed (LS) systems. Soil samples were collected at 0–0.3 m depth, corresponding to the most dynamic SOC layer, during the dry season (July–August 2023) to minimize variability associated with soil moisture. Within each plot, five subsamples were taken using a zigzag pattern and composited to obtain one representative sample per plot. Bulk density cores and litter samples were collected simultaneously to ensure consistency in carbon input and stock estimates.

2.3. Soil Physical, Chemical, and Biological Properties

Bulk density (BD) was determined from undisturbed soil cores (64.45 cm3) collected at the target depth using a stainless-steel cylinder sampler, oven-dried at 105 °C for 24 h, and expressed as the ratio of oven-dry mass to core volume (g cm−3) [21]. Soil texture was analyzed using the Bouyoucos hydrometer method with readings at 40 s (sand) and 2 h (clay) after dispersion with sodium hexametaphosphate (Na6P6O18) at 5% concentration [22]. Soil pH was measured potentiometrically with a calibrated digital pH meter (Hanna Instruments HI 2211, Padova, Italy) in a 1:1 soil-to-water suspension after 1 h of intermittent stirring [23].

Effective cation exchange capacity (ECEC) was determined by extracting 2 g of air-dried soil (<2 mm) with 20 mL of 1 N ammonium acetate (NH4OAc, analytical grade, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at pH 7.0, shaken overnight, and filtered through Whatman No. 42 paper. Concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, and Al3+ were quantified using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Analytik Jena novAA 400, Jena, Germany) [24]. Microbial biomass carbon (Cmic) was estimated by the chloroform fumigation–extraction method with ethanol-free chloroform (Merck, ≥99.8%) on paired fumigated and non-fumigated samples; microbial C was extracted with 0.5 M K2SO4 after 3 days of incubation and quantified by dichromate oxidation [25]. Microbial activity was assessed by short-term respirometry (C–CO2) following the method of Alef & Nannipieri (1995) [26]. Soil samples (25 g) were incubated for 5 days in sealed glass jars (500 mL) at 25 °C, and CO2 was trapped in 1 N NaOH, precipitated with BaCl2, and titrated with 0.5 N HCl. The metabolic quotient (qCO2) was calculated as an indicator of substrate-use efficiency [26].

Carbon inputs and soil respiration were continuously monitored over one full annual cycle (February 2023–January 2024) to capture seasonal variability associated with rainfall and temperature. Litterfall and forest-floor litter were collected biweekly as described above, while basal soil respiration (SBR) was measured monthly under field-moist conditions using an LI-8100A Automated Soil CO2 Flux System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). This synchronized monitoring ensured that both carbon inputs and outputs reflected temporal dynamics relevant for model calibration and validation. Soil organic carbon (SOC) inputs were estimated from (i) litterfall, collected biweekly for one year using 12 traps (0.25 m2), dried at 65 °C (24–48 h), and weighed [27], and (ii) forest floor litter, sampled with 0.25 m2 PVC frames, dried under the same conditions, and converted to carbon assuming 48% of dry mass. Total soil C and N contents were determined with an NC 1500 Carlo Erba elemental analyzer [28].

SOC stocks (Mg ha−1) were calculated (Equation (1)) from organic carbon content (C_org), bulk density (BD), and sampling depth (P = 0.3 m):

where SOC: organic carbon stored in the soil (Mg ha−1), A: area (1 ha = 10,000 m2), Corg: grams of organic carbon in soil (Mg C/100 Mg), BD: bulk density of the soil (g/cm3), and D: depth of the soil layer. Since the content was estimated for the first 0.3 m of soil depth, D = 0.3 m.

2.4. Model Design

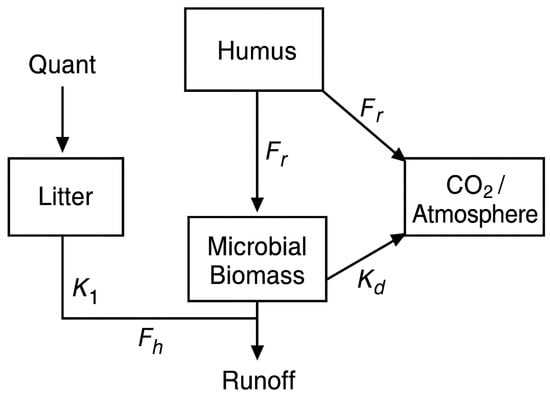

A dynamic compartmental model was developed to represent carbon fluxes among three main compartments: litter (L), humus (H), and microbial biomass (MB). The model describes carbon transfers between these compartments and carbon losses to the atmosphere as CO2 through a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs). Its structure is conceptually based on the coupling between microbial activity and decomposition kinetics in soil organic matter. It follows the general principles of microbial–enzyme-driven models such as RothC, CENTURY, and MIMICS [11,29,30].

Each parameter in Equations (2)–(4) was defined and obtained as follows: external carbon inputs (Quant) were directly measured from field litterfall and forest floor litter data; the mineralization (K1), humification (Fh), microbial assimilation (Fr, Assimilation2), microbial decay (Kd), and humus mineralization (K2) rates were estimated through model calibration constrained by observed soil respiration, microbial biomass, and SOC values. Surface carbon losses (Runoff) were represented as a minor flux based on field observations of erosion and litter displacement. These procedures ensured that all parameters were either empirically measured or realistically constrained by field data and literature values.

