Abstract

This study investigates how urban park co-governance fosters a sense of belonging among residents and advances the Right to the City. It examines the role of parks in mitigating spatial fragmentation, inadequate living conditions, and relational disconnection in high-density urban environments. As essential green infrastructure, urban parks play a vital role in promoting spatial justice, community cohesion, and resident well-being. Drawing on Henri Lefebvre’s Right to the City framework, this study introduces the concept of the Right to Urban Park, conceptualised as a bundle of rights: freedom (appropriation), individualisation (socialisation), habitat and to inhabit (differentiation), and key point participation. Focusing on the governance and self-governance of parks in high-density cities, this research mixed qualitative and quantitative methods to analyse a representative case in central Shanghai. The findings show that participation, collective action, and co-governance in urban parks effectively support the Right to the City. Integrating the Right to Urban Park framework into park planning and management enhances diversity, equality, and inclusion, thereby improving urban well-being. This framework plays an important role in fostering enfranchisement, individuation, and association processes that strengthen recognition, sense of belonging, and well-being.

1. Introduction

In the context of contemporary high-density urban environments, the opportunities of economic, social, and cultural prosperity are increasingly undermined by deepening inequality and spatial injustice. As cities intensify and diversify, fragmentation, uneven development, and gentrification erode the social fabric, exacerbating the severe “dissolution, dislocation, or conflagration” of communities noted by Jean-Luc Nancy [1] in the last decades of the twentieth century. Reduced welfare investment weakens social infrastructural models designed to support integration, dialogue, and collective identity. Among these, urban parks—primary institutions that provide not only spaces for physical activity but also arenas for interaction and enjoyment in everyday life—diminish their function to accumulate cultural and social capital [2]. This paper explores how urban parks, when reimagined through the principles of the Right to the City (RTTC) and participatory governance, can serve as critical infrastructure for urban justice, resilience, and inclusive transformation.

Urban parks, once central to the social and cultural life of cities, are increasingly marginalised in urban agendas, often reducing their functions to physical activity and recreation. As cities undergo neoliberal transformations—marked by competitiveness, privatisation, and technocratic governance—the capacity of parks to challenge marginalisation and oppression by fostering solidarity, collaboration, integration, and identity is eroded. Yet, this contrasts with a growing body of research and policies for sustainable development that recognises the relevance of parks as essential infrastructure for urban justice, particularly regarding vulnerable communities [3]. Its implementation in governance institutions, strategies, and actions affirming parks as key, irreplaceable infrastructure for fostering democracy, relationality, and social inclusion is inadequate [4,5,6,7,8]. This undermines their historical role to guarantee the realisation of the RTTC through collective appropriation and the production of urban space and time [9].

The RTTC, first articulated by Henri Lefebvre in 1968, provides a critical framework for analysing issues of urban justice, democracy, and governance. Lefebvre outlined this right not merely as access to urban resources, but as a “superior form of rights” encompassing a five-pillar framework: the right to freedom (appropriation), the right to individualisation in socialisation, the right to habitat, the right to inhabit, and participation [9]. He maintains that urban parks are not passive amenities but active spaces of citizenship, where diverse communities negotiate identity, belonging, and shared futures, moderating tensions between exclusion and inclusion, and between self-management and co-governance. The RTTC is also recognised by the United Nations New Urban Agenda [10] as a core reference for a pathway to ensure that “all people have equal rights and access to the benefits and opportunities that cities can offer”, acknowledging the primary role of green infrastructure for the sustainable development of human habitats and the well-being of urban communities [11].

Well-being and sense of belonging, as subjective experiences of citizens, have become key concerns in urban research. A sense of belonging is a subjective feeling of deep connection with social groups, places, and individual and collective experiences [12]. It is influenced by urban conditions determined by physical spaces and urban amenities [13]. Well-being is also inherently subjective, as it refers to an individual’s evaluation of their life circumstances [14] that is related to collective experiences and normativities of living in an enjoyable and just environment [15].

Previous studies have confirmed the important role of urban parks in fostering both well-being and a sense of belonging [16,17,18]. Nevertheless, although their mental health benefits are well documented [19,20], how such spaces shape visitors’ subjective experiences remains underexplored. While many confirm the role of parks in fostering them, little is known about how citizens actively shape these perceptions through participatory governance mechanisms. Some studies suggest that proximity and volunteering are key factors linking parks and subjective perceptions, yet few studies have integrated them into a co-governance framework.

Co-governance is increasingly recognised as a potential pathway to realising the Right to the City by institutionalising participation and addressing diverse needs. Emerging forms of governance arrangements in urban green infrastructure (e.g., the Cuban organopónicos urban gardens and farms in the 1990s, created as a response to the US trade embargo) have increasingly focused on rights-holder engagement in Collaborative Governance in partnership with public institutions. Their aim to integrate environmental and health functions with resilience, belongingness, and holistic well-being has become primary [21,22]. They operate to realise spatial and green justice [23] to drive wider inclusive, equitable, and sustainable urban transformations [24,25].

This paper poses the following research questions:

Q1: How do the dimensions of the ‘right to the city’ in urban parks influence residents’ subjective well-being (WB) and sense of belonging (SoB)?

Q2: What roles do co-governance motivation (CM) and behaviour (CB) play in linking urban park rights to residents’ perceptions?

Q3: What pathways or measures does the park’s shared governance system rely on heavily to achieve this, and how do they affect WB and SoB?

To address these questions, this study employs structural equation modelling (SEM) to develop measurement scales for urban park rights and residents’ willingness and behaviour to participate in co-governance, and to investigate how these factors influence residents’ well-being and sense of belonging. Using Zhabei Park in Shanghai as a case study, the research provides empirical insights into the interaction between governance and self-organisation, illustrating how urban parks can function as platforms for safeguarding urban rights and promoting inclusive and sustainable transformation.

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Background

The RTTC offers a transformative framework for urban politics that foregrounds the inhabitant’s role in shaping urban space. It is “a right to change ourselves by changing the city” [26] that, as Purcell maintains, demands a “new urban politics of the inhabitant” and marks the beginning of a new urbanity of appropriation and enfranchisement. It concerns much more than the individual liberty to access urban resources, comprehensively focusing on environmental and urban justice, as well as urban planning and governance.

Contemporary interpretations of the RTTC advance its domain and specify its articulation. Scholars such as David Harvey [27], Don Mitchell [5], and Mark Purcell [28] emphasise that this right is essential to affirm the diverse needs, desires, and practices of increasingly heterogeneous urban communities and rights-holders. It ensures their adequate representation, engagement, and empowerment at all levels of governance. Ash Amin [29] argues that this entitlement supports broader participation, equality, and the inclusion of diverse identities, contributing to the realisation of a “good city” model grounded in multidimensional registers of solidarity: rights, repair, relatedness, and re-enchantment. Similarly, the United Nations-Habitat Group summarises the RTTC as a vision of cities for all. By incorporating it into the core vision for sustainable city and government development, it adopts its radical anti-discriminatory normative principle for the production and inhabitation of just, safe, healthy, accessible, affordable, resilient, and sustainable cities and human settlements that foster universal prosperity and quality of life [11].

While these contributions establish the RTTC as a normative and aspirational framework, debates remain regarding its operationalisation in empirical contexts such as urban parks and everyday spatial practices. Pilot projects for conjunctural operational, institutional, and constitutional arrangements have developed arrangements that capture the specificity of each context and balance public and private interests, collective and individual practices, and hierarchical and horizontal models [2,30]. Their solutions focus on mobilising local actors, intensities, customary practices, and values, and demand real, active, and proportional participation of all right-holders.

