Abstract

Woody encroachment (WE) refers to the expansion of woody vegetation, particularly scrubs, into grasslands, altering ecosystem structure, function, and vegetation phenology. WE is especially pronounced in arid and semi-arid regions, where climate variability, land use, and ecological resilience interact strongly. Even though long-term monitoring of these dynamics in protected areas is essential to understanding landscape change and guiding conservation strategies, a few studies address this. The Flora and Fauna Protection Area (FFPA) Bavispe, a sky island in northwestern Mexico, provides an ideal setting to examine WE. Using remote sensing, we analyzed 30 years of land cover change (Landsat 5 TM and Landsat 8 OLI) in two reserve zones, Los Ajos and La Madera, and their 5 km buffer areas. Additionally, NDVI-based regressions (MODIS MOD13Q1) were applied to assess phenological responses across vegetation types. Classifications showed high accuracy (Kappa > 0.75) and revealed notable woody expansion: 960 ha of oak forest and 1322 ha of scrubland gained in Los Ajos, and 1420 ha of scrubland in La Madera. Grasslands declined by 2234 ha in Los Ajos and 1486 ha in La Madera, with stronger trends in surrounding buffers. Phenologically, the onset of the growing season was delayed by ~2 days per year in Los Ajos and ~3 days in La Madera. A generalized increment of woody vegetation in the region and the observed change in phenophases in selected land cover types indicated a shift in regional drivers (human or other ecological state factor) related to land cover distribution.

Keywords:

woody encroachment; phenology; remote sensing; LULCC; sky islands; arid zone; protected area 1. Introduction

Grasslands across North America are rapidly disappearing and degrading due to the expansion of woody vegetation [,,]. This process, known as woody encroachment (WE), involves the increase in woody plant density, cover, and biomass, native or exotic, within areas once dominated by grasses [,,,]. Its drivers are context-dependent, emerging from the interaction of multiple environmental and anthropogenic factors, including land-use change, climate variability, altered fire regimes, elevated atmospheric CO2, and increased nitrogen deposition [,,]. WE profoundly alters vegetation structure, converting open grasslands and savannas into closed-canopy systems []. These structural shifts reduce plant richness and diversity and modify environmental conditions such as soil properties and vegetation phenology [,,]. Furthermore, WE promotes soil erosion and decreases soil carbon storage and is therefore widely considered a form of land degradation [,,].

In this context, research on plant phenology has gained importance due to shifts observed in plant communities as a consequence of climate change and its effects on ecosystem functioning [,,]. In addition, changes in plant biological cycles can have repercussions on species interactions, potentially altering ecological relationships (e.g., mutualism) and leading to biodiversity loss [,]. Recent technological advances have enabled the monitoring of phenological patterns across broad spatial and ecological scales. Variations in the timing and duration of these events directly influence key terrestrial processes []. Consequently, phenological metrics are now fundamental indicators for assessing ecosystem responses to environmental changes across temporal scales, from gradual climate-related shifts to medium-term variations driven by management or abrupt disturbances [,,].

The WE phenomenon has been widely documented across a broad range of biomes on all continents except Antarctica, with drylands accounting for approximately 67% of reported cases [,]. According to previous studies, grasslands occurring in arid and semi-arid environments are particularly vulnerable due to their inherent susceptibility to climatic shifts, which is exacerbated by elevated temperatures, variable precipitation patterns, and human activities [,,]. These areas support 40% of the global population [] and are largely composed of rangelands used primarily for pastoralism, with limited areas under dryland farming. In Mexico, arid and semi-arid lands represent approximately 60% of the national territory. These ecosystems are not only home to a significant portion of the country’s population but also harbor numerous endemic species and provide essential ecosystem services []. A considerable portion of these landscapes has undergone woody plant encroachment, often accompanied by varying degrees of land degradation and, in more severe cases, desertification [].

Given the ecological importance of arid and semi-arid regions, especially in Mexico, it is essential to monitor and understand the dynamics of WE and analyze its effects on native ecosystems. Natural Protected Areas (NPAs) represent a key policy instrument for biodiversity conservation, and their management and administration currently fall under the responsibility of the Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP). As of now, CONANP oversees 226 NPAs under various protection categories [,,,]. These areas are designed to preserve large, representative portions of the country’s most important and best-conserved natural ecosystems. In addition, NPAs play an important role in the design of sustainable production systems, as they serve as essential benchmarks for ecological sustainability. For these reasons, NPAs offer ideal conditions for conducting long-term scientific research []. Among these Natural Protected Areas, the FFPA Bavispe stands out as a region of exceptional ecological importance. The mountain ranges that compose this NPA lie within a transitional zone encompassing more than 60 ranges and peaks across Arizona, Sonora, New Mexico, and Chihuahua, collectively known as the Sky Islands []. The FFPA is situated within the mountainous massif of the Sierra Madre Occidental, featuring a heterogeneous landscape that extends from undulating foothills to elevations exceeding 2000 m. These elevational gradients generate distinctive ecosystem diversity patterns []. The Sky Islands provide a valuable natural setting for examining plant responses to environmental variation across a wide array of vegetation communities, as their elevation gradients closely reflect moisture gradients []. Despite this ecological richness, the region has undergone substantial changes driven by human activities. As described by Castellanos-Villegas et al. [], extensive cattle ranching, established in central Sonora since the early sixteenth century, has progressively altered the landscape. Once dominated by semi-arid grasslands, thornscrub, and open oak woodlands, the area has transitioned into predominantly semi-arid scrublands, resulting in a significant decline in habitat quality.

Studies regarding landscape analysis on the advancement of woody cover are lacking for the FFPA Bavispe. Advances in remote sensing technologies have provided a solid foundation for evaluating and analyzing ecological processes over a large extension of land. Coupled to these technologies, the use of geoinformatics tools has facilitated the integration of spatial dimensions into land use change analysis, incorporating factors such as population pressure, climate, topography, and others that influence landscape transformation [,,].

Considering the above, this study applies remote sensing techniques to monitor land use and land cover changes within the FFPA Bavispe. We focus on the spatial and temporal dynamics over the past 30 years, particularly examining whether woody vegetation typically associated with lower elevations has expanded into high-elevation communities, how much this expansion has varied, and whether similar dynamics occur within the 5 km buffer zone. Additionally, we assess how this expansion has affected vegetation phenology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

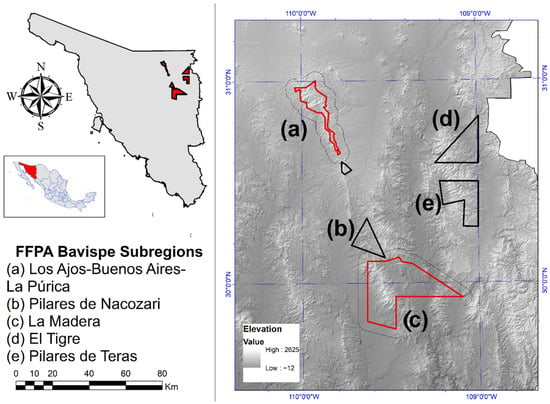

The FFPA Bavispe is in the northwestern portion of the state of Sonora, within the extreme geographical coordinates of 29°54′45″ to 31°20′54″ North Latitude and 108°43′27″ to 110°30′29″ West Longitude. It lies within the Sierra Madre Occidental physiographic province, featuring an altitudinal gradient ranging from 540 m above sea level to 2645 m. According to INEGI [] and Garcia [], the dominant climate types are: Temperate semiarid (BS 1k (x’)), Warm semiarid (BS 1h (x’)), and Warm arid (BS oh (x’)). The mean annual temperature varies, ranging from 15.3 °C to 21.4 °C. Annual precipitation in the mountainous areas is approximately 500 mm, exceeding 600 mm at the highest elevations. Dominant vegetation types include riparian forests with species like Populus fremontii, Platanus wrightii, and Juglans major; pine–oak and oak forests featuring Quercus spp., Pinus cembroides, and Juniperus spp.; and arid scrublands dominated by Fouquieria splendens, Lysiloma watsonii, Bursera spp., and Stenocereus thurberi, among others []. The FFPA Bavispe harbors remarkable biodiversity, with approximately 1225 vascular plant species.

