Abstract

Meteorological droughts have been occurring with greater frequency and intensity, impacting water security in various regions. Between 2013 and 2015, the Paraopeba River Basin in southeast Brazil experienced its most severe drought in the last 70 years, resulting in low levels in the Paraopeba system reservoirs, which supplies 53% of the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte, the third largest metropolitan area in Brazil. This study evaluated the climate models’ performance from the NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 through drought indices projections, specifically the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) and Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI). The results showed that seven climate models can represent the current climate in the basin. For the drought’s projection, the indices were used in two time scales (six and twelve months) for both the current climate and two future scenarios (SSP245 and SSP585). Our results highlight the intensification of droughts throughout the twenty-first century, with greater intensification in the SSP585 scenario. The SPEI indicated trends towards drier conditions, particularly under the SSP585 scenario and on the twelve-month timescale. These findings demonstrate the relevance of climate change and drought indices on the projections, supporting public policies for mitigation and adaptation, especially in strategic regions for water supply and hydro-electric generation.

1. Introduction

Droughts are defined by a reduction in precipitation in relation to normal climatological patterns for a given region and period. While droughts are natural phenomena, they have been intensified by the effects of climate change [1,2]. This occurs because the increase in temperature at the earth’s surface has caused significant changes in the hydrological cycle, resulting in an increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events [3,4].

Between 2013 and 2015, the Minas Gerais state faced its worst drought in 70 years [5]. The Paraopeba River Basin, for example, showed reduced reservoir levels, reaching 28.7%, 20.4%, and 5.2% of the total capacity of the Rio Manso, Serra Azul, and Vargem das Flores reservoirs, respectively [6,7]. These reservoirs supply approximately 53% of the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte, which is approximately three million people [8,9].

Identifying droughts is challenging due to the complexity involved in measuring their intensity, duration, and magnitude [10,11]. Droughts are commonly classified as meteorological, agronomic, hydrological, or socioeconomic, depending on their predominant impacts and temporal characteristics [12,13]. The accurate timing, identification, monitoring, and prediction of these events is essential for effective mitigation strategies and adaptation to resource scarcity [14,15].

Drought indices are widely used tools that aim to quantify the severity, duration, and extent of drought in different climate regimes [3,12,16,17]. The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) [18] and the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) [19] are examples of these tools that are widely applied in drought studies. The SPI is calculated by fitting a Probability Distribution Function (PDF) to a precipitation time-series. This enables the identification of dry and wet periods across various timescales [20]. Similarly, the SPEI incorporates both precipitation and evapotranspiration, as it calculates a water balance, which variation is also described by a PDF. This allows for the assessment of temperature impacts, providing a more robust index [11,21].

In the context of climate change, Global Climate Models (GCMs) serve as essential tools for representing the physical and chemical characteristics of the atmosphere, boosted by anthropogenic activities [22,23,24]. Because climate events are interconnected on a global scale, modeling the atmosphere remains challenging due to uncertainties related to climate variability and local topography [13,25]. Thus, the NASA-Earth Exchange Global Daily Downscaled Projections (NEX-GGDP-CMIP6) climate model, developed from the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project, incorporates bias correction and spatial disaggregation to account for the impacts of local topography on the climate. This database is a valuable resource for projecting drought conditions, especially in strategic regions for water supply and hydroelectric energy generation, such as in the Paraopeba River Basin.

The objective of this study is to assess meteorological drought projection in the Paraopeba River Basin. To achieve this goal, the performance of CMIP6 models was assessed for the current scenario by comparing observations against model precipitation estimations. Then, drought projections were evaluated using the SPI and SPEI for the current climate, SSP245, and SSP585 emission scenarios at six- and twelve-month timescales and for the future period (2040 to 2100).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Description

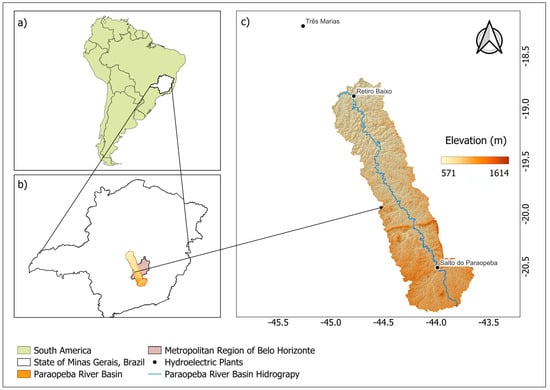

The Paraopeba River Basin, a sub-basin within the São Francisco River Basin, encompasses an area of 12,500 km2, situated between latitudes −44.92 and −43.68 and longitudes −20.93 and −18.71 (see Figure 1). The region features diverse topography, with elevations ranging from 571 m to 1614 m. The geological composition includes rocks from the Crystalline Complex, ferruginous formations of the Minas Group, and various sedimentary deposits, as well as fault systems that impact groundwater hydrology [7,8]. Average annual precipitation across the basin ranges from 1120.1 mm to 1550.7 mm.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the Minas Gerais state in South America (a), Paraopeba River Basin location in the Minas Gerais state (b), and Paraopeba River Basin digital elevation model and hydropower plants (c).

