Abstract

This paper aims to track the evolution of urban morphology studies, focusing on a graphical understanding of transformation phenomena in historical and contemporary city fabrics. It points out similarities in urban morphology studies by authors like Aldo Rossi, Carlo Oswald W. Ungers, Hans Kollhoff, Saverio Muratori, Gianfranco Caniggia, and Giancarlo de Carlo. These studies developed within a supportive cultural environment, aligning with analogical procedures and anticipating the contemporary concept of urban acupuncture. Urban acupuncture denotes episodic and locally impactful interventions countering grand, self-celebratory architectural projects. These interventions are promoted both by liberal and capitalist culture as well as by socialist-inspired culture. Lastly, these interventions, promoted by various cultural backgrounds, highlight the multi-scale nature of urban morphology studies and urban acupuncture projects. Each change in form corresponds to a morphological adaptation and a redefinition of urban rules and grammar usable in projects with territorial significance. Today, enhanced by digital tools, these studies confirm insights and syntheses, presenting urban acupuncture interventions in real-time socio-economic flows and dynamics.

1. Introduction

The heuristic nature of analogical procedures that guides the formal vein of Urban Morphology studies defines the city and its fabric as a unitary system. It is where geometric epiphanies of a culture with common roots “(…) look to architectural types and urban forms as expressions of human and material evolutionary change” [1], revealing kaleidoscopic urban compositional outcomes generated by a singular phenotype. This assumes the organic notion of ‘city’. This organic nature is already embryonically intuited in early studies of Human Geography, in older studies within anthropic geography [2,3], and further in contemporary reflections between geography and architecture expressed by the Italian and French schools of urban morphology (Castex, Panerai, Muratori). It contains analogies that Levy had already highlighted in a text concerning form and morphogenesis in the Italian school: “connaissance des règles de transformation de cette forme, de sa structure, et des différents états morphologiques qu’elle peut prendre (…) à travers des processus à identifier (morphogenèse, métamorphose, anamorphose (…))” [4].

Urban regeneration is a complex operation aimed at transforming and adapting cities to current needs that can be initiated through the project of urban acupuncture [5]. The latter represents a practice that deals with urban nodes within the urban system, identifying areas and key points that serve as pivots for the entire urban organism. Morphological analysis, especially the so-called “operative” one, which has always had a multi-scale approach, proves useful in understanding the rapid changes occurring in contemporary cities. The study of the urban transformation process, which requires constant revision of intervention scales, allows for the identification of multiple architectural actions in the city comparable to acupuncture interventions. Nodes are nerve centers that, in the continuous regenerative process, have rewritten, time and again, the system of rules, established new relationships, and induced different practices. Thus, one produces other forms that overlap with a pre-existing urban design. By reorganizing that transformation process, which, through the historical and archaeological fragments and residual alignments still present in the built fabric readable in cartography, architectural acupuncture reveals itself through the study of urban morphology.

This paper considers the reflections on morphology from some masters and architectural theorists. It aims to restore morphology studies to their place in history alongside a practice of architectural design that considers both the small scale and the urban dimension1. It outlines the context in which the roots of thought are embedded and proposes several projects that reflect this approach. It presents the method of multi-scale research from the origins present in the discipline, which is particularly useful in the current definition of a project. It then presents the results of years-long research on city stratifications, highlighting the elements and systems composing it that enable the examination of the territory in diachronic and multi-scale dimensions. This approach is valuable for focusing on the “nerve centers” of the city and proposing urban acupuncture interventions.

Two particularly significant elements are approached in the text: the fragment and the urban gap. The fragment is a residue of the material memory of human action on nature, which allows us to grasp the original design and its subsequent modifications. The urban gap, due to its ‘anti-node’ nature, challenges the structure and cohesion of the city and requires its design to be redefined. Through examples of urban transformation, this paper highlights the complex dialogue between fragment and urban gap, influenced by the history, culture, and contemporary needs of the community’s culture. The urban form is the result of continuous metamorphosis, where architectural, urban, and social elements adapt to the development of historical-architectural consciousness. The architect is called to operate on this level, interpreting, preserving, or transforming the existing urban fabric to make it more suitable for modern needs. The architect must recover a place or urban setting and, at the same time, make it consistent with the current context. Finally, this paper illustrates, through design experimentation, the potential relationship between fragment and gap, showing how the anti-node can transform into a node (or nerve center) through a regenerative design action akin to acupuncture.

2. Background

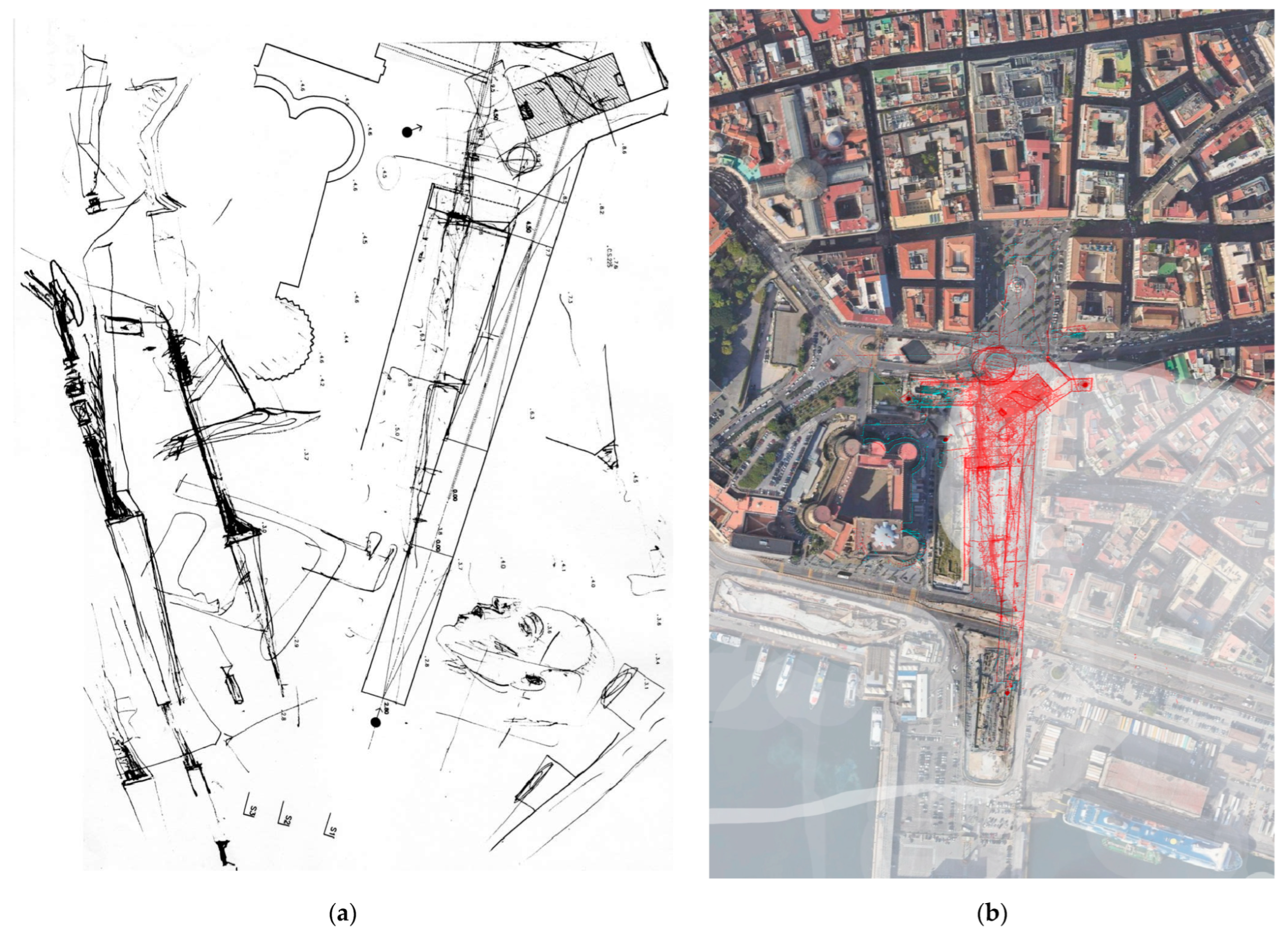

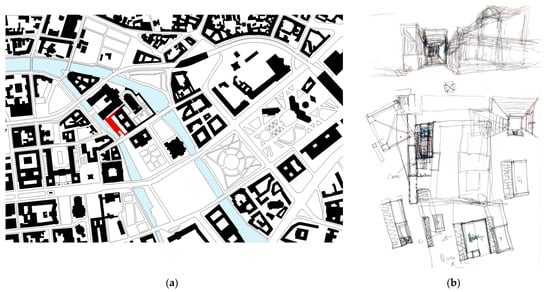

The connections between architectural design and urban intervention are already present in reflections on urban morphology by O.M. Ungers (Figure 1a). He defines ‘archipelago’ [6] as generators of nodes, parallel to the idea of a node from the Roman school of morphology [7]. Nodes are significant points, articulated in their value and highlighted by Giancarlo de Carlo—‘Squares are found where two or more roads converge, i.e., where two or more contexts intersect. Therefore, squares are also contexts, generally more complex than those that intersect to form them’. (…) ‘For this reason, squares in cities are the most significant architectural nodes and form plots: real plots like fabrics and stories’ [8]. (Figure 1b,c) Squares, focal points, flows, and densities, which specialize in architectural forms, are notions already present in morphological studies and are now found in the concept of urban acupuncture (De Solà-Morales, Lerner, Casagrande). Initially developed by Casagrande [9] on a small scale while working on a neighborhood in Taipei, the concept proposes diverting the potential energy of a place (a proto-node) by introducing new elements to achieve a reflected effect. Architectural acupuncture is a concept extended to the building and urban scale [10], where urban acupuncture is a design intervention capable of triggering virtuous mutations in discontinuity with the process. ‘At times, urban acupuncture occurs thanks to a touch of genius, like the Louvre pyramid, the recovery of Porto Madero in Buenos Aires, and the Pampulha complex by Oscar Niemeyer in Belo Horizonte’. (…) ‘In some cases, interventions occur more by chance than by design, to heal wounds that humans have inflicted on nature’. (…) ‘Over time, these wounds will create another landscape’ [10]. Architectural acupuncture uses architectural-scale interventions that reflect the territory of a city and its metropolitan area.

