Evaluating the Sustainable Development of Rural Communities: A Case Study of the Mountainous Areas of Southwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Indicator System and Materials

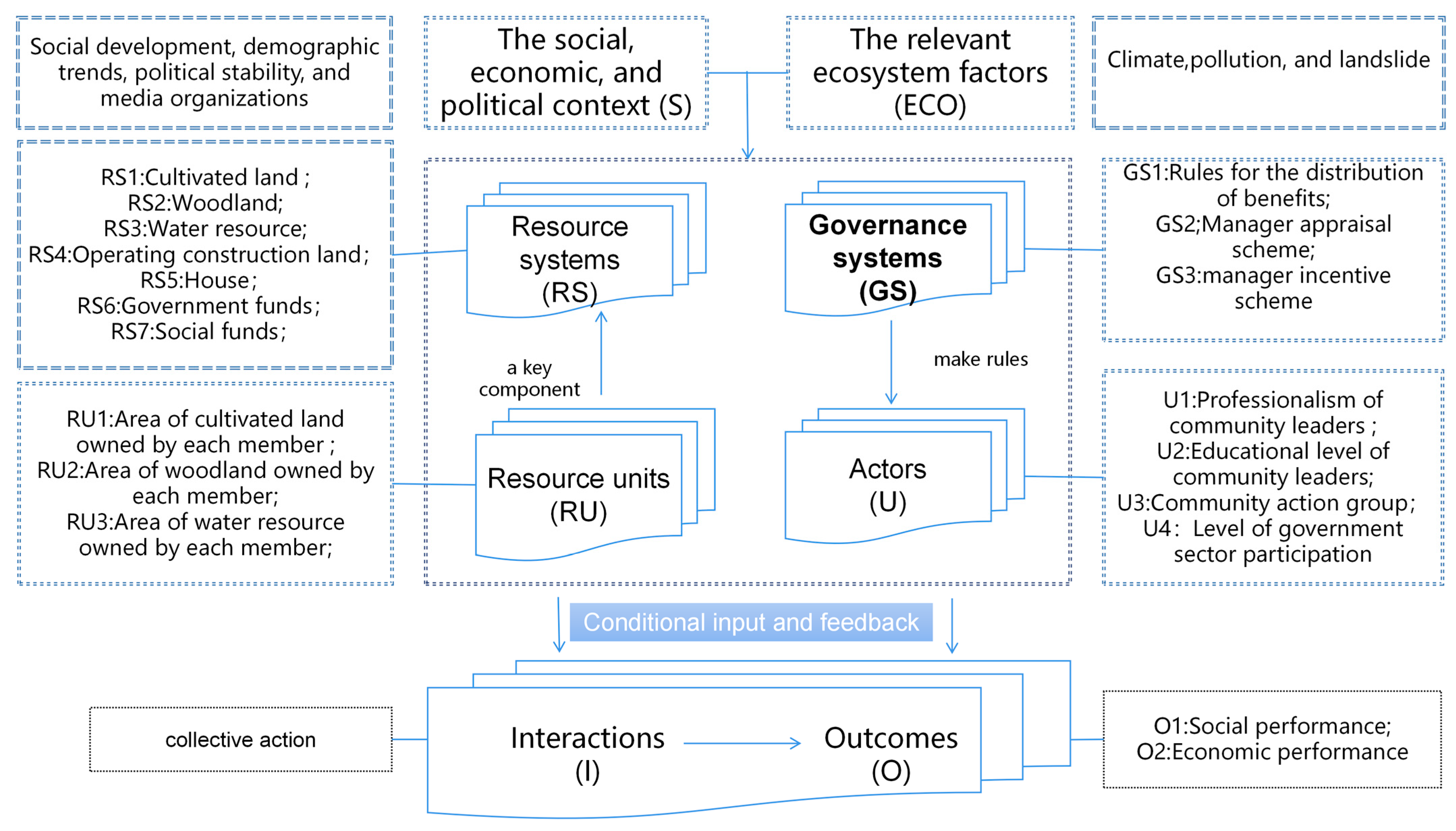

2.1. The Applicability of the SES Framework to Rural Sustainable Development

2.2. Indicators of Rural Sustainable Development with the SES Framework

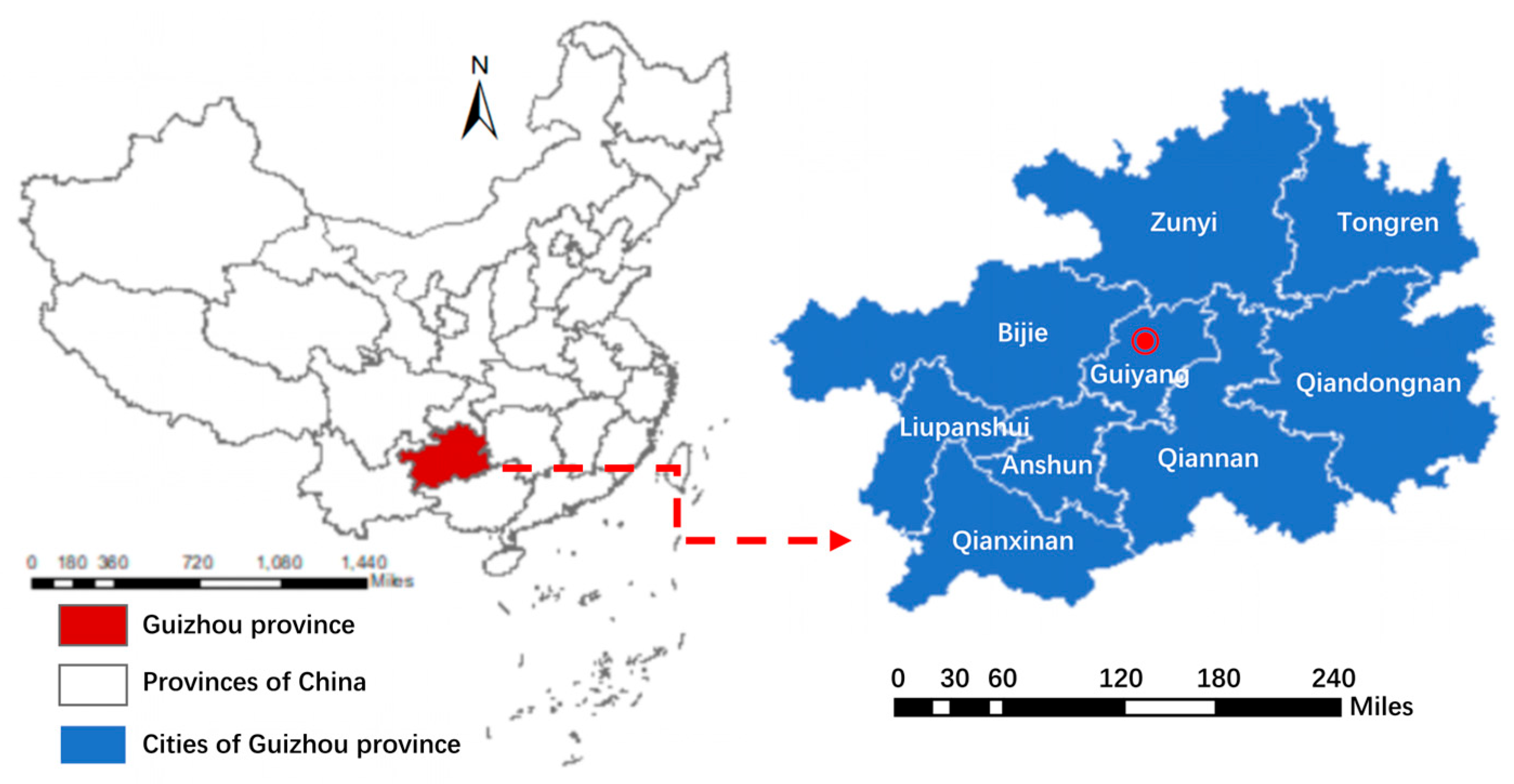

2.3. Research Area

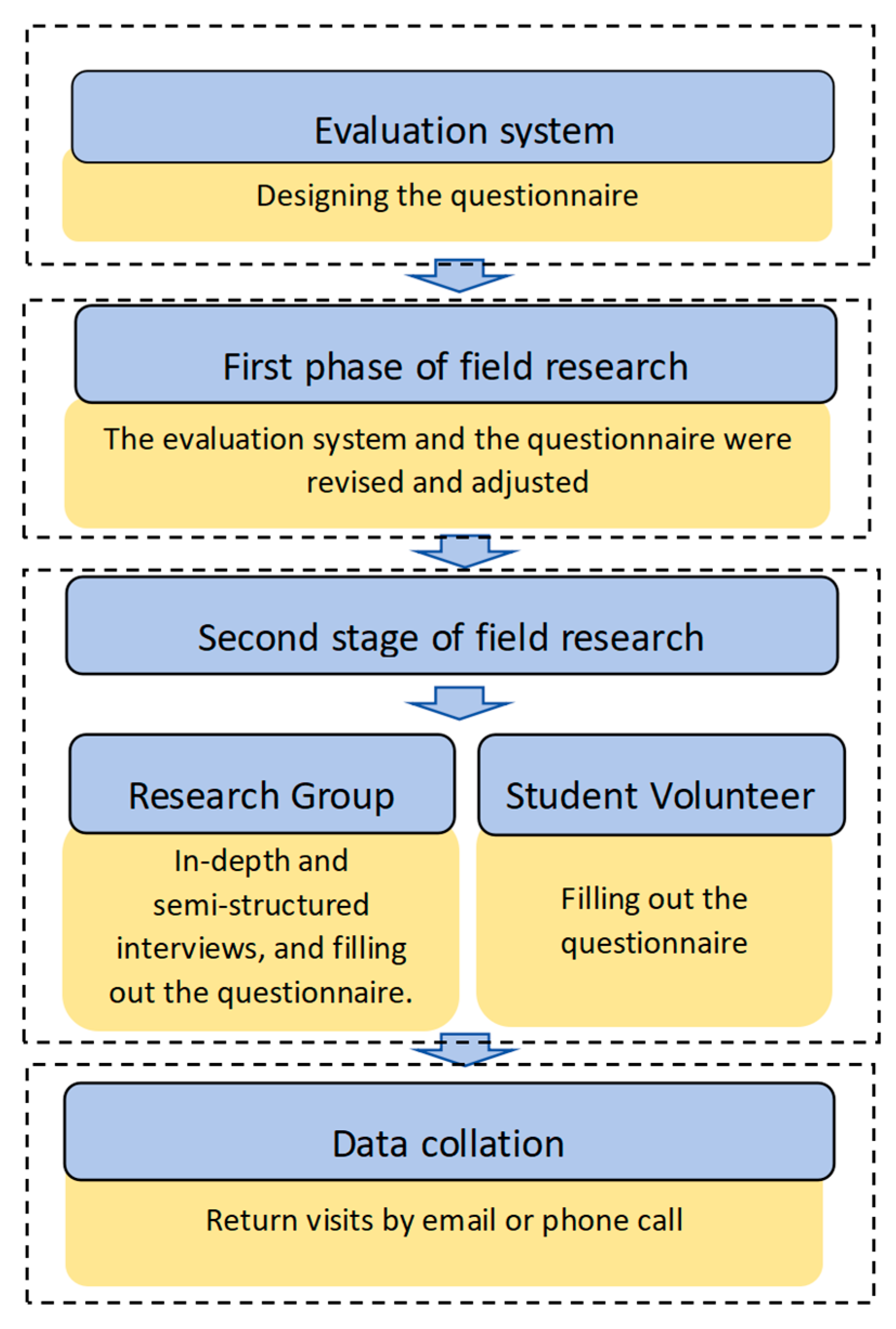

2.4. Data Collection

3. Research Methodology and Quantitative Models

3.1. Method for Calculating Indicator Weightings

3.2. Coupling Coordination Degree Model

3.3. Obstacle Degree Model

- (1)

- Determine the factor contribution degree. The factor contribution degree is a measure of the degree of influence of a specific indicator on the overall goal of sustainable development of rural communities. It is expressed by the weight of the indicator (wij), which is the weight of the indicators at all levels in the evaluation index system for the sustainable development of rural communities, calculated in the previous section.

