1. Introduction

Complex water networks serve as the core carrier of water resource circulation and socio-economic development in river basins, serving multiple functions: flood control and drainage, water supply, and ecological protection [

1,

2,

3]. The level of scheduling optimization directly impacts regional water security, sustainable socio-economic development, and ecological health [

4,

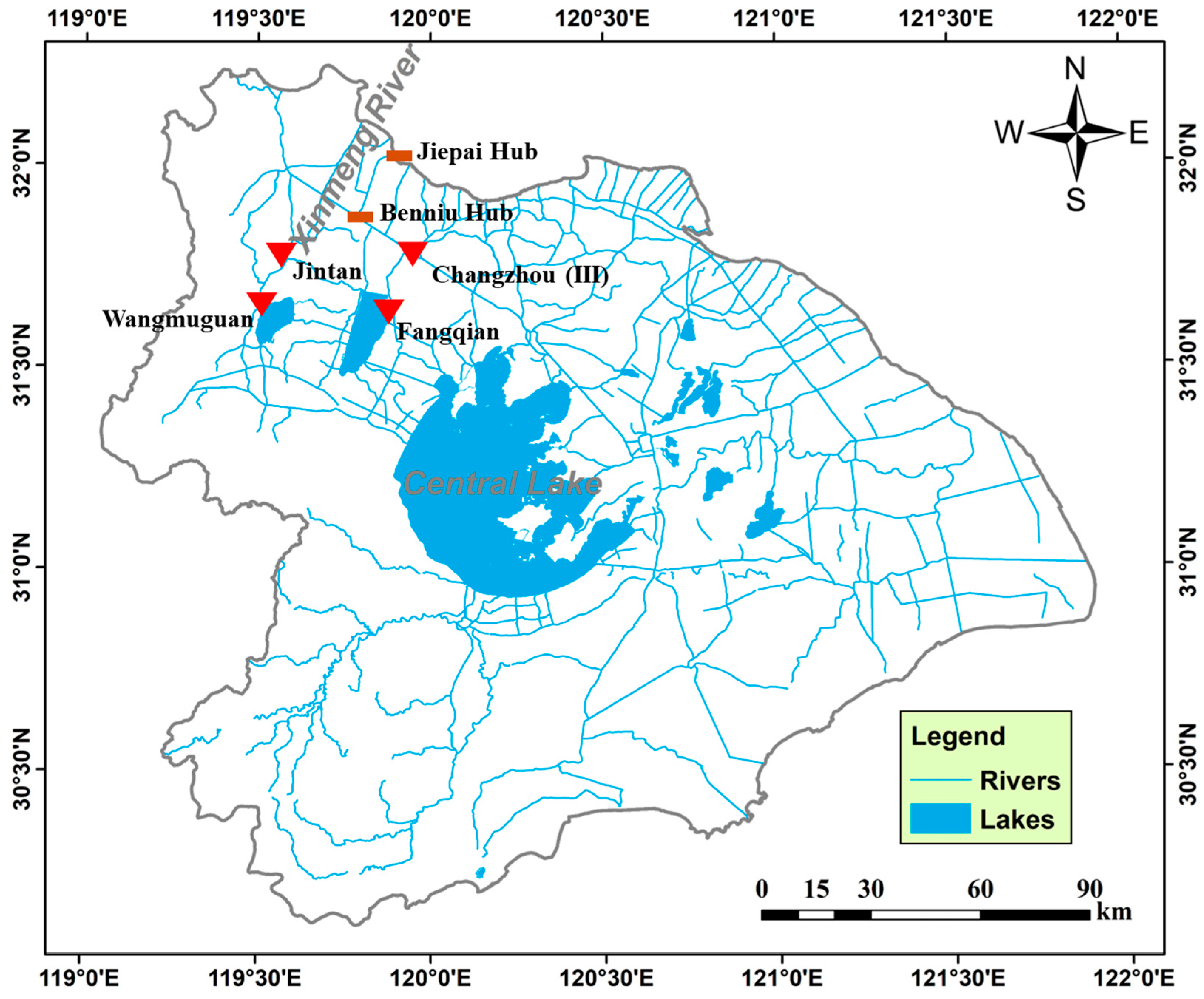

5]. Typical complex water network areas represented by the Taihu Lake Basin in the Yangtze River Delta are characterized by intertwined rivers and lakes, dense water conservancy projects, dense populations, and developed economies. They also face prominent flood risks, urgent water supply demands, and sensitive ecological environments [

6,

7]. In recent years, affected by the dual impacts of climate change and human activities, extreme rainfall, droughts, and other disasters have occurred frequently [

8]. Conflicts between flood control, water supply, and ecological protection goals in the basin are increasingly acute. Traditional decentralized, single-objective scheduling models can no longer address multi-dimensional, composite water security challenges [

9]. Therefore, conducting research on joint water resources scheduling in complex water networks to achieve multi-objective coordination holds significant theoretical and practical significance for improving the efficiency of regional water resource allocation, reducing disaster risks, and maintaining ecological balance.

Currently, academics and practical management departments have carried out extensive research and practice on water resources scheduling. In terms of scheduling methods, early studies focused on single-objective optimization, such as reservoir flood control or water supply scheduling models based on linear programming and dynamic programming, which achieve single-objective optimal solutions by simplifying constraints. Specifically, regarding multi-objective coordinated scheduling for complex water networks, existing studies have made remarkable progress but still have obvious gaps. In the construction of multi-objective indicator systems, scholars have gradually expanded from traditional flood control and water supply dual objectives to integrated ecological and water quality indicators [

4,

10]. For example, Wang et al. established a multi-objective system for regional water resources scheduling, which provided a solid foundation for multi-objective coordination in general regional contexts [

4]. However, when applied to complex lake-basin coupled water networks such as the Taihu Lake Basin, the indicator system lacks specific differentiation and does not fully capture the unique hydraulic coupling characteristics between rivers and lakes—an aspect that is particularly critical for scheduling optimization in such complex water systems. In terms of weighting strategy optimization, common methods include subjective weighting (e.g., AHP, Delphi) and objective weighting (e.g., entropy weight, CRITIC) [

