The Role of Climate Services in Supporting Climate Change Adaptation in Ethiopia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- provide an overview of historical and projected climate trends in Ethiopia to contextualize risks;

- (ii)

- examine the policy frameworks guiding climate adaptation and how they integrate climate information;

- (iii)

- capture the perspectives of both users and providers of climate services through structured surveys; and

- (iv)

- provide recommendations to strengthen the relevance, accessibility, and impact of climate services for national and subnational adaptation planning.

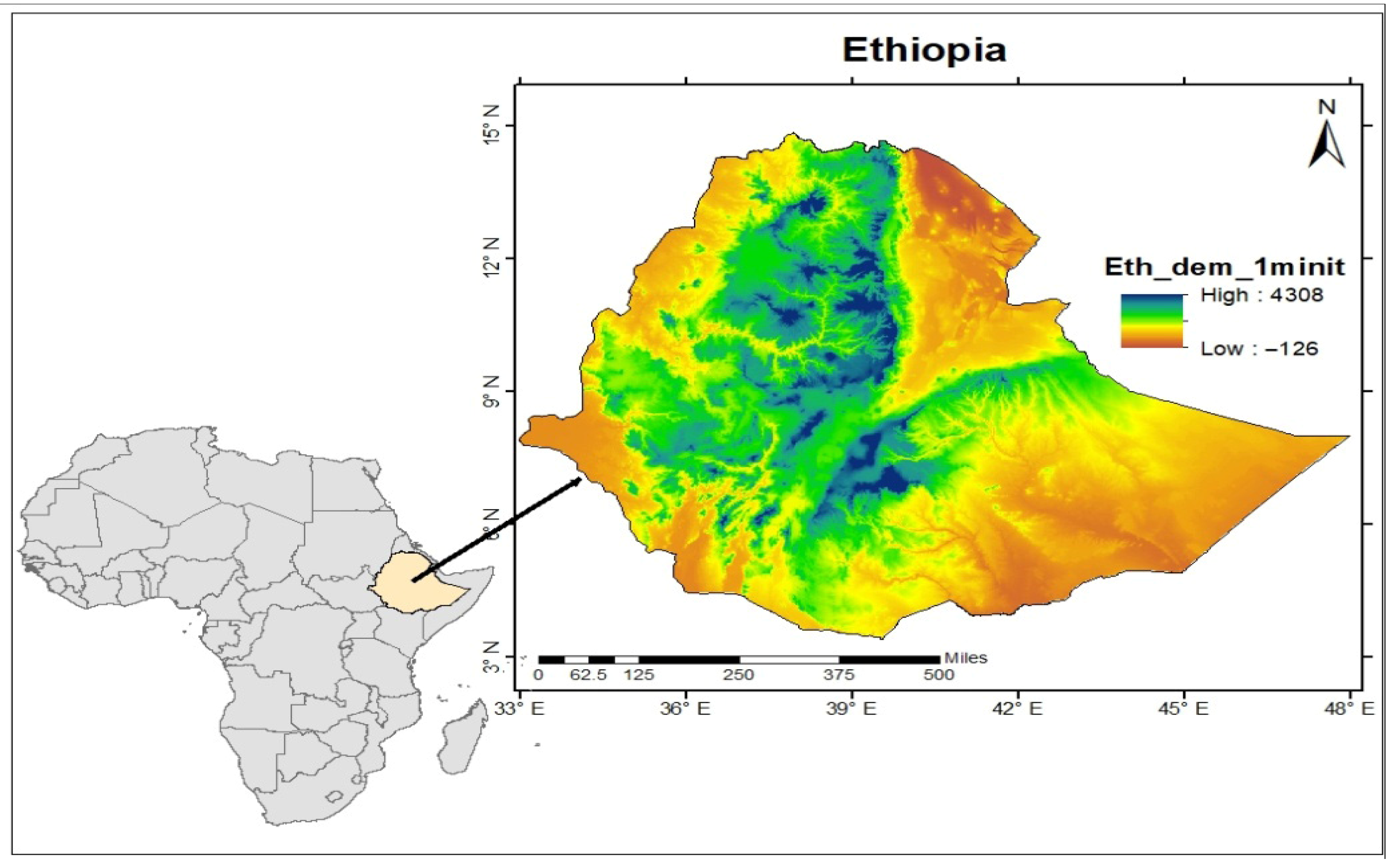

2. Description of the Study Area

2.1. Location and Topography

