Abstract

The Tibetan Plateau (TP), known as the “Asian Water Tower,” plays a critical role in regional and global climate systems. However, water resource sustainability is increasingly threatened under climate change and growing demand. While moisture transport mechanisms for summer monsoon and extreme precipitation events have been widely studied, the understanding of moisture sources for different precipitation intensities remains limited. This study employs the Lagrangian-based HYSPLIT model to quantify moisture source contributions to three types of precipitation events—extreme precipitation (EP), moderate precipitation (MP), and light precipitation (LP)—over the TP from 1979 to 2020. Using trajectory clustering and moisture source diagnostics, we identify dominant transport pathways and their relative contributions. Results show that EP and MP events are primarily influenced by the Indian monsoon, with the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea as key sources, while LP events are dominated by westerlies. The western pathway contributes 15.55%, 36.28%, and 59.59% to EP, MP, and LP events, respectively, whereas the monsoon pathway accounts for 40.56%, 28.23%, and 31.21%. External moisture sources dominate across all event types (average 87.7%), with local recycling contributions decreasing from LP (12.90%) to EP (11.55%). These findings enhance the understanding of moisture–precipitation coupling mechanisms over the TP and provide a scientific basis for water resource management under changing climate conditions.

1. Introduction

The Tibet Plateau (TP, with an average altitude > 4000 m) is the largest and highest plateau in the world, and its thermal and dynamic effects profoundly regulate the regional and even global climate system [1,2,3,4]. The TP is known as the “Asian Water Tower”, nurturing major Asian rivers such as the Yangtze River, the Yellow River, the Yarlung Zangbo River, and the Indus River, providing water resource security for approximately 1.4 billion people worldwide [5]. In recent years, under the dual pressures of climate change and the sharp increase in water demand, the problem of basin-wide water resource shortage has become increasingly prominent [6,7,8,9], threatening the sustainability of the Asian Water Tower [10]. Against this backdrop, the study of the plateau’s water cycle process, especially the multi-scale moisture transport–precipitation coupling mechanism, has become a frontier hotspot in the interdisciplinary field of climatology and hydrology [11,12,13].

While recent studies on moisture transport characteristics over the TP have profoundly advanced our understanding of the plateau precipitation’s origin and evolution [14], current research has predominantly concentrated on events linked to the summer monsoon and extreme precipitation. Analysis of atmospheric moisture transport for summer precipitation in the southeastern TP (1979–2002) by Lei Feng et al. revealed that the predominant climatic moisture sources are the Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal, and mid-latitude regions [15]. Chen et al. [16] employed a Lagrangian approach to demonstrate that the moisture sources for the four subregions of the TP during the wet season (May–August) from 1980 to 2016 differ significantly in both spatial patterns and magnitude, which are predominantly modulated by the combined effects of the summer monsoon, local recycling processes, and the westerlies. Zhang et al. [17] employed a combined clustering algorithm and Lagrangian moisture source diagnosis to identify major moisture transport pathways during the rainy season in the Sanjiangyuan region and quantify their contributions to extreme precipitation and moderate precipitation events. Their study revealed the critical role of the northwestern pathway and the southern China pathway, with the northwestern pathway contributing 18.4% and 32.2% to extreme precipitation and moderate precipitation events, respectively, while the southern China pathway contributed 25.9% and 28.5% to extreme precipitation and moderate precipitation events, respectively. Ayantobo et al. [18] analyzed 23 extreme precipitation events over the TP from 1951 to 2015 using a Lagrangian trajectory model (HYSPLIT). Their findings indicated that all these events were concentrated in the southern foothills of the plateau, with moisture transport originating from the Arabian Sea identified as the dominant source. Wang Meiyue et al. [19] investigated two extreme precipitation events in the Sanjiangyuan region and identified two dominant moisture transport pathways: the southwestern path, which carries moisture from the Bay of Bengal to the rainfall area via the Brahmaputra Gorge moisture channel, and the southeastern path, which transports moisture from the East China Sea and South China Sea northwestward through areas such as Guangdong and Hunan to the rainfall zone.

