Abstract

The accuracy and timeliness of precipitation inputs have significant impact on flood forecasting. Upstream Minjiang River Basin is characterized by complex terrain and highly variable climatic conditions, posing a significant challenge for runoff forecasting. This study proposes a combined forecasting approach integrating numerical weather prediction (NWP) models with hydrodynamic models to enhance flood process simulation. The most appropriate initial field data for the Weather Research and Forecasting Model (WRF) exist in time and space resolution. Compared with the measured series, the characteristics of precipitation forecasting are summarized from practical and scientific perspectives. InfoWorks ICM is then used to implement runoff generation calculations and flooding processes. The results indicate that the WRF model effectively simulates the spatial distribution and peak timing of precipitation in the upper Minjiang River. The model systematically underestimates both peak rainfall intensity and cumulative precipitation compared to observations. Initial field data with 0.25° spatial resolution and 3 h temporal intervals demonstrate good performance and the 10–14 h forecast period exhibits superior predictive capability in numerical simulations. Updates to elevation and land use conditions yield increased cumulative rainfall estimates, though simulated peaks remain lower than measured values. The runoff results could indicate peak flow but rely on the precipitation inputs.

1. Introduction

Global warming is increasing the frequency of high-intensity rainfall events, resulting in recurrent flash floods, landslides, and mudslides, which pose significant threats to human life, property, and societal stability [1,2,3]. Floods in mountainous regions are often severe and sudden, with severe property loss and human injury.; thus, hydrological forecasting is important for flood control and disaster mitigation [4,5]. Current early warning systems require improvements to local flood prevention initiatives and rely on accurate forecasts from whole watersheds. Extending the forecast period while maintaining the accuracy of the predicted hydrologic process is crucial in modern flood forecasting and early warning strategies.

Due to the complex geological environment in the upper Minjiang River Basin, accurately simulating rain and flood processes is vital for flood mitigation and emergency management. In recent years, numerical weather models from our country and others have been developing rapidly. The mesoscale numerical Weather Research and Forecasting Model (WRF) has been widely used in regional forecast simulations as it can finely capture the local characteristics of meteorological elements [6]. Related studies have shown that the WRF model performs well in simulating extreme precipitation events in different regions. For example, Merino et al. systematically evaluated the hourly results of extreme precipitation events in northeastern Spain, and Zhuge et al. simulated rainstorm area in the Jiangsu region through different microphysical schemes [7,8]. Existing research primarily focuses on analyzing individual precipitation events from a meteorological perspective, but there is still a lack of insufficient studies on the hydrological aspects required for numerical results [9,10]. The accuracy and timeliness of precipitation forecasts are crucial, as they serve as the fundamental driving factors for flooding. A comprehensive assessment of numerical results for precipitation can enhance our understanding of regional precipitation patterns, facilitate the analysis of flooding causes, and enable more accurate predictions. This understanding can provide a solid basis for the allocation of water resources and effective water management.

In addition, few studies have focused on the effects of the impacts of different driving data on WRF performance in the Minjiang River Basin. Urbanization also has an important influence on the simulated surface processes and atmospheric boundary layer characteristics, which further affects rainfall simulation. Therefore, it is also important to analyze the impacts of land use change and urbanization on regional climate models [11,12].

Numerical weather forecasting remains one of the more accurate and reliable methods available for short-term precipitation forecasts. Utilizing forecast precipitation-driven hydrologic models is widely recognized to significantly enhance weather forecast application and improve the timeliness of flood predictions in river basins, especially those with short main confluence times. This approach’s primary strength lies in its ability to provide basin-wide, physically based forecasts days in advance, but its effectiveness is inherently constrained by the uncertainties in quantitative precipitation forecasting (QPF), including errors in the predicted location, intensity, and timing of rainfall events. For instance, Calvetti and Pereira used a WRF prediction-driven Topmodel to simulate flood events in a Brazilian basin, demonstrating that the integration of WRF with Topmodel can extend the lead time for flow predictions [13]. Similarly, Yao et al. utilized a WRF-driven GXM model for flood predictions in Xixian Basin, indicating that WRF predictions enable earlier flood event forecasts [14].

The integration of artificial intelligence and remote sensing has led to significant breakthroughs in flood disaster identification. For instance, deep learning models enhanced with attention mechanisms, such as the Concentration-Based Attention Module (CBAM), are now used for high-accuracy tasks like classifying post-flood damaged houses from dual-view imagery and identifying urban flood depth levels from visual data. These technologies enable rapid, large-scale impact assessment following an event. However, the foundational step for both forecasting and subsequent impact analysis remains the accurate prediction of the precipitation event itself. Therefore, improving the quality of precipitation inputs—by evaluating sources like driving data and land use effects within frameworks like WRF—is a prerequisite for advancing the entire flood management cycle, from early warning to loss estimation.

The upper Minjiang River is characterized by complex channel morphology. In this context, relying solely on precipitation forecasts or traditional hydrological methods is insufficient for operational flood risk management, as they struggle to accurately predict water stages and, more critically, to simulate the dynamic inundation extent and depth during major floods. To bridge this gap and achieve a complete forecast chain—from rainfall prediction to the detailed simulation of the resulting flood process—hydrological modeling support and hydrodynamic modeling support are required. This study employs the advanced 1D–2D coupled hydrodynamic model InfoWorks Integrated Catchment Modelling (ICM) software (version 24.10.43, 64 bit). Developed by Wallingford, it has been widely applied for various tasks, including assessing the performances of existing drainage systems, forecasting and predicting floods, simulating rainfall and runoff control, and evaluating storage design. The core objective of this study is to develop and evaluate a forecasting chain for the upper Minjiang River. First, the sensitivity of WRF-simulated heavy rainfall to different driving datasets and land use scenarios is assessed. The optimized WRF outputs are then used to drive the InfoWorks ICM model to simulate flood hydrographs and inundation patterns. In order to effectively enhance our flood forecasting capabilities, we selected the InfoWorks ICM model, which will provide a more accurate and comprehensive tool for understanding the flood process and assessing damages and impacts.

