Abstract

To address the challenge of predicting runoff processes in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River under the influence of complex river–lake relationships and human disturbances, this paper proposes a coupled model based on the Sparrow Search Algorithm-optimized Long Short-Term Memory neural network (SSA-LSTM) for daily runoff forecasting at the Jiujiang Hydrological Station. The input data were preprocessed through feature selection and sequence decomposition. Subsequently, the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA) was utilized to perform automated of key hyperparameters of the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model, thereby enhancing the model’s adaptability under complex hydrological conditions. Experimental results based on multi-station hydrological and meteorological data of the middle reaches of the Yangtze River from 2009 to 2016 show that the SSA-LSTM achieves a Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) of 0.98 during the testing period (2016). The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) are reduced by 49.3% and 51.3%, respectively, compared to the standard LSTM. A comprehensive evaluation across different flow levels, utilizing Taylor diagrams and error distribution analysis, further confirms the model’s robustness. The model demonstrates robust performance across different flow regimes: compared to the standard LSTM model, SSA-LSTM improves the NSE from 0.45 to 0.88 in high-flow scenarios, exhibiting excellent capabilities in peak flow prediction and flood process characterization. In low-flow scenarios, the NSE is improved from −0.77 to 0.72, indicating more reliable prediction of baseflow mechanisms. The study demonstrates that SSA-LSTM can effectively capture hydrological nonlinear characteristics under strong river–lake backwater and human disturbances, providing a high-precision and high-efficiency data-driven method for runoff prediction in complex basins.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, influenced by both natural and anthropogenic factors, the hydrological regime in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River has undergone intensified variations, leading to frequent floods and droughts [1,2]. Downstream of Yichang, the river gradient decreases and flow velocity slows. While downstream of Zhicheng, the river is flanked by levees and connected to numerous lakes of varying sizes, resulting in a highly complex river–lake relationship. The river–lake composite system in the middle Yangtze is influenced by the spatial heterogeneity of climatic conditions, intricate river–lake interactions, and human activities such as the operation of the Three Gorges Dam (TGD) and sand mining [3]. Particularly in the confluence area of the Yangtze River and Poyang Lake, hydrological and hydrodynamic processes exhibit complex nonlinear characteristics. Jiujiang hydrological station, located on the mainstem of the Yangtze River near the outlet of Poyang Lake, is a critical node for studying the water exchange between the Yangtze River and Poyang Lake. The water level and discharge of Jiujiang Station are crucial for accurately simulating and interpreting the complex hydrodynamic interactions between the Yangtze River and Poyang Lake. Its runoff process is simultaneously affected by the mainstem flow of the Yangtze River and the outflow from Poyang Lake, posing challenges to the performance of traditional hydrological models in simulation and forecasting [4]. Therefore, accurately predicting the daily runoff at Jiujiang Station is not only a key to revealing the complex hydrodynamic interactions in the region, but also a challenging task to address the increasingly severe risks of floods and droughts and ensure the water security of the basin.

Traditional process-driven models, such as HEC-HMS and SWAT, typically feature relatively fixed structures. When simulating complex hydrological systems like the middle Yangtze River, which are affected by multiple interacting factors, these models frequently suffer from issues like high parameter sensitivity, complex calibration processes, and high computational costs [5,6]. In contrast, data-driven models offer advantages including high simulation accuracy, fast computation speed, and strong capability in handling large datasets. Machine learning methods, in particular, have been shown to not rely on explicit descriptions of physical processes but instead automatically learn complex mappings between inputs and outputs through iterative training from data [7], making them effective techniques for elucidating hidden relationships within complex nonlinear systems [8]. In recent years, machine learning techniques have developed rapidly in the fields of hydrology and hydrodynamics, finding widespread application in areas such as regional rainfall-runoff modeling, water level prediction, and discharge forecasting [9,10,11]. Machine learning methods can process complex nonlinear relationships within a short time frame and learn the underlying patterns from vast amounts of data, thereby improving predict ion accuracy and efficiency [12,13,14]. Systematic studies on the evolution of the river–lake system in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River have shown that under the combined influence of intensive human activities such as the TGD and extreme climate events, the regional water-sediment conditions, river–lake erosion–deposition patterns, and their interactions have undergone significant changes. This has directly intensified the nonlinearity and uncertainty of hydrological processes [15]. Given the characteristics of the Yangtze River mainstem, the requirement for long-term simulation, and the driving effects of factors like rainfall variability and reservoir operations on river discharge, employing machine learning methods to predict the rainfall-runoff process in the Yangtze River Basin is an effective approach [16,17].

Among various machine learning models, the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network has been widely applied to the modeling and forecasting of hydrological time series [18,19,20]. LSTM is capable of effectively modeling long-term and complex nonlinear interactions among multiple variables. Owing to its unique gating mechanism, it can efficiently capture long-term dependencies within time series, thereby reducing simulation time and improving simulation accuracy [21,22]. However, although LSTM models have demonstrated stability and accuracy advantages in runoff simulation in other basins, their applicability in runoff forecasting for complex systems such as the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, which are influenced by strong river–lake backwater and human activities, still requires in-depth exploration and verification [23,24]. Improvement research on LSTM (such as coupling it with decomposition algorithms) has become a cutting-edge direction for enhancing prediction accuracy [25]. In addition, the predictive performance of LSTM models is highly dependent on their hyperparameter configuration, such as the number of hidden layers, the number of neurons, and the learning rate [26,27]. Traditional hyperparameter optimization methods, like grid search and random search, suffer from limitations such as high computational cost or an inability to efficiently find the global optimum [28]. To overcome this bottleneck, metaheuristic optimization algorithms have been introduced for hyperparameter tuning of machine learning models [29]. Among them, the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA) is a metaheuristic algorithm that simulates the foraging and anti-predation behaviors of sparrow populations. It exhibits a certain degree of global search capability and convergence, making it suitable for solving various optimization problems [30]. SSA achieves a balance between global exploration and local exploitation through a collaborative mechanism involving “discoverers, followers, and vigilants” [30], which is crucial for finding the optimal configuration for LSTM models within high-dimensional hyperparameter spaces [28,31].

Therefore, this study focused on daily runoff forecasting at Jiujiang Station in the middle Yangtze River, a site subject to complex river–lake backwater effects and anthropogenic disturbances. To address this challenge, we constructed and validated a forecasting framework. We employed the SSA to adaptively determine the parameters for Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) preprocessing, and to automatically optimize the hyperparameters of the LSTM model. This SSA-VMD-LSTM framework is designed to enhance the model’s adaptability to the complex hydrological dynamics at Jiujiang Station, leading to more accurate and robust runoff predictions.

