Abstract

In recent years, several biblical gardens were constructed in the harsh climate of Poland. They try to convey spiritual values through the medium of garden art and design. Rarely are they built from scratch with a granted budget; the majority of them represent the effort to revitalize degraded urban space and cultural heritage. In most cases, they are constructed and maintained as a challenge by groups of enthusiasts with no institutional financial help. From the very beginning, they are attracting numerous visitors, individuals, and organized groups to previously neglected spaces. The scope of this paper is to present the phenomenon of their construction, discuss the selected case studies, and try to identify whether their creation is strengthening the resilience of cultural landscapes.

1. Introduction

There are three gardens presented in the Bible—the Garden of Eden, the Garden of Gethsemane, and the Garden of the Empty Tomb. The most appealing for humankind is the Garden of Eden. The challenge to reconstruct it has lasted as long as humankind; however, the gardens officially described as biblical did not emerge until the XIX or even XX century.

First “biblical gardens“ or “Bible gardens“ were created in an Anglo-American Protestant context [,]. The synonymous names represented a garden with plants that are specifically mentioned within the pages of the Bible []. The story of biblical gardens is connected to the development of modern botanical science and the identification, acclimatization, and popularization of plants native to the Middle East in the XVII–XIX centuries [].

The oldest remark of a “bible garden” appears in the title of the work by Joseph Taylor “The Bible garden or a familiar description of the trees (…) mentioned in the Holy Scripture” published in London in 1836.

The first recognition of “biblical garden” referred to an existing biblical garden in Carmel, California, USA, and was published in a book in 1940 [,]. The first information about the biblical garden in Europe in Bangor, UK, designed by Tatham Whitehead, appeared in 1961 []. Since then, many biblical gardens have emerged across the US and Europe. In recent years, several were created in the harsh climate of Poland. The scope of this paper is to present the selected case studies and try to identify if their creation is strengthening the resilience of cultural landscapes.

2. Material and Methods

The research objective was to identify whether and how the creation of biblical gardens is strengthening the resilience of cultural landscapes. The subject is complicated and concerns various fields—land development and urban planning, cultural and social studies, spirituality and religion, placemaking, landscape architecture and resilience, therefore various methods needed to be used.

This study encompassed a review of the literature dedicated to biblical gardens and their design as well as public perception of places dedicated to materializing the Bible.

Studies of biblical gardens required field trips, site mapping, and observations. Studies of the public perception of biblical gardens were based on a literature review, research of social media, and interviews with all interested parties, i.e., designers, gardeners, visitors, volunteers, and users. The biblical garden in Northern Poland, in Gdańsk, was selected as a case study.

The first step was to establish what is a biblical garden and why it is different from any other garden.

3. Biblical Gardens in the World–Descriptions and Definitions

Zofia Włodarczyk reviewed some 63 Bible gardens from Europe and coined a modern definition of a biblical garden []. She points to the fact that the selection of plants in contemporary biblical gardens is based not entirely on biblical plants but includes also many other ornamental species from other parts of the world. Some of the herbs are a reference to monastic, medieval European gardens or are associated with the wider Christian tradition or grow widely in Israel []. However, Zofia Włodarczyk insists on the preservation of the original principle to use merely plants mentioned in the Bible, with only a small addition of wild-growing plants that are native to Israel, as the objective is to show the natural landscapes of the Holy Land [].

Botanists have identified about 100 known plant species mentioned in the Bible and there is an ongoing debate about another possible 100 plant species, as not all terms referring to plants can be easily identified [,]. Thus, the list of biblical species is subject to constant verification. The most current list, which contains 206 species of Bible plants, is accepted by contemporary researchers and may be used as a basis for the selection of plants when arranging biblical plant collections or gardens []. Most of the plants mentioned in the Scripture can be planted in colder climates; therefore, it is also possible to cultivate biblical plants in Europe and North America [,]. Some of them were introduced to other continents and become so omnipresent that they have multiple common names in local languages, e.g., Acorus calamus L., called sweet flag, sway, or muskrat root.

Appendix A presents the list of those 206 species of bible plants, accompanied by local common names in English and Polish if they exist. The local common names signify that the plant is present in local culture. Either way, it can be successfully planted in the garden, domesticated and planted in pots, or at least some parts of the plant are widely known and used. These plants that can be potentially used in temperate climate zone are shaded; they may be potentially used in biblical gardens in Poland (Appendix A).

Another common feature of biblical gardens is that they present plants along with their names and at least one Bible quote.

Apart from planting material, modern biblical gardens use compositional layouts referencing religious symbols, miniature landscapes, and structures that occur in the Holy Land as well as paintings, works of sculpture, music, and garden designs presenting selected biblical events []. They also usually offer printed guides, leaflets, or electronic devices, and some biblical gardens also employ human guides. With the help of symbolic representations and traditional and modern technologies, they convey the message behind the words of the Holy Script and thus invite meditation and reflection.

Zofia Włodarczyk [] coined a modern definition of the biblical garden as “an arranged area of greenery, in which, with the help of various means of expression, a scenery reflecting the environmental and economic reality of the Holy Land is created to facilitate the reading of a biblical text, and through this a deeper and more precise understanding and knowledge thereof”. Apart from biblical gardens, other denominations are also used, e.g., the garden of Christ, the biblical garden of Moses, the biblical plant collection, etc.

Thus, nowadays biblical gardens are themed gardens, both didactic and symbolic. They present species of plants mentioned in the Bible (Appendix A) and one or more of the following features:

- Plants that grow in the wild in the Middle East (native to places mentioned in the Bible);

- Plants that are related to Christian symbolism;

- Symbolic features related to the Holy Scripture or Christianity;

- Symbolic features representing scenes from the Bible.

- Some biblical gardens, especially in the US, offer one or more additional experiences:

- Performance re-enacting the scenes from the Bible;

- Biblical kitchen serving traditional dishes from the Middle East prepared with native plants—vegetables, fruits, and herbs;

- Biblical Museum.

James Bielo describes biblical gardens as choreographed spaces to teach where sensuality—visuality, tactility, physical movement, taste, smell, and aurality—is integral to their effectiveness []. The Bible gardens are designed to be experienced with all the senses simultaneously, with no priority given to any of them. These places invite visitors to stroll along the walkways, sit on the bench, smell the aromatic plants, touch the leaves and flowers, and enjoy the experience while learning the message of the Holy Script. Biblical gardens are pedagogical guides to discovering the history and truth of the Bible.

4. The Social and Health Effects of Biblical Gardens

The interesting question is what distinguishes the biblical garden from a secular one in its social or health effect? The answer is rooted in the interconnection between the spiritual and material world. Spirituality is a multidimensional theoretical construct. In essence, it constitutes transcendence understood as going beyond or above oneself to experience closeness to a higher power or purpose. In the case of biblical gardens, that turn toward transcendence and a higher-being makes a common denominator for many concepts of spirituality and religiosity, so that they may be treated interchangeably. Biblical gardens are places of spiritual experience stimulated by the material environment. That spiritual experience may have a positive effect on health and mental well-being. There are numerous studies confirming significant relationships between spirituality, health-related behaviors, and psychological well-being [,]. A systematic review of the literature performed by Mueller, Plevak, and Rummans (2001) demonstrated that religious involvement and spirituality are associated with better health outcomes including greater longevity, coping skills, and less anxiety, depression, and suicide []. A scoping review that explored the associations between religious and spiritual factors and the health-related outcomes of adolescents with chronic illnesses suggested that religious and spiritual beliefs, thoughts, and practices (e.g., spiritual coping activities) might have both beneficial and deleterious effects on the way adolescents deal with their medical conditions, on their psychosocial adjustment, their mental and physical health, and their adherence to treatments []. Religiosity and spirituality are providing adolescents and adults with both cognitive and social resources that might help them to find purpose and hope, even in difficult times. The reference to the sacred, which encompasses the transcendent and divine, might stimulate resilience, understood as resources, to withstand hardships, bounce back and reconstruct oneself.

