Abstract

Regional water systems face growing pressure from climate variability, water scarcity, and increasingly complex wastewater pollution. These challenges require governance models that integrate institutional coordination with effective technological solutions. This review is based on a structured analysis of peer-reviewed literature indexed in Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect, covering publications from approximately 2014 to 2025. The findings show that clearly defined institutional roles, basin-level coordination, stable financing mechanisms, and active stakeholder participation significantly improve governance outcomes. Technological advances such as membrane filtration, advanced oxidation processes, nature-based treatment systems, and digital monitoring platforms enhance treatment efficiency, resilience, and opportunities for resource recovery. Regions differ widely in their ability to adopt these solutions, mainly due to variations in governance coherence, investment capacity, and climate-adaptation readiness. The review highlights the need for policy frameworks that align institutional reforms with technological modernization, including the adoption of basin-based planning, digital decision-support systems, and circular water-economy principles. These measures provide actionable guidance for policymakers and regional authorities seeking to strengthen long-term water security and wastewater management performance.

1. Introduction

Water resources are increasingly becoming a limiting factor for socioeconomic development, and the water crisis is one of the key global threats of the 21st century. According to the latest United Nations World Water Development Report 2023 (WWDR), global water consumption has grown by an average of 1% per year over the past 40 years, driven by population growth, urbanization, and a shift in economic structure toward water-intensive industries. At the same time, the impact of climate change is intensifying: increasingly frequent droughts, extreme precipitation, and floods are destabilizing the water cycle and making traditional water use planning schemes increasingly unreliable [1].

Freshwater shortages are not limited to arid regions. According to estimates by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and other specialized organizations, water stress is affecting increasingly more areas, including agricultural and industrial zones, where competition between agriculture, industry, and the public sector is leading to a reallocation of resources in favor of short-term economic interests [2].

In Europe, for example, in 2022, water stress conditions of varying severity were observed in at least one season across 34% of the European Unions (EU) territory, despite a long-term decline in water withdrawals [3]. FAO and United Nations (UN) Water forecasts indicate that without changes to water resource management approaches, a significant portion of the global population will live in regions with “absolute” water scarcity or persistent water stress [4].

At the same time, the problem of wastewater pollution is worsening. According to global inventories, approximately 40–50% of the world’s wastewater is discharged into the environment without adequate treatment, with significant regional variations in collection and treatment levels [5]. Recent UN-Water estimates indicate that in 2022, approximately 42% of household wastewater worldwide was not adequately treated, equivalent to more than 100 billion m3 of untreated wastewater returned to natural water bodies [6]. This increases the pressure on ecosystems, increases public health risks, and jeopardizes the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 6 (access to water and sanitation for all) [7].

All of these trends manifest themselves extremely unevenly. The water crisis takes different forms across different regions of the world: in some areas, quantitative resource scarcity dominates, in others, water quality degradation, and in still others, a combination of both factors, exacerbated by climate change and rapid urban growth. This regional differentiation complicates the development of universal approaches and highlights the need for adapted governance models at the subnational level [4].

Against this backdrop, the regional level of water resource and wastewater management, where the interests of the state, local government, business, and the public intersect, is particularly important. Studies assessing water management in individual provinces and municipalities show that key functional gaps are concentrated at the grassroots and regional levels: insufficient institutional interaction, fragmentation of powers, and weak coordination between sectors [8].

One of the most pressing problems is the pronounced unevenness of water availability across regions. Even within a single country, areas with a relative abundance of resources can coexist with regions with chronic shortages, dependent on transboundary tributaries or irregular precipitation. This requires flexible schemes for interregional resource redistribution and special water use regimes, which are difficult to implement without a well-established system of interlevel interaction.

Financial constraints on regional and local budgets exacerbate institutional weaknesses. An analysis of decentralized water resource management in countries of the Global South shows that the devolution of authority to the local level is often not accompanied by a sufficient redistribution of financial and human resources, leaving local authorities nominally responsible but effectively incapable of ensuring sustainable management [9]. This manifests itself, in particular, in the inadequate maintenance and modernization of treatment facilities, delays in the implementation of modern technologies, and limited monitoring capabilities. Practical examples of technological modernization can also be observed at the municipal level. Several wastewater treatment plants in major urban centers of Kazakhstan have undergone phased upgrades focusing on energy efficiency, nutrient removal, and automated process control. According to national infrastructure development programs, modernization measures have led to measurable reductions in energy consumption and improved compliance with discharge standards, demonstrating the feasibility of incremental technological upgrading under regional budget constraints [10].

The weak integration of water policy across different levels of government remains a serious challenge. Studies of regional water management demonstrate that strategies and plans developed at the national level are not always adequately translated into realistic regional programs that take into account specific natural, climatic, socioeconomic, and institutional conditions [11]. As a result, a disconnect arises between norms and practice: formally progressive principles of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) are not implemented in specific projects, wastewater treatment schemes, and tariff policies. At the same time, digital transformation, which could serve as a bridge between governance levels, is progressing extremely unevenly. A number of countries have shown that the implementation of digital platforms, smart water metering, and decision support systems significantly improves the efficiency of water resources management, but such solutions require significant investment and expertise that is not always available at the regional level [12].

Given the complexity and multidimensionality of the challenges described, a comprehensive analysis is needed that integrates the institutional dimension (norms, organizations, regulatory mechanisms) and the technological dimension (modern wastewater treatment solutions, digital tools, nature-based technologies). The purpose of this review is to systematize institutional models and technological approaches to strategic water resources and wastewater treatment management at the regional level, identifying key barriers and conditions for successful implementation.

The novelty of this review lies primarily in its purposeful integration of two typically separately considered dimensions—institutional and technological. While much of the current literature focuses either on the technical aspects of wastewater treatment or on water management and policy issues, this paper offers a holistic view of how institutional settings determine the choice and scalability of technological solutions, which in turn shape the strategic management agenda [11]. A second important contribution is the emphasis on the regional level as a key link in the implementation of national and international commitments to water security and sustainable development. Drawing on recent studies assessing local and regional water governance in various countries, the review demonstrates that regional institutions and practices often act as bottlenecks or, conversely, drivers of successful water sector transformation [8].

Finally, this work focuses not only on describing current issues but also on the strategic dimension of governance: it examines long-term planning, risk management, the integration of digital and nature-based solutions, and the building of partnerships between government, business, and society—all within a framework consistent with the priorities outlined in the WWDR-2023 on partnerships and cooperation in the water sector. This positions the review as a contribution to the development of more integrated and sustainable models of water resource and wastewater treatment management at the regional level.

To ensure the transparency and representativeness of this review, a structured literature search was conducted using the Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect databases. The analysis covered peer-reviewed publications published between 2014 and 2025, reflecting recent developments in regional water governance and wastewater treatment. In total, approximately 180 publications were initially identified, of which about 100 sources were selected for in-depth analysis based on relevance, scientific quality, and thematic alignment with the objectives of the study. The search strategy employed combinations of key terms such as “regional water governance”, “water resources management”, “wastewater treatment technologies”, “integrated water resources management”, “basin-based management”, “nature-based solutions”, “digital water management”, and “institutional frameworks”. Additional relevant studies were identified through backward reference screening of key review and policy-oriented papers. The selected literature was systematically analyzed to identify dominant institutional models, technological approaches, governance challenges, and factors influencing the effectiveness of regional water resources and wastewater management.