2. Materials and Methods

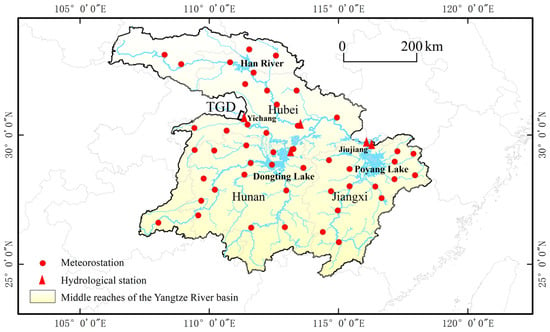

2.1. Study Area and Data

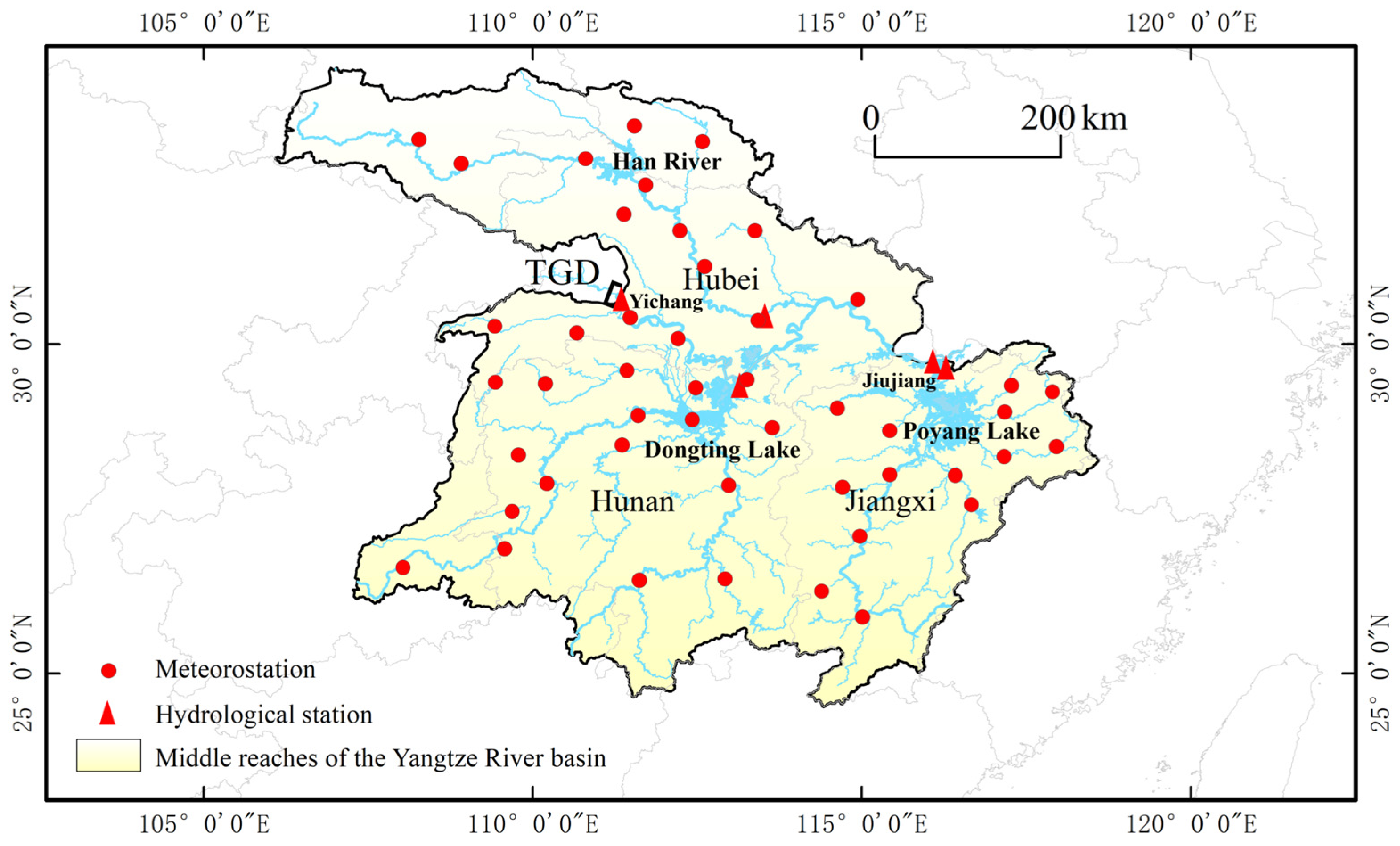

The Yichang-to-Hukou section of the Yangtze River constitutes its middle reach (Figure 1), spanning approximately 955 km in length and draining a basin area of about 680,000 km2. The majority of this basin lies within the East Asian monsoon region, characterized by a distinct monsoon climate with complex and variable regional weather patterns. The basin’s climate is influenced by the duration of rain belt stagnation, the progression and retreat of monsoons, and the timing—whether early or late—of the alternation between summer and winter monsoons. Consequently, aberrant monsoon behavior can lead to the concurrence of storm rainfall and flooding, resulting in severe flood disasters. Since the operation of the TGD, the Yangtze River–Poyang Lake relationship has undergone new adjustments, leading to significant changes in hydrological regimes [32,33]. The hydrological processes in this region are characterized by pronounced nonlinearity, largely due to the dynamic river–lake interactions. The backwater effect from Poyang Lake on the Yangtze River is nonlinearly modulated by the river–lake discharge ratio, leading to complex and significant intra-annual variations in hydraulic gradients near Jiujiang [34].

Figure 1.

The river network in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, as well as the locations of meteorological and hydrological stations.

This study selected the daily discharge data of the Jiujiang hydrological station in the middle Yangtze as the research subject, based on the station’s pivotal role in the complex river–lake system of the Yangtze River–Poyang Lake basin. The water level and discharge data from the Jiujiang Station provided critical input for simulations of the water level, flow rate, and water exchange dynamics between the Yangtze River and Poyang Lake, which are vital for accurately modeling the complex hydrodynamic interactions between the river and the lake.

This study primarily utilized hydrological and meteorological data for the period from 2009 to 2016 (Table 1). Daily outflow data for the Yichang and Jiujiang hydrological stations were provided by the Changjiang Water Resources Commission of the Ministry of Water Resources. The daily discharge data of Jiujiang Station, obtained from the Changjiang Water Resources Commission, have undergone necessary rating curve adjustments during the study period to ensure consistency. The observed daily flows at the Chenglingji and Xiantao hydrological stations are available from the Hubei Hydrology and Water Resources Center. Daily outflow data for the Three Gorges Dam were supplied by the China Three Gorges Corporation. Missing values, which accounted for less than 0.5% of all data, were interpolated using a cubic spline function. This method is known for its convergent properties with respect to both the function and its derivative. Quality-controlled daily precipitation data from meteorological stations across the Middle Yangtze River Basin were obtained from the National Climate Center of the China Meteorological All data were divided into a training set (2009–2014), a validation set (2015), and a test set (2016) in chronological order. To mitigate the impact of different variable dimensions on model training, all input data were normalized [35]. The 8-year dataset (2009–2016) includes a range of hydrological extremes and typical conditions, providing a representative sample for training short-term forecasting models.

Table 1.

Data collection list.

2.2. Coupled Model Construction and Scenario Design

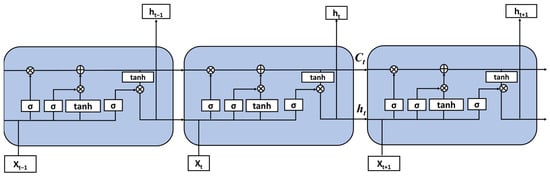

2.2.1. LSTM

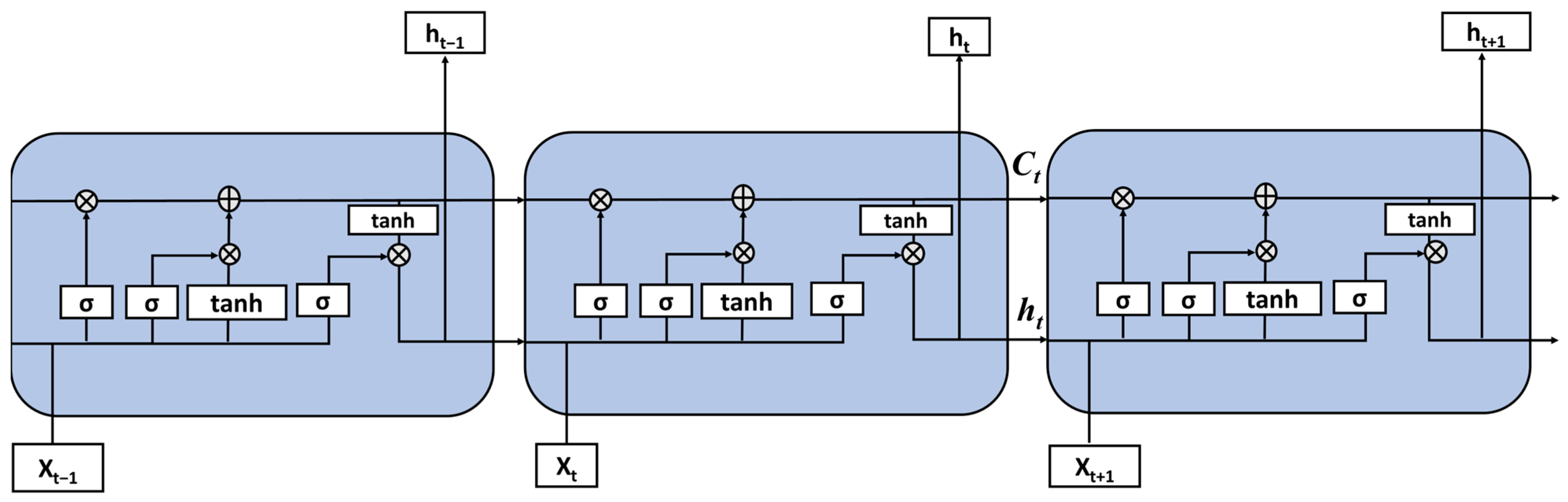

LSTM, proposed by Hochreiter & Schmidhuber [36], is a complex recurrent model widely used for simulating and predicting hydrological time series to address the vanishing and exploding gradient problems in RNN models [37,38].

By employing the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) method, a recurrent neural network with memory function, and setting control units, it effectively solves the vanishing gradient problem and achieves long-term memory effects, thereby improving the accuracy of simulation and prediction. LSTM has strong ability to fit time series relationships, making it particularly suitable for simulating and predicting the complex time series process of watershed runoff generation and concentration [19,39]. The composition of the LSTM network includes input gate i, forget gate f, memory cell C, and output gate o (Figure 2).

where is the input vector at time step . is the hidden state (output) from the previous time step . denotes the sigmoid activation function, controlling the extent to which information passes through the gates. denotes the hyperbolic tangent activation function. are the weight matrices for the forget gate, input gate, cell candidate, and output gate, respectively. are the bias vectors for the respective gates. represents the Hadamard product (element-wise multiplication). denotes the concatenation of the two vectors.

Figure 2.

Principle of LSTM model.

In this study, the input of the LSTM model was runoff and precipitation, and the output was the runoff forecast value at the current time. The input-output structure of the LSTM network was designed based on hydrological considerations of the study area. Specifically, the historical time window was set to 10 days, a choice informed by the approximate flood wave propagation time from Yichang to Jiujiang under typical flow conditions. Importantly, no same-day observational data were used as input, ensuring the model’s operational feasibility for forecasting. This configuration enables the model to effectively capture the integrated effects of TGD operations and tributary inflows on the discharge regime at Jiujiang Station.

2.2.2. SSA

SSA mimics mechanisms such as sparrow foraging behavior, interaction behavior, flight and position changes, adaptive evaluation, and knowledge updating, effectively exploring optimal or near-optimal solutions within the solution space. The algorithm demonstrates good global search capability and convergence, making it suitable for handling various optimization problems. In SSA, sparrows with higher fitness (discoverers) have priority in the process of searching for food. Discoverers not only guide the population to find food sources but also indicate the direction for all joiners, thus possessing a broader search range [30]. The position update mechanism of discoverers in each iteration is described as follows:

Update the location of new joiners:

Update the location of sparrows that are aware of the danger:

In this model, represents the position of the -th sparrow in the -th dimension during the -th iteration. is the upper limit of the number of iterations. is a random value within the interval [0, 1]. is a random number within the interval [0, 1], representing the warning value. is a constant value between [0.5, 1], representing the safety value. is a random value following a normal distribution. is a 1 × d matrix with all elements equal to 1. represents the individual with the lowest fitness in the -th iteration. denotes the position of the current best discoverer. is a 1 × d matrix whose elements are randomly assigned as 1 or −1. . is a normally distributed random number with a mean of 0 and a variance of 1 is a random number within the interval [−1, 1], used to indicate the direction and step size of the sparrow’s movement. represents the fitness of the current individual, and is the current maximum fitness value. is the current minimum fitness value [30].

