A Hybrid PCA-TOPSIS and Machine Learning Approach to Basin Prioritization for Sustainable Land and Water Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

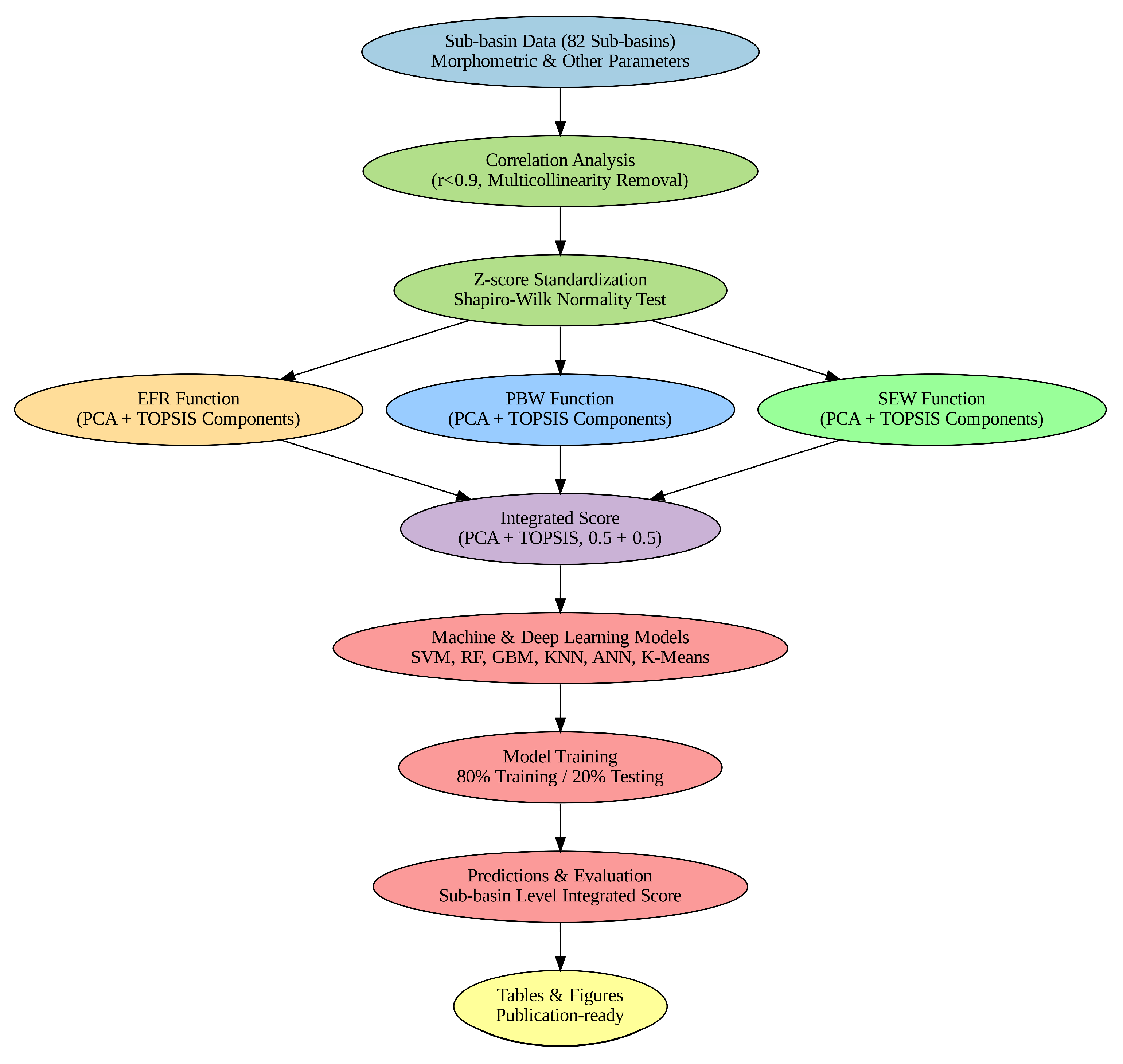

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Data Sets

2.3. Computational Environment and Tools

2.4. Data Preprocessing

2.4.1. Weighting

2.4.2. Calculation of the Prioritization Index

2.4.3. Ranking the Sub-Basins

2.5. Method

Machine and Deep Learning Methods for Sub-Basin Prioritization Analysis

- Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- 2.

- Random Forest (RF)

- 3.

- Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM)

- 4.

- K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)

- 5.

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

- 6.

