Abstract

As the driving force of China’s green development, cities play a pivotal role in carbon sequestration, with their green and blue spaces jointly influencing both carbon sequestrations and carbon emissions. Yet, most existing studies rely on linear analyses, limiting the capture of nonlinear characteristics and overlooking cross-city differences in spatial configurations. Variations in spatial structures, morphology, and distribution of blue–green spaces may lead to divergent sequestration mechanisms, highlighting the need for comparative research. This study selects five high-density cities in the middle and lower Yangtze River Basin (2000, 2010, 2020) as case studies. Using the XGBoost-SHAP model, we investigate the correlations between blue–green space patterns and carbon sequestration benefits across cities. Results show that key indicators vary by city: patch shape complexity, patch area, and connectivity significantly affect sequestration benefits across all cases, while patch proximity, size, shape, and spatial aggregation matter in specific cities. This study provides a reference for optimizing urban blue–green space configurations from the perspective of carbon sequestration benefits and offers a direction for further exploration of their underlying mechanisms. At the planning level, the study identifies key indicators influencing carbon sequestration across different urban forms, providing a scientific basis for context-specific optimization of blue–green space structures and for promoting low-carbon and resilient urban development.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the growing frequency of extreme weather events driven by global warming has created serious environmental and social challenges, posing a significant threat to sustainable development. Although urban areas occupy only about 3% of the global land surface, they accommodate more than half of the world’s population and generate over 70% of global carbon emissions. Promoting a green and low-carbon transition within urban spaces is therefore essential to achieving sustainable development goals.

Urban blue–green space (UBGS) encompasses all natural, semi-natural, and artificial green areas and water bodies, including both preserved and newly created spaces [1]. UBGS plays a vital role in urban ecosystems, characterized by shared ecological properties and strong interconnections in ecological functions, material cycles, and energy flows [2]. Together, green and blue spaces form the urban natural carbon sequestration system: directly enhancing carbon storage and indirectly contributing to emission reduction. Numerous studies have shown that the spatial configuration of UBGS significantly affects carbon sequestration benefits, with green spaces generally showing stronger carbon sequestration capacity than other spatial elements [3]. Furthermore, blue and green spaces exert synergistic effects [4]: blue spaces can enhance the carbon sequestration performance of green spaces [5]. These synergies operate through multiple ecological mechanisms. For instance, blue spaces can contribute to microclimate regulation by mitigating the urban heat island effect, improving air humidity, and enhancing vegetation photosynthetic efficiency, which collectively promote carbon uptake [6]. In addition, the synergistic interaction between blue and green systems enhances ecosystem connectivity and resilience [7]. These synergistic processes optimize the environmental conditions for carbon fixation and reinforce the long-term stability of urban carbon sinks. However, most research on the relationship between UBGS patterns and carbon sequestration efficiency has focused on single cities [8,9,10], few studies have conducted multi-city comparative analyses under similar climatic conditions. In practice, cities differ considerably in terms of climatic conditions, geomorphological features, and urban built environments. Comparative studies among cities under similar climates are therefore essential for revealing the mechanisms by which UBGS patterns influence carbon sequestration benefits. Nevertheless, such comparative analyses remain limited, and systematic investigations into the key UBGS pattern factors affecting carbon sequestration benefits and their intercity differences are still insufficient.

Previous studies have often used Pearson or Spearman correlation analyses to explore the relationship between individual variables and ecological benefits. Some have also adopted multiple linear regression methods to identify the influence patterns of multiple feature variables on ecological outcomes [11]. These methods rely on generalized linear assumptions between dependent and independent variables. However, such assumptions are inadequate for describing nonlinear interactions. In urban environments, green and blue spaces are highly interwoven and functionally interconnected. Compared with isolated green or blue spaces, their combined impacts on carbon sequestration benefits are far more complex and diverse [12,13]. Therefore, traditional linear approaches have inherent limitations in investigating the effects of UBGS patterns on carbon sequestration efficiency [8]. To overcome these limitations, recent research has increasingly applied machine learning methods such as Random Forest (RF) [14], Boosted Regression Trees (BRT) [15], and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) [16]. Compared with RF and BRT, XGBoost offers higher training efficiency, greater capability in handling large-scale and high-dimensional datasets, and stronger generalization performance, while its regularization mechanism reduces overfitting risk. XGBoost has been successfully applied in vegetation carbon sequestration estimation [17] and analyses of the relationships between green space pattern metrics and net primary productivity (NPP) [8], demonstrating its accuracy and robustness in capturing complex linkages between environmental characteristics and ecological effects. To further address the interpretability challenge of machine learning methods, the SHAP model can be applied to quantify the contribution of each feature to the model output. SHAP provides both global-level interpretability of the entire model and local-level interpretability for individual features. Thus, the integration of XGBoost with SHAP offers an effective framework for exploring the relationships between UBGS pattern characteristics and carbon sequestration benefits across multiple cities.

In summary, this study focuses on the central urban areas of five high-density cities in the middle and lower Yangtze River Basin to investigate the comprehensive impacts of UBGS patterns on carbon sequestration benefits. First, five representative cities-Wuhan, Hefei, Nanjing, Suzhou, and Shanghai-are selected, and a multi-level indicator system for UBGS patterns is constructed. Second, the XGBoost-SHAP model is applied to evaluate the relative importance of various indicators under different urban contexts and to identify the key factors influencing carbon sequestration efficiency. Finally, by integrating the characteristics of UBGS patterns in each city, this study reveals the differentiated mechanisms through which pattern elements (e.g., patch area, shape complexity, connectivity, and spatial distribution) affect carbon sequestration capacity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

The five case cities-Nanjing, Hefei, Wuhan, Suzhou, and Shanghai-are all located in economically developed and densely populated regions of China, and they face common environmental pressures associated with rapid urbanization. The selection of these cities is based on three main considerations.

First, the cities share similar natural and climatic conditions. All five are situated within the subtropical monsoon climate zone, characterized by hot and rainy summers, mild and relatively dry winters, distinct seasonal variation, strong monsoon influence, and comparable vegetation types. Second, the spatial patterns of blue–green spaces in the five cities exhibit both similarities and differences. Wuhan and Hefei contain extensive lake systems within their central urban areas, with most large green spaces distributed along the urban periphery. In contrast, Shanghai and Suzhou are characterized by dense water networks, where blue–green spaces form a grid-like structure combining point, line, and surface elements, with green spaces showing pronounced fragmentation. Nanjing’s central urban area, meanwhile, contains several large green space patches. Third, the urban development structures of the five cities are distinct yet representative. Wuhan is a typical monocentric city, expanding concentrically from the main urban core. Hefei has undergone rapid urban expansion in recent years, gradually transforming from a monocentric to a polycentric development pattern. Nanjing, Shanghai, and Suzhou have highly urbanized central districts. Shanghai exhibits a typical ring–radial urban form, while Nanjing and Suzhou demonstrate tendencies toward polycentric, clustered, and networked urban development. Overall, the inclusion of these five cities provides a representative cross-section of high-density metropolitan areas in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River Basin, which are experiencing rapid landscape transitions, intense human activity, and substantial carbon emissions. These cities exemplify the ecological and environmental pressures faced by fast-growing urban regions worldwide. Therefore, analyzing their blue–green space patterns and carbon sequestration dynamics is of particular significance for understanding how urban ecosystems can mitigate carbon emissions. It not only deepens insights into regional ecological processes in China but also contributes to the broader international scientific debate on how urban form and ecological spatial structures influence carbon sequestration capacity under rapid urbanization.

