Abstract

Comprehending the spatial–temporal transformation of urban resilience (UR) is fundamental for promoting sustainable urban growth in the Chinese context. In this study, a multi-dimensional index framework is developed to cover economic, social, ecological, and infrastructural aspects of resilience, assessing urban resilience across 282 prefecture-level cities between 2005 and 2022. By integrating the Time-Varying Entropy Method (TEM) with the Two-Stage Nested Theil Index (TNTI), we quantify the intensity and origins of spatial disparities in UR. Furthermore, spatial econometric models are employed to examine β convergence across regional and temporal dimensions. Additionally, the research adopts an Optimal Parameter-based Geographical Detector (OPGD) approach to explore and quantify the major determinants affecting urban resilience. The results reveal that (1) UR has significantly improved nationwide, with higher levels concentrated in eastern and southern China; (2) intra-provincial disparities are the dominant source of spatial differences, and continue to expand; (3) UR shows robust β-convergence nationally and regionally, although σ-convergence is limited to specific periods; (4) savings deposits per capita, ratio of employees, per capita fiscal expenditure and market size are identified as the core factors driving UR. The findings offer new insights into urban spatial governance under multi-dimensional constraints and challenges and serve as empirical guidance for narrowing resilience gaps and promoting balanced regional development.

1. Introduction

Urbanization signifies a transformative milestone in human societal development [1]. Referring to the World Cities Report 2022, the ratio of the urban population in 2021 has reached 56% [2]. The swift progression of urbanization redefines the intricate interplay among economic progress, environmental sustainability, and societal dynamics [3,4]. In this process, cities are constantly impacted by events like natural disasters, public health emergencies and terrorism [5,6]. Residents are increasingly expecting cities to be able to withstand, resolve and adapt to risks.

The economic development of China is considered a miracle in the world [7,8]. However, there are also some negative effects during the urban development process. According to relevant studies, natural disasters and public safety incidents have resulted in over 200,000 deaths in Chinese cities since the early 21st century. Over 200 million people were affected by the disasters, which greatly influences the effective functioning of urban systems in China [9]. The significance of developing resilient urban systems has been acknowledged by the Chinese government. As outlined in the 14th Five-Year Plan, the Chinese government underscores the imperative of reinforcing risk management within urban governance and creating resilient cities at a faster pace [10]. UR has emerged as a pivotal yardstick for gauging the caliber of urban development in China.

UR traces its conceptual roots to Holling’s ecological resilience theory [11], which highlights the capacity of ecosystems to absorb disturbances and rapidly restore their core functions [12]. Over time, the concept has evolved across urban studies, disaster science, and ecology, and is now widely used to describe the ability of urban systems to withstand external shocks, adapt to changing environments, and recover normal operations after disruption [13,14]. Current research on UR largely centers on three major themes.

First, the measurement of UR. Early studies, drawing on the SES [15,16] and SETS frameworks [17,18], evaluated resilience from the perspective of interactions among social, ecological, and technological subsystems Subsequently, some scholars expanded the evaluation structure to include five dimensions—economic, social, ecological, institutional, and infrastructural resilience [18,19,20]. Other studies, such as that by RA et al., have recognized the critical role of governance by incorporating institutional resilience into related domains. They evaluated UR across four dimensions [21,22,23]. In addition, some studies have evaluated UR from the capacity for economic resilience, social resilience, and community governance [24]. Methodologically, UR is typically evaluated as a multi-criteria decision-making problem, using composite methods such as PCA [20], entropy weighting [25], TOPSIS [26,27], MCDM [28] and matrix assessment model [29] to integrate multi-dimensional indicators into a single index. Second, the spatial–temporal evolution of UR. Studies consistently reveal marked spatial disparities across regions, within major urban agglomerations [30], and among cities within the same province [21]. For example, comparative analyses of cities such as New York, London, and Rotterdam indicate that resilience capacities differ notably across socio-spatial and governance contexts [31,32]. Common analytical tools include the Gini coefficient [27], Theil index [30], and hotspot analysis. Furthermore, an increasing number of studies employ convergence analysis to examine whether resilience gaps are widening or narrowing over time [25]. For example, Lu et al. [6] identified both α- and β-convergence in the Chengdu–Chongqing urban agglomeration, whereas Liu et al. found no absolute β-convergence among China’s provincial capitals but observed significant conditional β-convergence when accounting for time effects [33]. Third, the determinants of UR are inherently multi-dimensional. Existing research demonstrates that economic fundamentals—such as economic strength, digital finance, digital supply chain, digital economy, and industrial diversity—directly shape a city’s ability to invest in infrastructure and manage risks effectively [34,35,36]. Social factors, including population density, demographic aging, the quality of transport networks, urban shrinkage and agglomeration, and the provision of public services, influence both the vulnerability of urban systems and urbanization and their capacity to recover from shocks [37,38,39]. In addition, environmental conditions, such as green space coverage, pollution levels, and the degree of climate exposure, have been widely recognized as critical contributors to resilience performance [28,40].

Despite substantial progress, current UR research remains limited in several ways. First, existing studies tend to focus on specific metropolitan areas or individual urban agglomerations, while comprehensive assessments at the national scale are still scarce. Second, existing studies have paid limited attention to both the spatial differentiation and dynamic evolution of UR. On the one hand, there is a lack of systematic analysis regarding the relative influence of disparities at inter-regional, inter-provincial, and intra-provincial levels. On the other hand, the application of convergence analysis frameworks remains insufficient, making it difficult to assess whether, and to what extent, low-resilience cities are converging toward high-resilience ones across different spatial scales. Third, although numerous empirical analyses have identified socioeconomic or environmental determinants of UR, most rely on regression-based approaches that overlook spatial heterogeneity and potential interaction effects among influencing factors.

