Application of a Parsimonious Phosphorus Model (SimplyP) to Two Hydrologically Contrasting Agricultural Catchments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

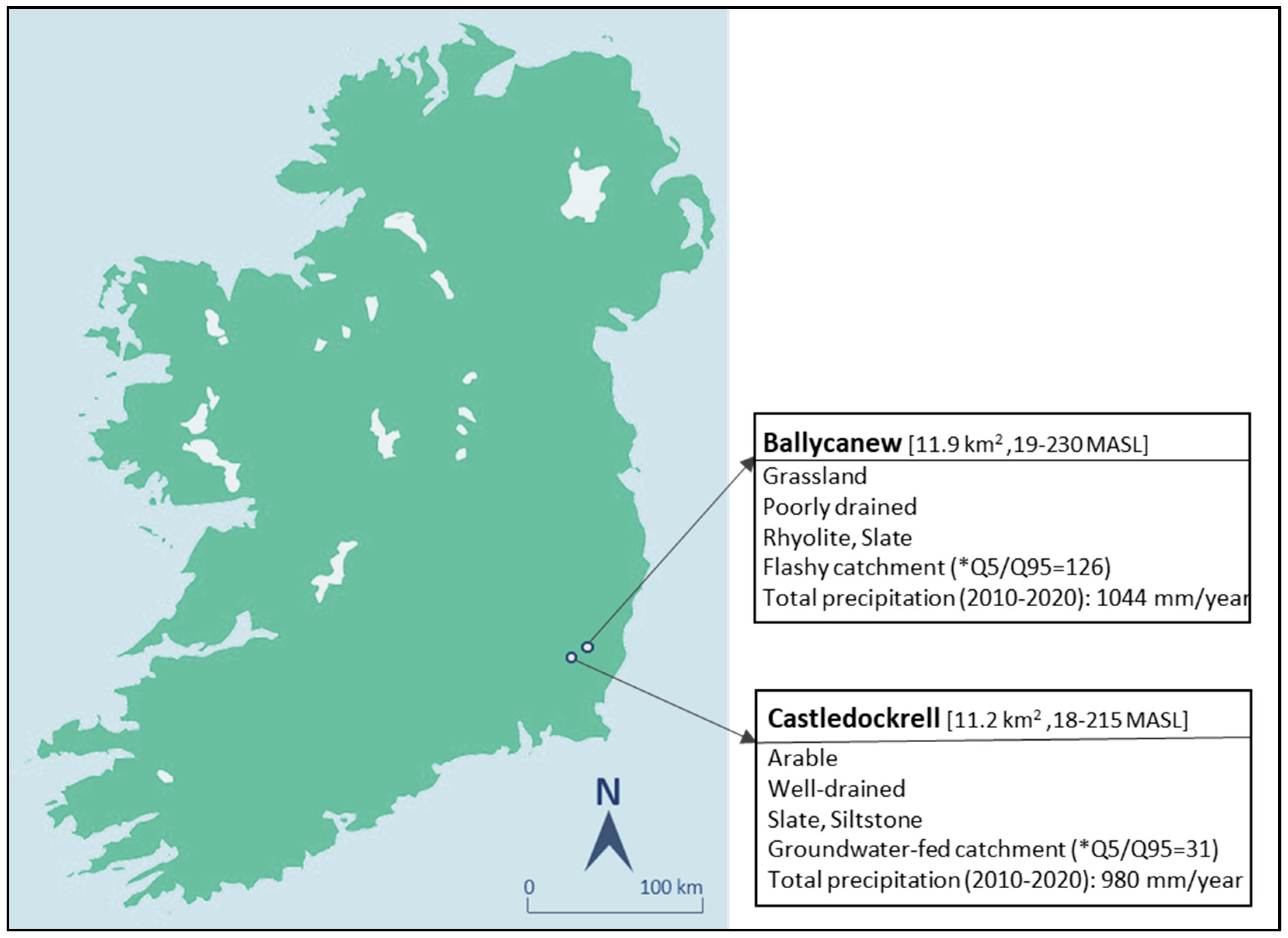

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Data

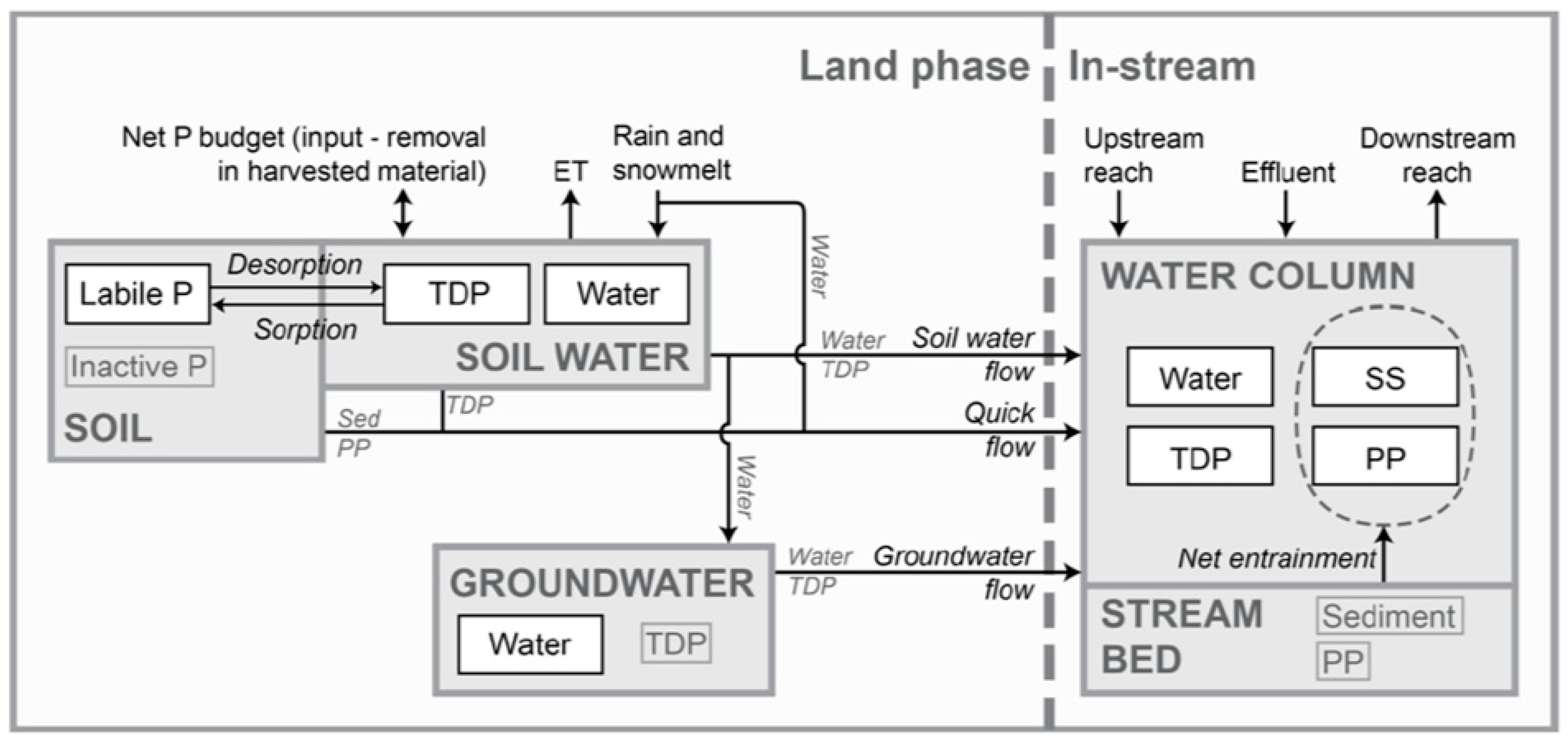