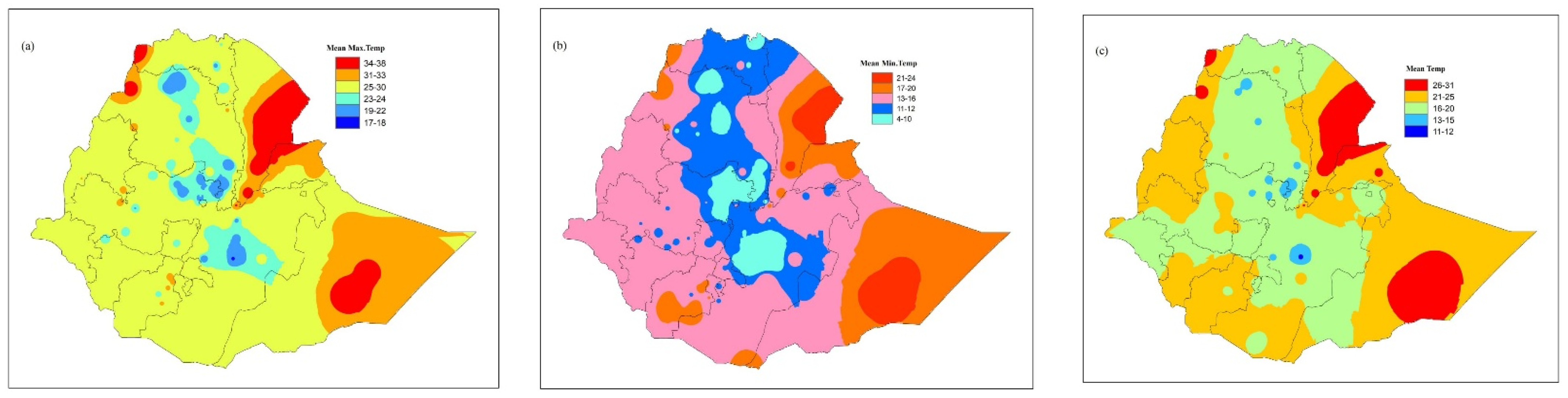

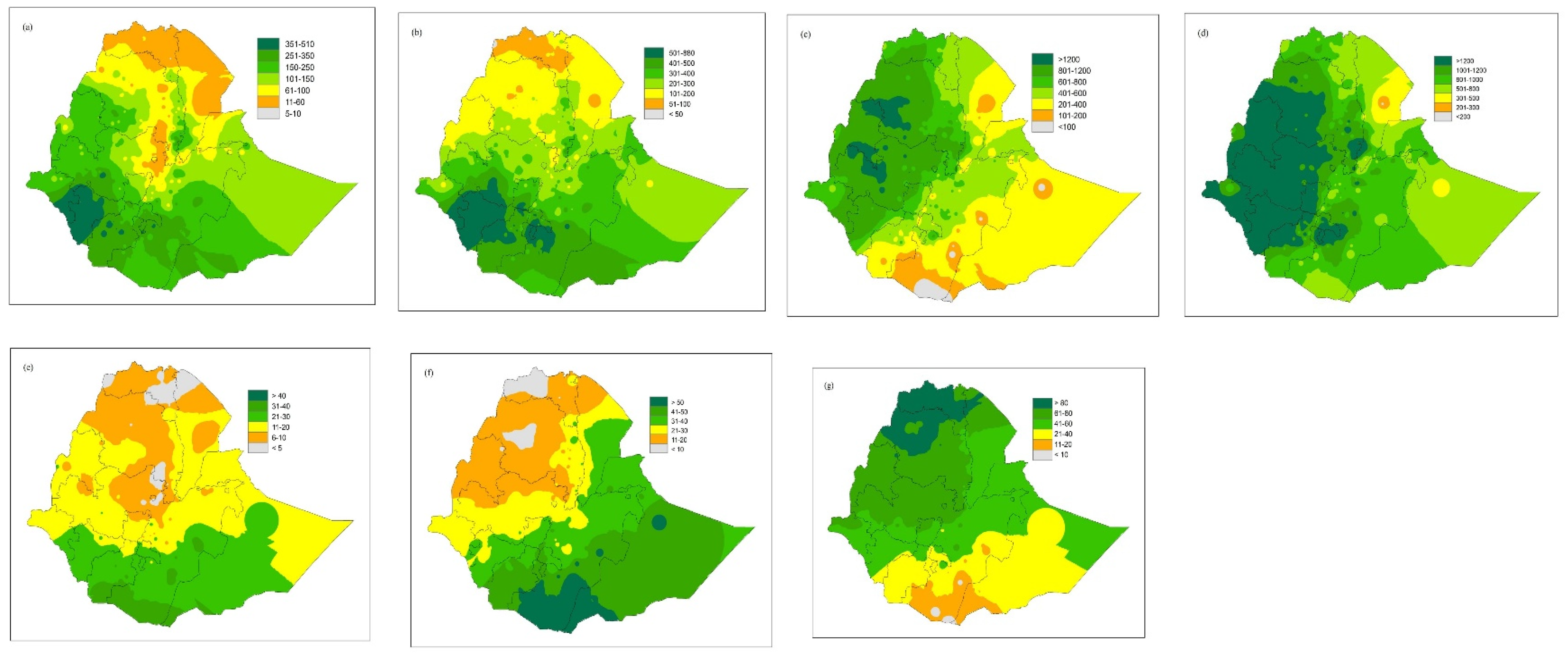

2.2. Climate Profile of Ethiopia

3. Data Sources and Methodology

3.1. Data Sources

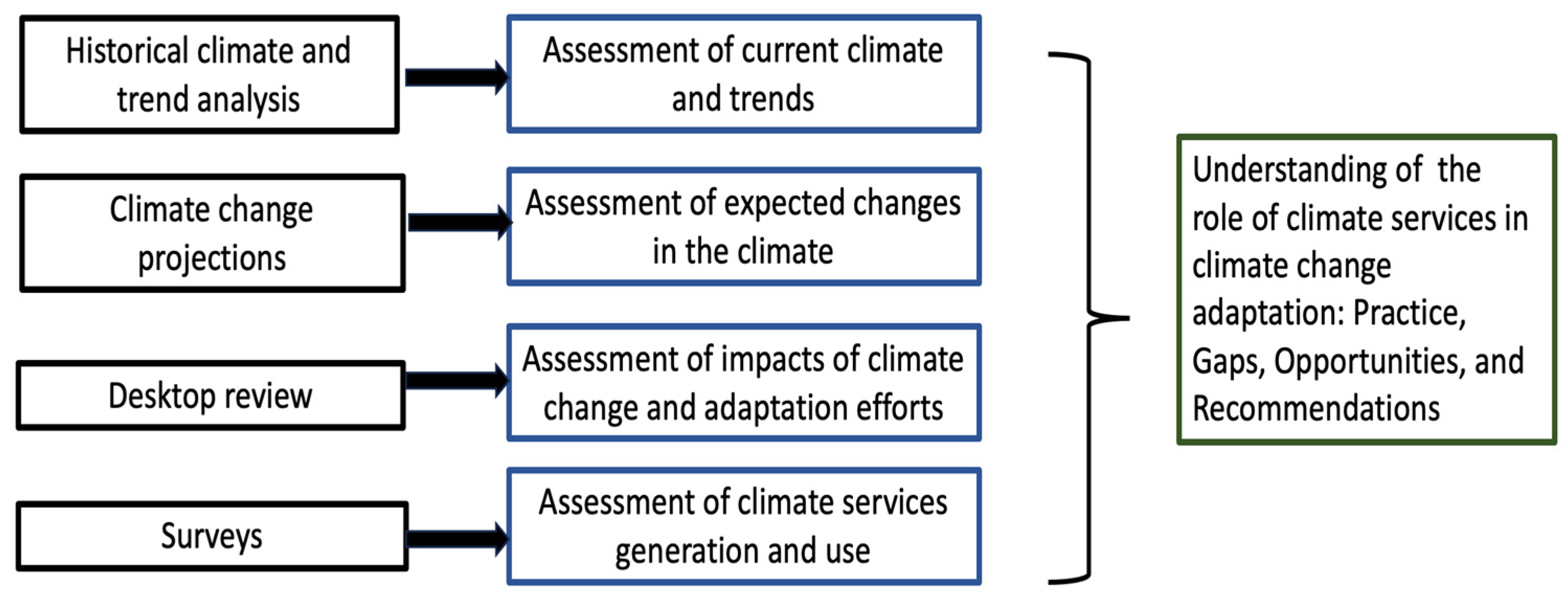

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. General Overview

- (i)

- users of climate information, including policymakers and practitioners from various sectors and administrative levels; and

- (ii)

- technical staff from the Ethiopian Meteorological Institute (EMI), based at both headquarters and regional centers.

3.2.2. Climate Change Projection

3.2.3. Desktop Review

3.2.4. Conducting Surveys

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Observed Climate Variability, Trends, and Change in Ethiopia

4.1.1. Observed Rainfall and Temperature Variability, and Historical Trends

4.1.2. Future Rainfall Projections in Ethiopia

4.1.3. Future Temperature Projections in Ethiopia

4.2. Climate Change in Ethiopia: Impacts and Adaptation Efforts

4.2.1. Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture

4.2.2. Climate Change Impacts on Water Resources

4.2.3. Climate Change Impacts on Human Health

4.3. Ethiopia’s Adaptation Efforts: National Strategies, Polices, and Plans

5. The Role of Climate Services in Climate Change Adaptation in Ethiopia

5.1. Climate Services in Ethiopia

5.2. Analysis of Survey Results on Climate Services in Ethiopia

- The importance of EMI’s climate data, information, and services to the users and their institutions.

