Abstract

The European Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) (WFD) aims to protect inland surface waters, transitional waters, coastal waters and groundwater. The overarching goal of the WFD is to reach a good aquatic ecosystem throughout all of Europe. With the aim of reaching this goal, article 4 of the WFD sets certain environmental objectives. According to article 4 of the WFD, all the surface water bodies falling under its scope should be of good chemical and ecological quality by the end of 2027, as most extension deadlines will expire. For artificial and heavily modified surface water bodies—which make up the vast majority in the Netherlands—the goal is not to achieve a good ecological status but instead a good ecological potential and a good chemical status. Point source discharges may have a major impact on water quality and in order to progress, a well-functioning permitting, supervision and enforcement (PSE) process is of considerable interest. So far little academic attention has been paid to the functioning and quality of the governance processes underlying the PSE process. This paper aims to reduce this knowledge gap by conducting a case study on Sitech, the wastewater company for the Chemelot industrial complex in Geleen in the province of Limburg, the Netherlands. We first elaborate on an assessment framework consisting of 18 good governance criteria. The framework is used to assess the permitting, supervision and enforcement process concerning the discharges of Chemelot industrial plant. Our assessment reveals that, despite significant improvements over the last decade, good governance in this case is only partially achieved. While in terms of accountability and resilience the process shows robust strengths, gaps are found in its inclusiveness, effectiveness and transparency. We conclude our paper with some reflections on the generalizability of our findings and some suggestions for further research and policymaking.

1. Point Source Pollution: Today’s Issue, Tomorrow’s Crisis?

Improving water quality in the densely populated Dutch delta is challenging [1]. Meeting the European Union (EU) cornerstone objectives—as established by article 4 of the Water Framework Directive (WFD)—for a “good” status in 2027 for surface and ground water bodies is by no means assured [2]. The 2024 Mid-Term Evaluation indicates that the Netherlands remain significantly off-track, as only a small percentage of water bodies are projected to achieve both the required ecological and chemical standards by 2027, the already extended deadline [3]. Since the inception of the WFD in 2000, progress has been made [4], but only about 1% of Dutch surface waters meet all WFD criteria, with most water bodies rated “moderate” to “poor” regarding their ecological status and rated “failing to achieve good” regarding their chemical status [2]. Even though these numbers must be put into perspective (surface water bodies are, for example, only considered to have a “good” chemical status if all substances do not exceed the environmental quality standards established), more action is needed. Lagging water quality can be attributed to multiple factors but industrial point source discharges are seen as one of the issue’s main culprits [5].

The Netherlands have been previously praised for its success in reducing point source discharges [6]. However, progress has stalled in recent years [5]. Under headlines like “Claessen Tank Cleaning is dumping litres of carcinogenic substances into the Meuse River”, popular media have begun reporting on how environmental regulations protecting surface waters are being violated by industrial discharges. The criticism is stark: authorities have responded with leniency, inaction and a lack of discipline. Despite being aware of permit violations, for too long, they issued only benign warnings rather than moving towards imposing penalties or ordering closures when necessary [7].

Against this backdrop, the question can be raised as to whether the Claessen case represents an anomaly or instead a general trend in the governance of point source pollution (PSP) in the Netherlands. However, the governance of PSP—and in particular, the permitting, supervision and enforcement (PSE) process in the Netherlands—has received very scant academic attention. This neglect is particularly striking given the impending 2027 deadlines for the WFD objectives. After this date, member states are no longer allowed to postpone the deadline of meeting a good ecological and chemical status on the grounds of disproportionate costs or for reasons of technical feasibility (other exemptions may be invoked, but that is beyond the scope of this paper). Our paper seeks to narrow the above-mentioned knowledge gap. More specifically, the paper aims to obtain insight into the quality of governance processes [8,9,10] concerning the PSE of point sources discharges.

In order to meet this aim, we first review the literature on good governance, clarify relevant regulations and synthesize the findings of this review into a framework for assessing permitting, supervision and enforcement practices. Subsequently, in Section 3, we explain why we have chosen the PSE governance practice concerning the discharges of Sitech (the wastewater operator for Chemelot’s industrial complex in Limburg) as a case study, as well as our data collection and analysis. Following this, we present our assessment results and clarify what strengths and weaknesses were identified in the case. Next, we discuss the generalizability of our case study results and refer to the more systemic issues we identified. We conclude the paper with some recommendations for future research and policymaking.

2. Towards a Framework for Assessing the Governance of Point Source Discharges

The literature reveals several good governance principles. We first discuss them, and based on a review of relevant documents, refine them into criteria for assessing the governance of the PSE of point source discharges (see Table 1).

Table 1.

A framework for assessing the quality of the permitting, supervision and enforcement process concerning point source discharges.

The concept of good governance, introduced by the World Bank in 1989 and later adopted by the UN, originated from development discourse [8,11]. It has since been integrated into various policy areas and embraced by policymakers [12]. In recent decades, academic interest in good governance has grown significantly. The concept diverges from traditional assessment models by emphasizing the importance of non-hierarchical policymaking approaches and principles like accountability and transparency [13]. However, the definition and interpretation of good governance remain context-dependent [14] and have therefore resulted in a proliferation of diverse principles in the academic literature. Against this backdrop, Lockwood [9] streamlined these principles into a comprehensive good governance framework. While initially applied to assess terrestrial resource management, this framework has been adapted to different environmental governance contexts (e.g., [15,16]). This study adopts Lockwood’s [9] key principles of legitimacy, transparency, accountability, inclusiveness and resilience and supplements it with governance effectiveness. The latter principle is added since it is often used in policy evaluation [10].

Different interpretations of governance effectiveness can be found in the literature [17,18,19,20,21]. Some argue effectiveness relates to the capacity of policies and actors to address problems and achieve goals [22], while others define it as the extent to which an organization meets predetermined objectives [23]. The latter view is more prevalent, with effectiveness often seen as the degree to which environmental policies achieve intended improvements [20,24,25]. Yet, high goal-attainment effectiveness, as seen in industrial pollution control, does not always solve the initial problem [17]. Wuijts [26] therefore distinguishes between legal effectiveness, focusing on whether governance meets legal objectives, and ecological effectiveness, which emphasizes achieving a healthy ecosystem where native species thrive.

Legitimacy is essential for the ethical acceptability of governance [13,27] and refers to the acceptance and justification of political authority [28]. Challenges to legitimacy often arise from tensions between general and particular interests, particularly in environmental regulations [29,30]. Legitimacy encompasses two key aspects: (1) the entitlement and generation of authority [13] and (2) stakeholders’ acceptance of policy outcomes [28]. Lockwood [13] and others [28,31] emphasize that legitimacy requires governing actors to demonstrate commitment and responsibility, as it is not automatically granted through legal or democratic frameworks but depends on stakeholder acceptance and performance. Thus, legitimacy is defined by (1) legal or democratically mandated authority and (2) stakeholders freely accepting the governing body’s authority [13].

Scholars argue that transparency is crucial for (1) evaluating the legal, ethical and rational basis of decisions [13]; (2) understanding motivations [32] and (3) comprehending government actions [13]. Transparency implies that stakeholders have access to relevant information about decision makers, the way decisions were reached and the reasons for the decisions made [13]. It juxtaposes secrecy with deliberate information disclosure [33,34]. In the context of point source pollution regulation, Rohmana et al. [35] demonstrate that government transparency enhances accountability across industrial and governmental sectors. Clear reporting about progress made is pivotal. The way information is presented matters, especially for people unfamiliar with a topic who need clear and easy-to-understand language [13].

