Anthropogenic Disturbance Factors in the Ouémé Supérieur Classified Forest in Northern Benin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methodology

- Frequency: proportion of plots affected,

- Spatial structure: variation in disturbance with increasing penetration distance,

3. Results

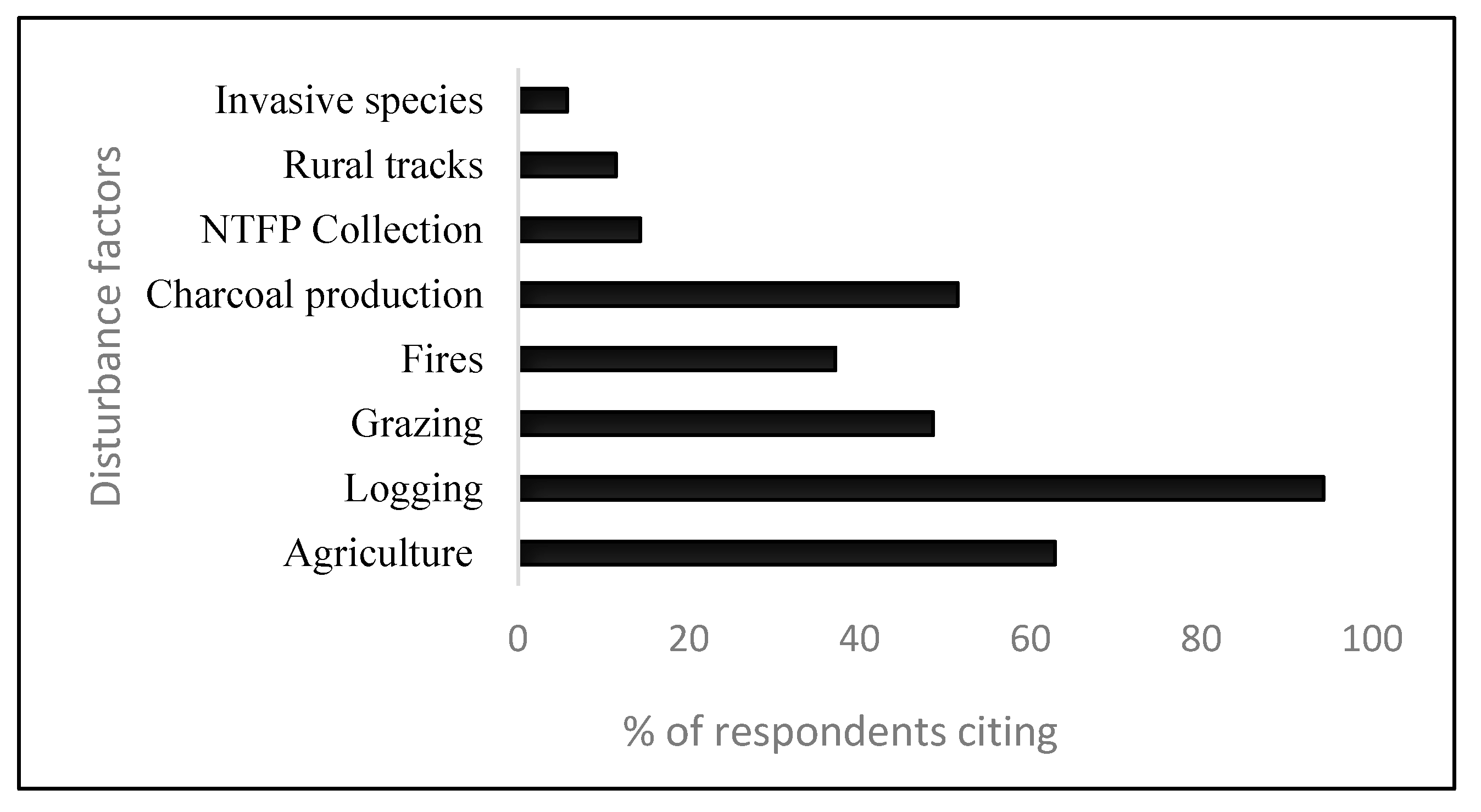

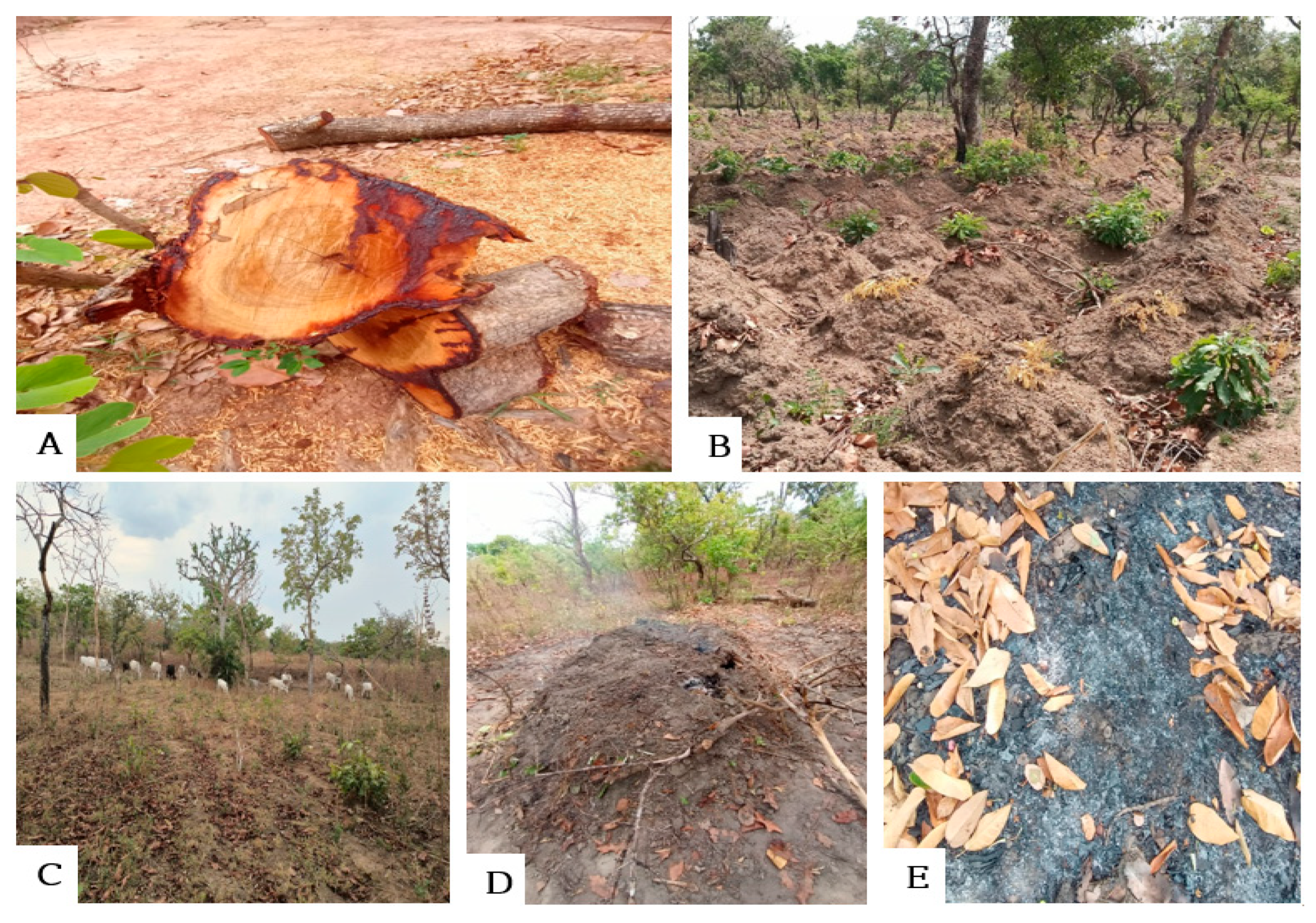

3.1. Anthropogenic Disturbances Disrupting the Ouémé Supérieur Classified Forest

- Logging, evidenced by the presence of tree stumps, cut trunks, or trees showing signs of coppicing (regrowth from felled trees);

- Agricultural expansion, indicated by the presence of active cultivated plots or fallow land within the forest boundaries;

- Charcoal production, marked by visible charcoal mounds, abandoned kilns, or ash residues;

- Grazing pressure, revealed by the presence of livestock droppings, particularly cow dung, often concentrated near forest entry points;

- Vegetation fires, identified by burnt vegetation, charred tree trunks, and blackened soil surfaces.