5. Biblical Gardens in the World—Locations

The majority of biblical gardens are constructed in the northern hemisphere, in the US and Europe, but there are also very interesting ones in other parts of the world, namely in Israel (the largest biblical garden—Neot Kedumim, the Biblical Landscape Reserve in Israel), but also southern America and Asia, Africa, and Australia.

When it comes to location, biblical gardens are constructed:

- Next to churches, synagogues, or chapels;

- As parts of botanic gardens;

- As individually themed gardens or public parks.

James Bielo created a project “Materializing the Bible” to track biblical gardens along with Creationist sites and Bible history museums. His team created an interactive map of biblical gardens and other biblical sites available on the internet (Figure 1) []. Professor James Bielo identified 182 existent biblical gardens located in Australia, Austria, Canada, Croatia, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Scotland, Switzerland, Ukraine, the United States, and Wales. However, the number of attractions related to materializing the Bible is much higher—516 in 44 different nations around the world [].

Figure 1.

A map of the world. Each individual dot represents historic, existing, or planned biblical garden or other sites related to materializing the Bible. Legend: Yellow = Re-Creations; Green = Biblical gardens; Red = Creationist sites; Purple = Bible History Museums; Lavender = Non-Extant sites. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Ref. []. 2022, James Bielo, Materializing the Bible.

The Bible gardens try to immerse visitors into the Bible’s natural world. Biblical gardens do not have to mimic the Christian Holy Land, nor provide a surrogate pilgrimage experience. They do materialize the Bible but in a very subtle way, taking advantage of all available media.

6. Biblical Gardens in Poland

In Poland, the first collection of biblical plants was opened in the botanical garden of the Agricultural University in Cracow in 2000 []. The collection was organized by Zofia Włodarczyk, who also mentioned the name “ogród biblijny” for the first time in 2002 in her doctoral thesis “Plants of biblical gardens” []. Zofia Włodarczyk was also the designer of the first biblical garden in Poland in Proszowice, near Cracow in Poland, which opened in 2008 [] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

First biblical garden in Poland was created in Proszowice, near Cracow in 2006 (a) place to sit and rest under the tree canopy; (b) main pathway; (c) sensory pathway. Source: author.

Since then, several biblical gardens were constructed in various regions of the country. The collections of biblical plants were opened to visitors in:

- Botanical Gardens of the Agricultural University in Cracow [];

- Botanical Gardens of Jagiellonian University in Cracow [];

- Botanical Gardens of UCMS in Lublin [], turned into a biblical garden;

- Arboretum in Bolestraszyce [].

Existent biblical gardens in Poland that are officially referred to as biblical gardens and have a dedicated internet site are located in:

- Proszowice [];

- Myczkowce [];

- Muszyna [];

- Cracow—Dębniki—Łosiówka [,];

- Chorzów [];

- Stara Wieś [];

- Częstochowa [];

- Lublin [];

- Puławy [];

- Lidzbark Warmiński [];

- Gdańsk [].

Poland has a moderate climate in central Europe, but winters are usually cold and snowy, with temperatures well below freezing. Some biblical plants that do not support harsh winters need to be grown in containers or replaced with related species of similar appearance. Some need to be transferred to interiors with stable temperatures and humidity during the winter. A list of potential biblical plants is presented in Table A1.

The Bible gardens in Poland usually offer:

- Plants that grow in the wild in the Middle East (native to places mentioned in the Bible);

- Plants that are related to Christian symbolism;

- Symbolic features related to the Holy Scripture or Christianity;

- Symbolic features representing scenes from the Bible.

The other additional features are rarely present. The performances re-enacting the events presented in the Bible are only organized for Christmas or Easter in some places, but that is not a usual practice. So far, there are no biblical cuisines or Bible museums in biblical gardens in Poland. The Bible gardens in Poland are not constructed near cemeteries, like many in other countries. They do not bear plaques with the name of the founder who paid for the construction. The founders are usually anonymous, even though the names of the design team members might be publicly revealed.

Biblical gardens in Poland are rarely built from scratch with a granted budget, such as in the case of Proszowice [] or Myczkowce []. In most cases, they are constructed and maintained as an uproot challenge by groups of enthusiasts with no institutional financial help.

From the very beginning, biblical gardens in Poland try to convey spiritual values through the medium of garden art and design and attract numerous visitors, individuals, and organized groups to previously neglected spaces. Some of them represent the effort to revitalize cultural heritage, such as the example of Gdańsk [].

7. The Biblical Garden of Pallottine Missionary Sisters in Gdańsk

On the property belonging to the Pallottine Missionary Sisters (Figure 3 and Figure 4), there was an area of undeveloped land on a slope reinforced with the old foundations of demolished additions to the historic villa; today it is the Integration Center. The sisters decided to convert this terraced area on the escarpment into the Bible Garden. The garden was founded in 2019 by two Pallottine Sisters: Sister Blanka Sławińska SAC and Sister Beata Ostrówka SAC, later they were also joined by Sisters Aleksandra Podleżańska SAC and Barbara Brodowska SAC. The sisters established the garden practically on their own, with the help of kind people, scouts, etc. The garden was established and is maintained exclusively with funds donated by private founders. Every season the garden is expanded with new compositions related to the history of Salvation (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17) [].

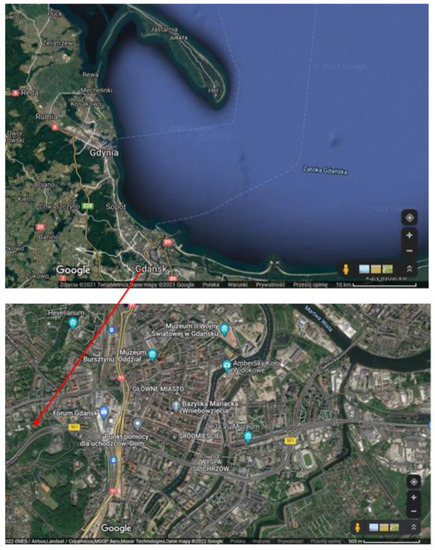

Figure 3.

Case study location—Biblical garden in Gdańsk, ul. Malczewskiego 144 Map of Gdańsk Bay, source [].

Figure 4.

Airview of the biblical garden in Gdańsk, ul. Malczewskiego 144, photo by Kamil Sulewski, Reprinted/adapted with permission from Ref. []. 2022, Kamil Sulewski, 7 zdjęć z Gdańska.

7.1. Design and Layout of the Biblical Garden

The sloped terraced garden was divided into parts with references to the events of the Old and New Testaments. The Bible Garden is adjacent to an older garden next to the congregation house, which has a small plot of vegetable and herbal plants and ornamental plants. All the plants merge into one picturesque garden full of colors and fragrances (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6).

The garden is attractive at any time of the year, but is open to visitors from June to the end of October for security reasons (Figure 4). In the upper part of the garden, there is a historic villa, which now serves as the Integration Center, where exhibitions and cultural events are organized.

Figure 5.

The view from the upper terrace down to the slope of the biblical garden, in the background a vegetable garden located below by the white building of the main house of the Pallottine Sisters. In the foreground, we can see an array of biblical crops, e.g., proso millet, wheat, and barley. Source: author.

Figure 6.