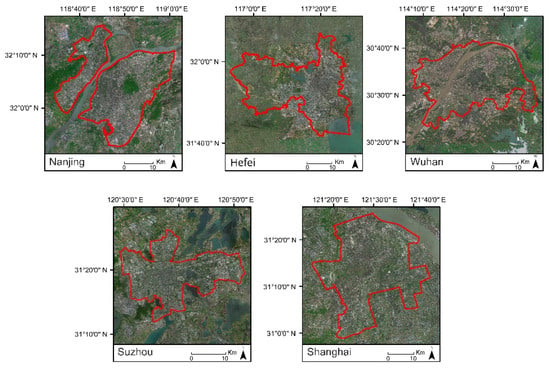

Accordingly, the central urban areas of these five cities are selected as the study areas (Figure 1). An overview of the blue–green space characteristics of each city is provided in Table 1. To minimize potential errors arising from remote sensing data accuracy and extreme weather conditions in any single year, three study periods-2000, 2010, and 2020-are chosen.

Figure 1.

Scope of research subjects.

Table 1.

Blue–green space profile of central urban areas in the case cities.

2.2. Data Sources and Processing

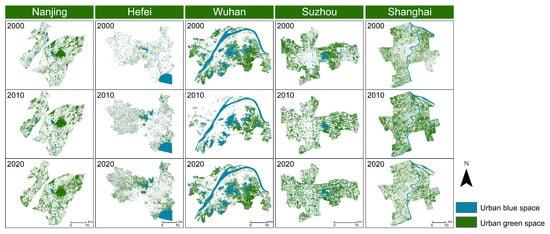

The datasets used in this study include land-use data, meteorological data, vegetation type data, and NDVI data (Table 2). Landsat remote sensing images for the years 2000, 2010, and 2020 were obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud platform (https://www.gscloud.cn/ (accessed on 13 December 2024)), with an original spatial resolution of 30 m. Preprocessing of the remote sensing images—including radiometric calibration, atmospheric and geometric correction, and stripe repair—was conducted using the Google Earth Engine platform. All datasets were subsequently resampled to a spatial resolution of 15 m using the bi-linear interpolation method to ensure spatial consistency while minimizing infor-mation loss. Following the classification system of the Chinese Land Use/Cover Change (LUCC) dataset, the processed images were classified into six categories: cropland, forest land, grassland, built-up land, water bodies, and unused land. Land-use classification data for each of the five cities in the three study years were obtained, and classification accuracy was evaluated and validated using the Kappa coefficient. The overall classification accuracy reached 85%, with a Kappa coefficient above the minimum reliability threshold, confirming the robustness of the classification results. Using ArcMap 10.8, forest land and grassland were reclassified as green space, while water bodies were reclassified as blue space, thereby generating blue–green space distribution maps for the central urban areas of the five cities in 2000, 2010, and 2020 (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Basic data sources.

Figure 2.

UGBL distribution maps for each period in the five cities.

2.3. Research Methods

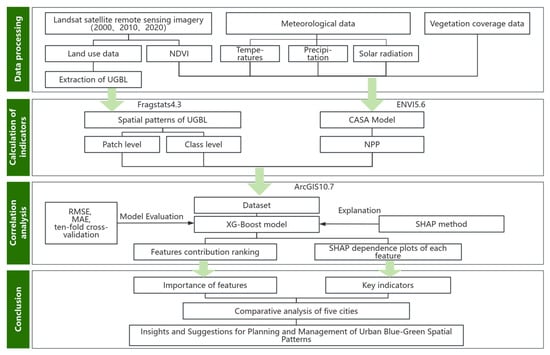

This study consists of four main components: (1) quantification of blue–green space pattern characteristics, (2) calculation of carbon sequestration benefits, (3) identification of key influencing factors, and (4) analysis of underlying mechanisms. First, landscape metrics at both patch and class levels were selected to quantify the spatial characteristics of blue–green spaces. Second, the CASA model was applied to calculate the net primary productivity (NPP) of the five case cities for the three study years. Third, random sampling points were generated to construct datasets, and an XGBoost model was developed to establish the relationships between UBGS pattern characteristics and NPP. By calculating SHAP values, the contributions of different UBGS pattern features to carbon sequestration benefits were examined. Finally, a comparative analysis was conducted to identify the key blue–green space indicators influencing carbon sequestration across the five cities, highlighting both similarities and differences in the mechanisms of carbon sequestration benefits. The overall research workflow is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Research Framework.

2.3.1. Quantification of Urban Blue–Green Space Patterns

An indicator set was constructed to quantify the blue–green space patterns of the five case cities. Landscape metrics at both the patch level and the class level were selected to represent the spatial characteristics of urban blue–green spaces. Spearman correlation analysis was applied to filter highly correlated indicators, and further selection was conducted from four dimensions: area, connectivity, shape complexity, and aggregation. The final set of blue–green space pattern indicators for each city (Table 3) was then calculated using Fragstats 4.3 software.

Table 3.

Indicators of the spatial patterns of UBGS.

2.3.2. Calculation of NPP Using the CASA Model

Vegetation Net Primary Productivity (NPP) was used to characterize the carbon sequestration capacity of urban blue–green spaces, and the CASA model was adopted for estimation. The CASA model, proposed by Potter et al. in 1993, describes ecological processes in which the fluxes of H2O, C and N vary over time within terrestrial ecosystems, and is particularly suitable for NPP research and estimation at the regional scale. The calculation formula is as follows:

where NPP(x,t) represents the net primary productivity of pixel x in month t (gC·m−2·a−1); APAR(x,t) represents the absorbed photosynthetically active radiation of pixel x in month t (gC·m−2·month−1); and ε(x,t) represents the actual light use efficiency of pixel x in month t (gC·MJ−1).

The absorbed photosynthetically active radiation of vegetation depends on solar radiation and plant characteristics, and is calculated as:

where SOL(x,t) is the total solar radiation of pixel x in month t (MJ·m−2·month−1); FPAR(x,t) is the fraction of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation by vegetation; and 0.5 is a constant representing the proportion of solar radiation usable for photosynthesis.

The actual light use efficiency is calculated as:

where Tε1(x,t) and Tε2(x,t) are stress coefficients of high and low monthly temperatures on light use efficiency; Wε(x,t) is the water stress coefficient; and εmax is the maximum light use efficiency under ideal conditions (gC·MJ−1).

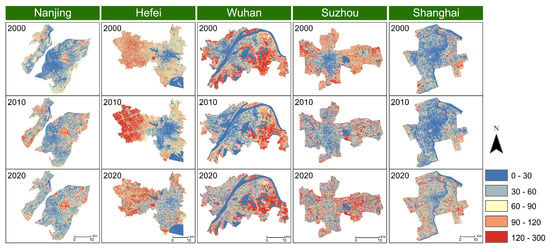

Finally, the NPP results were classified using the natural breaks method, and the spatial distribution of NPP in the central urban areas of the five case cities across three research years was obtained (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

NPP over three years in the central urban areas of five cities.

2.3.3. XGBoost Model Construction and SHAP Interpretation

Dataset preparation

Based on patch-level and class-level blue–green space pattern metrics and their corresponding NPP values for the three research years, six datasets were constructed for each city. Taking 2020 as an example, 20,000 random sampling points were generated using the Random Sampling Tool in ArcGIS 10.7. The values of patch-level metrics and corresponding NPP were extracted for each point. For class-level datasets, in consideration of sampling uniformity and data volume, 40,000 random points were created, and those not located within blue–green spaces were removed. Following this approach, machine learning training datasets were established. Given the strong spatial heterogeneity and scale dependence of urban blue–green space patterns, it was necessary to determine an appropriate moving window size. Using granularity–amplitude analysis, 60 m was identified as the optimal grain size for the study area, and 400 m was selected as the moving window size for calculating landscape metrics.