According to CONANP [], FFPA Bavispe is composed of five sections that span parts of 12 municipalities in the state of Sonora. Although they do not have formally established zoning, these municipalities function as the reserve’s area of influence. These five sections cover a total area of approximately 200,898.25 hectares. In order to address the most northern and southern (latitudinal range) sections of the reserve (which also present different altitudinal ranges), only sections 4 and 5 are considered, corresponding to Sierra Los Ajos–Buenos Aires–La Púrica and Sierra La Madera, respectively. Together, they represent more than half of the reserve’s total area (119,542.25 hectares) (Figure 1). Likewise, to observe the dynamics in the areas adjacent to each selected section, a 5 km buffer zone was considered. According to [], this buffer width has been commonly applied in land cover change assessments to account for transition processes and external anthropogenic impacts near the boundaries of protected areas. It has been suggested that surrounding land-use pressures can significantly influence the ecological integrity of the target ecosystem, supporting the suitability of this buffer distance for evaluating adjacent land-use dynamics. Cartographic design was carried out using ArcMap 10 (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA).

Figure 1.

Location of the sections of the FFPA Bavispe in northeastern Sonora, Mexico. The sections considered in this study are highlighted in red: (a) Los Ajos–Buenos Aires and (c) La Madera. The 5 km buffer area is shown with a black outline.

2.2. Datasets Used

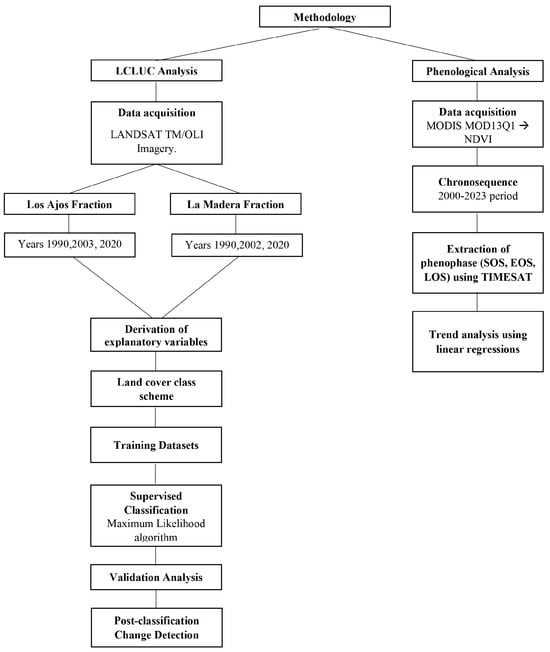

Supervised vegetation classifications were generated for the years 1990, 2002–2003, and 2020 using satellite imagery from two different Landsat sensors (TM and OLI) (USGS, Sioux Falls, SD, USA). A post-classification change detection analysis was conducted based on these Landsat-derived classification products. In addition, phenological shifts were evaluated using the MODIS MOD13Q1 product by extracting NDVI time series for the period 2000–2023. From these series, key phenophases were derived, including the start of the season, the minor integral, and the duration of the growing season. Linear regression analyses were then performed to assess temporal trends (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart illustrating the main methodological activities carried out for the land-use change and phenological trend analyses.

For the chronosequence spanning from 1990 to 2020, Landsat 5 TM and Landsat 8 OLI satellite images were used. For both areas in our study, we derived classifications for the initial (early 1990s), middle (during the 2000s), and final (for 2020) stages for land cover distributions. For Los Ajos, the years 1990, 2003, and 2020 were selected; for La Madera, 1990, 2002, and 2020 were chosen, based on comparable precipitation levels across years based on CHIRPS data extracted from Google Earth Engine. Image selection was based on a cloud cover threshold of less than 5%. Specifically, Landsat Collection 2, Level 2 (L2C2) images were used, which are atmospherically corrected to account for effects such as absorption and scattering, providing a more accurate representation of Earth’s surface []. To capture the widest spectral range (due to vegetation phenological stages), two dates were selected for each year, one representing the dry season and one for the rainy season.

For the Ajos fraction, images from the Thematic Mapper (TM) sensor were used in 1990 (18 April and 27 October) and in 2003 (22 April and 13 September), as well as images from the Operational Land Imager (OLI) sensor in 2020 (6 May and 27 September). In the case of the Madera fraction, TM images correspond to 1990 (27 April and 4 October) and 2002 (14 May and 5 October), while OLI images from 2020 were acquired on 13 April and 6 October. This selection allowed for the capture of both seasonal and temporal variability in the two regions.

2.3. Variables and Ancillary Data

From the selected Landsat products, a set of explanatory variables was derived, directly related to vegetation processes (phenology and function) and/or to the characterization of surface features within the landscape []. These included reflectance values [], vegetation indices such as NDVI [], MSAVI [], and EVI [,], as well as statistical transformations like Principal Components Analysis and Tasseled Cap []. In addition, digital elevation models were obtained from the National Elevation Dataset (NED), with a spatial resolution of 30 m, matching that of the Landsat data, from which slope and aspect were derived []. The final input datasets (per classified year) consisted of 41 layers for Landsat TM and 45 for Landsat OLI.

2.4. Classification Schemes

A classification scheme was developed for the main vegetation covers present in the study areas (Table 1 and Table 2). To achieve this, information was compiled and compared from Anderson [] cartographic data and descriptions from INEGI [] and CONANP [], as well as contributions from Denisse-Pacheco []. Its primary goal is to group vegetation into well-differentiated physiognomic and ecological units. Particular attention was given to mountain communities such as grasslands, oak forests, pine forests, and scrubs, due to their role in the dynamics of woody encroachment.

Table 1.

Classification scheme for the Los Ajos Fraction.

Table 2.

Classification scheme for the La Madera Fraction.

2.5. Training Points

To run a supervised classification, training points were required for each of the five land cover classes present in the study area. These points were primarily obtained from two sources: (1) field surveys and (2) visual interpretation using the Google Earth Pro platform. The number of training points assigned to each class depended on the availability of field data and the ability to distinguish the classes in high-resolution imagery. For the Los Ajos fraction, a total of 1133 training points were collected, while for the La Madera fraction, 1368 points were used. Additionally, an independent set of 55 validation points per class was collected, explicitly separate from and not overlapping with the training dataset, to ensure an unbiased accuracy assessment [,].

2.6. Classification Model and Accuracy Assessment

The classification method employed was based on the Maximum Likelihood (ML) algorithm [,,,]. This approach relies on a solid theoretical foundation and assumes that the classes follow a multivariate normal distribution. It incorporates statistical parameters such as the mean, variance, and covariance of each category in each spectral band, enabling the establishment of discriminant functions for class assignment. In traditional remote sensing image classification, the Maximum Likelihood (ML) algorithm is widely used due to its statistical robustness []. The process involves calculating the mean and variance of each class based on previously defined regions of interest; using these values, a classification function is built to estimate the probability of each pixel belonging to the different classes. Finally, each pixel is assigned to the class whose likelihood function yields the highest value. The strength of this method lies in its clear parameter interpretability and its ease of integration with prior knowledge. The algorithm is simple and straightforward to implement when compared to other classifiers [,].

This algorithm was implemented using ArcGIS version 10.5 software. To assess land cover both inside and outside the study site, classifications were also conducted for a surrounding influence zone within a 5 km buffer around each section of the reserve.

To assess the performance of the classification algorithm, confusion matrices were generated for each reference year with 55 points per class, enabling comparison between actual classes (based on training point pixels) and the classified outputs. The diagonal values in each matrix represent the number of correctly classified pixels per category. Each land cover map includes key accuracy metrics: producer’s accuracy, user’s accuracy, overall accuracy, and the Kappa index [], which is calculated based on a ratio. The numerator represents the difference between the sum of observed agreements and the sum of agreements expected by chance, while the denominator represents the difference between the total number of observations and the sum of agreements expected by chance. Conceptually, the Kappa coefficient formula can be expressed as follows:

where

k = (Po − Pe)/(1 − Pe)

- Po = Proportion of observed agreement (sum of the main diagonal of the confusion matrix divided by the total number of observations).