The temporal change in each compartment was simulated as:

where

Quant (Q_in) = external carbon inputs (litterfall, Carbon litter (CL) and forest floor litter C mulch (CMU));

Mineralization (K1) = flux of litter to CO2, conditioned by the C/N ratio and soil basal respiration (SBR);

Humification (Fh) = fraction of litter transformed into humus;

Assimilation (Fr) = fraction of litter carbon assimilated by microbial biomass;

Assimilation2 = fraction of humus assimilated by microbial biomass;

Decay (Kd) = microbial mortality returning to the litter pool;

Min2 (K2) = secondary mineralization of humus;

Runoff = surface carbon losses.

Initial conditions for each pool (L0, H0, MB0) were derived from field measurements of litter, humus, and microbial biomass carbon at the beginning of the monitoring period to ensure model reproducibility. The system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) was solved in R using the deSolve package, which employs a fixed-step fourth-order Runge–Kutta method and maintains mass balance across compartments [31].

The transfer rates (K1, K2, Fh, Fr, and Kd) were calibrated independently for each land cover—riparian forest (RF), ecological restoration (ER), natural regeneration (NR), and livestock systems (LS)—by minimizing the root mean square error (RMSE) between observed and simulated SOC values (L + H + MB), using the optim() function in R.

Parameter optimization employed the Nelder–Mead algorithm implemented in the optim() function of R, constraining parameters within ecologically realistic ranges derived from empirical data and previous studies on soil carbon modeling [10,31].

Model validation was conducted by comparing observed and simulated values of SOC, MB, and respiration equivalent carbon (eqC) represents the carbon released as CO2 through microbial respiration, used for model validation as an indicator of mineralization activity. Model performance was evaluated through mean absolute error (MAE), RMSE, and the coefficient of determination (R2).

The structure of the compartmental model, including the carbon pools and fluxes among litter, humus, microbial biomass, and losses to the atmosphere (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the compartmental soil organic carbon (SOC) model. Arrows indicate carbon fluxes among litter, humus, microbial biomass, and losses to the atmosphere. Parameters: K1 = litter decomposition rate; K2 = humus mineralization rate; Fh = humification fraction from litter to humus; Fr = assimilation fraction from humus to microbial biomass; Kd = microbial biomass decay rate. Quant = external carbon inputs (litterfall, CL, and coarse woody material, CMU); Runoff = surface carbon losses.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Properties

Soil properties varied notably across the four land-use types. ECEC values ranged from 3.73 meq 100 g−1 in RF to 5.7 meq 100 g−1 in LS, while pH was lowest in ER (4.6) and highest in LS (5.12). Carbon and nitrogen contents were greatest in RF (C = 4.97%, N = 1.18%) and lowest in NR (C = 3.41%, N = 0.87%), resulting in C/N ratios that peaked in ER (4.75) and declined in LS (3.70). SOC stocks showed a clear gradient, being highest in RF (148.68 Mg ha−1) and lowest in NR (97.3 Mg ha−1), with intermediate values in ER (119.24 Mg ha−1) and LS (102.85 Mg ha−1). Carbon inputs through litterfall (CL) and forest floor material (CMU) were substantially greater in RF (4.65 and 8.1 Mg ha−1, respectively) compared with LS (1.08 and 2.37 Mg ha−1). Bulk density was lowest in LS (0.90 g cm−3) and highest in ER (1.06 g cm−3). Soil texture was dominated by sand in all land uses (72–74%), with silt ranging from 21% in LS to 23.5% in ER, and clay remaining low (4–5.5%). Hygroscopic soil moisture (HSM) reached its maximum in RF (13.49%) and its minimum in LS (10.08%), while gravimetric soil moisture (SM) was also highest in RF (64.96%) and lowest in LS (62.75%). Microbial biomass carbon (MicC) was markedly higher in ER and RF (199.19 and 198.18 μg C g−1, respectively) than in LS (108.18 μg C g−1). Finally, microbial respiration (SMicR CO2) was greatest in ER (145.94 kg ha−1 month−1) and lowest in RF (108.01 kg ha−1 month−1), reflecting differences in microbial activity across land uses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Soil physicochemical and biological properties under different land uses in tropical Andean ecosystems.

3.2. Calibration of Model Parameters

The calibrated parameters of the SOC compartmental model varied across land-use types. The litter decomposition rate (K1) was highest in RF (0.308 month−1), followed by ER (0.190 month−1) and NR (0.154 month−1), while LS exhibited the lowest value (0.001 month−1), reflecting strongly reduced litter inputs and decomposition in pasture soils. The humus decomposition rate (K2) remained consistently low in all land uses (8 × 10−5–1 × 10−4 month−1), in line with the high stability of this carbon pool. The fraction of carbon allocated to humification (Fh) stabilized at 0.20 in RF, ER, and NR, with slightly higher values in LS (0.249). In contrast, the fraction directed to microbial assimilation and mineralization (Fr) reached the upper boundary in ER (0.80), RF (0.80), and NR (0.787), but was lowest in LS (0.20), indicating that forest and regenerating systems favored mineralization, whereas pastures favored stabilization. The microbial biomass decay rate (Kd) showed substantial variation, with the highest values in ER (0.632 month−1) and NR (0.555 month−1), moderate in RF (0.139 month−1), and the lowest in LS (0.010 month−1), reflecting limited microbial dynamics in pasture soils (Table 2).

