Abstract

Rational allocation and coordinated operation of water resources in arid inland river basins are crucial for sustaining irrigated agriculture, maintaining ecological baseflow and ensuring reservoir safety. To address this need, this study develops and evaluates joint-operation schemes for the Jingou River-Hongshan Reservoir irrigation system in Xinjiang, northwestern China, to improve coordination among irrigation water supply, ecological baseflow maintenance and reservoir safety. A monthly reservoir-canal-irrigation operation model is formulated with irrigation demands, ecological flow constraints and key engineering limits. Using this model, operating schemes are generated to explore trade-offs among three objectives: shortages, reliability and non-beneficial reservoir releases. The non-dominated schemes obtained from multi-objective optimization are then ranked using an entropy-weighted TOPSIS framework, from which representative solutions are selected for further interpretation. The results indicate that the top-ranked schemes deliver comparable and relatively well-balanced performance across the objectives. Under the preferred compromise scheme, annual irrigation shortages amount to about 39% of total demand, the mean satisfaction level of irrigation and ecological requirements reaches roughly 57%, and the combined index of spill losses and end-of-year storage deviation remains low. Schemes that push shortage reduction or reliability enhancement to extremes tend to increase spill losses, compromise storage security or both, thereby degrading overall performance. The proposed optimization-ranking framework offers a transparent basis for identifying robust operating strategies that reflect local management priorities and is transferable to other reservoir-supported irrigation systems in arid regions.

1. Introduction

Climate change and intensive human water use intensify water scarcity, making ecological flow requirements an increasingly binding constraint in reservoir operation and basin-scale allocation [1,2,3]. This challenge is particularly acute in arid and semi-arid regions, which are characterized by low precipitation, high evaporation and pronounced intra-annual and inter-annual variability of inflows, thereby increasing water-supply stress and ecological vulnerability. To alleviate supply–demand conflicts while accounting for environmental needs, previous studies have integrated water-supply and ecological objectives within unified operation frameworks. A multi-objective optimization study of the Sidaogou Reservoir in Hami demonstrated that coordinated operation for domestic water supply and ecological flow can be achieved even under limited water availability [4]. For large single and cascade reservoirs, multi-objective operation models that incorporate ecological targets have been formulated to balance hydropower benefits with downstream ecological functions [5]. In parallel reservoir systems, approaches that couple the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) with multi-criteria decision analysis have been employed for joint optimization and scheme selection [6]. The entropy-weighted Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) and related composite evaluation methods have been applied to regional water-resources carrying-capacity assessment and to the ranking of alternative water-management schemes, providing methodological support for objective evaluation under multiple objectives and indicators [7,8,9]. Applications of multi-objective evolutionary algorithms in parallel reservoir systems and other complex water-resources settings further indicate that such algorithms are well suited to high-dimensional, strongly constrained operation problems [10].

Systematic reviews indicate that multi-objective optimization and evolutionary algorithms have become important tools in river-basin planning and reservoir operation, enabling quantitative characterization of trade-offs among water supply, flood control, hydropower generation and ecological objectives [11,12,13]. Early multi-objective programming approaches laid the theoretical foundation for multi-objective reservoir operation [14], and subsequent work has achieved substantial progress in intelligent optimization and heuristic search [15]. On this basis, multi-objective approaches have been extended to conjunctive surface-water–groundwater operation [16], water-resources planning and allocation coupled with basin models such as WEAP [17], and joint operation of cascade reservoirs [18]. Studies that explicitly address uncertainty have proposed multi-scenario and multi-risk-constrained frameworks from the perspectives of flood-control risk, inflow variability and real-time operation [19,20,21]. Moreover, including downstream ecological flows and ecosystem requirements as explicit objectives has illustrated the potential for coordinated operation of reservoir groups across hydropower, water supply and ecological functions [22,23,24]. Related reviews have synthesized the application of intelligent algorithms in optimal reservoir operation [25], while case studies have proposed multi-objective models that simultaneously consider power generation, water supply and ecological requirements [26]. In addition, the coupling of multi-objective evolutionary algorithms with grey relational analysis and other decision methods has been used for multi-scheme ranking [27]. Multi-objective and multi-scenario reservoir optimization under climate-change conditions has further emphasized the importance of robust operation strategies [28].

In arid inland river basins, the above multi-objective and multi-criteria approaches are particularly relevant because water availability is highly constrained and ecosystems are fragile. Previous studies highlight that management must balance resource utilization, agricultural production and ecological security, with structural conflicts emerging between oasis irrigation expansion and ecological water demand [29,30]. Although multi-objective frameworks have been widely used for river and reservoir systems to jointly consider ecological releases and related environmental responses under changing climate conditions [31,32,33,34], translating ecological-flow knowledge into process-based, operationally implementable constraints remains challenging in many practical settings [35,36,37]. Addressing this gap is especially important in Xinjiang, where competition among agricultural, industrial, urban and ecological water uses is intensifying and where water-rights allocation and upstream–downstream coordination have become increasingly prominent issues [38]. Traditional single-objective or experience-based operation is no longer adequate to satisfy the diverse demands of multiple stakeholders. Moreover, decision-oriented scheme comparison in water-resources planning suggests that systematic, multi-indicator evaluation can improve the robustness and transparency of selecting compromise operating schemes [39].

Overall, existing research indicates that multi-objective optimization and multi-attribute decision-making for water-resources operation are relatively mature. However, for reservoir operation in typical inland river-multi-irrigation-district systems in arid regions, several important gaps remain: (i) many multi-objective models still concentrate on engineering targets such as water supply, flood control or hydropower and only weakly represent the joint effects of irrigation water-demand processes, canal conveyance capacities and process-based ecological flow constraints; (ii) integrated “optimization-evaluation” decision frameworks that map the Pareto solution set onto practically implementable operation schemes are not yet fully developed; and (iii) empirical studies for representative inland river basins in arid regions such as Xinjiang remain relatively scarce, so that operational experience and insights from these systems have not been fully exploited. The objective of this study is to develop and apply a joint-operation framework for the Jingou River-Hongshan Reservoir irrigation system in Xinjiang. Specifically, this study aims to (i) formulate a monthly joint reservoir-canal-irrigation operation model that explicitly represents irrigation water-demand processes, canal conveyance capacities and process-based ecological baseflow constraints; (ii) generate a Pareto set of non-dominated operating schemes using the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) with respect to three objectives, namely the irrigation water-shortage ratio, a water-supply reliability metric incorporating equity protection and an integrated spill-and-end-of-year storage deviation index; and (iii) employ an entropy-weighted Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) method to evaluate and rank the Pareto solutions and to identify a small number of ecologically constrained and operationally feasible operating schemes. This framework and workflow may serve as a reference for water-resources operation and ecological-flow integration in Xinjiang and other arid inland river basins.

2. Study Area

2.1. Project Overview

The Jingou River Basin is located along the northern piedmont belt of the Tianshan Mountains in the central-western part of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, forming part of the inland river system on the southern margin of the Junggar Basin and draining toward the Shihezi oasis. The upper reaches are primarily recharged by alpine glacier and snowmelt water, supplemented by precipitation, while the middle and lower reaches traverse gobi surfaces, alluvial fans and oasis irrigation districts, forming a typical “mountain-river-oasis-desert” transition zone in an arid inland environment. The basin has a cold-arid climate; according to the Köppen–Geiger climate classification, the Shihezi area is characterized as a cold semi-arid (steppe) climate (BSk).