- Pe = Proportion of agreement expected by chance, calculated from marginal proportions.

2.7. Post-Classification Change Detection Analysis

To identify changes in cover classes and the magnitude of these changes over time, corresponding analyses were performed from 1990 to 2020. For this purpose, previously generated vegetation cover maps were used, and a post-processing analysis was conducted using QGIS version 3.40.1 (QGIS Geographic Information System, Dublin, OH, USA) [] with the MOLUSCE plugin to create the change detection layer. This analysis provides information on area changes and percentage changes for each class over the years and is useful for detecting ecosystem transformation dynamics. Additionally, flow diagrams (Sankey plots) were created in R version 4.3.0 [] to visualize the transitions between land cover classes and the relative magnitude of these changes.

2.8. Phenology Modeling

To evaluate vegetation phenological trends (Figure 2), a subset of MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) data was downloaded through the APPEEARS platform (Application for Extracting and Exploring Analysis Ready Samples). For this study, the MOD13Q1 product, which provides NDVI values, was selected. This dataset has a spatial resolution of 250 m and a temporal resolution of 16 days, which introduces certain limitations, including potential mixed-pixel effects that may affect the detection of fine-scale vegetation dynamics. The image series spans from 1 January 2000, to 31 December 2023, resulting in a 24-year chronosequence composed of 23 composites per year (552 composites in total). The images were processed to generate chronological composites using ArcGIS software []. Based on the land-cover change raster generated for the 1990–2020 period, the following transitions were selected for the Los Ajos fraction: (1) oak vegetation that transitioned to scrubland, (2) grassland that transitioned to scrubland, and (3) scrubland that remained stable. For the La Madera region, the transitions considered were (1) oak–pine forest that transitioned to scrubland, (2) grassland that transitioned to scrubland, and (3) scrubland that persisted as a stable category. The selection of these vegetation types was based on the presence of patches with a minimum size of 250 × 250 m (equivalent to one MODIS pixel), ensuring that the MODIS-derived information corresponded appropriately to the evaluated transition.

Phenological parameters were obtained using the software TIMESAT 3.3, an open-source program specialized in phenological analysis of time-series data obtained from satellite sensors []. For this study, three parameters were extracted: Start, Duration, and Minimum Integral of the growing seasons. For the smoothing of the time series, we used a Savitsky–Golay filter. The start of the season was defined as a 20% increase relative to the curve baseline, and the end of the season as an 80% decrease compared to the peak of the curve. Considering the seasons as fluctuations in productivity, these parameters were based on previous studies [,]. All these parameters were derived from extractions of the MODIS-NDVI time series described before, using averages for the pixels in each site selected.

Linear regression analyses were conducted for each phenophase and its corresponding value using the R software (version 4.4.0) environment. This approach allowed for the assessment of temporal trends and relationships within the phenological data, providing insights into how specific growth phases have changed over time.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Land Cover Changes

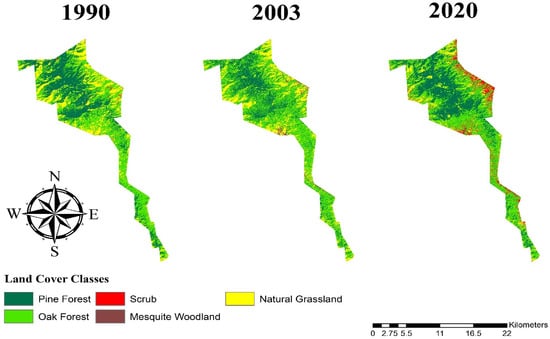

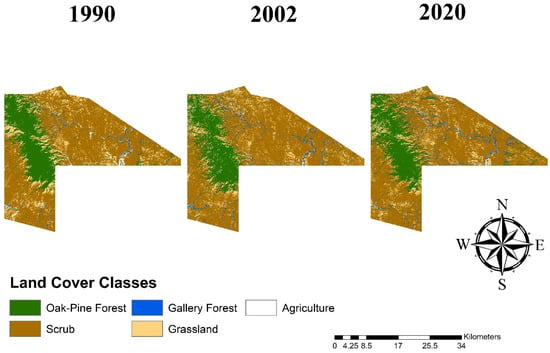

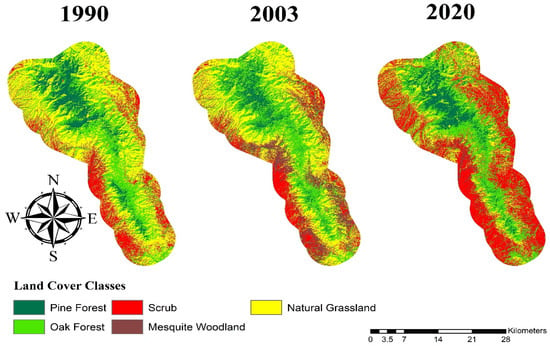

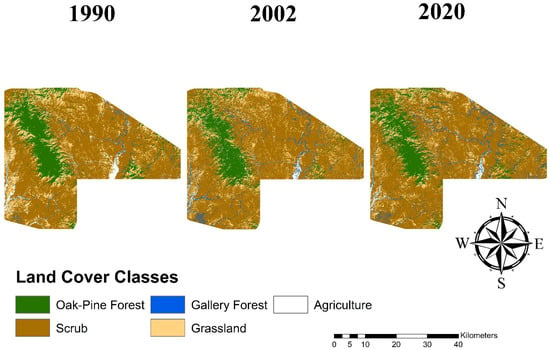

Land cover maps were generated for the years 1990, 2003, and 2020 for the Los Ajos fraction (Figure 3). Similarly, land cover maps were produced for the years 1990, 2002, and 2020 for the La Madera sector (Figure 4). Post-classification accuracy assessments indicated overall classification accuracies ranging from 83% to 92%, with Kappa coefficients between 0.79 and 0.90 (Table 3 and Table 4). According to established criteria, such as those proposed by Landis and Koch [], these values are considered acceptable given the spatial and temporal resolution of the satellite sensors employed.

Figure 3.

Land cover maps for 1990, 2003, and 2020 in the Los Ajos fraction.

Figure 4.

Land cover maps for 1990, 2002, and 2020 in the La Madera fraction.

Table 3.

Precision analysis summary for the 1990, 2003, and 2020 classifications for the Los Ajos Fraction.

Table 4.

Precision analysis summary for the 1990, 2003, and 2020 classifications for the La Madera Fraction.

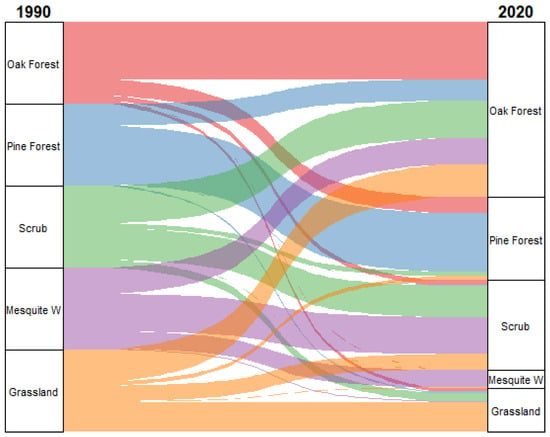

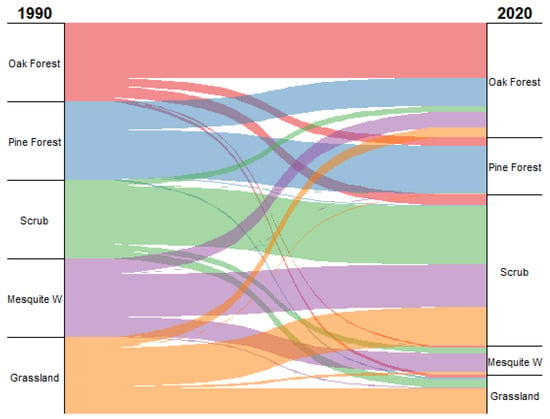

The results of this study indicate that between 1990 and 2020, the Los Ajos sector experienced a reduction of 81.41 hectares of pine forest, decreasing from 7033.14 ha in 1990 to 6947.73 ha in 2020. This change represents a loss of −1.214% relative to the original extent of this land cover type. In contrast, oak forest showed a notable expansion, increasing by 960.57 ha over the same period, from 8702.46 ha to 9663.03 ha, equivalent to an 11.03% increase from its initial area. Scrub exhibited the most dramatic transformation, expanding by 1322.64 ha, from just 101.34 ha in 1990 to 1423.98 ha in 2020, corresponding to a 1305.151% increase. Similarly, mesquite woodland experienced a substantial gain of 41.85 ha, growing from 101.34 ha to 1424.98 ha, which represents a 153.97% increase. Natural grassland, on the other hand, showed the most significant loss in spatial extent, with a reduction of 2239.65 ha, decreasing from 4261.41 ha in 1990 to only 2021.76 ha in 2020. This constitutes a −52.55% decline relative to its original area (Table 5). Changes and their magnitudes between land cover classes can also be observed (Figure 5).