In the foreground, the colorful biblical garden. In the background, the recently renovated historic villa. Today it is the Integration Center where events and exhibitions are organized. Source: author.

7.2. Plants in the Biblical Garden

The goal of the Pallottine Sisters was to establish a garden where everyone would find a sense of peace, the beauty of nature, and closeness to God and other people. It seems that this goal has been perfectly achieved. The biblical garden of the Pallottine Sisters is organized according to similar principles as other biblical gardens in the world. It presents species of plants mentioned in the Bible and has all of the following features:

Plants of the Middle East were planted in the garden—those that had been acclimatized in Poland directly to the ground, and the more sensitive varieties—in pots placed in the garden in the summer season.

Figure 7.

Against the wall of a historic villa, an exhibition of sensitive plants grown in pots is placed only during the summer, e.g., fig tree, dates and citron. In front of the pots, the allegory of 10 virgins and their oil lamps. From the garden terraces, there is an exceptionally attractive view of the historic towers of the Main Town in Gdańsk. Source: author.

Many other species in the garden serve as the backdrop for biblical stories.

The form of presenting information about the plants is also visually attractive. Next to biblical plants, there are plates with names, descriptions, and photos of the plants flowering, which is a great educational aid and support in contemplating the beauty of nature.

Figure 8.

A table with the name and description of the plant and its photo in full bloom located next to crops from the Middle East, e.g., variety of leeks and common flax. Source: author.

Figure 9.

The sisters took care of a garden corner with a map of the Holy Land and tables with the main plants found in the Bible. Source: author.

7.3. The Main Symbolic Elements of the Biblical Garden in Gdańsk

When arranging the scenes, the Sisters used both plant material and symbolic elements. They use natural stones, sculptures, and seasonal decorations—gifts from people, stonemasons, and contractors. This allows the garden to be attractive all year round. Elements symbolizing animals, loaves of bread, dishes, etc., are an excellent addition to planting (Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 13 and Figure 17).

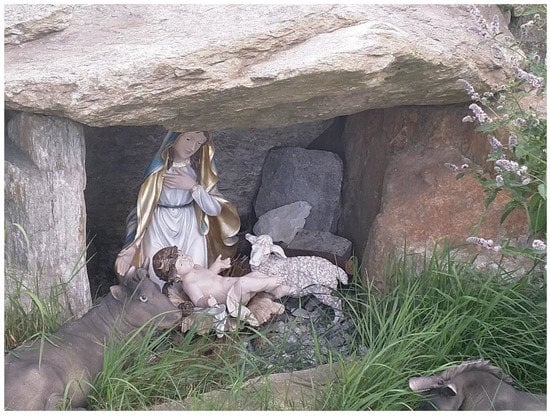

Figure 10.

The grotto with a Holy Mother and Child surrounded by animals. Source: author.

Figure 11.

Biblical Scene—Emaus arranged using a fragment of the terrace of a demolished annex from a historic villa Source: author.

They help to make the message more attractive to different age groups, especially children. The use of diverse measures allowed the Pallottine Sisters to arrange the garden with narrative properties that speak of the “history of salvation”. The multisensory qualities make it easier for visitors to receive the content that materializes the Bible in the garden.

Figure 12.

Symbolic grotto of an empty tomb, next to which the plants of the Middle East are described. Source: author.

Figure 13.

Garden as a place of contemplation of biblical events—Crown of Thorns. Source: author.

At the same time, the general perception of the garden is dominated by contact with living plants, and references to biblical scenes are somewhat hidden, so that following them can become a contemplative walk. The garden was established with great care and attention to detail. It is very elegant and well-kept.

7.4. Elements of Street and Garden Furniture

It can be said that everyone will find something interesting in this garden: children —figurines of birds, hares, and dogs; young people and adults—terrace garden attractions, biblical scenes, and an attractive view; the elderly can appreciate the amenities—an elevator, ramps, and comfortable benches (Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16), but also the planting of older plant varieties that evoke memories of youth. The walkways and benches are invitations to spend more time in the biblical garden [].

Figure 14.

Garden view. The view from the upper terrace down to the slope of the biblical garden, in the background the white building of the main house of the Pallottine Sisters. In the foreground, a bench between two decorative vases. Source: author.

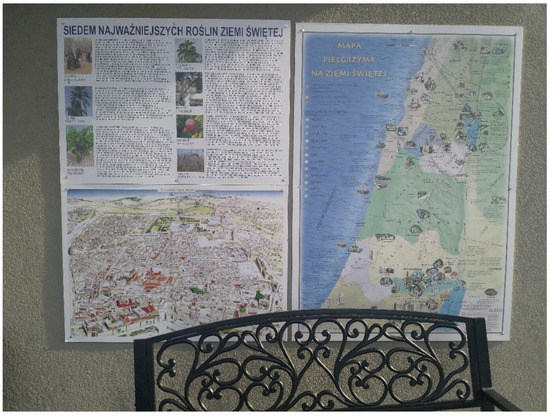

Figure 15.

Leisure area next to the wall on which boards with maps of the Holy Land and plants mentioned in the text of the Bible were hung. Source: author.

Figure 16.

A bench under a tree. Source: author.

Figure 17.

A scene representing Kafarnaum with a dry lake, fisherman boat, nets, and fresh fish. Source: author.

8. Discussion

As more and more biblical gardens are created, the interesting question is why are they created? What kind of needs are they fulfilling? When it comes to pure aesthetic values, some representations in biblical gardens are contested by art connoisseurs. They are criticized as ludic, erratic, and simplified. This might be connected with the challenge to materialize and domesticate the Scriptures, and appeal to all age groups—children, adults, and the elderly.

James Bielo states that biblical gardens are places for prayer, meditation, silent reflection, and contemplation [,]. However, he argues that biblical gardens resist a modern ideology that elevates visual experience atop a sensory hierarchy [,]. The multisensory experience united with an invitation to meditational or contemplative practices can be translated into more resilient cultural landscapes.

Scheurer [] wrote that biblical gardens were “a niche offering a positive space of resistance against the constant increasing of efficiency, the absolute power of the media and the vertiginous pace of life”. The resistance to elevate visual experience over spiritual needs provides a healing refuge in a world pushed towards constant progress and perfection. Religious roots can give strength in the search for the meaning of life. The biblical garden can become a “space of spiritual rest, similar to an imagining of paradise” []. Today, a man is pushed into the role of a consumer in restless circumstances. The possibility to either create a biblical garden, be a member of a team, or care for biblical plants can lead to spiritual healing and internal transformation. The contact with nature, observation of seasonal decay, and revival of planting material bring joy and contentment [,]. The healing power of nature, garden, and gardening were mentioned as early as the 12th century by Saint Hildegard of Bingen []. A visit to a Bible garden encourages self-reflection and self-awareness. The modern man faced with the biblical garden might be forced to ask himself many fundamental questions about truth, its price, and the sense of the sacrifices made by the prophets. That truth makes man truly free [].

Another interesting question is whether the creation of biblical gardens is strengthening the resilience of cultural landscapes.

8.1. Biblical Gardens and the Sense of Belonging and Connectedness

Biblical gardens create a religious attraction. They are usually open to the public and visited daily by everyone who wants to, including the local community and other visitors. What is important is that biblical gardens around the globe offer free admission to everyone and everyone is welcomed during opening hours. It is an inclusive experience.

In the case of biblical gardens, they might create a sense of belonging and connectedness for a community, fostering social cohesion and inclusion through the power of place []. A place becomes meaningful if there are memories and values associated with it. James Bielo suggests that the biblical garden can be understood and treated as a gift to local communities and the general public []. The Bible gardens connect past and future generations. The ancient plants look and smell exactly the same as they did in biblical times. Some biblical gardens form part of ecumenical gardens, e.g., Le Jardin de las Tres Culturas in Madrid and Gärten der Weltreligionen: Paradiesgarten Christlich-Judischer Garten in Osnabrück [,].