The Paraopeba hydrological system is a key source of water supply for the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte, which is the third largest in Brazil. The economic activities within the basin include mining, industrial operations such as steel, textile, food, automotive, and petrochemical manufacturing, urban centers, and hydroelectric plants, including Salto do Paraopeba (2.45 MW) and Retiro Baixo (82.0 MW). Consequently, intensified droughts in this region can result in considerable economic losses that affect irrigation, agricultural production, power generation, water supply, and navigation.

2.2. Climate Change Projections Database

The climate change projections were obtained from the NASA Earth Exchange Global Daily Downscaled Projections (NEX-GDDP-CMIP6), which provides high-resolution scenarios based on CMIP6 models [26]. This dataset uses bias correction, i.e., a spatial disaggregation method, and applies spatial disaggregation using the global meteorological forcing dataset, integrating local topography effects on precipitation [26,27,28].

Seventeen climate models from the NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 [29] were used in this study. These models supplied meteorological data for the control period, defined as the current climate from 1950 to 2014, during which greenhouse gas concentrations remain unchanged. Additionally, the models offer data for four of the five Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenarios—SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, and SSP585—for the years 2015 to 2100. Each scenario aligns projected radiative forcing by the end of the century with trends in socioeconomic, demographic, technological, political, and institutional factors [30,31].

This study examines two scenarios derived from CMIP6: SSP245, categorized as an intermediate pathway, and SSP585, representing the most pessimistic scenario. SSP245 reflects moderate efforts to reduce fossil fuel consumption; however, these reductions are insufficient, leading to its classification as a trend scenario. In contrast, SSP585 assumes persistent high dependence on fossil fuels, meaning that the global average surface temperature may increase between 3.3 °C and 5.7 °C above the pre-industrial period.

In addition, this study analyzed the future period from 2040 to 2100, subdivided into three time slices: 2040–2060 (near future), 2061–2080 (mid-future), and 2081–2100 (end of the century). This analysis extended to the SSP245 and SSP585 emissions scenarios using drought indices (SPI and SPEI).

2.3. Current Scenario

Seventeen climate models (NEX-GGDP-CMIP6) were assessed for the period from 1992 to 2014. The performance of the models with respect to observed precipitation was evaluated using statistical metrics. The Brazilian Daily Weather Gridded Data (BR-DWGD) [32] serves as the observational dataset, incorporating data from 11473 rain gauges and 1252 weather stations, which were interpolated by inverse and angular distance weighting. These observed datasets were compared to precipitation outputs from climate models. For validation, drought indices calculated from climate models (NEX-GGDP-CMIP6) were compared with those obtained from BR-DWGD datasets using correlation coefficients (r).

2.4. Climate Model Performance

The performance of the climate models (NEX-GDDP-CMIP6) was carried out considering the simulated precipitation data, as the Global Circulation Models account for an additional uncertainty regarding precipitation projections [22,24,33]. The performance of the climate models in relation to the observed precipitation data (BR-DWGD) was verified by statistical metrics (, , RMSE, and RMSEbias) that also allowed the analysis of the index [2]. In this index, three criteria are evaluated:

- 1.

- ;

- 2.

- ;

- 3.

Therefore, if the three criteria are fulfilled, the index of can be calculated by Equation (1).

where is the standard deviation of the simulated data, is the standard deviation of the observed data, is the Root Mean Squared Error, and is the Mean Square Error after the removal of a constant bias.

If index < 2, the model is adequate [34]. Therefore, the lowest value of the index indicates better simulations. Based on this index, the best GCM that performs satisfactorily in the Paraopeba River Basin can be identified. The index was satisfactorily applied in the study conducted by [31], which evaluated temperature and precipitation simulations for Brazil using CMIP6 data.

Finally, it used the correlation (CORR) that evaluates the performance of the simulated data (ensemble) against the observed data in the following database: Brazilian Daily Weather Gridded Data (BR-DWGD) [32]. For this assessment, the thresholds established by [35] were adopted, as is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlation thresholds established by [35].

2.5. Drought Indices: Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) and Standardized Precipitation and Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI)

Precipitation data are required to calculate the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) index. The Standardized Precipitation and Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), on the other hand, requires temperature data in addition to precipitation. For the study area, these datasets were obtained from the best NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 models.

The Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) is a metric used to evaluate wet and dry periods across multiple timescales, based exclusively on precipitation data. Its calculation involves fitting historical precipitation records to a PDF, typically a gamma distribution. Subsequently, transforming the resulting probabilities via the inverse standard Gaussian distribution to obtain “z” values that represent the SPI. The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), as developed by [10], incorporates not only precipitation but also potential evapotranspiration within an atmospheric water balance framework (P – ET). For estimating potential evapotranspiration, it is recommended to employ a method that utilizes mean monthly temperature data [36].

In the study, both SPI and SPEI analyses were performed using the SPEI package in the RStudio software (version 1.1.456). Is it important to highlight that the package uses default log-logistic distribution for the SPEI [37] and Gamma distribution for the SPI [38]. However, the parameter distribution can be modified by the user. The SPI and SPEI can be calculated across various timescales; in this study two temporal scales, six and twelve months, were used (SPI-6, SPI-12, SPEI-6, and SPEI-12). For drought characterization, negative values correspond to drought conditions, while positive values indicate wet conditions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification of drought occurrence.

3. Results

3.1. Climate Model Performances and Drought for the Current Scenario

The initial step involved assessing the GCM simulations using the selected performance statistics. In this context, seven models with the lowest values were selected: ACCESS-ESM1-5, TaiESM1, CMCC-ESM2, MPI-ESM1-2-LR-1, NorESM2-MM, MRI-ESM2, and CanESM5, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Monthly precipitation simulated by the climate models analyzed in the period from 1992 to 2014 (current scenario).

Based on these precision statistics, these seven models are adequate to promote SPI and SPEI projections in the Paraopeba River Basin. The ACCESS-ESM1-5 model showed the lowest index and the best precipitation simulation results (Table 3). These climate models are also aligned with the results of [39], as four of them are ranked in the Top 10 CMIP6 for representing South America’s climate. Additionally, Ref. [31] found that climate models (CMIP6) accurately fit the climate of the Minas Gerais state, the region where the Paraopeba River Basin is located.

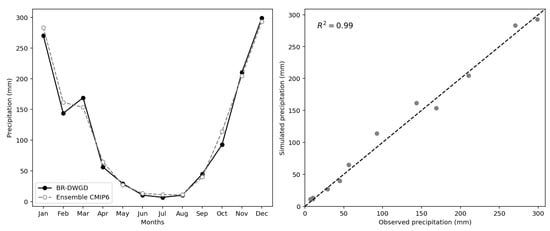

Regarding the mean ensemble of the seven climate models’ selected performance, there is a strong correlation between them (CORR = 0.99) (Figure 2). Thus, the mean ensemble of the selected models of the NEX-GGDP-CMIP6 collection showed good performance when compared to the observed data (BR-DWGD). The results are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mean monthly precipitation of the seven GCMs (ensemble) and the observed data from the BR-DWGD in the current scenario.

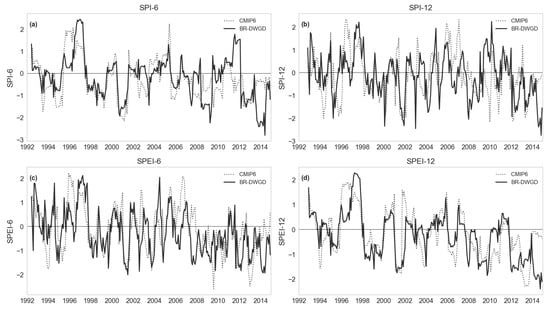

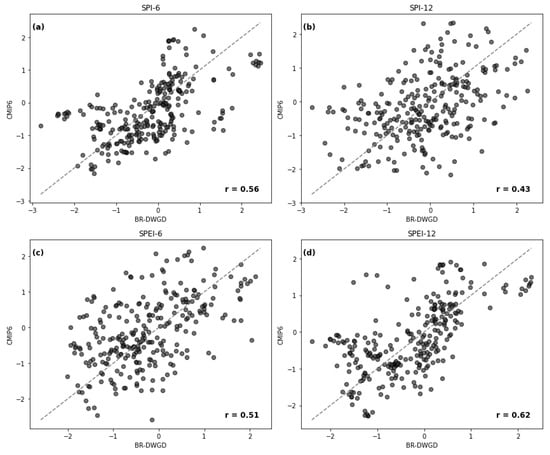

Figure 3 and Figure 4 present SPI and SPEI calculations derived from an ensemble of seven climate models (NEX-GDDP-CMIP6) and observed data sourced from the BR-DWGD database under the current scenario. Figure 3a–d) demonstrates that simulated data corresponds with observed data for both drought indices across the two time scales. Similar patterns appear in Figure 4a–d, with correlation coefficients between 0.43 and 0.56. Differences are more apparent and sporadic in SPI-6, SPI-12, and SPEI-6. The index’s magnitude increases notably for SPEI-12 (Figure 3d and Figure 4d).