Bovens [36] (p. 450) argues that accountability refers to “a relationship between an actor and a forum in which the actor is obliged to explain and justify its behaviour, in which the forum can ask questions and pass judgement, and the actor can face consequences” (see also [37,38]). Jordana et al. [39] refine this by making a distinction between upward, downward and horizontal accountability [40]. Lockwood [13] also adopts this approach and further operationalizes it by stating that ideally the governing body (1) has clearly defined roles and responsibilities; (2) is accountable to its constituency (“downward” accountability); (3) is accountable to higher authorities (“upward” accountability); (4) demonstrates acceptance of its responsibilities and, finally, (5) ensures that the levels at which power is exercised match the scale of associated rights, needs, issues and values.

Inclusiveness refers to opportunities for all stakeholders to participate in and influence decision-making, which is rooted in the ethical principle that everyone has an equal right to contribute to matters affecting them [13]. Inclusiveness involves providing participation opportunities, creating structures that enable meaningful contributions, ensuring that voices are heard, seeking diverse inputs and recognizing varied perspectives [41]. Inclusiveness is vital for governance success, as it integrates local knowledge, enhances decision acceptance and improves implementation, boosting both effectiveness and legitimacy [42,43]. Lockwood [13] adds to this that inclusiveness plays a role in managing competing interests and mediating conflicts. Lockwood points out the importance of active engagement of marginalized and disadvantaged groups.

Finally, resilience refers to institutional adaptability, requiring authorities to (i) take an intentional approach to managing change (meaning it is not only reactive, but also proactive) and (ii) maintain flexible processes to respond to shifting conditions [13]. This adaptability is grounded in “bounded rationality,” acknowledging that knowledge about today’s and tomorrow’s knowledge about socio-ecological systems will always be incomplete. Organizations that are strategic, forward-looking and innovative can therefore better anticipate changes, reduce surprises and adapt to community needs. Effective self-reflexivity [44] is essential, enabling organizations to learn through ongoing assessments, supervision and reviews, improving decisions and adapting plans based on new information. Although legal frameworks can have adaptive features, it should be noted that they are inherently less resilient due to their focus on stability and predictability, which can create rigidity and hinder rapid adaptation to emerging challenges [26,45].

In order to refine and contextualize these six good governance principles, we analyzed European and Dutch legal frameworks relevant to the PSE of point source discharges. The WFD prohibits the deterioration of the water bodies falling under its scope (the larger bodies) and obligates member states to improve the quality of those waters. The Priority Substances Directive (2013/39/EU) (a daughter directive of the WFD) specifies water quality standards for (groups of) harmful substances. The WFD objectives are nowadays (since 2024) implemented in the Dutch Environment and Planning Act (Dutch: Omgevingswet (which integrated (among other laws) the former Water Act) and the Decree on the Quality of the Living Environment (Dutch: Besluit Kwaliteit Leefomgeving, BKL)).

According to the Decree on the Quality of the Living Environment, a proposed point source discharge may in principle not cause deterioration of a receiving WFD surface water body or hinder the achievement of a “good status”. When assessing point source discharges, water management programs (Dutch: water (beheer) programma’s), which entail measures to reach the WFD objectives, must be considered.

The Decree further aims to achieve compliance of point source discharges with the WFD’s obligations and (national) standards by taking into account the use of European and Dutch information documents. The latter consist of a General Method of Assessing Discharges (Dutch: Algemene Beoordelingsmethodiek, ABM) and an immission test, for which a Handbook has been developed.

The General Assessment Method must be followed to classify substances or mixtures that are present in a discharge by their water objectionability (Dutch: waterbezwaarlijkheid). The latter is based on intrinsic (eco)toxicological properties such as bioaccumulation and persistence. This classification determines the required level of remediation effort to be undertaken (Dutch: saneringsinspanning), such as substitution or treatment. Subsequently, a best available techniques (BAT) assessment is required to ensure that emissions are further minimized at the source. BAT refers to the most effective treatment techniques that are technically and economically feasible for a particular sector. When selecting appropriate treatment techniques, a competent authority is obliged to consider the best available techniques included in the so-called (European) BAT conclusions. These conclusions are addressed in the BAT reference documents (BREFs). However, the above assessments do not indicate whether the emissions remaining after application of the BAT are acceptable for the receiving water body. The Handbook addresses this. It is used to determine, based on different parameters, whether the remaining discharge will result in water quality standard exceedance or in a deterioration of the quality of the receiving water body. The Handbook is a method to assess whether the remaining discharges are compatible with the WFD objectives. Deviations are permitted only if duly justified, regardless of the fact that the proposed activity may not cause deterioration or hinder the achievement of a “good status” in the receiving surface water bodies [46].

Our analysis of the above-mentioned European and Dutch documents resulted in a refinement of the criteria for assessing the effectiveness principle. In criterion 1 we refer to the relevant regulations.

3. Materials and Methods

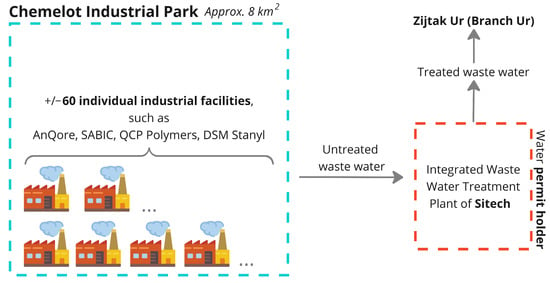

In order to obtain a better understanding of the governance quality of PSE processes in the Netherlands, we applied the good governance criteria mentioned in Table 1 to an assessment of the permitting processes concerning the discharges of Sitech’s integrated wastewater plant. In January 2024, Sitech changed its name into Circle Infra Partners, but for the sake of uniformity and readability, we retain the name Sitech. This plant treats wastewater from Chemelot industrial complex in Geleen, the Netherlands. Chemelot is one of the largest industrial complexes in Europe and the largest in the Netherlands, housing about 60 industrial facilities particularly known for its polymer production (i.e., plastics) [47]. Figure 1 presents a schematization of Chemelot industrial park and the Sitech integrated wastewater treatment plant. The plant discharges its effluents into the Ur, a branch of the Border Meuse (Dutch: Grensmaas), the section of the Meuse River that forms the border with Flanders. The Border Meuse is not only a resource for multiple drinking water utilities, but also a nature reserve. The Border Meuse qualifies as a WFD surface water body.

Figure 1.

A schematization of Chemelot industrial park and the Sitech wastewater treatment plant.

The granting of a discharge permit to Sitech by the Limburg Regional Water Authority in 2020 [48] received considerable media attention in regional and national newspapers. Several stakeholders were involved in the permitting process. Key (1st-tier) stakeholders, participating in so called Mutual Gains Approach (MGA) meetings, included Chemelot (Sitech), the Regional Water Authority Limburg, the Public Works Department of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management (Rijkswaterstaat) and the Drinking Water Companies Limburg, Evides and Dunea. Second-tier stakeholders included The Flemish Waterway, the Nature and Environment Foundation Limburg, Environmental Service South Limburg as well as the municipalities Stein and Sittard-Geleen. Given the significance of the permitted discharges and the societal and ecological importance of the receiving water, the case can be considered a critical case which could offer insights that have a wider relevance for the governance of point source discharges in the Netherlands.

In order to obtain insights into the quality of the PSE process, we studied relevant documents and conducted sixteen semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders involved in the PSE process and some experts. All participants were chosen for their work experience and/or expertise directly related to the permit. Table 2 shows that all 1st-tier stakeholders were represented in our sample. We only interviewed one 2nd-tier stakeholder, since our interviewees revealed that their actual involvement in the PSE process was very limited. We therefore did not expect them to be able to share detailed insights with us. Following Utrecht University research guidelines [25], participants signed a consent form beforehand. To uphold participant anonymity, detailed role descriptions were omitted from Table 2. Interview topics and questions were derived from Table 1’s good governance criteria. Interviews, lasting 30–70 min, were conducted either online via Microsoft Teams or in-person. The interviews took place during the first half of 2024. All interviews were recorded, transcribed and anonymized. A two-stage coding process [49] was applied using Atlas.ti (version 24.0.0): (1) initial line-by-line coding to categorize data segments and (2) focused coding to identify recurring and significant themes. The approach was both deductive (guided by the assessment framework) and inductive (allowing themes to emerge organically). We synthesized our findings and used a traffic light system to indicate to what degree the PSE process meets our good governance criteria (green = fully met, red = not met and yellow = partially met).