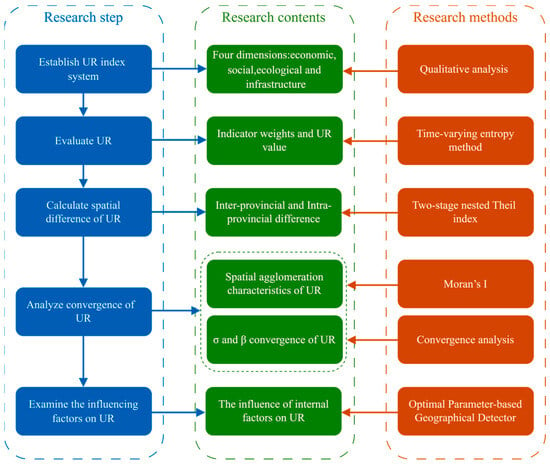

In response to the identified research gaps, this study establishes an integrated analytical framework to evaluate, decompose, and interpret UR across multiple spatio-temporal dimensions in China. Its main objectives are (1) to construct a unified multi-dimensional UR for 282 prefecture-level cities, integrating the economic, social, ecological, and infrastructural dimensions for consistent national-scale comparison; (2) to examine spatial inequality and temporal evolution of UR by using the TNTI framework to decompose inter-regional, inter-provincial, and intra-provincial disparities, and applying σ- and β-convergence models to assess whether UR gaps across regions are converging or diverging over time; and (3) to explore spatial heterogeneity and interaction effects among influencing factors through the OPGD model, revealing the multi-scale mechanisms shaping UR. Together, these objectives provide a comprehensive, data-driven national assessment of UR and offer insights for promoting balanced and adaptive urban development. The framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

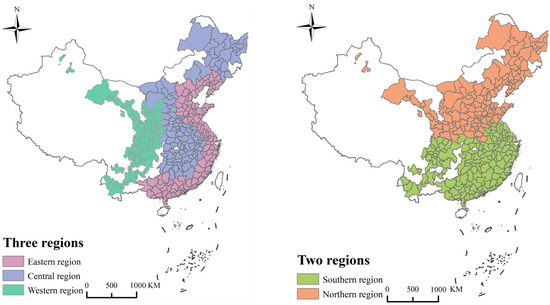

In accordance with the regional division framework issued by China’s NBS (2011), the sample cities are split into east, central, and west regions horizontally, and into north and south zones vertically. As shown in Figure 2, of the three regions, 114 cities belong to the eastern region, 109 cities belong to the central region, and 59 cities belong to the western region. Within the two regions, 154 cities belong to the southern region and 128 cities belong to the northern region. All spatial analyses for the 282 sample cities were conducted under the World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS 84, EPSG:4326).

Figure 2.

Study area and regional division. The map is based on the WGS 84 coordinate system (EPSG: 4326).

2.2. Indicator System for UR

The Resilience Alliance (RA) identifies four conceptual domains for examining UR-infrastructure and the built environment, resource and energy flows, institutional governance, and societal systems [15]. These domains emphasize the physical social foundations that enable cities to withstand disturbances, sustain metabolic processes, and maintain social cohesion [41].

However, while the RA framework provides a valuable conceptual foundation, it does not specify an operational indicator system. Its domains require contextual adaptation, as their measurement varies across governance and data settings. In China, the 14th Five-Year Plan and the National New Urbanization Plan highlight economic stability, social welfare, ecological sustainability, and infrastructure modernization as central to resilient urban development. Adopting these four dimensions aligns with national policy priorities and facilitates consistent, measurable, and comparable assessment of UR across cities.

In addition to the above four elements of resilience, institutional resilience has also been included in the UR framework by many scholars [12,14]. Nevertheless, institutional governance in mainland Chinese cities is largely embedded within economic management, infrastructure provision, and social service delivery rather than manifested as an independent measurable dimension. Since all mainland prefecture-level cities operate under a unified national governance system, observable cross-city variation in institutional structures is limited. Consequently, theoretical analysis, expert consultation, and other methodologies within UR literature are drawn upon. Based on empirical evidence and data availability, these four aspects as metrics for evaluating UR are adopted: economic resilience (ER), social resilience (SR), ecological resilience (ELR), and infrastructure resilience (IR).

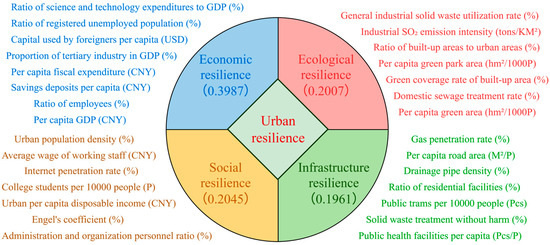

The specific indicators included in the UR evaluation system are presented in Figure 3. Among them, the “proportion of urban registered unemployed population” and “industrial SO2 emission intensity” are treated as negative indicators, whereas the remaining variables serve as positive indicators. The weights for each resilience dimension are derived using TEM, which objectively assigns weights based on the temporal variability and information contribution of each indicator. All data used in this study are primarily obtained from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook (https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=E0105, accessed on 25 November 2025).

Figure 3.

Indicator system of UR.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Time-Varying Entropy Method

To accurately estimate UR, this paper adopts the time-varying entropy method, which incorporates the time dimension into the traditional entropy approach. This enhancement improves the comparability of UR across different years, enabling a more precise analysis and better reflection of the dynamic changes and relative importance of data over time.

Step 1: Data standardization for positive and negative indicators by Equations (1) and (2).

where is the standardized value of , represent the initial value of indicator of city in year . and are the extreme values of .