Therefore, this study simulates five distinct heavy rainfall events in the upper Minjiang River from 2018 to 2022 based on their representation of typical rainfall patterns in the basin and the completeness of observational data for validation. It analyzes the spatial distribution, identifies hourly rainfall variations and errors, and assesses appropriate initial timing conditions. Additionally, this study evaluates the impacts of the underlying surface and urbanization on precipitation simulation, as well as systematically determining the optimal initial field configuration for the study area (ERA5 data with a 0.25° spatial resolution, 3 h temporal intervals, and a 10–14 h forecast lead time). Building on this optimized configuration, high-precision topographic and land use data were updated to enhance the WRF model’s ability to simulate the spatiotemporal distribution of rainfall and the morphology of flood hydrographs, with the InfoWorks ICM model subsequently employed for flood process simulation. By coupling WRF outputs with the InfoWorks ICM model for flood simulations, this research further analyzes the performance of basin runoff forecasts following the updating of rainfall data. In addition, while numerical precipitation forecasts still exhibit systematic underestimation in peak discharge quantification, they demonstrate significant value in improving the correlation of flood hydrographs and extending early warning lead times, ultimately aiming to enhance the effectiveness and accuracy of flood forecasting in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

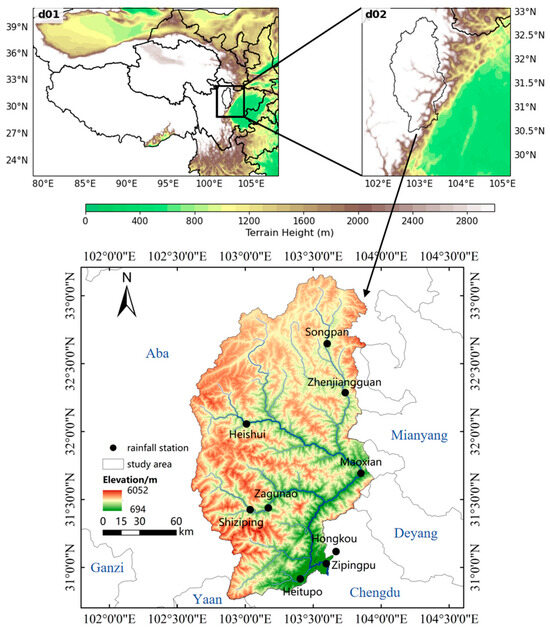

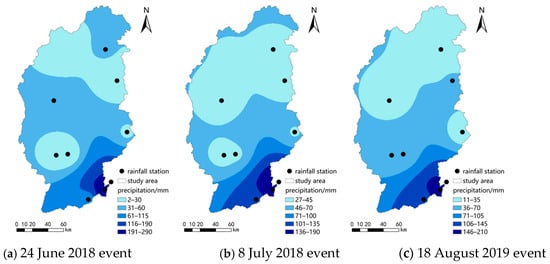

The upper basin of Minjiang River is situated between 102°32′ and ~104°15′ E and between 30°45′ and ~33°09′ N, primarily covering the Aba Autonomous Prefecture. This region exhibits high terrain in the northwest and low elevations in the southeast, featuring a mix of plateau and rivers. This part of Minjiang River is 341 km long, with a watershed area of 22,576 km2. To analyze precipitation in this area, nine rainfall stations were utilized, as depicted in Figure 1. The measured precipitation data were interpolated using the Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) method to illustrate spatial rainfall distribution across the watershed, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

The research area and locations of rainfall stations.

Figure 2.

Distribution of cumulative gaging rainfall. (a) 24 June 2018 event, (b) 8 July 2018 event, (c) 18 August 2019 event, (d) 14 August 2020 event, (e) 22 June 2022 event.

The initial meteorological field of the WRF model was selected from FNL of the National Center for Weather and Environmental Prediction (NCEP) (5830 University Research Court, College Park, MD 20740) and ERA5 of the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) (Shinfield Park, Reading, RG2 9AX, United Kingdom). The data contains wind speed, dew-point temperature, ice cover, relative humidity, and surface air pressure values. Specifically, events occurring in 2018 and 2019 were simulated using the FNL data, which served as a benchmark for operational analysis at the time of this study’s initial design. Subsequently, events from 2020 onward were simulated using ERA5 data, whose multi-decadal consistency makes it a robust foundation for both contemporary analysis and extended climatological studies. A detailed intercomparison of these five events, each simulated with FNL and ERA5 at varying spatial and temporal resolutions, was conducted. The specific configurations for each event and simulation are detailed in Table 1. Simulation experiments were conducted for each precipitation event using both the FNL and ERA5 datasets, with each comprising three datasets. These are distinguished as ID 1 to 6.

Table 1.

Data source and resolution for each event.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. WRF Model

The WRF model, jointly developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) (1850 Table Mesa Drive, Boulder, CO 80305, USA) and the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) (5200 Auth Road, Camp Springs, MD 20746, USA), is a high-resolution, mesoscale numerical weather model. It utilizes the Arakawa-C grid in the horizontal direction and a terrain-following coordinate system in the vertical direction [15,16]. It also uses a Runge–Kutta time integration scheme to solve the non-hydrostatic Euler equations. The WRF model is configured with two nested layers, where d01 and d02 represent the spatial coverage of the first and second layers, respectively. In this study, the simulations are nested in two layers: the first layer (d01) covers the whole Tibetan Plateau and Sichuan Province, with a coarse grid number of 350 × 240 in 9 km, while the second layer (d02) mainly contains the study area, with a fine grid number of 118 × 133 in 3 km and each simulation integration step taking 30 s, as shown in Figure 1.