2. Institutional and Theoretical Foundations of Regional Water Governance

2.1. Conceptual and Theoretical Approaches to Water Governance

Modern approaches to water resources regulation and management have evolved at the intersection of hydrology, economics, law, political science, and public administration theory. At the theoretical level, at least three interrelated concepts are key: water management, water governance, and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). These concepts provide a framework for analyzing institutional mechanisms, regulatory instruments, and the choice of technological solutions, including at the regional level.

Classical water management has historically focused on engineering, technical, and operational aspects: flow regulation, reservoir construction, water intake allocation, and the operation of treatment facilities and distribution networks. In this paradigm, the primary goal was ensuring reliable water supply and protection from water hazards, with government agencies and technical services serving as key subjects [13].

The concept of water governance emerged in response to the recognition that the water crisis is largely a crisis of institutions and decision-making processes, not just physical water scarcity. Water governance, as governance, is understood as the totality of political, social, economic, and administrative systems through which society formulates water policy goals, makes decisions, and implements measures to develop, distribute, and protect water resources. Water governance thus extends far beyond the activities of government agencies and includes the private sector, local communities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and scientific organizations. This shift in focus from “government” to “governance” emphasizes the importance of stakeholder participation, transparency, accountability, and multi-level engagement [14].

The concept of IWRM is an attempt to unify fragmented approaches to managing water, land, and related resources. A widely cited definition describes IWRM as a process of coordinated development and management of water, land, and related resources within a basin to maximize socioeconomic well-being without compromising ecosystem resilience [15].

Modern studies emphasize that IWRM serves two functions: it serves as a framework for a set of institutional mechanisms (legislation, organizations, procedures) and, simultaneously, as a set of management principles focused on intersectoral coordination, stakeholder participation, and consideration of ecosystem constraints [16].

Thus, theoretically, water management reflects primarily the technical and operational dimension, water governance reflects the institutional and procedural dimension, and IWRM provides an integrative framework that connects both dimensions within a river basin or region. For further analysis of regional wastewater treatment policy and technological solutions, it is important to link these levels into a single analytical framework.

In the following sections, these concepts are not revisited as abstract definitions but are applied as an integrated analytical framework for examining regional institutional arrangements and governance practices.

Table 1 systematizes the fundamental concepts used in modern water resources management theory, including water management, water governance, IWRM, multi-level governance, and the basin approach. Each concept is briefly explained, its typical application levels are outlined, and examples of sources where the concept is discussed in detail are provided. The table serves as a conceptual framework for further analysis of institutional and technological decisions at the regional level.

Table 1.

Key theoretical concepts in water resources management and their key characteristics.

From a public governance perspective, water crises are interpreted as “governance crises,” when existing institutions and mechanisms fail to adapt to growing and changing challenges. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) analysis conducted as part of the Water Governance Initiative found that the gap between policy goals and implementation practices is often due to inconsistencies across government levels, insufficient transparency, and weak stakeholder participation [21].

In response, the OECD developed 12 Principles of Water Governance, which provide a universal framework for assessing the effectiveness of water policy. These principles are structured around three pillars: effectiveness (clear roles and responsibilities, policy coherence, and a basin-wide approach); resource efficiency (adequate financial and human resources, data and information, and innovation); and trust and engagement (transparency, accountability, stakeholder participation, and institutional integrity) [22,23].

Multi-level governance, in this logic, is understood as a system in which national, regional, and local authorities jointly implement water policy, but simultaneously face gaps in competence, finance, information, and responsibility. Multi-level governance theory proposes analyzing these gaps and developing mechanisms to overcome them—through basin councils, interagency coordinating bodies, horizontal partnerships between regions, and the inclusion of the private sector [24].

For strategic water and wastewater management, the key is the combination of regulatory frameworks, institutional architecture, and specific regulatory instruments—administrative, economic, infrastructural, and informational. In this theoretical perspective, wastewater treatment technologies are viewed as part of a broader system in which their implementation and scalability depend on the quality of institutions, coordination, and incentive mechanisms.

These theoretical approaches provide a useful lens for assessing how global governance principles are translated into national and regional policy contexts. Kazakhstan’s experience in water resources management illustrates how international theoretical approaches are adapted to national and regional conditions. The water legislation of the Republic of Kazakhstan, including the new Water Code, enshrines the goals of sustainable management and protection of water resources based on the basin principle, combining the objectives of water supply, environmental protection, and economic development [25]. Even the early documents of Kazakhstan’s national IWRM plan emphasized the need to transition from administrative-territorial to basin-based management, the creation of river basin councils, and the involvement of water users in decision-making. This reflects the integrative potential of IWRM as an institutional framework: basin councils become an arena for dialogue between the state, agricultural and industrial water users, the municipal sector, and the environmental community [26].

In modernizing its water policy, Kazakhstan is actively focusing on international principles of good water governance. New versions of the Water Code and government documents emphasize the objectives of increasing transparency, digitalization, improving resource efficiency, and strengthening interagency coordination [25]. In 2025, the Presidential Address and government decisions set the goal of creating a unified digital water resource management platform that integrates data on surface and groundwater, the development of a national water balance, and the use of artificial intelligence for monitoring and forecasting [27]. From a theoretical perspective, such initiatives demonstrate a shift from classical resource management to a model in which digital technologies are becoming not only an operational tool but also part of the institutional architecture of water governance: they support transparency, improve the timeliness of information, and expand opportunities for various actors to participate in water policy discussions at the regional level. In practical terms, elements of this approach are already being tested through national and regional initiatives. According to official data from the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation of Kazakhstan, pilot digital water accounting systems have been introduced in selected river basins, including the Syr Darya and Irtysh basins, enabling automated monitoring of water abstraction volumes and improving data consistency between regional authorities. These pilot implementations aim to reduce unaccounted water losses and improve the accuracy of basin-level water balances, which are critical for strategic planning and allocation decisions [28].

Table 2 shows how key international principles—such as the basin approach, multi-level governance, transparency, stakeholder participation, digitalization, and sustainability—are implemented in Kazakhstan’s legislation, institutional framework, and strategic documents. The comparison draws on data from recent analytical reports by the OECD, Asian Development Bank (ADB), United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), and academic publications. The material demonstrates that Kazakhstan is moving toward compliance with international standards, but faces significant institutional gaps and regional differences.

Table 2.

Compliance of Kazakhstan’s water resources management system with the global water governance framework.

The theoretical framework discussed above allows for a new approach to water resource and wastewater treatment regulation at the regional level. First, it emphasizes that a region cannot be considered in isolation from its basin context: water management decisions in a specific area or agglomeration must be linked to the overall river basin regime, ecosystem service requirements, and transboundary effects.

Second, within the logic of water governance, a region acts as a key link in a multi-level system where national norms and strategies are translated into specific programs for modernizing treatment facilities, developing infrastructure, and implementing nature-based solutions and digital monitoring systems. This highlights both the strengths and weaknesses of the institutional architecture: the success of technological innovation depends on the quality of coordination between basin authorities, local executive bodies, utility operators, and industrial water users.

