Abstract

Watershed planning in the Andean–Amazonian headwaters requires an understanding of how land use/land cover (LULC) affects hydrological regimes. This study integrates MOLUSCE-based LULC simulations (2020–2050) with the SWAT model to quantify the effects of deforestation, agricultural expansion, and pine forestation in the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins (northeastern Peru). Model performance was robust despite limited hydro-meteorological data (KGE = 0.74–0.79; PBIAS = 7.2–4.2%). By 2050, projections indicate faster runoff generation, with decreases in percolation (12–13%) and lateral flow (1.8–3.2%), surface runoff increases (≈13%; up to +36% under agricultural expansion), and groundwater contribution declines (up to 28%). These shifts intensify low-flow deficits (−39 to −45%) and slightly increase wet-season peaks (>5%). Pine forestation shows modest and mixed hydrological effects. Identifying sensitive sub-basins provides key information for watershed management. In general, combining LULC scenarios with hydrological modeling allows us to have a technical–scientific tool to plan the territory with an emphasis on water security, prioritizing the conservation of native forests at the headwaters of the basin and ensuring the hydrological resilience of the high Andean regions.

1. Introduction

At the global level, the growing pressure on water resources is the combined result of activities such as population expansion, increasing degradation of ecosystems and abrupt changes in land use patterns, which have a greater impact on regions already prone to water stress [1]. A significant part of the world’s water demand, which exceeds 50% of total consumption, depends on river systems, whose hydrological behavior is conditioned by long-term variability in the dynamic climatic regimes of precipitation, temperature and evapotranspiration [2,3]. This evidence on water pressure indicates the need to understand how human-induced transformations of the territory alter hydrological regimes, especially in mountainous Andean environments where ecological systems are increasingly sensitive to small changes [4,5]. Accordingly, surface runoff plays an important role in understanding the hydrological response of watersheds, since it is directly linked to ecological processes and the dynamics of land use changes in the territory.

Advanced studies in runoff and water balance analysis in hydrographic units have been promoted thanks to the application of hydrological models, which are based on physics, geographic information systems (GIS) and remote sensing approaches. These tools allow for the description of ecosystems and facilitate the interpretation of naturally complex hydrological processes that operate at multiple spatial scales [6,7]. Among the different models that interpret and simplify hydrological processes, the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) has proven to be able to reproduce the hydrological cycle of a watershed in response to land-use dynamics, which together with climatic variables, topographic, and soil property data allows us to simplify and represent the hydrological cycle of a watershed [8,9]. Its power and methodological flexibility make it a suitable alternative for regions with limited hydrometeorological information, a frequent condition in high Andean and mountainous areas with difficult access [10,11]. At the intercontinental level, the SWAT model has been applied to assess the effects of human activities on flow patterns, erosion, sediment transport, water quality, and availability [4,7,12]. In addition, LULC transitions are incorporated and represented spatially using tools such as the Land Use Change Assessment Modules (MOLUSCE), which integrates machine learning algorithms and spatial predictors to generate LULC maps in GIS environments [13,14].

In LULC change scenarios, SWAT has been widely used to analyze the hydrological implications of deforestation, agricultural expansion, livestock systems, and urbanization [15,16,17]. In tropical biomes, these transformations are particularly intense, and the tropical Andes are an emblematic case, where several studies have reported the sensitivity of flow regimes to changes in LULC, particularly in basins of Colombia and Ecuador [18,19]. In Peru, the SWAT model has been utilized in both forested and arid regions, showing a strong ability to replicate components of the hydrological cycle even with restricted data access [19,20,21]. However, its application in the Andean–Amazonian region remains limited, and there is still scarce quantitative evidence on how projected LULC trajectories might affect hydrological resilience in this mountainous corridor [22].

Within this regional context, the upper Utcubamba River basins is located in northeastern Peru and is preliminary composed of the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins. These hydrographic units are of strategic importance due to their ecosystem diversity, the presence of protected areas and their contribution to regional water security through the supply of water for agriculture, human consumption, ecotourism and natural infrastructure [22]. Given the coexistence of montane forests, grasslands, agricultural lands, and expanding urban areas, these basins offer an ideal setting to examine how LULC transitions can modify hydrological processes.

However, the limited availability of hydrometeorological stations continues restrict understanding of hydrological dynamics in the region, particularly in the context of increasing deforestation and unplanned afforestation. Between 2001 and 2025, the department of Amazonas lost approximately 121,392 ha of forest cover, mostly in small patches (<5 ha), intensifying landscape fragmentation and altering runoff, evapotranspiration, and groundwater recharge [22,23]. This underscores a critical need for knowledge regarding the effects of LULC dynamics and to understand how it impacts hydrological behavior in steep and fragmented Andean–Amazonian basins.

Indeed, this study focuses on filling this knowledge gap through (i) analysis of LULC changes in both basins from 1990 to 2025 in order to identify the areas most susceptible to landscape fragmentation and their potential influence on hydrological alteration; (ii) to evaluate the performance of the SWAT model in two Andean–Amazonian basins with scarce hydroclimatic data, and (iii) to simulate river flow responses under current and future LULC scenarios, aligned with regional afforestation and deforestation activities for the extension of agricultural frontiers. This integration allows for the identification of potential sites for restoration, preservation, and sustainable management of water resources.

The findings of this study form a technical and scientific basis to support territorial planning of data-constrained high Andean and mountain ecosystems, further contributing to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 6, 13 and 15 [24,25,26]. In addition, evaluating the efficiency of the SWAT model in these watersheds provides a valuable methodological basis for future research in regions increasingly affected by landscape fragmentation, urban sprawl, and climate change. This problem highlights the vulnerability of the territory to the combined effects of anthropogenic and natural actions and that this type of study, together with sustainable development strategies and policies, allows us to mitigate serious impacts on water security and resource management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

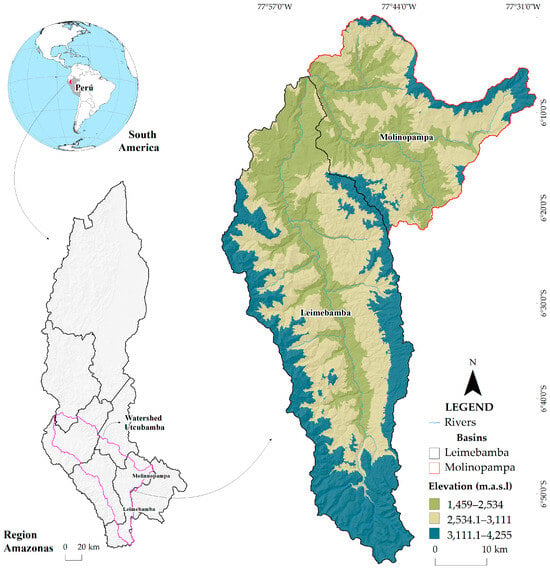

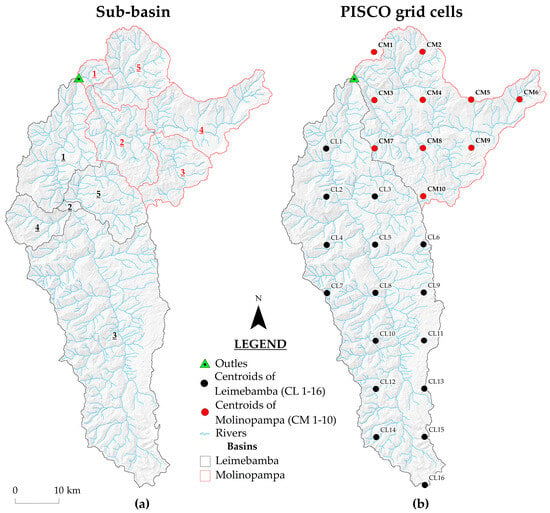

The research focuses on two high Andean basins within the territory of the department of Amazonas, in northeastern Peru: Leimebamba Basin (1830 km2) and Molinopampa (922 km2), with altitude ranges between 1700 and 4200 m.a.s.l. (Figure 1). Both basins are characterized by complex geomorphology, with slopes ranging from moderate to steep, reflecting relief conditions typical of the Andean mountainous ecosystem [27,28]. In the study area there are peasant and mestizo communities whose means of subsistence have historically been agriculture, livestock production, and activities related to Ecotourism [29,30]. The total population within both basins is estimated at about 70,000 inhabitants, mainly concentrated in the districts of Leimebamba, Chachapoyas and Molinopampa [31,32]. Agricultural practices are dominated by the cultivation of corn and potatoes, along with the production of fodder that supports an extensive livestock system [33,34,35]. Intensive land use and agricultural expansion have generated modifications in vegetation cover and landscape fragmentation processes, affecting rural ecosystems and conservation areas [36,37]. These dynamics make Leimebamba and Molinopampa strategic territories to evaluate how changes in the LULC influence water regulation and the guarantee of water supply for the main cities of the region.

Figure 1.

Spatial location of the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins, situated within the Amazonas Department in northwestern Peru.

The climate in the Leimebamba basin has temperatures 6–24 °C, with a mean annual rainfall of roughly 1200 mm. For its part, the climate in the Molinopampa basin is characterized by its humidity throughout the year, with temperatures ranging from 7 to 26 °C and with average rainfall close to 850 mm per year, according to records derived from the PISCO-SENAMHI dataset of virtual stations [38].

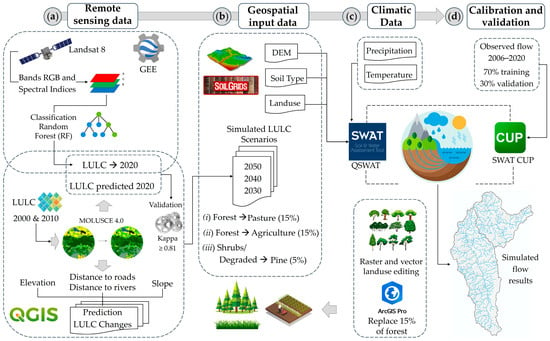

2.2. Methodological Flow

The methodology integrated remote sensing, land-use change modeling, and hydrological simulation (Figure 2). Landsat 8 imagery was classified in GEE with Random Forest and future LULC scenarios were generated in MOLUSCE using topographic and accessibility variables. The LULC products were integrated with the digital elevation model, soil characteristics, and land-use scenario configurations (agricultural expansion, pasture development, and afforestation) to drive the SWAT simulations. Model adjustment was conducted through calibration and validation procedures implemented in SWAT-CUP, using observed streamflow records, which enabled the assessment of simulated discharge under both baseline and future scenario conditions.

Figure 2.

Integrated methodological framework: (a) remote sensing data processing, (b) geospatial input data, (c) climatic data, and (d) hydrological calibration and validation.

2.3. Land Use/Land Cover Classification

Land use/land cover (LULC) mapping of the Leimebamba and Molinopampa watersheds was carried out using satellite remote sensing data processed on the free Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform [39]. The workflow relied on multispectral imagery acquired from the Landsat 8 (OLI/TIRS) Collection 2, Level 2 dataset, covering the period from 2020 to 2024–2025 and accessed through the Google Earth Engine Data Catalog (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/landsat; accessed on 14 August 2025). Image preprocessing included temporal filtering from January 1 to December 31 of each target year, retaining only scenes with cloud cover below 10% to construct annual mosaics. Cloud and shadow contamination were addressed using established masking procedures commonly applied in regional-scale satellite image analyses [23,40].

The coverage classes were defined according to the official nomenclature of MapBiomas Peru [41]. The classification process employed the Random Forest (RF) machine learning algorithm, selected for its flexibility, ease of implementation, and high accuracy in heterogeneous environments [42]. The polygonal ROIs were delimited by visual interpretation by two experts supported by free high-resolution images (Google Earth Pro v.7.3 -SAS Planet v.250505) scenes obtained for the years of interest (1990, 2020 y 2025) for 11 classes: forest (FOR), dry forest (DFOR), pine (PINE), shrubs (SHR), pastures (PAS), agriculture (AGR), agricultural mosaic (AGM), urban (URB), without vegetation (NOV), grassland (GRA) and water (WAT) [43]. To ensure proper class representation, training samples were generated using a stratified random scheme, assigning points proportionally to the mapped area of each class [44]. This approach reduced spatial bias and improved classification performance, consistent with studies highlighting that the representativeness of training is key to increasing the accuracy of LULC in complex environments [45,46]. In total, n = 1865 samples were generated, with the class size determined by the number of pixels within each ROI. The dataset was reproducibly divided (seed = 42) into 70% for training and 30% for validation [44,46,47]. The accuracy of the classification was assessed using the Kappa index [48] which quantifies the agreement between the classification and the reference data by randomly correcting for the expected agreement. Finally, the classified LULC map was exported from GEE and subsequently transformed into vector datasets for additional spatial processing and mapping using ArcGIS Pro v.3.5.