Table 2.

Calibrated parameters of the SOC compartmental model.

3.3. Calibration and Validation of the SOC Model Under Different Land Uses

The calibration and validation of the SOC model showed consistent performance across land uses. Observed and modeled SOC values were closely aligned, with mean absolute errors (MAE) ranging from 0.01 Mg ha−1 in ER to 0.30 Mg ha−1 in NR, indicating a strong predictive capacity of the model for SOC. For microbial biomass carbon (MB), greater variability was detected, with MAE values between 0.31 Mg ha−1 in NR and LS and 1.34 Mg ha−1 in ER, reflecting the high sensitivity of microbial biomass to organic matter inputs and environmental conditions. Respiration equivalent carbon (eqC) was well reproduced by the model, with deviations below 0.1 Mg ha−1 in RF, ER, and NR, while LS showed a higher error (0.67 Mg ha−1), likely associated with reduced litter inputs and soil disturbances. The simulated carbon pools followed expected patterns: RF showed the highest accumulation of stabilized carbon in the humus pool (107.01 Mg ha−1) and the largest litter pool (30.94 Mg ha−1), followed by ER and NR, whereas LS presented the lowest humus (66.99 Mg ha−1) and litter (21.61 Mg ha−1) values, consistent with lower organic matter inputs and higher mineralization. These results confirm the ability of the compartmental model to represent SOC dynamics and its distribution among active (MB), labile (litter), and stabilized (humus) fractions under different Andean land uses (Table 3).

Table 3.

Observed and modeled values of SOC, microbial biomass (MB), respiration equivalent carbon (eqC), and simulated litter and humus pools across land-use types.

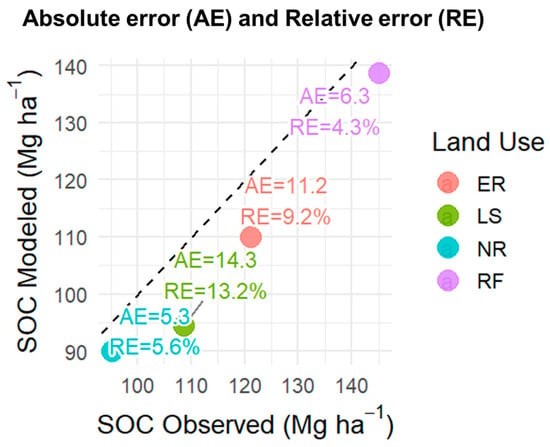

3.4. Model Performance: Observed Vs. Modeled SOC

The comparison between observed and modeled soil organic carbon (SOC) under different land uses (ER, LS, NR, and RF) (Figure 3). The 1:1 dashed line indicates the ideal fit, while the plotted points highlight deviations across systems. The largest discrepancy occurred in LS, with an AE of 14.3 Mg ha−1 and an RE of 13.2%, indicating a tendency of the model to underestimate SOC in grazing systems. In contrast, RF showed the smallest deviation (AE = 6.3 Mg ha−1; RE = 4.3%), suggesting a robust fit under forest conditions. Intermediate errors were observed in ER (AE = 11.2 Mg ha−1; RE = 9.2%) and NR (AE = 5.3 Mg ha−1; RE = 5.6%). Overall, these results demonstrate that the model reliably captured SOC dynamics across land uses, although performance varied depending on vegetation cover and management (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Observed vs. modeled SOC = soil organic carbon across land uses, showing absolute error (AE, Mg ha−1) and relative error (RE, %). Land uses: RF = Riparian Forest, ER = Ecological Restoration, NR = Natural Regeneration, LS = Livestock.

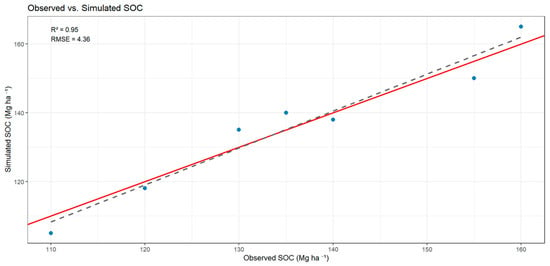

The comparison between observed and simulated soil organic carbon (SOC) values revealed a strong linear relationship across the four land-use systems. The model reproduced SOC variability with high accuracy, as indicated by the close alignment of data points along the 1:1 line and the low dispersion between simulated and measured values. This performance demonstrates that the model effectively captured the main carbon fluxes and stabilization dynamics under contrasting management conditions, confirming its suitability for Andean soils (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Relationship between observed and simulated soil organic carbon (SOC) values across land-use systems (RF, ER, NR, and LS). Blue dots represent observed SOC values. The solid red line represents the linear regression fit, and the dashed grey line indicates the 1:1 relationship. Model performance is summarized by the coefficient of determination (R2) and the root mean square error (RMSE).

