Abstract

This study compares the performance of empirical and hybrid deep learning (DL) models in estimating daily potential evapotranspiration (PET) in the Nakdong River Basin (NRB), South Korea, with the FAO-56 Penman–Monteith (PM) method as a reference. Two empirical models, Priestley–Taylor (P-T) and Hargreaves–Samani (H-S), and two DL models, a standalone Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network and a hybrid Convolutional Neural Network Bidirectional LSTM with an attention mechanism, were trained on a meteorological dataset (1973–2024) across 13 meteorological stations. Four input combinations (C1, C2, C3, and C4) were tested to assess the model’s robustness under varying data availability conditions. The results indicate that empirical models performed poorly, with a basin-wide RMSE of 5.04–5.79 mm/day and negative NSE (−10.37 to −13.99), and are therefore poorly suited to NRB. In contrast, DL models achieved significant improvements in accuracy. The hybrid CNN-BiLSTM Attention Mechanism (C1) produced the highest performance, with R2 = 0.820, RMSE = 0.672 mm/day, NSE = 0.820, and KGE = 0.880, which was better than the standalone LSTM (R2 = 0.756; RMSE = 0.782 mm/day). The generalization of heterogeneous climates was also verified through spatial analysis, in which the NSE at the station level consistently exceeded 0.70. The hybrid DL model was found to be highly accurate in representing the temporal variability and seasonal patterns of PET and is therefore more suitable for operational hydrological modeling and water-resource planning in the NRB.

1. Introduction

Accurate estimation of potential evapotranspiration (PET) is critical for understanding the hydrological and climatic mechanisms that control water resources, agricultural activities, and the sustainability of ecosystems [1,2]. PET is the best estimate of evapotranspiration and moisture content and is a key element in hydrological models, irrigation design, and drought measurements [3,4]. Several empirical and physically based models have been developed to estimate PET, including the Penman–Monteith (FAO-56 PM), Priestley–Taylor (P-T), and Hargreaves–Samani (H-S) models [5,6,7,8]. The most suitable is the FAO-56 PM equation, which is based on a reasonable physical basis. Nonetheless, it also requires several meteorological parameters, which may not always be available in data-scarce areas [9]. As a result, there has been an increase in the search for precise, effective, and data-adaptable approaches to PET estimation, especially as climatic conditions and data constraints continue to change. Therefore, in this study, PET estimation methods are categorized into traditional empirical approaches and advanced Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) models.

1.1. Traditional Empirical Approaches

Traditional empirical approaches, despite their simplicity, are often limited by assumptions and a lack of input variables [10]. These models were grouped into three categories: temperature-based, radiation-based, and comprehensive formulations [4]. The principal temperature-dependent models are the HS model, which relies on the maximum and minimum air temperature [11]. On the other hand, solar radiation and net radiation can also be incorporated into radiation-based models, such as the P-T or Makkink equations [7,12]. Nevertheless, empirical approaches are less effective in regions with high spatial and climatic heterogeneity and provide biased estimates when used outside the calibration areas [13]. It is possible that the complexity of the hydrological processes involved in the non-linear interactions among climatic factors, e.g., in the Nakdong River Basin (NRB) of South Korea, with its vast topography and considerable seasonal variation, could not be empirically well modeled [14,15].

1.2. Advancements in Machine Learning and Deep Learning

To address these limitations, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) methods have been proposed as alternatives to PET estimation [5,16,17]. In modeling complex, non-linear, and multivariate climatic processes, algorithms such as support vector machines (SVMs), random forests (RFs), and extreme learning machines (ELMs) have demonstrated strong predictive performance [6,18,19]. In contrast to empirical models, ML methods do not require explicit physical equations to learn; instead, they learn from data trends, which is more flexible in the presence of incomplete data [20,21]. A review of the literature on different climatic conditions has shown that ML algorithms are highly efficient at simulating the FAO-56 PM PET with fewer meteorological inputs [4,9]. Indicatively, Shaloo et al. (2024) applied four ML algorithms, including linear regression, SVMs, RFs, and artificial neural networks (ANNs), using small input datasets in the semiarid region of India. They determined that SVM was the most precise (R2 = 0.985) with few predictors (temperature, relative humidity (RH), and sunshine hours (N) [9]. Similarly, Liu et al. (2022) demonstrated that RF is more effective than empirical models in the Yellow River Basin, where temperature and N are the most critical predictors [4].

In addition to classical ML algorithms, the recent developments in hybrid DL models have changed the estimation of PETs, as they can now account for temporal dependence and spatial variation [22]. Hydrometeorological forecasting is increasingly being performed with deep neural networks (DNNs), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, temporal convolutional networks (TCNs), and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [6,22]. Chen et al. (2020) demonstrated that the accuracy of both TCN and LSTM models was significantly higher than that of empirical and classical ML models in the Northeast Plain of China with missing data [6]. Improved the PET prediction performance by combining empirical mode decomposition (EMD) and wavelet denoising with CNNs and LSTMs in Li et al. (2024) and obtained R2 greater than 0.95 in various stations in Northeast China [22]. The same studies also highlight that hybrid DL models have the advantage of extracting complex multiscale patterns using climate data, which cannot be done with either single ML or empirical models.

Although DL models have demonstrated high accuracy and generalization, their black-box nature and computational complexity are drawbacks for interpretability and real-time use [23,24,25]. The interpretability and transferability are essential in the interpretation of the effect of climate drivers, including maximum and minimum temperature (Tmax) and (Tmin), RH, and net radiation (Rn), on processes related to PET. Consequently, hybrid modeling schemes that combine different DL models with the adaptive learning capabilities of DNNs have been proposed by many researchers [5,22]. These hybrid DL models blend the benefits of empirical formulations and DL systems, enhancing accuracy while providing some physical interpretation. For example, Pino-Vargas et al. (2022) compared direct and indirect hybrid approaches between empirical equations (PM, H-S, and Ritchie) and multilayer perceptron (MLP) networks in the Atacama Desert, in which the indirect hybrid models were found to be better in long-term PET prediction (MAE = 0.033 mm/day) [5].

Table 1 and Table 2 summarize recent research on PET estimation using empirical and ML/DL methods across different regions. These studies have shown that ML/DL models are superior to traditional empirical methods. Later works presented ML methods, such as RF, SVR, and tree ensembles, and demonstrated their resilience across various input settings. The accuracy of DL models, such as CNNs, RNNs, and LSTMs, increased due to their ability to capture both temporal and sequential features. Most recent studies have focused on hybrid and lightweight models, including ELMs and boosting methods, that emphasize input quality, interpretability, and transferability.

1.3. Research Gaps and Objectives

However, numerous gaps remain in PET estimation, despite these DL models making significant progress. Most studies focus on arid or semiarid regions, such as the Yellow River Basin [4], Northeast China [6,22], or semiarid areas of India [26]. Nevertheless, little work has been performed on humid or monsoon-dominated basins, including those found in South Korea [15]. In addition, no region-specific analyses exist that quantify the performance tradeoffs of empirical and hybrid DL models in cases where meteorological data are sparse.

In South Korea, the meteorological networks are dense but suffer from data gaps. In addition, the studies of the NRB have primarily focused on water quality [27,28,29,30], sediment transportation [31,32], and hydrological extremes [33,34], with limited consideration for the dynamics of evapotranspiration [35,36], despite the use of advanced hybrid DL models. As variations in temperature and precipitation patterns drive climate change, the demand for accurate PET estimates is increasing in the basin to sustain water resources, optimize irrigation timing, and assess the effects of climate change. An integrated approach combining empirical models (e.g., FAO-56 PM) with hybrid DL models is essential to enhance PET estimation accuracy across diverse conditions. Such hybridization combines physical interpretability with non-linear learning, yielding more robust and transferable PET predictions.

