Effects of Herbivorous Fish on Competition and Growth of Canopy-Forming and Meadow-Forming Submerged Macrophytes: Implications for Lake Restoration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Water Quality

2.3. Measurement of Plant Traits

2.4. Growth of Macrophytes and Fish

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Nutrients, Phytoplankton Biomass, and Water Clarity

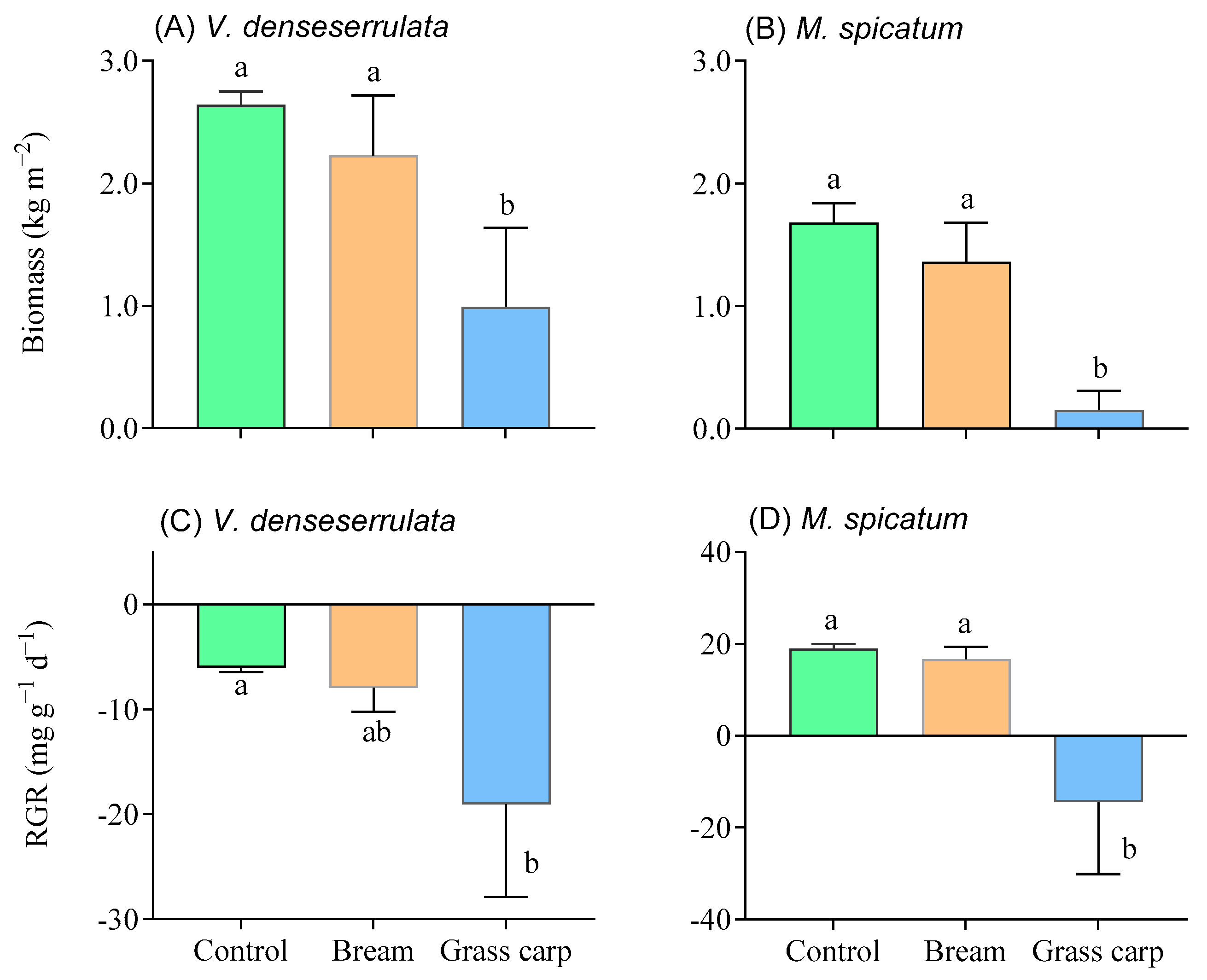

3.2. Plant Biomass and Growth

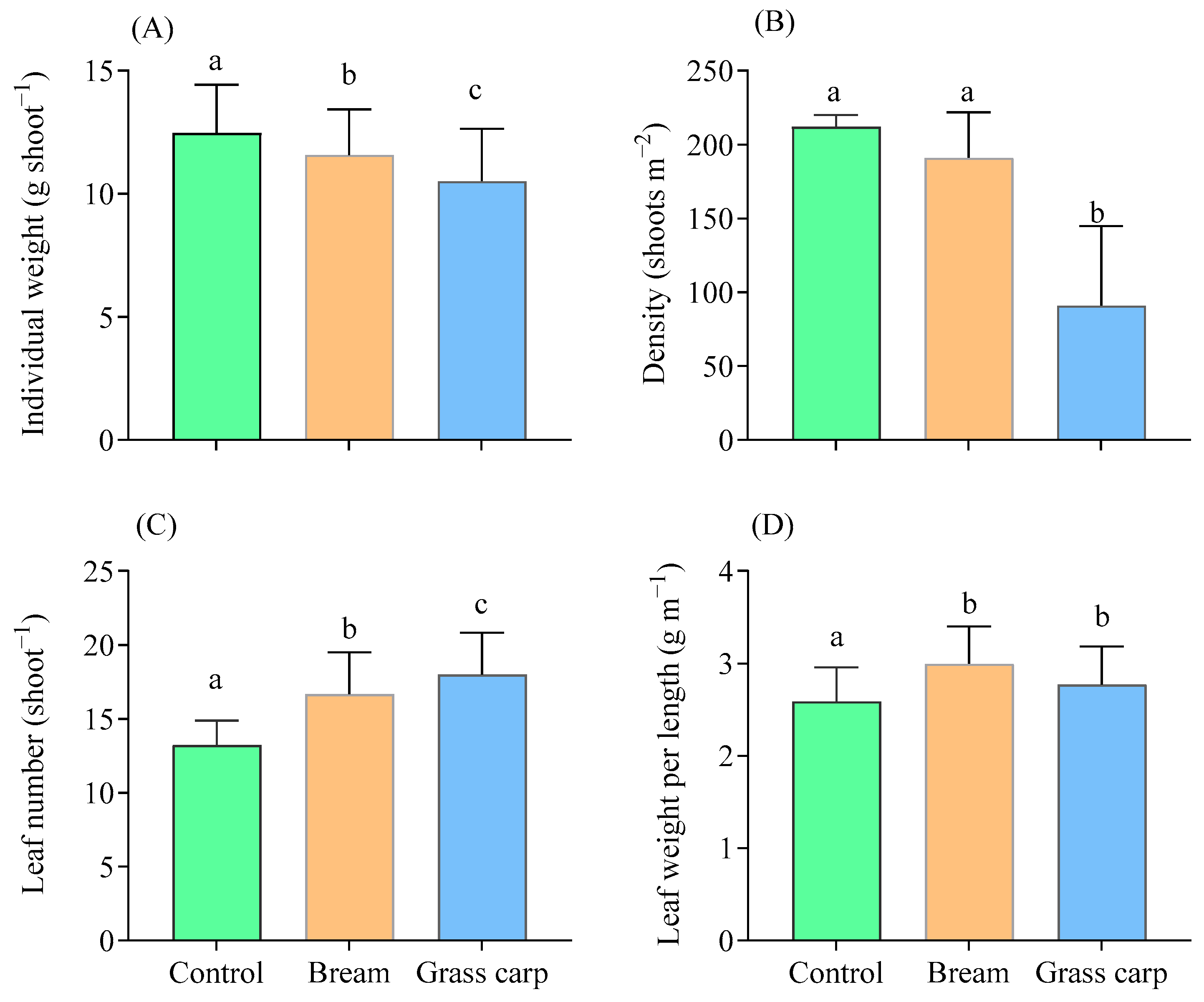

3.3. Biomass Ratio and Traits of the Two Macrophyte Species

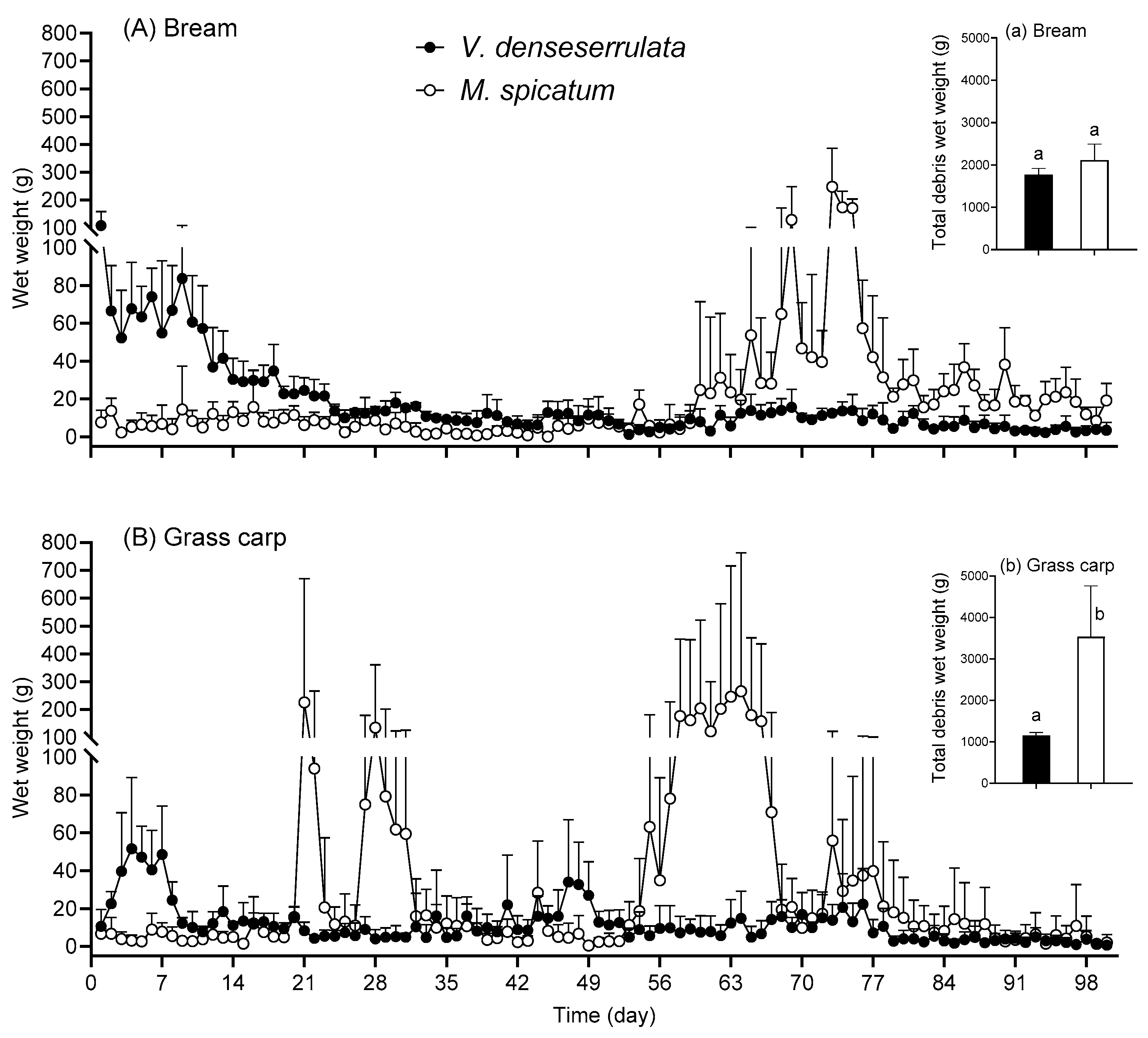

3.4. Debris in Fish Treatments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carpenter, S.R.; Lodge, D.M. Effects of Submersed Macrophytes on Ecosystem Processes. Aquat. Bot. 1986, 26, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, Z.; He, H.; Zhen, W.; Guan, B.; Chen, F.; Li, K.; Zhong, P.; Teixeira-de Mello, F.; Jeppesen, E. Submerged Macrophytes Facilitate Dominance of Omnivorous Fish in a Subtropical Shallow Lake: Implications for Lake Restoration. Hydrobiologia 