Abstract

This review article engages with ongoing advocacy for proactive urban design that responds to user-driven transformations in public spaces. These changes often occur beyond the control of professional design intervention. Urban design and community development disciplines have made significant contributions to enhancing public spaces over the past few decades. This manuscript seeks to build on the strengths of both disciplines by integrating them into “proactive urbanism”. We conducted a scoping review and meta-analysis of relevant sources in Scopus, Scopus AI, and Google databases on urban design and community development, aiming to identify commonalities that offer proactive insights for the design of public places. The findings of the bibliometric study suggested areas of meaningful convergence between urban design, with its emphasis on spatial form, and community development, which foregrounds social dynamics and lived experiences. The nexus of urban design dimensions—socio-temporal and spatial—can provide a future framework for analysis. This approach supports the creation of public spaces that are both resilient and responsive. It aligns with designers’ aspirations and addresses the everyday needs of communities. By foregrounding both lived experience and anticipatory design practices, this manuscript argues for a more collaborative framework—one that bridges policy, design, and grassroots action to support a more responsive, community-centered urban evolution.

1. Introduction

The evolution of public spaces is challenging for urban planners and designers [1,2,3]. The reason is shifting urban design paradigms that advocate deep interconnectedness between designed public space forms and spontaneous changes driven by user experiences [4,5]. These paradigm shifts often require user-initiated interventions that occur independently of expert control or guidance in redevelopment plans [6,7]. Previous studies have addressed redevelopment by factoring in people’s needs, preferences, context, and co-design processes [8,9,10,11,12].

This article builds on the metaphor of a three-sided coin to explore the complex interrelationships among community development, urban design practices, and proactive urbanism. By drawing on this metaphor, we argue that the first side of the coin represents community development, a process through which local communities come together to identify shared concerns and co-create solutions. Widely recognized for its role in enhancing the social, economic, environmental, and cultural well-being of communities through urban design, community development is grounded in principles of participation, empowerment, equity, and sustainability [13,14]. The second side refers to the spatiotemporal dimension of urban design—how space is produced, experienced, and transformed over time [5,15]. This aspect captures how urban form and design directly shape and are shaped by the rhythms of everyday life in public spaces. While a traditional coin has two faces, we propose a third conceptual “side”—the edge—to symbolize the proactive urbanism that can handle the dynamic changes in public space. The third side—the edge—represents the proactive urbanism that can bridge the gap between design intention and lived experience [14,16,17,18]. It is at this edge that urban designers engage most directly with the evolving needs of communities, often negotiating between strategic visioning and responsive adaptation.

Proactive urbanism is an approach to urban planning and urban design that emphasizes anticipation, strategic foresight, and active intervention to shape the built environments in a sustainable, inclusive, and resilient manner [17,19,20]. Unlike reactive urbanism, which responds to problems as they arise, proactive urbanism seeks to prevent issues and optimize urban living conditions through forward-thinking strategies [21,22,23]. Proactive urbanism was discussed in the literature as an approach to strengthen urban resilience and adaptiveness by integrating climate mitigation efforts into planning processes [17,19,24,25]. Our study adopts the notion of proactive urbanism to describe planning practices that anticipate urban transformations rather than merely respond to them [26]. Drawing on theories of anticipatory governance [27,28], adaptive planning [29], and resilience thinking [23,30], proactive urbanism is positioned as an epistemic shift towards foresight and participatory modes of city-making [17,24]. It emphasizes the capacity of urban actors to co-produce knowledge and interventions before crises emerge, thereby reframing urban design as an ongoing process of negotiation and preparedness.

Current literature discusses proactive strategies that pre-emptively identify impactful contextual issues and prevent anticipated deviations from plans [16,17,31]. The literature on proactive strategies examines such concepts across various management disciplines, including environmental, risk, and social media management [14,18,32,33]. However, few studies specifically focus on proactive strategies or insights for managing spatiotemporal dimensions of public spaces that undergo changes and interventions initiated by local communities, beyond those planned initially by urban designers. In addition, a limited number of studies in urban design or related fields addressed the term ‘proactive’ [14,17,24,34]. Such studies focus mainly on the environmental and built environments, with limited attention to proactive action to address ongoing changes in the built environment driven by local communities [17,35].

Public spaces in many cities across the Globe are undergoing continuous transformation, driven by the evolving needs and everyday practices of local communities. These spaces are often reshaped through informal, user-led adaptations that reflect residents’ creativity, resourcefulness, and lived experiences. While such adaptations enhance the relevance and functionality of shared environments, they frequently occur in the absence of planning frameworks that support community engagement or design flexibility. This disconnection between top-down design and bottom-up use presents a challenge for sustainable and inclusive urban development [36]. There is a pressing need to develop approaches that integrate community development principles with urban design strategies, recognizing informal practices not as deviations but as essential contributions to the vitality and resilience of public space.

One way to limit or control the adverse effects of changes in public spaces is to use proactive, preventive solutions [11,13,14,23,27] that account for spatiotemporal modifications driven by community needs. To achieve this, we propose an approach called proactive urbanism, which anticipates potential changes in the functionality and appearance of public spaces before they occur. Rather than predicting exact outcomes, proactive urbanism focuses on preparing for a range of possibilities by embedding flexibility and adaptability into design and planning. This approach allows decision-makers and practitioners to plan in ways that accommodate evolutionary change, ensuring that public spaces remain functional and visually appealing even as they evolve [17,37,38].

This study aims to introduce a proactive urbanism for the development of public spaces by integrating community development with urban design. Specifically, it proposes adding a spatiotemporal analysis phase to the design and planning process to assess the functional and morphological impacts of both formal projects and informal user-led interventions. The objective is to align urban design practices more closely with community preferences and contextual realities. Thereby fostering public spaces that are not only context-sensitive but also resilient and adaptable to evolving social and spatial dynamics.

This study seeks to address the following key questions: How can the relationship between the dimensions of community development and urban design be conceptualized to frame a proactive urbanism that responds to the continuous socio-spatial dynamics of everyday life?

The current manuscript employs a mixed-methods approach that combines bibliometric analysis and content analysis of a selection of manuscripts in urban design and community development journals. The bibliometric analysis explored how principles of community development are conceptualized and represented in the urban design literature indexed in Scopus and Google. The study identifies overlapping themes between urban design and community development studies. At the same time, content analysis provides proactive guidance for urban design and community development theory and practice, which can guide future development of public spaces.

This paper contributes to the ongoing dialogue between community development and urban design by introducing an integrative perspective on public space planning and transformation. It presents principles for proactive urbanism that connect institutional design processes to community preferences, supporting approaches that respond to the evolving, often unpredictable nature of urban environments. In doing so, the study highlights how urban design can benefit from the participatory values and contextual sensitivity emphasized in community development. Additionally, the paper outlines a set of practical tools designed to strengthen the roles of key stakeholders—including urban planners, local authorities, and community members—in shaping more inclusive and adaptable public spaces. By promoting proactive urbanism, the proposed approach supports the development of public places that are resilient to change and responsive to both planned interventions and informal, community-led activities.

2. Research Justification

This study draws on the authors’ observations of ongoing spatiotemporal changes in cities worldwide. For instance, in Cairo, frequent transformations occur as users adapt public spaces to meet daily needs. These changes manifest on two primary scales: the urban form—which encompasses the urban fabric, land uses, activities, and movement systems—and everyday life scenarios, such as contextual design and pedestrian behaviors. Both scales are deeply connected to city development and influence interactions among people and their environment. Actions such as widening roads, constructing overpasses, improving sidewalks, enhancing aesthetics, and expanding access to parks and public transportation all contribute to the evolution of these urban landscapes.

