Abstract

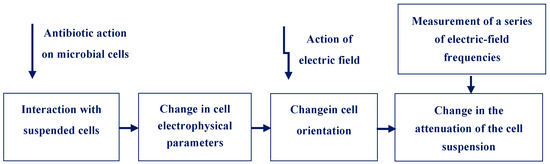

Antibiotics are persistent organic pollutants that pose a serious problem for water resources, ultimately having a detrimental effect on human and animal health. The most important aspect of controlling and preventing the spread of antibiotics and their degradation products is continuous screening and monitoring of environmental samples. Optical sensing technologies represent a large group of sensors that allow short-term detection of antibiotics in non-laboratory settings. This article reviews the advances in optical sensing systems (colorimetric, fluorescent, surface-enhanced Raman spectra-based, surface plasmon resonance-based, localized surface plasmon resonance-based, photonic crystal-based, fiber optic, molecularly imprinted polymer-based and electro-optical platforms) for the detection of antibacterial drugs in water. Special attention is paid to the evaluation of the analytic characteristics of optical sensors for the analysis of antibiotics. Particular attention is paid to electro-optical sensing and to the unique possibility of its use in antibiotic determination. Potential strategies are considered for amplifying the recorded signals and improving the performance of sensor systems. The main trends in optical sensing for antibiotic analysis and the prospects for the commercial application of optical sensors are described.

1. Introduction

Evaluation of pollution of water resources by antibacterial drugs and their metabolic products is vitally important, because it allows monitoring and degradation of toxic substrates and assessment of possible consequences. Today, the entry of antimicrobial drugs into water is almost inevitable. Undoubtedly, drugs have brought and continue to bring strong assistance in the fight against severe infectious diseases, because they prevent pathological processes in animals and contribute to the long-term preservation of food products during transportation, thereby improving the quality of human life [1].

Under environmental influences, antibiotics alter bacterial populations and their activity in sedimentary water, thus affecting biodegradation, nutrient cycling, and water quality. Epidemiological studies have shown that the misuse of antimicrobials can become a serious problem for human health and the environment [2,3]. By disrupting physiological, metabolic, or genetic pathways, toxic substances can kill, temporarily disable, or permanently harm people, animals, and plants. These include insufficient amounts of every chemical, irrespective of where it comes from or how it is made. According to recent research, even brief exposure to certain harmful compounds can result in learning difficulties, cancer, infertility, and other severe health issues [4].

The overuse of antibiotics has led to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant microbes, which can contaminate food, enter the food chain, and ultimately penetrate the human body, in which they can cause a variety of health problems.

Monitoring of antimicrobials at various stages of industrial and processing processes, in effluents and wastewater, and in industrial, agricultural, and urban areas has recently become necessary owing to the growing concerns about the toxicity of these substances to the environment and the food industry. Antibiotics are determined by standard microbiological, analytic, and biosensor methods. Microbiological methods of analysis are historically the first and are still used today to determine the content of antibiotics in biological environments. They are highly sensitive but take much more time. Because their broad specificity does not allow individual antibiotics to be identified, they are used mainly for quality control. Enzymatic methods are fairly fast (analysis time is about 20 min) and are based on the specific inhibition of the activity of certain enzymes in the presence of antibiotics [5,6,7].

The two categories of analytic techniques for antibiotic detection are screening and confirmatory.

- For detection of analyte concentrations, confirmatory techniques use mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography. Another detection method is to combine liquid chromatography with UV or electrophoresis-based techniques.

- The primary purpose of screening is to make semi-quantitative measurements. This method is used because it is less likely to produce false-positive results, simple to use, rapid, affordable, and highly selective [8].

Traditionally, antibiotics are determined by microbiological methods; chromatography, including high-performance liquid chromatography and chromatography–mass spectrometry; stripping voltammetry; electroanalytical determination with modified electrodes; immunological approaches, including the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA); and spectrophotometric, fluorimetric, and chemiluminescent methods. High-performance liquid chromatography, gas chromatography, and mass spectrometry are used widely in the laboratory owing to their high sensitivity and accuracy [9,10]. However, these methods are often limited by complex sample preparation, long analysis times, and expensive equipment, which makes them unsuitable for rapid field studies. Moreover, the environmental risk associated with antibiotic residues primarily depends on their bioavailability (the fraction that can be absorbed by organisms). Only bioavailable antibiotics pose a hazard to organisms and contribute to the spread of resistance. Traditional methods aimed at total extraction may overestimate environmental risks by identifying bioinaccessible fractions. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop rapid, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly detection methods that can specifically measure the bioavailability of antibiotics.

In antibiotic determination, it is often necessary to analyze a fairly large number of samples. To this end, biosensor methods for rapid analysis are being intensely developed. Biosensor systems are highly sensitive and selective, provide rapid results, and can work outside the laboratory. However, biosensors have several limitations associated with both the stability of operation and the sterilization of samples [5,11,12,13,14].

Optical systems that use various types of photodetectors with visual analysis deserve special attention. Despite the variety of available optical methods for the visual determination of antimicrobial drugs in water bodies, general strategies for their application in biosensorics have not been fully reviewed. Here, we provide detailed information on the use of biosensors for antibiotic determination with visual analysis results and we show the prospects for their application in the environmental monitoring of water resources.

2. Antibiotics and Their Role in Environmental Pollution

Antibiotic pollution has become one of the most serious global environmental and public health issues. The irrational use and disposal of antibiotics has led to their widespread penetration into water, soil, and sediments, posing serious risks to human health and ecosystem stability [15,16].

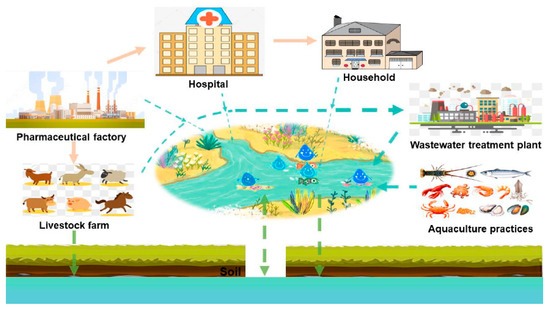

Antibacterial medications and their metabolites are present in ecosystems, particularly in aquatic environments, as a result of the ever-increasing use of antibiotics [17]. Food, groundwater, and even drinking water have been found to contain antibiotic residues and metabolites [16]. Figure 1 shows the primary routes of antibiotic entry into groundwater [18]. Antibiotics are present in aquatic environments at ng/L to μg/L [19].

Figure 1.

Sources of antibiotics in groundwater (Reprinted from [18]. Creative Commons CC-BY license).

The world’s leading consumer of antibiotics is China (about 45% of the world’s total antibiotic consumption). In the United States, antibiotics are widespread in groundwater in most regions of the country. The antimicrobials sulfadiazine and sulfamethazine have been detected in groundwater at up to 360 and 1100 ng/L, respectively [20]. In Europe and Africa, concentrations of some antibiotics exceeded 10 and 50 μg/L, and clarithromycin concentrations in Austrian waters reached 12,000 ng/L. In the Asia-Pacific region, concentrations as high as 450 μg/L have been recorded [21,22].

Mashile et al. [23] presented the dynamics of sulfonamides and β-blockers in African and Asian water bodies for the past five years and showed that sulfonamide concentrations are high in Kenya (13,800 ng/L) and in Vietnam (3508 ng/L).

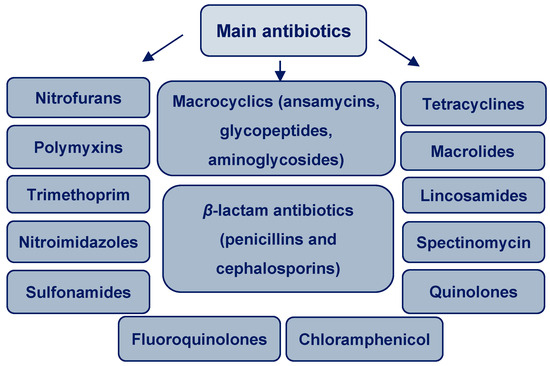

During comprehensive 2-year monitoring (2015 and 2016), 17 of the 53 antibiotics analyzed were detected at least once in wastewater treatment plants in 7 European countries (Portugal, Spain, Ireland, Cyprus, Germany, Finland, and Norway). Figure 2 shows the main groups of antibiotics.

Figure 2.

Main groups of antibiotics.