Table 5.

Change Analysis (ha) from 1990 to 2020 in the Los Ajos Fraction.

Figure 5.

Land cover change flows between 1990 and 2020 in the Los Ajos fraction. The width of the bands represents the magnitude of each change, with the bars on the left showing the proportion of cover types in 1990 and those on the right representing 2020.

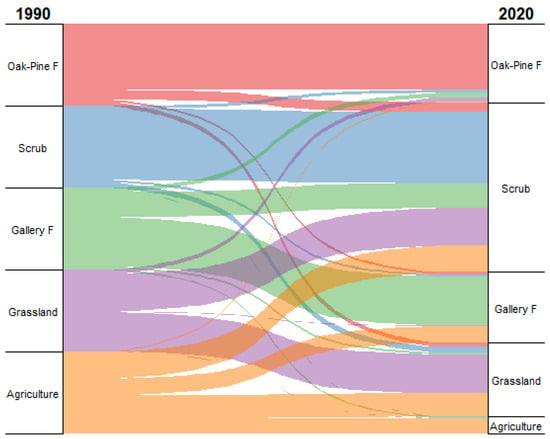

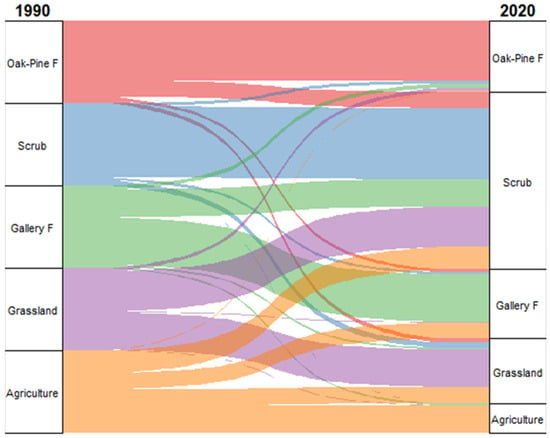

In the case of the La Madera sector, between 1990 and 2020, scrub remained the dominant land cover type, increasing by 1420.74 hectares, from 61,335.36 ha to 62,756.10 ha, representing a 2.316% expansion. Gallery forest also showed a significant increase, growing from 1603.89 ha to 3457.35 ha, which corresponds to a net gain of 1853.46 hectares or 115.56%. Oak-Pine Forest experienced a reduction of 852.84 hectares, decreasing from 19,638.81 ha to 18,785.97 ha, equivalent to a −4.343% loss in surface area. Grassland also declined, losing 1486.98 hectares, from 13,542.75 ha to 12,055.77 ha, corresponding to a −10.980% decrease, likely associated with the expansion of scrub. Finally, agricultural land showed a pronounced reduction of 934.38 hectares, dropping from 1374.30 ha to 439.92 ha, representing a −67.99% decrease from its original extent (Table 6). Changes and their magnitudes between land cover classes can also be observed (Figure 6).

Table 6.

Change Analysis (ha) from 1990 to 2020 in the La Madera Fraction.

Figure 6.

Land cover change flows between 1990 and 2020 in the La Madera fraction. The width of the bands represents the magnitude of each change, with the bars on the left showing the proportion of cover types in 1990 and those on the right representing 2020.

Similarly, the same procedure was conducted using a 5 km buffer zone for both the Los Ajos sector (Figure 7) and the La Madera sector (Figure 8) in order to assess whether patterns observed within the core area were consistent in the surrounding landscape.

Figure 7.

Land cover maps for the years 1990, 2003, and 2020 for the Los Ajos Fraction considering the 5 km influencing zone.

Figure 8.

Land cover maps for the years 1990, 2002, and 2020 for the La Madera Fraction considering the 5 km influencing zone.

When considering the 5 km buffer zone around the Los Ajos fraction, the land cover change analysis (Table 7) shows that natural grassland experienced the most substantial loss in spatial extent, with a decrease of 19,909.53 hectares between 1990 and 2020, representing a −59.17% reduction from its initial coverage. In contrast, scrubland underwent a significant expansion, gaining 18,629.10 hectares, which corresponds to a 161.815% increase relative to its original area. Oak forest also expanded, increasing by 2331.09 hectares, from 24,136.65 ha to 26,467.74 ha, equivalent to a 9.658% increase. Conversely, pine forest decreased by 1378.98 hectares, from 10,796.13 ha to 9417.15 ha, representing a −12.77% loss in surface area. Finally, mesquite woodland showed a moderate increase of 328.32 hectares, from 2696.49 ha to 3024.81 ha, which constitutes a 12.17% increase in its extent. Changes and their magnitudes between land cover around the 5 km buffer classes can also be observed (Figure 9).

Table 7.

Change Analysis (ha) from 1990 to 2020 in the Los Ajos fraction with 5 km buffer.

Figure 9.

Land cover change flows between 1990 and 2020 in the Los Ajos fraction considering the influence zone. The width of the bands represents the magnitude of each change, with the bars on the left showing the proportion of cover types in 1990 and those on the right representing 2020.

In the 5 km buffer zone surrounding the La Madera sector (Table 8), a notable expansion of scrub was observed, with an increase of 7493.04 hectares, from 114,490.26 ha in 1990 to 121,983.30 ha in 2020, representing a 6.545% increase in its original extent. Gallery forest also experienced a substantial gain, increasing by 4208.67 hectares, from 3157.47 ha to 7366.14 ha, which corresponds to a 133.292% rise in surface area. Oak-Pine Forest showed a reduction of 1980.81 hectares, declining from 28,220.67 ha to 26,239.86 ha, equivalent to a −7.019% decrease. Grassland also underwent a significant reduction, losing 7167.06 hectares, from 30,989.97 ha to 23,822.91 ha, which constitutes a −23.127% decrease. Lastly, agricultural land use experienced a sharp decline of 2553.84 hectares, decreasing from 4633.29 ha to 2079.45 ha, amounting to a −55.119% reduction in its initial area. Changes and their magnitudes between land cover around the 5 km buffer classes can also be observed (Figure 10).

Table 8.

Change Analysis (ha) from 1990 to 2020 in the La Madera Subregion with 5 km buffer.

Figure 10.

Land cover change flows between 1990 and 2020 in the La Madera fraction considering the influence area. The width of the bands represents the magnitude of each change, with the bars on the left showing the proportion of cover types in 1990 and those on the right representing 2020.

The results of the present study reveal significant transformations that occurred in just 30 years. In the Los Ajos section, scrubland cover increased by 1322.64 ha (a 1305.15% relative change) within the reserve boundary and by 18,629.10 ha (a 161.82% relative change) in the 5 km buffer zone, while oak forest cover increased by 960.57 ha (a 11.03% relative change) within the reserve limits and by 2331.09 ha (a 9.65% relative change) in the buffer area. In contrast, in the La Madera section, scrubland increased by 1420.74 ha (a 2.31% relative change) within the protected area and 7493.04 ha (a 6.54% relative change) in its surrounding buffer. While grasslands decreased significantly by 2239.65 ha (a −52.55% relative change) and 19,909.53 ha (a −59.17% relative change) in Los Ajos, and by 1486.98 ha (a −10.98% relative change) in the reserve and 7167.06 ha (a −23.12% relative change) in the buffer zone. This marked difference is mainly explained by the initial conditions of each area and their distinct topographic characteristics. While Los Ajos was originally dominated by typical mountain communities such as grasslands, pine forests, and oak woodlands, La Madera was already largely covered by scrubland. Therefore, woody vegetation expansion was more intense in areas previously occupied by vegetation types more susceptible to replacement.

