Voxelized Point Cloud and Solid 3D Model Integration to Assess Visual Exposure in Yueya Lake Park, Nanjing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

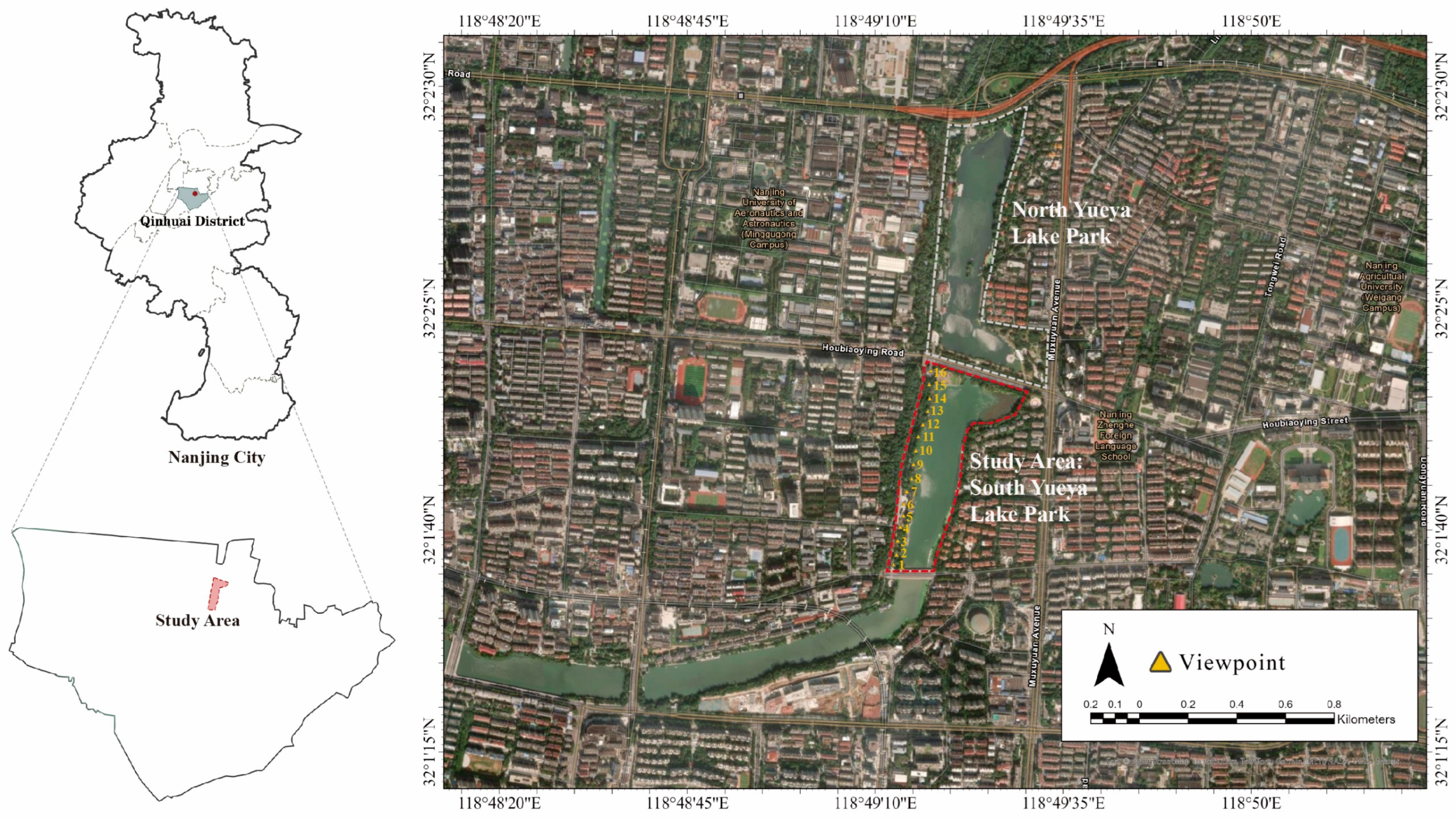

2.1. Study Area and Viewpoint Selection

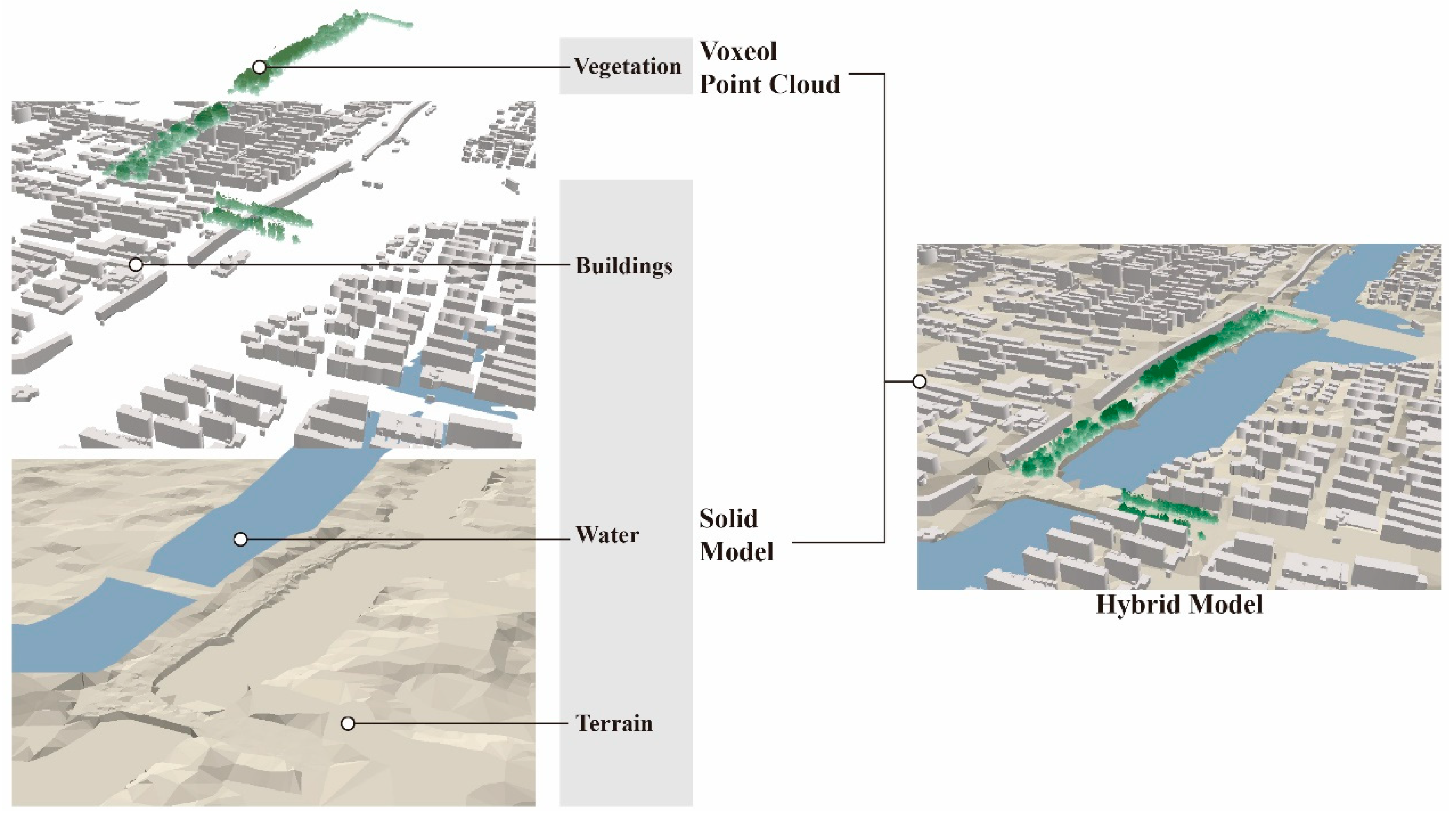

2.2. Urban Hybrid Model Construction

2.3. Hybrid-Model-Based Visibility Analysis

2.4. Visual Exposure Indicators