Current consensus indicates that precipitation of varying intensities is governed by distinct moisture transport processes [19]. However, research on moisture transport characteristics associated with different rainfall intensities over the TP remains insufficient, with most studies focusing predominantly on the rainy season and extreme precipitation events. To address this gap, this study employs a Lagrangian approach using the HYSPLIT model to trace moisture trajectories and quantify source contributions for extreme precipitation (EP), moderate precipitation (MP), and light precipitation (LP) events over the TP from 1979 to 2020. By integrating trajectory clustering and moisture source diagnostic techniques, this work aims to identify dominant moisture transport pathways for different types of precipitation, quantify the relative contributions of local and remote moisture sources, and assess the synergistic effects of the Indian monsoon, westerly circulation, and local moisture recycling on precipitation over the plateau. Section 2 describes the study area, datasets, classification of precipitation events, and trajectory analysis methods. Section 3 (Results and Discussion) presents the moisture trajectory distributions, key transport pathways, and their quantitative contributions for different intensity precipitation events. Section 4 (Conclusions) will provide the core findings and summary of this research.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Study Area

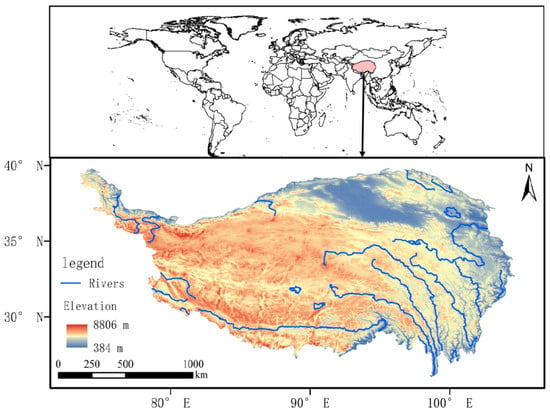

The TP, spanning a vast territory in western China, is bordered to the south by the southern foothills of the Himalayas, adjacent to India, Nepal, and Bhutan. To the north, it extends to the northern edges of the Kunlun Mountains, Altun Mountains, and Qilian Mountains, connecting with the Tarim Basin and Hexi Corridor in the arid desert region of Central Asia. Its western boundary comprises the Pamir Plateau and Karakoram Mountains, bordering Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the Kashmir region (disputed territory). To the east, it is demarcated by the southern or eastern foothills of the Yulong Snow Mountain, Daxue Mountain, Jiajin Mountain, Qionglai Mountains, and Minshan Mountain.

Geographically spanning 25°59′37″ N to 39°49′33″ N latitude and 73°29′56″ E to 104°40′20″ E longitude (Figure 1), the plateau has a total perimeter of 11,745.96 km and covers an area of 2542.30 × 103 km2 [20]. It encompasses 32 prefecture-level cities and 198 counties across the provinces and autonomous regions of Tibet, Qinghai, Xinjiang, Gansu, and Sichuan.

Figure 1.

Topographical map of the TP.

2.2. Delineation of Precipitation Events

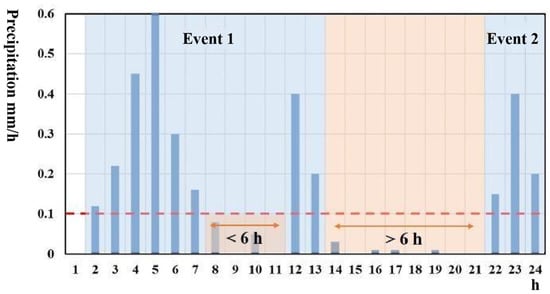

The most critical variable in delineating precipitation events is the minimum inter-event dry period. In this study, the commonly used 6 h threshold method was employed to identify precipitation events. A precipitation event is considered to occur when rainfall intensity exceeds 0.1 mm/h and the cumulative precipitation surpasses 0.1 mm per event. The event is deemed concluded when precipitation intensity remains below 0.1 mm/h for over 6 consecutive hours [21]. The computational methodology is illustrated in Figure 2. The ERA5 reanalysis precipitation data used in this research features a temporal resolution of 1 h, which adequately meets the temporal requirements for precipitation event identification. In this study, a total of 42 years of precipitation events over the TP from 1979 to 2020 were analyzed.

Figure 2.

Delineation of precipitation events delineation process.

2.3. Definition of Three Types of Precipitation Event Intensity Classes

The percentile threshold method recommended by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and widely applied in climatology was adopted to statistically classify regional precipitation events. Three types of precipitation events are classified as follows: (1) EP events, total event precipitation exceeding the 95th percentile threshold for the TP. (2) MP events, total event precipitation between the 25th and 70th percentiles. (3) LP events, total event precipitation below the 5th percentile.