XGBoost model training

The XGBoost algorithm was employed to construct predictive models. To prevent overfitting, the datasets were regularized, with 80% used as the training set and 20% as the testing set for model validation. Hyperparameters, including n_estimators, max_depth, and learning_rate, were optimized using Bayesian Optimization. Model performance was evaluated using Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and the coefficient of determination (R2). Higher R2 values closer to 1 indicate better model fitting. In addition, ten-fold cross-validation was performed to test the generalization ability of the model and estimate predictive accuracy. The results showed that RMSE and MAE values were relatively small across all six datasets, while R2 values approached 1. Cross-validation further confirmed the robustness of the models, indicating that the constructed XGBoost models achieved the expected level of accuracy in both training and testing sets. Based on the modeling results, key factors influencing carbon sequestration were identified.

SHAP Interpretation

The SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) method, proposed by Lundberg and Lee, enables an accurate interpretation of the contribution of each feature to the prediction outcomes of machine learning models. SHAP provides both global insights into model behavior and local explanations for individual predictions, making it particularly suitable for analyzing the effects of multiple blue–green space pattern metrics on carbon sequestration. Moreover, SHAP integrates well with XGBoost, and the Tree SHAP algorithm can be employed to efficiently estimate SHAP values. The formulation is expressed as follows:

where shap(Xji) denotes the SHAP value of the j-th feature for observation i, representing the marginal contribution of that feature to the prediction.

Assume an XGBoost model with a feature set N (comprising p features) used to predict an output v(N). In the SHAP framework, the contribution of feature i to the model output is denoted as Φi. This contribution is allocated based on the marginal effect of including the feature across all possible subsets of the feature set, as defined by the Shapley value formula:

where p is the total number of features; {x1,⋯ ,xp}∖{xj} represents the set of all possible feature subsets excluding xj; S is one such subset; and val(S∪{xj}) and val(S) denote the model predictions with and without feature xj, respectively.

Through this approach, SHAP quantifies the marginal contribution of each blue–green space pattern indicator to the variation in NPP, thereby offering a robust interpretation of the mechanisms by which spatial configuration influences carbon sequestration capacity.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Feature Importance

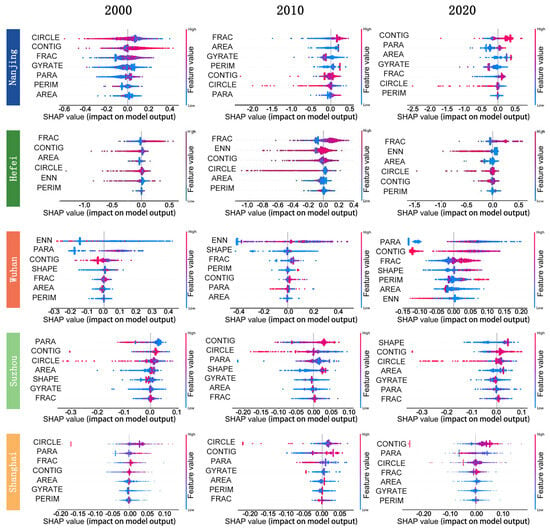

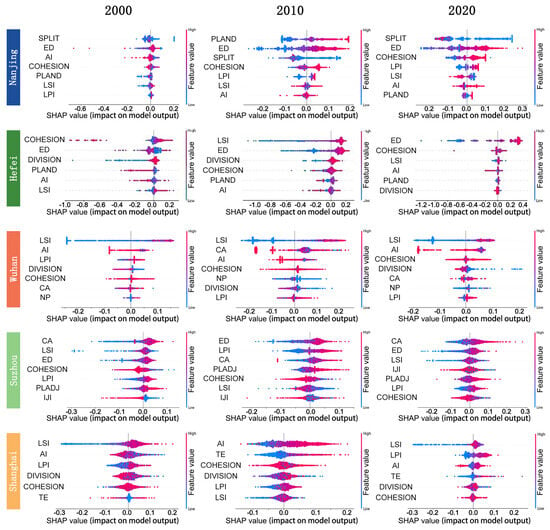

Figure 5 and Figure 6 present the computational and analytical results of the XGBoost and SHAP models at the patch level and class level, respectively. The importance of blue–green spatial configuration features influencing carbon sequestration in each case city is ranked from top to bottom.

Figure 5.

Ranking of feature importance of urban blue–green spatial configuration in patch level.

Figure 6.

Ranking of feature importance of urban blue–green spatial configuration in class level.

Overall, at the patch level, CONTIG, which represents the connectivity of blue–green patches, shows consistently high relevance across all five cities. Indicators reflecting patch shape complexity, such as PARA, FRAC, and CIRCLEC, exhibit high relevance in three and two cities, respectively. Indicators related to connectivity (ENN) and patch area (AREA) are highly relevant in two cities. This suggests that patch shape complexity and connectivity are strongly associated with carbon sequestration across the five cities, while patch area is particularly important in Nanjing and Hefei.

At the class level, shape complexity indicators (ED and LSI) are highly relevant in three and four cities, respectively. Aggregation indicators (SPLIT and AI) show strong correlations with carbon sequestration in Nanjing and Wuhan, whereas area-related indicators (CA and LPI) are more influential in Suzhou and Shanghai. Connectivity (COHESION) demonstrates high relevance only in Hefei. Thus, shape-related indicators exhibit the highest relevance across all five cities, followed by aggregation and area indicators, while connectivity is of notable importance only in Hefei.

In summary, the key indicators affecting carbon sequestration vary among cities. Based on the feature importance ranking across three years in the five cities, indicators that appear among the top three with a frequency of ≥2 are selected as the critical indicators influencing carbon sequestration for each city (Table 4).

Table 4.

Key indicators influencing carbon sequestration.