- The level of satisfaction users have with the accessibility, quality, accuracy, and timeliness of EMI’s products and services.

- Staff understanding of EMI’s mission and the concept of climate services.

- Staff perceptions of how well EMI is delivering on its mission and fulfilling its mandate.

- Levels of self-assessed performance among staff and their satisfaction with the overall performance of the institution.

5.2.1. Presentation of Survey Results for Users

- Importance of EMI services and what information products are most important

- ii.

- Satisfaction with EMI products and services

5.2.2. Presentation of Survey Results for EMI Staff

- Understanding of weather climate services provided by EMI

- ii.

- Satisfaction with the performance of the Institution and that of their own

- iii.

- Satisfaction with their work at the institution

5.3. Use of Climate Services for Climate Change Adaptation in Ethiopia: Challenges and Opportunities

5.4. Challenges

5.5. Analysis of Survey Results on the Use of Climate Information for Climate Change Adaptation

6. Conclusions

- Investing in technical capacity and modern infrastructure, including automatic weather stations, high-performance computing, and improved data dissemination systems.

- Promoting co-production of climate information by fostering closer collaboration between providers and users to ensure climate services are demand-driven and actionable.

- Enhancing integration of climate services into national and subnational planning, ensuring that climate information informs policies and plans across sectors.

- Strengthening institutional coordination to reduce duplication of efforts and enhance the collective impact of climate services on adaptation outcomes.

- Improving outreach and accessibility, particularly for rural and vulnerable communities, through tailored communication strategies and partnerships with extension services and communities.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Vaughan, C.; Kagabo, D.; Dinku, T.; Carr, E.; Körner, J.; Zougmoré, R. Climate services can support African farmers’ context-specific adaptation needs at scale. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WASP. Science for Adaptation Policy Brief: Early Warning Systems for Adaptation; WASP: Nauvoo, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, E.B.; Hochard, J.P. The impacts of climate change on the poor in disadvantaged regions. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2018, 12, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, F.; Mustafa, S.; Ariztegui, D.; Chirindja, F.J.; Di Capua, A.; Hussey, S.; Loizeau, J.-L.; Maselli, V.; Matanó, A.; Olabode, O.; et al. Prolonged drought periods over the last four decades increase flood intensity in southern Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handmer, J.; Honda, Y.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Arnell, N.; Benito, G.; Hatfield, J.; Mohamed, I.F.; Peduzzi, P.; Wu, S.; Sherstyukov, B.; et al. Changes in impacts of climate extremes: Human systems and ecosystems. In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, C.; Steynor, A.; Manyuchi, A. Climate services in Africa: Re-imagining an inclusive, robust and sustainable service. Clim. Serv. 2019, 15, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, T.; Mengistu, A. Impacts of Climate Change on Food Security in Ethiopia: Adaptation and Mitigation Options: A Review. In Climate Change-Resilient Agriculture and Agroforestry; Castro, P., Azul, A., Leal Filho, W., Azeiteiro, U., Eds.; Climate Change Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewket, W.; Radeny, M.; Mungai, C. Agricultural Adaptation and Institutional Responses to Climate Change Vulnerability in Ethiopia. CCAFS Working Paper No. 106; CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/56997 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Chanie, K. Hydro-meteorological response to climate change impact in Ethiopia: A review. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 1922–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geleta, T.D.; Dadi, D.K.; Garedew, W.; Worku, A.; Debesa, G. Analyzing Urban Centers’ Vulnerability to Climate Change Using Livelihood Vulnerability Index and IPCC Framework Model in Southwest Ethiopia. J. Agric. Food Nat. Resour. 2024, 2, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgatroyd, A.; Thomas, T.; Koo, J.; Strzepek, K.; Hall, J. Building Ethiopia’s food security resilience to climate and hydrological change. Environ. Res. Food Syst. 2024, 2, 015008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, A.; Hansen, J.; Radeny, M.; Belay, S.; Solomon, D. Actor roles and networks in agricultural climate services in Ethiopia: A social network analysis. Clim. Dev. 2019, 12, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Drought in Numbers, Land and Drought; UNCCD COP13 Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FDRE. Ethiopia’s Climate-Resilient Green Economy (CRGE) Strategy; Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011.