Figure 3.

Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) and Standardized Precipitation and Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) estimated by the ensemble climate model and with observed climate data for the Paraopeba River Basin. (a) SPI-6—six months; (b) SPI-12—twelve months; (c) SPEI-6—six months; and (d) SPEI-12—twelve months.

Figure 4.

Scatter plots comparing SPI and SPEI values derived from the ensemble climate models (NEX-GDDP-CMIP6) versus BR-DWGD, for the period 1992 to 2014 and for different timescales. (a) SPI-6—six months; (b) SPI-12—twelve months; (c) SPEI-6—six months; (d) SPEI-12—twelve months.

The datasets show agreement (Figure 3a–d), indicating that the ensemble of climate models can be applied to monitor meteorological drought projections. These findings align with those of [40], who highlighted that variations among datasets may result from various sources of uncertainty, such as meteorological data interpolation, spatial resolution effects, and station data gaps—factors that can influence the fitted statistical distribution, particularly at its extremes.

3.2. SPI and SPEI Projections

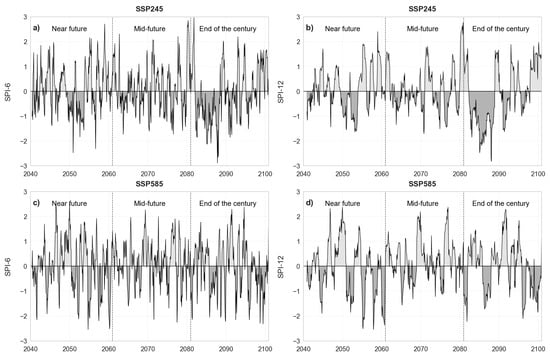

The SPI, in the SSP245 scenario presents alternating periods of rain and drought, with most dry periods classified as abnormally dry and severe drought (Figure 5a,b). For the period from 2080 to 2090, droughts have become more frequent and severe, with extreme droughts being observed.

Figure 5.

Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) projected over the 21st century for the Paraopeba River Basin: (a) scenario SSP245—six months; (b) scenario SSP245—twelve months; (c) scenario SSP585—six months; and (d) scenario SSP585—twelve months.

Under the SSP585 scenario, there is notable interannual variability across all cases, along with a trend indicating increased frequency and intensity of drought events, particularly toward the end of the century (SPI < −2). The SPI-12 scenario indicates more extended and clearly defined droughts compared to the SPI-6, suggesting longer-lasting impacts on drought conditions (Figure 5c,d).

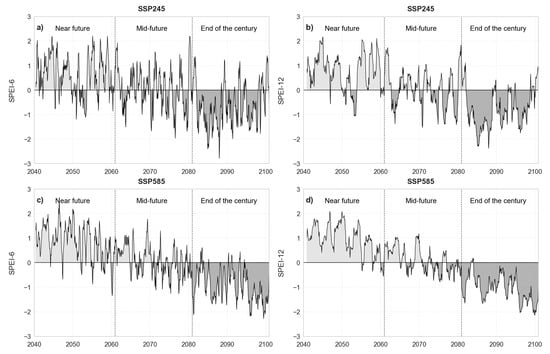

It is important to note that, while the SPI can predict droughts, a more realistic assessment of drought conditions is achieved through indices such as the SPEI. Considering the SPEI under the SSP245 scenario at the six-month timescale indicates an increase in drought events, mainly at the end of the century. In the period from 2061 to 2080, moderate and severe droughts account for approximately 15.79% and 7.89% of observed cases. By the end of the century, our projections suggest a reduction in abnormal droughts and a rise in severe and moderate drought occurrences, expected to account for 26.09% and 22.28% of occurrences, respectively (Figure 6a,b).

Figure 6.

Standardized Precipitation and Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) projected over the 21st century for the Paraopeba River Basin: (a) scenario SSP245—six months; (b) scenario SSP245—twelve months; (c) scenario SSP585—six months; and (d) scenario SSP585—twelve months.

Considering the SSP585 scenario (Figure 6c,d), abnormal droughts mostly occur in the periods 2040–2061 and 2061–2080. Moderate droughts represent 8.33% of the events for the near future, declining by half for the mid-future period. In contrast, by the end of the century, extreme and moderate droughts are projected to increase by 5.53% and 34.10%, respectively. Abnormally dry and severe droughts are less frequent than in the SSP245 scenario.

The observed increases in the SPEI-6 and SPEI-12 reflect dry and prolonged events that correspond with the substantial temperature rises anticipated by the end of the century under the SSP585 scenario (Figure 6c,d). As a result, precipitation is insufficient to meet atmospheric water demand, leading to a notable water deficit in the Paraopeba River Basin. Consistent with the findings of [40], this study demonstrated that the trends were more pronounced for SPEI than for the SPI, highlighting the influence of rising temperatures.

