Abstract

The transfer of agricultural land has significant effects on farmers’ livelihoods and welfare. This study aims to explore the utility and obstacles of rural land transfer. The research found that in the process of agricultural transformation in developing countries, rural land transfer played a positive role in improving farmers’ welfare. Rural land transfer enables land lessors to obtain physical rent or implicit rent, which increases household income or enhances relationships with relatives and neighbors, generating a positive impact on farmers’ welfare. Land transfer was a comprehensive decision-making of households based on the optimal allocation of factor resources such as land, labor, and capital. Risks associated with land transfer and social security arrangements after transferring land rights have emerged as prominent obstacles. These factors tend to induce anxiety among land-leasing households regarding the livelihood risks their families might face post-transfer, thus making them hesitant and reluctant to engage in land transfer due to lingering concerns over both immediate and long-term interests. The welfare-enhancing effects of land transfer on farmers vary significantly depending on the local rural governance context, household’s social status within the community, and relative importance of internal family opinions in decision-making processes. This study demonstrates that the allocation of production factors should be examined within the overarching framework of urban–rural integration and provides empirical evidence and theoretical insights for central and local governments to refine relevant policy documents.

1. Introduction

Land serves as a source of income, a livelihood guarantee, and a crucial asset for rural residents. To enhance people’s well-being, it is imperative to revitalize this category of resources. Land transfer was a prevalent practice worldwide. In many regions of European countries, the area of transferred land accounts for over 50% of total agricultural land. In Africa, land transfer has expanded access to land for tenants in less fertile areas, exerting a significant impact on equity, efficiency, and rural households’ welfare [1]. Governments across numerous countries have rolled out relevant policies to incentivize land transfer [2]. The central government of China had long prioritized the reform of the rural land system [3]. Nevertheless, the current proportion of rural land transfer in China remains relatively low. By the end of 2020, the land transfer rate in the country stood at 12.5% [4], accompanied by a notable prevalence of land abandonment [5]. Against this backdrop, a set of pressing questions awaits exploration: What exactly shapes rural households’ willingness to transfer land? How does land transfer affect farmers’ welfare? These critical issues demand in-depth investigation and empirical answers.

Land transfer refers to an institutional arrangement where the right to land management was transferred to other entities on the premise that the existing land contractual relationships remain unchanged. Previous land reform and privatization processes have resulted in the fragmentation of ownership and leasing structures, giving rise to widespread issues in land utilization such as decentralized cultivated land protection, haphazard spatial layout, and low efficiency of resource utilization [6]. Europe embarked on the exploration of land transfer at an early stage [7]. Relevant practices have been piloted in several Central and Eastern European countries, including Ukraine, and Western Europe, particularly the southwestern states of Germany [8]. While Europe has witnessed an upward trend in land transfer activities, the level of rural land transfer in China remains relatively low [9].

Since 1984, when the Chinese government put forward the policy of “encouraging capable rural households to gradually engage in large-scale land management”, China’s land transfer market has been expanding continuously. In 2002, the country enacted the Rural Land Contracting Law of the People’s Republic of China, which standardized land transfer practices in the form of legislation. In 2014, the Chinese government issued the Guidelines on Guiding the Orderly Circulation of Rural Land Management Rights and Developing Moderate-Scale Agricultural Operations, mandating vigorous efforts within a five-year timeframe to promote land transfer, develop moderate-scale agricultural operations, and complete the confirmation of land contracting and management rights. In 2020, the size of the migrant worker population reached 280 million, accounting for more than 50% of the total rural population. In stark contrast to this large-scale rural-to-urban labor migration, China’s land transfer rate stood at a mere 12.5%, indicating that the pace of land transfer had lagged far behind the rate of rural labor outflow.

Previous studies had explored the impacts of land transfer on farmers from diverse dimensions and perspectives. The reallocation of land from less competent producers to more capable ones contributes to an overall increase in agricultural productivity [10]. The redistribution of agricultural land resources from land-abundant but labor-scarce households to land-scarce but labor-abundant ones helps enhance social equity [11]. Most studies demonstrated that land transfer could increase rural households’ income [12] and improve their quality of life [13]. However, such improvements were primarily observed among the older generation, with negligible effects on younger farmers; conversely, some studies have indicated that land transfer could ameliorate the welfare of younger cohorts [14]. Additionally, the small-scale nature of agricultural production in China means that rural households might not directly benefit from large-scale farming practices [13].

A unified and objective understanding has not been reached regarding the impact of rural land transfer on farmers’ welfare. On the one hand, the land transfer market is characterized by segmentation [15], a phenomenon prevalent in both China and other countries. For instance, the land rental markets in Madagascar and Guatemala exhibit prominent informal attributes [16]. Data from the Philippines and Tanzania indicated that land allocation within traditional trust-based networks might exclude potential market participants. Meanwhile, evidence from Ethiopia suggested that kinship ties could affect the accessibility and extent of land access for tenants with limited landholdings [15]. On the other hand, land transfer cannot be fully equated with land consolidation, given that it does not involve the rearrangement of land rights. As a temporary measure, land transfer fails to guarantee that lessees could sign new rental agreements with the same lessors upon the expiration of existing contracts, which might lead to a regression toward land fragmentation [17,18]. Furthermore, some transferees evade contractual obligations by defaulting on or refusing to pay rent, or even absconding to shirk liabilities [19]. In addition, they arbitrarily alter land use, overapply chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and engage in unsustainable farming practices. In summary, the segmentation of the land transfer market and the inherent risks of land transfer practices might cause certain welfare losses to farmers.