The different antimicrobials that belong to these groups include cephalexin, clindamycin, metronidazole, ampicillin, tetracycline, enrofloxacin, ofloxacin, orbifloxacin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, sulfapyridine, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, nalidixic acid, pipemidic acid, oxolinic acid, cephalexin, clindamycin, ampicillin, and tetracycline. The northern nations (Norway, Finland, and Germany) and Cyprus had low overall antibiotic concentrations in wastewater, whereas Ireland and the southern nations (Portugal and Spain) had the highest average values. Three antibiotics—ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, and cephalexin—were proposed as indicators of antibiotic pollution, because they occasionally endanger the environment [24].

On the basis of 10-year research, Zeng et al. [18] identified 47 types of antibiotics (mainly fluoroquinolones and sulfonamides) that harm the biological environment of ground water and induce the production of resistance genes. Also discussed were the origins, migration, and transformation of antibiotics, pollution levels, and potential hazards to the biological environment in groundwater systems.

Twenty most commonly used antibiotics, including tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides, and macrolides, were found at 212–4035 ng/L in reclaimed water and at 19–1270 ng/L in groundwater, according to the data from a nationwide survey on water pollution assessment in China (in various humid, semi-humid, and semi-arid regions) [25].

Of particular concern is the development of antibiotic resistance in microbial cells, which can be triggered by even sublethal drug concentrations in the environment. The rapidly evolving antibiotic resistance is becoming a global crisis, because the range of microbial resistance to antibiotics in clinical settings expands and possibilities of developing new antibiotics are reduced [26,27,28,29]. At less than 10 g/L, some antibiotics present in surface waters affect microbial cells. Antibiotics (such as ciprofloxacin) that are most prevalent in streams and rivers at these quantities are the strongest. Although prokaryotes may not be killed by sublethal quantities, laboratory investigations have shown that they can change the makeup of single-cell communities and boost bacterial resistance [21].

Antibiotics are often found in surface water and wastewater, usually at 0.01 to 1.0 µg/L [30]. They may persist for several months and cannot be completely removed by traditional disinfection technologies during water purification for drinking water. Relatively little information is available on the antibiotic content of drinking water. Quinolones, chloramphenicols, sulfonamides, and macrolides appear the main antibiotics present at high concentrations in drinking water, with the highest concentration being that of ciprofloxacin (up to 679.7 ng/L) [31].

The overuse and abuse of antibiotics leads to life-threatening consequences in the human body, including allergies, hepatotoxicity, blood disorders, kidney toxicity, nerve toxicity, hearing loss, and increased skin sensitivity [32]. Most antibiotics are excreted as parent drugs or metabolites in feces or urine. On entering the environment, they contribute to soil and water pollution owing to their complex molecular composition. Antibiotic pollution is exacerbated by waste from pharmaceutical factories, hospitals, and livestock farms. Antibiotic residues in water sources and the environment strongly contribute to the development of resistance in certain microorganisms. Moreover, excessive antibiotic residues in water sources pose serious threats to human health, which include childhood obesity, gastrointestinal and reproductive disorders, bone marrow toxicity, mutagenicity, anaphylactic shock, and cancer [33].

The main consequences of infection with antibiotic-resistant bacteria are: increased duration of illness, increased risk of mortality or invasiveness of the disease, and increased healthcare costs [34,35].

Direct contact with animal blood, saliva, milk, semen, feces, or urine can spread antimicrobial resistance across the food chain. A more complicated method of transmission is indirect contact, which occurs when contaminated eggs, meat, and dairy products are consumed. It is crucial to keep in mind that food trade, foreign travel, and population increase can all contribute to the global spread of antimicrobial resistance through the food chain. When meat, vegetables, and fish are cooked in a variety of bacterial conditions, large amounts of antibiotics are employed. Additionally, this causes resistant bacteria to arise [36].

Owing to concerns about the development of antibiotic resistance, the use of antibiotics in animal feed as growth promoters is banned in the European Union. Therefore, food producers use biocides to control and remove colonies of microorganisms that cause spoilage and disease [37].

The ranking list of bacterial pathogens and their population risk were revised by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2024 [38]. Antibiotic resistance is predicted to overtake all other causes of death in humans by 2050 if prompt action is not taken. The population-weighted average use of systemic antibiotics in the European Union (EU) in 2023 (community and hospital sectors combined) increased by 1% over 2019. In 2023, the EU’s population-weighted average consumption share of WHO Access antibiotics was 61.5% (country range, 41.7–75.1%), which was 3.5% below the 2030 target of over 65% and 0.4% higher than in 2019. The need to increase efforts to stop the overuse and misuse of antibiotics at all levels of healthcare is highlighted by the continuous increase in the use of WHO reserve and broad-spectrum antibiotics [22]. One of the tactics used to prevent the spread of antibiotics in the environment and reduce antibiotic resistance is the global monitoring and detection of antibiotics in the environment, especially in water resources.

Food and drinking water safety is a critical aspect of the food supply chain, as it determines the quality of the final product and, consequently, its acceptance by consumers. The Food Safety Management Program adopts a new strategy for food safety that takes into account every facet of food processing. Accidental or inadvertent microbiological or chemical contamination of a product during the production process is a typical contamination risk. However, the prospect of adulteration or purposeful contamination, which is more difficult to detect, is usually not taken into account by food and drinking water safety procedures. Antibiotic residues in food are becoming a major risk and an illustration of food fraud. They have been discovered in processed foods that are openly sold on the market as well as in a number of common products, most of which are derived from animals.

Antibiotic residues in food have become a serious hazard and an example of food fraud. Antibiotic residues are present in several everyday products, primarily of animal origin, and have also been found in processed foods sold openly on the market [39]. Therefore, research is active into antibiotic determining methods.

The effective monitoring of antibiotic concentrations requires rapid, accurate, and reliable detection methods. These needs are met by sensor systems such as optical biosensors, which will be covered in what follows.

3. Biosensors for Antibiotic Detection

Antibiotics can be successfully analyzed by biosensor techniques. Biosensors are analytic instruments based on a biological sensing element (bioreceptor) complexed with a physical transducer [40,41,42,43,44,45].

The first biosensor was developed in 1950 by the American biochemist L.L. Clark and is the most well-known example of a commercial biosensor that is still in use for detecting blood oxygen levels (a Clark electrode, or oxygen electrode). This blood glucose biosensor breaks down blood glucose by using the glucose oxidase enzyme. The primary phases of development of the many generations of biosensors currently available on the market are described in [46].

In the first kind of biosensor, glucose oxidation leads to an electric reaction. For a better response, the second type of sensor incorporates specific buffers between the sensor and the reaction. In the third form, there is no middleman engaged; instead, the sensor alone initiates a reaction. With the introduction of groundbreaking technology in the late 1980s, biosensors saw a surge in popularity. Third- and fourth-generation sensors emerged as a result, enabling real-time monitoring of human physiological indicators [46].

With the development of modern technologies, no-label biosensors become increasingly widespread, thanks to which it is possible to screen for interactions with the substrate and obtain information on the presence of antibiotics in the sample being studied [47,48]. This type of sensor has only one sensitive component, and this greatly simplifies the analysis scheme and reduces the time of research. Such systems decrease the economic costs of research by reducing the number of necessary reagents, and they allow quantitative measurements in real time [49,50].

Optical, (piezo)electric, and (micro)mechanical transducers hold promise for the label-free detection of the interaction of a sensor component with the substrate being analyzed. The use of these transducers is supplemented by methods based on the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [50], surface Raman spectroscopy (SERS) [51,52,53], quartz crystal microbalance [54], and micro cantilever sensors [50,55]. In what follows, we discuss the main optical sensor systems for antibiotic detection.

4. Optical Sensor Systems for Antibiotic Detection

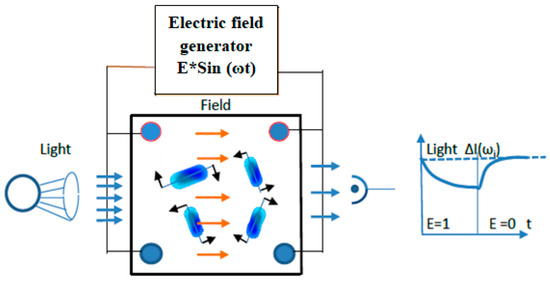

Optical sensors use the optical concept of signal measurement by transforming light beams into electric signals. They determine the actual light level and transform it into a format that the device can understand. A light source, a measuring device, and an optical sensor are the usual components of an optical sensor. The sensor is often connected to an electric trigger that responds to signal changes in the sensor. The light sensor functions as a photoelectric trigger, increasing or lowering the electric output signal in response to a change. Signals in fiber optic cables or integrated optical circuits can be selectively switched between circuits thanks to an optical switch. In addition to electro-optical and magneto-optical effects, an optical switch can also function mechanically.

