Abstract

Cultural landscape security is important to national spatial and cultural security. However, compared with the many achievements in the study of ecological security, transregional cultural landscape security research lacks enough attention to match its importance. In the context of advocacy of ‘connecting practices’ between nature and culture in the field of international heritage conservation, this paper developed an approach for constructing transregional vernacular cultural landscape security patterns and identifying the key protected areas. A method is put forward based on the case of the Yangtze River Delta Demonstration Area, one of the fastest urbanizing regions in China, and included the following three steps: (1) analyze the core values of the transregional vernacular cultural landscape from a long-time series and multi-scale perspective; (2) integrate ecological security assessment and value security evaluation by combining qualitative with quantitative methods; (3) build a comprehensive vernacular cultural landscape security pattern to identify key protected areas and develop a zoning and grading conservation strategy toolkit. The results proved that our new method could effectively build a cross-regional network of integrated spatial and functional relationships between the historical cultural and natural landscape and have great significance in improving the level of transregional territorial spatial governance.

1. Introduction

The ideas from Relph’s sense of place, Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology and Henri Lefebvre’s importance of everyday life inspired J. B. Jackson and D. W. Meinig to focus on the common values of ordinary landscapes [1]. J. B. Jackson linked “Vernacular” with “landscape” in his book Discovering the Vernacular Landscape. Through the comparison of the political landscape and residential landscape, he gave a “vague” concept of vernacular landscape [2]. The vernacular landscape is the product of constant adaptation and conflict. It adapts to the novel and complex natural environment and coordinates the people who have different views on the environmental adaptation mode. It has the obvious characteristics of “grassroots”, “daily”, “mobility”, “temporality” and “adaptability”. The vernacular landscape includes the built environment, agricultural and natural landscapes and the inhabitants [3], and is essentially a cultural landscape [4]. These “every-day or degraded landscapes as well as those that might be considered outstanding” are all important parts of community identity and local culture [5], and are of great significance to local environmental management decision-making and sustainable development.

However, global climate warming and rapid urbanization seriously threaten the safety of the vernacular cultural landscape [6,7]. The key to threatening the safety of the cultural landscape can be understood as the fundamental decoupling of social culture and ecological subsystems in the cultural landscape [8]. The cultural landscape contains rich evidence of our society and history, and it is easy to make viewers associate it with the value of heritage. The heritage landscape includes not only tangible and material things, but also the spiritual inheritance of broader values and customs, which can inspire us to establish links with the “past” and social history, thus forming community values and social identities [9]. Many scholars have tried to conduct corresponding landscape security studies based on ecological theoretical approaches in terms of landscape security patterns [10], ecosystem services [11] and vulnerability assessment [12]. Compared with the booming studies on ecological security patterns [13,14,15], the rare concerns about cultural landscape security pattern research do not match their importance [16]. In recent years, a series of academic studies have been carried out in the field of international heritage around the interrelation of natural and cultural values [17,18]. The clarification of nature–culture keywords such as “biocultural”, “resilience” and “traditional knowledge” also provides a conceptual consensus for the development of a “connecting practice project” [19]. Based on the above concepts, this study attempts to establish a more holistic framework for the security pattern of the vernacular cultural landscape and explore the possibility of applying it in practice.

The area of the Yangtze River Delta is one of the fastest urbanized regions in China. In the context of China’s reform and innovation to explore regional integration, balanced and high-quality development, the Chinese government decided to establish the Yangtze River Delta Ecological and Green Integration Development Demonstration Area (hereinafter referred to as the demonstration area) in 2018. The demonstration area breaks the boundaries of administrative divisions. It takes the new demonstration of world-class quality of human settlements and the new benchmark of eco-green high-quality development as its development vision. There is a wide-area ecological water network connecting many scenic heritage resources and ordinary landscapes, such as the vernacular settlements, characteristic pastoral scenery and agricultural polders, which are steeped in intangible cultural practices such as local traditional scientific knowledge and practical wisdom of resource management [20,21].

However, the previous studies of territorial spatial resource protection always adopt the evaluation system of resources and environmental carrying capacity and spatial suitability, which mainly focus on the value assessment of natural resources and the ecological environment [22,23,24]. The planning practice mainly focuses on simple environmental governance, ecological protection and restoration, and takes it as an effective way to achieve the goal of high-quality ecological green development. Although this resource-oriented mathematical evaluation method guarantees the bottom line of ecological security, it separates culture from nature and ignores the two-way mutual construction, which is an inseparable relationship deeply embedded in the local landscape. Therefore, the correct evaluation of the safety of vernacular cultural resources related to nature is directly related to the ultimate protection efficiency, as well as the harmonious and healthy development of human settlements and ecological space in the region. In addition, under the influence of climate warming and urbanization, the vernacular cultural landscape in the demonstration area faces huge security challenges. This problem and situation is also internationally representative and typical.

Therefore, this study aims to embody the new concept of an ecological green focus and broaden the thinking of environmental resource protection from the perspective of the integrity of the natural cultural ecosystem. The study takes optimizing the safety of the local cultural landscape as an effective way to realize the high-quality development of an ecological green focus. We have established a methodology for the security pattern of the transregional vernacular cultural landscape for multi-dimensional value conservation. Additionally, we chose the demonstration area as the research area to explore the possibility of implementing this approach. The significance of this study is that the key protection areas can be identified by the security pattern classification. It also helps to determine the priority of the protection and management of cross-regional vernacular cultural landscapes. Furthermore, the corresponding requirements for the protection and utilization of land and resources should be formulated in a scientific and reasonable way as a whole.

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Study Area

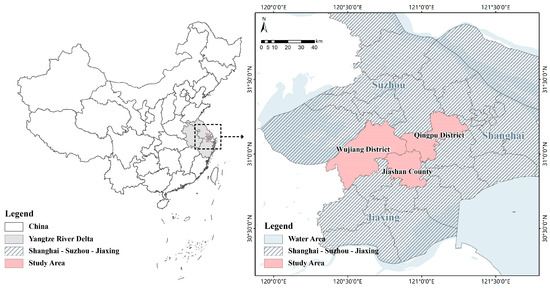

The demonstration area comprises the Qingpu District of Shanghai, the Wujiang District of Suzhou City, Jiangsu Province and Jiashan County of Jiaxing City, Zhejiang Province (Figure 1), with a total area of about 2413 square kilometers.

Figure 1.

Location of the demonstration area.

2.2. Data Sources

The study summarized and collated the relevant data and information in the demonstration area and divided them into two aspects: nature and culture [25,26,27]. Additionally, we adopted GCS_WGS_1984 as a geographical coordinate system and carried out geographical visualization of these data in ArcGIS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the datasets utilized in this study.

2.3. Methodology

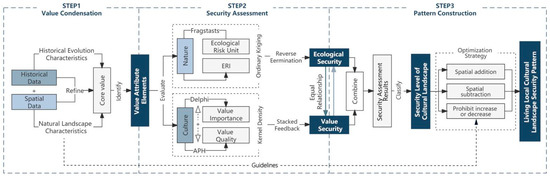

The framework of constructing transregional vernacular cultural landscape security patterns was divided into three steps: cultural landscape value condensation, transregional cultural landscape security assessment and pattern construction (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The framework of the transregional vernacular cultural landscape security pattern.

2.3.1. Step 1: Concise Cultural Landscape Core Value System

First, based on the various types of natural substrate data of the demonstration area and the understanding of polder types, the whole natural landscape features in the area were refined.

Secondly, we sorted out the historical geographic changes in the transregional landscape by combing through local chronicles, historical maps and other relevant documents. Additionally, we then divided the periods of historical characteristics. After that, the core values of the local cultural landscape in the area were systematically revealed and we identified the value attribute elements. Additionally, according to the dominant attributes, the value attribute elements were divided into three categories [15]: landscape designed and created intentionally by people, organically evolving landscape and associative cultural landscape.

2.3.2. Step 2: Transregional Cultural Landscape Security Assessment

(1) Ecological security assessment

From the perspective of the landscape pattern, the study quantified the loss degree of natural attributes of the regional landscape pattern after being affected by external influences through the landscape disturbance and vulnerability index. It constructed the landscape ecological risk index (ERI) to determine the level of regional ecological security in reverse. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

where is the ecological risk index of the kth risk unit; n is the number of landscape types; i is cropland, woodland, grassland and others of the six types of landscape; is the area of class i landscape in the kth risk unit (km2); is the total area of the kth risk unit (km2); is the landscape disturbance index of landscape type i; and is the landscape vulnerability index of landscape type i.

Among them, the landscape disturbance index () selected the landscape fragmentation index () [28,29], landscape separation index () [30] and landscape dominance index () [31,32], which are closely related to landscape disturbance. The specific expressions and related calculation formulas are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The related calculation formulas for landscape disturbance index.

Concerning the relevant literature [35,36] and the region’s current situation, the demonstration area was classified into six types: cropland, woodland, grassland, water, urban land and unused land. Then, it was graded and normalized to produce a landscape vulnerability index (). The vulnerability classification of each landscape type was as follows: unused land-6; water-5; cropland-4; grassland-3; woodland-2; urban land-1.