The average annual air temperature is about 5.2 °C, and the average annual precipitation is approximately 280–285 mm, whereas potential evaporation exceeds 2000 mm. The multi-year average runoff of the Jingou River Basin is about 3.2 × 108 m3, with a highly uneven intra-annual distribution in which most of the flow occurs during the flood season (June–August). Considerable inter-annual variability further accentuates the mismatch between water availability and demand, leading to strong dependence on the annual regulation capacity of reservoirs and associated regulating works. Unless otherwise stated, the above hydro-meteorological and runoff statistics are based on multi-year records provided by the Xinjiang Jingou River Basin Water Conservancy Management Center. Within the downstream oasis plain, land resources are relatively favorable, but natural vegetation is sparse, and water resources are scarce; water use is dominated by irrigation, and studies for the broader Manas River Basin indicate that agricultural water consumption accounts for more than 90% of total water use. Consequently, the Jingou River-Hongshan Reservoir system exhibits pronounced operational conflicts among irrigation water supply, ecological baseflow maintenance and reservoir storage safety under rigid reservoir and canal conveyance constraints, making it a representative case for developing and testing joint-operation optimization and scheme-selection frameworks.

The Hongshan Reservoir is situated near the mountain outlet of the Jingou River and functions as the key water-control project for regulating river runoff and serving the downstream irrigation districts and other water-use sectors. The reservoir possesses annual storage regulation capacity, with a total storage capacity of about 5.3 × 107 m3, and is operated to satisfy multiple purposes, including (i) agricultural irrigation, (ii) municipal and industrial water supply, (iii) local flood control and (iv) ecological baseflow releases to the downstream channel. Through spillways, bottom outlets, diversion works and the associated network of main and branch canals, the Hongshan Reservoir and the downstream irrigation districts form an integrated “reservoir-canal-farmland” water-delivery and distribution system.

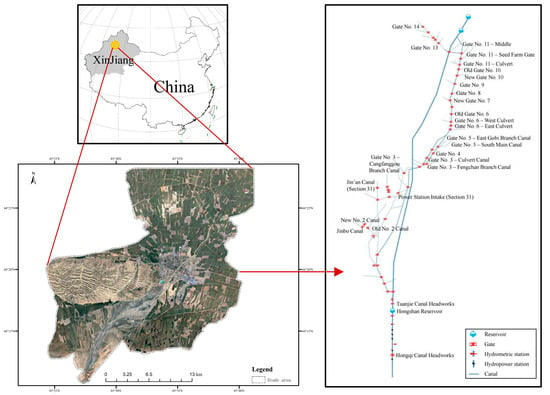

Figure 1 provides a combined view of the study area and the Jingou River-Hongshan Reservoir irrigation system, including the geographic location of the basin in Xinjiang and China, an aerial view of the downstream oasis irrigation area and the topological structure of the “reservoir-canal-farmland” water-delivery network. The schematic identifies the reservoir, trunk and branch canals and the associated irrigation command areas. The canal headworks and control gates that withdraw water for irrigation and other uses are explicitly labeled and are treated as water-demand nodes in the subsequent modelling. These geographic, hydrological and engineering characteristics directly underpin the formulation of reservoir storage and release constraints, canal conveyance-capacity constraints and irrigation water-demand processes considered in the optimization model.

Figure 1.

Location and layout of the Jingou River-Hongshan Reservoir irrigation system in Xinjiang, China, showing an aerial view of the downstream oasis area and the schematic reservoir–canal–gate network.

2.2. Problem Identification

The Jingou River-Hongshan Reservoir system faces a coupled multi-objective scheduling challenge shaped by the hydrological characteristics of meltwater-fed inflows, the physical limits of the reservoir-canal system and diverse downstream water-use demands. The key issues can be summarized as follows:

- Pronounced temporal mismatches between concentrated glacier-snowmelt inflows and stage-dependent irrigation demands;

- Conflicts among agricultural supply, ecological baseflow requirements and canal-conveyance constraints under rigid reservoir and channel capacities;

- Insufficient consideration of hydrological uncertainty, demand fluctuations and parameter errors in existing operation frameworks;

- Lack of an objective and transparent mechanism for selecting feasible operational schemes from multi-objective Pareto solution sets.

Within this management context, three intertwined operational conflicts are particularly prominent: (i) meeting seasonally concentrated irrigation demands under highly variable meltwater-fed inflows; (ii) satisfying prescribed downstream ecological baseflow requirements while irrigation withdrawals dominate water use and (iii) maintaining sufficient storage buffer to ensure operational safety and subsequent regulation capacity. Accordingly, the three objectives are formulated to directly reflect these conflicts. Minimizing the irrigation water-shortage ratio represents the agricultural supply–demand gap; maximizing water-supply reliability emphasizes stable and fair service across irrigation districts and minimizing the integrated spill-and-end-of-year storage deviation index promotes prudent storage regulation by reducing non-beneficial releases while retaining an appropriate end-of-year storage level for inter-period regulation.

On this basis, the subsequent sections formulate the optimization and evaluation workflow. This study adopts a deterministic, single-year (2024) monthly operation setting. Uncertainties in inflows, irrigation demands and ecological-flow assumptions are not explicitly propagated in the present framework; future work can extend the analysis using multi-year datasets and scenario-based or stochastic optimization.

2.3. Data and Preprocessing

The Xinjiang Jingou River Basin Water Conservancy Management Center provided the data used in this study, including measured water-supply records for 26 canal gates and the corresponding engineering design parameters. Records for 2024 were selected as the basic input dataset for the multi-objective joint-operation model because they are complete and up to date and thus reflect the current water-supply-demand pattern and operational status of the reservoir-irrigation system. All data were organized at a monthly time step and subjected to basic quality control, including checks for missing values, outliers and internal consistency.

2.3.1. Annual Water-Supply Magnitude and Seasonal Pattern

According to the monthly records of all gates in 2024, the total annual water diversion within the Jingou River system is approximately 2.5 × 108 m3 (data provided by the Xinjiang Jingou River Basin Water Conservancy Management Center; monthly totals aggregated from gate-operation records, unless otherwise stated). The water-supply process shows a pronounced seasonal pattern. From January to March, the diverted volume is small and mainly used for domestic and local purposes. With the onset of irrigation in April, water use increases rapidly; June–July form the annual peak period and account for a large share of the total annual diversion. After September, as major crops reach maturity, the diverted volume declines, and most irrigation districts effectively cease diversion from October to December. These statistics characterize the “spring irrigation plus summer growing-season irrigation” regime at the annual scale and provide a constraint for constructing the monthly irrigation-demand processes in the model.

2.3.2. Representative Gate-Demand Processes

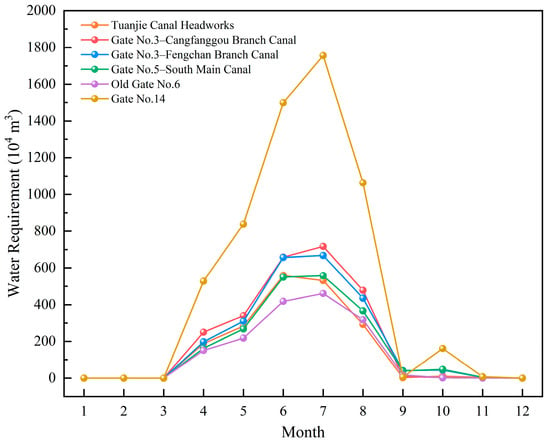

To highlight the temporal characteristics of irrigation demand in different districts and avoid overcrowding figures with all 26 time series, the gates were first ranked in descending order by their annual diverted volume. The results show that six gates—No. 14 Gate, No. 3 Gate-Cangfanggou Branch, No. 3 Gate-Fengchan Canal, No. 5 Gate-South Main Canal, Tuanjie Canal Headworks and Old No. 6 Gate—have annual diversions of approximately 5.86 × 107, 2.46 × 107, 2.36 × 107, 2.00 × 107, 1.87 × 107 and 1.59 × 107 m3, respectively. Their combined diversion is about 1.61 × 108 m3, accounting for roughly 65% of the total annual diversion of the Jingou River system in 2024. These gates cover the main canal and key branch canals and undertake the majority of irrigation supply and are, therefore, considered representative.