In optical biosensors, the analytic signal is not caused by the chemical interaction of the component being determined with the sensitive element. Instead, it is caused by the measured physical variables, including the intensity of absorption and reflection of light, the intensity of luminescence of the object, and other variables. The fundamental phenomena underlying the operation of optical sensors with visual recording of results are as follows:

- Absorption (the ability of a substance to absorb optical radiation).

- Reflection (when a light flux falls on the interface between two media, and part of its radiation is reflected back).

- Luminescence (the glow of a substance that occurs after it absorbs excitation energy, which is excess radiation, as compared with the thermal radiation of the body at a given temperature).

- Photoluminescence (the emission of photons by a substance that occurs when the substance is excited by electromagnetic radiation in the ultraviolet, visible, and infrared wavelength ranges).

Photoluminescence is characterized by absorption and luminescence spectra, polarization, energy yield (the ratio of the energy emitted by a substance in the form of luminescence to the absorbed energy), quantum yield (the ratio of the number of emitted quanta to the number of absorbed ones), and kinetics [56,57].

The basic idea behind optical biosensors is that the crosstalk between the analyte and receptor molecules on the substrate surface alters optical characteristics such as absorption, reflection, transmission, fluorescence, and scattering. The light output signal can be used for quantitative analysis and detection of the target pathogen. The sensitivity of optical devices is achieved through labeling or label-free methods. The label-free approach means that the analyte simply interacts with the transducer’s surface to facilitate signal detection; by contrast, the label-based approach uses special optical tags to label the target analyte, generating various optical phenomena to produce a subsequent signal. These two approaches are used widely in optical biosensing to convey information about the interaction between the biosensor’s element and the target and highlight the versatility of optical biosensors, as compared with alternative platforms. Optical biosensors are generally classified into colorimetric, fluorescent, surface-enhanced Raman spectra (SERS)-based, surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based [58], localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR)-based, photonic crystal-based, fiber optic, molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP)-based, and electro-optical. We now shift to discuss how all these sensors can be useful in antibiotic detection.

4.1. Colorimetric Optical Sensors

Colorimetric sensing is a quantitative method based on the relationship between the color change of a solution and the content of a target object. Colorimetric detection uses special indicators (nanozymes or nanomaterials) that change color when interacting with the molecules of interest. The color information can be recorded by the device, and the resulting signal can be processed by an image processor to obtain final images [59].

In sensors designed for antibiotic detection, the most important factor regulating color changes is the presence or absence of the target analyte in the sample. Colorimetric measurements typically track the change in attenuation caused by a change in the analyte concentration at a specific wavelength. The principle of antigen–antibody interaction is used widely in sensor systems for antibiotic detection [60]. Importantly, the type and quality of enzymes will have a certain effect on the detection efficacy of the biosensor [61,62,63].

Colorimetric and optical biosensors are often combined, which expands their application in environmental monitoring, food safety, biomedicine, and clinical diagnostics [64,65]. Recently, colorimetric methods for the determination of antibiotics have attracted increasing research attention owing to such characteristics as naked-eye recognition, absence of need for modern instruments, ease of use, short analysis time, and low cost [66].

In some antibiotic-detecting platforms, various types of colorimetric reagents are used, including metal nanoparticles, visible dyes, enzymes, and metal ions [67,68]. Such platforms, combining d-amino acid-modified gold nanoparticles with antibiotics, can be used to examine the sensitivity of psychrophilic bacteria to antimicrobials and select antibiotic treatment [69].

In another study, kanamycin and its derivatives (kanamycin B and tobramycin) were detected with a single-stranded DNA aptamer and gold nanoparticles [70]. Table 1 summarizes the main achievements of colorimetric sensors in antibiotic detection.

Table 1.

Main colorimetric sensors for antibiotic detection.

Nanozymes, as artificial enzymes, are commonly used as receptor components of antibiotic-detecting colorimetric sensor systems [10]. Nanozyme sensors have been used for the colorimetric determination of ampicillin [71,72], tetracycline [73,74], enrofloxacin [75], kanamycin [76,77,78,79], norfloxacin [80], and neomycin [81].

Iron-based nanozymes doped with iron ions (e-doping) were used to make a simple multichannel colorimetric sensor array for the identification and detection of quinolone antibiotics [82].

Cobalt(II) 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(4-carboxylpheyl)porphyrin (CoTCPP) self-assembled nanoaggregates served as soft templates for the preparation of TiO2-based nanozymes with enhanced peroxidase-like activity. The sensing platform was tuned by light illumination to measure H2O2 and amikacin in lake water (straight forward and practical colorimetric sensor platform) [83].

Another study showed the potential of nanozymes for tetracycline detection [84]. A colorimetric biosensor with a dual catalytic system consisting of a nanoenzyme and G-quadruplex/hemin DNAzyme was constructed for ultra-sensitive detection of tetracyclines [85].

The promise was shown of innovative multifunctional catalysts by depositing α-Fe2O3 quantum dots (QDs) on titanium silicalite-1 and creating artificial nanozymes capable of simultaneously detecting, adsorbing, and photodegrading tetracyclines in water (19.7 μg/L for oxytetracycline, 23.1 μg/L for doxycycline, and 35.9 μg/L for tetracycline) [86]. The peroxidase-mimicking activity of the nanozyme was enhanced by tetracyclines and caused a visible color change in 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine. The artificial nanozyme showed exceptional adsorption properties and photocatalytic activity under sunlight, achieving an overall removal rate of about 70%.

Gold nanoparticles stand out among other metal-based preparations because of their special optical, electric, and catalytic qualities. These characteristics help create a microenvironment that is conducive to the immobilization of biomolecules while preserving their biological activity, thereby prolonging the biosensor’s lifespan [68,97]. Colorimetric sensor systems using gold nanoparticles have been helpful in detecting streptomycin [87], sulfadimethoxine [88], tetracycline [89,90], and oxytetracycline [91].

A simple, rapid, and ultra-sensitive colorimetric chemosensor was developed for the simultaneous detection of moxifloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and Cr(III). It is based on the aggregation of ammonium thioglycolate (ATG)-functionalized gold nanoparticles (ATG-AuNPs) [92].

High porosity, large surface areas, and structural tenability are characteristics of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), which are made up of metal ions or clusters connected by organic ligands. Therefore they are very promising for use in antibiotic-detecting sensors. Through processes such as electrochemical redox reactions, colorimetric responses via peroxidase-like activity, and fluorescence quenching, MOF-based sensors provide quick, portable, and extremely selective detection. The construction of fluorescent and colorimetric sensors reflects this. MOF-based colorimetric sensors are especially appealing for field research, because they offer an instrument-free, visual approach to antibiotic identification [98,99]. MOF-based colorimetric approaches to antibiotic detection remain understudied, because most MOFs are inherently fluorescent and hence are used primarily through fluorescence quenching mechanisms. Comparatively few MOF-based colorimetric sensors for antibiotic detection have been described in [98].

Examples of MOF-based colorimetric sensors for antibiotic detection have been summarized in [100]. Such sensors have been used to detect tetracycline [93], streptomycin [94], chloramphenicol, oxytetracycline, tetracycline, ampicillin [95], and norfloxacin [96].

The main advantages of colorimetric analysis include ease of use, rapidity of measurement, equipment availability, and ability to analyze low concentrations of antibiotics. Disadvantages include lower accuracy, as compared with that of other methods; the influence of a number of factors on the analysis results; the subjectivity of visual methods, whose accuracy depends on the researcher’s experience; and the need to prepare a series of standard solutions, which makes the analysis more lengthy and costly.

Colorimetry allows visual identification of detection results with the naked eye, but disadvantages such as the low sensitivity and the high background signal limit the scope of its application.

However, the complex composition of various samples and the low concentrations of analytes require additional developments for the application of colorimetric sensor systems, the main ones being those that detect antibiotics at the point of analysis in real time. These include colorimetric sensors on paper, colorimetric detection sensors based on portable smartphones, dual-mode colorimetric sensors, and colorimetric sensors with a dual response [65,101]. A separate R&D area is the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning into colorimetric biosensors, including their potential for technological progress in the near future [102].

4.2. Fluorescence-Based Optical Sensors

Fluorescence is a process characterized by a very brief period of radiation attenuation after turning off the excitation source. This is the short-term absorption of a quantum of light by a fluorophore (a substance that can fluoresce), followed by the rapid emission of another quantum with properties different from the original. Fluorescence is based on the principle that molecules emit light differently, depending on their state [103].

Fluorescence methods are based on changes in the fluorescence intensity, wavelength, or lifetimes that are caused by the interaction of target analytes with sensitive materials. Fluorescence probing methods are based on changes in the fluorescence spectrum caused by contact between probe and detector.