3.2. Analysis of Key Landscape Metrics

3.2.1. Patch Level

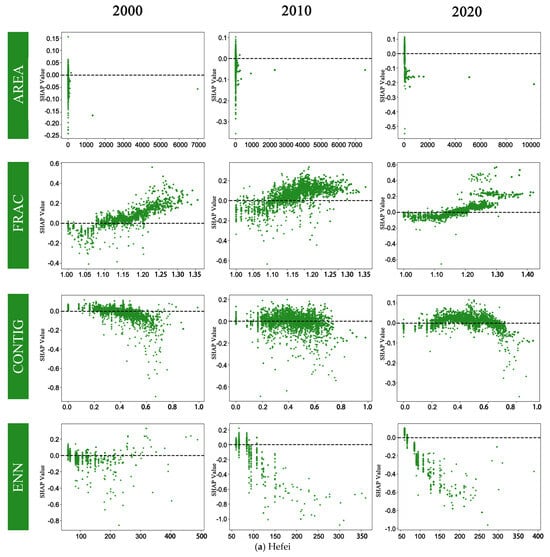

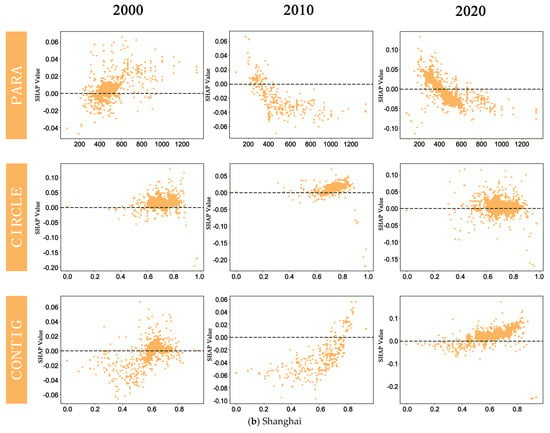

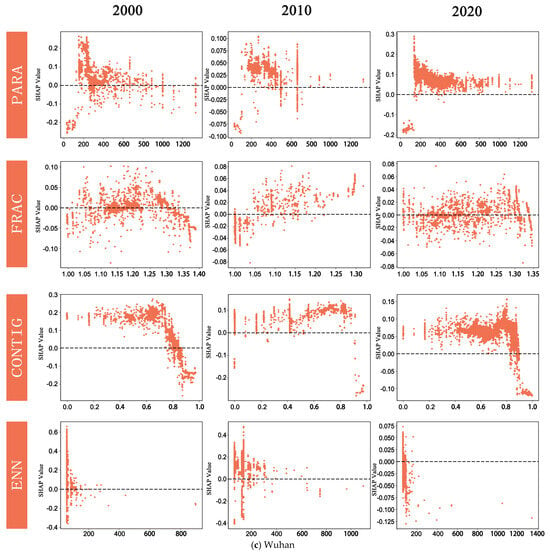

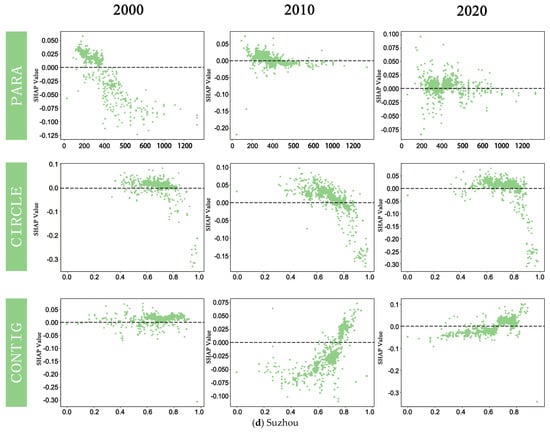

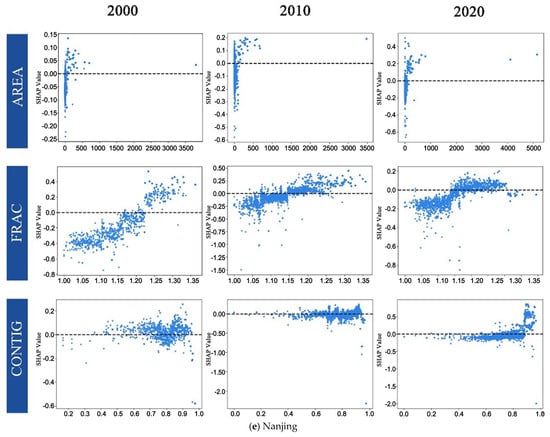

Figure 7 illustrates the one-dimensional dependence relationships between patch-level indicators of blue–green space and NPP across the five cities. Overall, the effects of each indicator on NPP exhibit similar trends across the three years in each city.

Figure 7.

Analysis of key patch-level indicators in the five cities.

Among the key indicators, ENN, representing patch connectivity, shows a negative correlation with NPP in Hefei and Wuhan. Smaller ENN values indicate higher aggregation and lower fragmentation, which are conducive to enhancing carbon sequestration capacity. Fragmentation of blue–green spaces not only weakens ecological linkages among patches and hinders material and energy flows but may also reduce habitat quality, thereby limiting vegetation carbon sequestration [18]. Previous studies have shown that structural changes in blue–green spaces directly affect vegetation growth and carbon fixation capacity. Furthermore, highly aggregated blue–green spaces generally provide stronger microclimate regulation. Research has demonstrated that, given equal total green space, aggregated areas tend to be cooler than fragmented ones, helping alleviate heat stress, promote photosynthesis, and ultimately enhance carbon sequestration [19]. Regarding the relationship between CONTIG and NPP, the five cities exhibit differentiated patterns. Nanjing, Shanghai, and Suzhou generally show positive correlations; in Hefei, SHAP values remain stable within the [0, 0.6] interval but decline when CONTIG increases within [0.6, 1.0]; in Wuhan, SHAP values are stable within [0, 0.8] but decrease beyond 0.8. These findings suggest that CONTIG positively contributes to NPP within a certain range, but excessive values may lead to diminishing marginal effects. Two mechanisms may explain this phenomenon. First, highly continuous blue–green networks mitigate urban heat island effects and reduce respiratory stress on plants. In addition, according to source–sink landscape theory [20], highly connected patches capture and fix atmospheric CO2 more efficiently, thereby enhancing overall carbon sequestration.

AREA, representing patch size, is positively correlated with NPP across all five cities and emerges as a key factor in Nanjing and Hefei. However, when AREA approaches zero, NPP values show high variability. Two potential explanations may account for this pattern. First, differences in shape cause patches with similar areas to exhibit distinct carbon sequestration capacities [13]. In addition, variation in plant species composition and community structure within patches of similar area leads to differences in carbon sequestration [21]. Thus, for small urban patches, improving carbon sequestration should focus on adjusting patch shape and spatial distribution rather than merely expanding area.

FRAC, representing shape complexity, shows a general positive correlation with NPP across the five cities and is a key factor in Nanjing, Hefei, and Wuhan. This indicates that greater patch complexity enhances carbon sequestration. Possible mechanisms include two complementary processes. First, complex shapes promote energy and material exchange with surrounding ecological patches, strengthening ecological functionality. Moreover, higher shape complexity often corresponds to areas with greater natural vegetation cover and lower human disturbance, resulting in more stable ecosystems and stronger carbon sequestrations. However, when FRAC values become excessively high, the growth of NPP tends to plateau, suggesting a possible “threshold effect,” similar to the nonlinear characteristics observed in the cooling effects of blue–green spaces [22]. PARA emerges as a major influencing factor in Suzhou, Shanghai, and Wuhan, where it shows a negative correlation with NPP. This may be attributed to the regularization of patch shapes, which weakens ecological functionality. Previous research has indicated that increased shape regularity reduces landscape connectivity, thereby constraining carbon sequestration [23]. CIRCLE is a key variable in Suzhou and Shanghai. When its values exceed 0.8, SHAP values decline, indicating that linear or irregular patches are more favorable for carbon sequestration than circular ones. Possible explanations include two interrelated mechanisms. First, high circularity often results from intensive human intervention, leading to habitat homogenization and diminished ecosystem services. Moreover, according to the “form–function coupling” theory [24], overly regular geometries hinder the evolution of natural ecological processes, thereby restricting vegetation productivity. In addition, CONTIG demonstrates a significant positive effect on NPP within the [0.6, 1.0] interval, confirming that highly connected patches serve as effective ecological corridors that facilitate genetic flow, enhance vegetation productivity, and strengthen carbon sequestration capacity.