Third, the integrative logic of IWRM provides a theoretical basis for linking institutional and technological solutions. The choice of wastewater treatment technologies (membrane systems, bioreactors, nature-based structures, etc.) is not only an engineering issue but also an institutional one, as it requires sustainable tariff regulation, access to investment, clear rules for risk and benefit allocation, and reliable data on the condition of water bodies.

For Kazakhstan, as for other countries with pronounced regional differences in water conditions, the theoretical foundations of water governance and IWRM are important not only as academic constructs but also as a practical basis for reform, including the updating of water legislation, the development of basin institutions, the implementation of a unified digital platform, and the alignment of strategic planning mechanisms at the regional and river basin levels.

Despite their wide international acceptance, global approaches to water resources management are not free from conceptual and practical limitations. Integrated Water Resources Management and related governance frameworks are often criticized for their normative character and limited operationalization at the regional level. In practice, the implementation of IWRM frequently encounters institutional fragmentation, insufficient coordination between administrative and basin boundaries, and weak enforcement mechanisms. Moreover, the effectiveness of global governance principles varies significantly across contexts, depending on political stability, administrative capacity, financial resources, and data availability.

Contradictions also emerge between the flexibility promoted by adaptive governance models and the rigid regulatory structures present in many countries, where legal and budgetary systems remain highly centralized. In regions with limited institutional capacity, the transfer of global governance models may result in formal compliance without substantive changes in management practices. These challenges are particularly evident in countries undergoing governance transitions, where international frameworks must be selectively adapted rather than directly adopted. As a result, the successful application of global water governance approaches depends not only on their conceptual soundness but also on their contextualization to regional institutional realities, socioeconomic conditions, and technological readiness.

2.2. Institutional Models and Governance Mechanisms at the Regional Level

Regional water resources management is formed within a complex system of distributed powers between the state, regional authorities, municipal structures, and basin organizations. Recent literature emphasizes that institutional architecture determines the system’s capacity for adaptation, strategic planning, and effective implementation of water policy. According to De Stefano and López-Gunn (2015), the distribution of roles between governance levels is a key factor in the sustainability of the water sector, as a multi-layered governance structure can both enhance coordination and create contradictions among process participants [32].

The structure of institutional levels and their functions is presented in Table 3. The table reflects the distribution of functions, regulatory instruments, and key challenges among the national, regional, and municipal levels, basin organizations, and stakeholders.

Table 3.

Institutional levels of governance, their functions and instruments.

In many countries, the national level is responsible for establishing the legal and regulatory framework, developing strategic documents, allocating budgetary funds, and establishing general principles of water policy. Within the framework of regional governance, it is national structures that determine mandatory water quality standards, wastewater discharge standards, water consumption limits, and sustainability criteria for aquatic ecosystems. However, as research by Bhaduri et al. (2016) has shown, even with clear national strategies, their implementation depends on the ability of regional institutions to adapt regulations to the local context and effectively coordinate various categories of water users [33].

The regional level of governance is the key link where water resource allocation, water intake management, infrastructure maintenance, approval of regional programs, and interactions between sectors are implemented. Fischer and Newig (2016) note that regional authorities are often forced to balance national policy requirements and the economic interests of local stakeholders, which leads to an asymmetry of authority and institutional burden on regional units [34]. In the context of rapidly changing climatic and socio-economic conditions, the ability of regions to adaptively manage is becoming a determining factor in sustainability.

The municipal level occupies a special place, responsible for the operation of public water supply and sanitation systems, the operation of treatment facilities, fee collection, and emergency response. According to Van Rijswick et al. (2014), municipal authorities most often face operational and financial constraints: they must address infrastructure-level issues with limited access to data, finance, and qualified personnel [14]. In countries where municipal structures have limited autonomy, there is a high risk of underfunding of infrastructure and inconsistency in local programs.

River Basin Organizations (RBOs) complement the institutional architecture of regional regulation. In a number of countries, including the EU, Australia, China, and South Africa, basin institutions ensure integrated planning within hydrographic basin boundaries, thereby overcoming administrative barriers between territories. According to Gupta and van der Zaag (2008), RBOs are key mechanisms for implementing IWRM principles, as they enable long-term planning based on the actual hydrological cycle [35]. However, the effectiveness of basin structures depends on the availability of financial resources, the authority to make binding decisions, and systematic interaction with regional and municipal authorities.

Interdepartmental coordination is an integral element of the institutional architecture. Water resources are used by numerous sectors—agriculture, energy, industry, utilities, transport, and environmental protection—leading to competing interests. As Howlett and Rayner (2007) note, the lack of coordination between sectors creates a situation of “policy drift,” where each administrative structure pursues its own goals without considering the cumulative risks to the water system [36]. Therefore, the interconnectedness of water policy with environmental, energy, and land management strategies is a crucial characteristic of regional governance.

Stakeholder participation is considered one of the most significant instruments of regional governance. The goal of involving the public, businesses, farmers, environmental organizations, and industrial enterprises in the decision-making process has gained significant momentum in recent years. Reed (2008) emphasizes that stakeholder participation increases the legitimacy of decisions, reduces conflict, and ensures local adaptation of policies, which is especially important at the regional level [37]. Basin councils, public hearings, and feedback mechanisms are becoming mandatory elements of regional water policy.

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) are emerging as an additional institutional mechanism in the water sector. According to Gaiffe (2023), PPPs can improve the efficiency of water supply and wastewater treatment infrastructure management; however, the success of such projects depends on contract transparency, appropriate risk allocation, and public sector oversight [38]. In regional governance settings, PPPs serve as a tool for infrastructure modernization, enabling the attraction of technologies and capital unavailable to budgetary organizations.

A crucial part of the institutional model are administrative and regulatory instruments: water use licensing, discharge permits, water quotas, quality standards, and tariff decisions. Bakker (2014) notes that the effectiveness of administrative instruments directly depends on data availability, procedural transparency, and the institutional discipline of regional authorities [39]. Furthermore, modern approaches involve the introduction of economic regulators, such as tariffs, water taxes, market mechanisms for resource allocation, and incentives for water conservation.

Building on the theoretical role of digitalization discussed above, recent studies emphasize that information systems and digital technologies that enable water quality monitoring, discharge control, water balance analysis, and treatment plant load forecasting. According to Song et al. (2014), digitalization increases the transparency of decision-making and reduces the risk of errors, especially when working with large volumes of data [40]. At the regional level, the implementation of remote monitoring methods, IoT sensors, geographic information systems, and predictive analysis algorithms is becoming the foundation of modern water governance.