2.5. Visual Distance

3. Results

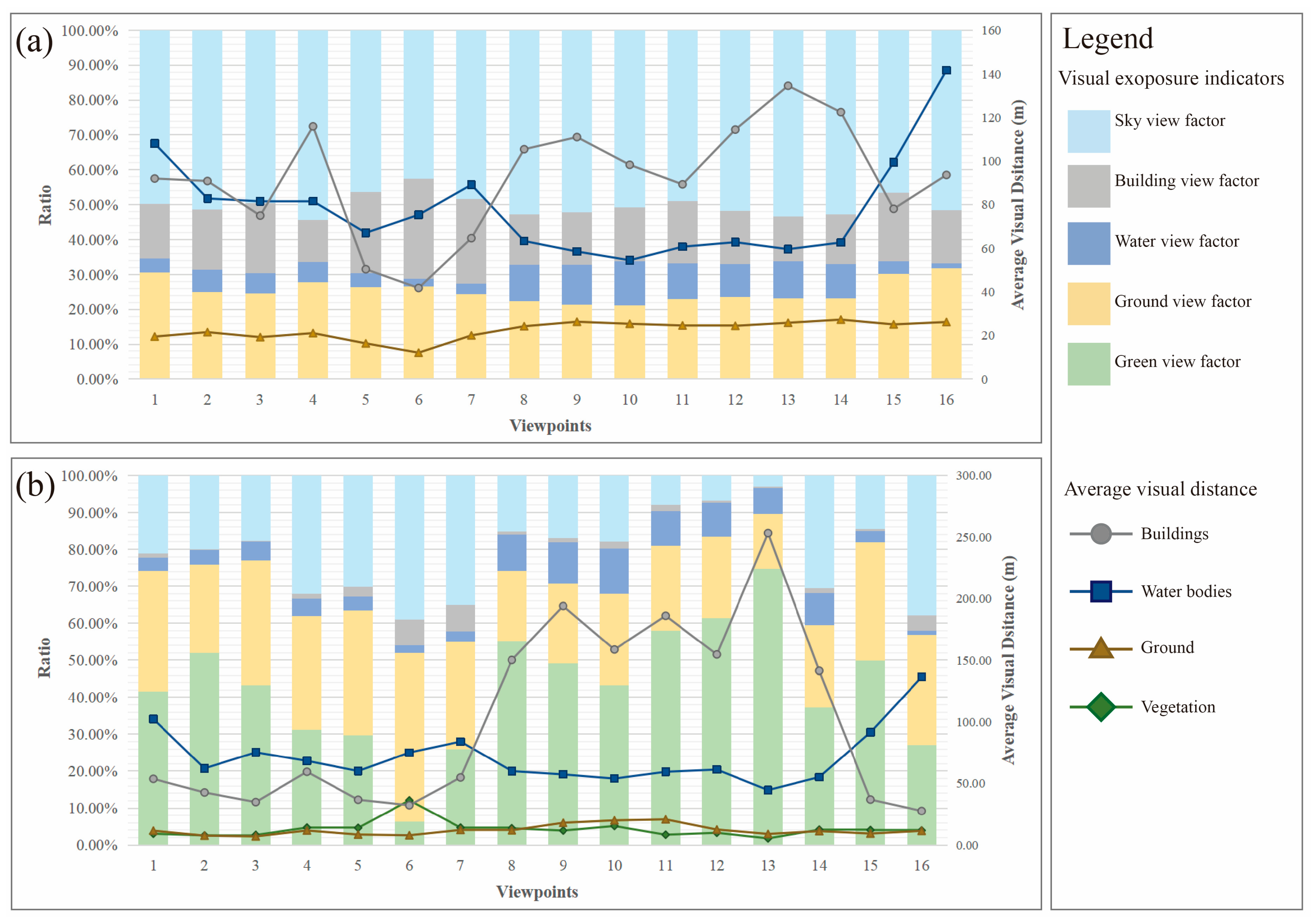

3.1. The Visual Exposure and Visual Distance

3.2. The Comparison Between the Solid and Hybrid Models

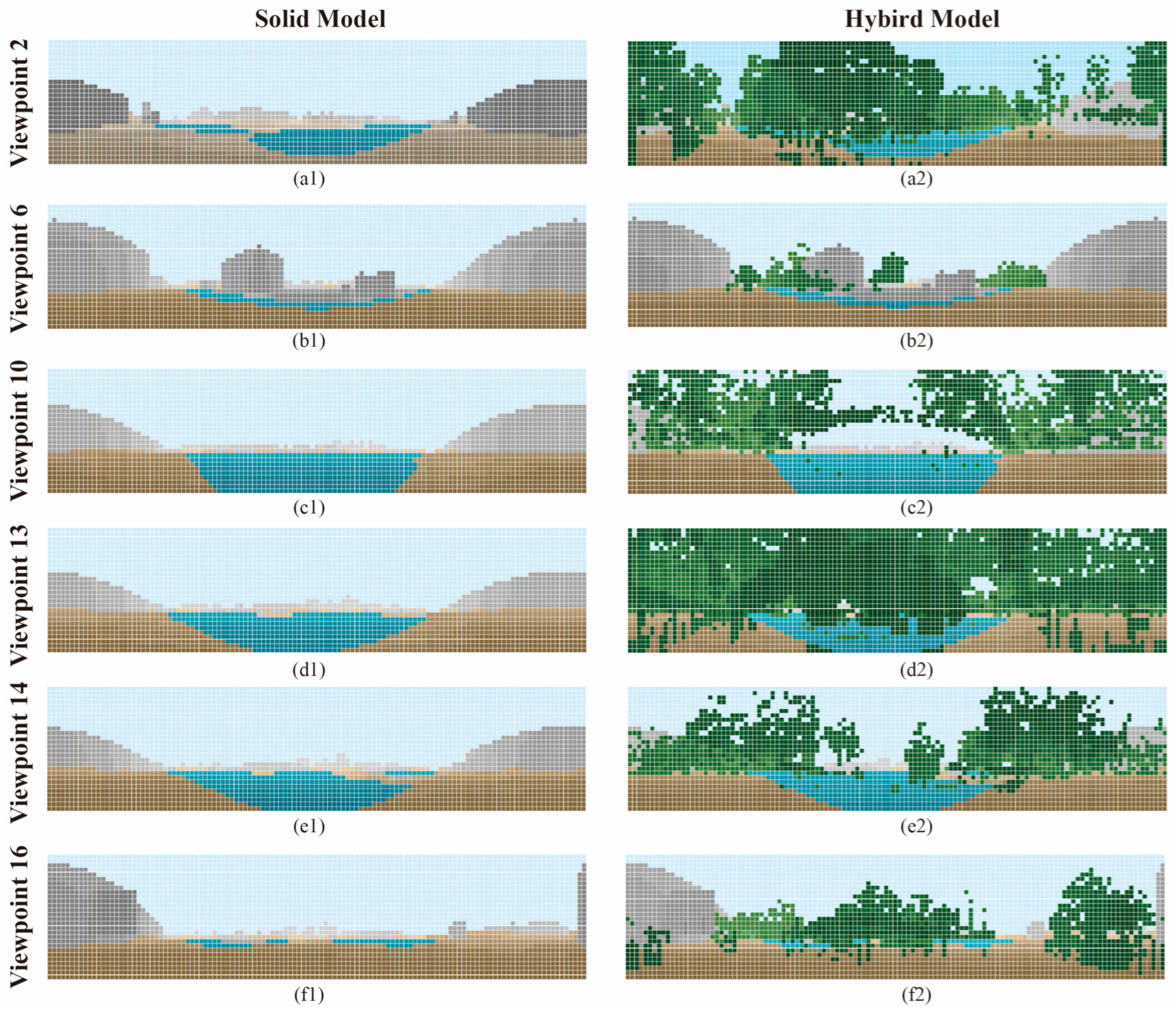

3.3. Typical View Visualization

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of the Proposed Hybrid-Model-Based Visibility Analysis

4.2. The Potential Usage in Sustainable Research

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GVF | Green View Factor |

| SVF | Sky View Factor |

| WVF | Water View Factor |

| BVF | Building View Factor |

| GRDVF | Ground View Factor |

| LoS | Line of Sight |

| DEM | Digital elevation model |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Pseudocode of the LoS Analysis Based on the Hybrid Model

Appendix A.2. The Number of the LoS Rays Ends with Different Landscape Elements Calculated from the LoS Analysis (The Total Number of LoS Rays Is 3388)

| Landscape Elements | Vegetation | Sky | Water | Building | Ground | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Solid | Hybrid | Solid | Hybrid | Solid | Hybrid | Solid | Hybrid | Solid | Hybrid |