8.2. Public Perception of the Garden in Gdańsk

The garden was opened to the public in 2019, during the pandemic of COVID-19. Therefore, it was not possible to organize a large opening event. However, information about the garden appeared in the local press and on the web pages of The Pallottine Sisters Congregation. Information about the biblical garden is also regularly updated on social media.

Nevertheless, over twenty spontaneous interviews with neighbors and local inhabitants revealed the lack of knowledge about the opening of the biblical garden in Gdańsk.

During the study visits, the methods of site observation, mapping the activity of visitors, and unstructured interviews were used. The study revealed that there are four types of visitors:

- Pallottine Sisters who live in the Congregation Home;

- Guests of Pallottine Sisters who live in the Congregation Home (refugees with children, pensioners, vacationers, etc.);

- People who are frequenting the Integration Centre, which hosts numerous organized events;

- Visitors who come directly to visit the garden and who planned their visit to the garden.

The perception of the garden is positive, it is described as a beautiful and peaceful place. The Pallottine Sisters and their adult guests use the terrace and stroll along the alleys. Children explore the garden, play in open areas and interact with the whimsical features, e.g., sculptures, gates, etc. Some of the people who visited the Integration Centre, and who learn about the garden on site, decided to dedicate additional time to visit the garden. Visitors who come directly to visit the garden come from various parts of the country, e.g., southern Poland, and planned to visit the garden ahead of their trip to Gdańsk. The garden is open to visitors from the 1st May to the 31st October, and the Pallottine Sisters serve as guides, providing information and insights about the garden design.

9. Conclusions

What is important in the case of biblical gardens, constructed as a challenge without institutional help, is the sense of involvement and responsibility. It is believed that the public’s participation and involvement, as well as their needs and satisfaction, are critical components of the gardens’ sustainability. Their participation could bridge the gap between various groups and help articulate commonly shared values. Therefore, the sensory hierarchy and feeling of homeliness are more important than a purely visual experience. The elevation of modern impeccable aesthetics might bring divisions and a sense of exclusion, while the tendency to decorate according to users’ needs brings a sense of commitment and homeliness. Forging connections between people who are significantly different usually starts by seeking similarities. The biblical garden is a neutral ground that represents common values.

The garden in Gdańsk united many people who engaged themselves in decorating, maintaining, or promoting the garden in the media. The garden has so far attracted many visitors from the entire country, even though it had been created only recently (2019–2022). In some cases, it becomes a reason to visit the Integration Center and Pallottine Sisters. The biblical garden has quickly become one of the tourist attractions of Gdańsk, even though the tourism sector is recuperating after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The example of biblical gardens in Poland demonstrates that they can become an important feature of the local community, bringing people together and giving meaning to their environment. However, they need efforts to popularize the knowledge about their presence and invite people to visit. Moreover, they offer the potential of strengthening a place’s identity and the resilience of the cultural landscape.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Pallottine Sisters in Gdańsk.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of universally accepted biblical plants, published by Zofia Włodarczyk [], with common names in English and Polish and references to geographic distribution.

Table A1.

List of universally accepted biblical plants, published by Zofia Włodarczyk [], with common names in English and Polish and references to geographic distribution.

| No | Latin Name of Species | English Common Name | Polish Common Name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abies cilicica (Ant. & Ky) Carr | Cilician fir Taurus fir | Jodła Syryjska | Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey |

| 2 | Acacia albida Delile Syn. Faidherbia albida (Delile) A.Chev. | Syria, Palestine and Cyprus, tropical and subtropical Africa | ||

| 3 | Acacia raddiana Savi | - | - | Africa, Middle East |

| 4 | Acacia tortilis (Forssk.) Hayne | - | - | Africa, Middle East |

| 5 | Acanthus syriacus Boiss | - | Akant syryjski | Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey |

| 6 | Acorus calamus L. | Sweet flag, sway, muskrat root | Tatarak zwyczajny | Central Asia, Siberia, Europe and Northern America—invasive species in Europe |

| 7 | Agrostemma githago L. | Common corn-cockle | Kąkol polny | Middle East, Northern Africa, Europe, United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand |

| 8 | Alcea setosa (Boiss.) Alef. | Bristly hollyhock | Malwa figolistna | Native to Middle East; garden plant in Europe, Northern Africa, Asia |

| 9 | Alhagi maurorum Medik. | Camelthorn, camelthorn bush, Caspian manna, Persian mannaplant | - | Mediterranean, Middle East, introduced to Australia, southern Africa, United States |

| 10 | Allium cepa L. | Onion | Cebula zwyczajna | Cultivated around the world |

| 11 | Allium kurrat Schweinf. ex Krause | Egyptian Leek | Por egipski | Cultivated around the world |

| 12 | Allium porrum L. | Wild Leek | Por uprawny | Cultivated around the world |

| 13 | Allium sativum L. | Garlic | Czosnek pospolity | Cultivated around the world |

| 14 | Aloe succotrina Lam. | Fynbos aloe | Aloes sokotrzański | Southern Africa, easily grown as ornamental plant in Mediterranean climate and in containers |

| 17 | Anemone coronaria L. | Poppy anemone, Spanish marigold, windflower | Zawilec wieńscowy | Native to Mediterranean and Middle East, cultivated around the world |

| 18 | Anethum graveolens L. | Dill | Koper ogrodowy | Cultivated around the world |

| 19 | Anthemis palaestina Reut. | Cota palestina | Rumian palestyński | Mediterranean |

| 20 | Aquilaria agallocha Roxb. | Lign aloes, Lign-aloes trees | Southeast Asia | |

| 21 | Artemisia herba-alba Asso | White wormwood | Mediterranean, Middle East, Southern Europe, cultivated around the world | |

| 22 | Artemisia judaica L. | Mediterranean, Middle East, Northern Africa | ||

| 23 | Arundo donax L. | Giant cane, elephant grass, carrizo, arundo, Spanish cane, Colorado river reed, wild cane, giant reed | Lasecznica trzcinowata arundo trzcinowate | Asia, Northern Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Southern and Northern America, Southern Europe, considered invasive in some parts of the world |

| 24 | Astragalus bethlehemiticus Boiss. | Israel | ||

| 25 | Astragalus gummifer Labill. | Tragacanth, gum tragacanth milkvetch | Traganek gumodajny | Western Asia |

| 26 | Atriplex halimus L. | Mediterranean saltbush, sea orache (orach), shrubby orache (orach), silvery orache (orach) | Łoboda solniskowa | Africa, Middle East, Southern Europe, cultivated around the world |

| 27 | Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile | Egyptian balsam, desert date, soap berry tree or bush, thron tree, Egyptian myrobalan, Egyptian balsam, zachum oil tree | Kolibło egipskie | Africa, Middle East |

| 28 | Boswellia papyrifera (Delile) Hochst. | Sudanese frankincense | Africa | |

| 29 | Boswellia sacra Flueck. | Frankincense, Olibanum tree | Kadzidło Cartera, Kadzidłowiec Cartera | Parts of Africa and Arabian Peninsula |

| 30 | Boswellia thurifera Roxb. | Kadzidłowiec | India and Punjab region | |

| 31 | Brassica nigra (L.) Koch | Black mustard | Kapusta czarna, kapusta gorczyca, gorczyca czarna | Northern Africa, Asia, Europe, cultivated around the world, invasive species in Northern America |