The existing literature primarily examines the economic impact of land transfer on rural residents, with few studies exploring the link between agricultural land transfer and farmers’ welfare utility. There was a particular scarcity of welfare analysis focusing on landlords (the land-letting households). The significance of agricultural land transfer in boosting farmers’ welfare might have been underestimated, resulting in a paradoxical situation observed in many areas, where although “agricultural land transfer was highly beneficial, its adoption remains limited”. This study contributes significantly to the existing literature and theories in three ways. Firstly, this study analyzes the welfare effects of agricultural land transfer from the perspective of landowners and extends research on implicit rents in the process of land transfer from the dimension of improved interpersonal relationships. Secondly, it uncovers the reasons behind farmers’ reluctance to transfer land, adding to studies on the optimal allocation of rural resources. Thirdly, it offers new insights for governments in developing countries on how to stimulate micro-level incentives for land transfer, specifically by showcasing the benefits of land transfer to farmers through securing land rights and employment stability.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Mechanism Discussion

2.1. Theoretical Analysis

Against the backdrop of socioeconomic development and shifts in regional natural endowments, such as population growth in low-income countries and sub-Saharan Africa, as well as large-scale rural-to-urban migration [20], the allocation of rural land resources had assumed growing significance [8]. Empirical data from Poland, Germany, Japan, and Spain demonstrate that a country’s complex socioeconomic conditions, including demographic dynamics, might exert a notable impact on land utilization patterns [21]. Despite empirical evidence indicating that land transfer contributes to increasing farmers’ income, the level of land transfer in China remains relatively low. It appears that the rural land transfer market also exhibits a phenomenon analogous to the Easterlin Paradox of Happiness [22]. The development of medical care and elderly care security in rural areas started late and remains at a relatively low level, thus rendering land an important form of informal security for farmers. Moreover, this security function of land far outweighs its intrinsic value in agricultural production. Land provides farmers with employment opportunities, generates income, mitigates livelihood risks, and offers a safety net, hence fostering strong farmer dependence on land resources. Nevertheless, driven by the long-standing urban-centric development model and the siphon effect of urbanization, rural development has progressed at a relatively sluggish pace [23]. Even for individuals who have migrated from rural to urban areas, social, cultural, or institutional barriers might impede their access to public resources and services [24]. This had resulted in a scenario where some farmers were reluctant to transfer their land, out of concern that they would still struggle to access equivalent public services in urban areas after leasing out their landholdings.

According to the “Rational Peasant” theory, farmland transfer occurs as a result of rational farmers reallocating and adjusting their family’s factor resources (capital, land, labor) to maximize their household utility. As a significant shift in labor from the agricultural to the non-agricultural sector, the allocation and adjustment of factors between these two sectors have also gradually evolved. Farmers could be allocated their resources to the agricultural sector () and the non-agricultural sector (), . Agricultural operation income and non-agricultural income (including wage income, property income, rental income, etc.) were the returns from factor resources in the two sectors, which were, respectively, and . According to the measurement method for length and area proposed by Diening, assume the farmer’s utility function and the resource constraints of factors as

represents other factors that affect utility (including the enhancement of kinship and friendship ties formed through implicit rent). Cultural norms in China and many other regions tend to prioritize harmonious neighborly relations [25]. Traditional Chinese rural areas were characterized by a familiarity-based social structure, high levels of mutual interdependence, relatively inadequate coverage of formal institutions, deeply rooted traditional culture, and economic vulnerability. These attributes rendered social morality and other informal institutions not merely a set of value propositions, but an indispensable mechanism for social governance and a robust, socially binding force with strong practical constraints [26,27]. Neighborly social ties have assumed growing significance. In this context, land transfer might serve as an effective means of strengthening rural interpersonal relationships. When farmers lease their land to relatives, friends, or neighbors at a rent that is relatively low or zero, the difference between this rent and the market rent is defined as implicit rent, also known as favor-based rent. Although implicit rent does not increase household income, it does enhance household utility to some extent, . The greater abundance of factor resources a farmer household possesses, the higher the welfare utility of the farmer, . The relationship between the utility function and resource allocation could be expressed as

and represent the market prices of factors in the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors, and denotes the transfer-out of land factors. Farmland transfer refers to the scenario where farmers did not allocate the land managed by their households to the agricultural sector (agricultural production and operation), instead obtaining property income. It is the result of allocating factors to the non-agricultural sector (representing the household’s non-agricultural operation income). The relationship between the impact of land transfer-out on farmers’ utility and the allocation of factors to the non-agricultural sector is linearly correlated: . When the health status of children and parents is good, they can share their household chores or labor. This situation is represented as a relatively abundant endowment of factor resources, and thus there is greater utility and higher welfare utility. Allocating factors to the agricultural sector or non-agricultural sector was the result of rational farmers pursuing utility maximization based on the allocation of household factor resources. Regardless of whether income comes from the agricultural sector or a non-agricultural sector, the utility brought by income to farmers was consistent: . Income exhibits non-satiation for farmers, meaning that the higher of income, the better it is: .

In the equilibrium context, the utility that farmers obtain from allocating one unit to the agricultural sector was the same as for a non-agricultural sector. The impact of land transfer-out on household utility was negligible: . When the utility of allocating factors to the agricultural sector is higher, , land transfer-out would lead to a decrease in household utility. When the utility of allocating household factor resources to the non-agricultural sector is higher, land transfer-out will result in an increase in household utility: . Especially given the rapid increase in wage income , this explains the large-scale inter-sectoral transfer of labor. Meanwhile, under the combined pressure of the cost floor and price ceiling in agricultural production and operation, the returns from agricultural production and operation were relatively low, while the relative income from the non-agricultural sector was higher . Rational farmers tend to allocate their resources to the non-agricultural sector to maximize household income. In this context, agricultural operation income and non-agricultural income served as the relative prices of factor resources, and it can be derived from Equation (2) that , meaning that the income utility derived from factor resources allocated to the non-agricultural sector results in higher utility for farmers, and consequently higher welfare utility.

To examine the impact of land transfer-out on farmers’ utility, a Lagrangian function is constructed.

