From Rapid Growth to Slowdown: A Geodetector-Based Analysis of the Driving Mechanisms of Urban–Rural Spatial Transformation in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

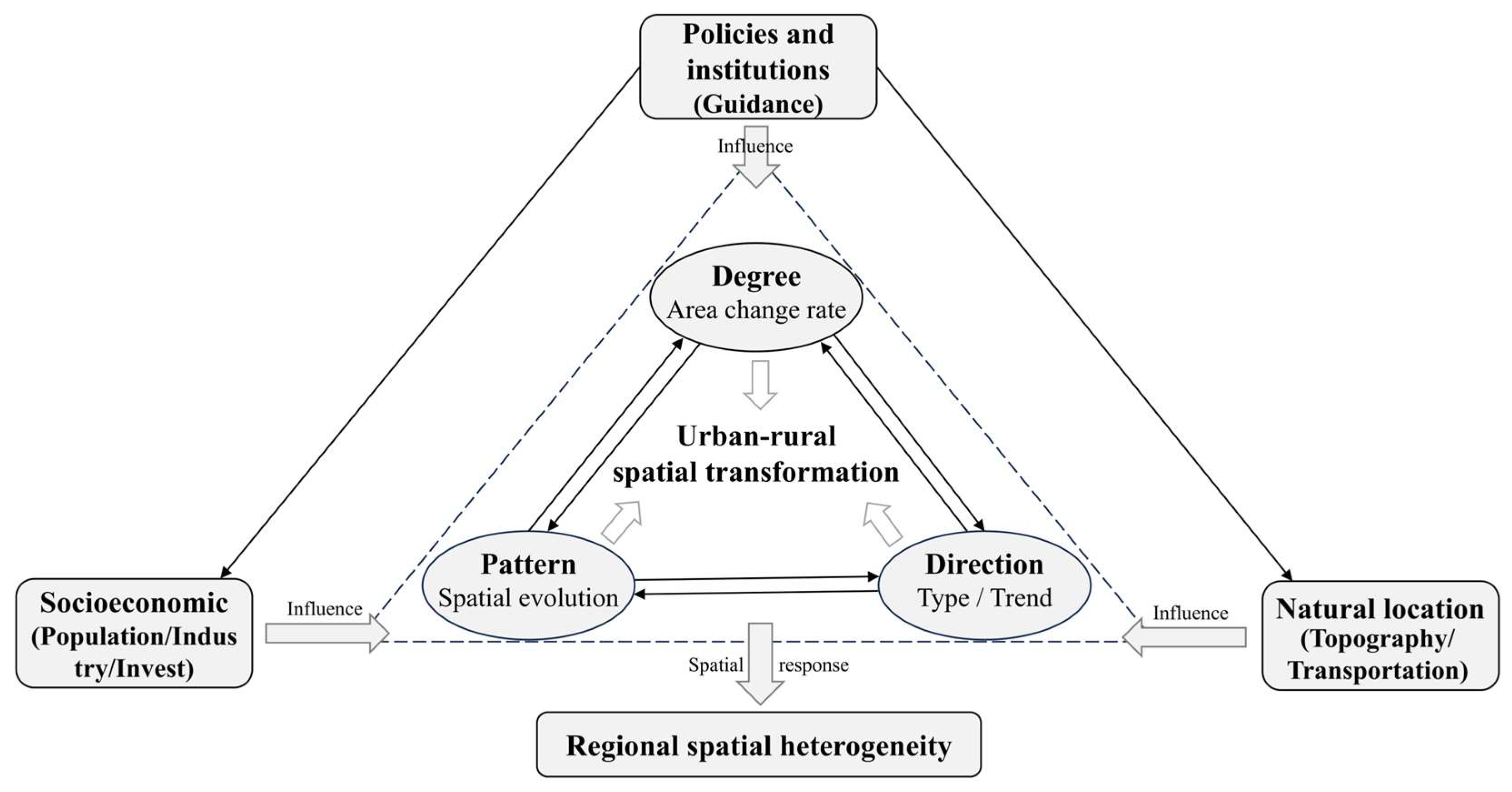

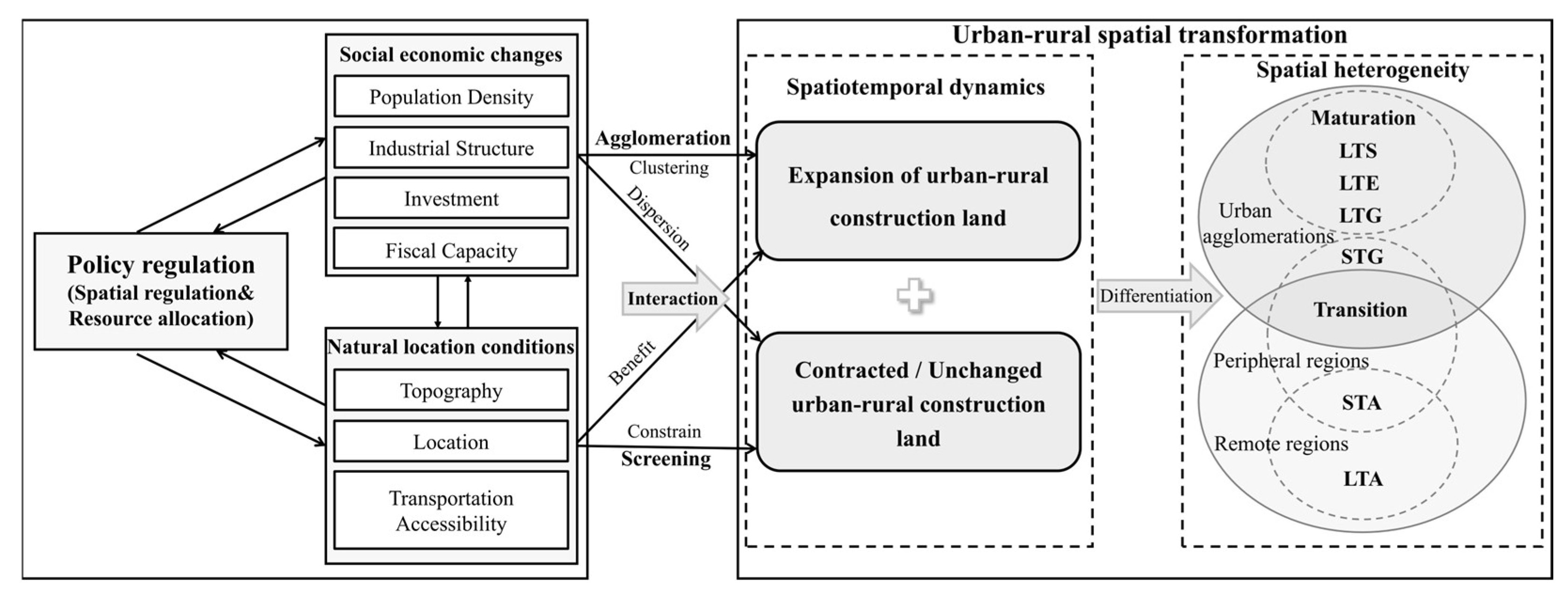

2. Theoretical Framework

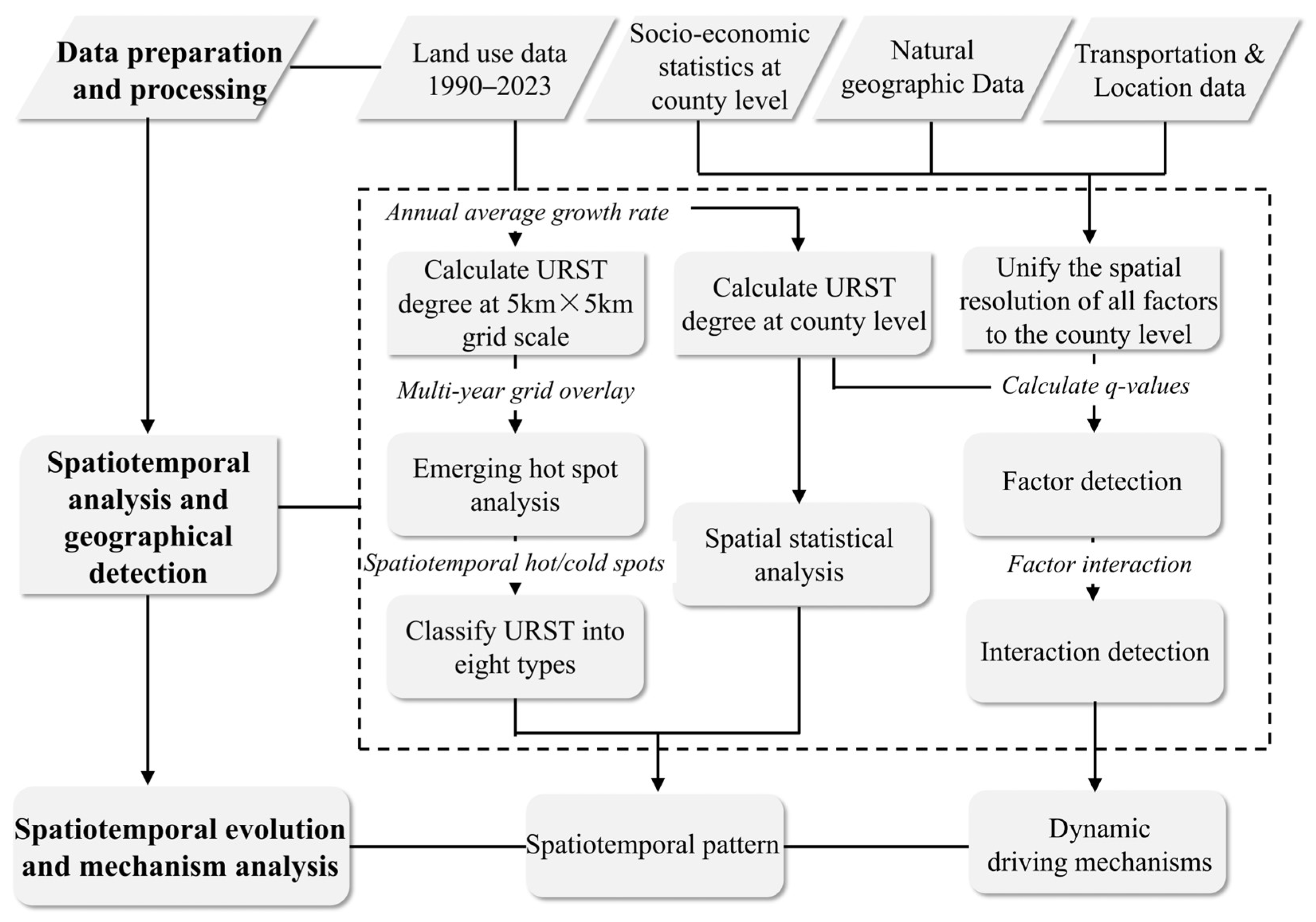

3. Materials and Methods

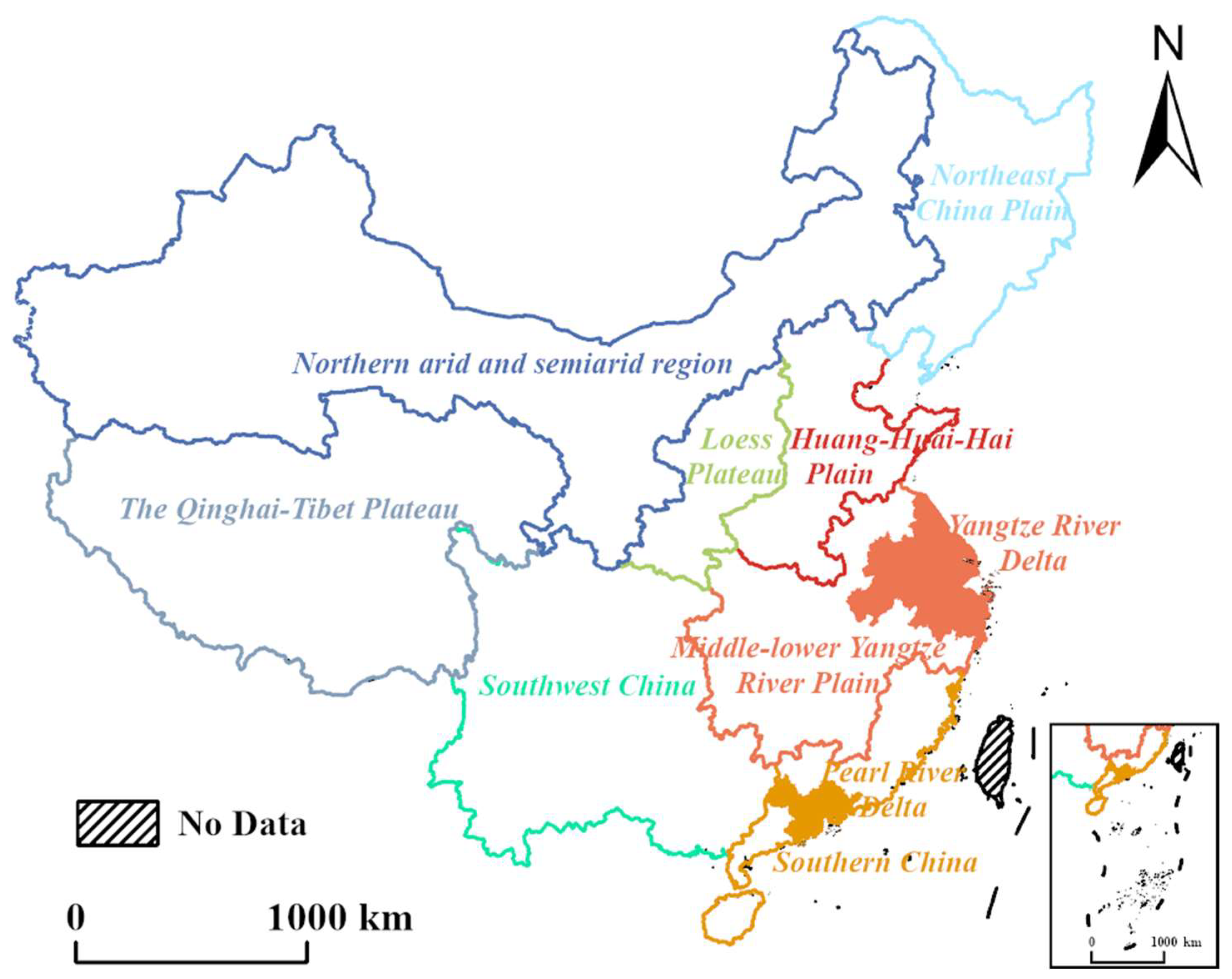

3.1. Data Description

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. URST Degree

3.2.2. Hot Spot Analysis and Type Classification of URST

3.2.3. Geographical Detection of Driving Factors

- 1.