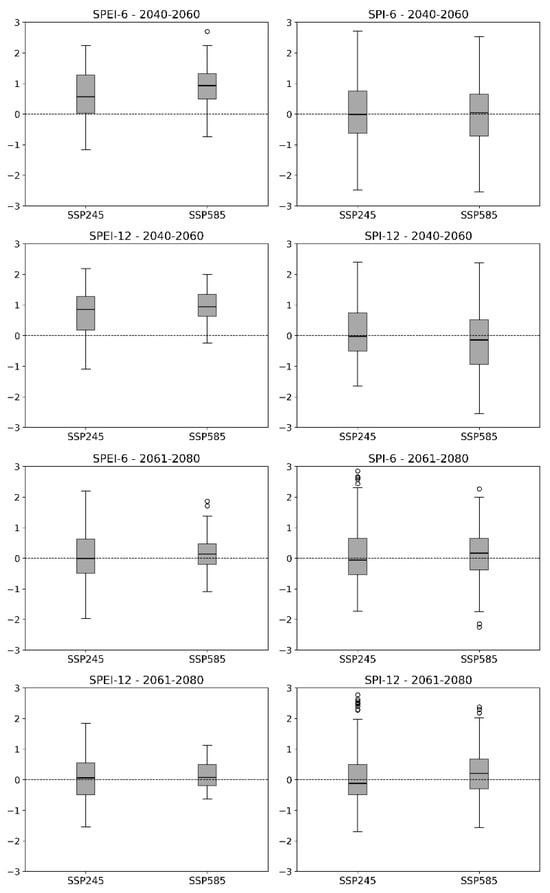

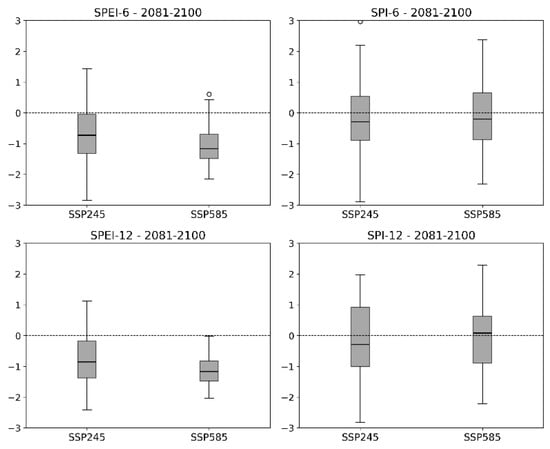

Figure 7 presents an analysis of the SPEI and SPI using box plots for three periods: 2040–2060 (near future), 2061–2080 (mid-future), and 2081–2100 (end of the century). In the near future, positive means were observed with slightly lower values in the SSP585 scenario compared to SSP245 scenario. For 2081–2100, SPEI-12 indicates drier conditions compared to the SPEI-6 timescale, suggesting a higher prevalence of water deficits under the higher emission scenario. Additionally, this scenario displays a lower interquartile variation, which may reflect reduced interannual variability and persistent dry conditions throughout the period.

Figure 7.

Boxplot of 2040–2060, 2061–2080, and 2081–2100 periods for the SPI and SPEI for the Paraopeba River Basin, in the SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios and timescale of six and twelve months.

4. Discussion

Promoting greater awareness of drought is essential [17,18]. Increasingly arid conditions can jeopardize water availability for various needs, including human consumption, agriculture, industry, and hydropower generation, and have significant impacts on the conservation of aquatic ecosystems and biodiversity. Droughts are further linked to heightened risks of severe fires and soil degradation. Anticipated water conflicts in the study region will be significant, such as drinking water resources, agricultural irrigation, and hydropower production, which are substantial demands in the Paraopeba River Basin. The quantification of recent and projected droughts under SSP scenarios reveals a trend of more frequent and intense droughts as a consequence of climate change. The ecological and socioeconomic effects may potentially contribute to broader societal disruptions in the future. Enhanced scientific understanding of drought dynamics, their impacts, and temporal changes is critical for informing policymakers, water resource managers, and the public.

Climate signals have provoked a disruptive effect on the Brazil’s energy security [3,4,38]. Considering that 64% percent of country’s total electricity supply is provided by hydropower, climate oscillation has affected hydroelectric outputs, and demand–supply needs to shift to higher-cost thermal power, a mix of renewables, and fossil fuel-based generation during drought periods. Additionally, other similar results are reported by [41] in Brazil, using the SPEI and several climate models (CMIP6 CM6, CM6HR, HadGEM3, IPSL, ESM2, Earth3, and UKESM1) suggested that by 2075, droughts may account for approximately 35% of the country’s agricultural production loss.