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Carbon Dynamics Under Different Land Uses

The model showed that the main changes in soil C dynamics among the analyzed covers are reflected in litter stocks and microbial biomass. In riparian forests (RF), higher litter inputs and higher humidity favored high stocks of SOC (148.7 Mg ha−1), MicC (198.2 μg C g−1), and microbial respiration (108.0 kg ha−1 month−1), confirming that the continuous availability of organic matter stimulates both C accumulation and mineralization (Table 1). This can be explained because both the quantity and quality of organic waste influence the dynamics of SOC and microbial biomass, and moderate additions of good-quality waste promote carbon stabilization and prevent losses due to excessive respiration [32,33]. Conserved high-Andean ecosystems, such as native forests, contain the highest SOC levels, as acidity and humidity limit microbial mineralization. Furthermore, microbial biomass responds directly to residue quality and the C:N ratio, which explains the strong relationship between residue availability, SOC, and microbial activity in mountain Andisols [34]. Overall, these findings highlight that conserving vegetation cover and consistently supplying quality residues are essential for maintaining high levels of SOC and microbial biomass in mountain Andisols. In contrast, the livestock systems (LS) showed the lowest soil organic carbon reserves (102.9 Mg ha−1), microbial carbon (108.2 μg C g−1), and respiratory activity (112.7 kg ha−1 month−1). This is because ecosystems subjected to anthropogenic disturbances, such as LS, experience greater losses of organic carbon and lower carbon stability, highlighting the vulnerability of soils to intensive human use [35].

To understand these changes in soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks associated with different land uses, we must consider that microbial biomass is the driving force of the carbon cycle in soils, as it determines the fate of organic residues: whether they are lost as CO2 or stabilized as SOC. Furthermore, research confirms that conservation practices and high inputs of organic matter promote both SOC and microbial biomass, while intensive agricultural practices reduce them [36], in line with this regulatory role of microbial biomass on carbon dynamics, parameter calibration confirms these trends, showing that the riparian forest (RF) site had the highest litter decomposition rate (K1 = 0.308 month−1) and a high mineralization fraction (Fr = 0.80), indicating a predominance of microbial activity and respiration (Table 2). Conversely, the lowland savanna (LS) site had the lowest decomposition rate (K1 = 0.001 month−1) and the lowest microbial decay rate (Kd = 0.01 month−1), suggesting restricted biological activity and a tendency towards relative stabilization of carbon in humus. These results agree with [20], who reported low values of K1 and Fr in cultivated pastures, attributable to the low quality of the organic matter and soil compaction. Similar patterns have been observed in semiarid grasslands, where long-term grazing reduced microbial activity and litter decomposition efficiency due to soil compaction and lower residue quality [37,38].

The stability of the humus fraction, with very low decomposition rates (K2 ≈ 10−4 month−1), was common to all uses (Table 2), confirming that humus constitutes the most stable and recalcitrant compartment of soil carbon. Its slow decomposition implies long residence times, making it a key component for long-term carbon storage [10,39]. In contrast to this fraction, the more labile compartments showed greater sensitivity to changes in soil cover: litter decomposition (K1) was highest in RF and ER, intermediate in NR, and almost zero in LS, while microbial biomass (Kd) recorded high turnover rates in ER and NR compared to minimum values in LS. These results show that, although land use practices—(LS), (ER), (NR) or (RF)—significantly modify the dynamics of active carbon flows, humus remains the least sensitive compartment, consolidating its role as a stable and long-permanent reservoir in tropical Andean ecosystems; This finding coincides with that reported by [40], who observed that in tropical Andean ecosystems carbon is more stable and is protected within organo-mineral aggregates and complexes such as the most stable humic fractions, which restricts its mineralization and explains its persistence in the face of changes in land use. This observation is consistent with our results, as the modeled stability of the humus compartment (K2 ≈ 10−4 month−1 across all land uses) quantitatively supports the persistence mechanisms described by those authors. In our study, the convergence of low K2 values in contrasting land covers demonstrates that, despite substantial variation in litter and microbial activity, humified carbon remains largely unaffected by land-use change. This reinforces the notion that the long-term protection of SOC in Andean soils is primarily controlled by organo-mineral associations and microaggregate stabilization rather than by short-term biological turnover. Such agreement between field-calibrated model parameters and empirical observations in Andean systems highlights the model’s ability to represent the intrinsic resilience of recalcitrant carbon pools under diverse management regimes.

In contrast to humus stability, microbial biomass showed greater variability in both its magnitude and prediction. The greater deviation in MicC (MAE of up to 1.34 Mg ha−1 in ER) contrasts with the greater stability observed in SOC and respiration (Table 3). This is consistent with [4,20], who highlight the high sensitivity of microbial biomass to environmental factors such as precipitation seasonality, residue quality, and land use intensity. According to [4,41], in tropical soils, these conditions, combined with anthropogenic pressures, accelerate SOM mineralization dynamics, which explains the greater instability of the microbial compartment relative to the resilience of more recalcitrant carbon. This sensitivity justifies why ER, despite presenting high values of MicC (199.2 μg C g−1) and respiration (145.9 kg ha−1 month−1), simultaneously exhibits a high rate of microbial decay (Kd = 0.63 month−1), reflecting a dynamic state still in the process of stabilization. This is because in tropical and subtropical ecosystems, microbial communities tend to exhibit rapid turnover and fluctuating carbon use efficiency under variable inputs of residues and climatic stress, leading to accelerated mineralization of organic matter and transient instability of labile carbon stocks [42].