Figure 1.

(a) Archipelago: islands and streets by Ungers O.M. and others; (b,c) De Carlo G., central and peripheral nodes by De Carlo (public domain).

The case and ‘genius’ present in Ungers’s design research refers to Kantian’s concept of dual forms of knowledge, intuition, and invention. This formulation articulates ‘transformation’ principles capable of extracting ‘invention’ from the norms, consciousness, and culture of the place, as well as dialectical thinking to develop new forms and solutions. ‘The house enters into a dialogue with its context in a way that (…) as original as it is respectful’ (…) ‘in which the old and new strike a balance in a process of interactive continuity’ [6]. These matured in reflection on the ‘procedural nature’ of the city and the relationship between past and future, in continuity or discontinuity.

Caniggia had already begun to understand the city based on forms and solutions, both tactical and strategic, integrated between space and time2. This was especially true when reflecting on architectural design, urban organism, and territory; he anticipated Lerner’s intention [10] to draw lessons from continuities and innovations. By drawing on the essence found in the residual traces of transformations, these graphic metaphors are valuable for adjusting both local and tactical projects. They are strategic tools useful for tackling the practice of major authorial interventions promoted by both liberal capitalist and socialist-inspired cultures.

There are analogies and references of a multi-scalar nature, ‘formulas’ to design, tactical urban scenarios, and strategic territories. New or renewed relationships between solids and voids and expressions of the urban and territorial narrative embody forms of lived experience where scenarios and actors continually interact on the urban stage, unveiling metamorphoses in the landscape, the city, and the territory. New and past scenarios of the culture of the city can be reflected on to develop theories capable of grasping useful lessons in urban form and generative matrices and to define semantic expressions [11]. These are considered the ‘genetic’ codes of the formative process of the city, the one for which Aldo Rossi accused geographers of having stopped at the mere investigative aspect: ‘geographers understood everything but stopped at the most important transition (…)’ [1].

This is an ‘organic’ unity that C. O. Sauer [2], an American geographer of German origin and father of American urban morphology, had already intuited in 1925. Sauer considered the city a holistic entity that encompasses both the city and the territory, where various flows and autonomous actions intersect with influences and heteronomous imaginations, resulting over time in alternative scenarios and different urban layouts for each city [12]. It was an organic concept examined by researchers from several universities (Porto, Rome, Milan, Turin, Lisbon, Montreal, Quebec, etc.). This tendency characterizes certain studies in Urban Morphology, where the emphasis lies on seeking the outcomes of material culture through graphic formal expression (Castex, Panerai, Muratori) [13].

The forms and geometries of the built environment are crucial for shaping the identity of a place—such as plots and building arrangements—and serve as the link between space, history, and the culture of the area [14]. They constitute the tangible record of the historical layers that have molded the urban environment over centuries, providing implicit indications of the role of territorial and architectural forms in reflecting and preserving the historical evolution of a place over time [15,16].

A practical approach based on analysis of historical maps and visual representations of cities to extract information. This provides a practical interpretation of the relationships between cartographic representation and the interpretation of urban memory [17], focusing on the analysis of plot configurations as indicators of historical and territorial transformations over time [18].

Forms and arrangements (of plots) are not random but the result of historical, social, and economic processes that left traces in the spatial configuration of cities and the surrounding territory. Something more than just an aesthetic or functional aspect, interpreted to understand and narrate the history and evolution of a place over time [18].

Semantic research aims to recognize, in the language of architectural forms, the synthesis of individual and collective choices that contributed to defining the image of the city. Caniggia called this the ‘typological process’, which is the transformation of built types generating, the evolution of urban form, seeking their internal logics of growth and transformation” [19].

Studies on urban forms and volumetric and figurative mutations due to Human Geography have found interesting results in architectural design. The ‘flows of energy displacement’ [9] represent the forces that justify tensions and unveil potential urban adjustments (specializations and transformations) for the contextual reform of both inherited and contemporary cities. New building and architectural figurations overlaid on the inherited urban storytelling. New phases of a primarily continuous process, punctuated by occasional discontinuities [20], are inherent in various conceptualizations of the city [21] developed at different times under distinct sets of rules. Recognizable essences and images of cities in late-1800s maps represent a reality still linked to limited heteronomous influences and limited oppositional overlaps. Epiphanies of discontinuity, architectural compositions primarily tied to ‘spontaneous’ culture or a shared, yet limited, academic practice, are imposed and superimposed onto a city capable of assimilating any incongruous insertions or architectural mistakes.

The outcomes of research initiated in the 1980s, stemming from various studies and design experiments, reveal the initial indications of a renewed semantic reflection on the formal significance of the so-called ‘restructuring paths’, as envisioned by Caniggia and derived from the foundational concept of the matrix. The new matrix overlapped the geometric design of the older urban fabric, organized on different rules aimed at connecting other nodes, other islands, other archipelagos to define them in the words of Ungers and Koolhass. Places of ‘energy’ flows, as Casagrande defines them, are superimposed differently today and are more evident in the correct photogrammetric map. Urban and territorial design, the graphic syntax of architectural reality, features overlapping forms characterized by urban voids enclosed by new structures, buildings, or churches—new ‘design inventions’ based on fresh regulations for a revised urban and territorial arrangement.

3. Method Roots: From Human Geography to Urban Morphology

“Morphology”, from Morphologie, is the German term coined by Goethe to indicate the field of linguistics that deals with studying, through comparison, the form and structure of syntax in relation to the cultural and social components that influence and produce its metamorphosis. It was primarily used by geographers Karl Ritter [22] and Alexander Von Humboldt [23] to describe the evolution of the forms of the territory, what geographically is defined by Turri as the “plasticity of relief”, the natural substrate, the soil upon which anthropic structures rest, influencing the subsequent urban form and its continuous changes. The term urban morphology (the adjective ‘urban’ has been used since the late 1980s) is used to indicate the study of the city’s form, the urban fabric, and its components. That interpretation of the urban ‘text’ is a semantic study of forms present in its blocks and tissues composing its unit that constitutes the text of stone.

Among the many contemporary researchers who have contributed to recent studies of Urban Morphology, it is necessary to mention Whitehand, particularly for the international contribution to research through the pages of the journal “Urban Morphology” [24,25]. Whitehand was a careful researcher who developed the works of some masters such as Schlüter, Geisler, and later Conzen. Geographical reflections were particularly influenced by concepts matured within the geographic culture in Germany. Otto Schlüter, speaking of Landschaft, referred to physiognomic elements and their spatial organization (the German term Landschaft, which means both ‘landscape’ and ‘region’, combines the cultural area with its processual development) and paved the way for geographical studies contemplating human action on the territory. It is from these geographical studies that the discipline of Urban Morphology began to specialize, and, with the contribution of anthropologists [26], opened toward the subjective dimension, the existential condition of human beings in the analysis of a territory.

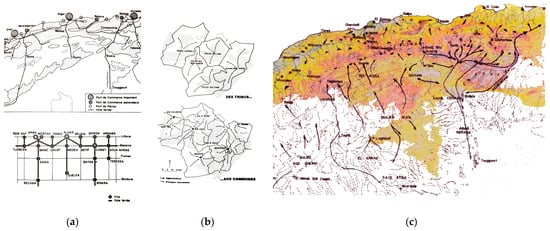

Carl Sauer defined the cultural landscape as a system of systems [2], anticipating terms now widely shared by many researchers in the discipline, placing at its core the studies of human impact on the animal and plant world. Therefore, it is difficult to establish the boundaries of the cultural area from which the study of Urban Morphology begins. The study of Urban Morphology has been interrupted and displaced several times in the last century due to socio-cultural and political events, as well as serious contaminations with other disciplines in the social and economic domains. Indirect contributions derived from Human Geography arrived in the early years of the twentieth century from historical-geographical studies of French origin from researchers such as Albert Demangeon [27]. Le Lannou was a social geographer particularly attentive to reflecting on the distribution of men and their works on the earth’s surface, as well as from another exponent of the French geographical culture. Le Lannou [28], although not questioning the almost exclusive attention to the material aspects of existence and spatial organization, reflects on the human inhabitant and how this, as a collective actor [29], perceives space, organizing it in relation to vital needs. Le Lannou’s reflections began and continued on a territory like that of Sardinia, which allowed him to address that particular relationship between man and land that of peasants who use the soil exclusively dividing the land, versus that of nomads who instead use the territory as a collective rather than individual good [29]. Two social and economic subjects, two opposing ideas of anthropic space, which have been, as they still are, the great reason for the contrast between nomads and sedentary individuals.