To solve the maximization problem under constraint conditions, , , , . These equations indicate that rational farmers face limited household factor resources, , which represents the marginal utility of factors. When the maximization condition is satisfied,

Under the optimal condition, when allocating factor resources to the agricultural sector to obtain agricultural operation income, the impact of non-agricultural operation income on the allocation of resources to the agricultural sector is zero. Similarly, when factor resources were allocated to the non-agricultural sector, the impact of agricultural operation income on the allocation of resources to the non-agricultural sector is zero: . It can be known by substituting into the equations that

The utility of a farmer’s household is a function of factors and marginal utility, , . The relationship between household utility and factor allocation can be expressed as

It can be known by substituting Equations (7) and (8) into Equation (3), that

where , household income is basically positive, , and . represents the utility change brought about by farmers’ choice of land transfer-out under the condition that the marginal utility is known, , under the condition of given factor resources, . This outlines the relationship between factor market prices and the allocation of factors to agricultural production and operation. It can be known from Equation (9) that , which means that the market prices of factor resources in the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors are more conducive to allocating factors to household agricultural production and operation. The impact of land transfer-out on household utility was negative, . The larger the scale of land transfer-out, the lower the farmers’ utility; the utility of land transfer-out was negatively correlated with non-agricultural income, . The utility of the household brought about by implicit rent was also negatively correlated , but positively correlated with agricultural operation income, . means that the market prices of factor resources in the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors were more conducive to allocating factors to the non-agricultural sector. In this context, the impact of land transfer-out on household utility was positive, ; the larger scale of land transfer-out, the higher the farmers’ utility, and the utility of land transfer-out was positively correlated with non-agricultural income, . The utility of the household brought about by implicit rent was also positively correlated, , and was negatively correlated with agricultural operation income, .

2.2. Mechanism Discussion

Although China’s rural land transfer market has been gradually improved, non-pecuniary benefits exert a significant impact on the extensive range of farmers’ activities; the transfer of rural land among relatives and neighbors is relatively common [28]. According to the data from China’s Fixed Observation Points, the proportion of rural land transfers without rent reaches 43%. Data from Canada indicates that the proportion of zero-rent arrangements stands at 3%, with a substantial share of rental units being offered at rates below the market value [29]. Relevant survey data also show that 88.48% of rural land transfers occur among relatives, neighbors, or ordinary farmers in the same village. Instances of rural land transfer where rent was not collected in accordance with market rules were widespread. Data from the 2016 Thousand-Village Survey indicate that 64.29% of households that transferred out their land did not collect rent at the market price. Informal land transfers among relatives and neighbors do not involve rent collection at the market price (manifested as “zero rent” or “low rent”); implicit rent (human relationship-based rent) was formed through other means, such as taking care of houses in the rural hometown or providing certain assistance to elderly parents.

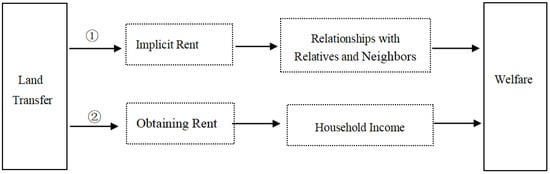

Based on the discussion in the theoretical section and the reality of rural land transfer in China, the impact of rural land transfer-out on farmers’ welfare mainly manifests in two aspects. On the one hand, transferring land enables farmers to obtain implicit rent, including promoting the harmony of relationships with relatives and neighbors, which increases their welfare (Path ① in Figure 1). On the other hand, transferring land and obtaining rent could increase household income, thereby further improving welfare (Path ② in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The impact of rural land transfer on farmers’ welfare.

The hypotheses of this paper were proposed as follows: Farmers’ decision to transfer land constitutes the outcome of maximizing household utility under the constraints of family resource endowments. The efficiency of other production factors could be taken into account.

3. Materials and Data

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

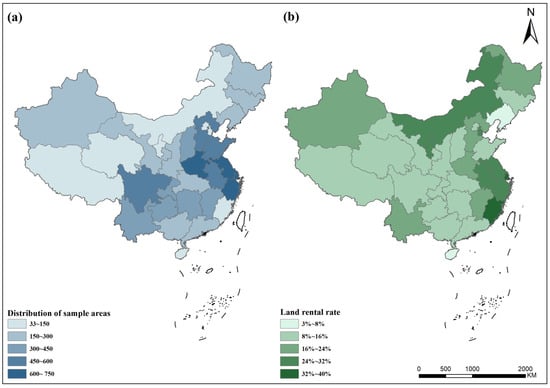

The data used in this study was derived from the 2016 Thousand-Village Survey conducted by Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, Shanghai, China. As a nationwide sampling survey, it covered the 31 provincial-level administrative regions in China, including all provinces of the Chinese mainland, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the Central Government, spanning the Eastern, Central, Western, and Northeastern regions (Figure 2). With its broad coverage, the survey was well-positioned to represent the development status of rural China. The survey employed two sub-units, individual farmers and rural villages, conducting a comprehensive investigation into issues related to rural areas, agriculture, and farmers. Launched in 2008, the survey has been conducted for 16 consecutive years, maintaining a consistent methodology annually. The sample was determined using a multi-stage systematic sampling method with probability proportional to size, ensuring a scientific sampling design. The data samples not only exhibit a high degree of national representativeness but also display distinct representative characteristics. Given that this study focuses on the relationship between rural land transfer and farmers’ welfare, it used data from the 2016 survey, which yielded a total of 14,133 valid household questionnaires. For the purpose of this study, samples were restricted to households with contracted arable land, resulting in a final sample of 9819 households. The version number of software used in the study was STATA19.

Figure 2.

(a) Distribution of sample areas, (b) land rental rate (Drawing Number: GS(2019)1822).

3.2. Variables

(1) Explained Variable: Subjective well-being not only reflects people’s satisfaction with their material living conditions but also embodies their contentment at the spiritual level, thus emerging as a comprehensive indicator for measuring residents’ overall welfare [30,31]. Some scholars had proposed that happiness data could be regarded as a proxy for utility. The criterion adopted by respondents to evaluate their own happiness was the ideal life that they aspire to; utility could be interpreted as the level of satisfaction that consumers derive from consumption bundles [32]. Based on this premise, certain scholars have argued that subjective well-being could be equated with utility, and residents’ self-rated happiness scores could serve as a proxy for their utility levels [33]. Essentially, an individual’s welfare utility encompasses multi-dimensional indicators spanning social, economic, and health domains, as well as both subjective and objective dimensions. Income, consumption, and wealth fall into the category of economic welfare indicators, while happiness and life satisfaction were classified as subjective welfare indicators [34]. The dependent variables in this paper are primarily individuals’ happiness and life satisfaction. Explained Variable 1: Subjective Well-Being. The measurement of this variable was based on respondents’ self-assessments of their household’s sense of well-being, using a 6-point scale: “Extremely unhappy”, “Unhappy”, “Neutral”, “Somewhat happy”, “Happy”, and “Extremely happy”. A higher numerical value signifies a greater level of subjective well-being, with 1 representing “Extremely unhappy” and 6 representing “Extremely happy.” Explained Variable 2: Life Satisfaction. This was measured using a 6-point scale, “Extremely dissatisfied”, “Dissatisfied”, “Neutral”, “Somewhat satisfied”, “Satisfied”, and “Extremely satisfied”. In line with the scaling logic, a higher numerical value signifies a higher level of life satisfaction, with 1 representing “Extremely dissatisfied” and 6 representing “Extremely satisfied”.