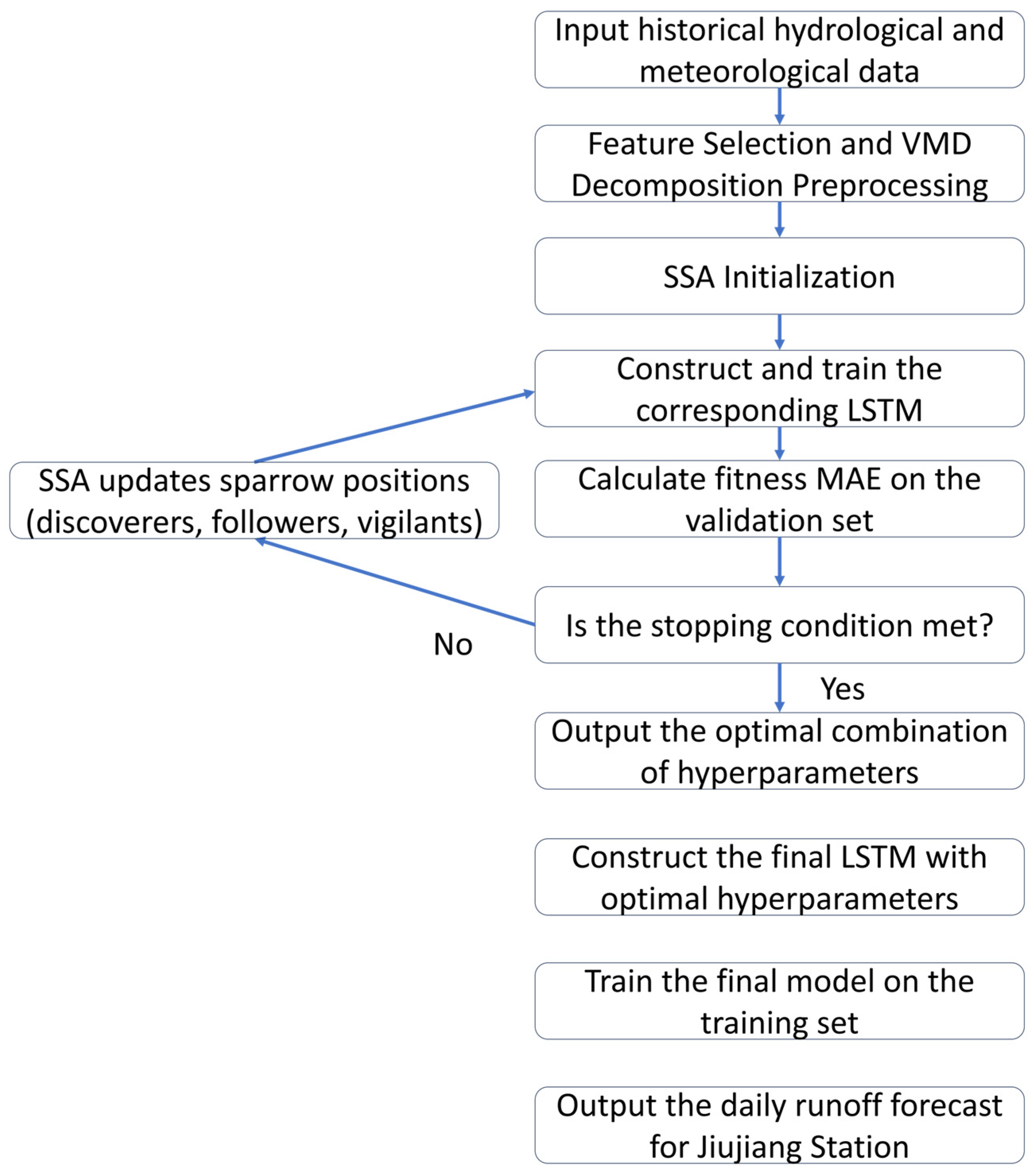

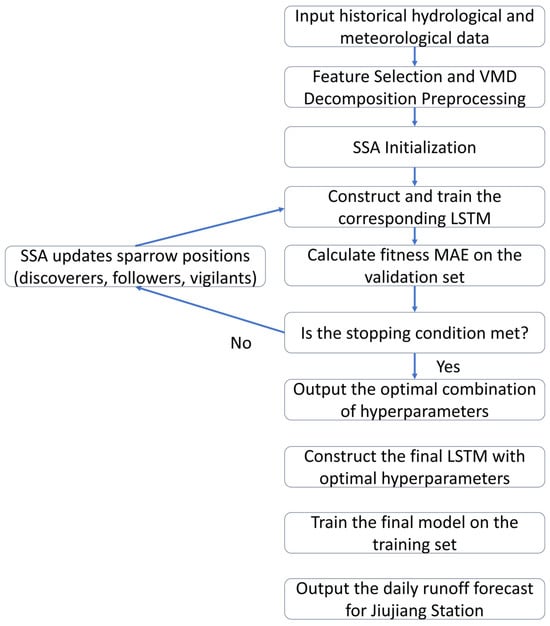

2.2.3. SSA-LSTM

The overall workflow of the coupled SSA-LSTM model is illustrated in Figure 3. The process begins with data preprocessing, followed by the iterative optimization of LSTM hyperparameters using the SSA, and concludes with the training and deployment of the optimized model for runoff forecasting.

Figure 3.

Workflow of the coupled SSA-LSTM model.

This study optimized the parameters of the LSTM based on the SSA, and further optimizes the model input through pre-feature selection and sequence decomposition, in order to achieve high-precision and high-efficiency runoff prediction. The pseudocode for coupling model execution process is shown in Algorithm A1 in Appendix A. The model construction process was as follows:

- Feature Selection and Sequence Decomposition Preprocessing. To optimize prediction performance and efficiency, preprocessing of the original dataset was first performed. The Pearson correlation coefficient was computed between each feature and the prediction target (runoff). Features exhibiting stronger correlations, such as discharges from key hydrological stations (e.g., Chenglingji (0.96), Yichang (0.86)), were retained to form an optimized input feature set. This process aims to eliminate redundant information, thereby improving model training efficiency and generalization capability. Subsequently, VMD was applied to the target prediction sequence [40]. VMD is an adaptive technique for decomposing non-stationary signals and is widely employed in hydrology to disentangle multi-scale temporal characteristics [41]. The number of Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs), denoted as K, is a critical parameter in VMD. K and the maximum iterations of the VMD algorithm were determined through the SSA automated parameter optimization process. The optimized K value converged to 5, leading to the decomposition of the runoff series into 5 IMFs. A parallel modeling framework was implemented. In this framework, each of the 5 IMFs served as an independent prediction target. A dedicated SSA-LSTM model was trained for each IMF. The final discharge forecast was obtained by summing the predictions from all five IMF-specific models. This method helps capture the physical laws at different time scales in the data, thereby improving the final prediction accuracy.

- Hyperparameter encoding and search space definition. The key structural hyperparameters of the LSTM to be optimized were encoded into the position vector of each sparrow individual in the SSA. The search space was defined as follows: the number of hidden layers [1, 3], the number of neurons in each hidden layer [2, 50], and the dropout rate [0.001, 0.5]. The initial learning rate was fixed at 0.001. In the SSA framework, each hyperparameter is directly mapped to a dimension of the sparrow‘s position vector , and the algorithm searches within the predefined bounds for each hyperparameter.

- Iterative optimization and fitness evaluation. The SSA population iterated and updated its position according to its rules. In each generation, the corresponding LSTM model was constructed and trained using the combination of hyperparameters represented by the position vector of each sparrow individual. In the SSA optimization framework, each sparrow individual’s position vector encoded four key structural hyperparameters: the number of hidden layers , the number of neurons in the first and second layers and , and the dropout rate . The fitness function was used to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of individuals. The fitness function for SSA was the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) calculated on the validation set.

- Final model training. When the SSA reached the maximum number of iterations or meets the convergence conditions, the optimal combination of hyperparameters obtained through search was substituted into the LSTM model architecture. After 20 generations of optimization with a population size of 10, the algorithm converged to an optimal configuration comprising a single hidden layer with 32 neurons and a dropout rate of 0.001. Other parameters were held constant. Using this optimal architecture, training was conducted on the training set and the validation set, and finally the SSA-LSTM prediction model with the best performance was obtained.

This integrated framework, which features VMD and LSTM hyperparameter optimization via SSA, was designed for the complex river–lake system of the middle Yangtze River. It effectively handles runoff processes under backwater and anthropogenic influences, as evidenced by its accuracy and robustness across all flow regimes.

2.2.4. Model Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the forecasting performance of the model, this study adopts the following three commonly used indicators [42]. The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) reflects the overall size of the prediction error and can effectively characterize the accuracy of the model. The MAE represents the average absolute level of the prediction error and characterizes the amplitude of the prediction error. The Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) reflects the consistency between predicted values and observed values. The combination of the three can conduct a comprehensive and reliable assessment of the model’s performance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Calibration and Validation

The dataset was partitioned into a training period (2009–2014), a validation period (2015), and a testing period (2016). The model inputs consisted of normalized daily discharge data of the hydrological stations such as Yichang in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and daily rainfall data of the entire middle reaches of the Yangtze River. The model output is the daily runoff of Jiujiang Station. Key configurable parameters included the number of neurons, iterations, and learning rate. The LSTM model was optimized using SSA, with the population size set to 10 and the evolution number set to 20. During the optimization process, the model’s fitness showed a gradually decreasing trend, indicating that the model performance is progressively improving. Both the RMSE and the loss function decreased and subsequently stabilized after multiple iterations, demonstrating effective convergence.