Step 2: Equation (3) is used to normalize the standardized data, and Equation (4) for calculating the information entropy of each indicator.

where represents the amounts of sample periods, represents the amounts of city.

Step 3: Weight calculation for indicator .

Step 4: Calculate the overall UR value and its four sub-dimensions.

The difference between TEM and the traditional entropy method is reflected in the addition of time variable in steps 3 and 4. TEM can adjust the weight according to the variability of the data in each time period.

2.3.2. Two-Stage Nested Theil Index

As a widely used indicator, the Theil index is a significant metric for gauging developmental differences among regions [42]. Its two-stage nested counterpart expands upon the conventional single-stage Theil index approach, thus allowing for a more comprehensive breakdown of spatial differences. Drawing from the methodologies of Shorrocks [43] and Akita [44], the TNTI is devised with cities as fundamental spatial units. In contrast to the Dagum Gini coefficient employed by Shi et al. [45] for analyzing spatial disparities in UR, this study utilizes the TNTI methodology. This approach not only elucidates the spatial variations in UR in China but also enables the decomposition of disparities to the provincial level, offering distinct advantages over the Dagum Gini coefficient. Ranging from 0 to 1, the value is directly proportional to the magnitude of spatial difference. This index is mathematically expressed as follows:

where represents the overall Theil index of China’s UR, n is cities amounts, is the average UR at the national level, , and k correspond to region , province and city , respectively, and the overall spatial differences () are decomposed into intra-provincial differences (), inter-provincial differences () and inter-regional differences (), = + + .

2.3.3. Convergence Analysis Methods

convergence can be verified by coefficient, where is the mean value of the in the period , and is the number of cities. A declining trend in over time indicates the presence of σ convergence in UR, as shown in Equation (11):

The convergence refers to the phenomenon rate [46]. During the convergence process, neighboring regions can influence the local wherein a low-resilience city, characterized by a high growth rate, gradually closes the gap with a high-resilience city, ultimately reaching a state of convergence with an equivalent growth region and neglecting spatial factors, resulting in biased estimations [4,47]. Therefore, the spatial effect is included in the convergence test. Absolute convergence only considers the convergence state of UR development itself. This study constructs an absolute convergence regression model that includes spatial weights, as shown in Equation (12):

where indicates UR growth, represents the UR level of the region in the period , is the intercept, and is the convergence coefficient. value below 0 suggests UR convergence. Otherwise, the UR diverges. Spatial, time, and interference effects are represented by , , and . In Equation (13), is the convergence rate, and is the period (8 in this paper):

Conditional convergence further examines the convergence phenomenon after including additional control variables. According to the four dimensions of UR measured in this paper, economic growth (EG) [48], market size (MS) [49], technological innovation (TC) [36,50], foreign trade (FT) [51], financial revenue (FR) [52], and financial efficiency (FE) [53] were selected as control variables.

where is the dimension control variable set, refers to the dimension coefficient vector. The other symbols are defined as the same as above.

2.3.4. Optimal Parameter-Based Geographical Detector (OPGD)

Traditional geographical detectors require manual discretization of continuous data, which introduces a degree of subjectivity. In response to this limitation, this study adopts the OPGD, which determines the optimal spatial scale and discretization method by comparing five classification strategies: equal interval, natural breaks, quantile, geometric interval, and standard deviation interval. The corresponding formula is as follows:

The variable reflects the degree to which a factor explains spatial variation, with values ranging from 0 (no explanatory power) to 1 (complete explanation). The symbol denotes a specific category or stratum of the variable. and signify the number of spatial units in stratum and the entire region, respectively. and represent the intra-stratum and overall variance of the variable .

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution Patterns of UR

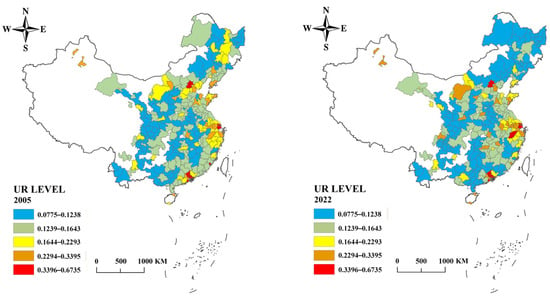

We employ ArcGIS 10.8 software to visualize the distribution characteristics of UR, and UR levels in different cities were divided into five categories by equal division method.

Figure 4 shows that the UR of China has significantly improved from 2005 to 2022. The distribution characteristics were eastern > central > western in the east–west direction, and southern > northern in the south–north direction. This is consistent with Liu et al. [54]. Most high-resilience cities are central municipalities and provincial capitals, with a notable concentration in the Yangtze River Delta region.

Figure 4.

UR geographical distribution characteristics. The map is based on the WGS 84 coordinate system (EPSG: 4326).

3.2. Spatial Differences and Source Structure Decomposition of UR

3.2.1. Spatial Differences in UR

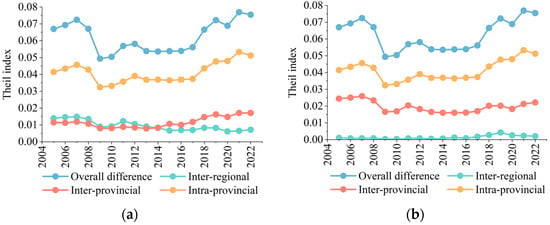

Figure 5 illustrates that disparities in UR have shown a generally increasing yet volatile trend, with the Theil index rising at an average annual rate of 1.20%. When considering the three major regions, the mean values of the Theil index for inter-regional, inter-provincial, and intra-provincial differences in UR stand at 0.0096, 0.0115, and 0.0412, respectively. From the evolution trends, inter-regional differences demonstrate a declining pattern from 2011 to 2022, while both inter-provincial and intra-provincial differences showcase an upward trend. Concerning the north and the south differences, the mean value of inter-regional, inter-provincial, and intra-provincial differences are 0.0014, 0.0197, and 0.0412, respectively. In terms of evolutionary tendencies, inter-regional and intra-provincial differences display an increasing trend, whereas inter-provincial differences display a descending trend. In sum, irrespective of the east–west or north–south direction, intra-provincial differences emerge as the primary source of spatial differences, whose contribution to the overall differences consistently surpass 40% (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Spatial differences and decomposition results of UR. (a) Three regions. (b) Two regions.