Therefore, this study has two main objectives: (1) to develop hybrid DL models for estimating daily PET in the NRB and compare their prediction accuracy with empirical methods, and (2) to analyze the spatial and temporal variability of PET across the basin using the most effective modeling approaches. Through these goals, the study aims to contribute to the expanding literature on the hybrid modeling of hydrological processes and to aid in the development of more effective water management practices in data-variable settings.

Table 1.

Summary of empirical and ML approaches in previous PET research.

Table 1.

Summary of empirical and ML approaches in previous PET research.

| Study | Study Area/Dataset | Methods (Empirical/ML) | Inputs | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [37] | Northwest China | ANN vs. MLR & empirical formulas | Tmax, Tmin, RH, U2, N | ANN outperformed MLR and empirical methods; Tmax, Tmin, and RH were the most important |

| [38] | Central Florida | M5P, Bagging, RF, SVR | Radiation, heat flux, soil moisture, wind, RH, T | Strong performance; input quality strongly influenced accuracy |

| [39] | India | ANN vs. empirical equations | Temperature, RH, radiation, wind | ANNs often outperform empirical equations |

| [40] | India | RBF neural networks | Limited climatic data | RBF is effective under sparse data |

| [41] | Iraq | ELM vs. standalone ML | Temperature-based & multivariable inputs | ELM competitive; lightweight ML effective |

| [42] | Sichuan Basin, China | ELM, GRNN, RF + empirical | Temp-only & multivariable | Intelligent temp-only models are competitive; RF robust |

| [43,44] | China | SVM, ELM, LightGBM, CatBoost | Limited meteorological datasets | Tree boosting is competitive; it emphasizes transferability |

| [45,46] | Iran, Brazil, global | GRNN, MARS, GEP, ANFIS | Temp-only & multivariate | No single best algorithm; performance data-dependent |

| [47,48] | Semiarid sites | Sequential RBF + empirical hourly formulas | Hourly meteorology | Highlighted the value of hourly modeling |

Table 2.

Summary of DL and hybrid modeling approaches in previous PET studies.

Table 2.

Summary of DL and hybrid modeling approaches in previous PET studies.

| Study | Study Area/Dataset | Methods (DL/Hybrid) | Inputs | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | Minas Gerais, Brazil | ANN, RF, XGBoost, 1-D CNN (DL) | Daily/hourly Temperature, RH, Ra | Hourly CNN improved RMSE by ~28%; sequence-aware DL advantageous |

| [49] | Prince Edward Island, Canada | LSTM, bi-LSTM | Tmax, RH | High R2 (>0.90); DL effective with few inputs |

| [50] | India | ANN interpretability (DL-related review) | Multiple parameters | Explained the physical interpretability of ANN hydrological models |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

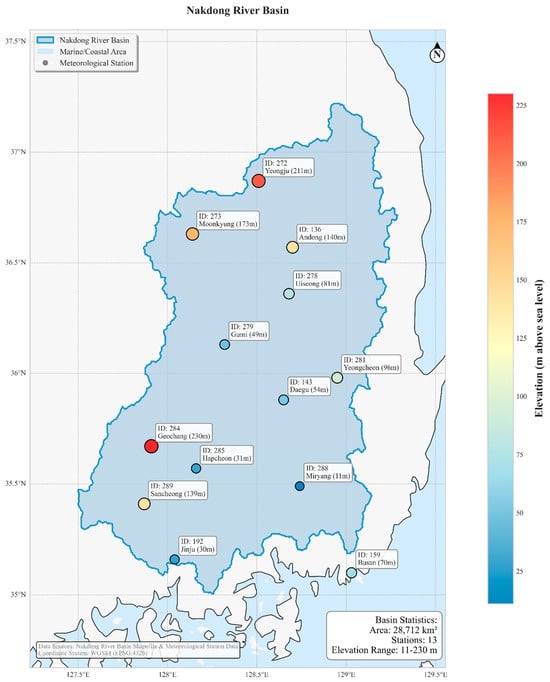

The NRB is the 2nd-largest South Korean river watershed (Figure 1), with an area of approximately 23,600 km2 and a length of about 510 km from its source in Taebaek, Gangwon Province, to its mouth at Busan [28]. It has 33 mid-level basins and 266 unit basins [27], as well as major tributaries, including the Geumho, Nam, Milyang, and Naeseong rivers [29]. It has a warm, humid summer and a dry winter climate, with an average annual precipitation of approximately 1200 mm, of which 60% falls during the monsoon season between June and September [29]. The basin’s land cover is primarily forests (68%), followed by agricultural lands, including paddy and upland fields [28]. There are many multipurpose dams and weirs in the river system that regulate streamflow dynamics and water quality [28]. The NRB faces ongoing issues of water quality, nonpoint source pollution, and eutrophication, primarily due to rapid industrialization and urbanization [27,30]. For these reasons, the basin is a point of concern for hydrological modeling and estimating evapotranspiration under changing climatic conditions.

Figure 1.

Distribution of weather stations in NRB.

2.2. Data Acquisition and Quality Checking

Table 3 presents the distributions and descriptive statistics of meteorological variables measured at 13 weather stations in the NRB for the period from 1973 to 2024. Data were sourced from the Korean Meteorological Administration and are freely accessible. The stations are located at various heights, which represent different topographical effects on the local climate. The spatial variation in average Tmax is modest, ranging from 5.19 °C at Uiseong to 11.52 °C at Busan. Conversely, the mean Tmin is relatively moderate, ranging from 8.75 °C to 11.21 °C. RH exhibits a wide range of variability, with mean values of 41–59% and a coefficient of variation (CV) exceeding 50, indicating significant microclimatic changes. The mean wind speed (uz) is not large (61.79–70.04 m/s) but with a high CV, indicating that there is a tendency for seasonal variations in the distribution of wind. The mean sunshine is 6.20–6.73 h/day, with moderate CV (~55–61 %) due to a combination of seasonal and local cloud cover. In general, these descriptive statistics suggest that the climatic conditions in the NRB are highly heterogeneous, primarily due to variations in latitude, elevation, and proximity to coastal areas.

Table 3.

Weather stations and their descriptive statistics.

2.3. Empirical Methods

This study considered three empirical methods for the estimation of daily PET based on their significance in the literature: (1) FAO-56 PM, (2) P-T, and (3) H-S methods.

2.3.1. Penman–Monteith (FAO-56 PM) Equation

Daily PET was estimated using the FAO-56 PM equation [3], which combines energy balance and aerodynamic principles to provide a standardized, physically based estimate of reference evapotranspiration (ET0). The method accounts for the effects of net radiation (), air temperature Tmax and Tmin, RH, and uz on evapotranspiration processes.

The FAO-56 PM equation is expressed as:

where

is the reference evapotranspiration (mm day−1), is the slope of the saturation vapor pressure curve (kPa °C−1), is the net radiation at the crop surface (MJ m−2 day−1), and is the soil heat flux (MJ m−2 day−1). γ is the psychrometric constant (kPa °C−1), T is the mean daily air temperature (°C), is the wind speed at 2 m height (m s−1), is the saturation vapor pressure (kPa), and is the actual vapor pressure (kPa).