(2) Explanatory Variable: Based on the discussion in the theoretical section regarding the impact of agricultural land transfer on farmers’ welfare utility, the independent variable was defined as whether farmers have transferred out their land. To verify the mechanism by which agricultural land transfer affects farmers’ welfare, the implicit rent was measured by farmers’ personal popularity in the local area. Non-agricultural income and agricultural operation income were used to measure the returns of non-agricultural employment of labor factors and the returns from household engagement in agricultural production.

(3) The impact of agricultural land transfer on farmers’ welfare was constrained by factor resources; household-level factors were controlled, including the scale of contracted farmland owned by the household, household population size, and household assets. Due to the traditional rural family’s vertical responsibilities, encompassing both elderly family members (upward) and children (downward), the well-being of farmers was significantly influenced by their parents and children. This study accounts for the health status of farmers’ parents and children within their households. Furthermore, the economic, social, and cultural environments of a region directly influence individuals’ subjective perceptions, and factors such as rural harmony, government efficiency, and the provision of public goods also influence farmers’ welfare. Accordingly, this study incorporates farmers’ satisfaction with rural governments as a control variable. Additionally, the study accounts for land endowment factors (including topography and geomorphology), as well as transportation accessibility (such as the distance to the nearest highway).

3.3. Method

Based on the discussion of the theoretical section regarding farmland transfer and the improvement of farmers’ welfare, the empirical test was conducted using the 2016 Thousand-Village Survey data from Shanghai University of Finance and Economics. The explained variable represented the farmers’ subjective well-being and life satisfaction, measured as discrete variables with a 6-point scale (ranging from 1 to 6), serving as the core variables of interest. Given their ordinal discrete nature, an ordered logit regression is employed for the empirical model.

Among these variables, denotes farmland transfer-out; represents farmers’ neighborhood relations; stands for household income; denotes the controlled household-level factors; represents regional-level factors; , , and are the coefficients to be estimated; and is the standard error.

3.4. Descriptive Statistics

The survey data aligns with the phenomena we have observed; as living standards have improved, people have met “basic needs of food and clothing”, and achieved “a moderately prosperous life” and develop further in terms of “enhancing the quality of life”. Consequently, farmers’ subjective well-being and life satisfaction have significantly increased. The survey data (Table 1) indicate that farmers’ perceived subjective well-being was primarily concentrated between “somewhat happy” and “happy”, while their life satisfaction was mainly centered between “somewhat satisfied” and “satisfied”. This suggested that there was considerable potential for advancing common prosperity in rural areas. In farmers’ households, non-agricultural income has already far exceeded agricultural operating income (Table 1), which was consistent with data from the China Statistical Yearbook. Since 2013, the proportion of farmers’ wage income in rural China has surpassed household operating income. However, only 16% of households have transferred out their farmland. This indicates that although agricultural operating income was no longer the primary source of household income for most families, farmers’ willingness to transfer out their farmland remains relatively low.

Table 1.

Descriptive information of variables.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Baseline Results

Households that transfer out their farmland tend to have higher welfare utility (Table 2). The transfer of land had a significantly positive impact on happiness and life satisfaction, meaning that rural land transfer promotes both outcomes, consistent with the discussions in the theoretical section. Rural households’ decision to transfer land is a result of family factor resource allocation; land transfer could, to a certain extent, increase non-agricultural household income, thereby accumulating family wealth and further enhancing farmers’ welfare utility, improving their happiness and life satisfaction. Land transfer has also been recognized in tenant-operated land rental markets as a crucial means to boost agricultural productivity, enhance household welfare, and achieve green and sustainable agricultural development [29]. Even when farmers did not receive rental income, such as by transferring land to relatives and friends at a low price or for free, this practice strengthens kinship and neighborhood ties, which increases household utility and improves farmers’ welfare. For instance, low-rent and zero-rent arrangements were prevalent in land transfer markets such as those in tenancy systems and in North America [27,32]. Non-agricultural income exerts a significantly positive effect on happiness and life satisfaction, while agricultural operating income has no significant impact. The prices of resource allocation in the non-agricultural and agricultural sectors, non-agricultural income, and agricultural operating income directly influence the inter-sectoral allocation of family resources.

Table 2.

Empirical results of baseline models.

The greater the abundance of household factor resources, the higher the welfare utility. Empirical results suggest that the size of a household’s population and its wealth have a significantly positive effect on subjective well-being and life satisfaction. A larger household population and greater wealth correspond to better subjective well-being and higher life satisfaction among farmers. Influenced by the traditional belief that “more children bring more blessings”, farmers often prefer larger families. A larger household population was frequently associated with higher levels of subjective well-being. With the progression of the social division of labor and marketization, households with more wealth gain access to additional resources for exchange. Household-contracted cultivated land, as part of household factor resources, initially has a positive impact on household happiness and satisfaction. This effect becomes insignificant once village-level factors and income structure variables are taken into account. The underlying reason for this is the shift in the income structure of rural households; the primary source of household income has changed significantly, altering the role of land for farmers. Cultivated land is no longer the core livelihood asset of rural households. The health status of children and parents has a significantly positive impact on household subjective well-being and life satisfaction. For farmers, parents and children typically represent their “upward” and “downward” responsibilities; the better health of these family members directly translates to higher subjective well-being and life satisfaction.

