Abstract

Against the backdrop of increasingly evident climate change and frequent extreme weather events, flash floods have emerged as a major challenge for flood disaster prevention and mitigation in China. Flash flood early warning systems are crucial means to address this challenge, primarily comprising rainfall-based warnings (RW) and discharge-based warnings (DW). To support precise flash flood warnings, this study compares the effectiveness of RW and DW and summarizes their applicable scenarios through both case study analysis and model simulations. The results demonstrate that DW outperforms RW under the following scenarios: ① During persistent moderate-intensity rainfall events when antecedent soil moisture is moderate to high, RW is prone to missed or delayed warnings. ② When rainfall exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity, RW tends to produce false alarms. Conversely, RW outperforms DW in the following scenarios: ① For localized short-duration heavy rainfall events, DW is prone to missed or delayed warnings. ② In basins where numerous small- and medium-sized reservoirs exist upstream without operational data, DW is prone to false alarms. ③ When sparse or unevenly distributed rain gauges result in poor representativeness of areal rainfall, DW is prone to missed warnings. To enhance flash flood disaster management, future warning systems should integrate both RW and DW approaches to deliver more timely, reliable, and scientifically grounded warning information for local authorities.

1. Introduction

Under the increasingly evident impacts of climate change and the growing frequency of extreme weather events, flash floods have gradually become a major focus of disaster prevention and mitigation efforts worldwide [1]. The occurrence of flash flood disasters is not isolated but rather the outcome of the interplay between rainfall processes and terrestrial hydrological processes within a specific spatiotemporal context. Understanding its formation mechanisms is an important foundation for identifying flash flood risks and improving warning methods. Currently, numerous studies have shown that hydro-meteorological conditions and underlying surface characteristics are important factors in the formation of flash floods. Gaume et al. conducted a detailed compilation and statistical analysis of more than 550 extreme flash flood events across seven different hydro-meteorological regions in Europe [2]. They found that the magnitude of extreme flash floods in Mediterranean coastal countries was greater than that in inland countries, and the occurrence of flash floods exhibited distinct seasonality. Mediterranean-type flash floods are usually triggered by prolonged heavy rainfall. For example, in 2011, such rainfall in the Liguria region of Italy caused severe flash floods with serious consequences. In contrast, continental-type flash floods are mainly caused by rapid convergence of surface runoff resulting from intense rainfall or snowmelt, commonly occurring in mountainous areas with steep terrain, sparse vegetation, and weak soil infiltration capacity. Seasonally, continental flash floods are mostly concentrated in summer.

In addition to differences in hydro-meteorological conditions, watershed underlying surface factors are also key determinants of whether flash floods occur. Hapuarachchi et al. indicate that effective flash flood forecasting relies on accurately characterizing the rainfall-runoff accumulation mechanisms within a watershed, while these mechanisms are evidently influenced by both the static physical characteristics of the basin and their time-varying states, such as soil moisture [3]. In humid and semi-humid regions of China, such as Fujian Province, saturation excess runoff is the dominant runoff generation mechanism. Under this mechanism, once there is antecedent continuous rainfall, even moderate subsequent rainfall can lead to a sharp jump in the runoff coefficient, triggering flash floods. Marchi et al. collected and analyzed 22 flash flood events in Europe (involving 80 watersheds) and found that antecedent soil moisture significantly affects the runoff coefficient. In arid and semi-arid regions, infiltration-excess runoff is the main mechanism [4]. Once rainfall intensity exceeds the infiltration rate, surface runoff is rapidly generated regardless of whether the deeper soil is saturated [5]. Due to loose soil and sparse vegetation in such areas, erosion of the soil layer is intensified during floods, making them prone to triggering debris flows. As a predominantly mountainous country with about two-thirds of its territory covered by hills and mountains, China is highly vulnerable to flash flood disasters. Compounded by its location in the East Asian monsoon region, the country experiences frequent and intense summer rainfall that often leads to rapid flood rise and recession. These events repeatedly result in substantial casualties and economic losses [6,7]. Statistics show that since the beginning of the 21st century, flash floods in China have caused approximately 1000 fatalities annually, accounting for about 70% of all flood-related deaths [8]. Flash floods have thus become a significant factor constraining socioeconomic development in many regions of the country [9]. In summary, the mechanisms behind flash flood formation are complex and are highly destructive worldwide, making it essential to comprehensively apply different warning methods to improve warning accuracy.

Flash flood early warning technology is a crucial means of preventing flash flood disasters and mitigating associated losses. It represents a key component of non-structural measures for flash flood risk management [10]. Two main approaches for flash flood warning are rainfall-based warning (RW) and discharge-based warning (DW) [11]. Research on flash flood early warning technology began earlier abroad. Among these, the Flash Flood Guidance (FFG) system developed by the U.S. National Weather Service stands out as the most representative example. The FFG determines rainfall thresholds that may trigger flash floods under different soil moisture conditions by combining real-time soil water content data with hydrological modeling. These thresholds are then compared with observed rainfall to decide whether to issue a warning [12]. This system has been applied in several countries, including the United States, Italy, and India [13,14]. In Japan, a watershed rainfall index-based warning method has been developed by establishing the correlations between rainfall and surface runoff, while accounting for watershed topography, geology, and land use. Warnings are issued when the rainfall index exceeds predetermined thresholds [15]. Meanwhile, France’s flood warning system employs a discharge-based method known as AIGA (Adaptation d’Information Géographique pour l’Alerte en Crue) [16]. This approach integrates radar-estimated rainfall data into hydrological models to simulate discharge, which is then compared with discharge thresholds corresponding to different return periods predefined at various points along the river network. Exceedance of these thresholds triggers warnings. Drawing on international experience, China has developed its own rainfall-based early warning system that reflects the country’s unique characteristics of heavy rainfall and complex underlying surface conditions [15]. In recent years, many researchers have begun to explore discharge-based early warning methods to provide early warnings before the flood peak arrives and thereby reduce potential losses. Although the two approaches rely on different criteria, both methods follow the same principle—issuing a warning once the observed or simulated disaster-inducing factor exceeds the corresponding threshold.