2.3. SimplyP Model

2.4. Parameters

2.5. Model Calibration

3. Results

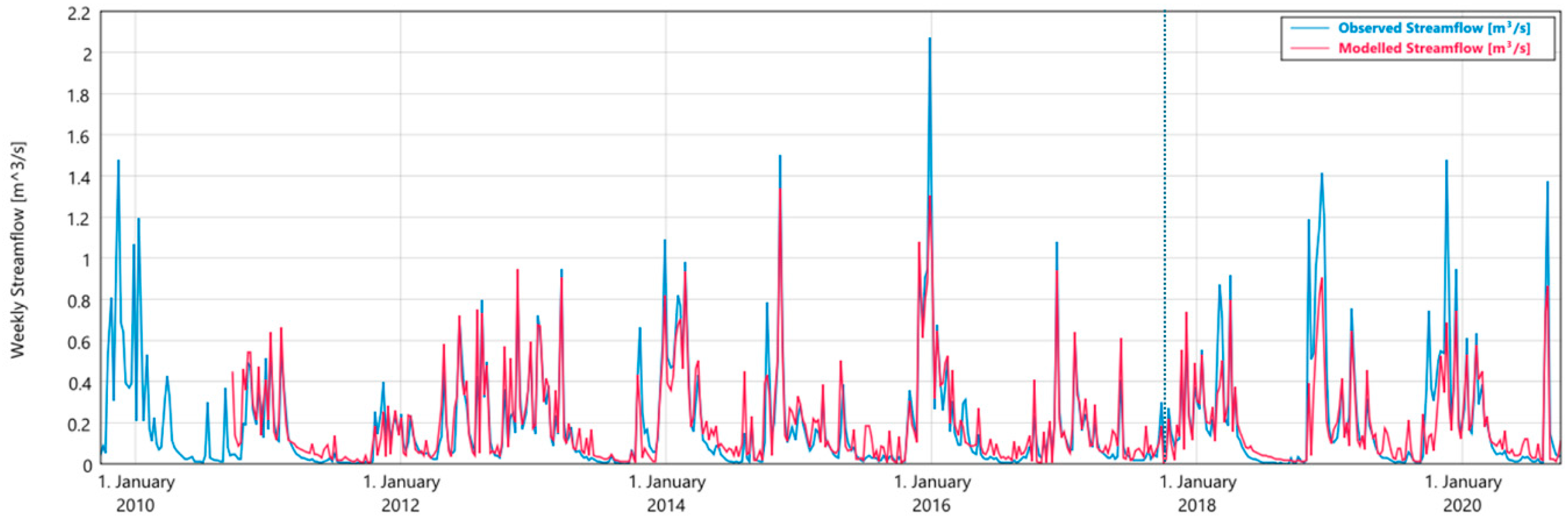

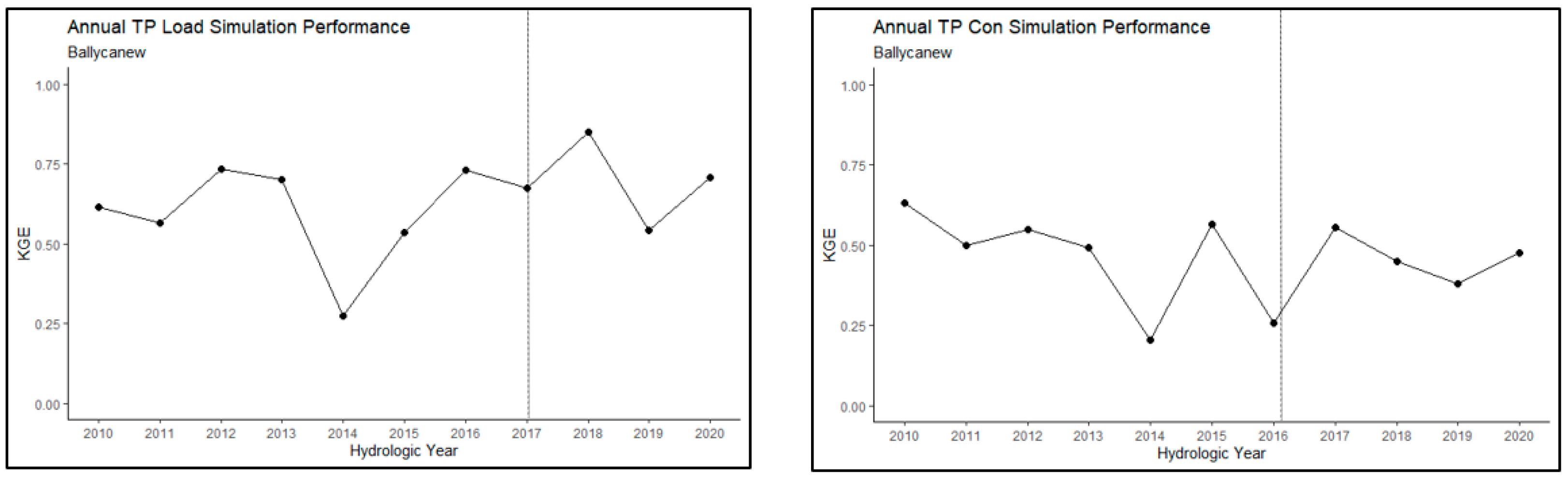

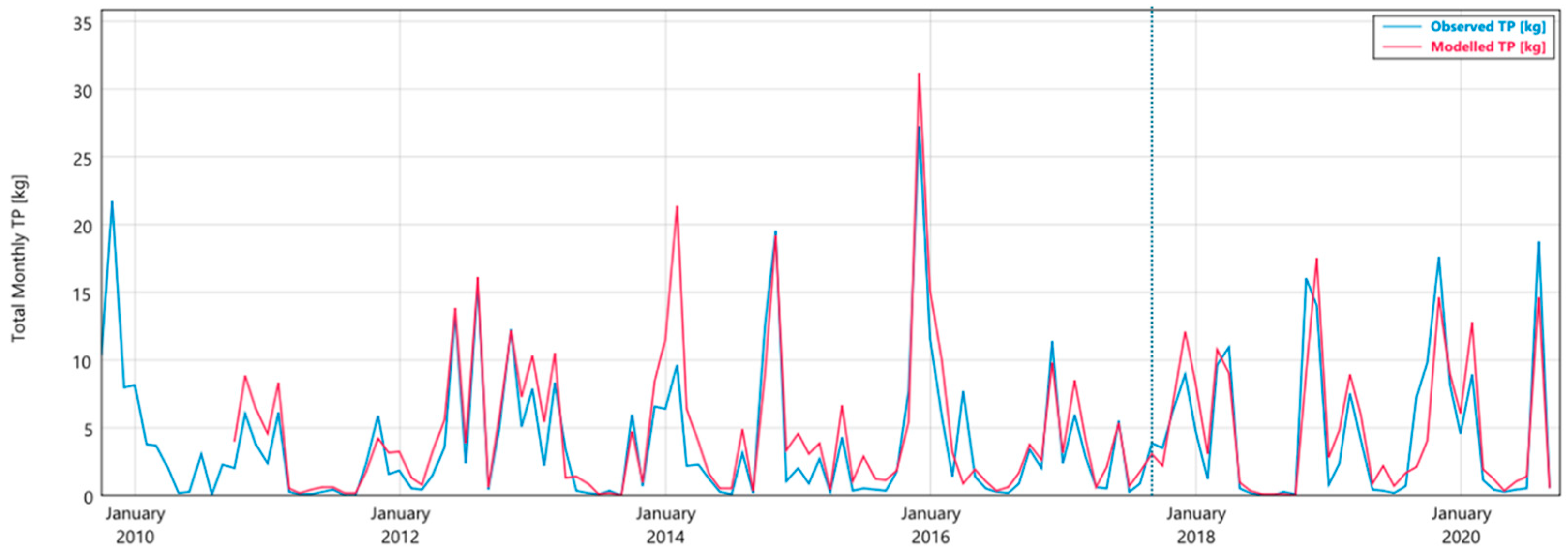

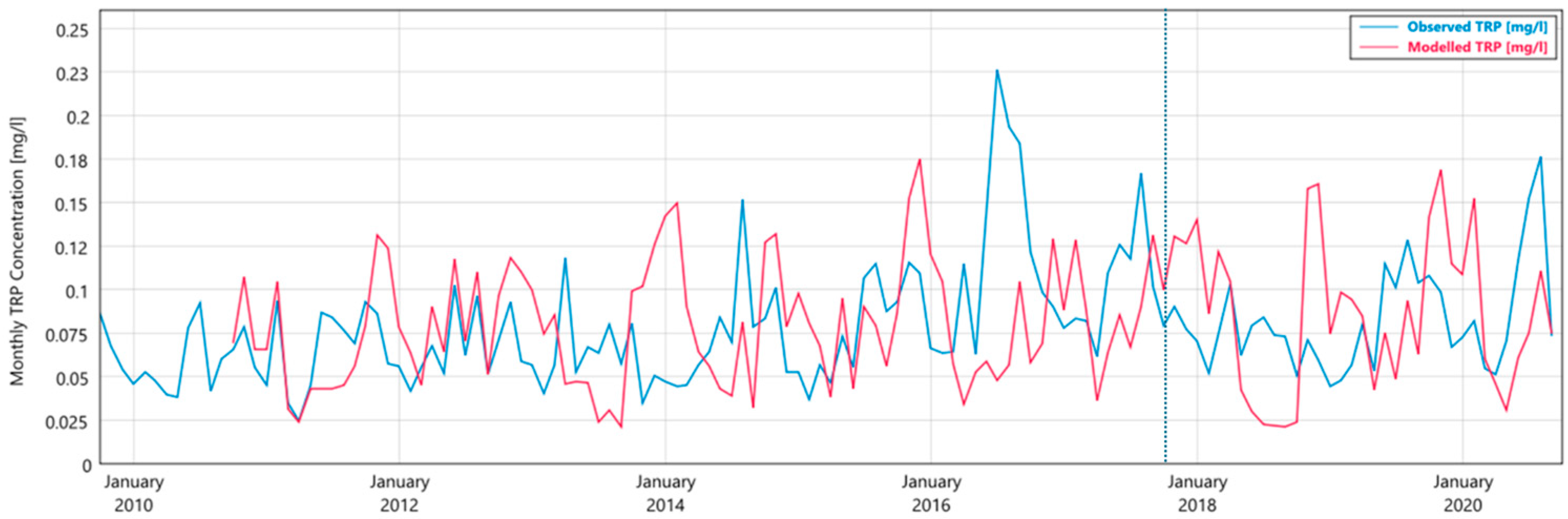

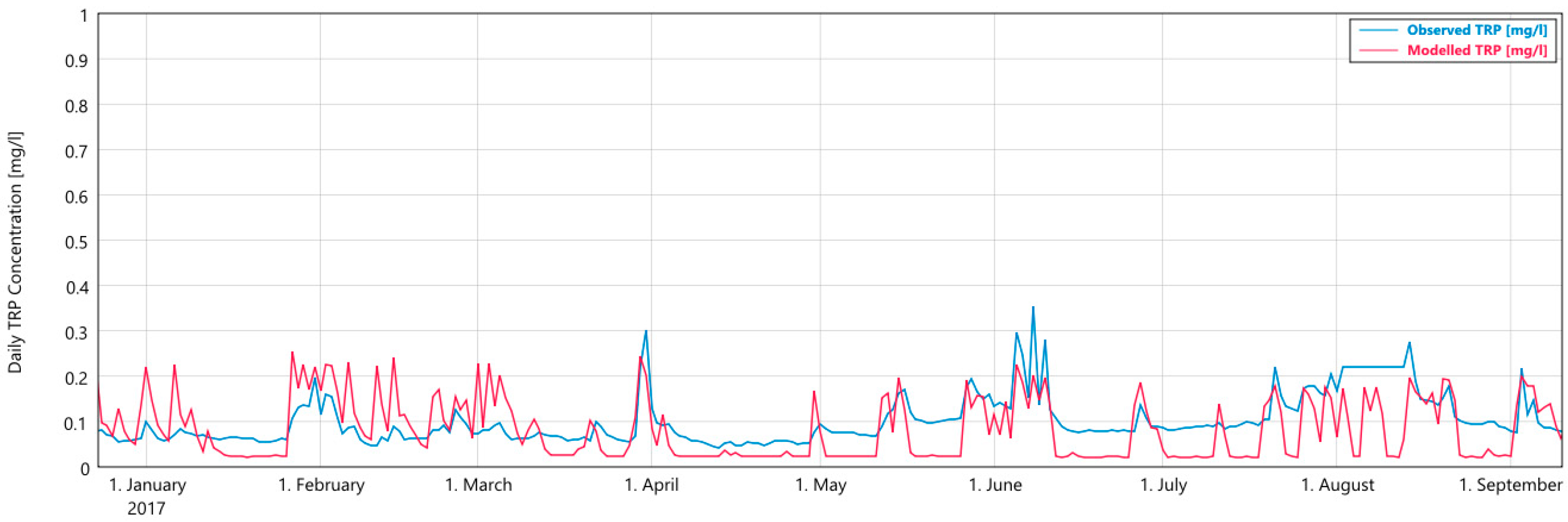

3.1. Ballycanew

