Abstract

As climate conditions and agricultural technologies change, the soil seed bank may increase or decrease, which may affect the species composition and abundance of weeds in crops. The research was carried out in order to evaluate the influence of hillside parts on the number of viable seeds during different seasons (spring and autumn) in agrophytocenoses, which differ in the duration of the land’s covering with plants. Soil samples have been taken out in spring and autumn at the summit, midslope, and footslope of the hill. The time of the soil sample collection and covering of agrophytocenoses had a significant effect on soil seed numbers. In autumn, the average seed amount in the soil was higher by 6.38% than in spring. The largest seed number (in spring and autumn) was evaluated in the soil of cereal–grass crop rotation with a 2.0- and 6.9-times higher seed amount compared to the rotation with a row crop and permanent grassland. During the years, hill parts had a significant effect on the seed bank in autumn. In spring, the viable seeds comprised 67.10%, and in autumn, they comprised 65.33% of the total seed number. Significantly, the highest percentage of viable seeds was estimated in the footslope of the hill. This can be related to more favorable microclimatic conditions and higher soil moisture at the footslope, where more fertile soil and organic matter naturally accumulate, creating better conditions for seed viability preservation.

1. Introduction

Seeds are the primary mechanism through which plants spread throughout the landscape. The final fate of dispersed seeds significantly influences the composition and dynamics of ecosystems. After being released from the parent plant and landing on the soil surface, seeds may move due to surface runoff. In ecosystems that are characterized by high spatial variability and intense rainfall, such runoff-driven events can help seeds reach new sites with more suitable conditions for germination and seedling establishment [1]. The most important variable influencing seed distribution is the hill slope mechanism [2]. Over time, the dispersal-related structures and seed coats may decompose, leaving only the viable germination units [3].

Fenner [4] and Menalled [5] indicate that there can be up to one million seeds per square meter of the soil. Reine et al. and Janicka [6,7] state that in the soil of grassland the seed number is usually lower, that is 6.0 to 54.5 thousand per square meter of viable seeds per square meter of the upper soil layer (up to 20 cm depth). The density of soil seed banks (viable seeds) per square meter is typically highest at the soil surface and decreases with increasing depth [8].

The soil seed bank system exhibits a significant ecological complex, with a wide range of interactions and multi-trophic responses. Seed bank traits clearly adapt to different types of arable farming. Seed longevity is favored by frequent tillage, while seed mass is favored by plant competition. Seed morphology adapts in response to the increasing importance of wind as a dispersal mechanism [5,9].

In agrophytocenoses, the number of seeds in the soil is influenced by different soil tillage [10], the use of herbicides [11,12], and crops change [13,14]. Seed banks serve different aims: they let species such as annual weeds survive under winter conditions and germinate for many years regardless of the effective methods of control [15].

The seed amount in the soil is dynamic. Viable and non-viable as well as damaged and non-damaged seed parts in the soil seed bank show the relation between the seed access into the soil seed bank and its consumption [16,17]. On the other hand, the part of damaged, non-viable, and viable seeds also shows the seed bank type [18]. Seed mortality in soil is one of the key factors for the persistence and density fluctuations of plant populations, especially for annual plants [19]. Soil seed banks are generally defined by how long seeds remain viable over time, which depends mainly on the plant species [20]. Additionally, the absence of soil tillage has been shown to decrease the average age of seeds remaining viable in the seed bank [21].

According to the seed longevity, some authors divide the soil seed bank into a short-term seed bank, where the viable seeds survive for less than 1 year, and a persistent seed bank, where the viable seeds survive for more than 1 year. And the persistent soil seed bank is additionally divided into a short-term persistent seed bank, where the seeds can be detected for more than one but less than five years, and a long-term persistent seed bank, where the seeds survive for more than five years [22]. Other authors describe the seasonal variation in the seed bank [3,23,24]. In areas where vegetation changes are governed by an annual cycle, the amount and composition of the seed bank change seasonally [23]. To assess the total soil seed bank, samples should be taken in late autumn. To investigate the stable soil seed bank, the samples should be taken out in late spring.

The seasonal strategy of soil seed banks seems to be more of a function of species than of vegetation type or environment [25].

Only a few studies in the literature have analyzed erosion-affected soil and the seed bank within it, especially assessing cultivated soil in hilly terrain. In Lithuania, hilly terrain accounts for 50 percent of the surface. Most of the country has a moderately cold climate, while the west of Lithuania (due to the warming effect of the Baltic Sea) has a moderately warm climate. Protecting hilly fields, it is difficult to apply regular agricultural techniques. Reduced soil tillage application and perennial grasslands were the most important means for soil protection on the slopes of the hill. Although the total soil seed bank is expected to be the lowest in perennial grasslands, we hypothesize that the proportion of viable seeds is likely to be higher compared to soils under rotation systems.

This research was carried out in order to evaluate the influence of hillside parts on the number of viable seeds during different seasons (spring and autumn) in agrophytocenoses, which differ in the duration of the land’s covering with plants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site

In the manuscript, the data on erosion monitoring are used. The experimental site is located on the midslope soil of Žemaičiai Highland (lat. 55°577′ N, long. 22°482′ E, 185.0 m a.s.l.), where the soil is covered with various anti-erosion crop rotations. The steepness of the slope was 9–11°.

The average annual air temperature, according to the long-term average temperature (period of 1991–2020) in the west Lithuania, was 6.7 °C. The average precipitation in the year was 789 mm. Meteorological conditions in the period of 2020–2022 were very diverse; however, dry weather also dominated in 2020, 2021, and 2022: compared to the long-term average temperature through the year, the amount of precipitation reached, respectively, 95.8, 93.5, and 91.1% of the norm. The average temperatures in 2020–2022 were 2.27, 0.28, and 0.73 °C higher compared to the long-term average temperature.

