Abstract

Community revitalization is a complex, multifaceted process, studied conceptually and empirically in the vast multidisciplinary literature. Among the cited elements of community revitalization are housing; school, civic, and retail spaces; street networks; parks; and green spaces. However, the elements are commonly studied in isolation, not considering their interrelated qualities as all-of-a-piece of the community revitalization process. In this paper, we draw on the concept of the neighborhood unit that facilities a holistic approach to community revitalization. We show how the neighborhood unit is metamorphosed and thereby endured from the classic to the contemporary. We argue that the neighborhood unit informs, as well as being challenged by, community revitalization. Furthermore, inadequate attention is given to how urban revitalization challenges the efficacy of the neighborhood unit itself. The inner-city blight provides an impetus to look beyond the neighborhood to the metropolitan region as a whole. The neighborhood unit’s fundamental limitation is posed by its cellular autonomy, in favor of alternatives that connect the neighborhood to the metropolitan region’s jobs–housing–services–mobility opportunity holistically. Our literature review of the impactful elements of community revitalization is aided by AI (ChatGPT) as an expeditious search engine. It is found that the AI-aided search of the universal poses anew the significance of the particular—the site- and context-specific. We conclude with universal “performance dimensions” of Good City Form that are calibrated locally, reflecting the goodness of the city form, of which the neighborhood is a building block.

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

Problem. Community revitalization is a multifaced phenomenon comprising elements that are interrelated but commonly addressed in isolation, hindering effective urban planning and policy implementation. Rarely are the interrelated elements of the community revitalization process viewed holistically. Purpose. This article aims to draw together elements of the community revitalization process that reflect the metropolitan region’s fundamental building block: the neighborhood. Methods. The classic Perry neighborhood unit and its subsequent metamorphoses supply a heuristic for a review and synthesis of the community revitalization process that is informed by the neighborhood unit elements. The literature review and synthesis are aided by AI, an effective, expeditious tool that is particularly useful in community revitalization, characterized by a vast and scattered literature. Results and conclusions. Schools, housing, services, parks, and open spaces are the neighborhood unit elements that inform community revitalization. However, it is found that the significance of one element of community revitalization is contingent upon another; for example, parks and open spaces are accessible amenities for both the neighborhood and school, and housing and transportation are connected elements of a comprehensive plan. Thus, the plausibility of our holistic approach to community revitalization informed by the neighborhood unit is justified. Finally, the AI search of the universal elements of the community revitalization process poses anew the significance of the particular—the site- and neighborhood-specific. We conclude with a future research direction by applying Performance Dimensions of Good City Form that gauge community vitality, sense, fit, access, and control with efficiency and justice.

1.2. Community Revitalization and the Neighborhood Unit

The neighborhood is a fundamental building block of the metropolitan region. A holistic concept of the neighborhood is provided by Perry [1]. Noteworthy is the idea that a plan for large metropolitan regional growth (New York) should also include the design of a small-scale walkable neighborhood. Considered as a unit, Perry’s neighborhood endures from the Regional Plan of New York (1929) to 1980s traditional neighborhood development (TND) to transit-oriented development (TOD, 1990s) and sustainable urbanism (2000s)—Perry [1], Stein [2], Duany and Plater-Zyberk [3], Calthorpe [4,5], Farr [6]. The discussion of urban sustainability and resilience in the twenty-first century with the emerging concept of the 15- minute city highlights the pedestrian-friendly property of the neighborhood unit (Fol and Gallez [7]; Weng et al. [8]; Allen and Farber [9]; Ferrer-Ortiz et al. [10]; Carson et al. [11]; Jun et al. [12]). The transformations of the neighborhood unit with the modified organization of land use and spatial extent are recorded in the literature, from the highway to the boulevard, to the decentered locations of schools, transit, and cars and the integrated natural (riparian land) and built environment (Duany and Plater-Zyberk [3]; Calthorpe [4]; Farr [6]).

Notwithstanding its conceptual durability, the neighborhood unit is rarely discussed in conjunction with the strategy of urban revitalization. The juxtaposition of the neighborhood unit and community revitalization frames the principal research design of this paper. This juxtaposition is informative as a two-way street. The neighborhood unit informs, and is informed by, community revitalization. The elements of the neighborhood unit inform and effectively draw together, rendering a holistic view of the multifaced community revitalization, but are commonly regarded piecemeal and isolated in the scattered urban studies literature. Thereby, we fill this gap and draw on the vast literature to highlight how each and every element of the neighborhood unit informs a strategy of community revitalization—from school, civic, and religious institutions to retail services and the provision of open spaces. For example, the school–neighborhood nexus is exemplified by the concept of a “wrapround” services school (Khadduri et al. [13,14]; Britt et al. [15]). Faith institutions are well-known catalysts in community revitalization (Raymond [16]). The school and church are among two of the neighborhood unit’s most enduring elements. The urban studies literature similarly invokes the neighborhood unit elements of housing, parks and open spaces, and street networks in the discussion of impactful urban revitalization, albeit in a scattered literature (Zhao et al. [17], Crompton [18], Voicu and Been [19], Day et al. [20], Balcetis et al. [21]).

Concomitantly, community revitalization challenges the neighborhood unit, revealing strengths and limitations. The inner-city blight provides an impetus to look beyond the neighborhood to the metropolitan region as a whole (Downs 1973 [22]; Ross and Leigh [23]; Calthorpe and Fulton [5]; Banai and Ploderer [24]; Banai, Antipova, and Momeni [25]; Banai and Momeni [26]). The neighborhood unit’s fundamental limitation is posed by its cellular autonomy, in favor of alternatives that connect the neighborhood to the metropolitan region’s jobs–housing–services–mobility opportunity holistically. Among the alternatives are neighborhood units that also provide public transit access for regional mobility and an integrated built and natural environment (Calthorpe [4]; Calthorpe and Fulton [5]; Farr [6]). Arguably, the metamorphosed neighborhood unit better copes with the challenges of community revitalization, particularly in inner city blighted neighborhoods with a jobs–housing imbalance, public transit-dependent population, and limited access to the metropolitan region’s jobs, services, and parks and open spaces (Section 1.3).