- Factor detector

- 2.

- Interaction detector

4. Results

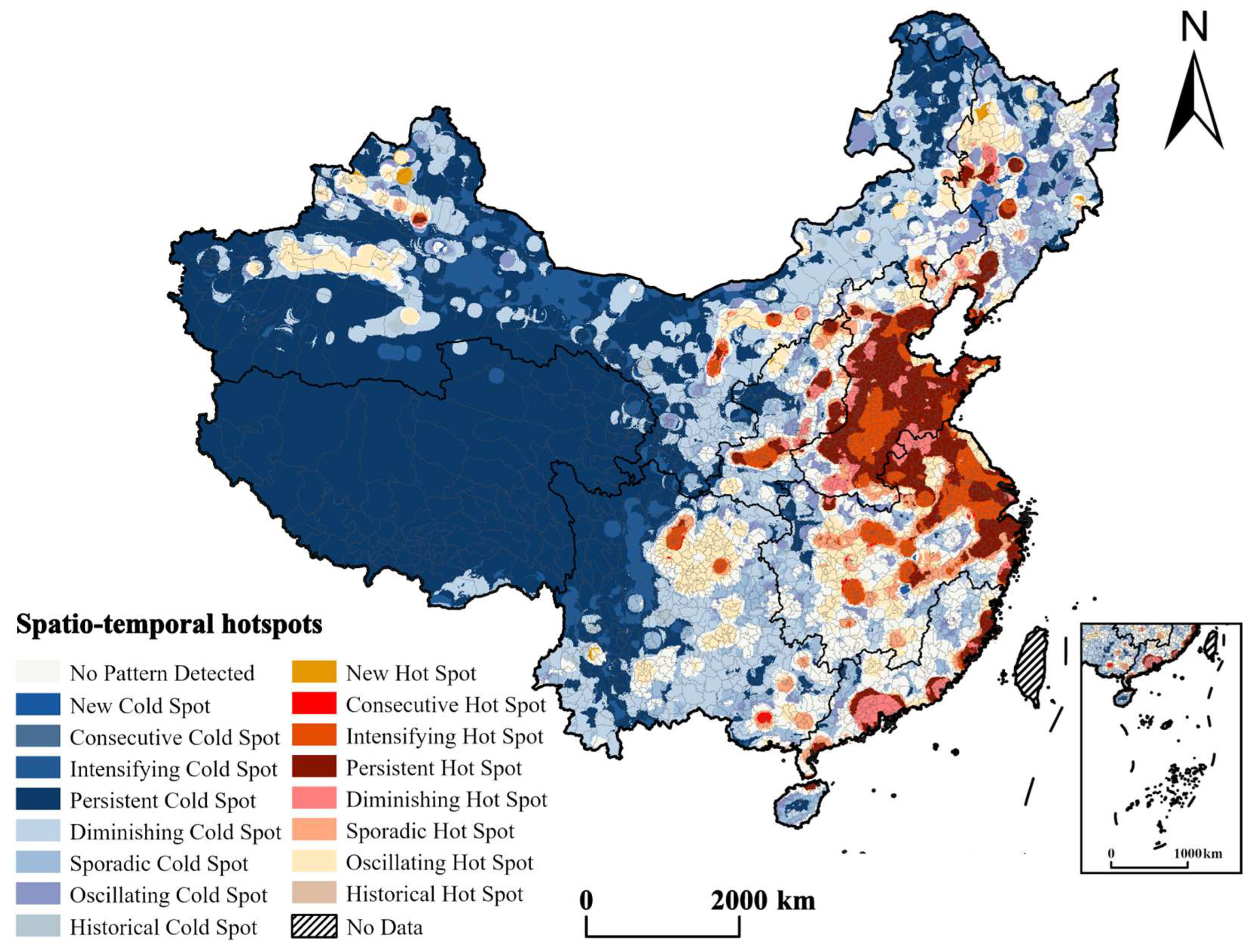

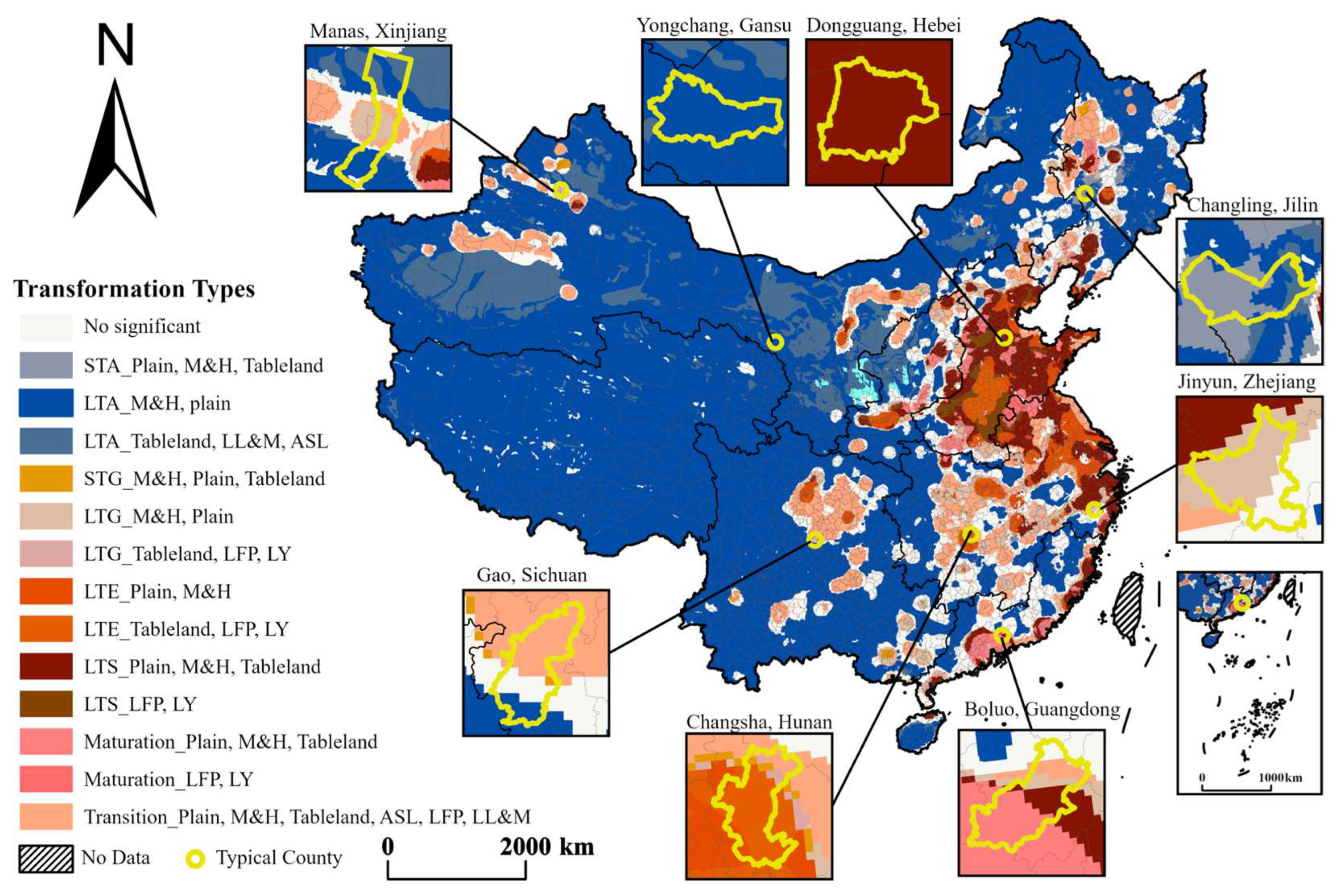

4.1. The Spatiotemporal Evolution Pattern of URST

4.2. Classification and Comparison of URST Types

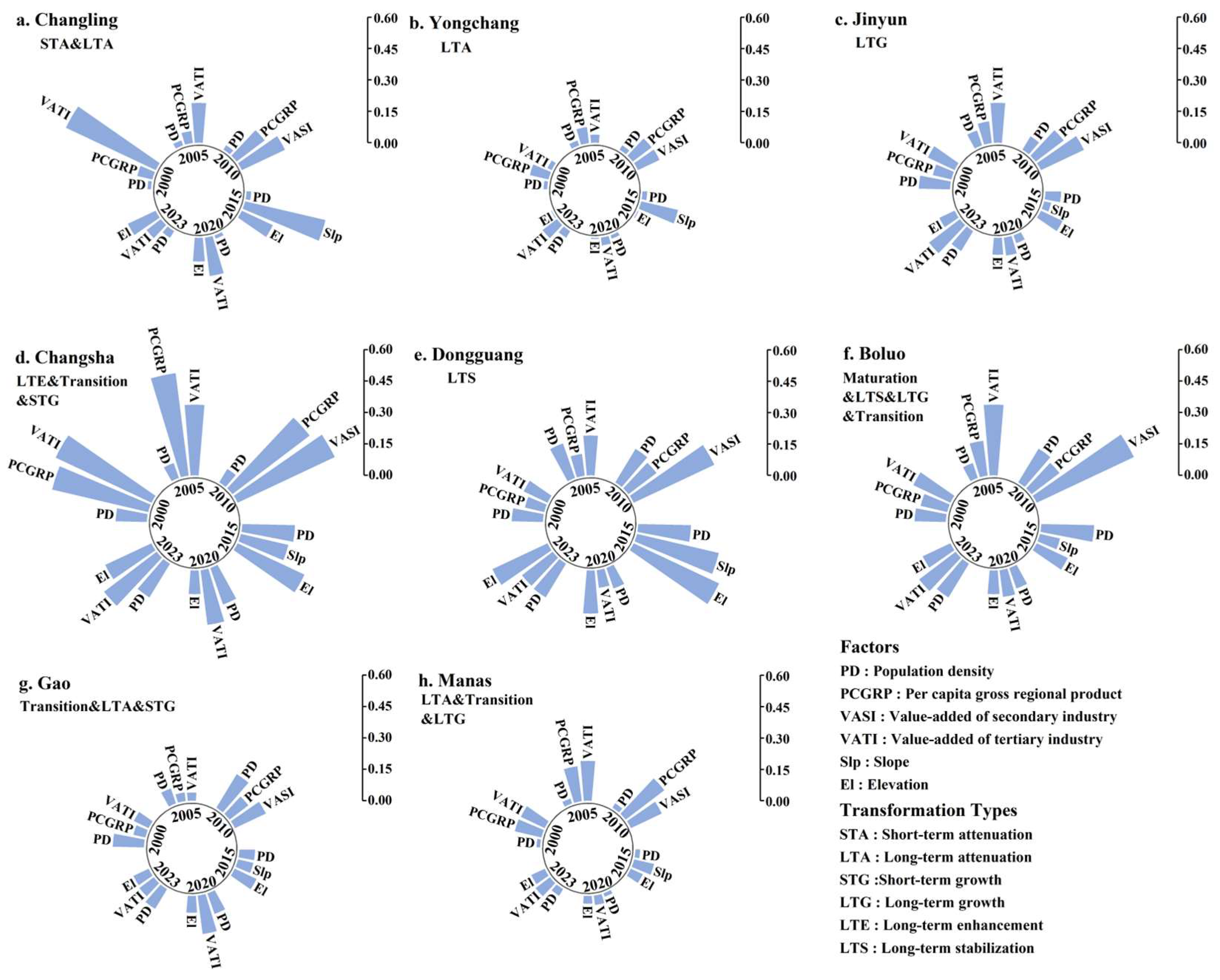

4.3. Influencing Factors of URST

5. Discussion

5.1. Overall Trend of URST and New Directions in Policy Response

5.2. Theoretical Connotations, Realistic Impacts, and Spatial Governance Insights of the URST Pattern

5.3. Driving Mechanisms of County-Level Type Differentiation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| URT | Urban–rural transformation |