| 1 | 0 | 1409 | 1686 | 715 | 136 | 123 | 532 | 238 | 1034 | 903 |

| 2 | 0 | 1761 | 1742 | 674 | 214 | 137 | 585 | 188 | 847 | 628 |

| 3 | 0 | 1467 | 1677 | 599 | 195 | 175 | 684 | 395 | 832 | 752 |

| 4 | 0 | 1057 | 1843 | 1088 | 193 | 160 | 409 | 233 | 943 | 850 |

| 5 | 0 | 1004 | 1573 | 1021 | 133 | 126 | 787 | 383 | 895 | 854 |

| 6 | 0 | 216 | 1444 | 1319 | 70 | 70 | 972 | 892 | 902 | 891 |

| 7 | 0 | 877 | 1636 | 1186 | 102 | 97 | 823 | 504 | 827 | 724 |

| 8 | 0 | 1865 | 1788 | 516 | 350 | 331 | 491 | 73 | 759 | 603 |

| 9 | 0 | 1667 | 1765 | 578 | 390 | 379 | 513 | 78 | 720 | 686 |

| 10 | 0 | 1463 | 1721 | 609 | 422 | 414 | 526 | 192 | 719 | 710 |

| 11 | 0 | 1962 | 1659 | 269 | 341 | 321 | 608 | 119 | 780 | 717 |

| 12 | 0 | 2076 | 1755 | 227 | 319 | 313 | 516 | 41 | 798 | 731 |

| 13 | 0 | 2530 | 1805 | 105 | 361 | 240 | 439 | 10 | 783 | 503 |

| 14 | 0 | 1260 | 1791 | 1037 | 332 | 293 | 479 | 125 | 786 | 673 |

| 15 | 0 | 1689 | 1575 | 493 | 121 | 106 | 671 | 229 | 1021 | 871 |

| 16 | 0 | 914 | 1746 | 1283 | 53 | 42 | 515 | 358 | 1074 | 791 |

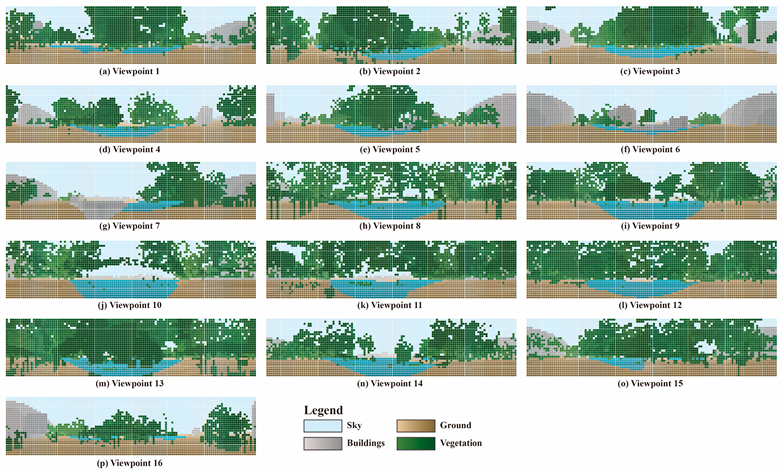

Appendix A.3. Visualizations of the Simulated View from All the Viewpoints

References

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, Q.; Thai, H.M.H. Mapping the character of urban districts: The morphology, land use and visual character of Chinatowns. Cities 2024, 148, 104853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dosen, A.S.; Ostwald, M.J. Evidence for prospect-refuge theory: A meta-analysis of the findings of environmental preference research. City Territ. Archit. 2016, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberger, A.; Schneider, I.E.; Ebenberger, M.; Eder, R.; Venette, R.C.; Snyder, S.A.; Gobster, P.H.; Choi, A.; Cottrell, S. Emerald ash borer impacts on visual preferences for urban forest recreation settings. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Du, J.; Hong, B. Comparative analysis of visual-thermal perceptions and emotional responses in outdoor open spaces: Impacts of look-up vs. look-forward viewing perspectives. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2024, 68, 2373–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo-Santos, J.M.; de Villarán, R.F.; Rapp-Arrarás, Í.; de Provens, E.C.-P. The visual exposure in forest and rural landscapes: An algorithm and a GIS tool. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 101, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llobera, M. Extending GIS-based visual analysis: The concept of visualscapes. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2003, 17, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shach-Pinsly, D.; Fisher-Gewirtzman, D.; Burt, M. Visual Exposure and Visual Openness: An Integrated Approach and Comparative Evaluation. J. Urban Des. 2011, 16, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Quintana, M.; Khomiakov, M.; Yap, W.; Ouyang, J.; Ito, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Biljecki, F. Global Streetscapes—A comprehensive dataset of 10 million street-level images across 688 cities for urban science and analytics. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 215, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Nan, X.; Yang, F.; Bao, Z. Utilizing the green view index to improve the urban street greenery index system: A statistical study using road patterns and vegetation structures as entry points. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 237, 104780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Xie, J.; Furuya, K. Assessing the Preference and Restorative Potential of Urban Park Blue Space. Land 2021, 10, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaeztavakoli, A.; Lak, A.; Yigitcanlar, T. Blue and Green Spaces as Therapeutic Landscapes: Health Effects of Urban Water Canal Areas of Isfahan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhuis, S.; Van Der Hoeven, F. Exploring the Skyline of Rotterdam and The Hague. Visibility Analysis and its Implications for Tall Building Policy. Built Environ. 2018, 43, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzotkiewicz, A.; Pearson, A.L.; Dougherty, B.V.; Shortridge, A.; Wilson, N. Systematic review of the use of Google Street View in health research: Major themes, strengths, weaknesses and possibilities for future research. Health Place 2018, 52, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Cui, H.; Ma, Y.; Gao, N.; Li, X.; Meng, X.; Lin, H.; Abudou, H.; Guo, L.; et al. Green space exposure on depression and anxiety outcomes: A meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, P.Y.; Richards, D. Relative importance of quantitative and qualitative aspects of urban green spaces in promoting health. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 213, 104131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, D.-K.; Brown, R.D.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.-H.; Sung, S. The effect of extremely low sky view factor on land surface temperatures in urban residential areas. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 80, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lu, J.; Guo, R.; Yang, Y. Exploring the Relationship Between Visual Perception of the Urban Riverfront Core Landscape Area and the Vitality of Riverfront Road: A Case Study of Guangzhou. Land 2024, 13, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneshka, M.; Coventry, P.; Cruz, J.; Gilbody, S. Relationship between green and blue spaces with mental and physical health: A systematic review of longitudinal observational studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morello, E.; Ratti, C. A digital image of the city: 3D isovists in Lynch’s urban analysis. Environ. Plan. B 2009, 36, 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Sun, F.; Liu, Y.; Tian, T.; Wu, J.; Dong, Q.; Peng, S.; Che, Y. The influence of the landscape pattern on the urban land surface temperature varies with the ratio of land components: Insights from 2D/3D building/vegetation metrics. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedikt, M.L. To take hold of space: Isovists and isovist fields. Environ. Plan. B 1979, 6, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimburová, Z.; Hedblom, M. Viewshed-based modelling of visual exposure to urban greenery. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 95, 101798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamps, A.E. Isovists, enclosure, and permeability theory. Environ. Plan. B-Plan. Des. 2005, 32, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarge, F.; Mallet, C. Creating large-scale city models from 3D-point clouds: A robust approach with hybrid representation. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2012, 99, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Nijhuis, S.; Agugiaro, G.; Stoter, J.E. Towards a framework for point-cloud-based visual analysis of historic gardens: Jichang Garden as a case study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 91, 128159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, B.; Wu, J.; Shu, S.; Liang, H.; Liu, M.; Badenko, V.; Fedotov, A.; Yao, S.; Yu, B. Mapping 3D visibility in an urban street environment from mobile LiDAR point clouds. GIScience Remote Sens. 2020, 57, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; van Oosterom, P.; Verbree, E. Point Cloud Based Visibility Analysis: First experimental results. In Societal Geo-Innovation: Short Papers, Posters and Poster Abstracts of the 20th AGILE Conference on Geographic Information Science; Bregt, A., et al., Eds.; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.-T.; Verbree, E.; Wang, X.-J. An approach to map visibility in the built environment from airborne LiDAR point clouds. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 44150–44161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; He, J.; Peng, W.; Huang, H.; Chen, C.; Yu, C. Assessing the visibility of urban greenery using MLS LiDAR data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 232, 104662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urech, P.R.W.; Dissegna, M.A.; Girot, C.; Gret-Regamey, A. Point cloud modeling as a bridge between landscape design and planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 203, 103903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI. Extrude Features to 3D Symbology. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/3.2/help/mapping/layer-properties/extrude-features-to-3d-symbology.htm#ESRI_SECTION1_EED3D88DC1DE4BE298EA261CEF8A07F3 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Breaban, A.-I.; Oniga, V.-E.; Chirila, C.; Loghin, A.-M.; Pfeifer, N.; Macovei, M.; Nicuta Precul, A.-M. Proposed Methodology for Accuracy Improvement of LOD1 3D Building Models Created Based on Stereo Pléiades Satellite Imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T. The Visual and Spatial Structure of Landscapes; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Jian, Y. The relationships between 2D and 3D green index altered by spatial attributes at high spatial resolution. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 101, 128540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Zhang, C.R.; Li, W.D.; Ricard, R.; Meng, Q.Y.; Zhang, W.X. Assessing street-level urban greenery using Google Street View and a modified green view index. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Garcia, S.; Merida-Rodriguez, M. Measurement of visual parameters of landscape using projections of photographs in GIS. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2017, 61, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, C.; Qi, J. Seeing and Thinking about Urban Blue–Green Space: Monitoring Public Landscape Preferences Using Bimodal Data. Buildings 2024, 14, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Chen, J.; Middel, A.; Yin, H.; Li, M.; Sun, T.; Zhang, N.; Huang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, K.; et al. Impact of 3-D urban landscape patterns on the outdoor thermal environment: A modelling study with SOLWEIG. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 94, 101773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, S.; de Groot, M.; Boers, J. Eyesores in sight: Quantifying the impact of man-made elements on the scenic beauty of Dutch landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 105, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, X.; Wang, T.; Skidmore, A.K.; Heurich, M. The impact of voxel size, forest type, and understory cover on visibility estimation in forests using terrestrial laser scanning. GISci. Remote Sens. 2021, 58, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Cheng, S. Exploring the Long-Term Changes in Visual Attributes of Urban Green Spaces Using Point Clouds. Land 2024, 13, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, S. Towards Managing Visual Pollution: A 3D Isovist and Voxel Approach to Advertisement Billboard Visual Impact Assessment. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Z.; Darbani, J.M.; Rezaei, A.; Zacharias, J.; Yazdizadeh, A. Comparing text-only and virtual reality discrete choice experiments of neighbourhood choice. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; He, J.; Chen, J.; Larsen, L.; Wang, H. Perceived Green at Speed: A Simulated Driving Experiment Raises New Questions for Attention Restoration Theory and Stress Reduction Theory. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 296–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Liu, C.; Li, J.; Gao, W.; Fukuda, H. Effects of Window Green View Index on Stress Recovery of College Students from Psychological and Physiological Aspects. Buildings 2024, 14, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Abbreviation | Definition | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green View Factor [16,37,38] | GVF | Proportion of green vegetation visible from the pedestrian viewpoint | |