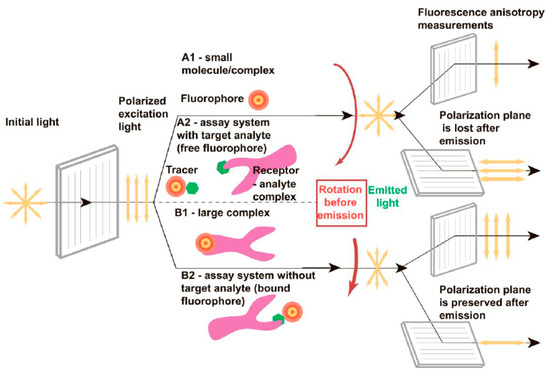

Fluorophore-containing reagent interactions can be easily and quickly recorded by excitation with plane-polarized light and measurement of the degree of polarization of the light emitted (Figure 3 [104]).

Figure 3.

Effect of rotating motion on the anisotropy of fluorescence released after plane-polarized light stimulation (fast rotation is A1 and A2, and slow rotation is B1 and B2) (Reprinted from [104]. Creative Commons CC-BY license).

The polarization plane of the exciting light is not maintained during emission, because the fluorophore or the complex containing it rotates chaotically in solutions owing to Brownian motion. The degree of depolarization can be estimated by measuring emission in planes parallel and perpendicular to the stimulation plane. The emitting light loses the polarization of the exciting light when the fluorophore-containing complex becomes more mobile in the solution (Figure 3, A1). The complex’s spin slows down and the polarization of the light it emits increases when a tiny fluorophore binds to a big compound (Figure 3, B1) [104].

Scientists can determine how much of the fluorescent chemical is present in a sample by measuring the light released. Additional advantages of fluorescence sensing over conventional detection techniques include excellent sensitivity and speed in identifying antibiotics at a comparatively low cost. Fluorescence sensors are beneficial in bioanalysis, because they operate on well-defined principles and are unaffected by suspended particles or by the sample solution color. Therefore, combining the principles of colorimetric and fluorescence methods will highlight the advantages of each method to better adapt to various complex detection requirements to achieve highly sensitive detection [58].

However, most fluorescence-based methods require continuous excitation by an external light source to obtain a fluorescence signal. They are, therefore, susceptible to interference from autofluorescence of the sample matrix, which seriously affects the detection accuracy [104]. Compared with colorimetric methods, fluorescence-based methods show a relative advantage in terms of very high sensitivity [105,106].

For example, tetracycline contains hydroxyl and carbonyl groups in its structure, which can form coordination compounds with metal ions [107].

Tetracycline has very weak fluorescence, but when coordinated with certain metal ions (such as Ca2+, Mg2+ and Zn2+), it shows intense green luminescence [108]. For example, when tetracycline is combined with Eu3+, the color of the fluorescence changes to red [109].

The advent of nanoparticles and the advancement of nanotechnology have led to their active application in analytic measurements. QDs are nanoparticles with sizes similar to the electron wavelength (1–10 nm). By altering their size, it is simple to change their fluorescence or their absorption wavelength. QDs have favorable fluorescence properties, including a long luminescence duration, a high fluorescence intensity, and an adjustable emission wavelength [110].

Therefore, QDs are more suitable for use as fluorescent markers than organic dyes. Antibiotic concentrations in samples can be ascertained by measuring variations in the fluorescence intensity of QDs, which bind to immunorecognition materials. Specific molecules including DNA, enzymes, antibodies, and antigens might be considered active biomolecules. The principle of antigen–antibody interaction is actively used to develop optical sensor systems, particularly fluorescence immunoassays. A multiplex enzyme immunoassay sensor in a “lab-on-a-chip” format was described for the detection of antibiotics (sulfonamides, fluoroquinolones, and tetracyclines) [111]. It is based on a sensitive optical sensor and a polymer self-contained microfluidic cartridge. Pre-filled microfluidic cartridges were used as binary rapid tests for the simultaneous detection of antibiotics in raw milk [111].

Sulfamethazine (SM2) in chicken muscle tissue can be detected with an indirect competitive fluorescence immunoassay (cFLISA), by using QDs as a fluorescent marker connected to a secondary antibody [112].

A fluorescent sensitive probe based on Cr(III)–metal–organic framework (MOF) was designed for the rapid detection of tetracycline (response time, 1 min). When tetracycline is added, the blue emission at λem 410 nm changes owing to the interaction of the antibiotic with the Cr(III)–MOF material [113]. Table 2 summarizes the main achievements of fluorescence-and luminescence-based sensors in antibiotic detection.

Table 2.

Main fluorescence and luminescence-based sensors for antibiotic detection.

In another study, an immune complex was formed, with avidin as a bridge to link QDs coated with biotinylated denatured bovine serum albumin and antibodies. This complex was used to simultaneously detect five chemical residues in porcine muscle tissue [114]. Similar studies were conducted in [115].

Other studies have used antibodies that are specific not only to a particular antibiotic but to an entire class of antimicrobial drugs. Zhu et al. [116] used two types of antibodies for the simultaneous detection of six types of sulfanilamide antibiotics and eleven types of fluoroquinolone antibiotics.

Double-stranded DNA is used as an antibiotic aptamer, one of whose strands can identify chloramphenicol in milk. First, QDs bind to the double-stranded DNA antibody and then contact the double-stranded DNA. Thus, the recognition of antigens and antibodies causes the QDs carrying double-stranded DNA antibodies to assemble with one another, and the fluorescence intensity of the QDs weakens. However, when the antibiotic is added, the recognition of antigens and antibodies causes the QDs carrying double-stranded DNA antibodies to assemble with one another, and the fluorescence intensity of the QDs weakens [117].

A sensor for the detection of streptomycin in milk was made by combining single-stranded DNA, capable of recognizing antibiotics, with a protein. The resulting sensitivity was higher than that of the SPR method [118].

He et al. [119] took a different approach to detecting sulfamethazine residues in milk. It is based on a fluorescent QD immunoassay in which graphene oxide QDs are labeled with an aptamer to sulfamethazine.

Combining fluorescence with aptamers to make aptasensors is common owing to the excellent sensitivity and selectivity of the assay. Taghdisi et al. [120] detected streptomycin in milk and serum on the basis of exonuclease III, SYBR Gold, and an aptamer’s complementary strand. In the absence of the antibiotic, the fluorescence intensity waslow, but when it was added, the aptamer bound to the target, which led to a high fluorescence intensity. In Wu et al. [121], a fluorescent biosensor with aptamer-conjugated magnetic nanoparticles was used to detect low chloramphenicol concentrations.

More than 10 years ago, an approach was proposed based on elucidating the effect of antibiotics on bacteria by cell staining followed by cell examination by fluorescence microscopy [142]. This approach was tested on Escherichia coli cells and is still used in the scientific community [143]. The essence of the method is to compare the cytological profiles of the compounds under study with the profiles obtained for bacteria under the influence of known antibiotics. Another study described a quantitative method of time-lapse fluorescence imaging, called dynamic bacterial morphology imaging (DBMI) [144].

In bacterial imaging, the main direction in fluorescence imaging is to improve image quality by image-processing methods. For example, a system of phenotypic screening at minimal doses was proposed that uses cytological profiling and machine learning. The system allows identification of weak antibacterial effects, improving image quality [145,146]. Further application of artificial intelligence methods may be a promising direction for future developments.

The red-emitting Ru(bpy)3+ acts as a steady red fluorescence backdrop in a fluorescence sensor system that uses a lanthanide organic framework (Tb@COF-Ru) as a receptor component with imaging capacity for the detection of fluoroquinolone antibiotics. The green fluorescence of Tb3+ grew progressively as the concentration of norfloxacin increased, which ultimately resulted in a multicolor fluorescence shift from red to green [122].

A ratiometric fluorescence sensor based on lanthanide-functionalized MOFs (Ag+/Eu3+@UiO-66(COOH)2, AEUC) with intrinsic dual-emission bands was fabricated for the determination of tetracycline residues. (UiO-66-(COOH)2, UC) was used as the reference units, Eu3+ was used as the recognition units, and Ag+ was used as the fluorescence enhancer [123], with conspicuous fluorescence color gradation from red to blue. Ratiometric fluorescent detection of norfloxacin was described in [124].