- (2)

- Calculate the degree of deviation of indicators. Indicator deviation refers to the distance between each indicator and the ideal value. It is expressed by the difference between the standardized value of the single indicator and 100%, which can be calculated by , where Iij is the degree of deviation of the jth indicator of the ith region, and Zij is the standardized value of each indicator.

- (3)

- Finally, the degree of obstacle imposed by a single indicator on the overall level of sustainable development of rural communities is computed. The larger the degree of the obstacle, the more it impedes development. The obstacle degree is computed as follows:

4. Results

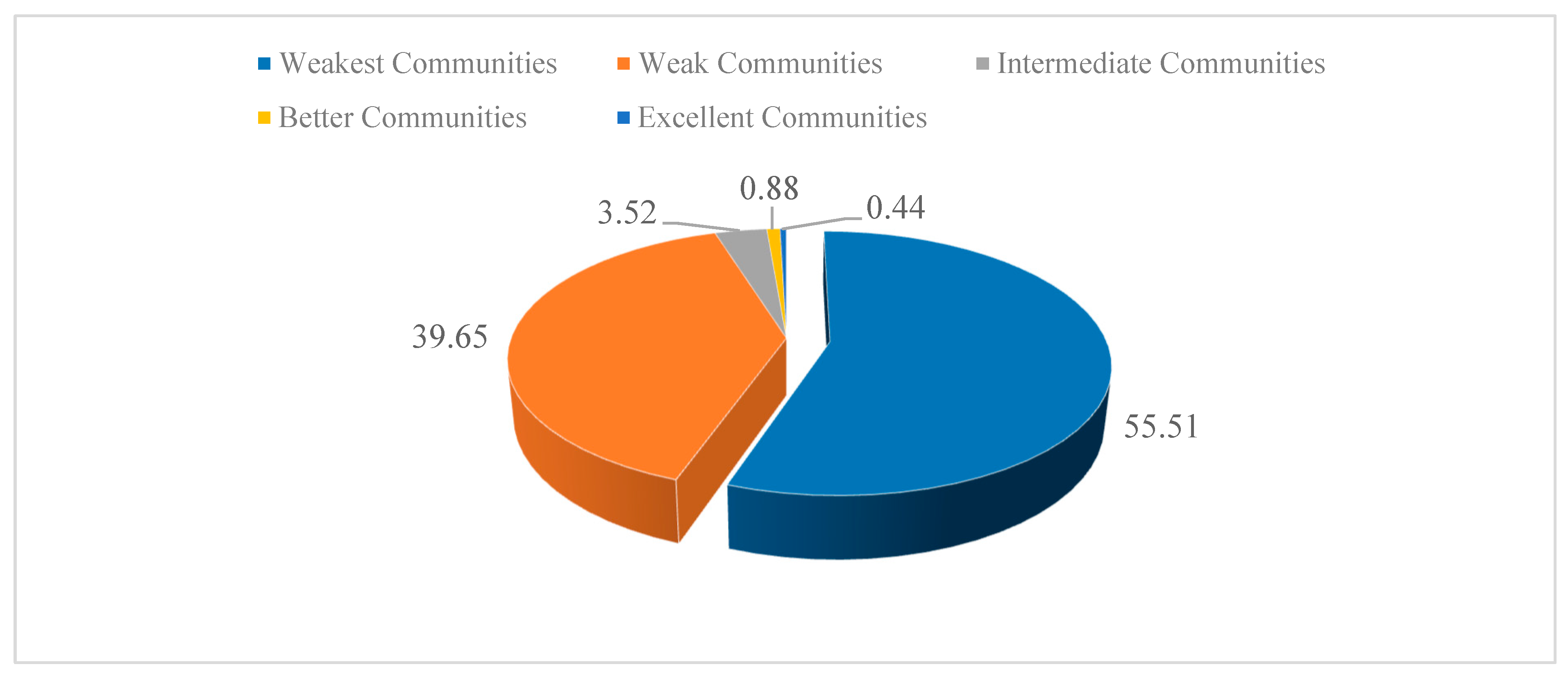

4.1. Level of Sustainable Development of Rural Communities in Guizhou Province, a Mountainous Area in Southwest China, in 2020