The SPEI and SPI produced different results because the former index accounts for increased evapotranspiration due to rising temperatures [3], mainly for the end of the century, under a high emission scenario (SSP585). Since the SPI only considers precipitation, the SPEI incorporates atmospheric evaporative demand, increasing its sensitivity to climate changes. The analysis indicates a continuous water deficit, primarily associated with higher rates of evapotranspiration. The SPEI could be more appropriate than the SPI to monitor drought conditions potentialized by warming conditions, especially in longer timescales, as verified in the end of century scenario.

This study uses a twelve-month timescale to assess meteorological drought, which can support future investigations into the links between meteorological and hydrological droughts. These findings are relevant for hydrological modeling and projecting drought impacts on livelihoods and economic development.

The limitations of this research include reliance on the Thornthwaite method for potential evapotranspiration, which only uses temperature and may not be accurate under future climate conditions. Future research should adopt more physically based methods, such as the reference evaporation used in [40].

Discrepancies may occur because the downscaled projections were bias-corrected using an observational dataset that does not include all stations present in the BR-DWGD dataset (as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4). Bias correction of CMIP6 current scenarios using BR-DWGD directly could prevent these differences and is expected to offer a more accurate representation of the spatial variability of the SPI and SPEI, given the broader coverage of surface observations in the BR-DWGD dataset. Uncertainties remain in future climate scenarios due to limitations in the climate models’ ability to reproduce the magnitude and duration of drought, as noted by [33], which also impacts estimations of the SPI and SPEI.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study showed that the climate models (CMIP6), obtained by the NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 collection, can represent the precipitation and drought patterns in the Paraopeba River Basin. With the use of performance metrics, the models ACCESS-ESM1-5, TaiESM1, CMCC-ESM2, MPI-ESM1-2-LR-1, NorESM2-MM, MRI-ESM2-0, and CanESM5 showed the best performance for the basin.

To characterize the drought, the SPI and SPEI were adopted in two time scales (six and twelve months). Future projections from 2040 to 2100 and two scenarios, SSP245 (intermediate) and SSP585 (pessimistic), were considered. On both time scales analyzed, there was an increase in extreme, moderate, and severe droughts at the end of the century. Severe droughts can increase by 12.24% and 8.59% (SPI) and 22.8% and 17.97% (SPEI) on the six-month timescale, in the SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios, respectively. On the twelve-month timescale, these droughts can increase by 17.14% (SPI), 19.25% (SPEI), 17.12% (SPI), and 19.21% (SPEI), respectively, for the SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios.

Under analysis by the SPEI, it is verified that by the end of the century (2081–2100) there will be an increase in the magnitude of droughts, especially due to the increase in evapotranspiration, which contributes to greater climate dryness. In this period, there is a tendency for the occurrence of prolonged droughts. Thus, the SPI does not accurately reflect the spatial and temporal variability of drought conditions in the context of climate change, but the SPEI does. In general, the SPEI can be a good indicator for assessing drought, as it revealed that water deficit projections might occur, especially in the SSP585 scenario in the twelve-month timescale.

Droughts increase socioeconomic and environmental vulnerability, compromising the water availability of a basin, putting its food, energy, and economic security at risk. Considering that the Paraopeba River Basin plays a strategic role in the generation of electricity and in urban water supply, our results can be used for the projection of drought under the effects of climate change. The results of this study can contribute to guiding public policies for the mitigation and adaptation to these extreme events, to strengthen the resilience of water systems, and ensure the sustainability of natural resources in the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.d.A. and L.A.A.; methodology, C.M.d.A., L.A.A., P.A.M., J.T., C.R.d.M. and P.R.F.P.; validation, C.M.d.A. and L.A.A.; formal analysis, C.M.d.A., L.A.A., P.A.M. and J.T.; investigation, C.M.d.A. and L.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation C.M.d.A., L.A.A., P.A.M., J.T., C.R.d.M. and P.R.F.P.; writing—review and editing, C.M.d.A., L.A.A., P.A.M., J.T., C.R.d.M. and P.R.F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) [Grant number APQ-00709-21], Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) [Grant number 305295/2021-7] and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) [Grant number 305711/2024-5].

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CMIP6I | Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 |

| CORR | Correlation |

| BR-DWGD | Brazilian Daily Weather Gridded Data |

| GCM | Global Climate Models |

| SPEI | Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index |

| SPI | Standardized Precipitation Index |

| SSPs | Shared Socioeconomic Pathways |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| RMSEbias | Mean Square Error After the Removal of a Constant Bias |