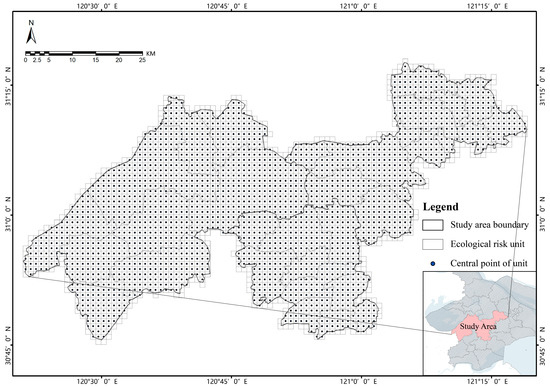

In order to ensure the integrity of the information and the accuracy of the values, the study integrated the foundation of previous studies [37,38] with the number and calculation workload of landscape patches and selected a 1 km × 1 km square grid for equally spaced sampling to obtain a total of 2677 ecological risk units (Figure 3). Furthermore, the results of the landscape ecological risk index were used as the results of the ecological risk calculation for the center points of each unit, and their ecological security levels were determined by spatial interpolation.

Figure 3.

Square sampling grid of 1 km × 1 km in the demonstration area.

(2) Cultural value security assessment

First, the study referred to the relevant documents and literature on the cultural landscape value assessment [39,40,41] and used the Delphi method to clarify the indicator subdivisions under different value orientations regarding value importance and value quality. Considering the value focus of different cultural landscape types, the study applied the AHP method and Yaahp software to calculate each evaluation indicator’s weights and finally established the evaluation system for the cultural value security of the transregional cultural landscape.

Subsequently, based on the above assessment system, the value importance and quality of each value attribute element in the demonstration area were scored separately and then superimposed to determine its cultural landscape value security level, calculated by the following formula.

where is the cultural value security score of the value attribute element; is the value importance score of the value attribute element; and is the value quality score of the value attribute element.

Finally, the security values of the value attribute elements (points) were assigned to their surrounding neighborhoods (surfaces) through the kernel density analysis tool in ArcGIS10.6 to visualize the results of the cultural value security assessment and the spatial aggregation of the demonstration area. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

where is the score estimation of value security in the neighborhood of the value attribute element; i = 1, …, n is the number of value attribute elements; h is the search radius; is the cultural value security score of the value attribute element; and is the straight line distance between value attribute element i and the center point of domain space.

2.3.3. Step 3: Identify Cultural Landscape Security Pattern and Key Protected Areas

Based on the cultural landscape’s definition of ‘Combined works of nature and humankind’ [42], the ecological security and value security evaluation results were superimposed equivalently through the raster calculator of ArcGIS10.6, and the demonstration area level of the cultural landscape security pattern was divided by an equal interval method. Finally, optimization strategies were developed according to the landscape characteristics of the different hierarchical security patterns.

3. Results

3.1. Condensation of Cultural Landscape Values and Identification of Value Attributes Based on Natural and Historical Geography Analysis

3.1.1. Natural Geography Analysis

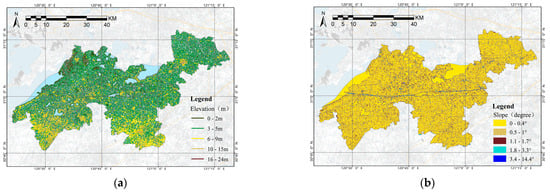

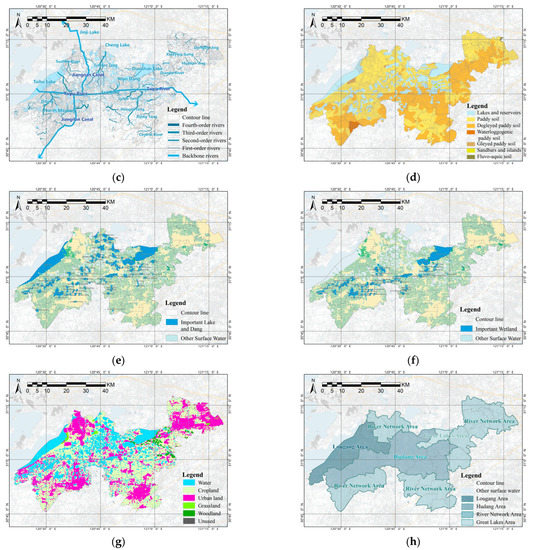

Its topography is low in the north, high in the south and slightly inclined to Taihu Lake. Its relative height is less than 25 m (Figure 4a). The terrain fluctuates gently, and the slope change is below five (Figure 4b). Dianshan Lake and Yuandang are the ecological hearts of the demonstration area, and Jiangnan Canal and the Taipu River are vertical and horizontal green corridors. They all structure the water network pattern of the whole site (Figure 4c). The water system has various forms, and the water coverage rate is as high as 20.6% (Figure 4e,f). The soil composition is mainly in paddy and degleyed paddy soil (Figure 4d). Among the land use types, cropland accounts for the highest proportion, accounting for 48.7%, followed by urban land, accounting for 29.3%, and forest and grassland at a smaller scale (Figure 4g), accounting for only 1.4%. A series of human activities, such as building dikes, digging water and building fields, has created a complete cultural ecosystem of the polder system and formed four landscape geographical feature divisions: the Lougang Area, Hudang Area, River Network Area and Great Lakes Area (Figure 4h).

Figure 4.

Natural basement analysis of the demonstration area. (a) Elevation analysis; (b) slope analysis; (c) water networks analysis; (d) soil analysis; (e) distribution of important lakes and Dang; (f) distribution of important wetlands; (g) land use analysis; (h) landscape geographical feature divisions.

3.1.2. Historical Geography Analysis

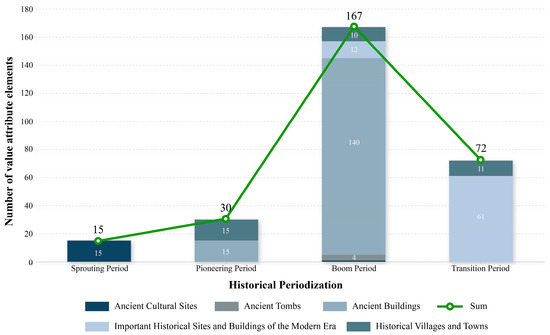

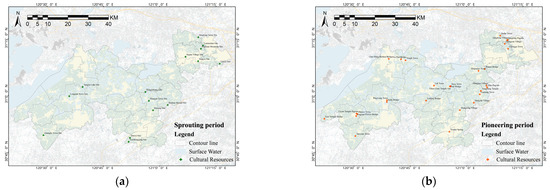

The demonstration area has an excellent natural resources endowment, which has laid a good material foundation for developing its cultural resources. Through the crawling and examination of ancient documents and historical maps, we divided the evolution of the demonstration area’s vernacular cultural landscape into four periods: the sprouting period (Neolithic Age to Han Dynasty), the pioneering period (Three Kingdoms to Song Dynasties), the boom period (Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties) and the transition period (the Republic of China to the present).

The only type of cultural resource in the sprouting period is the ancient cultural site (Figure 5), which is focused on the higher terrain on the southeast side of the area (Figure 6a). The number of cultural resources in the pioneering period gradually increased, and historical and cultural towns, such as Tongli Town and Zhenze Town, took shape in this period (Figure 6b). During the boom period, cultural resources increased dramatically, distributed in clusters across the study area (Figure 6c). Their types were abundant, and the bridge is the most typical, totaling 68. These cultural resources have directly or indirectly contributed to the formation and development of the ten historical and cultural towns represented by Xitang Ancient Town. The important historical sites and buildings of the modern era were the primary value attribute elements in the transition period, forming a modern water town pattern with alternating old and new things (Figure 6d).

Figure 5.

Quantitative analysis of cultural resources in the demonstration area under different historical periodizations.

Figure 6.

Temporal and spatial distributions of cultural resources in the demonstration area. (a) Sprouting period; (b) pioneering period; (c) boom period; (d) transition period.

3.1.3. Core Value System and Classification of Value Attribute Elements

The vernacular cultural landscape conforms to the construction logic of the typical residential environment in the Taihu Lake Basin of China. The core value of the demonstration area is a world-class model of waterfront human dwelling civilization, which derived from the joint outcome of the harmonious blue–green spatial system, the charming district with Jiangnan water town culture and the eternal wisdom of water management and agriculture (Table 3).

Table 3.

Core values of the vernacular cultural landscape in the demonstration area.

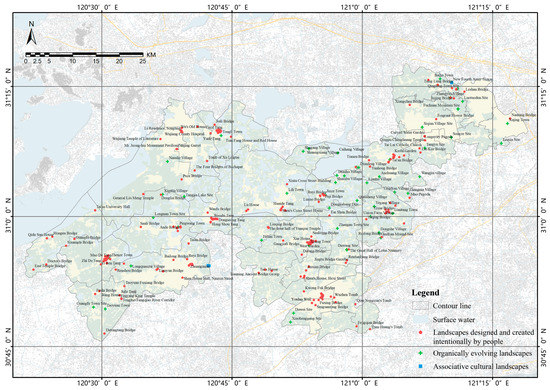

Based on the above interpretation of values, the 284 value attribute elements that formed during the four stages of development were identified and classified into three categories: landscape designed and created intentionally by people (229), organically evolving landscape (52) and associative cultural landscape (3) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Distribution of value attribute elements in the demonstration area.