In bioanalytical assays, the color tonality, which is established by own fluorescent MOFs, is quite desirable. Strong blue emission at 440 nm was achieved by synthesizing ultra-small, extremely fluorescent zinc-containing MOFs (FMOF-5) that were excited at 350 nm. With a notable boost owing to aggregation-induced emission, tetracycline specifically adjusted the blue emission of FMOF-5 to greenish-yellow emission (520 nm). Tetracycline was analyzed fluorimetrically by using F520/F440 ratiometric peak intensities, with a 5 nM detection limit. A smartphone with a detection limit of 10 nM and an integrated ratiometric visual platform was made for point-of-care quantitative analysis based on color tonality [125]. In fluorescence analysis, a TbMOF probe was developed for the determination of tetracycline by using a simple one-step hydrothermal assay. The probe was characterized by a fast response (2 min) and recyclable luminescence sensing during antibiotic detection [147].

The modern level of antibiotic analysis includes polarization fluoroimmunological analysis, which allows results to be obtained immediately after addition of the sample to the immunochemical reagent. The method is based on the competitive binding of the antigen with specific antibodies and the antigen labeled with a fluorescent label (tracer). Polarization of the tracer’s fluorescence is of little importance, and when the tracer binds to the antibody molecule, the polarization of the fluorescence of such a complex increases sharply. This effect is observed only for low-molecular-weight compounds (e.g., antibiotics). The magnitude of fluorescence polarization in the reaction mixture reflects the ratio of the bound and free fractions of the tracer and decreases when an unlabeled antigen is introduced into the medium [148]. Of note, it is possible touse QDs as labels in polarization fluorescence immunoassay (PFIA) to determine aminoglycoside antibiotics (amikacin, streptomycin, and gentamicin) in dairy products [126].

Nitrogen-doped carbon dots showed favorable photostability, serving as a multifunctional nanosensor for the detection of three tetracycline antibiotics based on a dual-mode fluorescence sensing strategy [127].

The fluorescence response (both enhancement and quenching) results from either energy transfer or absorption overlap between the MOF and the target antibiotic [149], as shown in fluorescent sensor systems for the determination of ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol [128]; norfloxacin and minocycline [129]; nitrofurans, nitroimidazoles, and sulfamethoxazole [130]; oxytetracycline and tetracycline [131]; tetracycline, chlorotetracycline, and oxytetracycline [132]; and doxycycline [133].

A separate application of fluorescence methods is to combine them with colorimetric methods. A dual-mode colorimetric and fluorescence strategy was developed by integrating two optical components into the sensor [134]. This minimized environmental influences and potential errors and, when integrated with smart devices (smartphones), facilitated rapid detection of analytes, as shown with tetracyclines [135].

A similar approach to tetracycline determination on the basis of dual-mode colorimetric and fluorescent signals was proposed by Yang et al. [136]. The authors were able to control the tetracycline content in actual samples (drinking water and milk with added antibiotics). The same dual approach was proposed for oxytetracycline detection [137].

The main strong points of fluorescence-based sensors are high sensitivity, good selectivity, and ability to distinguish between the parameters of many fluorescent substances. Weak points are as follows: many substances do not fluoresce; there are many interfering factors (photolysis, oxygen quenching, and light contamination); the chromophore’s fluorescence intensity depends on pH; and there is no relationship between fluorescence and structure of a compound.

Luminescence is the glow of a substance that occurs after it absorbs excitation energy and is excess radiation, as compared with the thermal radiation of the body at a given temperature. Photoluminescence, whose source is light, is of greatest importance for determining the composition of the medium. Photoluminescence is characterized by absorption and luminescence spectra, polarization, energy yield (the ratio of the energy emitted by the substance in the form of luminescence to the absorbed energy), quantum yield (the ratio of the number of emitted quanta to the number of absorbed ones) and kinetics. The most widely used analysis is based on photoluminescence excited by UV radiation, whose source is mercury-quartz and xenon lamps and also lasers. Luminescence is recorded visually and photoelectrically (with a spectrophotometer). Photoluminescence characteristics allow conclusions to be drawn about the presence of certain substances in the samples under study and their concentration. Quantitative analysis is based on the dependence of luminescence intensity on the amount of the luminescent substance [62,63].

The development of extremely accurate and sensitive fluorescence chemosensors for antibiotic monitoring must be mentioned separately. A chemical of abiotic origin that reversibly forms a complex with an analyte and transmits a fluorescence signal along with it was the initial definition of a fluorescent chemosensor. These days, the terms “fluorescent probe” and “probe” are used interchangeably; that is, a probe/chemosensor is any chemical that has a binding/reactive site, a luminophore, and the mechanism of interaction between these two sites. This guarantees that following the probe’s interaction with the target analyte, a measurable result will be obtained. The primary advancements in the creation of these sensor systems were detailed in [150,151].

Fluorescent systems often generate a colorimetric response in addition to the fluorescence output. This is because a change in UV absorption (color) usually correlates with a change in fluorescence emission for any chemosensor. Notwithstanding these achievements, major technological advancements are still needed to address existing problems in this industry. These include: (1) increasing the signal-to-noise ratio to make it easier to obtain a measurable signal; (2) modifying the chemosensor’s solubility and output wavelength to ensure optimal compatibility across a range of applications; and (3) increasing the sensitivity and selectivity to the analyte to increase the accuracy of chemosensors for any desired purpose [150].

Chemi- and bioluminescence-based sensors record light radiation at different wavelengths that is emitted by enzymatic-reaction products in an excited state. These sensors are extremely sensitive and allow femtomolar quantities of a substance to be determined. The last decade of the 20th century saw intense development of a new group of luminescent sensors, using “luminescent markers” (specially synthesized macromolecules including two important functional links). One of them has a pronounced luminescent activity; i.e., it glows brightly under the influence of exciting light (or another exciting factor; this link is called a reporter). The other link is made selectively sensitive to the analyte—the chemical or biochemical substance whose presence must be detected and its concentration determined. This link is called a recognition element. Molecules of natural biochemical enzymes (enzymes, nanozymes) are often used for this purpose. But specially synthesized recognition molecules are also used. These two connections work together as a macromolecule, such that when a particle of the regulated analyte attaches to the recognizer, the luminescence of the signaling device is either quenched or, on the other hand, stimulated. On the basis of changes in luminescence intensity, the sensor ascertains the analyte’s presence and concentration or the properties of a certain external factor.

The relationship between luminescent radiation intensity and light emission wavelength is known as the luminescence spectrum. The most basic are atomic spectra, in which the atom’s electron structure alone determines the aforementioned dependence. Because different valence vibrations and deformations are achieved in molecules, their spectra are considerably more complex. Fluorophores with aggregation-enhanced emission (aggregation-induced emission luminogens) are also used as luminescent agents in nanozyme-based sensors. The advantage of such materials is the ability to control their photophysical properties by introducing oxidants into the system and changing the solvent’s polarity. An example is tetraphenylethylene [152].

An aptamer was transformed from a randomly coiled structure into a particular shape with a hairpin region in a luminous technique based on oligonucleotides for the detection of kanamycin in aqueous solution [138].

A fluorescent chemosensor based on lanthanide MOFs was proposed for the visual determination of oxytetracycline and doxycycline in milk, beef, and pork by using a smartphone [139]. Virolainen et al. [140] described a luminescent biosensor for the rapid determination of residual amounts of tetracycline. The sensor is based on E. coli cells that can be stored in lyophilized form and can self-bioluminesce upon recognition of tetracycline.

For ciprofloxacin detection in whole milk, the LumiCellSense (LCS) smartphone-based whole-cell biosensor was proposed [141] that consists of a 16-well biochip with an oxygen-permeable covering and bioluminescent E. coli cells attached to the sensor surface.

Of note, luminescent sensors often have higher sensitivity than colorimetric ones because of their lower background signal. Colorimetric and luminescent sensor systems for antibiotic detection, as shown in the presented examples, have great potential for further development, becausein colorimetric sensors, visible color changes occur owing to changes in the plasmon resonance frequency of metal nanoparticles, and these changes are visually observable with the naked eye. Given the simplicity of the analytic method and the interpretation of results for antibiotic detection, further development in this area is expected.

4.3. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)-Based and Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR)-Based Sensors

Among the various sensor technologies, sensors based on the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) and the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) stand out as systems ensuring accurate, real-time detection of low concentrations of antibiotics [153].

The SPR is the basis for optical biosensors that alter the direction of light flux propagation through an optical fiber or a triangular prism covered in a thin metal sheet [154,155]. The basic operating principle of SPR-based sensors is to detect changes in the refractive index of the chip surface during immunological recognition. A layer of immunorecognition material located outside the SPR chip (antibodies, antigens, enzymes, and molecularly imprinted films) can increase the specificity and sensitivity of the sensors [156].