On this basis, the above six gates were selected as typical examples, and their monthly water-supply processes for 2024 are plotted in Figure 2. All representative gates exhibit a similar seasonal pattern: diversions start to increase markedly in April, remain at high levels during May–July, decline slightly in August and drop rapidly after September, approaching zero from October to December. Among them, No. 14 Gate has a much larger peak diversion than the others and serves as one of the most important control nodes in the system. No. 3 Gate-Fengchan Canal, No. 3 Gate-Cangfanggou Branch and No. 5 Gate-South Main Canal also show high diversion volumes in the high-flow season and play a key role in supplying the main irrigation districts. Tuanjie Canal Headworks and Old No. 6 Gate have slightly lower annual volumes but relatively smooth processes and mainly provide regional and supplementary water supply. Overall, the representative gate-demand processes capture the temporal concentration and staging of irrigation demand in the study area and are used to construct typical demand patterns in the operation model.

Figure 2.

Monthly irrigation water demands of major canal gates in 2024.

2.3.3. Gate Capacities and Irrigation Service Areas

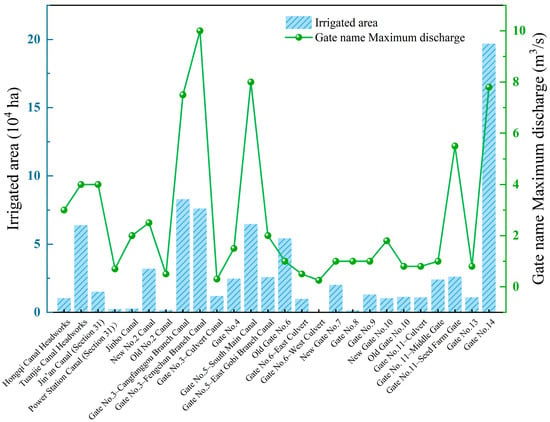

In addition to the demand processes, engineering parameters were compiled for each gate, including the maximum design discharge capacity (m3/s) and the associated irrigated area (hm2). The maximum discharge reflects the upper bound of canal conveyance capacity at each gate, whereas the irrigated area indicates the spatial extent of the service command area and the scale of water-supply tasks. Figure 3 shows that several gates—such as Gate No. 3-Fengchan Branch Canal, Gate No. 3-Cangfanggou Branch Canal, Gate No. 5-South Main Canal and Gate No. 14—have both large maximum discharges and extensive service areas and thus function as backbone nodes in the system. In contrast, some culvert or minor branch gates have relatively small capacities and serve only local or supplemental irrigation needs. The combinations of maximum discharge and irrigated area reveal clear differences in the importance and constraint strength of individual gates in the subsequent optimization, which are represented in the model through conveyance-capacity constraints and weighting of irrigation-demand objectives.

Figure 3.

Irrigated area and maximum discharge capacity at major canal gates.

2.3.4. Reservoir Storage Conditions and Operating Constraints

As the key control structure in the Jingou River system, the Hongshan Reservoir is the primary water source in the joint operation model. Based on design documents and the 2024 operating records, the reservoir storage corresponding to the normal water level is adopted as the upper operating bound, and the dead storage is taken as the lower bound. The initial storage at the beginning of the year and the target storage at the end of the year are specified according to actual operating practice, reflecting the basic requirements for within-year regulation and carry-over storage. In addition, a representative monthly inflow series is derived from long-term hydrological records, and monthly evaporation losses from the reservoir surface are estimated from observations or empirical relationships.

Downstream ecological water requirements were specified based on regional water-resources and ecological protection plans and on previous ecological-flow assessments for arid inland rivers in Xinjiang [2,35,36,37]. For the operating year considered, the total ecological release requirement for Hongshan Reservoir is 6.98 × 107 m3, while evaporation losses from the reservoir surface are about 9.94 × 105 m3. Reservoir storage parameters include a total storage capacity of about 5.344 × 107 m3, with approximately 4.737 × 107 m3 at normal water level and about 7.01 × 106 m3 as dead storage. Together with the monthly inflow series, initial and target storage and the irrigation-demand processes and gate conveyance capacities described above, these datasets constitute the inputs for the subsequent joint-operation optimization.

3. Methodology

3.1. Multi-Objective Operation Model

3.1.1. Objective Functions

A multi-objective optimization model is developed for the joint operation of the Jingou River-Hongshan Reservoir system, with the aim of coordinating irrigation water supply for 26 irrigation districts and ecological releases at the reservoir outlet over a one-year horizon. The model explicitly considers reservoir water balance, storage capacity limits, canal conveyance capacities and ecological flow requirements. Three objectives are formulated in minimization form:

- The system-wide irrigation water shortage rate;

- The comprehensive water-supply reliability;

- An objective associated with spill discharge and end-of-year storage deviation.

- (1)

- Irrigation water shortage objective

Let () denote the irrigation water demand of district in month , () denote the diversion volume from the reservoir to district and denote the combined conveyance and field application efficiency. The effective water volume delivered to the field is defined as

The system-wide volumetric irrigation water shortage ratio is expressed as

where is the number of irrigation districts and is the number of months. Minimizing reduces the annual total irrigation deficit and reflects the overall adequacy of the water supply within the reservoir-irrigation system.

- (2)

- Comprehensive water-supply reliability objective

To capture both temporal stability and spatial equity of irrigation water distribution, a continuous satisfaction index is constructed for all demand-positive cells. Define the index set as

For each , the cell-wise satisfaction is defined as

The mean satisfaction over all cells in and the 10th percentile are given by

where is the number of elements in and denotes the 10th percentile operator. A composite reliability index is then defined as

with in this study to emphasize the overall level while still accounting for the worst-served cells.

For consistency with the minimization framework, the second objective is written as

Decreasing corresponds to improving both the global reliability and the protection of relatively poorly supplied districts and periods, complementing the volumetric shortage objective .

- (3)

- Spill discharge and end-of-year storage deviation objective

To avoid unnecessary spill (or other non-irrigation releases) and to maintain a rational carry-over storage for the subsequent year, the third objective is formulated based on the annual non-irrigation release and the deviation of end-of-year storage from a target value. Let () denote the monthly non-irrigation release (including ecological baseflow and possible surplus spill) in month , () denote the reservoir storage at the end of the last month and () denote the target end-of-year storage. Then

where is a weighting coefficient reflecting the relative importance assigned to approaching the target storage. In practice, the magnitude of is rescaled internally in the optimization procedure so that all three objectives are of comparable numerical order. Overall, penalizes both excessive non-irrigation releases and large deviations from the desired end-of-year storage, thereby promoting efficient use of inflow and stable reservoir operation.

3.1.2. Constraints

To ensure physical feasibility and operational practicality, the decision variables , and are subject to the following constraints.

- (1)

- Mass balance constraint

The monthly evolution of reservoir storage must satisfy the water balance equation:

where () is the total inflow to the reservoir and () is the evaporation loss from the reservoir surface in month . The initial storage () is prescribed as at the beginning of the year. Here, the summation applies only to the irrigation diversions ; the non-irrigation release and evaporation loss enter separately.

- (2)

- Storage operating bounds

Reservoir storage is constrained within an admissible operating range with a safety margin:

where () and () denote the dead storage and the upper operating storage, respectively, and () is a protective buffer to avoid long-term operation near limiting storage levels.

In addition, an acceptable interval for the terminal storage is specified as

where () and () are determined according to engineering requirements for subsequent-year water supply and flood control.

- (3)

- Canal capacity constraints

The monthly diversions from the reservoir to each irrigation district are limited by the design discharge capacities of the canals and headworks:

where () is the maximum allowable diversion volume for gate in month . The corresponding effective irrigation supply is given by

- (4)

- Ecological and downstream release constraints

To maintain ecological baseflow and essential downstream water uses in the Jingou River, the monthly non-irrigation release is subject to a lower bound:

where () is the prescribed minimum ecological flow requirement for month , expressed in volumetric form over the monthly time step.