The first pillar of the RTTC framework posits the right to freedom, emphasising appropriation processes of liberation from domination and alienation. It concerns the role of space in guaranteeing the collective capacity to realise human potential through conscious action that transcends necessity through the development of technology and social organisation for creative, cultural, and intellectual pursuits. The second pillar, the right to individualisation in socialisation, calls for urban environments that foster autonomous identity formation through appropriation via sociospatial interaction. It posits the identitarian constitution as a dynamic and collective process involving constraints, capacities, and desires produced through vibrant social interaction and a rich social life, which resist the forces that isolate, homogenise, and dominate the individual. The third and fourth pillars, the right to habitat and to inhabit, refer to the process of differentiation by which people transform hegemonic abstract space into appropriated differential space. It involves actions of creative individuation, combining environmental, cultural, and relational conceptions and practices of maximal difference that embody history, ecology, culture, and the social meanings inscribed in the social space.

In this paper, we propose an articulation of the RTTC in the context of green infrastructure as the Right to Urban Park (RTUP). Regarding the freedom and individualisation in socialisation components, this refers to agencies and affordances granted by more-than-tangible dimensions. Parks are quintessential spaces of appearance that embody the multiplicity and complementarity of collective worlds—places where individuals gather, engage in collective action, imagination, aesthetic redistribution, and discourses on public concern matters, such as possible futures, ecosystem crises, and physical and mental health through physical activity. They foster social sustainability by facilitating relationality, encounters, recognition, and mutual understanding among strangers liberated from their social and private roles [31]. Effective park governance encourages activities that bring people together and facilitate interaction across genders, age, ethnicity, and social class [32]. It creates opportunities for forming new social relationships, connections, and solidarity [33]. Environmental inclusiveness is widely recognised as a key component of the RTTC in multicultural societies [34], with biophilia helping to accommodate different and conflicting preferences and practices of diverse groups [35].

RTUP’s right to habitat is regarding the cultural ecosystems and habitats created in the park, which are a complement of the emplaced affirmation of equality through emplaced cross-communing that relies on stable care and the sense of place [36]. Public parks enable the formation of groups, support collective activities, and foster different material, cultural, and spiritual habitation forms [37]. As suggested by Rozzi’s [38] concept of biocultural ethics, the RTUP claims to resist biocultural homogenisation and promotes habitat creation. This enhances the sense of belonging, leading to a deeper connection between people and places, promoting harmony and well-being [39]. These habitats have a rich influence on cultural practices, fostering collective individuation, belonging, connection, inspiration, and escapism [40].

RTUP’s right to inhabit, and the benefits of parks, have become an important research theme in the fields of urban planning, environmental psychology, and public health. Parks are a key consideration for homebuyers and play a vital role in shaping neighbourhood identity [41]. Prior studies confirm that proximity to parks influences housing prices [42] and contributes to quality of life by enhancing the residential environment, fostering social relations, and supporting healthy interactions. Parks promote physical and mental well-being by providing spaces for activity, social engagement, and enjoyment [43]. As essential components of urban infrastructure, parks offer platforms for outdoor recreation [44], generating positive emotions and reducing stress [45].

RTUP’s right to appropriation involves people’s ability to appropriate by physically accessing, occupying, and using urban space free of any charge [46,47]. Appropriation is a field of relations involving the relation of time with space [9]. It is the first territorial phase of relational territorialisation, preceding association and stabilisation. Its sociospatial process involves participation as crucial to sociality [48]. As postulated in territoriology research [49,50], it operates through acts of deterritorialisation that are not univocal but can bring about either emancipatory or dominating overcoding outcomes. Bhandari [51] stated that the right to appropriation in urban parks plays a significant role in increasing the sense of belonging and enhancing social cohesion. This right is proposed as an entitlement that develops associative social and spatial cohesion through permanent emancipatory emplaced processes hinged in green urban infrastructures.

Collaborative Governance (co-governance) is increasingly recognised as a governance approach that extends beyond electoral representation, as it involves non-state actors, including community groups, private organisations, and NGOs, in decision-making on spatial management, and is a significant reflection of the right to participation. In this process, examining behaviours and motivations is vital for understanding and enhancing the effectiveness of public participation. Emerson et al. put motivation at the centre of the dynamics of collaboration to explain the ability to sustain collaboration and joint action [52]. Co-governance may yield both positive and negative experiences, as Satorras et al. [53] show that co-produced urban climate planning can enhance inclusion and coordination; however, unequal representation and limited decision-making authority for certain groups expose the risk that co-governance may fall short of delivering genuinely equitable outcomes. Latham and Tiago, on the other hand, view motivation as a mediator of participatory behaviour [54,55]. Purcell [46] emphasised the importance of city dwellers’ active and continuous participation in any decision that contributes to the production of urban space. Past research has demonstrated a positive correlation between public participation and feelings of safety and belonging [56]. Parks create tools through participatory rights to establish custodianship obligations for co-created, differential, agonistic, and place-based spatial practices. Resident participation in park management or planning can be effective in balancing demand, creating a sense of belonging to the park, and increasing park utilisation [57]. Yet, despite growing recognition, few studies explicitly link co-governance mechanisms with subjective well-being and belonging, leaving a significant gap in empirical research.

The study further found that urban park users develop unique emotional bonds with these places, which in turn enhance their subjective experiences of belonging and community well-being [58]. Belongingness and well-being have long been central topics in psychology, and with the growing interest in belongingness research, these concepts have been widely applied in studies across different groups, including older adults [59,60], youth, and the education sector [61,62]. Existing research has confirmed the positive association between park visitation and well-being [63]. Belongingness has also become an important lens in environmental psychology and community studies [64]. Accessible public spaces provide a low-cost means of strengthening interpersonal ties and fostering a sense of belonging among community members [65]. Moreover, the use of public space has been shown to enhance users’ sense of belonging and mitigate inequalities arising from differences in socioeconomic status [66]. Among various types of public spaces, green infrastructure, particularly urban parks, has been identified as strongly associated with the development of visitors’ sense of belonging [67]. Efforts to increase belonging promote more frequent positive interracial contact [56].

Although there has been a rich body of research constructing a theoretical framework for the Right to the City, citizens’ subjective feelings, and shared governance, few studies have analysed the mechanisms by which RTTC aspects shape subjective feelings. Secondly, urban park studies rarely address the mediating role of shared co-governance motivations and behaviours. Thirdly, although proximity and volunteering are considered influential, they are rarely included in integrated governance frameworks. Based on this, there is a need for new theoretical models and empirical analyses to validate the above issues.

2.2. Research Hypothesis

This study is guided by the following research questions and hypothesises:

- Does the Right to Urban Parks influence residents’ subjective well-being and sense of belonging through different pathways?

- What role does co-governance play in the relationship between urban park rights and residents’ subjective perceptions?

- Is there an interaction effect between co-governance motivation and co-governance behaviour?

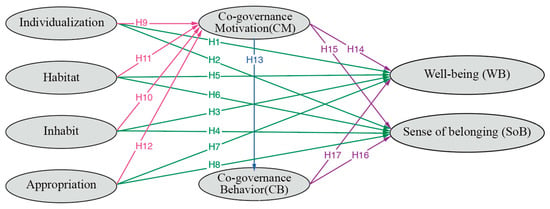

H1 to H8 (Figure 1-green) explain that citizens’ subjective feelings are directly affected by the city’s Right to Park.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model of Right to Park, Co-governance and Subjective Perception.

H1: What It Is and Why It Matters is positively associated with residents’ well-being.

H2: Individualisation is positively associated with residents’ sense of belonging.

H3: Inhabit is positively associated with residents’ well-being.

