Abstract

Study region: This study focused on the Iznik Lake Watershed in northwestern Türkiye. Study focus: Climate change is increasingly affecting water resources worldwide, raising concerns about future hydrological sustainability. This study investigates the impacts of climate change on river streamflow in the Iznik Lake Watershed, a critical freshwater resource in northwestern Türkiye. To capture possible future conditions, downscaled climate projections were integrated with the SWAT+ hydrological model. Recognizing the inherent uncertainties in climate models and model parameterization, the analysis examined the relative influence of climate realizations, emission scenarios, and hydrological parameters on streamflow outputs. By quantifying both the magnitude of climate-induced changes and the contribution of different sources of uncertainty, the study provides insights that can guide decision-makers in future management planning and be useful for forthcoming modeling efforts. New hydrological insights for the region: Projections indicate wetter winters and springs but drier summers, with an overall warming trend in the study area. Based on simulations driven by four representative grid points, the results at the Karadere station, which represents the main inflow of the watershed, indicate modest changes in mean annual streamflow, ranging from −7% to +56% in the near future and from +19% to +54% in the far future. Maximum flows (Qmax) exhibit notable increases, ranging from +0.9% to +47% in the near future and from +21% to +63% in the far future, indicating a tendency toward higher peak discharges under future climate conditions. Low-flow conditions, especially in summer, exhibit the greatest relative variability due to near-zero baseline discharges. Relative change analysis revealed considerable differences in Karadere and Findicak sub-catchments, reflecting heterogeneous hydrological responses even within the same basin. Uncertainty analysis, conducted using both an ANOVA-based approach and Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA), highlighted the dominant influence of climate projections and potential evapotranspiration calculation methods, while land use change contributed negligibly to overall uncertainty.

1. Introduction

Water is an indispensable resource for our planet, and its sustainable management and protection are essential to ensure long-term availability for future generations. However, water resources are highly sensitive to climatic change, as alterations in precipitation, evapotranspiration rates, and temperature regimes directly influence their quantity and spatial distribution [1,2]. According to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [3], global temperatures are likely to rise by around 1.5 °C during 2021–2040 under most scenarios, and each additional increment of warming is expected to intensify multiple and simultaneous hazards. These projections highlight the urgent need to promptly and consistently reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Numerous studies have documented how climate change influences the hydrologic cycle, demonstrating alterations in streamflow patterns, reductions in water availability, and intensifying extremes like floods and droughts [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Given these risks, detailed hydrological studies are essential to enhance our knowledge of how climate change impacts streamflow and water balance.

Hydrological models are critical tools for understanding, predicting, and managing water resources [10], as they provide scientific support for analyzing water resource-related problems and aid in developing strategies for sustainable water management. The SWAT model and its enhanced version, Soil and Water Assessment Tool-Plus (SWAT+), are extensively used hydrological models designed to predict the impacts of land use, land cover changes, and climate change on water resources across large and complex watersheds [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Although fewer in number compared to those employing the original SWAT, several recent works have used SWAT+ to assess the effects of climate at the river basin scale [17,18,19,20,21,22]. There are also studies that applied the SWAT model to Türkiye’s water resources [23,24,25,26,27,28], while applications of the SWAT+ model remain very limited [29,30]. Collectively, these studies highlight the growing relevance and versatility of SWAT+ in evaluating climate change impacts on watershed hydrology.

Due to population growth, industrial development, and agricultural activities, Türkiye experiences significant water stress, making it highly sensitive to climate change, especially in areas such as the Iznik Lake Watershed in the Marmara Region [31,32]. The Iznik Lake Watershed is of vital importance as it integrates hydrological, ecological, and socio-economic functions, sustaining aquatic biodiversity, local fisheries, and the communities that depend on them. The basin supports diverse agricultural production, including olives, vineyards, fruit orchards, and vegetables, all of which benefit from the favorable microclimate and irrigation opportunities provided by the lake and its tributaries. Recognizing its environmental value, the watershed has been designated as a natural protected area since 1990. Nevertheless, situated within the Mediterranean climate belt, the watershed faces growing risks of droughts and altered runoff regimes. Lake Iznik, the largest in the Marmara Region and the fifth-largest freshwater lake in Türkiye, has already experienced substantial water level reductions and pollution in recent years, mainly due to the combined impacts of climate change and anthropogenic pressures [33,34]. Declining lake levels, increasing reliance on pumping irrigation, and expanding industrial activities, particularly in the western basin, exacerbate water stress, raising concerns about long-term water availability and ecosystem sustainability. These challenges underline the need for a comprehensive understanding of the watershed’s hydrological dynamics under climate change conditions.

A wide range of research has examined different aspects of the Iznik Lake Watershed. Geological investigations have provided insights into the lake’s characteristics [35,36,37], while other studies have assessed water quality [38], pollution sources [34,39], and the influence of natural conditions and land use on basin management and planning [40,41]. Hydrological modeling has also been applied: WEAP model-based simulations showed that reliable water budget estimates can be obtained when both climate data and spring flows are incorporated into calibration [42]. Also, SWAT+ applications demonstrated the effect of land use and land cover changes on water balance components in the basin [43].

Despite these contributions, the potential impacts of climate change on streamflow have not yet been investigated in the Lake Watershed. Furthermore, comprehensive uncertainty analyses through hydrological modeling are very limited in climate change impact research, both in Türkiye [44] and internationally [45]. As one of the pioneer studies in this field, the present research applies an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)-based uncertainty analysis to the Iznik Lake Watershed, representing a gap in understanding regional hydrological responses to future climate conditions.

To address these gaps, the present study aims to (i) establish a calibrated SWAT+ model for the Iznik Lake Watershed to support future research; (ii) evaluate the effects of climate change on streamflow; (iii) quantify the relative changes in streamflow arising from different climate projection datasets; and (iv) assess the uncertainty contributions of model parameters and climate projections to overall streamflow uncertainty. By achieving these objectives, the study seeks to provide novel insights to advance scientific understanding and to inform sustainable water management strategies under changing climate conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

In the present study, particular attention was given to ensuring that the model setup accurately represents the hydrological processes of the Iznik Lake Watershed. The model was configured to capture the basin’s diverse topography, soil types, and land-use patterns, while also reflecting key hydrological drivers such as precipitation, and seasonal streamflow variability. This watershed-specific parameterization was essential for reproducing realistic water balance dynamics and for generating reliable future projections under climate change scenarios.

2.1. Study Area

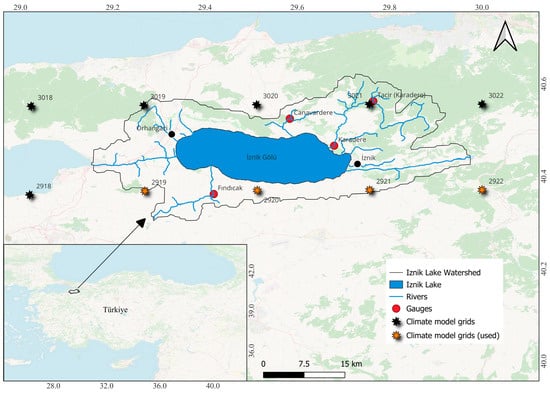

The Iznik Lake Watershed is located in the Marmara Region of northwestern Türkiye (Figure 1). The watershed spans from 40°20′ to 40°35′ N latitude and 29°10′ to 29°55′ E longitude, covering an area of 1400 km2. Iznik Lake, a tectonic freshwater body, has a surface area of 313 km2, an average depth of 40 m and a maximum depth of 80 m [37,38]. It is the largest in the Marmara Region and the fifth largest natural lake in Türkiye. The basin elevation varies from sea level up to approximately 1300 m, significantly influencing the spatial distribution of temperature and precipitation across the watershed. The climate is typically Mediterranean, characterized by hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters, with a mean annual temperature of 15.1 °C and an average annual precipitation of about 630 mm [41]. The major soil types within the watershed include brown forest soils, red brown Mediterranean soils, rendzina, alluvial, and colluvial deposits. The predominant land use/land cover types in the watershed are agricultural areas, forests, bushlands, and grasslands. Other land cover types include residential zones, transportation and mining areas, commercial and industrial regions, and wetlands.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area including the meteorological station, gauges, rivers, and the grid points of the climate models.

The lake is primarily fed by Findicak (Sölöz), Olukdere, Kırandere, and Karasu (Karadere) streams, with outflow through the Karsak Stream to the Marmara Sea. Among these, Karadere is the largest, draining a basin of 273 km2 with an average discharge of 2.4 m3/s, while Sölöz Stream has a drainage area of 92 km2 and a mean flow of 1.06 m3/s [39,43]. Despite numerous tributaries in the basin, most are short and seasonal.