In recent studies, Corral et al. selected three events that triggered multiple localized floods in the Liguria region of northwestern Italy to compare the outcomes of rainfall-based and discharge-based warning systems [16]. The results demonstrated good consistency between the two systems in estimating the evolution and magnitude of hazard levels, and did not support the conclusion that discharge-based warning systems are superior to rainfall-based ones. Gourley et al. collected flood events from the Arkansas-Red River Basin in the south-central United States to evaluate a rainfall-threshold warning approach and the Distributed Hydrological Model Threshold Frequency method—the latter first constructs a rainfall-based hydrological model and then compares the simulated peak discharges with historically simulated values [17]. Their findings indicated that the latter generally outperformed the former, though the study did not classify the rainfall events that triggered flash floods; therefore, the relative advantages of these methods under specific scenarios remain unclear. Versini et al. examined two rainfall events in the Guadalhorce Basin in southeastern Spain to compare rainfall-based and discharge-based warning methods, showing that both were able to issue accurate warnings [18]. Current research indicates that both warning methods can effectively predict floods; however, it remains unclear which approach performs better under specific conditions such as rainfall intensity, precipitation pattern, and antecedent soil moisture. To address this, this study collects six flood events and employs a combination of case analysis and quantitative analysis. By comparing the performance of the two warning methods across different scenarios, the respective advantageous conditions for rainfall-based warning and discharge-based warning are clearly identified.

At present, China has established a nationwide monitoring system for flash flood disasters [19,20], significantly enhancing its capacity for disaster prevention, mitigation, and response. However, the complexity of environmental conditions leads that current warning methods and systems still frequently generate false and missed alarms in operational applications [8]. Consequently, improving warning accuracy has become a key research priority. A fundamental prerequisite for such improvement is a clear understanding of the relative strengths and limitations of different warning methods under various scenarios. An intense rainfall event triggers a disaster depends not only on the magnitude of precipitation and discharge [21,22], but also on multiple additional factors such as antecedent soil moisture [23,24], temporal distribution of rainfall [25], spatial rainfall variability [26,27], underlying surface conditions of the watershed [28], and the density and layout of gauge networks [29]. Given this complex influencing mechanism, a detailed analysis and comparative study of the applicability of discharge-based versus rainfall-based warning methods across different scenarios is both necessary and valuable.

To compare the applicability of the two early warning methods across varying conditions and to improve the precision of flash flood warnings in Fujian Province, this study investigates historical flash flood events in the region. Through a combination of case study analysis and hydrological model simulations, we evaluate the performance of both rainfall-based and discharge-based warning methods, identifying the specific scenarios where each method demonstrates superior effectiveness.

2. Study Area and Data Sources

2.1. Study Area

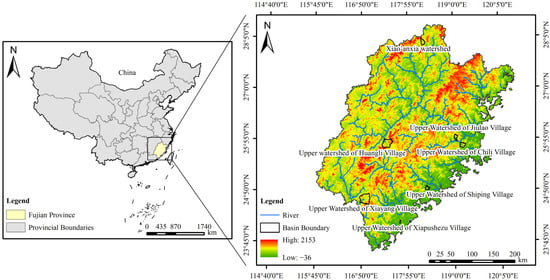

Fujian Province, located along the southeastern coast of China between 23°31′–28°18′ N and 115°50′–120°43′ E, experiences a subtropical maritime monsoon climate, characterized by an average annual rainfall ranging from 1400 to 2000 mm. The terrain slopes from higher elevations in the northwest to lower coastal areas in the southeast, forming a characteristic mountainous and coastal landscape. Hills and mountains cover approximately 90% of the province, making the region highly prone to typhoons and flash floods. This study analyzes historical flash flood events in six villages—Xiayang, Huangli, Chili, Shiping, Xiapushezu, and Jiulao. The Xiao’anxia watershed is selected for hydrological simulation analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the locations of the upstream catchments of the selected villages and the Xiao’anxia watershed.

Figure 1.

Geographic location map of the study area. Review Number: GS (2020) 4619.

2.2. Data Collection

This study collected data on heavy rainfall events, flood characteristics, and disaster impacts for six villages (Xiayang, Huangli, Chili, Shiping, Xiapushezu, and Jiulao) in 2024, as summarized in Table 1. The rainfall-based warning threshold for each village and discharge-based warning thresholds for the Xiao’anxia watershed, along with the watershed characteristics, were obtained from the National Flash Flood Survey and Assessment database, as shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Xin’anjiang model parameters applied to the Xiao’anxia watershed are listed in Table 4.

Table 1.

Table of watershed areas and historical flood events.

Table 2.

Rainfall and flow warning indicators for villages and the Xia’an watershed.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the seven representative villages and their upstream catchments.

Table 4.

Model parameters and range of values for the Xin’anjiang model in the Xia’an Lower Basin.

3. Methodology

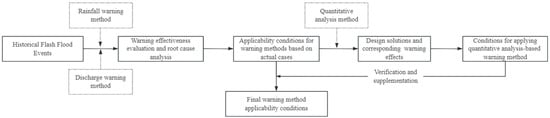

This study employs both case analysis and model simulation approaches to identify the optimal application scenarios for each warning method. The analysis begins with an evaluation of historical flash flood events to assess the performance and limitations of both rainfall-based and discharge-based warnings under varying conditions. Subsequently, hydrological model simulations are applied to validate and refine these applicability conditions. Ultimately, the specific scenarios where each method demonstrates superior performance are determined.

In this study, hydrological simulations were performed using the Xin’anjiang rainfall–runoff model integrated into the Fujian Provincial Flash Flood Early Warning Platform (Water Resources Bureau of Fujian Province, Fuzhou, China). Rainfall and runoff data are collected from the Water Yearbook of Fujian Province. Spatial data processing and watershed delineation were conducted using QGIS 3.34.6 (QGIS Development Team, Zürich, Switzerland). Statistical analyses and figure preparation were performed using Python 3.9 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA).

3.1. Rainfall-Based Warning Approach

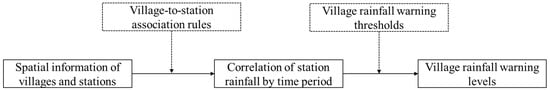

The rainfall-based warning procedure operates as follows: First, a spatial association is established between each village and the rain gauges within its upstream watershed area and within a 5 km radius of the village center. When the observed rainfall at any of the associated stations exceeds the village’s rainfall warning threshold, a warning is issued for that village. The rainfall-based warning process is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Rainfall warning process.