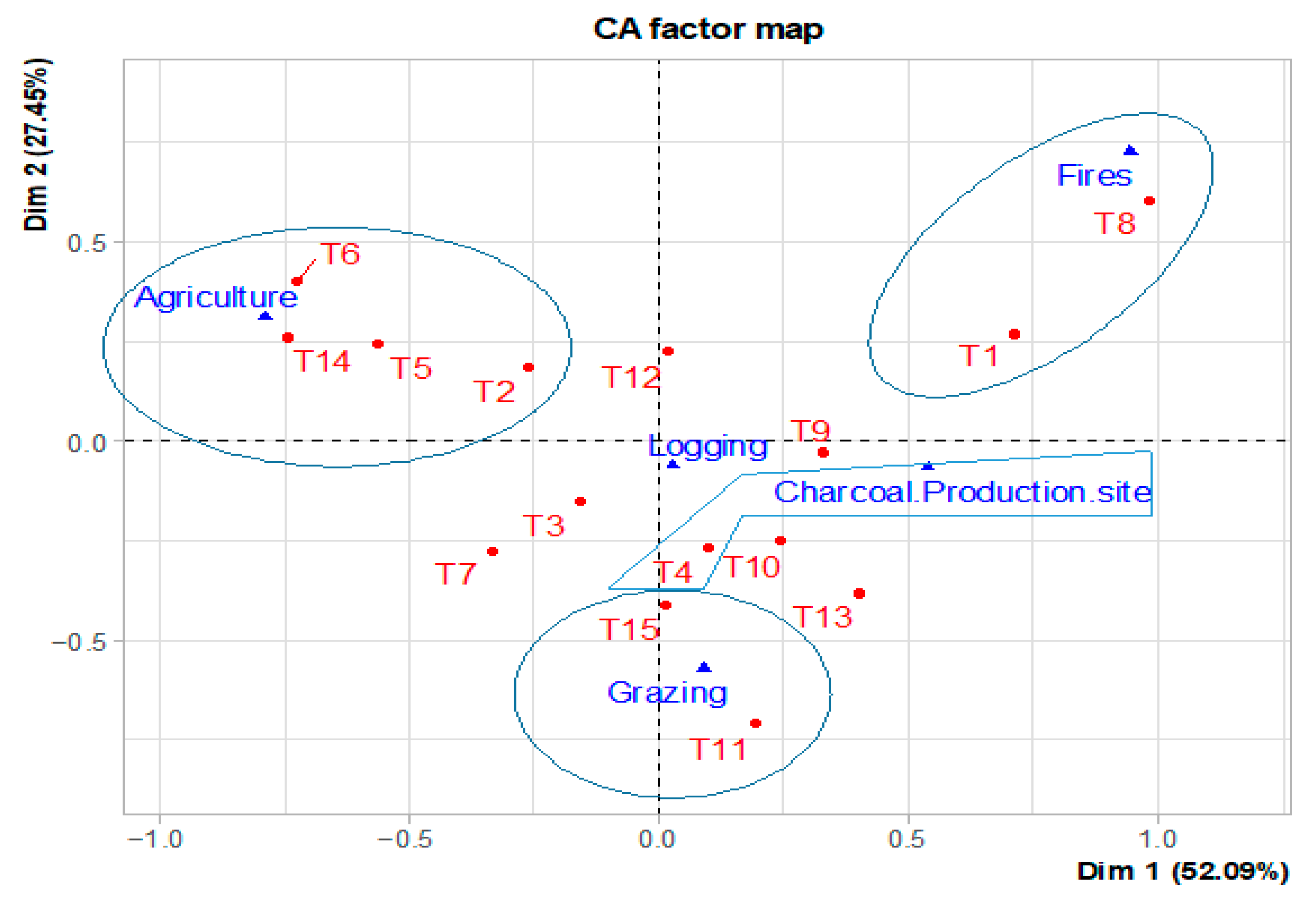

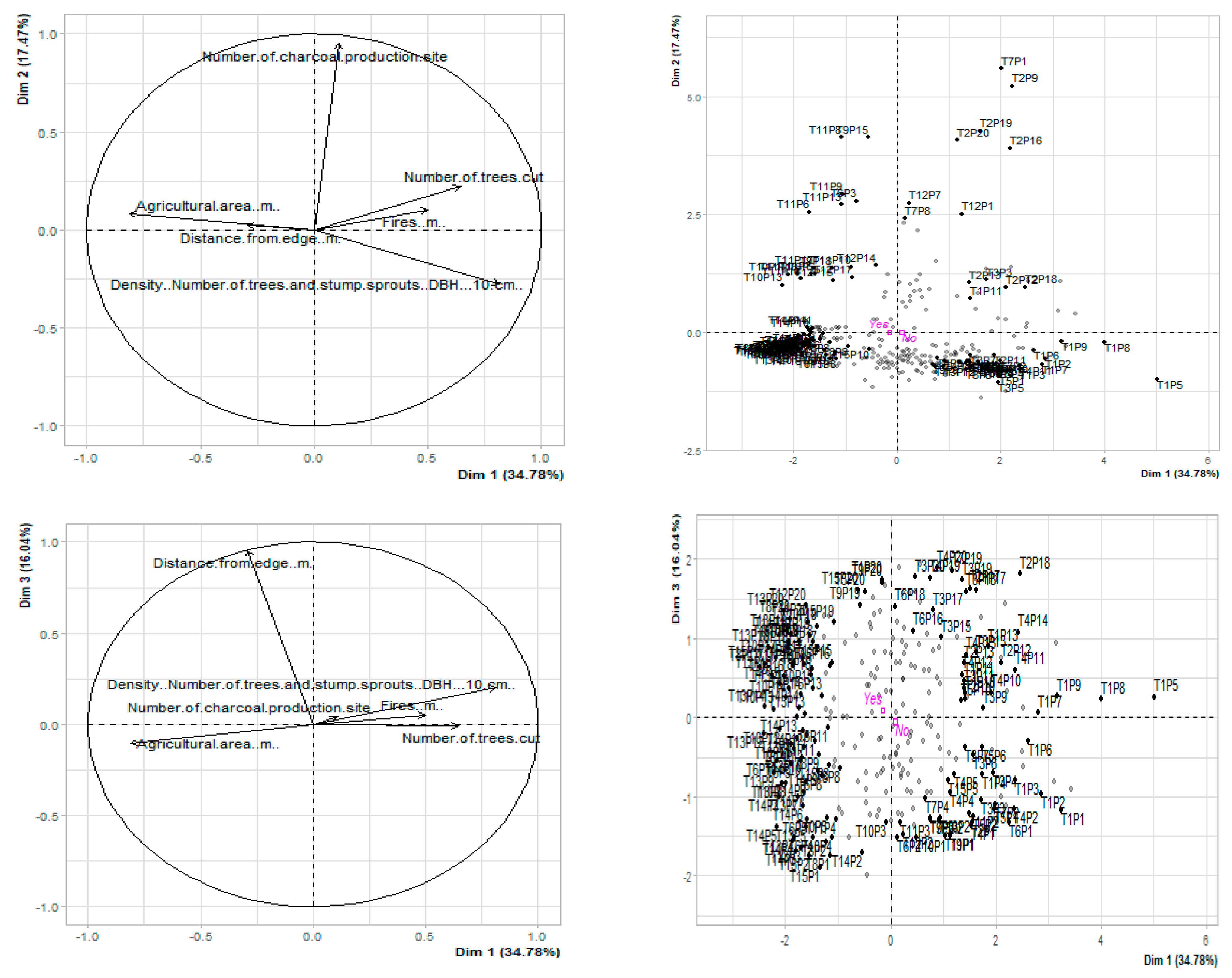

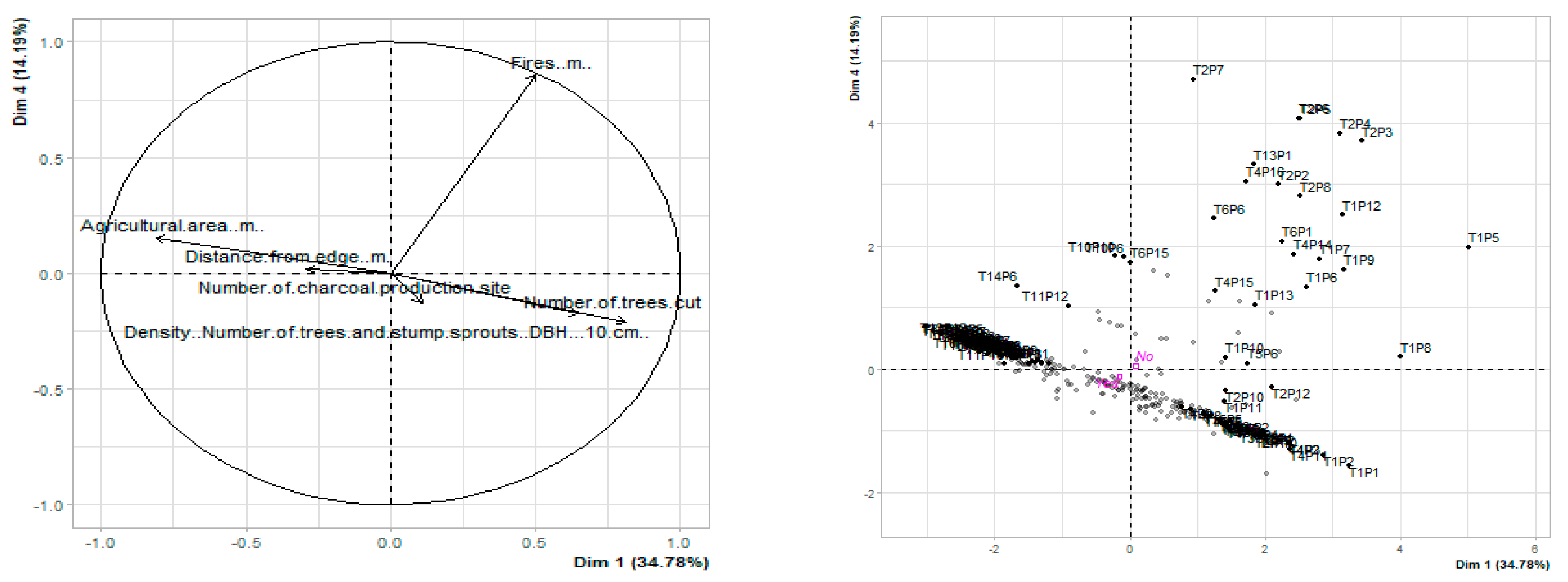

3.2. Distribution and Structuring of Anthropogenic Disturbancesin the Ouémé Supérieur Classified Forest

- Axis 1 showed a strong positive correlation with density of trees with a diameter greater than 10 cm, and a negative correlation with the agricultural area observed per plot. This axis highlighted a contrast between plots characterized by extensive agricultural activity but low tree density (transects T10, T13, T14), and those with low agriculture area but high trees density (transects T1 and T2).

- Axis 2 was positively correlated with the number of charcoal production sites. This axis distinguished transects with low charcoal activity (e.g., T3, T8) from those with intensive charcoal production (e.g., T11, T12), revealing localized zones of energy-resource extraction.

- Axis 3 captured the gradient of forest penetration, clearly separating plots near entry points from those deeper into the forest. This component is critical for understanding the spatial behavior of disturbances factors in relation to forest accessibility.

- Axis 4 was positively associated with the area affected by vegetation fires, distinguishing heavily burned plots from less-impacted ones.