The soil of the experimental site is slightly eroded Eutric Retisol [26] with a texture of sandy loam. Before the trial’s establishment in 2020, the soil of permanent grassland (PG) was moderate in organic carbon (Corg) content (1.05–1.38%), low in total nitrogen and mobile phosphorus (P2O5) and high in mobile potassium (K2O) content (0.114–0.137%; 26.2–46.2 and 191.5–241.8 mg kg−1 soil, respectively), with pHKCl 5.04–5.39.

The soil of cereal–grass crop rotation (CG) was low in Corg and total nitrogen content (0.83–1.08 and 0.078–0.104%, respectively), and high in mobile P2O5 and K2O content (148.2–196.3 and 148.2–164.7 mg kg−1 soil, respectively), with pHKCl 5.06–6.06.

The soil of the crop rotation with a row crop (RC) was low in Corg and total nitrogen content (0.67–0.88 and 0.064–0.088%, respectively), and high in mobile P2O5 and K2O content (151.8–212.7 and 147.2–164.3 mg kg−1 soil, respectively), with pHKCl 5.44–6.63.

2.2. Trial Factors and Treatments

Factor A. Agrophytocenosis: (1) PG (100 percent of the land’s covering), (2) CG crop rotation (70 percent of the land’s covering), and (3) RC crop rotation (50 percent of the land’s covering). Factor B. Part of the hill: (1) summit (S), (2) midslope (M), and (3) footslope (F) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Experimental design, 2020–2022.

The mixture of perennial grasses for PG, which consisted of 20% timothy grass (Phleum pratense L.), 20% red fescue (Festuca rubra L.), 20% meadow grass (Poa pratensis L.), 20% white clover (Trifolium repens L.), and 20% common bird–foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus L.), was sown in 1993. No fertilizers were applied to the grasslands.

The CG crop rotation consisted of Hordeum vulgare L. (2020), Triticum aestivum L. (spring crop) (2021), and Hordeum vulgare L., with undersown perennial grasses (2022).

The RC crop rotation consisted of Solanum tuberosum L. (2020) and Hordeum vulgare L., with undersown perennial grasses (2021), and perennial grasses (2022).

In CG, the primary soil tillage was reduced according to the need: Shallow ploughing (10–12 cm) or shallow ploughless tillage (8–10 cm). After harvesting, the stubble was left to overwinter. In RC, the primary soil tillage was moldboard ploughing (20–25 cm). Agrotechnics used in rotations were presented in detail by Skuodienė et al. [27].

2.3. Sample Preparation and Analysis

The seed bank was analyzed at 0–15 cm depths. The seed bank was analyzed using soil samples in the years 2020–2022: one part of the sample was taken in April before seed germination, another part of the sample was taken in September during or after the dispersal of seeds. In each treatment, 2 kg of soil was collected using a hand auger (in total, 54 samples). The soil was dried. Five 100 g samples were taken out of a 2 kg sample of the soil and weighed (270 samples in total and 100 g of soil each). Then, the soil samples were wet-sieved through a 0.25 mm sieve on purpose to wash out the soil contents by using the saturated salt solution (360 g/L at room temperature; prepared fresh each day). Samples were immersed in 500 mL of the solution in 1 L beakers and stirred gently to allow floating material (including viable seeds) to separate. The suspension was left to settle for approximately 10–15 min. The remainder of the mineral part of the soil was separated from the organic part. The retained material was then air-dried at room temperature before further analyses (e.g., seed counting and identification). Identification of the seeds was performed with 8.75× magnification binoculars. To determine seed viability, the forceps with “destructive crushing” were used. The seeds that crushed easily and appeared hollow or with degraded tissue were considered non-viable, while the seeds that resisted pressure and contained firm, white, or creamy endosperm were classified as viable [28]. Identification manuals or guides were used. The number of viable seeds or total seeds (A) was recounted to thousands of seeds per m−2.

where A is the number of viable seeds or total seeds in thousands of seeds per m−2; n is the counted number of seeds or viable seeds in the soil sample; h is the depth of the plough layer in cm; and p is the soil bulk density in g cm−3.

A = n × h × p × 100

To evaluate the floristic similarity of phytocenoses or the similarity of the seed bank and existing vegetation, the coefficient of Sörensen (Cs) was applied. It was calculated using the formula:

where w represents the number of species shared by both compared situations, A is the total number of species in the first situation, and B is the number of species in the second situation.

Cs = 2w/(A + B),

The index of relative abundance of species expressed in percentage (P%) was calculated according to the formula:

where F% is the frequency of occurrence of every species:

where n is the number of samples in which species were found; N is the total number of samples in a model plot; Σ F% is the sum of frequencies of occurrence of all the plant species in a model plot.

P% = F%/Σ F% × 100,

F% = n/N × 100,

Chemical analyses were carried out at the Chemical Research Laboratory of the Institute of Agriculture, Lithuanian Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry. Before establishing the experiment, soil agrochemical characteristics were determined from the samples taken at depths of 0–5 and 5–15 cm. Soil acidity (pHKCl) was analyzed according to ISO 10390:2005 using the potentiometric method with the extraction of 1 M of KCl (pHKCl). Mobile P2O5 and K2O were analyzed according to the Egner–Riehm–Domingo (AL) method (LVP D–07:2016), the total nitrogen content was analyzed according to the Kjeldahl method, and the Corg content was determined using the Dumas dry combustion method. Soil bulk density was determined with a 100 cm−3 cylindrical drill using the Kachinsky method. Considering the percentage of sand, silt, and clay fractions, the soil texture was determined with the Fere triangle (FAO recommended method).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The significance of the differences between the average values was assessed according to Fisher’s protected Least Significant Difference (LSD) at a p ≤ 0.05 probability level. The experimental data were subjected to the two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) [29]. The actual data of the seed number were transformed as follows:

Sqr(x + 1)

3. Results

3.1. Seasonal Variation in Density of Soil Seed Bank

Only Factor A (agrophytocenosis) had a significant impact on the total (viable and non–viable) seed number in the 0–15 cm depth in the spring of all years of the investigation (Table 1). The total seed number in spring was determined to be the lowest (on average 5.68 thousand seeds m−2) in the soil of PG (Table 2), while the highest (39.09 thousand seeds m−2) was in the soil of CG. In the soil of CG, the number of seeds was 2.0 and 6.9 times higher compared to the RC and PG.