The Tmean was calculated as the arithmetic average of the maximum Tmax and Tmin air temperatures:

was derived as:

where P is the mean atmospheric pressure (kPa) at the station elevation, estimated using the standard atmospheric pressure–altitude relationship [3]:

where z is the station elevation above mean sea level (m).

Δ was computed as [3]:

eₛ was estimated as the mean of the saturation vapor pressures at Tmax and Tmin:

where the saturation vapor pressure at a given temperature is calculated using the Tetens formula:

eₐ was derived from RH as:

Measured at height h (m) was adjusted to the standard 2 m height () using a logarithmic wind profile:

Rₐ was estimated as [51]:

where is the solar constant (0.0820 MJ m−2 min−1),

is the inverse relative Earth–Sun distance,

is the solar declination (radians),

is the sunset hour angle (radians),

ϕ is the latitude (radians), and J is the Julian day.

The Nmax was obtained as:

Rₛ was computed using the Ångström–Prescott relationship [52]:

where N is the actual sunshine duration (hours), and empirical coefficients were used as recommended by FAO [3].

Then was calculated as:

where α = 0.23 is the albedo for a grass reference surface.

and were computed, respectively, as:

are air temperatures in Kelvin (K = °C + 273.16).

The net radiation (Rₙ) at the crop surface was thus determined as:

Daily ET0 values were aggregated to monthly and annual means to assess temporal variations. Yearly mean and maximum PET were computed using grouped statistical aggregation:

where represents the number of daily observations per year.

2.3.2. Priestley–Taylor (P-T) Method

A simplification of the PM method is the P-T method [7], which was derived to estimate PET when data on surface aerodynamic resistance and vapor pressure deficit are unavailable. The approach assumes a surface in a well-watered state and under equilibrium conditions, and represents evapotranspiration as a ratio of available energy to the slope of the saturation vapor pressure curve.

The P–T equation is given by:

where α = Priestley–Taylor empirical coefficient (dimensionless), typically 1.26 for humid and well-watered conditions.

The P-T equation assumes that the aerodynamic term in the PM formulation is replaced by the empirical factor α, which modulates evapotranspiration in response to atmospheric demand and surface moisture. In arid or semiarid environments, the possible range of 1.0 to 1.3 is employed, whereas in water-limited environments, the range of 0.8 to 1.0 is used [53]. All terms except α were calculated in the same way as in Section 2.3.1 (PM method), so that there is consistency in the parameterization of radiation and temperature.

2.3.3. Hargreaves–Samani (H-S) Equation

The H-S equation is an empirically estimated method for calculating that requires temperature and extraterrestrial radiation measurements [11]. It is applicable in data-scarce areas where RH, radiation, or uz measurements are unavailable. The H-S equation is given as:

0.0023 is a calibration coefficient that ensures proper unit conversion between water depth and radiation. The is used to describe the range of diurnal temperature variation, which serves as an indicator of atmospheric transmissivity [54]. The H-S method is ideal in areas with limited meteorological information; however, when used in humid climates or areas with strong advection, it requires calibration [55].

2.4. DL Methods

Two DL models were developed in this research: a standalone LSTM and a hybrid CNN–Bidirectional LSTM with an attention mechanism. These models were selected for their success in capturing time-dependent features in time-series data and their ability to handle the multivariate meteorological characteristics essential for day-to-day PET forecasting. Although DL offers a wide range of models, the literature indicates that LSTM-based models outperform ML/DL models at capturing long-term dependencies and non-linear interactions in PET data. Thus, we focused on LSTM and hybrid models to balance model complexity, interpretability, and predictive performance.

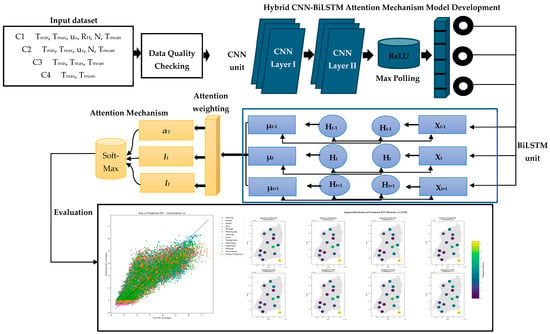

Hybrid CNN–Bidirectional LSTM Model with Attention Mechanism

This model uses a hybrid DL architecture that combines CNNs with bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) and a self-attention mechanism to forecast daily PET based on meteorological data (Figure 2). The CNN-BiLSTM architectures are not new; however, the peculiarities of this study include the introduction of a self-attention mechanism for PET prediction, the consideration of specific feature engineering (derived meteorological features and cyclical encoding of day-of-year and month), and the customization of hyperparameter optimization for PET prediction. This combination increases interpretability, highlights important temporal patterns, and improves predictive accuracy compared to current implementations.

Figure 2.

Working flow diagram of Hybrid CNN-BiLSTM Attention Mechanism.

The meteorological variables, such as daily minimum and maximum temperatures, Tmax, Tmin, RH, wind speed (uz), and solar radiation, were utilized. Additional derived features included Tmean, temperature range = Trange = Tmax − Tmin, and vapor pressure deficit (VPD), which is calculated as:

where

To account for seasonal and cyclical patterns, day-of-year and month features were encoded using sinusoidal transformations:

The rolling statistics (mean and standard deviation) and lag features (e.g., 1-day, 2-day, 3-day, and 7-day lag) were added to incorporate the temporal dependencies. Other features, such as Tmax, Tmin, RH, wind, and solar radiation, were also added to represent non-linear dependencies critical to PET. The RobustScaler was used to normalize all features, and the MinMaxScaler was used to scale the target PET values to the range 0–1. The length of the sequences L = 60 days was built at each station, and tensors were formed (N, L, F), where N is the count of sequences, and F is the count of features.

The architecture has three main modules:

The CNN branch obtains local time series of multivariate meteorological series. There were two convolutional layers with kernel sizes 3 and 5, followed by batch normalization, ReLU activation, and max pooling.

If we let denote the sequence of inputs, the convolutional operation can be defined as:

where X, and denotes batch normalization. Max pooling reduces sequence length to highlight dominant patterns.

The BiLSTM captures long-term temporal dependencies in PET dynamics. For each time step t:

The bidirectional structure enables the model to consider both past and future information within the sequence.

The attention mechanism assigns weights to each LSTM hidden state based on its relevance for PET prediction:

where is the dimension of the hidden state [56]. The output is then aggregated using global average pooling to obtain a fixed-length representation for the fully connected regression layers.

The final module consists of three dense layers with ReLU activations and dropout, producing the estimated PET value:

The Huber loss () was employed for robust regression. The optimal model hyperparameters selected after grid search are presented in Table 4. The model was trained with the AdamW optimizer and weight decay to reduce overfitting. A ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler adjusted the learning rate based on validation loss, and early stopping with a patience of 20 epochs prevented unnecessary training. Gradient clipping stabilized learning for deep sequences.

Table 4.

Summary of the optimal hyperparameters obtained via grid search for training the hybrid model.

The model was built in PyTorch [57] and executed in a GPU-enabled environment. Sequences were split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test sets (15%) with non-overlapping time intervals to preserve temporal integrity. Feature imputation and scaling ensured consistent numerical ranges across all datasets. The detailed evaluation criteria are provided in the Supplementary File (Section S1).

The results of the hybrid CNN-BiLSTM with attention were compared with those of a standalone LSTM model after training to understand the value added by the CNN and attention modules. This comparison shows the consistent improvements achieved through hybridization and feature-attention-based weighting.