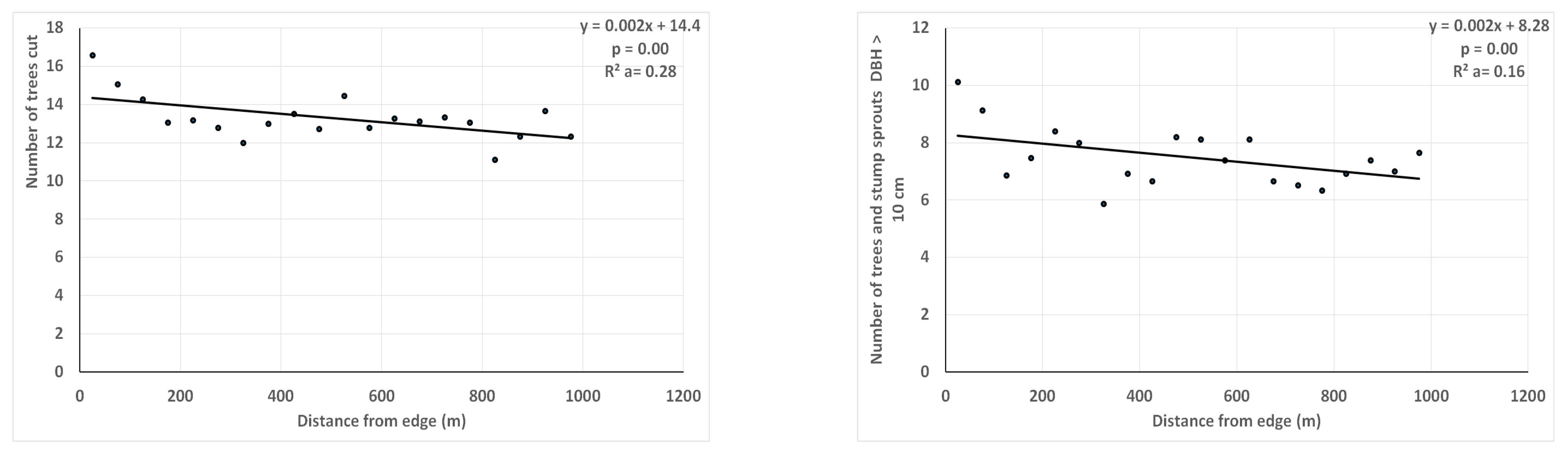

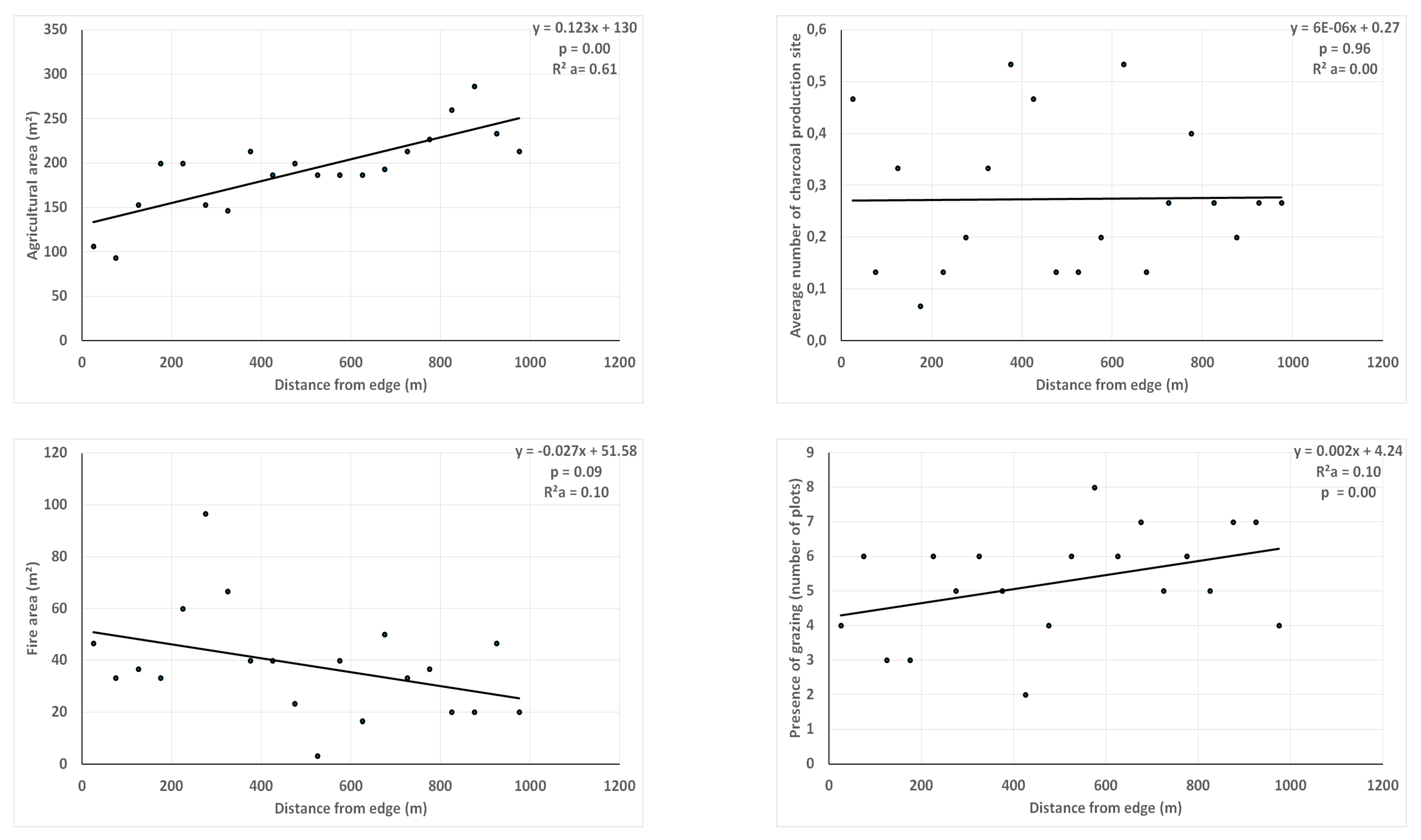

3.3. Linear Trend in Disturbances According to the Distance from Edge to the Interior of the Forest

3.4. Association Between Different Disturbances in the Ouémé Supérieur Classified Forest

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodology

4.2. Spatial Distribution of Different Types of Disturbance in the Ouémé Supérieur Classified Forest

4.3. Implications for Forest Conservation and Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meyfroidt, P.; Lambin, E.F. The Causes of the Reforestation in Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2007, 25, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupala, Z.J.; Lusambo, L.P.; Ngaga, Y.M.; Makatta, A.A. The Land Use and Cover Change in Miombo Woodlands under Community Based Forest Management and Its Implication to Climate Change Mitigation: A Case of Southern Highlands of Tanzania. Int. J. For. Res. 2015, 2015, 459102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muluneh, A.; van Loon, E.; Bewket, W.; Keesstra, S.; Stroosnijder, L.; Burka, A. Effects of Long-Term Deforestation and Remnant Forests on Rainfall and Temperature in the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia. For. Ecosyst. 2017, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Rapport Principal: Evaluation Des Ressources Forestières Mondiales 2010; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010; ISBN 978-92-5-206654-5. ISSN 1014-2894. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, S.; Fuller, R.; Brooks, T.; Watson, J. The Ravages of Guns, Nets and Bulldozers. Nature 2016, 536, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traore, L.; Ouedraogo, I.; Ouedraogo, A.; Thiombiano, A. Perceptions, Usages et Vulnérabilité Des Ressources Végétales Ligneuses Dans Le Sud-Ouest Du Burkina Faso. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2011, 5, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbayngone, E.; Thiombiano, A.; Hahn-Hadjali, K.; Guinko, S. Caractéristiques Écologiques de La Végétation Ligneuse Du Sud-Est Du Burkina Faso (Afrique de l’Ouest): Le Cas de La Réserve de Pama. Candollea 2008, 63, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bindaoudou, I.A.; Kone, I.Z.; Mansir, M.; Djari, S.; Kouame, K.F. Facteurs Explicatifs de La Déforestation et de La Dégradation Forestière Dans La Préfecture d’ Amou Au Sud—Ouest Du Togo. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Invent. 2022, 11, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musavandalo, C.M.; Essouman, P.F.E.; Ndjadi, S.S.; Balandi, J.B.; Nguba, T.B.; Sodalo, C.; Mweru, J.P.M.; Sambieni, K.R.; Bogaert, J. Anthropogenic Disturbances in Northwestern Virunga Forest Amid Armed Conflict. Land 2025, 14, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotondrasoa, O.L.; Ayral, A.; Stein, J.; Rajoelison, G.L.; Ponette, Q.; Malaisse, F.; Ramamonjisoa, B.S.; Raminosoa, N.; Verheggen, F.J.; Poncelet, M.; et al. Analyse Des Facteurs Anthropiques de Dégradation Des Bois de Tapia (Uapaca Bojeri) d’Arivonimamo. In Les Vers à Soie Malgaches. ENJEUX Écologiques et Socio-Économiques; Verheggen, F., Bogaert, J., Haubruge, É., Eds.; Les Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgium, 2013; ISBN 978-2-87016-128-9. [Google Scholar]