We provide a brief review and synthesis of the neighborhood unit’s impactful elements of community revitalization (Section 2). Our brief review is aided by a tool—AI—that is used in wide-raging applications. AI is particularly suitable for community revitalization, which is characterized by a vast and scattered literature. However, we supplement our search with our own review of the urban studies literature. We highlight the effectiveness of strategies relative to each of the targeted element(s) of the neighborhood unit considered.

Finally, having reviewed the impactful neighborhood unit elements as a whole, we pose, for AI, the question of the relative importance of the impactful community/neighborhood revitalization elements: schools, the housing mix, street network, parks, and open spaces (Section 3). Interestingly, the AI-aided search of the universal poses anew the significance of the particular—the site- and context-specific. This finding motivates the discussion of a future research direction by applying Lynch’s [27] Performance Dimensions.

1.3. The Neighborhood Unit: A Brief Update

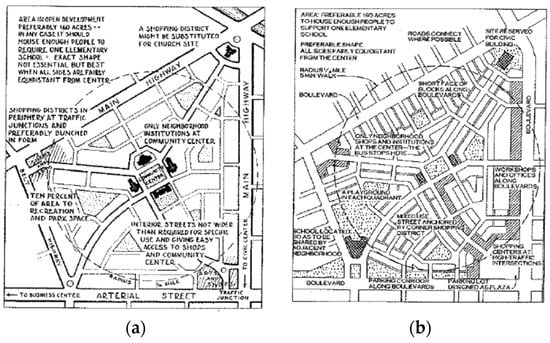

The neighborhood unit first appeared as a part of the Regional Planning Association of America’s planning of the New York region (Perry [1]) (Figure 1a) Noteworthy is that a large-scale plan of a vast metropolitan region (New York and its environs) is also mindful of its pedestrian-friendly neighborhood scale. The neighborhood unit is defined by a quarter-mile distance to a centrally located elementary school that provides an equitable, safe distance from homes to the school. Centrally located are also other neighborhood institutions. The church site is prominent; however, it is interchangeable with a shopping district. Furthermore, 10 percent of a 160-acre neighborhood area is “recreation and park space”. Also noteworthy is the location of shops in proximity to apartments, with visibility from arterial streets. The neighborhood connection to the “business center” is indicated from the arterial street, as is the connection to the “civic center” from the “main highway”. Thus, the neighborhood unit is of mixed use, with homes, apartments, neighborhood institutions, shops, and parks. This feature informs community revitalization, as our review indicates.

Figure 1.

The evolving morphology of the neighborhood unit since 1929. From (a) neighborhood unit (1929 Regional Plan of New York) to (b) traditional neighborhood development (1980s) to (c) TOD (1990s) and (d) sustainable neighborhoods (2008). (Sources: Calthorpe [4]; Farr [6]).

The neighborhood unit’s metamorphosis in the decades following its introduction by Perry [1] has retained the pedestrian-scale of a quarter mile to the accessible civic center and services with a five-minute walk. Traditional neighborhood development (TND), which emerged in the 1980s, retained the quarter-mile radius. The elementary school is still present, albeit de-centered to a location that also caters to the adjacent neighborhood. Effectively, this school relocation is an indication of the strategic view of the neighborhood unit beyond its territory. We highlight this feature in community revitalization further below, particularly in blighted communities, where a strategic remediation is the connection of the neighborhood with resources throughout the metropolitan region, with access to jobs with regional mobility. In summary, the school as a civic space is integrated with the neighborhood; housing is single-family and multi-family; retail and shops are in high-traffic locations catering to the neighborhood and beyond; green/open space is located throughout; streets are pedestrian-friendly; and access is multimodal, including cars and transit.

The neighborhood unit of sustainable urbanism (Farr [6]) plausibly diagrammatically includes a transit stop and a transit corridor, in contrast to Perry’s [1] arterial and main highway. However, as Banai [28] noted, the relation and configuration of the transit stop and corridor to the next neighborhood unit in the metropolitan region is not indicated. The metropolitan-wide perspective is supplied by Calthorpe’s [4,29] transit-oriented development (TOD). The metropolitan region is a constellation of TOD distinguished by urban vs. neighborhood types. The distinguishing feature is the location along the rail transit trunk (urban TOD) vs. the feeder bus stop (neighborhood TOD), with a connection to the rail station. Like the sustainable urbanism’s (Farr [6]) 10 min walk, the radius from the center to the periphery is increased to 2000 feet in TOD, compared to the five-minute walk in Perry’s quarter-mile neighborhood unit and TND.