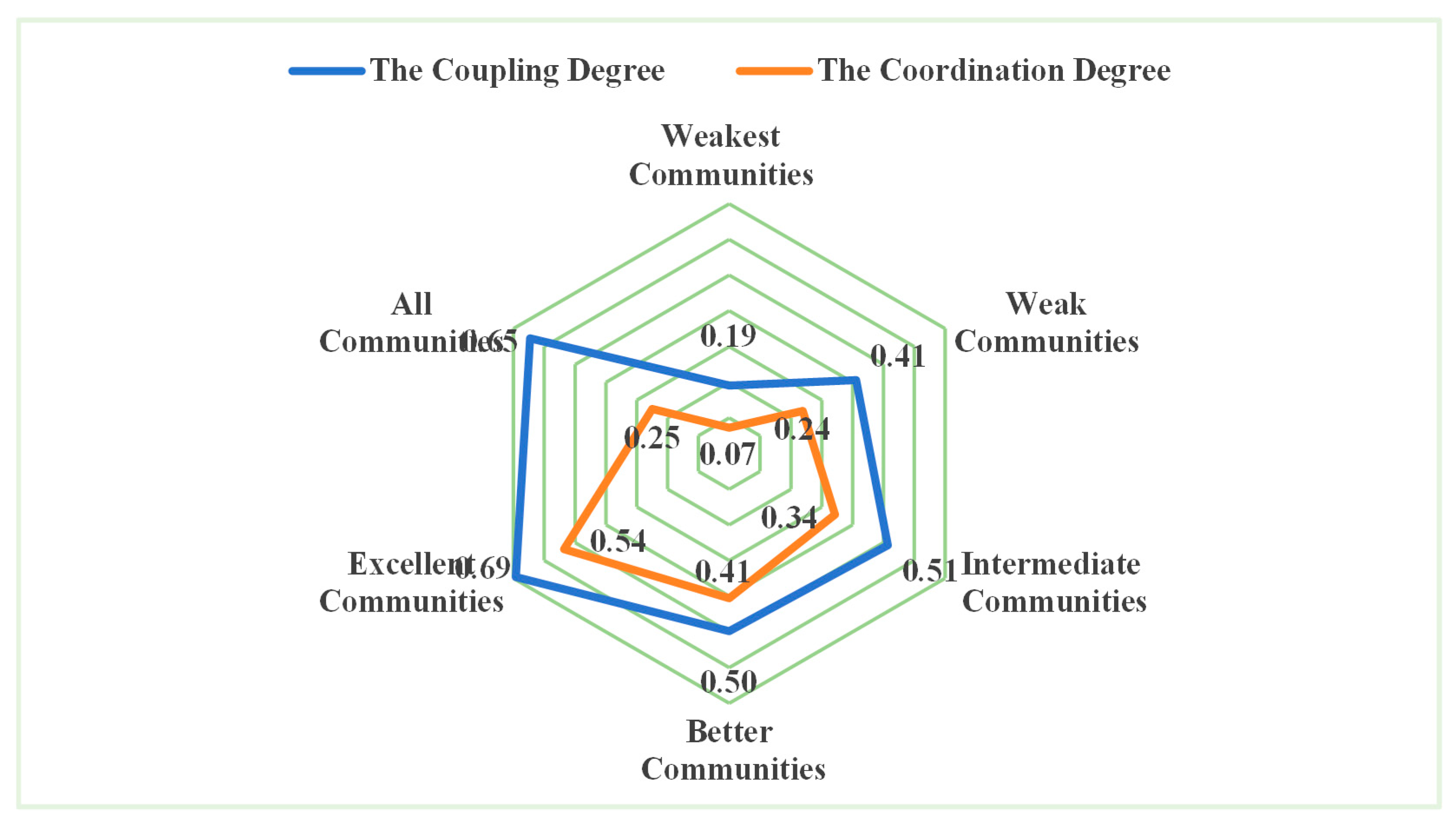

4.2. Coupling Coordination Degree Between Subsystems of Rural Communities in Guizhou Province, a Mountainous Area in Southwest China, in 2020

4.3. The Obstacle Factors of Sustainable Development of Rural Communities in Guizhou Province, a Mountainous Area in Southwest China, in 2020