| 32 | Butomus umbellatus L. | Flowering rush, Grass rush | Łączeń baldaszkowy | Asia, Europe, Northern Africa, invasive species in Northern America |

| 33 | Buxus sempervirens L. | Common box, European box, Boxwood | Bukszpan zwyczajny bukszpan wiecznie zielony | Africa, Middle East, Southern Europe, ornamental plant around the world |

| 34 | Calotropis procera R. Br. | Dead Sea apple, apple of Sodom, Sodom apple King’s crown, rubber bush, rubber tree | Mleczara wyniosła | Africa, Asia |

| 35 | Calycotome villosa (Poir.) Link | Hairy thorny broom, Spiny broom | Mediterranean | |

| 36 | Capparis spinosa L. | Caper bush, Flinders rose | Kapar ciernisty | Mediterranean, Middle East, Asia, cultivated around the world |

| 37 | Cassia senna L. | Alexandrian senna | Strączyniec ostrolistny, Kasja ostrolistna, siężybób ostrolistny, Senes ostrolistny | Middle East, Africa, Asia Cultivated as ornamental plant |

| 38 | Cedrus libani Barrel. | Cedar of Lebanon, Lebanese cedar | Cedr libański | Mediterranean, cultivated as ornamental plant |

| 39 | Centaurea iberica Trev. ex Spreng. | Iberian knapweed, Iberian star-thistle | Chaber gwieździsty | Parts of Asia and Europe, cultivated as Ornamental plant invasive species in Northern America |

| 40 | Cephalaria syriaca (L.) Schrad. | Głowaczek syryjski | Northern Africa, Middle East, Southern Europe | |

| 41 | Ceratonia siliqua L. | Carob | Szarańczyn strąkowy, drzewo karobowe, karob, ceratonia | Native and cultivated in the Mediterranean and Middle East, ornamental plant for temperate regions around the world |

| 42 | Cercis siliquastrum L. | Judas tree Judas-tree | Judaszowiec południowy, judaszowiec wschodni | Middle East, Southern Europe, Africa and Northern America, ornamental plant for temperate regions around the world |

| 43 | Chrysanthemum coronarium L. | Garland chrysanthemum, chrysanthemum greens, edible chrysanthemum, crowndaisy chrysanthemum, chop suey greens, crown daisy, Japanese greens | Złocień wieńcowy | Mediterranean and Middle East, Asia, parts of Africa, Europe, Northern, and Southern Americas, ornamental plant around the world |

| 44 | Cicer arietinum L. | Chickpea, chick pea | Ciecierzyca pospolita | Cultivated around the world |

| 45 | Cichorium intybus L. | Common chicory | Cykoria podróżnik, podróżnik błękitny | Cultivated around the world |

| 46 | Cichorium pumilum Jacq. | Cultivated around the world | ||

| 47 | Cinnamomum cassia Blume | Cinnamomum | Cynamonowiec wonny | Parts of Asia |

| 48 | Cinnamomum zeylanicum Nees | Cynamonowiec | Parts of Asia | |

| 49 | Cistanche tubulosa (Schenk) Wight | Parts of Asia and Africa | ||

| 50 | Cistus incanus L. | Hoary rock-rose | Czystek szary Czystek siwy | Middle East, Southern Europe, ornamental plant for temperate regions around the world |

| 51 | Cistus laurifolius L. | Laurel-leaf cistus, Laurel-leaved cistus, Laurel-leaved rock rose | Czystek wawrzynolistny | Mediterranean |

| 52 | Cistus salviifolius L. | Sage-leaved rock-rose, Salvia cistus, Gallipoli rose | Czystek szałwiolistny | Mediterranean, southern Europe, parts of Western Asia and Northern Africa, ornamental plant around the world |

| 53 | Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. | Abu Jahl’s melon, colocynth, bitter apple, bitter cucumber, egusi, vine of Sodom, wild gourd | Arbuz kolokwinta, kawon kolokwinta, kolocynta | Africa, Asia, Southern Europe, Australia, cultivated around the world in warm climates |

| 54 | Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Mansf | Watermelon | Arbuz zwyczajny, kawon | Africa, cultivated in warm climates |

| 55 | Citrus medica L. | Citron, cedrate | Cytron, cedrat | Parts of Asia, Southern Europe |

| 56 | Commiphora abyssinica (Berg.) Engl. | Abyssinian myrrh, Yemen myrrh | Balsamowiec mirra | Middle East, Africa |

| 57 | Commiphora africana (Arn.) Engl. | African myrrh | sub-Saharan Africa | |

| 58 | Commiphora gileadensis (L.) Christ | Arabian balsam tree | Balsamowiec właściwy | Africa and Middle East |

| 59 | Commiphora kataf (Forssk.) Engl. | Africa and Middle East | ||

| 60 | Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl. | Myrrh, African myrrh, Herabol myrrh, Somali myrrhor, common myrrh | Africa and Middle East | |

| 61 | Conium maculatum L. | Hemlock, poison hemlock, wild hemlock | Szczwół Plamisty, Pietrasznik Plamisty, Psia Pietruszka, Świńska Wesz, Weszka, Szaleń Plamisty | Omnipresent, invasive in some parts of the world |

| 62 | Coriandrum sativum L. | Coriander, Chinese parsley, dhania, cilantro | Kolendra siewna | Mediterranean, cultivated around the world |

| 63 | Crocus sativus L. | saffron crocus, autumn crocus | Szafran uprawny, Krokus uprawny, Szafran siewny | Cultivated around the world |

| 64 | Cucumis melo L. | Melon | melon | Cultivated around the world |

| 65 | Cuminum cyminum L. | Cumin | Kmin, Kmin rzymski, kumin, kmin egipski, kmin pluskwi | Cultivated around the world |

| 66 | Cupressus sempervirens L. | Mediterranean cypress, Italian cypress, Tuscan cypress, Persian cypress, pencil pine | Cyprys wiecznie zielony | Mediterranean, ornamental plant for temperate regions around the world |

| 67 | Curcuma longa L. | Turmeric | Kurkuma, kurkuma długa, Ostryż indyjski, szafran indyjski, ostryż długi, Ostryż zohary | Cultivated in temperate regions around the world |

| 68 | Cymbopogon martinii Stapf | Palmarosa, palm rose, Indian geranium, gingergrass, rosha, Rosha grass | Palczatka imbirowa | India, cultivated in temperate regions around the world |

| 69 | Cymbopogon schoenanthus Spreng. | Camel grass, camel’s hay, fever grass, geranium grass, West Indian lemongrass | Palczatka wełnista | Africa, Middle East, cultivated in temperate regions around the world |

| 70 | Cynomorium coccineum L. | Cynomorium szkarłatne | Mediterranean, Middle East | |

| 71 | Cyperus papyrus L. | Papyrus, papyrus sedge, paper reed, Indian matting plant, Nile grass | Cibora papirusowa | Africa, cultivated in temperate regions around the world, domestic plant in containers |

| 72 | Dalbergia melanoxylon Guill. & Perr. | African blackwood, grenadilla, mpingo | Dalbergia czarnodrzew kostrączyna czarna | Africa, Asia |

| 73 | Diospyros ebenum Koenig | Ceylon ebony | Hurma hebanowa | India, Sri Lanka |

| 74 | Echinops viscosus DC. | Mediterranean, Middle East | ||

| 75 | Eruca sativa Mill. | Arugula, rocket, rucola | Rokietta siewna rukola | Mediterranean, Middle East, cultivated around the world |

| 76 | Eryngium creticum Lam. | Field eryngo | Mikołajek kreteński | Mediterranean, Middle East, |