The simulation performance of the WRF model could be significantly affected by different combinations of physical schemes. In this study, the Lin scheme is used for microphysical processes, the RRTM scheme for long-wave radiation, the Dudhia scheme for short-wave radiation, the YSU scheme for the boundary layer scheme, and the Monin–Obukhov scheme for surface layer parameterization schemes.

For verification metrics, in order to quantitatively analyze the impact of forcing fields with different resolutions on the simulation capability of the WRF model, this study uses two error metrics, the root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE), to evaluate the imported data with different spatial resolutions. The methods for calculating each error are described below:

where Si and Oi are the WRF simulation values and observations on hour i, respectively, and M is the number of simulation values and observations.

2.2.2. InfoWorks ICM

InfoWorks ICM is a highly integrated model that combines drainage networks, river hydraulics, and 2D flood plains. This setup enables multiple modules and processes to be tightly coupled, such as channel and watershed hydrological and hydrodynamic modules. The model comprehensively simulates and analyzes the procedure and effects of water flow across various environments. In this study, hydrologic and hydrodynamic simulations in ICM divided the study area into sub-catchments and simulated runoff generation processes and the flow concentration in each sub-catchment. The Horton infiltration method was used to calculate the runoff yield part, and the kinematic wave method was used for the watershed concentration. One-dimensional river confluence module was computed using the fully solved St. Venant system of equations. When simulating the two-dimensional flood evolution, the Godunov finite volume format was used to solve the following two-dimensional shallow water equations:

where h is the water depth (m), and u and v are the velocities in the x and y directions (m/s), respectively. g is the acceleration due to gravity (m/s2). S0x and Sfx are the bed slope drop and friction slope drop in the x direction, respectively, whereas S0y and Sfy are those in the y direction, respectively.

In this study, InfoWorks ICM contained 112,790 elements. The DEM data were based on the 30 m resolution SRTM DEM downloaded from the Geospatial Data Cloud. The soil data were from the results of the Second National Land Survey and the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD). The land use data were taken from the 30 m resolution land use datasets developed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CNLUCC) (52 Sanlihe Rd., Xicheng District, Beijing, China), and the vegetation data were from the 1:1,000,000 vegetation dataset of China compiled by the Editorial Committee of the Vegetation Map of China, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

2.2.3. Overall Workflow

The overall workflow can be summarized into three main parts: (1) Different initial field data drove the WRF model, which was used to determine the optimum prediction period and background meteorological field data for rainfall simulation. (2) The impacts of underlying change in and urbanization on precipitation were assessed, and rolling merged the rainfall series to enhance the model’s precipitation results. (3) Both the WRF model’s simulated results and observed rainfall–runoff data were used in the InfoWorks ICM model to compare flooding processes.

Importing WRF model outputs into InfoWorks ICM was defined as a standardized multi-step operational procedure. The grid precipitation data simulated by the WRF model were assimilated into the input data required by InfoWorks ICM through a post-processing program. Specifically, Python (version 3.11.8) scripts read WRF output files, performed area-weighted averaging of grid precipitation based on watershed boundaries to generate watershed-level rainfall–runoff time series, and simultaneously extracted precipitation sequences corresponding to key hydrological nodes. Processed data underwent format conversion before being directly imported into the InfoWorks ICM model, serving as the rainfall input to drive runoff simulation.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Different Lead Times on Simulation Results

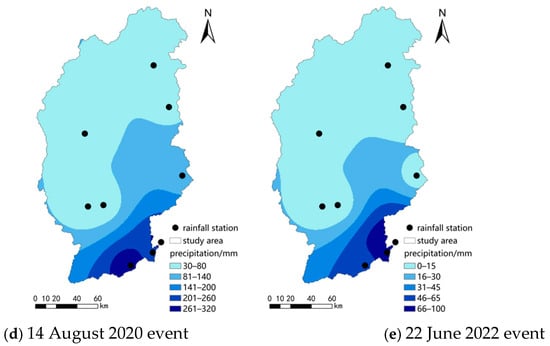

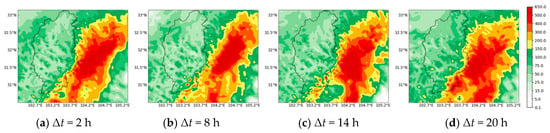

The 0.25° × 0.25°, 3 h ERA5 data with different advance periods (2, 8, 14, and 20 h) was used to simulate precipitation for the 14 August 2020 event. The maximum-point rainfall series was extracted from the WRF precipitation results and analyzed in comparison with corresponding measured data, which are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A comparison of WRF-simulated precipitation with measured data for the 14 August 2020 event.

In the observed series, the first rainfall peak was 22 mm/h at 22:00 on the 16th, and the second was 53 mm/h at 08:00 on the 17th. Only the first peak was simulated when the lead time was 2 h, and there were multiple separate rainfall peaks for a lead time of 8 h. When the lead time was 14 h, two peaks were successfully simulated with delays of only 1 and 2 h. When the lead time was 20 h, three rainfall peaks were simulated, with the total precipitation amount being significantly overestimated.

The rainfall centers simulated by the WRF model under different advance periods basically coincide with the other’s (Figure 4). The maximum total rainfalls for the 2 and 14 h advance periods were 482.35 mm and 495.76, respectively, closest to the actual measurements. This indicates that the advance period significantly influences the accuracy of rainfall process results. The WRF results improve when an appropriate lead time is selected according to the rainfall period; the forecast process markedly deteriorates when this time is too long. Based on the analysis of other rainfall events, field data with an advance period of 10–14 h was identified as the most accurate.