2016, 775, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhong, P.; Zhang, X.; Ning, J.; Larsen, S.E.; Chen, D.; Gao, Y.; He, H.; Jeppesen, E. Successful Restoration of a Tropical Shallow Eutrophic Lake: Strong Bottom-up but Weak Top-down Effects Recorded. Water Res. 2018, 146, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barko, J.W.; James, W.F. Effects of Submerged Aquatic Macrophytes on Nutrient Dynamics, Sedimentation, and Resuspension. In The Structuring Role of Submerged Macrophytes in Lakes; Jeppesen, E., Søndergaard, M., Søndergaard, M., Christoffersen, K., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 197–214. ISBN 978-1-4612-0695-8. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, S.A.; Shaw, B.H. Ecological Life Histories of the Three Aquatic Nuisance Plants, Myriophyllum spicatum, Potamogeton crispus and Elodea canadensis. Hydrobiologia 1986, 131, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.S.; Barko, J.W. Ecology of Eurasian Watermilfoil. J. Aquat. Plant Manag. 1990, 28, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hilt, S.; Gross, E.M.; Hupfer, M.; Morscheid, H.; Mählmann, J.; Melzer, A.; Poltz, J.; Sandrock, S.; Scharf, E.-M.; Schneider, S.; et al. Restoration of Submerged Vegetation in Shallow Eutrophic Lakes—A Guideline and State of the Art in Germany. Limnologica 2006, 36, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, J.D.; Chambers, P.A.; James, W.F.; Koch, E.W.; Westlake, D.F. The Interaction between Water Movement, Sediment Dynamics and Submersed Macrophytes. Hydrobiologia 2001, 444, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widdows, J.; Pope, N.; Brinsley, M.; Asmus, H.; Asmus, R. Effects of Seagrass Beds (Zostera noltii and Z. marina) on near-Bed Hydrodynamics and Sediment Resuspension. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 358, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganthy, F.; Soissons, L.; Sauriau, P.-G.; Verney, R.; Sottolichio, A. Effects of Short Flexible Seagrass Zostera noltei on Flow, Erosion and Deposition Processes Determined Using Flume Experiments. Sedimentology 2015, 62, 997–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussner, A.; Stiers, I.; Verhofstad, M.J.J.M.; Bakker, E.S.; Grutters, B.M.C.; Haury, J.; van Valkenburg, J.L.C.H.; Brundu, G.; Newman, J.; Clayton, J.S.; et al. Management and Control Methods of Invasive Alien Freshwater Aquatic Plants: A Review. Aquat. Bot. 2017, 136, 112–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titus, J.E.; Adams, M.S. Coexistence and the Comparative Light Relations of the Submersed Macrophytes Myriophyllum spicatum L. and Vallisneria americana Michx. Oecologia 1979, 40, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petr, T. Interactions Between Fish and Aquatic Macrophytes in Inland Waters: A Review; Food & Agriculture Org.: Rome, Italy, 2000; ISBN 978-92-5-104453-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Kelly, A.M. The Public Sector Role in the Establishment of Grass Carp in the United States. Fisheries 2006, 31, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassani, J.R. Problems and Prospects for Grass Carp as a Management Tool. Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. 1995, 15, 407–412. [Google Scholar]