10]. However, most studies adopted fixed weight coefficients, which cannot dynamically adjust according to seasonal hydrological scenarios (e.g., flood season vs. non-flood season), leading to poor adaptability of scheduling schemes [

11]. In the aspect of scheduling model coupling, researchers have integrated hydrodynamic models with intelligent algorithms—such as coupling MIKE 11 with genetic algorithms for river network scheduling [

12]—but few studies have fully coupled water quantity and water quality processes. Wu et al. (2025) made valuable contributions by verifying the impact of the Xinmeng River Project on lake water quality, providing important empirical support for understanding the project’s environmental effects [

13]. For the scenario of multi-objective coordinated scheduling in complex water networks, however, the integration of water quality simulation into the optimization framework remains to be realized—an integration that is particularly critical for achieving comprehensive coordination of water quantity and quality goals. In terms of engineering application adaptation, existing models are mostly designed for mature water conservancy projects, and there is a lack of targeted scheduling frameworks for newly commissioned projects, resulting in a disconnect between theoretical optimization and practical operation [

14]. These gaps indicate that the existing research has not yet fully addressed the technical challenges of multi-objective coordination in complex water networks, highlighting the necessity of this study. In terms of scheduling methods, early studies focused on single-objective optimization, such as reservoir flood control or water supply scheduling models based on linear programming and dynamic programming, which achieve single-objective optimal solutions by simplifying constraints.

With in-depth research and the development of computer technology, intelligent optimization algorithms (e.g., genetic algorithms, particle swarm optimization algorithms, differential evolution algorithms) and multi-objective evolutionary algorithms (e.g., NSGA-II, MOPSO) have been widely applied to multi-objective scheduling problems, providing decision support by generating Pareto non-dominated solution sets [

10]. In practice, management departments mostly conduct scheduling based on empirical rules or single-objective priorities, such as the Water Diversion from the Yangtze River to Taihu Lake project and the joint flood control scheduling of cascade reservoirs groups in the Yangtze River Basin, which have achieved certain results in specific scenarios [

13,

15,

16]. However, the core challenge of scheduling in complex water networks lies in the complexity of multi-objective coordination: on one hand, natural contradictions exist between flood control, water supply, and ecological protection goals across temporal and spatial scales, such as the conflict between rapid drainage for flood control during the flood season and water storage for supply after the flood season, and the trade-off between water diversion for water quality improvement and engineering operation cost control; on the other hand, scheduling demands vary across basin, regional, and urban levels, and the interest demands of upstream and downstream, left and right banks are intertwined, further increasing the difficulty of multi-objective coordination [

12,

17,

18]. Although existing multi-objective optimization algorithms can generate non-dominated solution sets, they insufficiently consider the strong coupling characteristics of complex water networks, and the selection of solution sets relies on subjective judgments. It is difficult to form scheduling schemes that balance scientific rigor and practical operability, and the systematicness and effectiveness of multi-objective coordination have not been fully realized [

14].

Despite these advances, four critical literature gaps remain unaddressed, which restricts the practical application of multi-objective coordinated scheduling in complex water networks. First, most existing multi-objective studies adopt fixed weighting methods or static Pareto solution sets, lacking dynamic weight adjustment strategies tailored to different hydrological scenarios (e.g., flood control vs. water supply periods). This leads to poor adaptability of scheduling schemes to temporal and spatial variations in water resource demands. Second, existing algorithms fail to fully account for the strong hydraulic coupling and nonlinear relationships among numerous water conservancy projects in complex water networks, resulting in optimization results that deviate from practical engineering operations. Third, the integration of water quantity scheduling, water quality simulation, and ecological protection objectives is inadequate—most studies either separate water quantity and quality management or treat ecological indicators as secondary constraints, failing to achieve truly comprehensive multi-objective coordination. Fourth, few studies have integrated optimization models with the operational rules of newly constructed hydraulic projects, leading to a disconnect between theoretical optimization and on-the-ground implementation. These gaps highlight the urgent need for a more systematic and adaptive multi-objective scheduling framework.

The technical bottlenecks faced by water resources scheduling in complex water networks further restrict the improvement of optimization effects. First, the comprehensiveness and correlation of objectives require consideration of multiple dimensions including flood control safety, water supply guarantee, water quality improvement, and ecological maintenance. Each objective has different physical dimensions and optimization directions, making direct quantitative coordination difficult [

11]. Second, complex water networks have intricate structures and numerous water conservancy projects (including reservoirs, pumping stations, sluices, etc.), with close hydraulic connections and significant nonlinear characteristics between projects, increasing the difficulty of scheduling model construction [

19]. Third, water quantity and quality simulation is the foundation of scheduling optimization. However, complex water networks span large temporal and spatial scales and are influenced by multiple factors. Simulations involve extensive parameter calibration and numerical calculations, with each simulation requiring substantial computation time. This makes it difficult for traditional optimization algorithms to achieve efficient solving within the feasible region, preventing rapid optimal solution acquisition through iteration like in single reservoir scheduling [

20]. These bottlenecks hinder existing scheduling methods from balancing optimization accuracy and computational efficiency in complex water networks, limiting the practical application of multi-objective coordinated scheduling.

To address this issue, this study takes the Taihu Lake Basin as a typical case and conducts systematic research to break through technical bottlenecks, focusing on the core demand of multi-objective coordinated scheduling in complex water networks. First, based on scheduling demands at basin, regional, and urban levels, a multi-objective optimization indicator system covering three major areas (flood control, water supply, and ecological environment) is constructed, comprehensively including key indicators such as drainage efficiency, water supply guarantee rate, and water quality improvement degree. Second, corresponding objective functions for each domain are established, clarifying the optimization direction and constraint conditions of different indicators. Third, an innovative variable weighting strategy is adopted to dynamically adjust the weights of each objective according to different hydrological scenarios (flood control period, water supply period, ecological environment period, etc.), converting the multi-objective optimization problem into a single-objective optimization problem to simplify solving complexity. Finally, a combined solving mode of basin water quantity-quality model and joint scheduling decision model is adopted, combining intelligent algorithms to improve computational efficiency. This study effectively overcomes complex water network technical bottlenecks—multiple conflicting objectives, intricate water system structures, dense hydraulic projects, and heavy computational loads—via an integrated technical process: indicator system construction, objective function establishment, dynamic weighting transformation, and combined model solving. It thereby provides novel theoretical and technical support for the multi-objective coordinated scheduling of water resources in such complex systems.