| Sky View Factor [19,24,39] | SVF | Proportion of sky visible in the view from the pedestrian viewpoint | |

| Water View Factor [13,20,40] | WVF | Proportion of large water surfaces (lakes, ponds, rivers) visible within the pedestrian’s field of view | |

| Building View Factor [41] | BVF | Proportion of built structures visible within the field of view | |

| Ground View Factor | GRDVF | Proportion of ground surface visible within the pedestrian field of view |

| View-Point | GVI (%) | SVF (%) | WVF (%) | BVF (%) | GRDVF (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | H | H-S | S | H | H-S | S | H | H-S | S | H | H-S | S | H | H-S | |

| 1 | 0 | 41.59 | 41.59 | 49.76 | 21.10 | −28.66 | 4.01 | 3.63 | −0.38 | 15.70 | 1.09 | −14.61 | 30.53 | 32.59 | 2.06 |

| 2 | 0 | 51.98 | 51.98 | 51.42 | 19.89 | −31.53 | 6.32 | 4.04 | −2.28 | 17.27 | 0.21 | −17.06 | 24.99 | 23.88 | −1.11 |

| 3 | 0 | 43.30 | 43.30 | 49.50 | 17.68 | −31.82 | 5.76 | 5.17 | −0.59 | 20.19 | 0.15 | −20.04 | 24.55 | 33.70 | 9.15 |

| 4 | 0 | 31.20 | 31.20 | 54.40 | 32.11 | −22.29 | 5.70 | 4.72 | −0.98 | 12.07 | 1.24 | −10.83 | 27.83 | 30.73 | 2.90 |

| 5 | 0 | 29.63 | 29.63 | 46.43 | 30.14 | −16.29 | 3.93 | 3.72 | −0.21 | 23.23 | 2.69 | −20.54 | 26.41 | 33.82 | 7.41 |

| 6 | 0 | 6.38 | 6.38 | 42.62 | 38.93 | −3.69 | 2.07 | 2.07 | 0.00 | 28.69 | 7.02 | −21.67 | 26.62 | 45.60 | 18.98 |

| 7 | 0 | 25.89 | 25.89 | 48.29 | 35.01 | −13.28 | 3.01 | 2.86 | −0.15 | 24.29 | 7.17 | −17.12 | 24.41 | 29.07 | 4.66 |

| 8 | 0 | 55.05 | 55.05 | 52.77 | 15.23 | −37.54 | 10.33 | 9.77 | −0.56 | 14.49 | 0.80 | −13.69 | 22.41 | 19.15 | −3.26 |

| 9 | 0 | 49.20 | 49.20 | 52.10 | 17.06 | −35.04 | 11.51 | 11.19 | −0.32 | 15.14 | 0.97 | −14.17 | 21.25 | 21.58 | 0.33 |

| 10 | 0 | 43.18 | 43.18 | 50.80 | 17.98 | −32.82 | 12.46 | 12.22 | −0.24 | 15.52 | 1.89 | −13.63 | 21.22 | 24.73 | 3.51 |

| 11 | 0 | 57.91 | 57.91 | 48.97 | 7.94 | −41.03 | 10.06 | 9.47 | −0.59 | 17.94 | 1.65 | −16.29 | 23.03 | 23.03 | 0.00 |

| 12 | 0 | 61.28 | 61.28 | 51.80 | 6.70 | −45.10 | 9.42 | 9.24 | −0.18 | 15.23 | 0.59 | −14.64 | 23.55 | 22.19 | −1.36 |

| 13 | 0 | 74.68 | 74.68 | 53.28 | 3.10 | −50.18 | 10.66 | 7.08 | −3.58 | 12.95 | 0.27 | −12.68 | 23.11 | 14.87 | −8.24 |

| 14 | 0 | 37.19 | 37.19 | 52.86 | 30.61 | −22.25 | 9.80 | 8.65 | −1.15 | 14.14 | 1.27 | −12.87 | 23.20 | 22.28 | −0.92 |

| 15 | 0 | 49.85 | 49.85 | 46.49 | 14.55 | −31.94 | 3.57 | 3.13 | −0.44 | 19.80 | 0.50 | −19.30 | 30.14 | 31.97 | 1.83 |

| 16 | 0 | 26.98 | 26.98 | 51.53 | 37.87 | −13.66 | 1.56 | 1.24 | −0.32 | 15.20 | 4.10 | −11.10 | 31.71 | 29.81 | −1.90 |

| Mean | 0 | 42.83 | 42.83 | 50.19 | 21.62 | −28.57 | 6.89 | 6.14 | −0.75 | 17.62 | 1.98 | −15.64 | 25.31 | 27.44 | 2.13 |