- (5)

- Release variation (ramping) constraints

To avoid excessive inter-month fluctuations that may affect canal safety and on-farm water management, the change in diversion to each irrigation district is limited by

where () is the maximum allowable monthly change in diversion for gate , typically specified as a fraction of its design capacity.

- (6)

- Non-negativity and feasibility

All decision variables must be non-negative and satisfy the above physical and operational constraints simultaneously:

To ensure the physical feasibility and operational practicality of the joint operation scheme, the decision variables , and are subject to the following constraints.

3.2. Solving Algorithm

3.2.1. NSGA-II-Based Multi-Objective Optimization

The multi-objective reservoir-irrigation operation problem is addressed using the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), a widely applied evolutionary algorithm for continuous and constrained water-resources optimization [13]. In the present application, each candidate operating policy is encoded as a real-valued decision vector comprising the monthly irrigation releases to all irrigation districts, the monthly non-irrigation releases and the end-of-month reservoir storage volumes over the annual horizon. Such real-coded representation, which has been adopted in many reservoir-operation studies, avoids artificial discretization of decision variables and allows direct manipulation of physically meaningful quantities such as releases and storage [10].

For a given decision vector, the coupled reservoir-irrigation system is simulated over the full planning period, and the three objective-function values are evaluated to characterize irrigation deficit, water-supply reliability and spill-storage performance. NSGA-II treats these objectives simultaneously without scalarization. The population is ranked according to Pareto dominance, and a crowding-distance measure is employed within each non-dominated front to preserve diversity along the trade-off surface. Parent solutions are selected by binary tournament based on rank and crowding distance, and offspring are generated through simulated binary crossover and polynomial mutation acting on the real-valued genes, following standard NSGA-II implementations in water-resources applications [9].

Constraint handling is incorporated through feasibility assessment and penalization, consistent with previous NSGA-II-based reservoir-optimization studies [18]. Candidate solutions that violate physical or operational constraints—such as reservoir mass balance, admissible storage ranges, canal-capacity limits, ecological-release requirements or ramping restrictions on inter-month release variation—are assigned penalty terms proportional to the magnitude of violation. These penalties are added to the objective values when performing non-dominated sorting, thereby degrading the effective fitness of infeasible individuals and reducing their survival probability. This approach steers the evolutionary search toward the feasible region while still permitting limited exploration near the constraint boundaries.

The algorithm is implemented with a moderately sized population and a sufficient number of generations to achieve both acceptable convergence and a well-spread approximation of the Pareto front. The population size, generation number and genetic-operator parameters were tuned through preliminary trial runs to balance convergence speed and diversity, within typical ranges reported for NSGA-II in reservoir-operation problems [17]. Upon termination, the algorithm yields a set of non-dominated operating schemes that delineate the trade-offs among irrigation performance, reliability and reservoir-operation efficiency. This Pareto-optimal set provides the candidate pool for subsequent multi-criteria ranking and selection in the decision-support analysis.

The multi-objective optimization was implemented in MATLAB R2024a using the gamultiobj solver, which adopts a controlled-elitist NSGA-II framework with crowding-distance-based diversity preservation. Based on preliminary trial runs balancing convergence, solution diversity and computational cost, the final parameter settings were population size = 300, maximum generations = 1000, crossover fraction = 0.9, mutation rate initialized at 0.05 (adaptive) and Pareto fraction = 0.4. To examine the influence of parameter choices, the algorithm was rerun under alternative parameter combinations within the ranges population size 100–300, crossover fraction 0.6–0.9, mutation rate 0.01–0.05 and Pareto fraction 0.3–0.5, yielding Pareto fronts with similar overall shapes and representative extreme solutions. Overall, the main trade-off patterns were not materially affected by reasonable parameter perturbations [40,41].

3.2.2. Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS for Ranking Pareto Solutions

To select reservoir-irrigation operating schemes with superior overall performance from the Pareto set generated by NSGA-II, an entropy-weighted TOPSIS method is applied. Assume that the non-dominated set comprises alternative schemes, each characterized by evaluation indices derived from the multi-objective optimization outcomes. These indices form the decision matrix , where denotes the value of scheme on index , with and denoting the numbers of schemes and indices, respectively.

- (1)

- Normalization of indices

For benefit-type indices, the normalized value is computed as

For cost-type indices, the transformation is reversed:

where denotes the normalized value and and denote the maximum and minimum of index across schemes The standardized matrix is, therefore, .

- (2)

- Entropy-based weight determination

The proportion of scheme on index is defined as

The information entropy of index is computed as

with the convention when .

The divergence of index is

The entropy weight is then obtained as

- (3)

- TOPSIS-based closeness coefficient

The weighted normalized matrix is constructed as

The positive and negative ideal solutions are defined as

The Euclidean distances of scheme to the ideal solutions are given by

The relative closeness coefficient is defined as

A larger value of indicates a scheme that is closer to the ideal combination of performance indices. The Pareto solutions are thus ranked in descending order of , and those with the highest closeness coefficients are selected as preferred reservoir-irrigation operating policies.

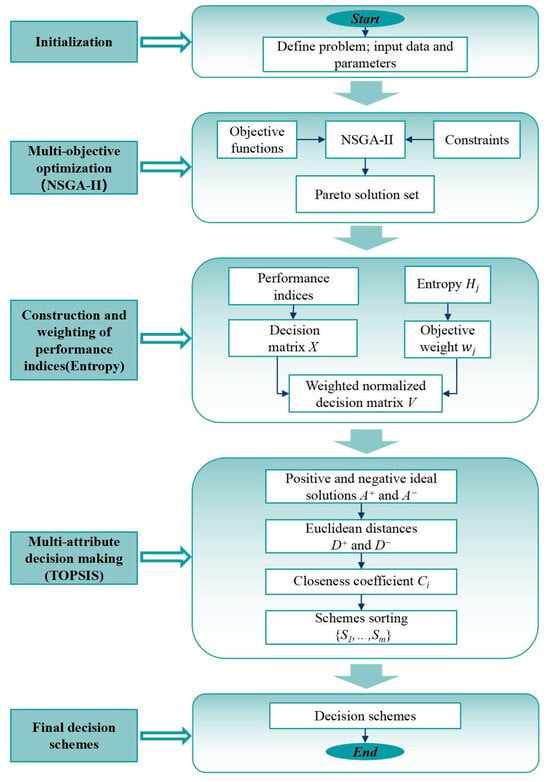

3.2.3. Integrated Decision Framework

To derive an operationally robust and practically applicable reservoir-irrigation release strategy, the non-dominated solutions produced by NSGA-II are further processed through an integrated multi-criteria decision framework that combines entropy-based indicator weighting and the TOPSIS ranking method. The framework synthesizes optimization output, objective information content and decision-maker preferences into a unified procedure for selecting a representative operating scheme from the Pareto set.

Following the generation of Pareto-optimal solutions, a set of performance indicators is constructed to reflect the multi-dimensional characteristics of each candidate scheme, including irrigation deficit, supply reliability and reservoir operation performance. These indicators form the decision matrix, which is subsequently normalized and weighted using entropy, ensuring that the contribution of each indicator is determined objectively based on inherent data dispersion rather than subjective assumptions.

The entropy-weighted normalized matrix serves as the input to the TOPSIS evaluation. By determining the positive and negative ideal solutions and computing the Euclidean distances of each scheme to these reference points, a closeness coefficient is obtained to represent the relative desirability of each alternative. Candidate schemes are then ranked according to their closeness values, allowing the identification of the solution that best approximates the ideal operational performance.