Taken together, these results confirm that carbon dynamics in tropical Andean ecosystems are tightly regulated by the quantity, quality, and timing of organic inputs, as well as by the intensity of human management. Land uses such as RF and ER favor rapid microbial assimilation and mineralization, promoting SOC accumulation through a balance between litter inputs and active microbial activity. In contrast, land uses such as LS exhibit limited dynamics, lower residue inputs, and reduced microbial activity, leading to significant reductions in SOC stocks and soil resilience to disturbances. These findings are consistent with those reported by [1,43,44], who emphasized that conservation practices and the maintenance of vegetation cover increase carbon sequestration capacity, while agricultural and livestock intensification weaken it. Furthermore, the persistence of stable carbon in humus, in contrast to the variability of labile compartments, underscores the need for management strategies that not only increase organic matter input but also protect recalcitrant soil fractions, thereby ensuring sustainable carbon sequestration in mountain landscapes that are highly vulnerable to land-use and climate change. This interpretation is supported by studies demonstrating that in volcanic Andisols, land use and management strongly influence organic-matter composition and soil chemistry, while climate, mineralogy, and aggregate stability play dominant roles in long-term SOC accumulation and protection against land-use intensification [45,46].

In summary, integrating empirical data with compartmental modeling reveals that sustainable land management in tropical Andean systems depends on maintaining organic inputs to sustain microbial activity while preserving mineral-associated carbon fractions that secure long-term soil stability.

4.2. Implications for Soil Carbon Management

The calibration and validation of the compartmental model confirmed its ability to robustly reproduce SOC dynamics in Andean ecosystems, with very low mean absolute errors (MAE) (0.01–0.30 Mg ha−1) across all land uses (Table 3). This accuracy is consistent with that reported by similar models applied in Andisols, where stabilized carbon fractions tend to show better prediction than more dynamic microbial compartments [20,47]. However, microbial biomass showed greater variability, particularly in ER (MAE = 1.34 Mg ha−1), reflecting its high sensitivity to environmental conditions and fresh organic matter pulses. In contrast, microbial respiration (eqC) was accurately represented in most land covers except for LS (MAE = 0.67 Mg ha−1), where model underestimation highlights the combined effect of low residue inputs and physical soil disturbance on biological activity. Several studies have shown that tillage and land cover removal practices cause macroaggregate breakdown, soil compaction, and porosity loss, which reduces protected microbial habitats and exposes previously inaccessible organic matter to oxygen, temporarily increasing mineralization and altering microbial activity [48,49]. Notably, short-term measurements often record spikes in respiration immediately after tillage due to the sudden release of labile organic C [49]. Conversely, no-till and reduced-tillage systems tend to preserve aggregate structure and maintain higher microbial biomass and more controlled respiration by conserving residues and soil pores [50]. These mechanisms allow us to understand why, in LS, with high physical disturbance, microbial activity is limited, even though model predictions reflect low values: the loss of structure, compaction, and residue reduction imposes stress on microorganisms, which can cause underestimations of actual activity in intermediate or deep sectors of the profile.

In line with the above, the results of this research show that the greatest deviations between observed and modeled SOC values occurred in LS, where the model underestimated reserves by 14.3 Mg ha−1 (RE = 13.2%), in contrast to RF, which showed the best fit with a difference of only 6.3 Mg ha−1 (RE = 4.3%) (Figure 2). This reinforces the idea that land uses such as LS require specific adjustments in the representation of carbon contributions via litter and in the effects of compaction on microbial respiration and infiltration. From a management perspective, these discrepancies underscore the need to increase the supply of fresh organic matter and minimize physical soil disturbance to ensure soil carbon sustainability in agricultural and livestock systems. Practices such as the systematic application of organic amendments (compost or manure), maintaining stubble, and integrating agroforestry systems have been shown to increase carbon inputs, stabilize microbial biomass, and reduce losses associated with accelerated mineralization [12]. Similarly, the adoption of minimum tillage practices can reduce CO2 emissions and surface runoff losses, consistent with recent evidence from degraded tropical pastures [6,51]. These findings highlight that using adaptive management strategies aimed at recovering organic matter and restoring soil structure can help reduce the predicted losses of SOC, ultimately boosting soil health and the accuracy of carbon modeling in tropical Andean environments. Additionally, incorporating real-world indicators like bulk density, aggregate stability, and microbial efficiency into the model calibration process could enhance its ability to understand the intricate interactions between management practices and SOC changes.

Although the model accurately reproduced SOC dynamics across the evaluated land-use systems, a higher prediction bias was observed in LS. This deviation likely reflects unmodeled processes associated with grazing intensity, animal trampling, and uneven nutrient deposition, which strongly influence soil compaction, aeration, and microbial activity. Such management-driven disturbances alter carbon inputs, decomposition rates, and microbial efficiency beyond the assumptions of the compartmental framework. Previous studies have reported that grazing pressure and trampling can reduce aggregate stability and microbial habitat availability, thereby constraining carbon stabilization and accelerating mineralization pulses after disturbance [38,52]. Moreover, the spatial heterogeneity of dung and urine deposition generates localized N enrichment that alters soil C:N ratios and stimulates pulses of microbial activity and soil respiration, producing hot-spots of C and N transformations within grazed landscapes. Several field and experimental studies have demonstrated that urine patches and dung deposits act as rapid sources of mineral N and labile C, increasing mineralization rates, greenhouse gas emissions, and short-term CO2 fluxes relative to surrounding soils [53,54]. These mechanisms may explain the underestimation of SOC in LS and underscore the need to incorporate grazing-related variables—such as stocking rate, surface disturbance, and N deposition—into future model versions to improve predictive performance under managed pasture conditions.