| 77 | Ferula galbaniflua Boiss. & Buhse | Ferula | Zapaliczka | Mediterranean, Middle East, |

| 78 | Ficus carica L. | Fig | Figowiec pospolity | Mediterranean, Middle East, cultivated in temperate regions around the world |

| 79 | Ficus sycomorus L. | Sycamore fig, fig-mulberry, sycamore, sycomor, | Figowiec sykomora, sykomora | Africa, Arabian Peninsula, cultivated in temperate regions around the world |

| 80 | Fraxinus syriaca Boiss. | Jesion syryjski | Mediterranean | |

| 81 | Gossypium herbaceum L. | Levant cotton | Bawełna indyjska | Africa, Asia, cultivated in temperate regions around the world |

| 82 | Gundelia tournefortii L. | Asia, cultivated in temperate regions around the world | ||

| 83 | Haloxylon persicum Bunge | White saxaul | Saksauł biały | Asia |

| 84 | Hammada salicornica (Moq.) Iljin | Africa | ||

| 85 | Hammada scoparia (Pomel) Iljin | Africa | ||

| 86 | Hedera helix L. | Common ivy, English ivy, European ivy, ivy | Bluszcz pospolity | Asia, Europe, ornamental plant around the world, invasive in some parts of the world |

| 87 | Hordeum distichon L. | Common barley, two-rowed barley | Jęczmień dwurzędowy | Cultivated around the world |

| 88 | Hordeum hexastichon L. | Jęczmień ozimy, jęczmień sześciorzędowy | Cultivated around the world | |

| 89 | Hordeum vulgare L. | Barley | Jęczmień zwyczajny | Cultivated around the world |

| 90 | Hyoscyamus aureus L. | Lulek złoty | Mediterranean, Middle East, Europe | |

| 91 | Hyoscyamus muticus L. | Egyptian henbane | Lulek | Mediterranean, Middle East, Europe |

| 92 | Iris pseudacorus L. | Yellow flag, yellow iris, water flag | Kosaciec żółty | Omnipresent |

| 93 | Juglans regia L. | Persian walnut, English walnut, Carpathian walnut, Madeira walnut, common walnut | Orzech Włoski | Asia, Europe, cultivated around the world |

| 94 | Juncus maritimus Lam. | Sea rush | Sit morski | Africa, Asia, Europe, parts of America |

| 95 | Juniperus excelsa Bieb. | Greek juniper, Persian juniper | Jałowiec grecki, jałowiec wyniosły | Mediterranean |

| 96 | Juniperus phoenica L. | Phoenicean juniper, Arâr | Jałowiec fenicki | Mediterranean |

| 97 | Lactuca sativa L. | Lettuce | Sałata siewna | Cultivated around the world |

| 98 | Lagenaria siceraria (Mol.) Standl. | Calabash bottle gourd, white-flowered gourd, long melon, birdhouse gourd, New Guinea bean, Tasmania bean, opo squash | Tykwa pospolita, kalebasa | Africa, Asia, Southern and Northern America |

| 99 | Laurus nobilis L. | Laurel, bay tree, bay laurel, sweet bay, true laurel, Grecian laurel | Wawrzyn szlachetny, laur | Mediterranean, ornamental plant for temperate regions around the world, domesticated plant in containers |

| 100 | Lawsonia inermis L. | Hina, the henna tree, the mignonette tree, the Egyptian privet | Lawsonia bezbronna | Africa, Asia, ornamental plant for tropical regions around the world |

| 101 | Lens culinaris Medik. | Lentil | Soczewica jadalna | Cultivated around the world |

| 102 | Lilium candidum L. | Lilium candidum, the Madonna lily, white lily | Lilia biała, lilia świętego Józefa | Cultivated around the world |

| 103 | Linum usitatissimum L. | Flax, common flax linseed | Len zwyczajny | Cultivated around the world |

| 104 | Liquidambar orientalis Mill. | Oriental sweetgum, Turkish sweetgum | Ambrowiec wschodni | Mediterranean |

| 105 | Lolium temulentum L. | Darnel, poison darnel, darnel ryegrass, cockle | życica roczna | Omnipresent |

| 106 | Loranthus acaciae Zucc. | Acacia strap flower | Gązewnik akacjowy | Mediterranean, Middle East |

| 107 | Lycium europaeum L. | European tea tree, European box-thorn, European matrimony-vine | Kolcowój europejski | Africa, Asia, Europe |

| 108 | Majorana syriaca (L.) Rafin. | Majeranek arabski | Mediterranean, Middle East | |

| 109 | Malus sylvestris Mill. | European crab apple | Jabłoń dzika, płonka | Europe, cultivated around the world |

| 110 | Malva nicaeensis All. | Bull mallow, French mallow | Ślaz nicejski | Mediterranean, Middle East |

| 111 | Malva sylvestris L. | Common mallow | Ślaz dziki, malwa dzika | Omnipresent |

| 112 | Mandragora officinarum L. | Mediterranean mandrake | Mandragora lekarska | Mediterranean, cultivated around the world |

| 113 | Mentha longifolia L. | Horse mint, fillymint, St. John’s horsemint | Mięta długolistna | Afrcia, Europe, Asia, cultivated around the world |

| 114 | Morus alba L. | White mulberry, common mulberry, silkworm mulberry | Morwa biała | Cultivated around the world in temperate climates |

| 115 | Morus nigra L. | Black mulberry, Blackberry | Morwa czarna | Mediterranean, Asia, cultivated around the world in temperate climates |

| 116 | Myrtus communis L. | Common myrtle, true myrtle | Mirt zwyczajny | Mediterranean, cultivated around the world in mild climates |

| 117 | Narcissus tazetta L. | Paperwhite, bunch-flowered narcissus, bunch-flowered daffodil, Chinese sacred lily, cream narcissus, joss flower, polyanthus narcissus | Narcyz wielokwiatowy | Mediterranean, cultivated around the world |

| 118 | Nardostachys jatamansi (D. Don) DC. | |||

| 119 | Nerium oleander L. | Oleander nerium | Oleander pospolity | Mediterranean, cultivated around the world in mild climates |

| 120 | Nigella sativa L. | Black caraway, black cumin, nigella | Czarnuszka siewna | Mediterranean, cultivated around the world |

| 121 | Notobasis syriaca (L.) Cass. | Syrian thistle | Notobasis syryjski | Mediterranean |

| 122 | Nymphaea alba L. | White water lily, European white water lily, white nenuphar | Grzybienie białe | Mediterranean, ornamental plant around the world |

| 123 | Nymphaea caerulea Sav. | Grzybienie błękitne, lotos błękitny | Africa, Asia, ornamental plant around the world | |

| 124 | Nymphaea lotus L. | White Egyptian lotus, tiger lotus, white lotus Egyptian white water-lily | Grzybienie egipskie | Africa, Asia, ornamental plant around the world |

| 125 | Ochradenus baccatus Delile | Ochradenus jagodowy | Middle East | |

| 126 | Olea europaea L. | Olive | Oliwka europejska oliwnik europejski, oliwka uprawna, drzewo oliwne | Mediterranean, cultivated around the world in mild climates |

| 127 | Ornithogalum narbonense L. | Narbonne star-of-Bethlehem, pyramidal star-of-Bethlehem, southern star-of-Bethlehem | Śniedek narboński | Mediterranean |

| 128 | Ornithogalum umbellatum L. | Garden star-of-Bethlehem, grass lily, nap-at-noon, eleven o’clock lady | Śniedek baldaszkowaty | Europe, parts of Africa and Asia, ornamental plant around the world |