The integrated framework thus incorporates the strengths of evolutionary optimization, information-theoretic weighting and distance-based multi-criteria analysis. It provides a transparent and systematic approach for selecting a final operation scheme that balances competing objectives and reflects both hydrological performance and managerial requirements. Figure 4 summarizes the overall workflow from data preparation and model formulation to Pareto generation, scheme ranking and selection of representative operating schemes.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the modeling-optimization-ranking procedure (NSGA-II + entropy-weighted TOPSIS).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Trade-Off Characteristics of Pareto-Optimal Solutions

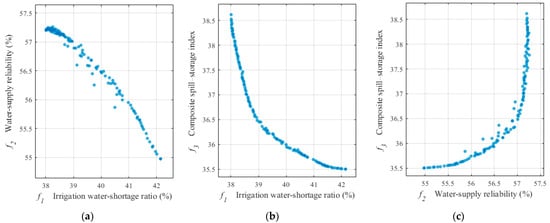

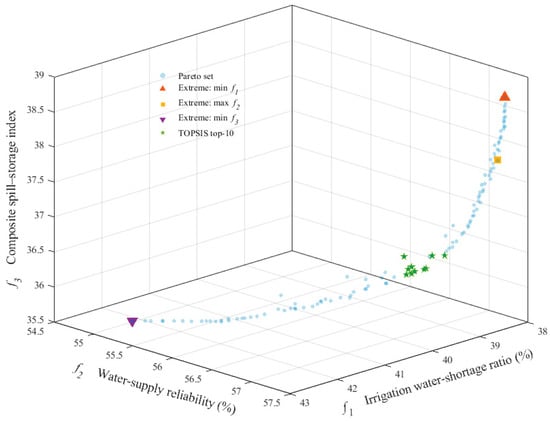

The three-objective joint operation model was solved using NSGA-II, and the resulting non-dominated solutions are plotted in the objective space in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The two-dimensional projections (Figure 5a–c) and the three-dimensional view (Figure 6) show that the Pareto set forms a continuous and slender curve in the space, indicating strong mutual dependence among the three objectives and that the main trade-off can be approximated as one dominant degree of freedom.

Figure 5.

Two-dimensional projections of the Pareto-optimal solution set in the objective space. (a) Trade-off between irrigation water-shortage ratio and water-supply reliability ; (b) trade-off between and the composite spill-storage index ; (c) trade-off between and .

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional Pareto front of non-dominated operation schemes in the (, , ) space, highlighting the TOPSIS top-10 schemes and three representative extreme schemes.

Figure 5a illustrates the relationship between the irrigation water-shortage ratio and the water-supply reliability . A clear negative correlation is observed: solutions with smaller generally exhibit higher . This indicates that, within the feasible range, reducing shortages and improving reliability are largely synergistic. However, in the low-shortage region, the curve becomes flatter, implying that further reductions in yield only limited gains in , i.e., the marginal improvement in reliability diminishes.

The projection of versus the composite spill-storage index (Figure 5b) exhibits a pronounced convex pattern. When is relatively large, decreases in the shortage ratio are accompanied by only moderate increases in . As approaches the lower end of the Pareto range, rises rapidly, indicating that achieving very low shortages requires a marked increase in spill losses, deviations from the target storage or both. A similar behavior is seen in Figure 5c, where is plotted against : increases in reliability from moderate to high levels are associated with only slight increases in , whereas pushing toward extremely high levels leads to a sharp deterioration in the spill-storage index.

The three-dimensional Pareto front in Figure 6 confirms these patterns. The non-dominated points cluster along a bent curve, with an intermediate segment where , and are relatively well balanced. Moving away from this segment toward either extreme of the curve corresponds to schemes that strongly favor either water-saving (very low ) or near-perfect reliability (very high ) at the expense of pronounced increases in . This intermediate “compromise” region, therefore, provides a natural candidate set for subsequent multi-criteria evaluation and selection of representative operating schemes.

4.2. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis of Pareto Solutions

4.2.1. Entropy-Based Determination of Criterion Weights

Taking all Pareto-optimal solutions as samples, the irrigation water-shortage ratio , the water-supply reliability and the composite spill-storage index were converted into benefit-type indices and normalized to obtain the standardized decision matrix . On this basis, the information entropy , the divergence coefficient and the corresponding entropy weight of each index were calculated, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Entropy-based weighting results for the three objectives.

Table 1 shows that the information entropies of and are slightly lower than 1, with divergence coefficients on the order of , whereas the entropy of is extremely close to 1, and its divergence coefficient is two orders of magnitude smaller, on the order of . This indicates that water-supply reliability varies only marginally within the Pareto set and remains at a consistently high level, contributing much less than the other two indices to distinguishing between alternative schemes. Consequently, the entropy weights satisfy , implying that the shortage and spill-storage objectives have a much stronger influence on scheme discrimination than reliability.

It should be emphasized that the entropy-based weight vector reflects the objective variability structure of the Pareto set rather than any managerial preference. From a modelling perspective, it reveals that, under the current hydrological and operating conditions, the trade-off among non-dominated schemes is mainly driven by the control of shortages and spill-storage deviations. At the same time, provides a data-driven baseline for the subsequent TOPSIS-based comprehensive evaluation and for weight-sensitivity analysis.

4.2.2. TOPSIS-Based Ranking of Candidate Operation Schemes

Based on the entropy-weight results, a weighted decision matrix was constructed using the irrigation water-shortage ratio , the water-supply reliability and the composite spill-storage index as evaluation indices. The entropy-weighted TOPSIS method was then applied to the 120 Pareto-optimal schemes to obtain the closeness coefficient for each scheme. Within this framework, is regarded as a comprehensive performance index: a larger value indicates that scheme is closer to the ideal solution and, therefore, performs better overall.

In terms of overall distribution, the closeness coefficients range from approximately 0.478 to 0.728, with a median of about 0.612 and first and third quartiles of about 0.552 and 0.677, respectively. This suggests that the non-dominated set obtained by multi-objective optimization is of generally high quality, while a discernible hierarchy still exists in terms of comprehensive performance. Sorting the schemes in descending order of yields a ranking of the Pareto-optimal solutions based on entropy-weighted TOPSIS.

The top-10 schemes, together with their values of , , and , are listed in Table 2. The corresponding values fall within a narrow interval of about 0.717–0.728, with the top three schemes attaining values of approximately 0.728, 0.727 and 0.726, which are clearly higher than the overall median. For these schemes, the shortage ratio lies between 0.389 and 0.394 (annual integrated shortage ratio of about 38.9–39.4%), the reliability index lies between 0.566 and 0.570 (56.6–57.0%), and the composite spill-storage index is concentrated in a narrow range of 36.22–36.48. This indicates that, under the entropy-based weighting, the best-performing schemes do not exhibit extreme bias toward any single objective but rather achieve a relatively balanced compromise among the three.

Table 2.

Top-10 Pareto-optimal schemes ranked by entropy-weighted TOPSIS and their objective values.

By contrast, some lower-ranked schemes tend to pursue near-extreme performance in a single objective—for instance, further reducing shortages or substantially increasing reliability—at the expense of spill control, storage safety or both. This trade-off causes a marked deterioration in and thus yields smaller closeness coefficients. Overall, the entropy-weighted TOPSIS ranking identifies schemes that are representative in the multi-objective sense; accordingly, the leading group can be treated as a primary candidate set for subsequent analysis of typical operating strategies and for testing ranking robustness under weight perturbations.

4.2.3. Sensitivity of Scheme Ranking to Criterion Weights

To evaluate the robustness of the comprehensive TOPSIS ranking against uncertainty in criterion weights, a structured sensitivity analysis was conducted using five weighting scenarios derived from the entropy-based results. The baseline scenario (Baseline) retained the original entropy weights, while an equal-weight scenario (Equal) was introduced to represent a neutral preference in which all three objectives are considered equally important. To examine the influence of preference shifts toward water shortage reduction, two one-at-a-time perturbation scenarios were designed by increasing and decreasing the shortage weight by 10%, respectively; in both cases, the perturbed weight was adjusted by a factor of 1.1 or 0.9, and the full weight vector was subsequently renormalized to ensure = 1 [42]. In addition, a reliability-biased scenario (Reliability-biased) was formulated by assigning a comparatively larger weight to the water-supply reliability objective , reflecting a management orientation that prioritizes stable and dependable deliveries [43]. The sensitivity of scheme ranking was then assessed by comparing the resulting orderings across scenarios, focusing on changes in the top-ranked alternatives and the overall rank consistency relative to the baseline.