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Villa, F.; McLeod, H. Environmental Vulnerability Indicators for Environmental Planning and Decision-Making: Guidelines and Applications. Environ. Manag. 2002, 29, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beroya-Eitner, M.A. Ecological vulnerability indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Guo, W.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Ji, X.; Chao, M. Integrated assessment and prediction of ecological security in typical ecologically fragile areas. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 1963, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willcock, S.; Cooper, G.S.; Addy, J.W.; Dearing, J.A. The earlier collapse of Anthropocene ecosystems was driven by multiple faster and noisier drivers. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsman, D.K. Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B. Poverty, development, and environment. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2010, 15, 635–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrouet, L.; Machado, J.; Villegas-Palacio, C. Vulnerability of socio—Ecological systems: A conceptual Framework. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 84, 632–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Chen, Y.; Tian, M.; Lv, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, S. The Ecological Vulnerability Evaluation in the Southwestern Mountain Region of China Based on GIS and AHP Method. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2010, 2, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeleke, G.; Teshome, M.; Ayele, L. Farmers’ livelihood vulnerability to climate-related risks in the North Wello Zone, northern Ethiopia. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 17, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, I.; Simane, B. Vulnerability analysis of smallholder farmers to climate variability and change: An agro-ecological system-based approach in the Fincha’a sub-basin of the upper Blue Nile Basin of Ethiopia. Ecol. Process. 2019, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y. The Impact of Village Cadres’ Public Service Motivation on the Effectiveness of Rural Living Environment Governance: An Empirical Study of 118 Chinese Villages. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221079795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Shigeto, S.; Kubota, H.; Johnson, B.A.; Yamagata, Y. Spatial exploration of rural capital contributing to quality of life and urban-to-rural migration decisions: A case study of Hokuto City, Japan. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Tan, S.H.; Zhou, H.; Zeng, W. An approach to assess spatio-temporal heterogeneity of rural ecosystem health: A case study in Chongqing mountainous area, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, B.; Hopwood, B.; O’Brien, G. Environment, economy and society: Fitting them together into sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, F.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; He, J. An integrated framework for measuring sustainable rural development towards the sdgs. Land Use Policy 2024, 147, 107339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Milojevic, M.; Gura, D.; Hens, L. Development of methodology for evaluating sustainable rural development. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 21237–21257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Linlin, X.; Lianlian, X.; Yongkang, Z. Rural multifunctionality evaluation and interaction relationships: A case study of Henan province. J. Resour. Ecol. 2025, 16, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Li, S. Evolution pattern and mechanism of rural areal functions in Xi’an metropolitan area, China. Habitat Int. 2024, 148, 103088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazhu, W.; Xuejun, D.; Lei, W.; Lingqing, W. Evolution of rural multifunction and its natural and socioeconomic factors in coastal China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 1791–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eversole, R.; Campbell, P. Building the plane in the air: Articulating neo-endogenous rural development from the ground up. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 101, 103043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.M.; Nunn, P.D.; Beazley, H. Uncovering multilayered vulnerability and resilience in rural villages in the Pacific: A case study of Ono Island, Fiji. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magarey, R.D.; Chappell, T.M. A model that integrates stocks and flows of multi-capital for understanding and assessing the sustainability of social–ecological systems. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 20, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partelow, S.; Boda, C.S. A modified diagnostic social-ecological system framework for lobster fisheries: Case implementation and sustainability assessment in Southern California. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 114, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Riomalo, J.F.; Koessler, A.; Engel, S. Fostering collective action through participation in natural resource and environmental management: An integrative and interpretative narrative review using the IAD, NAS and SES frameworks. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 331, 117184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialozyt, R.B.; Roß-Nickoll, M.; Ottermanns, R.; Jetzkowitz, J. The different ways to operationalise the social in applied models and simulations of sustainability science: A contribution for the enhancement of good modelling practices. Ecol. Model. 2025, 500, 110952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.; Sun, Y.; Tang, J.; Luo, Z.; Lu, J.; Liu, X. Modeling the interaction of internal and external systems of rural settlements: The case of Guangdong, China. Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lu, S.; Xiong, K.; Zhao, R. Coupling analysis on ecological environment fragility and poverty in South China Karst. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. Understanding rural system with a social-ecological framework: Evaluating sustainability of rural evolution in Jiangsu province, South China. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 86, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillán-Carvantes, P.; Tauro, A.; Balvanera, P.; Requena-Mullor, J.M.; Castro, A.J.; Quintas-Soriano, C.; Martín-López, B. Impact of land transformation, management, and governance on subjective well-being across social–ecological systems. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 20, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Institutional Rational Choice: An Assessment of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zuluaga-Guerra, P.A.; Martínez-Fernández, J.; Esteve-Selma, M.Á.; Dell’Angelo, J. A socio-ecological model of the Segura River basin, Spain. Ecol. Model. 2023, 478, 110284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, G.D.l.M.d.l.; Sánchez-Nupan, L.O.; Castro-Torres, B.; Galicia, L. Sustainable Community Forest Management in Mexico: An Integrated Model of Three Socio-ecological Frameworks. Environ. Manag. 2021, 68, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partelow, S. A review of the social-ecological systems framework: Applications, methods, modifications, and challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, V.H.; Lam, W.F.; Williams, J.M. Building robustness for rural revitalization: A social-ecological system perspective. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 101, 103042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Ling, G.H. Influencing factors and mechanisms on self-governed rural public open space quality: A conceptual social-ecological system (SES) framework. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Tu, S.; Ge, D.; Li, T.; Liu, Y. The allocation and management of critical resources in rural China under restructuring: Problems and prospects. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K.; Loreau, M. A model of Sustainable Development Goals: Challenges and opportunities in promoting human well-being and environmental sustainability. Ecol. Model. 2023, 475, 110164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, W.; Liu, Y. Land consolidation for rural sustainability in China: Practical reflections and policy implications. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, S. Rural vitalization in China: A perspective of land consolidation. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, H.; Cui, W. Community-based rural residential land consolidation and allocation can help to revitalize hollowed villages in traditional agricultural areas of China: Evidence from Dancheng County, Henan Province. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, M.; Xu, H. How do Collective Operating Construction Land (COCL) Transactions affect rural residents’ property income? Evidence from rural Deqing County, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 113, 105897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Huang, J.; Dong, J. Assessment of rural ecosystem health and type classification in Jiangsu province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 1218–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolo, V.; Roces-Díaz, J.V.; Torralba, M.; Kay, S.; Fagerholm, N.; Aviron, S.; Burgess, P.J.; Crous-Duran, J.; Ferreiro-Domínguez, N.; Graves, A.; et al. Mixtures of forest and agroforestry alleviate trade-offs between ecosystem services in European rural landscapes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 50, 101318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czudec, A.; Zając, D. Economic Effects of Public Investment Activity in Rural Municipalities of Eastern Poland. Econ. Reg. 2021, 17, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baland, J.-M.; Platteau, J.-P. The ambiguous impact of inequality on local resource management. World Dev. 1999, 27, 773–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, C.B.; Andersen, L.B.; Bøllingtoft, A.; Eriksen, T.L. Can Leadership Training Improve Organizational Effectiveness? Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment on Transformational and Transactional Leadership. Public Adm. Rev. 2021, 82, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Long, H.; Tang, Y.; Deng, W.; Chen, K.; Zheng, Y. The impact of land consolidation on rural vitalization at the village level: A case study of a Chinese village. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 86, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparcia, J.; Escribano, J.L.; Serrano, J.J. From development to power relations and territorial governance: Increasing the leadership role of LEADER Local Action Groups in Spain. J. Rural. Stud. 2015, 42, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y. Bottom-up initiatives and revival in the face of rural decline: Case studies from China and Sweden. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, M.; de Fátima Ferreiro, M.; Stryjakiewicz, T. Local Development Initiatives as Promoters of Social Innovation: Evidence from Two European Rural Regions. Quaest. Geogr. 2020, 39, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Working Group of the International Institute of Administrative Sciences. Governance: A Working Definition. 1996. Available online: www.gdrc.org/u-gov/work-def.html (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Bowles, S.; Gintis, H. Social Capital and Community Governance. Econ. J. 2002, 112, F419–F436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.E.; Fernández, J.C. Collective Property Ownership and Social Citizenship: Recent Trends in Urban Latin America. Soc. Policy Soc. 2019, 19, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckett, J.; Wang, G. Why do Authoritarian Regimes Provide Public Goods? Policy Communities, External Shocks, and Ideas in China’s Rural Social Policy Making. Eur.-Asia Stud. 2017, 69, 109–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poos, W.H. The Local Governance of Social Security in Rural Surkhondarya, Uzbekistan: Post-Soviet Community, State and Social Order; University of Bonn: Bonn, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Rural land system reforms in China: History, issues, measures and prospects. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, X. Three rightsownership separation: China’s proposed rural land rightsownership reform and four types of local trials. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, X.; Bao, H.X.; Xiang, J.; Zhong, T.; Zhigang, C.; Zhou, Y. Rural Land Rightsownership Reform and Agro-Environmental Sustainability: Empirical Evidence from China. Energy Ejournal 2017, 74, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ravenscroft, N. Collective action in China’s recent collective forestry property ownership reform. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Murphy, K.J. Performance Pay and Top-Management Incentives. J. Political Econ. 1990, 98, 225–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.A. Compensation, Incentives, and the Duality of Risk Aversion and Riskiness. J. Financ. 2004, 59, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ederer, F.; Manso, G. Is Pay-for-Performance Detrimental to Innovation? Behav. Exp. Econ. 2009, 59, 1496–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongtao, T.; Xiaoxing, Y.; Xiaojuan, Y. Does Equity Incentive Enhance Firm Innovation?—Empirical Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Res. Dev. Manag. 2016, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Peng, L.; Liu, S.; Xu, D.; Xue, P. Factors influencing the efficiency of rural public goods investments in mountainous areas of China—Based on micro panel data from three periods. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb-McCoy, C.; Bryan, J. Advocacy and empowerment in parent consultation: Implications for theory and practice. J. Couns. Dev. 2010, 88, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploeg, J.V.; Long, A. Born from Within: Practice and Perspectives of Endogenous Rural Development; Van Gorcum: Drenthe, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sara, I.M.; Jayawarsa, A.A.; Saputra, K.A. Rural Assets Administration and Establishment of Village-Owned Enterprises for the Enhancement of Rural Economy. J. Bina Praja 2021, 13, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockington, D.; Howland, O.; Loiske, V.M.; Mnzava, M.; Noe, C. Economic growth, rural assets and prosperity: Exploring the implications of a 20-year record of asset growth in Tanzania. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2018, 56, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouna, A.; Michler, J.D.; Lokossou, J.C. Contract farming and rural transformation: Evidence from a field experiment in Benin. J. Dev. Econ. 2019, 151, 102626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakwani, N.; Wang, X.; Xue, N.; Zhan, P. Growth and Common Prosperity in China. China World Econ. 2022, 30, 28–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Hou, R. Human causes of soil loss in rural karst environments: A case study of Guizhou, China. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, S.; Zhou, Q.; Zhuo, Y.; Wen, X.; Guo, Z. Evaluating urban ecological civilization and its obstacle factors based on an integrated model of PSR-EVW-TOPSIS: A case study of 13 cities in Jiangsu Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, W.; Jin, L. How eco-compensation contributes to poverty reduction: A perspective from different income groups of rural households in Guizhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Wei, Y.; Cai, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, F. Rural nonfarm sector and rural residents’ income research in China. An empirical study on the township and village enterprises after ownership reform (2000–2013). J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 82, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Sheng, J. New evaluation system for the modernization level of a province or a city based on an improved entropy method. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 192, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ji, G.; Tian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z. Environmental vulnerability assessment for mainland China based on the entropy method. Ecological Indicators 2018, 91, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihong, Y. A study on the forecast and regulation of coordinated development of urban environment and economy in Guangzhou. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 1995, 5, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fan, Z.; Feng, W.; Yuxin, C.; Keyu, Q. Coupling coordination degree, spatial analysis, and driving factor between socioeconomic and eco-environment in northern China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 135, 108555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Du, M.; Yan, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Kou, Y. Coupling coordination degree analysis and spatiotemporal heterogeneity between water ecosystem service value and water system in Yellow River Basin cities. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 79, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, M.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, W. Evaluation of ecological city and analysis of obstacle factors under the background of high-quality development: Taking cities in the Yellow River Basin as examples. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.; Chen, Y.; Kao, Y.; Wu, S. Obstacle factors of corporate social responsibility implementation: Empirical evidence from listed companies in Taiwan. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2014, 28, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Qi, X.; Fu, Z. Karst landscapes of China: Patterns, ecosystem processes and services. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 2743–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, J.; Jiang, S.; Wu, C.; Ning, S. Spatiotemporal characteristics and obstacle factors identification of agricultural drought disaster risk: A case study across Anhui Province, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 289, 108554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bao, W.; Liu, Y. Coupling coordination analysis of rural production-living-ecological space in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhilong, W.; Tian, Z.; Jin, H. Sustainable Livelihood Security in the Poyang Lake Eco-economic Zone: Ecologically Secure, Economically Efficient or Socially Equitable? J. Resour. Ecol. 2022, 13, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurui, L.; Yansui, L.; Hualou, L.; Jieyong, W. Local responses to macro development policies and their effects on the rural system in China’s mountainous regions: The case of Shuanghe Village in Sichuan Province. J. Mt. Sci. 2013, 10, 588–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Li, Y. Beyond government-led or community-based: Exploring the governance structure and operating models for reconstructing China’s hollowed villages. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 93, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Introduction to land use and rural sustainability in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Long, H. Rural restructuring in China: Theory, approaches, and research prospects. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery, B.; Dagevos, J.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Vodden, K. Storytelling for sustainable development in rural communities: An alternative approach. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Wang, L.; Hu, Z.; Lev, B.; Gang, J.; Lan, H. Do geologic hazards affect the sustainability of rural development? Evidence from rural areas in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Exploring the outflow of population from poor areas and its main influencing factors. Habitat Int. 2020, 99, 102161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Araral, E.; Chen, C. The Effects of Migration on Collective Action in the Commons: Evidence from Rural China. World Dev. 2016, 88, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Jiang, G.; Zhou, T.; Qu, Y. Do decaying rural communities have an incentive to maintain large-scale farming? A comparative analysis of farming systems for peri-urban agriculture in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 397, 136590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Song, W. Spatiotemporal variations in cropland abandonment in the Guizhou–Guangxi karst mountain area, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time In Economic Sociology; Blackwell Publishers: Malden, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Emran, M.S.; Shilpi, F. The Extent of the Market and Stages of Agricultural Specialization. Can. J. Econ. 2008, 45, 1125–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Fan, J.; Shen, M.; Song, M. Sensitivity of livelihood strategy to livelihood capital in mountain areas: Empirical analysis based on different settlements in the upper reaches of the Minjiang River, China. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 38, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.J.; Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wan, L.; Yang, S.; Liu, G.; Su, X. The Role of Livelihood Assets in Livelihood Strategy Choice From the Perspective of Macrofungal Conservation in Nature Reserves on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 44, e02478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Guanghui, J.; Wenqiu, M.; Guangyong, L.; Yanbo, Q.; Yingying, T.; Qing-lei, Z.; Yaya, T. Dying villages to prosperous villages: A perspective from revitalization of idle rural Resid. land (IRRL). J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 84, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Bennett, S.J.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y. Agricultural practices and sustainable livelihoods: Rural transformation within the Loess Plateau, China. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 41, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, F.; Jin, J.; He, R.; Wan, X.; Ning, J. Influence of livelihood capital on adaptation strategies: Evidence from rural households in Wushen Banner, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.; Blas-Morato, R.; Rengifo-Gallego, J. The Dehesas of Extremadura, Spain: A Potential for Socio-economic Development Based on Agritourism Activities. Forests 2019, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, S.F.P.D.; Chin, W.L. The role of farm-to-table activities in agritourism towards sustainable development. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Ji, X.; Cheng, C.; Liao, S.; Obuobi, B.; Zhang, Y. Digital economy empowers sustainable agriculture: Implications for farmers’ adoption of ecological agricultural technologies. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campenhout, B.V.; Spielman, D.J.; Lecoutere, E. Information and communication technologies to provide agricultural advice to smallholder farmers: Experimental evidence from Uganda. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 103, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Layer | Second Layer | Third Layer | Index Content | Attribute | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable development of rural communities | Resource system (RS)C1 | Cultivated land C11 | Area of cultivated land owned by each member, including paddy land, watered land, dry land, etc. | + | 0.9 |