3.2. Regional Cultural Landscape Security Assessment Results

3.2.1. Ecological Security Assessment Results

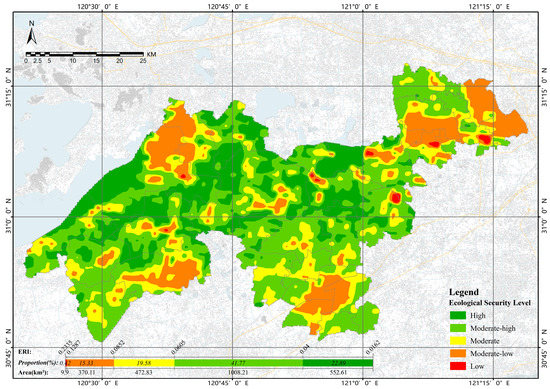

Through Fragstats4.2, the landscape pattern indexes for six land use types were calculated by combining the characteristics of landscape patches (Table 4). After this, the transregional landscape ecological security assessment results were visualized using Ordinary Kriging in ArcGIS 10.6. The results of the landscape ecological assessment were divided into five levels by the Jenks method: high ecological security, moderate-high ecological security, moderate ecological security, moderate-low ecological security and low ecological security.

Table 4.

Calculation results of ecological risk index in the demonstration area.

As shown in Figure 8, the total proportion of high ecological and moderate-high ecological security areas was 64.66%, and the ecological security situation in the demonstration area was excellent. From the perspective of spatial distribution, the ecological security level in the demonstration area conformed to the terrain change, and the ecological security value in the northwest and central low-lying areas was higher than that in the southeast.

Figure 8.

Ecological security analysis of the demonstration area.

Among them, the land use type of the high ecological security area was mainly water, and the ecological regulation and storage capacity was strong. Thus, the ecological risk index rate was low. The moderate-high ecological security area was uniformly distributed in a continuous pattern, with arable land and widely distributed rivers, and the relationship between water and fields was relatively balanced. Hence, the landscape ecological risk index was low. The moderate ecological security area was mainly evenly distributed irregularly hollow patches, with a tendency to expand and adhere between patches. There might be a risk of encroachment on the high ecological security area. Areas with moderate-low ecological security levels mainly involved Xianghuaqiao Street and Huaxin Town in Qingpu, Wujiang Economic and Technological Development Zone, Shengze Town in Wujiang and Weitang Street in Jiashan. They formed four low ecological security areas. In these areas, both the population and industrial construction activities were concentrated, which are tremendous pressures on ecological environmental protection. Low ecological security areas accounted for a tiny proportion of space, mainly distributed in the core construction areas of Qingpu and sporadically distributed in key development towns in Wujiang. Additionally, this area was significantly affected by human activities, with a high degree of fragmentation of landscape patches and a high degree of ecological risks.

3.2.2. Cultural Value Security Assessment Results

The cultural value security assessment results were divided into two parts. First was the formulation of the assessment indexes and their weighting. The second was the spatial visualization of the value security assessment results.

The assessment indexes of cultural landscape value importance were constructed from five aspects (history, science, art, society and culture) [43,44], four levels (target level, criterion level, domain level and factor level) and 31 evaluation indicators. The scale also complied with the value focus of different cultural landscape subtypes and derived the indicator weights for different subcategories (Table 5).

Table 5.

Assessment scale of cultural landscape value importance in the demonstration area.

According to the results of the field research, the application of indigenous knowledge, with the polder system at its core, shaped the vernacular habitat in the demonstration area. It highly integrated agricultural water conservancy, settlement construction, water space and traditional folklore, and transformed the lowland of the lake area with frequent floods into a livable landscape pattern on the polder fields. Therefore, the study followed the definition of authenticity and integrity [43] and established a value quality evaluation system based on the above landscape pattern characteristics. It was specifically concerned about the polder field system, the local built heritage, the water environment and the people involved. Meanwhile, we subdivided 22 sub-indicators from other internal and external factors such as form and design, materials and function, location and environment, scale and area, technology and management systems and cultural spirit and intangible heritage (Table 6).

Table 6.

Assessment scale of cultural landscape value quality in the demonstration area.

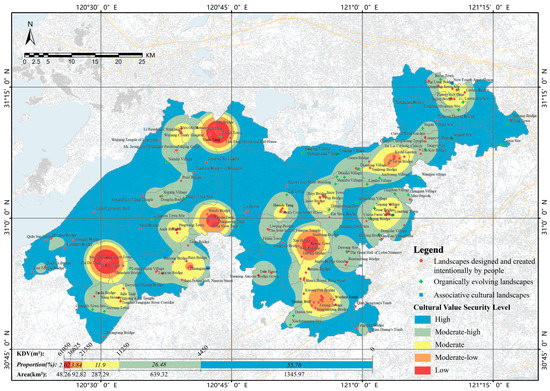

Finally, the study evaluated the value security scores of 284 value attribute elements (Appendix A), which were visualized and classified into five categories: high value security area, moderate-high value security area, moderate value security area, moderate-low value security area and low value security area (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Cultural value security analysis of the demonstration area.

It can be seen from Figure 8 that the overall performance of value security in the demonstration area was excellent, with nearly 85% of the regional space at a high level of value security. Additionally, the southeast region mainly tended to be at a medium-high level of security, which was better than the northwest region.

Among them, the low value security area accounted for the smallest area. It had a scattered layout, involving Tongli Ancient Town, Zhenze Ancient Town, Lili Ancient Town, Xitang Ancient Town and surrounding areas. In this area, value attribute elements were highly clustered. Nevertheless, due to poor protection, there was a severe loss of authenticity and integrity, resulting in a low value security level. The moderate-low value security area was the expansion area of the low value security area, slightly larger in area than the low value security area, and involved two historic towns, Zhujiajiao and Ganyao, in addition to the three ancient towns mentioned above. Moderate value security areas showed the distribution trend of concentrated groups, mainly distributed in the region’s neighborhood space of famous historical and cultural towns and villages. Moderate-high value security areas were distributed contiguously, with a relatively even distribution of value attribute elements and good expression of cultural values. The natural value attribute of the high value security area was prominent, and the number of value attribute elements was small and scattered, which had a low influence on the expression of the demonstration area’s cultural value.

3.3. Identification of Security Patterns in Vernacular Cultural Landscapes and the Formulation of Optimization Strategies for Key Protected Areas

3.3.1. Comprehensive Assessment Results and Security Level Division

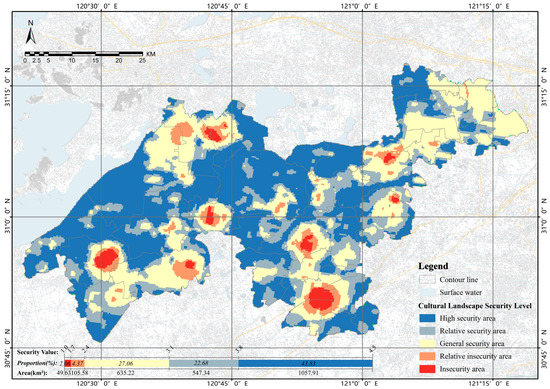

In total, there were five levels of vernacular cultural landscape security patterns in the demonstration area: high security area, relative security area, general security area, relative insecurity area and insecurity area (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Result of vernacular cultural landscape security pattern in the demonstration area.

From Figure 10, the vernacular cultural landscape security level in the demonstration area was generally high, with about 66.51% of the area at a high level of safety. However, there was still a small percentage of low-safety areas that urgently needed to be improved.

The insecurity area was highly correlated with various historical and cultural villages and towns. It overlapped with Zhenze Ancient Town, Xitang Ancient Town, Tongli Ancient Town and Zhujiajiao Ancient Town in space. The relative insecurity area was the buffer zone of the insecurity area, and together with the insecurity areas in the northeast, southeast, northwest and southwest, formed four low-value areas of cultural landscape security. These areas had high ecological and cultural risks. General security areas covered many key construction areas, such as Chonggu Town in Qingpu, Wujiang Economic and Technological Development Zone and Tianning Town in Jiashan. Due to the influence of human activities, there was certain protection pressure on the cultural landscape in the region. The relative security areas were mainly distributed in the outer ring of each general security area, showing continuous irregular patches. The close distance between patches showed an adhesion trend, and the regional connectivity was low. High security areas accounted for the most significant proportion, their related ecological and cultural resources were in good condition of management and protection and the security level of the cultural landscape was the highest.

3.3.2. Grading Strategy Guidance for Key Conservation Areas

Considering the transregional landscape geographical feature divisions (Figure 4h), the study attempted to propose various optimization strategies for the different security areas from the perspective of overall spatial conservation planning (Table 7).

Table 7.

Hierarchical optimization strategy of the different cultural landscape security zones in the demonstration area.

4. Discussion

4.1. Importance of Natural–Cultural Methodology

In recent years, holistic and regional conservation has become the consensus in the practice of world heritage conservation [17,18]. However, in the process of the spiritual and aesthetic development of the western landscape, nature has spent most of its time wandering outside of human beings. In particular, after the 17th century, the flourishing of western rationalism, science and metrology promoted scientific knowledge to become the orthodox rational empirical tool, and widespread doubts about the validity of natural empirical perceptions arose [45]. The stereotypical thinking of rationalism is a deep-seated cause of the long-standing separation between world natural heritage and cultural heritage assessment.