Another significant contribution in this area of study comes from Edmon Demolins, a controversial figure who wrote a text of a geographical nature. In this work, he intertwined places, climatic regions, and socio-economic aspects, reaching questionable considerations: he proposed the debatable idea that each territory corresponds to a specific human ‘race’ [30]. However, what is fascinating is his description of the great Erg in the African desert. This area, an immense sea of sand without divisions or human traces, borders fertile lands used only for crossing. It is a sea of sand lived in and crossed by men, like sailors making oases at their ports, recognizing themselves within an immaterial and dynamic statutory entity like the clan.

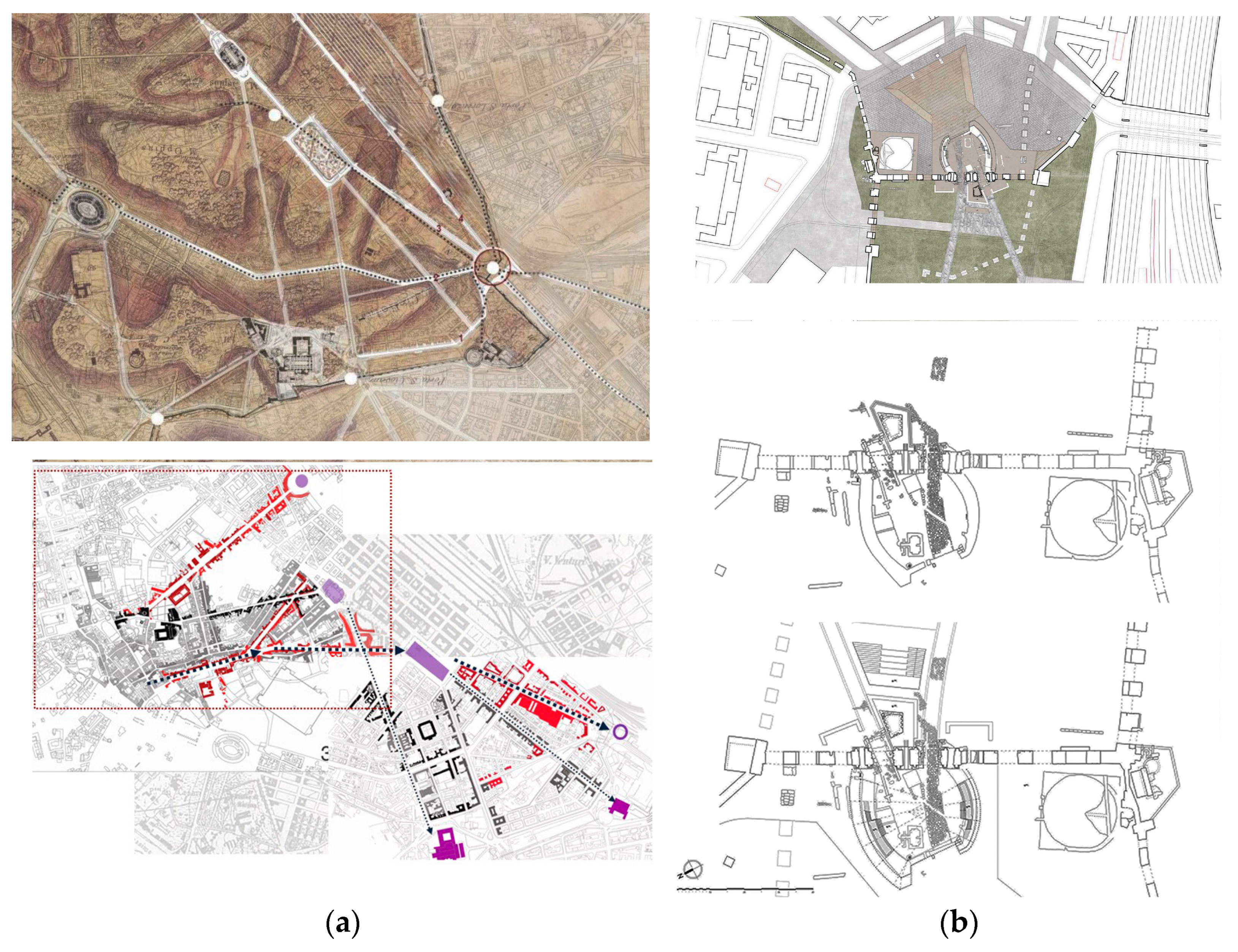

Particularly interesting, in terms of study on the form and the relationship between territory and city, is the contribution of Marc Cote [31], a relatively unknown figure (Figure 2a,b). Cote was a lecturer at the University of Aix-en-Provence. Cote examined the relationship between natural space and paths within the dynamic context of Algerian territory. Cote also understood and represented the contrast between the pre-colonial relational system and the colonial imposition3. This upheaval overturned the physio-political, administrative, and socio-economic structure of the indigenous territory. Cote graphically represented this overlay of two models, showing how centers and boundaries, settlements, and paths were closely linked to two different ideas of human space and change in the indigenous area. This area, previously based on a delicate balance between parts of the territory (Figure 2c), was altered by new alien statutory boundaries, functional only to cultural and economic dominance logic. This imbalance continues to hinder the recovery of a centuries-old relationship between man and territory.

Figure 2.

(a) Organization of main structures in the collective space (Algeria), by Cote M. (b) Administrative boundaries variations in the Hodna Region. (c) Transhumance and ethnic groups in the pre-colonial period by the author.

These pioneering geographical studies intertwine the human component with the form of the city and the territory (‘the landscape’). The spatial configuration, understood in its Anglo-Saxon etymological meaning of ‘landscape’ or ‘Landshaft’, better expresses the object of Urban Morphology studies. These delve into all forms of human work, analyzing elements, paths, the subdivision of parts, the forms of constructions, and the different structures constituting urban space [32].

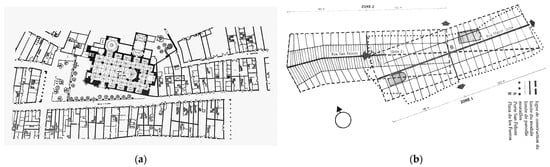

The question of the paternity of the historical-geographical approach remains a matter of controversy, with some scholars attributing its origin to the English school [33] and others to the French school. However, among the most significant contributions that have influenced the research studies of Muratori, Caniggia, and the Italian morphology school, the studies that stand out are by authors like Lucien Febvre. As early as 1922, Febvre delineated the study of the relationship between human society and the geographical context. Similarly, the long-term analyses conducted by Fernand Braudel [34] on geographical contexts and socio-economic and cultural structures have had a significant impact. Finally, figures such as George Duby [35] have enriched the historical-geographical understanding of human phenomena. Meanwhile, the Italian school deserves credit for beginning to focus on the systemic graphical elements and aspects of the global structure of the territory and the city. This was achieved starting from the concepts of typological variation and the transformation process: “connaissance des règles de transformation de cette forme, de sa structure, et des différents états morphologiques qu’elle peut prendre (…), à travers des processus à identifier (morphogenèse, métamorphose, anamorphose…)” [19,36] (Figure 3a,b).

Figure 3.

Viana. (a) Survey urban fabric by Passini J. (b) Original overlapped land subdivisions by Passini J.

Semiology of Forms

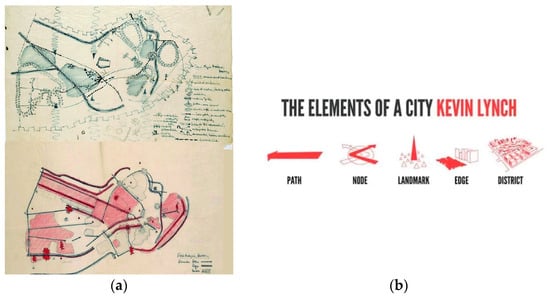

In a meeting in 1966, R. Bartres, reflecting on the descriptive potential of city forms and drawing insights from influential figures and thinkers such as Hugo, Derrida, Lynch, etc., emphasized the need to move beyond metaphors and acquire scientific interpretive tools. He considered it essential to understand what he called the signs of man on land made through the stone [37].

“In Notre Dame de Paris, Hugo wrote a beautiful, highly intelligent chapter (…) he shows, in a very modern way, to conceive the monument and the city truly as a writing, as an inscription of man in space. Hugo’s chapter is dedicated to the rivalry between two writings, writing with stone and writing on paper” [37].