Our results are consistent with previous studies conducted in ecologically similar sites, where the expansion of woody species into ecosystems formerly dominated by grasses has been reported [,]. In North America, the rates of woody vegetation expansion vary across ecoregions, ranging from 0.1% to 2.3% cover per year []. Specifically, in the Great Plains region, an annual increase of 1–2% in woody species cover has been documented []. In particular, the progressive degradation of grasslands in the Madrean Archipelago, where the present study site is located, has been widely documented [,]. Recent estimates indicate that approximately 3.5 million hectares (84.1%) of the historical grasslands in the Arizona and New Mexico portion of the Apache Highlands Ecoregion have already undergone varying degrees of woody encroachment [].

On the other hand, the results show that both within the boundaries of the Los Ajos sector and in the surrounding 5 km buffer zone, there was a reduction in pine forest cover and a concurrent expansion of oak forest. This pattern has also been noted in previous studies [,,], including in nearby regions such as the Sky Islands of Arizona []. According to Alfaro-Reyna et al. [], temperate forests have undergone rapid changes in recent decades, with a directional increase in the abundance of Fagaceae species at the expense of Pinaceae. This trend has been primarily attributed to rising temperatures and the prolongation of drought periods. Pinaceae species are adapted to cold climates due to the anatomy of their wood (narrow-diameter xylem resistant to freeze–thaw cycles), as well as their leaf morphology and photosynthetic physiology. In contrast, many Fagaceae species are better suited to warmer conditions and exhibit less strict stomatal control, allowing them to sustain high transpiration rates during droughts []. Moreover, the replacement of pine-dominated forests by oak shrublands and grasslands has been documented following several high-severity wildfires over the past two decades [,,].

In contrast to what is commonly observed in arid and semi-arid landscapes, where water bodies and their associated vegetation typically diminish due to human or climatic pressures, a significant expansion of gallery vegetation was documented in the La Madera region during the analyzed period. According to Huang et al. [], intermittent drainages (arroyos) receive precipitation inputs in the form of runoff from neighboring and upslope areas. These precipitation inputs render arroyo environments more mesic than other landforms, enabling greater scrub cover and biomass.

Developing metrics to assess parameters measured or address conservation effectiveness, using remote sensing tools, has the potential to greatly improve management decisions. Most likely, these metrics would reflect the progression of land cover and vegetation response to state variables []. The current study explores the development of these tools by addressing vegetation processes (timing vegetation response) as a consequence of cover change.

Future research regarding land cover distribution in remote PNA sites might benefit from higher spatial resolution datasets to address shifts in recent decades. However, historical reconstructions using these datasets might be challenging since imagery legacies might cover a considerably shorter timespan than the Landsat missions. On the same note, it would be desirable to build up location datasets (basic georeferenced records) for land cover class presence over time in order to develop a robust training dataset for supervised classifications.

3.2. Changes in Phenology

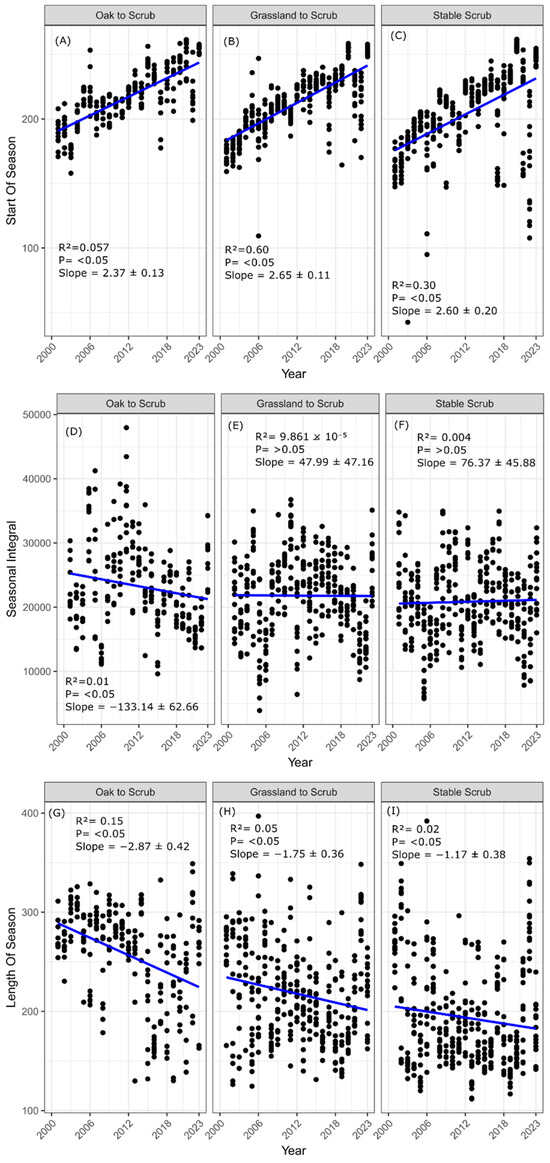

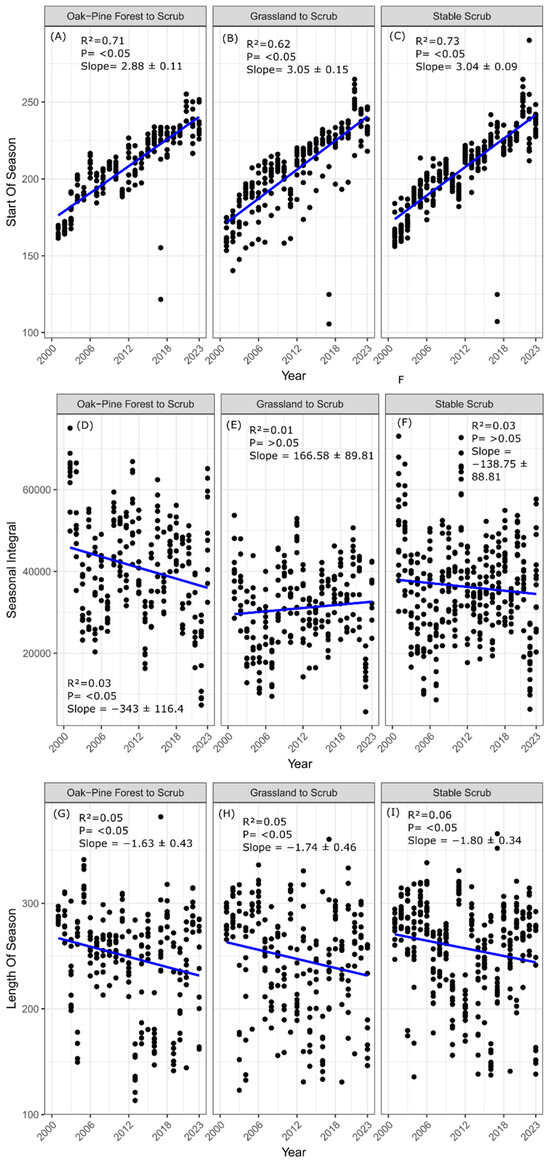

We analyzed 24 years of trends (from 2000 to 2023) of key phenophases for study sites where woody vegetation substituted other land cover types. Specifically, we observed the length and start of the season and the seasonal minor integral for the three selected land cover types in the Los Ajos and La Madera fraction. Regarding the start of the season (SOS), our analysis suggests that in the Los Ajos area (Figure 11), the transition from Oak to Scrub (Figure 11A) exhibited a significant delay in the start of the season, with an average increase of 2.37 days per year (R2 = 0.5791, p < 0.001). In the transition from Grassland to Scrub (Figure 11B), the delay was even more pronounced, with an increase of 2.66 days per year (R2 = 0.6002, p < 0.001). Finally, stable scrublands (Figure 11C) also showed a delay in the start of the season, with an increase of 2.61 days per year, although with a lower explanatory power (R2 = 0.3087, p < 0.001). Similarly to Los Ajos, La Madera also shows a significant delay in the start of the season for all three transition types (Figure 12). Oak-Pine to Scrub transitions (Figure 12A) suggests a delay of 2.89 days per year at SOS (R2 = 0.7198, p < 0.001). The transition from Grassland to Scrub (Figure 12B) showed the greatest delay, with an increase of 3.06 days per year (R2 = 0.6246, p < 0.001). Finally, Stable Scrub (Figure 12C) shows a delay of approximately 3.04 days per year (R2 = 0.7336, p < 0.001).