| URST | Urban–rural spatial transformation |

| PD | Population density |

| PCGRP | Per capita gross regional product |

| VAPI | Value-added of primary industry |

| VASI | Value-added of secondary industry |

| VATI | Value-added of tertiary industry |

| URIG | Urban–rural income gap |

| UR | Urbanization rate |

| FAI | Fixed asset investment |

| TR | Tax revenue |

| EV | Export value |

| Slp | Slope |

| El | Elevation |

| DR | Distance from rivers |

| DH | Distance from highways |

| DRW | Distance from railways |

| DCR | Distance from city roads |

| DPLC | Distance from prefecture-level cities |

| DPCC | Distance from provincial capital cities |

| STA | Short-term attenuated |

| LTA | Long-term attenuated |

| STG | Short-term growth |

| LTG | Long-term growth |

| LTE | Long-term enhanced |

| LTS | Long-term stable |

| M&H | Mountains and hills |

| ASL | Aeolian sediment landform |

| LL&M | Loess liang and mao |

| LY | Loess yuan |

| LFP | Low flood plain |

References

- Bai, X.; Shi, P.; Liu, Y. Society: Realizing China’s urban dream. Nature 2014, 509, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, S. Spatio-temporal pattern and mechanism of coordinated development of “population-land-industry-money” in rural areas of three provinces in Northeast China. Growth Change 2022, 53, 1333–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y. The spatial pattern of population-land-industry coupling coordinated development and its influencing factor detection in rural China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 2257–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie-Sherman, Y. Rust and reinvention: Im/migration and urban change in the American Rust Belt. Geogr. Compass 2020, 14, e12482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, A. Linking polycentricity concepts to periphery: Implications foran integrative Austrian strategic spatial planning practice. Eur. Plann. Stud. 2018, 26, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta, S.; Atik, M. Rural planning guidelines for urban-rural transition zones as a tool for the protection of rural landscape characters and retaining urban sprawl: Antalya case from Mediterranean. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, C.; Baldomero-Quintana, L. Quality of communications infrastructure, local structural transformation, and inequality. J. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 24, 117–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.; Taylor, C. Promoting rural sustainability transformations: Insights from US bicycle route and trail studies. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 106, 103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Z. Urbanization of county in China: Differentiation and influencing factors of spatial matching relationships between urban population and urban land. China Land Sci. 2023, 37, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tshikovhi, N.; More, K.; Cele, Z. Driving sustainable growth for small and medium enterprises in emerging urban-rural economies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Chen, M.; Fang, F.; Che, X. Research on the spatiotemporal variation of rural-urban transformation and its driving mechanisms in underdeveloped regions: Gansu Province in western China as an example. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, D.; Carson, D.; Argent, N. Cities, hinterlands and disconnected urban-rural development: Perspectives from sparsely populated areas. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Can the integration between urban and rural areas be realized? A new theoretical analytical framework. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu-Mag, R.M.; Petrescu, D.C.; Azadi, H. From scythe to smartphone: Rural transformation in Romania evidenced by the perception of rural land and population. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perroux, F. The concept of growth pole. Appl. Econ. 1970, 8, 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Schen, C.; Li, Y. Differentiation regularity of urban-rural equalized development at prefecture-level city in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Regional development policy: A case of Venezuela; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D. Formation and dynamics of the “Pole-Axis” spatial system. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2002, 22, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Li, S.; Sun, Z.; Guo, R.; Zhou, K.; Chen, D.; Wu, J. The functional evolution and system equilibrium of urban and rural territories. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1203–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, M. Financialisation, financial chains and uneven geographical development: Towards a research agenda. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2017, 39, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.; Banerjee, A. Characterizing land transformation and densification using urban sprawl metrics in the South Bengal region of India. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Yuan, S.; Yang, L.; Skitmore, M. Urban-rural construction land transition and its coupling relationship with population flow in China’s urban agglomeration region. Cities 2020, 101, 102701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, E.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, W. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Urban-Rural Construction Land Transition and Rural-Urban Migrants in Rapid-Urbanization Areas of Central China. J. Urban. Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 05019023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, S.; Deng, W.; Wang, J. Has rural public services weakened population migration in the Sichuan-Chongqing region? Spatiotemporal association patterns and their influencing factors. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delazeri, L.; Da Cunha, D.; Vicerra, P.; Oliveira, L. Rural outmigration in Northeast Brazil: Evidence from shared socioeconomic pathways and climate change scenarios. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 91, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hérivaux, C.; Le Coent, P. Environmental inequalities and heterogeneity in preferences for nature-based solutions. Dév. Durab. Territ. 2023, 14, 23149. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Bi, G. A multidimensional investigation on spatiotemporal characteristics and influencing factors of China’s urban-rural income gap (URIG) since the 21st century. Cities 2024, 148, 104920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennebry, B.; Stryjakiewicz, T. Classification of structurally weak rural regions: Application of a rural development index for Austria and Portugal. Quaest. Geogr. 2020, 39, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, S.; Suzuki, A. The impact of different levels of income inequality on subjective well-being in China: A panel data analysis. Chin. Econ. 2023, 56, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Ge, D.; Sun, J.; Sun, D.; Ma, Y.; Ni, Y.; Lu, Y. Multi-scales urban-rural integrated development and land-use transition: The story of China. Habitat. Int. 2023, 132, 102744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. The core of study of geography: Man-land relationship areal system. Econ. Geogr. 1991, 11, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Q.; Luo, X. Urban-rural spatial transformation process and influences from the perspective of land use: A case study of the Pearl River Delta Region. Habitat. Int. 2020, 104, 102234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R. Urban-rural integration and rural revitalization: Theory, mechanism and implementation. Geogr. Res. 2018, 37, 2127–2140. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Morandell, T.; Wicki, M.; Kaufmann, D. Between fragmentation and integration: Exploring urban-rural coordination in the planning of medium-sized European cities. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frings, H.; Kamb, R. The relative importance of portable and non-portable agglomeration effects for the urban wage premium. Reg. Sci. Urban. Econ. 2022, 95, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Grodach, C.; Taylor, L.; Hurley, J. Zoning and urban restructuring: Long-term change in the location of manufacturing in industrialised city-regions. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 2438316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Song, Y.; Tian, Y. Simulation of land-use pattern evolution in hilly mountainous areas of North China: A case study in Jincheng. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center. Available online: https://cstr.cn/18406.11.Geogra.tpdc.270602 (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- Han, B.; Jin, X.B.; Sun, R.; Li, H.B.; Liang, X.Y.; Zhou, Y.K. Understanding land-use sustainability with a systematical framework: An evaluation case of China. Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Study on Beijing’s urban-rural construction land expansion and evolution of Its spatial morphology. City Plan. Rev. 2016, 40, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, C.; Amrhein, C.; Shah, P.; Stieb, D.; Osornio-Vargas, A. Space-time hot spots of critically ill small for gestational age newborns and industrial air pollutants in major metropolitan areas of Canada. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getis, A.; Ord, J. The analysis of spatial association by use of distance statistics. Geogr. Anal. 1992, 24, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ord, J.K.; Getis, A. Local spatial autocorrelation statistics: Distributional issues and an application. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Christakos, G.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Gu, X.; Zheng, X. Geographical detectors-based health risk assessment and its application in the neural tube defects study of the Heshun Region, China. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, L.; Huang, X. Spatiotemporal differentiation and driving factors of urban-rural integration in counties of Yangtze River Economic Belt. Land 2025, 14, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Haining, R.; Liu, T.; Li, L.; Jiang, C. Sandwich estimation for multi-unit reporting on a stratified heterogeneous surface. Environ. Plann. A 2013, 45, 2515–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Yu, J. City Health Examination Evaluation and Subjective Well-Being in Resource-Based Cities in China. J. Urban. Plan. Dev. 2023, 149, 05023036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Chen, J.; Shi, P. Landscape urbanization and economic growth in China: Positive feedbacks and sustainability dilemmas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Li, X.; Gong, Y.; Li, S.; Cong, X. Resilience evolution of urban network structures from a complex network perspective: A case study of urban agglomeration along the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River. J. Urban. Plan. Dev. 2025, 151, 05024042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Liao, F.; Liu, Z.; Wu, G. Spatial-temporal characteristics and driving mechanisms of land-use transition from the perspective of urban-rural transformation development: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta. Land 2022, 11, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhao, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y. Cropland non-agriculturalization caused by the expansion of built-up areas in China during 1990-2020. Land Use Policy 2024, 146, 107312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Cheng, G. Cultivated land loss and construction land expansion in China: Evidence from national land surveys in 1996, 2009 and 2019. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Jia, S.; Dai, B.; Cui, X. Spatial configuration and layout optimization of the ecological networks in a high-population-density urban agglomeration: A case study of the Central Plains Urban Agglomeration. Land 2025, 14, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Variables | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Social economy | Population density (PD) | person/km2 |