| 129 | Paliurus spina-christi Mill. | Jerusalem thorn, garland thorn, Christ’s thorn, Crown of thorns | Dwukolczak śródziemnomorski | Northern Africa, Europe, Asia, cultivated around the world |

| 130 | Pancratium maritimum L. | Sea daffodil | Pankracjum nadmorskie | Mediterranean, ornamental plant around the world in mild climates |

| 131 | Panicum miliaceum L. | Proso millet | Proso zwyczajne, proso właściwe | Cultivated around the world |

| 132 | Papaver rhoeas L. | Common poppy, corn rose | Mak polny | Omnipresent, cultivated around the world |

| 133 | Phoenix dactylifera L. | Date palm | Daktylowiec właściwy | Cultivated around the world in mild climates |

| 134 | Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin ex Steud. | Common reed | Trzcina pospolita | Omnipresent |

| 135 | Pinus brutia Ten. | Turkish pine | Sosna kalabryjska | Mediterranean, cultivated around the world in mild climates |

| 136 | Pinus halepensis Mill. | Aleppo pine, Jerusalem pine | Sosna alepska | Mediterranean |

| 137 | Pinus pinea L. | Stone pine | Sosna pinia | Mediterranean |

| 138 | Pistacia atlantica Desf. | Mt. Atlas mastic tree, Persian turpentine tree | Pistacja atlantycka | Mediterranean, Middle East, ornamental plant around the world in mild climates |

| 139 | Pistacia lentiscus L. | Lentisk, mastic | Pistacja kleista, pistacja lentyszek, lentyszek | Mediterranean, cultivated around the world in mild climates |

| 140 | Pistacia palaestina Boiss. | Terebinth, Turpentine tree | Pistacja palestyńska, terebint | Mediterranean |

| 141 | Pistacia vera L. | Pistachio | Pistacja właściwa | Central Asia, Middle East, ornamental plant around the world in mild climates |

| 142 | Platanus orientalis L. | Old World sycamore, Oriental plane | Platan wschodni | Mediterranean, ornamental plant around the world |

| 143 | Populus alba L. | Silver poplar, silverleaf poplar, white poplar | Topola biała, białodrzew | Asia, Africa, Europe, omnipresent |

| 144 | Populus euphratica Oliv. | Desert poplar, poplar diversifolia | Topola eufracka | Northern Africa, Middle East, Central Asia |

| 145 | Portulaca oleracea L. | Little hogweed pursley | Portulaka pospolita, portulaka warzywna | Omnipresent |

| 146 | Prunus armeniaca L. | Apricot | Morela pospolita | Cultivated around the world |

| 147 | Prunus dulcis D.A. Webb | Almond | Śliwa migdał | Northern Africa, Middle East, Central Asia, Southern Europe, cultivated around the world |

| 148 | Pterocarpus santalinus L. | Saunderswood, red sandalwood | Pterokarpus sandałowy | India, cultivated around the world |

| 149 | Punica granatum L. | Pomegranate | Granat właściwy, granatowiec właściwy | Mediterranean, cultivated around the world in mild climates |

| 150 | Quercus calliprinos Webb | Palestine oak | Dąb skalny, dąb kermesowy | Mediterranean |

| 151 | Quercus ithaburensis Decne. | Mount Tabor oak | Dąb tabor | Mediterranean, Middle East |

| 152 | Ranunculus asiaticus L. | Persian buttercup | Jaskier azjatycki | Mediterranean, ornamental plant around the world |

| 153 | Reichardia tingitana (L.) Roth | False sowthistle | Mediterranean | |

| 154 | Retama raetam (Forssk.) Webb | Janowiec retam, retam | Northern Africa, Middle East | |

| 155 | Rhamnus palaestina Boiss. | Szakłak palestyński | Middle East | |

| 156 | Ricinus communis L. | Castor oil plant | Rącznik pospolity | Mediterranean, ornamental plant around the world |

| 157 | Rosa canina L. | Dog rose | Róża dzika | Omnipresent |

| 158 | Rosa phoenicia L. | Mediterranean | ||

| 159 | Rubia tinctorum L. | Rose madder, Common madder, dyer’s madder | Marzanna barwierska, m. farbiarska, barwica | Asia, Europe, cultivated around the world |

| 160 | Rubus sanguineus Friv | Holy bramble | Jeżyna krwista | Parts of Asia and Europe |

| 161 | Ruta chalepensis L. | Mediterranean | ||

| 162 | Salicornia fruticosa (L.) | Soliród krzaczasty | Mediterranean | |

| 163 | Salix acmophylla Boiss. | Brook willow | Central Asia, Middle East | |

| 164 | Salix alba L. | White willow | Wierzba biała, wierzba srebrna, wierzba pospolita | Europe, Asia, Northern Africa |

| 165 | Salsola inermis Forssk. | Saltwort | Solanka bezbronna | Europe, Asia, Northern Africa |

| 166 | Salsola kali L. | Prickly glasswort, Prickly saltwort | Solanka kolczysta | Europe, Asia, Northern Africa |

| 167 | Salvia judaica Boiss. | Szałwia judejska | Mediterranean | |

| 168 | Sarcopoterium spinosum (L.) Sp. | Thorny burnet | Krwiściąg ciernisty | Mediterranean |

| 169 | Saussurea lappa (Decne.) C.B. Clarke | Mediterranean | ||

| 170 | Scirpus lacustris L. | Lakeshore bulrush | Oczeret jeziorny, sitowie jeziorne | Omnipresent |

| 171 | Scolymus hispanicus L. | Common golden thistle | Mediterranean | |

| 172 | Scolymus maculatus L. | Spotted golden thistle | Skolymus plamisty | Mediterranean, Middle East |

| 173 | Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. | Blessed milkthistle, Saint Mary’s thistle | Ostropest plamisty | Mediterranean, omnipresent, cultivated around the world |

| 174 | Sinapis alba L. | White mustard | Gorczyca biała, gorczyca jasna | Cultivated around the world |

| 175 | Sinapis arvensis L. | Wild mustard | Gorczyca polna, ognicha | Cultivated around the world |

| 176 | Solanum incanum L. | Thorn apple | Psianka szara | Africa, Middle East |

| 177 | Sonchus oleraceus L. | Soft thistle | Mlecz zwyczajny | Omnipresent |

| 178 | Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench | Great millet | Sorgo dwubarwne | Africa, cultivated around the world in warm climates |

| 179 | Styrax officinalis L. | Styrak lekarski | Southern Europe and the Middle East, cultivated around the world | |

| 180 | Suaeda palaestina Eig. & Zoh. | Palestine | ||

| 181 | Tamarix aphylla (L.) Karst. | Athel tree | Tamaryszek bezlistny | Africa, Middle East, Asia |

| 182 | Tamarix mannifera (Ehrenb.) Bunge | Middle East | ||

| 183 | Taraxacum officinale Weber | Dandelion | Mniszek pospolity | Omnipresent in temperate climate zone |

| 184 | Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Mast. | Thuja articulata | Cyprzyk czteroklapowy | Northern Africa |

| 185 | Thymelaea hirsuta (L.) Endl. | Mediterranean | ||

| 186 | Trigonella foenum-graecum L. | Fenugreek | Kozieradka pospolita | Europe, Asia, cultivated around the world |

| 187 | Triticum aestivum L. | Common wheat | Pszenica zwyczajna | Cultivated around the world |

| 188 | Triticum dicoccum Schrank | Pszenica płaskurka | Cultivated around the world | |

| 189 | Triticum durum Desf. | Durum | Pszenica twarda | Cultivated around the world |