Table 2.

Overview of the interviewed organization (if no organization is given, the interviewee spoke in a personal capacity).

4. Results

In this section we present our findings. We will clarify to what extent the PSE process of Sitech’s discharges meets the criteria specified in Section 2.

4.1. Effectiveness

Table 3 shows that the PSE process meets several criteria, with full achievement of implementation and capacity (C2, C4), but reveals gaps in regulatory compliance and governmental commitment (C1, C3).

Table 3.

The effectiveness of the PSE process concerning the discharges of Sitech.

4.1.1. Permits’ Compliance with Existing Regulations

As stated before, permitting authorities must in principle use the General Assessment Method (ABM) and the applicable BREFs and perform immission tests to meet EU and national requirements. However, the interviewees questioned whether the granting of permits fully complied with these regulations

While WL and Sitech applied best available techniques reference documents (BREFs) to determine best available techniques (BATs) for source emission control using methods officially recognized as effective [50], respondents [6,13] noted this does not guarantee that the “most effective techniques are applied.” R13 explained, “The authority is obliged to apply the actual best available techniques and therefore “considers” what is stated in the BAT-conclusions. Importantly, when techniques are not specified in the BAT conclusions, but can be recognized as such, the authority is still obliged to implement them.” R6 added to this that “when an authority solely adheres to the BAT-conclusions, it does not set too strict requirements, because BREFs are not reviewed in a timely manner, […] making them outdated and not truly representative of the actual best available techniques.”

R8 (WL) also pointed out the outdated nature of current BREFs: “In some cases, we tried to go beyond these outdated BREFs, but that is “walking a tightrope” as Sitech only wants to adhere to the outdated BREFs.” R8 noted that pushing for better techniques requires evaluating economic viability, efficiency and unintended consequences—complex discussions that “you ultimately have to avoid.” According to R13 these discussions suffer from an expertise asymmetry, since “the best process-technologists work for companies, not for the authorities.” However, “If the authority has a clear idea of actual BATs, it has all means to win the debate […] it stands or falls with your argumentation.”

R13 directly challenged the stance that BAT discussions “should be avoided,” stressing the authority’s responsibility to enforce higher standards. R6 reinforced this: “It is up to the competent authority, and certainly the industries themselves, to be very critical [… and] apply the “actual” best techniques. One can remove and purify much more […] than when simply adhering to BAT-documents from 15 years ago.”

Other respondents confirmed that more advanced techniques do exist. R11, for instance, highlighted Sitech’s microplastic filter screens—which successfully capture particles for research [51]—questioning why this proven technology is not deployed daily, stressing, “This demonstrates that microplastics can indeed be filtered out. […] If you can capture microplastics for measurement, then you can also use the screens to reduce emissions.” Similar questions about the treatment efforts have been raised by local residents during a consultation session during a general board meeting of the Regional Water Authority [52]. In a public interview, Professor De Boer [53] not only supported the possibility of removing microplastics but also argued that nickel can be filtered out of emissions. Against this backdrop it was notable that during the process, the Public Works Department of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management was not consulted for advice, a missed opportunity to involve critical expertise on BAT implementation [R12].

Sitech’s immission testing followed the Handbook and was subsequently reviewed by Rijkswaterstaat to safeguard their Grensmaas interests. However, according to the interviews, the permitting authority (WL) seems to have ignored the obligation to “consider BAT+ measures” when the immission tests showed negative results [R6]. Instead, the authority “deferred from the Immission test for substances that did not succeed” [R12] to “give Sitech a chance to comply with the test” [R8]. R12 stated this was a specific “customization” for this permit. R13 criticized this customization: “In principle, this [interpretation] does not correlate with either the Handbook or the Water Framework Directive. According to the Handbook, it is not possible to grant permission for a discharge that does not fully pass the immission test” [R13].

R4, 6, 11 and 14 expressed their surprise that WL permitted the discharges, which did not pass the immission test, especially given the presence of substances of very high concern (SVHC). R14, for instance, argued, “The purpose of the immission test is not to permit a discharge, but to protect the receiving surface water. The prevailing water quality standards should ensure that the receiving surface water is adequately protected. Apparently, the law leaves room for interpretation, and this is being used to legitimize unjustified discharges.” R11 noted that, for instance, the discharges’ cyanide levels (18 μg/L) exceed ecological standards (0.23 μg/L). “By ignoring the Immission test, ecological considerations were simply not accounted for, and the issue of these substances will only be addressed much later”. R11 raised worries that economic considerations increasingly drive permitting decisions.

While R12 agreed that the authority should, in principle, always consider BAT+ techniques, R12 also pointed out pragmatic motives to be more lenient: “With the current permit, we observed that many substances still do not meet the immission test, and not a little bit, but some substances exceed up to 1000%, which is quite a lot. But, as an authority you can then act tough and say: “from now on, the discharge is not allowed anymore” because that is what the rules prescribe. However, we are also aware that, because it is an existing discharge that exists for decades, it is not responsible to refuse that discharge. Companies must be given the time to make adjustments to their processes.” According to the Nature and Environment Foundation Limburg [R4], WL remains unresponsive to questions about ignoring the immission tests.

4.1.2. Permit Formulation

Respondents, including critical environmental NGOs, generally agreed that the permit is well-formulated, with clear rules and exceptional detail in specifying all effluent substances. Views ranged from moderately positive, with critics acknowledging, “On paper, it is quite nice, and if those regulations are implemented properly, it would be quite good” [R11], to highly enthusiastic, with one calling it “an example of how all permits should be” [R16].

4.1.3. Reliability of the Commitment of the Government

In addition to setting emission limits, the permit imposes a result-based obligation to meet the standards of the immission test (rule 25) and two research obligations (rules 26 on the minimalization of Z and A substances and 36 on the minimalization of microplastics) that Sitech must fulfill during the permit term. These obligations aim to achieve further emission reductions in line with the General Assessment approach. However, compliance with the research and reporting requirements has been limited.

Specifically, rule 25, a result-based obligation, was not fully met in time, as not all substances comply with the immission test standards. Notably, WL has not taken enforcement action for these failures, as the following states [R12]: “For those substances that do not comply with the Immission test, BAT+ techniques will be considered in the next permit.”

The research and reporting obligations under rules 26 and 36 (2) were also not met on time. Both reports were deemed” inadequate” and “incomplete” [54], and the report initially due in April 2022 remains unfinished. Reports are not shared with stakeholders, respondents [8,9,11,12,16] clarified. R11 qualified the deadline exceedance of more than two years as highly problematic. On rule 26, the permit states, “The Daily Board of WL assesses whether feasible and affordable steps can be taken in the reduction in emissions to surface water” [48] (p. 42). However, without the reports, this step cannot be achieved. According to R11, “this rule aims to reduce the most hazardous and toxic substances that exist,” but due to delays, “really nothing is actually done with it by the regional water authority.” Some interviewees even spoke of strategic delays, since if reports are unfinished, WL cannot act based on them. R11 viewed these delays as structural and intentional: “They [Sitech] are actually stretching everything as long as possible, putting it off with their deceleration techniques”. Meanwhile, R16 qualified Sitech’s lack of fulfillment of its research and reporting as concerning. R12 stated that “it should not take too long, of course.”