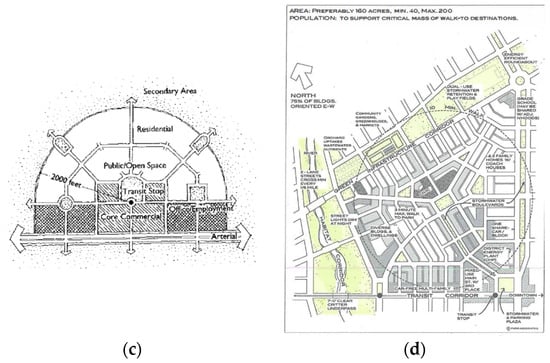

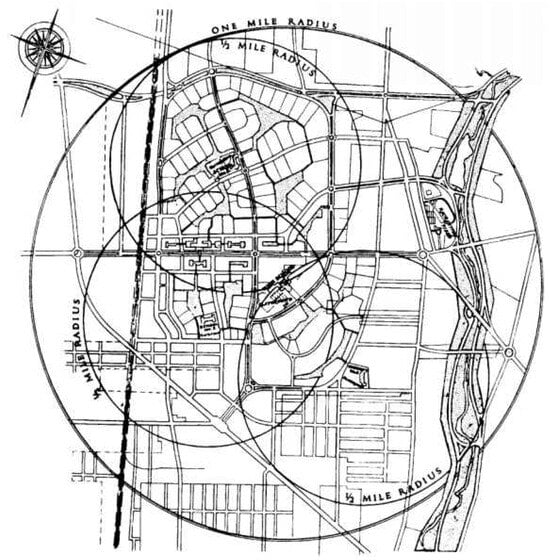

Farr’s sustainable neighborhood also accommodated nature with riparian land, beyond the small parks and open spaces in Perry’s neighborhood unit and TND. However, the larger, regional view of nature (preserves) in urban development is supplied by Calthorpe [4]. In regard to the view of nature in urban development, we recall the town plan of Radburn that was contemporary with Perry’s neighborhood plan of the New York region. Riparian land is highlighted together with green open spaces within the neighborhood (Figure 2). Compare the 1930s Radburn neighborhood with Farr’s [6] sustainable urbanism. In the Raburn plan, neighborhoods are defined not by the quarter-mile radius of an elementary school in Perry’s but by an increased half-mile radius, the same distance as in Farr’s neighborhood. However, the juxtaposition of the half-mile radius neighborhoods is functionally determined by the locations of schools, from elementary to high schools (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Riparian land highlighted as an element of the park open system in Radburn’s plan (1929). Compare the sustainable neighborhood unit in Figure 1d above (source: Stein [2]).

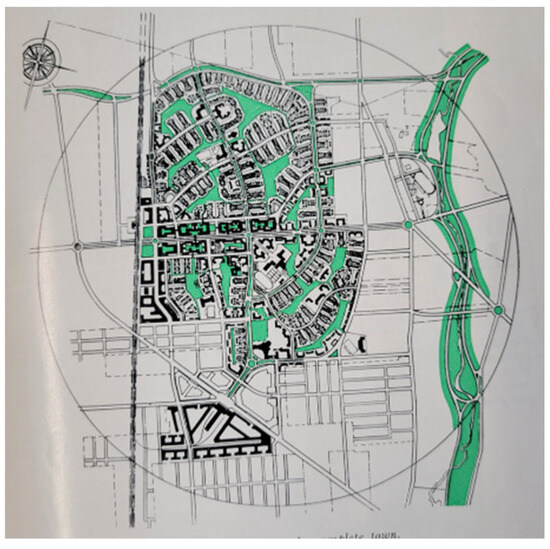

The constellation of the neighborhood units is determined by the hierarchy of a facility (school) distinguished by size. The historic Radburn plan thus provides views of the neighborhood beyond its territory. The hierarchical service differentiation is plausibly applied to the metropolitan region’s resources, with the provision of jobs, retail, and open spaces (see also the hierarchy of retail in Figure 3. In summary, public green open space is in balance with private residential space; residential, commercial, and retail land use are integrated for community self-sufficiency; land use is mixed, with residential, schools, and community centers; and there are implications of the facility hierarchy for the regional city (see Stein [2]).

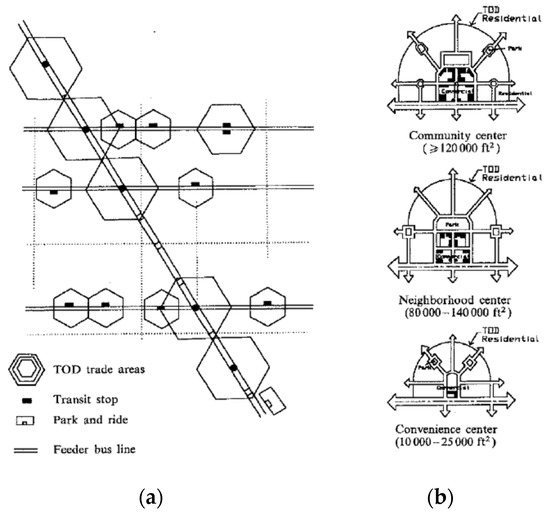

Figure 3.

Revisiting Radburn: neighborhoods are defined by schools and parks/open space. The nested neighborhoods are centered by an elementary school. The school serves multiple neighborhoods. A hierarchy of facilities (schools) distinguished by size is embedded in multiplicity (source: Stein [2]).

Whereas the Perry neighborhood unit is defined by the central location of an elementary school, the updated traditional neighborhood school is in a peripheral location so that it can also cater to the bordering neighborhood. Interestingly, we have to revert to the neighborhood plans that preceded TND, whereby the school is located to serve three neighborhoods (Figure 3).

The nested neighborhoods expanded in size, from a quarter- to a half-mile radius, each centered by an elementary school. Public, green open space is integrated with private residential space. The school serves multiple neighborhoods. A hierarchy of facilities (schools) distinguished by size is embedded in multiplicity. The implications of the facility hierarchy for the regional city are suggested. For the hierarchy of retail, see Calthorpe [4], Figure 4. For an example of a supermarket chain downsized to fit the scale of a walkable urban and suburban neighborhood, see Banai and Antipova [30]. The supermarket’s location in the arterial street and accessible from housing within walking distance is akin to the classic Perry [1] neighborhood unit’s shop location that caters to both vehicular and pedestrian traffic, local and extra-local.

Community revitalization is a complex, multifaceted process addressed in the vast urban studies literature with strategic and policy implications. Having acknowledged its durability, Banerjee and Baer [31] considered the neighborhood unit critically for policy implications. However, by substituting “residential areas” instead of the neighborhood unit, Banerjee and Baer [31] effectively forfeited the holistic notion of the neighborhood unit. However, the holistic property that the neighborhood unit connotes necessitates that the revitalizing elements of a community are effectively considered jointly. Thereby, the neighborhood unit effectively renders a synthesis of the community revitalization literature. The synthesis provides a holistic perspective on community revitalization that is missed when the neighborhood elements are viewed piecemeal and isolated. In the section that follows, we briefly review how each of the elements of the durable neighborhood unit informs community revitalization. The literature review is aided by ChatGPT3.5.

Figure 4.

(a) Central place representation of TOD and (b) classification of retail center by type—community (>120,000); neighborhood (80,000–140,000); convenience (10,000–25,000) (SF), adapted from Calthorpe [4], Banai [32]; see also Brown [33].