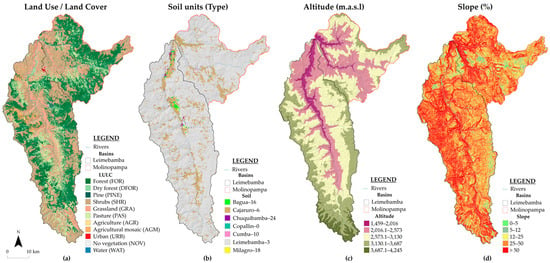

2.4. Dataset Input for the SWAT Model

LULC maps for 2020, 2030, 2040, 2050 scenarios and the incremental scenarios for agriculture, rangelands, and pine afforestation (15%) were used as input for SWAT. All cover classes were reclassified following the standard coding of the model, according to procedures applied in studies of Andean basins in Colombia and Ecuador [18,49,50]. Soil property information was retrieved from the SoilGrids database, providing gridded datasets at a spatial resolution of 250 m [51]. Within the Leimebamba basin, Andosols constitute the dominant soil group, covering approximately 82% of the total basin area and Cambisols (Cajaruro-6, 13%), Cumba-10 (0.8%), Bagua-16 (1.6%), Copallin-0 (0.7%), Milagro-18 (0.8%) and Chuquibamba-24 (1.1%); on the other hand, the Molinopampa basin is mainly distributed by (Leimebamba-3, 84%, Cajaruro-6, 10.2%, Bagua-16, 0.8%, Copallin-0, 2.6% and Chuquibamba-24, 2.4%), as shown in Figure 2b. The same 30 m DEM used for LULC classification (Figure 3c) was employed for slope derivation (Figure 3d) and for subbasin delimitation using QSWAT v2.0.1 integrated into QGIS 3.40 [52], this resolution was adopted for coherence with the LULC, due to its ability to represent the high Andean relief with a manageable computational cost.

Figure 3.

Spatial input layers used in the SWAT model: (a) land use/land cover, (b) soil units, (c) digital elevation model (DEM), and (d) slope gradients derived from the DEM.

Since the availability of weather stations in the area is limited, local records and grilled precipitation and temperature data (minimum and maximum) from PISCO-SENAMHI for the period 1984–2020 were used [38,53]. This dataset has been extensively applied in SWAT-based hydrological modeling to examine watershed responses under land-cover change scenarios [53,54]. Previous studies have demonstrated its suitability for evaluating hydrological sensitivity to land-use dynamics using the SWAT framework [55,56]. In addition, discharge records observed at the Naranjos measuring station (2006–2020; latitude: −5.75, longitude: −78.431), provided by SENAMHI, were used for model calibration and validation [57], allowing the simulation of hydrological conditions in different land use scenarios.

The climatic, topographic, soil, land-use, and hydrometric datasets employed to parameterize the SWAT model in this study are compiled in Table 1.

Table 1.

Datasets used as input for the SWAT model.

2.5. SWAT Model

The SWAT model is extensively applied in watershed studies due to its adaptability to diverse environmental settings, topographic configurations, and data availability conditions [8,58,59]. To ensure internal consistency between the data entered into the model, the raster datasets were harmonized with the native spatial resolution of the digital elevation model (~30 m) using nearest neighbor resampling implemented in QGIS [18]. During model setup, the watersheds were subdivided into multiple sub-basins, which were further discretized into hydrological response units (HRUs) based on unique combinations of slope classes, land use/land cover, and soil types. Each HRU represents a spatially homogeneous unit within the basin and allows a more detailed representation of terrestrial hydrological processes [55,60]. According to Equation (1), SWAT calculates the water balance per HRU, subsequently integrating these components at the sub-basin scale [10,61].

where Swt represents the soil water content at time t, SW0 denotes the initial soil water storage, Rday corresponds to daily precipitation, Qsurf refers to surface runoff, Ea indicates actual evapotranspiration, Esep represents percolation losses to the vadose zone, and Qgw denotes the groundwater contribution or baseflow returning to the channel on day t (mm).

2.6. Model Implementation and Performance Assessment

Hydrological simulations were conducted using SWAT (2012 release) through the QSWAT v2.0.1 interface implemented within the QGIS 3.40 environment [52]. The delimitation of the basin was carried out based on the DEM using a drainage area threshold of 100 km2, a criterion recommended in previous applications [19,62,63], allowing the identification of five main sub-basins in each basin (Figure 4a). HRUs were subsequently delineated based on distinct combinations of elevation, slope classes, land use/land cover, and soil characteristics, and hydrological simulations were performed to quantify individual water balance components. Meteorological forcing data, including minimum and maximum air temperature and precipitation for the period 1984–2020, were obtained from the PISCO gridded dataset [53]. A total of 16 and 10 grid cells were used to represent the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins, respectively, with climate inputs spatially assigned to sub-basins according to their centroid locations (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Delineation of sub-basins (a) and spatial allocation of PISCO climate grid cells (b) across the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins.

The calibration of the model was carried out with daily flow records from 2006 to 2020 from the Naranjos hydrological station, while data from 2015 to 2020 were used for validation. The process was executed in SWAT-CUP v5.1.6 using the SUFI-2 algorithm, following its application in previous studies [58,64,65,66], a set of fourteen model parameters was examined, and their relative influence was quantified through sensitivity analysis. Parameter relevance was assessed using p-values and associated statistical measures, while model performance was evaluated using standard metrics commonly applied in SWAT-CUP-based hydrological model calibration [55,67,68].

2.7. Assessment of Hydrological Model Performance

The performance of the model during calibration and validation was evaluated using the R2, PBIAS and KGE indicators, considering its ability to reproduce the flow series and detect the effects of LULC change on the water balance. The KGE index integrates the correlation, relative bias, and relationship between standard deviations from observed and simulated values, according to Equation (2). The rating ranges used to interpret the monthly performance are presented in Table 2.

where r is the correlation between the real and simulated data; β is the relative bias, expressed as the ratio between the means of the observed and simulated data; γ is the ratio of the standard deviations between the observed and simulated data.

Table 2.

Threshold values for assessing monthly streamflow simulations.

2.8. Landuse Scenary

The simulation of future land use and land cover scenarios was carried out with MOLUSCE (Modules for Land Use Change Simulations), a QGIS 3.40 add-on developed by Asia Air Survey y NextGIS (https://github.com/nextgis/molusce (Accessed on 15 August 2025). This tool estimates the percentages of historical change, generates probability matrices and, based on predictor variables, projects future changes in the LULC [69,70].

For this study, the distance to roads, rivers and population centers, as well as slope and altitude of the terrain, were used as predictor variables. The 12.5 m DEM from ALOS PALSAR (ASF Data Search) allowed the slope to be derived. Vector layers were obtained from regional zoning studies [71] and distance maps were generated using the Euclidean distance function in QGIS 3.40.

The reliability of the model was evaluated by comparing a projected map for 2020, generated from LULC 2000–2010, with the actual map of 2020, internally validating the performance using the Kappa index [72]. To incorporate local spatial context into LULC transitions, the model employed a 3 × 3 pixel neighborhood filter, while 500 iterations were applied to ensure convergence and stability of the simulated patterns. These parameter choices follow standard practice in cellular automata–based LULC modeling [73,74,75]. The model was trained repeatedly until an AUC ≥ 0.81 was obtained, categorized as Near Perfect [76]. With this configuration, the scenarios for 2030, 2040 and 2050 were simulated using cellular automata.

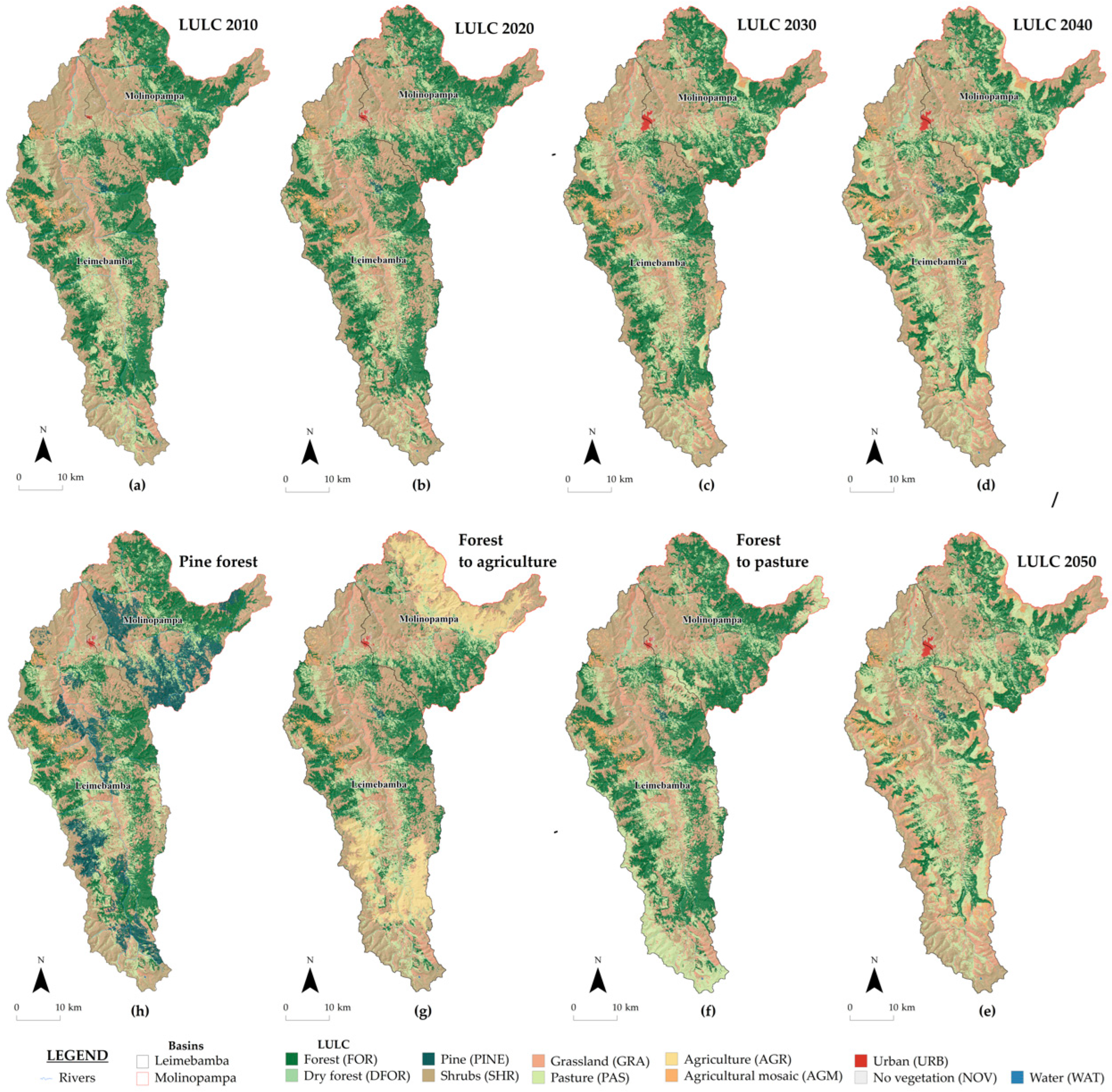

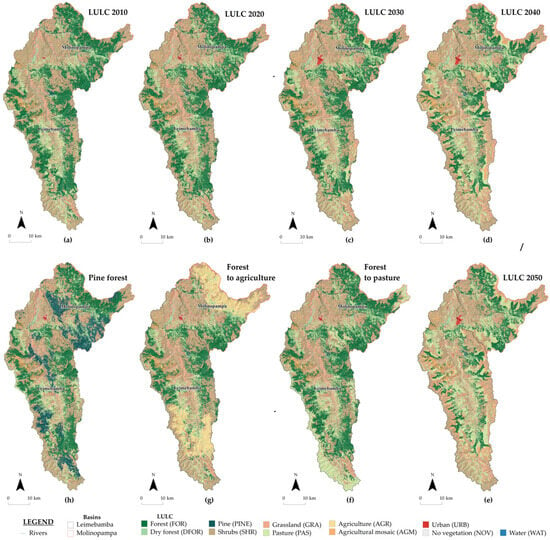

Finally, specific scenarios for deforestation, agricultural and rangeland expansion, as well as pine afforestation (Figure 5), were generated by mapping in ArcGIS Pro 3.5.0. 15% of forest (2020) was replaced by agriculture and pastures, and 5% of shrublands and degraded areas by pine plantations, following percentages consistent with regional reforestation initiatives (https://geo.serfor.gob.pe/visor/ (accessed on 10 August 2025)) and similar values used in previous studies [77,78]. A summary of the scenarios used and the modification rules applied is presented in Table 3.