Regarding enforcement, R6 pointed out a tension between the official (Dutch: ambtelijk) and administrative (Dutch: bestuurlijk) levels: “Often, violations are observed, but there is no enforcement in a practical sense. At the official level, people are very keen on enforcement, but at the administrative and political levels, it is a sensitive issue. […]” However, “enforcement also serves to show those who obey the rules that the rules actually matter.”

In 2024 the Daily Board of WL took more initiative in enforcing the rules, following a new “political direction within the Daily Board” and “a more critical attitude of the General Board,” as noted by R11. The Water Authority sought to enforce stricter environmental standards by amending the water permit for Chemelot industrial site, specifically aiming to mandate that two new factories (TKN and USG) cease the discharge of specific cooling water chemicals into the wastewater stream by 1 January 2026. However, the District Court of Limburg ultimately rejected this requirement, ruling that the Water Authority had failed to adequately justify the technical feasibility of the deadline and that the demand was disproportionate to the minimal environmental gain it would provide, a decision lamented by the Water Authority [55].

4.1.4. Capacity and Development

Most respondents did not express any capacity concerns. Respondents 8–10 argued that there were no capacity challenges regarding the PSE processes. They emphasized that due to the significance of Sitech’s discharges, they receive the highest priority within WL. Respondent 5 (WL) remarked that in other cases a lack of capacity might be an issue. The capacity within WL, however, appears to be robust, with a dedicated internal team charged specifically with Sitech’s discharges.

4.2. Legitimacy

Table 4 summarizes how the PSE process scores on the legitimacy criteria. It shows that although the Regional Water Authority Limburg has a legal or democratically mandated authority (C5), not all stakeholders fully accept this (C6).

Table 4.

The legitimacy of the PSE process concerning the discharges of Sitech.

4.2.1. Mandated Authority

Dutch law mandates WL with the authority to issue discharge permits in the Ur branch and execute their supervision and enforcement. This is affirmed by the 1985 Council of State’s ruling (ECLI:NL:HR 1985:AC8821). There is no jurisdiction that challenges this mandate. This criterion is therefore fully met.

4.2.2. Accepted Authority

The Regional Water Authority Limburg may have a clear mandate, but the Nature and Environment Foundation and the General Board Member of the Water Authority (respondents 4 and 11) did not fully accept its authority. In these participants’ opinion, the Water Authority was able to claim jurisdiction based on the idea that water flowing through a culvert or pipe can be considered surface water. However, in these respondents’ eyes, Rijkswaterstaat is the competent authority: “The discharge takes place into the Border Meuse, not in the Ur branch”, R11 argued; “the discharge occurs through an artificial concrete pipe that flows directly into the Meuse” “therefore, this [Branch Ur] cannot be considered surface water; that is just nonsense. It is argued that it is surface water because there is a natural outflow; however, it is nearly stagnant, with only a few litres flowing per day. In contrast, the outflow from Sitech is 1000 litres per second.” In this context, it is noteworthy that they view the aforementioned court ruling as “outdated, the judge relied only on what was described back then [….]. They often refer to this ruling as if it has eternal value, but there is now legislation that defines surface water differently.” In their view, “Today, the Zijtak Ur wouldn’t be classified as surface water.” R11 stressed the importance of this point, because they even believed the current “construction of discharging into the Zijtak Ur just a trick to ignore the WFD-objectives.”

R4 similarly contended, “Actually, it is just a direct discharge into the Meuse, and such a discharge should therefore also be assessed by the Public Works Department of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management (Rijkswaterstaat),” asserting that Rijkswaterstaat has greater expertise on complex permits and is typically more rigorous, which could have made a significant difference.

In contrast, other respondents saw WL as a competent authority and did not raise this issue. Even Rijkswaterstaat (which initiated, in 1985, a court case claiming authority) stated that “WL is the competent authority for the discharge.” R12 countered R4′s argument: “although Rijkswaterstaat generally has more expertise, we have been significantly downsized in the last decade regarding PSE, while WL has built sufficient expertise.”

4.3. Transparency

Table 5 shows that the PME process does not fully meet all the transparency criteria.

Table 5.

The transparency of the PSE process concerning the discharges of Sitech.

4.3.1. Appropriately Presented Information

Although water permits are public records, they can only be accessed on request. However, Sitech’s permit is a notable exception, since it is published on the websites of WL and the Clean Meuse Water Cycle initiative. Respondents emphasize the importance of publicly available permits for achieving a comprehensive view of watershed discharges. Nonetheless legalistic language and structure can make it difficult for the public to understand the permits. R13 therefore suggested that providing clear, simplified explanations of the permit’s structure and assessment process could be helpful.

Overall respondents agreed that the information presented met their needs. Drinking water sector representatives emphasized the importance of uninterrupted water intake and the need for transparency during emergencies. Sitech acknowledges this by immediately notifying control centers in case of emergencies and by reporting these to the Regional Water Authority Limburg (WL), Rijkswaterstaat and the Drinking Water Company Limburg (WML).

Almost all respondents highlighted the innovative nature of the permit in defining effluent composition, which “should be a showcase for future water permits” [R3]. R16 argued that this level of transparency is valuable because it provides insight into what is discharged, enabling drinking water companies to take targeted action if problems occur at intake points. [R16]: “Previously, we detected high levels of AMPA (SVHC) causing issues at drinking water intakes.” Knowing Sitech’s annual AMPA discharges allowed drinking water companies to focus more on reducing these AMPA levels. As a result, Sitech recently switched to an alternative chemical that significantly reduced AMPA levels in the Meuse. R5 emphasized the benefit of transparency for supervision, noting that “generally, supervision only takes place on what is stated or included in the permit.” If a substance is not clearly mentioned in a permit, it is not supervised, as “broader supervision requires a lot of capacity,” Therefore, by being transparent and clear about what is being discharged, supervision can be more effective, R5 maintained.

4.3.2. Transparent Reasoning

For Rijkswaterstaat and the Drinking Water Company Limburg (Dutch: WML), the reasoning underlying the permit is clear. R12 and R16 refer to the so-called Mutual Gains Approach, interactive stakeholder sessions during which relevant decisions were discussed.

However, R4 and R11 argued that the reasoning was “not evident at all.” R4 pointed out the opacity of procedures concerning the immission test, questioning how impacts on water quality were assessed and how permits were granted: “We also requested that information, but received little.” Indeed, the permit merely states Rijkswaterstaat advised on specific discharges (i.e., vanadium, mercury, AMPA, melamine and polymers), concluding “the discharge of the effluent will not jeopardize the WFD objectives of the Grensmaas and will not deteriorate [its] quality” [48] (p. 38). Further substantiation of the positive advice of Rijkswaterstaat is lacking. WL endorses this advice in the permit without any further reasoning. R12 acknowledged that the reasoning regarding the immission test and WFD “is not explicitly stated” in the permit, adding, “We are definitely going to do that in the next permit.” Overall, considering the motivation of the (postponed) immission test and compliance with the WFD, the reasoning is not fully evident.

The reasoning of WL regarding the application of the BAT is also not fully clear. WL has communicated to the public that “WL understands that there are people who [...] want to impose stricter permit conditions for discharges [...], but under current laws and regulations, this is not possible.” [R8]. Although, according to R13, other regional water authorities use similar reasoning [56], R13 explicitly stated that there were no legal barriers to exceeding the BREFs. Therefore, this reasoning would also benefit from a better explanation.

4.3.3. Open to Scrutiny

While the permit is seen as transparent, concerns do exist about the transparency of research and reporting obligations. First-tier stakeholders that participated in the MGA are more positive than external stakeholders.

First-tier MGA stakeholders do not routinely receive complete reports, but respondents [8,9,10,12,16] say they can be discussed upon request. External stakeholders, like nature organizations, note that reports are not actively shared, which creates ambiguity. R11 expressed frustration: “I have repeatedly requested access to the reports […] but the Daily Board of WL is not willing to, as the reports are not complete yet. […] There’s just persistent lack of clarity. It’s like a fog rising.”