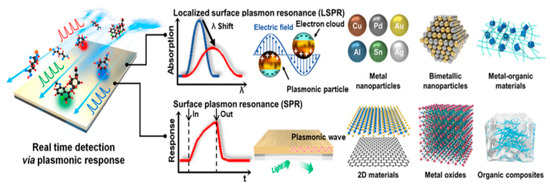

LSPR sensors rely on the size and shape of nanoparticles, whereas SPR sensors rely on reactions with chemicals. Figure 4 shows a scheme for the two typical technologies (LSPR and SPR) used in real-time analysis [153].

Figure 4.

LSPR and SPR detection technologies and the materials used for each technology (Reprinted from [153]. Creative Commons CC BY-NC 3.0).

The food sector frequently uses SPR-based biosensors to identify and measure antibacterial or antimicrobial substances. The SPR is used about 2.5 times more often than any other optical biosensing technique. The SPR is the recommended option because of its great sensitivity, high throughput, dependability, and affordability.

Using competitive inhibition for immobilization on an SPR chip allows a high SPR signal intensity at low concentrations and a lower detection limit for antibiotics, as shown for β-lactams in milk. With this approach, the antibiotic concentration was determined on the basis of the concentration of the remaining antibodies [157]. Polyclonal antibodies were developed against two peptides to measure the amount of enzyme product formed (dipeptide assay) or the amount of remaining enzyme substrate (tripeptide assay), respectively [158].

For detection of glycopeptide antibiotics in milk, molecularly imprinted nanostructures were developed and high-affinity synthetic receptors were linked to an SPR sensor [159]. An SPR-based sensor system enabled the simultaneous analysis of eight antibiotics [160].

LSPR-based sensors have attracted attention owing to their high sensitivity and to the simplicity of analytical procedures. Depending on the nature of the LSPR change, they can be divided into aggregation-based and refractive index-based sensors [102]. LSPR measurements provide a reliable, label-free, and cost-effective analytical tool for the detection of nucleic acids and enable antimicrobial resistance determinants to be monitored [161]. An LSPR sensor system was made by using aptamers in the development of a colorimetric aptasensor for the detection of oxytetracycline on the basis of aggregation of aptamer-functionalized AuNRs [162].

Another study showed the possibility of using a silicon nanopillar metasurface coupled with LSPR for the real-time detection of cephalexin. The metasurface was coupled to BSA-coated gold nanospheres to ensure a red shift in the peak resonance wavelength values, which occurs only in the presence of an antibiotic linker. The fabricated device showed a strong wavelength shift of 22 nm, driven by a change in the local refractive index in the presence of the antibiotic linker [163]. Table 3 summarizes the main achievements of SPR-based optical sensors in antibiotic detection.

Table 3.

Main SPR-based and LSPR-based optical sensors for antibiotic detection.

The LSPR effect of gold nanoparticles made it possible to amplify SPR signals, lowering the enrofloxacin detection limit by a factor of 14. Gold nanospheres are frequently used as colorimetric indicators because of their SPR characteristics [68,164,168,169]. Besides the traditional SPR analysis, a substrate diffraction grating can be used to determine antibiotics [165].

By combining of SPR plastic optical fiber (SPR-POF) with electrochemical (bio) sensor, a sensor for ampicillin detection in water was developed [166]. Two SPR biosensor tests were developed to detect β-lactams in milk. These assays rely on the activity of carboxypeptidase, which converts 3-peptide to 2-peptide, and β-lactams inhibit this process. Antibodies in the sensor were used to measure the amount of enzyme product formed or the amount of enzymatic substrate left behind [167].

More possibilities of using SPR-based biosensors for antibiotic detection were shown in [170]. SPR-based sensors permit the detection and study of biochemical reactions at the level of individual biomolecules without additional functionalization of the sensor surface. The main limitations of these sensors are: surface plasmon penetration depth, contribution of the solution volume to the signal, and optical dispersion of the sample, which can reduce the accuracy of estimation of the refractive index.

4.4. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectra

Because of the unique structure of antibiotic molecules, light waves are absorbed, reflected, and scattered differently when they pass through them. This is the basic idea behind molecular spectroscopy-based antibiotic detection. As a result, molecular spectroscopy offers crucial details regarding the molecular makeup of extremely particular materials. The techniques used in molecular spectroscopy include terahertz spectrum detection, room-temperature phosphorescence, resonant Rayleigh scattering, and surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) is a highly sensitive technique that enhances the Raman scattering of molecules supported by certain nanostructured materials [171].

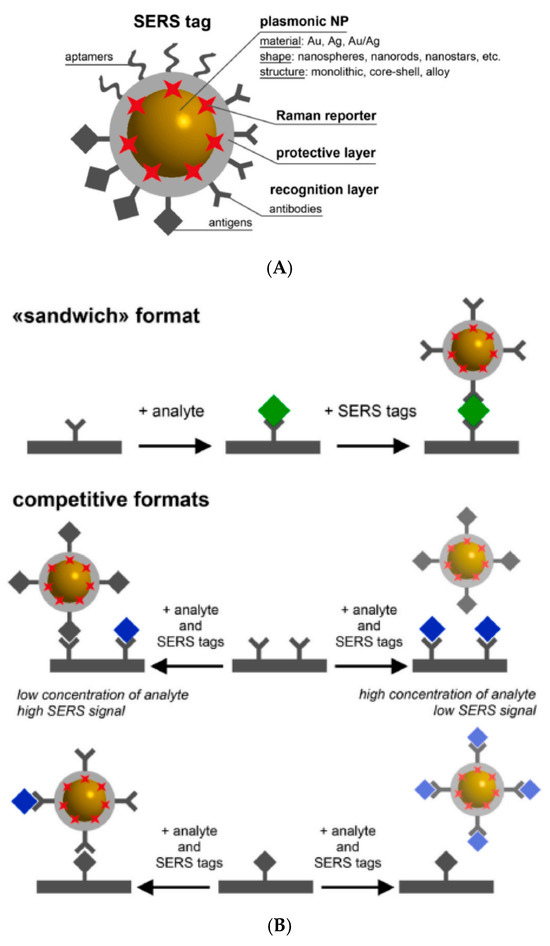

Most of the recent applications in SERS sensing have been aimed at the determination of one or more specific analytes. Such targeted assays most often use an indirect detection strategy (label-based SERS), in which the observed SERS signal originates not from the targets themselves but from SERS tags (consisting of molecular reporters or tags on a plasmonic nanostructure) that are selectively conjugated to the target through a recognition element [172].

The schematic design of a SERS tag (A) and the main formats of SERS immunoassays (B) are presented in Figure 5 and are described in [173].

Figure 5.

The architecture of a SERS tag (A) and the main formats of SERS immunoassays (B) (Reprinted from [173]. Creative Commons CC BY license).

Numerous studies have determined the susceptibility of bacteria to antibiotics by SERS-based methods [174,175,176,177] and have used SERS to analyze the activity of antimicrobials [178]. An equally progressive area of research is the use of SERS to determine antibiotics (quinolones, tetracyclines, sulfonamides, aminoglycosides, amphenicols, β-lactams, nitrofurans, macrolides, and nitroimidazoles) in foodstuffs, water, and biological matrices [179].

An important aspect in the development of SERS systems is to increase their antibiotic-detecting sensitivity. One approach to improving detection limits is to use metal nanoparticles [10,68]. For example, the use of silver nanosubstrates coated with colloidal gold made it possible to enhance the recorded analytic SERS signal [180]. The results of these studies facilitated the application of SERS-based sensor substrates modified with metal nanoparticles. In another study, a silver film was deposited both on the surface of aluminum oxide and within its adjustable pores. Because the pore size of the aluminum oxide film is adjustable, the resonant wavelength of the silver films is adjustable too. This allows the aluminum oxide pore size to be tuned so that the resonant wavelength is within the range of the light source and the optical spectrum analyzer. This method maximizes Raman signal amplification and has been tested for the determination of chloramphenicol in milk [181]. By ensuring the ability of the analyte to interact with colloidal silver and by optimizing the aggregation of silver nanoparticles, the SERS intensity and sensitivity of ampicillin detection were increased [182]. For high-throughput analysis, a second method based on LSPR was proposed for tobramycin detection in human serum. The method uses functionalized nanoparticles and SERS analysis [183]. Table 4 summarizes the main achievements of SERS-based optical sensors in antibiotic detection.

Table 4.

Main SERS-based optical sensors for antibiotic detection.

In a different investigation, penicillin G residues in an actual milk sample were found by the SERS approach in conjunction with two-step sample preparation, which prevents interference from other sample components [184].

By using two immunonanoprobes (one for neomycin and the other for quinolones), a SERS detection device, and a portable lateral flow analyzer (LFA), neomycin and quinolone antibiotics were detected in a single step. The two probes were made up of monoclonal antibodies against the matching antibodies and gold nanoparticles coupled to the Raman-active compound 4-aminothiophenol [185].