Figure 4.

The accumulated rainfall results of WRF under different foresight periods for the 14 August 2020 event. (a) Δt = 2 h, (b) Δt = 8 h, (c) Δt = 14 h, (d) Δt = 20 h.

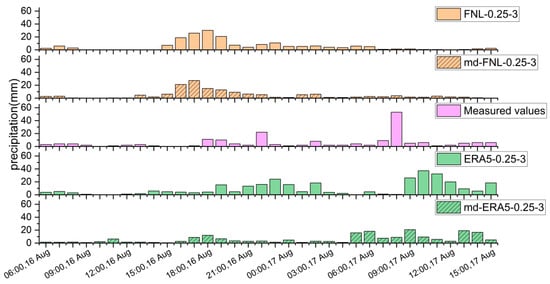

3.2. Effect of Different Spatiotemporal Resolutions

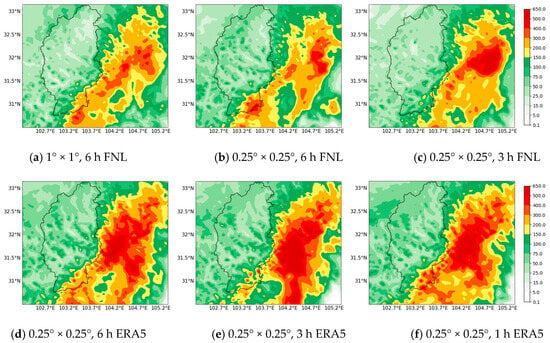

As shown in Table 2, total simulated rainfall at gauging stations is typically lower than the measured values, but precipitation in the center of the rainstorm basin is greater than the measured records. The “Test number” serves as a unique identifier for distinct WRF rainfall simulation experiments conducted under varied data configurations for the same rainfall event. Figure 5 shows the distribution of the cumulative rainfall output of the 14 August 2020 event from the WRF model simulation. Compared to Figure 2d, the rainfall distribution was effectively simulated in the watershed, showing more rainfall in the southeastern area and less in the central and north region, and the storm’s center was situated outside the watershed. The rainfall results of three sets of FNL data exhibit similar distributions. The results also indicate that the ERA5 forcing field generally resulted in more extensive and heavier rainfall than the corresponding FNL data in this watershed.

Table 2.

WRF rainfall extraction table.

Figure 5.

The cumulative rainfall distribution of the 14 August 2020 event. (a) 1° × 1°, 6 h FNL, (b) 0.25° × 0.25°, 6 h FNL, (c) 0.25° × 0.25°, 3 h FNL, (d) 0.25° × 0.25°, 6 h ERA5, (e) 0.25° × 0.25°, 3 h ERA5, (f) 0.25° × 0.25°, 1 h ERA5.

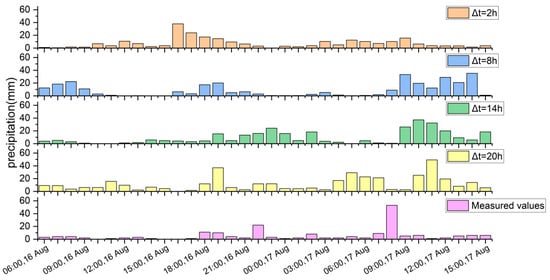

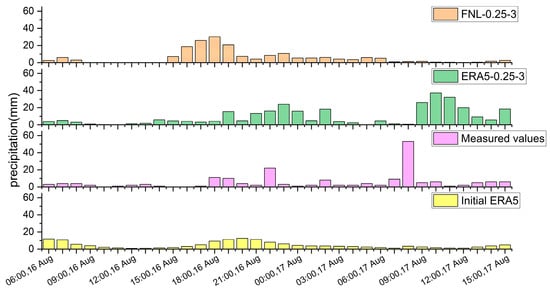

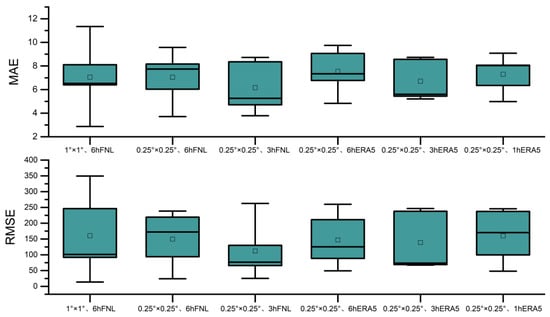

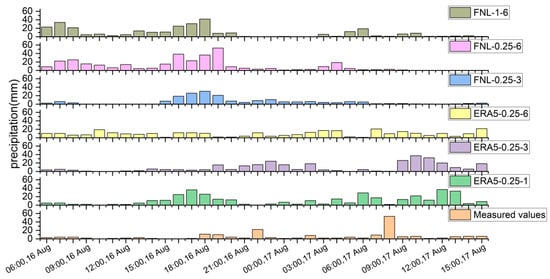

According to the five rainfall events, six sets of data can be used to simulate the emergence of rainfall peaks; however, there is a large uncertainty in peak time and the simulation peak intensity is not sufficiently accurate. Figure 6 illustrates these common challenges with a detailed analysis of the 14 August 2020 event, showing that the value for the hour-by-hour sequence plot of maximum rainfall in the watershed from 6:00 16 August to 15:00 17 August in the first rainfall peak simulated by the 0.25° × 0.25°, 3 h FNL data at this site was 30.19 mm/h, which exceeded the measured peak by 8 mm/h. However, the first peak appeared 5 h earlier and the second rainfall peak was not captured. The 0.25° × 0.25°, 3 h ERA5 data provide a more accurate simulation of the rainfall process and peak occurrence times, with the simulated rainfall peaks measuring 24.16 and 37.14 mm/h, respectively. These values differ from the actual measurements by just 2 and 16 mm/h, respectively, but both simulated peaks occur 1 to 2 h later than the actual observations. The FNL data performed poorly in extreme precipitation simulations, while the ERA5 data performed better. However, from a process point of view, the FNL data are more realistic and easier to obtain, which is important in scenarios such as forecasting the temporal evolution of precipitation events.