2. Methodology

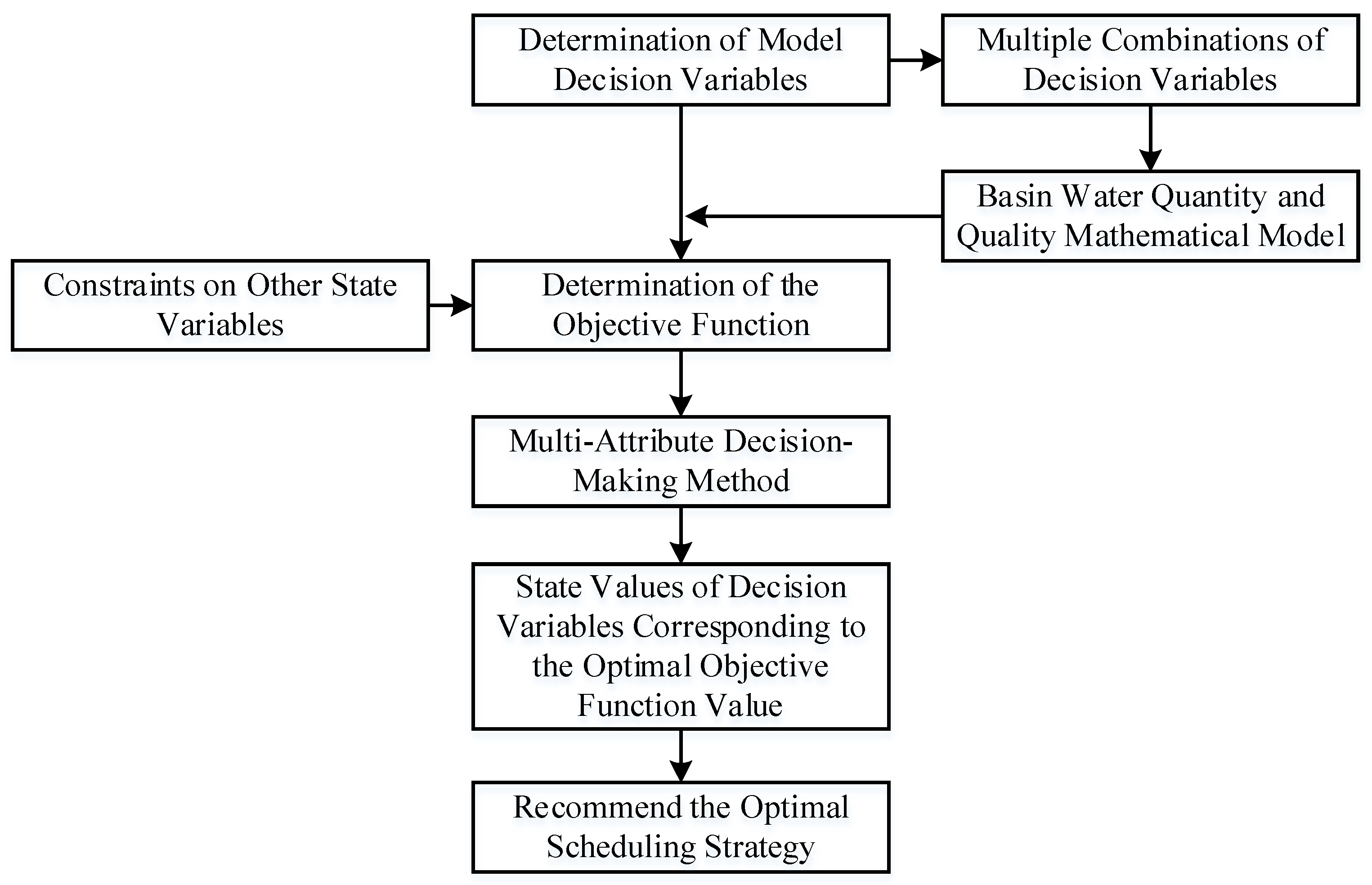

To realize multi-objective coordinated water resources scheduling in complex water networks, this study establishes an integrated technical framework (see

Figure 1) that integrates indicator system construction, objective function formulation, constraint definition, and combined model solving. This framework operates through a systematic and sequential process to ensure scientificity and operability.

First, a comprehensive multi-objective optimization indicator system is constructed to cover the core demands of flood control, water supply, and aquatic ecological protection. These indicators, selected based on principles of systematicness, conciseness, importance, and independence, provide quantitative criteria for evaluating scheduling effects. Second, targeted objective functions are established for each domain, clarifying the optimization direction of flood control safety, water supply guarantee, and ecological health. Third, seven key constraint conditions are defined, including water balance, water level, flow rate, flow velocity, water quality, water quality balance, and engineering operation, to limit the feasible solution space and ensure consistency with practical engineering operations. Fourth, a combined solving mode is adopted: the basin water quantity-quality model serves as the foundation to simulate dynamic changes in water level, discharge, and water quality under different scenarios, while the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm is applied to optimize scheduling alternatives, improving the efficiency and accuracy of solution acquisition.

This integrated framework seamlessly connects each technical link, from demand-oriented indicator design to constraint-based model construction, and finally to algorithm-driven optimization. It effectively addresses technical challenges such as conflicting multi-objectives, complex hydraulic connections, and heavy computational loads in complex water networks, providing a systematic and operable technical path for coordinated scheduling. The weight determination method (AHP) adopted in this study is only a supporting link within the framework, used to balance the relative importance of different objectives under specific scenarios, and does not affect the integrity and applicability of the overall technical system.