2.2. Input Data

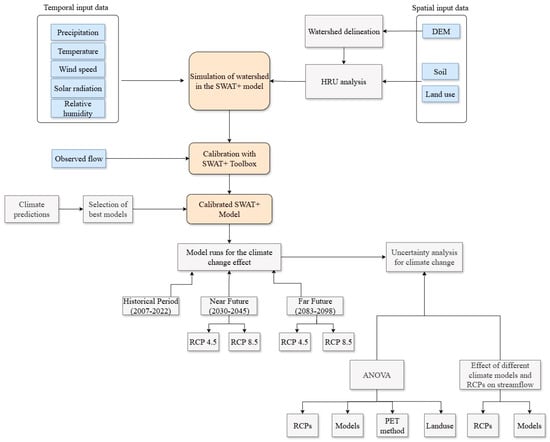

The SWAT+ model requires a wide range of spatial and temporal datasets to simulate hydrological processes within a watershed. The spatial datasets include the Digital Elevation Model (DEM), land use/land cover (LULC) data, and soil data. Temporal inputs consist of precipitation, air temperature (maximum and minimum), relative humidity, solar radiation, and wind speed. High-resolution and high-quality input data are crucial, since inaccuracies may introduce significant uncertainty into model outputs [46]. Furthermore, observed streamflow data are required for model calibration and validation. For the Iznik Lake Watershed, multiple data sources were utilized, and details of the input datasets are provided in the following subsections.

2.2.1. DEM Data

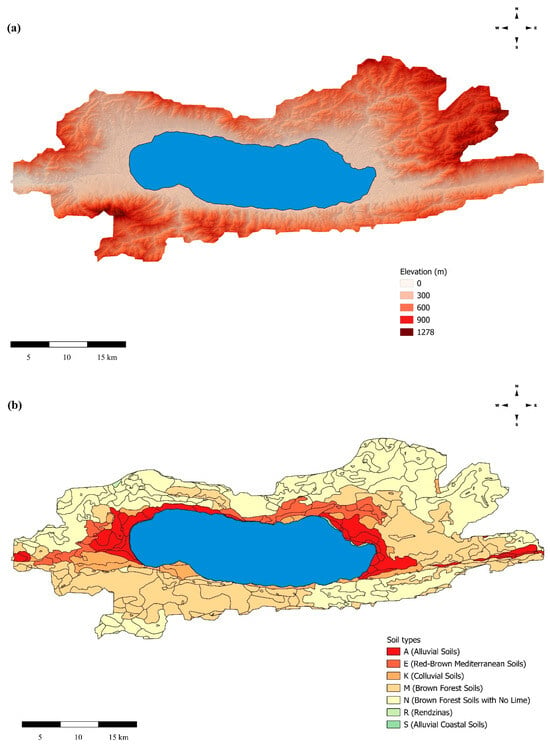

A digital elevation model is the key geographical input for the SWAT+ model as it directly affects the delineation of the watershed, which in turn governs surface runoff, flow direction, and stream networks. In this study, we used the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM 1 Arc-Second Global) dataset, with a spatial resolution of ~30 × 30 m, covering the entire basin (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov (accessed on 1 July 2025)). The DEM also supports the computation of hydrologically relevant parameters such as flow accumulation, channel length, and channel width, which are crucial for modeling the hydrological response of the catchment. The DEM map of the study area is shown in Figure 2a.

Figure 2.

(a) DEM map of the study area, (b) Soil map of the study area.

2.2.2. Soil Data

Soil properties represent a vital component of the SWAT+ model in regulating infiltration, surface runoff, and other hydrological responses. The analysis relied on the Major Soil Groups (BTG) map (scale 1:100,000), originally produced by the General Directorate of Rural Services of Türkiye in the 1970s and subsequently updated. Since the SWAT+ model requires a detailed soil look up table and user soil tables, the necessary soil properties were derived from the regional soil analyses carried out in the Bursa region [47]. The soil distribution in the Iznik Lake Watershed was classified according to the BTG maps (Figure 2b).

2.2.3. Land Use/Land Cover Data

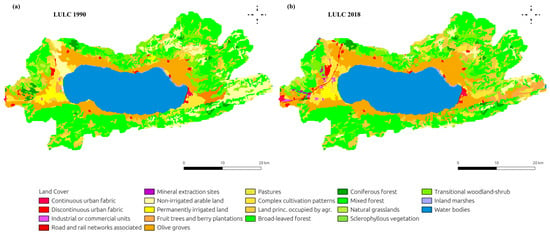

Simulating hydrological parameters in the watershed also requires reliable land use/land cover (LULC) data. LULC data provides information on the distribution of different land cover types, such as urban areas, forests, and agricultural land, which directly influence runoff generation and evapotranspiration processes. By integrating LULC data with DEM data, more accurate hydrological models can be developed to assess the potential impacts of LULC changes on water resources in the watershed. The present study selected the Coordination of Information on the Environment (CORINE) Land Cover datasets for the years 1990 and 2018 (https://land.copernicus.eu/pan-european/corine-land-cover ((accessed on 1 July 2025)). The datasets, available in both raster and vector formats with a resolution of 100 m, enabled the representation of land use dynamics across the watershed. Figure 3 presents the spatial distribution of land use/land cover (LULC) across the watershed for 1990 and 2018.

Figure 3.

Land use and land cover (LULC) maps of the Iznik Lake Watershed. (a) LULC map of 1990 (b) LULC map of 2018.

2.2.4. Meteorological Data

Climatic variables constitute another crucial input to ensure realistic simulation of the water balance in the SWAT+ model. For this study, daily observed meteorological data including precipitation, maximum and minimum air temperatures, and relative humidity were provided by the General Directorate of Meteorology (MGM). The location of the Iznik meteorology station is shown in Figure 1. The wind speed and solar radiation data were obtained from The National Aeronautics and Space Administration- Prediction of Worldwide Energy Resource (NASA-POWER) (https://power.larc.nasa.gov ((accessed on 1 July 2025)).

2.2.5. Observed Streamflow Data

Streamflow data is essential to calibrate and validate the model. In this study, flow data from two gauge stations operated by the General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works (DSI) were used. The names of the stations are Karadere (Station ID: D02A031), and Findicak (station ID: E02A016). These two stations were also used as the historical baseline to investigate the potential impacts of climate change on streamflow.

2.3. The SWAT+ Model

In this study, the SWAT+ model [46] was chosen for its ability to simulate the complex interactions between land use, soil, and climate in watershed systems. This model has been widely used in hydrological research to evaluate water resources and to explore future scenarios under varying climatic and land-use conditions. It is an open-source model and represents a restructured and expanded version of the original SWAT model [48,49]. Compared to the original SWAT model, SWAT+ provides a more flexible and modular object-based spatial structure. The model’s flexible structure allows watershed to be divided into hydrologic response units (HRUs) based on unique combinations of land use, soil type, and slope. These enhancements enable SWAT+ to better capture the complexities of watershed systems and provide more reliable predictions for water quantity and quality. Additionally, SWAT+ includes new features such as improved snowmelt and groundwater modules, making it a valuable tool for water resource management and planning. By incorporating these advancements, SWAT+ offers a comprehensive solution for addressing various water management challenges in a watershed context. By applying the water balance equation to each HRU, the model simulates the hydrological cycle as follows: within the watershed:

where SWt is the final soil water content (mm H2O); SW0 is the initial soil water content on day i (mm H2O); Rday is the amount of precipitation on day i (mm H2O); Qsurf is the amount of surface runoff on day i (mm H2O); Ea is the amount of evapotranspiration on day i (mm H2O); wseep is the amount of water entering the vadose zone from the soil profile on day i (mm H2O); Qgw is the amount of return flow on day i (mm H2O), t is time in days [50].

The SWAT+ model operates on the Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS) interface, which we used version QGIS 3.40 Bratislava long-term release. The overall methodology of this study comprised data collection, model setup, calibration and validation, climate change scenario analysis, and the impact of climate change on streamflow (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Workflow of the SWAT+ model for climate change impact assessment.

2.4. Model Performance Tools

Calibration and validation are vital steps in hydrological modeling to ensure that the model accurately represents the hydrological processes within the watershed. The calibration process involves adjusting model parameters to minimize the difference between observed and simulated streamflow data, whereas validation evaluates the model’s performance with independent data that were not used in calibration. For this study, observed monthly streamflow data from two gauging stations operated by DSI were employed. Specifically, streamflow records from the Karadere and Findicak stations were selected for model calibration and validation (Figure 1).

The SWAT+ Toolbox version 2.4 was utilized for sensitivity analysis, calibration, and validation processes [51]. For sensitivity analysis, the Latin Hypercube-One Factor at a Time (LHS-OAT) sampling method was employed to identify the sensitive parameters affecting streamflow, while the Calibration by Latin-hypercube Sampling Iterations (CALSI) algorithm was used for automatic calibration. The main parameters considered in the sensitivity analysis and calibration include CN2 (SCS curve number), Z (soil layer depth), ESCO (soil evaporation compensation factor), CN3_SWF (pothole evaporation coefficient), AWC (available water capacity of soil layer), SLOPE (average HRU slope), K (saturated hydraulic conductivity), BD (bulk density), LAT_LEN (slope length for lateral flow), CLAY (soil clay content), and CANMX (maximum canopy storage).