H4: Inhabit is positively associated with residents’ sense of belonging.

H5: Habitat is positively associated with residents’ well-being.

H6: Habitat is positively associated with residents’ sense of belonging.

H7: Appropriation is positively associated with residents’ well-being.

H8: Appropriation is positively associated with residents’ sense of belonging.

H9 to H12 (Figure 1-pink) explain the pathways through which the Right to Urban Parks affects motivation to participate.

H9: Individualisation is positively associated with co-governance motivation.

H10: Inhabit is positively associated with co-governance motivation.

H11: Habitat is positively associated with co-governance motivation.

H12: Appropriation is positively associated with co-governance motivation.

H13 (Figure 1-blue) hypothesises pathways by which co-governance motivation influences co-governance behaviour.

H13: Co-governance motivation is positively associated with co-governance behaviour.

H14 to H17 (Figure 1-purple) explain the effect of co-governance motivation and co-governance behaviour on well-being and sense of belonging.

H14: Co-governance motivation is positively associated with residents’ well-being.

H15: Co-governance motivation is positively associated with residents’ sense of belonging.

H16: Co-governance behaviour is positively associated with residents’ sense of belonging.

H17: Co-governance behaviour is positively associated with residents’ well-being.

3. Research Design

The research design for this study adopts a comprehensive approach to understand the role of urban parks in advancing the Right to the City. It combines qualitative and quantitative methodologies to ensure a robust examination of theoretical models and empirical data. The research design integrates structural equation modelling to validate theoretical constructs, spatial ethnography TESS [68] to capture behavioural and experiential insights, and case study analysis to contextualise findings. TESS data were collected through participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and expert interviews [68]. The aforementioned experimental methods can provide data for the qualitative experiments in this paper. With the park director’s permission, data on park usage, including the number of people entering and exiting the park, were obtained using cameras. Seven high-frequency public spaces within the park were identified for detailed surveys.

3.1. Scale Design

A preliminary scale was developed and subsequently refined through in-depth interviews, pilot testing, and expert review. Its design was informed by prior studies and validated instruments on well-being, sense of belonging, and community participation. The final questionnaire consisted of three sections—urban park rights, co-governance, and subjective perceptions—along with demographic information of respondents (including age, gender, residence, and educational background).

The section on urban park rights was developed from Lefebvre’s framework of the Right to the City and was adapted based on theoretical foundations and relevant empirical studies. Previous research has demonstrated that motivations for park activities influence patterns of engagement [69]. This study to the theoretical framework proposed by Emerson and the Community Participation Scale [70], Collaborative Governance Scale [71], and Citizen Trust and Co-production Scales [72] and designed this questionnaire in conjunction with the park space.

The measurement of belongingness and well-being has been widely established in the literature. For sense of belonging, this study referred to the Sense of Belonging Instrument (SOBI) originally developed by Hagerty et al. [61], which includes two dimensions, as well as the 12-item General Belongingness Scale (GBS) proposed by Malone, which is considered a reliable measure of overall belongingness, and the School Belonging Scale (SBS), a 10-item instrument including both positively and negatively worded items [73]. Mellinger et al. [74] developed an 8-item SBS, derived from SOBI and GBS, which provides a concise and context-sensitive tool for measuring belongingness. For happiness and well-being, this study adopted widely recognised measures: the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire (OHQ) for happiness and the Flourishing Scale (FS) for well-being. The FS uses exclusively positive wording and has been validated across diverse cultural contexts. In the Chinese research context, the scale developed by Diener et al. [75] has been adapted into a Chinese version of the FS [76] and has been demonstrated to be a valid and reliable tool.

The initial scale was further reviewed by ten experts specialising in urban design, landscape architecture, sociology, and English studies. Following this expert evaluation, the preliminary questionnaire—including both measurement scales and demographic variables—was piloted. Revisions were made based on the contextual relevance to urban parks, expert feedback, and findings from in-depth interviews. Items with overlapping meanings were consolidated, and those failing to meet reliability and validity thresholds were removed.

The initial test yielded a total of 154 valid responses. Before the formal survey, we conducted a preliminary test using the revised questionnaire, which comprised three components: reliability analysis, questionnaire item analysis, and exploratory factor analysis. Reliability analysis showed strong internal consistency across all dimensions (Cronbach’s α = 0.774–0.902; overall α = 0.944) and item analysis confirmed that all items demonstrated strong discrimination and internal consistency, with critical ratio (CR) values ranging from 6.778 to 12.538 (p < 0.001) and item–total correlations between 0.489 and 0.700, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.40. Skewness and kurtosis both fall within the range [−2, +2], which essentially confirms that the data conforms to a normal distribution. Subsequently, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed, yielding a KMO value of 0.912 and a significant Bartlett’s test (p < 0.001), indicating sampling adequacy. Eight factors with eigenvalues above 1 were extracted, explaining 74.203% of the total variance, and all factor loadings exceeded 0.50 without cross-loadings, demonstrating a clear and theoretically consistent factor structure. These results confirm the preliminary validity and reliability of the scale (Appendix A) and provide a robust basis for the subsequent formal survey.

3.2. Case Study Identification and Description

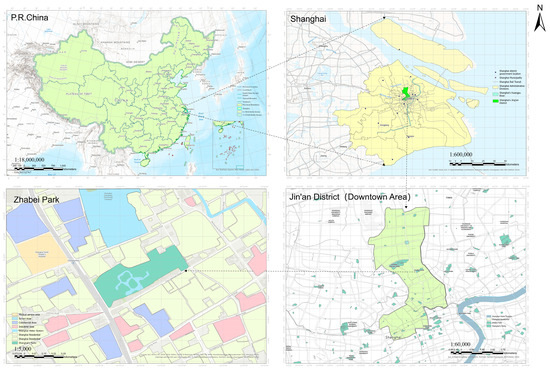

The author examined seven city parks in the city centre area, and Zhabei Park, with its high density, strong accessibility, and multi-body management, makes it an ideal case to test how the Right to the Park and co-governance can enhance the sense of belonging and well-being. Zhabei Park (Figure 2), although medium-sized, demonstrates high levels of utilisation and activity. This is attributed to its effective administration, accessibility, strategic location, appealing scenery, and comprehensive facilities. These characteristics make Zhabei Park an ideal research object for this study.

Figure 2.

Location map of Zhabei Park, Jin’an District, Shanghai, P. R. China.

Zhabei Park is located in the densely populated Jing’an District, one of Shanghai’s core urban areas, with a population density exceeding 25,000 people per square kilometre. Within its catchment area, the park serves over 40 neighbourhoods, 2 large shopping malls, 3 small shopping districts, 6 schools, 2 hospitals, and 1 university campus. Zhabei Park is free and easily accessible, with multiple modes of transportation—buses, metro stations, roads, and car parks—within a 0.5 km radius. According to data from the park’s smart management system, the number of visitors ranges around 13,000 on weekdays and approximately 16,000 on weekends.

3.3. Research Methods

The questionnaire (Appendix B) employed a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very disagree to 7 = very agree) [77]. Based on the recommendation that the sample size should be five to ten times the number of questionnaire items, this study aimed to collect 300 valid responses. In the pre-survey, 100 questionnaires were distributed. For the main survey, 300 questionnaires were distributed across seven high-frequency public spaces identified using self-monitoring cameras. After excluding responses with identical answers, incomplete submissions, and incorrect validation questions, 275 valid responses were obtained (Table 1). Data collection occurred between March and July 2025.

Table 1.

Demographic Variables of respondents.