| Woodland C12 | Area of woodland owned by each member, including forests, mountains, wasteland, orchards, etc. | + | 1.66 | ||

| Water resource C13 | Area of water resources owned by each member, including lakes, rivers, etc. | + | 7.85 | ||

| Operating construction land C14 | Mainly a community-owned collective operating on construction land | + | 7.6 | ||

| House C15 | Unused community primary schools, unused residences, etc. | + | 11.88 | ||

| Government funds C16 | Total funds spent by the government on community development this year | + | 8.98 | ||

| Social funds C17 | Total funds spent by enterprises, individuals, and social organizations on community development in the year | + | 6.98 | ||

| Actors (A) C2 | Professionalism of community leaders C21 | Number of professional trainings and learning received by community leaders during the year | + | 2.14 | |

| Educational level of community leaders C22 | Proportion of community leaders and managers with a high school diploma or higher level of education | + | 0.62 | ||

| Community action group C23 | Whether community action groups are formed (1 = yes, 0 = no) | + | 0.64 | ||

| Level of government sector participation C24 | Proportion of political party members in the community | + | 1.07 | ||

| Governance system (GS)C3 | Community leadership appraisals C31 | Whether the effectiveness of community development is included in the assessment of leaders and managers (1 = yes, 0 = no) | + | 3.06 | |

| Community leadership incentives C32 | Whether leadership compensation incentives are in place (1 = yes, 0 = no) | + | 5.82 | ||

| Benefit-sharing mechanism for members C33 | Whether a mechanism for distributing the benefits of membership is present (1 = yes, 0 = no) | + | 2.77 | ||

| Social outcomes (O1)C4 | Public utilities development C41 | Expenditure on public utilities such as environmental protection, infrastructure, and education during the year | + | 6.92 | |