Four statistical criteria, Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE), Kling-Gupta efficiency (KGE), percent bias (PBIAS), and coefficient of determination (R2), were used to evaluate the model’s performance. NSE is a widely used parameter to evaluate how well the model predicted the observed data. KGE is a complementary criterion to NSE, including correlation, variability, and bias in its formula. PBIAS is a useful indicator for assessing whether the model systematically overestimated or underestimated the observed data. Lastly, R2 quantifies the proportion of variance in the observed data explained by the model, serving as a measure of goodness-of-fit. According to the commonly adopted thresholds in hydrological modeling studies [52,53,54,55], NSE, KGE, and R2 values above 0.50 are generally considered satisfactory, and as they approach 1.0, the model performance is regarded as very good. For PBIAS, values within the range of ±25% are classified as satisfactory, while values closer to zero indicate very good performance.

2.5. Climate Projections

In this study, climate projection data for the Iznik Lake Watershed were derived from the outputs of three global circulation models (HadGEM2-ES, MPI-ESM-MR, and GFDL-ESM2M) under two Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP4.5 and RCP8.5). Developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), these RCPs represent alternative climate futures based on varying greenhouse gas concentrations. RCP4.5 reflects a stabilization scenario, where emissions peak around the mid-21st century and then decline, leading to stabilization of radiative forcing at approximately 4.5 W/m2 by 2100. In contrast, RCP8.5 represents a high-emission trajectory in which greenhouse gas concentrations continue to increase throughout the century, reaching about 8.5 W/m2 by 2100.

The climate projections, provided by the General Directorate of Meteorology (MGM), were dynamically downscaled to a 20 km resolution domain using the Regional Climate Model RegCM4.3.4, for the period 2015–2099 [56,57]. The data were produced within the national project “Climate Projections with New Scenarios for Turkey”, a program dedicated to providing downscaled climate scenarios tailored to different regions of country. The one-way nesting method was employed to dynamically downscale the GCMs for the study domain. Following the configuration described by [57], the HadGEM2-ES global climate model, allowed direct dynamic downscaling to a horizontal resolution of 20 km using RegCM. In contrast, the MPI-ESM-MR and GFDL-ESM2M models required a two-step downscaling procedure, in which the simulations were first dynamically downscaled to 50 km and subsequently refined to 20 km. The regional climate simulations were conducted over a domain with a 20 km horizontal resolution, comprising approximately 130 × 180 grid points and 18 vertical sigma levels. Sensitivity tests were performed by running the model for the reference period 1971–2000 and comparing the results with observational data sets [56,57]. In this study, a total of 10 grid points (Figure 1) were analyzed, and each grid point contains climate projection data from all three downscaled global circulation models under both RCP scenarios. The Regional Climate Model (RCM) outputs include daily minimum and maximum temperatures as well as daily precipitation, enabling a comprehensive assessment of potential climate change impacts on the basin.

First, the historical data from the Iznik meteorological station and the projected climate data were analyzed using NSE, R2, KGE, and PBIAS statistical metrics. The best-performing four grids were selected based on the performance rankings of the datasets. The selected RCMs were then used to construct ensemble projections. An initial bias-correction procedure was tested for dynamically downscaled climate projections. However, the applied correction did not lead to a noticeable improvement in the representation of peak precipitation events, which are critical for streamflow simulations in the study area. Therefore, the original dynamically downscaled climate data were used in the subsequent analyses. For reference, the baseline period was defined between 2007 and 2022, while future projections were assessed for 2030–2045 (near future) and 2083–2098 (far future).

2.6. Uncertainty Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the uncertainty in projected streamflow, two complementary approaches were applied. First, streamflow uncertainty was assessed by analyzing the outputs of the four climate projection datasets under the two emission scenarios (RCP4.5 and RCP8.5) relative to the baseline scenario. Instead of absolute flow variation, the analysis focused on the ranges of relative changes in streamflow. Specifically, monthly relative changes were examined to capture seasonal responses, and annual relative changes in Qmin, Qmax, and Qmean were quantified to highlight possible shifts in low flows, hydrological extremes, and mean conditions under different climate scenarios. This analysis provided an overview of the potential spread in flow projections.

In the second approach, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to partition the total variance in simulated streamflow into contributions from different sources of uncertainty. A total of 32 runs were conducted for each simulation period to quantify the contributions of different model structures and climate datasets to projected streamflow in the Karadere and Findicak rivers for the near future (2030–2045), and the far future (2083–2098). The simulations were based on two Potential Evapotranspiration (PET) estimation methods, land use (LU) data of the years 1990 and 2018, and eight forecast periods derived from two RCPs and four RCM datasets. These 2 × 2 × 2 × 4 combinations enabled us to systematically evaluate the uncertainty contribution of each factor and its interactions on the simulated streamflow (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the factors used in the ANOVA analysis.

For each run, we obtained monthly mean streamflow values. ANOVA was then applied to partition the total variance in simulated streamflow into contributions from the main effects (PET method, LU data, RCM datasets, and RCPs) as well as their second-order interactions (e.g., RCMs: RCP, PET: RCM). The contribution of each factor to the overall uncertainty was calculated as the ratio of its sum of squares to the total sum of squares:

where SSTotal is the total variance; qijkl is the simulated value of average streamflow; i represents the ith potential evapotranspiration (PET) algorithm; j represents the jth landuse data; k represents the kth RCM datasets; l represents the lth RCP; q0 represents the overall average of the simulated average flow; N represents the level number of this factor. SSTotal can be divided into ten parts representing the four main effects and six second-order interaction effects.

where SSPET, SSLU, SSRCM, SSRCP are the main effects from PET algorithms, LU algorithms, RCM datasets, and RCPs, respectively; SSPET.LU is uncertainty from interactions between the PET algorithms and LU algorithms. Similar calculations were conducted for the other second-order interaction terms [45]. The calculation formula for the variance components, such as SSPET, and SSPET.LU is given by:

where qi000 is the average of all simulated variables with the ith PET algorithm, q0j00 is the average of all simulated variables with the jth LU data, and qij00 is the average of all simulated variables with the ith PET algorithm and the jth LU algorithm. The remaining first and second-order effects were computed equivalently.

2.7. Bayesian Model Averaging

In addition to the uncertainty analysis, the probability of projected changes in Qmax and Qmean were analyzed using the Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) approach. While ANOVA quantifies the relative contribution of individual uncertainty sources to the variance of projected changes, BMA provides an integrated probabilistic estimate by combining multiple model simulations. In this method, higher weights are assigned to hydrological simulations driven by projected climate data that better reproduce historical precipitation. The weighted simulations are then used to derive posterior distributions of relative streamflow changes. These posterior distributions were approximated by normal distributions using the BMA-weighted mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ), and the corresponding probability density functions were used for visualization.

An ensemble of hydrological simulations obtained from the 2 × 2 × 2 × 4 combinations of PET calculation methods, land use scenarios, emission scenarios, and climate model grids were employed in the BMA analysis, consistent with the simulations used for ANOVA analysis. In Equation (6), y represents the projected streamflow metric (Qmax or Qmean), is the kth climate model grid used in the simulations, D is the observed precipitation time series used to evaluate the model performance. Accordingly, the probability distribution function of y, conditioned on the observational dataset D, is given by:

where represents the posterior probability (weight) of the kth climate model grid, determined by its ability to reproduce the observed precipitation, and represents the posterior distribution of the streamflow metric y obtained from the simulation driven by . Following previous studies, is assumed to follow a normal distribution [45]. The mean and standard deviation of the posterior distribution are calculated as:

where and are the mean and standard deviation of the posterior distribution, is the BMA weight of model , is the relative change in Qmax or Qmean, and K is the total number of simulations.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Performance Evaluation

The SWAT+ model was calibrated and validated using historical monthly streamflow data from Karadere and Findicak gauge stations. A sensitivity analysis was conducted before the calibration and validation processes. This analysis enabled us to identify the most influential parameters affecting streamflow, thereby reducing unnecessary computational effort and avoiding time loss during calibration. By focusing only on the parameters with the highest sensitivity, the calibration procedure could be carried out more efficiently, while parameters with negligible influence were excluded from further analysis. In line with previous studies, an initial sensitivity analysis was performed with a large number of parameters. Subsequently, a more targeted analysis was conducted by excluding the parameters that have zero sensitivity or very low sensitivity. As a result, a final set of 11 parameters with the highest sensitivity for our study area was selected and retained for the subsequent calibration and validation steps (Table 2). The definitions of these parameters are provided in Section 2.4.

Table 2.

Calibrated SWAT+ model parameters.