In summary, the evaluated compartmental model provides robust quantitative evidence of SOC dynamics under contrasting land covers and demonstrates its potential as a decision-support tool for adaptive soil management in Andean mountain landscapes. By identifying the compartments most sensitive to land-use change, the model underscores the importance of management strategies that enhance organic matter inputs while preserving the most stable SOC fractions. These practices are crucial for maintaining soil fertility and resilience in tropical upland systems and for reinforcing the role of these ecosystems as long-term carbon sinks that contribute to climate change mitigation. However, management-driven factors such as grazing, trampling, and nutrient deposition introduce variability not captured by the current model structure. The model also assumes constant microbial efficiency and stable temperature–moisture conditions, which may constrain its ability to simulate short-term responses under changing environments [55]. Moreover, spatial heterogeneity and microclimatic differences typical of Andean landscapes were only partially represented. Future refinements should incorporate microbial dynamics, nitrogen interactions, and spatially explicit carbon fluxes to improve model accuracy and applicability. Overall, this modeling strategy represents a significant step towards integrating the complexities of biophysical factors and management impacts into predicting SOC behavior in tropical mountain ecosystems.

5. Conclusions

The compartmental model developed in this research demonstrates that these types of tools are effective in understanding SOC dynamics across different land uses in tropical Andean ecosystems. The model accurately reproduced SOC storage and respiration, confirming that humus acts as the most stable carbon reservoir, while microbial biomass and litter are more sensitive to land-use changes. RF and RE soils maintain higher carbon stocks and greater microbial activity, whereas LS soils exhibit severe structural degradation and limited biological performance. These results emphasize that sustainable management practices—such as maintaining continuous organic inputs, minimizing soil disturbance, and integrating agroforestry systems—are essential for improving carbon sequestration and soil resilience in mountain landscapes. The proposed model offers a valuable tool for assessing carbon fluxes and supporting adaptive management strategies under future climate and land-use change scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.M.V. and R.R.-L.; methodology, V.A.M.V.; software, V.A.M.V. and R.R.-L.; validation, A.F.C. and D.J.M.P.; formal analysis, V.A.M.V.; investigation, V.A.M.V. and A.F.C.; resources, V.A.M.V., A.F.C. and D.J.M.P.; data curation, V.A.M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.M.V.; writing—review and editing, V.A.M.V.; visualization, R.R.-L. and D.J.M.P.; supervision, D.J.M.P.; project administration, V.A.M.V. and D.J.M.P.; funding acquisition, V.A.M.V., D.J.M.P. and R.R.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Tecnológico Nacional de México/Instituto Tecnológico de Chetumal provided financial support by contributing USD 1,000 toward the article processing charge (APC), as well as in-kind resources essential for the development of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No publicly archived datasets were generated or analyzed during this study.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the Universidad del Cauca and the Tecnológico Nacional de México/Instituto Tecnológico de Chetumal for their institutional support and the in-kind resources that made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript: SOC (Soil Organic Carbon), BD (Bulk Density), ECEC (Effective Cation Exchange Capacity), Cmic (Microbial Biomass Carbon), SBR (Soil Basal Respiration), RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), R2 (Coefficient of Determination), L (Litter Carbon Pool), H (Humus Carbon Pool), MB (Microbial Biomass Carbon Pool), L0, H0, MB0 (Initial Conditions), RF (Riparian Forest), ER (Ecological Restoration), NR (Natural Regeneration), LS (Livestock System), ODEs (Ordinary Differential Equations), NaOH (Sodium Hydroxide), HCl (Hydrochloric Acid), K2SO4 (Potassium Sulfate), Na6P6O18 (Sodium Hexametaphosphate), qCO2 (Metabolic Quotient), APC (Article Processing Charge).