Table 1.

Significance of the impact of agrophytocenoses and parts of the hill on seed number and percentage of viable seeds according to the F-test.

Table 2.

The effect of agrophytocenoses and parts of the hill on the seed number (thousand m−2) and viable seeds (%).

In spring, the number of seeds in the soil did not depend on the hill parts. The differences received were not significant. Regardless of the agrophytocenosis, the total seed number consistently decreased in the downslope direction: 24.47, 22.33, and 17.60 thousand seeds m−2, respectively, in the soil of the summit, midslope, and footslope. Although the hill parts did not have a significant influence on seed reserve in spring, the seed reserve in the soil of the summit of the hill was 8.72 and 28.07% higher compared to the soil of the midslope and footslope of the hill.

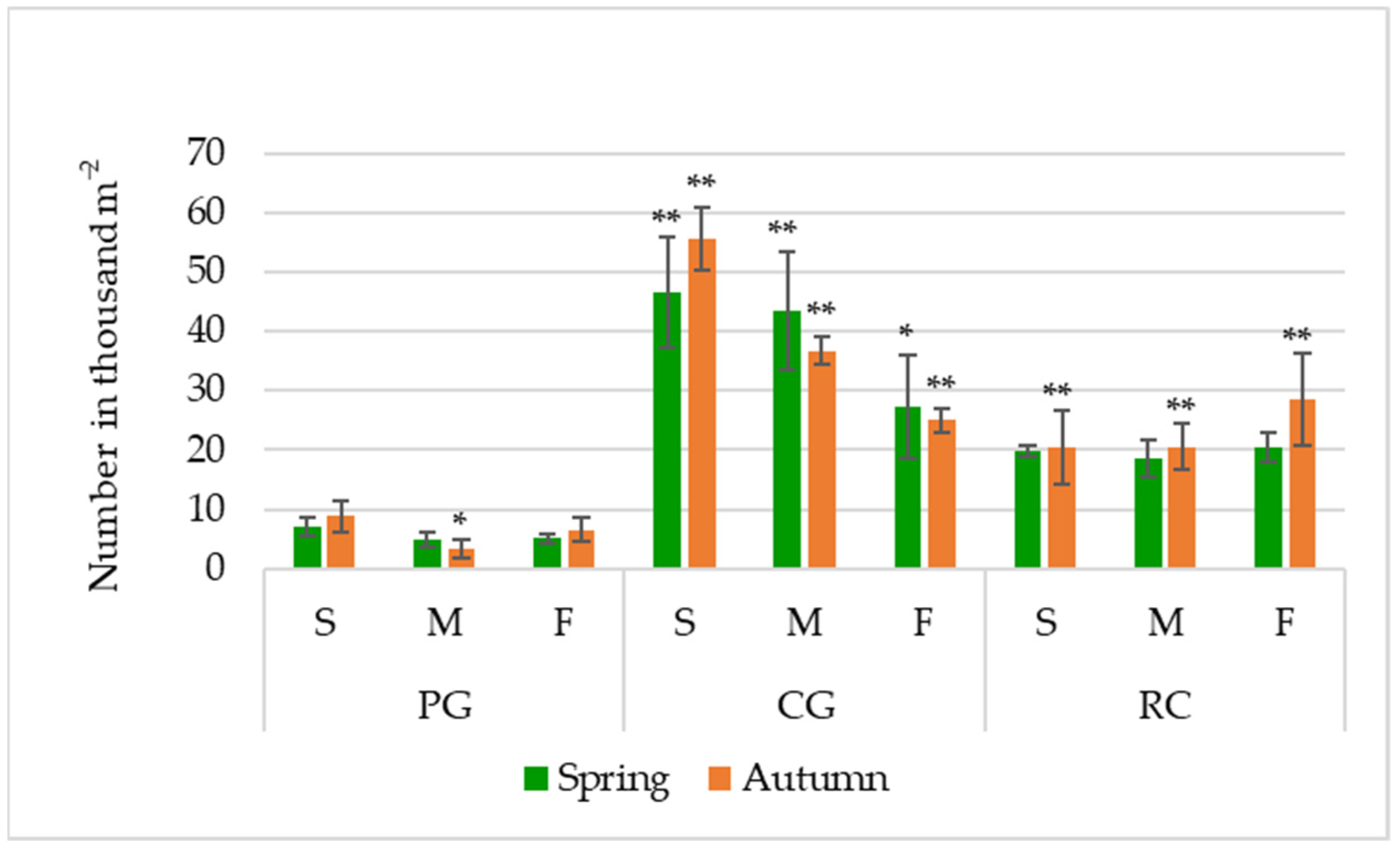

The influence of the agrophytocenoses manifested itself not only directly, but also through the interaction with parts of the hill (Table 2). Significantly more seeds were determined in the summit and the midslope of the CG. Regardless of the parts of the hill, in both crop rotations, the soil seed bank was higher (18.55–46.53 thousand seeds m−2) (Table 2, Figure 1), compared to the PG.