3.2.2. Inter-Provincial Differences

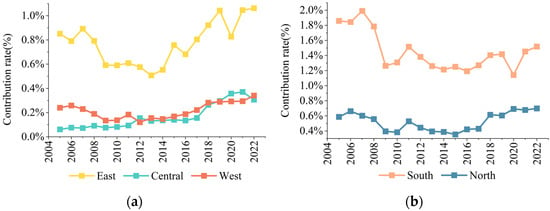

Figure 6 illustrates how provinces in various parts of the country contribute to spatial inequality. Among the three major zones, the eastern area exhibits the highest level of contribution, followed by the western zone, while the central zone plays a relatively minor role. Over time, the shares of the eastern and western parts initially declined before rising again, whereas the central and southern zones show opposite dynamics—an upward trend in one and a downward trend in the other. In contrast, the northern area maintains a consistent pattern throughout the study period.

Figure 6.

Inter-provincial differences. (a) Three regions. (b) Two regions.

3.2.3. Intra-Provincial Differences

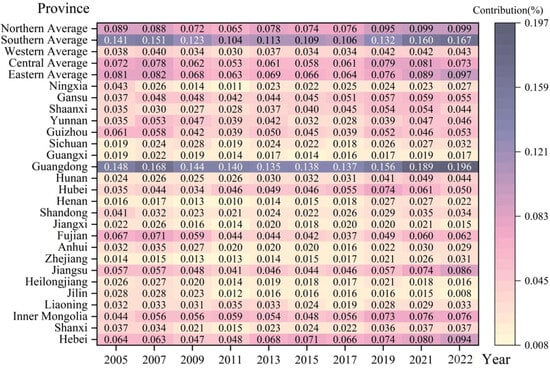

Figure 7 presents the intra-provincial differences in UR across China. The mean intra-provincial difference among the three major regions is 0.0595, which can be further divided into 0.0741, 0.0672, and 0.0371 in the eastern, central, and western regions, respectively. The eastern region displays notably greater intra-provincial differences in UR compared with the other regions. In terms of trends, all three major regions display an upward trajectory in intra-provincial differences in UR. The southern region experiences higher intra-provincial differences in UR compared with the northern region. Similarly, the trend analysis indicates an increasing pattern in intra-provincial differences for both these regions.

Figure 7.

Intra-provincial contribution.

An upward trend can be observed in the intra-provincial differences from both directions. Upon a closer examination of the spatial differences within each province, those provinces with the highest mean intra-provincial differences are Guangdong, Hebei, and Inner Mongolia, while those with the lowest mean intra-provincial differences are Guangxi, Jilin, and Zhejiang. The intra-provincial differences in Guangdong significantly surpass those in other provinces. Furthermore, the intra-provincial differences in Jilin province have experienced the largest decrease, while those in Zhejiang province show a substantial increase.

3.3. Convergence Results of UR

The enhancement of UR depends not only on the overall progress of UR within individual cities but also on the reduction in UR differences among cities. To determine whether spatial differences in UR are converging or diverging, this study applies σ and β convergence to conduct analysis.

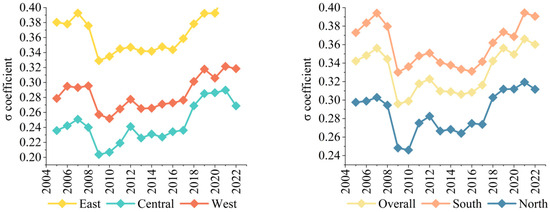

3.3.1. σ Convergence

convergence is considered to exist if the variability in UR across regions declines over the observed period. As shown in Figure 8, from an overall perspective, coefficient shows an upward trend. convergence is only evident between 2008 and 2016, with no significant convergence trend identified in the remaining years. Convergence across the five regions occurred only during the 2008–2016 timeframe, with no similar trends detected in other periods. The absence of convergence indicates that the UR distribution is relatively dispersed and the UR level varies greatly among different cities.

Figure 8.

Trend of σ coefficients.

3.3.2. β Convergence

convergence implies that UR in various regions gravitate towards their individual steady-state levels over time. Specifically, regions with lower UR exhibit faster growth compared to those with higher UR. This concept is pivotal for measuring the relative disparities in UR levels across cities. To identify the most appropriate convergence model for both the national and regional levels, this study applies the LM test, the LR test, and the Wald test. On the basis of the test results (Table 1), the bidirectional fixed Spatial Durbin Model is identified as the optimal choice for conducting convergence analysis.

Table 1.

Model selection test results.

Before the convergence analysis, we apply Moran’s I to assess the spatial correlation of UR (Table 2). Over the temporal dimension, the Moran’s I initially increase and then decrease. The mean index is 0.090, and both are significant at 1%. Therefore, a notable spatial interdependence can be observed among the UR values of Chinese cities, which is consistent with Cheng et al. (2022) [55].

Table 2.

Global Moran’s I for UR.