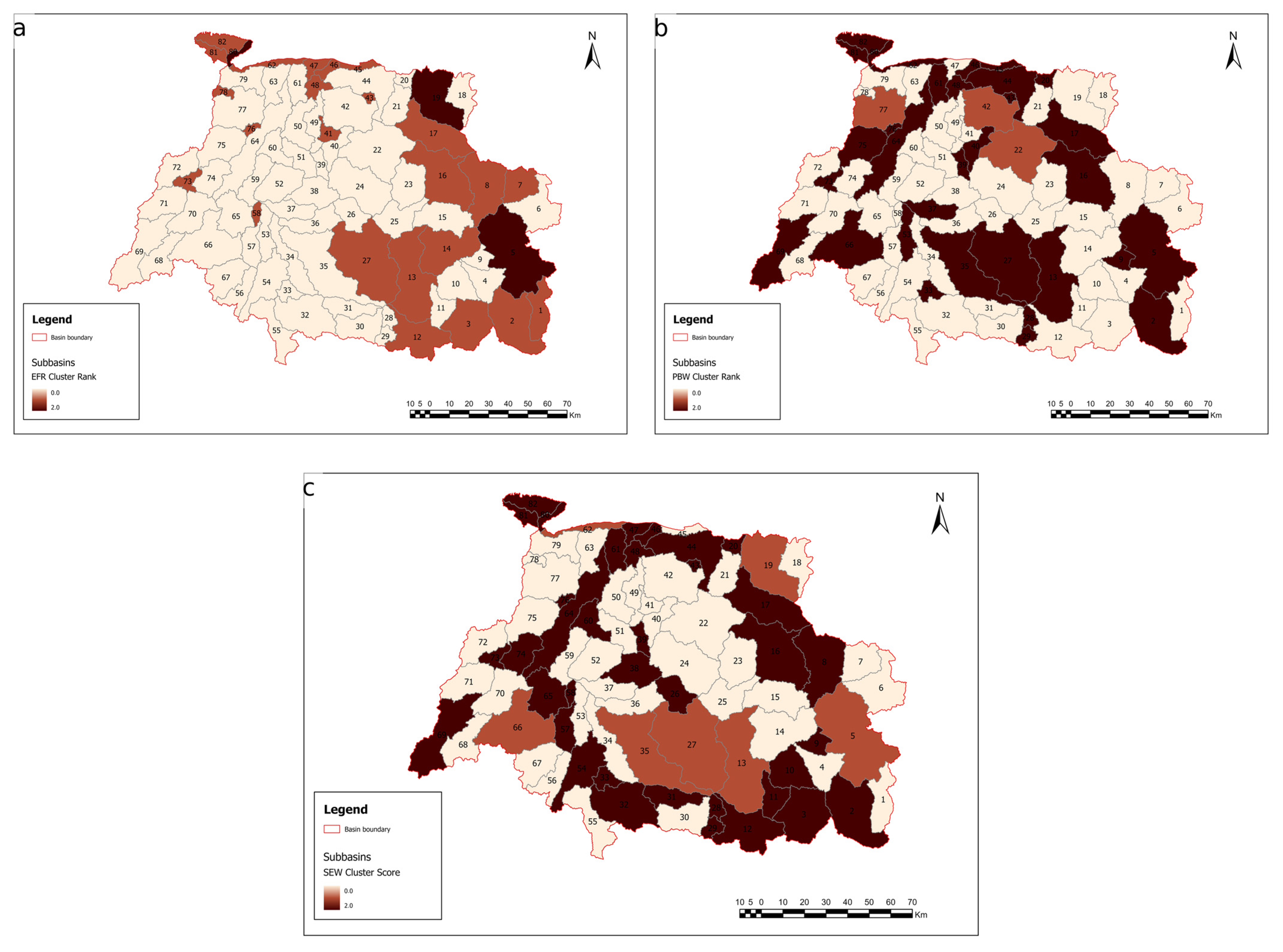

- K-Means Clustering

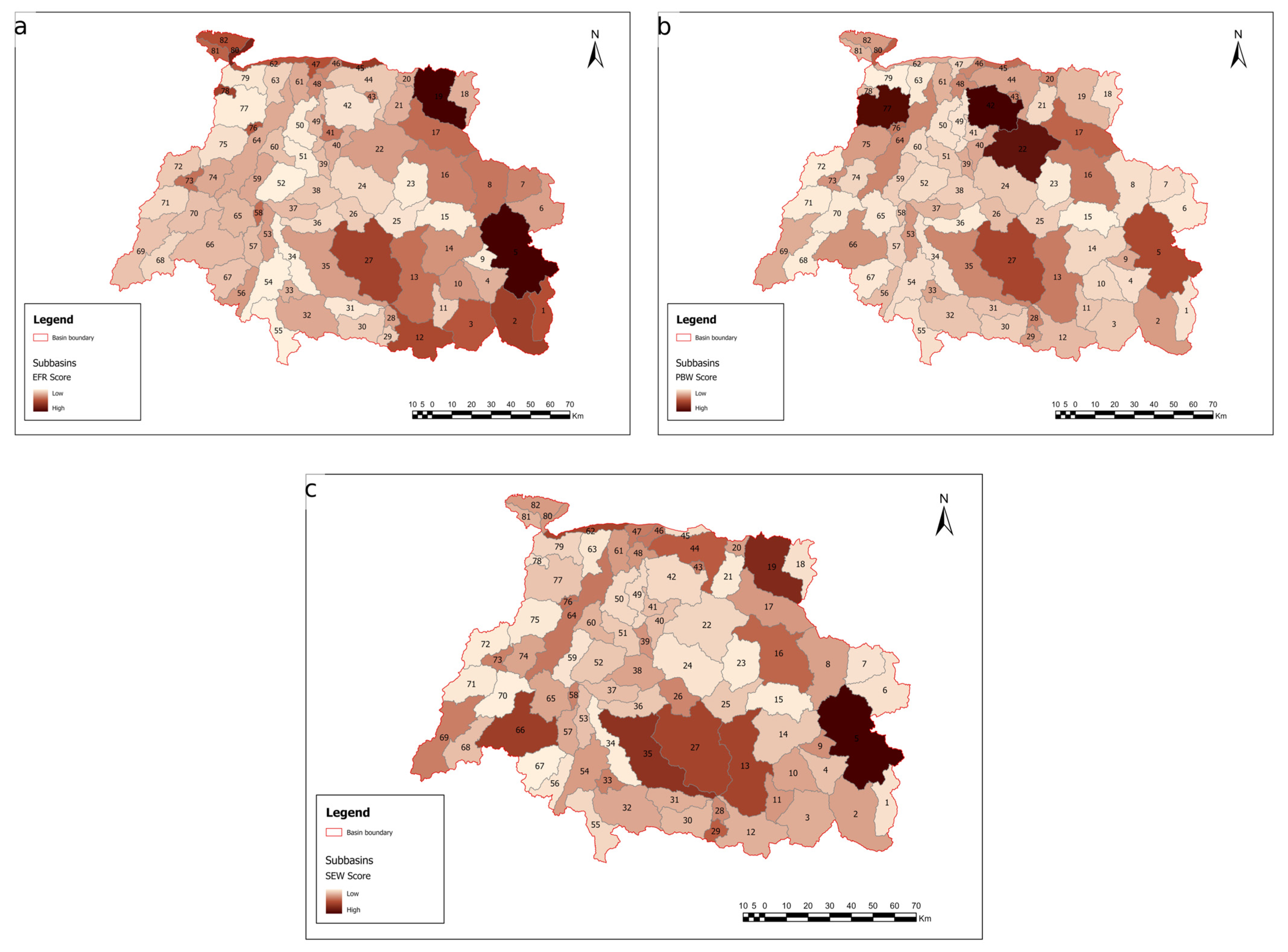

3. Results

3.1. PCA Results

Machine and Deep Learning Methods for Sub-Basin Prioritization Analysis Results

- 1.

- Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- 2.

- Random Forest (RF)

- 3.

- Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM)

- 4.

- K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)

- 5.

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

- 6.

- Evaluation of Model Results

- 7.

- Evaluation of K-Means Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Subbasin | EFR TOPSIS + PCA Integrated Score | EFR Ranking | PBW TOPSIS + PCA Integrated Score | PBW Ranking | SEW TOPSIS + PCA Integrated Score | SEW Ranking | EFR Cluster | EFR Score | PBW Cluster | PBW Score | SEW Cluster | SEW Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB1 | 0.502 | 10 | 0.043 | 69 | 0.047 | 68 | 0.262 | 1 | 0.388 | 0 | 0.561 | 0 |

| SB2 | 0.594 | 5 | 0.259 | 24 | 0.243 | 33 | 0.27 | 1 | 0.473 | 2 | 0.323 | 2 |

| SB3 | 0.48 | 12 | 0.118 | 47 | 0.209 | 40 | 0.477 | 1 | 0.879 | 0 | 0.48 | 2 |

| SB4 | 0.195 | 44 | 0.056 | 62 | 0.146 | 51 | 0.312 | 0 | 0.314 | 0 | 1.621 | 0 |

| SB5 | 1 | 1 | 0.537 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.362 | 2 | 0.309 | 2 | 0.225 | 1 |