3.2. Discharge-Based Warning Approach

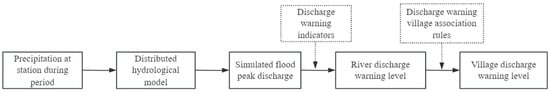

The discharge-based warning procedure operates as follows: during a rainfall event, if the simulated peak discharge at the river section nearest to a village exceeds the discharge warning threshold, an early warning is triggered. This study employs the distributed Xin’anjiang model for flood simulation [30,31,32]. To capture the spatial heterogeneity of rainfall across the watershed, the basin is divided into multiple sub-catchments. Runoff generation and concentration are computed for each sub-catchment, and the overall outflow hydrograph is derived by linearly aggregating the individual outflows. The workflow of the discharge-based warning process is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Discharge warning process.

3.3. Warning Performance Evaluation Method

Based on historical flash flood events in the upstream catchments of Xiayang, Huangli, Chili, Shiping, Xiapushezu, and Jiulao villages in Fujian Province, this study analyzes and compares the warning performance of rainfall-based and discharge-based early warning methods.

The evaluation of warning performance for historical flash flood events in the watersheds categorizes outcomes into hits, false alarms, and misses. A hit indicates that an early warning was correctly issued when flooding occurred, or no warning was issued when no flood occurred. A false alarm refers to a warning issued without an actual disaster, while a miss indicates a disaster occurrence without a corresponding warning. In cases where both rainfall-based and discharge-based warnings were activated, they were further classified based on the sequence of triggering: either rainfall warning preceded discharge warning, or vice versa.

Following the evaluation, the underlying causes of the warning performance were analyzed by examining factors such as rainfall magnitude, temporal rainfall distribution, spatial rainfall variability, antecedent soil moisture, reservoir regulation effects, and rain gauge network density. Based on these analyses, the applicability conditions of each early warning method were identified from historical cases. However, as these conditions were based on limited case observations, hydrological simulations were performed to test their robustness and to evaluate the effects of additional influencing factors.

Finally, for scenarios where warning performance was sensitive to the timing of alert triggering, a quantitative analysis was designed to simulate disaster-forming processes. This approach was used to validate and refine the applicability conditions derived from historical cases, yielding the final applicability scenarios of the two early warning methods. The overall research framework is illustrated in Figure 4. It should be explicitly noted that the spatial heterogeneity of rainfall is accounted for in this study through the use of the distributed Xin’anjiang model.

Figure 4.

Technology roadmap.

Based on the case-derived applicability conditions, a series of simulation scenarios were designed to examine the influence of key rainfall and catchment factors on warning performance. The selected variables and their values are as follows:

(1) Rainfall duration: 1 h, 3 h, and 6 h;

(2) Total rainfall: below and above the early-warning threshold;

(3) Rainfall pattern: decreasing-type, uniform-type, and increasing-type temporal distribution;

(4) Antecedent soil moisture: 60% (low), 75% (moderate), and 90% (high) of the maximum soil water storage capacity (WM), where WM denotes the maximum basin water storage capacity.

All quantitative simulations were conducted using the distributed Xin’anjiang hydrological model in the Xiaoanxia catchment. Given that the downstream villages have a 20-year design flood protection standard, any rainfall or discharge event exceeding the return period corresponding to this standard was assumed to represent a flood hazard.

4. Result and Discussion

The historical flash flood events in hilly watersheds were categorized into two groups based on the relative performance of the two early warning methods under different conditions. The first group represents cases where the discharge-based warning outperformed the rainfall-based warning, including three scenarios:

- DW provided earlier warning than RW.

- RW resulted in a missed alarm, while DW correctly produced a hit.

- RW resulted in a false alarm, while DW correctly avoided one (a hit for non-occurrence).

The second group represents cases where the rainfall-based warning outperformed the discharge-based warning, including:

- RW provided earlier warning than DW.

- DW resulted in a missed alarm, while RW correctly produced a hit.

- DW resulted in a false alarm, while RW correctly avoided one (a hit for non-occurrence).

DW is issued by comparing simulated discharges—generated using the distributed Xin’anjiang model that integrates data from multiple rainfall stations—against predefined warning thresholds. RW is issued when the cumulative rainfall at any single rainfall station associated with a village exceeds its warning threshold.

4.1. Superior Performance of Discharge-Based Warnings

4.1.1. Discharge-Based Warning Triggered Earlier than Rainfall-Based Warning

(1) Case Analysis

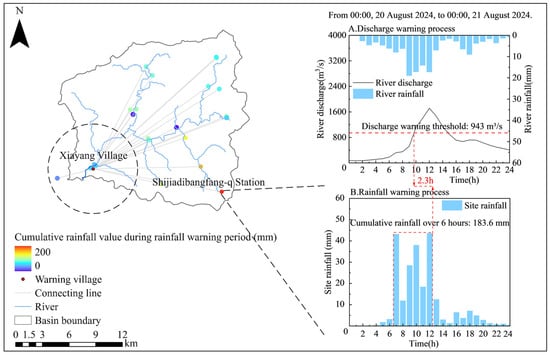

The flash flood event in Xiayang Village on 20–21 August 2024, was successfully detected by both warning methods. The discharge-based warning was triggered at 09:42, approximately 2 h and 18 min earlier than the rainfall-based warning at 12:00. This time advantage is attributed to the rainfall pattern, characterized by sustained moderate to heavy rainfall. Rainfall-based warnings typically rely on fixed-duration thresholds of 1, 3, and 6 h. In this case, neither the 1 h nor the 3 h cumulative rainfall exceeded the corresponding thresholds, and it was not until the 6 h accumulation that the rainfall-based warning was triggered. In contrast, the simulated discharge captured the continuous rise in flow during the rainfall process, allowing a warning to be triggered promptly once the discharge threshold is exceeded.

The rainfall and runoff characteristics of the Xiayang Village flash flood event are illustrated in Figure 5. In terms of rainfall conditions, heavier precipitation was concentrated in the southeastern part of the upstream catchment. The maximum 6 h accumulated rainfall reached 183.6 mm at the Shijiadibangfang-q Station (recorded from 06:00 to 12:00 on 20 August), exceeding the 6 h rainfall warning threshold (Figure 5B). Hydrologically, the simulated peak discharge at the stream associated with Xiayang Village reached 1717 m3/s, with a runoff coefficient of 0.79. The simulated discharge exceeded the warning threshold at 09:42 on 20 August, as shown in Figure 5A.