Both of the investigated factors (agrophytocenoses (factor A) and parts of the hill (factor B) had a significant impact on the total seed number in the 0–15 cm soil depth in autumn of all investigation years (Table 2). In autumn, significantly the least (on average 6.22 thousand seeds m−2) total seed number was determined in the soil of PG, while the highest (39.11 thousand seeds m−2) seed number was evaluated in the soil of CG (Table 2). In the soil of CG, the number of seeds was 1.7 and 6.3 times higher than in the RC and PG.

In autumn, the significant influence of the hill parts showed up on the soil seed number (Table 1). Most of the seeds (28.27 thousand seeds m−2) were evaluated in the soil seed bank of the summit of the hill (Table 2). In the midslope and footslope of the hill, the average number of seeds was evaluated to be 28.55 and 29.11% lower compared to the summit.

The impact of agrophytocenoses showed up not only directly, but also through the interaction with parts of the hill. Significantly higher seed numbers were evaluated in all parts of the hill of both rotations compared to PG (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Seed bank (viable and non–viable seeds) in the soil (seeds number in thousand m−2); PG: permanent grassland; CG: cereal–grass crop rotation; RC: crop rotation with a row crop; S: summit; M: midslope; F: footslope; * and ** indicate significance at p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01, respectively. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

Based on the average data in autumn, the seed number in the soil was 22.84 thousand seeds m−2 or 6.38% higher than in spring.

In spring, the total number of seed species in the soil of PG was evaluated to be 37, in the soil of CG, it was 31, and in the soil of RC, it was 25 (Table 3, Tables S3, S5 and S7). In crops, the number of species was evaluated to be, respectively, 68, 25, and 29 (Table 3, Tables S1 and S2). The number of the same plant species was evaluated to be 13, in the soil of CG, it was 14, and in the soil of RC, it was 11.

Table 3.

The number of seed species in the soil and the plant species in the vegetation.

In autumn, the total number of seed species in the soil of PG was evaluated to be 30, in the soil of CG, it was 27, and in the soil of RC, it was 26 (Table 3, Tables S4, S6 and S8). In crops, the number of species was evaluated to be, respectively, 68, 26, and 32 (Table 3, Tables S1 and S2). The number of the same plant species was evaluated to be 13, in the soil of CG, it was 11, and in the soil of RC, it was 11.

In spring and autumn, Chenopodium album L., Lotus corniculatus, and Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop. were the prevailing species in the soil of PG (Table S3), while Festuca rubra was the most dominant species in PG (Table S2).

In spring, Erysimum cheiranthoides L., Fallopia convolvulus (L.) A. Löve, and Setaria viridis P.B. were the prevailing species in the soil of CG, while in autumn, the prevailing species were Echinochloa crus-galli L., Chenopodium album, and Viola arvensis Murr. (Tables S5 and S6). Poa annua L., Setaria viridis, and Viola arvensis were the most dominant species in the CG crop rotation (Table S1).

In spring, in the soil of RC, the prevailing species were Fallopia convolvulus, Chenopodium album, and Viola arvensis, while in autumn the prevailing species were Chenopodium album, Fallopia convolvulus, Viola arvensis, and Echinochloa crus-galli (Tables S7 and S8). The most dominant species in RC crop rotation were Setaria viridis, Fallopia convolvulus, and Equisetum arvense L. (Table S1).