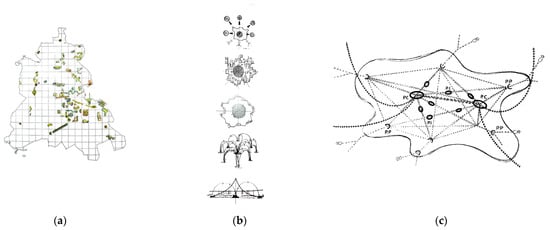

Bartres highlighted and recalled how little attention urban research had devoted to these studies, noting that only an urbanist and city scholar like Kevin Lynch (Figure 4a,b) attempted to attribute meaning to the city beyond simple metaphors. “Formal units and classes” are the terms Lynch uses to grasp what about the city could be useful in understanding the mechanisms of formation and combination, defining objects and forms that have been deemed important by numerous others approaching urban morphology studies in various capacities. These are terms that Lynch identifies in paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks [19]. These are elements of the urban narrative with stone that we can similarly consider in notes and drawings about the territory and type and also in the Italian school of morphology.

Figure 4.

(a) Boston by Lynch K. (b) The elements of a city by Lynch K. (public domain).

“These processes would probably consist of carving the urban text into units, then distributing these units into formal classes” (…) “Units that he calls paths, edges, districts, nodes, reference points. These are classes of units that could easily become semantic classes” [37].

Bartres identifies clearly recognizable elements in the city’s form, such as cadastral particles, significant elements, objects of the urban narrative, paths, boundaries, and nodes—elements of a stone text whose overlaid forms suggest stages of discontinuity that can complete the entirety of the story contained within the cartographic drawing of the city. We know that cities and architectures are sometimes produced in continuity, some other times in complete or partial discontinuity. This primarily represents the essence of architectural evolution, recorded in the city’s forms both at the urban and territorial scales.

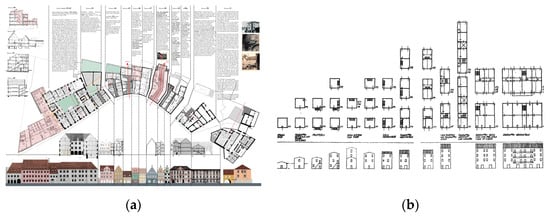

“D’une manière générale, les travaux de morphologie urbaine ont été surtout préoccupés par la notion de continuité urbaine, à travers la permanence des structures, des tracés (viaires, parcellaires …), leur rôle et leur influence dans la détermination des formes successives (processus de sédimentation): on les retrouve dans les concepts de «processus typologique» (…) chez Caniggia” [19] (Figure 5a,b).

Figure 5.

(a) Landshut: Urban form and typology analysis by Carlotti; Shiva. (b) Abacus of the typological process of the base building, by Caniggia G.; Maffei G.L. (public domain).

The discontinuities in the city’s forms are linked to rules that determine its evolution, usable for urban and territorial design, or at least its foundation. An evolution is sometimes linear, at other times interrupted by sudden leaps. The rupture of continuity parallels the cultural path, as Foucault [38] discussed with the concept of ‘rupture épistémique’ in the linear development of knowledge. An epistemic rupture can help us understand that at a certain historical moment, cities, through their codes and rules, change, creating new forms and a new order in the city’s structure [19].

4. Materials of a Formal Research

Flows, socio-economic, and cultural dynamics constitute the organic component of the city, crystallizing in architectural and urban structures. They represent a varied product of an evolving idea of architecture and city, depending on the prevalent concept of type in the lived moment. At a larger scale, even the grid composing the territorial structure varies, both in its extension and in organization hierarchies, as well as in connections that develop among hosting natural geographical systems. Cause and effect, as Rossi writes, had already been well understood by geographers and scholars of the territory.

Primarily, ‘the type’ defined by elements from Durand [39] is understood as a simple addition of parts distinguishable by function. This type, perhaps in some way, sought to respond to modernity and the proliferation of functions that buildings required for the socio-economic reality of the nineteenth-century industrial era. The new building could be expressed by aggregating different parts of traditional buildings. Furthermore, the type, this time based on elementary forms, represents the elementary base from which infinite possible variants can derive. We find them in Caniggia’s text but also in a different manner, in OM Ungers, who, starting from Rossi’s thesis, expresses in his studies and research a design tension aimed at extracting new forms and a design strategy from the morphological analysis of the city’s form capable of offering infinite possible variants to consider square, rectangle, and circle.

4.1. The Semantic Meaning of Parcel Geometry

The plot is the unit of the urban organism, active in the transformation process. Its form expresses the content. Whitehand [26], in a recent text, emphasized how the Conzen school was able to leverage the relevance of the morphological period by paying particular attention to the shape of the plot characterizing one period or type rather than another.

The plot is studied by Caniggia in the text published in 1984, ‘The Project of Basic Building’. It describes the block and its component parts as variations of an idea of fabric or building, with rules and necessary relationships frequently induced by a path and the emergencies that have established or influenced its genesis (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8).

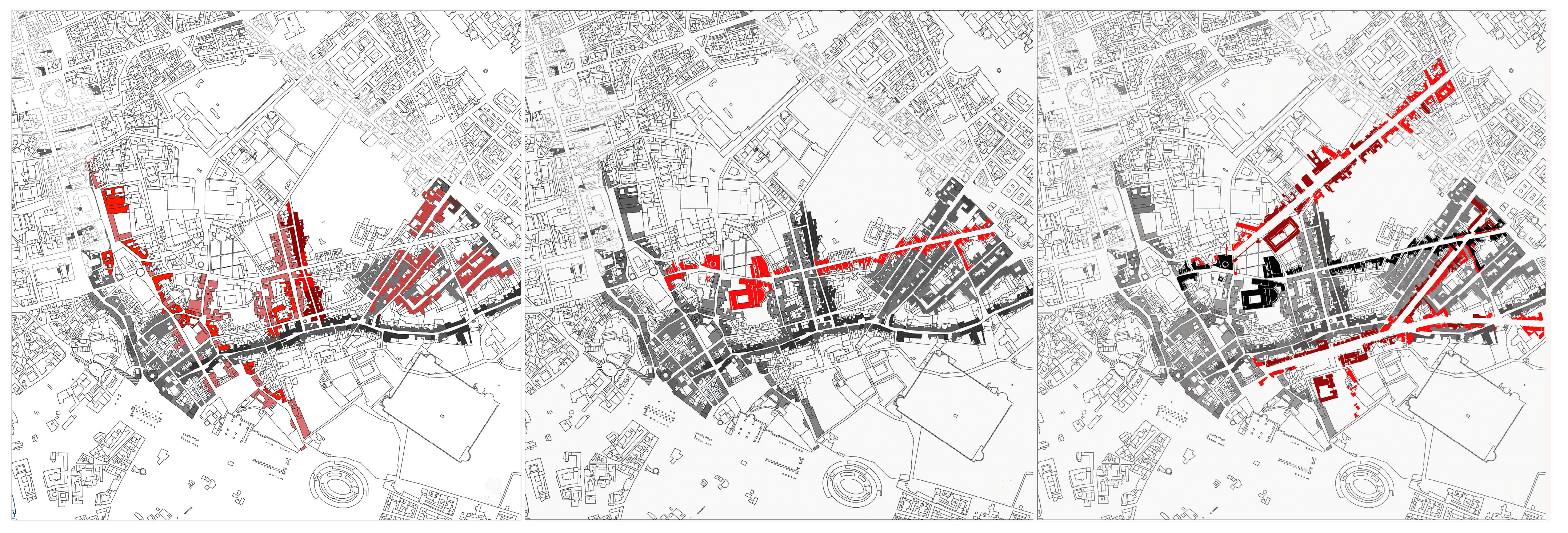

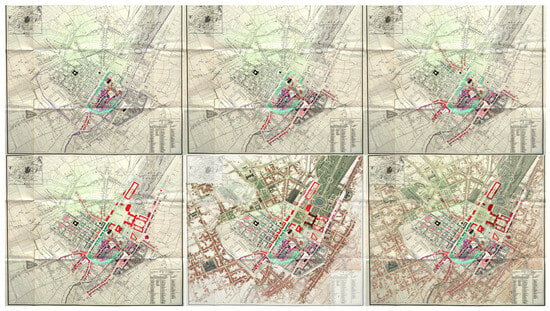

Figure 6.

Rome: Rione Campitelli e Ponte. Urban nodes and restructuring road from middle age to XX century by the author.

Figure 7.

Stuttgart: Morphological analysis from middle age to contemporary settlement. By the author.

Figure 8.

(a) Paris Renovation Paths by Aymonino C. (b) Transilvania, Medias. La rue au Moyen Age, Ouestrance by J.P. Legusy. (c) Roma, irregular blocks due to the construction of Via Giulia. By the author.