- Geist, H.J.; Lambin, E.F. Proximate Causes and Underlying Driving Forces of Tropical Deforestation. Bioscience 2002, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alohou, C.E.; Ouinsavi, C.; Sokpon, N. Facteurs Déterminants de La Fragmentation Du Bloc Forêt Classée-Forêts Sacrées Au Sud-Bénin. J. Appl. Biosci. 2016, 101, 9618–9633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houessou, L.G.; Teka, O.; Toko, I.; Lykke, A.M.; Sinsin, B. Land Use and Land-Cover Change at “W” Biosphere Reserve and Its Surroundings Areas in Benin Republic (West Africa). Environ. Nat. Resour. Res. 2013, 3, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; James, E., Douglass, C., Eds.; Political; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Nagendra, H. Insights on Linking Forests, Trees, and People from the Air, on the Ground, and in the Laboratory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19224–19231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter-Bolland, L.; Ellis, E.A.; Guariguata, M.R.; Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Negrete-Yankelevitch, S.; Reyes-Garcia, V. Community Managed Forests and Forest Protected Areas: An Assessment of Their Conservation Effectiveness across the Tropics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 268, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Brondizio, E.S., Settele, J., Díaz, S., Ngo, H.T., Eds.; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Bonn, Germany, 2019; ISBN 9783947851201. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. La Situation Des Forêts Du Monde. Les Forêts Au Service Du Developpement Durable; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; ISBN 9789251324202. [Google Scholar]

- Hountondji, Y.; Sokpon, N.; Nicolas, J.; Ozer, P. Ongoing Desertification Processes in the Sahelian Belt of West Africa: An Evidence from the Rain-Use Efficiency. In Recent Advances in Remote Sensing and Geoinformation Processing for Land Degradation Assessment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; Volume 27, pp. 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imorou, I.T.; Arouna, O.; Zakari, S.; Djaouga, M.; Thomas, O.; Kinmadon, G.; Imorou, I.T.; Arouna, O.; Zakari, S.; Djaouga, M.; et al. Évaluation de La Déforestation et de La Dégradation Des Forêts Dans Les Aires Protégées et Terroirs Villageois Du Bassin Cotonnier Du Bénin. In Proceedings of the Conférence OSFACO Des Images Satellitaires pour la Gestion Durable des Territoires en Afrique, Cotonou, Benin, 13–15 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Forests 2020: Forests, Biodiversity and People. In Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oloukoi, J.; Joseph, V.; Bernadin, F. Modélisation de La Dynamique de l’occupation Des Terres Dans Le Département Des Collines Au Bénin. Télédétection 2006, 6, 305–323. [Google Scholar]