The majority of respondents were male, with the highest educational attainment concentrated at the undergraduate and three-year college levels. Retired individuals accounted for the largest share of participants. Visitors were primarily from middle-income groups, and most lived within one kilometre of the park. In terms of residential duration in Shanghai, the largest proportions of visitors had lived in the city for 2–5 years and 5–10 years.

A qualitative study was conducted using the Toolkit for the Ethnographic Study of Space (TESS). A total of 35 respondents, including park visitors, park managers, Volunteer Association members, and relevant experts, were interviewed. The interviews focused on satisfaction with park management, experiences of park usage, restrictions encountered, daily activities, and respondents’ sense of belonging. Field observations further examined 18 resident activity networks and the role of the Volunteer Association in coordinating shared use of space. Observations conducted with volunteer organisations further explored the frequency of park activities and the variables influencing that frequency. Complementary field observations were carried out with volunteer organisations to examine patterns of spatial use, activity frequency, and organisational dynamics.

4. Results

The results of this study are stated in four parts: validation factor analysis to prove the validity of the theoretical model, testing of the theoretical model to validate the hypothesis, difference analysis to test the interrelationship between distance and subjective feelings, and qualitative findings to validate the specific paths of co-governance.

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To ensure that the structural equation measurement model is reliable, this paper first used CFA to validate (Figure 3). The validity of the theoretical model was confirmed by the Reliability Analysis, Correlation Matrix, Discriminant Validity, and CFA model fit. The scale data were analysed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) within the structural equation modelling (SEM) framework [78,79]. Ensuring reliability and validity is essential for producing consistent and accurate research results, forming the foundation for meaningful conclusions.

Figure 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis model of Right to Park, Co-governance and Subjective Perception.

Using SPSS 27.0, Cronbach’s Alpha was employed to assess the internal consistency of the scale [80]. The results (Table 2) showed that all items exceeded the threshold value of 0.8, indicating high reliability. Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s sphericity tests were conducted to evaluate construct validity. The KMO value of 0.952 indicated suitability for factor analysis, while Bartlett’s test yielded a Chi-square value of 5258.283 (df = 406, p + 0.000), rejecting the null hypothesis and confirming the validity of the scale’s structure.

Table 2.

Factor Loadings, Reliability, and Validity Statistics of the Scale.

The composite reliabilities (CR) all exceeded 0.8, which meets the requirement of consistency of latent variables for structural equation modelling. In terms of convergent validity, with Inh (0.829), Hab (0.892), and the superior score of CB (0.891), the topic explains its latent variables better. The average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct was greater than 0.5. Standardised factor loadings (Loadings) were above 0.7 for all scale items, with some slightly lower but still within acceptable limits.

Discriminant validity (Table 3) was evaluated by comparing the AVE square root values with the maximum absolute correlation coefficients between the factors. The square roots of the AVE values for each construct are greater than the inter-construct correlations, confirming adequate discriminant validity [81].

Table 3.

Correlation Matrix and Discriminant Validity of Constructs of the Scale.

The goodness-of-fit of the measurement model can be evaluated using indices such as the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI). Structural equation modelling was conducted using AMOS to process the collected dataset. The model’s fit was evaluated using the indicators presented in Table 4. The results are as follows: X2/df = 1.359 (<3.000), RMSEA = 0.035 (<0.08), GFI = 0.896 (>0.900), AGFI = 0.871 (>0.900), NFI = 0.915 (>0.900), ILI = 0.978 (>0.900), and TFI = 0.977 (>0.900). These fit indices indicate that the model has a good overall fit [82,83,84]. Additionally, the results confirm the strong distinguishing validity of the variables. Thus, the hypotheses and assumptions underlying the theoretical framework were verified.

Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis model fit results of the Scale.

4.2. Goodness-of-Fit Testing of the Measurement Model

Based on the results of the validation factor analysis, this paper further validates the hypothesised model using the path of structural equation modelling (Figure 4). The goodness-of-fit of the measurement model can be evaluated using indices such as the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI). Structural equation modelling was conducted using AMOS to process the collected dataset. The model’s fit was evaluated using the indicators presented in Table 5. The results are as follows: X2/df = 1.453 (<3.000), RMSEA = 0.041 (<0.08), GFI = 0.888 (>0.900), AGFI = 0.862 (>0.900), NFI = 0.906 (>0.900), ILI = 0.969 (>0.900), and TFI = 0.968 (>0.900). Although the GFI and AGFI values are slightly below the conventional threshold of 0.900, they are still within an acceptable range, particularly given the complexity of the model and sample size. Collectively, these indices suggest that the hypothesised model demonstrates an acceptable to good fit with the observed data.

Figure 4.

Structural equation model path coefficient results of the scale.

Table 5.

Structural Equation Model Analysis Model Fit Results of the Scale.

The structural path coefficients and their significance levels are presented in Table 6. The results show that several paths are statistically significant. Paths 1–4 represent the effects of the independent variable on one of the mediators, CM. Path 5 illustrates the interaction between CM and CB, highlighting co-governance as an important factor. Paths 6–9 show the effects of the mediating variables on the dependent variables. Finally, Paths 10–17 demonstrate how the independent variable—urban park rights—interacts with subjective perceptions of well-being (WB) and sense of belonging (SoB).

Table 6.

Structural Equation Model Path Analysis Results of the scale.

Consistent with the research hypothesis, the latent variables in the independent variable (right to urban park), Individualisation (Ind), Habitat (Hab), Inhabit (Inh), and Appropriation (App) all have significant positive effects on co-governance motivation (CM). The CM and co-governance behaviour (CB) path coefficient is the highest of all paths (0.761), which proves that CM strongly influences CB. The effects of App (0.370) and Ind (0.386) were relatively greater. CM had a significant effect on CB and well-being (WB 0.429).

In addition, CB positively influenced WB (0.431), and App also directly influenced WB (0.154). Notably, Ind also directly influenced belonging (SoB, 0.293). However, some of the hypothesised paths, including from CM to SoB and from Inh or Hab to SoB, were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). These paths suggest that the direct effects between these latent variables are not significant and may be influenced by other paths or indirect effects. Overall, the results of this path analysis confirm the existence of mediating paths in structural equation modelling.

The mediating effect (Table 7) of behavioural intention was tested using the bootstrapping method with 5000 resamples. By examining whether the confidence intervals include zero and the significance of the p-values, the results of the indirect path tests can be verified. Paths 1–4 represent the relationships between the independent variable and the mediating effects, and all four paths meet the validation criteria. This indicates that the influence of the independent variable on subsequent joint pathways operates through the enhancement of CM, which in turn affects CB. Paths 5 and 6 reflect the relationships between the mediators and the dependent variables; the significance of Path 5 and the non-significance of Path 6 suggest that SoB is less sensitive to this pathway. Paths 7–14 test the full chain of mediation effects, showing that the independent variable (RtuP) influences the dependent variables (WB, SoB) through its impact on CM and subsequently CB. Among them, Path 7 and Path 10 demonstrate the strongest and most stable chain effects, although the overall influence on SoB is weaker than on WB. These findings confirm the research hypotheses, indicating that despite the non-significance of Path 6, the overall mediating pathway remains valid under the influence of specific dependent variables. In sum, the path and mediation analyses validate the theoretical model by confirming three routes from the independent variable to the dependent variables: (1) the direct path, (2) the indirect path via CM, and (3) the chain mediation path through CM and CB.

Table 7.

Results of Mediating Effect Tests of the scale.