WL claims an “above-average openness” [57]. R9 therefore did not agree with the need for a greater openness: “We think we already do more than other authorities, so we are not planning major changes.” R9 pointed out procedural compliance: “The MGA is transparent at the top, at least to all stakeholders. That is unique and no other authority has done that so far. [...] we follow the legal procedures such as views and appeals. So, in that respect, we follow the law nicely, and we are adding to that with the MGA.” R9 also revealed a preference for a passive approach, relying on the existing Open Government Act (Dutch: Wet Open Overheid) requests rather than proactive publication. However, they mentioned that an internal assessment would be necessary to determine if these reports fall under this Act. This hesitancy, coupled with the uncertainty concerning the applicability of the Open Governance Act request, creates a transparency gap and hinders scrutiny of the permit. This leaves stakeholders unaware of progress in emission reduction and of which of the non-compliant substances are meeting the standards. R12 (Rijkswaterstaat) acknowledged incomplete reports are not proactively shared but did not see this as problematic.

4.3.4. Evidence of Successes and Shortcomings

Most respondents underlined the permit’s innovative nature, noting that WL is “pioneering with this permit”. However, WL appears more willing to share this success than to communicate about shortcomings. While this tendency is natural, it hinders identification of areas needing improvement. Strong criticism in this regard came from R11: “WL and some stakeholders put out the message that everything is going well. You have to really dig to find the tricky points.” When asked if all substances now comply with immission standards (with no public data available), WL’s responses were indeed modest: “Yes… most do, yes”, which were later amended to “no, not all yet,” followed by assurances that “Sitech started working on it with full conviction.” Later, WL declined to reflect on this process outside the MGA sessions.

In public communications, WL proudly states that they sought a second opinion in 2024 on the permit under new legislation. This review found no reason to change the permit, with the Daily Board Member of WL expressing “never [having] doubted for a second the correctness of the permit” [58] (para. 3). A closer look at this second opinion, however, reveals a more nuanced reality, calling the WL’s approach merely legally “defensible” [59] (p. 40)—which is a different (and notably lower) standard than “correctness”. Moreover, the second opinion noted uncertainty regarding WFD adherence, stating that alignment remains unknown [59]. The latter, however, is not reflected in WL’s narrative: “In 2020, during the preparation for the permit […], the water authority consulted Rijkswaterstaat, as the water manager of the Border Meuse, whether the permit would align with the WFD. [The second opinion] states that this was legally sound” [58] (para. 6). This validation only confirms that the consultation process with Rijkswaterstaat was legally sound—not that the permit itself fully complied with the WFD.

4.4. Accountability

Table 6 shows our assessment of the PSE process on accountability criteria. Three criteria, clearly defined roles (C11), upward accountability to higher authorities (C12) and downward accountability to constituents (C13), were fully met. Acceptance of responsibilities (C14) was only partially achieved.

Table 6.

Accountability of the governing body for the PSE process concerning the discharges of Sitech.

4.4.1. Role Clarity

Many respondents argued that WL has drawn lessons from legal proceedings and court rulings concerning the unauthorized discharge of pyrazole (from 2015 to 2019). The "pyrazole case law" refers to the series of legal proceedings and court rulings from 2015 to 2019 concerning the unauthorized discharge of pyrazole into the Meuse River by Sitech, which involved the water authority Waterschap Limburg and several drinking water companies (see ECLI:NL:RBLIM:2015:9616; ECLI:NL:RBLIM:2017:10043; ECLI:NL:RBLIM:2017:10047; ECLI:NL:RVS:2019:3478) and has resulted in an improvement in WL’s accountability. WL now has a dedicated team of five officials with distinct roles for permit design, supervision and enforcement, supported by increased administrative resources. This development was also acknowledged by R11: “Although there seemed to be a lack of urgency in the first years, the executives are more on top of it now.” Rijkswaterstaat, the higher authority overseeing the Grensmaas, confirmed that WL has taken responsibility for the permitting process. R12 further noted, “Twenty years ago, WL was aware of the Immission test, but if it was inconvenient, it was simply ignored. In recent years, however, WL has built up sufficient expertise and has learned significantly from this process.”

4.4.2. Upward Accountability

In terms of upward accountability—where the governing body is accountable to higher authorities—the current permit’s design and rigor show that WL has learned from past shortcomings. All stakeholders praised the detailed description of the effluent composition, with respondents 1–3, 8–10, 12 and 16 noting that WL has taken responsibility. R16 stated, “WL has absolutely taken responsibility; this is an example of how it should be throughout Europe.” The permit recognizes the importance of drinking water, and the MGA sessions have resulted in a shift “from mutual distrust to constructive cooperation” [R3].

4.4.3. Downward Accountability

WL’s downward accountability—the accountability of WL to its constituency—is shown in its Daily Board’s thorough responses to public (including the industrial facility Sabic at the Chemelot compound and environmental NGOs) views on the draft permit [60], as underlined by R4. Downward accountability is also shown by WL in its reactions to the exceedance of the standards for vanadium and AMPA.

Vanadium and AMPA discharges already exceeded the standards in 2016. Therefore, a vanadium and AMPA study requirement was included in the 2016 permit, but as said, this has not resulted in sufficient improvement [48] (pp. 69, 72). Although some Daily Board Members argued for less strict rules (e.g., effort-based instead of result-based obligations), specific standards for vanadium and AMPA discharges were set in the permit to be met before the end of the permit period.

WL also showed accountability by setting up an evaluation process of the permit (on behalf of its General Board), which also includes an external legal assessment. R9 mentioned that insights from this evaluation will be incorporated into the next permit procedure, demonstrating a commitment to continuous improvement and learning.

4.4.4. Acceptance of Responsibility

While most respondents agreed WL has taken responsibility with this permit, evident in the “specification on substance level” and the “MGA,” some nuances must be made. First, as mentioned before, WL’s responsibility regarding the immission test seems to be questionable. R13 argued that in cases in which water quality standards have already been exceeded, “a regional water authority should not allow a discharge even if the pollution becomes manifest outside national borders. We don’t want particular substances in the water, and certainly not SVHC substances, that shouldn’t be possible.” Second, both WL and Rijkswaterstaat may not have fully accepted responsibility for a proper implementation of the WFD. R8 stated, “It’s a bit of a problem, because the full WFD assessment isn’t entirely within the Limburg Regional water authority’s competence. The discharge is into the Border Meuse, so Rijkswaterstaat’s is responsible for ecology and drinking water.”

In the permit WL refers to Rijkswaterstaat for the immission test, stating, “The advice from Rijkswaterstaat focuses on specific parameters such as vanadium, mercury, AMPA, melamine, and the presence of polymers. The advice does not indicate that the discharge of effluent jeopardizes achieving the WFD objectives for the Border Meuse or that it would degrade the water quality of the Border Meuse.” R12 added nuance to this remark: “For the WFD, an exercise was done for about 10 substances; however, not all WFD substances were assessed.” Whether the discharge violated the WFD, “We don’t know for sure until we have assessed all substances.” R12 explained that the WFD assessment was incomplete and concluded that the permit lacks sufficient substantiation, noting this must be explicitly addressed in the next permit.

4.5. Inclusiveness

Table 7 reveals a partial fulfillment of the inclusiveness criteria, with contested stakeholder participation opportunities (C15) and insufficient engagement of disadvantaged groups (C16).

Table 7.

Inclusiveness of the PSE process concerning the discharges of Sitech.

4.5.1. Stakeholder Participation

Our interviews revealed a lack of consensus among respondents regarding the inclusiveness of the stakeholder participation.