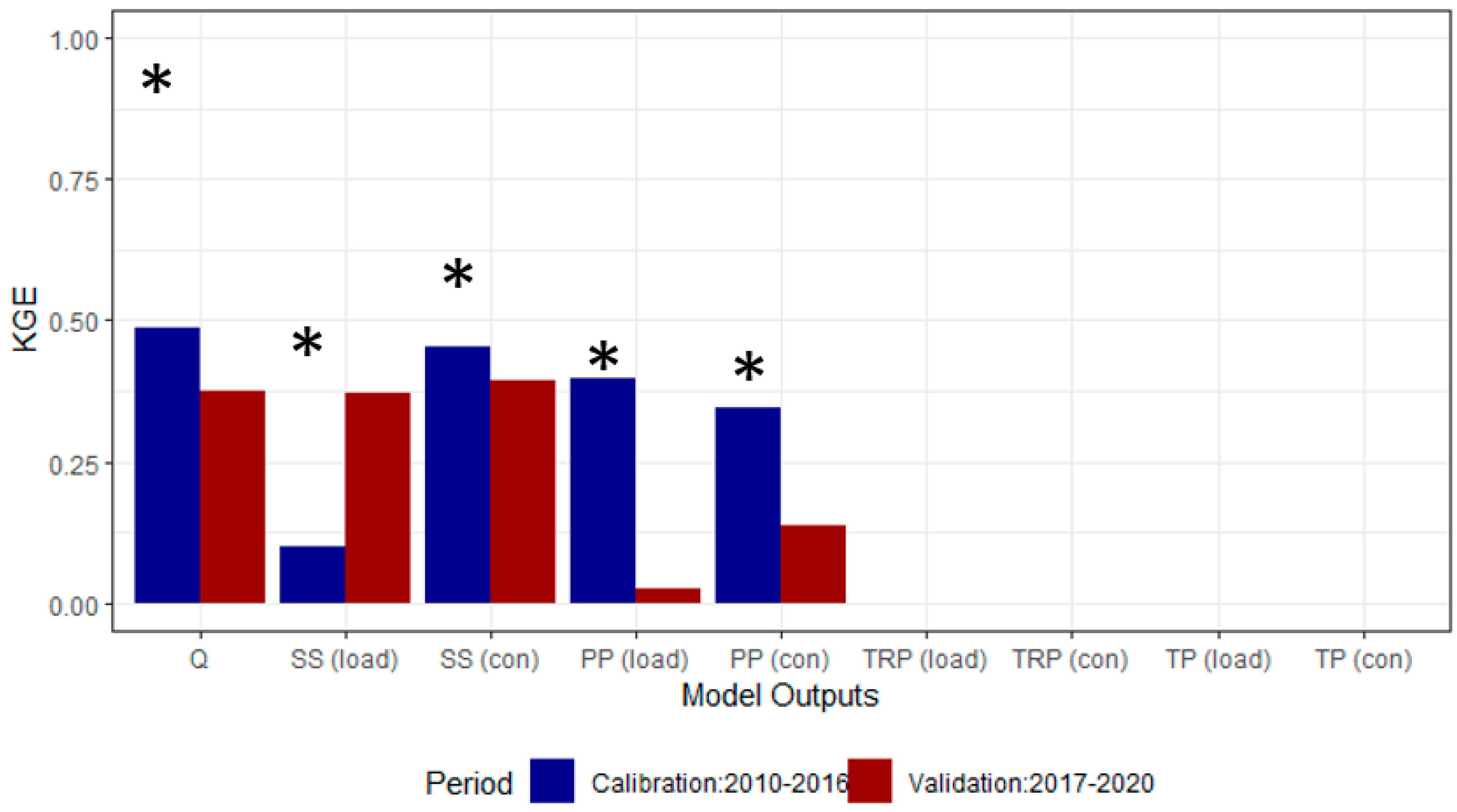

3.2. Castledockrell

4. Discussion

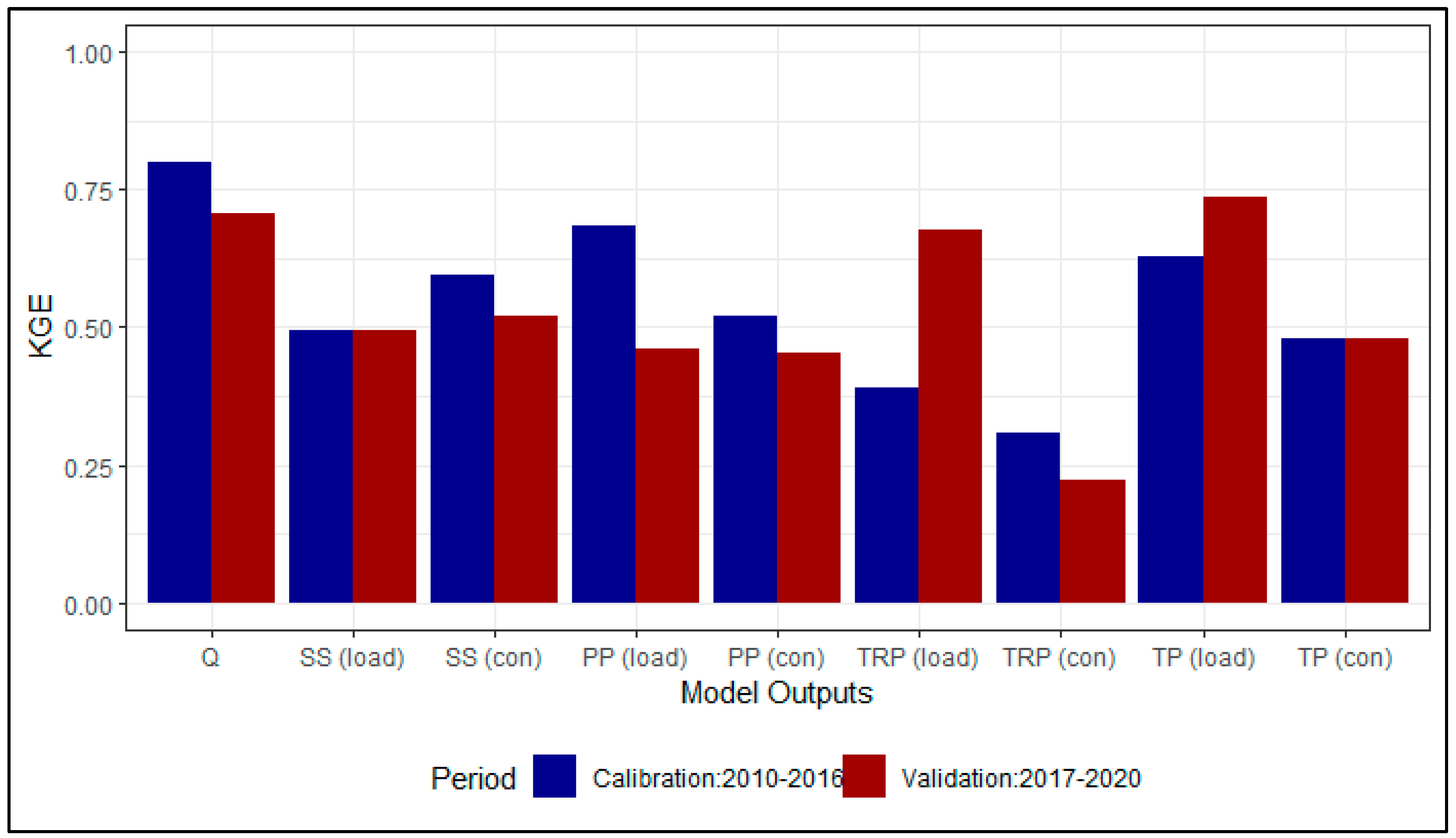

4.1. Overall Model Assessment

4.2. Strengths of SimplyP

4.3. Limitations in TRP Modelling

4.4. Model Complexity and Data Availability

4.5. Implications for Applications and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACP | Agricultural Catchments Programme |

| HY | hydrologic year |

| KGE | Kling–Gupta efficiency |

| NO3 | nitrate |

| NSE | Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency |

| P | phosphorus |

| PET | potential evapotranspiration |

| PP | particulate phosphorus |

| PRP | particulate reactive phosphorus |

| Q | streamflow |

| SRP | soluble reactive phosphorus |

| SS | suspended sediment |

| TDP | total dissolved phosphorus |

| TP | total phosphorus |

| TRP | total molybdate-reactive phosphorus |

Appendix A

| Obj. Function | Q (m3/s) | SS Load (kg/d) | SS Con (mg/L) | PP Load (kg/d) | PP Con (mg/L) | TRP Load (kg/d) | TRP Con (mg/L) | TP Load (kg/d) | TP Con (mg/L) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | |

| KGE | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| NSE | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.41 | −0.52 | −0.65 | 0.52 | 0.52 | −0.25 | −0.15 |