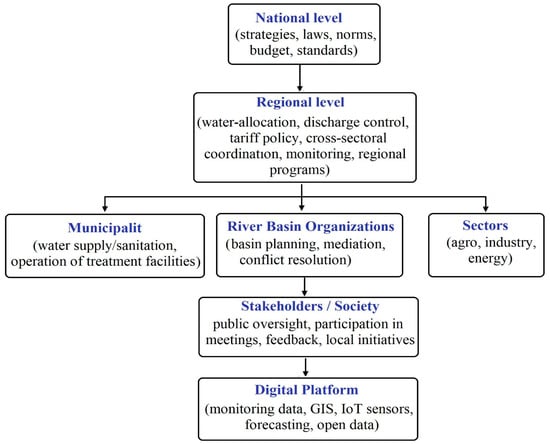

The conceptual structure of all levels of management is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of regional water resources management.

The diagram depicts the relationships between governance levels (national, regional, and municipal), basin organizations, sectors, and stakeholders. The bottom of the diagram shows the role of the digital platform as the primary tool for modern monitoring and transparency. The figure illustrates the systemic nature of the institutional architecture described in Section 3.

Thus, the institutional architecture of regional water resources regulation is a multi-level system in which the interests of multiple actors and policies intersect. Governance effectiveness is determined by the extent to which these elements are integrated, coordinated, and supported by mechanisms for participation, transparency, and digitalization.

2.3. Institutional Barriers and Success Factors

Despite the development of modern approaches, regional water resources management systems face a wide range of institutional barriers. In many countries, these barriers lead to chronic water shortages, degradation of aquatic ecosystems, declining water supply quality, excessive losses during water transportation, and ineffective treatment facilities.

The main barriers and international approaches to overcoming them are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Barriers and effective measures to overcome them.

The table systematizes the main institutional obstacles identified in the studies (fragmentation of powers, data shortages, weak coordination, financial constraints, etc.) and compares them with international examples of successful reforms.

One key barrier is the fragmentation of authority. Moss (2012) points out that water systems are often managed by multiple agencies, each with its own goals and priorities, leading to a lack of coherence and reduced management effectiveness [41]. Regional authorities face conflicting demands from various sectors, which is especially noticeable in the context of competition for resources.

Another significant barrier is the lack of interagency coordination. Cash et al. (2006) demonstrated that insufficient integration between governance levels leads to “scale mismatches,” when policy decisions are made at one level, but the consequences manifest themselves at another [42]. This is particularly true in regions where river and aquifer management requires the integration of administrative boundaries and hydrographic systems.

Lack of transparency and the risk of corruption pose significant obstacles to sustainable management. An assessment of governance systems conducted by Transparency International and confirmed by research by Peiffer and Alvarez (2016) shows that the water sector is considered vulnerable to corrupt practices due to the large volume of infrastructure projects, permit allocation, and tariff decisions [43]. At the regional level, this leads to inefficient use of resources and decreased public trust.

An equally important problem is insufficient funding. Foster and Briceño-Garmendia (2010) note that regional budgets in many countries are unable to support infrastructure modernization and the sustainable operation of wastewater treatment systems [44]. This funding shortfall leads to deterioration of networks, low energy efficiency of treatment facilities, and delays in the implementation of innovations.

Barriers also include a lack of data and a low level of digitalization. Allan et al. (2019) emphasize that the lack of reliable data on water balances, wastewater discharges, and the dynamics of aquatic ecosystems hinders forecasting and strategic planning [45]. At the regional level, this leads to errors in water consumption calculations, ineffective investments, and an inability to respond to changes in a timely manner.

At the same time, international practice demonstrates a number of factors that contribute to the successful reform of regional water resources management. First, multi-level governance, in which national and regional structures act in a coordinated manner, enhances adaptability and ensures the distribution of powers in accordance with the scale of the problem. Second, stakeholder engagement increases the social sustainability of solutions and reduces conflict. Third, digitalization and the implementation of monitoring systems make it possible to create a transparent control system, reduce losses, and improve the accuracy of forecasts. Finally, successful models are characterized by effective economic mechanisms that combine tariff policies, investment instruments, and market approaches that stimulate responsible water use.

Thus, institutional barriers to effective regional water resource management can only be overcome through the development of multi-level coordination, increased transparency, infrastructure modernization, and digital transformation. International experience confirms that institutional models focused on systemic integration ensure high resilience of water systems and their adaptation to future challenges.

3. Strategic Water Resources Management at the Regional Level

Strategic water resources management at the regional level is a multi-level and dynamic process in which long-term planning, climate change adaptation, infrastructure modernization, inter-municipal coordination, and digital transformation form a unified framework for sustainable management [46,47,48]. Unlike traditional administrative approaches focused on regulating current consumption and the operation of water supply and sanitation systems, modern regional water policy is built around a strategic vision based on the integration of environmental, social, technological, and economic factors. Regions are increasingly becoming key platforms for implementing management strategies, as it is at this level that the interests of various water users intersect, investment priorities are formed, and operational interaction between the state, municipalities, and society is ensured [49,50].

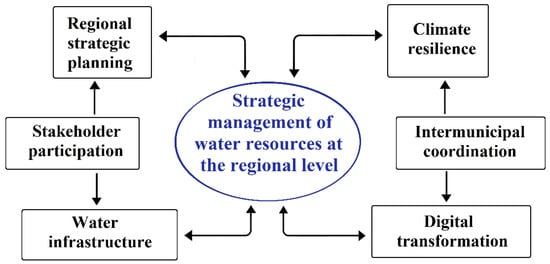

The main components of the regional strategy are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework for strategic management of water resources at the regional level.

Figure 2 illustrates the integration of regional strategic planning, climate resilience measures, intermunicipal coordination, digital transformation, modernization of water infrastructure, and stakeholder participation into a unified governance model.

Regional strategic water resource planning is based on long-term development scenarios, environmental risk assessments, water consumption forecasts, and infrastructure condition analysis. This is based on multi-year regional water plans, which include assessments of surface and groundwater resources, identification of scarcity zones, evaluation of demographic trends, and planning for the future needs of various economic sectors.

The study by Gain and Giupponi (2014) emphasizes the importance of integrating climate, social, and economic scenarios into regional strategies, as traditional linear planning methods are unable to account for the uncertainty of the future state of water systems [51]. Strategic planning allows regions to formulate priorities focused not only on ensuring current water supply but also on preventing crises, optimizing resource use, supporting ecosystem services, and strengthening social resilience.

Climate resilience occupies a special place in strategic management, as climate change is becoming one of the most significant factors affecting the water balance of regions. Increasing drought frequency, changing precipitation patterns, rising temperatures, and more frequent extreme hydrometeorological events are increasing the stress on water systems and infrastructure.

According to a research team led by Kundzewicz et al. (2018), regional water systems are particularly vulnerable to climate change due to their dependence on local water sources and limited reserve capacity [52]. Therefore, strategic management includes the implementation of adaptation measures, such as the development of water-saving technologies, diversification of water supply sources, strengthening the protective functions of ecosystems, the creation of flexible reservoir management, optimization of water supply regimes, and the modernization of early warning systems. Of particular importance is the integration of adaptation measures into regional development strategies, which helps reduce the vulnerability of the population, agriculture and industry to climate stress.

Climate-resilient management is impossible without modernizing water infrastructure, as most regions face physical and functional deterioration. According to Gleick et al. (2011), much of the world’s water supply and wastewater treatment infrastructure was built several decades ago and does not meet modern requirements for sustainability, energy efficiency, and environmental safety [53].