| SB6 | 0.252 | 32 | 0.025 | 72 | 0.047 | 67 | 0.468 | 0 | 0.681 | 0 | 0.498 | 0 |

| SB7 | 0.339 | 23 | 0.054 | 64 | 0.044 | 69 | 0.417 | 1 | 0.512 | 0 | 0.546 | 0 |

| SB8 | 0.376 | 20 | 0.05 | 66 | 0.244 | 32 | 0.391 | 1 | 0.583 | 0 | 0.329 | 2 |

| SB9 | 0.015 | 74 | 0.219 | 29 | 0.297 | 22 | 0.434 | 0 | 0.677 | 2 | 0.65 | 2 |

| SB10 | 0.274 | 28 | 0.074 | 57 | 0.241 | 34 | 0.433 | 0 | 0.65 | 0 | 0.404 | 2 |

| SB11 | 0.106 | 61 | 0.134 | 42 | 0.273 | 26 | 0.418 | 0 | 0.684 | 0 | 0.726 | 2 |

| SB12 | 0.539 | 8 | 0.168 | 37 | 0.198 | 42 | 0.386 | 1 | 0.555 | 0 | 0.676 | 2 |

| SB13 | 0.398 | 18 | 0.355 | 11 | 0.563 | 6 | 0.444 | 1 | 0.439 | 2 | 0.344 | 1 |

| SB14 | 0.291 | 27 | 0.079 | 56 | 0.129 | 55 | 0.406 | 1 | 0.373 | 0 | 0.392 | 0 |

| SB15 | 0.009 | 77 | 0 | 82 | 0.011 | 78 | 0.409 | 0 | 0.444 | 0 | 0.662 | 0 |

| SB16 | 0.342 | 22 | 0.362 | 10 | 0.428 | 10 | 0.493 | 1 | 0.407 | 2 | 0.388 | 2 |

| SB17 | 0.413 | 16 | 0.432 | 7 | 0.271 | 27 | 0.235 | 1 | 0.257 | 2 | 0.278 | 2 |

| SB18 | 0.201 | 42 | 0.055 | 63 | 0.051 | 66 | 0.246 | 0 | 0.431 | 0 | 0.412 | 0 |

| SB19 | 1 | 2 | 0.172 | 36 | 0.728 | 2 | 0.248 | 2 | 0.488 | 0 | 0.163 | 1 |

| SB20 | 0.22 | 37 | 0.324 | 16 | 0.246 | 31 | 0.488 | 0 | 0.482 | 2 | 0.48 | 2 |

| SB21 | 0.199 | 43 | 0.071 | 58 | 0.021 | 74 | 0.36 | 0 | 0.566 | 0 | 0.297 | 0 |

| SB22 | 0.253 | 31 | 0.882 | 3 | 0.083 | 59 | 0.297 | 0 | 0.144 | 1 | 0.307 | 0 |

| SB23 | 0.014 | 76 | 0.02 | 75 | 0.014 | 77 | 0.539 | 0 | 0.43 | 0 | 0.318 | 0 |

| SB24 | 0.069 | 68 | 0.129 | 45 | 0.037 | 72 | 0.327 | 0 | 0.372 | 0 | 0.51 | 0 |

| SB25 | 0.038 | 71 | 0.105 | 50 | 0.129 | 56 | 0.818 | 0 | 0.804 | 0 | 0.453 | 0 |

| SB26 | 0.111 | 60 | 0.162 | 38 | 0.328 | 20 | 0.455 | 0 | 0.476 | 0 | 0.495 | 2 |

| SB27 | 0.57 | 7 | 0.556 | 4 | 0.566 | 5 | 0.256 | 1 | 0.242 | 2 | 0.321 | 1 |

| SB28 | 0.24 | 34 | 0.329 | 13 | 0.315 | 21 | 0.221 | 0 | 0.303 | 2 | 0.337 | 2 |

| SB29 | 0.105 | 62 | 0.26 | 22 | 0.456 | 9 | 0.362 | 0 | 0.521 | 2 | 0.707 | 2 |

| SB30 | 0.115 | 59 | 0.105 | 49 | 0.176 | 45 | 0.69 | 0 | 0.659 | 0 | 1.056 | 0 |

| SB31 | 0.024 | 73 | 0.14 | 41 | 0.204 | 41 | 0.586 | 0 | 1.002 | 0 | 0.793 | 2 |

| SB32 | 0.223 | 36 | 0.133 | 43 | 0.226 | 38 | 0.732 | 0 | 0.858 | 0 | 0.629 | 2 |

| SB33 | 0.189 | 45 | 0.235 | 27 | 0.346 | 17 | 0.439 | 0 | 0.616 | 2 | 0.785 | 2 |

| SB34 | 0.003 | 79 | 0.045 | 68 | 0.008 | 80 | 0.562 | 0 | 0.871 | 0 | 0.431 | 0 |

| SB35 | 0.256 | 30 | 0.327 | 14 | 0.669 | 3 | 0.41 | 0 | 0.438 | 2 | 0.324 | 1 |

| SB36 | 0.07 | 66 | 0.011 | 79 | 0.13 | 53 | 0.385 | 0 | 0.411 | 0 | 0.489 | 0 |

| SB37 | 0.165 | 47 | 0.19 | 34 | 0.155 | 48 | 0.804 | 0 | 1.08 | 2 | 0.572 | 0 |

| SB38 | 0.124 | 57 | 0.104 | 51 | 0.239 | 35 | 0.47 | 0 | 0.495 | 0 | 0.531 | 2 |

| SB39 | 0.156 | 50 | 0.216 | 30 | 0.286 | 23 | 0.334 | 0 | 0.463 | 2 | 0.738 | 2 |

| SB40 | 0.201 | 41 | 0.226 | 28 | 0.156 | 46 | 0.621 | 0 | 0.822 | 2 | 0.431 | 0 |

| SB41 | 0.375 | 21 | 0.09 | 52 | 0.155 | 47 | 0.354 | 1 | 0.317 | 0 | 0.412 | 0 |

| SB42 | 0.043 | 70 | 1 | 1 | 0.072 | 61 | 0.404 | 0 | 0.229 | 1 | 0.421 | 0 |

| SB43 | 0.33 | 24 | 0.349 | 12 | 0.356 | 15 | 0.299 | 1 | 0.341 | 2 | 0.22 | 2 |

| SB44 | 0.125 | 56 | 0.245 | 26 | 0.464 | 8 | 0.372 | 0 | 0.334 | 2 | 0.33 | 2 |

| SB45 | 0.631 | 4 | 0.399 | 8 | 0.067 | 64 | 0.284 | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.334 | 0 |