In this study, the results figured that the overall ecological security in the demonstration area was excellent, with 41.77% and 22.89% of the moderate-high ecological and the high ecological security areas, respectively. The percentage of the low ecological security areas was very small, only 0.43%, dotted in Qingpu District and Wujiang District. The moderate-low ecological security areas accounted for 15.33%. Areas with moderate ecological security levels accounted for 19.58%, which was the expansion of the moderate-low ecological security areas.

On the other hand, the value security situation in the demonstration area was generally good. Among them, the low value security areas were slightly larger than the low ecological security areas (+1.59%). Spatially, it coalesced to form two high-density cores (Tongli Ancient Town and Zhenze Ancient Town) and two sub-density cores (Lili Ancient Town and Xitang Ancient Town), which did not overlap with the low ecological security areas. The high value security areas accounted for more than half of the region, at 55.76%, which was significantly larger than the high ecological security areas (+32.87%). Additionally, they basically covered the high ecological security areas in spatial terms. The moderate-high and moderate value security areas were both smaller than the ecological security assessment results at the same level, with a reduction of 15.29% and 7.68%, respectively. In summary, when a single natural or cultural method is applied to the identification of key protected areas of complex transregional vernacular cultural landscapes, the results are not the same whether it is the location of key areas or the area measurement.

After the spatial superposition calculation, the comprehensive results showed that insecurity areas accounted for 2.06%, which was an increase of 1.63% and 0.04% compared with the low ecological and low value security areas, respectively. Their spatial settlement was the sum of the low ecological and low value security areas, involving Tongli Ancient Town, Zhenze Ancient Town, Shengze Ancient Town, Lili Ancient Town, Xitang Ancient Town, Weitang Street, Zhujiajiao Ancient Town and Liantang Ancient Town. The proportion of the relative insecurity areas was slightly larger than the moderate-low value security areas (+0.53%) but smaller than the areas with moderate-low ecological security levels (−10.96%). The proportion of general security areas was greater than the moderate value security areas (+15.16%) and the moderate ecological security areas (+7.48%), which overlap spatially with the moderate-high ecological security areas to a high degree. The proportion of high security areas (43.83%) was in the middle of the high ecological and high value security areas.

The results also showed an obvious correlation between ecological security level and land use type. The higher the proportion of water and cropland, the higher the degree of ecological security, while the urban land was the opposite. Moreover, the distribution of low cultural security space in the demonstration area highly overlapped with that in densely populated urban land. All of the above verify the correlation between security levels, natural waters and human influence activity intensity.

The significance of this study is to prove that it is necessary to establish a more comprehensive and structured methodology for the security pattern of vernacular cultural landscapes. Additionally, the methodology should be based on a long-term, continuous temporal evolutionary restoration process and multi-dimensional value conservation. It can not only help broaden the resource and ecological protection idea but also enrich and improve the holistic conservation of international natural and cultural heritage theory. We combined the characteristics of the study area and the research results for further analysis.

4.2. Security Pattern Indicators for Integrated Conservation

It is important to identify the indicators for constructing a nature–culture integrated security pattern in this specific case study. The existing traditional ecological environment assessment mainly focuses on the ecological risk assessment with altitude, slope, soil type, surface coverage and land use distance as vital influencing factors [46,47,48] or the evaluation of specific risk sources such as flood risk and geological disaster [49,50]. This study tried to measure the ecological security level of the demonstration area in a holistic and reverse method through the disturbance and vulnerability index from a landscape pattern perspective.

The evaluation system of value importance and value quality was constructed using the five heritage values of history, science, aesthetics, culture and society as criteria, and the standards of authenticity and integrity as principles. It is particularly important to note that human beings have long been involved in the cycles of natural ecosystems through their production and living practices, and they formed an interdependent relationship with nature, giving rise to a range of traditional scientific knowledge, belief systems and practical wisdom in resource management [51]. This process has contributed to the formation of distinctive vernacular cultural landscapes, which have become an essential medium for expressing the natural and cultural diversity in different areas. Therefore, in assessing the value, we have taken into account the concrete embodiment of indigenous knowledge in the index which maintains the core value of human–water symbiosis.

The demonstration area is generally low-lying with a network of water. It is the area with the most serious threat of flooding and the most prominent water conflicts in the Taihu Lake basin in China. In response to this natural environment, local residents have transformed the silt into fertile soil by excavating rivers, building embankments and reclaiming fields, thus creating a unique polder landscape system. On the one hand, the polder system has a strong function of flood detention and drainage. It turned water damage into water conservation by flexibly deploying water resources through the construction of dykes, the dredging of rivers and the installation of sluices. This objectively preserves the local ecological environment. On the other hand, the polder system, as a self-sufficient and efficient mode of complex agricultural production, effectively guarantees the food supply and economic development. It provides the residents with a material basis for sustainable survival. Furthermore, the intangible cultural heritages derived from the polder system, such as the silk weaving technique and the fishing song technique, have also influenced the socio-humanitarian environment of the demonstration area profoundly and comprehensively. Thus, the whole vernacular landscape centered on the polder system, including the local built heritage, water environment and people involved, is the embodiment of the indigenous knowledge system in this region. The assessment of these indicators also reflects the degree of adaptation to the environment, the intensive practice of resource use and the cultural transmission of experiential knowledge by the residents, characterizing the value quality of the vernacular cultural landscape.

Indigenous knowledge is embedded in culture and has regional and social uniqueness [52]. That said, when this integrated assessment framework is applied to other global regions, the association of local knowledge with cultural landscape values should also be fully considered and reflected in the value assessment indicators.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Firstly, the degree of “mutual construction” in the local cultural landscape needs to be further explored. This study adopted the equal weight of nature and culture to conduct a quantitative evaluation. In future research, we will focus on the different contribution rates of nature and culture in shaping the vernacular cultural landscape. Secondly, due to limited time and a large number of evaluation objects, the cultural value scoring work involved in the study was all completed by the members of the research group after the field survey, which belongs to “external evaluation”. Although interviews were conducted with local communities, managers and other relevant stakeholders to obtain the “internal perspective” of local knowledge, due to the differences in “the way of seeing”, the opinions of local communities should be included in the value scoring link in further research. This multi-agent assessment is conducive to transforming local knowledge from the role of “background” and “providing data” to local knowledge participation in management and providing future solutions.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we emphasized that high-quality ecological and green development depends on integrating nature and culture. The study proposed a conceptual framework for constructing transregional vernacular cultural landscape security patterns. According to the scientific security pattern analysis results, more targeted environmental protection response measures can be formulated. The framework consists of three steps: value refining, security evaluation and pattern construction from the perspective of time sequence and measurement. In addition, security assessment includes the evaluation of landscape disturbance, landscape vulnerability and the landscape loss index, value importance and value quality, which can be evaluated consistently and logically in this framework. The study also proposes how to formulate the optimization strategy of different security zones according to local landscape characteristics of geographical space units. The case study shows that the overall performance of the security pattern in the demonstration area was excellent. However, there was still a low-security area of approximately 6.43% that urgently needed to be improved. Our conceptual framework, indicators and evaluation methods for vernacular cultural landscape security can be widely used for the identification, improvement and spatial planning of key protection areas at transregional scales and in related research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D.; methodology, S.D.; formal analysis, J.Y.; investigation, J.Y., S.D. and J.Z.; data curation, J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D., J.Y. and W.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.D.; visualization, J.Y.; supervision, S.D.; project administration, S.D.; funding acquisition, S.D. and J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 52208067, General Projects of Art and Science Planning in Shanghai, No. YB2020G01, the Shanghai Institute of Technology introduction of talents research initiation project, No. YJ2021-74, and National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 42001184.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The cultural value security score of each value attribute element.

Table A1.

The cultural value security score of each value attribute element.

| Number | Name | lat | lng | Value Importance | Value Quality | Value Security |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tongli Ancient Town | 120.729409 | 31.156127 | 95 | 95 | 95 |

| 2 | Zhenze Ancient Town | 120.515654 | 30.918912 | 90 | 93 | 91.5 |

| 3 | Lili Ancient Town | 120.855612 | 31.044517 | 92 | 93 | 92.5 |

| 4 | Zhujiajiao Ancient Town | 121.053045 | 31.109589 | 93 | 94 | 93.5 |

| 5 | Liantang Ancient Town | 121.058726 | 31.005866 | 90 | 86 | 88 |

| 6 | Jinze Ancient Town | 120.928882 | 31.041805 | 90 | 88 | 89 |

| 7 | Xitang Ancient Town | 120.897876 | 30.94479 | 95 | 95 | 95 |

| 8 | Pingwang Town | 120.64669 | 30.97991 | 88 | 85 | 86.5 |

| 9 | Taoyuan Town | 120.506958 | 30.822237 | 85 | 80 | 82.5 |

| 10 | Xujing Town | 121.278826 | 31.178794 | 82 | 81 | 81.5 |

| 11 | Baihe Town | 121.149703 | 31.264801 | 85 | 82 | 83.5 |

| 12 | Chonggu Town | 121.184522 | 31.206799 | 86 | 84 | 85 |

| 13 | Fenan Town | 120.807037 | 30.954243 | 81 | 80 | 80.5 |

| 14 | Zhangxing Village | 120.970256 | 30.936375 | 81 | 75 | 78 |

| 15 | Zhangyan Village | 121.169565 | 31.229108 | 80 | 79 | 79.5 |

| 16 | Qinglong Village | 121.183233 | 31.245574 | 79 | 82 | 80.5 |

| 17 | Wangjin Village | 121.110524 | 31.076721 | 73 | 74 | 73.5 |

| 18 | Zhanglian Village | 120.965796 | 31.078236 | 73 | 78 | 75.5 |

| 19 | Shuangxiang Village | 120.897858 | 31.13039 | 78 | 76 | 77 |

| 20 | Shagang Village | 120.886904 | 31.125318 | 73 | 73 | 73 |

| 21 | Qiansheng Village | 120.990281 | 31.030522 | 71 | 70 | 70.5 |

| 22 | Shambu Village | 120.949015 | 31.06539 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