Regarding the implementation form of dynamic adjustment in this framework: it is designed with dual adaptability to meet different practical needs. In this case study, dynamic adjustment is implemented as an offline setting—specific weight combinations for different scheduling periods are predetermined based on historical hydrological characteristics, regional scheduling priorities, and expert experience. This design ensures that the scheduling scheme is stable and reliable, avoiding excessive fluctuations caused by frequent adjustments and aligning with the actual operation habits of water conservancy projects. Meanwhile, the framework has inherent extensibility for real-time adjustment: if high-frequency real-time monitoring data (e.g., real-time rainfall, water level, water quality, and water demand) are available, the dynamic adjustment mechanism can be integrated with a data-driven module. The system can automatically update objective weights or scheduling parameters based on the deviation between real-time operational status and preset thresholds, realizing adaptive adjustment during operation. This real-time mode requires support from mature monitoring infrastructure and efficient algorithm response capabilities, which is not the focus of the current study but constitutes a key direction for future application expansion and technical upgrading.

2.1. Decision Indicators

Decision indicators refer to the undetermined control variables or operating variables involved in optimal decision problems that are related to constraints and objective functions. The corresponding state of a set of decision variables constitutes a solution to the optimal decision problem.

The decision indicators of the model are determined by the control indicators involved in the operation of water conservancy projects in river network areas. Complex river networks usually have numerous water conservancy projects, and their operation has complex nonlinear relationships with regional water level, quantity, and quality indicators. This study selects the operation control indicators that have relatively strong sensitive relationships with water quantity and water quality objectives as the decision variables of the joint scheduling model. This study selects decision indicators from three aspects: the fields of flood control objectives, water supply objectives, and aquatic ecological environment objectives, ensuring that the joint scheduling schemes can meet the comprehensive water quantity and water quality scheduling needs of the areas involved in the project. When selecting indicators, the principles of systematicness, conciseness, importance, and independence should be followed.

2.1.1. Decision Indicators for Flood Control Objectives

Four indicators in the field of flood control objectives are selected as decision variables, including the drainage efficiency of key outward discharge hubs, the exceedance risk of flood control representative stations above the protection standard, the regional outward discharge coefficient, and the satisfaction degree of pre-discharge objectives.

(1) Drainage efficiency of key outward discharge hubs

DS

where

Q denotes the actual discharge flow at the control section of key outward discharge hub;

Qd represents the maximum designed flow capacity of key outward discharge hub;

Z is the actual water level of basin and regional representative stations during the scheduling period;

Zw stands for the flood control warning water level of basin and regional representative stations. The drainage efficiency of key outward discharge hubs (

DS) is a higher-is-better indicator.

(2) Exceedance risk of flood control representative stations above the protection standard

CB

where

is the water level of the flood control representative station at time

t;

Hw denotes the flood control guaranteed water level of the flood control representative station;

represents the duration of exceedance above the protection standard.

(3) Regional outward discharge coefficient

WP

where

P denotes the outward discharge volume of a specific region within a certain period;

R represents the local water yield of the same region during the same period;

W is the incoming water volume from other regions entering the same region.

(4) Satisfaction degree of pre-discharge objectives PY

For the objectives of pre-discharge scheduling for lakes, reservoirs, and other water bodies, the PY indicator value for the satisfaction degree of pre-discharge objectives is set according to the degree to which the current water level meets the pre-discharge objectives.

2.1.2. Decision Indicators for Water Supply Objectives

Four indicators in the field of water supply objectives are selected as decision variables, including the water supply efficiency of water diversion and supply projects, the water level satisfaction degree of water supply representative stations, the improvement degree of water quality indicators (NH3-N/DO/TN/TP/COD) in water sources, and the compliance guarantee rate of water quality indicators (NH3-N/DO/TP/COD) in water sources.

(1) Water supply efficiency of water diversion and supply projects

η

where

R is the water supply volume of the water diversion and supply project;

Y denotes the water diversion volume of the water diversion and supply project. The water supply efficiency of the water diversion and supply project is a higher-is-better indicator.

(2) Water level satisfaction degree of water supply representative stations

PG

where

is the water level of water supply representative station at time

t;

denotes the minimum allowable average water level of water supply representative station;

sgn(*) is the sign function—if the * is greater than 0, the value of

sgn(*) is 1; otherwise, it is 0. The water level satisfaction degree (satisfaction duration) of water supply representative stations is a higher-is-better indicator.

(3) Improvement degree of water quality indicators (NH3-N/DO/TN/TP/COD) in water sources

ID

where

is the concentration value of the water quality indicator

x at time

t.

(4) Compliance guarantee rate of water quality indicators (NH3-N/DO/TP/COD) in water sources

PQ

where

is the concentration value of water quality indicator

x in water sources at time

t;

denotes the critical compliance value of water quality indicator

x;

represents the scheduling time step;

T is the length of the scheduling period. The compliance guarantee rate of water quality indicators (NH3-N/DO/TN/TP/COD) in water sources is a higher-is-better indicator.

2.1.3. Decision Indicators for Aquatic Ecological Environment Objectives

(1) Guarantee rate of ecological water level

PW

where

is the ecological water level of the representative section;

denotes the water level of the representative section at a certain time

t.

(2) Improvement degree of water quality in the scheduling impact area

WD

where

is the concentration value of water quality indicator

x at the representative section of the scheduling impact area at time

t. The improvement degree of water quality indicators (NH3-N/DO/TN/TP/COD) at representative section of the scheduling impact area is a higher-is-better indicator.

(3) Improvement degree of flow velocity at the representative section

WL

where

is the flow velocity at the representative section of the river channel at time

t. The improvement degree of flow velocity at the representative section is a higher-is-better indicator.

(4) Water diversion cost W

Although the water diversion cost seems to be an economic accounting indicator, it is deeply bound to the “pressure, state, and response” of the aquatic ecological environment. Essentially, it serves as an “economic reflection” and “regulatory lever” of the aquatic ecological environment status, thus being incorporated into the aquatic ecological environment indicator system. This study adopts water diversion volume to measure water diversion cost, comprehensively taking into account water diversion time and water diversion scale:

where

is the water diversion flow at time

t. Water diversion cost is a lower-is-better indicator.