Figure 6.

The hourly rainfall process for the 14 August 2020 event.

The average absolute and root mean square errors of the precipitation process were calculated at the watershed’s maximum point, as shown in Figure 7. In the three groups of FNL data, the maximum and minimum errors of the 1° × 1°, 6 h FNL data exhibit significant deviations from the average, and the 0.25° × 0.25°, 6 h FNL data improve, but the errors are still high. Conversely, the 0.25° × 0.25°, 3 h FNL data generally show smaller errors and have a lower mean deviation among the datasets. Among the three sets of ERA5 data, the error distribution for the 0.25° × 0.25°, 3 h ERA5 is more concentrated, yielding the lowest median and mean errors. The 0.25° × 0.25°, 6 h ERA5 data exhibit the widest error range, whereas the global error in the 0.25° × 0.25°, 1 h ERA5 data is on the higher side. Based on the above analysis, the WRF rainfall simulations using 0.25° × 0.25°, 3 h FNL data and 0.25° × 0.25°, 3 h ERA5 data demonstrate superior performances. Simulations employing initial conditions with higher spatial and temporal resolutions yield improved results; however, an excessively high temporal resolution may increase the uncertainty of computational outcomes. Therefore, this study focuses on the precipitation simulation results obtained using data with a resolution of 0.25° and 3 h to extract the fitting results for the rainfall process. This method is applied to test the posterior validity of precipitation simulation in flood forecasting.

Figure 7.

Box plots of mean absolute errors and root-mean-square errors for rainfall centers in the basin.

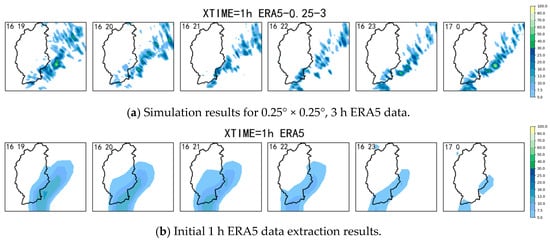

Figure 8a,b show the hour-by-hour rainfall maps generated from the 0.25° × 0.25°, 3 h ERA5 data and initial 1 h ERA5 data for the 14 August 2020 event, covering the period from 19:00 on August 16th to 00:00 on August 17th 2020. The initial ERA5 data exhibited coarser rainfall characteristics, featuring a broader rainfall distribution and lower spatial resolution, which failed to capture fine rainfall distribution changes. Consequently, the rainfall passed over the basin earlier than in the WRF simulation scenario and was less intense than the simulated results. By contrast, the rainfall generated by the WRF model demonstrated a higher spatial resolution and a more detailed distribution, effectively capturing smaller-scale weather features and variations in rainfall. This comparison highlights the advantages of the WRF simulation results in accurately representing the spatial distribution of rainfall and shows that it is currently the more accurate and promising way to acquire forecasting information.

Figure 8.

Hourly rainfall distribution from 19:00 to 0:00 on 16 August 2020. (a) Simulation results for 0.25° × 0.25°, 3 h ERA5 data, (b) Initial 1 h ERA5 data extraction results.

3.3. Effects of Underlying Surface Characteristics and Urbanization

The default DEM of the WRF model uses the 2010 topographic height data and the land use data are based on 2001 MODIS data; both have a 30 s resolution [17,18]. To enhance the accuracy of rainfall forecasting results, the default subsurface data are replaced by the ASTER elevation data with a 30 m resolution from 2013 and MODIS land use data with a 500 m resolution from 2020. As shown in Table 3, after replacement, mixed forest and farmland decreased significantly, broad-leaved forest increased, grassland area increased substantially, and elevation changed marginally.

Table 3.

Main changes in land use and elevation.

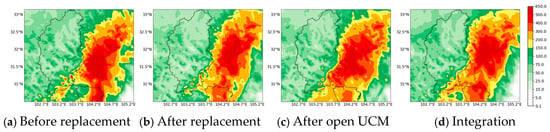

Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the cumulative rainfall distribution and max-point 1 h process of the 14 August 2020 event before and after replacing the elevation and land use data. After these topographic changes, rainfall in the storm center decreased, especially using the ERA5 data. For instance, in the 14 August 2020 event, the decrease in rainfall reached 133 mm, with a cumulative rainfall of 362.07 mm. Based on the observed values from the sites in Table 3, the reduced maximum rainfall within the catchment more closely approximates the measured values. The increased areal rainfall exhibits a smaller deviation from the observed results, and the cumulative rainfall estimates show improvement following the replacement of the underlying surface. Changes in the location of the rain band of the watershed are not clear, but the rainfall center has decreased and the precipitation region has become smaller, which more accurately reflects the actual situation. Figure 10 shows the hourly variation in maximum rainfall under different land surface conditions for the 14 August 2020 event, from 06:00 on the 16th to 15:00 on the 17th. After replacing the land surface conditions, the first peak in the FNL data simulation decreased to 27.21 mm, occurring one hour earlier, while the second peak was not simulated. By contrast, both simulated peaks in the ERA5 data decreased, with multiple rainfall peaks appearing during the latter stages of the event. Analysis of other events indicates that, apart from the 14 August 2020 event where FNL data simulated a slightly higher peak, overall rainfall peaks were generally smaller and below the observed values, with the maximum peak occurring earlier. During the initial rainfall phase, the influence of the land surface on precipitation was minimal; however, as time progressed, the deviation in rainfall levels became more pronounced. This shows that urban development, geological changes and other factors changed the simulated process and rainfall region.