3. Results

The PET calculated using the recommended FAO-56 PM method serves as a reference for evaluating the performance and stability of the DL model during training and testing. Different input combinations (C1, C2, C3, and C4) were generated in regions with data scarcity to assess the proposed DL model’s performance. To develop different input combinations, a detailed correlation analysis was performed between the PET estimated by the FAO 56 PM method and the variables (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation analysis between meteorological variables and PET estimated by the FAO-56 PM-Method.

Tmin and Tmax showed strong positive relationships with Tmean (r = 0.98) and PET (r = 0.70 and 0.82, respectively), indicating that temperature parameters are the major contributors to PET variability. The correlation between the uz and PET (r = 0.08) indicated a comparatively insignificant impact on the NRB climate conditions. RH showed negative correlations with uz (r = −0.47) and sunshine duration (r = −0.62), indicating a negative relationship between atmospheric moisture and evaporation. The moderate positive relationship between N and PET (r = 0.49) underscores the importance of solar radiation in increasing evapotranspiration.

Based on these relationships, four input combinations (Table 6) were developed to create a hybrid and a standalone DL model to maximize prediction effectiveness. Combination C1 was the complete combination of all the meteorological variables of interest, whereas C2–C4 successively removed some redundancy by dropping the least correlated or collinear predictors. Namely, C3 and C4 focused on temperature-related inputs, including the most influential variables (Tmax and Tmean), to simplify and strengthen the PET estimation models. It is a step-by-step method that guarantees a tradeoff between predictive accuracy and model complexity.

Table 6.

Input combinations based on correlation analysis for the development of DL models.

3.1. Comparative Evaluation of DL Models

The comprehensive assessment of the hybrid CNN-BiLSTM attention mechanism and standalone LSTM models for NRB daily PET estimation reveals significant differences in predictive accuracy, which are influenced by input combinations. Table 7 presents the analysis statistics, including R2, RMSE, MAE, NSE, and KGE, for C1–C4.

Table 7.

Overall performance of different input combinations during PET estimations at NRB using a hybrid and a standalone LSTM model.

In the hybrid model, C1 (Tmin, Tmax, uz, RH, N, Tmean) shows better performance, with R2 (0.820), RMSE (0.672), and MAE (0.481), as well as optimal NSE (0.820) and KGE (0.880). This suggests that the presence of both extremes of the temperature, uz, RH, N, and Tmean captures the intricate non-linear relationships that affect PET better than smaller sets of variables. C2 and C3, which gradually eliminate RH, uz, and N, have a slightly lower predictive power, indicating that although temperature and Tmean are the main models, secondary variables enhance the model’s predictive capacity. C4, which utilizes Tmax and Tmean, is the worst-performing among all hybrid model configurations, suggesting that other meteorological inputs are essential for estimating daily PET.

The same trend is also evident in the standalone LSTM model. Still, its overall performance is worse than that of the hybrid model, demonstrating the advantage of adding CNN layers and attention mechanisms to learn spatiotemporal relations and feature importance. It is also worth noting that in the LSTM model, C2 outperforms C1 (R2 = 0.779 vs. 0.756), indicating that input variable redundancy does not necessarily lead to simpler model designs.

Furthermore, the attention mechanism indicates that net radiation, VPD, and Tmax are the most influential drivers of PET, highlighting the dominant role of atmospheric energy and evaporative demand (Figure S4). Temporal variables and interaction terms contribute less, suggesting secondary modulation rather than primary control of PET variability.

The C1 input combination of the CNN-LSTM model is the most suitable for estimating operational daily PET in the NRB, as it is more accurate and robust. The complete range of meteorological variables in the model allows it to better represent the non-linear, multivariable dynamics of PET than reduced input sets or the standalone LSTM model.

Comparison of the station-based performance of the two DL models in forecasting daily PET in the NRB reveals spatial differences in predictive accuracy. This emphasizes the importance of carefully selecting inputs for effective modeling. RMSE, MAE, R2, NSE, PBIAS, and RSR are discussed in Tables S1 and S2.

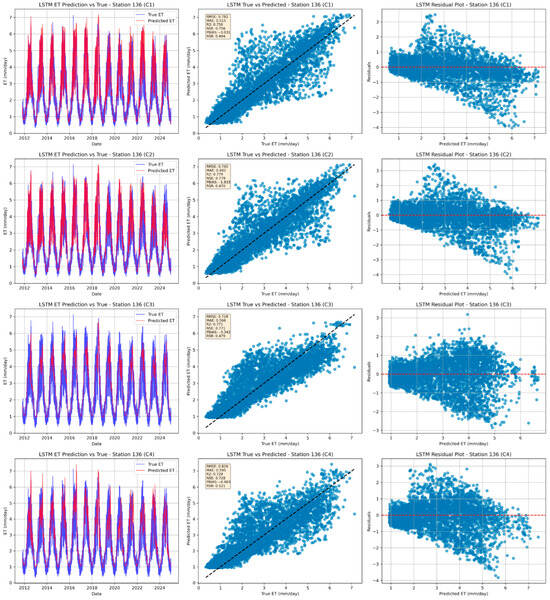

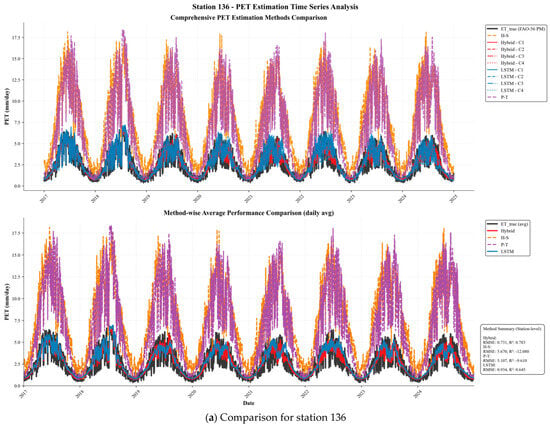

For the standalone LSTM model, the findings indicate that C1 yields the lowest RMSE and MAE in most stations. The R2 and NSE for C1 range from 0.599 to 0.756, indicating high predictive power. At some stations (136 and 284), there is a higher performance (R2 > 0.75) (Figure 3). In contrast, stations 272, 159, and 273 have a relatively lower predictive ability (R2 = 0.522–0.635), which can be attributed to local microclimatic variability and potential data heterogeneity, which affect the model’s accuracy.

Figure 3.

Comparison of different input combinations (C1–C4) at station 136 by a standalone LSTM model during the testing period.

The input combination C2, without RH, shows slight differences from C1, with subtle improvements at some stations (e.g., 136, R2 = 0.779), suggesting that the LSTM architecture partially accounts for this absence.

C3 and C4, which successively narrow the input variables to only temperature parameters (Tmin, Tmax, Tmean) or to the maximum and mean temperatures, have lower accuracy, especially at stations 159, 272, and 273, where R2 falls below 0.6. This highlights the shortcomings of relying solely on temperature-based inputs, as various meteorological drivers, such as wind speed, sunshine hours, and humidity, also affect PET dynamics.