- Mama, A.; Sinsin, B.; De Cannière, C.; Bogaert, J. Anthropisation et Dynamique Des Paysages En Zone Soudanienne Au Nord Du Bénin. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Avakoudjo, J.; Mama, A.; Toko, I.; Kindomihou, V.; Sinsin, B. Dynamique de l’occupation Du Sol Dans Le Parc National Du W et Sa Périphérie Au Nord-Ouest Du Bénin. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2014, 8, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoussou, E.; Totin Vodounon, S.H.; Hougni, A.; Vissin, E.W.; Houndenou, C.; Mahe, G.; Boko, M. Changements Environnementaux et Vulnérabilité Des Écosystèmes Dans Le Bassin-Versant Béninois Du Fleuve Niger. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2016, 10, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambieni, K.R.; Toyi, M.S.S.; Mama, A. Perception Paysanne Sur La Fragmentation Du Paysage de La Forêt Classée de l’Ouémé Supérieur Au Nord Du Bénin. VertigO—Rev. Electron. Sci. l’Environ. 2015, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahononga, F.C.; Gouwakinnou, G.N.; Biaou, S.S.H.; Biaou, S. Facteurs Socio-Économiques Expliquant La Déforestation et La Dégradation Des Écosystèmes Dans Les Domaines Soudanien et Soudano-Guinéen Du Bénin. Ann. l’Univ. Parakou. Sér. Sci. Nat. Agron. 2020, 10, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbodan, K.M.L.; Akpavi, S.; Amegnaglo, K.B.; Akodewou, A.; Diwediga, B.; Koda; Donko, K.; Agbodan, K. Connaissances Écologiques Locales Sur Les Indicateurs de Dégradation Des Sols Utilisées Par Les Paysans Dans La Zone Guinéenne Du Togo (Afrique de l’ouest). Sci. La Vie La Terre Agron. 2019, 7, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Franta, B.; Kourdjouak, Y.; Kaboumba, L.-E.M.; Arcilla, N. Sacred Forest Degradation and Conservation: Resident Views of Nakpadjoak Forest in Togo, West Africa. Conservation 2025, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, C.; Fayolle, A.; Bastin, J.F.; Latte, N.; Lejeune, P. Monitoring Selective Logging Intensities in Central Africa with Sentinel-1: A Canopy Disturbance Experiment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 298, 113828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, B.; Decuyper, M.; Verbesselt, J.; Zeileis, A.; Herold, M.; Joseph, S. Tracking Disturbance-Regeneration Dynamics in Tropical Forests Using Structural Change Detection in Time Series of Satellite Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 169, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, F. La Végétation de l’Afrique. In Mémoire Accompagnant La Carte de Végétation de l’Afrique/AETFAT/UNESCO; Traduit de l’anglais Par P. Bamps, Jardin Botanique National de Belgique: Paris, France, 1986; ISBN 9232019558. [Google Scholar]

- Djaouga, M.; Karimou, S.; Arouna, O.; Zakari, S.; Matilo, A.O.; Imorou, I.T.; Yabi, I.; Djego, J.; Thomas, O.; Houssou, C. Cartographie de La Biomasse Forestière et Évaluation Du Carbone Séquestré Dans La Forêt Classée de l’Ouémé Supérieur Au Centre—Bénin. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2022, 15, 2388–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bio Sannou, I.; Imorou, A.-B. La Gouvernance Participative Des Forêts Classées de l’Ouémé Supérieur—N’Dali (Bénin) à l’Epreuve des Logiques et Pratiques des Acteurs; Edition Francophones Universitaires d’Afrique: Cocody, Côte d’Ivoire, 2019; pp. 135–164. [Google Scholar]

- DGFRN. Plan d’Aménagement Participatif des Forêts Classées de L’OUÉMÉ Supérieur et de N’Dali, 2013–2022. 2014. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=http://www.archives.biodiv.be/benin/implementation/lois/politiques-et-plans-d-action/directives-d-amenagement/download/fr-BE/1/Directives%2520d%2527am%25C3%25A9nagement_guide%2520et%2520canevas%2520d%25C3%25A9taill%25C3%25A9-%2520rapport%2520%25C3%25A0%2520d%25C3%25A9poser%2520pdf.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjYtou52OuPAxVTlJUCHeGIGIwQFnoECBYQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1YUQ0TasHWWoisSchaQcHk (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Kull, C.A.; Ratsirarson, J.; Randriamboavonjy, G. Les Forêts de Tapia Des Hautes Terres Malgaches. Terre Malgache 2005, 24, 22–58. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, F.; Geneletti, D.; Newton, A.C. Towards a Common Set of Criteria and Indicators to Identify Forest Restoration Priorities: An Expert Panel-Based Approach. Ecol. Indic. 2011, 11, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, E.; Asner, G.P.; Keller, M. Forest Fragmentation and Edge Effects from Deforestation and Selective Logging in the Brazilian Amazon. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, K.A.; Macdonald, S.E.; Burton, P.J.; Chen, J.; Brosofske, K.D.; Saunders, S.C.; Euskirchen, E.S.; Roberts, D.; Jaiteh, M.S.; Esseen, P.A. Edge Influence on Forest Structure and Composition in Fragmented Landscapes. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 768–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noon, B.R.; Dale, V.H. Broad-Scale Ecological Science and Its Application. In Applying Landscape Ecology in Biological Conservation; Gutzwiller, K.J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tamene, L.; Mponela, P.; Sileshi, G.W.; Chen, J.; Tondoh, J.E. Spatial Variation in Tree Density and Estimated Aboveground Carbon Stocks in Southern Africa. Forests 2016, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akossou, A.Y.J.; Palm, R. Impact of Data Structure on the Estimators R-Square and AdjustedR-Square in Linear Regression. Int. J. Math. Comput. 2013, 20, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Caustom, D.R. An Introduction to Vegetation Analysis: Principles, Practice and Interpretation; Academic Division of Unwin Hyman Ltd.: London, UK, 1988; ISBN 9780045810253. [Google Scholar]