Villages were critical factors influencing farmers’ welfare. The empirical results indicate that social harmony has a significantly positive effect on subjective well-being and life satisfaction. Rural residents’ daily lives were primarily confined within the village domain, and village conditions directly shape their living status and subjective perceptions. Social harmony often reflects interpersonal relationships within the village; a higher level of social harmony corresponds to greater happiness and higher life satisfaction among farmers. Additionally, farmers’ evaluation of township governments has a significantly positive effect on their subjective well-being and life satisfaction. Farmers tend to prefer living in an ecosystem characterized by harmonious government–resident relationships.

4.2. Path Analysis

Why does the phenomenon of “the highly beneficial farmland transfer, the limited transfer scale” exist? As non-agricultural industries develop, the relative returns from agricultural production have become relatively low. Wage income has replaced agricultural operation income as the primary source of household income, and for most rural residents, land is no longer a vital asset. However, in situations where transferring land could significantly improve farmers’ welfare, why were they still hesitant to transfer the management rights of their land? This hesitation might be related to the stability of farmers’ livelihoods, particularly of their non-agricultural employment [35]. This section examines the impact of farmland transfer on farmers’ welfare by analyzing two key dimensions. Firstly, whether individual laborers return to rural areas due to urban-related factors (such as the instability of urban jobs, excessive restrictions on migrant workers in cities, and urban living conditions), and secondly, the level of individual laborers’ skills.

The inadequacy of social security for migrant workers in urban areas has diminished the role of farmland transfer in promoting farmers’ welfare. Empirical results (Table 3) indicate that the positive impact of farmland transfer on farmers’ sense of subjective well-being and life satisfaction becomes insignificant in the sample of laborers who returned to rural areas due to urban-related factors. This suggested that insufficient social security for migrant workers in urban areas might weaken the welfare-promoting effect of farmland transfer. Urban social security, encompassing job stability, restrictive measures for migrant workers, and living conditions, fails to benefit the non-agricultural employment group. This situation has tended to leave farmers feeling insecure and raises concerns about the sustainability of their non-agricultural income. Consequently, farmers might be hesitant to transfer their land management rights, retaining these rights to secure a fallback for their household livelihoods, which in turn reinforces their reluctance to transfer the land management rights.

Table 3.

Test of the mediating mechanism.

The relatively low level of individual skills among rural residents has diminished the role of land in promoting farmers’ welfare. Empirical results suggest that the positive impact of farmland transfer on farmers’ sense of subjective well-being and life satisfaction becomes insignificant among laborers with low individual skills. Specifically, for those with low individual labor skills, farmland transfer might not lead to an improvement in household welfare. This is primarily because farmers with insufficient personal human capital tend to face employment instability and can only engage in occupations that require low labor skills. Such a situation further raises concerns about whether they could sustain non-agricultural employment, making them reluctant to transfer their land. This phenomenon also needs to be considered in the context of migrant workers’ urbanization.

In essence, the income from farmland transfers was shown to be insufficient to support farmers in pursuing non-agricultural jobs in cities without fear of future risks. Consequently, rural laborers hesitate when considering long-term urban settlement, often referred to as the urbanization of migrant workers. They were concerned about their future, the sustainability of non-agricultural employment, and their present security, including access to social security benefits. This reluctance to transfer land hampers their long-term accumulation of human capital for non-agricultural employment, thereby limiting the enhancement of overall factor productivity.

4.3. Discussion on Heterogeneity

Transferring farmland could either increase household income or yield implicit benefits, which could boost economic efficiency or enhance relationships with neighbors and relatives. The uncertainties inherent in the institutions [36] and transactions of the farmland transfer process were often the focal points where disputes, conflicts, and even malicious incidents tended to concentrate [37]. The social networks within village boundaries and the endowments of farmer households directly shape the relationship between farmland transfer and farmers’ welfare.

Variations in rural governance environments result in differences in the impact of farmland transfer on farmers’ welfare. The empirical results (Table 4) suggest that in villages where groups such as “village tyrants” exist, the effect of farmland transfer on farmers’ subjective well-being was negligible. In contrast, in villages without such groups, farmland transfer significantly enhanced subjective well-being. In rural China, public authority was shown to be relatively weak, and there was a shortage of adequate public security resources, making it challenging to maintain rural public order. Rural governance typically lacks standardized constraint mechanisms [34]. In the presence of “village tyrants”, the rural dispute mediation mechanism becomes imbalanced. Since farmland transfer is inherently a transaction susceptible to disputes, this situation might lead to farmland transfer not achieving large-scale implementation, despite its potential to increase income to some extent or generate implicit benefits such as interpersonal favor.

Table 4.

Heterogeneity analysis (village level).

Empirical results indicated that in villages with respected figures, the effect of farmland transfer on subjective well-being was negligible; conversely, in villages lacking such figures, the effect was notably positive. The presence of respected figures suggested a deficiency in standardized constraint mechanisms within rural governance, where systems intended for openness, transparency, and oversight were effectively nonexistent, which led many rural households to be reluctant to transfer their farmland.

Regarding life satisfaction, the impact of farmland transfer was significantly positive in villages with “village tyrant”-like groups, but even more in villages without such groups. In contrast, in villages with respected figures, farmland transfer had an insignificant impact on life satisfaction. In villages without respected figures, the impact was notably positive.

Differences in household social status and varying degrees of household opinions have heterogeneous impacts on the effect of farmland transfer on farmers’ welfare. Empirical results (Table 5) suggest that with regard to the sense of subjective well-being, farmland transfer has a significantly positive effect on households of middle–upper status, whereas the effect becomes insignificant for those of lower status. Similarly, in terms of life satisfaction, farmland transfer significantly positively impacts households of middle–upper status, but the impact is insignificant for those of lower status. For farmers with lower household status, their household income sources might be relatively singular, and their risk resistance capacity is weaker. Consequently, they might have a stronger need for land as a risk buffer. Their inherent “sentimental attachment to land” was relatively strong, and they have low trust in farmland-related policies, factors that might make them reluctant to transfer their land. Regarding the degree of influence of farmers’ opinions, farmland transfer has a more significant impact on both the sense of subjective well-being and life satisfaction for farmers whose opinions carry greater weight. When farmers’ opinions have little influence, the impact of farmland transfer on their sense of subjective well-being and life satisfaction becomes insignificant. When farmers had the right to speak (i.e., their opinions were valued), they were often better able to advocate for certain rights and interests for themselves and their families, thereby safeguarding the welfare gains from land transfer.