4.3. Test of Difference

Using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc comparisons, this study examined the relationship between residential distance and park visitors’ well-being (WB) and sense of belonging (SoB). The ANOVA results (Table 8) revealed significant group differences in WB (F = 3.02, p = 0.030). Post hoc Least Significant Difference (LSD) tests indicated that Groups 1 and 2 scored significantly higher than Group 4 (1 > 4, 2 > 4), with mean values showing a declining trend as distance increased (1 = 4.912, 2 = 4.747, 3 = 4.726, 4 = 4.196). Similarly, SoB also exhibited significant group differences (F = 4.00, p = 0.008). The LSD test further demonstrated that Groups 1, 2, and 3 scored significantly higher than Group 4 (1 > 4, 2 > 4, 3 > 4), suggesting stronger sensitivity to distance (1 = 4.746, 2 = 4.550, 3 = 4.633, 4 = 3.912). Taken together, the results indicate that visitors living closer to the park reported higher levels of WB and SoB, whereas those living the farthest consistently scored the lowest on both measures.

Table 8.

Analysis Of Differences Between Different Distance Variables on WB And Sob.

4.4. Qualitative Findings

Qualitative data collected through TESS included feedback from individuals of different ages regarding the park’s infrastructure, group activities, management, and landscaping. A total of 35 participants, aged 16 to 78, were interviewed. Among them, 17 were identified as female and 18 as male. Most participants (32) visited the park at least once daily, while three were occasional visitors. All participants reported that adhering to the park’s management regulations did not restrict their freedom to engage in activities or use any park facilities. Additionally, 80% of respondents confirmed that the park meets users’ needs. Among the activities mentioned, 12 participants engaged in outdoor physical activities, 7 visited the park for leisure or relaxation, and 16 participated in group activities.

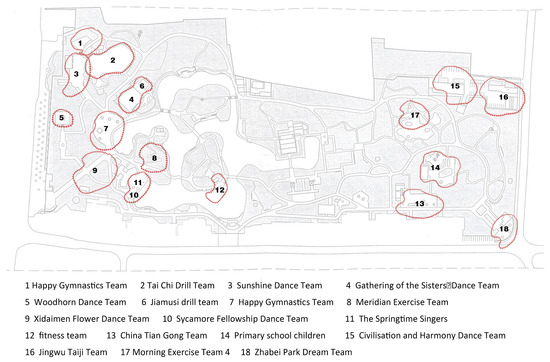

Data on daily life and informal organisations in the park were collected through fieldwork observations and interviews with two key stakeholders: Mr Zhou, the Director of Zhabei Park, and Grandma Xue, the Chair of the Volunteer Association. These findings identified and mapped 18 active resident activity networks (Figure 5). Many of these groups share the same park spaces but use them at different times for various activities. Regular collaboration between these groups and park administration has established the park as a primary habitat for citizen engagement. Social networks are a vital element of the public sphere, providing independent arenas for discussion, sharing, and collaboration [85]. Social media has played a significant role in facilitating the formation and development of these networks. Among the 18 identified groups, 15 maintain active digital platform communities on WeChat, enabling effective communication and collective decision-making.

Figure 5.

Distribution of active groups in Zhabei Park (Base map provided by the Park Management Office).

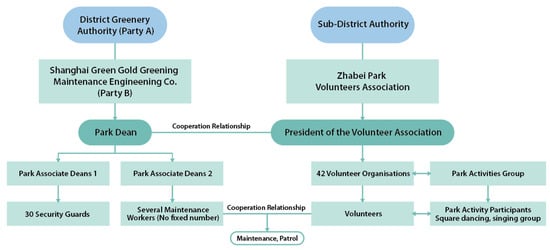

Through the content of the in-depth interviews, the research team summarised that the main pathway for diverse engagement in parks (Figure 6) is through volunteer activities. To facilitate public activities, the park established a Volunteer Association, which included 43 organisations at the time of the study. Each organisation is required to have a minimum of 10 members, a designated representative, and an agreement with the park and the Volunteer Association regarding park usage terms. In exchange for access to park spaces, organisations provide voluntary labour. For instance, the Jiamusi City Gymnastics Team, the largest group, with over 200 members (no fees charged), holds daily gatherings and serves as wardens for two volunteer events every month. The results of the qualitative study showed that in Zhabei Park, the Volunteer Association operates as an autonomous, cooperative organisational structure supported by park administration. It contributes to park maintenance, resolves disputes, and fosters mutual help among residents. The association serves as a key institution for promoting RTTC through participation and appropriation. It exemplifies effective community engagement and nurtures a strong sense of stewardship and belonging within the urban context.

Figure 6.

Zhabei Park Co-governance framework.

Several respondents highlighted the positive impact of participation on well-being. Grandma Zhang, a 75-year-old volunteer, shared: “I feel younger as I participate in the park management process, and I find personal value.” Similarly, a 70-year-old woman who visits the park regularly with her husband remarked: “Participating in the Jiamusi Drill Team Square Dance helps my physical and mental health, and I have made more friends here.” A 60-year-old male participant stated: “My well-being steadily increased after joining group activities, which prevented me from retiring into a life of boredom.”

Out of the 35 respondents, 16 were members of volunteer organisations, predominantly involved in square dancing and singing groups. Most participants, who are retired, reported that these activities enhanced their social interactions and provided a sense of recognition, belonging, and involvement.

5. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that urban park rights, as independent variables, influence residents’ well-being (WB) and sense of belonging (SoB) through differentiated pathways. Individual factors (Ind) and residential habitat (Hab) not only exert direct effects on psychological outcomes but also act indirectly through co-governance motivation (CM) and co-governance behaviour (CB).

The direct path analysis of the structural equation model confirms the significant role of urban park rights in shaping WB and SoB. Although only individualisation and habitat showed significant direct effects, this finding suggests that parks are not merely recreational spaces but also vital social arenas that foster interactions among strangers and strengthen community identity [86]. These results are consistent with prior studies that emphasised the importance of individual-level social motivation and living environments for psychological well-being [87]. Inhabit (Inh) and park Appropriation (App) demonstrated significant indirect effects through the CM to CB pathway on WB. This suggests that environmental features of parks may affect through the mediating processes of motivation and participation, reinforcing the importance of co-governance pathways. Previous studies have similarly shown that fulfilling psychological needs in nature is positively related to various dimensions of well-being, including happiness, affect, and life satisfaction [86]. This aligns with Lu et al., who found that external drivers, when not fully internalised, often require mediation through behavioural intentions or actual actions to affect subjective well-being [88]. WB is more immediately influenced by an individual’s perception, evaluation, emotions, and experiences [89,90]. Park quality, quantity, and accessibility are significantly correlated with well-being [91]. Short-term experiences or leisurely relaxation in parks can foster feelings of well-being, whereas the development of a sense of belonging involves more complex pathways, particularly within diverse urban settings, where symbolic boundaries and latent exclusion persist [92,93]. Participation is a key condition for enhancing a sense of belonging [56].

Co-governance plays a critical mediating role in shaping subjective perceptions. Motivation influences behaviour, which in turn forms an essential pathway to subjective well-being. Notably, the mediation mechanisms differ between CM and CB. CM demonstrates both direct and indirect effects on WB, underscoring the central role of participatory motivation in enhancing psychological well-being. However, its direct effect on SoB is not significant, suggesting that the formation of belongingness relies more heavily on actual community participation. CB shows stable positive effects on both dependent variables, highlighting its bridging role between individual cognition and psychological outcomes. This finding further supports social capital theory, which posits that individuals gain social support and identity through community networks and interactive behaviours, thereby strengthening sense of belonging and well-being [94].

This study confirms the influence of urban park rights on citizens’ subjective perceptions, an effect realised through complex pathways within parks. Urban park rights shape residents’ sense of belonging and well-being primarily by enhancing their participatory motivation. Along this pathway, well-being emerges as the more readily attainable subjective outcome, whereas belongingness, though also affected, appears less sensitive. Well-being is more easily fostered through contact with green spaces and participation in park activities [95,96], while belongingness is more strongly associated with psychological attachment and place perception [97]. When citizens engage in co-governance by sharing decision-making and maintenance responsibilities, their sense of rights and efficacy is further amplified, thereby strengthening their emotional attachment to place and consolidating belonging [98].