This infrastructure requires not only reconstruction but also a strategic rethinking, including a transition to “smart” water supply systems that utilize automated sensors, intelligent consumption forecasting models, purified water reuse units, energy-efficient membrane technologies, and nature-based wastewater treatment solutions. Regional infrastructure modernization programs are becoming key elements of strategic management, as they help reduce water losses, improve service quality, and ensure compliance with environmental standards. The integration of regional investment programs with national and international sustainable development initiatives is particularly important here.

Inter-municipal cooperation is another essential element of strategic management, as water systems often have a transboundary nature even within a single country. Municipalities may be located within the same watershed, share water sources, or discharge wastewater into the same river, but their management capabilities vary significantly.

A study by Koontz and Newig (2014) shows that fragmented responsibilities between municipalities leads to conflicts, incoordination of measures, inefficient resource allocation, and the inability to comprehensively address environmental issues [54]. Therefore, strategic management requires the creation of inter-municipal coordination bodies, the development of joint management plans, the integration of water management programs, data exchange, the harmonization of tariff policies, and the implementation of principles of collective responsibility for water resources. Such cooperation facilitates the development of unified strategic decisions for the entire region, improves the efficient use of infrastructure, and reduces the risk of water conflicts.

Digitalization has become a fundamental pillar of modern strategic water resource management at the regional level. The development of monitoring technologies, geographic information systems, automated management platforms, and AI-based analytical tools creates new opportunities for predicting water regimes, optimizing production processes, monitoring water quality, and increasing the transparency of management decisions.

According to O’Donnell et al. (2019), regions actively implementing digital solutions demonstrate higher management performance, a better risk response, and greater planning capacity under uncertainty [55]. Digital platforms enable the integration of data on water consumption, climate, infrastructure conditions, and wastewater quality, providing a unified decision-making system for both government agencies and utilities. Data openness is becoming an important element of digitalization, facilitating public engagement, increasing trust, and implementing sustainable management principles.

Thus, strategic water resources management at the regional level is a comprehensive process that integrates long-term planning, climate adaptation, infrastructure modernization, inter-municipal coordination, and digital transformation. These elements do not exist in isolation, but rather form a unified management system capable of adapting to future challenges, ensuring the sustainability of water resources, and supporting the socioeconomic development of regions. Strategic management is becoming a key foundation for the development of sustainable regional water systems, as it utilizes scientifically sound methods, innovative technologies, and the shared responsibility of all levels of government and stakeholders.

4. Wastewater Treatment Technological Solutions: Modern Approaches and Prospects

Technological development in wastewater treatment has acquired strategic importance in recent decades in the face of increasing urbanization, climate change, and increasingly stringent environmental regulations. Water treatment systems are gradually shifting from a linear “clean and discharge” model to a cyclical approach based on resource recovery, reduced energy costs, the integration of digital systems, and the use of natural purification mechanisms. The modern water industry views wastewater not as a waste, but as a source of resources—energy, nutrients, heat, and purified water suitable for reuse. This is driving the development of the industry’s technological landscape, which combines traditional methods with biological, membrane, nature-based, and energy-efficient solutions.

Traditional physicochemical and biological treatment methods, such as coagulation, sedimentation, aeration, and activated sludge, continue to play an important role due to their proven effectiveness, adaptability, and scalability. Activated sludge-based biological treatment remains the primary method for removing organic contaminants, nitrogen, and phosphorus, as it combines high efficiency and relative cost-effectiveness. According to Metcalf & Eddy (2014), biological treatment processes, when properly controlled, ensure stable removal of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), and nutrients and remain the foundation for integrating new technologies [56]. Traditional methods also remain in demand due to their resilience to fluctuations in wastewater composition, which is especially important for small and medium-sized treatment plants.

Advances in biological technology have led to the development of more advanced systems, including membrane bioreactors (MBRs), nitrification-denitrification with short-term nitrification, and new-generation anaerobic reactors. Research by Judd (2016) shows that membrane bioreactors provide significantly higher quality treated water and system compactness compared to traditional activated sludge technologies, making them suitable for densely populated urban areas [57]. Anaerobic membrane bioreactors (AnMBRs) are considered a promising technology capable of combining highly efficient biological treatment with simultaneous biogas production, reduced sludge formation, and reduced energy consumption. Robles et al. (2020) highlights their potential as a key technology pathway for the transition to low-carbon treatment systems [58].

From a policy and planning perspective, the adoption of membrane-based technologies requires careful consideration of capital and operational costs, as well as capacity requirements. Studies indicate that membrane bioreactor (MBR) systems typically involve higher capital expenditures than conventional activated sludge systems, largely due to membrane modules and control infrastructure, while operational costs are driven by energy demand for aeration and membrane fouling control. Anaerobic membrane bioreactors (AnMBRs), although offering energy recovery through biogas production, require stable influent conditions and sufficiently large treatment capacities to achieve economic viability. Reverse osmosis and advanced membrane processes, while highly effective for removing dissolved salts and micropollutants, are generally associated with high energy consumption and concentrate management costs, limiting their applicability primarily to water-scarce regions, industrial reuse schemes, or high-value applications. Consequently, the feasibility of these technologies at the regional level depends not only on treatment performance but also on scale, energy prices, tariff structures, and access to long-term financing mechanisms [57,58,59].

Membrane technologies have become an essential component of modern water treatment systems, performing filtration, ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis functions. Their primary advantage is the ability to effectively remove a wide range of contaminants, including dissolved salts, micropollutants, pharmaceuticals, hormones, and chemically resistant substances. Modern membranes feature improved materials, increased resistance to fouling, and the ability to be chemically regenerated. According to Marchetti et al. (2019), new nanocomposite membranes based on graphene oxide and carbon nanomaterials offer higher performance and resistance to biofouling, making them particularly promising for water-stressed areas [59]. The expanding use of membrane technologies is also associated with their compatibility with digital monitoring systems, which allow for the optimization of operating modes and the prevention of fouling.

One of the key areas of innovation is nature-like water purification methods based on the use of natural processes of filtration, biodegradation, sorption, and phytoremediation. Such systems include artificial wetlands, bioplateaus, filtration channels, and soil filtration structures. A study by Vymazal (2018) shows that artificial wetland systems can effectively remove not only organic matter and nutrients, but also pharmaceutical pollutants and persistent organic compounds [60].

Their environmental sustainability, low energy consumption, and ability to provide associated ecosystem services make such solutions particularly attractive for rural regions and small communities. Nature-like methods are becoming important elements of urban green infrastructure, enabling the integration of water resource management into urban planning. An important area of research is the use of agro-industrial waste as a raw material for producing environmentally friendly sorbents. For example, Kudaibergenov et al. (2013) studied rice husk ash as an affordable and effective sorbent for removing oil spills, demonstrating its high sorption capacity and potential for scaling up such solutions within a circular economy [61].

Another area of focus is the development of sorption technologies, redox processes, and adsorption-catalytic methods. New research also demonstrates the high efficiency of functionalized carbon materials in removing organic contaminants, which is associated with the enhancement of surface acid-base sites. For example, Shen et al. (2015) demonstrated that sulfonation of graphene nanosheets significantly alters their acid–base surface structure and enhances adsorption capacity toward heavy-metal ions, which opens perspectives for advanced adsorbent applications [62].