Respondents welcomed the MGA and agreed that it can bring diverse voices and perspectives to the table. R3 highlighted the importance of involving drinking water utilities early in permitting point source discharges, noting their expertise in identifying risks and managing challenges posed by certain substances. R3 and R16 emphasized that this input helps prioritizing necessary efforts, with drinking water companies providing specific feedback on substances and standards, both during the drafting phase of the permit and the permit term. R10 conveyed that drinking water companies also contribute to procedural changes: “One outcome of the MGA is that drinking water companies want proactive updates. This is now in the permit—if Sitech detects an exceedance, drinking water companies are informed immediately.” R9 confirmed the ongoing engagement of drinking water companies with WL’s bureaucratic and administrative levels ensures their concerns are discussed in permit revisions, thus strengthening checks and balances. R16 praised the MGA’s “open communication,” calling it effective in safeguarding drinking water interests: “For any relevant permit application, they should initiate such a process with downstream drinking water companies.”

Notable inclusivity concerns were mentioned by the Nature and Environment Foundation Limburg [R4] and one of the Board Members of WL [R11]. R4 found the current MGA “definitely not inclusive enough,” particularly for environmental organizations. R4 indicated that they had not been involved in the permit procedure, saying, “we’re in the second tier, meaning we’re only informed, not involved.” R11 expresses, “the MGA was designed exclusively for directly involved parties, with Sitech holding the most influence, as seen in the microplastics case.” Even though the WFD test has an ecological element, R11 argued ecological interests were “completely overlooked” in the assessments and the MGA, highlighting that drinking water standards often differ from ecological standards. R4 and R11 pointed out that, in particular, permit standards for substances of very high concern (SVHCs) frequently exceed ecological thresholds.

4.5.2. Actively Engaging Disadvantaged Groups

It is questionable as to whether all disadvantaged groups were actively engaged in the PSE process. Originally environmental organizations were not scheduled to participate at all in the MGA process—not even in the second tier (which only involves receiving annual updates). This changed after a joint statement of nine environmental organizations and some lobbying, but their inclusion in the second tier was considered meaningless [R4] [61]. As Natuurmonumenten, an environmental NGO, writes, “Organizations that operate based on environmental interests often have a lot of valuable knowledge and information. Especially in these kinds of complex processes, involving nature and the environment in advance is important. We regret that no party representing nature and environmental interests was invited in this MGA” [61] (p. 2). According to the Nature and Environment Foundation [R4], WL is reluctant to include environmental organizations in the first-tier of stakeholders. The foundation expressed interest in first-tier participation to both Sitech and WL but faced resistance.

Also, other first-tier stakeholders [R12 and R16] appeared to be unwilling to include environmental stakeholders. Their main concern was setting a precedent for broader participation, asking, “Who gets included and who doesn’t? Do we allow all environmental groups like Extinction Rebellion or the Plastic Soup Foundation? Once you open the door, it can slow the process down,” a point echoed by R16. Environmental respondents did not share these arguments, arguing that due to limited resources, they selectively participate and generally speak with one voice, as demonstrated by their joint statements [61]. The Association of River Waterworks [R3] also rejected concerns about precedent. While corroborating the MGA’s effectiveness for drinking water interests, the Association advocated for a broader perspective, emphasizing that environmental organizations should be involved because environmental interests do not always align with (or may subordinated to) anthropocentric drinking water interests: “Participants can give some guidance during the process [...] And those who look at it from an ecological perspective have a completely different set of considerations, so it would be good to include them as well.” Contrary to this, R12 argued that drinking water companies already provide sufficient oversight, thereby downplaying the potential value of environmental organizations: “There are sufficient critical eyes, such as from the drinking water companies. We don’t think the participation of environmental organizations will bring what is expected.” Consequently, several environmental organizations, including R4′s, are planning a joint lawsuit against WL: “As an organization, we strive for early involvement in processes in order to achieve our goals. However, given the current circumstances, but since that’s not happening now, we don’t see any other way”.

The Flemish government also felt excluded. In February 2024, the Flemish Waterway formally notified the Dutch government that discharges into the shared Border Meuse River violate the WFD [62]. While their primary argument concerns the discharge’s potential non-compliance with WFD objectives, they also highlight their exclusion from the permitting process: “The Dutch government and WL did not promptly confirm that they had consulted the Flemish government on the potential cross-border impacts during the permitting process for the Chemelot industrial complex” [62] (p. 6). However, WL has stated that the Flemish Waterway had “received all the information, including the application, supplements, and draft decision,” receiving no comments from them [48] (p. 90).

4.6. Resilience

Table 8 shows that the PME process scores well on the resilience criteria organizational learning (C17) and adaptive permit management (C18).

Table 8.

Resilience of the governing body of the PSE process concerning the discharges of Sitech.

4.6.1. Organizational Learning

In general respondents were positive about WL’s learning capacity and ability to absorb new knowledge. Respondents highlighted the acceptance of research obligations aimed at understanding discharges and identifying emerging substances and stressed WL’s significant improvements in recent years, particularly in addressing past permit issues, with the permit’s novelty—such as its detailed substance specifications and MGA collaboration—reflecting this learning ability [R3,R8–10,R12,R16].

4.6.2. Adaptive Permit Management

Discharges are permitted for a set period of seven years, which allows for regular review and updates. R13 stated, “This fixed duration facilitates addressing any significant issues that may arise, which would be considerably more challenging if the permit were granted indefinitely. With a fixed term, any challenges can be addressed at the end of the term.” R13 further argued that this permit’s 7-year term strikes a good balance: “It provides both the certainty a company needs and addresses public concerns.”

Under current law, authorities can (provided that certain conditions are met), initiate changes through own-initiative amendments in case of changing conditions. While the research obligation (i.e., rules 26 and 36) could in the future lead to such a WL-initiated revision, respondents [8,9,12,16] argued there is presently no reason to consider such a revision. In the words of R12: “We are halfway through the term and will start preparing for the next permit of 2027 soon. Opening the permit now might save half a year, but there are no urgent issues necessitating that. We also don’t see an issues for the WFD or microplastics”. R9 and R12 argued that “Sitech is only responsible for a small fraction of the microplastics in the Meuse” and “other substances [than microplastics] are currently much worse.” R11, however, criticized this lack of interim permit revisions: “Given the current data on the environmental risks of microplastics and the necessity for drinking water companies to filter these out, one would expect more stringent measures to reduce these emissions. Also, because techniques already exist. […] the Regional Water Authority is highly apprehensive about potential legal actions and financial repercussions”.

The Nature and Environment Foundation argued that new knowledge on emerging substances requires a stricter water objectionability classification of Sitech’s discharges. WL, however, refused their request [R4] but did approve Sitech’s requested reclassification to a lower water objectionability classification. Overall, there are ways to adapt to changing conditions, but these options are selectively utilized.

5. Discussion

In this paper, we aimed to obtain insights into the quality of the PSE processes concerning point source discharges in the Netherlands. This was performed by developing an assessment framework consisting of 6 good governance principles which were specified into 18 criteria. We applied this framework in a case study in which we assessed the granting of a discharge permit to Sitech—the wastewater operator for Chemelot’s industrial complex in Limburg. Our assessment indicates that, in this case, not all our good governance criteria were met. Overall the process has a high score on the resilience and transparency principles, but several challenges remain, especially those related to effectiveness and inclusiveness. A question can be raised regarding to what extent our case study insights are generalizable for PSE processes in the Netherlands as a whole and what more systemic governance issues can be identified based on our analysis. To what extent are the flaws our stakeholders revealed systemic issues? Since our interviewees were most critical about the effectiveness and the inclusiveness of the PSE process, we will discuss the challenges identified for meeting these criteria.

Whilst in our case study, the PSE process proved to be “unique” (in the sense that it was heavily prioritized by the relevant authorities), it did reveal systemic-level challenges that may impact effectiveness.