| SB46 | 0.32 | 25 | 0.324 | 17 | 0.378 | 12 | 0.359 | 1 | 0.385 | 2 | 0.305 | 2 |

| SB47 | 0.496 | 11 | 0.083 | 54 | 0.359 | 14 | 0.474 | 1 | 0.351 | 0 | 0.373 | 2 |

| SB48 | 0.306 | 26 | 0.312 | 18 | 0.281 | 24 | 0.387 | 1 | 0.459 | 2 | 0.352 | 2 |

| SB49 | 0.155 | 51 | 0.04 | 70 | 0.07 | 63 | 0.394 | 0 | 0.271 | 0 | 0.357 | 0 |

| SB50 | 0.014 | 75 | 0.049 | 67 | 0.071 | 62 | 0.384 | 0 | 0.381 | 0 | 0.351 | 0 |

| SB51 | 0.099 | 63 | 0.119 | 46 | 0.116 | 57 | 0.418 | 0 | 0.496 | 0 | 0.556 | 0 |

| SB52 | 0 | 81 | 0.068 | 60 | 0.129 | 54 | 0.547 | 0 | 0.815 | 0 | 0.326 | 0 |

| SB53 | 0.25 | 33 | 0.274 | 21 | 0.149 | 50 | 0.412 | 0 | 0.496 | 2 | 0.446 | 0 |

| SB54 | 0 | 80 | 0.057 | 61 | 0.257 | 30 | 0.576 | 0 | 0.703 | 0 | 0.456 | 2 |

| SB55 | 0 | 82 | 0.05 | 65 | 0.076 | 60 | 0.787 | 0 | 0.817 | 0 | 0.373 | 0 |

| SB56 | 0.262 | 29 | 0.159 | 39 | 0.037 | 71 | 0.691 | 0 | 0.749 | 0 | 0.518 | 0 |

| SB57 | 0.159 | 49 | 0.089 | 53 | 0.22 | 39 | 0.609 | 0 | 0.572 | 0 | 0.801 | 2 |

| SB58 | 0.404 | 17 | 0.132 | 44 | 0.338 | 19 | 0.345 | 1 | 0.338 | 0 | 0.29 | 2 |

| SB59 | 0.225 | 35 | 0.111 | 48 | 0.039 | 70 | 1.117 | 0 | 1.087 | 0 | 1.391 | 0 |

| SB60 | 0.144 | 53 | 0.07 | 59 | 0.194 | 43 | 0.516 | 0 | 0.466 | 0 | 0.377 | 2 |

| SB61 | 0.214 | 40 | 0.192 | 33 | 0.261 | 29 | 0.748 | 0 | 0.788 | 2 | 0.346 | 2 |

| SB62 | 0.48 | 13 | 0.2 | 32 | 0.559 | 7 | 0.154 | 1 | 0.152 | 2 | 0.159 | 1 |

| SB63 | 0.096 | 64 | 0.018 | 76 | 0.03 | 73 | 0.446 | 0 | 0.441 | 0 | 0.441 | 0 |

| SB64 | 0.216 | 39 | 0.325 | 15 | 0.372 | 13 | 0.38 | 0 | 0.27 | 2 | 0.22 | 2 |

| SB65 | 0.175 | 46 | 0.028 | 71 | 0.232 | 37 | 0.302 | 0 | 0.618 | 0 | 0.31 | 2 |

| SB66 | 0.164 | 48 | 0.283 | 20 | 0.605 | 4 | 0.442 | 0 | 0.251 | 2 | 0.255 | 1 |

| SB67 | 0.142 | 55 | 0.023 | 73 | 0 | 82 | 0.783 | 0 | 1.05 | 0 | 0.721 | 0 |

| SB68 | 0.079 | 65 | 0.012 | 78 | 0.152 | 49 | 0.776 | 0 | 0.793 | 0 | 0.72 | 0 |

| SB69 | 0.143 | 54 | 0.207 | 31 | 0.352 | 16 | 0.743 | 0 | 0.71 | 2 | 0.466 | 2 |

| SB70 | 0.149 | 52 | 0.02 | 74 | 0.005 | 81 | 0.566 | 0 | 0.68 | 0 | 0.666 | 0 |

| SB71 | 0.069 | 67 | 0.013 | 77 | 0.019 | 76 | 0.823 | 0 | 0.865 | 0 | 0.786 | 0 |

| SB72 | 0.121 | 58 | 0.008 | 80 | 0.01 | 79 | 0.747 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.669 | 0 |

| SB73 | 0.392 | 19 | 0.285 | 19 | 0.346 | 18 | 0.613 | 1 | 0.645 | 2 | 0.609 | 2 |

| SB74 | 0.22 | 38 | 0.082 | 55 | 0.235 | 36 | 0.766 | 0 | 1.063 | 0 | 0.691 | 2 |

| SB75 | 0.051 | 69 | 0.258 | 25 | 0.021 | 75 | 0.596 | 0 | 0.435 | 2 | 0.363 | 0 |

| SB76 | 0.471 | 14 | 0.365 | 9 | 0.388 | 11 | 0.352 | 1 | 0.373 | 2 | 0.466 | 2 |

| SB77 | 0.007 | 78 | 0.936 | 2 | 0.132 | 52 | 0.253 | 0 | 0.273 | 1 | 0.297 | 0 |

| SB78 | 0.576 | 6 | 0.155 | 40 | 0.051 | 65 | 0.237 | 1 | 0.257 | 0 | 0.356 | 0 |

| SB79 | 0.032 | 72 | 0.003 | 81 | 0.091 | 58 | 0.446 | 0 | 0.476 | 0 | 0.35 | 0 |

| SB80 | 0.77 | 3 | 0.446 | 6 | 0.277 | 25 | 0.226 | 2 | 0.216 | 2 | 0.271 | 2 |

| SB81 | 0.438 | 15 | 0.19 | 35 | 0.189 | 44 | 0.349 | 1 | 0.332 | 2 | 0.38 | 2 |

| SB82 | 0.506 | 9 | 0.26 | 23 | 0.262 | 28 | 0.376 | 1 | 0.362 | 2 | 0.453 | 2 |

| Parameters | EFR Function | PBW Function | SEW Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation (max, min, mean) | ✓ | ||

| Basin relief (R) | ✓ | ||

| Relief ratio (Rr) | ✓ | ||

| Ruggedness number (Rn) | ✓ | ||

| Molten Ruggedness number (Mrn) | ✓ | ||

| Channel gradient (Cg) | ✓ | ||

| Dissection index (Din) | ✓ | ||

| Hypsometric integral (HI) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Drainage density (Dd) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Stream frequency (Fs) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Infiltration number (If) | ✓ | ||

| Bifurcation ratio (Rb) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Basin length (Lb) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Perimeter (P) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Drainage texture (Dt) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Length of overland flow (Lo) | ✓ | ||

| Forest Area (km2) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Agriculture (km2) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Artificial Areas (km2) | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Area (A) | ✓ | ||