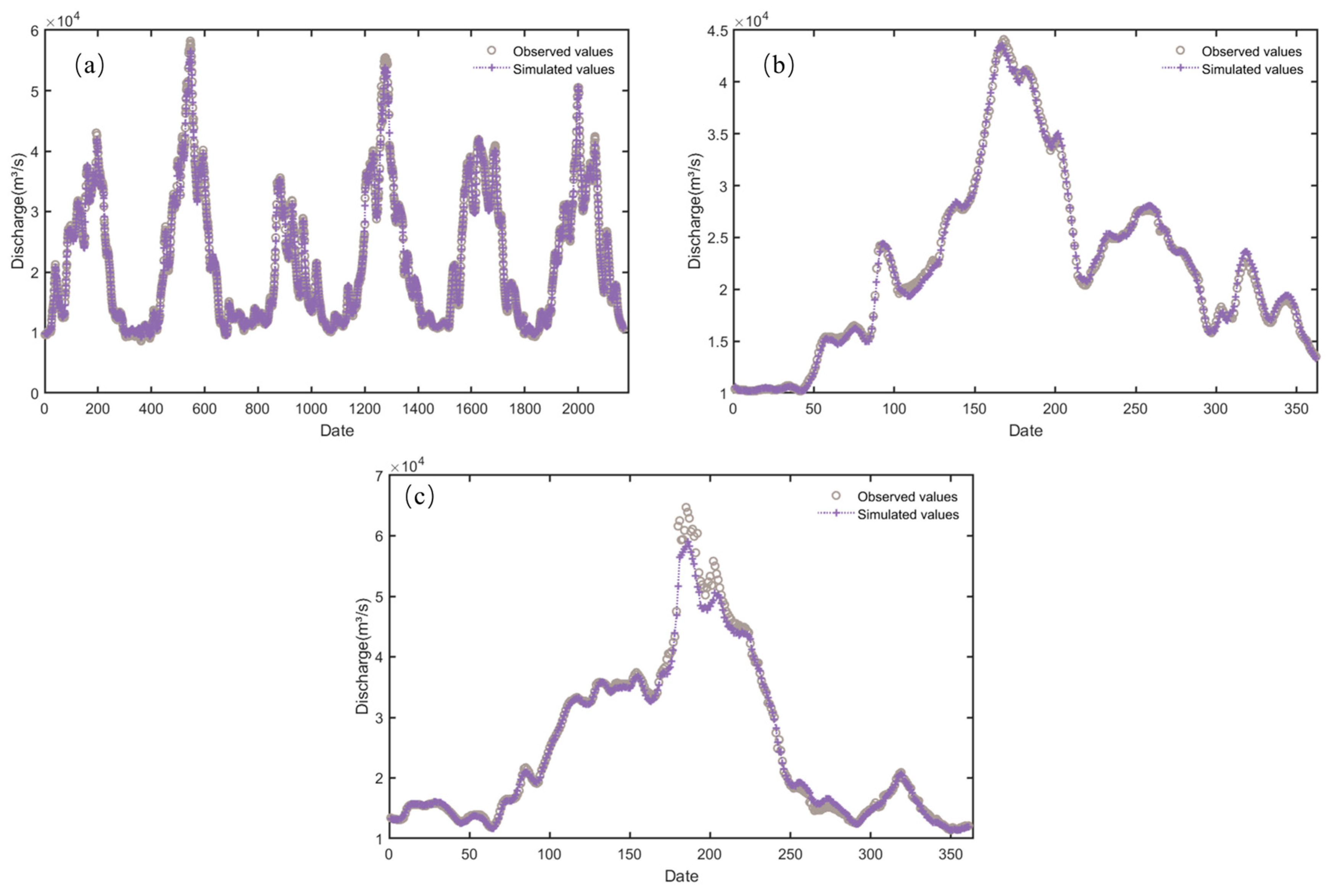

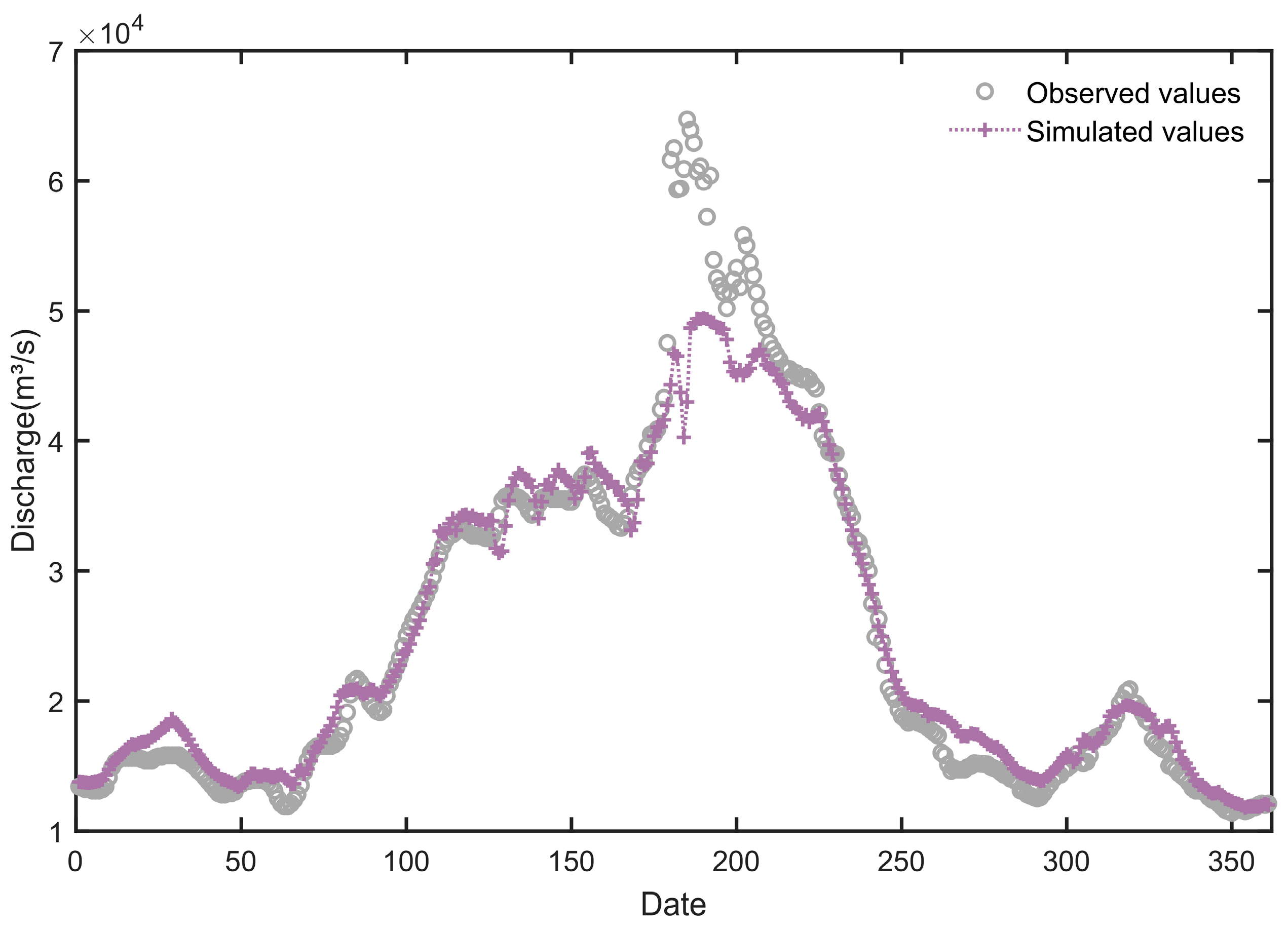

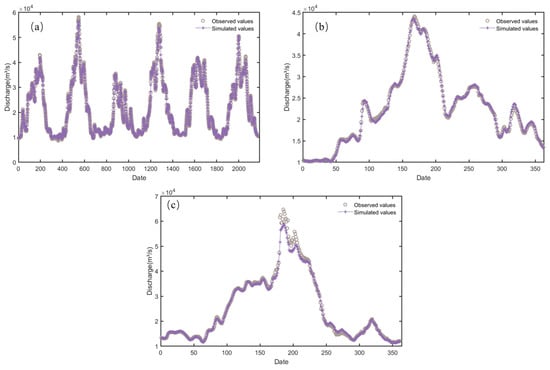

The predicted flow of Jiujiang Station showed a good fit with the observed flow (Figure 4). During the training period of the SSA-LSTM model, the RMSE at Jiujiang Station was 709.04 m3/s, the MAE was 494.74 m3/s, and the NSE reached 0.99. During the validation period of the SSA-LSTM model, the RMSE at Jiujiang Station was 600.13 m3/s, the MAE was 453.97 m3/s, and the NSE reached 0.99. During the testing period, the RMSE at Jiujiang Station was 1729.33 m3/s, the MAE was 926.72 m3/s, and the NSE reached 0.98.

Figure 4.

Flow prediction results of Jiujiang Station by SSA-LSTM. (a) Training period; (b) validation period; (c) testing period.