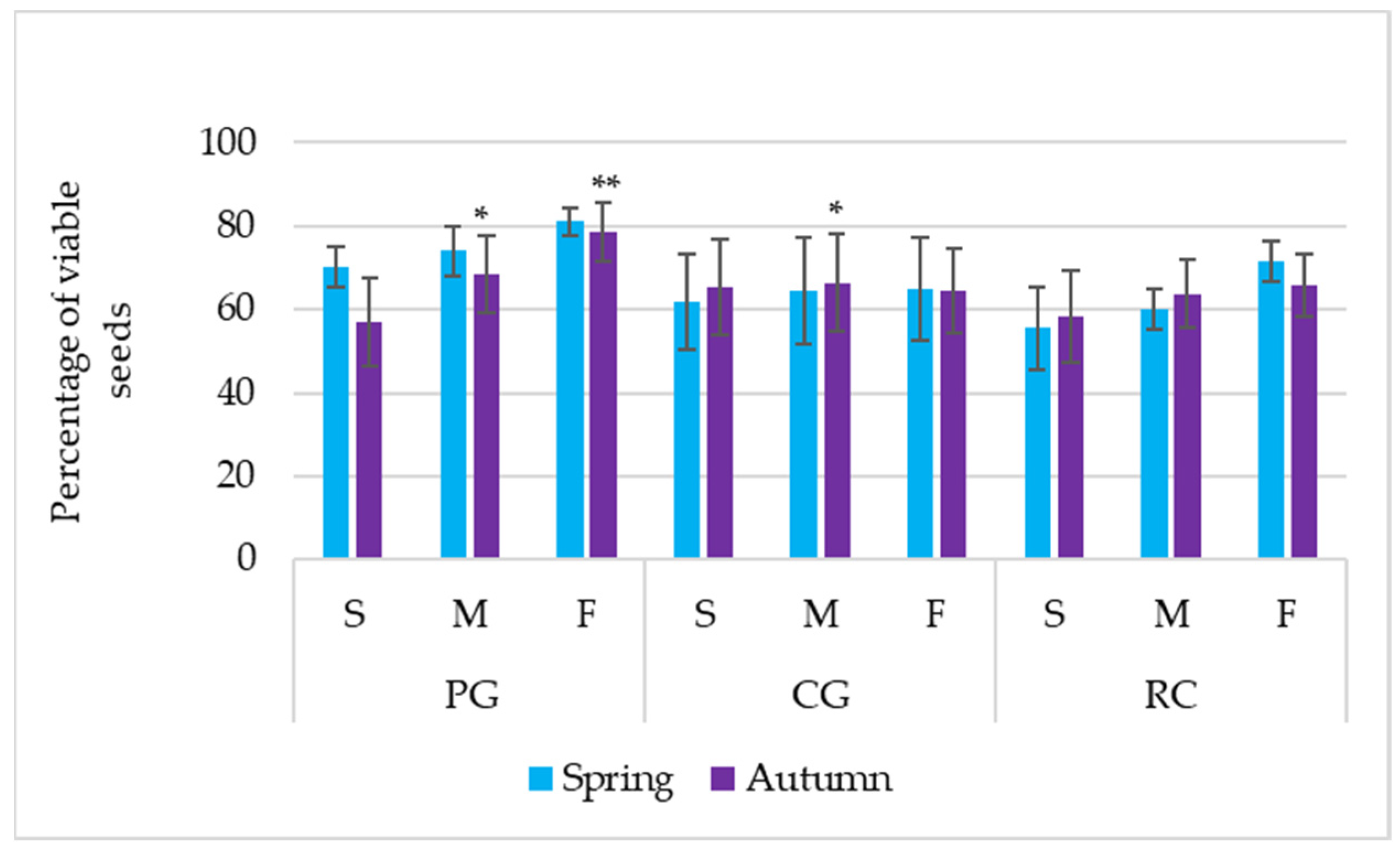

3.2. Seed Viability

On average, the number of viable seeds in spring and in autumn was similar, respectively, 67.10 and 65.33% of the total seed number. Only Factor A (agrophytocenosis) had a statistically significant effect on the viable seed number in spring. In autumn, the number of viable seeds significantly depended on the interaction of the examined factors.

In spring, there were 75.07, 63.85, and 62.38% of viable seeds of the total seed number determined in the soil seed bank, respectively, in the soil of PG, CG, and RC (Table 2). On the other hand, irrespective of the agrophytocenosis, significantly, the highest percentage of viable seeds was evaluated in the footslope (72.56%), while the lowest percentage (62.55%) was in the summit of the hill. Evaluating the results of agrophytocenosis × hill parts combination, there was no interaction determined (Table 1).

In autumn, viable seeds of the soil seed bank comprised 68.04, 65.38, and 62.58% of the total seed number, determined during the analysis process, respectively, in the soil of PG, CG, and the RC. Irrespective of the agrophytocenosis, significantly, the highest percentage of viable seeds was determined in the footslope (69.61%), while the least percentage (60.27%) was in the summit of the hill (Table 2). Evaluating the results of agrophytocenosis × hill parts combination, the interaction was determined; a statistically higher percentage of viable seeds was found in the soil of the midslope and footslope of PG and the midslope of CG (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of viable seeds in the soil bank. PG: permanent grassland; CG: cereal–grass crop rotation; RC: crop rotation with a row crop; S: summit; M: midslope; F: footslope; * and ** indicate significance at p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01, respectively. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Seasonal Variation in Density of Soil Seed Bank

Soil seed bank formation is essential to understand the processes of weed survival in agricultural land as well as plant succession [30]. Various vegetation types differ in their seed bank properties, such as the seed density and the richness of the seed species [31,32]. The seed number in the soil varies both in area and time [33]. The seed bank refills itself with seeds matured during the plant vegetation or the seeds brought by wind or water, but together it disappears because a part of the seeds decomposes or is destroyed by the fauna of the soil until spring. Thompson and Grime [23] used seasonal variation for the moderate climate regions to distinguish the seed banks of winter and summer.

During three years of our research, the highest seed reserve was determined in the soil of cereal–grass crop rotation, taking the samples both in early spring and autumn. One of the reasons was the use of reduced soil tillage. Such a way of tillage was chosen to reduce soil erosion: the stubble was left for the autumn–winter period, and in spring, the shallow soil tillage was applied. Reduced soil tillage slows down the physical movement of the seeds, their destruction, and germination; therefore, more seeds remain in the soil; i.e., the soil seed bank expands. Another reason is that in 2020, the control of Setaria viridis with herbicides was not successful, so the next year it spread even more. It is believed that these two circumstances determined the high seed number in the soil of CG. The similarity (Cs) between the seed bank and the plant community at the site was 50 and 42%. Echinochloa crus-galli, Viola arvensis, and Setaria viridis species have been found both in the seed bank and in crop rotations [34]. The majority of seeds entering the seed bank come from annual weeds growing in the fields [35]. During the vegetation period of the plants, the flowering weeds rapidly produce their seeds to maturity [36] and are adapted to distribute them widely [37]. Therefore, the soil seed bank density increased in autumn due to the maturation of plant seeds. The redistribution of dispersed seeds is mostly due to natural processes and tillage [38,39,40]. Due to reduced soil tillage, a higher proportion of seeds grown last year remain in the upper soil layer [41].

The lower seed number (49.78 and 40.73%, respectively, in spring and autumn) in the soil of RC compared to CG was influenced by traditional soil tillage. If seeds are raised closer to the surface, this could enhance germination. Thus, the seeds are distributed more evenly in the arable layer [27]. The similarity (Cs) between the seed bank and the plant community at the site was 41 and 38%, respectively, in spring and in autumn. Setaria viridis, Viola arvensis, Fallopia convolvulus, and Echinochloa crus-galli species have been found in the seed bank as well as in crop rotations [42]. The smallest seed bank was found in the soil of PG. The soil seed bank of PG was composed of the arable weeds [43]. The seeds accumulated in the soil did not correspond to the species composition of the grassland community. The similarity (Cs) between the seed bank and the plant community at the site was low (25–27%). Lotus corniculatus and Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop. species have been found both in the seed bank and in the grassland. The seeds of Chenopodium album comprised the great part of the seed bank [42].