Figure 1 depicts the spatiotemporal effects of activities taking place in public spaces that emerge without direct involvement from urban designers. These images likely depict the dynamic, organic changes that occur when everyday life activities shape public spaces [39]. These effects include shifts in pedestrian flow, altered uses of public spaces, and the creation of temporary or adaptable environments that meet community needs [40].

Figure 1.

Spaciotemporal effects of activities in Cairo, Egypt, in the absence of urban designers’ involvement. Source: The authors’ original photos after using Google Gemini (model ID: gemini-2.5-flash, release date: 17 June 2025) to transform them into sketches.

These observed changes justify this research by highlighting the dynamic interplay between government interventions and grassroots actions in shaping public spaces. While government initiatives represent systematic efforts to improve urban environments, community-driven activities—such as newsstands, kiosks, street food carts, outdoor restaurants, shop extensions, street vendors [41,42,43,44]—address immediate needs and add vibrancy to city life. Community-driven activities, which include informal activities, provide essential services, create employment opportunities, stimulate local economies [44], and foster social and cultural diversity, especially by welcoming newcomers to the city [45].

A primary motivation for this research was to understand how significant spatiotemporal changes in public space usage affect cities, particularly in hot arid zones where activities shift from day to night. While many public spaces are designed for daytime use, users often adapt these environments for evening and nighttime activities, sometimes in ways that conflict with original design intentions and create tension among different user groups [17,46]. In middle- and low-income economies, the prevalence of informal activities in public spaces highlights the needs that can challenge formal urban control [47,48]. Investigating these patterns is crucial for developing flexible urban spaces that accommodate a wide range of daily activities [49]. Urban designers should, in this regard, anticipate both diurnal and nocturnal uses to ensure public spaces serve all users effectively [23,34,50].

Public spaces in developing nations are experiencing continuous spatiotemporal transformations. Addressing these challenges requires an interdisciplinary, evidence-based approach that aligns policy with observable local needs and practices. In densely populated areas, growing demand and limited land add further pressure. Responsive design strategies can blend established urban design principles with insights from informal and localized use. Ongoing dialogue among urban designers, policymakers, and communities is essential. Collaborative, research-informed planning can create public spaces that are more inclusive, adaptable, and supportive of community well-being, thereby strengthening urban resilience and vitality [51].

Observations of urban design traditions in countries such as Italy, France, and Germany highlight the importance of contextualism. There, urban form arises from the interplay between built mass and open space [52,53]. Such models show how projects can reflect local meaning and culture when developed in a spatial and social context. Similarly, a design-in-context approach helps reconcile formal planning with the organic realities of daily urban life by recognizing local usage patterns and movement.

The ever-changing nature of public spaces reflects shifting societal preferences, often visible in informal encroachments by vendors or shopkeepers. While these unregulated additions may not align with formal planning principles, they reveal underlying socio-spatial needs and challenge rigid frameworks. This framework underscores the need to rethink urban design, moving beyond top-down planning to embrace contextual responsiveness and community participation.

In our manuscript, we discuss how people are recreating public spaces by adding activities without hiring an urban designer. For example, the architectural dynamics of street food-vending activities in Dar es Salaam city center, Tanzania [54], the forces of shaping urban morphology in Southern Africa [7], and the foodscape of the urban poor in Jakarta [41]. This phenomenon is widespread in many residential areas around the globe [20,22], but it has received scant attention from experts so far. It remains uncertain whether this widespread phenomenon has positive or negative consequences for the environment and people. Therefore, a more in-depth study of the issue is required to understand the phenomenon and assess its effects. Understanding the participants’ motivations is crucial for determining the most effective way to manage this phenomenon in practice. Although stereotyped and done stereotypically, it still contains hidden ideas worth knowing.

Given the continuous evolution of public spaces influenced by people’s preferences and ongoing development projects, it is essential to investigate how integrating urban design principles with community development can foster proactive urban design. This research is justified by the need to develop urban environments that anticipate and accommodate ongoing change while simultaneously integrating communities’ aspirations and enhancements introduced by developers. By examining strategies that unify these dimensions, cities can be systematically equipped to adapt to dynamic contexts, promote inclusive public life, and strengthen urban resilience.

3. Methods and Materials

This manuscript adopts a mixed-methods approach that combines bibliometric analysis via a scoping review with qualitative content analysis. The bibliometric analysis complements this by addressing a gap in the literature on the intersection of community development and urban design.

3.1. Data Mining

This study employed a scoping review [55] to identify and analyze principles that align with community development goals while accommodating ongoing social and temporal changes. Conducting a scoping review of the urban design literature paved the way for proactive urbanism, which bridges the gap between urban design and community development. The search was conducted using Scopus, Scopus AI (March 2025 update), and Google databases. Scopus was accessed through the first author’s institutional subscription, and the Google database was included for its free access to reports and other open-access sources. This study excluded Web of Science, despite its availability to the authors, because of its limited coverage of community development materials in the social sciences and humanities. The search was conducted in May 2025, focusing on social sciences, arts, and humanities, as they align with the authors’ areas of specialization. The bibliometric search involved three rounds of data mining, each with a specific purpose and its own set of inclusion and exclusion criteria to select relevant materials.

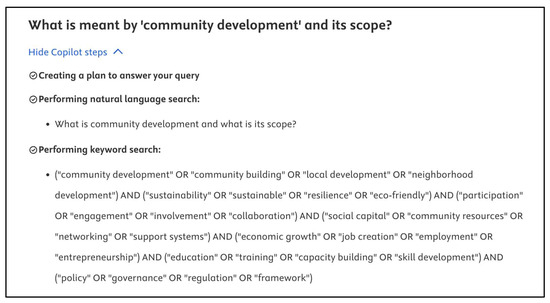

The first round of data mining aimed to clarify what is meant by ‘community development’ and its scope. We used targeted questions to search both the Scopus AI database (Figure 2) and the Google database. Table 1 illustrates the materials yielded in each round of data mining. Only sources that provided a clear definition of “community development” were included, while others were excluded. We further narrowed our search to credible sources: materials indexed in Scopus and reports from respected international organizations in Google. Scopus AI identified 10 relevant manuscripts, while Google search identified reports from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), the International Association for Community Development (NCDA), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the World Bank’s Community Driven Development initiative [56,57,58,59,60].

Figure 2.

The steps utilized in Scopus AI, available through the first author’s university subscription, October 2025.

Table 1.

The category of manuscripts yielded in our search. Source: The authors.

The data mining was guided by the question: What community development initiatives are informed by urban design? Inclusion criteria for targeted journal titles containing the terms “community” and “development”, and the query string was limited to these two keywords appearing in the article title, abstract, or keywords. This search yielded 1372 records published between 1966 and 2025.

In the second round, to bridge the gap between urban design and community development, an additional data-mining round was conducted on Scopus in late October 2025. The inclusion–exclusion criteria focused on sources that included “urban design” in their source titles and “community development” in article titles, abstracts, and keywords. The results revealed 19 manuscripts published across three journals: Journal of Urban Design, Urban Design International, and Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers—Urban Design and Planning. Additionally, six other manuscripts were found, published as books, book chapters, or in conference proceedings. In total, 25 manuscripts addressing community development within the context of urban design were identified, spanning the period from 1996 to 2025.

In the third round, a data-mining search was conducted in the Scopus database for articles containing “proactive” in the article titles. Only results from the arts and humanities subject area were considered, yielding 562 documents published between 1945 and the date of this study.

3.2. Data Analysis: Bibliometric Mapping and Content Analysis

The data analysis consisted of bibliometric mapping and content analysis. We used VOSviewer (version 1.6.20) to conduct a structured bibliometric analysis of the data from the three rounds of data mining. We used materials focused on generating co-occurrence maps (all keywords and full counting) for keywords related to ‘community development’, ‘urban design’, and ‘proactive urbanism’ to identify the main research themes. We set the minimum number of occurrences for a keyword to 3.