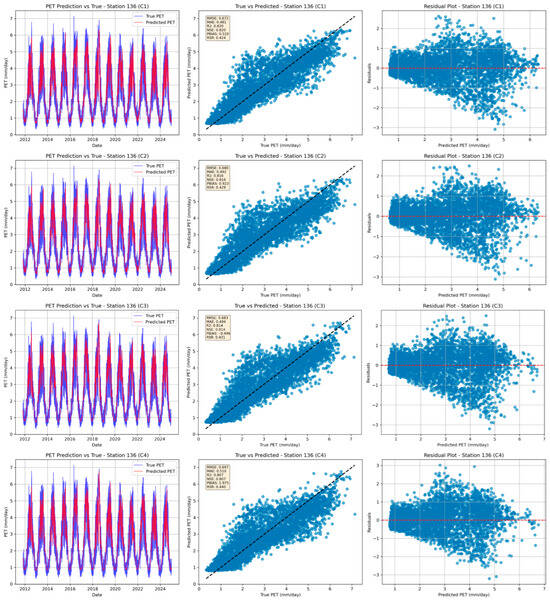

The hybrid CNN-BiLSTM attention mechanism consistently outperforms the standalone LSTM model across all stations, indicating the benefit of incorporating convolutional layers and attention mechanisms to learn both time-dependent and spatial heterogeneity. In the case of C1, R2 ranges from 0.626 to 0.820, with the best performance of the stations being 136 (R2 = 0.820) (Figure 4). The RMSE and MAE are lower than those of the standalone LSTM, and the RSR indicates that the model is more reliable. These results are supported by NSE, which shows that most stations had efficiencies above 0.7, suggesting the model’s ability to reproduce the observed PET patterns. The PBIAS values are usually close to zero at all stations, indicating a slight systematic bias and that the hybrid model is highly effective at estimating both low and high PET.

Figure 4.

Comparison of different input combinations (C1–C4) at station 136 by the Hybrid CNN-BiLSTM attention mechanism model during the testing period.

This location-specific analysis reveals that hybrid modeling significantly reduces errors at locations where the standalone LSTM performs poorly. For example, Station 136 shows a reduction in RMSE from 0.782 (LMST, C1) to 0.672 (CNN-BiLSTM, C1) and in R2 from 0.756 to 0.820, indicating that it better captures local PET variation. Similarly, stations 278 and 284 differ by about 5–7% in RMSE and MAE, highlighting that the convolutional feature extraction and attention mechanisms are more sensitive to strong and weak meteorological interactions.

C2, which does not include RH, is slightly less effective than C1 at most stations, but more effective in some cases (e.g., station 136; R2 = 0.816), suggesting that the importance of RH might be localized. Combinations C3 and C4 once again demonstrate reduced performance across the basin, underscoring the need to include the complete set of meteorological variables to estimate daily PET accurately. Complex climatic stations, e.g., 272 and 159, are especially vulnerable to reductions in input variables, and R2 falls below 0.65 under C3 and C4, indicating that temperature alone cannot be a sufficient predictor of hydrometeorological processes such as evapotranspiration.

This station-based analysis of the results supports the idea that the standalone LSTM can provide reasonable estimates of PET; however, the results are influenced by input selection and local climate variability. On the other hand, the CNN-BiLSTM attention model has better generalization and spatial robustness. Full-variable input combination C1 is recommended for estimating daily PET throughout the NRB because it yields the best predictive power, the least bias, and the most effective representation of the spatiotemporal variability of evapotranspiration processes. These findings highlight the importance of advanced DL frameworks, combined with extensive meteorological data, for effective hydrological modeling.

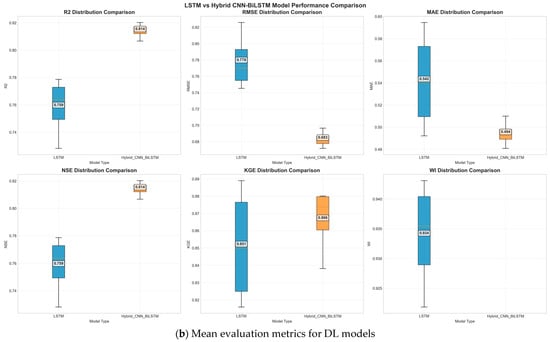

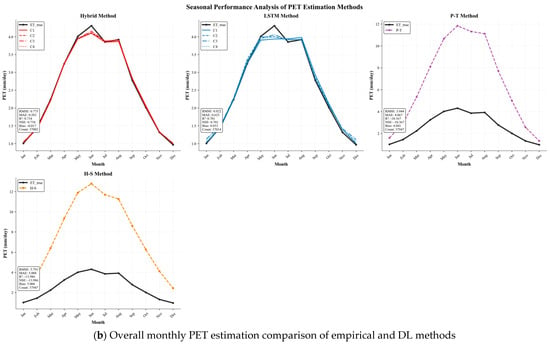

After evaluating different combinations, the overall performance of both DL models in NERB was assessed. Figure 5a,b also show that the hybrid CNN-BiLSTM model has a better predictive ability than the standalone LSTM for daily PET. Figure 5b shows that the median values are consistently higher and the dispersion is lower for the hybrid model’s performance indices (R2, NSE, and KGE), which also exhibit significantly lower RMSE and MAE. In particular, the hybrid CNN-BiLSTM achieves a median R2 and NSE of 0.814, higher than the LSTM’s 0.759. Similarly, the hybrid reduces RMSE from 0.778 to 0.683 mm/day and MAE from 0.542 to 0.494 mm/day. This advancement illustrates the hybrid model’s increased capability to represent non-linear, multivariable relationships among climatic variables and its resistance to local variations. The larger Kling–Gupta Efficiency (KGE = 0.866) also indicates a better agreement in reproducing the temporal distribution of PET. In contrast, the similar but slightly high Willmott Index (WI ≈ 0.935) indicates high overall consistency with the observed data.

Figure 5.

(a) Residual plots; (b) overall mean evaluation metrics between standalone and hybrid DL models.

These findings are further supported by the residual distribution comparison (Figure 5a), which shows that the residuals of the hybrid CNN-BiLSTM are more symmetrically distributed around zero and narrower than those of the LSTM. This suggests reduced bias and random errors, leading to more coherent, unbiased estimates across the dataset. In contrast, the LSTM residuals would be more dispersed, indicating that the predictions are less specific and that over- and underestimation occur at the extreme PET. The convolutional architecture of the hybrid model enables it to capture spatial-temporal dependencies and incorporates a bidirectional recurrent structure, allowing it to learn and effectively mitigate systematic biases.

Furthermore, spatial analysis reveals that hybrid CNN-BiLSTM models are more resilient to station variability and achieve higher predictive accuracy than standalone LSTM models (Figure S5). Their better performance can be attributed to the ability of CNN layers to identify temporal and inter-variable patterns, and to the attention mechanism’s capacity to prioritize the importance of various inputs that represent complex non-linear relationships.

3.2. Comparison Between Empirical and DL Methods

In a station-wise and basin-level comparison of empirical and DL methods, the empirical approaches performed poorly across the entire basin and at each station relative to the FAO-56 PM and DL models. The basin-wide RMSEs of H-S (5.79 mm/day) and P-T (5.04 mm/day) yield negative NSE values (−13.99 and −10.37, respectively), indicating that the two methods cannot reliably simulate daily PET in the NRB. Their negative NSE and low explanatory power indicate significant structural constraints when applied in a basin with high levels of climatic heterogeneity and intricate topographic gradients. The same result was found in single stations (e.g., RMSE 3.866 mm/day H-S, 4.85 mm/day P-T), which supports their inability to undergo spatial generalization. The empirical bias values, which are usually greater than 35 mm/day, also indicate the same overestimation relative to the FAO-56 PM reference. These trends underscore the need for more sophisticated modeling techniques and for developing hybrid DL models.