| Log NSE | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.61 | nan | 0.28 | 0.38 | nan | nan | nan | −1.83 | nan | nan | −1.15 | −2.65 | nan | nan | −0.60 | −1.26 |

| Mean Error (bias) | −0.01 | 0.02 | 385.16 | 347.64 | −0.15 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.97 | −0.14 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −1.16 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.00 |

| MAE | 0.10 | 0.11 | 666.39 | 633.73 | 6.17 | 6.08 | 1.24 | 1.52 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.77 | 1.70 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 2.92 | 3.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| RMSE | 0.23 | 0.28 | 3275.70 | 2651.20 | 12.52 | 14.86 | 4.55 | 5.52 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 5.18 | 5.16 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 8.76 | 9.80 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| r2 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| Idx. of agr. | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.73 |

| Spearman’s RCC | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.39 | 0.38 |

| Data Points | 2557 | 1461 | 2478 | 1451 | 2522 | 1461 | 2544 | 1393 | 2557 | 1461 | 2544 | 1424 | 2548 | 1461 | 2544 | 1396 | 2557 | 1461 |

| Obj. Function | Q (m3/s) | SS Load (kg/d) | SS Con (mg/L) | PP Load (kg/d) | PP Con (mg/L) | TRP Load (kg/d) | TRP Con (mg/L) | TP Load (kg/d) | TP Con (mg/L) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | Cal | Val | |

| KGE | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.10 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.14 | −1.65 | −2.03 | −0.56 | −0.65 | −0.18 | −0.44 | −0.38 | −0.29 |

| NSE | 0.19 | −0.07 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.29 | −0.93 | 0.23 | −0.10 | −10.06 | −31.66 | −5.91 | −1.42 | 0.28 | −2.83 | −3.64 | −1.04 |

| Log NSE | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.42 | nan | 0.31 | 0.44 | nan | nan | nan | nan | −0.84 | nan | −2.96 | nan | −0.25 | nan | −2.35 | −1.79 |

| Mean Error (bias) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 355.40 | 62.28 | 0.96 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −1.08 | −0.94 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −1.32 | −1.34 | −0.06 | −0.05 |

| MAE | 0.14 | 0.13 | 471.53 | 228.52 | 3.55 | 3.67 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.13 | 0.98 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.81 | 1.54 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| RMSE | 0.23 | 0.21 | 5520.30 | 1518.50 | 12.05 | 15.12 | 6.41 | 3.63 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 3.28 | 2.82 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 6.83 | 5.83 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| r2 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.15 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.24 | 0.17 |

| Idx. of agr. | 0.69 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.55 |

| Spearman’s RCC | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.70 | 0.59 | 0.65 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.75 | 0.74 | −0.18 | −0.20 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Data Points | 2557 | 1436 | 2552 | 1438 | 2552 | 1461 | 2543 | 1372 | 2543 | 1395 | 2543 | 1385 | 2543 | 1408 | 2548 | 1374 | 2543 | 1397 |

References

- Carpenter, S.R. Eutrophication of Aquatic Ecosystems: Bistability and Soil Phosphorus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 10002–10005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vero, S.E.; Fenton, O. Agricultural Pressures on Inland Waters. In Encyclopedia of Inland Waters, 2nd ed.; Mehner, T., Tockner, K., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 47–57. ISBN 978-0-12-822041-2. [Google Scholar]