| 23 | Lianhu Village | 121.009105 | 31.064915 | 73 | 71 | 72 |

| 24 | Caihang Village | 120.953336 | 31.122277 | 72 | 74 | 73 |

| 25 | Dianhu Village | 120.951503 | 31.079105 | 71 | 76 | 73.5 |

| 26 | Dianshan Lake first Village | 120.989934 | 31.094466 | 72 | 82 | 77 |

| 27 | Dianfeng Village | 120.993589 | 31.094121 | 74 | 78 | 76 |

| 28 | Anzhuang Village | 121.03287 | 31.076665 | 68 | 74 | 71 |

| 29 | Zhangma Village | 121.08779 | 31.044714 | 65 | 76 | 70.5 |

| 30 | Yegang Village | 121.023059 | 31.019513 | 67 | 80 | 73.5 |

| 31 | Yingdian Village | 121.062235 | 31.047116 | 65 | 79 | 72 |

| 32 | Union Farm Village | 121.016078 | 30.999997 | 66 | 76 | 71 |

| 33 | Dongshe Village | 121.032412 | 30.969005 | 69 | 84 | 76.5 |

| 34 | Nanshe Village | 120.626398 | 31.105811 | 65 | 80 | 72.5 |

| 35 | Longquanzui Village | 120.556104 | 30.904932 | 61 | 66 | 63.5 |

| 36 | Xigang Village | 120.617056 | 31.042511 | 60 | 70 | 65 |

| 37 | Songze Site | 121.171145 | 31.152176 | 95 | 95 | 95 |

| 38 | Fuchuan Mountain Site | 121.183492 | 31.206747 | 94 | 91 | 92.5 |

| 39 | Qinglong Town Site | 121.17155 | 31.257998 | 92 | 90 | 91 |

| 40 | Siqian Village Site | 121.115228 | 31.171707 | 88 | 75 | 81.5 |

| 41 | Jinshan Mound Site | 121.036001 | 30.9592 | 82 | 50 | 66 |

| 42 | Liuxia Site | 121.267137 | 31.140878 | 80 | 45 | 62.5 |

| 43 | Qinglong Pagoda | 121.180624 | 31.244487 | 82 | 90 | 86 |

| 44 | Mao Pagoda | 121.09107 | 31.036254 | 84 | 90 | 87 |

| 45 | Tangyu Site | 121.06245 | 31.117805 | 86 | 88 | 87 |

| 46 | Yingxiang Bridge | 120.928317 | 31.041207 | 84 | 80 | 82 |

| 47 | Puji Bridge | 120.926263 | 31.040683 | 86 | 84 | 85 |

| 48 | Chen Yun’s former residence | 121.050436 | 31.012765 | 80 | 90 | 85 |

| 49 | Curved Water Garden | 121.120401 | 31.154828 | 82 | 86 | 84 |

| 50 | Longevity Pagoda | 121.120868 | 31.146783 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| 51 | Luotuodun Site | 121.192889 | 31.221306 | 78 | 50 | 64 |

| 52 | Tsing Lung Temple | 121.180964 | 31.245533 | 76 | 80 | 78 |

| 53 | Tsing Lung Bridge | 121.145328 | 31.253453 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| 54 | Wanan Bridge | 121.080362 | 31.117621 | 73 | 60 | 66.5 |

| 55 | Shunde Bridge | 121.053717 | 31.026585 | 72 | 62 | 67 |

| 56 | Qingze Bridge | 121.172659 | 31.247044 | 72 | 63 | 67.5 |

| 57 | Guanwang Temple | 120.987914 | 31.09538 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| 58 | Yihao Chan Temple Site | 120.927051 | 31.041083 | 73 | 75 | 74 |

| 59 | The former site of the Xiaoyao Peasant Riot | 121.08041 | 30.986988 | 68 | 64 | 66 |

| 60 | Head Gate of Qingpu Chenghuang Temple | 121.11981 | 31.154384 | 70 | 80 | 75 |

| 61 | New Fourth Army Slogan | 121.171916 | 31.257227 | 60 | 34 | 47 |

| 62 | Kezhi Garden | 121.05997 | 31.119531 | 69 | 80 | 74.5 |

| 63 | Ruyi Bridge | 120.919126 | 31.040317 | 68 | 60 | 64 |

| 64 | Linlao Bridge | 120.919534 | 31.039489 | 70 | 62 | 66 |

| 65 | Tianhuangge Bridge | 120.916712 | 31.028715 | 71 | 60 | 65.5 |

| 66 | Jinze Release Bridge | 120.924308 | 31.043574 | 70 | 60 | 65 |

| 67 | Nantang Bridge | 121.284073 | 31.188798 | 68 | 60 | 64 |

| 68 | Jinjing Bridge | 121.175994 | 31.227575 | 70 | 60 | 65 |

| 69 | Leshan Bridge | 121.196269 | 31.240314 | 68 | 60 | 64 |

| 70 | Yongxing Bridge | 121.045104 | 31.006345 | 70 | 60 | 65 |

| 71 | Tianguang Temple | 121.063823 | 31.021106 | 75 | 80 | 77.5 |

| 72 | Yixue Bridge | 121.047218 | 31.009278 | 68 | 60 | 64 |

| 73 | Chaojin Bridge | 121.051563 | 31.008745 | 73 | 60 | 66.5 |

| 74 | The old classrooms of Yan’an Primary School | 121.04515 | 31.013393 | 75 | 78 | 76.5 |

| 75 | Ruilong Bridge | 121.037745 | 30.960832 | 70 | 60 | 65 |

| 76 | Yuqing Bridge | 121.008069 | 30.994987 | 75 | 60 | 67.5 |

| 77 | Fragrant Flower Bridge | 121.142249 | 31.18759 | 70 | 60 | 65 |

| 78 | Xiangchen Bridge | 121.091335 | 31.214668 | 69 | 60 | 64.5 |

| 79 | Lin Kee Bridge | 121.112064 | 31.123307 | 70 | 60 | 65 |

| 80 | Jissen Bridge | 121.127249 | 31.263041 | 69 | 60 | 64.5 |

| 81 | Tong Yu Site | 121.120422 | 31.131555 | 70 | 56 | 63 |

| 82 | Tai Lai Catholic Church | 121.110117 | 31.131337 | 72 | 78 | 75 |

| 83 | Tianen Bridge | 121.013478 | 31.10857 | 65 | 60 | 62.5 |

| 84 | Jiufeng Bridge | 121.071155 | 31.114481 | 70 | 60 | 65 |

| 85 | Qing Dynasty Post Office Site | 121.060079 | 31.113168 | 73 | 78 | 75.5 |

| 86 | Tai’an Bridge | 121.054973 | 31.110267 | 72 | 60 | 66 |

| 87 | Handalong Sauce Garden | 121.061579 | 31.115996 | 73 | 78 | 75.5 |

| 88 | Fuxing Bridge | 121.050568 | 31.105114 | 68 | 60 | 64 |

| 89 | Zhonghe Bridge | 121.051378 | 31.105702 | 68 | 60 | 64 |

| 90 | Yunhong Bridge | 121.015269 | 31.096402 | 68 | 60 | 64 |

| 91 | Tong Tin Ho Chinese Medicine Shop | 121.061094 | 31.114157 | 70 | 78 | 74 |

| 92 | Xi Family Residence | 121.050343 | 31.104315 | 70 | 58 | 64 |

| 93 | Zhujiajiao Town God’s Temple | 121.060348 | 31.114728 | 75 | 85 | 80 |

| 94 | Zhaochang Bridge | 121.169565 | 31.229108 | 69 | 65 | 67 |

| 95 | East Temple Bridge | 120.368994 | 30.898316 | 90 | 60 | 75 |

| 96 | Sze Pun Bridge | 120.709237 | 31.160832 | 90 | 62 | 76 |

| 97 | Chui Hung Broken Bridge | 120.654983 | 31.162228 | 93 | 74 | 83.5 |

| 98 | Keng Lok Tong | 120.721973 | 31.164198 | 91 | 88 | 89.5 |

| 99 | Shijian Hall | 120.510441 | 30.918847 | 92 | 86 | 89 |

| 100 | Retreat Garden | 120.726231 | 31.164274 | 94 | 90 | 92 |

| 101 | Silkworm Ancestral Shrine | 120.67316 | 30.90905 | 93 | 84 | 88.5 |

| 102 | Ciyun Temple Pagoda | 120.511762 | 30.921092 | 92 | 86 | 89 |

| 103 | The former residence of Liu Yazi | 120.717908 | 30.995118 | 90 | 92 | 91 |