The density and species richness of seeds in the seed bank may peak at the end of a vegetation season, when seeds mature and are dispersed from the mother plants [24]. The results of the research show that due to mature plant seeds during the plant vegetation period, the seed reserve in autumn increased by 9.51% in the soil of PG, and by 18.08% in the RC. In the soil of CG in autumn, the seed reserve increased marginally (Table 2). Seed rain from parent plants is generally the primary input into the seedbank of arable fields [44]. Seed input varies depending on environmental conditions, farming practice (tillage, management intensity, and particularly the frequency of winter cropping), weed species, fertility, and local vegetation [45,46].

Soil seed banks show very high spatial heterogeneity as a result of dispersal contingencies, and the density of seeds per unit area varies significantly over small distances, leading to dense or relatively seed-free areas [47,48]. Due to unequal soil erosion in various parts of the hill, the environmental conditions for plant development become different, involving soil nutrients, acidity, moisture, mold, and others [49]. Soil moisture determines the duration of physical maturity and seed germination conditions [50]. Due to the effect of the organic carbon and nitrogen amount of the mother plant, the soil seed bank is influenced as well [51]. The accessibility of nutrients for plants, biological activity, and plant fertility depends on the amount of organic carbon [52]. In our research, the significant influence of hill parts was determined by the seed number in autumn—when the direct dispersion of seeds away from mother plants finishes—because most of the weed seeds mature in the second part of summer. Due to new seed dispersals and survival of the seeds spreading earlier, the seed numbers in the summit and footslope of the hill in autumn were determined to be higher by 15.53% and 13.86% compared to spring.

Both in spring and autumn, in the midslope and footslope of the hill, the number of seeds was determined to be lower in contrast to the summit. This could be impacted by the relief because in lower slope parts, the resources of moisture and the amount of nutrients increase; therefore, the conditions for crop plants’ growth become better (more competitive).

4.2. Seed Viability

Reproduction features and seed viability are very important in order for the cenopopulation to exist. An important biological characteristic of weeds is the permanent germination of their seeds. Weed seeds start to germinate just before the beginning of agricultural plants’ vegetation and germinate until the freeze-up. Murdoch and Ellis [53] indicate that the fate of viable weed seeds is determined by internal physiological conditions and the environmental factors encountered in the soil. Seed mortality in the soil is crucial for the ecosystem stability [54]. Seed mortality is caused by physiological changes in seeds, environmental damage [55], and pathogen influence [56]. An increase in the amount of soil organic matter determines the level of biological activity (germs, fungi, soil enzymes, insects, and worms), which can reduce seed viability in the soil [57,58].

Both in spring and autumn, a higher percentage of viable seeds was found in the soil of PG, while the lowest was in the RC. A lower percentage of viability in the RC could be evaluated by more intensive soil tillage, whereas when the soil is covered with permanent grassy cover (soil is not cultivated), there is no erosion and seed transportation because the vegetative plant cover creates a biological barrier [59]. Vegetation can radically control soil and water losses, meaning that the ability of rainfall to erode soil and disperse seeds is based on local surface [2]. Regardless of the season, the percentage of viable seeds in the summit of the hill was the least because the environmental conditions for plant germination and development are poorer in hill parts that lack moisture. Together with increasing soil moisture, the number of viable seeds decreased. In autumn, the interaction between all parts of the hill was not significant; otherwise, in spring, a moderately strong negative correlation was determined (r = 0.400, p ≤ 0.05; –r = 0.650, p ≤ 0.01) [59].

In spring, the percentage of viable seeds was marginally higher compared to the seeds found in autumn (Table 2). Seed germination in spring could reduce the percentage of viable seeds in autumn. Moreover, transportation with water flow can reduce the seed viability [60,61]. A strong dependence of seed viability and the annual amount of precipitation was determined (r = 0.802, p ≤ 0.01; 0.940, p ≤ 0.01, respectively, for the seed number in spring and autumn).

Depending on internal and external environmental factors and the types of species, the period of seed viability in the soil varies. Viability is influenced by aging; with an increase in age, the viability of seeds decreases until it stops completely [33].

The received data represent the impact of the season (spring and autumn) during the year. Seasonal soil temperature fluctuations control the process of seed germination. Summer is the period when most determined species have already dispersed the seeds; therefore, the soil seed bank in autumn is higher compared to early spring. The number of viable seeds in spring was evaluated to be 67.10%, and in autumn, it was 65.33% of the total seed number.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, irrespective of the season, significantly, the lowest total viable and non-viable seed number was determined in the soil of permanent grassland (100 percent of the land’s covering), while in arable soil (rotations with 70 and 50 percent of the land’s covering), it was significantly highest.

In terms of weediness, the rotation with sustainable soil tillage in the slope (70 percent of the land’s covering) of the hill was not as effective as the rotation with a row crop (50 percent of the land’s covering) because the seed bank was higher by 2.54, 2.07, and 1.10 times, respectively, in the summit, midslope, and footslope of the hill.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14112136/s1, Table S1: Plant species diversity and distribution (P%) of CG and RC; Table S2: Plant species diversity and distribution (P%) in PG; Table S3: Seed species diversity in the soil of PG (%), 2020–2022 spring; Table S4: Seed species diversity in the soil of PG (%), 2020–2022 autumn; Table S5: Seed species diversity in the soil of CG (%), 2020–2022 spring; Table S6: Seed species diversity in the soil of CG (%), 2020–2022 autumn; Table S7: Seed species diversity in the soil of RC (%), 2020–2022 spring; Table S8: Seed species diversity in the soil of RC (%), 2020–2022 autumn.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and D.K.; methodology, R.S., R.R. and D.K.; software, V.M.; validation, R.R. and R.S.; formal analysis, G.Š. and V.M.; investigation, R.S. and V.M.; curation, R.R., R.S., G.Š. and V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S., G.Š. and V.M.; writing—review and editing, R.S., D.K. and G.Š.; visualization, V.M.; supervision, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Lithuanian Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry, within the program “Productivity and sustainability agrogenic and forest soils”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| PG | Permanent grasslands |

| CG | Cereal–grass crop rotation |

| RC | Crop rotation with a row crop |

| S1–S8 | Supplementary Tables S1–S8 |

| Cs | Floristic similarity coefficients of Sörensen |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