3.2. Comparison of Model Prediction Performance

The model performance was evaluated quantitatively for the testing period (2016). To provide a more comprehensive evaluation, we also introduced two additional metrics: Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) and Coefficient of Determination (R2). KGE integrates three aspects: correlation, bias, and variability, offering a more balanced assessment of model performance compared to using NSE alone [43]. R2 quantifies the proportion of variance in observed data explained by model predictions. The combination of these five metrics (NSE, RMSE, MAE, KGE, R2) enables a comprehensive and reliable evaluation of model performance.

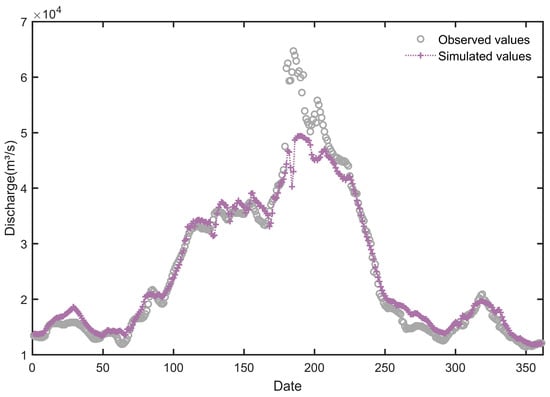

Figure 5 shows the comparison between predicted and measured discharge for the standard LSTM, and the quantitative evaluation indicators for both models are presented in Table 2. SSA-LSTM outperforms the standard LSTM in all three indicators. Specifically, the NSE of the LSTM is 0.94, while the NSE of the SSA-LSTM has increased to 0.98. It indicated that the goodness of fit between the predicted sequence and the observed sequence was improved. Meanwhile, RMSE and MAE of SSA-LSTM decreased by 49.3% (from 3409.26 m3/s to 1729.33 m3/s) and 51.3% (from 1902.78 m3/s to 926.72 m3/s, respectively, which directly reflects the effective reduction in the forecast error. The KGE increased from 0.84 for LSTM to 0.93 for SSA-LSTM, indicating a more balanced improvement across correlation, bias, and flow variability components. Similarly, the R2 value improved from 0.95 to 0.99, signifying that the SSA-LSTM model explains a greater proportion of the variance in the observed runoff data. These data proved that the systematic hyperparameter optimization through SSA enabled the LSTM model to more accurately capture the complex runoff formation mechanism in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River.

Figure 5.

Flow simulation results of Jiujiang Station by LSTM.

Table 2.

Performance Comparison During Testing Period.

The performance improvement of the SSA-LSTM model compared to the standard LSTM confirmed the importance of systematic hyperparameter optimization, indicated that SSA had an effective search strategy in this specific hydrological prediction problem and can successfully identify a set of parameters, thereby optimizing the prediction ability of LSTM.

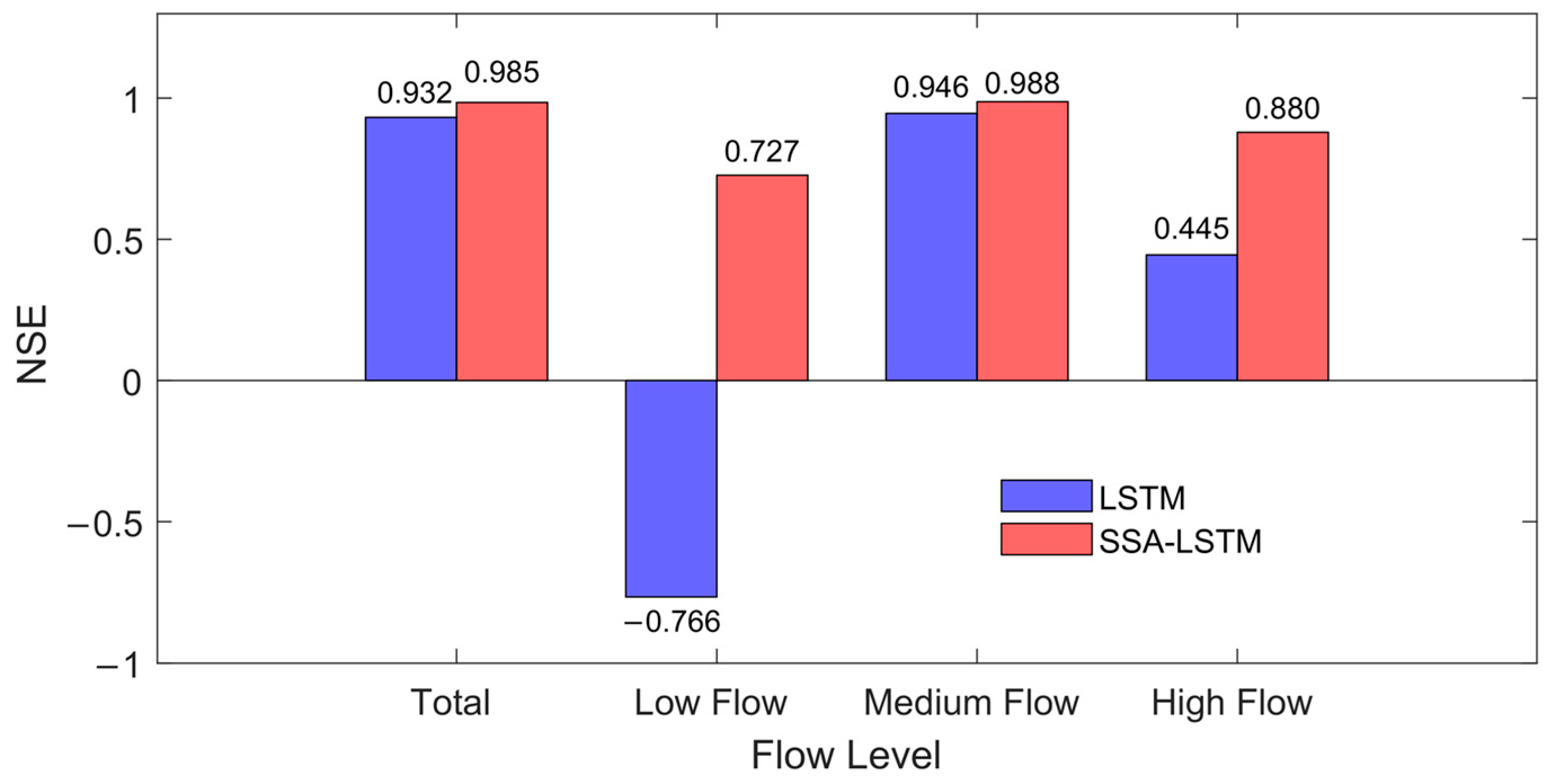

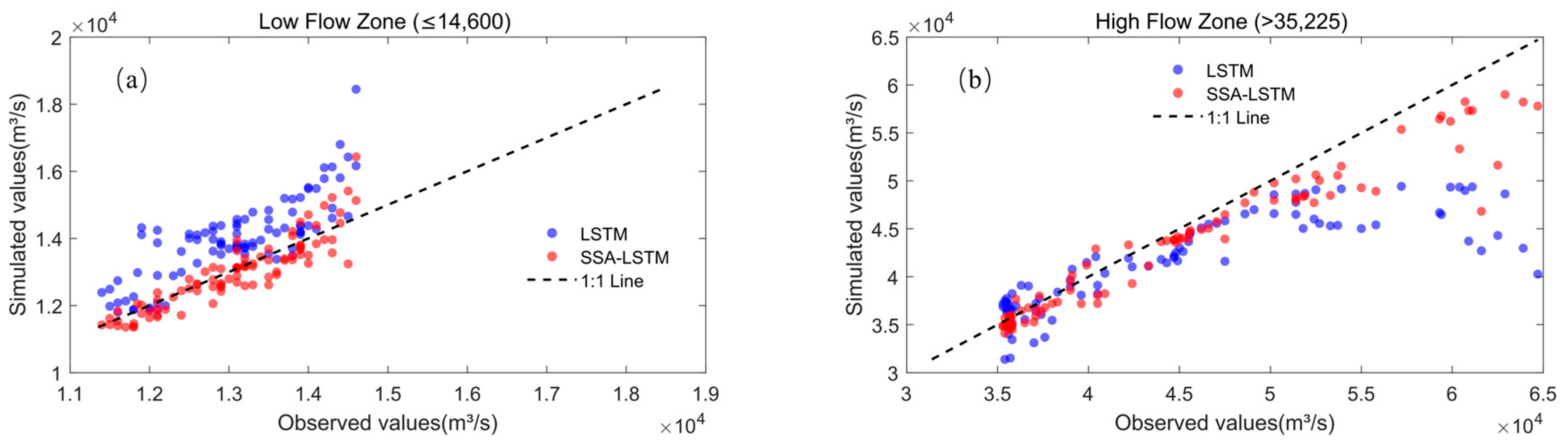

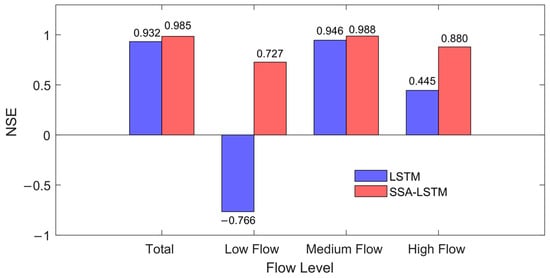

3.3. Predictive Performance Across Different Flow Regimes

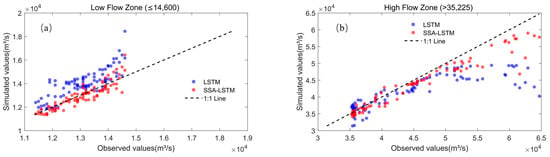

To evaluate the robustness of the model, the runoff during the test period was divided into three flow levels—high, medium, and low—using the 25th and 75th percentiles of the flow duration curve as thresholds. Figure 6 shows the Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) values of the SSA–LSTM model at each flow level, while Figure 7 further compares the observed values against the predicted values from both the LSTM and SSA–LSTM models for low-flow (≤14,600 m3/s) and high-flow (>35,225 m3/s) intervals using scatter plots. The results indicate that the SSA–LSTM model outperforms the standard LSTM model across all flow levels. Specifically:

Figure 6.