1.4. A Note on Search Method: ChatGPT

The emergence of OpenAI and ChatGPT is a discussion point in the academic, government, and business sectors (Önden and Alnour [34]; Donmez [35]). Bibliometric analysis is a research application of OpenAI and ChatGPT. Önden and Alnour [34] identify authors in institutions in the U.S. and Germany that use OpenAI and ChatGPT in research. The idea that AI has captured the attention of the scholarly community is not surprising. A review of the existing research is a precursor to and integral part of a data-driven research methodology for the production of new contributions. Gabashvili [36] uses AI for a systematic review of the existing reviews, identifying its potential as well as areas for further study. Giray et al.’s [37] assessment of ChatGPT in scientific research uses a strategic analytic framework with SWTO—strengths, weaknesses, threats, and opportunities (Xames &Shefa [38]). The conclusion is that ChatGPT aids researchers in retrieving and synthesizing large amounts of data expeditiously; however, it should be used carefully, thereby identifying biases, and examining the validity of the results (see also Ullah et al. [39]; Zhao et al. [17]; Zhu et al. [40]; Gabashvili [36]; Onden & Alnour [34]; Sarrion [41]).

Community revitalization epitomizes a field within urban studies characterized by wide-ranging issues that are commonly known as interrelated. Urban revitalization is plausibly studied at the neighborhood scale, a fundamental unit of the metropolitan region’s geography. The issues include housing, constituting a significant portion of the metropolitan region’s land use; schools, constituting elements of the neighborhood; parks and open spaces, which contribute to community health and vitality; and safety, including the circulation of vehicles and pedestrians. Access to jobs and services poses the problematic connection of the neighborhood to the metropolitan region. Given the wide-ranging issues, faith institutions are among the key participants catering to the neighborhood (Tarpeh and Hustedde [42]). We posed the question of religious institutions’ role in community revitalization to ChatGPT.

How impactful are faith-based institutions for community or neighborhood revitalization? (ChatGPT 3.5, 1/11/2023). The response is as follows.

Faith-based institutions, such as churches, mosques, synagogues, temples, and other religious organizations, can have a significant impact on community or neighborhood revitalization. While faith-based institutions can have a positive impact on community or neighborhood revitalization, it is important to note that their effectiveness can vary widely depending on the specific organization, its leadership, and its level of community engagement. Additionally, there are concerns about potential exclusion or discrimination within some religious institutions. It is essential to strike a balance between their positive contributions and the need to respect diversity and inclusivity within the community.

The elements and their interrelationships comprise the vast urban studies literature. To retrieve the impactful elements of community revitalization, we use ChatGPT’s expeditious search engine. However, as noted above, to ensure coherence, we are guided by a neighborhood model that has endured decades of metropolitan growth, from the Regional Planning Association of America with Perry’s neighborhood unit in the 1930s to the new urbanism’s traditional neighborhood development (TND) in the new millennium. In the section that follows, we briefly highlight the neighborhood unit’s most impactful elements that inform community revitalization. The brief review of the literature is also aided by ChatGPT to identify how each element of the neighborhood unit contributes to community revitalization.

2. The Impactful Neighborhood Unit Elements: What Do We Know?

2.1. The School

The Perry [1] neighborhood unit is determined by a five-minute walk from the elementary school, which is centrally located with civic spaces to ensure equality of access. The school remains as a civic space in subsequent transformations of the neighborhood unit with new urbanism’s TND (Duany and Plater-Zyberk [3]) and Farr’s [6] “sustainable neighborhood unit,” albeit located peripherally to be shared with bordering neighborhood units. It is found that the evolution of the neighborhood unit in recent years poses anew the organization of the three neighborhoods that are served by a school in the Radburn plan (Figure 3).

The school remains an organizing element, although the size of the neighborhood unit is increased compared with both the classic and the contemporary versions. Noteworthy is the presence of a hierarchy of facilities (schools) distinguished by size, embedded in multiplicity. We return to the concept of a hierarchy and its implications for the strengths and limits of the neighborhood unit concept.

How does the school, a durable elemental concept of a neighborhood unit, (in)form a strategy of community revitalization? We pose this question for ChatGPT3.5.

How impactful is a school for community or neighborhood revitalization? (ChatGPT3.5, 1/11/2023). The response is as follows (italics added).

Schools can play a significant role in community or neighborhood revitalization. Their influence goes beyond education and can have a positive impact on various aspects of a community. It is important to note that the relationship between schools and community revitalization is complex and multifaceted. While schools can play a crucial role in the process, they are just one part of a broader ecosystem of factors that contribute to community revitalization. Effective revitalization efforts usually require collaboration among multiple stakeholders, including local governments, community organizations, and residents, in addition to educational institutions.

Our own review of the literature suggests similar findings.

Schools are key component in the revitalization process since they can act as a community’s anchor institution and as a catalyst for improvement (Khadduri et al. [13]; Pesch [43]; Green [44]; Britt et al. [15]). Schools are essential in promoting moral development, economic growth, involvement in the community, and other goals, including reducing crime rates (Britt et al. [15]; Pesch [43], Green [44]). The effectiveness of schools in neighborhood regeneration varies by elements including educational quality, community involvement, and district resource availability (ChatGPT3.5, 1/11/2023). However, schools by themselves cannot resolve all of the intricate problems that a community faces. Successful community revival frequently requires a comprehensive strategy incorporating numerous stakeholders and solutions (Horn [45]; Pesch [43]; Khadduri et al. [13,14]).

The significance of the neighborhood unit’s interrelated elements is best determined by the relation of school and the neighborhood of which it is a part (Khadduri et al. [13,14]). The relation is exemplified by the notion of the services school (Khadduri et al. [13,14]; Cumming et al. [46]; Pesch [43]; Horn [45]; Jordan et al. [47]. Pesch [43] highlights the role of public schools as active participants in holistic planning for urban revitalization. Interestingly, the neighborhood association regards school academic achievement as an element of the comprehensive neighborhood revitalization.