Figure 5.

Land use/land cover maps for the Utcubamba basin under historical conditions and simulated scenarios: (a) LULC 2010, (b) baseline 2020, (c) projected 2030, (d) projected 2040, (e) projected 2050, (f) forest-to-pasture conversion scenario, (g) forest-to-agriculture expansion scenario, and (h) pine afforestation scenario.

Table 3.

Summary of simulated LULC scenarios and modification rules.

3. Results

3.1. Land Use/Land Cover Classification Results

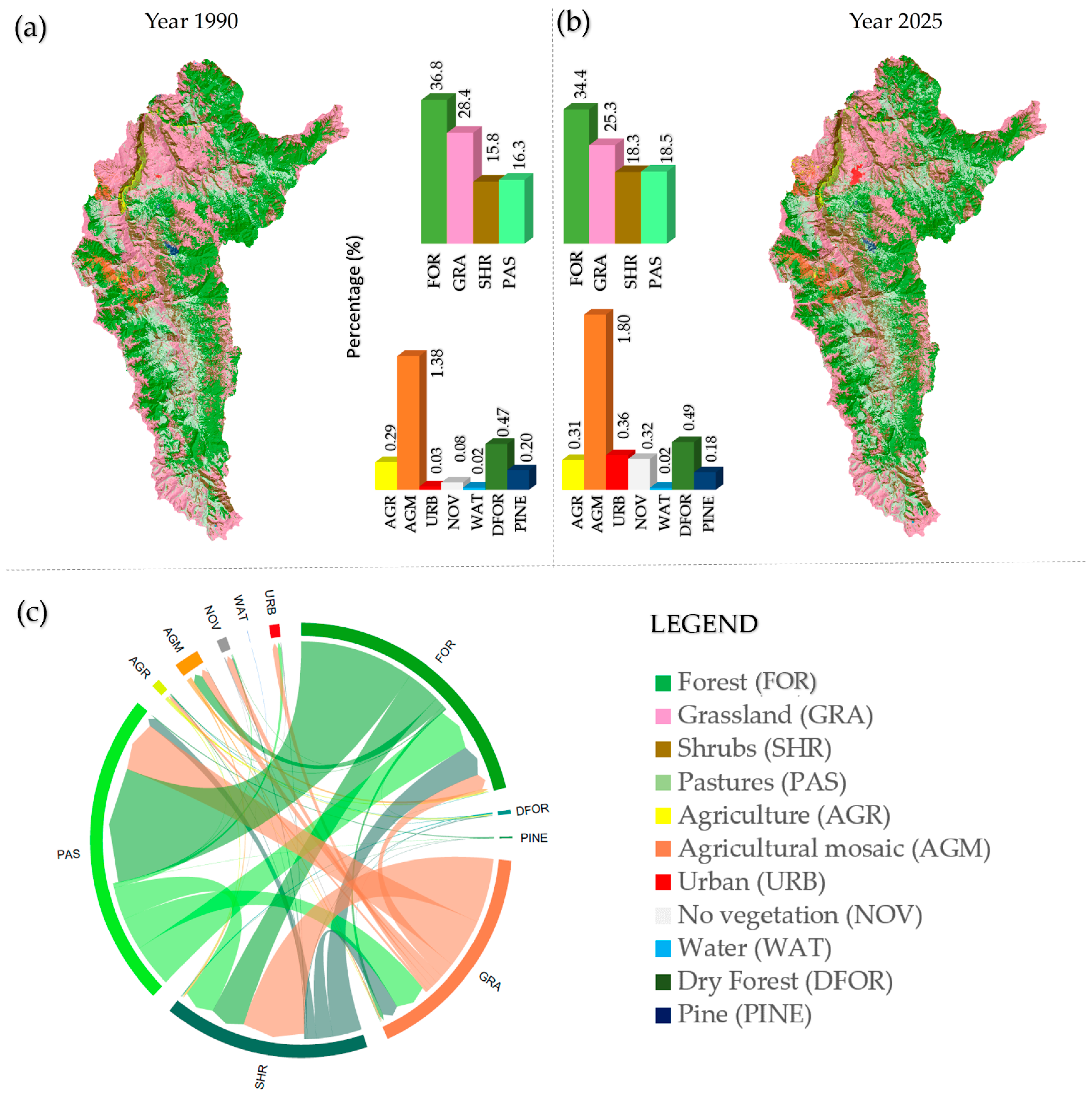

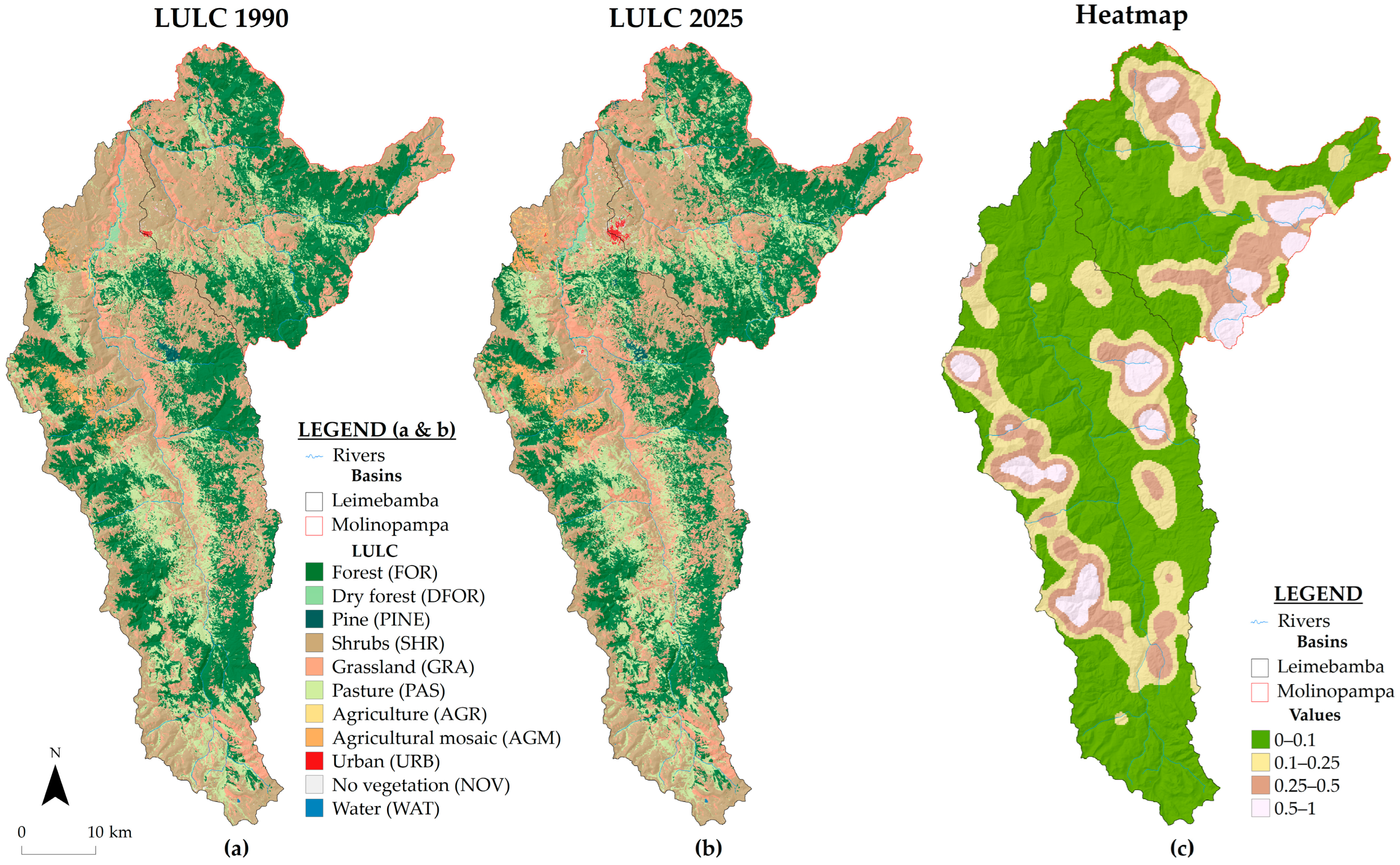

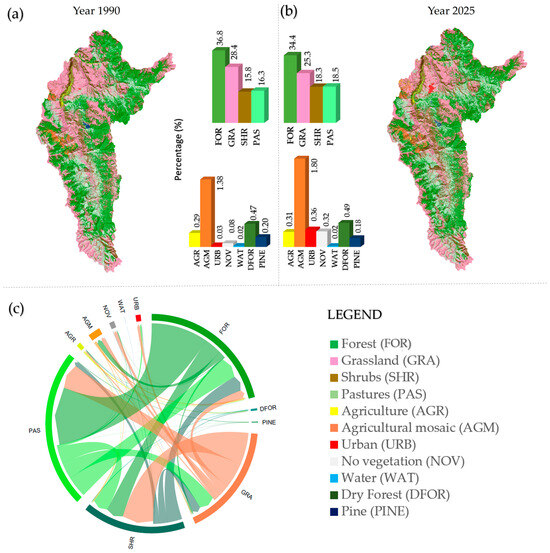

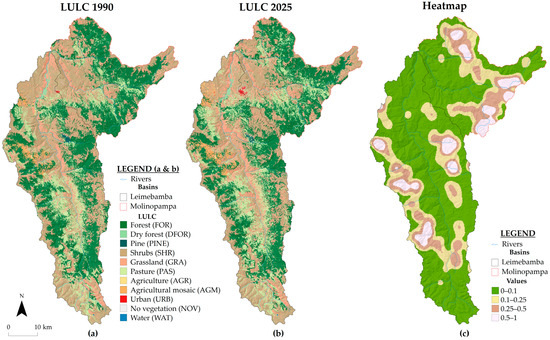

The LULC classification exhibited strong performance in both evaluated years, achieving Kappa coefficients of 0.91 and 0.93 for 1990 and 2025, respectively. Forests, grasslands, shrublands, and pastures emerged as the predominant land-cover categories. In the transition from 1990 to 2025 of the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins, the FOR class went from 101,385.09 ha (36.83%) to 94,716.27 ha (34.41%), while GRA with 78,316.47 ha (28.45%) decreased to 69,568.83 ha (25.28%), and the SHR class with 43,683.75 ha (15.87%) rose to 50,535.63 ha (18.36%), while PAST from 45,069.75 ha (16.37%) increased to 50,865.03 ha (18.48%). By 2025, classes such as URB, NOV, and AGM experienced significant changes, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Area (in percentages) of change for each land-use class in 1990 and 2025: (a) percentage of change for the year 1990, (b) percentage of change for the year 2025, and (c) transition of changes from 1990 to 2025.