| SD = Standard Deviation | 0 | 0.166 | 0.166 | 0.031 | 0.113 | 0.126 | 0.037 | 0.035 | 0.009 | 0.045 | 0.022 | 0.034 | 0.033 | 0.074 | 0.061 |

| Landscape Elements | Vegetation | Water Body | Building | Ground | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viewpoint | S | H | H-S | S | H | H-S | S | H | H-S | S | H | H-S |

| 1 | 0 | 9.143 | 9.143 | 108.067 | 102.416 | −5.650 | 92.003 | 53.772 | −38.231 | 19.507 | 11.636 | −7.870 |

| 2 | 0 | 7.765 | 7.765 | 82.849 | 62.269 | −20.580 | 90.855 | 42.709 | −48.147 | 21.543 | 7.599 | −13.944 |

| 3 | 0 | 8.154 | 8.154 | 81.557 | 75.297 | −6.260 | 74.998 | 34.901 | −40.097 | 19.240 | 6.989 | −12.251 |

| 4 | 0 | 14.139 | 14.139 | 81.601 | 68.414 | −13.187 | 115.925 | 59.500 | −56.425 | 21.099 | 11.753 | −9.347 |

| 5 | 0 | 13.908 | 13.908 | 67.085 | 60.115 | −6.970 | 50.400 | 36.809 | −13.591 | 16.375 | 8.472 | −7.903 |

| 6 | 0 | 36.328 | 36.328 | 75.365 | 75.128 | −0.236 | 41.783 | 32.326 | −9.457 | 12.101 | 7.885 | −4.216 |

| 7 | 0 | 14.099 | 14.099 | 89.160 | 84.039 | −5.121 | 64.644 | 54.881 | −9.763 | 20.034 | 12.237 | −7.797 |

| 8 | 0 | 13.569 | 13.569 | 63.352 | 60.045 | −3.307 | 105.436 | 150.098 | 44.662 | 24.241 | 11.944 | −12.298 |

| 9 | 0 | 11.687 | 11.687 | 58.517 | 57.359 | −1.157 | 111.028 | 193.956 | 82.929 | 26.306 | 18.046 | −8.260 |

| 10 | 0 | 15.410 | 15.410 | 54.529 | 53.956 | −0.573 | 98.290 | 158.587 | 60.297 | 25.369 | 20.014 | −5.355 |

| 11 | 0 | 8.332 | 8.332 | 60.723 | 59.480 | −1.243 | 89.332 | 186.015 | 96.683 | 24.589 | 20.818 | −3.771 |

| 12 | 0 | 9.901 | 9.901 | 62.804 | 61.272 | −1.532 | 114.454 | 154.583 | 40.130 | 24.431 | 12.534 | −11.897 |

| 13 | 0 | 5.372 | 5.372 | 59.597 | 44.637 | −14.961 | 134.556 | 253.105 | 118.550 | 25.837 | 8.982 | −16.855 |

| 14 | 0 | 12.447 | 12.447 | 62.655 | 55.225 | −7.430 | 122.439 | 141.436 | 18.997 | 27.289 | 11.263 | −16.027 |

| 15 | 0 | 12.143 | 12.143 | 99.429 | 91.567 | −7.862 | 78.099 | 36.958 | −41.141 | 25.084 | 9.280 | −15.804 |

| 16 | 0 | 11.804 | 11.804 | 141.639 | 136.563 | −5.077 | 93.650 | 27.673 | −65.977 | 26.185 | 11.475 | −14.711 |

| Mean | 0 | 12.763 | 12.763 | 78.058 | 71.736 | −6.322 | 92.368 | 101.082 | 8.714 | 22.452 | 11.933 | −10.519 |

| SD = Standard Deviation | 0 | 6.891 | 6.891 | 23.038 | 22.912 | 5.699 | 25.675 | 73.665 | 58.681 | 4.182 | 4.244 | 4.285 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, G.; Yang, D.; Cheng, S. Voxelized Point Cloud and Solid 3D Model Integration to Assess Visual Exposure in Yueya Lake Park, Nanjing. Land 2025, 14, 2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102095

Zhang G, Yang D, Cheng S. Voxelized Point Cloud and Solid 3D Model Integration to Assess Visual Exposure in Yueya Lake Park, Nanjing. Land. 2025; 14(10):2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102095

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Guanting, Dongxu Yang, and Shi Cheng. 2025. "Voxelized Point Cloud and Solid 3D Model Integration to Assess Visual Exposure in Yueya Lake Park, Nanjing" Land 14, no. 10: 2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102095

APA StyleZhang, G., Yang, D., & Cheng, S. (2025). Voxelized Point Cloud and Solid 3D Model Integration to Assess Visual Exposure in Yueya Lake Park, Nanjing. Land, 14(10), 2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102095