Figure 9.

A comparison of cumulative rainfall distribution before and after the replacement of elevation and land use for the 14 August 2020 event. (a) Before replacement, (b) After replacement, (c) After open UCM, (d) Integration.

Figure 10.

The hourly variation in maximum rainfall in the basin after the replacement of elevation and land use for the 14 August 2020 event.

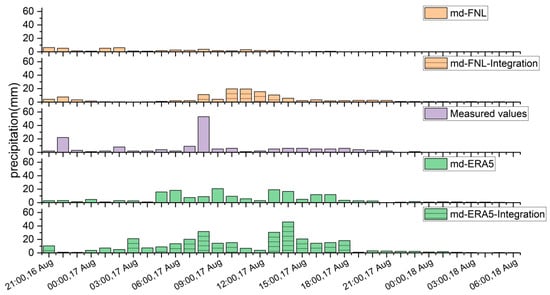

3.4. Integration of Rainfall Processes

In practical applications, the forecasting accuracy decreases sharply for longer time periods. Conversely, by ensuring an advance period of 14 h, the accuracy of predictions can be enhanced by integrating updated rainfall forecast information throughout a longer event. For instance, the rainfall event of 14 August 2020 lasted for a total of 69 h, which was divided into three sections, considering there are 24 h in a day.

The integration of the segmented simulations significantly enhanced the representation of subsequent rainfall peaks, with higher peaks and slight delays in their appearances. This fusion of information expanded the rainfall coverage on the southeastern side of the watershed (see Figure 9), with better rainfall intensity at the storm center. Figure 11 illustrates the hour-by-hour variation in maximum rainfall in the watershed by merging updated rainfall data. The peak rainfall was substantially amplified and improved, with the second simulated rainfall peak occurring 2 h later when using FNL data and occurring 4 h later and increasing by 25 mm when choosing ERA5 data.

Figure 11.

The hourly variation in basin maximum rainfall for the 14 August 2020 event under Integrated Rainfall Scenarios.

3.5. Analysis of Flood Simulation Results

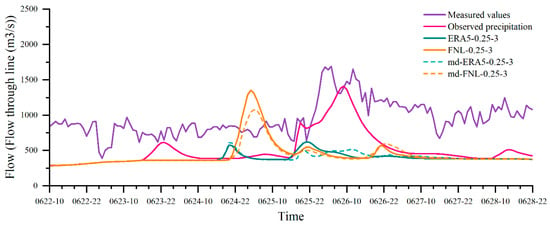

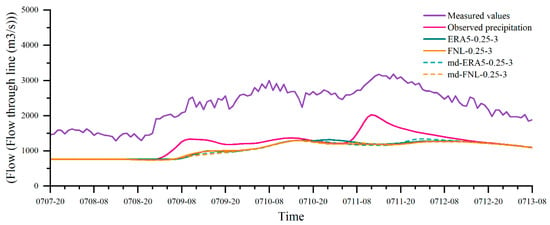

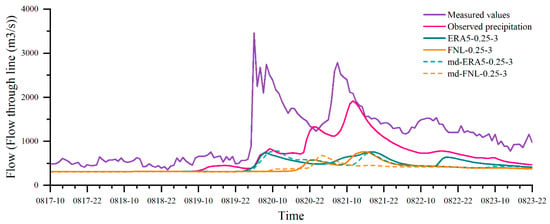

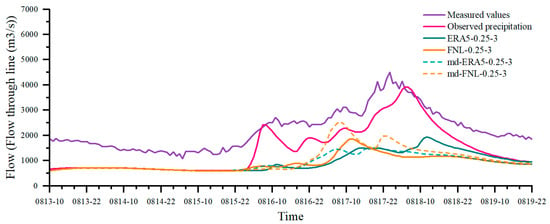

Based on four flood events (the 22 June 2022 event, 8 July 2018 event, 18 August 2019 event, and 14 August 2020 event), we systematically assessed model performance under different data conditions. Under observed-precipitation forcing, the model generally reproduces the overall hydrograph pattern and peak timing, yet it still underestimates peak magnitude. One exception is the 18 August 2019 event, which shows a large peak-time bias (see Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 12.

A comparison of simulated flows for the 22 June 2022 event.

Figure 13.

A comparison of simulated flows for the 8 July 2018 event.

Figure 14.

A comparison of simulated flows for the 18 August 2019 event.

Compared with the observed-precipitation forcing, simulations driven by ERA5 and FNL markedly underestimate peak discharge, and final peak timing errors are often greater than 10 h. After replacing the land surface data, simulations driven by ERA5 and FNL both show improved temporal consistency across the four events. For the 14 August 2020 event (Figure 15), the replaced FNL-driven peak and the secondary increase shift to an earlier time and the peak-magnitude improves, becoming more accurate.

Figure 15.

A comparison of simulated flows for the 14 August 2020 event.

4. Discussion

4.1. Ability of Models to Simulate Precipitation

Precipitation is the main input data for hydrologic and hydrodynamic models [19,20,21]. It directly affects the precision and accuracy of the prediction results. High-quality precipitation with feasible spatial and temporal resolution is essential for flood simulation and forecasting, especially for flash flood forecasting in mountainous areas. In order to obtain high-quality precipitation data for small and medium-sized mountain watersheds, we used the WRF model to generate rainfall data of significantly higher quality. Considering Figure 6 and Figure 8 together, the rainfall process predicted by the initial ERA5 data does not fit well with the actual data. The simulation of rainfall using the WRF model effectively expresses the rainfall magnitude and distribution, which makes the rainfall results more in line with the actual rainfall situation, and enhances the accuracy and practicability of rainfall forecasting [22]. However, the ability to simulate peak rainfall is insufficient, with the predicted intensity varying from the actual intensity. This is often attributable to uncertainties in microphysical parameterizations and the sub-grid representation of convection.