Table 2 illustrates the parameters in each round operated in VOSviewer. We refined the threshold values and explored cluster formations to examine the dataset’s thematic structure and interrelations. Each round contributed to a more nuanced understanding of the research landscape. VOSviewer was applied iteratively to visualize and refine keyword networks and thematic clusters. Each round involved adjusting parameters such as minimum occurrence thresholds and cluster resolution to ensure the robustness and clarity of the resulting maps. VOSviewer automatically selected the keywords with the highest total link strength and modularity (LinLog). All irrelevant words, such as ‘article’, ‘open access’, ‘man’, ‘woman’, or ‘human’, were excluded.

Table 2.

VOSviewer parameters. Source: The authors.

Then, the manuscript used content analysis of materials common to community development, urban design, and proactive urbanism. After applying this layer of filtration, 19 manuscripts were identified that contained all three standard terms (Appendix A, Table A1). The analysis was performed on the full texts of the materials, focusing on theory, practice, and principles. The content analysis focused on Keywords (GEOBASE Subject Index and 1980–present accessed June 2025), the core arguments of the manuscripts, their alignment with our argument, and the key principles of community development from an urban design perspective.

4. Results: Urban Design Gives Form; Community Development Gives Purpose

4.1. Community Development Principles and Urban Design Dimensions

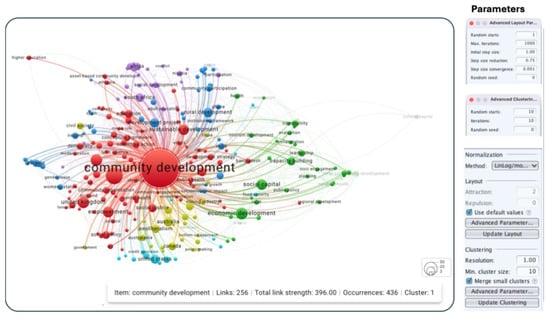

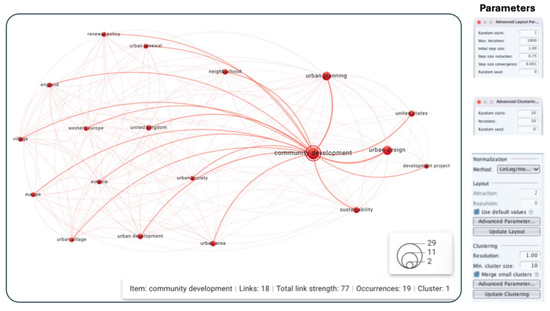

Our results from the bibliometric analysis showed a set of bibliometric network maps generated using VOSviewer. The data analysis illustrated the relational structures of keywords across different datasets. Each map visualizes how frequently specific terms co-occur with others in the academic literature, thus revealing the conceptual associations surrounding key research themes.

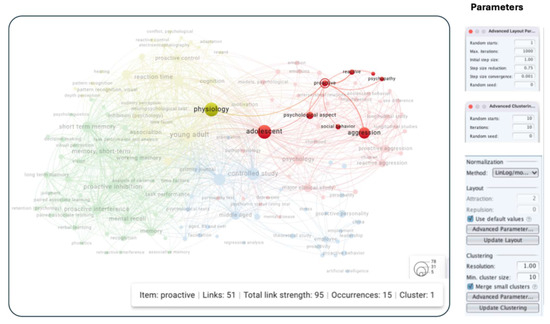

In the first map, “community development” appears as a dominant, highly connected term, with 256 links and a total link strength of 396, reflecting its central role in interdisciplinary studies linking economic development, social capital, governance, and education (Figure 3). The second map, which also centers on “community development,” shows a more focused network with 18 links and a total link strength of 77, situating the concept primarily within urban planning and design discourse. Community development was also linked to terms such as urban policy, sustainability, urban regeneration, and urban design, indicating its contextualized application in spatial and planning research (Figure 4). The third map shifts the focus to the keyword “proactive,” revealing 51 links and a total link strength of 95 (Figure 5). This network is dominated by themes in psychology and behavioral sciences, especially those related to adolescence, cognition, reaction time, and social behavior. Altogether, the bibliometric analysis through VOSviewer demonstrates how keyword co-occurrence mapping can trace the conceptual breadth and disciplinary intersections of core terms, highlighting how “community development” operates across social and spatial studies, while “proactive” is anchored within cognitive and behavioral research domains. Our results indicate that community development is well connected in the literature with terms such as ‘local participation’, ‘empowerment’, ‘participatory approaches’, ‘sustainable development’, ‘social policy’, and ‘education.’ Community development was also recognized in sources (journals) discussing topics relevant to urban design. Community development in urban design focuses on issues such as urban renewal, urban development policy, and sustainability.

Figure 3.

The word occurrence of ‘community development’ in the selected literature. Source: The authors utilized VOSviewer (version 1.6.20).

Figure 4.

Community development in the journals that focus on urban design. Source: The authors used VOSviewer (version 1.6.20).

Figure 5.

‘Proactive’ is the social sciences, art, and humanities. Source: The authors used VOSviewer (version 1.6.20).

The cases reported were from the United Kingdom, Western Europe, and Eurasia territories. This mapping highlights the need for further research to bridge the contributions of community development with urban design. The communality between community development and urban design can be recognized accordingly in terms of the social dimension and citizen involvement in urban development projects. Throughout our investigation of the term ‘proactive’ in the field of ‘art and humanities’, we found a growing number of manuscripts that handle this topic (562 manuscripts). However, a limited number of manuscripts on specific topics discuss ‘proactive’ approaches in community development or urban design (see the third map in our bibliometrics mapping). Our results from bibliometric analysis reiterate that community development is widely recognized as a transformative process that empowers individuals and groups to improve their collective well-being [61].

Our data investigation revealed that community development is a comprehensive approach that involves community members’ active participation to achieve collective goals [62,63,64]. It is guided by principles of empowerment, social justice, and sustainability and requires practical evaluation and collaboration across sectors to address the multifaceted challenges communities face today. This definition emphasizes empowerment through skill-building, enabling individuals to effect change in their own communities [65].

Community engagement is central to participatory planning and has proven effective in generating locally informed, trust-based solutions that should be produced by internal and external stakeholders [66,67]. It also fosters social capital, thereby enhancing urban resilience and adaptability [63]. When paired with flexible design strategies, urban planning becomes more responsive to community needs and less dependent on rigidly imposed structures [68].

Community development is widely recognized as an “essentially contested concept”, meaning that its definition is subject to continuous debate and reinterpretation [63]. Scholars identify several key dimensions of community development. The descriptive dimension addresses what communities are and how they function in practice, while the normative dimension reflects what communities ought to be, guided by values such as justice, equality, and participation. The prescriptive dimension, in turn, highlights ideals and models for how community development should be pursued [62,63,69,70]

Definitions of community development vary across contexts, ranging from a process of collective action aimed at improving social, economic, and cultural well-being to a field of study that is both transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary, evolving in response to change and uncertainty. The reviewed materials confirm that no single evaluation model is universally applicable [71,72]; instead, adaptive, participatory, and culturally sensitive approaches are required.

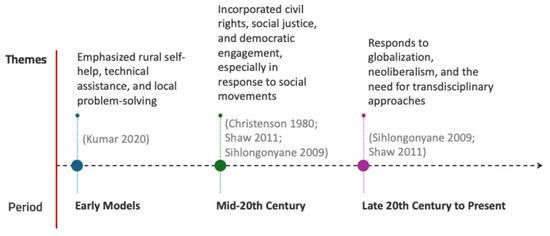

Community development is described not only as a process but also as a method, movement, and paradigm. Mediating structures—such as local organizations—play a vital role in fostering community identity and purpose [73]. In rural contexts, particularly, the community itself often holds definitional power, directly shaping the direction and priorities of development efforts [73,74]. The description of community development has undergone three phases of transition: early models, mid-20th century, late 20th century, and the present (Figure 6). The thematic focus of community development has shifted in response to broader political, economic, and social changes, reflecting its dynamic and adaptive nature.