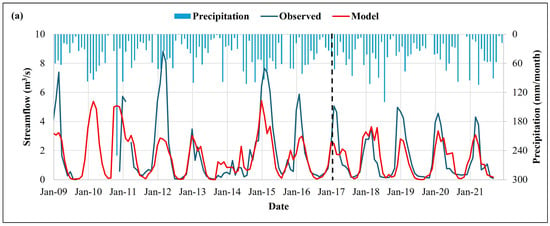

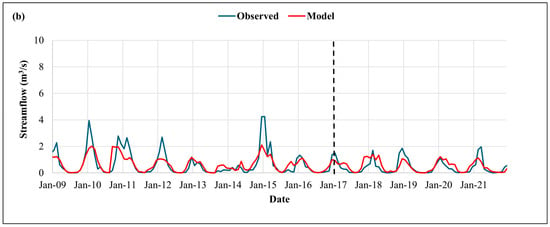

In the SWAT+ Toolbox, both automatic and manual calibration options are available to refine model parameters. In this study, we took advantage of both approaches: the automatic calibration procedure was initially used to provide an efficient parameter adjustment and identify an optimal starting point, while manual calibration was subsequently applied to fine-tune the parameters and further improve the agreement between observed and simulated streamflow. Manual calibration was performed by systematically increasing and decreasing the most sensitive parameters within predefined ranges based on the results of the automatic calibration. First, the parameters were added one by one to understand the individual effects of the parameters. Then, the parameters were progressively adjusted in combination, with each modification guided by the response of the simulated streamflow and the improvement in the performance metrics. The model simulations covered the period from 2007 to 2021, including a warm-up phase (2007–2009), a calibration phase (2010–2016), and a validation phase (2017–2021), applied to two streamflow gauges. These periods were selected to ensure sufficient data length for reliable parameter optimization and independent performance evaluation. NSE, KGE, R2, and PBIAS were evaluated to quantify the model performance. The performance statistics for both stations during calibration and validation are summarized in Table 3. In addition, Figure 5 shows the comparison between observed and simulated at the Karadere and Findicak gauge stations during the calibration and validation periods. The corresponding precipitation time series is shown in Figure 5a. At the Karadere station, the calibration period yielded satisfactory agreement between observed and simulated flows; however, the model tended to underestimate peak flows. During the validation period, the model maintained a comparable level of performance, indicating stable predictive ability across different time spans. The underestimation of peak flows in Karadere, especially in the years 2012 and 2015, may be related to the absence of correspondingly high precipitation data in the available rainfall data during these events. Notably, these peak discharges mostly occurred between February and April, suggesting that snowmelt processes could have played an important role in generating the observed high flows. Although SWAT+ includes a snowmelt module, the timing and magnitude of meltwater contributions might not have been fully captured for this watershed, leading to a mismatch between observed and simulated peaks. In addition, potential uncertainties in the observed streamflow records, such as occasional measurement errors or operational issues at the gauging station during high-flow conditions, may have also contributed to these discrepancies. For the Findicak station, calibration results showed relatively better performance, while validation statistics slightly decreased, indicating a tendency to overestimate flows. Overall, the model captured the temporal variability of streamflow well at both stations, but slightly underestimated high-flow peaks, similar to other studies [58].

Table 3.

Performance statistics of the SWAT+ model at the Karadere and Findicak gauge stations during the calibration and validation periods.

Figure 5.

Comparison of observed and simulated monthly streamflow at (a) Karadere and (b) Findicak gauge stations during the calibration and validation periods. The corresponding precipitation time series measured at the Iznik meteorological station is shown as bars in panel (a). The dotted vertical line indicates the boundary between the calibration and validation periods.

3.2. Selection of Climate Models

The historical data from the Iznik meteorological station and the dynamically downscaled climate projection data were analyzed using multiple performance criteria (NSE, R2, KGE, and PBIAS) at each grid point shown in Figure 1. The final performance ranking was based on the average of the KGE and R2 values, as these two metrics showed relatively satisfactory performance (closer to the 0.50 threshold) and better reflected the agreement between observed and simulated data. Specifically, a single performance score was calculated for each model by averaging the KGE and R2 values obtained separately for precipitation and temperature under both RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios. Although NSE and PBIAS were not used for ranking, they were still calculated to provide additional insight into the characteristics of each model. To improve readability, Table 4 and Table 5 present the results for four representative grid points, while the complete statistics for all grid points and models are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S1 and S2).

Table 4.

Performance statistics of precipitation and temperature variables from climate projection data (HadGEM2–ES, MPI–ESM–MR, and GFDL–ESM2M) under the RCP4.5 scenario at four selected grid points for the period 2015–2022. PBIAS values are expressed as percentages (%).

Table 5.

Performance statistics of precipitation and temperature variables from climate projection data (HadGEM2–ES, MPI–ESM–MR, and GFDL–ESM2M) under the RCP8.5 scenario at four selected grid points for the period 2015–2022. PBIAS values are expressed as percentages (%).

After analyzing the forecast data, the four best-performing models were selected based on the average weighted values of the models (Table 6). Since the temperature variables (minimum and maximum temperature) exhibited consistently high performance across all models (with R2 and KGE values generally above 0.9), they did not provide sufficient discriminatory power for model selection. Therefore, the ranking and selection of the best-performing models were carried out exclusively based on precipitation data, which showed greater variability in model performance. The analysis revealed that the climate model grids providing the best representation of observed precipitation and temperature at the Iznik meteorological station were associated with the HadGEM2-ES model. Specifically, the four grids (IDs 2019, 2920, 2921, and 2922) yielded the highest agreement with the observed records, with R2 values ranging from 0.41 to 0.51 for the near future and from 0.54 to 0.76 for the far future, and KGE values reaching up to 0.45 and 0.52, respectively. As also illustrated in Figure 1, these grids are located in proximity to the Iznik meteorological station, which further supports the reliability of the model outputs for this region. This spatial consistency between the station location and the best-performing model grids increases confidence in the use of these datasets for subsequent analyses. The primary sources considered for the uncertainty analysis included these four RCM datasets applied at different grid points within the study area. In the subsequent phase of the study, these data were used to assess the individual effects of each climate model on the model output and to perform an uncertainty analysis.

Table 6.

Performance evaluation of climate models, based on monthly precipitation under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios using R2 and KGE statistical metrics.

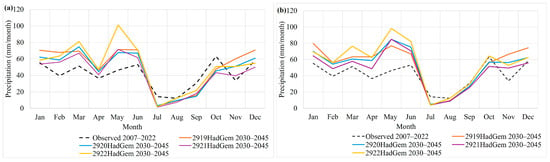

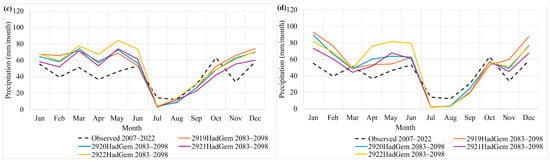

3.3. Projected Precipitation and Temperature Data

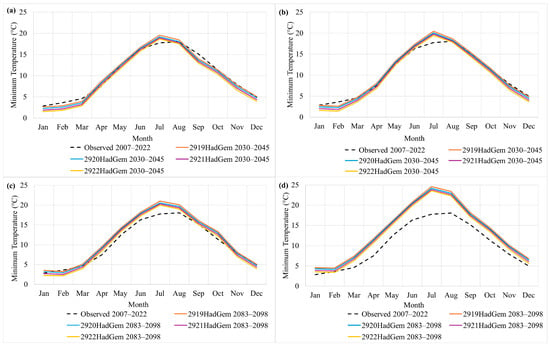

The precipitation and temperature projections for the four selected HadGEM2-ES grids (2019, 2920, 2921, and 2922), together with the observed baseline (2007–2022), are illustrated in Figure 6 and Figure 7. When compared with the baseline, precipitation projections (Figure 6) suggest an overall increase in rainfall during the winter and spring months, while a decrease is evident during the summer, particularly in July and August. This indicates a tendency toward wetter cold seasons and drier summers under future climate conditions, implying a stronger seasonal contrast in precipitation, similar to national projections reported by [57]. Temperature projections (Figure 7), on the other hand, show a clear warming trend for both the near-future (2030–2045) and far-future (2083–2098) periods relative to the baseline. Minimum temperatures show an overall increasing trend, though the magnitude of change varies seasonally, with the strongest warming projected during the summer months. These findings highlight that while precipitation changes exhibit both seasonal increases and decreases depending on the period, temperature projections reveal an overall warming trend across the study area, with particularly pronounced increases under the far-future RCP8.5 scenario.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the monthly total precipitation (mm/month) between the observed data and the climate model data (a) under RCP4.5 scenario between 2030–2045, (b) under RCP8.5 scenario between 2030–2045 (c) under RCP4.5 scenario between 2083–2098 (d) under RCP8.5 scenario between 2083–2098.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the monthly average minimum temperatures (°C) between the observed data and the climate model data (a) under RCP4.5 scenario between 2030–2045, (b) under RCP8.5 scenario between 2030–2045 (c) under RCP4.5 scenario between 2083–2098 (d) under RCP8.5 scenario between 2083–2098.

3.4. Streamflow Responses to Climate Change

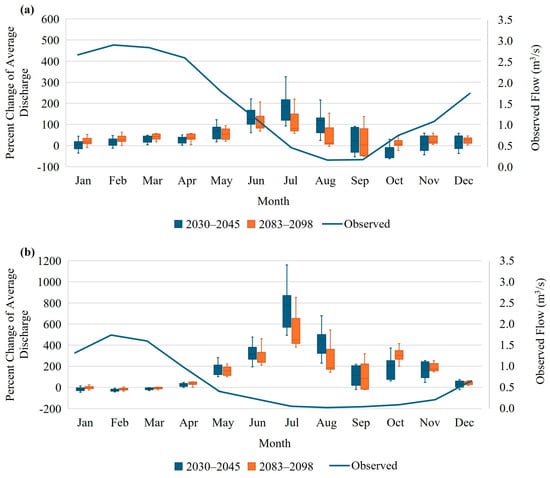

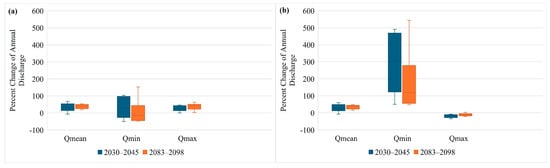

Following the evaluation of climate model performances, the next step of the analysis focused on investigating how projected climate changes may affect average streamflow in the study area. For each river (Karadere and Findicak), the distribution of relative changes was summarized separately for the near future (2030–2045) and far future (2083–2098), using four RCM datasets under two RCP scenarios. Box plots were generated to represent the spread of projected streamflow changes relative to the baseline period. The box plots thus provide a complementary view of the uncertainty range by directly visualizing the variability across models and scenarios and allow for a comparison of projected streamflow changes between the two rivers under different time horizons.