4.2. Appropriate Initial Conditions

The experimental results show that the use of different lead times of initial meteorological field data also has a certain impact on the prediction results of WRF precipitation. When the lead time is 10–14 h, the prediction effect of WRF improves because suitable spin-up times can help the model adjust its own numerical methods and develop appropriate atmospheric circulations [23]. When the lead time exceeds this range, the WRF results begin to exhibit varying degrees of bias and fail to accurately capture precipitation peaks and processes. Overall, the spin-up time of the WRF should not be too short because it is difficult to reach a physical equilibrium state, but it should also not be too long; the optimal time depends on the quality of the weather conditions [24].

With the enhancement of both the spatial and temporal resolution of the input data, the predictive accuracy of the model improved significantly. This indicates that a finer resolution enhances the ability to capture intricate physical processes, thereby optimizing the model’s performance. Specifically, when the WRF model utilized spatial resolution data of 1 degree, the results were suboptimal and failed to accurately reflect the precipitation processes. In contrast, employing spatial resolution data of 0.25 degrees led to simulations that were much more aligned with the observed precipitation patterns, effectively capturing the variations in peak precipitation. Similarly, when considering temporal resolution, the WRF model showed improved results with an analysis frequency of 3 h compared to 1 and 6 h (see Figure 16). In terms of precipitation prediction, simulations using 0.25° and 3 h datasets work best. It is evident that finer spatial and temporal resolutions in the initial data lead to superior simulation outcomes; however, it is important to note that an excessively high temporal resolution may introduce greater uncertainty in the computed results. Specifically, while an increase in resolution enhances precision, there is a threshold beyond which the complexity of and variability in the data can increase the uncertainty in precipitation forecasts, particularly when forecasting over an extended period. Furthermore, an excessively high resolution will substantially increase the requirements for file storage and prolong transfer and download times, thereby adversely affecting practical forecasting operations. Therefore, a balance in both spatial and temporal resolutions is crucial for optimizing the predictive capabilities of the model while minimizing potential uncertainties.

Figure 16.

Hourly rainfall processes at different resolutions for the 14 August 2020 event.

Although the accuracy of precipitation predictions has been improved by finer spatial and temporal resolutions, the accuracy of the results is still affected by a number of factors such as changes in subsurface and urbanization, especially since the study area is in a seismic zone. Land use and elevation changes can alter the albedo, heat capacity, and thermal conductivity of the land surface, thus affecting precipitation characteristics. After replacing the subsurface, the falling area of most of the rainfall and the amount of rainfall decreased, which was especially clear in Wenchuan County. This suggests that urban thermal effects and changes in land surface roughness have a significant impact on the offset of rainfall centers. When the rainfall calendar is long, the uncertainty in the WRF model increases with time and the error in the simulation results increases accordingly. Shao et al. pointed out that the segmented integration method does reduce the cumulative error caused by long integration times, and that the simulation effect of segmented integration is better when the error in the analyzed information is smaller, the more updated variables there are, and the shorter the time interval between segments [25]. Analysis of the integrated segmented simulation results reveals significant improvement in the simulation of the peaks.

4.3. Process Correlation Improved, but Peak Bias Persists

Based on the simulations of four flood events, we systematically evaluated model performance under different precipitation conditions. Under observed-precipitation forcing, the model generally reproduces the overall hydrograph pattern and peak timing, yet it still underestimates peak magnitude. This underestimation is further amplified when ERA5 and FNL are used, indicating the limited skill of these datasets in real-time flood simulation.

However, in contrast to the significant peak error, numerical precipitation shows potential value in reconstructing flood forms. After incorporating the underlying surface, flood simulations using ERA5 and FNL data improved in both peak timing error and process correlation. This indicates that incorporating land surface information helps to optimize the model’s response timing to precipitation input. However, underestimation of peak discharge was not corrected, confirming that the flood peak simulation errors cannot be corrected by the hydrological model itself and need better precipitation conditions.

Overall, simulations driven by observed precipitation remain closest to reality, and numerical precipitation cannot yet replace gauge observations in flood modeling. Nonetheless, both ERA5 and FNL provide a useful correlation for capturing the evolution of the flood process. At present, numerical precipitation cannot provide accurate peak-time forecasts, but it offers practical skill for characterizing overall flood development and, to some extent, peak magnitude.

4.4. Limitations and Outlook

In this study, although the prediction capability of the model was improved by selecting the appropriate initial conditions for WRF and integrating rainfall information, some limitations are of concern. There are wide ranging results for the weather field, but the data of the observation field basin is limited, which does not match the results of the weather field simulation. The comprehensiveness and accuracy of the results can be improved if the distribution of the rainstorm center and rainfall outside the basin is integrated in the comparative analysis of the results. In view of this, it is necessary to increase the number of data sources, use radar data for correction, and combine the local precipitation characteristics to post-process the model results to improve the level of flood warning and the basin forecast.

5. Conclusions

Numerical simulation is an important method for flood forecasting. In this study, five rainfall events in the upper Minjiang River from 2018 to 2022 were simulated by the WRF model, and the hydro-hydraulic model was used to display hydrographs.

The findings demonstrate that the numerical model could simulate spatial distribution and peak rainfall patterns within the study area. However, significant uncertainty persists in the magnitude and timing of peak rainfall, and the model systematically underestimates cumulative and areal rainfall. Inputting more accurate initial field data into the WRF model effectively improves the simulations of rainfall magnitude and spatial distribution, bringing the rainfall results more in line with reality. This performance is particularly pronounced when using data with a spatial resolution of 0.25° and a 3 h time interval. Notably, this improvement has a positive impact on flood simulation, with simulated flood hydrographs showing moderate-to-strong correlations with the overall shape of measured discharges.