The results of the qualitative research confirm that the main way for citizens to participate in shared governance is through volunteer activities. Volunteer organisations also play an important role in connecting groups, organising activities, and maintaining the basic park environment. As these activities are often coordinated by neighbourhood offices, this highlights the interlinked governance strategy between parks, communities, and surrounding administrative bodies [99]. This aligns with existing research showing that regular volunteer service exerts positive effects on subjective well-being, and that these effects increase over time with sustained participation [100]. This finding underscores that urban parks function as critical public spaces that integrate neighbourhood environments with residents’ daily lives, thereby strengthening social connectedness and enhancing both sense of belonging and overall well-being.

Furthermore, survey data show that 77.4% of respondents reside within a two-kilometre radius of the park. The results of the difference testing confirm that both WB and SoB decline as residential distance increases, with mean differences of nearly one point between those living within one kilometre and those more than five kilometres away. This finding is consistent with existing studies showing that proximity to parks is strongly related to park use and to residents’ physical, psychological, and social health [101,102]. These results support the notion that proximity, safety, and green space quality exert the greatest effects on residents’ sense of belonging [103]. As distance from the park increases, subjective perceptions show a general decline, consistent with prior evidence on the effects of proximity on social cohesion and mental health [104]. This confirms the “distance decay effect”: residents who live farther away use parks less frequently, thereby diminishing the park’s role in their daily lives and sense of psychological belonging.

The study contributes to theory by operationalising Lefebvre’s Right to the City within the context of urban parks and advancing a quantitative framework to assess governance mechanisms and subjective perceptions. The paper also validates the role of shared governance as a mediating variable in multiple mediation pathways. The paper also confirms the impact of volunteering as a co-governance measure on the subjective perception of citizens in the park field. At the practical level, on the one hand, cultural activities, volunteering, and community governance programmes should be used to strengthen residents’ intrinsic motivation, so that external perceptions can be gradually transformed into intrinsic values, and sustainable well-being can be promoted. On the other hand, policy makers and administrators should focus on creating a social and institutional environment that promotes participation, such as lowering the threshold of involvement, strengthening neighbourhood interactions, and public discussion mechanisms, in order to enhance residents’ sense of belonging. Links between communities, parks, and the city can also be strengthened by regularising volunteering. This will not only help realise the social functions of parks, but also promote a shared urban governance model.

Building on the in-depth and participatory investigation of this study, which focuses on Zhabei Park as a representative case of a high-density urban environment, future research could expand by examining parks of varying scales, classifications, and governance structures across different cultural contexts. Differences in governance of different types of parks (e.g., community parks, integrated parks, etc.) can be explored in future studies. In addition, longitudinal studies are needed to trace changes in well-being and sense of belonging over time. Future differences in the roles and psychological effects of different populations in shared governance mechanisms can be analysed in conjunction with new digital tools.

6. Conclusions

This study explored the role of urban parks in safeguarding the Right to the City by applying a theoretical framework to the context of urban parks, supported by robust quantitative and qualitative analytical methods. The positive correlation between the Right to Urban Park and citizens’ perceptions exists in the direct path of both individualisation and habitat. In others, co-governance motivation and community participation function as key mediators: motivation strongly enhances well-being, and participation consistently fosters belonging. Proximity to parks and sustained volunteering further improve subjective experiences, confirming both the distance decay effect and the civic value of participation and co-governance.

Theoretically, the study articulates the Right to the City as Right to the Park, proposing quantitative tools for analysing participation, governance pathways, and perceptions; in practice, it provides evidence for the promotion of collective action and inclusive governance, lowering the thresholds of participation, developing voluntary activities, and fostering community interaction to enhance a sense of belonging and well-being. This framework provides valuable guidance for the formulation of effective conjunctural operational, institutional, and constitutional arrangements and should be considered for incorporation into practice in order to promote equality through differentiation and inclusivity via co-creative territoriality. This approach supports a more just, resilient, and sustainable urban future where green infrastructure is scaled both vertically and horizontally within broader urban systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Y.L. and M.M.; materials and methods, Y.L. and J.W.; data collection, Y.F.; data analysis, Y.L. and Y.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; illustration, Y.L. and Z.G.; writing—review and editing, M.M., Z.G. and Y.F.; supervision, M.M. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Y.L., M.M. and Y.F. as co-authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and approved the final version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Programme for Cultivating Artistic Talents of China Scholarship Council, grant number 202306890022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted with the approval of the Greening and City Appearance Administration of Jing’an District, Shanghai, and with the support of the Zhabei Park Management Company and Shanghai Green Gold Greening Maintenance Engineering Co., Ltd.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Based on the agreements signed with the interviewees, the data will be made available upon request by the respective authors.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the students from Shanghai University, including WANG Guangxing and FU Guangxin, for their assistance with data collection. We sincerely thank the three anonymous reviewers and the editors of this paper for their valuable suggestions on the revision of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Research Scale.

Table A1.

Research Scale.

| Factors | Question | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right to Park | Individualization | Visiting the park has contributed to the diversity of my lifestyle | [31,32,105,106] |

| Visiting the park has enhanced my confidence in determining my social relationships | [31,94,95] | ||

| Visiting the park has enhanced my confidence and awareness in making free choices | [86,107,108,109] | ||

| The park gives me the freedom to choose the activities I want | [35,110,111] | ||

| Inhabit | Parks enhance the environment where I live | [112,113,114,115] | |

| Visiting the park makes me healthier physically and mentally | [38,116,117,118,119] | ||

| Parks enhance my quality of life | [38,120] | ||

| Habitat | The park provides me with the infrastructure and the necessary range I need | [57,121,122] | |

| I consider this park to be a part of my life | [123,124] | ||

| Regular visits to the park enable me to engage with other people and take part in the social life of specific groups of its community | [93,125,126] | ||

| Appropriation | I could easily reach and enter the park for free | [127,128,129] | |

| If I want, I can participate in the park’s design, management, and maintenance | [130,131] | ||

| In the park, I can choose and demarcate the public space where I want to carry out my activities and occupy it temporarily | [46,47] | ||

| I have a regular time and frequency to come to the park | [51,132,133] | ||

| Co-governance | Motivation | I trust the park to work with the public to manage park-related matters | [52,133,134] |

| I think my opinion is valued in the park’s governance process | [52,57,135] | ||

| I have channels to communicate with park managers or with local authorities | [52,57] | ||

| I also share responsibility for maintaining and improving the park | [52,130,136] | ||

| Behaviour | I offer help or support in park public affairs or organisation activities (e.g., volunteering/sharing information). | [60,137,138] | |

| I actively participate in meetings and discussions with other organisations or groups | [71,139] | ||

| I am willing to share information and resources during joint decision-making processes | [52,140,141] | ||

| I am willing to adjust my actions and plans to support shared goals in collaboration | [136,142] | ||

| Subjective Perception | Well-being | The park gives my life purpose and meaning | [75,76] |

| I am engaged in and interested in my daily life by using the urban park | |||

| I actively contribute to the happiness and well-being of others in an urban park | |||

| Sense of Belonging | I feel accepted by others | [74] | |

| I feel welcome | |||

| I feel like I fit in | |||

| I feel at home in the park |

Appendix B

Survey Questionnaire: Investigation into Participation and Perceptions of Urban Parks

Dear Respondent,

Hello! We are a park research team from Shanghai University and the University of Auckland, surveying participation and experiences in urban parks. Your views are invaluable in helping us understand the current state of urban parks.