The results of the box plot analysis (Figure 8) demonstrated clear seasonal variations in projected streamflow responses. For both rivers, relative changes are generally modest during the winter and early spring months, remaining close to the baseline. In contrast, the summer period (June–September) exhibits the largest deviations. This large spread in the summer months is primarily attributable to the fact that streamflow during this period is very low, in some months approaching zero. Consequently, even small absolute differences among model outputs translate into large relative percentage changes. To highlight this effect, the baseline discharge values have been plotted on the same graph, providing context for interpreting the magnitude of the projected variations. In the Karadere station, the relative changes in streamflow range from −63% to 326% in the near future, while the far-future projections narrow to a range between −51% and 220%. This indicates that although considerable variability persists, the spread of projected changes becomes slightly smaller in the long term. In contrast, the Findicak River shows a much wider range of variability, with relative changes spanning from −44% to 1161% in the near future and from −35% to 854% in the far future. Similarly to Karadere, the uncertainty range narrows over the long term, but the magnitude of variation remains substantially larger in Findicak compared to Karadere. The extreme positive values in Findicak, such as the 1161% increase, occur during summer months when baseline flows are extremely low. In these cases, even small absolute changes result in disproportionately high percentage values. The greater spread observed in Findicak compared to Karadere can be attributed to the generally lower discharge levels at Findicak, as also illustrated in the flow series plotted alongside the box plots. When excluding the summer and early autumn months (June–September), the spread of relative streamflow changes becomes considerably narrower. In the Karadere River, the projected changes range from −63% to 122% in the near future and from −23% to 94% in the far future. This indicates a marked reduction in variability over the long term, reflecting less uncertainty in projected flows outside the low-flow season. In the Findicak River, however, the range of changes remains wider, spanning from −44% to 372% in the near future and from −35% to 415% in the far future.

Figure 8.

Percent changes (%) in monthly average streamflow for 2030–2045 and 2083–2098, compared with observed monthly averages: (a) Karadere gauging station, (b) Findicak gauging station.

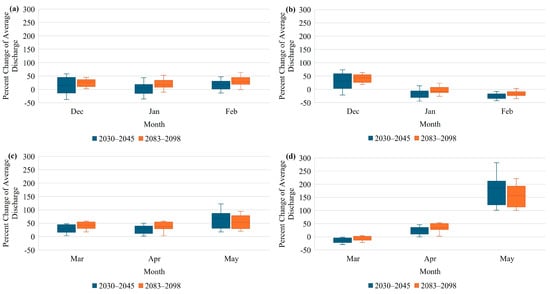

In addition to monthly distributions, the annual cycle was divided into three seasons: spring (March–May), autumn (September–November), and winter (December–February) to better capture streamflow changes outside the summer months (Figure 9). Summer flows are very low and thus not further discussed separately. In the Karadere River, mean flows generally increase compared to the baseline, except for October in the near future, when a decrease is projected. In contrast, the Findicak River shows reductions in mean flows during January, February, and March in both the near and far-future periods, while increases are projected for all other months. These results indicate that although the overall tendency is toward higher average streamflow, localized decreases may occur, particularly in autumn for Karadere and in winter for Findicak.

Figure 9.

Percent changes (%) of average streamflow for the near future (2030–2045) and far future (2083–2098). (a,b) Karadere and Findicak stations in winter (December, January, February), (c,d) Karadere and Findicak stations in spring (March–May), (e,f) Karadere and Findicak stations in autumn (September–November).

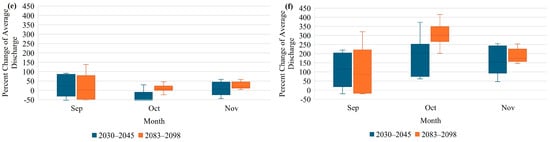

Building on these seasonal assessments, we further evaluated the projected changes in annual mean (Qmean), minimum (Qmin), and maximum (Qmax) flows to better capture potential shifts in hydrological extremes and long-term averages (Figure 10). At the Karadere station, annual mean flow (Qmean) shows modest increases in both future periods, with relatively low uncertainty (−7% to +56% in the near future and +19% to +54% in the far future). Minimum flows (Qmin) are associated with large percentage variations due to their proximity to zero, ranging between −50% and +103% in the near future and −48% to +153% in the far future. Maximum flows (Qmax) exhibit noticeable increases, with wider uncertainty ranges (0.9% to +47% in the near future and +21% to +63% in the far future), indicating a tendency toward higher peak-flow conditions rather than a stable flood regime. At the Findicak station, discharge levels are generally lower compared to Karadere. Annual mean flow (Qmean) again indicates small increases with low uncertainty, varying between −7% and +59% in the near future and +16% to +47% in the far future. Minimum flows (Qmin) show very wide uncertainty bands because of near-zero summer discharges, ranging between +49% and +490% in the near future and +47% to +544% in the far future. In contrast, maximum flows (Qmax) exhibit small changes, with slight reductions projected (−7% to −34% in the near future and −22% to +3% in the far future), indicating a possible decline in flood peaks. Overall, the projections indicate moderate but non-negligible changes in hydrological extremes, with peak flows exhibiting basin-dependent responses and increased uncertainty under future climate scenarios.

Figure 10.

Percent changes (%) in annual minimum, maximum, and mean streamflow for the near (2030–2045) and far (2083–2098) future scenarios: (a) Karadere station, (b) Findicak station. Panels (c) Karadere and (d) Findicak compare observed monthly mean flows with simulated values under RCP4.5, using both the best-performing grid (2921) and the weighted average of four grids (2919, 2920, 2921, 2922).

In addition to the box plot analysis, the comparison of observed and projected monthly average flows (Figure 10c,d) further highlights seasonal tendencies. In these graphs, the modeled flows were obtained using the climate projection data of both the best-performing grid (2921) and the weighted average of four grids (2919, 2920, 2921, 2922) calculated in Table 6. For the Karadere River, both near and far-future scenarios project higher flows during late winter and spring months compared to the observed baseline, with the far-future period showing a more pronounced increase. Summer flows remain close to zero, similar to the baseline. In the Findicak River, projections indicate lower winter flows compared to observations, whereas spring and autumn flows exhibit moderate increases. Although absolute discharge values remain lower than those of Karadere, the projections suggest a seasonal redistribution of flow magnitudes rather than uniform changes across the year. Overall, these results indicate that the general timing of the annual hydrograph is preserved, while the magnitude of seasonal flows—especially during spring—is subject to noticeable change under future climate scenarios. This suggests a tendency toward enhanced seasonal contrasts rather than a fundamental shift in flow regime. The projected changes in streamflow for the Iznik Lake Watershed are consistent with several previous studies conducted in Türkiye and in regions with comparable climatic and topographic characteristics. For instance, ref. [59] reported an increase in winter and early spring flows in mountainous basins of eastern Türkiye, which they mainly attributed to enhanced snowmelt under warmer conditions. Similarly, ref. [27] found that climate change is likely to alter seasonal streamflow patterns in the Gördes Dam Basin, Türkiye, emphasizing that steep slopes combined with projected changes in precipitation can lead to higher streamflow, and that increasing temperatures may trigger earlier spring snowmelt, further enhancing flows. The similarities between their results and our projections strengthen the confidence in the simulated responses of streamflow to future climate forcing in the study area.

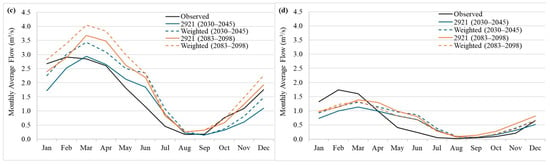

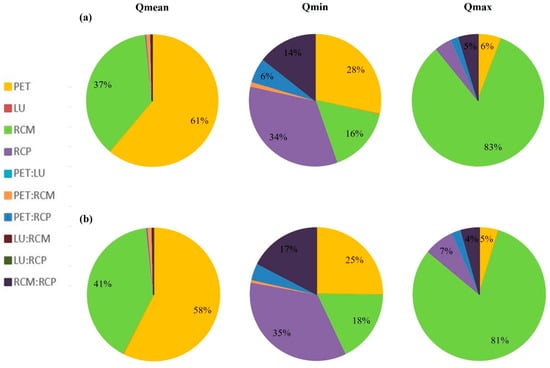

3.5. Uncertainty Analysis Through ANOVA

To provide deeper insights into streamflow uncertainty, both seasonal and annual contributions of different drivers were investigated. Stacked bar plots were used to highlight the temporal dynamics of factor importance at the monthly scale, while complementary pie charts illustrated their aggregated impacts on annual streamflow indices (Qmean, Qmin, Qmax). This combined approach offers a more comprehensive view of the relative role of individual sources of uncertainty across different time horizons.