References

- Bochet, E. The fate of seeds in the soil: A review of the influence of overland flow on seed removal and its consequences for the vegetation of arid and semiarid patchy ecosystems. Soil 2015, 1, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rouw, A.; Ribolzi, O.; Douillet, M.; Tjantahosong, H.; Soulileuth, B. Weed seed dispersal via runoff water and eroded soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 265, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatkamp, A.; Poschlod, P.; Venable, D.L. The Functional Role of Soil Seed Banks in Natural Communities. In Seeds—The Ecology of Regeneration in Plant Communities, 3rd ed.; Gallagher, R.S., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2014; pp. 263–295. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner, M. Seed bank dynamics. In Seed Ecology; Chapman and Hall, Broschürt: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Menalled, F.D. Manage the Weed Seed Bank—Minimize “Deposits” and Maximize “Withdrawals”. 2013. Available online: https://eorganic.org/node/2806 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Reine, R.; Chocarro, C.; Fillat, F. Soil seed bank and management regimes of semi–natural mountain meadow communities. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 104, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicka, M. The evaluation of soil seed bank in two Arrhenatherion meadow habitats in Central Poland. Acta Sci. Pol. Agric. 2016, 15, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Erfanzadeh, R.; Hendrickx, F.; Maelfait, J.P.; Hoffmann, M. The effect of successional stage and salinity on the vertical distribution of seeds in salt marsh soils. Flora 2010, 205, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D.R.; Benoit, D.L.; Swanton, C.J. Tillage effects on weed seed return and seedbank composition. Weed Sci. 1996, 44, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnoskie, L.M.; Herms, C.P.; Cardina, J. Weed seedbank community composition in a 35-yr-old tillage and rotation experiment. Weed Sci. 2006, 54, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.C.; Shaw, D.R. Effect of preharvest desiccants on weed seed production and viability. Weed Technol. 2000, 14, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.; Norsworthy, J.K. Influence of late-season herbicide applications on control, fecundity, and progeny fitness of glyphosate–resistant palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) biotypes from Arkansas. Weed Technol. 2012, 26, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanton, C.J.; Booth, B.D. Management of weed seedbanks in the context of populations and communities. Weed Technol. 2004, 18, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.L. Sequencing crops to minimize selection pressure for weeds in the Central Great Plains. Weed Technol. 2004, 18, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulden, R.H.; Shirtliffe, S.J. Weed Seed Banks: Biology and Management. Prairie Soils Crop J. 2009, 2, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Moravcová, L.; Gudžinskas, Z.; Pyšek, P.; Pergl, J.; Perglová, I. Seed ecology of Heracleum mantegazzianum and H. sosnowskyi, two invasive species with different distributions in Europe. In Ecology and Management of Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum), 2nd ed.; Pyšek, P., Cock, M.J.W., Nentwing, W., Ravn, H.P., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Taura, L.; Kamaitytė-Bukelskienė, L.; Sinkevičienė, Z.; Gudžinskas, Z. Study on the Rare Semiaquatic Plant Elatine hydropiper (Elatinaceae) in Lithuania: Population Density, Seed Bank and Conservation Challenges. Front. Biosci. 2022, 27, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Clef, M.; Stiles, E.W. Seed longevity in three pairs of native and non-native congeners: Assessing invasive potential. Northeast. Nat. 2001, 8, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee–Sanford, J.; Fu, X. Investigating the role of microorganisms in soil seed bank management. In Current Research, Technology and Education Topics in Applied Microbiology and Microbial Biotechnology; Méndez–Vilas, J., Ed.; Formatex Research Centre: Badajoz, Spain, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 257–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.M.; Begum, M. Soil weed seed bank: Importance and management for sustainable crop production—A review. J. Bangladesh Agril. Univ. 2015, 13, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, S. Natural weed seed burial: Effect of soil texture, rain and seed characteristics. Seed Sci. Res. 2007, 17, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.; Fenner, M. The functional ecology of seed banks. In Seeds: The Ecology of Regeneration in Plant Communities; Fenner, M., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1992; pp. 231–258. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, K.; Grime, J.P. Seasonal variation in the seed banks of herbaceous species in ten contrasting habitats. J. Ecol. 1979, 67, 893–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.X.; Liu, W.Y.; Cao, M.; Li, Y.H. Seasonal variation in density and species richness of soil seed–banks in karst forests and degraded vegetation in central Yunnan, SW China. Seed Sci. Res. 2007, 17, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csontos, P. Seed banks: Ecological definitions and sampling considerations. Community Ecol. 2007, 8, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. In International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-classification/universal-soil-classification/en/ (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Skuodienė, R.; Matyžiūtė, V.; Aleinikovienė, J.; Fercks, B.; Repšienė, R. Seed bank community change under different intensity agrophytocenoses on hilly terrain in Lithuania. Plants 2023, 12, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; James, T.K.; Grbavac, N.; Mellsop, J. Evaluation of two methods for enumerating the soil weeds seedbank. In Proceedings of the 48th New Zealand Plant Protection Conference, Angus Inn, Hastings, New Zealand, 8–10 August 1995; pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Raudonius, S. Application of statistics in plant and crop research: Important issues. Zemdirb. Agric. 2017, 104, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghersa, C.M.; Martínez–Ghersa, M.A. Ecological correlates of weed seed size and persistence in the soil under different tilling systems: Implications for weed management. Field Crops Res. 2000, 67, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plue, J.; Van Calster, H.; Auestad, I.; Basto, S.; Bekker, R.M.; Bruun, H.H.; Chevalier, R.; Decocq, G.; Grandin, U.; Hermy, M.; et al. Buffering effects of soil seed banks on plant community composition in response to land use and climate. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2020, 30, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; He, X.; Zhao, F.; Wang, D.; Jiao, J. Soil seed bank in different vegetation types in the Loess Plateau region and its role in vegetation restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, W.; Demissew, S.; Bekele, T. Ecology of soil seed banks: Implications for conservation and restoration of natural vegetation: A review. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 2018, 10, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuodienė, R.; Matyžiūtė, V. Soil Seed Bank in a Pre-Erosion Cereal-Grass Crop Rotation. Plants 2022, 11, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffret, A.G.; Cousins, S.A.O. Past and present management influences the seed bank and seed rain in a rural landscape mosaic. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 48, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcella, F.; Benech Arnold, R.L.; Sanchez, R.; Ghersa, C.M. Modelling seedling emergence. Field Crops Res. 2000, 67, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, S. Weed seed movement and dispersal strategies in the agricultural environment. Weed Biol. Manag. 2007, 7, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R. Weed Management Handbook; British Crop Protection Council and Blackwell Science: Alton, Hampshire, 2002; p. 423. [Google Scholar]