Further analysis shows that the length of the forecast period significantly affects the WRF simulation results. Appropriately extending the forecast period can improve WRF results, with simulations for 10–14 h forecast periods showing relatively accurate results. Furthermore, accounting for changes in elevation and land use conditions can improve the simulation of accumulated rainfall.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z. and Y.Z.; methodology, Y.G.; software, T.S.; validation, W.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z.; resources, Q.Z.; data curation, Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.G.; visualization, T.S.; supervision, Q.Z.; project administration, X.W.; funding acquisition, W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 52579026), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (232300421208, 242300421038), the Key Research Project Program of Higher Education Institutions in Henan Province (23A170003), the Open Research Fund Program of Key Laboratory of Urban Stormwater System and Water Environment (Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture), Ministry of Education (USSWE2023KF01).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zhao Wenjie, Zhao Yang, and Wang Xingping are employed by Sichuan Zipingpu Development Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WRF | Weather Research and Forecasting Model |

| IDW | Inverse Distance Weighting |

| NCEP | National Center for Weather and Environmental Prediction |

| ECMWF | ERA5 of the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts |

| NCAR | National Center for Atmospheric Research |

References

- Hallegatte, S.; Green, C.; Nicholls, R.J.; Corfee-Morlot, J. Future flood losses in major coastal cities. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gorman, P.A. Precipitation extremes under climate change. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2015, 1, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Li, X. Changes of abnormal precipitation with warming in the Minjiang River Basin in the past 40 years. J. Nat. Hazards 2022, 4, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, H.; Wang, L.; Shen, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, X. A Review: Advances of Flood Forecasting of Hydro-meteorological Forecast Technology. Meteorol. Mon. 2016, 42, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Chen, G.; Chen, F. Review on Coupling Atmospheric and Hydrological Model and lts Application in Flood Forecasting. Water Resour. Power 2010, 28, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pennelly, C.; Reuter, G.; Flesch, T. Verification of the WRF model for simulating heavy precipitation in Alberta. Atmos. Res. 2014, 135–136, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, A.; García-Ortega, E.; Navarro, A.; Sánchez, J.L.; Tapiador, F.J. WRF hourly evaluation for extreme precipitation events. Atmos. Res. 2022, 274, 106215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuge, F.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, R.; Xu, J. Simulation study of a heavy rainfall process in Lixiahe area of Jiangsu Province. J. Nat. Hazards 2014, 5, 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, E.; Song, L.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, D.; Su, X. Investigation on the 2018 prolonged freezing event in South China using the WRF model at convection-permitting resolution: Model performance and sensitivity analysis of physical parameterizations. Atmos. Res. 2024, 310, 107645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Karmakar, S.; Ghosh, S.; Niyogi, D. Improved simulation of very heavy rainfall events by incorporating WUDAPT urban land use/land cover in WRF. Urban Clim. 2020, 32, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsita, P.; Rakesh, V.; Singh, R.; Mohapatra, G.N. Impact of different land use data on WRF model short range forecasts during pre-monsoon and monsoon seasons in India. Urban Clim. 2023, 49, 101558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Mei, C.; Dong, L.; Wang, H. Effects of urbanization on extreme precipitation based on Weather Research and Forecasting model: A case study of heavy rainfall in Beijing. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 56, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvetti, L.; Pereira Filho, A.J. Ensemble hydrometeorological forecasts using WRF hourly QPF and topmodel for a middle watershed. Adv. Meteorol. 2014, 2014, 484120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Ye, J.; He, Z.; Bastola, S.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z. Evaluation of flood prediction capability of the distributed Grid-Xinanjiang model driven by weather research and forecasting precipitation. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2019, 12, e12544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, G. Research and Application of Joint Flood Control Dispatch for Large-Scale Reservoir Clusters in the Upper Yangtze River Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Peng, Y.; Yao, L.; Zhang, X. Impact of Different WRF Model Parameterisation Schemes on Rainfall Simulation in the Upper Yangtze River Basin. China Rural. Water Hydropower 2023, 5, 98–105. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Danielson, J.J.; Gesch, D.B. Global Multi-Resolution Terrain Elevation Data 2010 (GMTED2010) (No. 2011-1073); US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Siewert, J.; Kroszczynski, K. Evaluation of high-resolution land cover geographical data for the WRF model simulations. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collischonn, B.; Collischonn, W.; Tucci, C.E.M. Daily hydrological modeling in the Amazon basin using TRMM rainfall estimates. J. Hydrol. 2008, 360, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langella, G.; Basile, A.; Bonfante, A.; Terribile, F. High-resolution space–time rainfall analysis using integrated ANN inference systems. J. Hydrol. 2010, 387, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Z.-L.; Wang, J.; Lin, P.; Liang, J.; Li, Z.; Gu, Z. Improving flood simulation capability of the WRF-Hydro-RAPID model using a multi-source precipitation merging method. J. Hydrol. 2021, 592, 125814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Gao, S. Impact of different reanalysis data on WRF dynamical downscaling over China. Atmos. Res. 2018, 200, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankov, I.; Gallus, W.A., Jr.; Segal, M.; Koch, S.E. Influence of initial conditions on the WRF–ARW model QPF response to physical parameterization changes. Weather Forecast. 2007, 22, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhuo, L.; Han, D. Developing spin-up time framework for WRF extreme precipitation simulations. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, A.; Qiu, C.; Niu, G.Y. A piecewise modeling approach for climate sensitivity studies: Tests with a shallow-water model. J. Meteorol. Res. 2015, 29, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.