All personal information will be treated anonymously and used solely for academic research purposes, without compromising your privacy. If you agree to complete the survey, please proceed after signing the informed consent form.

Please tick the corresponding circle that best reflects your information and feelings.

Personal Basic Information

Age: ○15–30 years old ○31–45 years old ○46–60 years old ○61–75 years old ○76 years old and above

Gender: ○ Male ○ Female

Work: ○Student ○Worker ○Service industry ○Civil servant ○White collar ○Private owner ○Freelance ○Retirees ○Others

Education: ○None ○ Primary school ○ Junior high school ○ Senior high school ○ Undergraduate and three-year college ○ Master’s degree and above ○ Specialist

Income: ○No stable income ○ Low income (1000–5000) ○ Middle income (5000–10,000) ○ High income 10,000

Length of residence in Shanghai: ○ 0–12 months ○ 1–2 years ○ 2–5 years ○ 5–10 years ○ 10+ years

Distance from residence to park: ○Within one kilometre ○Within two kilometres ○2~5 kilometres ○More than 5 kilometres

With the following statements:

1 Strongly disagree 2 Disagree 3 Somewhat disagree 4 Neutral

5 Somewhat agree 6 Agree 7 Strongly agree

| About the Park | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Visiting the park has contributed to the diversity of my lifestyle | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Visiting the park has enhanced my confidence in determining my social relationships | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Visiting the park has enhanced my confidence and awareness in making free choices | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The park gives me the freedom to choose the activities I want. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Parks enhance the environment where I live | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Visiting the park makes me healthier physically and mentally | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Parks enhance my quality of life | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The park provides me with the infrastructure and the necessary range I need | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I consider this park to be a part of my life | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Regular visits to the park enable me to engage with other people and take part in the social life of specific groups of its community | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I could easily reach and enter the park for free | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| If I want, I can participate in the park’s design, management, and maintenance | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| In the park, I can choose and demarcate the public space where I want to carry out my activities and occupy it temporarily | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I have a regular time and frequency to come to the park | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Regarding Participation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I trust the park to work with the public to manage park-related matters | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I think my opinion is valued in the park’s governance process | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I have channels to communicate with park managers or with local authorities | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I also share responsibility for maintaining and improving the park | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I offer help or support in park public affairs or organisation activities (e.g., volunteering/sharing information) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I actively participate in meetings and discussions with other organisations or groups | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I am willing to share information and resources during joint decision-making processes | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I am willing to adjust my actions and plans to support shared goals in collaboration | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Well-being | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| The park gives my life purpose and meaning | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I am engaged in and interested in my daily life by using the urban park | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I actively contribute to the happiness and well-being of others in an urban park | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Sense of Belonging | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I feel accepted by others | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I feel welcome | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I feel like I fit in | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I feel at home in the park | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Other suggestions and thoughts: Date: | |||||||

References

- Nancy, J.-L. The Inoperative Community; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1991; Volume 76. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, W.P.; Locke, D.H.; Niu, K.; Frumkin, H. Parks and Social Capital: An Analysis of the 100 Most Populous U.S. Cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 112, 128956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz, N.F.; Rode, P.; McQuarrie, M. New Urban Governance: A Review of Current Themes and Future Priorities. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinenberg, E. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life; Crown: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-1-57230-847-3. [Google Scholar]

- Layton, J.; Latham, A. Social Infrastructure and Public Life—Notes on Finsbury Park, London. Urban Geogr. 2022, 43, 755–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, E.-H.; Roberts, J.E.; Eum, Y.; Li, X.; Konty, K. Exposure to Urban Green Space May Both Promote and Harm Mental Health in Socially Vulnerable Neighborhoods: A Neighborhood-Scale Analysis in New York City. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 112292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.M. Why Public Space Matters; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. Writings on Cities; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 1996; Volume 63, pp. 173–174. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda; United Nations: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017; ISBN 978-92-1-132731-1. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development. Habitat III Policy Papers: Policy Paper 1 The Right to the City and Cities for All; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Imboden, M.T. Belonging: An Essential Human and Organizational Need. Am. J. Health Promot. 2024, 38, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirksmeier, P. A Sense of Belonging to the Neighbourhood in Places beyond the Metropolis—The Role of Social Infrastructure. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Advances and Open Questions in the Science of Subjective Well-Being. Collabra Psychol. 2018, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, S.S. The Just City. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2014, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino, J.E.; Martinez, L.; Valencia, I.; Duque, J.C. Happiness, Life Satisfaction, and the Greenness of Urban Surroundings. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2023, 237, 104811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.L.; Mowen, A.J.; Drogin Rodgers, E.B. Belonging and Welcomeness in State and Community Parks: Visitation Impacts and Strategies for Advancing Environmental Justice. Geoforum 2024, 157, 104149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Ma, J.; Dong, G. How Mobility-Based Exposure to Green Space and Environmental Pollution Influence Individuals’ Wellbeing? A Structural Equation Analysis through the Lens of Environmental Justice. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2024, 252, 105199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Kim, H.J.; With, K.A. Urban Green Space Alone Is Not Enough: A Landscape Analysis Linking the Spatial Distribution of Urban Green Space to Mental Health in the City of Chicago. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2022, 218, 104309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Kee, F.; Hunter, R.F. Exploring Mechanistic Pathways Linking Urban Green and Blue Space to Mental Wellbeing before and after Urban Regeneration of a Greenway: Evidence from the Connswater Community Greenway, Belfast, UK. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2023, 235, 104739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, A.; Layton, J. Social Infrastructure and the Public Life of Cities: Studying Urban Sociality and Public Spaces. Geogr. Compass 2019, 13, e12444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Luo, W.; Yu, W.; Lin, R.; Bi, W. Public Participation in Urban Park Co-Construction: A Case Study on Exploring Sustainable Design Paths for County Cities in Kaiyuan County, Yunnan Province. Buildings 2025, 15, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, E.; Bukovszki, V.; van Lierop, M.; Tomasi, S.; Pauleit, S. Towards More Equitable Urban Greening: A Framework for Monitoring and Evaluating Co-Governance. Urban Plan. 2024, 9, 8184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Tan, H. The Construction of Collaborative Governance Mechanisms for Green Space in Megacities: Evidence from China. SAGE Open 2025, 15, 21582440251328921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, D. A Ladder of Urban Resilience: An Evolutionary Framework for Transformative Governance of Communities Facing Chronic Crises. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The Right to the City. In Citizenship Rights; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 465–482. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Right to the City. New Left Rev. 2008, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, M. Recapturing Democracy: Neoliberalization and the Struggle for Alternative Urban Futures; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A. The Good City. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, M.; Lo, M. Urban Safety via Digitally Augmented Relationality: Leveraging Gotong-Royong for Collaboration, Empathy, and Re-Enchantment in Indonesia’s Public Space. J. Public Space 2025, 10, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aalst, I.; Brands, J. Young People: Being Apart, Together in an Urban Park. J. Urban 2021, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germann-Chiari, C.; Seeland, K. Are Urban Green Spaces Optimally Distributed to Act as Places for Social Integration? Results of a Geographical Information System (GIS) Approach for Urban Forestry Research. For. Policy Econ. 2004, 6, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Lin, G. The Relationship between Urban Green Space and Social Health of Individuals: A Scoping Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 85, 127969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K. Being Together in Urban Parks: Connecting Public Space, Leisure, and Diversity. Leis. Sci. 2010, 32, 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H. Managing Urban Parks for a Racially and Ethnically Diverse Clientele. Leis. Sci. 2002, 24, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The History of Plaza in San José, Costa Rica. The Political Symbolism of Public Space. In On the Plaza; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2000; pp. 47–83. ISBN 978-0-292-74826-2. [Google Scholar]