Table 3 shows regional convergence results. First, the regression coefficients for all major regions are significantly negative, pointing to an absolute convergence. This observation signifies a notable catching-up phenomenon occurring between cities with low UR and those with high UR. Second, the pace of convergence varies across regions. The central region demonstrates the fastest convergence speed at 2.4%, followed by the western region at 2.3% and the eastern region at 2.1%. The convergence rates in the southern and northern regions are 2.6% and 2.0%, respectively. Third, the positive and significant spatial spillover coefficient ρ in each region indicates the noteworthy spatial spillover effect of UR. Consequently, advancing UR necessitates not only individual city efforts but also harnessing the spatial spillover effect from neighboring regions to collectively enhance UR within the region.

Table 3.

Absolute convergence results.

3.3.3. Conditional Convergence Test

Table 4 presents the conditional convergence results for UR from the regional level. First, the regression coefficients remain significantly negative for all regions, thereby suggesting that the convergence characteristic persists after introducing control variables. Second, the eastern, central, western, southern, and northern regions have convergence rates of 2.2%, 2.8%, 2.6%, 2.7%, and 2.1%, respectively. When accounting for control variables, an acceleration in convergence is evident across the entire country and within each region, compared to the absolute convergence outcomes. Third, the spatial spillover coefficients are significantly positive across all regions and the entire country, demonstrating a significant positive spatial spillover impact in UR. The convergence characteristics of UR are same as those of Liu et al. (2022) [33].

Table 4.

Conditional convergence results.

The significance of control variables for the overall UR can be found. First, MS obtains significantly positive regression coefficients, implying that enhancements in these variables can effectively contribute to the convergence UR. Conversely, the significantly negative regression coefficient of FE suggests that improvement in financial efficiency may not necessarily lead to improvements in UR. From the regional perspective, the control variables EG, MS, TC, and FR have different impacts on the improvement in UR. EG demonstrates a noteworthy negative influence on northern region, MS exerts a significant positive effect within the eastern and western regions, TC displays a significant positive impact in the central and northern regions, and FE showcases a significant negative effect in the north.

3.3.4. Results of the OPGD

Given the constraints of research scope and data availability, this study selects the year 2022 as the reference point to explore the key internal and external factors influencing UR. As presented in Table 5, the top ten variables are ranked by their q-values, which reflect how strongly each factor contributes to the spatial heterogeneity of UR.

Table 5.

The q-value of single factor.

Among internal variables, economic indicators play a leading role, highlighting that UR is largely supported by the foundational strength of the economic system. Specifically, savings deposits per capita exhibit the highest explanatory power (q = 0.884), suggesting that household financial reserves serve as a significant buffer in the face of external shocks. This is followed by the ratio of employees (q = 0.744) and per capita fiscal expenditure (q = 0.723), reflecting the importance of both labor market dynamism and the government′s capacity for resource allocation in resilience building. Regarding external factors, market size stands out with a q-value of 0.728, indicating that a city′s level of embeddedness within regional economic networks—and its capacity to facilitate resource flows—contributes to improving resilience in the face of disruptions and facilitating recovery processes.

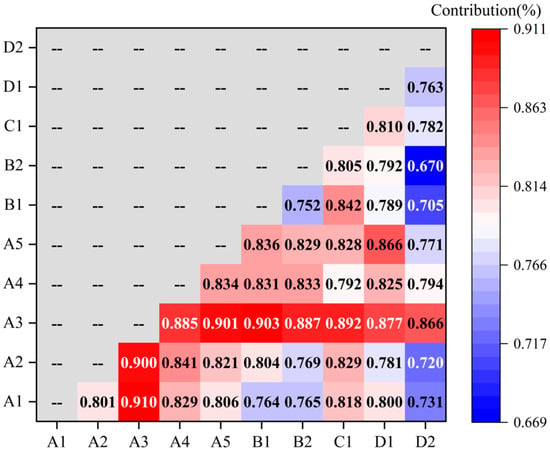

To further investigate the interactive effects among internal factors on UR, this study applies bivariate factor detection to the identified variables, calculating the joint explanatory power (q value) of all possible two-variable combinations. The results, as shown in Figure 9, indicate that for most combinations, the q values are significantly higher than those of the individual factors, demonstrating a clear pattern of bivariate enhancement.

Figure 9.

Interaction factors explanatory power.

Among the variables, per capita savings deposits emerge as the most interactive core variable, with its combinations with multiple economic and social indicators yielding q values consistently above 0.884—for instance, , , and . This suggests that financial resilience can form stable synergistic effects with other systemic components, playing a critical role in supporting urban recovery and transformation. In addition, the external factor market size shows a significant enhancement effect when combined with various internal factors, underscoring the strong relationship between a city’s role in the regional economic network and its systemic recovery capacity.

Overall, the findings reinforce the notion that UR is driven by multifactorial synergy, highlighting the importance of integrated planning and coordinated governance across multiple dimensions in future UR development.

3.4. Robust Check

To ensure the robustness of the results, this study performs a series of validation checks from three perspectives: spatial inequality measures, spatial weight sensitivity, and influencing factor identification.

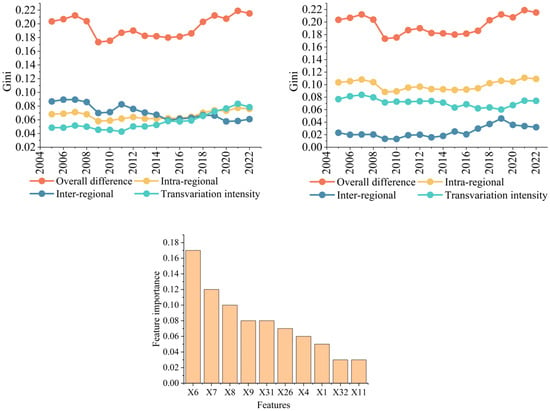

First, we re-estimated UR disparities using the Dagum Gini coefficient as an alternative to the TNTI. Figure 10 demonstrates that the results are highly consistent with those obtained using the TNTI, showing a persistent rise in UR disparities from 2005 to 2022, with intra-regional differences consistently emerging as the dominant source. This consistency reinforces the credibility of our spatial inequality decomposition.