In Figure 11 and Figure 12, the height of each colored segment represents the share of uncertainty attributed to the main effects and their interactions. Specifically, Figure 11 depicts the near-future (2030–2045) results for Karadere and Findicak stations, while Figure 12 illustrates the corresponding outcomes for the far-future period (2083–2098).

Figure 11.

Uncertainty contributions of potential evapotranspiration (PET), land use change (LU), Regional Climate Model (RCM), Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP), and their interactions to streamflow. (a) Karadere gauge station between 2030–2045, (b) Findicak gauge station between 2030–2045.

Figure 12.

Uncertainty contributions of potential evapotranspiration (PET), land use change (LU), Regional Climate Model (RCM), Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP), and their interactions to streamflow. (a) Karadere gauge station between 2083–2098 (b) Findicak gauge station between 2083–2098.

In the near-future (2030–2045), the stacked bar plots reveal strong seasonal variability in the relative importance of uncertainty sources (Figure 11). RCM dominates during winter months, whereas RCP emerges as the leading driver in autumn. In contrast, PET is the most influential factor in summer, contributing between 70–77% at Karadere and 77–79% at Findicak during June–July. Although PET remains strong in August, its share decreases to 57% at Findicak, allowing RCM and RCP to gain relative importance.

In the far-future (2083–2098), a broadly similar seasonal structure is observed (Figure 12). RCM continues to dominate in winter, and RCP retains its leading role in autumn, while PET remains the primary summer driver. Contributions at Karadere vary between 71–76%, while at Findicak they reach 75–78% in June–July, but PET’s dominance declines to 49% in August, indicating increased influence of RCM and RCP. Overall, PET-related uncertainty remains more stable at Karadere, whereas Findicak exhibits more pronounced seasonal fluctuations. Similar findings were reported by [45] in the Huaihe River Basin, China, where evapotranspiration-related uncertainties accounted for up to 78% of total streamflow variability toward the 2040s and 2080s.

Although LU (land use) was included as a potential driver of uncertainty, its contribution to monthly averaged streamflow remained negligible (<1%) throughout all months in both near- and far-future scenarios. This outcome is consistent with the limited land use changes observed in the watershed between 1990 and 2018 (Figure 3). According to the LULC maps of these years, forest areas decreased by only 2.4%, agricultural lands increased by 2.3%, and bushlands and grasslands declined by 0.9%, while residential, industrial, transportation, and mining areas collectively grew by about 1% [43]. Such minor shifts resulted in minimal hydrological impact at both Karadere and Findicak gauge stations. Moreover, in the SWAT+ model, several LULC classes share similar hydrological parameters (e.g., curve number, soil water capacity, and hydraulic conductivity). These findings suggest that within this watershed, climate-related factors (RCM, RCP, PET) exert a significantly stronger control on streamflow variability than land use dynamics, as was observed in the past [60,61].

Overall, these results indicate a clear seasonal partitioning of uncertainty sources: RCM governs winter, RCP governs autumn, and PET dominates summer. Notably, in the summer months, when streamflow, water balance, and irrigation water demand are critical, the highest share of uncertainty originates from evapotranspiration estimates. This underscores that improving PET calculation methods and refining model performance would directly enhance the reliability of hydrological projections.

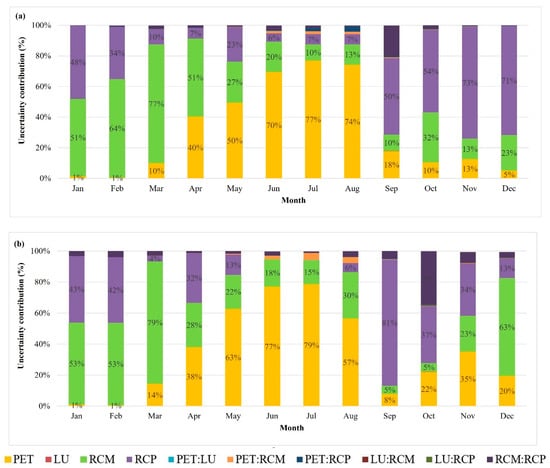

Furthermore, to complement the monthly analyses, pie charts were also produced to summarize the overall contributions of PET, RCM, RCP, and their interactions to the uncertainty of streamflow indices (Qmean, Qmin, Qmax). These figures (Figure 13 and Figure 14) provide an integrated view of how different sources of uncertainty affect average, minimum, and maximum flows at both gauge stations in the near- and far-future periods.

Figure 13.

Uncertainty contributions of PET, LU, RCM, RCP, and their interactions to streamflow indices (Qmean, Qmin, Qmax) for two gauging stations (a) Karadere (2030–2045) and (b) Findicak (2030–2045).

Figure 14.

Uncertainty contributions of PET, LU, RCM, RCP, and their interactions to streamflow indices (Qmean, Qmin, Qmax) for two gauging stations (a) Karadere (2083–2098) and (b) Findicak (2083–2098).

The uncertainty decomposition for streamflow indices (Qmean, Qmin, Qmax) at the Karadere and Findicak stations in the near future (2030–2045) highlights distinct controlling factors (Figure 13). For Qmean, uncertainties are relatively balanced among PET, RCM, and RCP, suggesting that mean-flow projections are jointly sensitive to evapotranspiration estimation, climate model structure, and emission pathway assumptions. In contrast, Qmin is primarily governed by PET (40–45%), with additional contributions from RCP (24–28%), indicating that low-flow projections—and thus drought risk assessments—are strongly influenced by evapotranspiration representation and future greenhouse gas trajectories. Conversely, Qmax is overwhelmingly dominated by RCM uncertainty (77–79%), underscoring the decisive role of climate model selection in flood projections. Interactions among factors play a minor role overall, but modest contributions to Qmin at Findicak suggest that combined effects (e.g., PET and RCP) may become relevant under low-flow conditions. The similarity of patterns across both stations indicates a generalizable trend, while subtle differences—such as stronger PET influence at Findicak—point to site-specific hydrological sensitivities. Overall, these results emphasize the need for multi-source uncertainty analysis in hydrological projections, particularly recognizing PET-driven uncertainty for drought, RCM-driven uncertainty for floods, and a balanced contribution of drivers for mean-flow conditions.

In the far future (2083–2098), the decomposition of uncertainty highlights a shift in the relative importance of drivers compared to the near future (Figure 14). Mean flows (Qmean) are increasingly dominated by PET (58–61%), indicating that evapotranspiration parameterization exerts strong control over long-term water balance. For low flows (Qmin), the contribution of RCP uncertainty rises substantially (34–35%), surpassing PET, which underscores the decisive role of future greenhouse gas emission trajectories in drought projections. By contrast, high flows (Qmax) remain overwhelmingly governed by RCM uncertainty (81–83%), reinforcing the dominant influence of climate model structure on flood extremes. Interactions, particularly between RCM and RCP, become more relevant for Qmin (up to 17%), pointing to a coupled effect of model structure and emission pathway on low-flow variability. The consistency across stations suggests robust trends, although Findicak exhibits slightly greater sensitivity to emission scenario uncertainty for Qmin. Overall, these results highlight a temporal evolution in uncertainty drivers, with PET dominating mean flows, RCP shaping low flows, and RCMs controlling floods toward the end of the century.

A comparison of the near future and the far future reveals a clear temporal shift in the dominant sources of uncertainty for streamflow indices. In the near future, Qmean uncertainty was shared almost equally among PET, RCM, and RCP, whereas in the far future it becomes strongly PET-driven, underscoring the growing influence of evapotranspiration parameterization on long-term mean flows. For Qmin, near-future projections were primarily governed by PET, but in the far future the contribution of RCP uncertainty increases markedly, overtaking PET as the leading driver of low-flow variability. This transition reflects the strengthening role of emission pathway uncertainty in shaping drought risks toward the end of the century. In contrast, Qmax is consistently dominated by RCM uncertainty across both horizons, confirming that climate model structure remains the key determinant of flood extremes regardless of time frame. A similar pattern was also reported by [45] in the Huaihe River Basin, where GCM uncertainty contributed nearly half of the total variance in peak flow (Qmax) simulations. Interactions are minor overall but gain importance for Qmin in far-future projections, particularly through RCM–RCP coupling. Together, these findings suggest that while floods remain structurally controlled by climate model spread, drought and mean-flow projections are increasingly sensitive to emission pathways and evapotranspiration assumptions in the long term.

This section evaluates the projected streamflow changes by quantifying the relative contributions of multiple uncertainty sources, thereby providing a comprehensive interpretation of the results presented in the previous sections. However, an important limitation of this study is that potential future changes in land use, agricultural practices, water withdrawals, and water resource management were not considered in the simulations, which may exacerbate or mitigate the projected hydrological impacts of climate change. Future studies integrating coupled climate–land use–water management scenarios would provide a more holistic assessment of hydrological responses under changing environmental and socio-economic conditions.