As a final note, the school site’s central location in the classic neighborhood unit indicates its prominence on par with civic community facilities. However, in the contemporary neighborhood unit, e.g., TND, both the school and civic sites gain even greater prominence with extra-local visibility and connectivity.

2.2. Housing

The neighborhood unit has a feature that remains throughout its transformation: the housing mix. The neighborhood unit accommodates a variety of housing, with single-family as well as multi-family units. The mix of housing in a pedestrian-friendly neighborhood unit endures from the classic to the contemporary concepts of the neighborhood unit. The housing mix is considered as a feature of sustainable urbanism (see also Edelsberg [48]; Chakaborty [49]). It is in contradistinction to single-use zoned suburban sprawl, with mainly single-family housing, deemed unsustainable.

We pose the following question for ChatGPT3.5.

How impactful is housing for community or neighborhood revitalization? (ChatGPT3.5, 1/11/2023). The response is as follows (italics added).

Housing plays a significant role in community or neighborhood revitalization and can have a substantial impact on the well-being and vibrancy of an area. To achieve effective community or neighborhood revitalization through housing, it is essential to engage in comprehensive and holistic strategies that address not only housing itself but also factors like transportation, education, healthcare, and social services. Additionally, community input and participation are crucial in shaping revitalization plans to meet the specific needs and aspirations of residents.

Housing-related issues are a key component of initiatives that revitalize communities and safeguard their sustainability for the future (Skobba and Tinsley [50]). A comprehensive and inclusive housing revitalization plan is accountable to the particular requirements and conditions of the neighborhood (Brown et al. [51]; ChatGPT3.5, 1/11/2023). The preservation of affordable housing in the face of gentrification, homelessness, and zoning laws are included in plans for community revitalization (Silverman et al. [52]; Kazis et al. [53]; Skobba and Tinsley [50]; Goetze [54]; Rohe & Steward [55]; US Dept. of Housing and Urban Development [56]).

Housing affordability is addressed by the availability of multi-family housing. The classic neighborhood unit is shown as apartments in proximity to shops and homes (Perry [1]). Multi-family housing is not always welcome in proximity to single-family housing, particularly in suburban subdivisions, where they are zoned out. However, a recent study finds no or a positive single-family home sale price effect in proximity (2000 feet) to the varying forms of multi-family housing (Craw [57]).

2.3. Parks and Open Spaces

Parks and open spaces are essential land uses in the neighborhood unit. The Perry neighborhood unit [1] allocates 10 percent of the quarter-mile radius of the centrally located civic institutions, including schools. The traditional neighborhood unit (Duany and Plater-Zyberk [3]) provides small “pocket” parks accessible throughout. The sustainable neighborhood unit (Farr [6]) incorporates the site’s natural elements like riparian land as an open space feature of the neighborhood unit, including small open spaces distributed within an expanded radius of a 10 min walk, instead of the 5 min in the Perry neighborhood unit or TND.

Noteworthy is Radburn’s NJ neighborhood plan, produced in the 1930s (see Stein [2], which remarkably resembles a sustainable neighborhood (Farr [6]), highlighting natural and riparian land and open space elements (Figure 2).

We question the importance of parks and open spaces for community revitalization with ChatGPT3.5.

What is the role or impact of parks/open spaces/natural spaces in community or neighborhood revitalization? (ChatGPT3.5, 20/10/2023)

Parks, open spaces, and natural elements play a significant role in community and neighborhood revitalization, impacting various aspects of urban life and well-being. Parks, open spaces, and natural elements are essential components of community and neighborhood revitalization. They contribute to physical, social, economic, and environmental well-being, making neighborhoods more attractive, livable, and sustainable. As a result, they are often considered an integral part of urban planning and development strategies.

The sustained relevance of the neighborhood unit is highlighted in the literature, which also lends support to the unified concept of the school–neighborhood–green space. The neighborhood is pedestrian-friendly.

Parks and open spaces are catalysts for urban revitalization (National Recreation and Park Association [58,59]; Kazmierczak [60]); Voicu& & Been [19]. Parks and open spaces are perceived as an accessible amenity for both the neighborhood and school. Fan et al. [61], Dijk-Wesselius et al. [62], and Flaxa [63] presented studies of the impact of walkability on social and physical well-being (see also Fan et al. [61]; Larson et al. [64]). Empirical studies highlight a key ingredient of the neighborhood unit: walkability. This is combined with green spaces, distributed throughout the neighborhood unit, and schools, considered as a bridge to the community.

Noteworthy is the focus on key elements of the neighborhood unit and the sense of community, including open spaces, community centers, schools, and shops in new housing developments (Francis [65]). The perception of open spaces’ and shops’ quality is significantly positively associated with a sense of community. On the more general impact of nature on quality of life in urban sustainability, see also Chiesura [66]).

3. The Neighborhood Unit and Community Revitalization: A Discussion and Conclusions

The neighborhood unit has been a durable concept of urbanism since its inception in the early decades of the twentieth century. The neighborhood unit’s metamorphosis in the twenty-first century has essentially retained the pedestrian-friendly scale of a walkable neighborhood with equitable access to civic institutions and services. Transformations that include an integrated built and natural environment (Farr [6]) and, importantly, the provision of public transit with transit-oriented development (Calthorpe [4,29], which provides regional mobility and access to the metropolitan region’s jobs and services, ensure the sustainability and resilience of the neighborhood unit in the twenty-first century given the challenges of the climate change. The public transit provision with access to the metropolitan region’s jobs and services renders the neighborhood unit accountable to the challenges of the isolated inner city blighted neighborhood, with limited employment opportunities and mobility options (Downs [22]; Ross and Leigh [23]).