Figure 10.

Robustness test of Gini coefficient and driving factors.

Second, we tested the sensitivity of the β-convergence results by altering the spatial weight matrices used in the spatial econometric models (see Table 6). Specifically, we compared outcomes under geographical distance, geo-economic, and mixed spatial weight matrices. Across all model specifications, the convergence coefficients remain significantly negative, and spatial lag effects are also significant. It indicates that our conclusions on UR convergence are not sensitive to spatial matrix selection and remain robust under different spatial structures.

Table 6.

Robustness test of convergence.

Third, to validate the robustness of the factor detection results derived from the OPGD, we employed a Random Forest model to re-rank the importance of influencing variables. As shown in Figure 10, the variable rankings generated by the Random Forest model are highly consistent with those of the OPGD, particularly for the top contributing factors. This strong alignment confirms the reliability of our identification of key drivers and enhances the robustness of our conclusions regarding the determinants of UR. In Figure 10, the variables X6, X7, X8, X9, X31, X26, X4, X1, X32, and X11 correspond to the following indicators in Table 5: A3, A4, A5, B1, D1, C1, A2, A1, D2, and B2, respectively.

4. Discussion and Policy Implications

4.1. Discussion

In terms of UR spatial distribution, eastern coastal areas have high UR levels, and there is a clustering phenomenon [42]. UR in eastern cities is generally higher than that in the central and western regions, exhibiting a clear spatial gradient pattern. This is inseparable from the continuous investment in urban environment and infrastructure in the eastern region [56], while in the central and west, the low level of urbanization and inadequate economic development are still the primary problems to be solved. The low level of UR is mainly due to the low degree of ELR and IR.

The TNTI method is employed for the first time to decompose the UR spatial differences at the prefecture-level city level. We find an interesting phenomenon: that the intra-provincial and inter-provincial differences in the central region are expanding simultaneously. A study reveals that the central region is centralizing the resources of whole provinces to cultivate megacities [57]. Provincial capitals like Wuhan, Changsha, Hefei and Zhengzhou already account for nearly a third of the province’s GDP. The substantial economic volume noted by Shi et al. [58] has engendered a pronounced siphon effect in urban centers. This effect channels high-quality production factors towards these cities, exacerbating the disparity in resource allocation. Consequently, this dynamic enhances UR in provincial capitals while simultaneously widening the UR differences across the provinces [59]. In addition, the central regions of Shanxi and Jiangxi province are rich in mineral resources [60]. The development system dominated by mining industry has caused several “urban diseases” in the late stage of development [61], which reduced the capability of these cities to resist risks and led to the widening of inter-provincial UR differences.

This study examines the spatio-temporal trends of UR from the prefecture-level city level, utilizing the TNTI to decompose the sources of UR spatial differences. The findings aim to provide individual cities with insights into their own UR development status and positioning, aid the nation in clarifying the specific sources of differences, and facilitate collective efforts towards enhancing UR collaboration on a broader scale. Through convergence analysis, we observe that UR demonstrate significant β convergence, while σ convergence is only present in select years. This suggests that although cities with lower UR are experiencing accelerated growth, the significant disparities between low-UR and high-UR cities continue to hinder the diminution of absolute differences in UR levels. Beyond spatial trends, the OPGD approach is further applied in this study to analyze the comparative impact of internal and external influencing factors. The results reveal that internal factors exert a stronger impact overall, and that the explanatory power of multi-factor interactions exceeds that of individual factors.

4.2. Policy Implications

First, given the low UR level in western China, it is imperative to rectify the deficits in ELR and IR in these areas. The arid climate in this region poses significant challenges, including soil erosion and frequent dust storms. To tackle these problems, it is essential for governmental bodies to strengthen environmental governance, and devise and implement robust strategies for extreme weather conditions.

Second, it is crucial to recognize that intra-provincial differences significantly contribute to regional disparities in UR. It is essential for governments to clearly define the developmental roles and functions of each city within a province and to establish policies that support coordinated urban development, addressing the collective needs of all cities. Additionally, enhancing policy support for cities with lower URs within the province is imperative, alongside implementing institutional measures to accelerate their improvement. Furthermore, governments should focus on the spatial spillover effects from high-UR cities to foster a systematic and synergistic spatial development pattern.

Third, based on the findings of UR convergence analysis, it is imperative to prioritize narrowing the UR difference at a national level for collaborative enhancement of UR. The government can effectively promote economic, market, and financial development in low-UR cities to increase the UR growth rate, ultimately working towards reducing the disparity in UR levels nationwide.

Ultimately, enhancing UR requires a holistic policy approach focused on strengthening household financial capacity, optimizing employment structures, improving the efficiency of public spending, and expanding market size. Cross-sectoral and forward-looking urban governance should replace fragmented approaches to foster integrated development across economic, social, and infrastructural systems. These efforts are essential to building a robust, adaptive, and high-resilience urban system.