Recent studies further confirm the high potential of advanced sorption materials for wastewater treatment, particularly for the removal of organic pollutants, dyes, and oil-related contaminants. Functionalized clay-based sorbents and carbon-derived nanomaterials modified with magnetic or catalytic components demonstrate high adsorption capacity, selectivity, and reusability, which are essential for sustainable and resource-efficient treatment systems. For instance, modified natural bentonites and magnetic clays have shown enhanced removal efficiency due to improved surface properties and facilitated separation from treated water. In addition, advanced sorbents based on graphene derivatives and magnetic nanomaterials enable efficient oil–water separation and repeated regeneration, supporting their application in cyclic and large-scale wastewater treatment processes [63,64,65].

The emergence of new sorbents based on nanomaterials, biopolymers, organomineral composites, and functionalized cellulose expands the possibilities for removing heavy metals, dyes, pharmaceutical compounds, and persistent organic pollutants. In addition to high-tech composites, readily available porous sorbents of natural origin are of practical value. In particular, the research of Ongarbayev et al. (2015) demonstrate the high efficiency of Kazakhstani porous sorbents for removing oil products from water surfaces, highlighting the potential of regional developments for application in local treatment systems in oil and gas regions [66].

Research by Baig et al. (2019) demonstrates that nanocomposites based on modified graphene possess high sorption capacity and potential for sorbent regeneration, making them applicable for cyclic treatment systems [67]. Similarly, photocatalytic methods based on modified TiO2, which effectively destroy persistent organic pollutants under the influence of UV or sunlight, are promising, as demonstrated by Irfan et al. (2022) [68].

The concept of resource recovery plays a special role in the development of modern water treatment systems. Within the framework of this paradigm, wastewater is considered as a source of energy, heat, nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) and purified water suitable for reuse in industry or agriculture. The study by Guest et al. (2009) notes that the integration of biological treatment processes, anaerobic digestion, membrane technologies and nutrient recovery can significantly increase the efficiency of treatment plants and reduce their carbon footprint [69,70,71]. An important area is also the precipitation of phosphorus in the form of struvite (MgNH4PO4 6H2O), which can be used as a fertilizer, which is confirmed by the results of the work of Le Corre et al. (2009) [72].

Modern wastewater treatment plants are gradually becoming energy neutral through the implementation of energy recovery and energy optimization technologies. A study by McCarty et al. (2011) demonstrates that anaerobic processes can generate energy in the form of biogas, offsetting or exceeding the energy consumption of treatment [73]. Additional areas of focus include improving the energy efficiency of aeration and implementing intelligent control systems that optimize air supply and reduce costs. Digital technologies, such as machine learning models and IoT sensors, enable real-time monitoring of key treatment parameters, significantly improving operational efficiency. The application of digital optimization in wastewater treatment plants is described in a study by Wan et al. (2024), which demonstrates that intelligent control models can reduce energy consumption by 10–25% [74].

Prospects for further development of wastewater treatment technologies are linked to the integration of multicomponent systems that combine biological, membrane, catalytic, sorption, and nature-based solutions into a single modular platform. Such hybrid systems can more effectively remove a variety of pollutants, adapt to changing wastewater composition, and ensure high levels of resource recovery. A study by Awashi et al. (2025) emphasizes that hybrid systems based on membranes and biological processes provide higher levels of micropollutant removal with lower energy consumption [75]. Thus, technological development in the industry is aimed at creating integrated, sustainable, modular, and energy-efficient systems that meet the challenges of the future.

5. Comparative Analysis of Regional Management Models

Comparative analysis of regional water resources management reveals substantial differences in governance structures, decision-making mechanisms, and implementation effectiveness across regions. While centralized models often provide stronger regulatory control and uniform policy enforcement, decentralized and participatory approaches tend to enhance local adaptability, stakeholder engagement, and long-term sustainability. These contrasting models reflect region-specific socio-economic conditions, institutional capacities, and policy priorities, highlighting the need for context-sensitive management strategies rather than uniform solutions.

One key difference is the degree of institutional autonomy enjoyed by regions. For example, EU countries widely apply the basin-based management principle enshrined in the Water Framework Directive (Directive 2000/60/EC), where regions have autonomy in developing river basin management plans, with basin agencies serving as the key institutions. This approach ensures horizontal coordination between sectors and municipalities, which is especially important for transboundary basins.

In Nordic countries, including Denmark and Sweden, regional water councils actively involve farmer associations, energy companies, and environmental organizations, integrating co-management principles [76]. In contrast, in Central Asian countries, including Kazakhstan, the institutional structure remains largely centralized: key decisions are made at the national level, with regional bodies acting as implementers, which limits the flexibility of governance mechanisms [77]. However, here too, there is a move toward basin-based management: a system of basin inspections has been established, and the adoption of new water security strategies implies greater regional autonomy. In contrast, sectoral governance dominates in Middle Eastern countries, where water supply, agriculture, and the environment are regulated by different agencies, reducing policy coherence [78].

In Latin America, the institutional landscape is even more diverse: Chile is characterized by a high degree of privatization and market mechanisms for water allocation, while Brazil relies on public basin committees and public participation [79].

Thus, institutional differences between regions determine the variability of strategies, coordination mechanisms, and conflict management, as well as the ability to adapt to climate change and socioeconomic challenges.

Technological differences between regions reflect the level of economic development, the availability of modern engineering solutions, the degree of digitalization, and the sustainability of water infrastructure. Countries in Western Europe and North America are actively implementing closed-loop water technologies, membrane bioreactors (MBRs), next-generation anaerobic digesters, IoT-based water quality monitoring systems, and digital twins of water networks [80].

The Netherlands, for example, is implementing large-scale projects to transform traditional wastewater treatment plants into “resource factories” that extract nutrients, heat, and biogas [81].

In Israel and Singapore, the technological focus has shifted toward large-scale reverse osmosis wastewater treatment for reuse: Israel reuses up to 85% of treated agricultural wastewater, one of the highest rates in the world [82].

East Asian countries such as South Korea and Japan are actively implementing intelligent water management systems, predictive models, and energy-efficient aeration technologies. Meanwhile, resource-limited regions such as South Asia, Central Asia, and Africa demonstrate a more fragmented adoption of innovation. Nature-based solutions predominate here: artificial swamps, soil filtration systems, local bioreactors, and low-cost sorbents based on agricultural waste [60]. Of particular interest are developments in Kazakhstan: porous sorbents for the removal of oil products [66] and biosorbents from rice husk ash [61], demonstrating the potential of locally produced materials. Such solutions could be key for regions with limited budgets, reducing the burden on municipal systems.

In Latin American countries, wastewater treatment technologies combine green infrastructure and membrane systems, but access to high-tech solutions is limited by budgets and maintenance. South Africa and Egypt are developing solar desalination technologies and wastewater-based bioenergy plants as part of their climate adaptation strategies [83].

Thus, technological differences between regions reflect not only the level of economic development but also strategic priorities related to climate adaptation, food security, and reducing environmental impacts.