With the addition of transit (TOD), the neighborhood unit surmounts the limitation of cellular autonomy and car dependency. Thereby, the transformed neighborhood unit caters to a residential population without automobile ownership. The mixed housing type, as well as land use, which includes shops within walking distance of residents, and green spaces are the neighborhood unit features that inform the revitalization of communities limited to only single-family housing or lacking in retail services. Inner city areas, known as “food” and “park” deserts, and housing affordability epitomize the multifaceted problem of community revitalization. Notwithstanding the neighborhood as a fundamental building block of the metropolitan region, and particularly the durability of the neighborhood unit concept, rarely is the community revitalization process considered similarly holistically in terms of the constituting elements—housing, shops, civics, parks and open spaces, and street networks. Pedestrian-friendly streets that promote walkability are a hallmark of the neighborhood unit. The historic Radburn plan even separated pedestrian and vehicular circulation for safety. Walkability is a feature of revitalized communities, particularly with regard to public health and safety. From housing to schools, community facilities and services, parks, and streets, these elements are the subject of the vast urban studies literature, but they are commonly studied in isolation rather than being considered interdependently, as all-of-a-piece of the community revitalization process. Even when community revitalization is targeted incrementally, the neighborhood unit effectively gauges how the incremental improvement contributes to the vitality of the whole neighborhood. How else can we address the redlined, segregated, blighted, toxic, and unjust neighborhoods but to comprehensively consider the interrelated elements of the neighborhood unit (Rubalcava [67]; Banai and Ploderer [24]; Harris [68]; Kim [69]; Sivac [70]; Ross and Leigh [23]; Barnes et al. [71]; Berry [72]; Quraishi et al. [73]; Ki [74]; Banai, Antipova, and Momeni [25]; Linquist-Grantz et al. [75]; Raymond [16]; Lung-Amam [76]; Ramos [77]; Tannous et al. [78]; Weng et al. [8]; Lenz [79]; Patel et al. [80]; Perez et al. [81]; Banai and Momeni [26]; Antipova, Momeni, and Banai [82])?

We intentionally searched the community revitalization literature with a focus that was limited to the elements of the neighborhood unit considered jointly. We were aided in this search by AI, as well as our own careful review of the literature, mindful of the biases, incompleteness, and inconsistences resulting from artificial search engines. Attention was given to the significance of schools, housing, services, parks, and open spaces in community revitalization. However, it was found that the significance of one element of community revitalization is contingent upon another; for example, parks and open spaces are an accessible amenity for both the neighborhood and school, and housing and transportation are connected elements of a comprehensive plan. Whereas the neighborhood unit is mainly regarded normatively as an ideal concept of community, the revitalization literature sheds light on the heretofore overlooked neighborhood unit’s constituting elements empirically. The neighborhood unit’s holistic perspective suggests a key insight into community revitalization. The question of the relative importance of the elements that constitute a whole that is larger than the sum of the individual parts arises. Given the vast community revitalization literature, we posed this question for ChatGPT.

Which element is more impactful for community/neighborhood revitalization: schools, the housing mix, or parks/open spaces/natural elements? (ChatGPT, 20/10/2023).

The response is as follows (italics added).

Community and neighborhood revitalization is a complex and multifaceted process that typically requires a combination of several elements to be successful. The impact of specific elements can vary depending on the unique characteristics and needs of a community. However, schools, the housing mix, and parks/open spaces/natural elements all play essential roles in community revitalization, and their relative importance can depend on the specific context.

Interestingly, the AI-aided search of the universal poses anew the significance of the particular—the site- and context-specific. With this finding, we recall Lynch’s [27] universal “performance dimensions” that are calibrated locally: vitality, sense, fit, access, and control with efficiency and justice.

To paraphrase Lynch [27], “circumstances and values” differ.

“Groups and persons will value different aspects and assign different priorities to them. But, having measured them, a particular group in a real situation would be able to judge the relative goodness of their place, and would have the clues necessary to improve or maintain that goodness” (Lynch [27], p. 119).

With Lynch [27], the elements of the neighborhood unit—housing, schools, civic institutions, retail shops, parks and open spaces, and street networks—are plausibly considered as scaled by the “performance dimensions.” The performance dimensions reflect the goodness of the city form, of which the neighborhood is a building block. Unlike fixed standards, performance dimensions are scaled in response to the values and circumstances specific to each neighborhood. For a synthetic measure of Radburn’s urban form, determining land use (proportions) quantitatively by the relative importance of the neighborhood qualities of community, privacy, and accessibility, see Banai-Kashani [83]; see also Banai [84]. A future research direction is suggested by applying Lynch’s [27] performance dimensions that gauge community vitality, sense, fit, access, and control with efficiency and justice.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

AI and electronic search engines in the public domain enabled the retrieval of community revitalization literature.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the comments of the reviewers on an earlier version of this article. Joyanta Basak assisted with AI and literature retrieval.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