Figure 6.

Historical evolution of community development themes. Source: The authors based on the literature [75,76,77,78].

Despite the growing attention to the concept, significant gaps and inconsistencies remain in its definitions. A lack of universal agreement leads to widely varying definitions across the literature, resulting in inconsistent application and evaluation of practices [63,79,80]. Furthermore, the tension between framing the concept as a process versus an outcome complicates the development of clear and coherent evaluation criteria [63,81]. The risk of the term becoming a buzzword further exacerbates this problem, as overuse and lack of clarity can dilute its meaning and hinder effective practice [70]. Additionally, many existing definitions fail to incorporate culturally specific values, limiting their relevance and applicability in diverse contexts [71].

4.2. The Concept of Proactive Urbanism to Anticipate Future-Ready Cities

The proactive approach to urbanism is a familiar concept; it can be found in various forms of literature. For example, Design for reliability: Human and organizational factors by Robert G. Bea [82], and Children and City Design: A Proactive Process and the ‘Renewal’ of childhood by Mark Francis and Ray Lorenzo [83]. Besides other literature, such as Turning a Town Around: A Proactive Approach to Urban Design by Anthony Hall [34] and “A proactive approach for predicting recurrent defective designs” by Andi and Minato [16], implicitly addressed proactive action. Additionally, many international organizations have emphasized that urban resilience encompasses a proactive approach that enhances the ability to resist, absorb, recover from, and reorganize, particularly during and after disasters [60,84,85]. For example, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) [60] adopted a framework to build urban resilience to natural disasters, climate change, and other shocks, comprising interlinked components such as risk assessment, prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery. Previous studies report that urban resilience requires significant investment in infrastructure, systems, and services, but also emphasize the importance of human capital, including skills, values, attitudes, and behaviors [14,17,32,33].

The literature referenced above describes a proactive approach as anticipating potential issues, changes, or opportunities and taking steps in advance to prepare for them. In contrast, a reactive approach involves addressing problems or changes as they arise, responding only after an event occurs. The concept of proactive urbanism presented in this viewpoint is a helpful approach to incorporating public spaces into the built environment, enabling evolutionary functional and morphological changes.

Proactive urbanism empowers planners and designers to create adaptable solutions that can be applied at various scales, including urban plans, urban forms, and everyday experiences. By anticipating these changes, decision-makers can take proactive measures to prevent them from occurring and stay ahead of upcoming developments. Also, proactive urbanism offers preventive solutions to counteract the adverse effects of improvement projects or individual actions that may contradict the original public space design. By managing these changes, proactive urbanism can optimize the built environment and benefit its residents.

5. Discussion: Proactive Urbanism from Theory to Practice

Improving public spaces in cities requires collaboration and proactive solutions. Urban designers have valuable expertise in understanding the complex relationships between stakeholders and urban systems, making them significant contributors to the design process. This section presents three groups of principles for Proactiv Urbanism that can bridge the gap between community development actions and urban design dimensions. Proactive urbanism can guide decision-makers, urban planners, and designers in local governments to anticipate and accommodate changes in public spaces based on people’s preferences, design in context, and the presence of an urban designer. Additionally, this article provides examples of solutions that can be implemented in cities to address spatiotemporal changes driven by everyday life practices shaped by people’s preferences.

5.1. Design in or out of the Context

The term “design in or out of the context” refers to the relationship between a design project and its surrounding environment—be it physical, social, cultural, or historical [86]. Design in context means that the design responds sensitively to its setting, reflecting the local identity, needs, and characteristics of the place or community [87]. It integrates harmoniously with existing conditions, such as climate, materials, urban fabric, and cultural values. In contrast, design out of context occurs when a project is developed without considering these contextual factors, resulting in a design that feels disconnected, imposed, or foreign to its surroundings [88]. This distinction highlights the importance of contextual awareness in achieving meaningful, sustainable, and place-responsive design outcomes [34,89,90].

Design solutions for public spaces are presented as catalysts for social change. Proactive, preventive solutions relevant to the urban context focus on examining and evaluating the fundamental transformations of everyday life in public spaces. They concentrate on unexpected life activities. It is a vital link between community development and activities to preserve the urban context. This link can be developed by creating public spaces within the urban context, while also accommodating external additions. This paradox requires design ideas that accept surprise, shock, and contradiction. Therefore, it is necessary to design the residential area to accommodate changing movement patterns over time, in response to improvement projects and individual actions. With these possibilities in design, in context, and outside the context, these ideas include:

Urban control over individual- and community-driven actions in public spaces targets adherence to design guidelines, whether in or out of context [91] to avoid any encroachment or irregularity that does not align with the overall urban form and expected daily lifestyle [92]. Urban control can also create a more unified and consistent urban environment. In this way, urban designers can help preserve the city’s unique architectural legacy of public spaces. By avoiding haphazard individual actions, public spaces can retain their traditional patterns and promote space-friendly landscapes, making it easier for people to move around and interact with their surroundings [89].

The idea of “design in or out of context” highlights the tension between the transferability of urban design models and their sensitivity to local specificities [86,93]. However, some design principles from other contexts can inspire innovation when locally reinterpreted, as seen in the adaptation of European public-space design models in some American cities [94]. Other examples highlight the risks of failure when reinterpretations neglect local cultural, climatic, or socio-economic realities. In such cases, a lack of future-oriented contextual responsiveness has led to spatial exclusion or rapid physical deterioration [24,86,95]. Consequently, the success of proactive urbanism depends less on the originality of design forms than on their capacity to engage meaningfully with local urban conditions.

5.2. Designing in Relation to People’s Preferences

Creating public spaces that cater to users’ needs and preferences requires proactive, preventive design solutions [96]. Design specialists should consider unexpected user preferences when undertaking improvement projects or individual actions. By focusing on pertinent inputs, such as urban design dimensions, specialists can ensure that people’s knowledge of a place is incorporated into the design. This research provides valuable insight into how to proactively and preventively design or improve public spaces. The following are some suggested examples. Proactive and preventive solutions involve making public spaces flexible in terms of dimensions, shapes, characteristics, and structural relationships.

Each space can accommodate various unexpected activities depending on the users and the time of day. Due to this diversity, public spaces are plentiful enough to meet people’s diverse preferences and reduce the need to modify them after they have been designed. These solutions also foster a sense of ownership and responsibility among users, encouraging them to change, improve, or maintain the public space. Additionally, it strengthens the social bonds between people who use the space and helps create a sense of community. Residents of San Francisco, for instance, can adopt and maintain street furniture through a program that creates a sense of responsibility among them [97].

Our primary objective is to significantly enhance the aesthetic appeal of public spaces, benefiting all individuals. Urban designers can achieve this by strategically incorporating elements that heighten spatial awareness and visual interest, such as easy accessibility, high visibility, and a clear comprehension of newly added activities [98]. Additionally, we ensure that the design is compatible with surrounding activities. By doing so, we can effectively exhibit local ingenuity and promote social interaction. Our approach ensures that public spaces are engaging and cater to the diverse preferences of all individuals.

These concepts aim to restrict individual actions through a straightforward plan that offers choices to accommodate various preferences. One effective way to accomplish this is to simplify the identification of the most suitable connections between activities and functions and to provide users with the flexibility to modify them. This approach ensures that urban space remains in a perpetual state of development.