| 104 | Longnan Town Site | 120.598978 | 30.997913 | 88 | 60 | 74 |

| 105 | Guangfu Town Site | 120.484391 | 30.825695 | 87 | 55 | 71 |

| 106 | Wang Xi Huan’s Tomb | 120.505276 | 30.916849 | 85 | 90 | 87.5 |

| 107 | Tomb of Xu Lingtai | 120.702282 | 31.107132 | 84 | 88 | 86 |

| 108 | Fragrant Flower Bridge | 120.510221 | 30.910442 | 86 | 90 | 88 |

| 109 | Hongen Bridge | 120.40546 | 30.961312 | 84 | 82 | 83 |

| 110 | Guangfu Bridge | 120.447762 | 30.957369 | 80 | 68 | 74 |

| 111 | Zhonghe Bridge | 120.50686 | 30.923777 | 81 | 72 | 76.5 |

| 112 | Hong Shou Tang | 120.709343 | 30.989117 | 80 | 76 | 78 |

| 113 | Zhi De Tang | 120.498746 | 30.908417 | 86 | 78 | 82 |

| 114 | Chongben Tang | 120.723982 | 31.164525 | 84 | 83 | 83.5 |

| 115 | Zhougongfu Ancestral Shrine | 120.713709 | 30.994047 | 87 | 89 | 88 |

| 116 | The former residence of Chen Zhaodi | 120.723366 | 31.160969 | 85 | 88 | 86.5 |

| 117 | Tomb of Martyr Zhang Yingchun | 120.781039 | 31.014765 | 82 | 84 | 83 |

| 119 | Wujiang Temple of Literature | 120.613008 | 31.149287 | 86 | 71 | 78.5 |

| 120 | Japanese Artillery Building No. 75 on the Sukha Railway | 120.706107 | 30.905492 | 80 | 83 | 81.5 |

| 121 | Jiayin Tang | 120.7244 | 31.164022 | 81 | 80 | 80.5 |

| 122 | Duanben Garden | 120.718542 | 30.996044 | 80 | 85 | 82.5 |

| 123 | Qian Diangen Martyr Monument | 120.653004 | 31.163385 | 78 | 79 | 78.5 |

| 124 | Anmin Bridge | 120.638047 | 30.980856 | 79 | 82 | 80.5 |

| 125 | Shengming Bridge | 120.674519 | 30.907203 | 72 | 88 | 80 |

| 126 | Muben Tang | 120.727409 | 31.16314 | 74 | 85 | 79.5 |

| 127 | Yushu Bridge | 120.512252 | 30.921134 | 78 | 67 | 72.5 |

| 128 | Xu Dayuan’s former residence | 120.713706 | 30.995183 | 70 | 74 | 72 |

| 129 | Jidong Association Hall | 120.670572 | 30.908735 | 73 | 71 | 72 |

| 130 | Dongseong Tang | 120.722271 | 30.995176 | 71 | 76 | 73.5 |

| 131 | The Retreat | 120.709547 | 30.989853 | 78 | 58 | 68 |

| 132 | Tai’an Bridge | 120.666908 | 30.948381 | 73 | 60 | 66.5 |

| 133 | Ande Bridge | 120.64608 | 30.972471 | 80 | 75 | 77.5 |

| 134 | Sanli Bridge | 120.575341 | 30.980146 | 78 | 75 | 76.5 |

| 135 | Bailong Bridge | 120.637818 | 30.916989 | 71 | 80 | 75.5 |

| 136 | The former residence of the Southern Society Communication Office | 120.715077 | 30.995344 | 70 | 68 | 69 |

| 137 | Former residence of Zhang Yingchun | 120.777911 | 31.011913 | 72 | 80 | 76 |

| 138 | Tian Fang House and Red House | 120.748353 | 31.153648 | 70 | 75 | 72.5 |

| 139 | Silk Industry Public School Site | 120.506687 | 30.918705 | 74 | 86 | 80 |

| 140 | Wolun Temple | 120.720806 | 31.165752 | 69 | 60 | 64.5 |

| 141 | Puze Bridge | 120.65366 | 31.071503 | 68 | 62 | 65 |

| 142 | Fuguan Bridge | 120.723685 | 31.167235 | 70 | 72 | 71 |

| 143 | Sifan Bridge | 120.503823 | 30.914191 | 78 | 80 | 79 |

| 144 | Shuangta Bridge | 120.431871 | 30.943912 | 76 | 78 | 77 |

| 145 | Zhengxiu Tang | 120.507828 | 30.917517 | 60 | 50 | 55 |

| 146 | Pang’s Ancestral Shrine | 120.724911 | 31.167191 | 63 | 55 | 59 |

| 147 | Former residence of Yang Tianji | 120.727382 | 31.165846 | 71 | 58 | 64.5 |

| 148 | Kengxiang Tang | 120.516317 | 30.918297 | 66 | 52 | 59 |

| 149 | Zunjing Garret | 120.643807 | 31.129982 | 72 | 74 | 73 |

| 150 | Wang House | 120.537912 | 30.842366 | 62 | 75 | 68.5 |

| 151 | Shen’s Cross Street House | 120.844386 | 31.012417 | 70 | 80 | 75 |

| 152 | Huaide Tang | 120.843496 | 31.012942 | 63 | 66 | 64.5 |

| 153 | Tangjia Lake Site | 120.658513 | 31.038552 | 74 | 38 | 56 |

| 154 | The Four Bridges of Bachapat | 120.678599 | 31.088797 | 67 | 60 | 63.5 |

| 155 | Wu’s former residence | 120.651911 | 31.165921 | 61 | 65 | 63 |

| 156 | Yi Ben Tang | 120.507869 | 30.916808 | 61 | 61 | 61 |

| 157 | Ning Shui Tang | 120.50841 | 30.919251 | 63 | 58 | 60.5 |

| 158 | Mao De Tang | 120.510477 | 30.91918 | 62 | 54 | 58 |

| 159 | Ning Qing Tang | 120.510221 | 30.919563 | 64 | 57 | 60.5 |

| 160 | Jing Sheng Tang | 120.508889 | 30.916754 | 64 | 67 | 65.5 |

| 161 | Yu Qing Tang | 120.506673 | 30.917153 | 72 | 70 | 71 |

| 162 | Shang Yi Tang | 120.506997 | 30.915875 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| 163 | Lianyun Bridge | 120.607888 | 30.89967 | 69 | 78 | 73.5 |

| 164 | Zhuangmian | 120.667925 | 30.90674 | 68 | 61 | 64.5 |

| 165 | Qidu Sun House | 120.394905 | 30.958343 | 65 | 63 | 64 |

| 166 | Purification Lake Daoist Temple and Qiuqi Bridge | 120.710603 | 30.99725 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| 167 | Xinta Cross Street Building | 120.855985 | 31.062429 | 66 | 78 | 72 |

| 168 | Shi De Tang | 120.726342 | 31.162958 | 62 | 80 | 71 |

| 169 | Qing Shan Tang | 120.727005 | 31.166453 | 68 | 84 | 76 |

| 170 | Zhu Residence in Tongli | 120.72393 | 31.161502 | 60 | 55 | 57.5 |

| 171 | Pu’an Bridge | 120.729035 | 31.164507 | 69 | 71 | 70 |

| 172 | Tongli Three Bridges | 120.72387 | 31.164403 | 72 | 75 | 73.5 |

| 173 | Yu De Tang | 120.727768 | 31.162633 | 62 | 60 | 61 |

| 174 | Xiaojiuhua Temple Jizang Spring Well | 120.651433 | 30.979237 | 61 | 63 | 62 |

| 175 | General Liu Meng Temple and Donglin Bridge | 120.613861 | 31.042351 | 68 | 75 | 71.5 |

| 176 | Fenyang King Temple | 120.534575 | 30.848996 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| 177 | Jiale Tang | 120.534575 | 30.848996 | 71 | 75 | 73 |

| 178 | Fushi Bridge | 120.48756 | 30.851369 | 68 | 53 | 60.5 |

| 179 | Sze Sang Kung Temple and Eup Ning Bridge | 120.579964 | 31.043533 | 62 | 64 | 63 |

| 180 | Doctor’s Bridge | 120.39374 | 30.90786 | 60 | 50 | 55 |

| 181 | Pang Shan Lake Farm Watchtower | 120.684287 | 31.173027 | 61 | 63 | 62 |

| 182 | No. 166 Yau Che Road Republican Building | 120.653976 | 31.170419 | 65 | 78 | 71.5 |

| 183 | Sujia Railway Pier | 120.70423 | 30.90613 | 67 | 77 | 72 |

| 184 | Mr. Jeong-hui Monument Pavilion | 120.644947 | 31.129903 | 66 | 70 | 68 |

| 185 | Zhenze Yesu Old Church | 120.505021 | 30.915778 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| 186 | Li Li Catholic Church | 120.722246 | 30.99484 | 64 | 76 | 70 |

| 187 | Li Li Shi Family House | 120.711545 | 30.995664 | 64 | 60 | 62 |

| 188 | Nan Yuan Tea House | 120.723296 | 31.161786 | 61 | 71 | 66 |

| 189 | Former Residence of Wang Shaoguan | 120.724752 | 31.164875 | 60 | 65 | 62.5 |