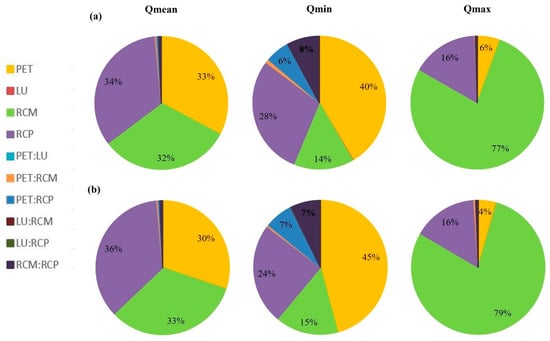

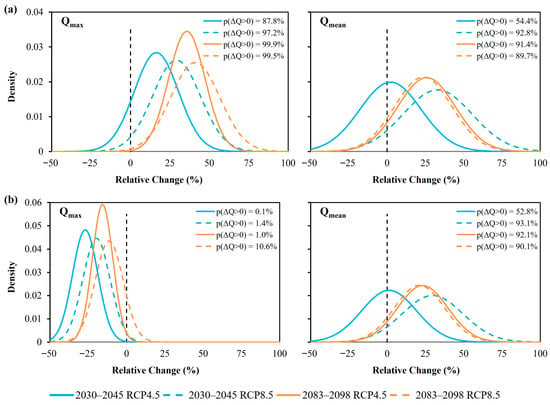

3.6. Probability of Future Streamflow Changes

In addition to the ANOVA-based decomposition of uncertainty, a probabilistic analysis was conducted using Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) to further assess the likelihood of future streamflow changes. In the BMA framework, model weights were adopted from the calculations presented in Table 6, ensuring consistency between the probabilistic analysis and the previously derived model performance metrics. Figure 15 compares the BMA-derived probability distributions of relative changes in Qmax and Qmean for the Karadere (panel a) and Fındıcak (panel b) rivers under near (2030–2045) and far-future (2083–2098) periods and two emission scenarios. The probability of increase, defined as P(ΔQ > 0), is calculated for each distribution.

Figure 15.

Probability of streamflow indices (Qmax, Qmean) for two gauging stations: (a) Karadere and (b) Findicak.

For Karadere, the probability of increased peak flows (Qmax) exceeds 85% under all projected scenarios, indicating that increases in peak streamflow are strongly dominant. In contrast, for the Findicak river, the probability of increase is lower, with decreases expected in the range of 0.1–10.6% depending on the scenario and projection period. These results indicate sub-basin dependent responses, with Karadere exhibiting a higher likelihood of increased peak flows than Fındıcak, highlighting spatial heterogeneity in hydrological sensitivity to climate forcing. The projected changes in Qmean exhibit similar probability ranges for both rivers, with a general tendency toward an increase between 54.4% and 92.8% for Karadere and between 52.8% and 93.1% for Findicak. However, the magnitude of change and associated uncertainty vary under emission scenarios and time horizons, indicating that mean streamflow responses remain sensitive to future climate conditions. The mean relative change (μ) values of Qmean are smaller and have moderate standard deviations (σ) across both rivers, implying a more gradual change in average streamflow with scenario dependent uncertainty. These probabilistic results derived from BMA are consistent with the projected streamflow changes presented in Figure 10a,b, reinforcing the robustness of the identified trends. Low-flow conditions (Qmin) were not explicitly evaluated in the probabilistic comparison, as probability-based interpretations are strongly affected by near-zero baseline values, leading to disproportionately large uncertainties. Overall, these findings collectively suggest a potential intensification of hydrological extremes, characterized primarily by increasing peak flows under future climate scenarios.

3.7. Policy Implications

These findings offer practical implications for risk management and decision-making. By distinguishing the dominant uncertainty sources across different periods, it becomes possible to prioritize parameters more effectively. For example, water resources planning institutions can identify that autumn uncertainties are primarily tied to climate policy scenarios (RCP), while summer uncertainties are driven by hydrological parameters such as PET. Such knowledge strengthens adaptive capacity by clarifying when and where uncertainties are policy-related versus process-related. In turn, this provides valuable guidance for both model development strategies and water management decision-support processes, ultimately answering the question, “Which source of uncertainty should be reduced to achieve more reliable outcomes?” Furthermore, the projected increase in peak flows (Qmax) suggests a potential rise in overall water availability, while simultaneously emphasizing the need for proactive flood risk management and the integration of flood mitigation measures into future water management policies. Moreover, the integration of multiple uncertainty sources enhances adaptive water management in the Marmara Region and underscores the transferability of the proposed framework to comparable watersheds worldwide.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the calibrated SWAT+ model is capable of reliably simulating hydrological processes in the Iznik Lake Watershed and projecting streamflow responses under future climate scenarios. The model calibration and validation were performed using observed temperature, precipitation, and measured streamflow data, ensuring a robust basis for subsequent scenario analysis. Climate projections were then applied for two distinct future periods, near term (2030–2045) and long term (2083–2098), to evaluate the impacts of climate change on streamflow. To comprehensively assess uncertainties, the analysis employed four climate projection datasets under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios, alternative PET calculation methods, and two distinct land-use conditions (1990 and 2018).

The results highlight a clear tendency toward wetter winters and springs but drier summers, accompanied by an overall warming trend. While annual mean flows show modest increases (ranging from −7% to +56% and −7% to +59% in the near future, and +19% to +54% and +16% to +47% in the far future, for the Karadere and Fındıcak Rivers, respectively), peak flows exhibit noticeable increases with basin-dependent responses and associated uncertainty. Low-flow conditions exhibit the largest relative variability during summer months, primarily because baseline discharges are very close to zero.

The ANOVA-based uncertainty analysis revealed that the dominant drivers of uncertainty vary seasonally and across future horizons. Climate models govern flood projections (Qmax, 77–83%), while evapotranspiration parameterizations strongly influence mean flows (Qmean, 58–61%) in the far future. Additionally, greenhouse gas emission trajectories increasingly shape low-flow conditions toward the end of the century (Qmin, up to 35%). These findings emphasize the importance of integrating multi-source uncertainty into water resources planning. The influence of land use changes on streamflow was found to be negligible, consistent with the minor LULC transitions observed between 1990 and 2018. According to the BMA analysis, the probability of an increase in projected peak flows (Qmax) is between 87.8% and 99.9% in Karadere, indicating heightened potential for extreme hydrological events under future climate conditions. This highlights the necessity of integrating flood risk considerations into basin-scale water management and climate adaptation strategies, ensuring that potential increases in water availability are managed in a way that minimizes associated flood risks.

Future research could incorporate crop management practices, groundwater–surface water interactions, and ecological flow requirements to provide a more integrated perspective on climate change impacts and adaptation options. In addition, examining the climate change effects on water balance components such as evapotranspiration, surface runoff, and percolation would further enhance understanding of basin-scale hydrological responses.

From a management perspective, the study provides valuable insights for decision-makers in the Marmara Region. Clarifying whether uncertainties arise mainly from emission pathways or from model structure helps decision-makers target adaptation measures more effectively. The outcomes of this study underscore the need to incorporate climate uncertainty into long-term water resource planning. While the Iznik basin served as a case study, the modeling framework and findings offer a broader contribution, supporting sustainable water management both in Türkiye and in comparable watersheds worldwide. By linking hydrological modeling with adaptive management principles, the results provide a scientific foundation for policy frameworks that aim to balance ecological integrity, agricultural productivity, and water use in a changing climate.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18020187/s1: Table S1: Performance statistics of precipitation and temperature variables under the RCP4.5 scenario for all grid points for the period 2015–2022. PBIAS values are expressed as percentages (%); Table S2: Performance statistics of precipitation and temperature variables under the RCP8.5 scenario for all grid points for the period 2015–2022. PBIAS values are expressed as percentages (%).