References

- Gebrechorkos, S.H.; Sheffield, J.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Funk, C.; Miralles, D.G.; Peng, J.; Dyer, E.; Talib, J.; Beck, H.E.; Singer, M.B.; et al. Warming Accelerates Global Drought Severity. Nature 2025, 642, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujol-Buxó, E.; Montori, A. Assessing the Risks of Extreme Droughts to Amphibian Populations in the Northwestern Mediterranean. Land 2025, 14, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C.d.M.M.; Alvarenga, L.A.; Silva, V.O.; Carvalho, V.S.O.; Caminha, A.R.; Melo, P.A. Projeção Dos Eventos de Seca Meteorológica e Hidrológica Na Bacia Hidrográfica Do Rio Verde. Rev. Bras. De Meteorol. 2024, 39, e39240059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, C.R.; Guzman, J.A.; Vieira, N.P.A.; Viola, M.R.; Beskow, S.; Guo, L.; Alvarenga, L.A.; Rodrigues, A.F. Mitigating Severe Hydrological Droughts in the Brazilian Tropical High-Land Region: A Novel Land Use Strategy under Climate Change. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2025, 13, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawren, J.; Santos, C.; Silva, T. XXI Simpósio Brasileiro de Recursos Hídricos Crise Hídrica Na Bacia Hidrográfica Do Manancial Serra Azul (Minas Gerais). In Proceedings of the XXI SBRH—Simpósio Brasileiro de Recursos Hídricos, Brasília, Brazil, 27 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barros da Silva, B.M.; Da Silva, D.D.; Moreira, M.C. Índices Para a Gestão e Planejamento de Recursos Hídricos Na Bacia Do Rio Paraopeba, Estado de Minas Gerais. Rev. Ambiente Água 2015, 10, 685–697. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Pinto, P.R.F. Segurança Hídrica Na Bacia Hidrográfica Do Rio Paraopeba 2024. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Lavras, Lavras, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Honorato, P.A.d.R.; Elmiro, M.A.T.; Nero, M.A.; Temba, P.d.C.; Jardim, H.L. A Contribuição Do Modelo FPEIR/TOPSIS No Diagnóstico Ambiental Da Segurança Hídrica de Áreas Atingidas Pela Barragem B1, Brumadinho, MG. Soc. Nat. 2025, 37, e74110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicq, R.; Leite, M.G.P.; Leão, L.P.; Nalini Júnior, H.A.; da Cunha e Silva, D.C.; Fonseca, R.; Valente, T. Hydrogeochemistry of Surface Waters in the Iron Quadrangle, Brazil: High-Resolution Mapping of Potentially Toxic Elements in the Velhas and Paraopeba River Basins. Water 2025, 17, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, D.J.; Elmiro, M.A.T. Técnicas de Sensoriamento Remoto Aplicados na Análise de Seca em Bacias Hidrográficas: Estudo de Caso na Sub-Bacia Do Ribeirão Serra Azul-MG. Caminhos De Geogr. 2024, 25, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.; Gonçalves, N.; Das, F.; Vasconcelos Junior, C.; Sakamoto, M.S.; Da, C.; Silveira, S.; Passos, E.S.; Martins, R. Índices e Metodologias de Monitoramento de Secas: Uma Revisão. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2021, 36, 495–511. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Arra, A.; Şişman, E. Correction: Abu Arra, A.; Şişman, E. Characteristics of Hydrological and Meteorological Drought Based on Intensity-Duration-Frequency (IDF) Curves. Water 2023, 15, 3142. [Google Scholar]

- Royer, A.C.; Figueiredo, T.d.; Fonseca, F.; Schütz, F.C.d.A.; Hernández, Z. Tendências de Mudança Na Precipitação e Na Susceptibilidade à Seca Avaliada Pelo Índice de Precipitação Normalizada (SPI) No Nordeste de Portugal. Territorium 2021, 28, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, M.D.; Dallacort, R.; Dias, V.R.d.M.; Fenner, W.; Tieppo, R.C.; Oliveira, G.C. Análise da Precipitação e Identificação de Eventos de Seca em Municípios do Oeste de Mato Grosso por Meio dos Índices SPEI-3 E SPEI-6. Nativa 2024, 12, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagge, J.H.; Tallaksen, L.M.; Gudmundsson, L.; Van Loon, A.F.; Stahl, K. Candidate Distributions for Climatological Drought Indices (SPI and SPEI). Int. J. Clim. 2015, 35, 4027–4040. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Xia, J.; Wang, M. Comparative Study on Bivariate Statistical Characteristics of Drought in Shandong Using SPI and SPEI. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; Lorenzo-Lacruz, J.; Camarero, J.J.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Revuelto, J.; Morán-Tejeda, E.; Sanchez-Lorenzo, A. Performance of Drought Indices for Ecological, Agricultural, and Hydrological Applications. Earth Interact. 2012, 16, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mckee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The Relationship of Drought Frequency and Duration to Time Scales. Eighth Conf. Appl. Climatol. 1993, 17, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, D.C. Atmospheric Teleconnections and Their Impact on Precipitation Patterns in the Brazilian Legal Amazon: Insights from the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI). Theor. Appl. Clim. 2025, 156, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernanda, P.; Gonçalves, A.; Potozky De Oliveira, R.; Carpenedo, C.B. Eventos de Seca e Estiagem no Estado do Paraná Associados ao Índice SPEI. In Proceedings of the IV Encontro Nacional de Desastres—Associação Brasileira de Recursos Hídricos, Curitiba, Brazil, 11 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, V.S.O.; Alvarenga, L.A.; Melo, P.A.; Tomasella, J.; de Mello, C.R.; Martins, M.A. Climate Change Impact Assessment in a Tropical Headwater Basin. Rev. Ambiente Água 2022, 17, e2753. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarenga, L.A.; Carvalho, V.S.O.; de Oliveira, V.A.; de Mello, C.R.; Colombo, A.; Tomasella, J.; Melo, P.A. Hydrological Simulation with SWAT and VIC Models in the Verde River Watershed, Minas Gerais. Rev. Ambiente Água 2020, 15, e2492. [Google Scholar]