- Bonar, S.A.; Bolding, B.; Divens, M. Effects of Triploid Grass Carp on Aquatic Plants, Water Quality, and Public Satisfaction in Washington State. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2002, 22, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, W.; Zhang, X.; Guan, B.; Yin, C.; Yu, J.; Jeppesen, E.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Z. Stocking of Herbivorous Fish in Eutrophic Shallow Clear-Water Lakes to Reduce Standing Height of Submerged Macrophytes While Maintaining Their Biomass. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 113, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, W.; Li, L.; Wang, B.; Cui, X.; Chen, J.; Song, Z. Divergences in Reproductive Strategy Explain the Distribution Ranges of Vallisneria Species in China. Aquat. Bot. 2016, 132, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhen, W.; Guan, B.; Zhong, P.; Jeppesen, E.; Liu, Z. Dominance of Myriophyllum spicatum in Submerged Macrophyte Communities Associated with Grass Carp. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2016, 417, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, D.M. Herbivory on Freshwater Macrophytes. Aquat. Bot. 1991, 41, 195–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pípalová, I. Initial Impact of Low Stocking Density of Grass Carp on Aquatic Macrophytes. Aquat. Bot. 2002, 73, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorenbosch, M.; Bakker, E.S. Herbivory in Omnivorous Fishes: Effect of Plant Secondary Metabolites and Prey Stoichiometry. Freshw. Biol. 2011, 56, 1783–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, G.D.; Welch, E.B.; Peterson, S.; Nichols, S.A. Restoration and Management of Lakes and Reservoirs, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-429-18923-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dibble, E.; Kovalenko, K. Ecological Impact of Grass Carp: A Review of the Available Data. J. Aquat. Plant Manag. 2009, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Liu, X. Nutrition and Bioenergetics of the Chinese Herbivorous with Important Food Values. III. Preliminary Studies on the Feeding Selectivity of Ctenopharyngodon idella and Megalobrama amblycephala. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 1991, 15, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, A.J.; Dyke, J.M.V.; Hestand, R.S.; Thompson, B.Z. Management of Aquatic Plants in Multi-Use Lakes with Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Lake Reserv. Manag. 1987, 3, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapuscinski, K.L.; Farrell, J.M.; Stehman, S.V.; Boyer, G.L.; Fernando, D.D.; Teece, M.A.; Tschaplinski, T.J. Selective Herbivory by an Invasive Cyprinid, the Rudd Scardinius erythrophthalmus. Freshw. Biol. 2014, 59, 2315–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, W.S. A Biological Study of Magalobrama amblycephala and M. terminalis of Liang-Tse Lake. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 1960, 1, 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Cao, W.; Yi, G.; Yang, G.; Luo, Y. The Cyprinid Fishes of China; Shanghai Science and Technology Press: Shanghai, China, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Su, Z. Nutrition and Bioenergetics of the Chinese Herbivorous with Important Food Values. II. Maximum Consumption and Digestion of Seven Aquatic Plants By Ctenopharyngodon idella and Megalobrama amblycephala. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 1993, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Tu, Q. The Standard Methods for Observation and Analysis in Lake Eutrophication, 2nd ed.; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- The State Environmental Protection Administration. Water and Wastewater Monitoring and Analysis Method, 4th ed.; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Wang, L.; Ma, L.; Min, F.; Huang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; He, F. Factors Affecting Palatability of Four Submerged Macrophytes for Grass Carp Ctenopharyngodon idella. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 28046–28054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umetsu, C.A.; Evangelista, H.B.A.; Thomaz, S.M. The Colonization, Regeneration, and Growth Rates of Macrophytes from Fragments: A Comparison between Exotic and Native Submerged Aquatic Species. Aquat. Ecol. 2012, 46, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhu, L.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, L.; Chen, X.; Deng, Z.; Pan, B. Colonization by Fragments of the Submerged Macrophyte Myriophyllum spicatum under Different Sediment Type and Density Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pípalová, I. A Review of Grass Carp Use for Aquatic Weed Control and Its Impact on Water Bodies. J. Aquat. Plant Manag. 2006, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, D.; Hong, S. The Histology of the Digestive Tract of the Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 1963, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hlckling, C.F. On the Feeding Process in the White Amur, Ctenopharyngodon idella. J. Zool. 1966, 148, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonar, S.A.; Thomas, G.L.; Th1Esfeld, S.L.; Pauley, G.B.; Stables, T.B. Effect of Triploid Grass Carp on the Aquatic Macrophyte Community of Devils Lake, Oregon. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 1993, 13, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Yu, D.; Wu, Z. Differential Effects of Water Depth and Sediment Type on Clonal Growth of the Submersed Macrophyte Vallisneria natans. Hydrobiologia 2007, 589, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimber, A.; Owens, J.L.; Crumpton, W.G. Light Availability and Growth of Wildcelery (Vallisneria americana) in Upper Mississippi River Backwaters. Regul. Rivers Res. Manag. 1995, 11, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, C.D.; Davidson, T.A.; Rawcliffe, R.; Langdon, P.G.; Leavitt, P.R.; Cockerton, G.; Rose, N.L.; Croft, T. Consequences of Fish Kills for Long-Term Trophic Structure in Shallow Lakes: Implications for Theory and Restoration. Ecosystems 2016, 19, 1289–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhen, W.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yang, K.; Guan, B.; Li, K.; Jeppesen, E.; Liu, Z.; et al. Effects of Herbivorous Fish on Competition and Growth of Canopy-Forming and Meadow-Forming Submerged Macrophytes: Implications for Lake Restoration. Water 2026, 18, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010028

Zhen W, Zhang X, Lin Z, Gao Y, Wang Q, Yang K, Guan B, Li K, Jeppesen E, Liu Z, et al. Effects of Herbivorous Fish on Competition and Growth of Canopy-Forming and Meadow-Forming Submerged Macrophytes: Implications for Lake Restoration. Water. 2026; 18(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhen, Wei, Xiumei Zhang, Zhenmei Lin, Yiming Gao, Qianhong Wang, Kai Yang, Baohua Guan, Kuanyi Li, Erik Jeppesen, Zhengwen Liu, and et al. 2026. "Effects of Herbivorous Fish on Competition and Growth of Canopy-Forming and Meadow-Forming Submerged Macrophytes: Implications for Lake Restoration" Water 18, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010028

APA StyleZhen, W., Zhang, X., Lin, Z., Gao, Y., Wang, Q., Yang, K., Guan, B., Li, K., Jeppesen, E., Liu, Z., & Yu, J. (2026). Effects of Herbivorous Fish on Competition and Growth of Canopy-Forming and Meadow-Forming Submerged Macrophytes: Implications for Lake Restoration. Water, 18(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010028