Key factors for the success of regional water management models combine institutional and technological components, forming an integrated approach to ensuring water security. One of the most significant factors is the existence of a sustainable multi-level governance system, where strategic planning is linked to operational management, and regional bodies possess effective authority and resources.

According to the OECD (2020), regions with a clear distribution of competencies, coordination across sectors, and sustainable financing mechanisms achieve better water management results [84]. A second factor is the ability of regions to implement innovative technologies, adapting them to local conditions. Successful examples demonstrate that technological modernization must be accompanied by institutional reforms, otherwise the potential for innovation remains limited. Thus, research by Schellenberg et al. (2021) shows that the transition to resource-oriented technologies requires not only infrastructure modernization but also changes in the regulatory environment and improved skills for wastewater treatment plant operators [85]. A third factor is stakeholder participation: farmers, businesses, municipalities, environmental organizations, and local communities.

Global experience shows that regions with public participation mechanisms, such as public councils or basin committees, achieve greater decision-making consistency and a higher level of trust in water policy. For example, Canada has active Watershed Boards with the participation of all stakeholders, which significantly improves management effectiveness [86]. The fourth factor is the availability of sustainable financial mechanisms: regional water infrastructure funds, public–private partnerships, water user fees, and investment programs.

Countries with continuous funding demonstrate higher rates of technology adoption and infrastructure maintenance. Finally, a key success factor is the ability of regions to adapt to climate change. Regions where regional strategies are aligned with climate scenarios respond more quickly to droughts, floods, and seasonal fluctuations, as confirmed by research by Garnier et al. [87].

Thus, successful regional models combine institutional maturity, technological flexibility, sustainable financing mechanisms, stakeholder participation, and climate adaptation. The closer the alignment of these components, the higher the resilience of water systems and the effectiveness of strategic management. To synthesize these differences across regions, Table 5 provides a comparative analysis of key regional water resources management models, structured around institutional architecture, technological priorities, and outcome-based performance and vulnerability indicators.

Table 5.

Comparative analysis of regional water governance models (institutional, technological, outcome-based).

This table presents a comparative analysis of key regional water resources management models, based on three comprehensive criteria: institutional architecture, technological priorities, and combined performance and vulnerability indicators. The table includes countries and regions reflecting a wide range of global strategies—from highly integrated and technologically advanced systems (the EU, Scandinavia, Israel, and Singapore) to models operating in resource-constrained environments or highly vulnerable to climate change (North America and Central Asia, including Kazakhstan).

A comparative analysis shows that differences between regional water governance models are driven primarily by institutional maturity, financing capacity, and the degree of integration between governance levels. While technologically intensive and centralized models demonstrate high performance, they often require substantial financial and energy inputs, whereas decentralized and nature-based approaches offer greater affordability but face limitations in scalability and regulatory consistency.

European countries, primarily EU members and Nordic countries, demonstrate a high degree of institutional integration built around a basin approach and stakeholder participation. The presence of basin agencies, public water councils, and the regulatory framework established by the Water Framework Directive create a model in which coordination between sectors and municipalities is not the exception but the norm. This ensures management flexibility, high transparency, and the possibility of long-term strategic planning. At the same time, the high cost of implementing innovative technologies and the complexity of administrative procedures can slow the practical implementation of reforms. Countries focused on technological innovation, such as Israel and Singapore, demonstrate a different type of institutional configuration: strong centralization and integration of water policy are complemented by the large-scale implementation of high-tech solutions—membrane systems, multi-stage filtration, desalination, and intelligent monitoring. These countries are shaping a model in which sustainability is achieved through technological modernization and significant capital investment. However, the high energy and cost of such systems limit their applicability in resource-constrained regions.

The North American model is characterized by a multi-level governance structure, where federal, regional, and municipal authorities share responsibility. Watershed boards and public–private partnerships ensure a high level of innovation and flexibility. However, the fragmentation of the regulatory environment creates risks of inconsistency and heterogeneity in water policy.

Latin America and South Asia represent examples of mixed models, where the institutional structure develops under socioeconomic constraints. Brazil has a system of basin committees with active civil society participation, ensuring a high level of social control. At the same time, weak infrastructure and a lack of funding limit the implementation of innovative technologies. In South Asian countries, including India and Bangladesh, low-cost, nature-based solutions prevail, which compensate for the lack of centralized infrastructure but increase the vulnerability of systems to pollution and climate risks.

Central Asia and Kazakhstan occupy a special place. Here, the institutional system remains predominantly centralized, with regional bodies acting as executors of decisions made at the national level. However, trends in recent years indicate a gradual transition toward basin-based management and increased interregional coordination. At the technological level, Kazakhstan demonstrates potential for local innovation: the development of sorbents based on rice husk ash, porous materials for the treatment of oil-contaminated water, and nature-like local filtration systems. These solutions are well adapted to the country’s economic conditions and have significant scalability potential.

Analysis shows that successful governance models combine three key components:

Institutional resilience, expressed in a clear distribution of authority, coordination mechanisms, and stakeholder participation;

Technological flexibility, allowing for the adaptation of innovations to local conditions;

Sustainable financial mechanisms that ensure the continued modernization of infrastructure.

Regions that successfully integrate these elements demonstrate greater resilience in their water systems, adapt better to climate risks, and provide more efficient water supply to their populations and economies.

Overall, the comparative analysis emphasizes that there is no universal model applicable to every region. Each country develops its own configuration at the intersection of historical institutions, technological maturity, available resources, and political priorities. However, the lessons learned show that a combination of a basin-wide approach, inter-municipal coordination, digitalization, and nature-based solutions is the most promising trajectory for most regions, including Kazakhstan.

6. Challenges and Future Prospects

Regional water resources management models are shaped by historical conditions, institutional maturity, legal frameworks, and the level of local stakeholder participation. Despite common global challenges, regional trajectories are evolving differently—from centralized state-administrative systems to flexible, decentralized structures focused on local community participation and inter-municipal cooperation.

Modern water and wastewater management faces a number of interrelated challenges, which are particularly acute at the regional level. The first major set of problems relates to climate and hydrological uncertainty. The increasing frequency and intensity of extreme events—floods, droughts, heat waves—makes traditional water infrastructure planning and operation models insufficiently reliable: design standards focused on “average” conditions no longer guarantee the required level of safety and service. Recent reviews show that climate change impacts all elements of urban water infrastructure—from water supply sources to sewerage systems and treatment plants—requiring a transition to risk-based and adaptive planning strategies over 20- to 50-year time horizons [88].

For regions with continental and extreme continental climates, this means reconsidering water storage regimes, interbasin transfer rules, and allocation priorities in the face of competing demands.

An equally serious set of challenges relates to the financing and institutional sustainability of infrastructure. Even in middle-income countries, chronic underinvestment leads to aging networks, high water losses, and declining treatment plant efficiency; regions and municipalities often lack sufficient access to long-term financing or stable local revenues. An analysis of water infrastructure development in Asia has shown that subnational levels of governance are particularly vulnerable: they are responsible for operations but have limited access to tax and borrowing instruments, and investment decisions are often fragmented across multiple agencies [89].