| Democratic participation C42 | Number of meetings related to community development attended by members during the year | + | 2.05 | ||

| Economic outcomes (O2)C5 | Capital growth C51 | Total community assets for the year | + | 7.73 | |

| Income growth C52 | Combined value of operating and investment incomes for the year | + | 5.84 | ||

| Profitability C53 | Operating income is the amount of income after deducting all operating expenses for the year. | + | 6.18 | ||

| Bonus sharing C54 | A bonus for each member for the three-year cumulative value | + | 9.31 |

| Indicators | Average Value | Maximum | Minimum | Development Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11 | 0.2914 | 0.9018 | 0.0000 | 0.9018 |

| C12 | 0.3905 | 1.6604 | 0.0000 | 1.6604 |

| C13 | 0.3690 | 7.8460 | 0.0000 | 7.8460 |

| C14 | 0.3920 | 7.6041 | 0.0000 | 7.6041 |

| C15 | 0.2246 | 11.8814 | 0.0000 | 11.8814 |

| C16 | 0.1456 | 8.9755 | 0.0000 | 8.9755 |

| C17 | 0.2080 | 6.9781 | 0.0000 | 6.9781 |

| C21 | 0.3168 | 2.1443 | 0.0000 | 2.1443 |

| C22 | 0.1891 | 0.6227 | 0.0000 | 0.6227 |

| C23 | 0.5447 | 0.6440 | 0.0000 | 0.6440 |

| C24 | 0.2610 | 1.0722 | 0.0000 | 1.0722 |

| C31 | 1.5504 | 3.0604 | 0.0000 | 3.0604 |

| C32 | 1.5382 | 5.8195 | 0.0000 | 5.8195 |

| C33 | 1.4648 | 2.7709 | 0.0000 | 2.7709 |

| C41 | 0.3679 | 6.9170 | 0.0000 | 6.9170 |

| C42 | 0.3850 | 2.0458 | 0.0000 | 2.0458 |

| C51 | 0.1470 | 7.7313 | 0.0000 | 7.7313 |

| C52 | 0.1988 | 5.8353 | 0.0000 | 5.8353 |

| C53 | 0.3942 | 6.1771 | 0.0000 | 6.1771 |

| C54 | 0.2707 | 9.3122 | 0.0000 | 9.3122 |

| C1 | 2.0212 | 18.4629 | 0.0010 | 18.4619 |

| C2 | 1.3115 | 3.6125 | 0.1672 | 3.4453 |

| C3 | 4.5534 | 11.6508 | 0.0000 | 11.6508 |

| C4 | 0.7529 | 8.0380 | 0.0000 | 8.0380 |

| C5 | 1.0106 | 21.4064 | 0.0000 | 21.4064 |

| Overall value | 9.6497 | 41.4657 | 0.5114 | 40.9543 |

| Overall Value | Categories |

|---|---|

| 0 ≤ T < 10 | Weakest Communities |

| 10 ≤ T < 20 | Weak Communities |

| 20 ≤ T < 30 | Intermediate Communities |

| 30 ≤ T < 40 | Better Communities |

| 40 ≤ T | Excellent Communities |

| Weakest Communities | Weak Communities | Intermediate Communities | Excellent Communities | All Communities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 1.08 | 0.68 |

| C12 | 1.38 | 1.43 | 1.68 | 1.84 | 1.41 |

| C13 | 8.06 | 8.53 | 8.13 | 13.4 | 8.30 |

| C14 | 7.76 | 8.22 | 8.51 | 12.61 | 8.02 |

| C15 | 12.73 | 13.28 | 12.43 | 13.41 | 12.94 |

| C16 | 9.88 | 9.81 | 9.34 | 9.50 | 9.83 |

| C17 | 7.41 | 7.69 | 7.22 | 7.96 | 7.52 |

| C21 | 2.03 | 2.02 | 2.05 | 2.04 | 2.03 |

| C22 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.48 |

| C23 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| C24 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 1.02 | 0.90 |

| C31 | 1.67 | 1.49 | 1.56 | 0.00 | 1.59 |

| C32 | 4.87 | 4.16 | 6.09 | 6.63 | 4.65 |

| C33 | 1.58 | 0.95 | 2.90 | 0.00 | 1.38 |

| C41 | 7.15 | 7.39 | 7.23 | 7.36 | 7.25 |

| C42 | 1.90 | 1.74 | 1.95 | 2.01 | 1.84 |

| C51 | 8.34 | 8.59 | 8.08 | 8.8 | 8.43 |

| C52 | 6.28 | 6.28 | 5.79 | 6.44 | 6.26 |

| C53 | 6.53 | 6.26 | 6.04 | 6.81 | 6.40 |

| C54 | 9.94 | 10.16 | 9.74 | 10.50 | 10.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, D.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Chandio, A.A. Evaluating the Sustainable Development of Rural Communities: A Case Study of the Mountainous Areas of Southwest China. Land 2025, 14, 2416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122416

Yang D, Li C, Wang S, Chandio AA. Evaluating the Sustainable Development of Rural Communities: A Case Study of the Mountainous Areas of Southwest China. Land. 2025; 14(12):2416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122416

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Dandan, Chengjiang Li, Shiyuan Wang, and Abbas Ali Chandio. 2025. "Evaluating the Sustainable Development of Rural Communities: A Case Study of the Mountainous Areas of Southwest China" Land 14, no. 12: 2416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122416

APA StyleYang, D., Li, C., Wang, S., & Chandio, A. A. (2025). Evaluating the Sustainable Development of Rural Communities: A Case Study of the Mountainous Areas of Southwest China. Land, 14(12), 2416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122416