Figure 5.

Map of the upper watershed of Xiayang Village and the warning process.

(2) Quantitative analysis

Through carefully designed comparative scenarios, this study assesses the influence of temporal rainfall distribution and antecedent soil moisture conditions on warning trigger times under persistent moderate- to high-intensity rainfall. In the quantitative analysis scenarios, the total rainfall amounts were set to exceed the corresponding rainfall warning thresholds for the relevant periods in the Xia’anxia downstream catchment, reflecting the conditions observed during the Xiayang Village flash flood event. The specific experimental design is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Quantitative analysis framework based on the Xiaoyang Village flood event.

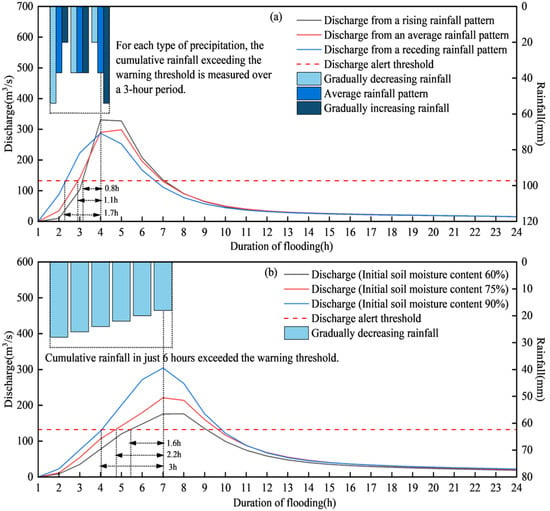

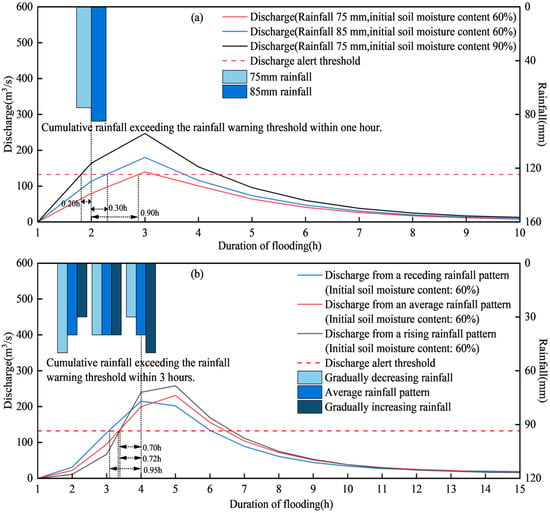

Rainfall pattern comparative scenarios (Scenario 1):

In Scenario 1, the antecedent soil moisture was held constant while the rainfall temporal distribution was varied, resulting in three parallel experiments to investigate the influence of rainfall patterns on the timing of discharge-based early warning. As shown in Figure 6a, under all three rainfall patterns (descending, uniform, and ascending), the 1 h cumulative rainfall did not exceed the warning threshold. It was only when the 3 h cumulative rainfall reached 111 mm that the rainfall-based warning was triggered. In contrast, the discharge-based warning was activated earlier because the hydrological model continuously simulated the evolving peak discharge in real time.

Figure 6.

Rainfall–discharge process diagrams for scenarios 1 and 2. (a) Model simulation results for the rainfall pattern comparison scenario (Scenario 1); (b) model simulation results for the soil moisture content comparison scenario (Scenario 2).

Under identical rainfall duration, total rainfall volume, and antecedent soil moisture conditions, the order of discharge warning timing from earliest to latest, and of peak flow magnitude from smallest to largest, was consistently: decreasing rainfall pattern, uniform pattern, and increasing rainfall pattern. Therefore, under conditions of sustained moderate-to-high intensity rainfall and relatively high antecedent soil moisture, discharge-based warnings consistently provide earlier alerts than rainfall-based warnings, regardless of the temporal distribution of rainfall.

Antecedent soil moisture competitive scenarios (Scenario 2):

By maintaining a fixed temporal rainfall distribution while varying the antecedent soil moisture content, this scheme reveals the influence of initial soil moisture conditions on the timing of discharge-based warnings. As illustrated in Figure 6b, the timing of the discharge-based warning is progressively delayed as the antecedent soil moisture decreases. When the initial soil moisture was further reduced to around 40% or lower, situations may arise where a rainfall-based warning is triggered while the discharge-based warning is not, or where the rainfall-based warning precedes the discharge-based warning. Therefore, under sustained moderate-to-high intensity rainfall with normal or high antecedent soil moisture, the discharge-based warning tends to be triggered earlier than the rainfall-based warning.

A comparison between the first experiment of Scenario 1 and the third experiment of Scenario 2 further indicates that under conditions of sustained moderate-to-high intensity rainfall, the discharge-based warning is consistently triggered earlier than the rainfall-based warning for both the 3 h and 6 h warning durations. This shows that the earlier triggering of discharge-based warnings under such rainfall conditions is not influenced by the duration of the warning period.

In summary, in hilly watersheds, under persistent moderate-to-high intensity rainfall, discharge-based warnings are consistently issued earlier than rainfall-based warnings when antecedent soil moisture is normal or high. This earlier triggering by the discharge-based method is insensitive to the temporal rainfall distribution and the duration of the warning period.

4.1.2. Missed Rainfall-Based Warning but Successful Discharge-Based Warning

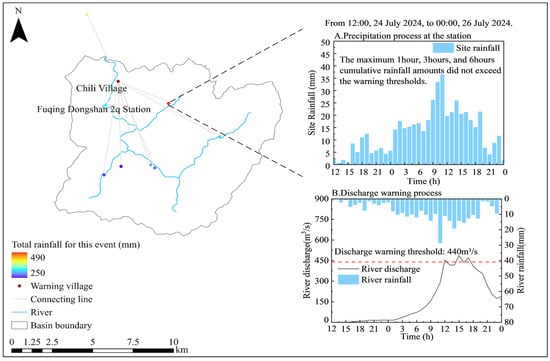

The flash flood event in Chili Village from 24 to 26 July 2024 was successfully forecasted by the discharge-based warning (triggered at 11:50), while the rainfall-based warning failed to issue an alert. This missed rainfall-based warning was primarily attributed to the persistent moderate- to low-intensity rainfall pattern. In this event, the maximum 1 h, 3 h, and 6 h cumulative rainfall values did not exceed their respective warning thresholds. While the discharge-based method was able to account for the cumulative effect of continuous rainfall and consequently triggered the warning in time.