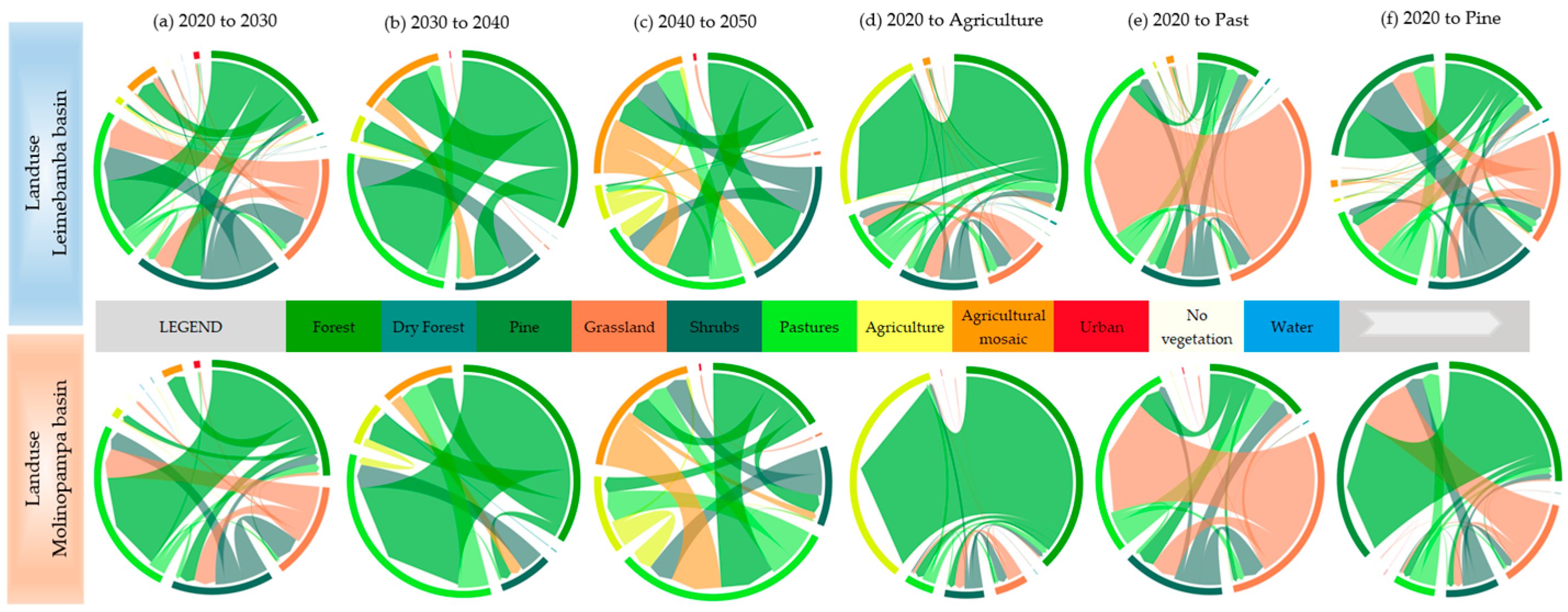

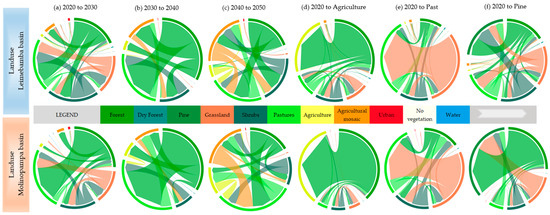

In the same way, the changes for each Landuse scenario were analyzed as shown in Figure 7, with primary forest cover in all scenarios reduced by 12.7, 40.4, 54.2, 28.5, 13.8 and 5.6% in the Leimebamba basin (upper) and 8.5, 21.9, 27.3, 42.8, 2.1 and 33.5% in the Molinopampa basin (lower) according to future scenarios (a–c) and deforestation (d–f).

Figure 7.

Landuse change transition for each scenario (a–f) for both the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins.

Anthropogenic influences are especially pronounced in the upper reaches of the basin, where land-use changes are most heavily concentrated, as illustrated in Figure 8c.

Figure 8.

Land use/land cover (LULC) distribution for 1990 (a) and 2025 (b), together with the spatial heatmap depicting the concentration of land-use changes across the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins (c).

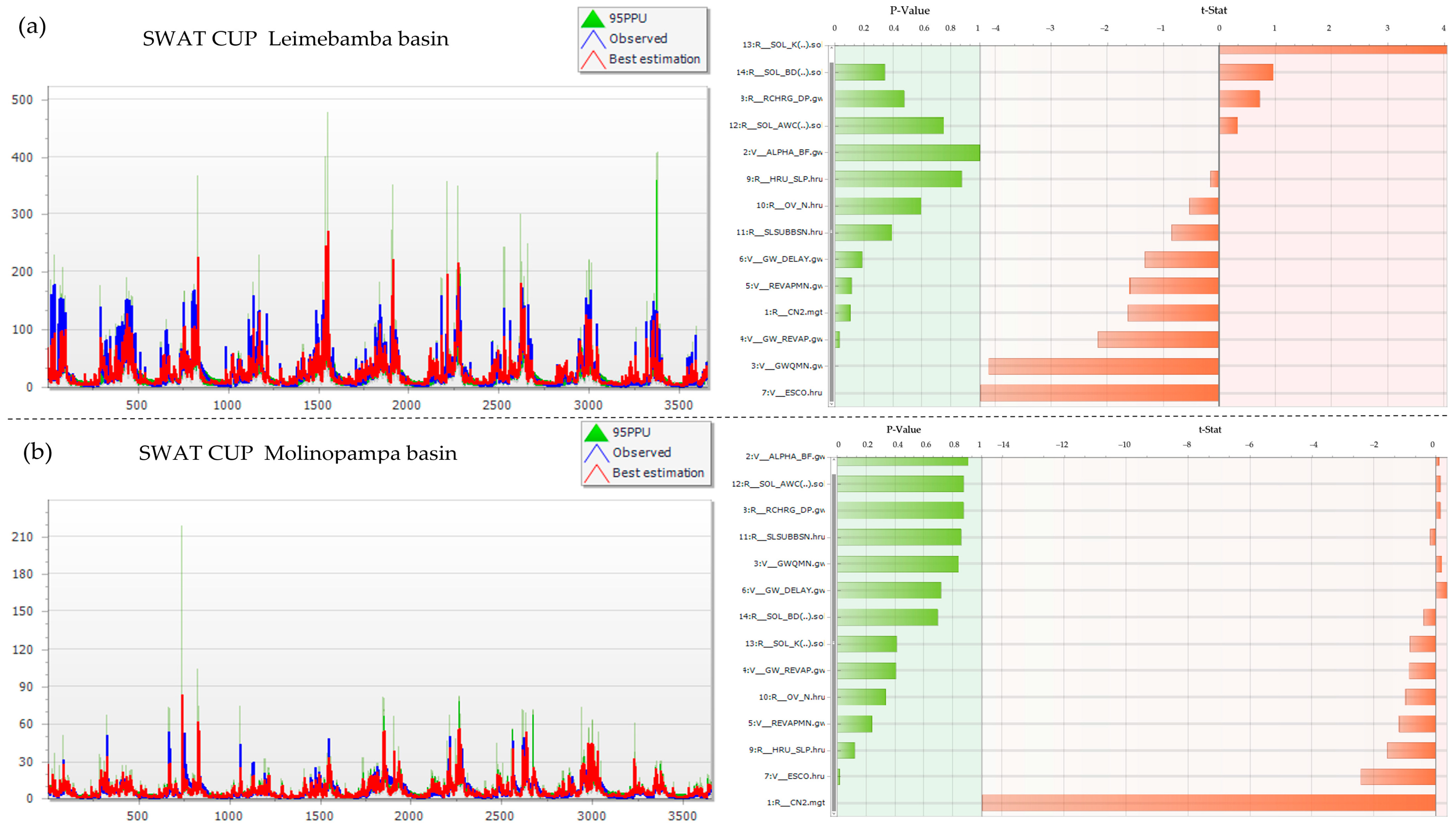

3.2. Sensitivity, Calibration, and Validation Process for the SWAT Model

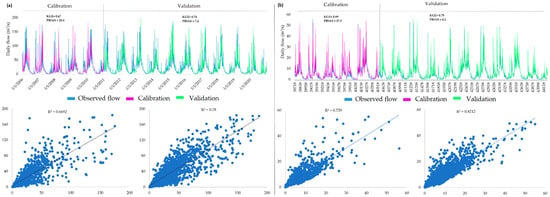

Calibration with SWAT-CUP adequately reproduces the hydrological dynamics in both basins. In Figure 9a, the simulated hydrographs (red line) follow the seasonality and timing of observed events (blue line), and the 95PPU uncertainty band (green) encompasses most peak flows, with minor discrepancies in isolated extremes.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity analysis of 14 parameters: (a) histogram and uncertainty of the Leimebamba basin, (b) histogram and uncertainty of the Molinopampa basin.

The global sensitivity analysis identified CN2, ALPHA_BF, ESCO, SOL_AWC, GW_DELAY, and GWQMN as the most influential parameters in the Leimebamba basin, based on t-statistics and p-values. In the Molinopampa basin (Figure 9b), CN2.mgt, CH_K2.rte, CH_N2.rte, ALPHA_BF, GW_DELAY, and GWQMN presented the highest sensitivity.

Model performance statistics (NSE, KGE, PBIAS, and R2) confirm adequate calibration and validation for both basins, with values within recommended thresholds for daily streamflow simulation.

After the sensitivity analysis, as shown in Table 4, minimum and maximum values for validation are presented, together with the validation parameter value.

Table 4.

Calibration and validation parameters for the SWAT model.

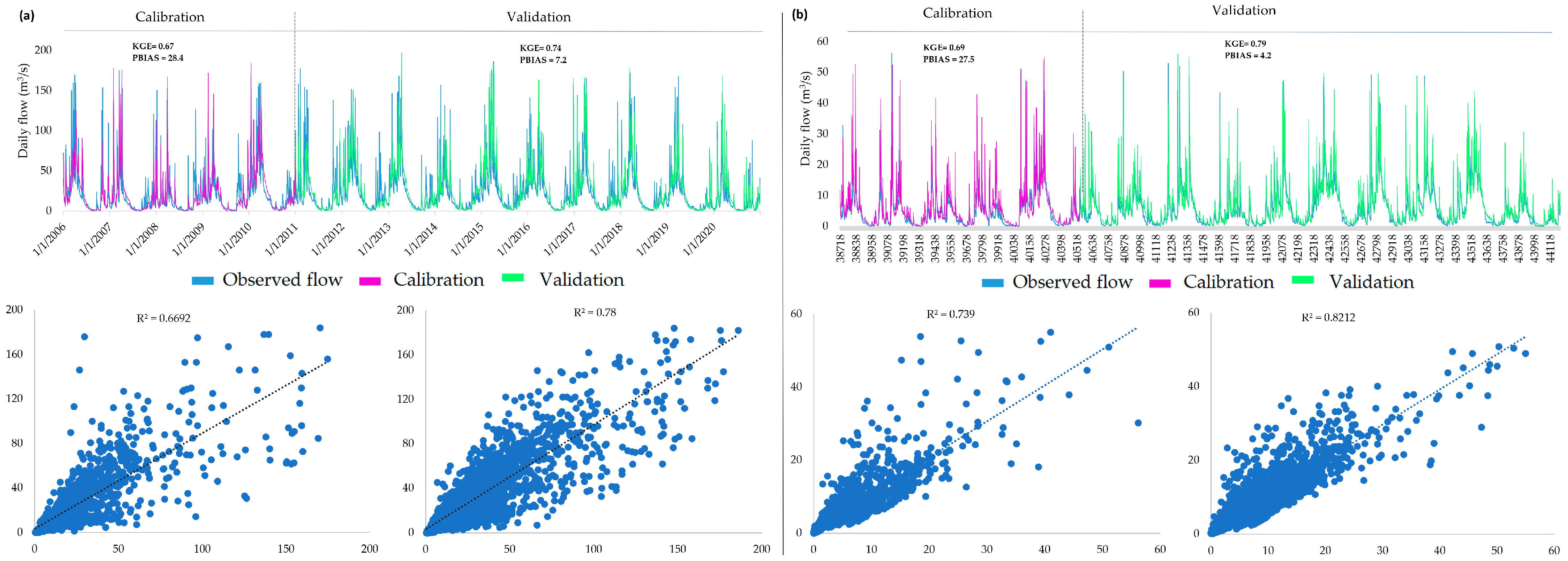

3.3. Performance of the SWAT Hydrological Model Under Different Scenarios

Figure 10 shows the model’s performance for the calibration and validation phases. For the calibration period (2006–2015), the model achieved KGE values of 0.67 and 0.69, R2 values of 0.62 and 0.73, and PBIAS values of 28.4% and 27.5% for the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins, respectively. During the validation period (2016–2020), model performance showed a clear improvement, with KGE increasing to 0.74 and 0.79, R2 to 0.78 and 0.82, and PBIAS decreasing to 7.2% and 4.2%, respectively. These results indicate that the model reliably reproduces the hydrological dynamics observed at the virtual hydrometric stations for the Leimebamba basin (Figure 10a) and the Molinopampa basin (Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

Comparison of observed and simulated daily streamflow for the calibration (2006–2015) and validation (2016–2020) periods in the Leimebamba (a) and Molinopampa (b) basins.