Table 5.

Heterogeneity analysis (individual level).

4.4. Robustness Check

To further ensure the reliability of the conclusions, a series of robustness tests was conducted (Table 6); the tests were implemented through four approaches. For the different methods, Ordinary Least Squares regression was applied in Columns (1) and (2). For the modifying variables, in Columns (3) and (4), the measures of “subjective well-being” and “life satisfaction” were converted into binary (0–1) variables, and Probit regression was employed for estimation. Sample adjustment was performed, given that megacities in China exhibit significantly higher levels of economic development and receive substantially stronger agricultural policy support compared to other regions, factors that may introduce bias into the empirical regression results. Columns (5) and (6) present regression results using a sample excluding the four megacities of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. Outlier elimination was performed, as entrepreneurial households often exhibit substantial heterogeneity. Columns (7) and (8) report regression results with entrepreneurial households excluded from the sample. The empirical results obtained from the different methods, modifying variables, sample adjustment, and outlier elimination were consistent with the baseline regression results, confirming that farmland transfer exerts a significant positive effect on improving farmers’ welfare.

Table 6.

Robustness test.

5. Discussion

5.1. Regional Differences in Land Transfer and Farmers’ Welfare

While studies have shown that land transfer can enhance farmers’ welfare utility, the level of land transfer in China remains relatively low. This paper focuses on land-leasing households to examine the impact of land transfer behavior on farmers’ welfare, and explores the reasons behind households’ hesitancy in making land transfer decisions. On the one hand, farmers might be reluctant to lease out their land due to concerns over the stability of their contractual rights, specifically fearing that the transfer of management rights could lead to uncertainties regarding the security of their land contract entitlements. On the other hand, the instability of the labor market might also discourage farmers from engaging in land transfer. Given the seasonal nature of agricultural production, land transfer usually involves long-term arrangements (i.e., six months or longer). If farmers faced uncertainties in securing stable livelihoods in the non-agricultural sector during this period, they would struggle to obtain alternative sources of income to offset the loss of agricultural earnings. In essence, this predicament exposes them to risks such as unstable non-farm employment, unsustainable income streams, heightened social risks [38], and the anxiety of having no land to cultivate when they return to rural areas.

In most countries and regions worldwide, land is privately owned, with the Civil Law System and Common Law System serving as the two representative legal frameworks. Countries under the Civil Law System generally adopt the right of emphyteusis or similar institutions to regulate agricultural land. For instance, Japan established the circulation rules of emphyteusis through its Civil Code and promoted the separation of land management rights after 1970 to facilitate large-scale farming. Italy stipulates that emphyteusis could be transferred or mortgaged but prohibits sub-leasehold arrangements. France and Germany regulate land transfer, respectively, through the usufructuary right system, with Germany explicitly banning the mortgage of usufructuary rights.

Centered on the core concept of land property rights, the Common Law System guarantees the freedom of land transfer through private ownership, with tenancy systems as the primary form. Legally, it supports the large-scale operation of agricultural land. As for socialist countries, Vietnam practices state ownership of agricultural land, and its Land Law grants farmers seven rights related to land transfer. China implements the collective ownership system for rural land. Several major social transformations in modern Chinese history, including Land Reform, The Three Great Transformations, The People’s Commune Movement, and The Household Contract Responsibility System, have all been closely intertwined with land issues. Moreover, with the implementation of land titling and certification, the three rights of rural land in China—ownership, contractual rights, and management rights—have been gradually clarified. Land transfer in China refers to the circulation of land management rights on the premise of not changing the land use purpose, which ensures the continuity of agricultural production activities. Globally, the development of traditional agriculture needs a more refined agricultural land transfer market [14]. In the Amhara Region, land redistribution has also been adopted to address youth unemployment [39]. Data from Chile demonstrate that the property rights system affects land development by shaping the institutional framework that governs land use rights and resource allocation [40]. Changes in agricultural operating income may constitute a crucial driver of land transfer [41,42]. Additionally, the stability of land contractual relationships was constrained by the improvement of both the land transfer market and the agricultural socialized service market [43].

As a matter of fact, land has long served as a vital livelihood asset for rural residents. With socioeconomic development and demographic shifts, a growing number of countries have recognized the significance of the optimal allocation of land factors. The government of Malawi enacted a series of land laws at the end of 2016, making it easier for smallholder farmers to access land ownership. Particularly in countries lacking a formal land sales market (e.g., Ethiopia), land leasing has emerged as a channel to redistribute land to more efficient agricultural producers. Nevertheless, land leasing markets in most countries are characterized by segmentation (i.e., transactions confined to close social networks), flexible contractual arrangements, and low or even zero rental rates, as exemplified by regions such as North America, Ethiopia, and Guatemala. Such market segmentation might prevent high-efficiency farmers from gaining access to land resources, resulting in efficiency losses in agricultural production. Most existing studies have been conducted from the perspective of land lessees. The lack of discussions on the lessor side is likely to induce biases in research findings and conclusions [44]. In particular, if rural households holding land management rights decided neither to engage in agricultural production nor to lease out their land, land abandonment would ensue. In such cases, the resulting efficiency losses might be even more substantial than those caused by market segmentation. Additionally, issues such as agricultural mechanization in Myanmar [45], land degradation [46], and the improvement of cultivated land quality [47] have also directed greater attention to the welfare effects of land transfer.

Over the past half-century, agricultural productivity has risen rapidly across most parts of Asia, with hunger and poverty rates dropping substantially. In contrast, per capita grain output has grown relatively slowly in Africa, while Latin America has been gradually enhancing its agricultural competitiveness. The trajectory of agricultural development varies significantly across different regions. Nevertheless, improving the sophistication and efficiency of agricultural factor markets remains a critical agenda, whether the goal is to safeguard farmers’ rights and interests, boost grain production, or drive the transformation and upgrading of agricultural practices. The inherent risks associated with land transfer should not be overlooked, and policymakers must take into account their practical implications when formulating and implementing relevant policies.