Figure 7 presents detailed rainfall and discharge characteristics of this event. In terms of rainfall, the maximum cumulative rainfall among gauges associated with Chili Village was recorded at the Fuqing Dongshan 2q station, reaching 487.6 mm between 12:00 on 24 July and 00:00 on 26 July. The maximum 1 h, 3 h, and 6 h rainfall values were 36.5 mm, 96.1 mm, and 162.9 mm, respectively, all below the corresponding warning thresholds of 93.99 mm, 135.5 mm, and 170.66 mm (Figure 7A). Hydrological simulations indicate a peak discharge of 544 m3/s in the stream linked to Chili Village, with a runoff coefficient of 0.61. The discharge warning threshold was exceeded at 11:50 on 25 July (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Map of the upper watershed of Chikari Village and the warning process.

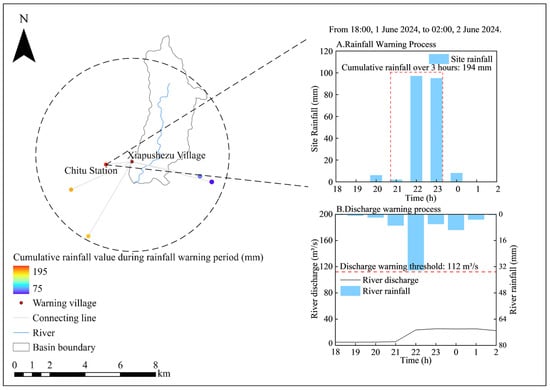

4.1.3. False Rainfall-Based Warning but Successful Discharge-Based Warning

The monitored rainfall-based warning (issued at 23:00 on 1 June 2024) for Xiapushezu Village during the 1–2 June flash flood event resulted in a false alarm, while the discharge-based warning correctly withheld an alert. The false alarm in the rainfall-based warning is primarily due to the spatial heterogeneity of precipitation. Intense short-duration rainfall occurred outside the upstream catchment of the village, where the 3 h accumulated rainfall exceeded the warning threshold. However, as shown in Figure 8B, rainfall along the rivers within the associated catchment was relatively weak, and the heavy precipitation outside the catchment had no decisive influence on the rising stage of discharge in the village’s associated river reach. Therefore, in hilly watersheds, under conditions of spatially heterogeneous rainfall, especially when intense rainfall occurs outside the village catchment, the discharge-based warning provides higher accuracy than the rainfall-based method.

Figure 8.

Map of the upper watershed of Xiapushezu Village and the warning process.

As illustrated in Figure 8, the maximum 3 h accumulated rainfall reached 194 mm at the Chitu station (from 21:00 to 23:00 on 1 June), exceeding the 3 h rainfall warning threshold of 144.3 mm (Figure 8A). Spatially, higher rainfall was observed in the southwestern area outside the village’s upper watershed. Hydrologically, the simulation showed a peak discharge of 25.4 m3/s with a runoff coefficient of 0.43 (Figure 8B). This indicates that, although localized heavy rainfall occurred near the basin boundary, it did not generate significant runoff within the catchment, confirming that the rainfall-based early warning produced a false positive while the discharge-based method correctly avoided one.

4.2. Superior Performance of Rainfall-Based Warnings

4.2.1. Rainfall-Based Warning Triggered Earlier than Discharge-Based Warning

(1) Case Analysis

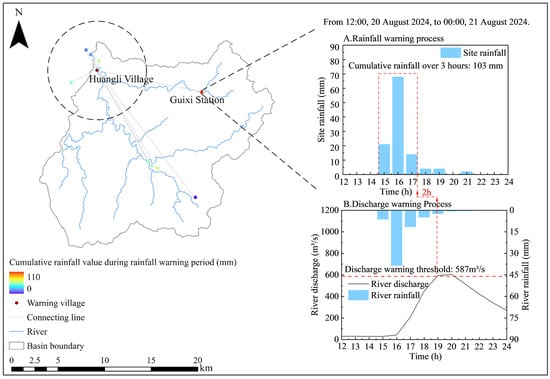

During the flash flood disaster monitoring period from 20 to 21 August 2024, both the rainfall-based warning (issued at 17:00) and the forecasted discharge-based warning (issued at 19:00) successfully provided alerts for the flash flood event in Huangli Village. The rainfall-based warning was issued two hours earlier than the discharge-based warning primarily because this flash flood was triggered by short-duration heavy rainfall within the Huangli River basin, where the 3 h cumulative rainfall at the monitoring station exceeded the warning threshold. In contrast, discharge-based warnings rely on hydrological modeling, and the simulation process for calculating peak discharge involves multiple computational steps, resulting in an inherent time lag. This lag prevented the discharge-based warning from being issued as promptly as the rainfall-based warning.

Figure 9 illustrates the rainfall-runoff details of this flash flood event in Huangli Village. In terms of rainfall conditions, the central area of the upstream watershed received the heaviest precipitation, with rainfall intensity gradually decreasing towards the northern and southern parts. The maximum 3 h cumulative rainfall was recorded at 103 mm by the Guixi Station (from 15:00 to 17:00 on 20 August), exceeding the 3 h rainfall warning threshold of 101.2 mm, as shown in Figure 9A. Regarding runoff conditions, the simulated peak discharge at the relevant channel in Huangli Village reached 605 m3/s, with a runoff coefficient of 0.55. The simulated discharge exceeded the discharge-based warning threshold at 19:00 on 20 August, as presented in Figure 9B.

Figure 9.

Map of the upper Huangli Village watershed and warning process.

(2) Quantitative analysis

By establishing comparative experiments, this study evaluates the impact of rainfall intensity and hydrological model response time on warning trigger timing during short-duration heavy rainfall events in the basin. Since the flood event in Huangli Village triggered a rainfall-based warning, all total rainfall values in the quantitative analysis scheme of this section exceeded the corresponding rainfall warning thresholds. The specific experimental design is detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Quantitative analysis framework for the Huangli Village flood event.