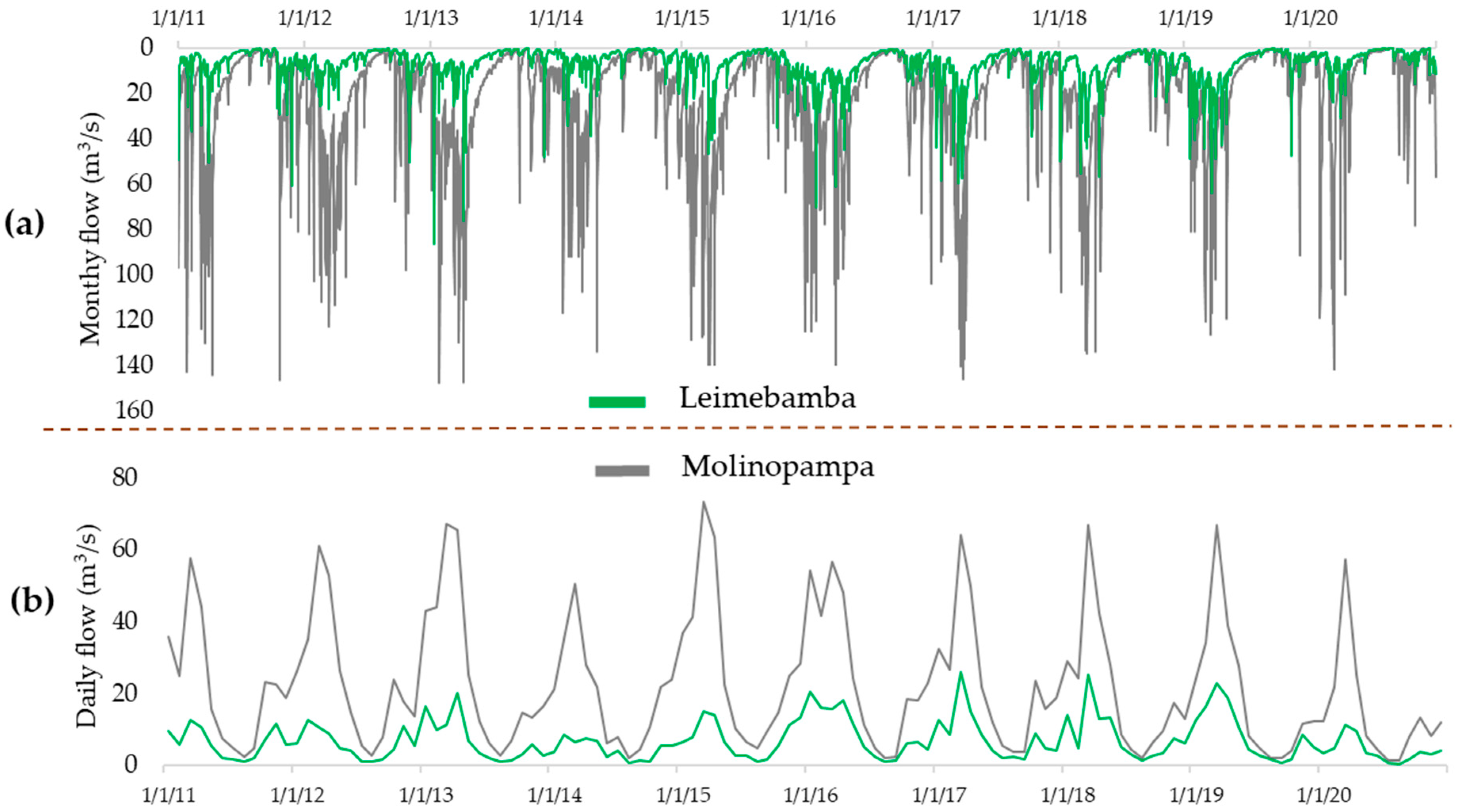

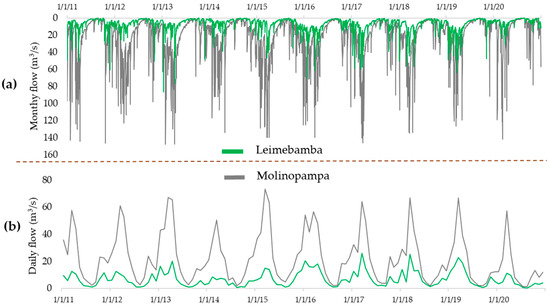

3.4. Flow Dynamics in the Leimebamba and Molinopampa Basins

The Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins display a well-defined seasonal hydrological regime, characterized by peak flows predominantly occurring between December and April, while low-flow conditions are generally observed from July to September and may extend into October. At the daily scale (Figure 11a), streamflow simulations driven by the PISCO dataset for the 2010–2020 period capture pronounced short-term variability, with maximum discharges exceeding 150 and 70 m3/s, and minimum values decreasing to approximately 3 and 2 m3/s, respectively. In terms of averages and monthly scale (Figure 11b), the maximum flood is between 73.3 and 25.9 m3/s, the dry periods fluctuate between 4.4 and 2.3 m3/s and maintain a historical average of 21.83 and 8.40 m3/s.

Figure 11.

Streamflow dynamics for the 2011–2020 decade based on PISCO climate data, showing (a) monthly flow patterns and (b) mean daily flow variability.

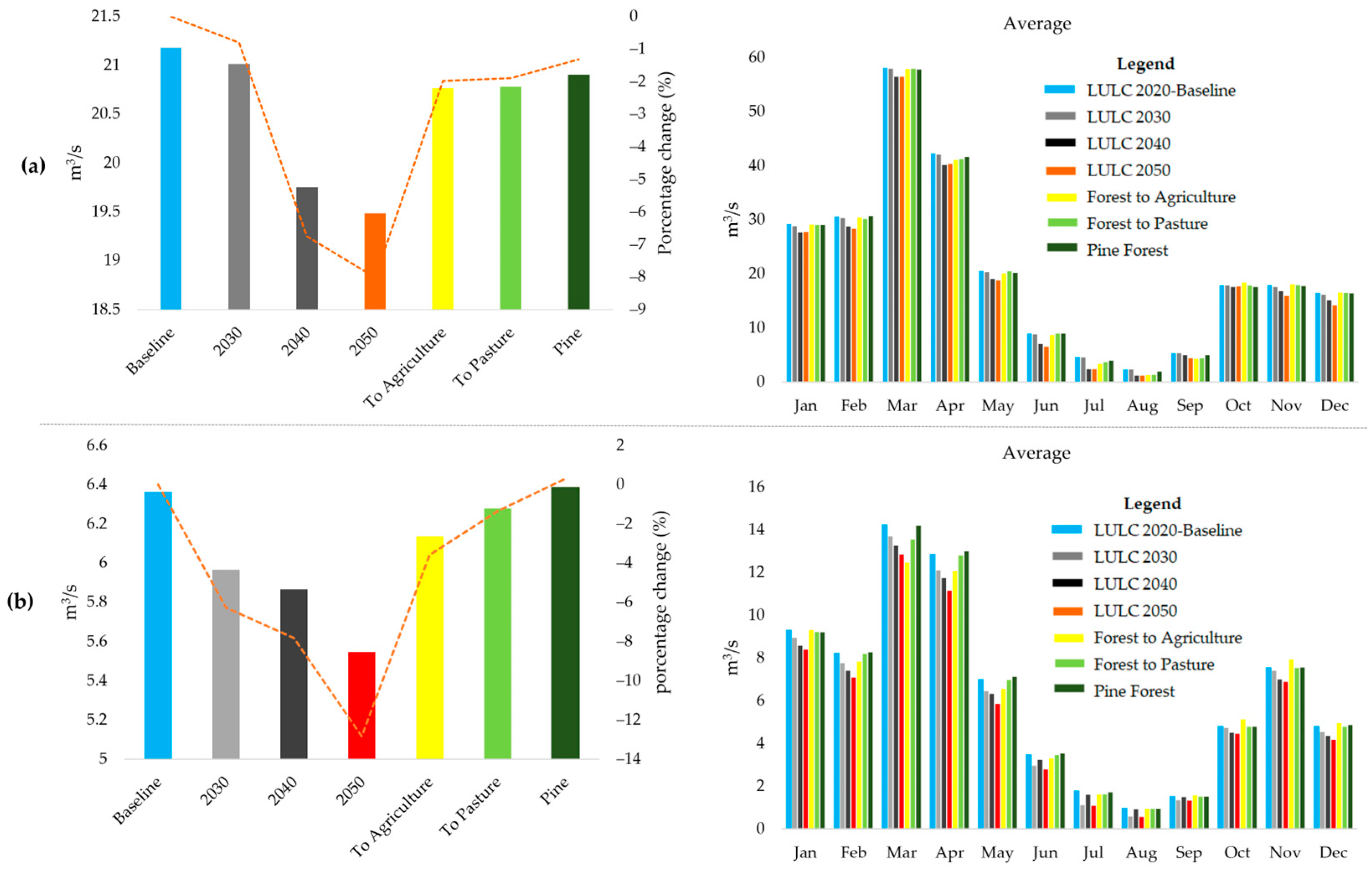

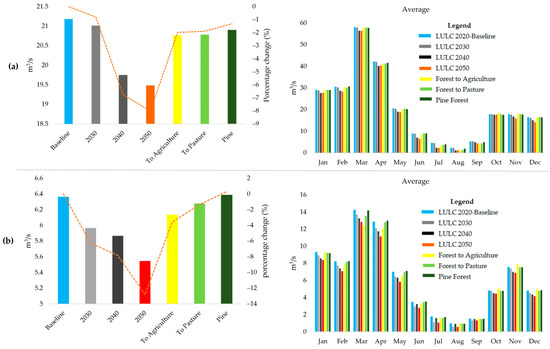

3.5. Projected Hydrological Responses to LULC Change

In Leimebamba, the average annual results for 2010–2020 (Figure 12a) show a historical mean flow close to 22 m3/s, with maximum flows of 55–65 m3/s in March–April and minimums of 2.1–3.4 m3/s in July–August (Figure 12b). Compared to the 2020 baseline, future simulations indicate progressive reductions in the average annual flow of negligible change <0.1% (2030), −6.8% (2040) and −8.0% (2050), −2.0% (Agriculture), −1.9% (Past) and −1.3% (Pine). Molinopampa (Figure 12b), the historical average flow is 6.36 m3/s. Future simulations show reductions in flow from −6.3% (2030), −7.8% (2040) and –12.8% (2050), agricultural expansion reducing the average flow by −3.6%, conversion to pastures of –1.3%, and pine afforestation producing a slight increase of +0.3%.

Figure 12.

Percentage changes and monthly averages by scenarios: (a) Leimebamba Basin, and (b) Molinopampa Basin.