3.2.2. Class Level

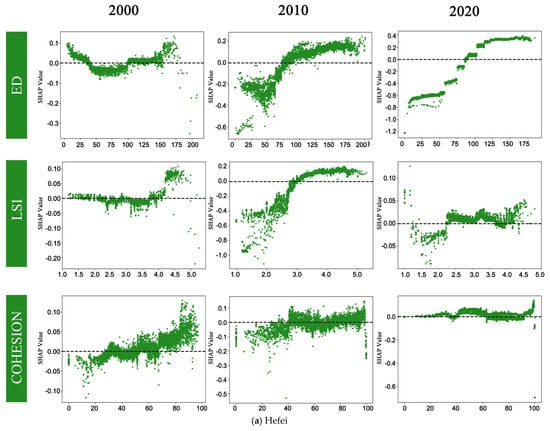

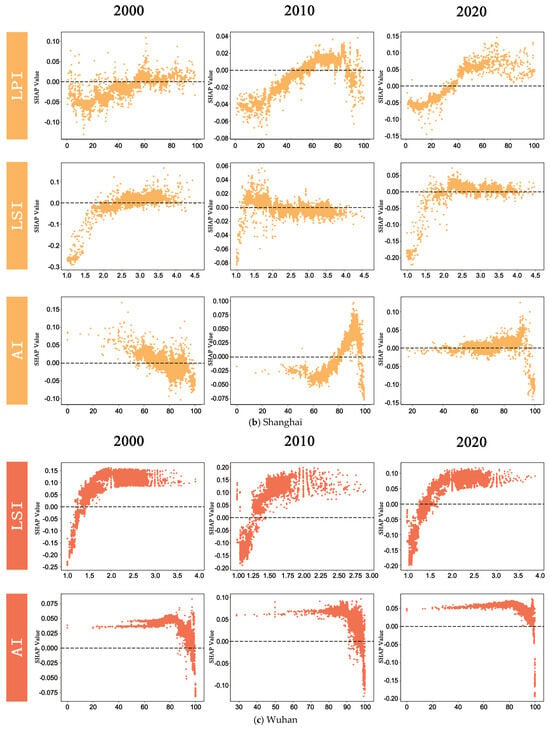

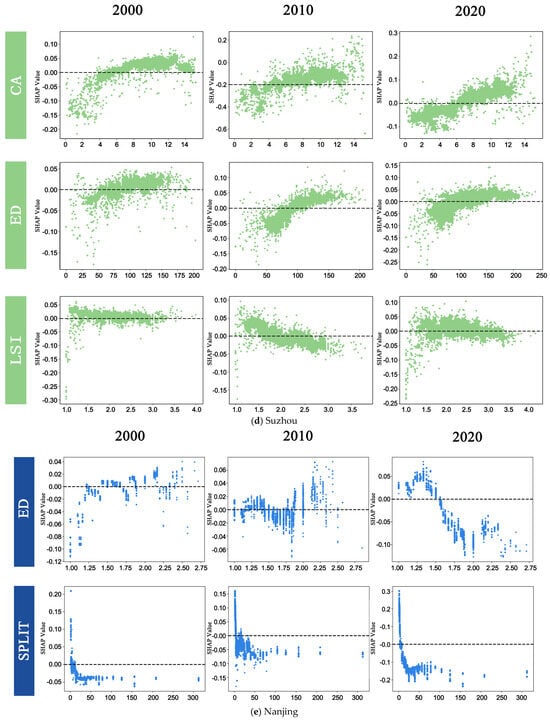

Figure 8 illustrates the one-dimensional dependence relationships between class-level indicators of blue–green spaces and NPP across the five cities. Overall, the effects of each indicator on NPP show consistent trends across the three years in each city.

Figure 8.

Analysis of key class-level indicators in the five cities.

Indicators representing shape complexity, ED and LSI, are generally positively correlated with NPP. However, ED exhibits a pronounced edge effect in three cities, suggesting that excessive shape complexity intensifies edge effects within ecosystems, thereby constraining NPP enhancement. Similar findings were reported by Liao et al. [25], who observed that overly complex shapes reduce aggregation and increase isolation, ultimately diminishing carbon sequestration capacity. LSI demonstrates distinct peaks across different cities and years, such as within the [1.5, 2.0] interval in Wuhan and around 2.0 in Shanghai, followed by a decline or stabilization. Increasing overall shape complexity lengthens the interface between blue–green spaces and surrounding environments, thereby facilitating more frequent exchanges of matter, energy, and information, and expanding the spatial extent of carbon sequestration benefits [26]. Nevertheless, other studies suggest that irregularly shaped blue–green patches may weaken cooling effects, leading to localized temperature increases and indirectly influencing carbon sequestration [26]. Thus, shape complexity enhances carbon sequestration within certain thresholds; beyond these, excessive complexity raises fragmentation and isolation, limiting carbon sequestration. Such thresholds vary across cities depending on their spatial configurations of blue–green spaces.

Aggregation indicators, AI and SPLIT, show distinct patterns. AI serves as a key factor in Wuhan and Shanghai. When AI values range from [0, 80], SHAP values are highest; however, between [80, 100], SHAP values decline. This is partly because high AI values in these ranges correspond to water bodies, which exhibit significantly lower carbon sequestration than green spaces. Moreover, excessively high AI values in vegetated areas may reduce ecosystem diversity, intensify species competition, and suppress NPP [27]. SPLIT is a key indicator in Nanjing and demonstrates a negative relationship with NPP. Within the [0, 30] interval, increasing SPLIT values lead to marked declines in SHAP values, indicating that greater aggregation favors higher carbon sequestration. Andersson et al. also found that landscape fragmentation reduces habitat quality [28]. Higher fragmentation in blue–green spaces diminishes connectivity, disrupts material and energy flows, and ultimately weakens ecosystem productivity.

Area-related indicators, CA and LPI, also show significant associations. CA emerges as a key factor in Suzhou, with a strong positive correlation with NPP. Larger blue–green space areas provide more ecological niches, enhance ecosystem productivity, and thereby increase carbon sequestration. LPI is a key factor in Shanghai, where it is generally positively correlated with NPP, though a decline or stabilization appears in the [80, 100] interval. This suggests that while larger patches promote productivity and carbon sequestration, boundary effects may eventually limit additional gains. Overall, patch area within urban blue–green spaces tends to enhance carbon sequestration but is subject to edge effects.

Connectivity, represented by COHESION, is a key indicator in Hefei and exhibits a clear positive correlation with NPP. SHAP values reach their maximum when COHESION approaches 100, indicating a strong facilitative effect on carbon sequestration. Enhanced connectivity improves the spatial balance of urban blue–green spaces, strengthens cooling effects, and creates favorable growing conditions for vegetation, thereby boosting carbon sequestration. However, edge effects may also occur, as highly connected spaces often correspond to protective greenbelts dominated by monocultures and simplified community structures, which limit carbon sequestration capacity. Thus, within a reasonable range, greater connectivity enhances carbon sequestration benefits.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Analysis of the Effects of Landscape Pattern Metrics on Carbon Sequestration in Five Cities

4.1.1. Commonalities

Building upon our previous study focusing on Nanjing [10], this research expands the analytical framework to five high-density cities located within the same climatic zone. This extension enables a broader comparative perspective and provides a more robust validation of the mechanisms linking blue–green spatial configuration and carbon sequestration efficiency. The results reveal that the relationships between blue–green spatial configuration characteristics and carbon sequestration exhibit consistent patterns across all five cities.