- Vilarrodona, J.U. Dret a Habitar, Dret a Habitatge (Social). Barc. Soc. Profunditat 2016, 78–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rozzi, R. Biocultural Ethics: Recovering the Vital Links between the Inhabitants, Their Habits, and Habitats. Environ. Ethics 2012, 34, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.; Schwartz, R. The Roles of an Urban Parks System. World Urban Parks 2016, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Winter, M. Conceptualising Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Novel Framework for Research and Critical Engagement. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukur, F.; Othman, N.; Nawawi, A.H. The Values of Parks to the House Residents. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 49, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walker, J.R.; Crompton, J.L. The Relationship of Household Proximity to Park Use. J. Park. Recreat. Adm. 2012, 30, 52–63. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hunter, R.F.; Adlakha, D.; Cardwell, C.; Cupples, M.E.; Donnelly, M.; Ellis, G.; Gough, A.; Hutchinson, G.; Kearney, T.; Longo, A.; et al. Investigating the Physical Activity, Health, Wellbeing, Social and Environmental Effects of a New Urban Greenway: A Natural Experiment (the PARC Study). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, D.; Hou, Y.; Du, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Shi, L. Outdoor Thermal Comfort of Urban Park-A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Martínez, D.; Dadvand, P.; Forns, J.; Plasència, A.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Mental Health Benefits of Long-Term Exposure to Residential Green and Blue Spaces: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 4354–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, M. Excavating Lefebvre: The Right to the City and Its Urban Politics of the Inhabitant. GeoJournal 2002, 58, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, H.; Sadri, S.Z. THE RIGHT TO APPROPRIATION: SPATIAL RIGHTS AND THE USE OF SPACE. In Proceedings of the Architecture as a Tool for the Re-Appropriation of the Contemporary City, Tirana, Albania, 1 October 2012; Polis University: Tirana, Albania, 2012; pp. 92–93, ISBN 978-9928-4053-9-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gonin, A. Inhabiting Together: Manure Contracts and Other Territorial Compositions Between Pastoralism and Agriculture in Western Burkina Faso. In Territories, Environments, Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 70–88. ISBN 978-1-03-205166-6. [Google Scholar]

- Manfredini, M. Affirmatively Reading Deterritorialisation in Urban Space: An Aotearoa/New Zealand Perspective. In Territories, Environments, Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Mubi, B.A.; Kärrholm, M. Territoriology and the Study of Public Place. In The Routledge Handbook of Urban Design Research Methods; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 261–268. ISBN 978-0-367-76805-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, R. Building Social Cohesion Through Urban Design: The Efficacy of Public Space Design to Promote Place Attachment and Social Connections Among Culturally Diverse Users Within Urban Parks. PhD Thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satorras, M.; Ruiz-Mallen, I.; Monterde, A.; March, H. Co-Production of Urban Climate Planning: Insights from the Barcelona Climate Plan. Cities 2020, 106, 102887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiago, P.; Gouveia, M.J.; Capinha, C.; Santos-Reis, M.; Pereira, H.M. The Influence of Motivational Factors on the Frequency of Participation in Citizen Science Activities. Nat. Conserv. 2017, 18, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, G.P.; Winters, D.C.; Locke, E.A. Cognitive and Motivational Effects of Participation: A Mediator Study. J. Organ. Behav. 1994, 15, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.L.; Webster, N.; Agans, J.P.; Graefe, A.R.; Mowen, A.J. Engagement, Representation, and Safety: Factors Promoting Belonging and Positive Interracial Contact in Urban Parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, G.R.; Rock, M.; Toohey, A.M.; Hignell, D. Characteristics of Urban Parks Associated with Park Use and Physical Activity: A Review of Qualitative Research. Health Place 2010, 16, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafshan, M.; Tabrizi, A.M.; Bauer, N.; Kienast, F. Place Attachment through Interaction with Urban Parks: A Cross-Cultural Study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.-A.; Arslan, G.; Craig, H.; Arefi, S.; Yaghoobzadeh, A.; Sharif Nia, H. The Psychometric Evaluation of the Sense of Belonging Instrument (SOBI) with Iranian Older Adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, Z.; Yazdkhasti, M.; Rostami, M.; Ghavidel, N. Factors Affecting Mental Health and Happiness in the Elderly: A Structural Equation Model by Gender Differences. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, B.M.; Patusky, K. Developing a Measure of Sense of Belonging. Nurs. Res. 1995, 44, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, L.A.J.; Thomas, C.L. High-Impact Teaching Practices Foster a Greater Sense of Belonging in the College Classroom. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2022, 46, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, E.; Arundell, L.; Parker, K.; Veitch, J.; Salmon, J.; Ridgers, N.D.; Timperio, A.; Sahlqvist, S.L.; Loh, V.H.Y. Influence of Park Visitation on Physical Activity, Well-Being and Social Connectedness among Australians during COVID-19. Health Promot. Int. 2024, 39, daae137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haim-Litevsky, D.; Komemi, R.; Lipskaya-Velikovsky, L. Sense of Belonging, Meaningful Daily Life Participation, and Well-Being: Integrated Investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahnow, R.; Corcoran, J. The Importance of Public Familiarity for Sense of Belonging in Brisbane Neighborhoods. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trawalter, S.; Hoffman, K.; Palmer, L. Out of Place: Socioeconomic Status, Use of Public Space, and Belonging in Higher Education. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 120, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipitone, J.M.; Jović, S. Urban Green Equity and COVID-19: Effects on Park Use and Sense of Belonging in New York City. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.; Simpson, T.; Scheld, S. Toolkit for the Ethnographic Study of Space (TESS). In Public Space Research Group Center for Human Environments; The Graduate Center, City University of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, W.L.; Taff, B.D.; Miller, Z.D.; Newman, P.; Zipp, K.Y.; Pan, B.; Newton, J.N.; D’Antonio, A. Connecting Motivations to Outcomes: A Study of Park Visitors’ Outcome Attainment. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 29, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmer, M.L. Citizen Participation in Neighborhood Organizations and Its Relationship to Volunteers’ Self-and Collective Efficacy and Sense of Community. Soc. Work Res. 2007, 31, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the Social Innovation Journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Duru, E. Initial Development and Validation of the School Belongingness Scale. Child Ind. Res. 2017, 10, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellinger, C.; Fritzson, A.; Park, B.; Dimidjian, S. Developing the Sense of Belonging Scale and Understanding Its Relationship to Loneliness, Need to Belong, and General Well-Being Outcomes. J. Personal. Assess. 2024, 106, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New Well-Being Measures: Short Scales to Assess Flourishing and Positive and Negative Feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Duan, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, T. Psychometric Evaluation of the Simplified Chinese Version of Flourishing Scale. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2016, 26, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. What Is the Best Response Scale for Survey and Questionnaire Design; Review of Different Lengths of Rating Scale/Attitude Scale/Likert Scale. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 2019, 8, 1–10, ISBN 2296-1747. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, H. What Is Farmers’ Level of Satisfaction under China’s Policy of Collective-Owned Commercial Construction Land Marketisation? Land 2022, 11, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Factor Analysis as a Tool for Survey Analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. The Dependability of Behavioral Measurements: Theory of Generalizability for Scores and Profiles; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 978-0-471-18850-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ab Hamid, M.R.; Sami, W.; Sidek, M.M. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker Criterion versus HTMT Criterion. Proc. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. JAMS 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]