| 190 | Former residence of Qin Dongyuan | 120.645261 | 30.979054 | 65 | 67 | 66 |

| 191 | Dongxihe Wang House | 120.645045 | 30.978191 | 63 | 55 | 59 |

| 192 | Daifu Bridge | 120.673298 | 30.907039 | 60 | 52 | 56 |

| 193 | Qixintang Pharmacy | 120.673298 | 30.907039 | 62 | 60 | 61 |

| 194 | Renshou Bridge | 120.527132 | 30.898234 | 60 | 50 | 55 |

| 195 | Wanfu Bridge | 120.703461 | 31.007839 | 50 | 48 | 49 |

| 196 | Zheng’an Bridge | 120.510618 | 30.923135 | 63 | 52 | 57.5 |

| 197 | Wenshi Tang | 120.712976 | 30.995081 | 60 | 57 | 58.5 |

| 198 | Yu Jia Wan Boat House | 120.617874 | 30.89503 | 64 | 67 | 65.5 |

| 199 | Cecil Tang | 120.722397 | 31.164754 | 68 | 59 | 63.5 |

| 200 | Pui Yuen Public House 30th Anniversary Well | 120.66764 | 30.905944 | 61 | 55 | 58 |

| 201 | Wujiang County Hospital | 120.653282 | 31.165165 | 67 | 78 | 72.5 |

| 202 | Jingsu Hall | 120.725572 | 31.165016 | 60 | 56 | 58 |

| 203 | Taihu University Hall | 120.487584 | 31.01211 | 65 | 79 | 72 |

| 204 | The former site of the Qunle Inn | 120.651146 | 30.980935 | 64 | 78 | 71 |

| 205 | Ruyi Bridge | 120.664112 | 30.918272 | 60 | 53 | 56.5 |

| 206 | Former site of Shengji Silk House | 120.542937 | 30.909812 | 61 | 55 | 58 |

| 207 | Wu Residence, Baoshu Hall | 120.509569 | 30.919234 | 60 | 51 | 55.5 |

| 208 | Former site of Jiangfeng Agricultural and Industrial Bank | 120.505528 | 30.918705 | 62 | 76 | 69 |

| 209 | Datongtang Bridge | 120.505461 | 30.775092 | 60 | 45 | 52.5 |

| 210 | Jiuli Bridge | 120.716878 | 31.176748 | 60 | 70 | 65 |

| 211 | Tongluo Fengqiao River Corridor | 120.538146 | 30.842225 | 68 | 68 | 68 |

| 212 | The former site of the Taihu Water Conservancy Governor’s Office | 120.723508 | 31.164551 | 73 | 78 | 75.5 |

| 213 | Lu Hui Cross Street Building | 120.847512 | 31.019027 | 70 | 80 | 75 |

| 214 | Mao House, Maojia Lang | 120.719829 | 30.995231 | 60 | 64 | 62 |

| 215 | Wang House, Center Street | 120.720103 | 30.995018 | 61 | 66 | 63.5 |

| 216 | Wang House, Wangjialiang | 120.720171 | 30.995483 | 60 | 65 | 62.5 |

| 217 | Lu House, Taifeng Road | 120.845324 | 31.016048 | 60 | 63 | 61.5 |

| 218 | Ding House, Dingjialang | 120.713999 | 30.994956 | 60 | 61 | 60.5 |

| 219 | Khoo Residence, Centre Street | 120.717296 | 30.995251 | 61 | 65 | 63 |

| 220 | Shen House Hall, Nanxin Street | 120.655238 | 30.882743 | 60 | 63 | 61.5 |

| 221 | Li Residence, Songling | 120.653165 | 31.162895 | 60 | 67 | 63.5 |

| 222 | Taoyuan Fuxiang Bridge | 120.543724 | 30.866327 | 61 | 55 | 58 |

| 223 | Taian Bridge, Songling | 120.723467 | 31.163225 | 62 | 51 | 56.5 |

| 224 | Former site of Zhenfeng Silk Reeling Factory | 120.512848 | 30.925081 | 64 | 70 | 67 |

| 225 | The former site of Li Zi Kiln | 120.852637 | 31.011903 | 60 | 68 | 64 |

| 226 | Baixi Yulong Bridge | 120.495682 | 30.856983 | 62 | 45 | 53.5 |

| 227 | Former site of Tanqiu Silk Reeling Factory | 120.605635 | 30.897941 | 68 | 80 | 74 |

| 228 | The former site of the Communist Party of China East Special Committee of West Zhejiang Road and the Communist Party of China Wuxing County Committee | 120.538128 | 30.841744 | 62 | 58 | 60 |

| 229 | Wu Zhen Tomb | 120.922884 | 30.847286 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| 230 | Dawang Site | 120.970861 | 30.93571 | 86 | 50 | 68 |

| 231 | Yodun | 120.88838 | 30.882704 | 85 | 70 | 77.5 |

| 232 | Qian’s Dockyard | 120.882095 | 30.884853 | 80 | 74 | 77 |

| 233 | Weitang Ye Residence | 120.939953 | 30.846282 | 78 | 50 | 64 |

| 234 | Xitang Architectural Complex | 120.894666 | 30.950463 | 90 | 92 | 91 |

| 235 | Tianning Ancient Bridge Group | 120.826563 | 30.895785 | 86 | 70 | 78 |

| 236 | Duwei Site | 120.868483 | 30.814011 | 75 | 50 | 62.5 |

| 237 | Xiaohenggang Site | 120.862542 | 30.797007 | 75 | 50 | 62.5 |

| 238 | Zhangan Town Site | 120.952421 | 30.977189 | 75 | 50 | 62.5 |

| 239 | Jingtu Bridge Gazebo | 120.968774 | 30.911117 | 74 | 80 | 77 |

| 240 | Liuqing Bridge | 120.820659 | 30.978492 | 72 | 62 | 67 |

| 241 | Jiashan Martyrs’ Cemetery | 120.924598 | 30.84914 | 80 | 85 | 82.5 |

| 242 | The front hall of Yuanjue Temple | 120.819438 | 30.979759 | 70 | 73 | 71.5 |

| 243 | The Great Hall of Lotus Nunnery | 120.974405 | 30.937235 | 72 | 73 | 72.5 |

| 244 | Cishan | 120.924796 | 30.847353 | 77 | 80 | 78.5 |

| 245 | Yuantong Bridge | 120.814157 | 30.897813 | 78 | 60 | 69 |

| 246 | Sanguantang Bridge | 120.910578 | 30.829906 | 72 | 60 | 66 |

| 247 | Fengqian Bridge | 120.989276 | 30.78931 | 72 | 60 | 66 |

| 248 | Dongyue Temple | 120.911057 | 30.953093 | 78 | 80 | 79 |

| 249 | Qian Nengxun’s Tomb | 120.987015 | 30.83176 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| 250 | Yuan Huang’s Tomb | 121.0151 | 30.783785 | 72 | 50 | 61 |

| 251 | Jiashan City Site | 120.907356 | 30.839562 | 70 | 60 | 65 |

| 252 | Jin’s Back Hall | 120.903752 | 30.834035 | 72 | 60 | 66 |

| 253 | Lu’s Hall | 120.904614 | 30.950377 | 72 | 50 | 61 |

| 254 | Zunwen Hall | 120.897658 | 30.950225 | 71 | 70 | 70.5 |

| 255 | County Chancellor’s Office | 120.89772 | 30.947164 | 69 | 60 | 64.5 |

| 256 | Yongshou Zen Temple | 120.902337 | 30.95465 | 68 | 60 | 64 |

| 257 | Youlan Spring | 120.924016 | 30.841044 | 75 | 55 | 65 |

| 258 | West Garden | 120.8994 | 30.949884 | 65 | 78 | 71.5 |

| 259 | Xue House | 120.900143 | 30.950839 | 58 | 50 | 54 |

| 260 | Sun’s House | 120.923437 | 30.844188 | 60 | 50 | 55 |

| 261 | Shen De Tang | 120.897527 | 30.950131 | 64 | 60 | 62 |

| 262 | Shen’s House, Hexi Street | 120.889212 | 30.885903 | 62 | 58 | 60 |

| 263 | Yang’s House | 120.90225 | 30.952499 | 63 | 58 | 60.5 |

| 264 | Jinxian Bridge | 120.892572 | 30.896668 | 70 | 59 | 64.5 |

| 265 | Fuyuan Bridge | 120.905742 | 30.952843 | 67 | 60 | 63.5 |

| 266 | Lan Tsui Bridge | 120.897668 | 30.903937 | 66 | 60 | 63 |

| 267 | Datong Bridge | 120.884189 | 30.926954 | 66 | 60 | 63 |

| 268 | Yu Qing Tang | 120.903199 | 30.950705 | 69 | 60 | 64.5 |

| 269 | Shui Yang House | 120.903676 | 30.950638 | 65 | 53 | 59 |

| 270 | Tai’s House | 120.801496 | 30.891862 | 63 | 50 | 56.5 |

| 271 | Cannon House | 120.921783 | 30.852123 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| 272 | Sanlitang Bridge | 120.902565 | 30.961748 | 62 | 60 | 61 |

| 273 | Gangjiali Bridge | 120.848553 | 30.954163 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| 274 | Rentianbang Bridge | 120.970963 | 30.915933 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| 275 | Garden Road Small House | 120.923315 | 30.849051 | 67 | 70 | 68.5 |