First, both the patch contiguity index (CONTIG) and the proximity index (ENN) showed strong correlations with NPP in all cities, indicating that the spatial aggregation of blue–green patches is a key factor influencing carbon sequestration. CONTIG showed positive correlations with NPP in Nanjing, Shanghai, and Suzhou, while ENN exhibited negative correlations in Hefei and Wuhan. Overall, closer spatial proximity among blue–green patches consistently enhanced carbon sequestration. This result aligns with the conclusions of Qiu et al. [29], who demonstrated that higher vegetation aggregation promotes carbon uptake. The underlying mechanism may relate to how connected blue–green networks reduce landscape fragmentation [30] and optimize the microclimate [19]—for example, by lowering intra-forest temperatures and alleviating heat stress—thus supporting higher photosynthetic efficiency. However, the positive effect of CONTIG may exhibit a threshold response, with mar-ginal gains in carbon sequestration declining once spatial aggregation exceeds a cer-tain level. Excessive connectivity can reduce landscape heterogeneity and limit light penetration within dense vegetation clusters, resulting in self-shading and decreased photosynthetic efficiency in the patch interior [31]. Previous studies have reported similar nonlinear relationships between vegetation connectivity and ecosystem productivity, suggesting that optimal rather than maximal connectivity is required to achieve the highest carbon sequestration efficiency [32].

Second, patch shape complexity metrics, such as FRAC, LSI, and ED, also demonstrated significant effects on carbon sequestration in all five cities. FRAC, which reflects geometric complexity, was positively correlated with NPP, suggesting that enhanced edge effects create more ecological niches and promote biodiversity and ecosystem processes. Similarly, the LSI and ED values, which quantify the tortuosity and density of landscape boundaries, further confirm that moderately complex blue–green morphologies can improve carbon sequestration benefits by expanding edge habitat areas [33]. This finding is consistent with Mngadi et al. [30], who emphasized that reduced fragmentation enhances ecosystem service capacity, highlighting the importance of shape complexity in supporting carbon storage. Furthermore, the results reveal a distinct threshold effect of patch shape complexity indicators (FRAC and ED) on NPP. Specifically, as shape complexity or edge density increases from low to moderate levels, NPP rises correspondingly, likely due to im-proved light penetration, enhanced photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) [34], and the creation of diverse microhabitats that facilitate vegetation growth and regeneration [35]. However, when complexity surpasses a certain threshold, this positive effect dimin-ishes or even reverses. Such threshold effect can be explained by the coupled influences of microclimatic modification and plant physiological responses. Highly irregular and edge-dense patches tend to alter local microclimate conditions, resulting in higher daytime temperatures, greater vapor-pressure deficits, lower humidity, stronger wind exposure, and steeper soil moisture gradients [36,37]. Moderate levels of edge exposure can stimulate photosynthetic activity and growth, but excessive exposure intensifies water stress and triggers stomatal closure, thereby constraining carbon assimilation per unit leaf area [38]. In addition, excessive fragmentation and edge proliferation reduce core hab-itat areas and hinder long-term biomass accumulation. Although productivity near edges may increase in the short term, overall ecosystem carbon storage declines as patch size and core area decrease. This finding aligns with previous empirical studies reporting that moderate fragmentation can enhance local productivity, whereas severe fragmentation ultimately reduces regional carbon stocks [39,40]. Overall, the threshold effects observed for FRAC and ED reflect the balance between the ecological advantages of moderate edge expansion and the physiological and structural constraints imposed by excessive fragmentation, highlighting the importance of maintaining optimal patch complexity to maximize carbon sequestration benefits.

Finally, the patch area metric (AREA) showed a significant positive correlation with NPP across all cities, highlighting the fundamental role of patch size in carbon sequestration. The results suggest that when patch area exceeds a certain threshold, the carbon sequestration efficiency per unit area tends to reach its maximum. This threshold effect may be attributed to the saturation of photosynthetically active vegetation within large patches. As patch size increases, edge effects and microclimat-ic benefits initially enhance growth, but beyond a certain size, internal shading, nutri-ent limitations, and self-thinning processes reduce per-unit-area productivity [39]. This finding is consistent with previous studies on the nonlinear relationship between green space size and carbon absorption [3], underscoring the central importance of large blue–green patches in sustaining urban carbon balance.

4.1.2. Differences

Although the blue–green spatial configuration and carbon sequestration efficiency share common mechanisms across the five cities, their impact pathways and intensities diverge significantly due to urban-specific characteristics. This divergence was quantitatively identified through the XGBoost–SHAP framework, which enabled a fine-grained interpretation of the nonlinear relationships between spatial metrics and NPP across different urban contexts.

First, through SHAP-based interpretation and cross-city comparative analysis, this study identified the nonlinear threshold effects of CONTIG and revealed the contrasting carbon sequestration responses between water-dominated and vegetation-dominated patches, which are often difficult to detect through traditional correlation analyses. In Nanjing, Shanghai, and Suzhou, CONTIG values were consistently positively correlated with NPP, indicating that spatial aggregation of blue–green patches effectively enhanced carbon sequestration. In contrast, Hefei and Wuhan displayed a decline in SHAP values within the higher CONTIG range (0.6–1), suggesting a weakening effect. This divergence may be attributed to the dominance of large water bodies in the spatial configuration of these two cities. In Hefei, Chaohu Lake and Dongpu Reservoir account for a disproportionately high share of the urban core, while Wuhan’s “city of a hundred lakes” landscape alleviates heat island effects but contributes little to carbon sequestration [41]. Consequently, contiguous water-dominated areas contributed less to carbon sequestration despite their high CONTIG values.

Second, the key role of patch area (AREA) exhibited spatial differentiation. AREA was identified as a critical influencing factor only in Nanjing and Hefei, where its positive correlation with NPP was particularly pronounced. Morphological analysis indicates that Nanjing’s green space structure follows a monocentric radiating pattern, while Hefei adopts a dispersed distribution; both rely heavily on large patches to sustain carbon sequestration. In contrast, in polycentric cities such as Shanghai and Suzhou, where blue–green spaces are more evenly distributed, the marginal effect of patch size was relatively diminished. This finding confirms that spatial layout patterns of green spaces exert differentiated impacts on carbon sequestration benefits. This finding, extracted from SHAP-based impact ranking, empirically supports the notion that spatial organization patterns—rather than single indicators—govern carbon regulation efficiency. It thus enriches the theoretical understanding of UBGS functioning across different morphological types.

Moreover, patch shape metrics such as CIRCLE and PARA showed opposite trends in certain cities. In Suzhou and Shanghai, CIRCLE values were negatively correlated with NPP, indicating that linear blue–green corridors (e.g., rivers, green belts) were less efficient in carbon sequestration than near-circular patches. This can be explained by the prevalence of elongated patch shapes caused by dense road and water networks in these cities, underscoring the need for spatial planning to balance functional requirements with geometric complexity. By contrast, in Wuhan, PARA exhibited a negative correlation with NPP, likely reflecting the interaction between patch size and shape. Although elongated patches increase edge effects, the ecological functionality of their core areas may be diminished, thereby weakening overall carbon sequestration capacity. Through cross-city comparison, these findings verify that shape complexity exerts distinct ecological effects under varying spatial morphologies—advancing the multi-city comparative understanding of blue–green spatial mechanisms.

Finally, differences in the responses of aggregation index (AI) and SPLIT highlighted the influence of urban development stages and planning strategies. In Shanghai, AI was positively correlated with NPP, reflecting the city’s efforts to enhance landscape integrity through ecological corridors and wetland conservation [41]. In contrast, Wuhan’s rapid urbanization induced severe landscape fragmentation, resulting in a negative correlation between AI and NPP. This comparison underscores the urgency of protecting and restoring blue–green spaces during urban expansion and demonstrates the potential of planning interventions to regulate carbon sequestration outcomes. Importantly, these differentiated SHAP-derived responses reveal that planning strategies can quantitatively reshape the ecological performance of urban landscapes, offering evidence-based insights for climate-resilient urban design.

In summary, the differentiated characteristics among the five cities reveal that the mechanisms by which blue–green spatial configuration influences carbon sequestration are strongly spatially dependent. Future urban planning should incorporate local baseline conditions and adopt targeted regulation of patch connectivity, morphological complexity, and size distribution to optimize carbon sequestration benefits with precision.