The cadastral unit, the plot, in its unity of building volume and the related area, varies within and beyond the block, sometimes due to orographic features, other times due to newly arisen organizational needs in the fabric. In 1976, in ‘Structures of Anthropogenic Space’, Caniggia, speaking of ancient permanencies within the fabric, had already begun to indicate in the diagonal paths and trapezoidal plots the indicators of the subsequent transformation of an older building substrate, more linked to special structures or orographic morphologies.

The somewhat irregular or highly irregular shape of a block or parcel will express the ultimate phase of an urban landscape fragment. Parcel geometry indicates transformations undergone [7] but also suggests the merging of multiple units and the existence of an older layer. It can indicate which elements have been added and which paths, nodes, or traces have guided the transformation process.

Although the design of the parcel aggregate generally originates from the relief and topography characterizing the natural site. Otherwise, and more often, when the plasticity of the terrain exhibits an extensive and flat nature, roads are hierarchically organized due to the intentions of those who invented and arranged the building fabric, drawing the fundamental axes and poles (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 9.

(a) Roma, Trastevere. The “viale del re” juxtaposed with the ancient fabric connects the city center with the train station by the author. (b) Roma, Trastevere (pink). The avenue of “Santa Dorotea” connects two polarities: the Sisto Bridge and Via della Lungara. By the author.

Figure 10.

Rome, ward Monti: Morphological Analysis of Fabric: Overlay of new roads during the XIX century. By the author.

To a discerning eye, those seemingly inexplicable traces of masonry from the pre-existing fabric, hidden within the complexity of the current cadastral drawing, cannot escape notice. Those are remnants of minor constructions, mainly consisting of elementary structures (single-cell or double-cell), whose private property prevented them from being transformed.

4.2. Connection, Node, and Pertinent Strip

From its origin, the cadastral parcel maintains a close relationship with the path. It becomes a matrix when specific morphological, economic, and environmental conditions allow for their anthropic structuring. Proximity to a crossroads of paths establishes hierarchies with other paths, leading to subsequent specialization (plazas or buildings).

The foundational path, like the primary paths, establishes the initial rules for the city’s design. A series of complex factors (distance from the node, quality of the nodes, etc.) regulate the development and subsequent design of the built environment along the relevant strips of the paths, and the resulting form will be what the building elements require. The formation and specialization of certain parts of the built fabric (construction of special buildings: palaces, convents, churches, etc.), modifying the value of the nodes, often require new paths (sometimes designed counter to the grain), and they produce trapezoidal shapes for the lots in the building fabric. Elements and structures must necessarily reconcile, as Quaroni [40] aptly describes for the urban project of Via Giulia during the pontificates of Nicolo V and Pope Perretti, with an existing design: “in the Fontanian idea” (…) “there is a design seeking a reinterpretation of the city that already existed (the main poles were already marked in history) according to a new, broader, and architectural vision of the entire urban fabric”.

4.3. The Osmotic Relationship between Fabric and Building Type

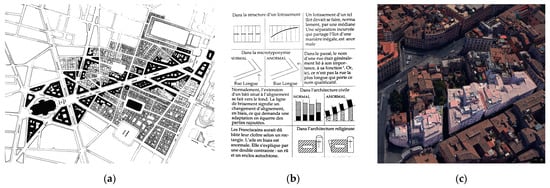

An osmotic relationship links the basic building fabric to the special building, commonly referred to as a palace. It represents a continuous genetic mutation of the building within the urban fabric, altering the rules for aggregating basic units within the building fabric proposing different, sometimes simpler, or more complex alchemies over time. The transition to a special architectural unit is generally determined during the procedural history of the architectural type through a simple and paratactic juxtaposition of building cells (Figure 11a,b).

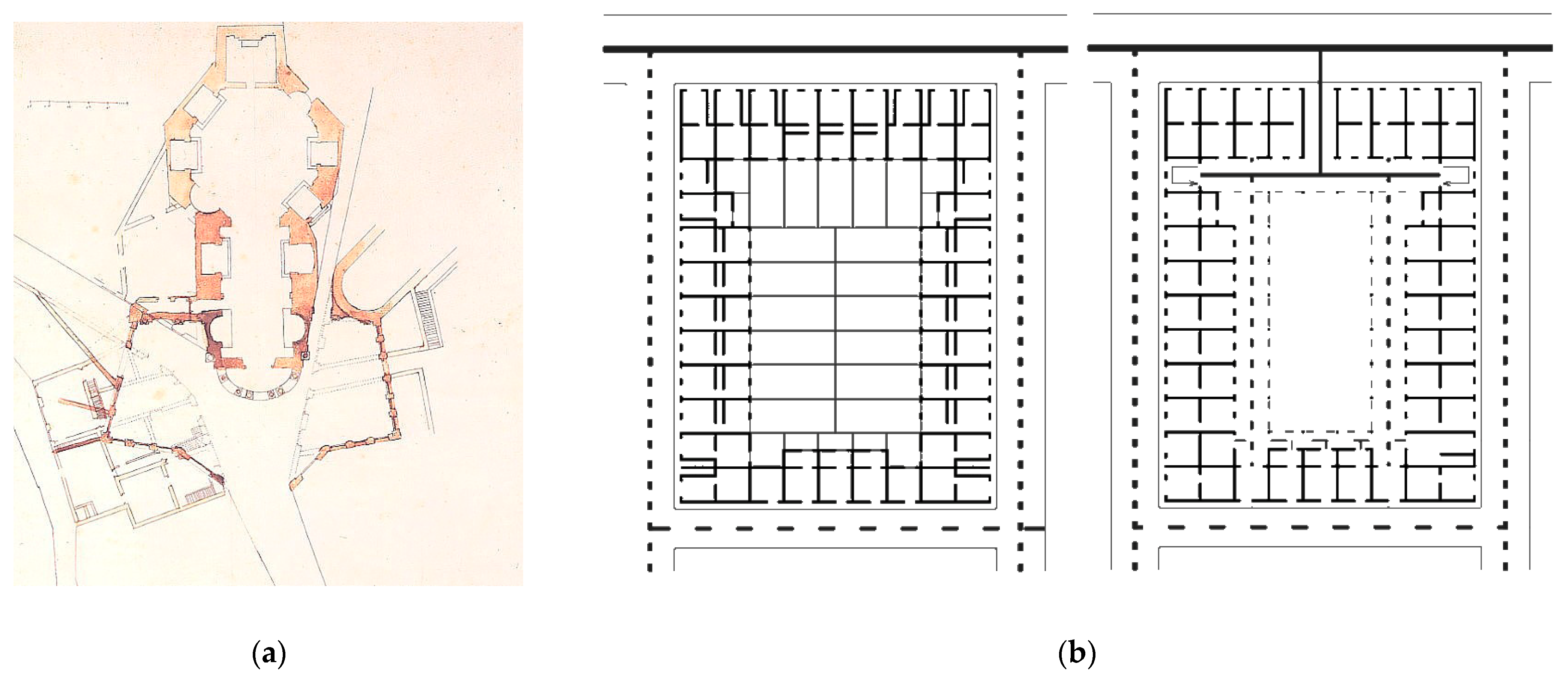

Figure 11.

(a) Roma, Santa Maria della Pace. Project of the square (public domain). (b) Relationship between row houses block and palace (public domain).

They align linearly along a path, on the inner perimeter of a sacred enclosure’s peristyle, or organize within a block along the perimeter of an empty space (courtyard) following a diachronic order and succession borrowed from the same rules that determined the distribution of lots and buildings in the urban block. This evolution is commonly found in the historical fabric of many cities, often coinciding with changes in residential use and the urban role the architectural organism plays in the location. This initial metamorphosis is often followed, particularly in continuously inhabited urban centers, by a more complex one that could metaphorically be described as the crystallization of the basic building fabric. Its serial character morphs into a new organic architectural unit, where external paths become internal, following a hierarchical sequence borrowed from the compositional rules of the building fabric. This transformation can remain open or be enclosed, altering the original distributive nature of the building into an architectural expression more akin to a basilica-type structure.

This continuous and complex mutation of the fabric and building type reflects within the building fabric itself, which contains and envelops it. The formation of a palace establishes a significant point within the urban system. It includes new buildings and paths, all with different relationships between parts and the whole. This progressive mutation demands a hybrid rethinking between type and fabric in the moment of design. The parliamentary palace is like the prince’s palace, a special building among special buildings. Just like Torino Palazzo Carignano in its seventeenth-century transformation, the “government” building requires specific spaces and rooms acquired from the fabric. Over time, it gains unique dimensions and complexity, imposing itself on urban space. Or additions that flip the facade and hierarchies in the urban building fabric, as seen in Turin’s Palazzo Madama. Symmetrical and specular doublings, duplications, and specializations are elements of a metamorphic game that leads the basic fabric to crystallize into the palace, establishing organized nodal spaces and adding relevant spaces to redesign a new order within the city.

5. Discussion: Urban Acupuncture in Morphological Studies

Imagined as the final frame of a movie, the shape of the contemporary city appears as the ultimate chapter of its architectural narrative, like an “urban text”, a collective and dynamic “writing” that fades just an instant after another new transformation takes place.