| 276 | Protecting the Country with the Grain King Temple | 120.894692 | 30.950436 | 73 | 68 | 70.5 |

| 277 | Former Residence of Zhao Xianchu | 120.901417 | 30.952847 | 68 | 70 | 69 |

| 278 | Dongjiabang Dite | 120.936967 | 31.016308 | 78 | 38 | 58 |

| 279 | Chung Kai Fook Pharmacy | 120.90132 | 30.947119 | 68 | 60 | 64 |

| 280 | Ear Shun Bridge | 120.937393 | 31.001734 | 68 | 56 | 62 |

| 281 | Tsing Lung Bridge | 120.946497 | 30.84447 | 67 | 60 | 63.5 |

| 282 | Guangfu Bridge | 120.888313 | 30.856209 | 66 | 60 | 63 |

| 283 | Gu Family Hall and River Port | 120.949093 | 30.835458 | 68 | 55 | 61.5 |

| 284 | The Fei Family House | 120.920349 | 30.84427 | 60 | 45 | 52.5 |

References

- Meinig, D.W. Reading the landscape: An appreciation of WG Hoskins and JB Jackson. Interpret. Ordinary Landsc. Geogr. Essays 1979, 195–244. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J.B. Discovering the Vernacular Landscape, 1st ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1984; p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Eben Saleh, M.A. A1-Alkhalaf vernacular landscape: The planning and management of land in an insular context, Asir region, southwestern Saudi Arabia. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1996, 34, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. ICOMOS-IFLA Principles Concerning Rural Landscapes as Heritage. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/GA2017_6-3-1_RuralLandscapesPrinciples_EN_adopted-15122017.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Landscape Convention. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16807b6bc7 (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Jenkins, V. Protecting the natural and cultural heritage of local landscapes: Finding substance in law and legal decision making. Land Use Policy 2018, 73, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; van der Horst, D.; Schleyer, C.; Bieling, C. Sustaining ecosystem services in cultural landscapes. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R.; Selman, P. Landscape as a focus for integrating human and environmental processes. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 57, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.; Duncan, N. Landscapes of Privilege, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.; Wu, L.; Cai, J.; Li, D.; Chen, Q. Construction of Ecological and Recreation Patterns in Rural Landscape Space: A Case Study of the Dujiangyan Irrigation District in Chengdu, China. Land 2022, 11, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, A.; Kuttner, M.; Hainz-Renetzeder, C.; Konkoly-Gyuró, É.; Tirászi, Á.; Brandenburg, C.; Allex, B.; Ziener, K.; Wrbka, T. Assessment framework for landscape services in European cultural landscapes: An Austrian Hungarian case study. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 37, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, I.; Johnston, R.; Selby, K. Climate Change and Cultural Heritage: A Landscape Vulnerability Framework. Joural Isl. Coast. Archaeol. 2021, 16, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Chen, W. On the basic concepts and contents of ecological security. J. Appl. Ecol. 2002, 13, 354–358. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Du, P.; Guo, S.; Zhang, P.; Lin, C.; Tang, P.; Zhang, C. Monitoring land cover change and disturbance of the mount wutai world cultural landscape heritage protected area, based on remote Sensing time-Series images from 1987 to 2018. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, B. Ecological security pattern: A new idea for balancing regional development and ecological protection. A case study of the Jiaodong Peninsula, China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 26, e01472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, R. Cultural landscape security pattern: Concept and structure. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 1834–1842. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Yatra aur Tammanah Statement-Yatra: Our Purposeful Journey and Tammanah: Our Wishful Aspirations for Our Heritage on Learnings and Commitments from the Culturenature Journey. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/General_Assemblies/19th_Delhi_2017/19th_GA_Outcomes/ICOMOS_GA2017_CNJ_YatraStatement_final_EN_20180207circ.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- IUCN. Connecting Practice: Defining New Methods and Strategies to Support Nature and Culture through Engagement in the World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/our-work/protected-areas-and-land-use (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- ICOMOS. Connecting Practice: A Commentary on Nature-Culture Keywords, 1st ed.; ICOMOS International Secretariat: Paris, France, 2021; p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Q. The Formation and Development of the Tangpu Polder in the Taihu Region. Agric. Hist. China 1982, 2, 12–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, B. Development of Agriculture in the South of the Yangtze River 1620–1850, 1st ed.; Shanghai Classics Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2007; pp. 134–156. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Sun, C.; Zheng, X. Spatial and Temporal Evolution Assessment of Regional Ecological Risk Based on Adaptive Cycle Theory: A Case Study of Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 2609–2621. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, S.J.; Hayes, S.E.; Yoskowitz, D.; Smith, L.M.; Summers, J.K.; Russell, M.; Benson, W.H. Accounting for Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability: Linking Ecosystem Services to Human Well-Being. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1530–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Natural Resources of Zhejiang Province. Draft Territorial Spatial Master Plan for the Yangtze River Delta Eco-Green Integrated Development Demonstration Area (2019–2035). Available online: https://zrzyt.zj.gov.cn/art/2020/6/18/art_1289924_47444338.html (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Sauer, C.O. The morphology of landscape. Univ. Calif. Publ. Geogr. 1925, 2, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, K. Landscape and meaning: Context for a global discourse on cultural landscape values. In Managing Cultural Landscapes, 1st ed.; Taylor, K., Lennon, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Simensen, T.; Halvorsen, R.; Erikstad, L. Methods for landscape characterisation and mapping: A systematic review. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Yang, J.; Tang, W. Spatially explicit landscape-level ecological risks induced by land use and land cover change in a national ecologically representative region in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14192–14215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Planning an ecological network of Xiamen Island (China) using landscape metrics and network analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Hou, X.; Li, X.; Hou, W.; Nakaoka, M.; Yu, X. Ecological connectivity between land and sea: A review. Ecol. Res. 2018, 33, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Z.; Zou, X.; Zuo, P.; Song, Q.; Wang, C.; Wang, J. Impact of landscape patterns on ecological vulnerability and ecosystem service values: An empirical analysis of Yancheng Nature Reserve in China. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 72, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Yan, X.; Zhong, X. Landscape Pattern Vulnerability and Spatial Association Patterns in the Lower Liaohe Plain. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 247–257. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ran, P.; Hu, S.; Frazier, A.E.; Qu, S.; Yu, D.; Tong, L. Exploring changes in landscape ecological risk in the Yangtze River Economic Belt from a spatiotemporal perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 137, 108744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, B.; Li, X. Spatial and temporal patterns of landscape pattern vulnerability in the Yellow River Delta 2005–2018. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2021, 41, 258–266. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; You, N.; Meng, J. Dynamic ecological risk assessment and management of land use in the middle reaches of the Heihe River based on landscape patterns and spatial statistics. Sustainability 2016, 8, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Hu, X.; Zheng, X.; Hou, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Qiu, R.; Lin, J. Spatial variations in the relationships between road network and landscape ecological risks in the highest forest coverage region of China. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 96, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, C.; Chang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zang, F. Spatial-temporal pattern analysis of landscape ecological risk assessment based on land use/land cover change in Baishuijiang National nature reserve in Gansu Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 124, 107454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Tang, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Nie, Y.; Deng, W. Landscape Ecological Risk Assessment and Ecological Security Pattern Construction in Mountainous Resource-based Cities: The Case of Zhangjiajie City. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 1290–1299. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Han, F. Industrial Heritage Assessment & Strategy Generating System for the Former Industrial Districts in China: An Application of the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) Approach. China Anc. City 2018, 3, 16–26. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Romão, X.; Paupério, E.; Pereira, N. A framework for the simplified risk analysis of cultural heritage assets. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 20, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, S.; Pospisil, M. E-P Heritage Value Assessment Method Proposed Methodology for Assessing Heritage Value of Load-Bearing Structures. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2022, 16, 1621–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- ICOMOS(CHINA). Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China. Available online: http://www.iicc.org.cn/Publicity1Detail.aspx?aid=882 (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Armstrong, H.; Han, F. Landscape Heritage: Nature, Spirituality and Aesthetics in the West. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 33, 55–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Su, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Q. Designing Ecological Security Patterns Based on the Framework of Ecological Quality and Ecological Sensitivity: A Case Study of Jianghan Plain, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Ma, C.; Huang, P.; Guo, X. Ecological vulnerability assessment based on AHP-PSR method and analysis of its single parameter sensitivity and spatial autocorrelation for ecological protection—A case of Weifang City, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Song, W. Integrating potential ecosystem services losses into ecological risk assessment of land use changes: A case study on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 318, 115607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, M.; Tang, W.; Liu, W.; He, Y.; Zhu, Y. Spatial Identification of Ecological Risk Assessment and Ecological Restoration Based on Ecosystem Services Perspective: An Example from the Yangtze River Source Area. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 3846–3855. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Su, X.; Shen, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Wan, L.; Zhou, S.; Yang, M.; Wang, Q.; Liu, G. Identifying ecological security patterns based on ecosystem services is a significative practice for sustainable development in Southwest China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 9, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Institute of Rural Reconstruction. Recording and Using Indigenous Knowledge: A Manual. Available online: https://iirr.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Recording-and-Using-Indigenous-Knowledges-A-Manual.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Boven, K.; Morohashi, J. Best Practices Using Indigenous Knowledge, 1st ed.; Nuffic: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).