- Paul, C.J.; Weinthal, E. The development of Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy 2011–2014: Implications for rural adaptation. Clim. Dev. 2019, 11, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeray, N.; Demie, A. Climate change impact, vulnerability and adaptation strategy in Ethiopia: A review. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2016, 5, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- FDRE. Ethiopia’s National Adaptation Plan (NAP); UNFCCC Submission: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, C.; Mason, S.; Walland, D. The Global Framework for Climate Services. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 831–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, C.; Dessai, S. Climate services for society: Origins, institutional arrangements, and design elements for an evaluation framework. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2014, 5, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, F.; Daniela, J.; Helmholtz-Z Haile, A. Handbook of Climate Services; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Climate Knowledge for Action: A Global Framework for Climate Services—Empowering the Most Vulnerable; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, E.; Wright, S.J.; Biesbroek, R.; Goosen, H.; Ludwig, F. Successful climate services for adaptation: What we know, don’t know and need to know. Clim. Serv. 2022, 27, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, C.; Stone, R.; Tait, A. Improving the use of climate information in decision-making. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 614–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyoni, R.S.; Bruelle, G.; Chikowo, R.; Andrieu, N. Targeting smallholder farmers for climate information services adoption in Africa: A systematic literature review. Clim. Serv. 2024, 34, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, S.; Fielke, S.; Fleming, A.; Jakku, E.; Malakar, Y.; Turner, C.; Hunter, T.; Tijs, S.; Bonnett, G. Climate services for agriculture: Steering towards inclusive innovation in Australian climate services design and delivery. Agric. Syst. 2024, 217, 103938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, D.; Schipper, E.L. Adaptation to climate change in Africa: Challenges and opportunities identified from Ethiopia. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, G.W.; Ichoku, H.E.; Phil-Eze, P.O. Determinants of smallholder farmers’ adoption of adaptation strategies to climate change in Eastern Tigray National Regional State of Ethiopia. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tola, F.T.; Dadi, D.K.; Kenea, T.T.; Dinku, T. Weather and climate services in Ethiopia: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Front. Clim. 2025, 7, 1551188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinku, T.; Faniriantsoa, R.; Cousin, R.; Khomyakov, I.; Vadillo, A.; Hansen, J.W.; Grossi, A. ENACTS: Advancing climate services across Africa. Front. Clim. 2022, 3, 787683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsengiyumva, G.; Dinku, T.; Cousin, R.; Khomyakov, I.; Vadillo, A.; Faniriantsoa, R.; Grossi, A. Transforming access to and use of climate information products derived from remote sensing and in situ observations. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; UNDP. Using Climate Services in Adaptation Planning for the Agriculture Sectors; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, E.; Meijering, J.V.; Biesbroek, R.; Ludwig, F. Defining successful climate services for adaptation with experts. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 152, 103641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geremew, A.; Nijhawan, A.; Mengistie, B.; Mekbib, D.; Flint, A.; Howard, G. Climate resilience of small-town water utilities in eastern Ethiopia. PLoS Water 2024, 3, e0000158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfahunegn, G.B.; Mekonen, K.; Tekle, A. Farmers’ perception on causes, indicators, and determinants of climate change in northern Ethiopia: Implications for developing adaptation strategies. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, M.T.; Dyer, E. Hydrologic extremes in a changing climate: A review of extremes in East Africa. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2024, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, A.; Dinku, T. From research to practice: Adapting agriculture to climate today for tomorrow in Ethiopia. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 931514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanuel, W.; Molla, M. Institutional capacity and strategy to enhance social-ecological adaptation for climate change, South Ethiopia. Ann. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2020, 4, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOPD. Third National Communication (NC3) of the Federal Republic of Ethiopia; MOPD: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, G. Aspects of Climate and Water Budget in Ethiopia; Addis Ababa University Press: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Dinku, T.; Hailemariam, K.; Maidement, R.; Tarnavsky, E.; Connor, S.J. Combined use of satellite estimates and rain gauge observations to generate high-quality historical rainfall time series over Ethiopia. Int. J. Clim. 2013, 34, 2489–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettie, F.M.; Gayler, S.; Weber, T.K.D.; Tesfaye, K.; Streck, T. High-resolution CMIP6 climate projections for Ethiopia using the gridded statistical downscaling method. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getachew, M.M.; Parakash, U.R.; Milica, S.T.; Rogert, S. The phenomenon of drought in Ethiopia: Historical evolution and climatic forcing. Hydrol. Res. 2024, 55, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNOCHA. Ethiopia: Humanitarian Impact of Drought Flash Update #1, 22 December 2023; OCHA: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zinna, A.W.; Suryabhagavan, K.V. Remote sensing and GIS-based spectro-agrometeorological maize yield forecast model for South Tigray Zone, Ethiopia. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2016, 08, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melesew, Z.; Anteneh, D. Socioeconomic Impacts of the 2006 Seasonal Flooding along Flood Prone Areas: The Case of Dire Dawa Administration, Ethiopia. Int. J. Sci. Basic Appl. Res. IJSBAR 2016, 28, 90–106. [Google Scholar]