The proposed design guidelines should be discussed with greater attention to their potential social, economic, and accessibility implications. While spatial coherence and visual order are essential for urban legibility, overly design control may unintentionally limit inclusivity or stifle adaptive community practices. Empirical studies have shown that highly codified urban environments can exacerbate socio-spatial inequalities or marginalize informal users when regulations fail to accommodate diverse needs and capabilities. Therefore, proactive urbanism should balance design regulation with social flexibility, ensuring that interventions remain responsive to context-specific dynamics and accessible to all urban actors.

5.3. Design with or Without Urban Designers’ Involvement

Urban designers can create public spaces that cater to people’s preferences and design in context, while seamlessly blending into the environment [99,100]. This understanding can only be achieved by thoroughly identifying the needs of the target users. It requires developing practical, visually appealing public spaces for both direct and indirect users. Urban designers understand the interconnectivity of a city’s infrastructure and how its various components interact. They can appreciate the intricate relationships among stakeholders—such as businesses, residents, and the government—and develop beneficial solutions. Their expertise can be used to create sustainable, efficient, and enjoyable cities for residents.

Urban designers’ proactive solutions can help cities become more resilient and better prepared for future environmental and population changes. They can also help cities become more equitable by providing access to quality education, healthcare, and other essential services. Poorly designed cities can create and perpetuate inequality, as they often need access to essential services [101,102]. They can be challenging to navigate for those with physical or mental disabilities. With urban designers, cities would be much more organized and efficient, rather than having haphazard layouts and inadequate infrastructure. Urban designers must consider the needs of all people, including those with disabilities.

Urban designers anticipate public spaces in residential areas by providing proactive, preventive solutions. Thus, any future additions will be accommodated through new ideas—for example, public spaces can be designed at varying rates in response to innovative urban designers’ ideas and user preferences. Urban designers can significantly enhance the standards of residential public spaces. It also expands the minimum space required for standard layouts and design modifiers. Additional activities can be accommodated by adding public spaces to the piers and center islands. These extra spaces are achieved without affecting the structural gradient or street specifications, including width, number of lanes, and street speed. Another idea is that the urban design plan should include proactive solutions to accommodate anticipated activities.

The literature also highlights the role of proactive urbanism, emphasizing the need for cities to be resilient in the face of challenges such as climate change and health crises. For instance, cities like Berlin, Milan, Oakland, and Bogotá demonstrated resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic by quickly adapting their mobility systems, facilitated by pre-existing sustainable urban mobility policies. This result aligns with SDG 11’s focus on resilience [16,17,18,20,33].

The following principles of proactive urbanism are not intended as universally applicable prescriptions but as context-sensitive propositions whose relevance depends on local social, economic, and cultural conditions. While these principles proposed here aim to strengthen proactive urban practices, their application may yield varied results depending on governance capacity, community inclusion, and socio-economic context. Further research is needed to examine the unintended or uneven impacts of proactivity, especially in marginalized settings.

Building on our results, we concluded five key principles that could form the foundation of a proactive approach in urban planning, specifically within the framework of proactive urbanism:

- Anticipation of future needs and challenges: Proactive Urbanism emphasizes forecasting future urban needs and challenges before they arise. This principle focuses on analyzing long-term trends, including population growth, technological advancements, climate change, and evolving societal behaviors. Urban planners and designers should predict these trends and embed adaptive solutions into public spaces from the outset. Designing flexible, multi-functional spaces that can easily adapt to changing demands, such as future mobility solutions (e.g., electric vehicle charging stations or autonomous vehicle infrastructure) or increased demand for green spaces.

- Community engagement and participation: The proactive approach prioritizes early and continuous engagement with the community. Understanding local needs, cultural values, and preferences enables designs that reflect residents’ lived experiences and anticipate their evolving needs. Including residents in the planning stages to gather insights on how they currently use public spaces and what future amenities they might need, ensuring the design evolves to meet community expectations.

- Flexibility and adaptability in design: Proactive designs should be adaptable, enabling modifications or updates without requiring complete overhauls. Spaces should be designed to accommodate multiple uses and changing urban functions over time. Adaptable solutions enable the urban environment to adjust to both predictable and unpredictable circumstances. Creating modular infrastructure in public spaces that can be easily reconfigured based on seasonal events, changing demographics, or disruptions like pandemics.

- Data-driven decision-making: The proactive approach relies heavily on data collection and analysis to inform design choices. By using urban data—including traffic patterns, environmental factors, and social behaviors—planners can make informed decisions to anticipate future problems. Leveraging data from smart city sensors to track usage of public spaces and predict wear and tear, enabling preemptive maintenance or redesign of areas prone to high traffic.

- Preventative Design Solutions: Urban designs should incorporate measures to mitigate potential negative impacts before they occur. These solutions could address challenges such as environmental degradation, social segregation, or even unplanned informal activities in public spaces. Incorporating green infrastructure like permeable pavements and rain gardens to prevent urban flooding or creating designated areas for informal vending to avoid the unregulated use of public space.

These principles of proactive urbanism encourage urban designers and decision-makers to move beyond reactive planning and embrace strategies that anticipate future challenges, ensuring that urban spaces remain functional, resilient, and responsive to community needs.

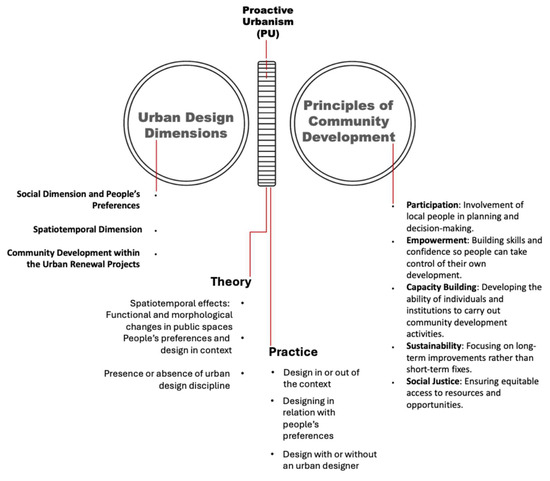

Figure 7 introduces a discussion on two key aspects: the conceptual and philosophical understanding of proactive urbanism and its application in real-world scenarios. The theoretical dimension explores the ideas, frameworks, and principles that underpin proactive urbanism as an academic discipline. At the same time, the practical side provides examples and case studies that illustrate the implementation of these concepts in urban development and design projects. These sections aim to bridge the gap between conceptual understanding and practical application.

Figure 7.

The nexus of urban design dimensions and principles of community development through proactive urbanism to meet the continuous changes based on people’s preferences. Source: The authors.

In line with previous studies, our suggested model can be similar to the comprehensive planning of Big Picture in Huntsville, Alabama. The city of Huntsville, through its 2018 comprehensive plan, regularly engages the local community and seeks to implement foresight planning for emerging issues [103]. Our suggested model can effectively predict future scenarios using the wildcard. Our main finding aligns with the view that early, subtle signs of change—if overlooked—can eventually develop into substantial disruptions. This connection reflects the notion of wild cards, a concept first proposed in 1992 by the Copenhagen Institute for Futures Studies, BIPE Conseil, and the Institute for the Future, and later further developed by John L. Petersen in Out of the Blue (1997) [50]. Wild cards describe events that are unlikely to occur yet capable of producing significant, unexpected shifts in ongoing trends or established systems. While such events are rare, they often represent decisive moments that redirect societal or organizational pathways. Typically, they are preceded by weak signals that serve as fragmented or early indicators of emerging change. Understanding this relationship highlights the importance of a proactive stance—one that actively monitors weak signals, anticipates potential disruptions, and enhances resilience and preparedness [104].