2.1.4. Indicator Normalization

To eliminate the impact of different physical dimensions among indicators on the calculation results, indicator normalization is performed. Suppose there are

m alternatives, each including

n indicators; then the eigenvalue matrix for the

n indicators is as follows:

where

is the

j-th indicator of the i-th alternative.

According to the following equation, the eigenvalue matrix X = (xij)m×n is normalized to obtain the normalized matrix R = (rij)m×n.

Higher-is-better indicators:

Lower-is-better indicators:

where

rij denotes the normalized indicator value of the

j-th indicator for the i-th alternative;

represents the maximum eigenvalue of indicator

j in the overall set;

denotes the minimum eigenvalue of indicator

j in the overall set. Handling of constant columns: If all values of the

j-th indicator across all alternatives are identical (i.e.,

), the denominator in Equations (13) and (14) becomes zero, leading to undefined results. For such cases, the normalized value of the

j-th indicator for all alternatives is uniformly set to

. This handling is based on two rationales: (1) A constant indicator means it has no discriminatory power among alternatives (all schemes perform equally well in this dimension), so assigning a uniform minimum normalized value 0 avoids distorting the comprehensive evaluation; (2) This method maintains consistency with the normalization interval [0, 1] and does not affect the relative weight of other discriminatory indicators in the objective function calculation. These normalization equations (Equations (13) and (14)) are derived based on the classic linear normalization logic, adapted to the study’s multi-objective evaluation needs. They eliminate dimensional differences among indicators while preserving the relative order of performance, which is consistent with the core requirements of complex water network scheduling evaluation.

2.2. Indicator Weights

Weight coefficient determination can be achieved through subjective weighting methods and objective weighting methods. This study adopts the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) among subjective weighting methods to determine the indicator weights of the optimization model, fully considering expert opinions and the role of each indicator in practical scheduling to make the results more in line with practical scenarios.

2.3. Objective Functions

The objectives of joint water resources scheduling in complex water networks typically cover multiple dimensions, such as flood control, water supply, environment, ecology, society, and economy. The incommensurability and conflicting nature among these objectives are the core characteristics of adaptive water resources scheduling problems. To balance and coordinate the relationships between different objectives, two common processing methods are adopted: one is to construct a multi-objective optimal scheduling model based on different objectives, obtain a non-inferior solution set by solving the model, and then select the optimal solution from the set using decision-making methods; the other is to assign differentiated weights to different objectives and convert the multi-objective problem into a comprehensive single-objective optimization problem through methods such as linear weighting. In view of the complexity of each objective, the second processing method is adopted in this study.

The objective function of the water resources scheduling model can be written as:

where

f1,

f2 and

f3 respectively correspond to the objective areas of flood control, water supply, and aquatic ecological environment;

,

and

are the weights of decision variables for the objective areas of flood control, water supply, and water environment, respectively.

(1) Objectives of flood control

(2) Objectives of water supply

(3) Objectives of aquatic ecological environment

The overall objective function (Equation (15)) is originally constructed to integrate the three core objective domains (flood control, water supply, aquatic ecological environment). It adopts a linear weighting approach tailored to the dynamic scheduling characteristics of the Taihu Lake Basin, converting multi-objective optimization into a solvable single-objective problem [

21]. The sub-objective functions (Equations (16)–(18)) are derived by quantifying the key evaluation indicators (

Section 2.1) and aligning with practical scheduling priorities, ensuring the model’s relevance to engineering operations [

12,

22,

23].

2.4. Constraint Conditions

The constraint conditions of the water resources scheduling model cover seven key aspects: water balance constraints, water level constraints, flow rate constraints, flow velocity constraints, water quality constraints, water quality balance constraints, and engineering operation constraints. Detailed descriptions are as follows:

(1) Water balance constraints

For key units of the water resources system (e.g., reservoirs, pumping stations, sluices), the water balance relationship must be satisfied in any time period t. Specifically, the inflow volume of the n-th unit during period t equals the sum of the outflow volume, the change in storage capacity (difference between the end-of-period and start-of-period storage capacities of the n-th unit in period t), and the water loss within the unit during period t.

(2) Water level constraints

The water level of units such as reservoirs and river channels must comply with specific minimum and maximum limits in different periods. These limits are formulated to meet multi-dimensional needs including flood control, water supply, navigation, and ecological protection, ensuring the safe and effective operation of the water system. For the n-th unit in period t, its actual water level must be within the range defined by the allowable minimum and maximum water levels.

(3) Flow rate constraints

In addition to water level constraints, units such as reservoirs, sluices, turbines, and key river sections are subject to flow rate limits in different periods. These constraints are primarily determined by factors such as pre-established scheduling rules and inherent engineering characteristics (e.g., structural design parameters). For the n-th unit in period t, the actual flow rate must be bounded by the allowable minimum and maximum flow rates.

(4) Flow velocity constraints

Flow velocity constraints apply to units including river representative sections and flow channels of water conservancy projects. To ensure ecological health (e.g., maintaining suitable habitat conditions for aquatic organisms) and engineering safety (e.g., preventing channel scouring or silting), the flow velocity of the n-th unit in period t must be maintained within the range of allowable minimum and maximum flow velocities.

(5) Water quality constraints

Key water quality indicators (e.g., NH3-N, DO, TP, COD) of each unit must meet the preset minimum water quality standards. For the n-th unit in period t, the concentration of each water quality indicator must not be lower than the specified minimum target value, ensuring compliance with water use requirements (e.g., drinking water supply, ecological base flow) and environmental regulations.

(6) Water quality balance constraints

This constraint is quantitatively described by a coupled water quantity and quality model. It reflects the dynamic balance between water quality indicators of the unit and key processes such as inflow/outflow transport, pollutant generation, and transformation within the unit over different time periods, ensuring the consistency of water quality simulation results with actual environmental processes.

(7) Engineering operation constraints

This category mainly includes constraints related to the operational performance and scheduling modes of numerous water conservancy projects. Specific constraints include, but are not limited to, the maximum water-carrying capacity of engineering structures (e.g., sluice gate opening limits, pumping station capacity constraints), fixed scheduling operation protocols (e.g., priority of water supply over ecological water release), and safety operation thresholds (e.g., maximum allowable operational duration of pumping units).