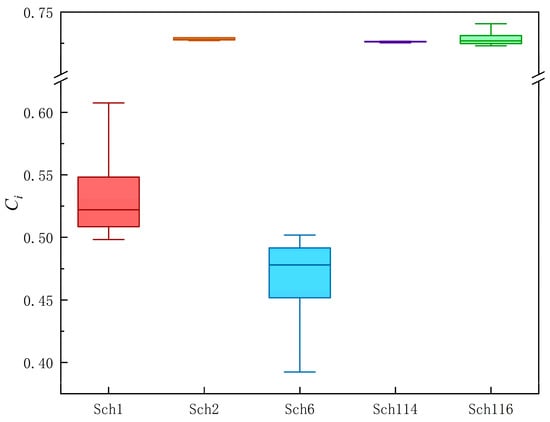

For each weighting scenario, the TOPSIS closeness coefficients of the Pareto-optimal schemes were recalculated. Table 2 reports the values of for five representative schemes—Sch1, Sch2, Sch6, Sch114 and Sch116—under the five scenarios, and Figure 7 illustrates the distribution of in the form of boxplots.

Figure 7.

Boxplots of TOPSIS closeness coefficients for five representative schemes under different weighting scenarios.

The boxplots for Sch2 and Sch114 are very narrow and located in a high-value range close to 0.73: for Sch2, varies only between about 0.727 and 0.732, and for Sch114, the total range is about 0.001. This indicates that these compromise-type schemes are highly insensitive to weight perturbations and maintain a stable, high level of comprehensive performance. Scheme Sch116 also exhibits a high median closeness (around 0.73), with ranging from roughly 0.723 to 0.741 and a slightly wider box, suggesting a certain response to weight changes but overall robust behavior.

In contrast, Sch1 and Sch6 display much wider and vertically extended boxes, indicating both lower closeness levels and stronger variability. For Sch1, ranges from about 0.498 to 0.608; the median increases markedly in the reliability-preference scenario, implying that this scheme benefits from higher weights on the reliability objective and can be regarded as reliability-oriented. For Sch6, lies between approximately 0.392 and 0.502; performance improves when more weight is assigned to the shortage objective but deteriorates under the reliability-preference scenario, reflecting a typical water-saving-oriented scheme that is highly sensitive to the weighting of objectives.

Taken together, Table 3 and Figure 7 show that, within the considered range of weight perturbations, the main variations in closeness coefficients occur for schemes that strongly favor a single objective, such as extreme water saving or extreme reliability. Schemes that achieve a more balanced compromise among the three objectives—represented here by Sch2, Sch114 and Sch116—exhibit only minor changes in both their values and their relative ranks. This suggests that the high-ranking schemes identified by the combined multi-objective optimization and entropy-weighted TOPSIS evaluation are robust with respect to reasonable variations in objective weights and can be regarded as a reliable set of representative operating strategies for further analysis and practical implementation.

Table 3.

Sensitivity of TOPSIS closeness coefficients for five representative schemes under different weighting scenarios.

4.3. Performance of Representative Operation Schemes

4.3.1. Selection of Representative Operation Schemes

The combination of multi-objective optimization and entropy-weighted TOPSIS yields a non-dominated set of 120 candidate operation schemes. Although this set provides a comprehensive description of the trade-offs among the shortage, reliability and spill-storage objectives, the number of schemes is too large for intuitive comparison and interpretation from an operational perspective. It is, therefore, necessary to extract a small number of representative schemes to support subsequent multi-indicator comparison and analysis of operational implications.

The selection of representative schemes follows three main principles. First, different types of decision preferences should be covered, including water-saving schemes that prioritize irrigation shortage control and storage safety, reliability-oriented schemes that prioritize water-supply assurance and compromise schemes that maintain a reasonably balanced performance among the three objectives. Second, the selected schemes should exhibit clearly distinguishable combinations of key objectives so that their values of shortage ratio, water-supply reliability and composite spill-storage index represent different regions of the multi-objective trade-off space. Third, the selection should be consistent with the ranking and weight-sensitivity results, giving priority to schemes that rank high in terms of the TOPSIS closeness coefficient and show relatively robust performance under weight perturbations.

According to these principles, five representative schemes were extracted from the Pareto set, denoted as Sch1, Sch2, Sch6, Sch114 and Sch116. Scheme Sch1 is characterized by a low shortage ratio and favorable spill-storage control but relatively low reliability and can be regarded as a water-saving and storage-safety-oriented scheme. Scheme Sch6 achieves higher water-supply reliability and better shortage control at the expense of larger spill and storage deviations, representing a reliability-oriented scheme. Schemes Sch2, Sch114 and Sch116 lie between these two extremes and exhibit various degrees of compromise among the three objectives. Among them, Sch2 attains the highest comprehensive closeness and can be considered a typical compromise scheme, whereas Sch114 and Sch116 are “quasi-compromise” schemes that are slightly biased towards water saving and reliability, respectively.

4.3.2. Multi-Criteria Performance Evaluation

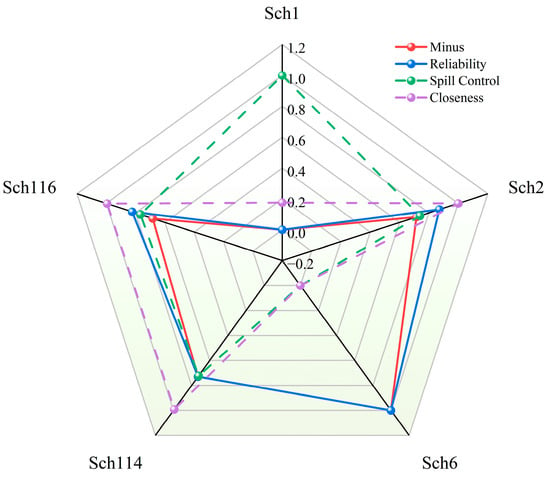

To provide an intuitive comparison of the multi-indicator performance of the representative schemes, four normalized evaluation indices were plotted together in a radar chart, as shown in Figure 8. The indices include irrigation water-supply sufficiency (denoted as Minus, obtained as the complement of the annual shortage ratio), water-supply reliability (Reliability), spill and storage-deviation control (Spill Control, transformed such that larger values indicate smaller spill and storage deviations) and the TOPSIS closeness coefficient (Closeness). All indices were linearly normalized to the interval [0, 1], with larger values indicating better performance. The five vertices correspond to the representative schemes Sch1, Sch2, Sch6, Sch114 and Sch116, while the four polylines represent the relative levels of the four indices across these schemes.

Figure 8.

Radar comparison of five representative schemes across normalized performance indices.

The shape of the polyline associated with Sch1 shows very high radial values on the sufficiency and spill-control axes and noticeably lower values on the reliability and closeness axes. This pattern indicates a scheme that prioritizes water saving and storage safety while accepting a reduction in water-supply reliability and overall closeness. In contrast, Sch6 exhibits almost the opposite configuration: it attains the highest value on the reliability axis but the lowest values on the sufficiency and spill-control axes, together with a relatively low closeness coefficient. This reflects a reliability-oriented scheme in which improved water-supply assurance is achieved at the expense of spill control and storage regularity.