Model performance (NSE) across different flow regimes during the testing period (2016).

Figure 7.

Comparison of prediction performance between LSTM and SSA-LSTM models at different flow levels. (a) Comparison of predictive performance at low-flow zone (≤14,600 m3/s); (b) comparison of predictive performance at high-flow zone (>35,225 m3/s).

At the high-flow level, the SSA–LSTM shows a significant improvement in predicting peak flows, with the NSE increasing from 0.45 to 0.88. This suggested that the SSA-optimized LSTM can better capture the more complex nonlinear relationships inherent in high-flow processes (such as rainfall–runoff responses and flood wave propagation), thereby predicting peak discharge and hydrograph shape more accurately.

At the low-flow level, the SSA–LSTM also demonstrates higher accuracy and stability, with the NSE improving from −0.77 to 0.72. This indicated that the optimized model had a better understanding and prediction capability of baseflow generation mechanisms, maintaining reliable predictive performance under low-flow conditions.

At the medium-flow level, the SSA–LSTM maintains a high goodness-of-fit, illustrated the model’s consistency and adaptability under varying hydrological conditions.

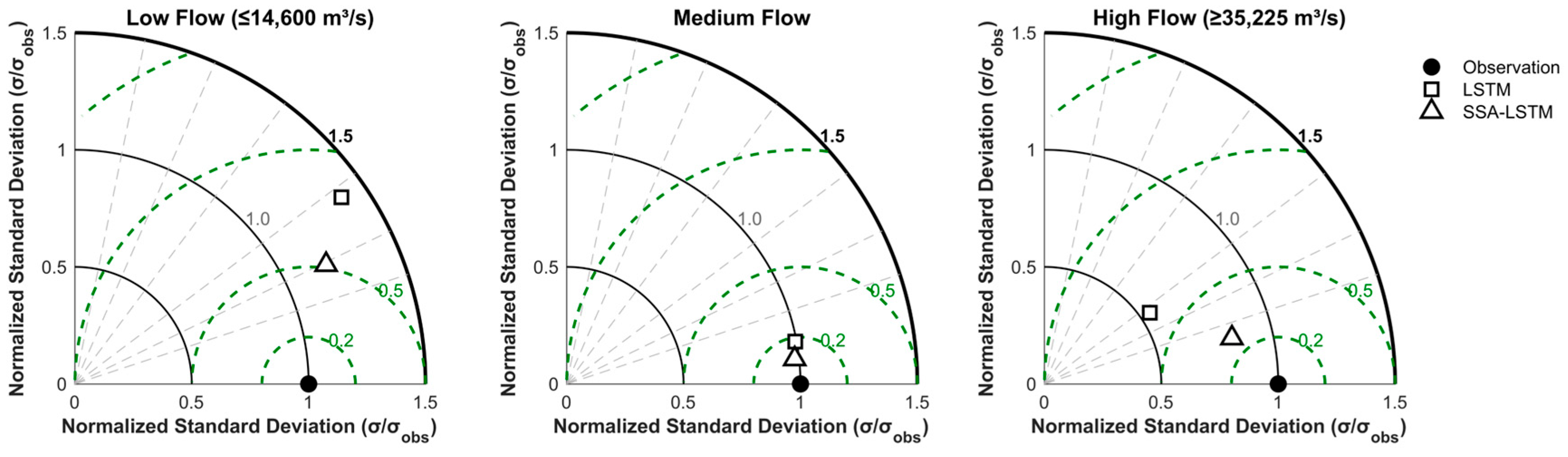

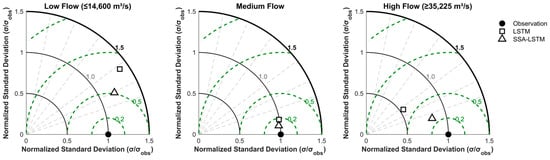

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s robustness and error characteristics under different hydrological conditions, Taylor diagrams and error distribution plots are further employed for assessment.

The Taylor diagram (Figure 8) showed the comparison results of standard deviation (σ), correlation coefficient (R), and centered root mean square error (CRMSE) between the LSTM model and the SSA-LSTM model against observations under each flow level regime scenario. The results indicated that the SSA-LSTM model outperforms the standard LSTM model in all regimes.

Figure 8.

Taylor diagrams comparing the performance of LSTM and SSA-LSTM models at different flow levels during the test period.

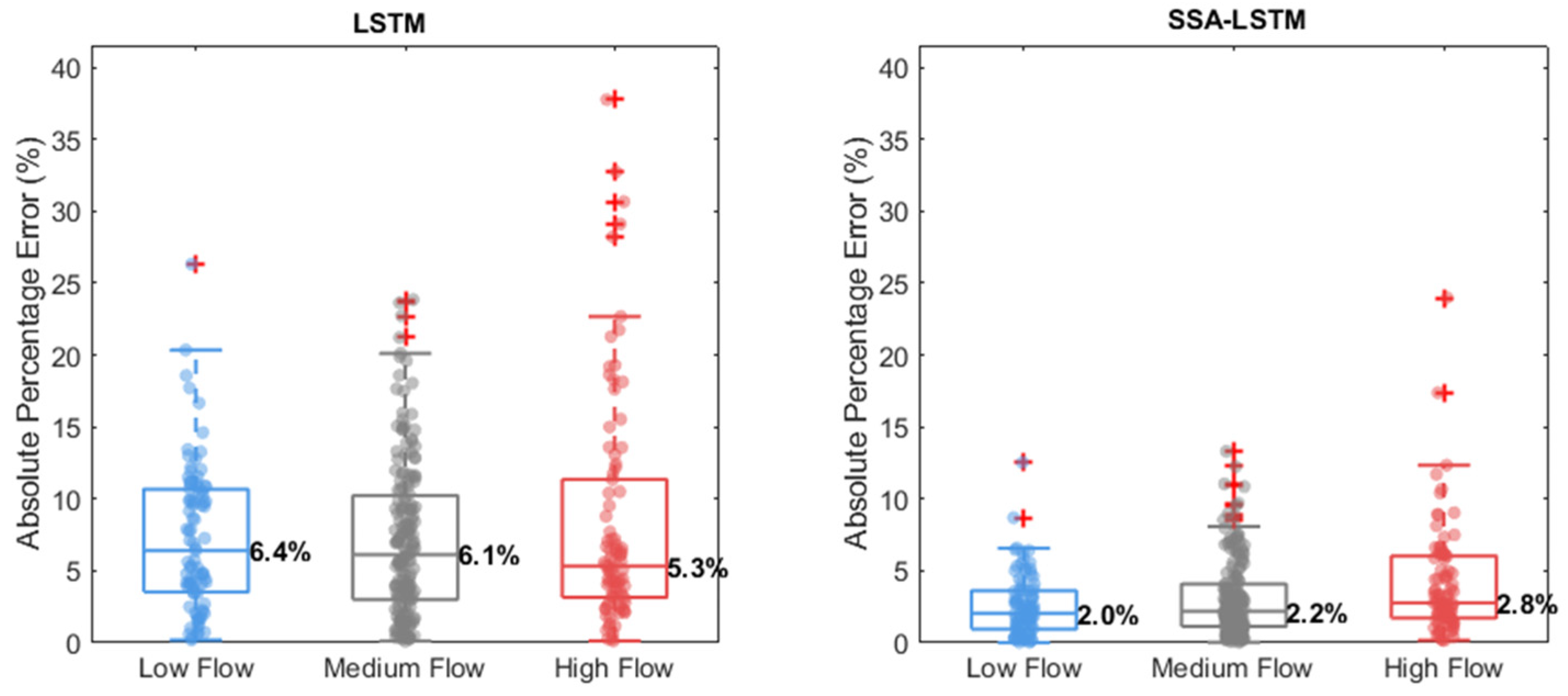

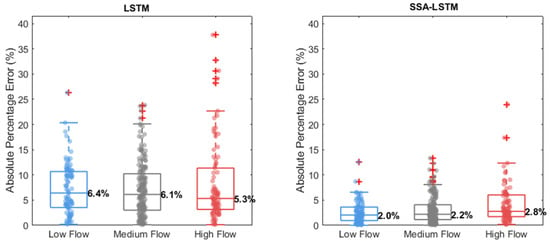

The distribution of prediction uncertainties and margins of error was analyzed via Absolute Percentage Error (APE) boxplots with overlaid data points (Figure 9). This revealed that the SSA-LSTM model exhibits not only consistently lower median APE but also a tighter error distribution (smaller interquartile range and fewer outliers) than the LSTM model for low, medium, and high flows.

Figure 9.

Distribution of APE for the LSTM and SSA-LSTM models at different flow levels during the test period.

The SSA–LSTM model retains high accuracy across all flow levels. Its excellent performance under high-flow scenarios is crucial for flood warning, while its reliable performance during low-flow periods provides a solid basis for water resources management and ecological protection in the basin [22,44]. These results verified the effectiveness of the SSA optimization strategy in enhancing the LSTM model’s adaptability to different flow levels and demonstrated the practical utility of SSA–LSTM in complex hydrological systems.