- Moonen, A.C.; Barberi, P. Size and composition of the weed seedbank after 7 years of diferent cover-crop-maize management systems. Weed Res. 2004, 44, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armengot, L.; Blanco-Morenoa, J.M.; Bàrberic, P.; Boccic, G.; Carlesic, S.; Aendekerkd, R.; Bernerb, A.; Celettee, F.; Grossef, M.; Huitingg, H.; et al. Tillage as a driver of change in weed communities: A functional perspective. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 222, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, S.; Claupein, W. Effect of tillage intensity on weed infestation in organic farming. Soil Tillage Res. 2009, 105, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyžiūtė, V. Soil Seed Bank in Different Agrophytocenoses of the Hilly Relief. Ph.D. Thesis, Lithuanian Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry, Akademija, Lithuania, 19 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Skuodienė, R.; Matyžiūtė, V. Assessment of an abandoned grassland community and the soil seed bank of a hilly relief. Zemdirb. Agric. 2022, 109, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.E.; Archer, L.; Boatman, N.D. Methods of determining weed seed inputs to the seed bank on arable land. In Seedbanks: Determination, Dynamics and Management; Bekker, R.M., Forcella, F., Grundy, A.C., Eds.; Association of Applied Biologists: Warwick, UK, 2003; pp. 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- De Cauwer, B.; Reheul, D.; Nijs, I.; Milbau, A. Management of newly established field margins on nutrient-rich soil to reduce weed spread and seed rain into adjacent crops. Weed Res. 2008, 48, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, C.; Squire, G.R.; Hallett, P.D.; Watson, C.A.; Young, M. Arable plant communities as indicators of farming practice. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 138, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K. Small-scale heterogeneity in the seed bank of an acidic grassland. J. Ecol. 1986, 74, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessaint, F.; Chadoeuf, R.; Barralis, G. Spatial pattern analysis of weed seeds in the cultivated soil seed bank. J. Appl. Ecol. 1991, 28, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monstvilaitė, J.; Kinderienė, I. Effect of relief on agrophytocenoses. In Proceedings of the Agronomic, Economic and Ecological Aspects of Crop Production on Hilly Soils of the Conference, Kaltinėnai, Lithuania, 25 May 2000; pp. 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Maikštėnienė, S. Agricultural practices inhibiting the effect of negative properties of heavy-textured soils. Zemdirbyste 1996, 53, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes, C.; Haughton, A.J.; Bohan, D.A.; Squire, G.R. Functional approaches for assessing plant and invertebrate abundance patterns in arable systems. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2009, 10, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frouz, J. Effects of soil macro- and mesofauna on litter decomposition and soil organic matter stabilization. Geoderma 2017, 332, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, A.J.; Ellis, R.H. Longevity, viability and dormancy. In Seeds: The Ecology of Regeneration in Plant Communities; Fenner, M., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1992; pp. 193–229. [Google Scholar]

- Gardarin, A.; Dürr, C.; Mannino, M.R.; Busset, H.; Colbach, N. Seed mortality in the soil is related to the seed coat thickness. Seed Sci. Res. 2010, 20, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, D.A. Seed Aging: Implications for Seed Storage and Persistence in the Soil; Comstock Publishing Associates: Ithaca, NY, USA; London, UK, 1986; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, M.; Mitschunas, N. Fungal effects on seed bank persistence and potential applications in weed biocontrol: A review. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2008, 9, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, J.; Monte, J.P.D.; López–Fando, C. Weed seedbank response to crop rotation and tillage in cemiarid agroecosystems. Weed Sci. 1999, 47, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennimore, S.A.; Jackson, L.E. Organic amendment and tillage effects on vegetable field weed emergence and seedbanks. Weed Technol. 2003, 17, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuodienė, R.; Matyžiūtė, V.; Šiaudinis, G. Soil Seed Banks and Their Relation to Soil Properties in Hilly Landscapes. Plants 2024, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousens, R.; Dytham, C.; Law, R. Dispersal in Plants: A Population Perspective; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oost, K.; Govers, G.; De Alba, S.; Quine, T.A. Tillage erosion: A review of controlling factors and implications for soil quality. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2006, 30, 443–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).