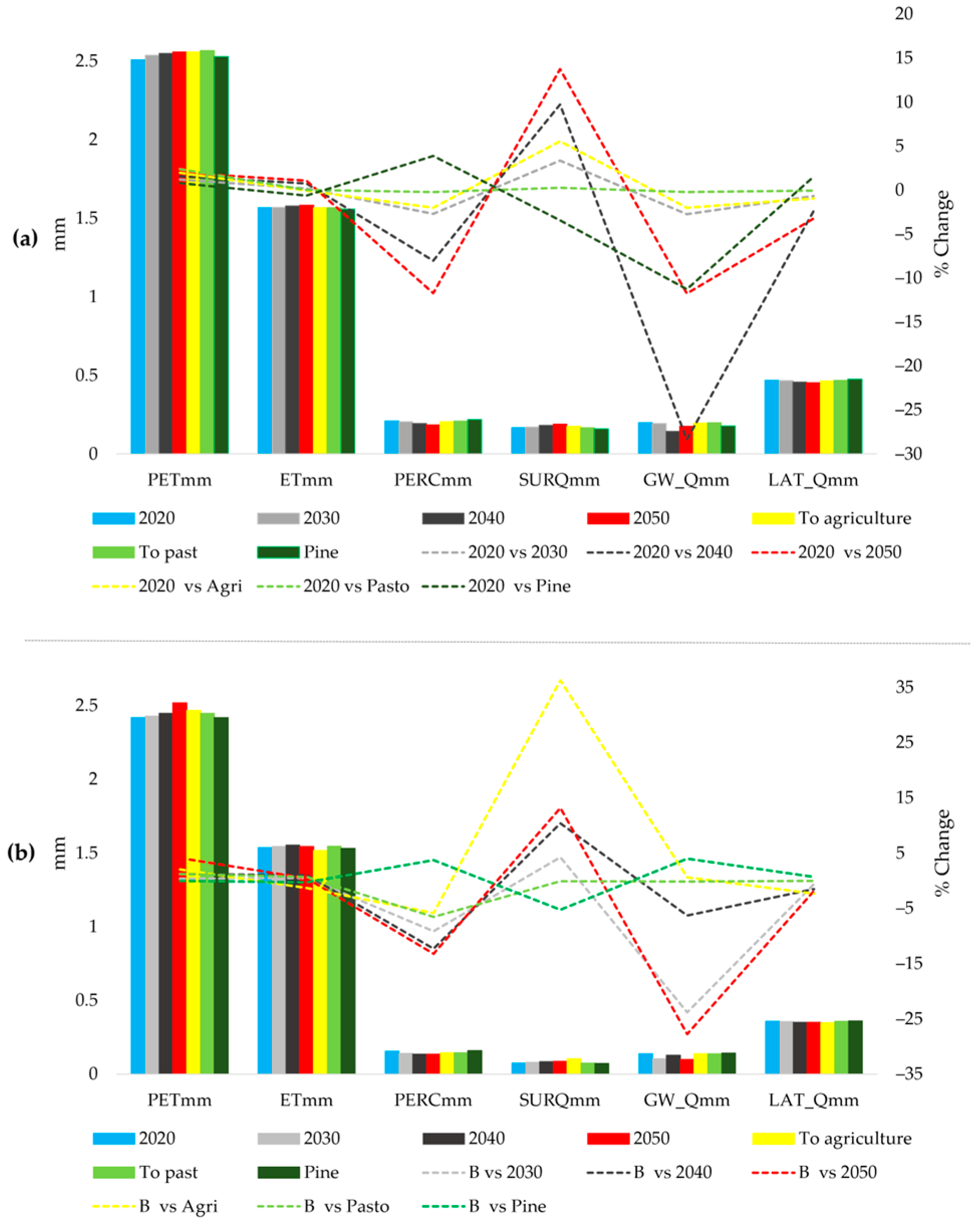

3.6. Water Balance Component Responses to LULC Scenarios

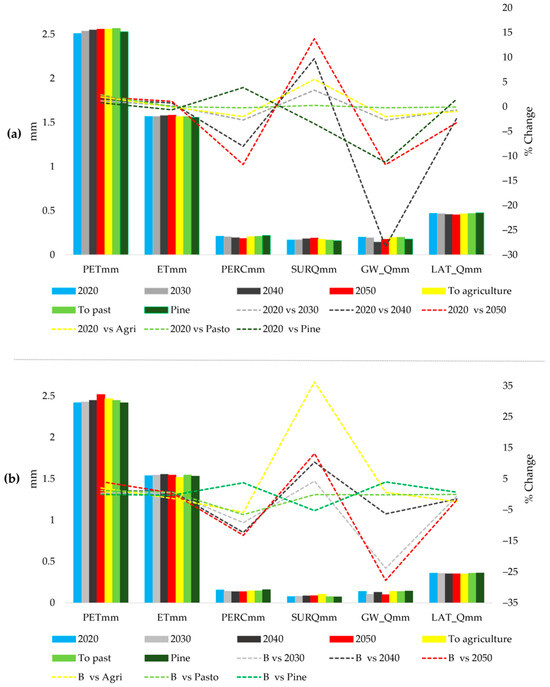

According to Figure 13, potential evapotranspiration (PET) remains almost stable in both basins; the largest increase is observed in Molinopampa for the future scenario 2050, with +4.1% compared to 2020, and in Leimebamba the changes do not exceed +2.4%. Real evapotranspiration (ET) shows very small variations, with maximum increases of +1.1% (Leimebamba, 2050) and +1.0% (Molinopampa, 2040) and maximum decreases of –0.6% (Leimebamba, Pine).

Figure 13.

Projected changes in balance components in future and deforestation scenarios vs. Landuse baseline 2020: (a) changes in the Leimebamba basin and (b) changes in the Molinopampa basin.

Percolation (PERC) is one of the most sensitive components: under future scenarios, reductions reach –11.7% in Leimebamba and –13.2% in Molinopampa (2050) (Table 5). In contrast, pine afforestation increases percolation to +3.9% in Leimebamba and +3.7% in Molinopampa. Surface runoff (SURQ) shows increases of up to +13.8% by 2050 in both basins, while changes in land use amplify these contrasts: agricultural expansion increases SURQ to +5.5% in Leimebamba and +36.3% in Molinopampa, while pine afforestation reduces it to –3.4% and –5.3%, respectively.

Table 5.

Projected differences in water balance components compared to the 2020 baseline scenario.

The contribution of groundwater (GW) registers the largest relative reductions among the components: –28.4% in Leimebamba (2040) and –27.7% in Molinopampa (2050) under future scenarios. In the deforestation scenarios, the greatest variation corresponds to pine forestation, with –11.3% in Leimebamba and +4.0% in Molinopampa. Lateral flow (LAT) shows moderate decreases in the future, with minimum values of –3.2% in Leimebamba and –1.8% in Molinopampa; the extension of agriculture produces the greatest reduction (up to –2.3% in Molinopampa), while the scenario with pine generates the maximum increases, of +1.5% and +0.7% in Leimebamba and Molinopampa, respectively.

4. Discussion

The LULC classifications for the historical years 1990 and 2025 obtained Kappa coefficient values of 0.88 and 0.91, respectively, indicating a good performance of the Random Forest classifier implemented in GEE using a total sample size n = 1865. Although the distribution of the samples among the LULC classes was not completely balanced due to the real spatial heterogeneity of the land cover categories in the study area [23,48]. The high accuracy in classification suggests that moderate class imbalance did not affect model performance, which is consistent with previous studies that highlighted the robustness of the RF classifier under non-uniform class distributions [79,80]. The inclusion of spectral indices and topographic variables improved class separability, in agreement with findings reported for Andean–Amazonian ecosystems [15]. The observed reduction in native forests and the expansion of agriculture, shrubland, and grasslands reflect persistent anthropogenic pressures in rural communities in the Peruvian Andes [22]. These changes intensify landscape fragmentation and modify hydrological regulation as they modify land cover for infiltration, runoff, and groundwater recharge [23,49]. These changes are notable as there is an increase in the frequency of droughts, low flows close to zero, and hydrological alerts for exceeding maximum thresholds. Previous studies in mountain basins have reported similar patterns, where their main cause is intensification of land use, where fragmentation and soil degradation alter hydrological components [81,82].

The sensitivity assessment highlighted values of parameters that control runoff that differ between basins. In Leimebamba, subsurface processes predominate, since the parameters associated with soil evaporation and interactions with groundwater (ESCO, GW_REVAP, GWQMN) strongly influence the generation of baseflow and the attenuation of peaks as maximums and minimums. In Molinopampa, CN2.mgt showed the highest sensitivity, indicating that runoff generation is mainly driven by surface processes. Meanwhile, channel transmission parameters (CH_K2, CH_N2) and aquifer-related parameters (ALPHA_BF, GW_DELAY, GWQMN) are also important parameters in the dynamics of the recession. The sensitivity results are the reflection and evidence of the very heterogeneous geomorphology, the dominant cover classes and the anthropogenic activities. Previous studies employing SWAT have shown that mountain basins exhibit high sensitivity to parameters as a result of steep slopes, soil heterogeneity, and land cover gradients [19,59,62]. Additional studies conducted in hydrological modeling in rainforest and tropical mountain ecosystems highlight the importance of underground storage and LULC dynamics directly affect runoff [18,82].

LULC’s future scenarios (2030; 2040, and 2050) reveal pronounced changes in hydrological components in both basins. In the case of percolation, it decreases markedly to (−11.7% to −13.2%), while surface runoff increases (+13.2% to +13.7%). Lateral flow is also reduced and the contribution of groundwater shows significant losses, reaching up to −27.7% by 2050. These displacements indicate a decrease in hydrological buffering capacity and a lower availability of baseflow. Meanwhile, agricultural expansion intensifies the response to runoff, especially in Molinompa, where surface runoff increases by +36%. These trends imply greater vulnerability to both droughts and floods, coinciding with findings from regional studies that link changes in LULC, forest reduction and hydrological imbalance [18,55].

For the pine afforestation scenario in both basins, the hydrological responses of the basins have been moderate and mixed, where percolation increased slightly (+3.7% to +3.9%), surface runoff decreased in Leimebamba (−3.4%) and lateral flow increased slightly. Despite this, groundwater contributions showed contradictory responses, with a reduction of −11.3% in Leimebamba and only a slight improvement (+1%) in Molinopampa. These results show that pine afforestation actions are not enough to reverse the decrease in base flow or to cushion the increase in runoff levels. Previous studies have also reported limited hydrological benefits of afforestation with exotic species in Andean–Amazonian regions, given their higher water demand and lower soil-water retention compared to native and biodiverse vegetation [83,84]. Other recent studies also emphasize that the hydrological outcomes of afforestation depend largely on species selection, planting density and soil characteristics [85,86].

The critical analysis of the results indicates that micro-watersheds with high agricultural-livestock activity present the greatest hydrological vulnerability. In Leimebamba, micro-basin 3 shows a persistent loss of forest cover, while in Molinopampa, micro-basins 3 and 4 show extensive forest and grassland degradation. These conditions reduce infiltration capacity, increase surface runoff, and overcome the risk of erosion [63,87]. Although there are reforestation initiatives in both basins, they have prioritized Pinus plantations, as documented by SERFOR [77]. This strategy limits ecological and soil recovery in conjunction with hydrological stability. Various studies indicate that using native species could provide better regulation of water processes, better soil recovery, and greater resilience to climate variability and risks such as forest fires and landslides [88,89].

The performance of the SWAT model was robust with values (KGE 0.74–0.79; PBIAS 4.2–7.2%), despite the limitation of hydrometeorological stations and the dependence on gridded climate data. Improving and expanding hydrological monitoring networks and integrating dynamic LULC scenarios will be critical to anticipate extreme peaks and identify vulnerable and high-risk areas for droughts and floods. The observed changes in runoff, groundwater recharge, and baseflow alert the need for basin-scale planning that integrates land use management, ecosystem restoration, irrigation efficiency, and water security strategies for diverse uses such as population [90]. Meanwhile, the Andean–Amazonian transition zone, such as the one in this study, presents unique challenges due to its ecological heterogeneity, rapid land-use change, and vulnerability to climatic extremes, which is why recent research underscores the importance of adaptive management and socio-environmental governance frameworks in the territory [91,92].

In the present study, there are aspects that represent limitations and opportunities for future research. The use of static climate data limits the capture of hydrological responses under shared socioeconomic scenarios of future climate [93]. Calibration from a single measuring station reflects common monitoring constraints in Andean basins [18,22], although the results of the sensitivity analysis and statistical correlation between the observed and simulated flow were optimal. LULC projections of cellular automata simplify socio-environmental dynamics [94] but validation with the 2020 map ensures the efficiency of the projection. Finally, the absence of participatory socio-hydrological approaches highlights a line of development relevant to the objectivity of LULC’s projection models. Taken together, these considerations do not limit the scope of the study, but rather delineate concrete opportunities for methodological refinement and for a broader and more diverse integration of data sources in subsequent work [91,95].

5. Conclusions

In the present study, the historical changes (1990–2025) and future projections (2030–2050) of LULC in the GIS environment with MOLUSCE in the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins were analyzed, as well as their effects on hydrological dynamics through the application of the SWAT model. In this sense, the results show a progressive and sustained loss of forest cover, accompanied by the expansion of agricultural areas and pastures from 1990 to 2025, which confirms a trend of persistent territorial transformation in both basins.

On the other hand, and despite the limited availability of climatic and hydrometric information, the performance of the model was satisfactory (KGE = 0.74–0.79; PBIAS = 4.2–7.2%), which consequently supports its applicability in Andean basins characterized by data-scarce conditions. These results acquire value if future studies are considered in regions with limitations of climatic, LULC and soil data.

Likewise, LULC’s future scenarios project significant impacts on flow regimes, highlighting reductions of up to 39% in minimum flows and increases in more than 5% in maximum flows. Consequently, the water balance shows a shift towards higher surface runoff that can be increased by up to 36% along with a decrease in groundwater contributions of up to 28%, suggesting faster hydrological responses and a reduction in baseflow. It should be noted that these effects are intensified under scenarios of agricultural expansion, highlighting the high vulnerability of the higher altitude sub-basins, which depend to a large extent on the hydrological regulation provided by forest cover and wetlands.