Houses, streets, buildings—all elements composing the city—physically express, in three dimensions, the life and relationships between people. Stories and events within the city are recorded with ink on paper, documenting what has become inherited. Each “discrete unit” (building particle) represents, through its form, a part of the narrative, an outcome of mediations between what has been inherited and what has more recently been produced. However, what has been transformed, partly or entirely erased, can only be imagined based on the form it had. Yet, we can reconstruct it by interpreting those residual graphic traces, ancient and modern, that still linger in the geometric marks on cartography, capturing the essence of time and the spirit of the people’s culture.

Contemporary topographic maps, repositories of the total reality of human and architectural events, can be a mentor for the future through those graphic signs, sometimes jealously guarded within the building fabric, in the shapes, in the residual elements and particulars of a material history, devoid, however, of the contour that characterized their essence. They are discrete units, signs of a past sometimes organized on premises diametrically opposed and imagined by modern society.

The complexification of the territory and the city has, over time, generated increasingly intricate forms, often identifiable solely by their irregularity. These are geometries that modern culture is adept at representing and that today, we can attempt to interpret in semantic significance to understand the rules that have determined other forms in its past.

A correlation between expression and content, form and meaning, reveals how meanings and rules emerge with each change in form. It underlies a shift in significance, a change in scale, a new morphological adaptation, and, consequently, a redefinition of “urban rules”.

The cadastral map, metaphorically assumed as the city’s narrative, encompasses all urban forms that have continuously innovated it, “adjusting” and updating it until the present, “(…) the form of expression or urban form can be understood as the spatial language through which the content form is manifested” [19].

Forms, meanings, and continuous and discontinuous processes coexist in the concepts underlying interventions of urban acupuncture: “We know that planning is a process. As good as it may be, it doesn’t determine immediate transformations. It’s almost always a spark that starts an action, which then propagates. And this is what I call good acupuncture. True urban acupuncture” [10].

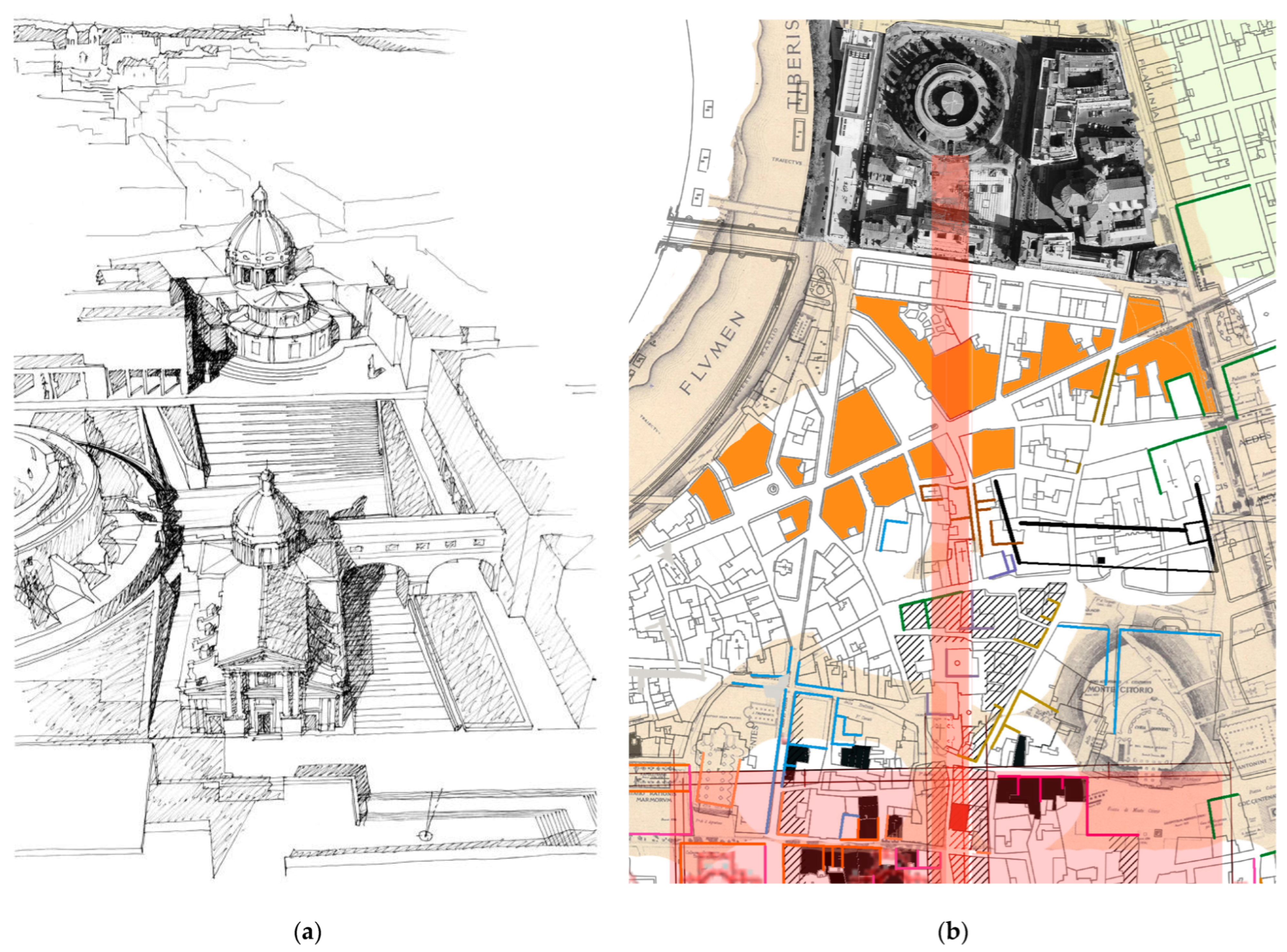

In line with processes and events that change its course, the foundation of urban acupuncture is analogous to the concept of process in urban morphology and interventions that have understood the significance and role of the part within the whole. Profiting from corrections to heal wounds is what morphological studies seek to explore through the study of form. However, not all interventions manage to achieve this, lacking that touch of genius. Others, on the other hand, seem to have both this touch and the ability to meet the goals set by morphological studies. One such project led by Francesco Cellini at the Augusteum managed to blend different historical layers of the city of Rome with the demands of the most recent contemporary layer (Figure 12a,b). This was achieved through connecting pathways, scalar connections that reinterpret the ancient by inventing the new. The city, in its continuous transformation, preserves in the forms of its original structure the imprint of its future, often linked to the original plastic conditions of the soil that continue to suggest tactical and strategic interventions, acupuncture points characterizing new points of an archipelago [10].

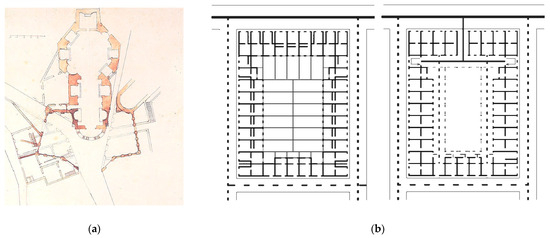

Figure 12.

(a) Augusteum: Requalification Project for Piazza Augusto Imperatore: The project and the historical superimposed layers by Cellini F. (b) Project and several phases of urban transformation. By the author.

The project, which was the outcome of a competition in 2006, aimed to restore the archaeological area to the contemporary city, engaging in a dialogue with the preexistence in a way that respects the “archaeological fragment”, bridging the gap to reintegrate it into the urban project of the area, enabling users to comprehend and live within the space, rejuvenating the area and the entire urban district. It could be described as a tactical and strategic project and an acupuncture intervention simultaneously. It is an urban project that looks at the larger scale, that of the entire urban space and the extended territory.

The first phase of the competition, concluded in 2014, focused on the arrangement of the lowest level of the archaeological stratum, while the second, yet to be completed, dealt with arranging the area surrounding the building, reinterpreting the relationship between historical memory and the contemporary city.

A different but illustrative example of how a modest intervention can impact the entire urban fabric is that by David Chipperfield Architects for the reconstruction of the Neues Museum in Berlin, in collaboration with Julian Harrap (Figure 13a,b). In this case, the goal was to repair the damaged sections, bridging the urban void, perhaps intentionally left to divide the city in two. The masterful and unique effort by Chipperfield D. and Schwarz A. when imagining the entrance to the museum complex in Berlin is contained and calibrated within the compositional grammar of nineteenth-century masters (Schinckel, Stulher, etc.) for a complex building meant to celebrate the weight of civilization.

Figure 13.

(a) Chipperfield D. & Schwarz A., Berlin Neues Museum Urban Planimetry. (b) Sketch of the project. By Schwarz A.