Figure 11.

Linear regressions for the phenophases: start of season (SOS), length of season (LOS), and seasonal integral (Minor Integral) in Los Ajos, across three land cover transitions: oak to scrub, grassland to scrub, and stable scrub. The X-axis shows the years (2000–2023), while the Y-axis represents Julian days for SOS and LOS and IM × 10,000 for the seasonal integral.

Figure 12.

Linear regressions for the phenophases: start of season (SOS), length of season (LOS), and seasonal integral (Minor Integral) in La Madera, across three land cover transitions: oak-pine to scrub, grassland to scrub, and stable scrub. The X-axis shows the years (2000–2023), while the Y-axis represents Julian days for SOS and LOS and IM × 10,000 for the seasonal integral.

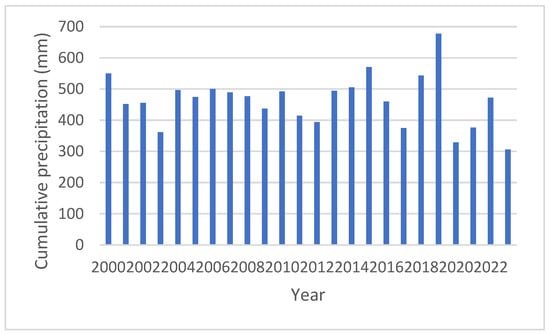

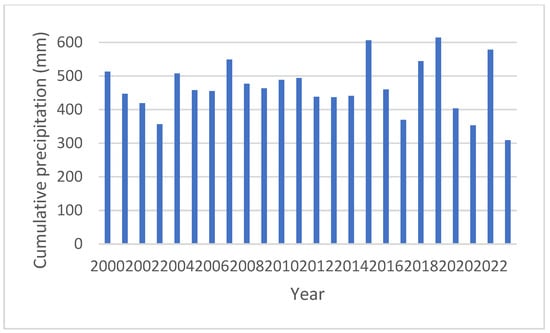

One of the most significant findings of this study is observed in the phenophase of the SOS. It was significantly later in both the Los Ajos and La Madera fractions, a pattern that has also been observed in regions of North America []. Estimates of the SOS are often linked to the timing and intensity of precipitation (Figure 13 and Figure 14), making their detection highly sensitive to atmospheric conditions and rapid vegetation responses []. Building on the work of Crimmins et al. [], an increase of between 2 and 6 °C in temperatures is projected for the arid southwestern United States by the year 2100, accompanied by a decrease in total precipitation, particularly in winter and spring, as well as an increase in the frequency of extreme climatic events such as droughts, heavy rains, and heat waves. Although earlier spring flowering of woody species in lowland areas associated with warming has been documented in the Sonoran Desert, little is yet known about the response of other life forms, especially those inhabiting higher elevations and facing drier conditions. Finally, the authors warn that if autumn rains do not reach the minimum moisture thresholds required to trigger flowering, some species may not flower at all during the following spring, as has been observed in Finger Rock Canyon after particularly dry autumns and winters.

Figure 13.

Cumulative precipitation (mm) in the Ajos area during the period 2000–2023.

Figure 14.

Cumulative precipitation (mm) in the La Madera area during the period 2000–2023.

Regarding the length of season (LOS), for the Los Ajos fraction, significant differences were observed across all three land cover categories (Figure 11). The transition from oak to scrub (Figure 11G) shows a season length shortened by 2.8 days per year (R2 = 0.1591, p < 0.05). In the transition from grassland to scrub (Figure 11H), the decrease was 1.7 days per year (R2 = 0.05885, p < 0.05). Lastly, in stable scrubland (Figure 11I), the season length decreased by 1.17 days per year (R2 = 0.02199, p < 0.05). Similarly to Los Ajos, La Madera also shows significant differences for all the cases analyzed (Figure 12). In the transition from oak-pine to scrub (Figure 12G), the season length decreased by 1.6 days per year, (R2 = 0.05185, p < 0.05). In the grassland-to-scrub transition (Figure 12H), the reduction was 1.74 days per year (R2 = 0.05189, p < 0.05). Finally, stable scrub (Figure 12I) exhibited a decrease of 1.80 days per year (R2 = 0.06924, p < 0.05).

Regarding the small integral analyses, tightly linked to productivity (Figure 11D–F and Figure 12D–F) significant changes were only observed in the transition from oak to scrub in the Los Ajos area (Figure 11D), where productivity in later years decreased (R2 = 0.7198, p < 0.05). In the La Madera area, significant changes were only detected in the transition from oak-pine to scrub (Figure 12D), where once again productivity declined in later years (R2 = 0.3116, p < 0.05). According to [], the life cycle of scrubs follows a seasonal time scale, whereas oaks function on an annual time scale. Consequently, the replacement of oak forest by scrubs leads to a decrease in seasonal productivity as the continuous activity associated with oak cover is lost.

The convergence in productivity and season length may be related, according to Crimmins et al. [], to the phenological strategies of woody species, which tend to exhibit more synchronized flowering both at the individual and community levels. In contrast to perennial herbaceous species, which respond more opportunistically and asynchronously to rainfall pulses, woody plants display more stable phenological patterns, likely due to their ability to access deeper groundwater sources []. This greater phenological stability could explain the lower interpatch variability observed in certain parameters. Various studies have shown that the effects of shrub encroachment on aboveground net primary productivity (ANPP) are complex and context-dependent []. Although declines in productivity have been documented in arid regions, these trends are not universal. For example, the expansion of Juniperus virginiana into low-elevation grasslands and scrublands in the western United States has been associated with increases in ecosystem net productivity, as well as changes in the distribution and quantity of carbon and nitrogen in both soil and vegetation [,]. Therefore, the study of complex dynamics regarding transitions to woody vegetation should be addressed at multiple spatiotemporal scales. At the landscape level, the quantification of the increase/decrease in woody vegetation, as well as the changes in ecosystem function posed by it, are key components to analyze encroachment. The current study focuses only on phenological changes as a consequence of woody vegetation transitions. However, given the results reached in this work, a regional assessment of phenological trends could further our understanding of climatic shifts on all land cover types in the region.

4. Conclusions

The present study reveals a clear trend of grassland and oak forest ecosystems transitioning into woody vegetation across much of the FFPA Bavispe, a pattern evident in both the Los Ajos and La Madera sections as well as in surrounding areas. Woody encroachment is more pronounced within the 5 km buffer zones than inside the protected areas themselves. Phenological patterns vary depending on vegetation type and location, with additional dynamics including the replacement of pine forests by oak woodlands in Los Ajos, a decline in agricultural land, and the expansion of riparian vegetation in La Madera. Phenological differences among areas may be influenced by factors not deeply explored in this study, such as microclimates, moisture availability, and photoperiod. Remote sensing proves to be a key tool for understanding long-term landscape change, providing valuable information for protected area managers by identifying zones that may require greater attention and offering an efficient alternative to field-based methods, particularly in hard-to-reach areas. However, the study of Sky Islands remains challenging due to their high complexity and landscape heterogeneity; future research should account for this complexity and the transition zones by applying diverse algorithms and multi-resolution imagery, while also incorporating underlying ecological drivers within and around the reserve (e.g., drought, livestock grazing, wildfires). Likewise, the consequences of phenological variation for biodiversity and natural cycles (such as carbon cycling) require detailed analyses to increase our understanding of regional and local factors controlling these processes. Ultimately, effective management of Natural Protected Areas will benefit from the continued development of novel approaches to quantify land cover change and identify its human and natural drivers.