- Camberlin, P. Rainfall anomalies in the source region of the Nile and their connection with the Indian summer monsoon. J. Clim. 1997, 10, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korecha, D.; Barnston, A.G. Predictability of June–September Rainfall in Ethiopia. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2007, 135, 628–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersha, A.A.; van Laerhoven, F. The interplay between planned and autonomous adaptation in response to climate change: Insights from rural Ethiopia. World Dev. 2018, 107, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashaw, T.; Wubaye, B.; Worqlul, A.W.; Dile, Y.T.; Mohammed, J.A.; Birhan, D.A.; Tefera, G.W.; van Oel, P.R.; Haileslassie, A.; Chukalla, A.D.; et al. Local and regional climate trends and variabilities in Ethiopia: Implications for climate change adaptations. Environ. Chall. 2023, 13, 100794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temesgen, E.; Akil, D.; Wendemeneh, D. The impact of climate change on the availability of irrigation water at the rift valley lakes basin in southern Ethiopia: A review. J. Digit. Food Energy Water Syst. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Initial National Communication of Ethiopia to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); National Meteorological Services Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- UNFCCC. Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy National Adaptation Plan; Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019.

- Teshome, A.; Zhang, J. Increase of Extreme Drought over Ethiopia under Climate Warming. Adv. Meteorol. 2019, 5235429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofu, D.A. Evaluating the impacts of climate-induced East Africa’s recent disastrous drought on the pastoral livelihoods. Sci. Afr. 2024, 24, e02219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekuyie, M.; Mulu, D. Perception of impacts of climate variability on pastoralists and their adaptation/coping strategies in Fentale district of Oromia region, Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2021, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogale, G.A.; Erena, Z.B. Drought vulnerability and impacts of climate change on livestock production and productivity in different agro-ecological zones of Ethiopia. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2022, 50, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebre, G.; Amekawa, Y.; Ashebir, A. Can farmers’ climate change adaptation strategies ensure their food security? Evidence from Ethiopia. Agrekon 2023, 62, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezu, A. Analyzing Impacts of Climate Variability and Changes in Ethiopia: A Review. Am. J. Mod. Energy 2020, 6, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofu, D.A.; Fana, C.; Dilbato, T.; Dirbaba, N.B.; Tesso, G. Pastoralists’ and agro-pastoralists’ livelihood resilience to climate change-induced Risks in the Borana zone, south Ethiopia: Using resilience index measurement approach. Pastor. Res. Policy Pract. 2023, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRC. Climate Change Impacts on Health: Ethiopia Assessment; IFRC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McCartney, M.; Girma, M. Evaluating the downstream implications of planned water resource development in the Ethiopian portion of the Blue Nile River. Water Int. 2012, 37, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimere, A.; Assefa, E. Assessment of the water-energy nexus under future climate change in the Nile River Basin. Climate 2021, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adane, Z.; Yohannes, T.; Swedenborg, E. Balancing water demands and increasing climate resilience: Establishing a baseline water risk assessment model in Ethiopia. World Resour. Inst. Publ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deresse, T. The vulnerability of communities to climate change-induced water scarcity in Ethiopia and Kenya: A systematic review. Glob. J. Biol. Agric. Health Sci. 2023, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopal, A.; Medhin, H.; Bærøe, K.; Norheim, O. Climate change and health in Ethiopia: To what extent have the health dimensions of climate change been integrated into the climate-resilient green economy? World Med. Health Policy 2021, 13, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, B.; Nigussie, J.; Molla, A.; Mareg, M. Occupational stress and associated factors among health care professionals in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salilih, S.; Abajobir, A. Work-related stress and associated factors among nurses working in public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Workplace Health Saf. 2014, 62, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melaku, A.; Mulugeta, A. Climate compatible development in Ethiopia: A policy review on water resources and disaster risk management of Ethiopia. Int. J. Water Resour. Environ. Eng. 2021, 13, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, Z. The climate change-agriculture nexus in drylands of Ethiopia. In Vegetation Dynamics, Changing Ecosystems and Human Responsibility; IntecOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EDRMC. Multi-Hazard, Impact-Based Early Warning and Early Action Roadmap (2023–2030); EDRMC: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- FDRE. Stock Take of Climate Change Adaptation Interventions in Ethiopia; Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2025.