The use of outdated BAT conclusions can hinder the process of innovation and improving water quality. The consequences of using outdated BAT conclusions are also recognized outside the field of point source discharges [63]. However, authorities are reluctant to impose stricter or other requirements because this may expose them to legal proceedings.

A general concern is that permits may pose a threat to fulfilling the WFD objectives. Under the WFD, water authorities must reject an application if discharge is incompatible with the WFD objectives, as the non-deterioration principle and the improvement objectives are a binding constraint on all permitting decisions since Bund v. Germany was presented before the European Court of Justice [64]. In mandatory assessments of compliance, Dutch water authorities must consider the General Assessment Method and the Handbook. As stated before, the Handbook is a method to assess whether the remaining discharges (after applying the BATs) are compatible with set water quality standards, with deviations permitted only if duly justified, regardless of the fact that the proposed activity may not cause deterioration or hinder the achievement of a “good status” in the affected surface water bodies [46]. Our interviewees revealed that, in our case, the General Assessment Method and the Handbook were considered. However, the question remains as to whether this was performed correctly, especially for the substances for which the immission test was postponed. It is also not totally clear to what extent the discharge allowed can hinder the achievement of “a good status” in the receiving surface water body, and if it can, how the achievement of a “good status” can nevertheless be ensured. More in-depth legal research is needed to better substantiate both points. It is possible that this evaluation will reveal that additional measures must be taken.

The possibility of taking additional measures during the permit period is in line with the current Dutch national legal framework that seems to allow, when well-substantiated, changing (or even revoking) existing permits for point source discharges when this is necessary to achieve the WFD objectives. However, as also stated in the 2024 opinion on Sitech’s permit [59], the extent to which intervention is possible is not yet clear. More research is needed to determine the limits of this possibility.

In our case the permit was granted for a period of seven years. The WFD, however, does not explicitly stipulate that permits for point source discharges can only be granted for a (certain) fixed period. The WFD only requires permits for point source discharges to be reviewed “regularly”, thus not forbidding a system in which permits are granted for an indefinite period, as long as these permits are reviewed regularly and can be revised if necessary. Last year, in 2024, the European Commission started an infringement procedure against the Netherlands for non-compliance with the WFD because permits for point source discharges (and also for abstractions) can be granted for an unlimited period and periodic review is not always required and/or carried out in a timely manner. For discharges (and abstractions) falling under general rules, the same applies. Options for aligning Dutch law with the WFD on this point are being investigated.

Our interviewees revealed that, in our case licensing, was not hindered by capacity issues. However, this is not a general phenomenon. When it comes to capacity and development, other research shows that not all water authorities in the Netherlands have sufficient capacity (or have only recently gained sufficient capacity) for licensing, supervision and enforcement of permits [65].

The second principle to discuss concerns inclusiveness [13]. It is important to note that inclusiveness is not about “congruence” or “consensus”, nor is it about selectively choosing whose inputs to consider during the process: it is about allowing for friction between stakeholders so that diverse perspectives can be openly debated, leading to more robust and comprehensive decision-making [13]. Our findings revealed that, according to the interviews, environmental NGOs were structurally sidelined. In our case, the Water Authority seems to have adopted a minimal participation approach, with a focus on procedural efficiency. This approach proved counterproductive and undermined good governance: the exclusion of key actors, nature organizations in particular, from meaningful involvement directly fuelled public protests (notably by Extinction Rebellion) that the Authority must navigate. What may appear as a “transparency paradox”, greater permit transparency generating public opposition, can be better understood as a consequence of inadequate earlier-stage stakeholder inclusion [66]. The latter seems to be a systemic issue.