2.5. Optimization Method

An alternative optimization model based on the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm is adopted to optimize the set of scheduling alternatives, with the optimization process relying on the simulation results of water quantity and water quality.

4. Conclusions

This study focuses on the core demand of multi-objective coordinated scheduling in complex water networks, systematically constructing a complete technical system including indicator system, weighting strategy, model construction, and case verification. The main conclusions are as follows:

4.1. Construction of a Comprehensive Multi-Objective Indicator System

The established indicator system covers three key areas of flood control, water supply, and aquatic ecological environment, with 12 specific indicators such as drainage efficiency (DS), exceedance risk of guaranteed water level (CB), water supply efficiency (η), and ecological water level guarantee rate (PW). These indicators follow the principles of systematicness, conciseness, and independence, comprehensively reflecting the multi-dimensional scheduling needs of complex water networks and laying a foundation for quantitative coordination of conflicting objectives.

4.2. Effectiveness of the Dynamic Variable Weighting Strategy

By adopting the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) combined with dynamic weighting adjustment, the study realizes adaptive conversion of multi-objective problems under different hydrological scenarios (flood control period, water supply period, etc.). This method not only avoids subjective bias in traditional fixed weighting but also solves the incommensurability among indicators with different physical dimensions, significantly improving the scientificity and practical operability of scheduling decisions.