5.2. Policy Implications

Drawing on the findings and empirical evidence of this study, this paper puts forward targeted policy and practical recommendations from two dimensions. Firstly, it is imperative to formulate a comprehensive policy framework. Farmers might take labor market security into account when transferring their land; if non-agricultural employment was more stable, farmers would be more likely to devote more energy to off-farm work instead of hesitating over land transfer decisions. For instance, when designing land-related policies, it is necessary to integrate policies governing the mobility of production factors such as labor and capital, including the signing of relevant contracts, payment of insurance premiums, and protection of legitimate rights and interests. Efforts should be made to promote the organic integration of rural land transfer policies and urban social security policies. Secondly, it is essential to strengthen sound evaluation and supervision mechanisms in rural areas, improve the transparency of village affairs, and enhance rural residents’ trust in local leaders. This would prevent the opinions of a small number of individuals from dominating rural production and living activities, which could undermine social harmony and stability and thus impair the interests of the majority. Additionally, it should be emphasized that the implementation of any policy would encounter obstacles and challenges. The key lies in ensuring that policies are widely supported and accompanied by well-designed implementation plans. Although these policy recommendations are formulated based on China’s national conditions, they also provide valuable references for most developing countries seeking to advance rural land transfer.

When extrapolating China’s experience to other countries, full consideration must be given to cultural and institutional differences. It is imperative to formulate agricultural factor allocation policies tailored to the agricultural development context of each country and region. Regions with a relatively high level of economic development (e.g., Latin America) might prioritize the high-quality development of agriculture, safeguarding agricultural production and industrialization through the extension of agricultural industrial chains. In contrast, regions with moderately paced economic development (e.g., Asia) should focus on improving factor allocation efficiency on the premise of ensuring food security, for example, by improving the rural land transfer market, enhancing rural social security, and creating enabling environments to promote the market-oriented allocation of factors. For regions with relatively underdeveloped economies (e.g., Africa), the direct improvement of production efficiency can be achieved through the introduction of relevant technologies.

5.3. Limitations

While this paper has incorporated a certain degree of international comparative analysis, inherent limitations such as data characteristics and other constraints have inevitably resulted in several research deficiencies. Firstly, this study has exclusively employed micro-level household survey data from China, which restricts its scope in relation to international comparative research. Future research should systematically collect relevant micro-survey data from other regions and conduct in-depth analyses through cross-country comparative studies to further explore the impact of land transfer on farmers’ welfare. Secondly, this paper focused solely on the land market. In subsequent research, we would incorporate the labor market into the analytical framework, assess the extent to which employment instability affects rural land transfer, and examine the improvement of policies related to both labor and land sectors. Thirdly, land transfer is essentially a dynamic process, and rural households usually take multiple factors into consideration when making land transfer decisions. We have already conducted a multi-period follow-up survey of the sampled households and, in future research, seek to continue to investigate the welfare changes in both land-leasing households and non-leasing households by integrating additional datasets. Finally, the social security system supporting land transfer deserves further empirical exploration.

6. Conclusions

Enhancing farmers’ welfare constitutes a crucial component of the governance objectives centered on “improving people’s well-being and upgrading the quality of life” in most countries. As a vital resource for rural households, the transfer of land management rights plays a pivotal role in advancing farmers’ welfare. This study finds that land transfer exerts a positive effect on improving the household welfare of land-leasing households. However, such positive effects become insignificant in contexts where urban social security provisions are inadequate and individuals possess limited professional skills. Farmers tend to consider leasing out their land only when they can secure stable household livelihoods (China’s current stage, which translates to stable non-agricultural employment) and maintain a relatively stable living status after land transfer (e.g., supported by sound governance mechanisms). In other words, they were more likely to consider it when the risks associated with land transfer were minimal. These findings provide important empirical evidence and theoretical guidance for stimulating the micro-level driving forces of rural land transfer through diversified approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.D.; Methodology, J.K.; Investigation, Z.D.; Writing—original draft, Z.D. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Phase Achievement of the Shanghai Cultural Talent Fund Project (2025-A01); The Youth Fund Project of Humanities and Social Sciences Research, Ministry of Education: “Study on Labor Mobility, Intergenerational Residential Separation, and Rural Elderly Care Service Integration” (24YJCZH123); and The Youth Project of the National Social Science Fund of China entitled “A Study on the Evolution Mechanism and Adaptive Adjustment of the Hierarchical Elderly Care Service Network in Rural Areas Under the Background of Intergenerational Residential Separation” (25CGL100).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chamberlin, J.; Ricker-Gilbert, J. Participation in rural land rental markets in sub-Saharan Africa: Who benefits and by how much? Evidence from Malawi and Zambia. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 98, 1507–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wengle, S.A. Local effects of the new land rush: How capital inflows transformed rural Russia. Governance 2018, 31, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tsai, C.H.; Chung, C.C. Evolution of land system reforms in China: Dynamics of stakeholders and policy transitions toward sustainable farmland use (2004–2019). Heliyon 2024, 10, e37471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Policy Research Office of the Communist Party of China, Office of Rural Fixed Observation Points of the Ministry of Agriculture. Compilation of Survey Data from Fixed Observation Points in Rural Areas Across the Country; China Agricultural Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, W.J. Strategies for Farmland Abandonment Governance: An Analysis Based on a “Market−Organization−Government” Framework. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Shi, H.; Li, B.; Xu, D. The Impact of Whole Region Comprehensive Land Consolidation on Ecological Vulnerability: Evidence from Township Panel Data in Zhejiang Province. Land 2025, 14, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werdiningtyas, R.; Wei, Y.; Western, A.W. The evolution of policy instruments used in water, land and environmental governances in Victoria, Australia from 1860–2016. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B. Land Expansion and Green Rural Transformation in Developing Countries: A Kaya Identity Approach. Land 2025, 14, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.J.; Yan, Z.H.F.; Wu, F.W. Does return of rural labor inhibit agricultural land transfer?—Also on the relationship between employment distance and agricultural land transfer. Rural. Econ. 2024, 1, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo, T.S. Unlocking Agricultural Productivity: The Role of Land Rental Markets in Reducing Resource Misallocation. Agric. Econ. 2025, 56, 1058–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker-Gilbert, J.; Chamberlin, J.; Kanyamuka, J.; Jumbe, C.B.L. How do informal farmland rental markets affect smallholders’ well-being? Evidence from a matched tenant-landlord survey in Malawi. Agric. Econ. 2019, 50, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Cai, D.; Han, K.; Zhou, K. Understanding peasant household’s land transfer decision-making: A perspective of financial literacy. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shi, X.; Qin, Y. Exploring the Effects of Farmland Transfer on Farm Household Well-Being: Evidence from Ore–Agriculture Compound Areas in Northwest China. Land 2024, 13, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Lin, J.; Sexton, R.J. The Transition from Small to Large Farms in Developing Economies: A Welfare Analysis. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2022, 104, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, M.; Holden, S.T.; Tilahun, M. Tenants’ land access in the rental market: Evidence from northern Ethiopia. Agric. Econ. 2019, 50, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F. Insecure land rights and share tenancy: Evidence from Madagascar. Land Econ. 2012, 88, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, H.-J.; Popov, A. Reorganization of Agricultural Land Leases as a Tool for Sustainable Land Use: Comparative Insights from Ukraine and Germany. Land 2025, 1, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorchuk, M.; Popov, A.; Fedorchuk, V. Addressing the spatial shortcomings of agricultural land use: Legal aspects and obstacles. Stud. Iurid. Lublinensia 2024, 33, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, X.; Ma, X.; Rao, F. How to Prevent Farmland Rental Breaches in Large-scale Farmland Market: A Case Study from Jinhu County, Jiangsu Province. Agric. Econ. 2025, 6, 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Jiang, G.; Yu, H. Has rural depopulation reduced agricultural land use efficiency? Mediating roles of cropland abandonment, scale operation, and cultivation structure. Land Use Policy 2025, 159, 107821. [Google Scholar]