2.4. Trajectory Generation Description and Trajectory Clustering Method

This study utilizes the HYSPLIT model, developed by Draxler and Hess [22,23], to simulate air parcel trajectories and analyze moisture transport. The model is driven by NCEP data in an HYSPLIT-compatible format. Given that atmospheric moisture density exhibits a rapid decrease with altitude, the majority of the moisture is confined to the layer below 5 km [24], a release grid (1° × 1°), clipped to the regional boundary, was defined with 10 vertical levels spanning 0–5 km above ground level (AGL) at 0.5 km intervals to initiate the trajectories. Backward trajectory simulations were conducted with a duration of 240 h, consistent with the average atmospheric moisture residence time [25,26]. Each simulation was initiated at the start time of a respective precipitation event. The output parameters, recorded at hourly intervals, included latitude, longitude, height, pressure, specific humidity, and mixed-layer depth. The total number of trajectories generated for the three precipitation types is presented in Table 1. It is important to note that not all trajectories contribute moisture to the target area. In this study, a trajectory is classified as a valid moisture trajectory only if it exhibits a statistically significant (p < 0.05) negative trend in specific humidity while over the target region [17].

Table 1.

Percentiles used to identify three types of precipitation events, number of events, numbers of generated trajectories, and valid trajectories.

Although the built-in HYSPLIT clustering method is based on K-Means, it cannot cluster trajectories originating from distinct starting points [27]. This study achieves the clustering of trajectories from different starting points using the K-means method, where the optimal number of clusters (N) was determined through a two-step procedure: first, identifying the candidate range via the elbow point in the average spatial deviation curve, and then selecting the final N as the value yielding the maximum silhouette coefficient [28], See Appendix A.

2.5. Methods for Moisture Source Attribution, Moisture Path Frequency Calculation, and Average Path Humidity Determination

Moisture sources were diagnostically identified following the principles outlined in the S08 and SW14 methods [29,30], which are designed to estimate the contribution of moisture from various source regions to precipitation in the target area. For a detailed description of the specific computational procedures and implementation, refer to Kang [13].

The frequency Fij for a given grid cell (i, j) is calculated as the ratio of valid trajectories passing through it to the total number of valid trajectories, following Equation (1). This dimensionless metric serves as an indicator of pathway importance, with a higher Fij value denoting a more frequented moisture corridor.

The grid-specific average specific humidity , derived from Equation (2), quantifies the mean moisture burden of trajectories traversing each cell. Thus, a higher directly indicates that the prevailing air masses are moisture-rich.

where Fij is the trajectory passage frequency for the grid cell (i, j); L is the total number of valid trajectories; M is the count of valid trajectories passing through the grid cell (i, j); is the average specific humidity at the grid cell (i, j); and qijn is the specific humidity of the n-th trajectory passing through the grid cell (i, j).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Precipitation Event Characteristics

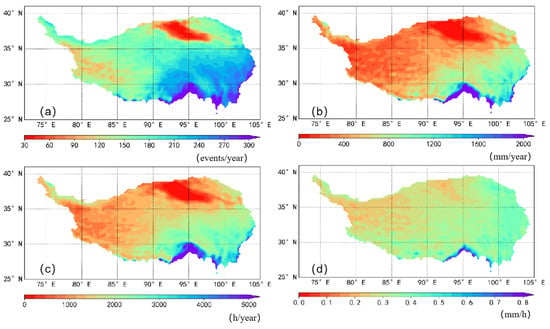

The spatial distributions of key climatological characteristics of precipitation events—including the mean annual frequency, total precipitation amount, total duration, and mean intensity—are analyzed and presented in Figure 3. Spatially, all four metrics exhibit a pronounced decreasing gradient from the southeastern to the northwestern Tibetan Plateau. High-value zones are consistently concentrated in the southeastern sector, while the Qaidam Basin stands out as a distinct low-value center.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of event-based precipitation characteristics over the Tibetan Plateau (1979–2020). (a) Mean precipitation events (events/year), (b) total precipitation (mm/year), (c) total precipitation duration (h/year), and (d) mean precipitation intensity (mm/h).

Quantitatively, the mean annual frequency of events ranges from 20 to 400 across the plateau. Correspondingly, the total annual precipitation amount varies between 200 and 2000 mm, and the total annual duration spans from 200 to 5000 h. The mean precipitation intensity shows a range of 0.1 to 0.8 mm/h. Notably, the intensity distribution is not merely a southeast–northwest gradient. The Qilian Mountains in the north exhibit higher intensity than other regions at similar latitudes, highlighting the orographic enhancement of precipitation intensity in mountainous areas compared to basins and plains. Overall, the highest precipitation intensities are predominantly clustered in the southeastern part of the plateau.