The concept of good governance has been widely applied in policy frameworks [16], but it has not yet been systematically applied in the context of PSE processes. This paper has reduced this knowledge gap, but it has some limitations in terms of conceptualization and the methods applied. Our analysis is mainly based on stakeholder perceptions, supplemented by an analysis of documents (including minutes of meetings) to which we have made references. However, a more in-depth legal analysis could have had an additional value as it could have led to a more refined assessment framework. In this way stakeholders could have been confronted with more specific legal requirements which could have revealed more in-depth findings. Moreover, a more detailed explanation of the way the WFD objectives were assessed (and their alignment with the ABM, including the quality of the immission tests performed) would have had an added value as well not only for the quality of our case study but also since it might have revealed more fundamental knowledge-related challenges that implementing agencies have to deal with in improving surface water quality. Future research on the governance quality of PSE processes could address these limitations. This can also be achieved in comparative studies in which more PSE processes will be assessed with the aim of finding more robust patterns and challenges in the ways in which the Netherlands deals with point source discharges.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, what should regional water authorities take away from this? Three lessons result from our study. Firstly, we argue that regional water authorities must prioritize transparency by clearly communicating the rationale behind permitted discharges, enforcement protocols and follow-up measures. In this way they can address growing public concerns and build institutional trust. Secondly, more effective work must be performed to update the best available techniques (BAT) documents (BREFs) and standards in a timely manner, as in their current, often outdated design, they may restrict permitting authorities’ options for imposing more rigorous requirements. Finally, regional water authorities should ensure that ecological interests are represented (by a spokesperson on behalf of environmental NGOs) and given explicit attention in every phase of the procedure, becoming an inherent part of the process instead of an afterthought. As this paper has shown, enhancing both transparency in permit documentation and inclusivity in stakeholder engagement will significantly improve regulatory oversight, enable better regional coordination and foster broader acceptance of permitting decisions. By addressing these challenges, governance can come closer to the “point source”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., C.D. and T.R.; methodology, A.K. and C.D.; validation, A.K., C.D. and T.R.; formal analysis, A.K.; investigation, A.K.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and C.D.; writing—review and editing, C.D. and T.R.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the interviewees participating in and consenting to this study. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their constructive feedback on an earlier draft of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management. (I&W). Betere Bescherming Waterkwaliteit is Noodzakelijk. Inspectie Leefomgeving en Transport. 18 June 2024. Available online: https://www.ilent.nl/actueel/nieuws/2024/06/18/betere-bescherming-waterkwaliteit-is-noodzakelijk (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving (PBL). Waterkwaliteit KRW, 2022. Available online: https://monovi.pbl.nl/indicatoren/nl143809-waterkwaliteit-krw-2022 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Rijksoverheid. Koepelrapport Tussenevaluatie KRW. 20 December 2024. Available online: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2024/12/20/bijlage-2-koepelrapport-tussenevaluatie-krw (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Kort, G. Hoe Staat Het Met de Voortgang van de Kaderrichtlijn Water in Nederland? Kenniscentrum Europa Decentraal. Available online: https://europadecentraal.nl/praktijkvraag/voortgang-kaderrichtlijn-water (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Wuijts, S.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Runhaar, H.A.C. Moving forward to achieve the ambitions of the European Water Framework Directive: Lessons learned from the Netherlands. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 333, 117424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Water Governance in the Netherlands—Fit for the Future? In OECD Studies on Water; OECD: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers, K. Liters Kankerverwekkende Stoffen Laat Claessen Tankcleaning zo de Maas in Stromen. NRC. Available online: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2023/07/26/liters-kankerverwekkende-stoffen-laat-claessen-tankcleaning-zo-de-maas-in-stromen-a4170584 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- World Bank. Sub-Saharan Africa: From Crisis to Sustainable Growth, 1st ed.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1989; pp. 1–300. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, M. Good governance for terrestrial protected areas: A framework, principles and performance outcomes. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bruijn, E.; Dieperink, C. A Framework for Assessing Climate Adaptation Governance on the Caribbean Island of Curaçao. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, R. The World Bank’s Good Governance Agenda. Narratives of Democracy and Power. Occas. Pap. 2004, 15, 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Handoyo, S. Worldwide governance indicators: Cross country data set 2012–2022. Data Brief 2023, 51, 109814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Thomann, E. Governance in Public Policy. In Encyclopedia of Public Policy; van Gerven, M., Rothmayr Allison, C., Schubert, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Iftimoaei, C. Good Governance: Normative vs. Descriptive Dimension. SEA Pract. Appl. Sci. 2015, 7, 309–316. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.H.; Lo, S.L. Principles of food-energy-water nexus governance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 155, 111937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeranz, E.F.; Stedman, R.C. Measuring good governance: Piloting an instrument for evaluating good governance principles. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2020, 22, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. The Effectiveness of International Governance Systems. In International Governance, Protecting the Environment in a Stateless Society; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 140–160. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, P.; Hall, A. Effective Water Governance; Global Water Partnership: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, S. Toward effective river basin management (RBM): The politics of cooperation, sustainability, and collaboration in the Delaware River basin. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, S.G.; Martin, J.; Wilkinson, D.; Newcombe, J. Reporting on Environmental Measures: Are We Being Effective? In Environmental Issue Report, No. 25; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hogl, K.; Kvarda, E.; Nordbeck, R.; Pregernig, M. Legitimacy and Effectiveness of Environmental Governance: Concepts and Perspectives; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, K.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Runhaar, H.A.C.; Widmer, A. On the necessity of connectivity: Linking key characteristics of environmental problems with governance modes. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 1821–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafritz, J.M.; Russell, E.W.; Borick, C.P.; Hyde, A.C. Introducing Public Administration; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Steinebach, Y. Administrative traditions and the effectiveness of regulation. J. Eur. Public Policy 2022, 30, 1163–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utrecht University. Reader Policy Evaluation. In Developed for the Course Policy Evaluation and Design; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wuijts, S. Towards More Effective Water Quality Governance: Improving the Alignment of Social-Economic, Legal, and Ecological Perspectives to Achieve Water Quality Ambitions in Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Steen, M.A.; van Twist, M.J.W.; Chin-A-Fat, N.; Kwakkelstein, T. Pop-Up Public Value; Netherlands School of Public Administration: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mees, H.L.P.T.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Runhaar, H.A.C. Legitimate adaptive flood risk governance beyond the dikes: The cases of Hamburg, Helsinki and Rotterdam. Reg. Environ. Change 2014, 14, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, V.; Edwards, A. Legitimacy and democracy: A conceptual framework for assessing governance practices. In Governance and the Democratic Deficit; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2013; pp. 35–60. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, S.C.; May, P.J. Information, interests, and environmental regulation. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2002, 4, 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buuren, A.; Driessen, P.; Teisman, G.; van Rijswick, M. Toward legitimate governance strategies for climate adaptation in the Netherlands: Combining insights from a legal, planning, and network perspective. Reg. Environ. Change 2014, 14, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addink, H. Good Governance: Concept and Context; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A. Transparency under scrutiny: Information disclosure in global environmental governance. Glob. Environ. Politics 2008, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Mason, M. Transparency in Global Environmental Governance: Critical Perspectives; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rohmana, Q.A.; Fischer, A.M.; Cumming, J.; Blackwell, B.D.; Gemmill, J. Increased Transparency and Resource Prioritization for the Management of Pollutants From Wastewater Treatment Plants: A National Perspective From Australia. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 564598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovens, M. Analysing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework. Eur. Law J. 2007, 13, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Gupta, A. Accountability and legitimacy. An analytical challenge for earth system governance. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1854–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mees, H.; Driessen, P. A framework for assessing the accountability of local governance arrangements for adaptation to climate change. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 671–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordana, J.; Bianculli, A.; Fernández-i-Marín, X. When accountability meets regulation. In Accountability and Regulatory Governance; Bianculli, A.C., Fernández-i-Marín, X., Jordana, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2015; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hernando, C.M.D. Public Accountability in Regulatory Governance. J. Public Aff. Dev. 2020, 7, 133–162. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, A. Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Challies, E.; Jager, N.W.; Kochskaemper, E.; Adzersen, A. The Environmental Performance of Participatory and Collaborative Governance: A Framework of Causal Mechanisms. Policy Stud. J. 2018, 46, 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrou, D.; Botetzagias, I. Stakeholders’ perceptions concerning Greek protected areas governance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacquant, L.J.; Bourdieu, P. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 1992; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhl, J.B.; Salzman, J. Introduction: Governing wicked problems. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2020, 73, 1561. [Google Scholar]

- ABRvS (Afdeling Bestuursrechtspraak van de Raad van State). Uitspraak van 27 July 2022, ECLI:NL:RVS:2022:2178, M en R 2022/81, met noot J.J.H. van Kempen. 27 July 2022. Available online: https://hse.sdu.nl/content/ECLI_NL_RVS_2022_2178 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Braun, R.; Schmitz, P. A Remote Monitoring Early Warning Solution for Ammonia Releases for the OCI Urea and Melamine Complex at Chemelot Industrial Park; Grandperspective GmbH & OCI Nitrogen B.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Regional Water Authority Limburg. (WL). Besluit Watervergunning; Regional Water Authority Limburg: Roermond, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Regional Water Authority Limburg. (WL). Beantwoording Aanvullende Artikel 35-Vragen PvdD Waterwetvergunning Sitech: Te Laat Rapport. Regional Water Authority Limburg. Available online: https://waterschaplimburg.bestuurlijkeinformatie.nl/Reports/Document/c5c81c87-e782-40a4-8ea8-310fafd1e009?documentId=108c75a2-0ef3-4727-97d0-d7839a8b9a87 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Circle Infra Partners. Chemelot op Weg Naar Minder Microplastics in Het Afvalwater; Circle Infra Partners: Geleen, Nederland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Regional Water Authority Limburg. (WL). Verslag Openbare Vergadering Algemeen Bestuur Regional Water Authority Limburg van Woensdag 27 September 2023. Available online: https://waterschaplimburg.bestuurlijkeinformatie.nl/Agenda/Document/49ce956a-3b02-4174-b4bf-a595ce141819?documentId=1f6f8472-17ae-43d7-b57c-0145d503238b&agendaItemId=d4a5c81c-1d7d-4360-855d-59cb3392eb32 (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- De Boer, J. Troebele Wateren. Pointer KRO-NCRV. Available online: https://pointer.kro-ncrv.nl/pointer-regio-de-giftige-maas (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Regional Water Authority Limburg. (WL). Toelichting Vergunning Sitech. Available online: https://waterschaplimburg.bestuurlijkeinformatie.nl/Agenda/Document/82b17537-5c49-4c6b-aded-f4cc7013f796 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Rechtbank Limburg (Limburg District Court). Uitspraak (Judgment), ECLI:NL:RBLIM:2024:4041. 2024. Available online: https://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/details?id=ECLI:NL:RBLIM:2024:4041 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Van Hooijdonk, A. Wetgeving Belemmert Waterschap Strengere Lozingseisen te Stellen. Waterforum. 2024, pp. 19–23. Available online: https://www.waterforum.net/wetgeving-belemmert-waterschap-strengere-lozingseisen-te-stellen/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Regional Water Authority Limburg (WL). Uitleg Lozingsvergunning Chemelot Circle. Available online: https://www.waterschaplimburg.nl/actueel/achtergronden-nieuws/lozingsvergunning-chemelot-circle/ (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Regional Water Authority Limburg (WL). Second Opinion Bevestigt Juistheid Lozingsvergunning Circle. 25 April 2024. Available online: https://www.waterschaplimburg.nl/actueel/2024/second-opinion-bevestigt-juistheid/ (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Van Der Feltz Advocaten. Advies Waterschap Limburg/Lozing ZZS (Sitech). 20 March 2024. Available online: https://www.waterschaplimburg.nl/publish/pages/8921/20-03-2024_advies_waterschap_limburg_vdf.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2024).