For the label-free detection of quinoline, two gold nanostructures were proposed as SERS substrates as presented in [186].

Li et al. [187] investigated a disposable Ag–graphene sensor that uses electrophoretic preconcentration with SERS to detect polar antibiotics in water. The sensor promoted the adsorption of molecules owing to the weak π-π interactions between graphene and antibiotics. This increased the sensitivity of SERS detection of antibiotics in aqueous samples without their preliminary separation.

Because of the strong ability of silver nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes intercalated into graphene oxide (AgNPs/CNT–GO) to be enriched through π-π stacking and electrostatic interactions of GO with antibiotic molecules, the use of laminar membranes composed of AgNPs/CNT–GO allowed the determination of sub-nanomolar concentrations of antibiotics [188].

Trace amounts of sulfonamides were determined with great sensitivity and repeatability by a new method combining surface modification with Ag nanoparticle gelation [189]. In Hong et al. [190], SERS nanogratings (platforms supporting the SERS effect) were made by laser interference lithography.

The concept of using SERS to detect residues of antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, cefazolin, and enrofloxacin) in wastewater and tap water was further developed with the aid of high-performance SERS chips based on self-assembled hollow Ag octahedra. These chips expanded the scope of in situsensitive detection and identification of antibiotic residues [191].

The limitations of the method are related to the need for pretreatment in the analysis of complex matrices and for modification of the molecular sensor. Analysis of the recorded SERS spectra requires powerful artificial intelligence and machine learning tools, because the complexity of SERS spectra in actual matrices is high owing to different background compositions or higher concentrations of the matrix components, as compared with those of the target molecules. Thus, further development of SERS sensors for antibiotic detection is aimed at improving the analytic SERS signals; the reproducibility, repeatability, and stability of the sensors; and the adaptation of the sensors to work with actual samples [173,192].

4.5. Photonic Crystal Biosensors

Brightly colored photonic crystals (PCs) are novel materials that are frequently used in biological sensors. Because they alter their structural color as they interact chemically with organic solvents, they represent perfect sensor materials for detection by the naked eye. Compared with conventional biochemical sensors, PC-based ones have shown great sensitivity and promise in point-of-care diagnostics and in quick screening [193].

In order to stop light from propagating in particular directions at particular frequencies, PCs are made of components with alternating permittivities on a length scale similar to the wavelength of light. When PCs are used as sensing elements for high-performance detection, their unique structural color can function as a label-free photonic code. The size of the PC building blocks can precisely control this photonic code. Main information on PC sensors can be found in [194]. Optical sensors using PCs are distinguished by their structure, which allows precise control of the optical properties of the sensor and ensures accurate analysis without the use of labels with the possibility of conducting multiplex studies [194].

Biosensors embedded in PC structures are promising for the rapid and precise detection of target substrates. The optical waves measured in these sensors are tangible manifestations of Maxwell’s equations, and the wavelength frequency plays a direct part in the characteristics of the medium through which the light (or, more generally, electromagnetic waves) propagates. Information and energy transfer in a PC is controlled by the total group velocity of the Bloch modes at a given frequency of the electromagnetic wave (i.e., light at optical frequencies) incident on the PC medium [195]. Because the PC has a strong detection response, it is an ideal substrate for sensing and has good potential for rapid qualitative and quantitative detection of antibiotics. For example, kanamycin can be detected with a two-dimensional SiO2–Au–ssDNA PC, formed from PCs, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), and aptamers [196]. Table 5 summarizes the main achievements of PC biosensors in antibiotic detection.

Table 5.

Main PC sensors for antibiotic detection.

For colorimetric detection of penicillin G and penicillinase inhibitors, a two-dimensional PC hydrogel-containing penicillinase biosensor was made [197]. Progress in photonic biosensors has been shown by the development of the corresponding chips for the detection of antibiotics (gentamicin) by binding to the corresponding antibody pre-immobilized on the sensor surface [198]. PC microcavities formed by two-dimensional air holes on silicon substrates and antibodies immobilized on the sensor surface led to highly specific detection of gentamicin [198]. The authors showed that a silicon photonic biosensor platform can be implemented as a portable lab-on-a-chip sensor system, in which the integration of the sensor chip with microfluidic components enables automated real-time testing of samples. A photonic sensor using a self-cross-linked imprinting close-packed opal as a recognition element for chloramphenicol detection was described in [199]. Photonic sensor systems deserve special attention in connection with advances in molecular imprinting, which will be discussed below.

In summary, basic research has confirmed that the detection spectrum can be enhanced by adjusting the size of the building blocks to shift the optical response to the mid-infrared region of the spectrum. However, the main limitation of PC-based sensors is associated with their use to detect antibiotics in actual samples.

4.6. Fiber-Optic Biosensors

Because optical fibers are inexpensive, respond quickly, and are simple to analyze, their application in bio- and immunosensors shows promise. The fiber typically transmits a range of wavelengths of infrared light. By using the total internal reflection of light as it travels through a waveguide, fiber-optic biosensors produce an attenuated wave boundary on the waveguide’s surface. Compared with conventional immunoassay techniques, fiber-optic sensors based on antibodies or immunoassays provide higher sensitivity, selectivity, and speed [200].

Fiber-optic sensors have some advantages over traditional electronic sensors, such as resistance to radiation, fire, radio frequency and other electromagnetic interference, and leakage. They do this by using optical signals as the transmission channel to detect a range of physical characteristics. They may be used over long distances and perform well in distributed sensing systems. Because of the characteristics of nanofibers and the U-shaped optical fiber, the sensitivity at the resonant wavelength increases as the nanofiber electrospinning process lasts longer. The bend radius causes a shift in the sensor’s peak signal. Total reflection at the core–cladding interface is not constant as light reaches the bend zone, and a leaky mode forms in the U-shaped optical fiber’s bend region. A waveguide model is made by reflections that take place at the contact between the external medium and the cladding [201].

The constant progress in the development of fiber-optic sensors opens new possibilities for antibiotic detection owing to the advantages of low cost, ease of operation, and high sensitivity. Optical fibers have important properties, including compact size, light weight, integrability, remote sensing and high sensitivity [202,203].

Fiber optics provides several benefits, including ease of installation and operation, corrosion resistance, superior biocompatibility, and resistance to electromagnetic and electrostatic interference. Compound detection is made possible by the optical qualities of fiber. Immobilizing biological components in a coating is the most basic fiber optic biosensor concept; additional layers can be added to the coating to enhance the sensor’s functionality, as described in [204].

A U-shaped fiber immunosensor was used for the ultra-sensitive detection of ciprofloxacin in wastewater. Immunoglobulin was mounted on the surface of a silicon fiber functionalized with polymeric polyaniline [205]. Optical and electrochemical sensors that can detect ciprofloxacin in water rapidly, sensitively, and in situ were described in [206].

The chelation interaction between antibiotic and Cu2+ allows the measurement of the relative change in Cu2+. The entire electrochemical reaction may be tracked in real time by the plasmonic fiber sensor owing to its high sensitivity to interfacial interactions. The built-in fiber sensor also boasts great specificity, quick detection (255 s), and remarkable sensitivity (fM level) [206]. A U-shaped lossy fiber optic resonant mode structure coated with indium tin oxide for ciprofloxacin detection that is sensitive was reported on in [207].

A separate area of research is optical sensors based on a label-free, time-resolved method called reflectometric interference spectroscopy. The use of various types of interferometers (mainly Mach–Zehnder and Michelson) in optical sensors allows the size of the sensor itself to be reduced without loss of sensitivity. Such biosensors operate by measuring the phase shift between the measured and reference signals. This detection principle was first described for penicillin detection. The method relies on white light interference in thin layers to observe molecular interactions, and studies can be conducted in a buffer by using commercial antibodies [208]. Another study reported on an optical biosensor method that is based on biolayer interferometry and uses a kinetic competitive binding assay. The method can determine less than 1 ppm (~33 μM) of amoxicillin. Similarly to the surface plasmon resonance, the method enables the detection of changes occurring upon binding of the antibody molecule to amoxicillin [209]. Table 6 summarizes the main achievements of optical-fiber biosensors in antibiotic detection.

Table 6.

Main optical-fiber sensors for antibiotic detection.