6. Conclusions

In this communication article, we aimed to examine the controversial question of whether urban designers should be involved in the further development of public spaces. Our research suggests that the redevelopment process for existing residential areas would greatly benefit from incorporating an additional phase focused on proactive, preventive solutions during redevelopment and post-occupancy evaluation. While urban designers play a critical role in shaping the built environment, our viewpoint emphasizes the importance of complementing their work with strategies that anticipate potential challenges and adapt to changes over time, such as functional and morphological transformations.

We argue in this manuscript that urban designers are indeed necessary in all phases of project design, implementation, post-occupancy evaluation, and redevelopment. However, their work should be supplemented with a proactive approach that accounts for the evolving nature of public spaces. A collaborative approach that balances professional expertise with community involvement is essential for the sustainable development of urban areas.

By focusing on urban plans, urban forms, and the everyday experiences of city dwellers, we have highlighted the spatiotemporal effects that emerge due to improvement projects or informal actions in built environments. This approach, which we refer to as Proactive Urbanism, encourages decision-makers to integrate forward-thinking strategies that address issues before they arise rather than react to problems once they manifest. However, we recognize that not all spontaneous matters can be predicted in advance; instead, proactive solutions aim to mitigate their impact.

Our key findings are that urban planning should evolve to incorporate proactive principles—such as understanding people’s preferences, designing within the local context, and involving urban designers in every phase of the process. Proactive urbanism does not diminish the value of urban designers; rather, it complements their role by introducing adaptable solutions that respond to changing environments. By doing so, planners and designers can create spaces that are not only responsive to current needs but also resilient in the face of future uncertainties.

The implications of this study extend to both policy and practice. For policymakers, proactive urbanism provides insights for developing adaptive regulations and design guidelines that prioritize long-term flexibility and community engagement. For practitioners, it offers a pathway to bridge the gap between design intentions and lived experiences by integrating preventive strategies throughout the project lifecycle. In academia, this approach invites further exploration of how proactive principles can be operationalized in diverse urban contexts, particularly in rapidly transforming regions. Adopting Proactive Urbanism encourages a shift in mindset—from reacting to urban challenges to anticipating and shaping them through informed, inclusive, and forward-looking design practices.

This study does not claim to present a universally validated model of proactive urbanism, but rather an exploratory framework that offers a foundation for further empirical testing and contextual adaptation rather than definitive prescriptions. The research limitation of this study lies in its reliance on literature review and theoretical analysis rather than assessing the applicability of proactive urbanism in real-world projects. Although the analysis of previous studies proposes a digital tool for tracking continuous changes in everyday life that may require rapid, proactive responses, its implementation has not been empirically tested within this research. Moreover, the study does not identify the specific actors responsible for operationalizing the principles of proactive urbanism. This study was also limited to English sources, which means it is based solely on non-English sources.

Additionally, several risks and limitations accompany the advancement of proactive urbanism. These include an over-reliance on expert-led or institutional perspectives that may underrepresent minority or marginalized voices, as well as the possibility of technological bias in data-driven design processes. Without inclusive mechanisms for community engagement and sensitivity to contextual inequities, proactivity could unintentionally reinforce rather than mitigate existing urban disparities.

The above limitations highlight several valuable directions for future research. Subsequent studies should aim to apply and evaluate the proposed framework in real-world settings—for example, through longitudinal case studies, participatory planning experiments, or comparative analyses of cities adopting anticipatory and adaptive design strategies. Further investigations could examine the roles of different actors and advance foresight-based planning approaches capable of predicting and responding to dynamic changes in everyday urban life. Future research may also develop an evaluation index system for proactive urbanism and explore its applicability across diverse cultural contexts. Additionally, drawing on non-English literature could enrich and further substantiate the conceptual links between proactive urbanism, urban design, and community development. Recognizing these limitations, this study calls for interdisciplinary and participatory approaches that empirically test and refine proactive urbanism across diverse urban environments. Future research can also develop an assessment framework or evaluation tool to measure the proactive qualities of public spaces and investigate the framework’s adaptability and implementation strategies across diverse contextual settings.

While this paper introduces proactive and preventative strategies, we acknowledge that this approach is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Instead, it offers a flexible framework that requires careful consideration of each unique built environment. Decisions about the design and improvement of public spaces should be grounded in both expert knowledge and local communities lived experiences. In conclusion, this article presents proactive urbanism as an innovative approach to urban planning that addresses the complex relationships between people, spaces, and time. By applying proactive strategies, decision-makers can better manage the unpredictable nature of urban environments while still relying on the specialized knowledge of urban designers to ensure the success of public space projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E. and H.A.; methodology, A.E.; formal analysis, A.E.; investigation, H.A.; resources, A.E.; data curation, A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E. and H.A.; writing—review and editing, A.E., H.A. and A.O.; visualization, A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used ChatGPT GPT-5 for proofreading and language editing. The Google AI (gemini-2.5-flash, released on 17 June 2025) was also utilized to resketch Figure 1. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The investigated materials of the content analysis.

Table A1.

The investigated materials of the content analysis.

| # | Authors | Date of Publication | Article Title | Source Title (Journal) | Keywords GEOBASE Subject Index | A Comprehensive Overview (Core Argument for Community Development) | Key Principles of Community Development from Urban Design Perspectives |

| 1 | Lung-Amam, W., Gade, A. | 2019 | Suburbia reimagined: Asian immigration and the form and function of faith-based institutions in Silicon Valley | Journal of Urban Design | Asian immigrant; community development; immigrant population; immigration; institutional development; migrants experience; social network; urban area | This study reviews 29 award-winning community projects to assess how well their sustainability claims align with actual environmental and socio-economic outcomes. It finds that most prioritize marketable design over holistic sustainability, revealing gaps in current urban development practices. |

|

| 2 | To, Kien; Chong, Keng Hua | 2017 | The traditional shopping street in Tokyo as a culturally sustainable and ageing-friendly community | Journal of Urban Design | aging population; community development; cultural economy; elderly population; shopping activity; sustainability; urban design; urban development | The central argument is that genuine, long-term community development and sustainability are deeply rooted in the community’s cultural fabric and in the active involvement of its members, particularly the elderly. It moves beyond purely economic or infrastructural development to emphasize social and cultural dimensions as foundational. The “shotengai” (traditional shopping streets) serve as a model of how communities can self-sustain and thrive by leveraging these intrinsic assets, even in rapidly modernizing urban environments. |

|

| 3 | Medved, Primož | 2017 | The essence of neighbourhood community centres (NCCs) in European sustainable neighbourhoods | Urban Design International | adaptive management; community development; implementation process; neighborhood; sustainability; urban design; urban system | The argument is that well-developed Neighborhood Community Centres (NCCs) are crucial, though often overlooked, catalysts for fostering “social urban sustainability” within local communities. They are not just buildings; they are vital pieces of social infrastructure that can significantly enhance a neighborhood’s social fabric, identity, and overall well-being. The quality of the NCC directly impacts its ability to contribute positively to these aspects of community life. |

|

| 4 | Rosenberg, Elissa | 2015 | Water Infrastructure and Community Building: The Case of Marvin Gaye Park | Journal of Urban Design | community development; infrastructural development; public space; social impact; urban design; urban planning | The core argument is that the principles inherent in the “infrastructure as landscape” model (decentralization, site-specificity, multifunctionality) can, if fully realized and intentionally applied, be powerful tools for community development. The current failure is not in the model’s potential but in its execution, which often neglects to leverage these principles for social gain actively. The paper suggests that these principles can foster stronger communities and deeper connections to place. |