On the other hand, both LSTM and hybrid DL models showed a substantial performance improvement. At the basin level, the hybrid CNN-BiLSTM Attention models achieved RMSE of 0.775–0.778 mm/day, which is nearly an order of magnitude better than empirical baselines. Their NSE (0.732–0.734) indicates a high predictive ability, which suggests that the hybrid architecture is superior to empirical formulae. The Pearson correlation of 0.856–0.857 ensures that the hybrid DL models can capture the temporal dynamics of PET with fidelity. A slight bias also indicates a successful reduction in systematic errors, which are typically identified through empirical approaches.

Although it is expected that the superior performance of the standalone LSTM models compared with empirical methods stems from their ability to capture complex temporal dynamics, the hybrid models achieved further improvements by incorporating physical knowledge into the empirical formulations, thereby enhancing robustness and minimizing systematic errors. On the basin scale, the LSTM configurations yielded RMSE of 0.822–0.863 mm/day and NSE of 0.67–0.70. Although these indicators demonstrate the ability of recurrent networks to acquire PET relationships, the hybrid CNN-BiLSTM Attention model consistently yielded better results. The effectiveness of hybrid models stems from their ability to extract spatially relevant features (using CNNs), learn long-term temporal structure (using BiLSTM), and assign adaptive weights to significant inputs or time steps (with the help of the attention mechanism). This multimodal learning model achieves better accuracy and lower bias among stations.

In station-specific assessments, the hybrid models also achieved a consistent RMSE of less than 0.75–0.87 mm/day across all stations (with different climatic conditions in the NRB), along with a high NSE of 0.70–0.78. For example, hybrid models at Stations 136 (Figure 6a), 192, 278, and 279 had NSE of 0.77–0.79, which were significantly higher than H-S (−10 to −18) and P-T (−8 to −12). Even in places where empirical methods were especially ineffective, as at Station 278, where H-S had RMSE = 6.59 mm/day and NSE = −18.18, the hybrid model decreased the RMSE to 0.72 mm/day and increased the NSE to 0.77 (Supplementary File Figure S3). These uniform gains across heterogeneous climatic regions confirm the hybrid architecture’s ability to spatially generalize, supporting the appropriateness of DL for modeling PET in complex hydroclimatic environments.

Figure 6.

(a) Comparison for station 136. (b) Overall station-wise monthly PET estimation between the referenced FAO-56 PM and both the Empirical and DL methods.

The LSTM models showed reasonable improvement across all stations. The mean RMSE was 0.75–0.97 mm/day, and NSE was between 0.52 and 0.76. The standalone LSTMs, despite being worse than the hybrid models, were much better than the empirical methods, demonstrating that temporal DL methods are more appropriate for capturing non-linear climatic interactions governing PET.

Regarding the second objective, the station-level outcomes show substantial heterogeneity in PET estimation difficulty across the basin. The inter-station correlations (r ≈ 0.83–0.89) between the hybrid model predictions and the FAO-56 PM reference at each of the stations are high, and this is an indication that the hybrid DL models can be used to predict both the short and long-term seasonal variations in PET effectively, hence giving plausible inputs to the basin-scale hydrological assessments. The time-series plots in Supplementary Figure S3 support the numerical results.

Figure 6b compares month-based daily PET at the station in the NRB, and once again, the performance of the empirical and DL models is clearly different. There was a significant deviation in H-S and P-T, with negative R2 and NSE in most months, indicating that the FAO-56 PM method cannot accurately explain the temporal variability of PET. The standalone LSTM and hybrid DL models, including the CNN-BiLSTM attention architecture (C1–C4), on the other hand, performed much better than the empirical models, with a significantly lower RMSE and MAE, and achieved the best correlation with the reference PET in the hybrid C1 and C2 DL models.

The hybrid CNN-BiLSTM model with an attention mechanism developed in this study has three main contributions to daily PET prediction: (i) the combination of convolutional feature extraction and bidirectional memory enhances learning of multivariable and time-dependent patterns that are difficult to predict; (ii) the attention mechanism makes the model much easier to interpret as it adapts the weight of the influential meteorological signals; and (iii) the proposed feature engineering and informed hyperparameter configuration is highly promising for improving the predictive accuracy and spatial robustness of diverse climatic stations.

4. Discussion

Daily PET is a crucial aspect of hydrological modeling, climate impact assessment, and agricultural water management; however, accurately estimating it is a key component of these activities. The majority of the past NRB research has focused on water quality [27,28,30], sediment processes [31], or hydrological extremes, including drought and streamflow change [33,34]. The direct examination of PET has been carried out in only a limited number of studies, e.g., the P-T spatial PET assessment based on MODIS by Sur et al. (2012) and the basin-scale PET climatology by Ha and Kim (2025) [35,36]. In this context, the study is substantively valuable as it presents the empirical comparison of PET equations (FAO-56 PM, P-T, H-S) with advanced hybrid DL models, such as the CNN-BiLSTM model, for daily PET prediction at high spatial and temporal resolution in the NRB. In particular, it measures differences in performance between methods, shows that hybrid DL models have higher predictive power, and presents a basin-wide assessment framework that captures geographical and seasonal heterogeneity in PET processes.

One of the main differences between this work and previous studies in the NRB is the combination of empirical formulations (FAO-56 PM, P-T, H-S) with current temporal–spatial DL. Sur et al. (2012) applied MODIS images to generate PET fields using mostly P-T formulations of the energy balance, which, although useful for large-scale spatial analysis, lacked temporal fidelity to estimating daily PET and failed to represent localized microclimate variations [36]. Similarly, Ha and Kim (2025) provided a significant starting point for interpreting long-term PET and precipitation dynamics; however, they failed to assess predictive models or compare methodologies, leaving unanswered the question of which techniques are best for predicting daily PET under the influence of monsoon variability [35]. The given gap is filled by the present study, which shows that standalone LSTM and, particularly, hybrid CNN-BiLSTM models achieve superior performance across all stations, reducing RMSE by 50–70%. The R2 and NSE values are also positive, even under highly variable seasonal conditions.

Comparing these results with PET modeling studies of analogous humid and monsoon-impacted areas, the findings are very consistent with the rest of the hydrological literature, which indicates that DL is superior to empirical formulations. Empirical PET methods also performed poorly in studies of humid Southwest China, and ML methods, such as ELM, GANN, and WNN, improved accuracy considerably [42]. Similarly, Fan et al. (2018) have demonstrated that SVM, ELM, and ensemble tree models outperformed empirical models in various climatic regions [43]. These similarities support the argument that empirical equations, which have been designed to fit smaller climatic regimes, such as arid zones in the case of H-S or warm-humid environments in the case of P-T, cannot be applied to the NRB meteorological environment.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to be conducted in the NRB to directly compare popular empirical PET formulations (FAO-56 PM, P-T, H-S) against advanced hybrid deep-learning architectures, i.e., CNN-BiLSTM. Past NRB research has either been based on large-scale PET climatology or on empirical or remote-sensing-only methods, without assessing or comparing predictive model performance in space and time. The combination of empirical physics-based modeling with current state-of-the-art DL approaches, and a rigorous comparison between them on an everyday time scale, makes this study a methodological contribution to water managers and hydrologists in the basin.

This contribution is particularly significant as abrupt seasonal changes, such as the onset of monsoons, rainfall pulses caused by typhoons, and dry periods in the winter, have a substantial impact on the hydrological behavior of the NRB, and the empirical PET methods find it difficult to represent, as they have overly simplistic climatic assumptions. Conversely, the hybrid CNN-BiLSTM models successfully captured the non-linear, lagged associations among temperature, humidity, radiation, and PET, as indicated by strong inter-station correlations (r = 0.83–0.89) with the FAO-56 PM reference PET throughout the basin.