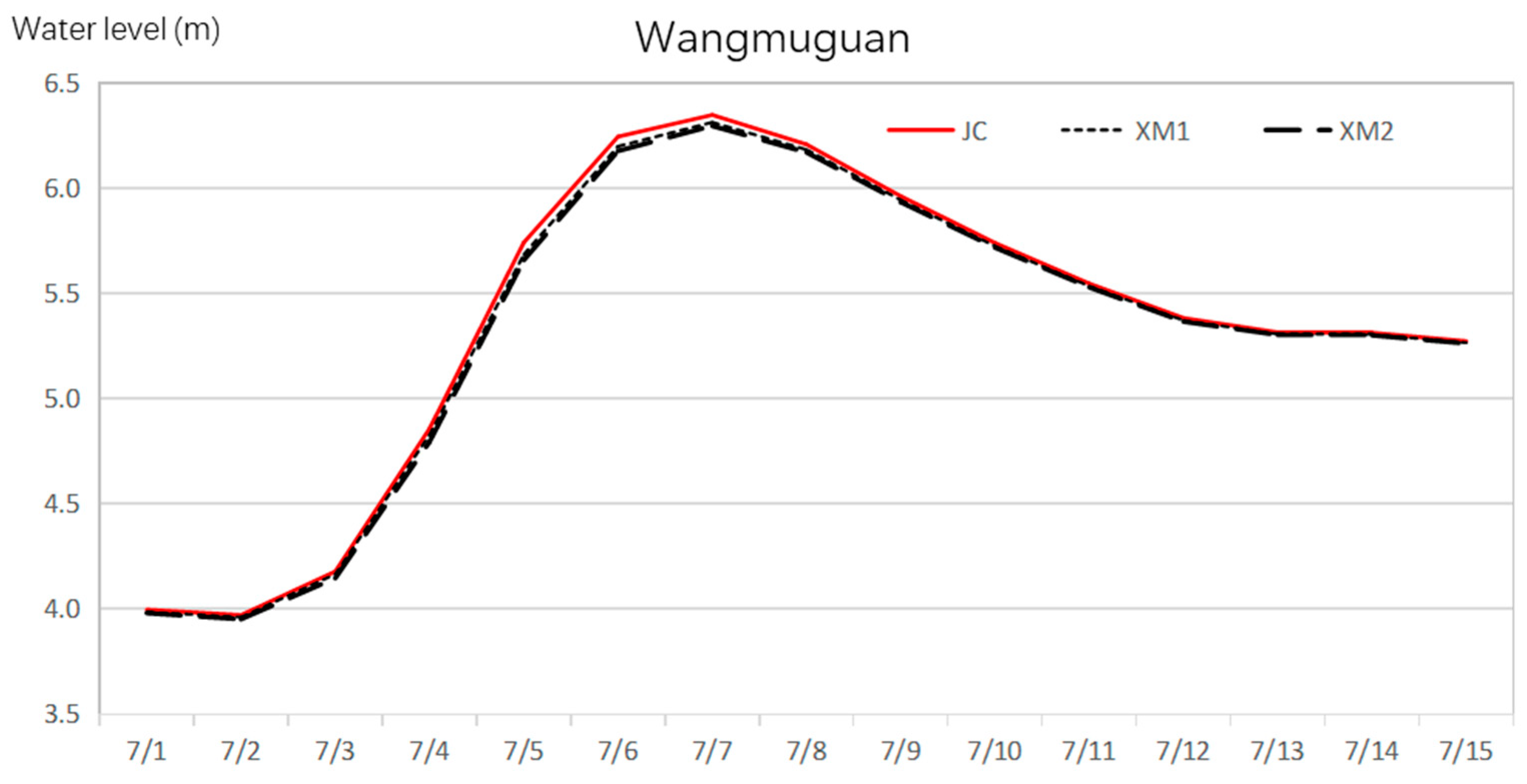

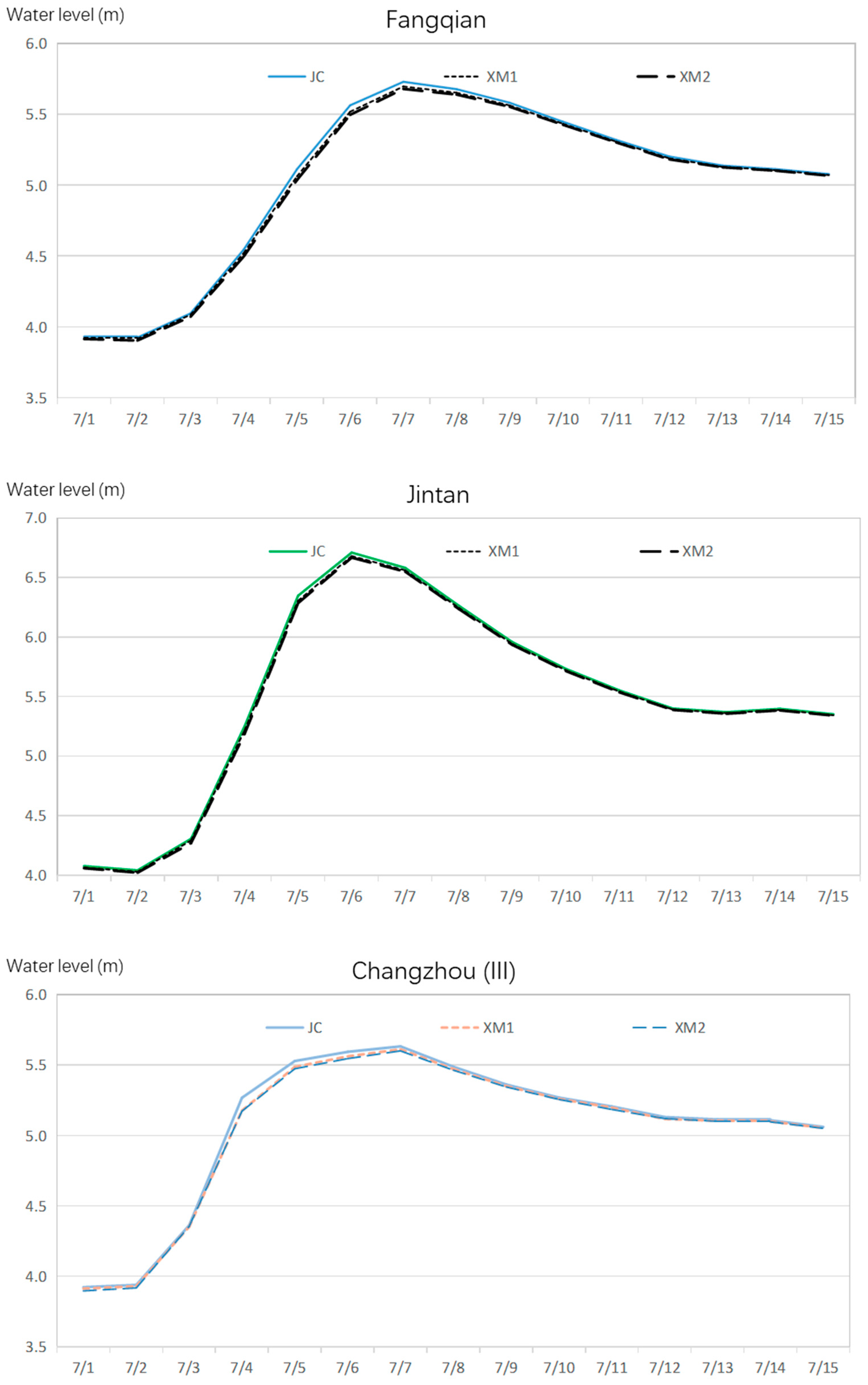

4.3. Optimal Scheduling Scheme Verified by Case Study

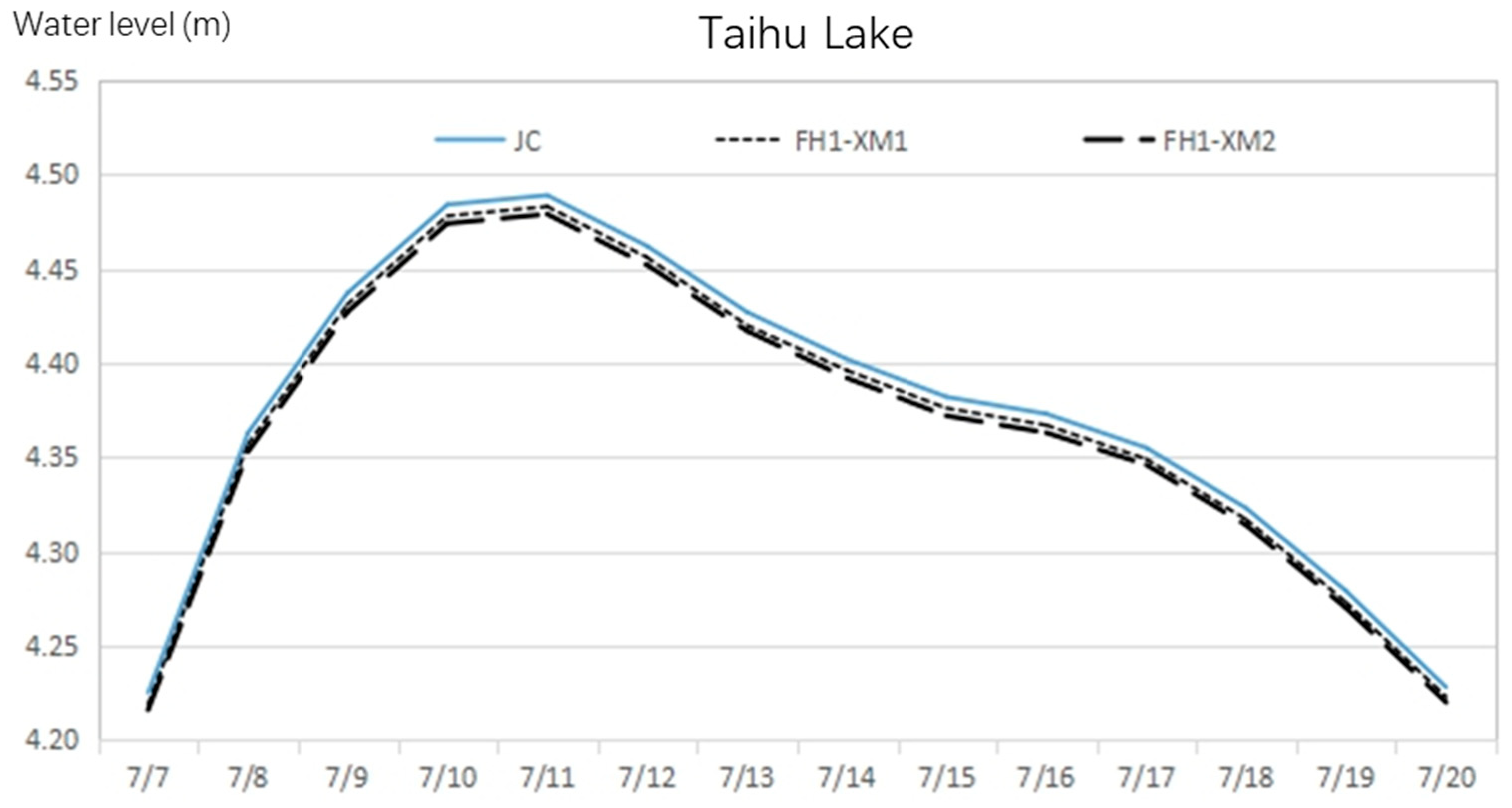

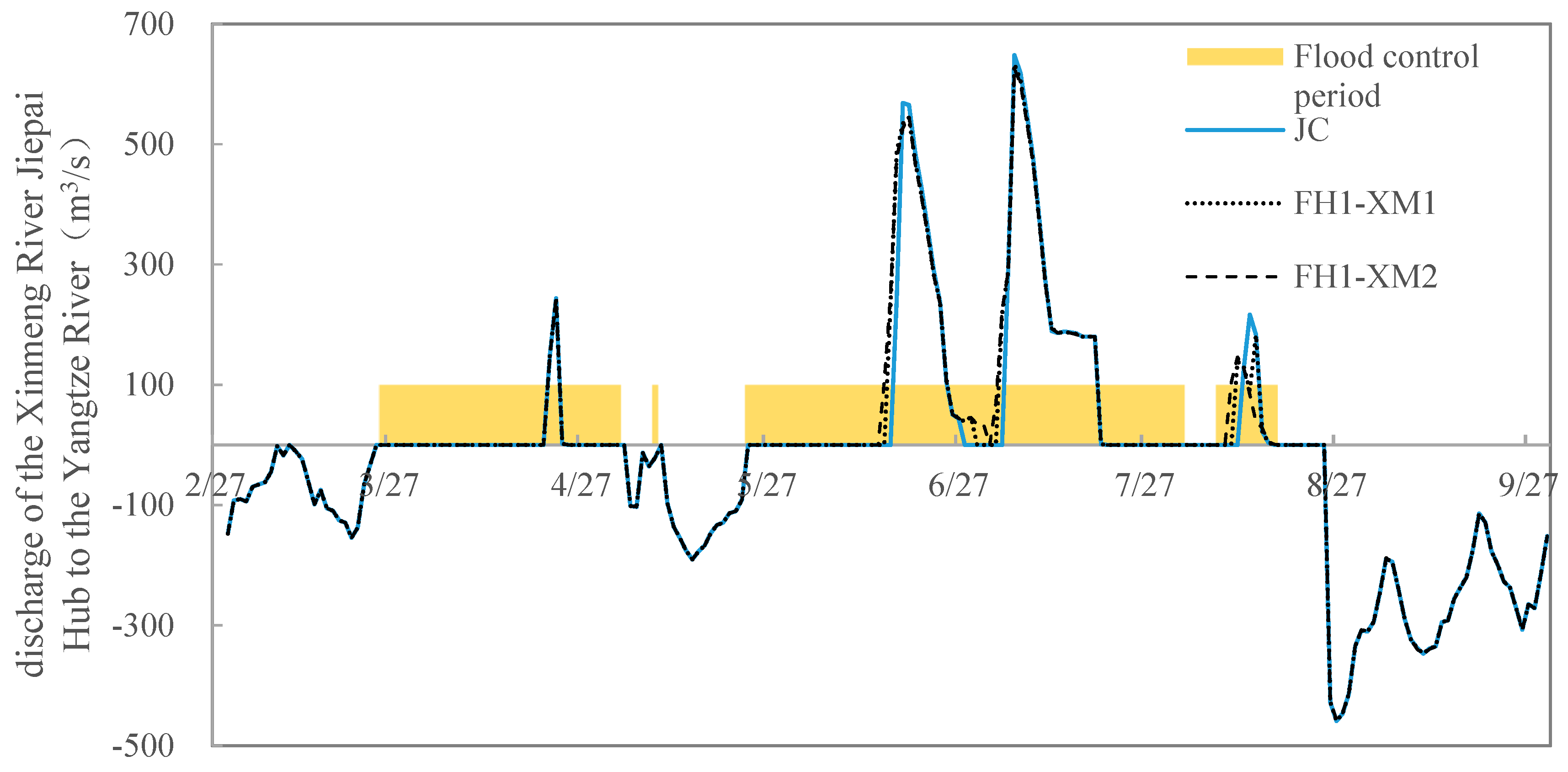

Under the 1991-Type 100-Year Return Period Rainfall scenario, the FH1-XM2 scheme is identified as the optimal enhanced discharge scheme. It effectively increases the drainage volume of the Xinmeng River Project and the western lake area (the flood season discharge volume to the Yangtze River increases by 0.71 × 100 million m3 and 0.40 × 100 million m3 respectively), reduces regional and Taihu Lake water levels, and lowers the basin’s flood control risk. The scheme’s advantages in key indicators such as drainage efficiency (0.92) and regional outflow coefficient (0.92) fully demonstrate the practical effect of the scheduling model.

4.4. Research Contributions and Prospects

This study breaks through technical bottlenecks in complex water network scheduling such as intricate hydraulic connections, numerous conflicting objectives, and heavy computational loads. The integrated technical process of “indicator system construction—dynamic weighting transformation—combined model solving” provides a new paradigm for multi-objective coordinated water resources scheduling, with its feasibility and effectiveness verified by the Taihu Lake Basin case study. However, this study is limited to the Taihu Lake Basin and the 1991-Type rainfall scenario; future research can expand to other complex water network basins, incorporate more extreme hydrological scenarios (e.g., extreme droughts), and optimize the algorithm to improve the model’s adaptability and solution efficiency. Additionally, integrating socio-economic factors such as water use costs and benefit allocation will further enhance the model’s practical application value.