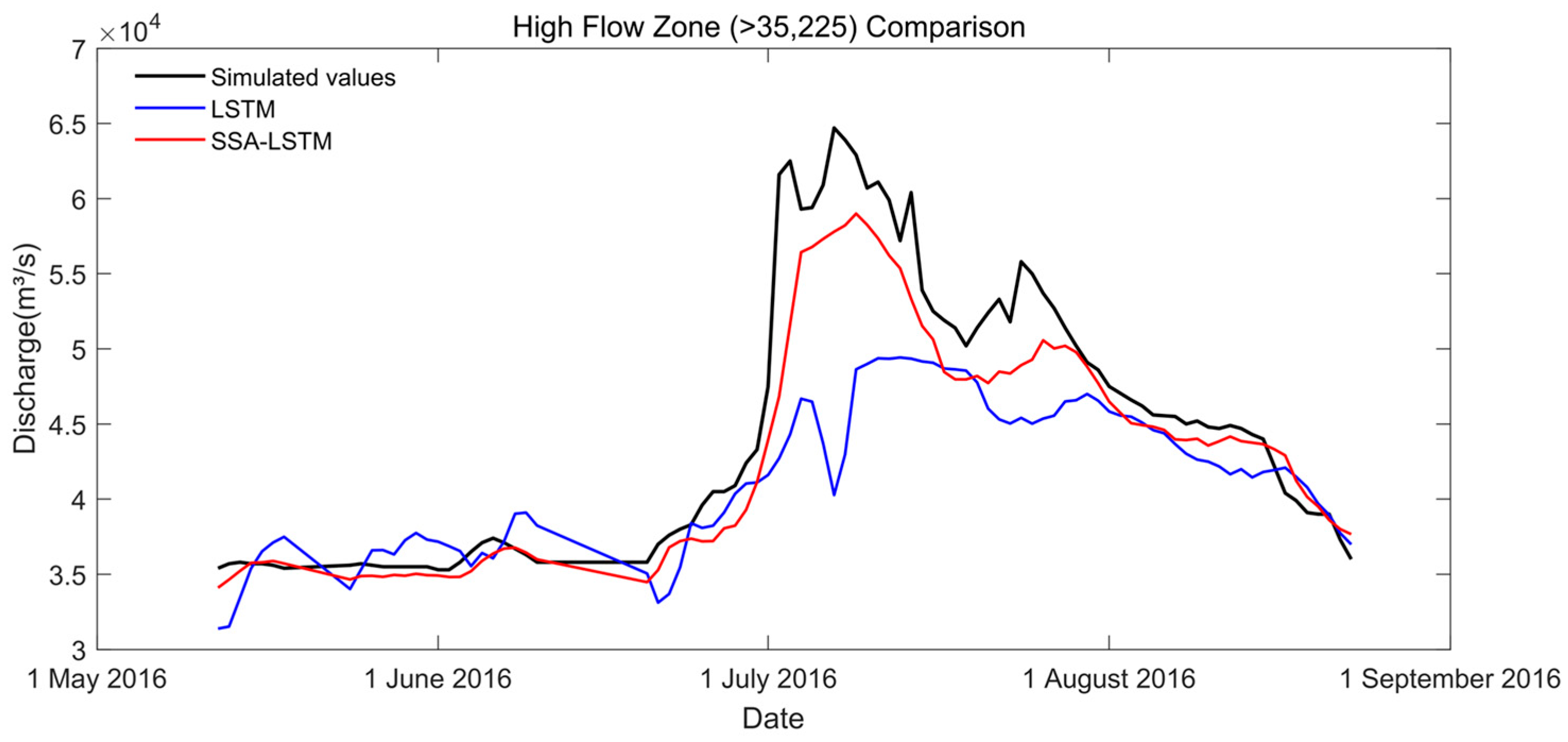

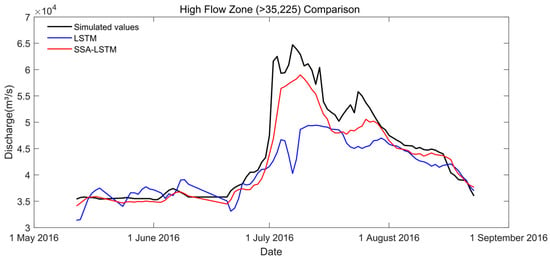

A typical high-flow process period within the test period was selected for detailed analysis (Figure 10). The comparison between the predicted values and the observed values showed that although the standard LSTM could reflect the basic trend of runoff changes. Its response is slightly slower during the flood peak rising stage, and its fitting degree to the peak is poor, with an underestimation of high flow peaks. In addition, in the receding section after the peak, there is also a slight delay in its prediction. In contrast, the SSA-LSTM model better reproduces high-flow processes, including more accurate peak arrival times, peak flow rates, and the shape of the drainage curve. This indicated that the optimized LSTM could more accurately remember and update the previous flow conditions of the basin in its internal state, and its gating mechanism can more effectively determine when to forget old information and when to inject new information, thereby achieving a more precise prediction of the rapidly changing hydrological dynamics.

Figure 10.

Comparison of predicted and observed hydrographs for a representative flood event within the testing period.

SSA-LSTM performed more stably and effectively throughout the entire prediction process, highlighting its superior generalization ability. The significant performance gap of the standard LSTM between medium flow and high and low extreme flow indicated its limited ability to characterize the hydrological features of complex water systems. The SSA optimization process effectively addressed this limitation and identified a robust and accurate model configuration suitable for the complex water system in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. This is the result of SSA identifying the hyperparameter configuration, which achieves an optimal balance between model complexity and regularization, thereby reducing overfitting for specific traffic scenarios and ensuring reliable predictions in various scenarios.

Comparative studies on runoff prediction in the TGD area have shown that, under an identical framework, the VMD-SSA-LSTM model achieved the highest prediction accuracy. Specifically, the test-set NSE values for the VMD-SSA-LSTM, VMD-WOA-LSTM, and VMD-GOA-LSTM models were reported as 0.95, 0.93, and 0.9, respectively [45]. This demonstrates that the SSA-optimized model outperformed those using WOA and GOA in this scenario, justifying its selection for hyperparameter optimization in our study due to its higher convergence accuracy and robustness when dealing with the high-dimensional, non-convex search space characteristic of LSTM models. While a comprehensive analysis with other commonly used hyperparameter optimization techniques remains to be thoroughly explored in future work within the specific context of this study, the aforementioned analysis helps to illustrate the competitive advantages of the SSA-LSTM method.

To further contextualize the predictive performance of the SSA-LSTM model, its results are compared with the prediction results of physical-based models in the same region. For instance, a large-scale coupled hydrological-hydrodynamic model applied to the Yangtze River basin reported NSE values of approximately 0.60 to 0.70 during the validation period at Hukou station, a site influenced by complex river–lake interactions [46]. Another study utilizing a 1D/2D hydrodynamic model (MIKE) for the middle Yangtze River achieved an NSE of 0.97 for flow prediction at Jiujiang station [47]. In comparison, the SSA-LSTM model developed in this study attained an NSE of 0.98 at Jiujiang station during the testing period, demonstrating its high precision as a data-driven tool for daily forecasting. It is important to note that while the SSA-LSTM excels in overall process fitting and peak flow prediction (as shown in Figure 8), accurately estimating the total volume of extreme flood events remains a challenge, as highlighted in Figure 7. This aspect may be better constrained by physical models that explicitly solve water balance equations. Therefore, future work could explore hybrid frameworks that integrate the predictive strengths of data-driven models with the physical consistency of process-based models for comprehensive flood modeling.

4. Conclusions

This study addressed the daily runoff forecasting at the Jiujiang Hydrological Station in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, which is influenced by complex river–lake interactions, by developing a coupled model that integrates the SSA with a LSTM (SSA-LSTM). The model systematically optimized the hyperparameters of LSTM to improve prediction accuracy. The main conclusions are as follows:

The SSA-LSTM model demonstrated better overall prediction performance than the standard LSTM model. During the testing period, the NSE increased from 0.94 to 0.98, while the RMSE and MAE decreased by 49.3% and 51.3%, respectively. This indicated that SSA could effectively identify an optimal hyperparameter configuration, substantially enhancing the runoff prediction capability of LSTM in complex hydrological systems.

The model exhibited good adaptability and robustness under different flow levels. Under high-flow conditions, the model not only improved the NSE from 0.45 to 0.88 but also corrected a substantial underestimation of flow variability and notably reduced prediction uncertainty, indicating that the model captured flood peaks and hydrograph shapes more accurately, which is critical for flood warning. Under low-flow conditions, the NSE rose from −0.77 to 0.72, demonstrating that the model predicted baseflow mechanisms more reliably and provides a sound basis for water resources management and ecological protection during dry periods.