A fiber-optic system for rapid determination of antibiotic concentrations was experimentally validated. It is based on an optical enzyme biosensor with a microfiber interferometer and variation in fiber grating power. During the experiment, β-lactamase is immobilized on a polyaniline-coated optical fiber through covalent cross-linking with glutaraldehyde. β-Lactamase can hydrolyze β-lactam antibiotics, forming acidic byproducts that convert polyaniline from its emerald base form to its emerald salt. This leads to a change in the surface refractive index, which is recorded with a microfiber interferometer during the determination of the concentration of β-lactam antibiotics [210].

A chitosan/porous silicon substrate exposed to liquids containing different doses of ibuprofen was used for optical interferometric measurements. In comparison to the unfunctionalized porous film, the inclusion of chitosan increased the sensitivity of the porous film by more than an order of magnitude [211].

The immunosuppressive principle was used to construct a fiber-optic surface plasmon resonance sensor for the detection of ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin in milk [212].

The potential of a compact optical fiber-based nanomotion sensor was shown for monitoring of dynamic nanoscale cantilever vibrations associated with the viability of the microorganisms whose antibiotic sensitivity was examined—Escherichia coli and Candida albicans. The analysis took several minutes [214].

A micro-structured optofluidic in-fiber Raman sensor was developed for ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin detection in aqueous media [213].

An innovative approach (Lab-Around-Fiber), which consists of biofunctionalization of silicon optical fibers by grafting antibodies to their outer surface, was described for the identification of target molecules [215].

In recent years, microfiber has been gradually adopted as a tool for antibiotic detection owing to its extremely low optical transmission loss, high refractive index difference between the core and cladding, and high evanescent wavelength transmission. The method of combining materials with optical fiber to form a fiber sensor is simple to operate, efficient, and easy to implement. It can be substance-specific and provides a new platform for antibiotic detection. Further optimization of optical wave sensor systems and their integration with other methods holds great promise for detecting antimicrobial residues in water and beverages.

4.7. Optical Sensors Based on Molecularly Imprinted Polymers

Recognition elements (antibodies, antigens, immunoglobulins, enzymes, and aptamers), most frequently used to form the receptor layer of sensors, are highly specific and enable the acquisition of information about the progress of biochemical reactions in solutions in near real time. When biological objects are used as receptors, it is important to increase the service life of sensors based on them. The complexity of obtaining natural receptors, their instability during storage, exposure to organic solvents, and high electrolyte concentrations promote the search for synthetic antibodies. These can be developed through the use of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), which offer several undeniable advantages over biomolecules. These advantages include methodological simplicity of production (in contrast, e.g., to the production of antibodies to low-molecular-weight compounds, which is a multi-stage and time-consuming process), and high reproducibility of the synthesis. In addition, MIPs are stable in aggressive environments and under abrupt changes in operating conditions and can be synthesized for virtually any substance, including inorganic ions, drugs, nucleic acids, proteins, cells, and even supertoxic compounds for which, for example, polyclonal antibodies cannot be obtained.

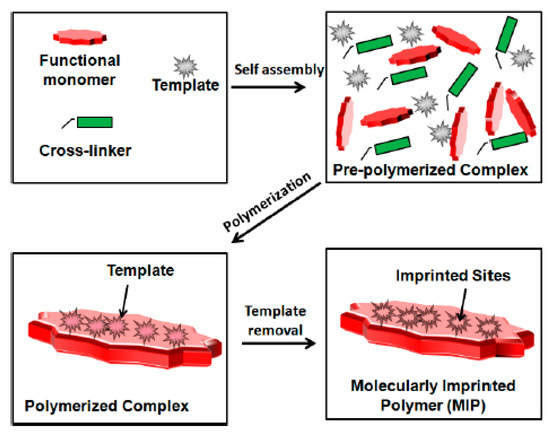

Molecular imprinting is a method for obtaining “molecular imprints” based on the polymerization of functional monomers in the presence of specially introduced target template molecules. When combined with suitable sensor platforms, MIPs are very attractive for the routine environmental monitoring of antibiotics, with account taken of their low production cost, high stability, and high selectivity. Consequently, MIP-based sensors for antibiotics have been reported in the past decade [216].

The most common method for synthesizing MIPs is bulk polymerization. Molecular imprinting is dominated by nonlinear polymers with a macroscopic lattice, which provide the binding sites with the necessary rigidity and mechanical stability. The final structure of such polymers is determined by the crosslinking coefficient, equal to the percentage molar ratio of the crosslinking agent to the monomer, and also by the volume and nature of the pore-forming solvent in which the polymerization occurs [217].

Surface imprinting, nanoimprinting, living/controlled radical polymerization technology, multi-template, multifunctional monomer, and dummy template imprinting strategies are some of the MIP modes that have been developed and applied for antibiotic detection [218,219,220]. By creating MIPs as a layer on solid particles, surface imprinting technology produces recognition sites with a significant affinity for the substrate surface. Because evenly distributed sites increase the MIPs’ adsorption capacity and the rate at which the recognition sites rebind to the imprinted molecules, they improve the adsorption and separation efficacy of the imprinted material. Eluting and recovering template molecules are facilitated by the concentration of all binding sites on the surface. The size of the impression cavity on the polymer surface can be effectively controlled thanks to this technology. Fast resolution, fast processing speed, high throughput, compatibility with a variety of materials, and low cost are all benefits of using nanoimprinting technology to create nanostructured MIPs.

Therefore, this process is appropriate for producing antimicrobial surfaces based on different polymer surfaces on a wide scale. It is anticipated that nanoimprinted materials will enhance the MIPs’ site accessibility, rebinding kinetics, and adsorption capacity. MIPs for the detection of antibiotic residues and other environmental toxins, such as nitroxide-mediated free radical polymerization, atom transfer radical polymerization, and reversible addition-fragmentation reaction, are increasingly being prepared using LCRP technology [170,171]. The main achievements of MIPs, including prospects and applications concerning new production technologies and strategies, can be found in [221].

Sensors based on MIPs are an important development in the field of biosensor-aided detection of antibacterial medication residues in food products [222,223,224]. Recent advances in optical sensing systems have focused on their integration with molecular imprinting. When integrated with an optical sensor-transducer, MIPs show high potential for environmental monitoring, including antibiotic detection. Researchers have taken notice of MIPs because of their strong, precise affinity for the template molecule. The MIP method achieves great selectivity for the analyte under determination by creating extra template imprints. Figure 6 is a schematic diagram of MIP synthesis [225].

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of MIP synthesis (Reprinted from [225]. Creative Commons CC BY license).

Optical sensing platforms use various optical phenomena arising from the interaction of the analyte with the MIP layer to obtain analyte-correlated sensor responses. Optical sensors are usually very sensitive; therefore, their combination with target-selective MIPs is important in label-free molecular analysis. The most commonly used optical platforms in molecular imprinting are SPR and SERS [216].

Despite the high sensitivity of the SPR method, its versatility was initially limited to the analysis of large biomolecules owing to difficulties in working with biologically and environmentally important small analytes, because the induced change in the refractive index is usually too small to obtain adequate responses [226]. Owing to their robustness, which allows them to withstand harsh chemical conditions of regeneration without noticeable loss of activity, MIPs are adaptive and selective, and they easily integrate with the SPR, as compared with antibodies [227].

Sensors that use MIPs in conjunction with the SPR or LSPR offer extremely sensitive, real-time detection with quick reaction times [225]. A succinct overview of the construction, characteristics, and possible uses of screen-printed electrodes in bacterial, antibiotic, and antibiotic susceptibility testing can be found in [228].

Another study reported on tetracycline detection by using MIPs in conjunction with an optical-fiber sensor [229]. Table 7 summarizes the main achievements of MIP-based optical sensors in antibiotic detection.

Table 7.

Main MIP-based optical sensor systems in antibiotic detection.

MIPs overcome the shortcomings of antibodies, associated with their short lifespan and difficulty in storage. They are formed by fixing a functional monomer (a molecule of a specific antibiotic) on a specific substrate, thus forming a specific component for detecting the antibiotic.

For improving control over the formation of MIP films, photopolymerization was used, and MIP films were made that were uniform and controlled in thickness. For the specific detection of ciprofloxacin and its structural counterpart ofloxacin, an SPR-based sensor was created in conjunction with a nanoscale MIP film as a recognition element [230].

The determination of neomycin, kanamycin, and streptomycin in milk by using MIP films and gold nanoparticles for signal enhancement was described in [231].

For real-time antibiotic monitoring, an analytic method combining a label-free sensor platform with a MIP as a potent recognition component was helpful. A highly selective hybrid organic–inorganic MIP film was incorporated into an SPR sensor. This film showed a binding affinity for the antibiotic that was about 16 times greater than that of the same reference non-imprinted polymer. Rebinding and regeneration were carried out in multiple cycles with good repeatability. The stability of the sensor can be maintained at room temperature for up to six months [232].