In addition, by 2050, forest losses of around −54% are projected in the Leimebamba basin and −27% in Molinopampa. In this context, afforestation with pine species shows limited hydrological benefits; therefore, these results reinforce the need to prioritize the conservation and restoration of vegetation with native species as a key strategy to maintain hydrological resilience. Overall, the findings underscore the importance of moving towards integrated watershed management, accompanied by strengthened monitoring systems and adaptive land-use planning. Finally, future studies should incorporate dynamic climate data, calibration schemes at various strategic points in the basin, and participatory socio-hydrological approaches, in order to improve water security in the Andean–Amazon.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18030365/s1, Figure S1: Historical flow from 1991 to 2020 using PISCO climate data: (a) monthly daily flow variability; (b) monthly average flow patterns; Figure S2: Projected flows under the Landuse scenarios, daily and monthly flows for a period (2001–2020): (a) flows from the Leimebamba basin, (b) flows from the Molinopampa basin; Figure S3: Percentage changes in the Leimebamba basin: (a) maximum and (b) minimum; for the Molinopampa basin: percentage changes (c), maximum and (d) minimum; Table S1: Area (in hectares) and percentage relative to the total area of the basin for each class of land cover in the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins for the years 1990 and 2025, including absolute and relative differences; Table S2: Area (in hectares) of the total basin area for each land cover class in the Leimebamba and Molinopampa basins for the different Landuse scenarios; Table S3: Training points and validation of supervised classification in GEE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and study design were led by A.S.R.-F., R.S.L. and J.O.S.-L. Methodological development and hydrological modeling were carried out by A.S.R.-F., J.A.Z.-S., M.A.G.-A. and A.J.M.-M., with contributions from J.O.S.-L. and E.B. Data curation and formal analysis were performed by A.S.R.-F., J.A.Z.-S., A.J.M.-M. and T.B.S.-M. Investigation activities, including data compilation and field-related support, were conducted by A.S.R.-F., J.A.Z.-S., J.O.S.-L., A.J.M.-M., K.M.T.-T., M.O.-C., C.P. and E.B. Software development and technical implementation were undertaken by A.S.R.-F., M.A.G.-A. and N.B.R.-B. The original draft of the manuscript was written by A.S.R.-F., while critical review and editing were performed by A.S.R.-F., J.A.Z.-S. and E.B. Supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition were provided by C.P., M.O.-C. and E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Public Investment Project “Creation of a Geomatics and Remote Sensing Laboratory at the Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas” (GEOMATICA, CUI N°. 2255626). The article processing charges (APC) were covered by the Vice-Rectorate for Research of the Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Water Authority (ANA) and the National Meteorology and Hydrology Service of Peru (SENAMHI) for providing the hydrological and climatic datasets used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the outcomes of this study.

Abbreviations

| ANA | National Water Authority of Peru |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GW_Q | Groundwater Contribution to Streamflow (baseflow) |

| HRU | Hydrologic Response Unit |

| KGE | Kling–Gupta Efficiency |

| LULC | Land Use and Land Cover |

| MOLUSCE | Modules for Land Use Change Simulations |

| PBIAS | Percent Bias |

| PISCO | Peruvian Interpolated data of SENAMHI’s Climatological and Hydrological Observations |

| QSWAT | QGIS Interface for the SWAT model |

| RF | Random Forest |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| SENAMHI | National Meteorology and Hydrology Service of Peru |

| SERFOR | National Forest and Wildlife Service |

| SWAT | Soil and Water Assessment Tool |

| SWAT-CUP | SWAT Calibration and Uncertainty Programs |

References

- Shemer, H.; Wald, S.; Semiat, R. Challenges and Solutions for Global Water Scarcity. Membranes 2023, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, D.; Babel, M.S.; Kamalamma, A.G. Assessing the Impact of Climate and Land-Use Changes on the Hydrologic Cycle Using the SWAT Model in the Mun River Basin in Northeast Thailand. Water 2023, 15, 3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A. Changing Hydrology of the Himalayan Watershed. Curr. Perspect. Contam. Hydrol. Water Resour. Sustain. 2013, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meran, G.; Siehlow, M.; von Hirschhausen, C. Integrated Water Resource Management: Principles and Applications. In The Economics of Water; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 23–121. [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, S.; Shakya, N.M. Integrated Assessment of Climate Change and Land Use Change Impacts on Hydrology in the Kathmandu Valley Watershed, Central Nepal. Water 2019, 11, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Smakhtin, V. Revue Des Modèles Hydrologiques Globaux. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2015, 60, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Pereira, A.F.; Treminio Martínez, J.M.; Méndez Rivas, R.A.; Fabiola, A.; Pereira, O.; Treminio Martínez, J.M.; Rivas, R.M. Una Revisión Del Modelo WEAP 21 y SWAT Para La Planificación de Los Recursos Hídricos. Rev. Cienc. Tecnol. Higo 2022, 12, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traverso, K.; Lavado Casimiro, W.; Felipe, O. Monitoreo Hidrológico en Tiempo Cuasi Real en la Vertiente del Pacífico Empleando el Modelo Hidrológico SWAT; Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú: Lima, Peru, 2022.

- Ana, O.; Treminio, J. A Review of the Weap 21 and Swat Model for Water Resources Planning. El Higo Rev. Cient. 2022, 12, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, J.G.; Srinivasan, R.; Muttiah, R.S.; Williams, J.R. Large Area Hydrologic Modeling and Assessment. Part I: Model Development. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1998, 34, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.G.; Allen, P.M.; Bernhardt, G. A Comprehensive Surface-Groundwater Flow Model. J. Hydrol. 1993, 142, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orianna Sofía, O.S.; Méndez Rivas, R. Aplicación de Modelos Hidrológicos. Rev. Cienc. Tecnol. El Higo 2022, 12, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MapingGIS Molusce: Simulación de Cambios de Usos del Suelo en QGIS. Available online: https://mappinggis.com/2024/10/molusce-plugin/ (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Roy, S.K.; Kumar, A. Monitoring the LULC Changes in the Rurban Region of Berhampore Municipality Using MOLUSCE Plugin of QGIS. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. 2025, 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceño, N.B.R.; Castillo, E.B.; Quintana, J.L.M.; Cruz, S.M.O.; López, R.S. Deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon: Indexes of Land Cover/Land Use (LC/LU) Changes Based on GIS. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2019, 81, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colín-García, G.; Palacios-Vélez, E.; López-Pérez, A.; Bolaños-González, M.A.; Flores-Magdaleno, H.; Ascencio-Hernández, R.; Canales-Islas, E.I. Evaluation of the Impact of Climate Change on the Water Balance of the Mixteco River Basin with the SWAT Model. Hydrology 2024, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratelli, F.A.; Alves, M.A.B.; Borella, D.R.; Kraeski, A.; de Almeida, F.T.; Zolin, C.A.; Hoshide, A.K.; Souza, A.P. de Effects of Land Use on Soil Physical-Hydric Attributes in Two Watersheds in the Southern Amazon, Brazil. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, S.; Villegas, J.C.; Hoyos, N.; Duque-Villegas, M.; Salazar, J.F. Streamflow Response to Land Use/Land Cover Change in the Tropical Andes Using Multiple SWAT Model Variants. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 54, 101888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, K.; Rau, P.; Montesinos, C.; Lavado-Casimiro, W.; Bourrel, L.; Frappart, F. Hydrological Response Assessment of Land Cover Change in a Peruvian Amazonian Basin Impacted by Deforestation Using the SWAT Model. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.; Ortiz, P.E.Z.; Fern, P.; Aracil, N. Seguridad Hídrica; Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú: Lima, Peru, 2023.

- Tinoco, Y.; Huarhua, D. Impacto del Cambio Climático en la Oferta Hídrica Superficial de la Cuenca del Río Piura; Universidad Nacional Agraria la Molina: La Molina, Peru, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Fernandez, A.S.; Cotrina-Sanchez, A.; Salas López, R.; Zabaleta-Santisteban, J.A.; Rios, N.; Medina-Medina, A.J.; Tuesta-Trauco, K.M.; Sánchez-Vega, J.A.; Silva-Melendez, T.B.; Oliva-Cruz, M.; et al. Spatiotemporal Land Cover Change and Future Hydrological Impacts Under Climate Scenarios in the Amazonian Andes: A Case Study of the Utcubamba River Basin. Land 2025, 14, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Fernández, D.; López, R.S.; Zabaleta-Santisteban, J.A.; Medina-Medina, A.J.; Goñas, M.; Silva-López, J.O.; Oliva-Cruz, M.; Rojas-Briceño, N.B. Landsat Images and GIS Techniques as Key Tools for Historical Analysis of Landscape Change and Fragmentation. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organizacion de las Naciones Unidas Objetivos del Desarrollo Sostenible. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/water-and-sanitation/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo Objetivo 6: Agua Limpia y Saneamiento|PNUD. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/es/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-6-clean-water-and-sanitation.html (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Moran, M. Agua y Saneamiento—Desarrollo Sostenible. Desarrollo Sostenible. Organ. Nac. Unidas 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Baca, L.C.; Achung, F.R.; Castillo, W.G.; Huayán, C.F.; Reátegui Reátegui, F.; Escobedo Torres, R.; Ramírez Barco, J.; Encarnación, F.; Maco García, J.; Limachi Huallpa, L.; et al. Propuesta de Zonificación Ecológica y Economica Del Departamento de Amazonas. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, W.F.C. Geomorfología. Estud. Temáticos Zoonificación Ecol. Econ. Dep. Amaz. 2014, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, A.J.M.; López, R.S.; Santisteban, J.A.Z.; Trauco, K.M.T.; Cayo, E.Y.T.; Haro, N.H.; Cruz, M.O.; Fernández, D.G. An Analysis of the Rice-Cultivation Dynamics in the Lower Utcubamba River Basin Using SAR and Optical Imagery in Google Earth Engine (GEE). Agronomy 2024, 14, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaman Haro, N.; Lopezhaya Mendoza, J.B.; Medina Medina, A.J.; Zabaleta Santisteban, J.A.; Tineo Flores, D.; Juarez-Contreras, L.; Goñas, M.; Oliva-Cruz, M. Agronomic and Economic Evaluation of Tree Species in Agroforestry Systems with Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) in Amazonas. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional De Estadística E Informática (INEI). Censos Nacionales 2017: XII Población, VII Vivienda y III Comunidades IndÍgenas. Available online: https://censos2017.inei.gob.pe/redatam/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- INEI Perú. Estimaciones y Proyecciones de Población Por Departamento, Provincia y Distrito, 2018–2020. INEI 2017, 1–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez Barco, J.M. Uso Actual de La Tierra, Informe Temático. Proyecto de Zonificación Ecologica y Economica Del Departamento de Amazonas. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2010, 3, 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- López, S.; Omar, J. Análisis de la Degradación de Pastizales Basado en Imágenes Multiespectrales Uas-Microcuencas Pomacochas y Ventilla, Amazonas Peru; Escuela de Posgrado de la Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas: Amazonas, Peru, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonía Peruana (IIAP); Gobierno Regional de Amazonas (GOREA). Zonificación Ecológica y Económica Del Departamento de Amazonas. Zoonificacion Ecol. Econ. Amaz. 2016, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, A.C.; Salazar, A.; Oviedo, C.; Bandopadhyay, S.; Mondaca, P.; Valentini, R.; Briceño, N.B.R.; Guzmán, C.T.; Oliva, M.; Guzman, B.K.; et al. Integrated Cloud Computing and Cost Effective Modelling to Delineate the Ecological Corridors for Spectacled Bears (Tremarctos ornatus) in the Rural Territories of the Peruvian Amazon. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 36, e02126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, H.V.; Huamán Puscán, M.M.; Bobadilla, L.G.; Zagaceta, H.; Valqui, L.; Maicelo, J.L.; Silva-López, J.O. Evaluation of Pasture Degradation through Vegetation Indices of the Main Livestock Micro-Watersheds in the Amazon Region (NW Peru). Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 20, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SENHAMI. SENAMHI—Estaciones. Available online: https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?p=estaciones (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, E.; Turpo, E.Y.; Tariq, A.; Salas López, R.; Pizarro, S.; Zabaleta-Santisteban, J.A.; Medina-Medina, A.J.; Tuesta-Trauco, K.M.; Oliva-Cruz, M.; Vásquez, H.V. Spatial Distribution of Burned Areas from 1986 to 2023 Using Cloud Computing: A Case Study in Amazonas (Peru). Fire 2024, 7, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAPBIOMAS MapBiomas Perú. Available online: https://peru.mapbiomas.org/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Arce-Inga, M.; Atalaya-Marin, N.; Barboza, E.; Tarrillo, E.; Chuquibala-Checan, B.; Tineo, D.; Fernandez-Zarate, F.H.; Cruz-Luis, J.; Goñas, M.; Gómez-Fernández, D. Multicriteria Evaluation and Remote Sensing Approach to Identifying Degraded Soil Areas in Northwest Peru. Geocarto Int. 2025, 40, 2443235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAPBIOMAS PERU. Cobertura y Uso de Suelo. Doc. Base Teor. Sobre Algorithm 2025, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro, S.; Requena-Rojas, E.; Barboza, E.; Peña-Elme, E.; Arias-Arredondo, A.; Ccopi, D. Ecological and Carcinogenic Risk Assessment of Potentially Toxic Elements in Rangelands and Croplands around Lake Junin (Peru): Integrating Remote Sensing, Machine Learning, and Land Cover Segmentation. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 999, 180327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayo, E.Y.T.; Borja, M.O.; Espinoza-Villar, R.; Moreno, N.; Camargo, R.; Almeida, C.; Hopfgartner, K.; Yarleque, C.; Souza, C.M. Mapping Three Decades of Changes in the Tropical Andean Glaciers Using Landsat Data Processed in the Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.E.; Warner, T.A.; Fang, F. Implementation of Machine-Learning Classification in Remote Sensing: An Applied Review. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 2784–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, E.; Barboza, E.; Rojas-Briceño, N.B.; Cotrina-Sanchez, A.; Valdés-Velásquez, A.; de la Lama, R.L.; Llerena-Cayo, C.; de la Puente, S. Modeling and Predicting Land Use and Land Cover Changes Using Remote Sensing in Tropical Coastal Ecosystems of Southern Peru. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, S.E.; Pricope, N.G.; Vargas-Machuca, D.; Huanca, O.; Ñaupari, J. Mapping Land Cover Types for Highland Andean Ecosystems in Peru Using Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asurza-Véliz, F.A.; Lavado-Casimiro, W.S. Regional Parameter Estimation of the SWAT Model: Methodology and Application to River Basins in the Peruvian Pacific Drainage. Water 2020, 12, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Marquez, R.; Vera-Vílchez, J.; Verástegui-Martínez, P.; Lastra, S.; Solórzano-Acosta, R. An Evaluation of Dryland Ulluco Cultivation Yields in the Face of Climate Change Scenarios in the Central Andes of Peru by Using the AquaCrop Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISRIC. Soil Grids. Available online: https://www.isric.org/explore/soilgrids (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- QGIS. Espacial Sin Concesiones. Available online: https://qgis.org/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- PISCO SENAMHI HSR PISCO. Available online: https://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu/SOURCES/.SENAMHI/.HSR/.PISCO/index.html?Set-Language=es (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Huerta, A.; Aybar, C.; Imfeld, N.; Correa, K.; Felipe-Obando, O.; Rau, P.; Drenkhan, F.; Lavado-Casimiro, W. High-Resolution Grids of Daily Air Temperature for Peru—The New PISCOt v1.2 Dataset. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachac-Huerta, Y.; Lavado-Casimiro, W.; Zapana, M.; Peña, R. Understanding Spatio-Temporal Hydrological Dynamics Using SWAT: A Case Study in the Pativilca Basin. Hydrology 2024, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autoridad Nacional del Agua. Diagnostico Sobre Los Caudales Ecológicos En El Peru(Primera Fase). III Foro Int. Leche 2022, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- ANA Autoridad Nacional del Agua. Plataforma del Estado Peruano. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/ana (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Kibii, J.K.; Kipkorir, E.C.; Kosgei, J.R. Application of Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) to Evaluate the Impact of Land Use and Climate Variability on the Kaptagat Catchment River Discharge. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznarez, C.; Jimeno-Sáez, P.; López-Ballesteros, A.; Pacheco, J.P.; Senent-Aparicio, J. Analysing the Impact of Climate Change on Hydrological Ecosystem Services in Laguna Del Sauce (Uruguay) Using the Swat Model and Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Himanshu, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Singh, R. Evaluation of the SWAT Model for Analysing the Water Balance Components for the Upper Sabarmati Basin. In Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 39, pp. 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Neitsch, S.L.; Arnold, J.G.; Kiniry, J.R.; Williams, J.R. Soil and Water Assessment Tool Theoretical Documentation; Grassland, Soil and Water Research Laboratory: Temple, TX, USA, 2005.