In developing countries, the issue is exacerbated by a lack of high-quality public–private partnership (PPP) mechanisms and regulatory uncertainty: the example of Zimbabwe shows that even with investor interest, the lack of a transparent financial framework and sustainable tariff policy undermines the implementation of water supply and sanitation projects [90]. At the same time, international development projects implemented in Kazakhstan indicate that institutional capacity-building and phased financing models can deliver tangible results at the regional level, particularly when investment programs are combined with regulatory reforms and performance monitoring requirements [91].

For regions like Kazakhstan’s, the key challenge is developing reliable, predictable financial mechanisms that combine budgetary resources, loans, and public–private partnerships, with strict alignment with regional development strategies.

Technological challenges are increasingly determined by the complexity of wastewater composition and the need to transition from a linear to a circular model. In most countries, treatment systems were historically designed to remove organics and nutrients, while today wastewater consistently contains pharmaceuticals, hormones, personal care products, and other “emerging pollutants.” A review of South Africa shows that dozens of pharmaceutical compounds are regularly detected in wastewater and natural waters at concentrations ranging from ng/L to µg/L, yet the regulatory framework and technologies for their removal remain fragmented [92].

At the same time, the agenda for reusing treated wastewater and recovering resources (nitrogen, phosphorus, organic matter, and energy) is developing, but countries face regulatory and institutional barriers. An analysis of the implementation of the EU Regulation 2020/741 on wastewater reuse has shown that the alignment of quality standards, the distribution of responsibilities between authorities and the acceptability of risks for the agricultural sector are critical for a circular economy in the water sector [93].

In this context, future development directions are closely linked to the transition to resource-based and circular management models. Proposed models for monitoring resource extraction and the circular economy in the wastewater sector emphasize the need to introduce indicator sets that track not only the degree of treatment but also the return of resources to the economy, as well as the integration of water and energy planning [94].

Critical reviews of sustainable water reuse indicate that the key challenge is aligning technologies (membrane and oxidation processes, nature-like systems), quality standards, economic incentives, and public risk perception [95].

This gap between technological potential and large-scale implementation is particularly evident in the case of advanced nanomaterial-based treatment solutions. Although high-performance superhydrophobic and magnetic nanomaterials demonstrate excellent efficiency for oil–water separation and the removal of organic contaminants, their deployment beyond laboratory and pilot scales remains limited. The main constraints are associated with regulatory uncertainty, cost-effectiveness at scale, the absence of standardized performance criteria, and insufficient institutional capacity to support technology transfer at the regional level. As a result, highly effective treatment solutions may coexist with persistent pollution challenges, especially in regions where governance frameworks and investment mechanisms are not aligned with technological innovation [96,97].

At the regional level, this requires a shift from isolated projects to strategic circular water management programs, where goals for water abstraction reduction, reuse, and resource restoration are integrated into long-term regional development plans.

A separate set of prospects relates to digitalization and the development of analytical tools for decision support. A review of digital twin applications in the water sector shows that virtual modeling of water supply, sanitation, and treatment systems, combined with real-world data flows, creates the conditions for scenario analysis, predictive management, and optimization of infrastructure operation modes [98].

However, for resource-limited regions, issues of data interoperability, sustainable financing of digital platforms, and capacity building at the water management organization level remain unresolved. New quantitative approaches to assessing the effectiveness of water policies in large river basins demonstrate that formal indicator frameworks help link policy goals, measures, and actual results, making water management more transparent and accountable [99].

In the future, such tools can be adapted to the needs of subnational administrations and basin councils.

Finally, the strategic direction for future development is linked to the integration of climate adaptation, nature-based solutions, and a cross-sectoral approach. Research at the river basin level shows that the use of nature-based solutions—restoring floodplain ecosystems, creating buffer zones, and constructing multifunctional blue-green infrastructures—can simultaneously increase water security, reduce the burden on wastewater treatment plants, and improve ecosystem health, especially when these measures are integrated into a broader water-food-energy (WEFE) context (e.g., through optimizing the water-ecosystem-food balance using nature-based solutions (NBS)) [100].

For regions experiencing water scarcity and increasing urbanization pressure, a combination of:

- Long-term regional strategic planning based on climate scenarios;

- Circular wastewater treatment technology solutions;

- Digital tools for policy monitoring and evaluation;

- Institutional reforms that strengthen financial sustainability, stakeholder participation, and coordination between levels of government. It is at the intersection of these areas that the agenda for future sustainable water resources management at the regional level is being shaped.

7. Conclusions

Strategic management of water resources and wastewater treatment at the regional level is becoming a key factor in sustainable socioeconomic development in the face of climate change, increasing urbanization, and the increasing complexity of pollutants. The review showed that the effectiveness of water policy is determined not only by technological capabilities, but above all by the institutional architecture, the degree of coordination between government levels, and stakeholder participation. Water systems operating under fragmented regulation and limited financial resources demonstrate lower adaptability and resilience, whereas regions with strong basin structures, transparent decision-making systems, and a developed regulatory framework are able to more quickly implement innovations, ensure high treatment standards, and improve environmental safety.

The technological analysis confirms that the transition to new treatment models—from advanced biological treatment and membrane systems to nature-like, low-cost solutions—is an integral part of a sustainable water management strategy. However, the implementation of such technologies is impossible without the support of institutional mechanisms: quality standards, financing schemes, investor incentives, training programs, and regional planning mechanisms. It is the combination of technological flexibility and institutional maturity that delivers long-term impact, enabling regions to move towards a circular water economy, where wastewater is seen as a source of resources, energy, and new development opportunities.

A comparative analysis of global models has shown that there is no universal solution: each country or region develops its own configuration, reflecting historical management traditions, climatic conditions, economic structure, and technological maturity. However, general patterns can be identified. Successful management systems are characterized by:

- -

- Clearly distributed powers and sustainable mechanisms for interagency coordination;

- -

- The integration of climate scenarios and risk-based approaches into strategic planning;

- -

- The implementation of digital tools for monitoring and performance evaluation;

- -

- Active engagement of the public and water users;

- -

- The transition to a resource-based wastewater treatment model.

These elements form the foundations of adaptive management capable of responding to uncertainty and long-term challenges.

With regard to Kazakhstan and the countries of Central Asia, the review emphasizes that the region possesses significant potential for modernizing the water sector: a scientific base, experience in developing local sorbents and biocomposites, and opportunities for expanding nature-based solutions and digitalization. However, weak decentralization, deteriorating infrastructure, limited financial instruments, and the need for institutional reform remain key barriers. The future of sustainable water resources management in Kazakhstan depends on the consistent strengthening of basin councils, the development of sustainable financing mechanisms, the integration of circular approaches into regional policies, and the expansion of international cooperation on transboundary rivers.

Thus, the regional level is becoming the central platform where strategic planning, technological innovation, and institutional transformation intersect. The resilience of water systems, environmental security, and the ability to adapt to global challenges depend on how successfully regions integrate these components. The review confirms that the development of integrated, digital, climate-resilient, and economically viable governance models is a key path to ensuring water security in the 21st century.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18010063/s1.

Author Contributions