4.3. Limitations

Despite its contributions, this study leaves open several issues that merit deeper investigation. Due to data limitations, the scope is confined to 282 prefecture-level cities, potentially overlooking spatial heterogeneity, especially at sub-prefectural scales. Incorporating county-level data in future work would allow for enhanced spatial granularity and coverage. Furthermore, despite the adoption of a unified multi-dimensional indicator system, its development was inevitably influenced by disciplinary paradigms and data availability, possibly omitting vital dimensions of UR. Future frameworks could address this by integrating the inherently complex and multi-dimensional characteristics of resilience. Lastly, the study’s exclusive focus on China limits its generalizability. Applying this framework in other national or regional contexts would facilitate comparative analyses and deepen insights into how institutional and governance variations shape resilience outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study assessed UR across 282 cities in China from 2005 to 2022 using the time-varying entropy method (TEM), the two-stage nested Theil index (TNTI), σ- and β-convergence tests, and the optimal parameter-based geographical detector (OPGD). The analysis yields several key findings.

First, China’s overall UR has improved markedly, with the national mean UR index rising from 0.14 in 2005 to 0.19 in 2022. Spatially, UR demonstrates pronounced heterogeneity, with the southeastern region—especially the Yangtze River Delta—showing levels over 30% higher than the national average. Second, spatial inequality in UR has generally widened, as evidenced by the Theil index, which increased at an average annual rate of 0.94%. Among sources of spatial disparity, intra-provincial differences dominate, contributing over 40% of the total variation, while inter-regional differences declined slightly after 2011. Third, UR exhibits strong β-convergence but limited σ-convergence. σ-convergence was evident only during 2012–2017, whereas both absolute and conditional β-convergence are confirmed at the national and regional levels. The central (7.2%) and southern (6.2%) regions display the fastest convergence rates, suggesting accelerated catch-up among lower-resilience cities. Finally, OPGD results reveal that UR is primarily driven by multi-factor synergies, with economic variables remaining dominant. Among internal factors, savings deposits per capita (q = 0.884), ratio of employees (q = 0.744), and per capita fiscal expenditure (q = 0.723) show the highest explanatory power. Among external factors, market size (q = 0.728) exerts the greatest influence. Bivariate analysis further demonstrates that combinations of factors exhibit higher explanatory power than single ones, confirming the existence of a significant multi-factor enhancement effect in shaping UR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.H. and J.H.; methodology, G.H. and T.S.; software, Y.H. and H.A.; investigation, J.H. and G.H.; resources, T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.H. and T.S.; writing—review and editing, J.H. and T.S.; visualization, Y.H. and H.A.; funding acquisition, J.H. and G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (72203197, 72103048, 72373044), the Key Project of Philosophy and Social Science Research in Colleges and Universities in Henan Province (2026-YYZD-23), Nanhu Scholars Program for Young Scholars of XYNU.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the conclusions of this study are available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Korhonen, J.; Snäkin, J.P. Quantifying the relationship of resilience and eco-efficiency in complex adaptive energy systems. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 120, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habitat, U.N. World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Chen, Y.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. Interplay of urbanization and ecological environment: Coordinated development and drivers. Land 2023, 12, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, W.; Wang, M.; Yang, D.; Chen, W. Green efficiency of water resources in Northwest China: Spatial-temporal heterogeneity and convergence trends. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirzadeh, M.; Sobhaninia, S.; Sharifi, A. Urban resilience: A vague or an evolutionary concept? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 81, 103853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Lu, X.; Jiao, L.; Zhang, Y. Evaluating urban agglomeration resilience to disaster in the Yangtze Delta city group in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y.; Cai, F.; Li, Z. The China Miracle: Development Strategy and Economic Reform, Revised Edition; The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press: Hong Kong, China, 2004; pp. 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y. The Chinese Growth Miracle: Handbook of Economic Growth; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 943–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Meie, P.; Yi, L.; Kexin, C.; Yisong, Z.; Zhou, X. A time-series analysis of urbanization-induced impervious surface area extent in the Dianchi Lake watershed from 1988–2017. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Du, S.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, T.; Zhao, Y.; He, W.; Xue, H.; He, Y.; Gao, X.; et al. Unveiling the impact mechanism of urban resilience on carbon dioxide emissions of the Pearl River Delta urban agglomeration in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Foundations of Socio-Environmental Research: Legacy Readings with Commentaries; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1973; pp. 460–482. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H. Urban resilience and urban sustainability: What we know and what do not know? Cities 2018, 72, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.; Falcão, M.J.; Komljenovic, D.; de Almeida, N.M. A systematic literature review on urban resilience enabled with asset and disaster risk management approaches and GIS-based decision support tools. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirzadeh, M.; Sobhaninia, S.; Buckman, S.T.; Sharifi, A. Towards building resilient cities to pandemics: A review of COVID-19 literature. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resilience Alliance. Assessing Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems: Workbook for Practitioners, Version 2.0. SETS. 2010. Available online: https://www.resalliance.org/files/ResilienceAssessmentV2_2.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Kim, Y.; Carvalhaes, T.; Helmrich, A.; Markolf, S.; Hoff, R.; Chester, M.; Li, R.; Ahmad, N. Leveraging SETS resilience capabilities for safe-to-fail infrastructure under climate change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 54, 101153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. Resilience of urban social-ecological-technological systems (SETS): A review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellmann, T.; Andersson, E.; Knapp, S.; Lausch, A.; Palliwoda, J.; Priess, J.; Scheuer, S.; Haase, D. Reinforcing nature-based solutions through tools providing social-ecological-technological integration. Ambio 2023, 52, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N.; Ge, Y.; Rott, E.; Isgandar, H. Urban resilience: Multidimensional perspectives, challenges and prospects for future research. Urban Gov. 2024, 4, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yang, H.; Chen, L.; Huang, H.; Chang, M. Urban resilience assessment and multi-scenario simulation: A case study of three major urban agglomerations in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 111, 107734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Jia, W.; Zhao, H.; Xiang, P. A framework for urban resilience meas-urement and enhancement strategies: A case study in Qingdao, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 367, 122047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, C.; Bower, P.; Webb, R.T.; Munford, L. Measurement of community resilience using the Baseline Resilience Indicator for Communities (BRIC) framework: A systematic review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 95, 103870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datola, G. Implementing urban resilience in urban planning: A comprehensive framework for urban resilience evaluation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudec, O.; Reggiani, A.; Šiserová, M. Resilience capacity and vulnerability: A joint analysis with reference to Slovak urban districts. Cities 2018, 73, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J. Evolution and analysis of urban resilience and its influencing factors: A case study of Jiangsu Province, China. Nat. Hazards 2022, 113, 1751–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varchandi, S.; Memari, A.; Jokar, M.R.A. An integrated best–worst method and fuzzy TOPSIS for resilient-sustainable supplier selection. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 11, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Zhao, H.; Yue, L.; Liu, Y.; Guo, J.; Tang, J.; Zhao, P. Spatial heterogeneity of urban resilience: Quantifying key determinants by spatial ma-chine learning model embedded in density-structure-function frame-work. Cities 2025, 167, 106305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, S.; Zhang, D.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y. An interpretable machine learning-assisted urban resilience evaluation and determinants identification: A case study of the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 134, 106930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Chen, G.; Yao, B.; Wu, J. Urban resilience assessment matrix consid-ering spatiotemporal processes: Model proposal and application. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 135, 106988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sun, Z.; Du, M.D. Drivers of Urban Resilience in Eight Major Urban Agglomerations: Evidence from China. Land 2022, 11, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Brooks, E.; Mehmood, A. Evolutionary resilience and strategies for climate adaptation. Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 299–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P. Urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why? Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lei, Y.; Fath, B.D.; Hubacek, K.; Yao, H.; Liu, W. The spatio-temporal dynamics of urban resilience in China’s capital cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Shi, J.; Tao, Y. The impact and mechanism of digital finance on ur-ban economic resilience. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 106, 104468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhong, M.; Dong, Y. Digital economy and risk response: How the digital economy affects urban resilience. Cities 2024, 155, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yang, B.; Yuan, C. The impact of supply chain digitalization on urban resilience: Do industrial chain resilience, green total factor productivity and innovation matter? Energy Econ. 2025, 145, 108443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Sun, H.; Wu, H. How does urban shrinkage influence urban resilience? Empirical evidence from Northeast China. Habitat Int. 2026, 167, 103646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Wu, W.; Shang, T.; Wu, P.; Yu, B. Assessing the impact of population urbanization on urban resilience: Empirical evidence from rapidly urbanizing China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 117, 108189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Ma, H. The impact of basic public service provision on urban economic resilience: Evidence from 281 cities in China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 104, 104678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feofilovs, M.; Romagnoli, F. Dynamic assessment of urban resilience to natural hazards. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 62, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Yu, X. Enhancing the resilience of urban energy systems: The role of artificial intelligence. Energy Econ. 2025, 144, 108313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Jiao, Y.; Cheng, N. An Innovative decision-making scheme for the high-quality economy development driven by higher education. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorrocks, A.F. The Class of Additively Decomposable Inequality Measures. Econometrica 1980, 48, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, T. Decomposing regional income inequality in China and Indonesia using two-stage nested Theil decomposition method. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2003, 37, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Qiao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J. The regional differences and random convergence of urban resilience in China. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2022, 28, 979–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K. Econometric Convergence Test and Club Clustering Using Stata. Stata J. 2017, 17, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, T.; Hao, X.; Li, J. Effects of public participation on environmental governance in China: A spatial Durbin econometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 129042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Jiang, W. How does regional integration policy affect urban resilience? Evidence from urban agglomeration in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 104, 107298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xie, W.; Wu, W.-Z.; Zhu, H. Predicting Chinese total retail sales of consumer goods by employing an extended discrete grey polynomial model. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 102, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, M.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, Z.; Bu, Y. The impact of digital inclusive finance on urban economic resilience in China: Spatial spillover and mechanism analysis. Dev. Sustain. Econ. Financ. 2025, 8, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhao, L. Digital Finance, Talent Aggregation, and Urban Economic Resilience. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 108823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, N.; Mishra, T.; Parthasarathy, D. The impact of floods and cyclones on fiscal arrangements in India: An empirical investigation at the sub-national level. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 110, 104620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Levine, R. Financial Institutions and Markets across Countries and over Time: The Updated Financial Development and Structure Database. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2010, 24, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, Z.; Cheng, H.; Gross, L.; Li, X.; Wei, B.; et al. Nighttime light perspective in urban resilience assessment and spatiotemporal impact of COVID-19 from January to June 2022 in mainland China. Urban Clim. 2023, 50, 101591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, C. Exploring the spatio-temporal evolution of economic resilience in Chinese cities during the COVID-19 crisis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84, 103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathwani, J.; Lu, X.; Wu, C.; Fu, G.; Qin, X. Quantifying security and resilience of Chinese coastal urban ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 672, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; LeGates, R.; Zhao, M.; Fang, C. The changing rural-urban divide in China’s megacities. Cities 2018, 81, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Cao, X.; Shi, D.; Wang, Y. The “one-city monopoly index”: Measurement and empirical analysis of China. Cities 2020, 96, 102434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Guo, N.; Gao, X.; Wu, F. How carbon emission reduction is going to affect urban resilience. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 372, 133737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B. Interregional supply chains of Chinese mineral resource requirements. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuka, H.; Zeng, D.-Z.; Zhao, L. Resource-based cities and the Dutch disease. Resour. Energy Econ. 2015, 40, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).