Similar improvements in predictive ability have been reported by international studies that used advanced DL to estimate PET. Li et al. (2024) achieved an R2 = 0.95 in the Northeast of China by combining wavelet denoising, empirical mode decomposition, CNN, and LSTM [22]. Pino-Vargas et al. (2022) discovered that hybrid indirect models (empirical equations with neural networks) performed better than either empirical or ML models in arid areas of the Atacama Desert [5]. These studies emphasize the fact that hybrid architectures are more precise. This study applies the philosophy of hybrid modeling to a humid monsoon basin. It demonstrates that attention-enhanced CNN-BiLSTM networks are more effective in both high- and low-variability settings.

The explicit analysis of geographical and temporal heterogeneity in PET and model performance across NRB sites is a significant methodological addition of the current study. Such granularity was lacking in earlier Korean PET studies; for example, Sur et al. (2012) reported PET geographical patterns but did not assess model performance variability [36], while Ha and Kim (2025) showed spatiotemporal trends without modeling options [35]. The current study reveals significant variation: stations in regions with considerable monsoonal influence or steep elevation gradients demonstrate larger empirical model errors and greater gains from hybrid DL models. Additionally, this work shows that hybrid DL models perform consistently throughout the year by analyzing monthly station-wise PET dynamics.

Despite the advancements it demonstrates, this study has some limitations. PET prediction was based on terrestrial meteorological stations, and the lack of stations or discrepancies in the station records could create uncertainty, especially in high-elevation or coastal sub-regions with significant microclimatic heterogeneity. This study does not include remote sensing factors, such as MODIS land surface temperature and radiation products, which would also increase spatial generalizability. Lastly, only the NRB was assessed using the hybrid models, and their applicability in other basins remains to be confirmed.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study compares the effectiveness of empirical and hybrid DL models in estimating daily PET at the NRB using the FAO-56 PM as a benchmark. The empirical P-T and H-S equations exhibited substantial deviations from the reference PET, with negative R2 and NSE at most stations and months, suggesting they were not particularly suitable in NRB. Conversely, the standalone LSTM and hybrid CNN-BiLSTM attention models demonstrated significantly higher accuracy, not only for the non-linear climatic interaction but also for the temporal dependence of PET dynamics. The hybrid architectures achieved low RMSE and MAE and exhibited high correlation with reference PET across spatially distinct stations, outperforming empirical methods during both the dry and wet seasons.

Spatial and temporal analysis also indicated that hybrid DL models were effective in reproducing monthly PET variability. They were robust to sudden changes in climate conditions, such as the onset of the monsoon and summer peaks. The higher climatic heterogeneity and elevation-driven microclimates at the stations also led to greater benefits from the DL-based predictions, highlighting the value of data-driven models in complex environments. This study provides three main contributions: (i) a comprehensive benchmarking of empirical, standalone DL, and hybrid DL models for PET estimation in the NRB; (ii) evidence that hybrid CNN-BiLSTM attention architectures substantially improve PET prediction accuracy across seasons and elevations; and (iii) a demonstration of the operational potential of hybrid DL models for supporting hydrological modeling and irrigation management in data-limited regions.

Future work should incorporate remote sensing products and test the possibility of generalizing the models to other Korean basins. Also, explainable AI methods can be implemented to increase the interpretability and operational acceptance of hybrid DL PET models.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18010032/s1. Figure S1: (a–l) Actual vs estimated PET with a standalone LSTM model during the testing and validation period at each station in NRB. Figure S2: (a–l) Actual vs estimated PET with the hybrid CNN-BiLSTM attention mechanism model during the testing and validation period at each station in NRB. Figure S3: Detailed station-wise comparison between the referenced FAO-56 PM versus Empirical and DL methods. Figure S4: Normalized attention weights during estimation by Hybrid CNN-LSTM Attention Mechanism Model. Figure S5: Spatial distribution of predicted PET with standalone and hybrid DL models across all stations. Table S1: Performance evaluation of the Standalone LSTM model over different input combinations (C1–C4) at each station in NRB. Table S2: Performance evaluation of the hybrid CNN-BiLSTM attention mechanism model over different input combinations (C1–C4) at each station in NRB. References [58,59] are citied in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

M.W.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft; S.M.K.: formal analysis, resources, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| PET | Potential Evapotranspiration |

| NRB | Nakdong River Basin |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PM | Penman–Monteith (FAO-56) |

| P-T | Priestley–Taylor method |

| H-S | Hargreaves–Samani method |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| NSE | Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency |

| KGE | Kling–Gupta Efficiency |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| Tmax | Maximum Temperature |

| Tmin | Minimum Temperature |

| Tmean | Mean Temperature |

| uz | Wind Speed |

| N | Sunshine Duration |

References

- Wanniarachchi, S.; Sarukkalige, R. A review on evapotranspiration estimation in agricultural water management: Past, present, and future. Hydrology 2022, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, C.; Xing, W.; Fu, J. Projecting the potential evapotranspiration by coupling different formulations and input data reliabilities: The possible uncertainty source for climate change impacts on hydrological regime. J. Hydrol. 2017, 555, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. Fao Rome 1998, 300, D05109. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Yu, K.; Li, P.; Jia, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Estimation of potential evapotranspiration in the Yellow River basin using machine learning models. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Vargas, E.; Taya-Acosta, E.; Ingol-Blanco, E.; Torres-Rúa, A. Deep machine learning for forecasting daily potential evapotranspiration in arid regions, case: Atacama Desert header. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, H.; Sun, S. Estimating daily reference evapotranspiration based on limited meteorological data using deep learning and classical machine learning methods. J. Hydrol. 2020, 591, 125286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, C.H.B.; Taylor, R.J. On the assessment of surface heat flux and evaporation using large-scale parameters. Mon. Weather Rev. 1972, 100, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidian, S.; Serralheiro, R.P.; Serrano, J.; Teixeira, J.L. Parametric calibration of the Hargreaves–Samani equation for use at new locations. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 27, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaloo; Kumar, B.; Bisht, H.; Rajput, J.; Mishra, A.K.; TM, K.K.; Brahmanand, P.S. Reference evapotranspiration prediction using machine learning models: An empirical study from minimal climate data. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 956–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, J.; Nazemi, A.H.; Sadraddini, A.A.; Landeras, G.; Kisi, O.; Fard, A.F.; Marti, P. Comparison of heuristic and empirical approaches for estimating reference evapotranspiration from limited inputs in Iran. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2014, 108, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, G.H.; Samani, Z.A. Reference crop evapotranspiration from temperature. Appl. Eng. Agric. 1985, 1, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, A.; Mendicino, G.; Cammalleri, C.; Ciraolo, G. Regional-scale modeling of reference evapotranspiration: Intercomparison of two simplified temperature-and radiation-based approaches. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2015, 141, 04015022. [Google Scholar]