4.2. Implications and Recommendations for Urban Blue–Green Spatial Planning and Management

Based on the commonalities identified in the relationships between blue–green spatial configuration metrics and carbon sequestration in Nanjing, Hefei, Wuhan, Suzhou, and Shanghai, it is evident that connectivity, patch shape complexity, patch size, and spatial distribution patterns play a decisive role in enhancing urban carbon sequestration. To strengthen urban carbon sequestration capacity, optimization should focus on three key aspects. First, improving connectivity and reducing fragmentation is a critical pathway for enhancing carbon sequestration, which requires strengthening the connectivity of green spaces and water bodies in urban planning. Second, increasing the morphological complexity of blue–green patches can expand edge effects, thereby promoting species habitat and ecological processes [13]. Moderate increases in shape complexity, especially in areas undergoing urban expansion, can improve carbon uptake efficiency. Third, urban planning should prioritize the creation and protection of large blue–green patches, particularly those located in urban cores, to support higher levels of carbon sequestration. According to the spatial distribution characteristics and developmental forms of blue–green spaces, planning and management recommendations for the five cities are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Planning and management recommendations for blue–green spaces in the five cities.

4.3. Limitations and Prospects

Due to the limitations of remote sensing data sources, the accuracy of data prior to 2010 is relatively low, which imposes certain constraints on this study. Specifically, the 2000 remote sensing data were obtained from Landsat 5 TM, and the 2010 data from Landsat 7 TM, both with a spatial resolution of 30 m. In contrast, the 2020 data were derived from Landsat 8 OLI, which provides a 15 m resolution for certain bands. Although the datasets from all three years were resampled to 15 m, discrepancies across different sensors may still exist, thereby affecting the accuracy of the results. Moreover, cities located in different climatic zones vary substantially in terms of natural geography, climate conditions, policy trajectories, and socio-economic contexts. Consequently, the formation and development of blue–green spaces, as well as their spatial configurations, differ across regions. The conclusions of this study are therefore primarily applicable to cities in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, while their generalizability to other regions remains to be further validated. Future research could expand to a broader set of case cities in diverse regions, thereby allowing for a more systematic exploration of both the commonalities and differences in blue–green spatial patterns influencing carbon sequestration benefits.

This study primarily examined the impact of blue–green spatial configurations on carbon sequestration efficiency. However, at finer scales, factors such as plant species, tree canopy coverage, and vegetation community structure also play significant roles in carbon sequestration. Building upon the identification of configuration-level determinants, future studies could adopt multi-scale and systemic approaches to further clarify the mechanisms linking urban blue–green spaces and carbon sequestration benefits. Urban blue–green spaces are complex spatial entities, yet existing research has not fully explored whether their three-dimensional structures exert an influence on carbon sequestration. By incorporating three-dimensional morphological attributes and topological spatial networks [43], future research could provide a more comprehensive characterization of urban blue–green morphology, thereby enabling deeper insights into its relationship with carbon sequestration. In addition, this study revealed a potential “threshold effect” between blue–green patch size and carbon sequestration efficiency. However, the precise threshold range and underlying mechanisms require further in-depth investigation.

5. Conclusions

This study employed the XGBoost–SHAP model to investigate the influence of urban blue–green spatial patterns on carbon sequestration, taking five high-density cities in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River—Nanjing, Hefei, Wuhan, Suzhou, and Shanghai—as case studies. The analysis revealed the relationships between blue–green spatial configurations and carbon sequestration. The main conclusions are as follows:

- Blue–green spatial patterns exert significant impacts on carbon sequestration. Across all cities, indicators related to shape complexity, connectivity, area, and distribution patterns showed strong correlations with carbon sequestration efficiency. These dimensions jointly determine the extent to which urban landscapes can store and regulate carbon, emphasizing the structural characteristics of blue–green spaces as key ecological drivers.

- Patch connectivity, shape complexity, and area are the dominant drivers across the five cities. Differences in spatial configurations lead to variations in carbon sequestration benefits. Wuhan and Hefei are characterized by large water bodies, with green spaces concentrated in peripheral zones, resulting in relatively low carbon sequestration capacity in their urban cores. In contrast, Nanjing, Shanghai, and Suzhou are dominated by riverine networks forming point–line–surface structures, coupled with abundant green spaces in central areas, thereby exhibiting relatively higher carbon sequestration capacity.

- City-specific optimization strategies are required to enhance carbon sequestration performance. In Wuhan, where water bodies account for a high proportion of the urban core, efforts should focus on improving the quality of green patches, diversifying vegetation types, and strengthening material and energy flows within ecosystems. Nanjing and Hefei should prioritize the protection of large existing blue–green patches, restrict urban expansion into these areas, and enhance connectivity between patches. In Suzhou and Shanghai, with well-developed road and river networks, strategies should emphasize the integration of linear blue–green spaces and the optimization of patch shapes to avoid excessive fragmentation.