|

| 5 | Guise, R. | 2015 | Community and streetscapes: The art of urban design revisited | Urban Design and Planning | community development; garden city; town planning; urban design; urban housing; urban policy | The core argument is that an “artistic approach” to urban design is not just about aesthetics for its own sake, but is fundamentally linked to creating better, more functional, and more meaningful communities. By focusing on beauty, delight, distinctiveness, and texture, this approach inherently fosters environments that support “well-being,” encourage positive social interaction (through good placemaking), and solve practical urban problems in ways that enhance residents’ quality of life. It suggests that community development is an intrinsic outcome of thoughtful, artistic urban design. |

|

| 6 | March, R.S. | 2014 | Designing Manhattan, New York, USA, in the face of climate change | Urban Design and Planning | climate change; education; infrastructure planning; planning process; training; urban design; urban planning | The community development was mentioned as an end outcome of enhancing | |

| 7 | Ruggeri, D. | 2014 | The ‘My Mission Viejo’ Project. Investigating the Potential of Photovoice Methods in Place Identity and Attachment Research | Journal of Urban Design | community development; development project; neighborhood; sustainability; urban design; urban planning | The core argument of this paper is that a strong, positive place identity, deeply felt by residents and fostered through thoughtful planning and design, is fundamental to building resilient, engaged, and sustainable communities. Community development is achieved by understanding, valuing, and actively shaping the emotional and perceptual bond between people and their physical environment. The process of eliciting and analyzing residents’ own perceptions of their place is a key tool in this endeavor. |

|

| 8 | Arefi, M. | 2013 | The structure of visual difference: A comparative case study of Mariemont and Lebanon, Ohio | Urban Design International | community development; comparative study; image; questionnaire survey; urban design; urban planning; urban society | This article delves into “the structure of visual difference” within a place and explores its planning implications. The central idea is that identifying the visual “differences”—the distinct or unique physical characteristics of an area—can empower people to express their opinions about its social meaning and image. This, in turn, helps them articulate what aspects of their community they would like to see changed, protected, or preserved. |

|

| 9 | Feldhoff, T. | 2013 | Shrinking communities in Japan: Community ownership of assets as a development potential for rural Japan? | Urban Design International | community development; demography; government; ownership; rural development; rural economy; rural policy | In the context of Japan’s rural depopulation and the emergence of genkai shūraku (marginal settlements), the article emphasizes a shift toward asset-based community development (ABCD) as a guiding principle for local responses. |

|

| 10 | Ogbu, Liz | 2012 | Reframing Practice: Identifying a Framework for Social Impact Design | Journal of Urban Design | community development; landscape planning; project design; social impact; strategic approach; urban design; urban planning | This manuscript proposes a framework for social impact design by analyzing three contemporary projects. It identifies four strategic dimensions—process, milieu, boundaries, and practice—that guide designers working in community-driven urban transformations and socially engaged design practices. |

|

| 11 | Mapes, Jennifer; Wolch, Jennifer | 2011 | ‘Living green’: The promise and pitfalls of new sustainable communities | Journal of Urban Design | community development; complexity; development project; sustainability; sustainable development; urban design | This work aligns with community development by revealing how surface-level or market-driven approaches often overshadow genuine efforts to foster inclusive, sustainable, and resilient communities. It implicitly supports community development principles such as equity, long-term planning, and social inclusion, which are often underrepresented in design awards or promotional materials. |

|

| 12 | Pereira Costa, S.A.; MacIel, M.C.; Campos, L.O. | 2010 | The public architecture programme and the nine de Março squatter settlement in Barbacena, Brazil | Urban Design International | community development; construction; development project; human settlement; quality of life; sustainable development; urban area; urban design; urban housing; urban planning | It highlights the need to:

|

|

| 13 | Gutberlet, Jutta; Hunter, Angela | 2008 | Social and environmental exclusion at the edge of São Paulo, Brazil | Urban Design International | edge city; housing conditions; living standard; poverty; social exclusion; urban development; urban population | The study emphasizes that sustainable community development must go beyond technical fixes to engage deeply with social justice and democratic governance. |

|

| 14 | Tait, Malcolm | 2003 | Urban villages as self-sufficient, integrated communities: A case study in London’s Docklands | Urban Design International | community development; renewal policy; strategic approach; urban planning; urban renewal; village; neighbourhood; urban area; urban development; village | The study examines whether the ideals of the urban villages movement—such as local self-sufficiency, integration, and vibrancy—are realized in practice. Drawing on fieldwork in West Silvertown, the study compares the community’s actual dynamics with the movement’s promises. It reveals a gap between the intended principles and the real-life social patterns, questioning the assumption that physical design alone can cultivate vibrant, integrated local communities. |

|

| 15 | Goodey, Brian | 2003 | Interpretive planning in a historic urban context: The case of Porto Seguro, Brazil | Urban Design International | community development; renewal policy; urban planning; urban renewal; heritage conservation; historic building; urban history; urban planning | This paper supports your broader argument that design practices should emerge from and reflect community narratives, especially in culturally sensitive and historically rich environments. |

|

| 16 | Thompson-Fawcett, Michelle | 2003 | ‘Urbanist’ lived experience: Resident observations on life in Poundbury | Urban Design International | community development; planning practice; urban design; urban society; village; urban area; urban design; urban development; urban population; village | This paper examines residents’ lived experiences in Poundbury and assesses how well the development meets urbanist goals. Findings reveal a gap between planned ideals and everyday reality, highlighting the need for inclusive, reflective, and resident-centred urban design practices. |

|

| 17 | Brindley, Tim | 2003 | The social dimension of the urban village: A comparison of models for sustainable urban development | Urban Design International | community development; renewal policy; sustainability; urban development; urban renewal; urban society; village; neighborhood; urban development; urban planning; village | This paper compares three urban sustainability models, focusing on their social objectives and built-form proposals. It reveals a mismatch between these visions and current social trends, casting doubt on the long-term viability of urban-village ideals in contemporary society. |

|

| 18 | Hillier, Bill; Greene, Margarita; Desyllas, Jake | 2000 | Self-generated neighbourhoods: The role of urban form in the consolidation of informal settlements | Urban Design International | informal settlement; neighborhood; urban development; urbanization | Community development, in this context, is closely linked to spatial opportunity rather than to formal planning or architectural input alone. The findings highlight how self-generated neighborhoods, when spatially well-integrated, can evolve into more cohesive, economically active, and socially stable communities, even without formal design interventions. |

|

| 19 | Varady D.P. | 1996 | Neighbourhood regeneration of Glasgow’s southside: implications for American cities | Journal of Urban Design | community development corporation; neighborhood regeneration; planning implication; urban renewal | The study argues that context-sensitive regeneration, rooted in architectural heritage, local control (e.g., housing associations), and socio-economic diversification, plays a critical role in revitalizing disadvantaged urban areas. It emphasizes that successful community development combines physical restoration with social and economic empowerment. |

|

References

- Huskinson, M.; Bernabeu-Bautista, Á.; Campagna, M.; Serrano-Estrada, L. Co-Designing Accessible Urban Public Spaces Through Geodesign: A Case Study of Alicante, Spain. Land 2025, 14, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Xu, L.; Feng, H.; Zhu, R. Identifying and Prioritising Public Space Demands in Historic Districts: Perspectives from Tourists and Local Residents in Yangzhou. Land 2025, 14, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; ISBN 9781315158457. [Google Scholar]

- Elshater, A.; Abusaada, H.; Tarek, M.; Afifi, S. Designing the Socio-Spatial Context Urban Infill, Liveability, and Conviviality. Built Environ. 2022, 48, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, K.; Hess, P.; Brody, J.; James, A. North American Street Design for the Coronavirus Pandemic: A Typology of Emerging Interventions. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2022, 17, 644–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. From Chaos to Order: Articulating the Urban Policies for Cities of Hardship. In Industrial and Urban Growth Policies at the Sub-National, National, and Global Levels; Benna, U.G., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 41–64. ISBN 9781522576259. [Google Scholar]