| Stream length (Lu) | ✓ | ||

| Mean stream length (Lm) | ✓ | ||

| Stream length ratio (Rl) | ✓ | ||

| Constant of channel maintenance (C) | ✓ | ||

| Water (km2) | ✓ | ||

| Wetlands (km2) | ✓ | ||

| Settlement Count | ✓ | ||

| Semi Natural Area (km2) | ✓ | ||

| Stream order (U) | ✓ | ||

| Stream number (Nu) | ✓ | ||

| Form factor (Ff) | ✓ | ||

| Elongation ratio (Re) | ✓ | ||

| Circulatory ratio (Rc) | ✓ | ||

| Compactness coefficient (Cc) | ✓ |

References

- Choudhari, P.P.; Nigam, G.K.; Singh, S.K.; Thakur, S. Morphometric based prioritization of watershed for groundwater potential of Mula river basin, Maharashtra, India. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2018, 2, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Gupta, A.; Singh, M. Hydrological inferences from watershed analysis for water resource management using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2014, 17, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, H.; Lokesh, K.V.; Sameena, M.; roopa, J.; Ranganna, G. GIS–Based Morphometric Analysis of Two Reservoir Catchments of Arkavati River, Ramanagaram District, Karnataka. Aquat. Procedia 2015, 4, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Gope, D. Hydro-morphometric characterization and prioritization of sub-watersheds for land and water resource management using fuzzy analytical hierarchical process (FAHP): A case study of upper Rihand watershed of Chhattisgarh State, India. Appl. Water Sci. 2021, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Das Majumdar, D.; Banerjee, S. Morphometry Governs the Dynamics of a Drainage Basin: Analysis and Implications. Geogr. J. 2014, 2014, 927176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Chintalacheruvu, M.R. Enhanced morphometric analysis for soil erosion susceptibility mapping in the Godavari river basin, India: Leveraging Google Earth Engine and principal component analysis. ISH J. Hydraul. Eng. 2023, 30, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Kumar, P.; Vishwakarma, D.K.; Ashok, A.; Elbeltagi, A.; Gupta, S.; Kuriqi, A. Watershed prioritization using morphometric analysis by MCDM approaches. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 70, 101763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sen, S.; Chauhan, P. Geo-morphometric prioritization of Aglar micro watershed in Lesser Himalaya using GIS approach. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 7, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, S.A.; Ajeez, S.A.; Aruchamy, S.; Jegankumar, R. Prioritization of Sub Watershed Based on Morphometric Characteristics Using Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process and Geographical Information System—A Study of Kallar Watershed, Tamil Nadu. Aquat. Procedia 2015, 4, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.S.; Patel, K.; Pendem, S.; Shrivatra, N. Morphometric Analysis and Prioritization of Sub-watersheds for Management of Natural Resources using GIS: A case study of Rajasthan, India. Int. J. Adv. Remote Sens. GIS 2020, 9, 3321–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramani, K.; Gomathi, M.; Bhaskaran, G.; Kumaraswamy, K. GIS-based spatial multi-criteria approach for characterization and prioritization of micro-watersheds: A case study of semi-arid watershed, South India. Appl. Geomat. 2019, 11, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketema, A.; Dwarakish, G.S. Prioritization of sub-watersheds for conservation measures based on soil loss rate in Tikur Wuha watershed, Ethiopia. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankriti, R.; Subbarayan, S.; Aluru, M.; Devanantham, A.; Reddy, N.; Ayyakkannu, S. Morphometric analysis and prioritization of sub-watersheds of Himayatsagar catchment, Ranga Reddy District, Telangana, India using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Khanday, M.Y.; Rais, S. Watershed prioritization using morphometric and land use/land cover parameters: A remote sensing and GIS based approach. J. Geol. Soc. India 2011, 78, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekar, P.R.; Mathew, A.; Arun, P.S.; Gopi, V.P. Sub-watershed prioritization using morphometric analysis, principal component analysis, hypsometric analysis, land use/land cover analysis, and machine learning approaches in the Peddavagu River Basin, India. J. Water Clim. Change 2023, 14, 2055–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.; Kumar, P.; Sarkar, P. Morphometric parameters based prioritization of a Mid-Himalayan watershed using fuzzy analytic hierarchy process. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 280, 10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.; Ramasamy, J. Morphometric assessment and prioritization of the South India Moyar river basin sub-watersheds using a geo-computational approach. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2024, 8, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namwade, G.; Trivedi, M.M.; Tiwari, M.K.; Patel, G.R.; Srinivas, B. Analysis of significant morphometric parameters and sub-watershed prioritization using PCA and PCA-WSM for soil conservation. Pharma Innov. J. 2023, 12, 2313–2324. [Google Scholar]

- Pande, C.B.; Moharir, K. GIS based quantitative morphometric analysis and its consequences: A case study from Shanur River Basin, Maharashtra India. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R.K.; Das Chatterjee, N.; Das, K. Multi-criteria-based sub-basin prioritization and its risk assessment of erosion susceptibility in Kansai–Kumari catchment area, India. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, Y.; Anaba, O. A Remote Sensing and GIS Approach for Prioritization of Wadi Shueib Mini-Watersheds (Central Jordan) Based on Morphometric and Soil Erosion Susceptibility Analysis. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2016, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Sajjad, H.; Masroor, M.; Saha, T.K.; Roshani; Rahaman, M.H. Morphometric parameters based prioritization of watersheds for soil erosion risk in Upper Jhelum Sub-catchment. India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavian, A.; Mirzaei, S.N.; Choubin, B.; Kalehhouei, M.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Mapping sediment mobilization risks: Prioritizing results obtained at watershed and sub-watershed scales. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024, 12, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Sajjad, H.; Husain, I. Morphometric Parameters-Based Prioritization of Sub-watersheds Using Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process: A Case Study of Lower Barpani Watershed, India. Nat. Resour. Res. 2018, 27, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhir, T.O.; O’Connor, R.; Penner, P.R.; Goodwin, D.W. A watershed-based land prioritization model for water supply protection. For. Ecol. Manag. 2001, 143, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekar, P.R.; Mathew, A. Prioritising sub-watersheds using morphometric analysis, principal component analysis, and land use/land cover analysis in the Kinnerasani River basin, India. H2Open J. 2022, 5, 490–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godif, G.; Manjunatha, B.R. Prioritizing sub-watersheds for soil and water conservation via morphometric analysis and the weighted sum approach: A case study of the Geba river basin in Tigray, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R.K.; Ghosh, N.C.; Lohani, A.K.; Thomas, T. Fuzzy AHP Based Multi Crteria Decision Support for Watershed Prioritization. Water Resour. Manag. 2015, 29, 4205–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M. Hybrid model approach for hilly sub-watershed prioritization using morphometric parameters: A case study from Bakkhali river watershed in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Khanday, M.Y.; Ahmed, R. Prioritization of sub-watersheds based on morphometric and land use analysis using Remote Sensing and GIS techniques. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2009, 37, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govarthanambikai, K.; Sathyanarayan Sridhar, R. Prioritization of watershed using morphometric parameters through geospatial and PCA technique for Noyyal River Basin, Tamil Nadu, India. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 1218–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hc, H.; Govindaiah, S.; Srikanth, L.; Surendra, H. Prioritization of sub-watersheds of the Kanakapura Watershed in the Arkavathi River Basin, Karnataka, India-using Remote sensing and GIS. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2021, 5, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, I.D.; Grayson, R.B.; Ladson, A.R. Digital terrain modelling: A review of hydrological, geomorphological, and biological applications. Hydrol. Process. 1991, 5, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.P.; Gajjar, C.A.; Srivastava, P.K. Prioritization of Malesari mini-watersheds through morphometric analysis: A remote sensing and GIS perspective. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 69, 2643–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawmchullova, I.; Rao, C.U.B.; Rinkimi, L. Prioritization of sub-watersheds in Tuirial river basin through geo-environment integration and morphometric parameters. Arab. J. Geosci. 2024, 17, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, Y. Morphometric Assessment of Wadi Wala Watershed, Southern Jordan Using ASTER (DEM) and GIS. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2017, 9, 158–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aher, P.D.; Adinarayana, J.; Gorantiwar, S.D. Quantification of morphometric characterization and prioritization for management planning in semi-arid tropics of India: A remote sensing and GIS approach. J. Hydrol. 2014, 511, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshani, R.; Zaresefat, M.; Nikpeyman, V.; Ghaseminejad, A.; Shafieibafti, S.; Rashidi, A.; Nemati, M.; Raoof, A. Machine Learning-Based Assessment of Watershed. Land 2023, 12, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarafza, M.; Azarafza, M.; Akgün, H.; Atkinson, P.M.; Derakhshani, R. Deep learning-based landslide susceptibility mapping. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenini, I.; Ben Mammou, A.; El May, M. Groundwater recharge zone mapping using GIS-based multi-criteria analysis: A case study in Central Tunisia (Maknassy Basin). Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.T.; Shahabi, H.; Shirzadi, A.; Chapi, K.; Pradhan, B.; Chen, W.; Khosravi, K.; Panahi, M.; Bin Ahmad, B.; Saro, L. Land subsidence susceptibility mapping in South Korea using machine learning algorithms. Sensors 2018, 18, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Kornejady, A.; Zhang, N. Landslide spatial modeling: Introducing new ensembles of ANN, MaxEnt, and SVM machine learning techniques. Geoderma 2017, 305, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, A.; Madramootoo, C.A.; Enright, P.; Prasher, S.O.; Patel, R.M. Performance evaluation of ANN and geomorphology-based models for runoff and sediment yield prediction for a Canadian watershed. Curr. Sci. 2005, 89, 2022–2033. [Google Scholar]