Due to an error in article production, incorrect references were previously listed in the main text. This information has been updated and this change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Perry, C.A. The neighborhood unit: A scheme of arrangement for the family-life community. In Regional Study of New York and its Environs, VII, Neighborhood and Community Planning, Monograph One 2–140; Regional Plan of New York and its Environs: New York, NY, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Stein Clarence, S. Toward New Towns for America; Reinhold Publishing Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Duany, A.; Plater-Zyberk, E. The Second Coming of the American Small Town; Plan Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1992; pp. 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Calthorpe, P. The Next American Metropolis-Ecology, Community, and the American Dream; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Calthorpe, P.; Fulton, W. The Regional City-Planning for the End of Sprawl; Island Press: Washington DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, D. Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design with Nature; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fol, S.; Gallez, C. Social inequalities in urban access. Better ways of assessing transport improvements. In Urban Access for the 21st Century: Finance and Governance Models for Transportation Infrastructure; Lönnroth, M., Sclar, E.E., Wolmar, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, MY, USA, 2014; pp. 46–86. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, M.; Ding, N.; Li, J.; Jin, X. The 15-minute walkable neighborhoods: Measurement, social inequalities and implications for building healthy communities in urban China. J. Transp. Health 2019, 13, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Farber, S. Planning transport for social inclusion: An accessibility-activity participation approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 78, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Ortiz, C.; Marquet, O.; Mojica, L.; Vich, G. Barcelona under the 15-Minute CityLens: Mapping the Accessibility and Proximity Potential Based on Pedestrian Travel Times. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.R.; Conway, T.L.; Perez, L.G.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.E.; Cain, K.L.; Sallis, J.F. Neighborhood walkability, neighborhood social health, and self-selection among U.S. adults. Health Place 2023, 82, 103036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H.; Hur, M. The relationship between walkability and neighborhood social environment: The importance of physical and perceived walkability. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 62, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadduri, J.; Turnham, J.; Chase, A.; Schwartz, H. Case Studies Exploring the Potential Relationship between Schools and Neighborhood Revitalization. 2003. Available online: https://www.abtassociates.com/files/Insights/reports/2003/Schools_and_Neighborhoods.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Khadduri, J.; Schwartz, H.; Turnham, J.; Schwartz, H. Reconnecting Schools and Neighborhoods. Enterprise. 2008. Available online: https://www.abtassociates.com/files/Insights/reports/2008/64701.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Britt, N.; Bates, S.; Anderson-Butcher, D.; Edwards, R.; Noteman, N.; Brady, C.; DuMond, L.; Childs, T.M. University-Assisted Community Schools as Partners in Neighborhood Revitalization Efforts. Child. Sch. 2022, 45, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, L.K. Revitalizing the Community—Community Street. Architecture Library. Master’s Thesis, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China, 2023; pp. 2–6. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/48537476.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Zhao, Y.; van den Berg, P.E.W.; Ossokina, I.V.; Arentze, T.A. How do urban parks, neighborhood open spaces, and private gardens relate to individuals’ subjective well-being: Results of a structural equation model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. The Impact of Parks on Property Values: A Review of the Empirical Evidence. J. Leis. Res. 2001, 33, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, I.; Been, V. The Effect of Community Gardens on Neighboring Property Values. Real Estate Econ. 2008, 36, 241–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, K.; Anderson, C.; Powe, M.; McMillan, T.; Winn, D. Remaking Minnie Street: The Impacts of Urban Revitalization on Crime and Pedestrian Safety. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2007, 26, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcetis, E.; Cole, S.; Duncan, D.T. How Walkable Neighborhoods Promote Physical Activity: Policy Implications for Development and Renewal. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2020, 7, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, A. Opening Up the Suburbs: An Urban Strategy for America; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C.; Leigh, N. Planning Urban Revitalization and Inner City: An Exploration of Structural Racism. J. Plan. Lit. 2000, 14, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banai, R.; Ploderer, L. The Geography of Industrial Blight: Neglected Options for Sustainable Urban Revitalization. 2019. Available online: https://blogs.memphis.edu/rbanai/files/2019/09/The-Geography-of-Blight.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Banai, R.; Antipova, A.; Momeni, E. Mapping the Morphology of Sprawl and Blight: A Note on Entropy. GeoScape 2021, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banai, R.; Momeni, E. The Neighborhood Impact of Industrial Blight: A Path Analysis. GeoScape 2022, 16, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. A Theory of Good City Form; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Banai, R. The metropolitan region: From concepts to indicators of urban sustainability. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2012, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calthorpe, P. Urbanism in the Age of Climate Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Banai, R.; Antipova, A. Retail Center Viability and Urban Form: A Micro Analysis. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2016, 26, 521–540. Available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09593969.2016.1202855 (accessed on 29 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T.; Baer, W.C. Beyond the Neighborhood Unit: Residential Environments and Public Policy; Springer Science and Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Banai, R. The new urbanism: An assessment of the core commercial areas, with perspectives from (retail) location and land-use theories, and the conventional wisdom. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1998, 25, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. Retail location: The post hierarchical challenge. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 1991, 1, 367–381. Available online: https://chat.openai.com/ (accessed on 8 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Önden, A.; Alnour, M. ChatGPT and OpenAI: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Review. J. Soft Comput. Decis. Anal. 2023, 1, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez, İ.; Idin, S.; Gulen, S. Conducting Academic Research with the AI Interface ChatGPT: Challenges and 543 Opportunities. J. STEAM Educ. 2023, 2, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabashvili Irene, S. The impact and applications of ChatGPT: A systematic review of literature reviews. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.18086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giray, L.; Jacob, J.; Gumalin, D.L. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats of Using ChatGPT in Scientific Research. Int. J. Technol. Educ. 2024, 7, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xames, M.D.; Shefa, J. ChatGPT for research and publication: Opportunities and challenges. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Ullah, B.M.; Arshad, N. Assessing the Transformative Influence of ChatGPTon Research Practices among Scholars in Pakistan. Mesopotamian J. Big Data 2024, 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.J.; Jiang, J.; Yang, M.; Ren, Z.J. ChatGPT and Environmental Research. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 17667–17670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrion, E. The Strengths Limitations of, ChatGPT. In Artificial Intelligence for Business; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 365–382. [Google Scholar]

- Tarpeh, S.; Hustedde, R. How faith-based organizations perceive their role in community development: An exploratory study. Community Dev. 2021, 52, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pesch, P. Connecting Schools to Neighborhood Revitalization: The Case of the Maple Heights Neighborhood Association. Ph.D. Thesis, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2014. Available online: https://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1355&context=dissertations_mu (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Green, T.L. School as Community, Community as School: Examining Principal Leadership for Urban School Reform and Community Development. Educ. Urban Soc. 2018, 50, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, K. Can improvements in schools spur neighborhood revitalization? Evidence from building investments. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2015, 52, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, T.M.; Strnadová, I.; Lee, H.M.; Lonergan, R. Education-centered Formal Wraparound Services in Support of School-Aged Students with Complex Support Needs: A Systematic Review. Australas. J. Spec. Incl. Educ. 2022, 46, 47–60. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/what-we-publish/journals (accessed on 8 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.; Orozco, E.; Averett, A. Emerging Issues in School, Family, & Community Connections. 2020. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED536949.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Edelsberg, E.E. Mixed-Use Development as a Neighborhood Revitalization Strategy: Obstacles and Approaches to Financing. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/35485 (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Chakraborty, A.; McMillan, A. Is Housing Diversity Good for Community Stability? Evidence from the Housing Crisis. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2022, 42, 150–161. [Google Scholar]