Author Contributions

Contributions: A.F.-N. contributed to conceptualization, study design, and writing of the original draft. J.R.R.-L. contributed to conceptualization, review, experimental and methodological design, and supervision. C.H.-H. contributed to methodological design, conceptualization, data processing, and review. A.C.-V. and A.M.-D. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, and manuscript review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI), providing financial support to pursue graduate studies. Also founding was received form grant USO313008559-University of Sonora. The APC was funded by University of Sonora.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

AFN would like to thank CONANP for the continuous support in the project, the Posgrado en Biociencias at Universidad de Sonora for its constant support throughout this work, and the Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI) for the financial support provided to pursue graduate studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van Auken, O.W. Causes and consequences of woody plant encroachment into western North American grasslands. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2931–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Wang, G.; Wu, W.; Shrestha, A.; Innes, J.L. Grassland resilience to woody encroachment in North America and the effectiveness of using fire in national parks. Climate 2023, 11, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, G.; Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Xia, W.; Cui, H.; Zhang, A.; An, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Woody plant encroachment significantly alters grassland soil microbial community: A global meta-analysis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2025, 34, e70148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, D.J.; Bowker, M.A.; Maestre, F.T.; Roger, E.; Reynolds, J.F.; Whitford, W.G. Impacts of shrub encroachment on ecosystem structure and functioning: Towards a global synthesis. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner-McGraw, A.P.; Ajami, H. Impact of uncertainty in precipitation forcing data sets on the hydrologic budget of an integrated hydrologic model in mountainous terrain. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2020WR027639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soubry, I.; Guo, X. Earth Observation for Shrub Encroachment. 2024, pp. 1–28. Available online: https://egusphere.copernicus.org/preprints/2024/egusphere-2024-3466/ (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Muñoz-Robles, C.; Reid, N.; Tighe, M.; Briggs, S.V.; Wilson, B. Soil hydrological and erosional responses in areas of woody encroachment, pasture and woodland in semi-arid Australia. J. Arid. Environ. 2011, 75, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, S.R.; Andersen, E.M.; Predick, K.I.; Schwinning, S.; Steidl, R.J.; Woods, S.R. Woody plant encroachment: Causes and consequences. In Rangeland Systems; Briske, D.D., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 25–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, V.L.; Ferreira, M.C.; Costa, L.S.; Amaral, E.d.J.; Bustamante, M.M.d.C.; Munhoz, C.B.R. The effect of woody encroachment on taxonomic and functional diversity and soil properties in Cerrado wetlands. Flora 2024, 316, 152524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarecke, K.M.; Zhang, X.; Keen, R.M.; Dumont, M.; Li, B.; Sadayappan, K.; Moreno, V.; Ajami, H.; Billings, S.A.; Flores, A.N.; et al. Woody encroachment modifies subsurface structure and hydrological function. Ecohydrology 2025, 18, e2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Odorico, P.; Okin, G.S.; Bestelmeyer, B.T. A synthetic review of feedbacks and drivers of shrub encroachment in arid grasslands. Ecohydrology 2012, 5, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, D.J.; Ding, J. Remove or retain: Ecosystem effects of woody encroachment and removal are linked to plant structural and functional traits. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 2637–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gxasheka, M.; Gajana, C.S.; Dlamini, P. The role of topographic and soil factors on woody plant encroachment in mountainous rangelands: A mini literature review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Körner, C.; Muraoka, H.; Piao, S.; Shen, M.; Thackeray, S.J.; Yang, X. Emerging opportunities and challenges in phenology: A review. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparros-Santiago, J.A.; Rodríguez Galiano, V.; Dash, J. Land surface phenology as indicator of global terrestrial ecosystem dynamics: A systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 171, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, N.; Liu, L.; Cao, R.; Yang, W.; Zhu, X.; Wang, C.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; et al. Challenges in remote sensing of vegetation phenology. Innov. Geosci. 2024, 2, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skhosana, F.V.; Stevens, N.; Maoela, M.A.; Archibald, S.; Midgley, G.F. The impacts of woody encroachment on nature’s contributions to people in North America and Africa: A systematic review. People Nat. 2025, 7, 2585–2601. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G. Land Surface Phenology as an Indicator of Performance of Conservation Policies like Natura 2000. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huete, A.R.; Justice, C.; van Leeuwen, W.J.D. MODIS Vegetation Index (MOD13) Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document, Version 3.0; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 1999.

- Dronova, I.; Taddeo, S. Remote sensing of phenology: Towards comprehensive indicators of plant community dynamics from species to regional scales. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 1460–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, N.; Bond, W.; Feurdean, A.; Lehmann, C.E. Grassy ecosystems in the Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Eldridge, D.J. Woody encroachment: Social–ecological impacts and sustainable management. Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 1909–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontifes, P.A.; García-Meneses, P.M.; Gómez-Aíza, L.; Monterroso-Rivas, A.I.; Caso-Chávez, M. Land use/land cover change and extreme climatic events in the arid and semi-arid ecoregions of Mexico. Atmosfera 2018, 31, 355–372. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado-Guerra, P.; Velázquez-Martínez, M.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, R.A.; Álvarez-Holguín, A.; Domínguez-Martínez, P.A.; Gutiérrez-Luna, R.; Garza-Cedillo, R.D.; Luna-Luna, M.; Chávez-Ruiz, M.G. The grasslands and scrublands of arid and semi-arid zones of Mexico: Current status, challenges and perspectives. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2021, 12, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lei, H.; Duan, L. Resistance of grassland productivity to drought and heatwave over a temperate semi-arid climate zone. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Sierra, C.L.; Sosa Ramírez, J.; Cortés Calva, P.; Solís Cámara, A.B.; Íñiguez Dávalos, L.I.; Ortega Rubio, A. México país megadiverso y la relevancia de las áreas naturales protegidas. Investig. Cienc. Univ. Autón. Aguascalientes 2014, 22, 16–22. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/674/67431160003.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Sahagún-Sánchez, F.J.; Reyes-Hernández, H. Impactos por cambio de uso de suelo en las áreas naturales protegidas de la región central de la Sierra Madre Oriental, México. CienciaUAT 2018, 12, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP). Estudio Previo Justificativo PARA dotar con la Categoría de Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna el Área Natural Protegida Competencia de la Federación la Reserva Forestal Nacional y Refugio de Fauna Silvestre Bavispe [Technical Draft]; CONANP: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maass, M.; Jardel, E.; Martínez-Yrízar, A.; Calderón, L.; Herrera, J.; Castillo, A.; Euán-Ávila, J.; Equihua, M. Las áreas naturales protegidas y la investigación ecológica de largo plazo en México. Ecosistemas 2010, 19, 69–83. Available online: http://www.revistaecosistemas.net/index.php/ecosistemas/article/view/47 (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Gaceta Parlamentaria. Con Punto de Acuerdo, por el que se Exhorta a la SEMARNAT a Realizar por la CONANP Acciones Para Recategorizar Como Área Natural Protegida la Reserva Forestal Nacional y Refugio de la Fauna Silvestre Bavispe, en Sonora; Gaceta Parlamentaria: Mexico City, Mexico, 2016; Volume XIX, pp. 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Valenzuela, J.G.; Montañez-Armenta, M.P.; Silva-Kurumiya, H.; Yanes-Arvayo, G. Breve recuento de fauna en el predio El Corralito, municipio de Moctezuma, Sonora. In Proceedings of the Collaboration Now for the Future: IV Conference on the Biodiversity and Management of the Madrean Archipelago, Tucson, AZ, USA, 14–18 May 2018; Proceedings RMRS-P-79. Neary, D.G., Gottfried, G.J., Eds.; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2022; pp. 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins, T.M.; Bertelsen, C.D.; Crimmins, M.A. Within-season flowering interruptions are common in the water-limited Sky Islands. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014, 58, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Villegas, A.E.; Bravo, L.C.; Koch, G.W.; Llano, J.; López, D.; Méndez, R.; Rodríguez, J.C.; Romo, R.; Sisk, T.D.; Yanes-Arvayo, G. Impactos ecológicos por el uso del terreno en el funcionamiento de ecosistemas áridos y semiáridos. In Diversidad Biológica de Sonora; Mora-Cantua Editores: Hermosillo, Mexico, 2010; pp. 157–186. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, P.S.; Roy, A. Land use and land cover change in India: A remote sensing & GIS perspective. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2010, 90, 489–502. [Google Scholar]