Born on Museum Island (Spreeinsel), next to Schinkel’s Altes Museum of 1828, the Neues Museum emerged between 1841 and 1859 under the direction of Stüler, who aimed to create a ‘sanctuary of arts and sciences’. Partially destroyed by Allied bombings during the Second World War, it left a void in the heart of the German capital that would only be filled after the reunification of 1989. It was not until 1999, after Chipperfield was appointed as the museum’s architect, that the building would be recognized as a UNESCO heritage site. The new project, completed in 2009, will be a multidisciplinary operation that will bring together the disciplines of restoration, conservation, and reconstruction, presenting them in a contemporary language that encompasses all their components [41]. A new gallery connects the museums together, the Neues Museum with the Pergamon just behind Schinkel’s Altes Museum. However, the intervention is more than that; it holds a larger-scale tension, engaging the city and aiming to redesign its center. As Alexander said in a conference held in Rome in 2020 (ISUFItaly conference), “The reunification of East and West Germany and particularly the two parts of the city of Berlin provided the opportunity to reestablish the unity of the city. On the Museum Island, the reconstruction of a wing of the new museum (Simon Gallerie) offered the possibility (by Chipperfield & A. Schwarz) to restore unity to the museum complex on the island and to the city”. This tactical and strategic intervention, an acupuncture similar to Lerner’s, had the value of reinventing an ideal center for the city.

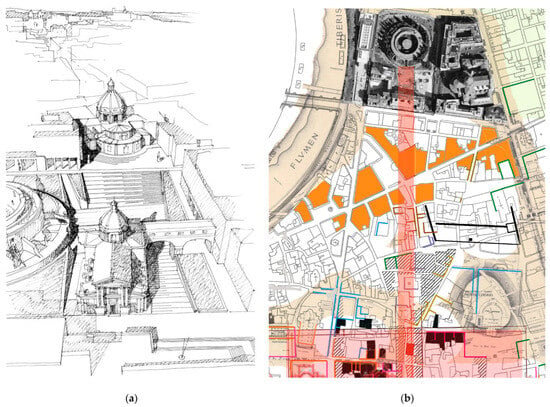

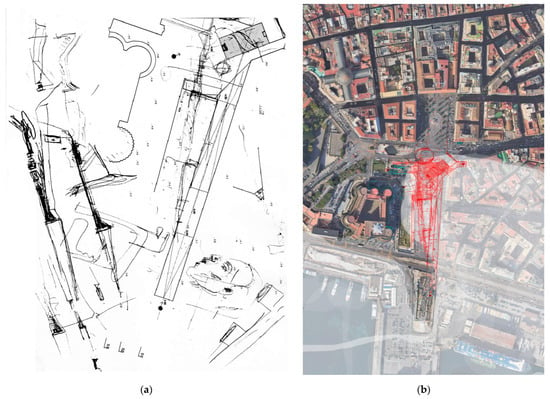

Different but equally expressive of an acupuncture design tension, halfway between urban design and landscape rewriting, is the one by Siza and Souto de Moura for the Municipio station in Naples, still unfinished, which has united fragments of Naples’ history (Figure 14a,b). A complex project where, once again, the fragment, the gap, and urban regeneration find a masterful synthesis in the redesign of a node belonging to the city system and through the metro station to the wider territory. “(…) a project of ‘historical continuity’. Not figuratively, but in the way of working. Christian architects of the Middle Ages, for example, used to take Roman columns to build churches. Well, we use archaeology not as a field of investigation, not as material for scientific contemplation, but as material useful for our projects” [42].

Figure 14.

(a,b) Projects: Sketches for the “Piazza Municipio” Metro Station by Siza A. “But Naples is not only what is seen, in glory or in degradation. One can almost feel, beneath one’s feet, the breath of an invisible or hardly visible world that has been building the present city for many centuries. An enormous and fragmented foundation of many layers, materials often overlapped, placed by people from different regions and religions. Thus, magnificent monuments emerge, which sometimes men uncover while digging. Such accumulated matter conditions and directs what is being built today” Laurea Honoris Causa dell’Università Federico II d\i Napoli|2004 Discorso Letio Magistralis by Siza A. (Public domain).

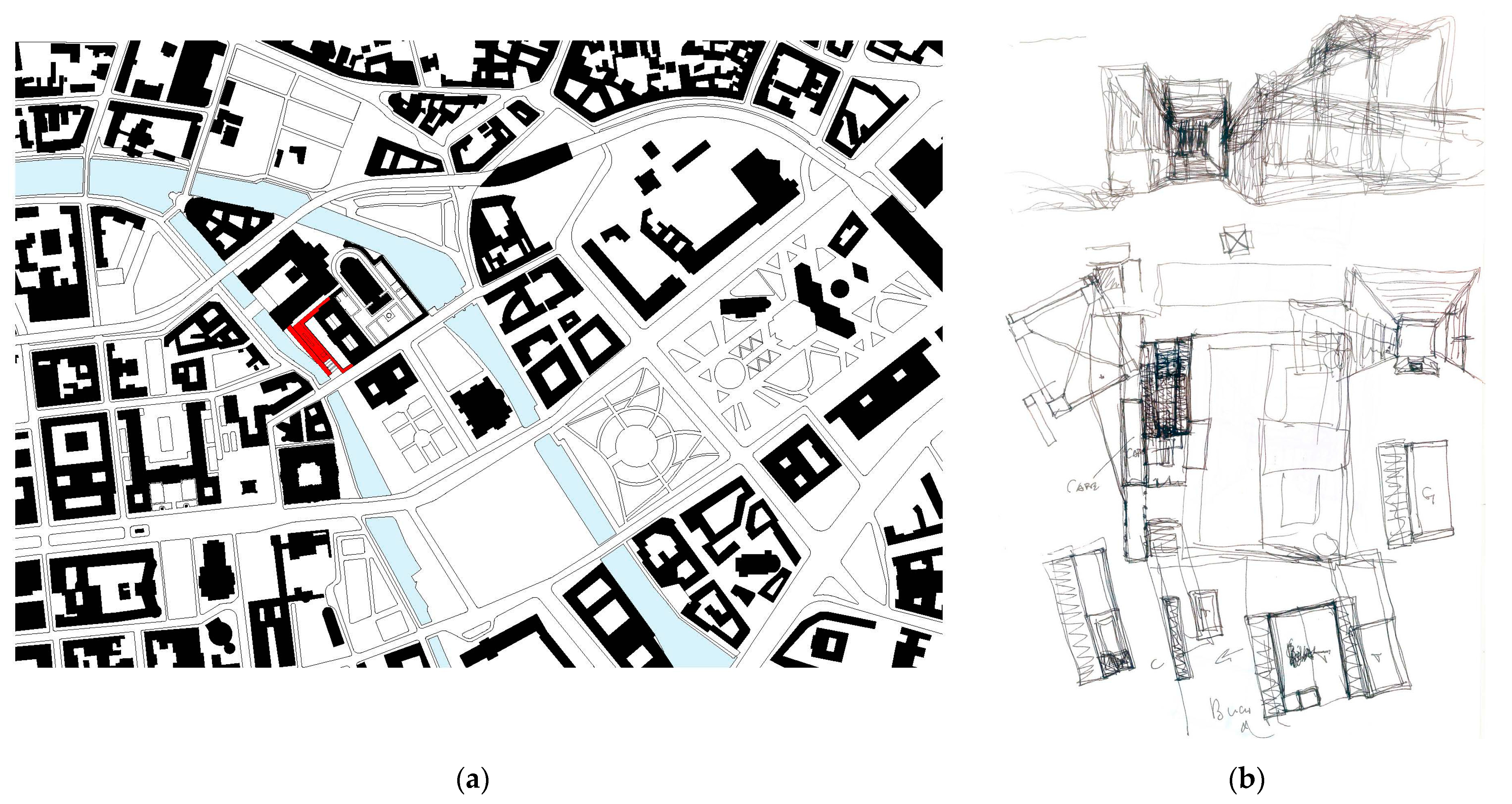

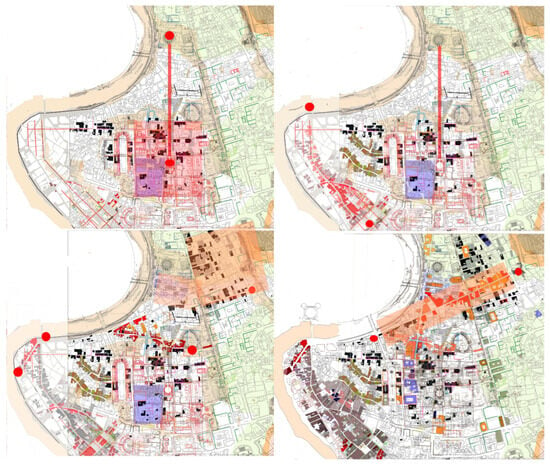

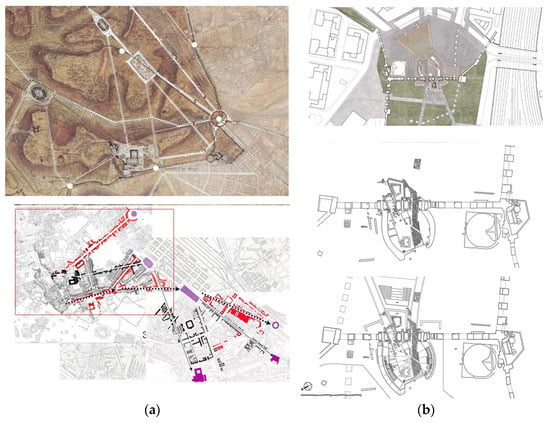

Finally, I would present the experimental design work conducted for a master’s thesis, which I tutored, along with two colleagues, in the field of restoration, focused on the objective of transforming a marginal urban space into a central hub through an innovative approach to design: urban acupuncture. Specifically, our focus was on the revival of Porta Maggiore in Rome, an area long considered an urban boundary (Figure 15 and Figure 16). Through the study of urban morphology, we highlighted the potential of this location, which has gradually but steadily evolved into a vital convergence point within the Eternal City since the unification of Italy. The design experimentation was centered around the idea of infusing this space with the typical vitality and centrality found in Roman squares. Through careful analysis of the historical and urban context, we worked to conceive a project that not only addressed contemporary needs but also valued and respected the identity and history of the site, distinguishing the area within the walls from that outside the city’s perimeter.