- Leinweber, P.; Bathmann, U.; Buczko, U.; Douhaire, C.; Eichler-Löbermann, B.; Frossard, E.; Ekardt, F.; Jarvie, H.; Krämer, I.; Kabbe, C.; et al. Handling the Phosphorus Paradox in Agriculture and Natural Ecosystems: Scarcity, Necessity, and Burden of P. Ambio 2018, 47, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellander, P.-E.; Lynch, M.B.; Galloway, J.; Žurovec, O.; McCormack, M.; O’Neill, M.; Hawtree, D.; Burgess, E. Benchmarking a Decade of Holistic Agro-Environmental Studies within the Agricultural Catchments Programme. Ir. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 61, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haygarth, P.M.; Condron, L.M.; Heathwaite, A.L.; Turner, B.L.; Harris, G.P. The Phosphorus Transfer Continuum: Linking Source to Impact with an Interdisciplinary and Multi-Scaled Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2005, 344, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vero, S.E.; Doody, D. Applying the Nutrient Transfer Continuum Framework to Phosphorus and Nitrogen Losses from Livestock Farmyards to Watercourses. J. Environ. Qual. 2021, 50, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascuel-Odoux, C.; Fovet, O.; Faucheux, M.; Salmon-Monviola, J.; Strohmenger, L. How to Assess Water Quality Change in Temperate Headwater Catchments of Western Europe under Climate Change: Examples and Perspectives. Comptes Rendus. Geosci. 2023, 355, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Sinshaw, T.; Forshay, K.J. Review of Watershed-Scale Water Quality and Nonpoint Source Pollution Models. Geosciences 2020, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockenden, M.C.; Hollaway, M.J.; Beven, K.J.; Collins, A.L.; Evans, R.; Falloon, P.D.; Forber, K.J.; Hiscock, K.M.; Kahana, R.; Macleod, C.J.A.; et al. Major Agricultural Changes Required to Mitigate Phosphorus Losses under Climate Change. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Merritt, W.S.; Croke, B.F.W.; Weber, T.R.; Jakeman, A.J. A Review of Catchment-Scale Water Quality and Erosion Models and a Synthesis of Future Prospects. Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 114, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.G.; Srinivasan, R.; Muttiah, R.S.; Williams, J.R. Large Area Modeling and Assessment Part I: Model Development. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1998, 34, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Blake, L.A.; Wade, A.J.; Futter, M.N.; Butterfield, D.; Couture, R.-M.; Cox, B.A.; Crossman, J.; Ekholm, P.; Halliday, S.J.; Jin, L.; et al. The INtegrated CAtchment Model of Phosphorus Dynamics (INCA-P): Description and Demonstration of New Model Structure and Equations. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 83, 356–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, A.J.; Whitehead, P.G.; Butterfield, D. The Integrated Catchments Model of Phosphorus Dynamics (INCA-P), a New Approach for Multiple Source Assessment in Heterogeneous River Systems: Model Structure and Equations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2002, 6, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellen, C.; Kamran-Disfani, A.-R.; Arhonditsis, G.B. Evaluation of the Current State of Distributed Watershed Nutrient Water Quality Modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 3278–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson-Blake, L.A.; Dunn, S.M.; Helliwell, R.C.; Skeffington, R.A.; Stutter, M.I.; Wade, A.J. How Well Can We Model Stream Phosphorus Concentrations in Agricultural Catchments? Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 64, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Blake, L.A.; Sample, J.E.; Wade, A.J.; Helliwell, R.C.; Skeffington, R.A. Are Our Dynamic Water Quality Models Too Complex? A Comparison of a New Parsimonious Phosphorus Model, SimplyP, and INCA-P. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 5382–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norling, M.D.; Jackson-Blake, L.A.; Calidonio, J.-L.G.; Sample, J.E. Rapid Development of Fast and Flexible Environmental Models: The Mobius Framework v1.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14, 1885–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, P.F.; Hewett, C.J.M.; Dayawansa, N.D.K. TOPCAT-NP: A Minimum Information Requirement Model for Simulation of Flow and Nutrient Transport from Agricultural Systems. Hydrol. Process. 2008, 22, 2565–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Quinn, P.F.; Perks, M.; Barber, N.J.; Jonczyk, J.; Owen, G.J. Simulating High Frequency Water Quality Monitoring Data Using a Catchment Runoff Attenuation Flux Tool (CRAFT). Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 572, 1622–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellander, P.-E.; Jordan, P. Charting a Perfect Storm of Water Quality Pressures. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellander, P.-E.; Jordan, P.; Shore, M.; Melland, A.R.; Shortle, G. Flow Paths and Phosphorus Transfer Pathways in Two Agricultural Streams with Contrasting Flow Controls. Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 3504–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellander, P.-E.; Jordan, P.; Shore, M.; McDonald, N.T.; Wall, D.P.; Shortle, G.; Daly, K. Identifying Contrasting Influences and Surface Water Signals for Specific Groundwater Phosphorus Vulnerability. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.; Cassidy, R.; Macintosh, K.A.; Arnscheidt, J. Field and Laboratory Tests of Flow-Proportional Passive Samplers for Determining Average Phosphorus and Nitrogen Concentration in Rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 2331–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D.E. Dlib-Ml: A Machine Learning Toolkit. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2009, 10, 1755–1758. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, H.V.; Kling, H.; Yilmaz, K.K.; Martinez, G.F. Decomposition of the Mean Squared Error and NSE Performance Criteria: Implications for Improving Hydrological Modelling. J. Hydrol. 2009, 377, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hawtree, D.; Mellander, P.-E.; Adams, R.; Ezzati, G.; Jackson-Blake, L.; Zurovec, O.; Norling, M.; Galloway, J. Application of a Parsimonious Phosphorus Model (SimplyP) to Two Hydrologically Contrasting Agricultural Catchments. Water 2026, 18, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010006

Hawtree D, Mellander P-E, Adams R, Ezzati G, Jackson-Blake L, Zurovec O, Norling M, Galloway J. Application of a Parsimonious Phosphorus Model (SimplyP) to Two Hydrologically Contrasting Agricultural Catchments. Water. 2026; 18(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleHawtree, Daniel, Per-Erik Mellander, Russell Adams, Golnaz Ezzati, Leah Jackson-Blake, Ognjen Zurovec, Magnus Norling, and Jason Galloway. 2026. "Application of a Parsimonious Phosphorus Model (SimplyP) to Two Hydrologically Contrasting Agricultural Catchments" Water 18, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010006

APA StyleHawtree, D., Mellander, P.-E., Adams, R., Ezzati, G., Jackson-Blake, L., Zurovec, O., Norling, M., & Galloway, J. (2026). Application of a Parsimonious Phosphorus Model (SimplyP) to Two Hydrologically Contrasting Agricultural Catchments. Water, 18(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010006