| Per capita gross regional product (PCGRP) | yuan/person | |

| Value-added of primary industry (VAPI) | USD | |

| Value-added of secondary industry (VASI) | yuan | |

| Value-added of tertiary industry (VATI) | yuan | |

| Urban–rural income gap (URIG) | — | |

| Urbanization rate (UR) | % | |

| Fixed asset investment (FAI) | yuan | |

| Tax revenue (TR) | yuan | |

| Export value (EV) | USD | |

| Natural and locational conditions | Slope (Slp) | ° |

| Elevation (El) | m | |

| Distance from rivers (DR) | km | |

| Distance from highways (DH) | km | |

| Distance from railways (DRW) | km | |

| Distance from city roads (DCR) | km | |

| Distance from prefecture-level cities (DPLC) | km | |

| Distance from provincial capital cities (DPCC) | km |

| Types | Geomorphology | Spatial Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| STA | Plain, M&H, Tableland | Northeast region |

| LTA | M&H, plain Tableland, LL&M, ASL | Broad distribution |

| Loess Plateau, northwest in northern arid and semiarid region | ||

| STG | M&H, Plain, Tableland | Northwest, southwest, and outermost periphery of provincial capitals in the northeastern region |

| LTG | M&H, Plain | Northwest and outermost periphery of provincial capitals in the eastern and southwestern region Periphery of the eastern and southwestern provincial capitals |

| Tableland, LFP, LY | ||

| LTE | Plain, M&H Tableland, LFP, LY | Core area of the eastern and southwestern provincial capitals Core and peripheral areas of the eastern and southwestern provincial capitals |

| LTS | Plain, M&H, Tableland LFP, LY | Periphery of the eastern and northwestern provincial capitals |

| Parts of the eastern peripheral region | ||

| Maturation | Plain, M&H, Tableland LFP, LY | Mid-eastern and southern coastal region |

| Mid-eastern provinces border | ||

| Transition | Plain, M&H, Tableland, ASL, LFP, LL&M | Outermost periphery of provincial capitals in the eastern region |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shao, Y.; Yang, R. From Rapid Growth to Slowdown: A Geodetector-Based Analysis of the Driving Mechanisms of Urban–Rural Spatial Transformation in China. Land 2025, 14, 2385. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122385

Shao Y, Yang R. From Rapid Growth to Slowdown: A Geodetector-Based Analysis of the Driving Mechanisms of Urban–Rural Spatial Transformation in China. Land. 2025; 14(12):2385. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122385

Chicago/Turabian StyleShao, Yang, and Ren Yang. 2025. "From Rapid Growth to Slowdown: A Geodetector-Based Analysis of the Driving Mechanisms of Urban–Rural Spatial Transformation in China" Land 14, no. 12: 2385. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122385

APA StyleShao, Y., & Yang, R. (2025). From Rapid Growth to Slowdown: A Geodetector-Based Analysis of the Driving Mechanisms of Urban–Rural Spatial Transformation in China. Land, 14(12), 2385. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122385