The polylines for Sch2, Sch114 and Sch116 are more rounded, with intermediate-to-high radial values on all four axes, indicating different degrees of compromise among the objectives. Scheme Sch2 attains the highest closeness coefficient while maintaining fairly balanced, medium-high levels of sufficiency, reliability and spill control and can be regarded as the best overall compromise. Scheme Sch114 performs slightly better in sufficiency and spill control, whereas Sch116 shows a slight advantage in reliability; their polylines are, therefore, slightly shifted towards the water-saving and reliability directions, respectively, relative to Sch2. Overall, the radar plot clearly distinguishes three typical classes of operating philosophy—water-saving oriented (Sch1), reliability-oriented (Sch6) and multi-objective compromise (Sch2, Sch114, Sch116)—and offers a visual basis for selecting suitable operation schemes in line with specific management priorities.

4.3.3. Interpretation and Operational Implications of Representative Schemes

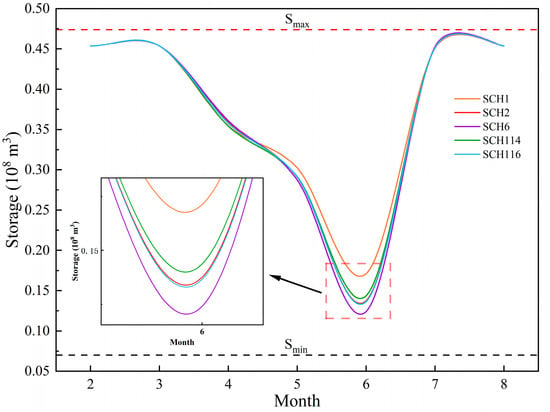

All representative schemes (Sch1, Sch2, Sch6, Sch114 and Sch116) exhibit a consistent seasonal storage pattern, with gradual drawdown in the early months, a minimum around the peak irrigation period and rapid refill thereafter toward the upper operating range. This indicates that, under the given irrigation-demand conditions, the overall seasonal timing of release and refill is broadly similar among the schemes. The most pronounced differences occur in the vicinity of the minimum storage. The inset in Figure 9 magnifies the period around May–June, when storage approaches its annual minimum, in order to highlight the separation among the five trajectories. During this stage, Sch1 and Sch114 maintain comparatively high storage levels, Sch2 occupies an intermediate position, whereas Sch6 and Sch116 reduce storage to levels much closer to . Schemes Sch1 and Sch114, therefore, embody a conservative storage policy: a larger storage buffer is retained during the peak irrigation season, which enhances protection against subsequent dry inflows or forecast errors but relaxes the control of spill and storage deviations to some extent. In contrast, Sch6 and Sch116 implement an aggressive release policy, making intensive use of stored water during the critical irrigation months to increase water-supply assurance; as a result, storage remains near the lower bound for part of the season, and the safety margin is reduced. The trajectory of Sch2 lies between these two behaviors: its minimum storage is clearly lower than that of Sch1 and Sch114 yet does not approach as closely as Sch6 and Sch116, which is consistent with its identification as a compromise scheme in the multi-indicator evaluation.

Figure 9.

Monthly reservoir storage trajectories of five representative schemes.

From an operational standpoint, the comparison of storage trajectories provides a clear interpretation of how different decision preferences are translated into reservoir behavior. In years with relatively scarce inflows or stringent irrigation-assurance requirements, operating paths similar to those of Sch6 and Sch116 may be selected to strengthen irrigation supply at an acceptable level of storage risk. When storage safety, subsequent regulation capacity or inflow uncertainty is of primary concern, conservative paths exemplified by Sch1 and Sch114 offer a safer alternative. Under normal hydrological conditions or when a balanced consideration of supply reliability, spill control and storage safety is required, the compromise trajectory represented by Sch2 constitutes a more balanced option among the competing objectives.

It should be noted that the present analysis is based on a single representative year (2024). This year was selected because complete and up-to-date records are available and its hydrological and irrigation conditions are broadly consistent with the recent multi-year average. Nevertheless, using a single year as input inevitably limits the representation of inter-annual variability and may cause the optimized schemes to be partially tuned to the specific conditions of 2024. Future work will extend the framework to multi-year or stochastic inflow scenarios and to multiple irrigation-demand scenarios in order to assess the robustness of the proposed operating schemes under a wider range of hydrological and management conditions.

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

This study develops a joint-operation optimization-ranking workflow for the Jingou River-Hongshan Reservoir system based on a deterministic, single-year (2024) monthly setting. Therefore, the results primarily reflect the hydrological and demand conditions represented by the 2024 gate-operation records organized at a monthly time step, which may not fully capture inter-annual variability or potential regime shifts in inflows and water demands.

Uncertainties in inflows, irrigation demands and ecological-flow assumptions were not explicitly propagated in the current framework. In addition, downstream ecological requirements were specified from regional plans and previous assessments and implemented as prescribed monthly minimum-release constraints, which improves operational enforceability but may not represent the full range of ecological-response uncertainty. Future work will extend the analysis to multi-year datasets and scenario-based or stochastic formulations to evaluate the robustness of Pareto fronts and selected representative schemes under a broader range of hydrological and management conditions.

The final scheme selection relies on entropy-based weighting and TOPSIS ranking. While entropy weights offer an objective, data-driven baseline and the ranking robustness has been examined under alternative weighting scenarios, the resulting preferences may still differ from stakeholder- or policy-driven priorities in practice. Further work can incorporate participatory preference elicitation and expand the indicator set to better reflect additional management concerns. Finally, although the proposed workflow is intended to be applicable to other reservoir-supported irrigation systems in arid regions, additional applications to other basins and multi-reservoir settings are needed to assess its generality and practical adaptability.

5. Conclusions

The coordinated operation of reservoir-irrigation systems in arid inland river basins is essential for improving water-supply efficiency, maintaining ecological baseflow and supporting sustainable water-resources management. Focusing on the Jingou River-Hongshan Reservoir system in Xinjiang, this study developed a multi-objective joint-operation framework that couples an NSGA-II-based optimization model with entropy-weighted TOPSIS evaluation to address trade-offs among irrigation demand, reservoir storage safety and ecological flow requirements. The main conclusions are as follows:

- The proposed framework links multi-objective optimization results with practical decision-making. NSGA-II is used to generate a Pareto set of non-dominated joint-operation schemes, and entropy-weighted TOPSIS ranks these schemes and extracts a limited number of representative options. This two-step procedure enables decision-makers to move from an abstract Pareto front to a concise set of interpretable operating schemes for reservoir-irrigation scheduling in arid inland river basins.

- Entropy-weighted TOPSIS analysis shows that irrigation shortage and spill-storage performance are the main factors distinguishing alternative schemes, while reliability varies only weakly within the Pareto front. High-ranking schemes, therefore, exhibit relatively low irrigation shortages and small spill-storage deviations, with only modest differences in overall reliability. For the preferred compromise scheme, the annual irrigation water-shortage ratio is about 39% of the total annual demand, the mean satisfaction level of irrigation and ecological requirements is about 57%, and the composite spill-storage index remains at a comparatively low level, indicating a reasonably balanced trade-off among shortage control, supply stability and reservoir-operation efficiency.

- The joint-operation results reveal distinct operational philosophies among representative schemes, including water-saving, reliability-oriented and compromise strategies. Water-saving schemes strengthen storage control but may increase the risk of spill losses or underutilization, whereas reliability-oriented schemes stabilize water supply at the expense of larger spill and storage deviations. The compromise scheme moderates extremes in all three objectives, highlighting the inherent competition between irrigation supply, ecological baseflow maintenance and storage security and providing targeted scheduling pathways for different management priorities.

The present study considers a one-year operating horizon under representative hydrological conditions and deterministic inputs, which limits the assessment of long-term robustness. Future work will extend the framework to multi-year and stochastic hydrological scenarios and incorporate refined ecological-response indicators to better link ecological flow regimes with ecosystem outcomes, thereby enhancing the applicability of multi-objective reservoir-irrigation operation in arid inland river basins.