References

- Don, A.; Seidel, F.; Leifeld, J.; Kätterer, T.; Martin, M.; Pellerin, S.; Emde, D.; Seitz, D.; Chenu, C. Carbon Sequestration in Soils and Climate Change Mitigation—Definitions and Pitfalls. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2024, 30, e16983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugato, E.; Leip, A.; Jones, A. Mitigation Potential of Soil Carbon Management Overestimated by Neglecting N2O Emissions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.; Monger, C.; Nave, L.; Smith, P. The Role of Soil in Regulation of Climate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20210084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez Fagua, C.; Landínez Torres, Á.Y.; Silva Parra, A. Carbono Orgánico y Su Dinámica En Suelos Tropicales: Una Revisión. Cult. Científica 2023, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis-Gutiérrez, M.; Rubiano-Sanabria, Y.; Usuga, J.C.L. Soils and Land Use in the Study of Soil Organic Carbon in Colombian Highlands Catena. Acta Univ. Carol. Geogr. 2019, 54, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Bravo, C.; Torres, A.; Tipán-Torres, C.; Vargas, J.C.; Herrera-Feijoo, R.J.; Heredia, R.M.; Barba, C.; García, A. Carbon Stock Assessment in Silvopastoral Systems along an Elevational Gradient: A Study from Cattle Producers in the Sumaco Biosphere Reserve, Ecuadorian Amazon. Sustainability 2023, 15, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldkamp, E.; Schmidt, M.; Markwitz, C.; Beule, L.; Beuschel, R.; Biertümpfel, A.; Bischel, X.; Duan, X.; Gerjets, R.; Göbel, L.; et al. Multifunctionality of Temperate Alley-Cropping Agroforestry Outperforms Open Cropland and Grassland. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Mireles, M.; Paz-Pellat, F.; Hidalgo-Moreno, C.; Etchevers-Barra, J.D. Soil Organic Carbon Depth Distribution Patterns in Different Land Uses and Management. Terra Latinoam. 2022, 40, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Challenges and Opportunities in Soil Organic Matter Research. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 60, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.E.; Paustian, K. Current Developments in Soil Organic Matter Modeling and the Expansion of Model Applications: A Review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 123004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, W.R.; Grandy, A.S.; Kallenbach, C.M.; Bonan, G.B. Integrating Microbial Physiology and Physio-Chemical Principles in Soils with the MIcrobial-MIneral Carbon Stabilization (MIMICS) Model. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 3899–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajal, M.; Ramírez, D.A.; Turin, C.; Schaeffer, S.M.; Konkel, J.; Ninanya, J.; Rinza, J.; De Mendiburu, F.; Zorogastua, P.; Villaorduña, L.; et al. From Rangelands to Cropland, Land-Use Change and Its Impact on Soil Organic Carbon Variables in a Peruvian Andean Highlands: A Machine Learning Modeling Approach. Ecosystems 2024, 27, 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Huang, S.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Ma, Y. Testing the RothC and DNDC Models against Long-Term Dynamics of Soil Organic Carbon Stock Observed at Cropping Field Soils in North China. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 163, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Benbi, D.K. Modeling Soil Organic Carbon with DNDC and RothC Models in Different Wheat-Based Cropping Systems in North-Western India. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2020, 51, 1184–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falloon, P.; Smith, P. Simulating SOC Changes in Long-Term Experiments with RothC and CENTURY: Model Evaluation for a Regional Scale Application. Soil Use Manag. 2002, 18, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Lützow, M.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Temperature Sensitivity of Soil Organic Matter Decomposition-What Do We Know? Biol. Fertil. Soils 2009, 46, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.; Dheebakaran, J.; Rangasamy, A.; Kaliappan, S.B.; Kovilpillai, B.; Alagarswamy, S.; Ramanathan, R. Microbial Carbon Dynamics in Tropical Forests: Linking Soil Processes to Atmospheric Impacts under Climate Stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 991, 179918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, W.R.; Hartman, M.D.; Sulman, B.N.; Wang, Y.P.; Koven, C.D.; Bonan, G.B. Carbon Cycle Confidence and Uncertainty: Exploring Variation among Soil Biogeochemical Models. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2018, 24, 1563–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkinson, D.S.; Rayner, J.H. The Turnover of Soil Organic Matter in Some of the Rothamsted Classical Experiments. Soil Sci. 1977, 123, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, M.C.; Olaya, J.F.C.; Galicia, L.; Figueroa, A. Soil Carbon Dynamics under Pastures in Andean Socio-Ecosystems of Colombia. Agronomy 2020, 10, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, G.R.; Hartge, K.H. Bulk Density. Methods Soil Anal. Part 1 Phys. Mineral. Methods 2018, 5, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, G.W.; Bauder, J.W. Particle-Size Analysis. Methods Soil Anal. Part 1 Phys. Mineral. Methods 2018, 5, 383–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, V.A.M.; Hurtado, F.M.; Jaramillo, D.F.J. Impact of Land Use on Organic Carbon Sequestration in a Natural Area of Medellín, Colombia. Acta Agron. 2022, 71, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya Salazar, J.C.; Menjivar Flores, J.C.; Bravo Realpe, I.D.S. Fraccionamiento y Cuantificación de La Materia Orgánica En Andisoles Bajo Diferentes Sistemas de Producción. Acta Agron. 2013, 62, 333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An Extraction Method for Measuring Soil Microbial Biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alef, K.; Nannipieri, P. Methods in Applied Soil Microbiology and Biochemistry; Academic Press: London, UK, 1995; p. 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celentano, D.; Zahawi, R.A.; Finegan, B.; Casanoves, F.; Ostertag, R.; Cole, R.J.; Holl, K.D. Restauración Ecológica de Bosques Tropicales En Costa Rica: Efecto de Varios Modelos En La Producción, Acumulación y Descomposición de Hojarasca. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2011, 59, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondragón Valencia, V.A.; Figueroa Casas, A.; Macias Pinto, D.J.; Rosas-Luis, R. Soil Organic Carbon Storage in Different Land Uses in Tropical Andean Ecosystems and the Socio-Ecological Environment. Earth 2025, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, S.; Porporato, A. Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Mineralization: Theory and Models across Scales. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1355–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, S.D.