- Chirisa, I.; Matamanda, A. Forces Shaping Urban Morphology in Southern Africa Today: Unequal Interplay among People, Practice and Policy. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2019, 12, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, A. The Predicament of Post-Displacement Amidst Historical Sites: A Design-Based Correlation Between People and Place. Herit. Soc. 2021, 12, 85–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, A.; Mitchell, G.; Clarke, M. Not Just Any Old Place: People, Places and Sustainability. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. —Eng. Sustain. 2011, 164, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, G.; Bleibleh, S. The Nexus of Place Attachment, Spatial Behaviour and Subjective Well-Being. A Pilot Case of Indian Expatriates in Dubai. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra, P. The Ethics of Co-Design. J. Urban Des. 2024, 29, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A.; Rashed, R. Exploring the Singularity of Smart Cities in the New Administrative Capital City, Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.F. Community, Social Identity and the Structuration of Power in the Contemporary European City Part Two: Power and Identity in the Urban Community: A Comparative Analysis. City 2001, 5, 281–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, C. Rethinking the Role of the Community in Proactive Policing. In The Future of Evidence-Based Policing; Weisburd, D., Jonathan-Zamir, T., Perry, G., Hasisi, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, D.; Alizadeh, T.; Dowling, R. Smart City Place-Based Outcomes in India: Bubble Urbanism and Socio-Spatial Fragmentation. J. Urban Des. 2022, 27, 483–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andi; Minato, T. A Proactive Approach for Predicting Recurrent Defective Designs. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 3186–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, A.; Abusaada, H. Proactive Insights into Place Management: Spatiotemporal Effects of Street Food Activities in Public Spaces. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2024, 17, 442–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J. Proactive versus Reactive Environmental Management and Profitability of Indian Firms: The Moderating Effects of Environmental Cost-Efficiency and Environmental Liability. Environ. Chall. 2021, 5, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.; Sagar, R.; Pandey, A.; Yadav, D.; Ansari, M.S.; Rawat, R. Building Resilient Urban Futures: Adapting Cities to Climate Change Challenges. In Cities of Tomorrow: Urban Resilience and Climate Change Preparedness; Ghosh, S., Majumdar, S., Cheshmehzangi, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fazli, H.; Farooq, S.; Yang, C.; Wæhrens, B.V. Proactive and Reactive Approaches towards Sustainable Practices in Manufacturing Companies: Emerging Economies Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaee, A.; Rashed, M.; Islam, M.F.; Vasa, L. Innovative Configurations for Organizational Resilience: Bridging the Proactive and Reactive Capability in Volatile Environments. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Zhao, H.; Kulkarni, A.; Chattrath, S.; Zhang, A.X. Building Proactive and Instant-Reactive Safety Designs to Address Harassment in Social Virtual Reality. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 9, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, R. Introduction to Anticipation Studies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 1, ISBN 978-3-319-63021-2. [Google Scholar]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A.; Ouf, A.M. Proactive Urbanism—with or without an Urban Designer. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2025, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, L. Adaptable Cities and Temporary Urbanisms; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H.; Kim, S.; Jung, M. Data-Driven Urban Planning for Proactive Crowd Management: Lessons from the 2022 Seoul Halloween Crowd Crush. Cities 2026, 168, 106418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mboringong, F.A.; Riggs, R.A.; Langston, J.D.; Boedhihartono, A.K.; Endamana, D.; Ge, Y.; Innes, J.L.; Lu, J.; Meyfroidt, P.; Weng, L.; et al. Anticipatory Governance for Responsible Investment in Energy Transition Minerals in the Western Congo Basin. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2025, 24, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, E.; Nykvist, B.; Borgström, S.; Stacewicz, I.A. Anticipatory Governance for Social-Ecological Resilience. Ambio 2015, 44, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, P.; Plant, R. Hacking: Field Notes for Adaptive Urban Planning in Uncertain Times. Plan. Pract. Res. 2022, 37, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosoughi, S.; Ahmadi, M. Critical Thinking Disposition or Proactive Personality as Predictors of Academic Resilience in Nursing Students. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandeli, K. Public Space and the Challenge of Urban Transformation in Cities of Emerging Economies: Jeddah Case Study. Cities 2019, 95, 102409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zhao, X. Social Media Overload and Proactive–Reactive Innovation Behaviour: A TTSC Framework Perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 75, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Ma, X.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Y. Proactive Maintenance Scheduling in Consideration of Imperfect Repairs and Production Wait Time. J. Manuf. Syst. 2019, 53, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A. Turning a Town Around: A Proactive Approach to Urban Design; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mantey, D. Planning Local Centres in Outer Suburbs—The Need for a Proactive Approach towards Planning in Post-Socialist Poland. Cities 2024, 150, 105032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Developing a Guiding Framework Based on Sustainable Development to Alleviate Poverty, Hunger and Disease. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2023, 18, 432–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Effect of People on Placemaking and Affective Atmospheres in City Streets. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 3389–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Gu, Y.; Han, H. Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Urban Planning Implementation Effectiveness: Evidence from Five Urban Master Plans of Beijing. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 108, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhu, L.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Q. Deep Learning-Based Geospatial Analysis of the Heterogeneous Effects of Street-Edge Features on Informal Vending Dynamics: A Case Study of 15,904 Vendors in Changsha, Hunan, China. Cities 2026, 168, 106486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Detecting the City-Scale Spatial Pattern of the Urban Informal Sector by Using the Street View Images: A Street Vendor Massive Investigation Case. Cities 2022, 131, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciniegas, L. The Foodscape of the Urban Poor in Jakarta: Street Food Affordances, Sharing Networks, and Individual Trajectories. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2021, 14, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Park, I.K. Changes in Communal Housing in North Korean Cities with Limited Marketization: Increasing Informal Activities and Appropriation of Public Space. Cities 2025, 158, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumedah, G.; Bwire, H.; Jones, S.; Mwauzi, A. Disparities of Potential and Perceived Access to Socioeconomic Activities in Informal Urban Communities in Kumasi-Ghana and Dar es Salaam-Tanzania. Urban. Plan. Transp. Res. 2024, 12, 2345089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald Hope, K. Informal Economic Activity in Kenya: Benefits and Drawbacks. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2014, 33, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bański, J. Newcomers in Remote Rural Areas and Their Impact on the Local Community—The Case of Poland. Land 2025, 14, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Revisiting Urban Street Planning and Design Factors to Promote Walking as a Physical Activity for Middle-Class Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome in Cairo, Egypt. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2024, 21, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, A. Moveable Feasts: Reflections on Shanghai’s Street Food. Food Cult. Soc. 2018, 21, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malasan, P.L. Feeding a Crowd: Hybridity and the Social Infrastructure behind Street Food Creation in Bandung, Indonesia. Southeast Asian Stud. 2017, 6, 505–529. [Google Scholar]

- Slobodníková, K.; Tóth, A. Planning for People with People: Green Infrastructure and Nature-Based Solutions in Participatory Land-Use Planning, Co-Design, and Co-Governance of Green and Open Spaces. Land 2025, 14, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.L. Out of the Blue: Wild Cards and Other Big Future Surprises: How to Anticipate and Respond to Profound Change; Arlington Institute: Berkeley Springs, WV, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Cairenes’ Storytelling: Pedestrian Scenarios as a Normative Factor When Enforcing Street Changes in Residential Areas. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A. The Architecture of the City; Ghirardo, D., Ockman, J., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; ISBN 0262181010. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Academy Editions: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Swai, O.A. Architectural Dynamics of Street Food-Vending Activities in Dar Es Salaam City Centre, Tanzania. URBAN Des. Int. 2019, 24, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]