- Lins, F.A.C.; de Assunção Montenegro, A.A.; de Andrade Farias, C.W.L.; da Silva, M.V.; de Souza, W.M.; de Albuquerque Moura, G.B.; da Silva, T.G.F.; Montenegro, S.M.G.L. Soil Moisture and Hydrological Processes Dynamics under Climate and Land Use Changes in a Semiarid Experimental Basin, Brazil. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2024, 24, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.C.A.; Santos, R.M.B.; Fernandes, L.F.S.; Carvalho de Melo, M.; Valera, C.A.; do Valle, R.F., Jr.; de Melo Silva, M.M.A.P.; Pacheco, F.A.L.; Pissarra, T.C.T. Hydrologic Response to Land Use and Land Cover Change Scenarios: An Example from the Paraopeba River Basin Based on the SWAT Model. Water 2023, 15, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, K.C.; Vaghefi, S.A.; Srinivasan, R. A Guideline for Successful Calibration and Uncertainty Analysis for Soil and Water Assessment: A Review of Papers from the 2016 International SWAT Conference. Water 2017, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niraula, R.; Norman, L.M.; Meixner, T.; Callegary, J.B. Multi-Gauge Calibration for Modeling the Semi-Arid Santa Cruz Watershed in Arizona-Mexico Border Area Using SWAT. Air Soil Water Res. 2012, 5, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, R.; Ashraf, A.; Van der Tol, C.; Aziz, F. Modeling Hydrological Response to Land Use/Cover Change: Case Study of Chirah Watershed (Soan River), Pakistan. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Niyazi, B.; Elfeki, A.M.; Masoud, M.; Wang, X.; Awais, M. SWAT-Driven Exploration of Runoff Dynamics in Hyper-Arid Region, Saudi Arabia: Implications for Hydrological Understanding. Water 2024, 16, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari-Sharabian, M.; Taheriyoun, M.; Karakouzian, M. Sensitivity Analysis of the DEM Resolution and Effective Parameters of Runoff Yield in the SWAT Model: A Case Study. J. Water Supply Res. Technol. 2020, 69, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghel, S.; Kothari, M.K.; Tripathi, M.P.; Singh, P.K.; Bhakar, S.R.; Dave, V.; Jain, S.K. Spatiotemporal LULC Change Detection and Future Prediction for the Mand Catchment Using MOLUSCE Tool. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Singh, R.M. Spatio-Temporal Analysis and Prediction of Land Use and Land Cover in Jagdalpur Sub-Division of Bastar District in State of Chhattisgarh, India from 2012 to 2037. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. A 2025, 106, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRA; IIAP. Zonificación Ecológica y Económica (ZEE) del Departamento de Amazonas; GRA: Iquitos, Perú; IIAP: Iquitos, Perú, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Touseef, M.; Chen, L.; Masud, T.; Khan, A.; Yang, K.; Shahzad, A.; Ijaz, M.W.; Wang, Y. Assessment of the Future Climate Change Projections on Streamflow Hydrology and Water Availability over Upper Xijiang River Basin, China. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündüz, H.İ. Land-Use Land-Cover Dynamics and Future Projections Using GEE, ML, and QGIS-MOLUSCE: A Case Study in Manisa. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjab, S.; Tanweer Abbas, P.; Shoaib, M.; Albano, R.; Azhar Inam Baig, M.; Ali, I.; Umar Farid, H.; Usman Ali, M. Artificial-Intelligence-Based Investigation on Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) Changes in Response to Population Growth in South Punjab, Pakistan. Land 2025, 14, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, N.Q.; Khayyun, T. Spatiotemporal Prediction of Future LULC Changes, Northern and Northeastern Parts of Iraq with MOLUSCE. Artic. J. Ecohum. 2024, 3, 2417–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego (MIDAGRI). Visor GEOSERFOR. Available online: https://geo.serfor.gob.pe/visor/ (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Medina-Medina, A.J.; Pizarro, S.; Tuesta-Trauco, K.M.; Zabaleta-Santisteban, J.A.; Rivera-Fernandez, A.S.; Silva-López, J.O.; Salas López, R.; Terrones Murga, R.E.; Sánchez-Vega, J.A.; Silva-Melendez, T.B.; et al. Integrating UAV LiDAR and Multispectral Data for Aboveground Biomass Estimation in High-Andean Pastures of Northeastern Peru. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh Noi, P.; Kappas, M. Comparison of Random Forest, k-Nearest Neighbor, and Support Vector Machine Classifiers for Land Cover Classification Using Sentinel-2 Imagery. Sensors 2017, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriquez-Dole, L.E.; Gironás, J.; Meza, F.; Salazar, E.; Henríquez, C. Landscape Metrics Selection and Influence over Hydrological Signatures: Land Use Change’s Effect over Water Resources in Chile. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1569574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Veintimilla, D.; Ochoa-Cueva, P.; Arteaga-Marín, J. Evaluation of the Hydrological Response to Land Use Change Scenarios in Urban and Non-Urban Mountain Basins in Ecuador. Land 2024, 13, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, D.; Cacciuttolo, C.; Custodio, M.; Nosetto, M. Effects of Grassland Afforestation on Water Yield in Basins of Uruguay: A Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Historical Trends Using Remote Sensing and Field Measurements. Land 2023, 12, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Silveira, L.; Vervoort, R.W. Assessing Effects of Afforestation on Streamflow in Uruguay: From Small to Large Basins. Hydrol. Process. 2024, 38, e15272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Ellison, D.; Ferraz, S.; Lara, A.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Z. Forest Restoration and Hydrology. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 520, 120342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, H.; Kalin, L.; Sun, G.; Kumar, S. Understanding the Effects of Afforestation on Water Quantity and Quality at Watershed Scale by Considering the Influences of Tree Species and Local Moisture Recycling. J. Hydrol. 2024, 640, 131739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, F.M.; de Oliveira, R.P.; Di Lollo, J.A. Effects of Land Use Changes on Streamflow and Sediment Yield in Atibaia River Basin-SP, Brazil. Water 2020, 12, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, M.; de Aguiar, T.R.; Mielke, M.S.; Rousseau, A.N.; Faria, D.; Mariano-Neto, E. Interactions Between Forest Cover and Watershed Hydrology: A Conceptual Meta-Analysis. Water 2024, 16, 3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Vásquez, M.; Tobón-Marin, C. Effects of Tropical Montane Forest Restoration on the Ecohydrological Functioning of Watersheds. BOSQUE 2023, 44, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katusiime, J.; Schütt, B. Integrated Water Resources Management Approaches to Improve Water Resources Governance. Water 2020, 12, 3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; George, R.; Barua, A. Socio-Hydrological Frameworks for Adaptive Governance: Addressing Climate Uncertainty in South Asia. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1556820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, C.F.; Espinoza, J.C.; Athayde, S.; Correa, S.B.; Couto, T.B.A.; Heilpern, S.A.; Jenkins, C.N.; Piland, N.C.; Utsunomiya, R.; Wongchuig, S.; et al. The Andes–Amazon–Atlantic Pathway: A Foundational Hydroclimate System for Social–Ecological System Sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2306229121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Berge, A.A.; Booij, M.J.; Rientjes, T.H.M. Robustness of Hydrological Models for Simulating Impacts of Climate Change on High and Low Streamflow. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 133734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, B.; Bhardwaj, A.; Sam, L. Cellular Automata Models for Simulation and Prediction of Urban Land Use Change: Development and Prospects. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 2025, 6, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletta, V.R.; Pagano, A.; Zimmermann, N.; Davies, M.; Butler, A.; Fratino, U.; Giordano, R.; Pluchinotta, I. Socio-Hydrological Modelling Using Participatory System Dynamics Modelling for Enhancing Urban Flood Resilience through Blue-Green Infrastructure. J. Hydrol. 2024, 636, 131248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.