- Romo-León, J.R.; van Leeuwen, W.J.D.; Castellanos Villegas, A.E. Percepción remota para el análisis de la distribución y cambios de uso de suelo en zonas áridas y semiáridas. In Dinámicas Locales del Cambio Ambiental Global; Sánchez Flores, É., Díaz Caravantes, R.E., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez: Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, 2013; pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Belenok, V.; Noszczyk, T.; Hebryn-Baidy, L.; Kryachok, S. Investigating anthropogenically transformed landscapes with remote sensing. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 24, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Guía Para la Interpretación de Cartografía: Uso del Suelo y Vegetación Escala 1:250,000; Serie V; INEGI: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- García, E. Modificaciones al Sistema de Clasificación Climática de Köppen: Para Adaptarlo a las Condiciones de la República Mexicana, 2nd ed.; UNAM, Instituto de Geografía: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004; ISBN 9703210104. [Google Scholar]

- Meghraj, K.C.; Leigh, L.; Pinto, C.T.; Kaewmanee, M. Method of validating satellite surface reflectance product using empirical line method. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2240. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, S.; Singh, R. A comprehensive review on land use/land cover (LULC) change modeling for urban development: Current status and future prospects. Sustainability 2023, 15, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.H.; Abbasi, H.; Karas, I.R. A review on change detection method and accuracy assessment for land use land cover. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 22, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derdour, A.; Jodar-Abellan, A.; Melian-Navarro, A.; Bailey, R. Assessment of land degradation and droughts in an arid area using drought indices, modified soil-adjusted vegetation index, and Landsat remote sensing data. Geogr. Res. Lett. 2023, 49, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, W.J.D.; Huete, A.R.; Laing, T.W. MODIS vegetation index compositing approach: A prototype with AVHRR data. Remote Sens. Environ. 1999, 69, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.B.; Woodcock, C.E. An assessment of several linear change detection techniques for mapping forest mortality using multitemporal Landsat TM data. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 56, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.; Ledrew, E. Application of principal components analysis to change detection. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1987, 53, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Bilucan, F.; Kavzoglu, T. The effect of auxiliary data (slope, aspect and elevation) on land use/land cover classification accuracy of Sentinel-2A image using random forest classifier. In Proceedings of the 2nd Intercontinental Geoinformation Days (IGD), Mersin, Turkey, 5–6 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.R.; Hardy, E.E.; Roach, J.T.; Witmer, R.E. A Land Use and Land Cover Classification System for Use with Remote Sensor Data; Geological Survey Professional Paper; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1976. [CrossRef]

- Dennise-Pacheco, S. Análisis Espacio-Temporal de la Distribución de la Cobertura de Suelo y la Dinámica de la Vegetación en Zonas de Interés para la Conservación en el Centro-Este del Estado de Sonora. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Sonora, Hermosillo, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fida, G.T.; Baatuuwie, B.N.; Issifu, H. Dynamics of Land Use/Cover Change and Its Drivers During 1992–2022 in Yayo Coffee Forest Biosphere Reserve, Southwestern Ethiopia. Sustain. Environ. 2024, 10, 2374119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabad, F.A.; Zare, M.; Solgi, R.; Shojaei, S. Comparison of neural network methods (Fuzzy ARTMAP, Kohonen and Perceptron) and maximum likelihood efficiency in preparation of land use map. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 2199–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, B.; Mather, M.P. Classification Methods for Remotely Sensed Data; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Seyam, M.M.H.; Haque, M.R.; Rahman, M.M. Identifying the land use land cover (LULC) changes using remote sensing and GIS approach: A case study at Bhaluka in Mymensingh, Bangladesh. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 7, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, J. Maximum likelihood classification of soil remote sensing image based on deep learning. Earth Sci. Res. J. 2020, 24, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System, Version 3.40.1. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. Open Source Geospatial Foundation: Beaverton, OR, USA, 2024. Available online: https://qgis.org (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Version 4.4.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Esri. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10.5; Environmental Systems Research Institute: Redlands, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eklundh, L.; Jönsson, P. TIMESAT 3.3 with Seasonal Trend Decomposition and Parallel Processing—Software Manual; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, A.; Marjanović, H.; Barcza, Z. Spring vegetation green-up dynamics in Central Europe based on 20-year long MODIS NDVI data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 287, 107969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, A.K.; Romo, J.R.; Castellanos, A.E.; Méndez, R.; Gandarilla, F.J. Análisis espacial del cambio de cobertura/uso del suelo asociados a pastos exóticos en La Sierra Libre, Sonora. Biotecnia 2019, 21, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayre, N.F. Rangeland degradation and restoration in the “Desert Seas”: Social and economic drivers of ecological change between the Sky Islands. In Connecting Mountain Islands and Desert Seas: Biodiversity and Management of the Madrean Archipelago II; Proc. RMRS-P-36; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2005; pp. 349–353. [Google Scholar]

- Gori, D.F.; Enquist, C.A.F. An Assessment of the Spatial Extent and Condition of Grasslands in Central and Southern Arizona, Southwestern New Mexico and Northern Mexico; The Nature Conservancy, Arizona Chapter: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2003; 28p, Available online: http://azconservation.org/dl/TNCAZ_Grasslands_Assessment_Report.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Alfaro Reyna, T.; Retana, J.; Martínez-Vilalta, J. Is there a substitution of Pinaceae by Fagaceae in temperate forests at the global scale? Glob. Planet. Change 2018, 166, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro Reyna, T.; Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Retana, J. Regeneration patterns in Mexican pine-oak forests. For. Ecosyst. 2019, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Reyna, T.; Retana, J.; Arasa-Gisbert, R.; Vayreda, J.; Martínez-Vilalta, J. Recent dynamics of pine and oak forests in Mexico. Eur. J. For. Res. 2020, 139, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, A.M.; Poulos, H.M. Pine vs. oaks revisited: Conversion of Madrean pine-oak forest to oak shrubland after high-severity wildfire in the Sky Islands of Arizona. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 414, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shive, K.L.; Kuenzi, A.M.; Sieg, C.H.; Fulé, P.Z. Pre-fire fuel reduction treatments influence plant communities and exotic species 9 years after a large wildfire. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2013, 16, 457–469. [Google Scholar]

- Coop, J.D.; Parks, S.A.; Stevens-Rumann, C.S.; Crausbay, S.D.; Higuera, P.E.; Hurteau, M.D.; Tepley, A.; Whitman, E.; Assal, T.; Collins, B.M.; et al. Wildfire-driven forest conversion in Western North American landscapes. BioScience 2020, 70, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Archer, S.R.; McClaran, M.P.; Marsh, S.E. Shrub encroachment into grasslands: End of an era? PeerJ 2018, 6, e5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.R.S.; Rosa, M.R.; de Vasconcelos, R.N. Evaluating the effectiveness of protected areas in preserving ecosystem processes via remote sensing: A review. J. Nat. Conserv. 2025, 87, 127002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, X.; Wang, M. Detection and attribution of the start of the growing season changes in the Northern Hemisphere. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, A.C.; Srivastava, A.; Ganem, K.A.; Arai, E.; Huete, A.; Shimabukuro, Y.E. Remote sensing-based phenology of dryland vegetation: Contributions and perspectives in the Southern Hemisphere. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.J.; Baumann, M.; Esgalhado, C. Drivers of productivity trends in cork oak woodlands over the last 15 years. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, H.J.; Jackson, R.B. Rooting depths, lateral root spreads and below ground/above ground allometries of plants in water-limited ecosystems. J. Ecol. 2002, 90, 480–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, D.C.; Blair, J.M. Woody plant encroachment by Juniperus virginiana in a mesic native grassland promotes rapid carbon and nitrogen accrual. Ecosystems 2008, 11, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).