Author Contributions

A.Ç.T.: Writing—original draft, methodology, data analysis, validation, visualization. A.A.: Supervision, methodology, writing—review and editing. A.B.: Supervision, methodology, writing—review and editing. Ş.E.: Supervision, conceptualization, methodology, visualization, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the General Directorate of Meteorology (MGM) and the General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works (DSI) for providing the data that significantly contributed to this study. In addition, we sincerely thank MGM for also supplying the climate projection datasets.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial or non-financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, S.; Gu, X.; Singh, V.P.; Sun, P. Global attribution of runoff variance across multiple timescales. J. Geophys. Res. 2019, 124, 13962–13974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hejazi, M. Quantifying the relative contribution of the climate and direct human impacts on mean annual streamflow. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, S.S.; Jha, M.K.; Uniyal, B. Impact of climate change on hydrological fluxes in the Upper Bhagirathi River Basin, Uttarakhand. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boru, G.F.; Gonfa, Z.B.; Diga, G.M. Impacts of climate change on stream flow and water availability in Anger sub-basin, Nile Basin of Ethiopia. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2019, 5, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenkhan, F.; Huggel, C.; Hoyos, N.; Scott, C.A. Hydrology, water resources availability and management in the Andes under climate change and human impacts. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 49, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madasamy, N.; Meiyappan, V.; Muthiah, M.; Elango, S. Hydrological simulation model on climate change impact of a lower Bhavani Basin using GIS and SWAT. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacar, S.; Şan, M.; Kankal, M.; Okkan, U. Trends and amount changes of temperature and precipitation under future projections in the Eastern Black Sea. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 9833–9866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, Z.A.; Bizuneh, Y.K.; Mekonnen, A.G. The combined effects of LULC changes and climate change on hydrological processes of Gilgel Gibe catchment. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, H.M.; Goel, M.K.; Mishra, S.K. Hydrological responses to human-induced land use/land cover changes in the Gidabo River basin, Ethiopia. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2021, 66, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.G.; Bieger, K.; White, M.J.; Srinivasan, R.; Dunbar, J.A.; Allen, P.M. Use of decision tables to simulate management in SWAT+. Water 2018, 10, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, A.D.; Wagner, P.D.; Tigabu, T.B.; Sahlu, D.; Fohrer, N. Hydrological responses to land use and land cover change and climate dynamics in the Rift Valley Lakes Basin, Ethiopia. J. Water Clim. Change 2023, 14, 2788–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casirati, S.; Conklin, M.H.; Nandi, S.; Safeeq, M. Effect of forest management practices on water balance across a water–energy gradient in the upper Kings River Basin, USA. Ecohydrology 2025, 18, e2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Osorio, G.; López-Ballesteros, A.; Perez-Sanchez, J.; Senent-Aparicio, J. Disaggregated monthly SWAT+ model versus daily SWAT+ model for estimating environmental flows in Peninsular Spain. J. Hydrol. 2023, 623, 129837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, H.; Althoff, I.; Huenchuleo, C.; Reggiani, P. Influence of land use changes on the Longaví catchment hydrology in south-center Chile. Hydrology 2022, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumsa, B.C.; Kenea, G.; Tola, B. The application of SWAT+ model to quantify the impacts of sensitive LULC changes on water balance in Guder catchment. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosser, P.F.; Schmalz, B. Assessing the impacts of climate change on hydrological processes in a German low mountain range basin using SWAT+. Environments 2025, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhong, P.A.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Xu, C.; Ben, M.; Li, M. Spatiotemporal attribution of runoff changes in the upper Yangtze River Basin using the SWAT+ model. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 61, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassaye, S.M.; Tadesse, T.; Tegegne, G.; Hordofa, A.T.; Malede, D.A. Relative and combined impacts of climate and land use/cover change for the streamflow variability in the Baro River Basin. Earth 2024, 5, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, H.; Althoff, I.; Celis-Diez, J.L.; Huenchuleo-Pedreros, C.; Reggiani, P. Impact of future climate scenarios and bias correction methods on the Achibueno river basin. Water 2024, 16, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulighe, G.; Lupia, F.; Chen, H.; Yin, H. Modeling climate change impacts on water balance of a Mediterranean watershed using SWAT+. Hydrology 2021, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Fu, C.; Zhang, J. Integrated assessment of climate-driven streamflow changes using CMIP6-SWAT+-BMA. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbaş, A.; Freer, J.; Özdemir, H.; Bates, P.D.; Turp, M.T. What about reservoirs? Questioning anthropogenic and climatic interferences on water availability. Hydrol. Process. 2020, 34, 5441–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuceloglu, G.; Seker, D.Z.; Tanık, A.; Öztürk, İ. Analyzing effects of two different land use datasets on hydrological simulations by using SWAT model. IJEGEO 2021, 8, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elçi, A. Evaluation of nutrient retention in vegetated filter strips using the SWAT model. Water Sci. Technol. 2017, 76, 2742–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakaya, D.; Ozturk, B.; Elçi, S. Hydrokinetic power potential assessment of the Çoruh River Basin. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 82, 101533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, A.; Volk, M.; Strauch, M.; Witing, F. The effects of climate change on streamflow, nitrogen loads, and crop yields in the Gordes Dam Basin, Turkey. Water 2024, 16, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, E. Assessing future changes in flood frequencies under CMIP6 climate projections using SWAT modeling. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 2212–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, H.; Demirel, M.C.; Aşıkoğlu, Ö.L. Effect of model structure and calibration algorithm on discharge simulation in the Acısu Basin, Turkey. Climate 2022, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kışlıoğlu, H.E.; Bekaroğlu, Ş.Ş.; Dadaser-Celik, F. Güney Marmara Havzası’nda SWAT+ modeli ile hidrolojik modelleme. Mühendislik Bilimleri ve Tasarım Dergisi 2024, 12, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkes, M.; Turp, M.T.; An, N.; Ozturk, T.; Kurnaz, M.L. Impacts of climate change on precipitation climatology and variability in Turkey. In Water Resources of Turkey; Harmancioglu, N., Altinbilek, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ulgen, U.B.; Franz, S.O.; Biltekin, D.; Çagatay, M.N.; Roeser, P.A.; Doner, L.; Thein, J. Climatic and environmental evolution of Lake Iznik over the last ~4700 years. Quat. Int. 2012, 274, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koker, L. Health risk assessment of heavy metal concentrations in selected fish species from Iznik Lake Basin, Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oktem, Y.A.; Gumus, M.; Bayrak Yılmaz, G. The potential sources of pollution affecting the water quality of Lake Iznik. Int. J. Mech. Mechatron. Eng. 2012, 2, 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Franz, S.; Schwark, L.; Brüchmann, C.; Scharf, B.; Klingel, R.; Van Alstine, J.D.; Çagatay, N.; Ülgen, U.B. Results from a multi-disciplinary sedimentary pilot study of tectonic Lake Iznik (NW Turkey)—Geochemistry and paleolimnology of the recent past. J. Paleolimnol. 2006, 35, 715–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erginal, A.E.; Kıyak, N.G.; Ozturk, M.Z.; Avcıoğlu, M.; Bozcu, Y.; Yigitbas, E. Cementation characteristics and age of beachrocks in a fresh-water environment, Lake Iznik, NW Turkey. Sediment. Geol. 2012, 243, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viehberg, F.A.; Ulgen, U.B.; Damcı, E.; Franz, S.O.; On, S.A.; Roeser, P.A.; Cagatay, M.N.; Litt, T.; Melles, M. Seasonal hydrochemical changes and spatial sedimentological variations in Lake Iznik. Quat. Int. 2012, 274, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oğuz, A.; Akcaalan, R.; Koker, L.; Gurevin, C.; Dorak, Z.; Albay, M. Driving factors affecting the phytoplankton functional groups in a deep alkaline lake. Turk. J. Bot. 2020, 44, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meşeli, A. Iznik Gölü Havzasında Çevre Sorunları. Dicle Univ. J. Ziya Gökalp Fac. Educ. 2010, 14, 134–148. [Google Scholar]

- Akbulak, C. Iznik Gölü Havzasında Arazi Kullanımının Seçilmiş Köyler Üzerinde İncelenmesi (Investigation of Land Use on Selected Villages in the Iznik Lake Basin). İstanbul Üniv. Edeb. Fak. Coğraf. Böl. Coğraf. Derg. 2007, 15, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Garipagaoglu, N.; Uzun, M. The Effects of Natural Environment Conditions, Changes and Possible Risks on Watershed Management and Planning in Basin of Iznik Lake. East. Geogr. Rev. 2019, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sezer Güney, B.; Karaer, F. Estimation of Solöz River water balance components and rainfall runoff pattern with WEAP model. Water 2025, 17, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezel, A.Ç.; Akpınar, A.; Bor, A.; Alfredsen, K.T. Exploring hydrological response to land use/land cover change using the SWAT+ model in the Iznik Lake Watershed, Türkiye. Water 2025, 17, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M.B.; Nacar, S.; Şan, M.; Kankal, M. Spatial and temporal patterns of drought under different scenarios for Türkiye. Phys. Chem. Earth 2025, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Gan, R.; Feng, D.; Yang, F.; Zuo, Q. Quantifying the contribution of SWAT modeling and CMIP6 inputting to streamflow prediction uncertainty under climate change. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 364, 132675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.G.; Kiniry, J.R.; Srinivasan, R.; Williams, J.R.; Haney, E.B.; Neitsch, S.L. Soil & Water Assessment Tool: Input/Output Documentation, Version 2012 TR-439; Texas Water Resources Institute: College Station, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ozsoy, G. Determination of the Potential Erosion Risk Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques. Ph.D. Thesis, Bursa Uludağ University, Bursa, Türkiye, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, J.G.; Srinivasan, R.; Muttiah, R.S.; Williams, J.R. Large area hydrologic modeling and assessment part I: Model development. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1998, 34, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieger, K.; Arnold, J.G.; Rathjens, H.; White, M.J.; Bosch, D.D.; Allen, P.M.; Volk, M.; Srinivasan, R. Introduction to SWAT+, a completely restructured version of the soil and water assessment tool. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2017, 53, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neitsch, S.L.; Arnold, J.G.; Kiniry, J.R.; Williams, J.R. Soil and Water Assessment Tool Theoretical Documentation: Version 2009; Texas Water Resources Institute Technical Report No: 406; Texas A&M University System: College Station, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chawanda, C.J. SWAT+ Toolbox: User Manual. 2021. Available online: http://www.openwater.network/assets/downloads/SWATplusToolboxUserMannual.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Kling, H.; Fuchs, M.; Paulin, M. Runoff conditions in the upper Danube basin under an ensemble of climate change scenarios. J. Hydrol. 2012, 424, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]