Figure 15.

Roma Porta Maggiore. Design Studio: Proposal for conservation and transformation of the urban node by Carlotti P., Jiang J., Senna P. (a) Morphological analysis. (b) Design proposal (up) and survey and proposal (down). By Carlotti P., Jiang J.; Senna P.

Figure 16.

Roma. Porta Maggiore. Design Studio, final project of the thesis: Proposal for transforming urban borders into urban nodes. Render by Jang J., Senna P.

6. Conclusions

Urban acupuncture and urban regeneration represent some fundamental tools for the reinterpretation and transformation of the urban fabric. Nevertheless, in the analysis of urban morphology, we can understand the rules that have guided the formation and evolution of cities, allowing us so to intervene in a respectful and innovative manner. In particular, the archaeological fragment and the urban void emerge as key elements in this reading process, acting as critical nodes that require healing action [43,44].

The examples presented in the article demonstrate how a well-designed architectural intervention can trigger a regeneration process, balancing respect for history and local identity with the necessary innovation to meet contemporary needs. In this sense, the architect is not only a designer but a true urban healer, capable of healing the wounds of the urban fabric and triggering processes of positive transformation.

These examples broaden the perspective and vision of urban acupuncture, integrating it with what is now defined as micro-urbanism. The idea of acupuncture interventions containing an urban planning vision gives substance to the perspective proposed by Lerner of integrating strategic building realization into the concept of acupuncture.

The tools and investigation methods of the morphology school, particularly those of Italian origin, have embryonically shared this approach to the project. So, interesting perspectives, from a design standpoint, may develop in research through the comparison of historical cases and contemporary interventions [45].

Finally, I presented the experimental design work conducted for a master’s thesis, which I tutored, along with two colleagues, in the field of restoration, focused on the objective of transforming a marginal urban space into a central hub through an innovative approach to design: urban acupuncture. Specifically, our focus was on the revival of Porta Maggiore in Rome, an area long considered an urban boundary. Through the study of urban morphology, we highlighted the potential of this location, which has gradually but steadily evolved into a vital convergence point within the Eternal City since the unification of Italy. The design experimentation was centered around the idea of infusing this space with the typical vitality and centrality found in Roman squares. Through careful analysis of the historical and urban context, we worked to conceive a project that not only addressed contemporary needs but also valued and respected the identity and history of the site, distinguishing the area within the walls from that outside the city’s perimeter.

Despite both areas being within an urbanized context, we deemed it important to cherish their memory. Therefore, within the walls, we proposed paving and the reconstruction of the gate, which was demolished in the nineteenth century. Externally, we deemed it crucial to enhance the fragment of the imperial city through its integration with a green buffer zone, seamlessly blending with the urban project of the city walls park, extending from Porta Maggiore to Piazza S. Giovanni. The result was a project that not only aimed to physically transform the area but also revitalize the urban contest, transforming Porta Maggiore from a boundary point into an iconic Roman square and a place of encounter, culture, and social life.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

I declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The city is regarded as a multi-dimensional sensitive organism where energies interact, a living environment. |

| 2 | Caniggia and Maffei began to connect geometric forms like the “path of restructuring” of the urban fabric—parcels and blocks—to urban events and parts of a graphic narrative of urban history. |

| 3 | Almost all colonial logic between the 1800s and the end of the Second World War (and perhaps even today—considering Somalia and Afghanistan, the two countries previously inhabited predominantly by nomadic populations until a few decades ago) was based on the “replacement” of the territory’s culture, often the source of wars and improper land appropriations. |

References

- Rossi, A. Architettura della città; Saggiatore: Milano, Italy, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C.O. The Morphology of Landscape; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C.O. Land and Life: A Selection from the Writings of Carl Ortwin Sauer; Leighley, J., Ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, A. Forme urbaine, tissu urbain et espace public. In Morphologie Urbaine et Parcellaire; Merlin, P., Ed.; The Vincennes University Press: Paris, France, 1988; pp. 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Acierno, A. Agopuntura e urbanistica tattica nella rigenerazione delle città. TRIA 2019, 12, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ungers, O.M.; Koolhaas, R.; Riemann, P.; Kollhoff, H.; Ovaska, A. The City in the City. Berlin: A Green Arcipelago; Marot, S., Hertweck, F., Eds.; Lars Muller Publishers: Baden, Switzerland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Caniggia, G.; Maffei, G.L. Composizione Architettonica; Marsilio: Florence, Italy, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, G. Nelle città del mondo; Marsilio: Venice, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande, M. Urban Acupuncture. 112, GA Document. 23 November 2010, pp. 76–81. Available online: http://thirdgenerationcity.pbworks.com/f/urban%20acupuncture.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Lerner, J. Acupuntura Urbana; Editora Record: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Munford, L. La cultura delle città; Ed di Comunità: Milan, Italy, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande, M. Urban Agopuncture Revivifyng Out Cities through Targeted Renewal. Kyle Miller MSIS. 1 December 2011. Available online: https://kylemillermsis.wordpress.com/2011/09/25/urban-acupuncture-revivifying-our-cities-through-targeted-renewal/ (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Muratori, S. Studi per una Operante Storia Urbana di Venezia; Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato: Rome, Italy, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci. Paesaggio Ambiente Architettura; Electa: Milan, Italy, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lowental, D. The Past Is a Foreign Country; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Farinelli, F. I segni del mondo. Immagine cartografica e discorso geografico in età moderna; La Nuova Italia: Florence, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, A. Formes urbaines et significations: Revisiter la morphologie urbaine. Espaces Et Cocietés 2005, 122, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniggia, G. Strutture dello spazio antropico; Uniedit: Florence, Italy, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Rykwert, J. L’ idea di città. Antropologia della forma Urbana nel Mondo Antico; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, C. Étude De La Terre Dans Ses Rapports Avec La Nature Et Avec L’histoire De L’homme; Paulin Editeur: Paris, France, 1835. [Google Scholar]

- Von Humboldt, A. A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe I; Henry George Bohn: London, UK, 1858; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Larkan, P.; Conzen, M.P. Shaper of Urban Form; Routçedge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Conzen, M.P. The study of urban form in the United States. Urban Morphol. 2001, 5, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy-Strauss, C. Tristes Tropiques; Union Générale d’Editions: Paris, France, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Demangeon, A. La Picardie et les régions voisines: Artois, Cambrésis, Beauvaisis; Librarie Armand Colin: Paris, France, 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Lannou, L. La Géographie Humaine; Flammarion: Paris, France, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Turri, E. Antropologia del Paesaggio; Ed. Comiunità: Milan, Italy, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Demolins, E. Les Grandes Routes des Peuples, essai de Géographie Sociale: Comment la Route crée le Type Social; Firmin Didot: Paris, France, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Cote, M. L’Algérie ou L’espace Retourné; Flammarion: Paris, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, P. Morphologie Urbaine at Parcellaire; CNRS: Paris, France, 1988.

- Oliveira, V.J.W.R. Whitehand and the Historico-Geographical Approach to Urban Morphology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Braudel, F. il Mediterraneo e il Mondo Mediterraneo Nell’epoca di Filippo II; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Duby, G. L’économie Rurale dans l’Europe Médiévale: France, Angleterre, Empire (IXe-XVe Siècles); Editori Laterza: Bari, Italy, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R. Semiologis e Urbanistica; Il Centro: Florence, Italy, 1967; Volume 10, pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Focault, M. Les Mots et les Choses; Editions Gallimard: Paris, France, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, J.N.L. Précis des Leçons d’Architecture Données à l’École Royale Polytechnique; Ecole Polytechnique: Paris, France, 1809. [Google Scholar]

- Quaroni, L. Immagine di Roma; Laterza: Roma, Italy, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Nys, R. David Chipperfield; Verlag der Buchhandlung König: Koln, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moscatelli, M. Eduardo Souto de Moura: La vita degli edifici prima, durante e dopo. Giornale dell’Architettura, 3 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Carlotti, P. Ragionamenti morfologici sulla città. U+D Urbanform Des. 2021, 16, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Carlotti, P.; Oliveira, V. I concetti di percorso di ristrutturazione, fascia di pertinenza e frimge belt nellanalisi del tessuto urbano di Porto. U+D Urbanform Des. 2020, 13, 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cody, J.; Siravo, F. Historic Cities: Issues in Urban Conservation; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).