- Santilli, M.; Moutinho, P.; Schwartzman, S.; Nepstad, D.; Curran, L.; Nobre, C. Tropical Deforestation and the Kyoto Protocol. Clim. Chang. 2005, 71, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A.; Kaimowitz, D. Rethinking the Causes of Deforestation: Lessons from Economic Models. World Bank Res. Obs. 1999, 14, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houinato, M.; Sinsin, B.; Lejoly, J.; Houinato, M.; Sinsin, B.; Lejoly, J. Impact Des Feux de Brousse Sur La Dynamique Des Communautés Végétales Dans La Forêt de Bassila (Bénin). Acta Bot. Gall. 2001, 148, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biaou, S.S.H.; Natta, A.; Dicko, A.; Kouagou, M. Typologie Des Systèmes Agroforestiers et Leurs Impacts Sur La Satisfaction Des Besoins Des Populations Rurales Au Bénin. Bull. Rech. Agron. Bénin 2016, 12, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hountondji, Y.C.; Gaoue, O.G.; Sokpon, N.; Ozer, P. Analyse Écogéographique de La Fragmentation Du Couvert Végétal Au Nord Bénin: Paramètres Dendrométriques et Phytoécologiques Comme Indicateurs in Situ de La Dégradation Des Peuplements Ligneux. Geo. Eco. Trop. 2013, 37, 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- INStaD. Monographie de La Filière «Coton» Au Bénin. Document de Travail, N°DSEE2020DT02. Version Révisée de La Monographie de La Filière Du Coton Au Bénin. 2020. Available online: https://instad.bj/images/docs/insae-publications/autres/DT/MonographieFiliereCotonauBenin_20201025_Finale.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- DSA. Les Chiffres Définitifs de La Campagne Agricole 2021–2022; Direction de La Statistique Agricole, Ministère de l’Agriculture, de l’Elevage et de La Pêche: République Du Bénin, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Orékan, V.A. Implémentation Du Modèle Local CLUE-s Aux Transformations Spatiales Dans Le Centre Bénin Aux Moyens de Données Socio-Économiques et de Télédétection. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Bonn, Bonn, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ouedraogo, I.; Tigabu, M.; Savadogo, P.; Compaoré, H.; Odén, P.C.; Ouadba, J.M. Land Cover Change and Its Relation with Population Dynamics in Burkina-Faso, West Africa. Land Degrad. Dev. 2010, 21, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, B. Les Effets Du Surpâturage et Des Pratiques Agricoles Dans La Transformation Du Couvert Végétal de La Forêt Classée de Koutal. Rev. Can. Géographie Trop. 2021, 2, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- OSAN. Projet d’Aménagement Des Massifs Forestiers d’Agoua, Des Monts Kouffé et de Wari-Maro. Rapport d’Achèvement de Projet. 2008. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/projects-and-operations/benin_-_projet_damenagement_des_massifs_forestiers_dagoua_des_monts_kouffe_et_de_wari-maro_-_rapports_devaluation.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Arouna, O.; Etene, C.G.; Issiako, D. Dynamique de l’occupation Des Terres et État de La Flore et de La Végétation Dans Le Bassin Supérieur de l’Alibori Au Benin. J. Appl. Biosci. 2016, 108, 10543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foli, E.G. Reshaping the Terrain: Forest Landscape Restoration Efforts in Ghana. In Global Landscapes Forum Factsheet; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Anthropogenic Disturbances | Relative Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Logging | 100.00 |

| Agriculture | 43.67 |

| Grazing | 35.00 |

| Charcoal Production | 19.00 |

| Fires | 19.33 |

| Charcoal Production | Fires | Grazing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 3.05 NS | 15.41 ** | 0.48 NS |

| Charcoal production | - | 4.96 * | 2.42 NS |

| Fires | - | - | 3.72 NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sodalo, C.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Rakotondrasoa, O.L.; Muteya, H.K.; Musavalando, C.M.; Mbarushimana, D.; Cirezi, N.C.; Gbozo, E.; Citawa, C.B.; Akossou, A.Y.J.; et al. Anthropogenic Disturbance Factors in the Ouémé Supérieur Classified Forest in Northern Benin. Land 2025, 14, 2350. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122350

Sodalo C, Sambiéni KR, Rakotondrasoa OL, Muteya HK, Musavalando CM, Mbarushimana D, Cirezi NC, Gbozo E, Citawa CB, Akossou AYJ, et al. Anthropogenic Disturbance Factors in the Ouémé Supérieur Classified Forest in Northern Benin. Land. 2025; 14(12):2350. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122350

Chicago/Turabian StyleSodalo, Carlo, Kouagou Raoul Sambiéni, Olivia Lovanirina Rakotondrasoa, Héritier Khoji Muteya, Charles Mumbere Musavalando, Didier Mbarushimana, Nadège Cizungu Cirezi, Edouard Gbozo, Cléophace Bayumbasire Citawa, Arcadius Yves Justin Akossou, and et al. 2025. "Anthropogenic Disturbance Factors in the Ouémé Supérieur Classified Forest in Northern Benin" Land 14, no. 12: 2350. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122350

APA StyleSodalo, C., Sambiéni, K. R., Rakotondrasoa, O. L., Muteya, H. K., Musavalando, C. M., Mbarushimana, D., Cirezi, N. C., Gbozo, E., Citawa, C. B., Akossou, A. Y. J., & Bogaert, J. (2025). Anthropogenic Disturbance Factors in the Ouémé Supérieur Classified Forest in Northern Benin. Land, 14(12), 2350. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122350