The rainfall intensity comparison scenario (Scenario 3) was designed with three parallel experiments by maintaining a fixed rainfall duration while varying total rainfall amounts and antecedent soil moisture conditions, to evaluate their impacts on warning trigger timing. As shown in Figure 10a, under conditions of low antecedent soil moisture, when the 1 h rainfall slightly exceeded the warning threshold (71 mm), the rainfall-based warning was triggered earlier than the discharge-based warning. If the 1 h rainfall decreased to the range of 71–75 mm, missed discharge warnings were likely to occur. If the 1 h rainfall increased to 100 mm, the discharge-based warning could be triggered earlier than the rainfall-based warning. Under conditions of high antecedent soil moisture, when the 1 h rainfall just exceeded the warning threshold, the discharge-based warning was triggered 0.2 h earlier than the rainfall-based warning, as illustrated in Figure 10a. Therefore, under conditions of low antecedent soil moisture and short-duration heavy rainfall where the cumulative rainfall does not significantly exceed the warning threshold, rainfall-based warnings are issued earlier than discharge-based warnings, and missed discharge warnings are more likely to occur.

Figure 10.

Rainfall–discharge process diagrams for scenarios 3 and 4. (a) Model simulation results for the rainfall intensity comparison scenario (Scenario 3); (b) model simulation results for the model response scenario (Scenario 4).

The model response scenario (Scenario 4) was designed with three parallel experiments by maintaining a fixed rainfall duration of 3 h while varying rainfall patterns. Comparative analysis with the warning results from the rainfall intensity comparison scheme reveals the impact of hydrological model response time on warning trigger timing. Under conditions where the 1 h and 3 h cumulative rainfall do not significantly exceed the warning thresholds and antecedent soil moisture is low, when the rainfall duration is 1 h, the rainfall-based warning is triggered earlier than the discharge-based warning, as shown in Figure 10a. When the rainfall duration extends to 3 h, the discharge-based warning is triggered earlier than the rainfall-based warning, and this sequence remains unaffected by variations in rainfall patterns, as demonstrated in Figure 10b. Therefore, if the model response time is insufficient, rainfall-based warnings will be triggered earlier than discharge-based warnings, and this regularity is not affected by rainfall patterns.

In conclusion, in hilly watersheds, under conditions of low antecedent soil moisture in the watershed, when short-duration heavy rainfall occurs and the cumulative rainfall does not significantly exceed the warning threshold, the rainfall-based warning is triggered earlier than the discharge-based warning, and missed discharge warnings are more likely to occur.

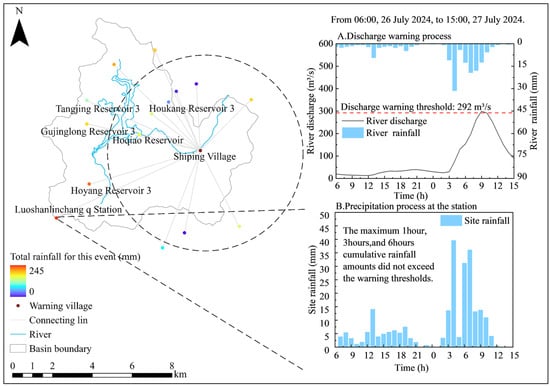

4.2.2. Successful Rainfall-Based Warning but False Discharge-Based Warning

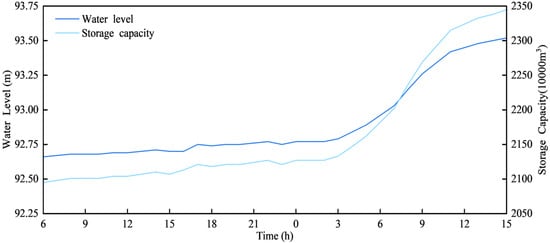

During the flash flood disaster forecast from 26 to 27 July 2024, the discharge-based warning (issued at 8:55) was activated for the event in Shiping Village. This incident resulted in a false alarm in discharge-based warning, with no rainfall-based warning issued. The false discharge warning was primarily attributed to the presence of numerous small- and medium-sized reservoirs in the upstream watershed of Shiping Village that lack operational data. As shown in Figure 11, four reservoirs in the upstream watershed—Houyang Reservoir 3, Gujinglong Reservoir 3, Tangjing Reservoir 3, and Houkang Reservoir 3—lack storage capacity data. Only Houqiao Reservoir has available data, with its water level rising by 0.86 m and storage capacity increasing by 2.5 million m3, as illustrated in Figure 12. Therefore, in hilly watersheds, when a watershed contains numerous small- and medium-sized reservoirs lacking operational data, the hydrological model calculations become unreliable and are prone to generating false discharge warnings. Under such conditions, rainfall-based warnings provide more accurate results than discharge-based warnings.

Figure 11.

Map of the upper Shiping Village watershed and warning process.

Figure 12.

Hoqiao reservoir water level–storage capacity curve.

Figure 11 illustrates the rainfall-runoff details of this flash flood event in Shiping Village. In terms of rainfall conditions, the southwestern part of the upstream watershed experienced heavier precipitation. The Luoshanlinchang q Station recorded the highest cumulative rainfall, with a total of 244.9 mm from 06:00 on 26 July to 15:00 on 27 July. The maximum 1 h, 3 h, and 6 h rainfall amounts were 36.9 mm, 80.5 mm, and 137.6 mm, respectively, all of which remained below their corresponding warning thresholds of 95.47 mm, 151.15 mm, and 201.99 mm, as shown in Figure 11B. Regarding runoff conditions, the simulated peak discharge at the relevant channel in Shiping Village reached 300 m3/s, with a runoff coefficient of 0.97. The simulated discharge exceeded the discharge-based warning threshold at 08:55 on 27 July, as shown in Figure 11A.