- The methodological framework established in this study, which integrates Blue–green spatial pattern metrics with the XGBoost–SHAP model, demonstrates strong potential for application in diverse international urban contexts. By leveraging the interpretability of SHAP values, this approach effectively reveals the nonlinear mechanisms linking blue–green spatial configuration and carbon sequestration performance. It can be adapted to cities with varying climatic, socioeconomic, and landscape characteristics to assess carbon sequestration dynamics under different development patterns. Although the framework offers high interpretability and flexibility, its application in other regions may require adjustments in data quality, variable selection, and model calibration.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that blue–green spatial configurations significantly affect carbon sequestration benefits. It further explores how spatial patterns regulate carbon sequestration capacity under similar climatic and socioeconomic contexts across five major cities in the middle and lower Yangtze River region. The findings provide scientific evidence for urban planning and management to optimize the allocation of blue–green spaces, thereby improving carbon sequestration, enhancing ecosystem services, and strengthening urban resilience to climate change. Ultimately, this contributes to achieving the goals of low-carbon, green, and sustainable urban development. This study also advances the understanding of urban blue–green systems and their roles in carbon regulation from a multi-city comparative perspective, enriching the theoretical framework of UBGS research. Moreover, the findings offer practical insights for policymakers and planners, providing guidance for optimizing blue–green spatial structures in climate-resilient urban design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S.; methodology, T.S. and S.Y.; software, S.Y., Q.H. and J.M.; validation, S.Y., Q.H. and J.M.; investigation, S.Y., Q.H. and J.M.; resources, S.Y., Q.H. and J.M.; data curation, S.Y., Q.H. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y., Q.H. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, T.S. and Y.Y.; visualization, S.Y., Q.H. and J.M.; supervision, T.S.; project administration, T.S.; funding acquisition, T.S. and Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52278011): The Research on the Tectonic System of Jiangnan Vernacular Architecture based on the Regulation of Water Environment and Southeast University Zhishan Young Scholars Support Program (Grant No. 2242023R40002).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52278011) and Southeast University Zhishan Young Scholars Support Program (Grant No. 2242023R40002). Special thanks to two anonymous reviewers and the editor for their valuable comments to improve our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu, Z.; Yang, G.; Zuo, S.; Jorgensen, G.; Koga, M.; Vejre, H. Critical review on the cooling effect of urban blue-green space: A threshold-size perspective. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, D.; Liu, H.; Zhou, C.; Wang, R. Urban ecological infrastructure: An integrated network for ecosystem services and sustainable urban systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 163, S12–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, P.; Lin, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Ma, C.; Wang, Z.; Dong, X.; Yao, P.; Shao, M. Optimization of Green Spaces in Plain Urban Areas to Enhance Carbon Sequestration. Land 2023, 12, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Wang, K.; Gao, P.; Xu, L. Quantifying the environmental synergistic effect of cooling-air purification-carbon sequestration from urban forest in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 448, 141514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, P.; Zhang, X.; Le, S.; Ren, Y.; Pan, J.; Wang, Y. Enhancing the carbon sequestration potential of urban green space: A water–energy–carbon fluxes perspective. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 104, 128652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiang, Z.; Wang, W.; Chang, W.; Wang, Y. Impacts of strengthened warming by urban heat island on carbon sequestration of urban ecosystems in a subtropical city of China. Urban Ecosyst. 2021, 24, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazy, R.; Hrehorowicz-Gaber, H.; Hrehorowicz-Nowak, A.; Plachta, A. The Synergy of Ecosystems of Blue and Green Infrastructure and Its Services in the Metropolitan Area-Chances and Dangers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, C. Responses of Changes in Green Space Patterns to Carbon Sequestration in Municipal Areas of the Low-Latitude Plateau in Southwestern China: A Case Study of the Kunming Municipal Area. Sustainability 2024, 16, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, M.; Jin, L. An empirical assessment of whether urban green ecological networks have the capacity to store higher levels of carbon. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Tang, S.; Zhang, J.; Guo, W. Quantifying the relationship between urban blue-green landscape spatial pattern and carbon sequestration: A case study of Nanjing’s central city. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Yu, Y.; Liang, S.; Ren, Y.; Liu, M. Effects of urban green spaces landscape pattern on carbon sink among urban ecological function areas at the appropriate scale: A case study in Xi’an. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. Exploring the correlation between waterbodies, green space morphology, and carbon dioxide concentration distributions in an urban waterfront green space: A simulation study based on the carbon cycle. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jia, B.; Li, F.; Ma, J.; Liu, X.; Feng, F.; Liu, H. Effects of multi-scale structure of blue-green space on urban forest carbon density: Beijing, China case study. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 883, 163682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Xu, K.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, F.; Li, L. Prediction and analysis of net ecosystem carbon exchange based on gradient boosting regression and random forest. Appl. Energy 2020, 262, 114566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, X.; Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; Chen, H.; Tan, Z. Nonlinear Cooling Effect of Street Green Space Morphology: Evidence from a Gradient Boosting Decision Tree and Explainable Machine Learning Approach. Land 2022, 11, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, M.; Hartig, F. Machine Learning and Deep Learning—A review for Ecologists. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.05023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, Y. Modeling Urban-Vegetation Aboveground Carbon by Integrating Spectral–Textural Features with Tree Height and Canopy Cover Ratio Using Machine Learning. Forests 2025, 16, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Jim, C.Y.; Wang, H. Assessing the landscape and ecological quality of urban green spaces in a compact city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 121, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estoque, R.C.; Murayama, Y.; Myint, S.W. Effects of landscape composition and pattern on land surface temperature: An urban heat island study in the megacities of Southeast Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 577, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LiDing, C.; BoJie, F.; WenWu, Z. Source-sink landscape theory and its ecological significance. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2006, 26, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Tu, K.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Acerman, A.C.; Guo, N.; et al. Effects of plant community structural characteristics on carbon sequestration in urban green spaces. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Guo, X.; Zeng, Y.; Koga, M.; Vejre, H. Variations in land surface temperature and cooling efficiency of green space in rapid urbanization: The case of Fuzhou city, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wu, W.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Z. Spatiotemporal changes in landscape patterns in karst mountainous regions based on the optimal landscape scale: A case study of Guiyang City in Guizhou Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggett, R.; Perkins, C. Landscape as form, process and meaning. In Unifying Geography; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 224–239. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.; Guldmann, J.-M.; Hu, L.; Cao, Q.; Gan, D.; Li, X. Linking urban park cool island effects to the landscape patterns inside and outside the park: A simultaneous equation modeling approach. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 232, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, M.; Tan, P.Y. Multi-year comparison of the effects of spatial pattern of urban green spaces on urban land surface temperature. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 184, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, G.; Bartolome, J.W.; Gea-Izquierdo, G.; Cañellas, I. Overstory–understory relationships. In Mediterranean Oak Woodland Working Landscapes: Dehesas of Spain and Ranchlands of California; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 145–179. [Google Scholar]

- Janny Ariza-Garzon, M.; Arroyo, J.; Caparrini, A.; Segovia-Vargas, M.-J. Explainability of a Machine Learning Granting Scoring Model in Peer-to-Peer Lending. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 64873–64890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Fang, M.; Yu, Q.; Niu, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, F.; Xu, C.; Ai, M.; Zhang, J. Study of spatialtemporal changes in Chinese forest eco-space and optimization strategies for enhancing carbon sequestration capacity through ecological spatial network theory. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mngadi, M.; Odindi, J.; Mutanga, O.; Sibanda, M. Estimating aboveground net primary productivity of reforested trees in an urban landscape using biophysical variables and remotely sensed data. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearcy, R.W. Responses of plants to heterogeneous light environments. In Functional Plant Ecology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 213–258. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Li, H.; Liu, Z. Synergistic Enhancement of Carbon Sinks and Connectivity: Restoration and Renewal of Ecological Networks in Nanjing, China. Land 2025, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, D. Land use structure optimization and ecological benefit evaluation in Chengdu-Chongqing urban agglomeration based on carbon neutrality. Land 2023, 12, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J.; Fahey, R.; Hardiman, B.; Gough, C. Forest Canopy Structural Complexity and Light Absorption Relationships at the Subcontinental Scale. J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeosci. 2018, 123, 1387–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Martínez-Ramos, M.; Bongers, F.; van der Sande, M.; Poorter, L. Forest structure drives changes in light heterogeneity during tropical secondary forest succession. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 2871–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmeister, J.; Hosek, J.; Brabec, M.; Stralkova, R.; Mylova, P.; Bouda, M.; Pettit, J.L.; Rydval, M.; Svoboda, M. Microclimate edge effect in small fragments of temperate forests in the context of climate change. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 448, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pauw, K.; Depauw, L.; Calders, K.; Caluwaerts, S.; Cousins, S.A.O.; De Lombaerde, E.; Diekmann, M.; Frey, D.; Lenoir, J.; Meeussen, C.; et al. Urban forest microclimates across temperate Europe are shaped by deep edge effects and forest structure. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 341, 109632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, S.; Vico, G.; Katul, G.; Fay, P.A.; Polley, W.; Palmroth, S.; Porporato, A. Optimizing stomatal conductance for maximum carbon gain under water stress: A meta-analysis across plant functional types and climates. Funct. Ecol. 2011, 25, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Shen, C.; Lou, D.; Fu, S.; Guan, D. Ecosystem carbon storage in forest fragments of differing patch size. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Cheng, Y.; Hong, P.; Ma, J.; Yao, L.; Jiang, B.; Xu, X.; Wu, C. Impact of Fragmentation on Carbon Uptake in Subtropical Forest Landscapes in Zhejiang Province, China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Wang, L.; Tao, M.; Huang, C.; Sun, J.; Wang, S. Assessing the ecological balance between supply and demand of blue-green infrastructure. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 288, 112454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, R.; Meadows, M.E.; Sengupta, D.; Xu, D. Changing urban green spaces in Shanghai: Trends, drivers and policy implications. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Wu, W.; Tian, S.; Wang, J. A multi-scale analysis framework of different methods used in establishing ecological networks. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 228, 104579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).