| 190 | Triticum turgidum L. | Pszenica szorstka | ||

| 191 | Tulipa montana Lindl. | Tulipan górski | Cultivated around the world | |

| 192 | Tulipa sharonensis Dinsm. | Mediterranean | ||

| 193 | Typha domingensis (Pers.) Poir. ex Steud. Typha latifolia L. | Southern cattail | Pałka południowa | Omnipresent |

| 194 | Ulmus canescens Melv. | Grey elm | Mediterranean | |

| 195 | Urginea maritima Baker | Mediterranean | ||

| 196 | Urtica pilulifera L. | Roman nettle | Pokrzywa kuleczkowata | Omnipresent |

| 197 | Urtica urens L. | Annual nettle | Pokrzywa żegawka | Omnipresent |

| 198 | Verbascum sinaiticum Benth. | Dziewanna synajska | Africa, Middle East | |

| 199 | Viburnum tinus L. | Laurestine | Kalina wawrzynowata | Mediterranean, ornamental plant around the world |

| 200 | Vicia faba L. | Broad bean | Wyka bób, bób | cultivated around the world |

| 201 | Vitis vinifera L. | Common grape vine | Winorośl właściwa | Mediterranean, Middle East, cultivated around the world |

| 202 | Zilla spinosa (L.) Prantl | Mediterranean, Middle East | ||

| 203 | Ziziphus lotus (L.) Lam. | Głożyna afrykańska | Southern Europe, Africa, Middle East | |

| 204 | Ziziphus spina-christi (L.) Desf. | Christ’s thorn jujube | Głożyna cierń Chrystusa | Africa, Middle East, cultivated around the world |

| 205 | Zostera marina L. | Eelgrass | Zostera morska, tasiemnica morska | Africa, Northern America, Asia, Europe |

| 206 | Zygophyllum dumosum Boiss. | Bushy bean-caper | Parolist krzaczasty | Middle East |

Grey fields—plants that can be potentially planted in the ground in temperate climate zone. Green fields—plants that may be planted in pots and transferred to the garden in the summer in temperate climate.

References

- Stückrath, K. Bibelgärten. Entstehung, Gestalt, Bedeutung, Funktion und Interdiszipplinäre Perspektiven; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Doktorarbeit zu Bibelgärten. Available online: https://www.bibelgarten.info/Doktorarbeit_zu_Bibelg%C3%A4rten.html (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Włodarczyk, Z. Biblical garden—A review, characteristics and definition based on twenty years of research. Folia Hortic. 2018, 30, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielo, J.S. Biblical Gardens and the Sensuality of Religious Pedagogy. Mater. Relig. 2018, 14, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk, Z. Biblical Gardens in dissemination of ideas of the Holy Scripture. Folia Hortic. Ann. 2004, 16, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- King, E.A. Plants of the Holy Scriptures: With a Check-List of Plants That Are Mentioned in the Bible; New York Botanical Garden: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Włodarczyk, Z. Review of plant species cited in the Bible. Folia Hortic. Ann. 2007, 19, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bożek, A.; Nowak, P.F.; Blukacz, M. The relationship between spirituality, health-related behavior, and psychological well-being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotton, S.; Zebracki, K.; Rosenthal, S.L.; Tsevat, J.; Drotar, D. Religion/Spirituality and Adolescent Health Outcomes: A Review. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 38, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, P.S.; Plevak, D.J.; Rummans, T.A. Religious involvement, spirituality, and medicine: Implications for clinical practice. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2001, 76, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannello, N.M.; Inguglia, C.; Silletti, F.; Albiero, P.; Cassibba, R.; Lo Coco, A.; Musso, P. How Do Religiosity and Spirituality Associate with Health-Related Outcomes of Adolescents with Chronic Illnesses? A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Materializing the Bible. Available online: https://www.materializingthebible.com/map.html (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Włodarczyk, Z. Undated Polskie Ogrody Biblijne. Available online: https://urk.edu.pl/index/site/3354/5840 (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Biblical Garden in Proszowice, Poland. Available online: https://www.malopolskiszlakogrodow.pl/ogrod/26-ogrod-biblijny (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Collection of Biblical Plants in the UJ Botanical Garden in Cracow, Poland. Available online: https://ogrod.uj.edu.pl/ogrod-old/rosliny/pozostale-kolekcje (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Collection of Biblical Plants in the UMCS Botanical Garden in Lublin, Poland. Available online: https://www.umcs.pl/pl/ogrod-biblijny,4301.htm (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Collection of Biblical Plants in Bolestraszyce, Poland. Available online: https://bolestraszyce.com.pl/kolekcje/kolekcja-roslin-biblijnych/ (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Biblical Garden in Myczkowce, Poland. Available online: https://myczkowce.org.pl/oferta-osrodka/ogrod-biblijny (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Biblical Garden in Muszyna, Poland. Available online: https://www.malopolskiszlakogrodow.pl/ogrod/20-ogrod-biblijny (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Biblical Garden in Kraków-Łosiówka, Poland. Available online: https://losiowka.sdb.org.pl/bractwo-milosnikow-ogrodu-boga/ (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Biblical Garden in Kraków-Łosiówka, Poland. Available online: https://podrozenaemeryturze.wordpress.com/2018/07/01/ogrod-biblijny-krakow/ (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Biblical Garden in Chorzów. Available online: https://www.jadwiga.info/2013/06/ogrod-biblijny-zwiedzanie-20-22-wrzesnia/ (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Biblical Garden in Stara Wieś. Available online: https://starawies.jezuici.pl/ogrod-biblijny/ (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Biblical Garden in Częstochowa, Poland. Available online: https://www.biblical-gardens.com (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Biblical Garden in Puławy, Poland. Available online: http://www.parafia-lidzbark.pl/pages/ogrod-biblijny (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Biblical Garden in Lidzbark Warmiński, Poland. Available online: http://www.parafia-lidzbark.pl/pages/ogrod-biblijny (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Biblical Garden in Gdańsk, Poland. Available online: https://ogrod-biblijny-w-gdansku.business.site/ (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Adapted map of Gdańsk retrieved from the Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.pl/maps/@54.5610737,18.6134622,67014m/data=!3m1!1e3 (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Sulewski, K. 7 Zdjęc z Gdańska. Available online: https://7zdjeczgdanska.pl/2020/08/schowany-pelen-kwiatow-i-spokoju-ogrod-z-wspanialym-widokiem-na-gdansk.html (accessed on 31 December 2022).

- Scheuer, H. Religion und Gartenkunst im Dialog. In Der Moses-Bibelgarten in Jägerwirth, Kultur im Landkreis Passau; Mendl, H., Ed.; Landkreis Passau Kulturreferat: Salzweg, Germany, 2008; pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- König, H.A. Der Bibelgarten der Markusgemeinde; Evangelische Markusgemeinde: Düsseldorfer, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter, A.U.; Grahn, P. What makes a garden a healing garden? J. Ther. Hortic. 2002, 13, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hildegard of Bingen (Saint Hildegard). Tłumaczenie Jurczyński Jacek SDB—Praktyczny Poradnik Zdrowego Życia (XI Century); Wydawnictwo M: Krakow, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen, D. Sagen, was ist. In Propheten im Garten. Bilder und Texte zu den Skulpturen im Bibelgarten des Johannisklosters Schleswig; Dreisatz GmbH: Schleswig, Germany, 2003; pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rostami, R.; Lamit, H.; Khoshnava, S.M.; Rostami, R.; Rosley, M.S.F. Sustainable Cities and the Contribution of Historical Urban Green Spaces: A Case Study of Historical Persian Gardens. Sustainability 2015, 7, 13290–13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrody Biblijne. Available online: http://projektowanie.ogrodow.com/blog/ogrody-biblijne/ (accessed on 30 November 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).