- Maulud, D.; Abdulazeez, A.M. A Review on Linear Regression Comprehensive in Machine Learning. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends 2020, 1, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Dwivedi, S.B.; Gaur, S. A comparative study of machine learning and Fuzzy-AHP technique to groundwater potential mapping in the data-scarce region. Comput. Geosci. 2021, 155, 104855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaresefat, M.; Derakhshani, R.; Nikpeyman, V.; GhasemiNejad, A.; Raoof, A. Using Artificial Intelligence to Identify Suitable Artificial Groundwater Recharge Areas for the Iranshahr Basin. Water 2023, 15, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.; Puri, L.; Bist, S.P.; Bastola, A.P.; Acharya, B. Watershed prioritization of Kailali district through morphometric parameters and landuse/landcover datasets using GIS. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aytekin, M.; Serengil, Y. Assessment of Vulnerability, Resilience Capacity and Land Use Within the Scope of Climate Change Adaptation: The Case of Balıkesir-Susurluk Basin. Kastamonu Üniversitesi Orman Fakültesi Derg. 2022, 22, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahler, A.N. Quantitative geomorphology of drainage basins and channel networks. In Handbook of applied hydrology; Chow, V.T., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1964; pp. 439–476. ISBN 1433-7851. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, B.Y.R.E. Erosional Development of Streams and Their Drainage Basins; Hydrophysical Approach to Quantitative Morphology. GSA Bull. 1945, 56, 275–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumm, S.A. Evolution of drainage systems and slopes in badlands at Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1956, 67, 597–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooka Ratnam, K.; Srivastava, Y.K.; Venkateswara Rao, V.; Amminedu, E.; Murthy, K.S.R. Check Dam positioning by prioritization micro-watersheds using SYI model and morphometric analysis—Remote sensing and GIS perspective. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2005, 33, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.E. Drainage-basin characteristics. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1932, 13, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.C. A Quantitative Geomorphic Study of Drainage Basin Characteristics in the Clinch Mountain Area, Virginia and Tennessee; Department of Geology Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Gravelius, H. Grundriß der gesamten Gewässerkunde. Band I: Flußkunde [Compendium of Hydrology, Vol. I. Rivers]; Göschen: Berlin, Germany, 1914; Volume I, ISBN 9783112452356. (In Germany) [Google Scholar]

- Faniran, A. The Index of Drainage Intensity—A Provisional New Drainage Factor. Aust. J. Sci. 1968, 31, 328–330. [Google Scholar]

- Melton, M.A. The Geomorphic and Paleoclimatic Significance of Alluvial Deposits in Southern Arizona. J. Geol. 1965, 73, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broscoe, A.J. Quantitative Analysis of Longitudinal Stream Profiles of Small Watersheds; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, R.J.; Wilson, S.E. Elevation-relief ratio, hypsometric integral, and geomorphic area-altitude analysis. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 1971, 82, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.F.; Snell, J.B.A. A Quantitative System for Classifying Landforms; Technical Report EP-124; Environmental Protection Research Division, Quartermaster Research & Engineering Command, U.S. Army Natick Laboratories: Natick, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- EU-DEM (European Digital Elevation Model) 2016: Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/imagery-in-situ/eu-dem/eu-dem-v1.1 (accessed on 15 February 2019).

- CORINE, Copernicus Pan-European Land Monitoring Service, 2018. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/pan-european/corine-land-cover/clc2018 (accessed on 26 January 2018).

- OpenStreetMap Contributors. Retrieved via Overpass Turbo. Available online: https://planet.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räth, Y.M.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Jiao, C.; Wu, S.; van Strien, M.J. Settlement relationships and their morphological homogeneity across time and scale. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Python Software Foundation, P.S. Python Language Reference. Version: 3.11.13, 2025. Available online: https://www.python.org/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Google LLC. Google Colaboratory. Available online: https://colab.research.google.com/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Google. Gemini (Version 2.5). Integrated in Google Colab. Google AI, 2025. Available online: https://colab.research.google.com/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Pandas Development Team. pandas: Python Data Analysis Library (Version 2.2.2). Available online: https://pandas.pydata.org/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; Volume 1, pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, R.L.; Longnecker, M. An Introduction to Statistical Methods and Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781305269477. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, K. LIII. On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1901, 2, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotelling, H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J. Educ. Psychol. 1933, 24, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.W. Asymptotic Theory for Principal Component Analysis. Ann. Math. Stat. 1963, 34, 122–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.R. The use and interpretation of principal component analysis in applied research. Sankhyā Indian J. Stat. 1964, 26, 329–358. [Google Scholar]

- Gower, J.C. Some Distance Properties of Latent Root and Vector Methods Used in Multivariate Analysis. Biometrika 1966, 53, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, J.N.R. Two Case Studies in the Application of Principal Component Analysis. Appl. Stat. 1967, 16, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisendorfer, R.W. Principal Component Analysis in Meteorology and Oceanography; Mobley, C.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 0444430148. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications: A State-of-the-Art Survey; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; ISBN 9783642483189. [Google Scholar]