4.2.3. Successful Rainfall-Based Warning but Missed Discharge-Based Warning

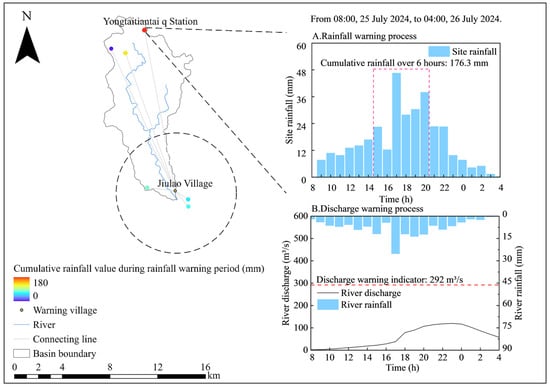

On 25–26 July 2024, the rainfall-based warning (issued precisely at 20:00) successfully warned of the flash flood disaster in Jiulao Village. The scenario represented a hit rainfall-based warning but missed a discharge-based warning, primarily due to the sparse and uneven distribution of rainfall stations in the upstream watershed of Jiulao Village, which resulted in low accuracy in the calculation of areal rainfall.

Discharge-based warnings require that the point rainfall data from associated stations provide a reasonably accurate representation of the areal rainfall. When the representativeness of this point rainfall data is poor, the accuracy of discharge-based warnings becomes inferior to that of rainfall-based warnings. For rainfall-based warnings, an alert is triggered simply when the cumulative rainfall at any of the village’s associated stations exceeds the warning threshold, with no additional computational steps required. Therefore, in areas where the representativeness of point rainfall data is suboptimal, it is recommended to adopt a combined early warning approach that integrates both discharge-based and rainfall-based methods to enhance the accuracy of warning results.

Figure 13 illustrates the rainfall-runoff details of this flash flood event in Jiulao Village. In terms of rainfall conditions, the northern part of the upstream watershed of Jiulao Village experienced heavy precipitation. The maximum 6 h cumulative rainfall was recorded at 176.3 mm by the Yongtaitiantai q Station (from 15:00 to 20:00 on 25 July), exceeding the 6 h rainfall warning threshold of 174.87 mm, as shown in Figure 13A. Regarding runoff conditions, the simulated peak discharge at the relevant channel in Jiulao Village reached 120 m3/s, with a runoff coefficient of 0.44. The simulated discharge did not exceed the discharge-based warning threshold, as presented in Figure 13B.

Figure 13.

Map of the upper Jiulao Village watershed and warning process.

4.3. Discussion

This study has certain limitations that suggest avenues for further research. First, the analysis is based on only six historical flood events, which restricts our ability to fully capture the natural variability of rainfall–runoff processes and warning performance under a broader spectrum of conditions. Second, some of our conclusions, particularly those regarding the relative timing of warnings in Section 4.1.1 and Section 4.2.2, rely partly on hydrological model simulations. Although the Xin’anjiang model has been validated for the study area, inherent uncertainties remain in representing extreme rainfall spatial patterns, soil moisture heterogeneity, and subsurface hydrological processes. Third, the findings are derived specifically from humid subtropical mountainous catchments in southeastern China. Consequently, their direct transferability to regions with distinct hydroclimatic regimes—such as arid areas, snowmelt-driven basins, or large lowland river systems—may be limited and requires further investigation. Finally, the rainfall-based warning method employs fixed-duration thresholds (1 h, 3 h, and 6 h), which, while aligned with operational practice in China, may not fully accommodate the diverse temporal structures of rainfall events, potentially introducing uncertainty in the comparative performance assessment between rainfall-based and discharge-based approaches. The generalizability of our findings is also constrained by the common challenge in flash flood research: the lack of long-term, parallel observational records of warning performance across multiple similar catchments. These limitations highlight important directions for future research, including the collection of more event data, the refinement of threshold designs, and the testing of the proposed framework in different geographical and climatic settings.

5. Conclusions

Taking historical flash flood events in selected river basins of Fujian Province as case studies and incorporating the simulation results of the quantitative analysis scheme for the Xiao’anxia Basin, this study conducted a warning analysis using both rainfall-based and discharge-based warning methods. In hilly watersheds, the performance and applicable conditions of these two warning methods under different scenarios were summarized as follows:

(1) Scenarios where discharge-based warning (DW) is superior to rainfall-based warning (RW) include when antecedent soil moisture in the basin is normal or high and sustained moderate to high-intensity rainfall occurs; when sustained low to moderate-intensity rainfall occurs, and the maximum 1 h, 3 h, and 6 h cumulative rainfall amounts all remain below the warning thresholds; and when rainfall distribution is uneven, such as when intense rainfall occurs outside the basin but upstream of the village.

(2) Scenarios where rainfall-based warning (RW) is superior to discharge-based warning (DW) include when short-duration heavy rainfall occurs under conditions of low antecedent soil moisture in the basin and the cumulative rainfall does not significantly exceed the warning thresholds; when numerous small- and medium-sized reservoirs without operational data exist in the upstream watershed of a village, which can easily lead to false alarms in discharge warnings and thus reduce their accuracy; and when rainfall stations are sparse or unevenly distributed, resulting in poor representativeness of point rainfall measurements for areal rainfall. In such cases, a combined approach utilizing both discharge-based and rainfall-based warning methods should be adopted to improve the accuracy of warning results.

In summary, discharge-based warnings typically outperform rainfall-based ones for most persistent rainfall events in hilly watersheds. However, in specific scenarios such as short-duration heavy rainfall, absence of operational data for reservoirs, or uneven distribution of rainfall stations, rainfall-based warnings provide more accurate results. To enhance capabilities regarding disaster prevention, mitigation, and emergency response, as well as to improve warning accuracy, this study suggests establishing a dynamically weighted integrated warning framework. This framework would dynamically compute and integrate rainfall-based and discharge-based warning information by adapting to real-time hydro-meteorological conditions—such as rainfall intensity, duration, and antecedent soil moisture—along with local watershed characteristics. The aim is to deliver more timely, reliable, and scientifically grounded warning information to local communities. The findings of this study provide a practical reference for implementing such a framework.