- Zákhia, E.M.S.; Alvarenga, L.A.; Tomasella, J.; Martins, M.A. Avaliação de Projeções Climáticas Para Uma Bacia Experimental, Localizada Na Região Sul de Minas Gerais. Rev. Ibero-Am. De Ciências Ambient. 2020, 11, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, L.A.; de Mello, C.R.; Colombo, A.; Cuartas, L.A.; Chou, S.C. Hydrological Responses to Climate Changes in a Headwater Watershed. Ciência E Agrotecnologia 2016, 40, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrasher, B.; Wang, W.; Michaelis, A.; Melton, F.; Lee, T.; Nemani, R. NASA Global Daily Downscaled Projections, CMIP6. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, S.; Mengistu Tsidu, G.; Dosio, A.; Mphale, K. Assessment of Historical and Future Mean and Extreme Precipitation Over Sub-Saharan Africa Using NEX-GDDP-CMIP6: Part I—Evaluation of Historical Simulation. Int. J. Climatol. 2025, 45, 8672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mendonça, L.M.; Blanco, C.J.C.; da Silva Cruz, J. Performance and Projections of the NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 in Simulating Precipitation in the Brazilian Amazon and Cerrado Biomes. Int. J. Climatol. 2024, 44, 3726–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.G.; Martins, F.B.; Martins, M.A. Climate Risks and Vulnerabilities of the Arabica Coffee in Brazil under Current and Future Climates Considering New CMIP6 Models. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.; Coorientador, T.; Flávio Justino, B.; Castro, M.P. Áreas Protegidas do Cerrado: Vulnerabilidade e Adaptação Às Mudanças Climáticas. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, S.W.; Correa, W.d.S.C. Um Alerta Vermelho Para a Humanidade: As Principais Conclusões Dos Três Relatórios de Avaliação (AR6) Do IPCC de 2021 e 2022; Instituto de Estudos Climáticos: Espírito Santo, Brazil, 2022; pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, A.C.; Scanlon, B.R.; King, C.W.; Alves, A.I. New Improved Brazilian Daily Weather Gridded Data (1961–2020). Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 8390–8404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, P.A.; Alvarenga, L.A.; Tomasella, J.; de Mello, C.R.; Martins, M.A.; Coelho, G. Analysis of Hydrological Impacts Caused by Climatic and Anthropogenic Changes in Upper Grande River Basin, Brazil. Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielke, R.A.S. Mesoscale Meteorological Modeling, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 1–570. [Google Scholar]

- Mukaka, M.; Moulton, L.H. Comparison of Empirical Study Power in Sample Size Calculation Approaches for Cluster Randomized Trials with Varying Cluster Sizes—A Continuous Outcome Endpoint. Open Access Med. Stat. 2016, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornthwaite, C.W. An Approach toward a Rational Classification of Climate. Geogr. Rev. 1948, 38, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguería, S.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Reig, F.; Latorre, B. Standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) revisited: Parameter fitting, evapotranspiration models, tools, datasets and drought monitoring. Int. J. Clim. 2014, 34, 3001–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman, N.B. Accepting the Standardized Precipitation Index: A Calculation Algorithm. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2007, 35, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzanela, A.C.; Dereczynski, C.; Luiz-Silva, W.; Regoto, P. Performance of CMIP6 Models over South America. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 1501–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasella, J.; Cunha, A.P.M.A.; Simões, P.A.; Zeri, M. Assessment of Trends, Variability and Impacts of Droughts across Brazil over the Period 1980–2019. Nat. Hazards 2023, 116, 2173–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, F.; Helfand, S.M.; Moreira, A. Climate Change, Drought, and Agricultural Production in Brazil. In Proceedings of the 32nd Internacional Conference of Agricultural, New Delhi, India, 27 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).