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Bradford, M.A. Soil-Carbon Response to Warming Dependent on Microbial Physiology. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soetaert, K.; Petzoldt, T.; Setzer, R.W. Solving Differential Equations in R: Package DeSolve. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 33, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Huang, Y.; Hungate, B.A.; Manzoni, S.; Frey, S.D.; Schmidt, M.W.I.; Reichstein, M.; Carvalhais, N.; Ciais, P.; Jiang, L.; et al. Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency Promotes Global Soil Carbon Storage. Nature 2023, 618, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, T.; Wakeel, A.; Cheema, S.A.; Iqbal, J.; Sanaullah, M. Influence of Quality and Quantity of Crop Residues on Organic Carbon Dynamics and Microbial Activity in Soil. Soil Environ. 2024, 43, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi-Murillo, G.; Diels, J.; Gilles, J.; Willems, P. Soil Organic Carbon in Andean High-Mountain Ecosystems: Importance, Challenges, and Opportunities for Carbon Sequestration. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2022, 22, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tariq, A.; Zeng, F.; Sardans, J.; Al-Bakre, D.A.; Peñuelas, J. Long-Term Anthropogenic Disturbances Exacerbate Soil Organic Carbon Loss in Hyperarid Desert Ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2025, 31, e70423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, R.K.; Walia, A. Advancements in Microbial Biotechnology for Soil Health; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 50, ISBN 978-981-99-9481-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, G.; Song, Z.; Wang, J.; Guo, L. Interactions of Soil Bacteria and Fungi with Plants during Long-Term Grazing Exclusion in Semiarid Grasslands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 124, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, W.; Yan, R.; Ren, Y.; Jin, D.; Xiong, W.; Zhang, G.; Cui, Z.; Xin, X.; Zhang, R. Grazing-Induced Microbiome Alterations Drive Soil Organic Carbon Turnover and Productivity in Meadow Steppe. Microbiome 2018, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Keulen, H. (Tropical) Soil Organic Matter Modelling: Problems and Prospects. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2001, 61, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jansen, B.; Absalah, S.; Kalbitz, K.; Chunga Castro, F.O.; Cammeraat, E.L.H. Soil Organic Carbon Content and Mineralization Controlled by the Composition, Origin and Molecular Diversity of Organic Matter: A Study in Tropical Alpine Grasslands. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 215, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, L.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Tarkka, M.; Reitz, T. Soil Microbial Communities Are More Disrupted by Extreme Drought than by Gradual Climate Shifts under Different Land-Use Intensities. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1649443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Vallejo, E.J.; Seeley, M.; Smith, A.P.; Marín-Spiotta, E. A Meta-Analysis of Tropical Land-Use Change Effects on the Soil Microbiome: Emerging Patterns and Knowledge Gaps. Biotropica 2021, 53, 738–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutika, L.-S.; Cerri, C.C.; Koutika, L.-S.; Bartoli, F.; Andreux, F.; Burtin, G.; Chon6, T.; Philippy, R. Organic Matter Dynamics and Aggregation in Soils under Rain Forest and Pastures of Increasing Age in the Eastern Amazon Basin. Geoderma 1997, 76, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti-Moreno, E.F.; Valenzuela-Balcázar, I.G. Impact of Soil Use on Aggregate Stability and Its Relationship with Soil Organic Carbon at Two Different Altitudes in the Colombian Andes. Agron. Colomb. 2019, 37, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kov, R.; Camps-Arbestain, M.; Calvelo Pereira, R.; Suárez-Abelenda, M.; Shen, Q.; Garbuz, S.; Macías Vázquez, F. A Farm-Scale Investigation of the Organic Matter Composition and Soil Chemistry of Andisols as Influenced by Land Use and Management. Biogeochemistry 2018, 140, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasner, D.; Abramoff, R.; Griepentrog, M.; Venegas, E.Z.; Boeckx, P.; Doetterl, S. The Role of Climate, Mineralogy and Stable Aggregates for Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics Along a Geoclimatic Gradient. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2024, 38, e2023GB007934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jansen, B.; Absalah, S.; Van Hall, R.L.; Kalbitz, K.; Cammeraat, E.H.E. Lithology-and Climate-Controlled Soil Aggregate-Size Distribution and Organic Carbon Stability in the Peruvian Andes. Soil 2020, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Ye, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, K. Tillage-Induced Fragmentation of Large Soil Macroaggregates Increases Nitrogen Leaching in a Subtropical Karst Region. Land 2022, 11, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, S.R.; Leinweber, P.; Jurasinski, G.; Eckhardt, K.U.; Glatzel, S. Tillage-Induced Short-Term Soil Organic Matter Turnover and Respiration. Soil 2016, 2, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li, P.; Guo, Y.; Aso, H.; Huang, Q.; Araki, H.; Nishizawa, T.; Komatsuzaki, M. Long-Term No-Tillage and Rye Cover Crops Affect Soil Biological Indicators on Andosols in a Humid, Subtropical Climate. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, R.T.; Klopatek, J.M.; Malin, R.C.; Klopatek, C.C. Carbon Pools and Fluxes along an Environmental Gradient in Northern Arizona. Biogeochemistry 1998, 43, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; You, C.; Tan, B.; Xu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, Z.; Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J. Effects of Livestock Grazing on the Relationships between Soil Microbial Community and Soil Carbon in Grassland Ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Merbold, L.; Leitner, S.; Wolf, B.; Pelster, D.; Goopy, J.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Interactive Effects of Dung Deposited onto Urine Patches on Greenhouse Gas Fluxes from Tropical Pastures in Kenya. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 761, 143184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Merbold, L.; Pelster, D.; Diaz-Pines, E.; Wanyama, G.N.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Effect of Dung Quantity and Quality on Greenhouse Gas Fluxes From Tropical Pastures in Kenya. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2018, 32, 1589–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abs, E.; Chase, A.B.; Manzoni, S.; Ciais, P.; Allison, S.D. Microbial Evolution—An under-Appreciated Driver of Soil Carbon Cycling. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2024, 30, e17268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).