- Skobba, K.; Tinsley, K. Addressing housing and neighborhood revitalization needs in Georgia’s rural and small towns: A study of the Georgia Initiative for Community Housing. Community Dev. 2016, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Brown, B.; Perkins, D. New housing as neighborhood revitalization: Place attachment and confidence among residents. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 749–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, R.M.; Patterson, K.L.; Yin, L.; Wu, L. Neighborhood characteristics and the location of HUD-subsidized housing in shrinking cities: An analysis to inform anchor-based urban revitalization strategies. Community Dev. 2015, 46, 632–651. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/taf/comdev/v46y2015i5p632-651.html (accessed on 17 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kazis, N.; O’Regan, K.M. The Weakness of Neighborhood Revitalization Planning in the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program: Warnings from Connecticut (19 April 2023). Journal of Land Use & Environmental Law, Forthcoming. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4423749 (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Goetze, R.; Colton, K.W. The Dynamics of Neighborhoods: A Fresh Approach to Understanding Housing and Neighborhood Change. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1980, 46, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, W.M.; Stewart, L.S. Homeownership and neighborhood stability. Hous. Policy Debate 1996, 7, 37–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Housing and Urban Development. New American Neighborhoods: Building Homeownership Zones to Revitalize Our Nation’s Communities. 1996. Available online: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/New-American-Neighborhoods-Building-Homeownership-Zones.pdf (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- Craw, M. Effects of Proximity to Multifamily Housing on Property Values in Little Rock, Arkansas, 2000–2016. Hous. Policy Debate 2023, 33, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Recreation and Park Association. Unleashing the Potential of Parks for Revitalizing Neighborhoods and Communities. 2011. Available online: https://www.nrpa.org/uploadedfiles/nrpa.org/publications_and_research/research/papers/rejuvenating-neighborhoods-white-paper.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Adeyemi, T.O. Neighborhood Revitalization—Park in Neighborhood. 2022. Available online: https://www.academia.edu (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Kaźmierczak, A. The contribution of local parks to neighborhood social ties. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Das, K.V.; Chen, Q. Neighborhood green, social support, physical activity, and stress: Assessing the cumulative impact. Health Place 2011, 17, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk-Wesselius, J.E.; Maas, J.; Hovinga, D.; van Vugt, M.; van den Berg, A.E. The impact of greening schoolyards on the appreciation, and physical, cognitive and social-emotional well-being of schoolchildren: A prospective intervention study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaxa, L.; Korthals Altesb, R.; Kupersc, R.; Monsd, B. Greening schoolyards—An urban resilience perspective. Cities 2020, 106, 102890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Jennings, V.; Cloutier, S.A. Public Parks and Wellbeing in Urban Areas of the United States. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153211. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, J.; Giles-Corti, B.; Wood, L.; Knuiman, M. Creating sense of community: The role of public space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesura, A. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubalcava, R. Environmental Justice of the City of Industry and Toxics Release Inventory Sites. Ann Arbor: Masters Abstracts International; California State University: Fullerton, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R.T. Environmental Justice and COVID-19: Some are Living in a Syndemic. 2020. Available online: https://ncrc.org/environmental-justice-and-covid-19-some-are-living-in-a-syndemic/ (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Jang, K.M.; Lourentzou, I. Exploring the limitations in how ChatGPT introduces environmental justice issues in the United States: A case study of 3,108 counties. Telemat. Inform. 2024, 86, 102085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivak, C.J.; Pearson, A.L.; Hurlburt, P. Effects of vacant lots on human health: A systematic review of the evidence. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 208, 104020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.; Odoms Young, A.; Powell, L.M.; Slater, S.J. Did Playground Renovation Equitably Benefit Neighborhoods in Chicago? J. Urban Health 2021, 98, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, B.J.L. Commercial Structure and Commercial Blight; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Quraishi, A.; Donahue, M.; Cody, B. Child Pedestrians at Risk: A Ranking of the US Metropolitan Areas; Safe Kids Worldwide: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ki, D.; Chen, Z. Walkability inequity in Los Angeles: Uncovering the overlooked role of micro-level features. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 122, 103888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist-Grantz, R.; Downing, K.; Hicks, M.; Houchin, C.; Ackman, V. Watch Me Rise: An Evaluation of Wraparound with Homeless Youth with a Child Welfare History. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 141, 106587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung-Amam, W.; Alvarez, N.; Green, R. We make us safe: Alternatives to policing in a Latinx immigrant inner-ring suburb. J. Urban Aff. 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, E. Which Comes First? Closed Schools or Blighted Neighborhoods? 2013. Available online: https://www.wbez.org/stories/which-comes-first-closed-schools-or-blighted-neighborhoods/50662c2f-4b12-4b6a-a58c-da3a043822f1 (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Tannous, H.O.; Furlan, R.; Major, M. Souq Waqif Neighborhood as a Transit-Oriented Development. J. Urban Plan. Development. 2020, 146, 05020023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lens, M. The Limits of Housing Investment as a Neighborhood Revitalization Tool: Crime in New York City. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2013, 79, 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Ranjbar, M.; Cummins, T.C.; Cummins, N.M. Safety and Inner-City Neighborhood Change: Student and Teacher Perspectives. Educ. Urban Soc. 2022, 54, 227–248. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, V.W.; Swiatek, W. AICP2 Greening, Revitalization, and Health in South Wilmington, Delaware. Del. J. Public Health 2022, 8, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Antipova, A.; Momeni, E.; Banai, R. Urban Sprawl, Blight, and the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Advances in Urbanism, Smart Cities, and Sustainability; Chatterjee, U., Biswas, A., Mukherjee, J., Majumdar, S., Eds.; CRC Press; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 263–282. [Google Scholar]

- Banai-Kashani, A.R. Toward a Synthetic Measure of Good Settlement Form. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1988, 15, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banai, R. A theoretical assessment of the ‘neotraditional’ settlement form by dimensions of performance. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1996, 23, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).