- Grabska-Szwagrzyk, E.; Khiabani, P.H.; Pesoa-Marcilla, M.; Chaturvedi, V.; de Vries, W.T. Exploring land use dynamics in rural areas. An analysis of eight cases in the Global North. Land Use Policy 2024, 144, 107246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y.; Hsu, L.Y. Is income catch-up related to happiness catch-up? Evidence from eight European countries. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, I.; Lago-Penas, S. Rural decline and spatial voting patterns. Parliam. Aff. 2024, 78, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, V.; Holl, A. Growth and decline in rural Spain: An exploratory analysis Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 32, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L. Neighborhood harmony, neighborhood governance, and the construction of neighborhood communities. Theory J. 2024, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, D.; Irwin, D.D.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, Y. Predictors of the Prevalence and Importance of the Observed Trinary Control System in Rural China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, K.; Cui, Y.; Cao, H. Formal and Informal Institutions in Farmers’ Withdrawal from Rural Homesteads in China: Heterogeneity Analysis Based on the Village Location. Land 2022, 11, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.F. Neighborhood Does Matter: Farmers’ Local Social Interactions and Land Rental Behaviors in China. Land 2024, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, J.; Deaton, B.; Weersink, A. Do landlord-tenant relationships influence rental contracts for farmland or the cash rental rate? Land Econ. 2015, 91, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, B. Social Networks, Informal Finance and Residents’Happiness: An Empirical Analysis Basedon Data of CFPS in 2016. J. Shanghai Univ. Financ. Econ. 2018, 20, 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.Z.H.; Li, J.S.H.; Zhou, L. Welfare or Pressure: How does Household Debt Affect Residents’ Sense of Happiness—Evidence from the Micro Data of Chinese Households. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2022, 44, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kimball, M.; Willis, R. Utility and Happiness. NBER Working Paper, 25 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera, S.; Moro, M. On the Use of Subjective Well-Being Data for Environmental Valuation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2010, 46, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhang, S.W.; Fu, H.Q. The Impact of Health Shocks on Household Welfare: Evidence from Chinese Households. Nankai Econ. Stud. 2023, 12, 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Lagakos, D.; Mobarak, A.M.; Waugh, M.E. The Welfare Effects of Encouraging Rural—Urban Migration. Econometrica 2023, 91, 803–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, M.; Lane, N.; Querubin, P. The Historical State, Local Collective Action, and Economic Development in Vietnam. Econometrica 2018, 86, 2083–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevas, T.; Skevas, I.; Swinton, S.M. Does Spatial Dependence Affect the Intention to Make Land Available for Bioenergy Crops? J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 69, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H. What lies beneath: Climate change, land expropriation, and zaï agroecological innovations by smallholder farmers in Northern Ghana. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamineh, A.S. The political-economy of communal land distribution for rural youths in Amhara region, Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2025, 157, 107668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio-Pinto, E. The geography of property rights: Land concentration, irrigation access and rural poverty under climate change in Chile. Land Use Policy 2025, 156, 107578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, J.E.; Fernandez-Gimenez, M.E.; Balgopal, M.M. An integrated livelihoods and well-being framework to understand northeastern Colorado ranchers’ adaptive strategies. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 675–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, D.; Ishtiaque, A.; Agarwal, A.; Gray, J.M.; Lemos, M.C.; Moben, I.; Singh, B.; Jain, M. The role of rural circular migration in shaping weather risk management for smallholder farmers in India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. Glob. Environ. Change 2024, 89, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, D. The impact of non-farm employment on the stable land contracting willingness of farm households: Evidence from rural China. Land Use Policy 2025, 157, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Savastano, S.; Xia, S. Smallholders’ land access in sub-Saharan Africa: A new landscape. Food Policy. 2017, 67, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belton, B.; Win, M.T.; Zhang, X.; Filipski, M. The rapid rise of agricultural mechanization in Myanmar. Food Policy 2021, 101, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, J. Property rights and land quality. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2024, 106, 1619–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, C.; Liu, X. Can Land Transfer-In Improve Farmers’ Farmland Quality Protection Behavior? Empirical Evidence from Micro-Survey Data in Hubei Province, China. Land 2025, 14, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).