- Ippolito, M. Assessing Crop Water Requirements and Irrigation Scheduling at Different Spatial Scales in Mediterranean Orchards Using Models, Proximal and Remotely Sensed Data. 2023. Available online: https://tesidottorato.depositolegale.it/handle/20.500.14242/172965 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Jung, K.; An, H.; Lee, M.; Um, M.-J.; Park, D. Assessment of non-linear models based on regional frequency analysis for estimation of hydrological quantiles at ungauged sites in South Korea. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 52, 101713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Choi, H.I. Improved streamflow calibration of a land surface model by the choice of objective functions—A case study of the nakdong river watershed in the Korean peninsula. Water 2021, 13, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.B.; da Cunha, F.F. New approach to estimate daily reference evapotranspiration based on hourly temperature and relative humidity using machine learning and deep learning. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 234, 106113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Humphries, U.W.; Wangwongchai, A.; Dechpichai, P.; Ahmad, S. Potential of artificial intelligence-based techniques for rainfall forecasting in Thailand: A comprehensive review. Water 2023, 15, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmstorf, S.; Box, J.E.; Feulner, G.; Mann, M.E.; Robinson, A.; Rutherford, S.; Schaffernicht, E.J. Exceptional twentieth-century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.P.; Deka, P.C. An extreme learning machine approach for modeling evapotranspiration using extrinsic inputs. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 121, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisi, O.; Mirboluki, A.; Naganna, S.R.; Malik, A.; Kuriqi, A.; Mehraein, M. Comparative evaluation of deep learning and machine learning in modelling pan evaporation using limited inputs. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2022, 67, 1309–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fu, Z.-y.; Chen, H.-s.; Nie, Y.-p.; Wang, K.-l. Modeling daily reference ET in the karst area of northwest Guangxi (China) using gene expression programming (GEP) and artificial neural network (ANN). Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2016, 126, 493–504. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhou, Q.; Han, X.; Lv, P. Prediction of reference crop evapotranspiration based on improved convolutional neural network (CNN) and long short-term memory network (LSTM) models in Northeast China. J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamamba, M. Exploring Forest-Water Nexus in a Changing Environment of Kafue River Basin, Zambia; The University of Zambia: Lusaka, Zambia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.; Kim, C.; Jung, K.; Jung, H. Water level prediction model applying a long short-term memory (lstm)–gated recurrent unit (gru) method for flood prediction. Water 2022, 14, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Humphries, U.W. Artificial intelligence-driven precipitation downscaling and projections over Thailand using CMIP6 climate models. Big Earth Data 2025, 9, 583–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.; Pyasi, S.; Galkate, R. Estimation of evapotranspiration using CROPWAT 8.0 model for shipra river basin in Madhya Pradesh, India. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci 2018, 7, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Kim, J.; Jeon, H.; Kim, K.; Byun, I. Assessment of Nakdong River basin management: Target water quality achievement and future challenges. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2020, 20, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Woo, S.; Kim, W.; Kim, S. Evaluation of water quality interaction by dam and weir operation using SWAT in the Nakdong River Basin of South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Heo, J.; Kim, Y. Present and potential future critical source areas of nonpoint source pollution: A case of the Nakdong River watershed, South Korea. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 45676–45692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Piao, W.; Kim, C. Enhanced monitoring of water quality variation in Nakdong River downstream using multivariate statistical techniques. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 12508–12517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.-K.; Kang, W. Improvement of the Existing Flow Discharge-Sediment Load Regression Estimation Method Near the Nakdong River Estuary Bank (NREB). J. Coast. Res. 2024, 116, 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Son, K.I.; Jang, C.-L. Characteristics of sediment transportation and sediment budget in Nakdong River under weir operations. J. Korea Water Resour. Assoc. 2017, 50, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Cho, S.; Kang, D.K.; Kim, S. Analysis of the effect of climate change on the Nakdong river stream flow using indicators of hydrological alteration. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2014, 8, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Sur, C.; Chen, J. Extreme drought hotspot analysis for adaptation to a changing climate: Assessment of applicability to the five major river basins of the Korean Peninsula. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 4025–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.Y.; Kim, S.M. Spatio-temporal Analysis of Potential Evapotranspiration and Precipitation for Nakdong River Basin. J. Korean Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 67, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sur, C.; Lee, J.; Park, J.; Choi, M. Spatial estimation of Priestley-Taylor based potential evapotranspiration using MODIS imageries: The Nak-dong river basin. Korean J. Remote Sens. 2012, 28, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z.; Feng, S.; Kang, S.; Dai, X. Artificial neural network models for reference evapotranspiration in an arid area of northwest China. J. Arid Environ. 2012, 82, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, F. Evapotranspiration evaluation models based on machine learning algorithms—A comparative study. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 217, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Raghuwanshi, N.; Singh, R.; Wallender, W.; Pruitt, W. Estimating evapotranspiration using artificial neural network. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2002, 128, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudheer, K.; Gosain, A.; Ramasastri, K. Estimating actual evapotranspiration from limited climatic data using neural computing technique. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2003, 129, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.S.; Malek, M.A.; Abdullah, N.S.; Kisi, O.; Yap, K.S. Extreme learning machines: A new approach for prediction of reference evapotranspiration. J. Hydrol. 2015, 527, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Cui, N.; Zhao, L.; Hu, X.; Gong, D. Comparison of ELM, GANN, WNN and empirical models for estimating reference evapotranspiration in humid region of Southwest China. J. Hydrol. 2016, 536, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Yue, W.; Wu, L.; Zhang, F.; Cai, H.; Wang, X.; Lu, X.; Xiang, Y. Evaluation of SVM, ELM and four tree-based ensemble models for predicting daily reference evapotranspiration using limited meteorological data in different climates of China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 263, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Ma, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, F.; Yu, X.; Zeng, W. Light Gradient Boosting Machine: An efficient soft computing model for estimating daily reference evapotranspiration with local and external meteorological data. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 225, 105758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourani, V.; Elkiran, G.; Abdullahi, J. Multi-station artificial intelligence based ensemble modeling of reference evapotranspiration using pan evaporation measurements. J. Hydrol. 2019, 577, 123958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Al-Taey, D.K.; Omidi, A.; Yasir, A.H.; Abbood, S.A.; Topildiyev, S.; Pallathadka, H.; Rajab, R. Advancing agriculture with machine learning: A new frontier in weed management. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajković, S. Estimating hourly reference evapotranspiration from limited weather data by sequentially adaptive RBF network. Facta Univ. Ser. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2011, 9, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovic, S. Testing hourly reference evapotranspiration approaches using lysimeter measurements in a semiarid climate. Hydrol. Res. 2010, 41, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, H.; Farooque, A.A.; Abbas, F.; Acharya, B.; Esau, T. Computation of evapotranspiration with artificial intelligence for precision water resource management. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Nayak, P.; Sudheer, K. Models for estimating evapotranspiration using artificial neural networks, and their physical interpretation. Hydrol. Process. Int. J. 2008, 22, 2225–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Angstrom, A. Solar and terrestrial radiation. Report to the international commission for solar research on actinometric investigations of solar and atmospheric radiation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1924, 50, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, H. A model for the Priestley-Taylor parameter α. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1983, 22, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droogers, P.; Allen, R.G. Estimating reference evapotranspiration under inaccurate data conditions. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 2002, 16, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samani, S.; Vadiati, M.; Kishi, O. Deep Learning: A Game Changer for Spatio-Temporal Prediction. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371616713_Deep_Learning_A_Game_Changer_for_Spatio-Temporal_Prediction (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, B.; Pandey, A.; Tripathi, S.; Kumar, D. Modelling of runoff and sediment yield using ANN, LS-SVR, REPTree and M5 models. Hydrol. Res. 2017, 48, 1489–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, L.D.; Leech, N.L. Understanding correlation: Factors that affect the size of r. J. Exp. Educ. 2006, 74, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.