Author Contributions

Software, K.Z.; Validation, N.L. and Y.D.; Data curation, Z.W. and K.Z.; Writing—original draft, K.Z. and M.D.; Writing—review and editing, Z.W. and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Talent Development Fund through the Scientific Research and Innovation Platform Project “Innovation Center for Key Equipment Technologies for Efficient Water and Fertilizer Use in Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps Agriculture”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support from Xinjiang Jingou River Basin Water Conservancy Management Center.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Mingjiang Deng was employed by the company Xinjiang Shuifa Water Group Company Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhao, X.F.; Zhu, A.L.; Liu, X.H.; Li, H.Y.; Tao, H.Y.; Guo, X.X.; Liu, J.F. Current status, challenges, and opportunities for sustainable crop production in Xinjiang. iScience 2025, 28, 112114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.S.; Hao, T.P.; Zhou, H.P.; Li, Q.J.; Zhang, A.M.; Zhang, N.; Ma, Z.B.; Guo, W.T. Analysis on ecological water demand of natural oasis in arid area of Xinjiang. J. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 12, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.Q.; Wang, J.Z.; Cheng, Y.; Ye, Z.X.; Zhu, C.G.; Zhou, H.H. Water resources management of Kaidu River using ecological baseflow analysis. J. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 8, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reheman, A.; Wu, Z.H.; Liu, D.D. Multi-objective optimal scheduling of water supply–ecology for Sidaogou Reservoir in Hami City. J. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 11, 335–345. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.L.; Zhou, J.Z.; Wang, H.L.; Zhang, Y.C. Multi-objective ecological optimal scheduling model of Three Gorges cascade hydro-junction and its solving method. Adv. Water Sci. 2011, 22, 780–788. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, N.; Peng, Y.X.; Lu, K.M.; Zhou, G.X.; Guo, X.T.; Niu, M.H. Multi-objective optimal operation decision for parallel reservoirs based on NSGA-II-TOPSIS-GCA algorithm: Case study in Upper Hanjiang River. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.Y.; Zeng, X.C.; Liu, X.D.; Jin, W.Q. Research on the evaluation of water resources carrying capacity in five northwest provinces based on entropy TOPSIS model. China Rural. Water Hydropower 2022, 12, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, X.S.; Yu, Y.X.; Liang, Z.M.; Shi, X.Y.; Cao, R.; Zhang, X.K. Multilayer entropy-weighted TOPSIS method and its decision-making in ecological operation during the subsidence period of the Three Gorges Reservoir. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.; Castelletti, A.; Pianosi, F.; Mason, E.; Reed, P.M. Curses, Tradeoffs, and Scalable Management: Advancing Evolutionary Multiobjective Direct Policy Search to Improve Water Reservoir Operations. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2016, 142, 04015050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.C.; Chang, F.J. Multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for operating parallel reservoir system. J. Hydrol. 2009, 377, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, W.W.-G. Reservoir management and operations models: A state-of-the-art review. Water Resour. Res. 1985, 21, 1797–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurbs, R.A. Reservoir-system simulation and optimization models. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 1993, 119, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.; Lamontagne, J.R.; Reed, P.M.; Castelletti, A. A state-of-the-art review of optimal reservoir control for managing conflicting demands in a changing world. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2021WR029927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, W.W.-G.; Becker, L. Multiobjective analysis of multireservoir operations. Water Resour. Res. 1982, 18, 1326–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.Q.; Wang, P.F.; Guo, H.; Yang, H. Application of intelligent optimization algorithm in optimal operation of reservoir. J. Hydroelectr. Eng. 2020, 39, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ning, X.; Gao, H. Multi-objective optimization of conjunctive use of surface water and groundwater. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 2021, 32, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Azari, A.; Hamzeh, S.; Naderi, S. Multi-Objective Optimization of the Reservoir System Operation by Using the Hedging Policy. J. Water Resour. Manag. 2018, 32, 2061–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.L.; Yuan, R.Z.; Wang, Y.W.; Liu, S.Z.; Yang, Y.L. Application of NSGA-II genetic algorithm in optimizing operation of cascaded reservoirs. Yellow River 2018, 40, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.F.; Xie, J.C.; Li, X.L.; Huang, J.Q.; Zhu, T. Multi-objective optimization of reservoir flood control operation considering uncertainty. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2015, 141, 05014021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Lei, Z.; Wang, C.L.; Wei, J. Water–energy–environment nexus optimization for multi-reservoir operation under climate change. Water Resour. Manag. 2017, 31, 1207–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhong, P.A.; Liu, W.; Wan, X.Y.; Yeh, W.G. Multi-objective risk management model for real-time flood control optimal operation of a parallel reservoir system. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Shen, C.P.; Liu, X. Bi-objective optimization of reservoir operation considering downstream ecology. Water Sci. Eng. 2019, 12, 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, N.; Fang, Y.; He, M.W.; Ding, Y.F. Multi-objective optimization of a hydropower cascade considering ecosystem. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2017, 17, 1239–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Guo, S.; Xiong, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, T. Multi-objective ecological reservoir operation based on water-quality response models and improved genetic algorithm: A case study in Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2014, 36, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Xu, C.Y.; Singh, V.P. Intelligent algorithm for multi-objective reservoir operation—A review. Adv. Water Sci. 2012, 23, 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Mei, Y.D.; Cai, H. Study on optimal operation of reservoirs in Ganjiang River basin for power generation, water supply and ecological requirements. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2018, 49, 628–638. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.L.; Peng, Y.X.; Han, D.C. Coupling MOEA and grey correlation for reservoir multi-objective decision-making. Water Sci. Eng. 2020, 13, 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli, R.; McDonald, C.; Reed, P.; Gerlowski, N. Many-objective reservoir operation with uncertain climate inputs. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018035. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.C.; Wu, M.Y.; Liu, X.D.; Zhou, Y.Y. Water resources management in arid regions: Challenges and technologies. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7, 129. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Shen, J.B.; Li, C.W.; Hu, H.C. Water–food–ecosystem linkage in arid zone oasis under irrigation development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.L.; Li, C.S.; Liu, F.Y. Multi-objective scheduling of cascade reservoirs in the upper Yellow River based on NSGA-III. Yellow River 2022, 44, 140–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Z.; Wang, Y.T.; Chen, Y.W. Multi-objective reservoir regulation model based on simulation rules and intelligent optimization and its application. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2015, 43, 564–570. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadalipour, A.; Shafiei, M.; Moradkhani, H. Reservoir operation optimization under climate change using a multi-objective framework. J. Hydrol. 2018, 556, 634–648. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, D.L.; Zhou, Q.L. Impact of ecological flow releases on downstream water quality and ecosystem: A case study. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 114021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.J.; He, P.Y.; Liu, C.Z. Evaluation of river ecological health via mathematical models. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 69, 804–810. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.L.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.R.; Yu, D.Y. Ecological flow requirement analysis in arid inland rivers: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 687, 550–565. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Shao, Q.Q.; Su, S.L.; Zhou, X.W. Ecological flow regimes of inland rivers under climate change. J. Hydrol. 2020, 587, 124843. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.F.; Wen, W.; Wang, Z.F.; Yang, Y.Q. Water conflict management in arid regions: Case study of Xinjiang. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 360, 132025. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Song, X.L.; Wang, H.X.; Su, L.Y. Multi-criteria decision analysis in water resource systems: Methodologies and applications. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 34, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A Fast and Elitist Multiobjective Genetic Algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Agrawal, R.B. Simulated Binary Crossover for Continuous Search Space. Complex Syst. 1995, 9, 115–148. Available online: https://www.complex-systems.com/abstracts/v09_i02_a02/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Sandoval, A.; Requelme, N.; Cachipuendo, C.J. Multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) methodology for the prioritization of technical irrigation projects. Water Policy 2025, 27, 804–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbolt, S.C.; Perera, B.J.C. Multicriteria analysis to select an optimal operating option for a water grid. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2017, 143, 05017005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.