This study further advances existing research findings. The current literature lacks comparative investigations on the effectiveness of flood warnings under various scenarios. By employing actual case studies and model simulations, this research fills a critical knowledge gap regarding the comparative performance of rainfall-based warnings (RWs) and discharge-based warnings (DWs) under specific conditions—including antecedent soil moisture content, rainfall intensity, spatial rainfall distribution, reservoir operations, and rain gauge network density—and identifies the optimal application scenarios for each warning method. These findings contribute significantly to reducing false alarm rates in flood warning systems. The six study catchments are all humid subtropical hilly basins with steep terrain, thin soils, relatively short concentration times, and rapid hydrological response—conditions typical of many flash-flood–prone regions in southern China and other monsoon-influenced mountainous areas of Asia. Therefore, the conclusions are representative primarily for small to medium mountainous catchments with similar hydro-meteorological and physiographic characteristics.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the work presented in this paper. Conceptualization, R.L. and J.S.; methodology, Y.D. and J.W.; software, Y.D. and X.L.; data curation, J.W. and X.L.; project administration and supervision, Y.D. and J.S.; writing—original draft, Y.D. and J.W.; visualization, J.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.D., R.L. and J.S.; funding acquisition, Y.D., X.L. and R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ningbo Water Resources Science and Technology Program Project (Grant No. NSKA202507); the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFC3006700); and the Supported by State Key Laboratory of Water Cycle and Water Security (Project No. SKL2025TDGG05).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available because they are derived from an operational flash flood early warning system and are subject to data access restrictions imposed by the managing authority.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xu, N. Extreme weather frequent attacks. Disaster Reduct. China 2011, 3, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gaume, E.; Bain, V.; Bernardara, P.; Newinger, O.; Barbuc, M.; Bateman, A.; Blaškovičová, L.; Blöschl, G.; Borga, M.; Dumitrescu, A.; et al. A compilation of data on European flash floods. J. Hydrol. 2009, 367, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapuarachchi, H.A.P.; Wang, Q.J.; Pagano, T.C. A review of advances in flash flood forecasting. Hydrol. Process. 2011, 25, 2771–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, L.; Blöschl, G.; Borga, M.; Delrieu, G.; Gaume, E.; Samuels, P.; Sempere-Torres, D.; Stancalie, G.; Szolgay, J.; Tsanis, I. Characterisation of flash floods based on analysis of extreme European events. J. Hydrol. 2009, 394, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabinejad, S.; Schüttrumpf, H. Flood Risk Management in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges, Needs, and Opportunities. Water 2023, 15, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J. Research Framework and Anticipated Results of Flash Flood Disasters Under the Mutation of Sediment Supply. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2019, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Ma, M.; Li, Q.; Liu, L.; Wang, X. Current Situation and Characteristics of Flash Flood Prevention in China. China Rural. Water Hydropower 2021, 5, 133–138+144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Ding, W.; Wang, X. Research Framework and Anticipated Results of the Key Technology and Integrated Demonstration of Mountain Torrent Disaster Monitoring and Early Warning. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2018, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhang, P.; Ren, H.; Ding, W. Review and development trend on mountain torrents disaster monitoring and pre-warning research and technologies. Yangtze River 2019, 50, 35–39+73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Xu, Z.; Yan, X.; Wang, X. Comparative study on methods of early warning index of flash flood disaster induced by rainstorm. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2020, 52, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, P.; Liu, X. Research progress and prospects of flash flood simulation and warning models. China Flood Drought Manag. 2025, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qin, G.; Wang, X.; Miao, R.; Liu, Y. Advances in Study on Flash Flood Forecast and Warning. J. China Hydrol. 2014, 34, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Georgakakos, K.P. Analytical results for operational flash flood guidance. J. Hydrol. 2006, 317, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbiato, D.; Borga, M.; Degli Esposti, S.; Gaume, E.; Anquetin, S. Flash flood warning based on rainfall thresholds and soil moisture conditions: An assessment for gauged and ungauged basins. J. Hydrol. 2008, 362, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Chen, X. Rainfall Threshold for Flash Flood Early Warning Based on Flood Peak Modulus. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2017, 19, 1643–1652. [Google Scholar]

- Corral, C.; Berenguer, M.; Sempere-Torres, D.; Poletti, L.; Silvestro, F.; Rebora, N. Comparison of two early warning systems for regional flash flood hazard forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2019, 572, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourley, J.J.; Flamig, Z.L.; Hong, Y.; Howard, K.W. Evaluation of past, present and future tools for radar-based flash-flood prediction in the USA. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2014, 59, 1377–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versini, P.A.; Berenguer, M.; Corral, C.; Sempere-Torres, D. An operational flood warning system for poorly gauged basins: Demonstration in the Guadalhorce basin (Spain). Nat. Hazards 2014, 71, 1355–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Nie, R.; Liu, X.; Xu, W. Research Conception and Achievement Prospect of Key Technologies for Forecast and Early Warning of Flash Flood and Sediment Disasters in Mountainous Rainstorm. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2020, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Mountain torrent disaster prevention and control measures and their effects. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2016, 47, 1–5+11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y. Regression Analysis of Flood Response to the Spatial and Temporal Variability of Storm in the Jinjiangxixi Watershed. Resour. Sci. 2011, 33, 2226–2231. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, B.; Leonard, M.; Deng, Y.; Westra, S. An empirical investigation into the effect of antecedent precipitation on flood volume. J. Hydrol. 2018, 567, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Li, H. Real-time multi-source information assimilation improves multi-layer soil moisture for real-time flood forecasting. Adv. Water Sci. 2024, 35, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Chen, Z. Research on critical rainfall of mountain torrent disasters based on effective antecedent rainfall. J. Nat. Disasters 2014, 23, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Liu, A. Characteristics of intra-storm temporal pattern over China. Adv. Water Sci. 2014, 25, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Li, H.; Mao, B. Influence of rainfall spatial distribution on critical rainfall calculation for early warning of flash floods. Yangtze River 2017, 48, 15–19+100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, W.; Zhang, J. Study on dynamic critical rainfall warning index considering spatial heterogeneity of rainfall. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 51, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lin, Z.; He, R.; Zhang, J.; Wu, L.; Tong, J.; Xu, Y. Responding patterns and influencing factors of soil moisture under different underlying surfaces over the Taihu Lake basin. Adv. Water Sci. 2024, 35, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Sang, G.; Liu, L.; Liu, W.; Li, Q. Evaluation and optimization of rainfall station network rationality for flood forecasting. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2024, 55, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R. The xinanjiang model. IAHS Publ. 1980, 129, 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z. The Distributed Xin’anjiang Model Incorporating the Analytic Solution of the Storage Capacity Under Unsteady-State Conditions. Water 2024, 16, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M. Recent and future studies of the Xinanjiang Model. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2021, 52, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.