- Madanchian, M.; Taherdoost, H. A comprehensive guide to the TOPSIS method for multi-criteria decision making. Sustain. Soc. Dev. 2023, 1, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.I.; Pan, N. Das Flood susceptibility assessment of Jhelum River Basin: A comparative study of TOPSIS, VIKOR and EDAS methods. Geosyst. Geoenviron. 2024, 3, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, L.; Han, Q.; Wang, X.; Zou, T.; Fan, C. Estimation of Remote Sensing-Based Ecological Index along the Grand Canal Based on PCA–AHP–TOPSIS Methodology. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Barham, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; Ghemawat, S.; Irving, G.; Isard, M.; et al. TensorFlow: A System for Large-Scale Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, Savannah, GA, USA, 2–4 November 2016; pp. 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Keras Team. Keras. 2015. Available online: https://keras.io (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskom, M. Seaborn: Statistical Data Visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V.N. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1995; Volume 38, ISBN 9781475724400. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A Decision-Theoretic Generalization of On-Line Learning and an Application to Boosting. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1997, 55, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B.J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Additive logistic regression: A statistical view of boosting. Ann. Stat. 2000, 28, 337–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Haque, I.; Lu, H.; Moni, M.A.; Gide, E. Comparative performance analysis of K-nearest neighbour (KNN) algorithm and its different variants for disease prediction. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, S.; Cerpa, N. Artificial Neural Networks. In Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology; Meyers, R.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 631–645. ISBN 9781522522553. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.K.; Murty, M.N.; Flynn, P.J. Data clustering: A review. ACM Comput. Surv. 1999, 31, 264–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Abassi, M.; Ousmana, H.; Saouita, J.; El-Hmaidi, A.; Iallamen, Z.; Jaddi, H.; Aouragh, M.H.; Boufala, M.; Kasse, Z.; El Ouali, A.; et al. The combination of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) and morphometric parameters for prioritizing the erodibility of sub-watersheds in the Ouljet Es Soltane basin (North of Morocco). Heliyon 2024, 10, e38228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, R.; Mohir, M.M.I.; Alam, J. Watershed prioritization for soil and water conservation aspect using GIS and remote sensing: PCA-based approach at northern elevated tract Bangladesh. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avinash, K.; Jayappa, K.S.; Deepika, B. Prioritization of sub-basins based on geomorphology and morphometricanalysis using remote sensing and geographic informationsystem (GIS) techniques. Geocarto Int. 2011, 26, 569–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, A.; Kumar, K.K.; Maddamsetty, R.; Manjunatha, M.; Tangadagi, R.B.; Preethi, S. Drainage morphometry based sub-watershed prioritization of Kalinadi basin using geospatial technology. Environ. Chall. 2021, 5, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dofee, A.A.; Chand, P.; Kumar, R. Prioritization of soil erosion-prone sub-watersheds using geomorphometric and statistical-based weighted sum priority approach in the middle Omo-Gibe River basin, Southern Ethiopia. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2350198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekar, P.R.; Mathew, A. Morphometric analysis of watersheds: A comprehensive review of data sources, quality, and geospatial techniques. Watershed Ecol. Environ. 2024, 6, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekar, P.R.; Mathew, A.; Hasher, F.F.B.; Mehmood, K.; Zhran, M. Towards Sustainable Development: Ranking of Soil Erosion-Prone Areas Using Morphometric Parameters and TOPSIS Method. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Sarkar, U.; Taraphder, S.; Datta, S.; Swain, D.; Saikhom, R.; Panda, S.; Laishram, M. Multivariate Statistical Data Analysis—Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Int. J. Livest. Res. 2017, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawarni, C.; Hermiyanto, B.; Mandala, M.; Suciati, L.P.; Novita, E. Assessment of Soil Quality and Erosion Hazards Using Statistical and PCA Analysis: A Case Study of the Arjasa Subwatershed. J. Glob. Ecol. Environ. 2025, 21, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezahegn, R.; Mengistu, F. Morphometric and land use land cover analysis for the management of water resources in Guder sub-basin, Ethiopia. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, K. Prioritization of watersheds for runoff risk and soil loss based on morphometric characteristics using compound factor and topsis model. Mesop. J. Agric. 2024, 52, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chang, H. Predicting Post-Wildfire Stream Temperature and Turbidity: A Machine Learning Approach in Western U.S. Watersheds. Water 2025, 17, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.G.; Lu, D.; Gao, T.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Teng, D.; Yu, F.; Zhu, J. Climate-Smart Forestry: An AI-Enabled Sustainable Forest Management Solution for Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; Volume 36. [Google Scholar]

- Shiferaw, N.; Habte, L.; Waleed, M. Land use dynamics and their impact on hydrology and water quality of a river catchment: A comprehensive analysis and future scenario. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 4124–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Johnson, V.C.; Shi, J.; Tan, M.L.; Zhang, F. Multi-scenario land use change simulation and spatial-temporal evolution of carbon storage in the Yangtze River Delta region based on the PLUS-InVEST model. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, M.P.; Alluhaidan, A.S.; Aziz, R.; Basheer, S. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models for Detecting Water Quality Anomalies in Treatment Plants. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, T.E.; Worden, R.H.; Houghton, J.E.; Griffiths, J.; Brostrøm, C.; Martinius, A.W. Machine Learning for Reservoir Quality Prediction in Chlorite-Bearing Sandstone Reservoirs. Geosciences 2025, 15, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Dahal, D.; Bhattarai, N.; Regmi, S.M.; Sewa, R.; Kalra, A. Machine Learning-Based Flood Risk Assessment in Urban Watershed: Mapping Flood Susceptibility in Charlotte, North Carolina. Geographies 2025, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushara, A.R.; Adnan Zaman, K.T.; Fathima Misriya, P.S. Optimizing crop yield forecasting with ensemble machine learning techniques. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2025, 14, 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Mo, X. Crop Yield Time-Series Data Prediction Based on Multiple Hybrid Machine Learning Models. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2025, 133, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Morphometric and Other Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Linear morphometric parameters | |||||

| ID | Parameters | Symbol | Methods of calculation | Units | References |

| 1.1. | Stream order | U | Hierarchical ranking | Dimensionless | [49] |

| 1.2. | Stream number | Nu | Nu = N1 + N2 + … + Nn | Dimensionless | [50] |

| 1.3. | Stream length | Lu | Lu = L1 + L2 + … + Ln | km | [50] |

| 1.4. | Mean stream length | Lm | Lm = Lu/Nu | km | [49] |

| 1.5. | Stream length ratio | Rl | Rl = Lu/Lu − 1 | Dimensionless | [50] |

| 1.6. | Bifurcation ratio | Rb | Rb = Nu/Nu + 1 | Dimensionless | [50] |

| 1.7. | Basin length | Lb | Lb = 1.312 * A^0.568 | km | [51,52] |

| 2. Shape morphometric parameters | |||||

| 2.1. | Form factor | Ff | Ff = A/Lb2 | Dimensionless | [53] |

| 2.2. | Elongation ratio | Re | Re = (1.128 * A^0.5)/Lb | Dimensionless | [51] |

| 2.3. | Circulatory ratio | Rc | Rc = 4πA/P2 | Dimensionless | [54] |

| 2.4. | Compactness coefficient | Cc | Cc = P/(2 × (π * A)1/2 | Dimensionless | [50,55] |

| 2.5. | Basin of perimeter | P | GIS operation | km | [50] |

| 2.6. | Basin of area | A | GIS operation | km2 | [50] |

| 3. Areal morphometric parameters | |||||

| 3.1. | Stream frequency | Fs | Fs = Nu/A | 1/km2 | [50] |

| 3.2. | Drainage texture | Dt | Dt = Nu/P | 1/km2 | [50] |

| 3.3. | Drainage density | Dd | Dd = Lu/A | km/km2 | [50] |

| 3.4. | Infiltration number | If | If = Dd * Fs | 1/km2 | [56] |

| 3.5. | Length of overland flow | Lo | Lo = 1/(2 * Dd) | km | [50] |

| 3.6. | Constant of channel maintenance | C | C = 1/Dd | km | [51] |

| 4. Relief morphometric parameters | |||||

| 4.1. | Basin relief | R | R = H − h | Dimensionless | [51] |

| 4.2. | Relief ratio | Rr | Rr = (H − h)/Lb | Dimensionless | [51] |

| 4.3. | Ruggedness number | Rn | Rn = Dd * (H − h) | Dimensionless | [51] |

| 4.4. | Melton’s Rudgedness number | Mrn | Mrn = R/A1/2 | Dimensionless | [57] |