- Murungu, R.; Bankole-Bolawole, O.; Otieno, C.; Mwangi, C.; Aboma, G. Inclusion of water, sanitation and hygiene in Ethiopia’s nationally determined contributions 2020 update process—A policy brief. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2022, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, L.; González Romero, C.; Muñoz, A.G.; Acharya, N.; Ahmed, S.; Baethgen, W.; Blumenthal, B.; Braun, M.; Campos, D.; Chourio, X.; et al. Climate Services Ecosystems in times of COVID-19. In WMO at 70—Responding to a Global Pandemic; WMO Bulletin: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 69, pp. 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ozor, N.; Acheampong, E.; Nyambane, A. Climate information needs and services for climate change mitigation and adaptation in Cameroon, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, and Tunisia. Agro-Science 2021, 20, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnet, A.; Boqué-Ciurana, A.; Pozo, J.X.O.; Russo, A.; Coscarelli, R.; Antronico, L.; De Pascale, F.; Saladié, Ò.; Anton-Clavé, S.; Aguilar, E. Climate services for tourism: An applied methodology for user engagement and co-creation in European destinations. Clim. Serv. 2021, 23, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, D.; Clarkson, G.; Dorward, P.; Obando, D. First experiences with participatory climate services for farmers in Central America: A case study in Honduras. Adv. Agric. Dev. 2024, 5, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhari, M.; Dressel, M.; Schuck-Zöller, S. Challenges and best practices of co-creation: A qualitative interview study in the field of climate services. Clim. Serv. 2022, 25, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedeld, T.; Mathur, M.; Bharti, N. How can co-creation improve the engagement of farmers in weather and climate services (WCS) in India. Clim. Serv. 2019, 15, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steynor, A.; Pasquini, L. Using a climate change risk perceptions framing to identify gaps in climate services. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 782012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NMA. National Framework for Climate Services—Ethiopia: Strategic Plan: 2021–2030; NMA: Staffordshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.; Menza, M.; Hagos, F.; Haileslassie, A. Impact of climate-smart agriculture on households’ resilience and vulnerability: An example from the central rift valley, Ethiopia. Clim. Resil. Sustain. 2023, 2, e254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklu, A.; Simane, B.; Bezabih, M. Effect of climate-smart agriculture innovations on climate resilience among smallholder farmers: Empirical evidence from the Choke Mountain watershed of the Blue Nile highlands of Ethiopia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jury, M.; Funk, C. Climatic trends over Ethiopia: Regional signals and drivers. Int. J. Climatol. 2012, 33, 1924–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, T.; Owidi, E.; Ndonye, S.; Achola, S.; Garedew, W.; Capitani, C. Community-based climate change adaptation action plans to support climate-resilient development in the eastern African highlands. In Handbook of Climate Change Resilience; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1417–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wale, W.; Tegegne, M.; Zeleke, M.; Ejegu, M.; Yegizaw, E. Determinants of farmers’ choice of land management strategies to climate change in drought-prone areas of Amhara region: The case of Lay Gayint Woreda, northwest Ethiopia. J. Degrad. Min. Lands Manag. 2020, 8, 2661–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Wan, C.; Ye, Q.; Yan, J.; Li, W. Disaster risk reduction, climate change adaptation and their linkages with sustainable development over the past 30 years: A review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2023, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrechorkos, S.H.; Hülsmann, S.; Bernhofer, C. Regional climate projections for East Africa: Evaluation of CMIP5 models and implications for climate change adaptation. Int. J. Climatol. 2019, 39, 1416–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Data Type | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Surveys | Survey responses from policymakers, sectoral experts, and EMI employees |

| 2 | Desktop review | Relevant government policy, planning, and operational documents related to climate change adaptation as well as journal review papers |

| 3 | Climate analysis | Rainfall and temperature observations (1991–2020) from EMI, gridded ENACTS datasets |

| 4 | Climate change projection | Selected key parameters from a subset of CMIP6 models (AWI-CM-1-1-MR, CanESM1, ACCESS-CM2, and FGOALS-g3) |

| Climate | Trends (1985–2014) |

| Historical (1985–2014) | All models show relatively stable annual rainfall (~800–1200 mm) during the historical period, with minor inter-annual variability and no drastic trends in rainfall increase or decrease, suggesting a baseline of moderate climate stability. |

| Scenario | Projections (2015–2100) |

| SSP2-4.5 | (Moderate Mitigation): Rainfall increases gradually but remains within historical variability (~1000–1400 mm by 2100) and least extreme changes across models |

| SSP3-7.0 | (High Challenges): Higher variability, with some models (e.g., UKESM1) projecting spikes (~1600 mm) and others (e.g., AWI-CM-1-1-MR) showing more modest increases) UKESM1: Shows sharp spikes under SSP3-7.0 |

| SSP5-8.5 | (ACCESS-CM2: Very High Emissions): Most extreme projections RF (~1800 mm by 2100) UKESM1: Shows sharp spikes indicating high climate sensitivity exceeding (~1600 mm by 2100) AWI-CM-1-1-MR and CAMS-CSM1: More conservative in projections, with smoother trends (~1400 mm by 2100). |

| Climate | Trends (1985–2014) |

| Historical (1985–2014) | All models show relatively stable Tmax (~27–29 °C) with minor inter-annual variability and no drastic warming trends, suggesting a baseline of moderate temperature stability |