The SSA-LSTM framework offered an efficient and accurate data-driven solution for daily runoff forecasting in complex basins such as the middle Yangtze River. By automating hyperparameter tuning, it enhances the practicality and reliability of deep-learning models in hydrology, providing a valuable reference for runoff prediction and forecasting in similar complex hydrological systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z., C.Z. and Y.W.; methodology, Q.Z., Y.D. and H.Z.; software, Q.Z., Y.D. and H.Z.; validation, Q.Z., Y.D. and Y.W.; formal analysis, Q.Z., Y.D. and Y.W.; investigation, Q.Z., C.Z. and Y.W.; resources, C.Z. and Y.W.; data curation, Q.Z. and Y.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Z. and Y.D.; writing—review and editing, Q.Z., Y.D., C.Z., Y.W., and H.W.; visualization, Y.D.; supervision, H.W.; project administration, Y.D.; funding acquisition, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number U22A20555, General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42371034, and The Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province, grant number No. 2023CXGC010905. The APC was funded by the author’s institution, Space Engineering University.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are being used for further analyses by the research team. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author, Yaoyao Dong, at yao0123@hgd.edu.cn.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Pseudocode for coupling model execution process.

| Algorithm A1: SSA-VMD-LSTM Prediction Model |

| Input: Historical hydrological and meteorological data Output: Predicted future runoff values # Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection 1.1 Select features with highest Pearson correlation coefficients 1.2 Split data into training, validation, and testing sets # Step 2: VMD Parameter Optimization and Decomposition 2.1 Optimize VMD parameters using SSA 2.2 Decompose runoff series into K IMF components # Step 3: For each IMF component, optimize LSTM hyperparameters For each IMF component k: 3.1 Prepare input: [selected features, IMF_k] 3.2 Use SSA to optimize LSTM hyperparameters (layers, neurons, dropout) - Fitness function: MAE on validation set 3.3 Obtain optimal LSTM architecture for IMF_k # Step 4: Model Training and Prediction For each IMF component k: 4.1 Train LSTM with optimized architecture for IMF_k 4.2 Predict IMF_k values on test set # Step 5: Result Reconstruction and Evaluation 5.1 Final prediction = Σ (IMF_1_prediction + … + IMF_K_prediction) 5.2 Evaluate using RMSE, MAE, NSE metrics on test set Return predicted runoff values |

References

- Li, X.; Ye, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D. Hydrological drought in two largest river-connecting lakes in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, China. Hydrol. Res. 2023, 54, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, C.; Fang, H.; Zhang, L.; Su, X.; Fu, X.; Huang, H.Q.; Parker, G.; Hassan, M.A.; Meghani, N.A.; Anders, A.M.; et al. Poyang and Dongting Lakes, Yangtze River: Tributary lakes blocked by main-stem aggradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2101384119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, S.; Xiang, X.; Li, C.; Li, N. Impact of Three Gorges Reservoir Operation on Water Level at Jiujiang Station and Poyang Lake in the Yangtze River. Hydrology 2025, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, P.; Jiang, L.; Liu, K.; Chen, T.; Fan, C.; Zeng, F.; Song, C. Unveiling the Floodplain River-Lake Hydrological Interactions by SWOT Observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2025GL118459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhong, P.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Xu, C.; Ben, M.; Li, M. Spatiotemporal attribution of runoff changes in the upper Yangtze River Basin using the SWAT+ model. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 61, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C. A trans-disciplinary review of deep learning research for water resources scientists. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 8558–8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Granata, F.; Di Nunno, F.; de Marinis, G. Stacked machine learning algorithms and bidirectional long short-term memory networks for multi-step ahead streamflow forecasting: A comparative study. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nunno, F.; Zhu, S.; Ptak, M.; Sojka, M.; Granata, F. A stacked machine learning model for multi-step ahead prediction of lake surface water temperature. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 890, 164323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, C. Quantifying the Impact of Compounding Influencing Factors to the Water Level Decline of China’s Largest Freshwater Lake. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2020, 146, 5020006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, F.; Di Nunno, F. Neuroforecasting of daily streamflows in the UK for short- and medium-term horizons: A novel insight. J. Hydrol. 2023, 624, 129888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deulkar, A.M.; Dixit, P.R.; Londhe, S.N.; Jain, R.K. Comparative Assessment of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Long Short Term Memory Network (LSTM) and Hydrologic Engineering Centre-Hydrologic Modelling System (HEC-HMS) for Runoff Modelling. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 39, 2049–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Kuglitsch, M.M.; Pelivan, I.; Albano, R. Review and Intercomparison of Machine Learning Applications for Short-term Flood Forecasting. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 39, 1971–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Xia, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zeng, S.; She, D.; Wang, G. Coupling Machine Learning into Hydrodynamic Models to Improve River Modeling with Complex Boundary Conditions. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2022WR032183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; He, Z. River and Lake Evolution of the Middle and Lower Yangtze River Basin and Its Impacts. J. Chang. River Sci. Res. Inst. 2025, 42, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Yan, J.; Demir, I. A Rainfall-Runoff Model With LSTM-Based Sequence-to-Sequence Learning. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR025326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, K. Prediction of runoff in the upper Yangtze River based on CEEMDAN-NAR model. Water Supply 2021, 21, 3307–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Hrnjica, B.; Ptak, M.; Choiński, A.; Sivakumar, B. Forecasting of water level in multiple temperate lakes using machine learning models. J. Hydrol. 2020, 585, 124819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Jiang, M.; Xu, L.; Zhu, H.; Cheng, J.; Jiang, J. Comparison of Long Short Term Memory Networks and the Hydrological Model in Runoff Simulation. Water 2020, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhan, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lin, Z. A coupled model applied to complex river-lake systems. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2024, 69, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Mohammadian, A.; Khelifa, A. Modeling spatial distribution of flow depth in fluvial systems using a hybrid two-dimensional hydraulic-multigene genetic programming approach. J. Hydrol. 2021, 600, 126517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzert, F.; Klotz, D.; Shalev, G.; Klambauer, G.; Hochreiter, S.; Nearing, G. Towards learning universal, regional, and local hydrological behaviors via machine learning applied to large-sample datasets. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 5089–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Shen, Y. Comparative Evaluation of Runoff Forecasting Methods in Xiangjiang River Basin at Multiple Temporal Scales. J. Chang. River Sci. Res. Inst. 2025, 42, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z. A Grid-Based Long Short-Term Memory Framework for Runoff Projection and Uncertainty in the Yellow River Source Area Under CMIP6 Climate Change. Water 2025, 17, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, T.; Lu, C. VMDI-LSTM-ED: A novel enhanced decomposition ensemble model incorporating data integration for accurate non-stationary daily streamflow forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2025, 653, 132769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, M.; Yang, J. Developing a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) based model for predicting water table depth in agricultural areas. J. Hydrol. 2018, 561, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Yan, J.; Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Tian, W.; Tao, T.; Xin, K. A hybrid Wavelet-CNN-LSTM deep learning model for short-term urban water demand forecasting. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2022, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, V.; Ramesh, R.; Sreeja, P.; Jarin, T.; Sujith Kumar, P.S.; Ansar, S.; Ashraf, G.A.; Pandey, S.; Said, Z. Hybridization of long short-term memory with Sparrow Search Optimization model for water quality index prediction. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, F.; Kotthoff, L.; Vanschoren, J. Automated Machine Learning: Methods, Systems, Challenges; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Shen, B. A novel swarm intelligence optimization approach: Sparrow search algorithm. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2020, 8, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Chen, M.; Zhou, Y.; Ran, L.; Shi, R.; Zou, J. Mid-Long Term Hydrological Forecasting Based on Multiple Hybrid Models. J. Chang. River Sci. Res. Inst. 2025, 42, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Dai, Z.; Du, J.; Chen, J. Linkage between Three Gorges Dam impacts and the dramatic recessions in China’s largest freshwater lake, Poyang Lake. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Xia, J.; Zeng, S.; Wang, Y.; She, D. Effect of Three Gorges Dam on Poyang Lake water level at daily scale based on machine learning. J. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 1598–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Jiang, L.; Du, E.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, L. A New Understanding of the Poyang Lake-Yangtze River Interaction: A Backwater Effect on the Yangtze River Perspective. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2025GL114807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzegar, R.; Aalami, M.T.; Adamowski, J. Coupling a hybrid CNN-LSTM deep learning model with a Boundary Corrected Maximal Overlap Discrete Wavelet Transform for multiscale Lake water level forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzert, F.; Klotz, D.; Brenner, C.; Schulz, K.; Herrnegger, M. Rainfall–runoff modelling using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 6005–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Xu, T.; Ye, H.; Wang, L.; Liang, L. Reconstruction of Daily Runoff Series in Data-Scarce Areas Based on Physically Enhanced Seq-to-Seq-Attention-LSTM Model. Water 2025, 17, 3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomiretskiy, K.; Zosso, D. Variational Mode Decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, M.; Lai, X.J.; Guo, Y.; Lu, Z.; Chen, Y.P.; Pan, S.Q.; Pan, H.D.; Chu, A. Unravelling the spatiotemporal variation in the water levels of Poyang Lake with the variational mode decomposition model. Hydrol. Process 2024, 38, e15239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.V.; Kling, H.; Yilmaz, K.K.; Martinez, G.F. Decomposition of the mean squared error and NSE performance criteria: Implications for improving hydrological modelling. J. Hydrol. 2009, 377, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedkov, S.; Campagne, S.; Borisova, B.; Krpec, P.; Prodanova, H.; Kokkoris, I.P.; Hristova, D.; Le Clec’H, S.; Santos-Martin, F.; Burkhard, B.; et al. Modeling water regulation ecosystem services: A review in the context of ecosystem accounting. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 56, 101458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Chen, M.E.; Zhou, Y.L.; Zou, J.H.; Ran, L.B.; Shi, R.B. Research on optimal selection of runoff prediction models based on coupled machine learning methods. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 32008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zeng, S.; Xia, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, R.; Chen, M. Effects of the Three Gorges Dam on the downstream streamflow based on a large-scale hydrological and hydrodynamics coupled model. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 40, 101039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, J.P.; Deng, P.X.; Zhang, D.D.; Liu, X. Influence of Three Gorges Reservoir operation on hydrological regime of Poyang Lake. Yangtze River 2020, 51, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.