| 4.5. | Channel gradient | Cg | Cg = (H − h)/(π/2 * Lb) | Dimensionless | [58] |

| 4.6. | Dissection index | Din | Din = (H − h)/H | Dimensionless | [55] |

| 4.7. | Hypsometric integral | HI | HI = (Emean − Emin)/(Emax − E min) | Dimensionless | [59,60] |

| 4.8. | Mean elevation | Emean | DEM Solutions | m | [61] |

| 4.9. | Minimum elevation | Emin | DEM Solutions | m | [61] |

| 4.10. | Maximum elevation | Emax | DEM Solutions | m | [61] |

| 5. Other parameters | |||||

| 5.1. | Digital Elevation Model | EU-DEM | EU-DEM v1.1 | 30 m | [61] |

| 5.2. | Land Cover | LC | Corine Land Cover 2018 | 25 ha/100 m | [62] |

| 5.3. | Settlement Count | Sc | OSM-derived point data filtered by basin boundary in GEE | Number of settlements | [63,64,65] |

| Function | Model | MSE | R2 | MAE | Optimal Hyperparameter Values | The Best Cross-Validated Score (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFR | SVM * | 0.063 | 0.35 | 0.167 | C: 1.3838670221497307 epsilon: 0.006888133398756345 gamma: auto, kernel: rbf | 0.42 ± 0.24 |

| PBW | SVM | 0.003 | 0.87 | 0.045 | C: 10, epsilon: 0.01, gamma: scale, kernel: rbf | 0.65 ± 0.24 |

| SEW | SVM | 0.038 | 0.46 | 0.111 | C: 10, epsilon: 0.01 gamma: auto, kernel: rbf | 0.59 ± 0.22 |

| Function | Model | MSE | R2 | MAE | Optimal Hyperparameter Values | The Best Cross- Validated Score (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFR | RF | 0.081 | 0.16 | 0.209 | max depth: 18, min samples leaf: 1 min samples split: 3, n_estimators: 160 | 0.08 ± 0.26 |

| PBW | RF | 0.008 | 0.61 | 0.074 | max depth: 26, min samples leaf: 1 min samples split: 2, n_estimators: 67 | 0.57 ± 0.05 |

| SEW | RF | 0.025 | 0.64 | 0.114 | max depth: none, min samples leaf: 2 min samples split: 2, n_estimators: 50 | 0.44 ± 0.19 |

| Function | Model | MSE | R2 | MAE | Optimal Hyperparameter Values | The Best Cross- Validated Score (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFR | GBM | 0.084 | 0.13 | 0.209 | learning rate: 0.01, max depth: 5 min sample leaf: 1, min sample split: 10 n estimators: 200 | −0.002 ± 0.232 |

| PBW | GBM | 0.007 | 0.68 | 0.066 | learning rate: 0.1, max depth: 5 min sample leaf: 1, min sample split: 10 n estimators: 200 | 0.60 ± 0.05 |

| SEW | GBM | 0.022 | 0.69 | 0.104 | learning rate: 0.1331, max depth: 5 min sample leaf: 2, min sample split: 2 n estimators: 177 | 0.44 ± 0.22 |

| Function | Model | MSE | R2 | MAE | Optimal Hyperparameter Values | The Best Cross- Validated Score (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFR | KNN | 0.076 | 0.21 | 0.175 | n neighbors: 4, p: 1, weights: distance | 0.23 ± 0.09 |

| PBW | KNN | 0.013 | 0.39 | 0.086 | n neighbors: 3, p: 1, weights: distance | 0.36 ± 0.22 |

| SEW | KNN | 0.064 | 0.09 | 0.162 | n neighbors: 4, p: 2, weights: distance | 0.25 ± 0.14 |

| Function | Model | MSE | R2 | MAE | Optimal Hyperparameter Values | The Best Cross- Validated Score (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFR | ANN | 0.028 | 0.71 | 0.127 | activation: relu, alpha: 0.00843 hidden layer sizes: [80, 118] learning rate: adaptive | 0.31 ± 0.23 |

| PBW | ANN | 0.010 | 0.56 | 0.079 | activation: tanh, alpha: 0.00366 hidden layer sizes: [88, 54] learning rate: constant | −0.39 ± 0.62 |

| SEW | ANN | 0.035 | 0.36 | 0.128 | activation: relu, alpha: 0.001 hidden layer sizes: [80, 118] learning rate: adaptive | 0.36 ± 0.38 |

| Function | Model | MSE | R2 | MAE | Optimal Hyperparameter Values | The Best Cross- Validated Score (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBW | SVM | 0.003 | 0.87 | 0.045 | C: 10, epsilon: 0.01, gamma: scale, kernel: rbf | 0.65 ± 0.24 |

| PBW | RF | 0.008 | 0.61 | 0.074 | max depth: 26, min samples leaf: 1 min samples split: 2, n_estimators: 67 | 0.57 ± 0.05 |

| SEW | RF | 0.025 | 0.64 | 0.114 | max depth: none, min samples leaf: 2 min samples split: 2, n_estimators: 50 | 0.44 ± 0.19 |

| PBW | GBM | 0.007 | 0.68 | 0.066 | learning rate: 0.1, max depth: 5 min sample leaf: 1, min sample split: 10 n estimators: 200 | 0.60 ± 0.05 |

| SEW | GBM | 0.022 | 0.69 | 0.104 | learning rate: 0.1331, max depth: 5 min sample leaf: 2, min sample split: 2 n estimators: 177 | 0.44 ± 0.22 |

| PBW | KNN | 0.013 | 0.39 | 0.086 | n neighbors: 3, p: 1, weights: distance | 0.36 ± 0.22 |

| EFR | ANN | 0.028 | 0.71 | 0.127 | activation: relu, alpha: 0.00843 hidden layer sizes: [80, 118] learning rate: adaptive | 0.31 ± 0.23 |

| PBW | ANN | 0.010 | 0.56 | 0.079 | activation: tanh, alpha: 0.00366 hidden layer sizes: [88, 54] learning rate: constant | −0.39 ± 0.62 |

| Function | Silhouette Score | Calinski-Harabasz Score | Davies-Bouldin Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| EFR | 0.63 | 185.20 | 0.46 |

| PBW | 0.64 | 270.19 | 0.40 |

| SEW | 0.61 | 207.73 | 0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aytekin, M.; Ediş, S.; Kaya, İ. A Hybrid PCA-TOPSIS and Machine Learning Approach to Basin Prioritization for Sustainable Land and Water Management. Water 2026, 18, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010005

Aytekin M, Ediş S, Kaya İ. A Hybrid PCA-TOPSIS and Machine Learning Approach to Basin Prioritization for Sustainable Land and Water Management. Water. 2026; 18(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleAytekin, Mustafa, Semih Ediş, and İbrahim Kaya. 2026. "A Hybrid PCA-TOPSIS and Machine Learning Approach to Basin Prioritization for Sustainable Land and Water Management" Water 18, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010005

APA StyleAytekin, M., Ediş, S., & Kaya, İ. (2026). A Hybrid PCA-TOPSIS and Machine Learning Approach to Basin Prioritization for Sustainable Land and Water Management. Water, 18(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010005