| Scenario | Projections (2015–2100) |

| SSP2-4.5 | (Moderate Mitigation) shows Tmax increases gradually, reaching ~29–30 °C by 2100 and least extreme changes across models |

| SSP3-7.0 | (High Challenges) indicates faster warming, with Tmax reaching ~30–31 °C by 2100 and higher variability in some models (e.g., ACCESS-CM2) whereas SSP5-8.5 Other models (e.g., AWI-CM-1-1-MR) show milder increases (~30–31 °C) |

| SSP5-8.5 | AWI-CM-1-1-MR indicates more conservative, with Tmax reaching ~30 °C under SSP5-8.5 FGOALS-g3 and CanESM5 show intermediate trends, with Tmax peaking at ~30–31 °C ACCESS-CM2 projects the highest Tmax extremes under SSP5-8.5 (~33 °C by 2100) and suggests accelerated warming after 2050. |

| Climate | Trends (1985–2014) |

| Historical (1985–2014) | models show relatively stable Tmin (~14–18 °C) during the historical period, with minor fluctuations and no drastic cooling or warming trends, indicating a baseline of moderate |

| Scenario | Projections (2015–2100) |

| SSP2-4.5 | SSP2-4.5 (Moderate Mitigation Tmin increases gradually, reaching ~16–18 °C by 2100 and least extreme changes across models |

| SSP3-7.0 | SSP3-7.0 (High Challenges); Faster warming, with Tmin rising to ~17–19 °C by 2100 and higher variability in models like CNRM-ESM2 |

| SSP5-8.5 | SSP5-8.5 (Very High Emissions); Most extreme warming on CNRM-CM6 and CNRM-ESM2 project Tmin up to ~18–20 °C by 2100 and EC-Earth3-Veg-LR FGOALS-g3 show milder increases (~17–18 °C). CNRM-CM6 and CNRM-ESM2: Project the highest Tmin extremes under SSP5-8.5 (~20 °C), suggesting accelerated nighttime warming, EC-Earth3-Veg-LR: More conservative, with Tmin peaking at ~17 °C under SSP5-8.5 and FGOALS-g3: Shows intermediate trends, aligning closely with EC-Earth3-Veg-LR. |

| Regional PM | Federal PM | Regional Exp | Federal Exp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very likely | 19 | 24 | 18 | 29 |

| Somewhat likely | 36 | 40 | 39 | 35 |

| Neutral | 25 | 19 | 24 | 26 |

| Not very likely | 14 | 10 | 14 | 8 |

| Not likely at all | 6 | 7 | 6 | 1 |

| Regional PM | Federal PM | Regional Exp | Federal Exp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weather observations | 16 | 22 | 16 | 33 |

| Weather forecast (Climate prediction) | 53 | 63 | 48 | 47 |

| Climate data analysis | 18 | 6 | 21 | 17 |

| Climate change projections | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Climate change adaptation | 8 | 4 | 12 | 2 |

| Regional PM | Federal PM | Regional Exp | Federal Exp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very satisfied | 17 | 30 | 27 | 40 |

| Satisfied | 58 | 53 | 47 | 50 |

| Neutral | 21 | 11 | 22 | 9 |

| Dissatisfied | 3 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Very dissatisfied | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Response Category | Value (%) |

|---|---|

| Long range forecasts | 33 |

| Climate monitoring | 12 |

| Analysis and assessment based on historical data | 10 |

| Historical climate data | 6 |

| El Nino monitoring and outlooks | 5 |

| Climate change projections | 5 |

| Long term trends | 6 |

| Others (please specify) | 3 |

| Response Category | Value (%) |

|---|---|

| Very unlikely | 20 |

| Unlikely | 29 |

| Neutral | 32 |

| Likely | 12 |

| Very likely | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tola, F.T.; Dadi, D.K.; Kenea, T.T.; Dinku, T. The Role of Climate Services in Supporting Climate Change Adaptation in Ethiopia. Land 2025, 14, 2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112251

Tola FT, Dadi DK, Kenea TT, Dinku T. The Role of Climate Services in Supporting Climate Change Adaptation in Ethiopia. Land. 2025; 14(11):2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112251

Chicago/Turabian StyleTola, Fetene Teshome, Diriba Korecha Dadi, Tadesse Tujuba Kenea, and Tufa Dinku. 2025. "The Role of Climate Services in Supporting Climate Change Adaptation in Ethiopia" Land 14, no. 11: 2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112251

APA StyleTola, F. T., Dadi, D. K., Kenea, T. T., & Dinku, T. (2025). The Role of Climate Services in Supporting Climate Change Adaptation in Ethiopia. Land, 14(11), 2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112251