3.2. Classification of Events and Valid Trajectory Statistics

Based on precipitation intensity thresholds, precipitation events over the Tibetan Plateau from 1979 to 2020 were categorized into 48,587 extreme events, 545,673 moderate events, and 54,091 light precipitation events. Subsequently, backward trajectories were simulated for each event using the HYSPLIT model, initiating from 10 different vertical levels. This process generated 485,870, 5,456,730, and 540,910 initial trajectories, corresponding to the three event types. Following the application of a validity filter to identify moisture-yielding paths, the final sets of valid moisture trajectories for the extreme, moderate, and light events were determined to be 160,168, 1,322,739, and 140,048, respectively. The counts of these valid moisture trajectories for each precipitation type are summarized in Table 1.

3.3. Frequency of the Moisture Paths

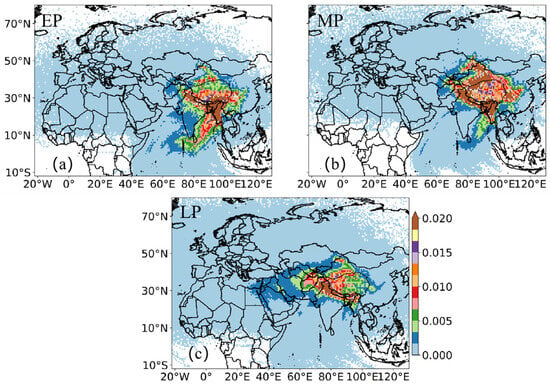

The frequency distributions of moisture trajectories for different precipitation types are presented in Figure 4a–c. Moisture reaching the target region primarily originates from four source regions: northwestern Eurasia, the Arabian Sea/Indian Peninsula influenced by cross-equatorial flows, the Bay of Bengal, and southern/southeastern China, including the South China Sea.

Figure 4.

The frequency of the valid trajectories in the (a) EP, (b) MP, and (c) LP events. The frequency at a grid point is defined as the ratio of the number of effective trajectories passing through it to the total number of effective trajectories (dimensionless).

During extreme precipitation (EP) events, trajectories from the Arabian Sea/Indian Peninsula and the Bay of Bengal exhibit notably high frequencies, underscoring their critical role in moisture supply to the Tibetan Plateau. This pattern is attributed to the concentration of EP in summer, when monsoon circulation efficiently transports oceanic moisture inland.

In the moderate precipitation (MP) events, high-frequency moisture pathways are not only prominent over the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal but also extend to continental interiors such as northwest China and south China. This spatial diversity stems from the fact that MP events occur across multiple seasons, leading to a broader spectrum of moisture sources.

In contrast, the light precipitation (LP) events are predominantly governed by the westerlies, with moisture mainly sourced from western and central Asia.

3.4. Major Moisture Transport Path Groups

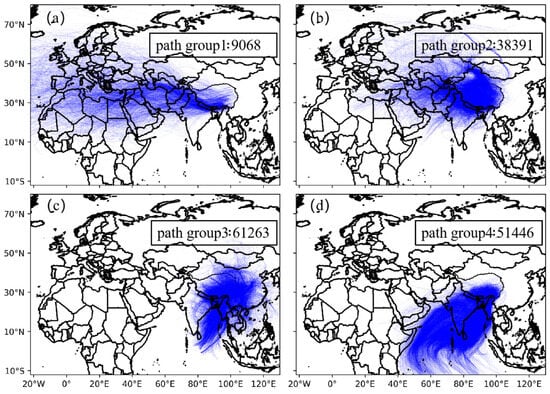

Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the clustering results of moisture trajectories. There are four path groups for each event. In the EP events, the four key moisture transport path groups exhibit significant directional differences. Path group 1 is the Far-Western Path group (Figure 5a), which transports moisture along the westerlies to the TP, this path group comprises 9068 trajectories, accounting for 5.66% of all trajectories associated with EP events. Path group 2, the Near-Western Path group (Figure 5b), primarily covers western Siberia, Central Asia, and northwestern China, containing 38,391 trajectories that represent 23.97% of the total. Path group 3 is the Eastern China Path group (Figure 5c), predominantly covering eastern China and the Bay of Bengal, with 61,263 trajectories constituting 38.25% of all extreme precipitation trajectories. Path group 4 represents the Arabian Sea and partial Bay of Bengal cluster (Figure 5d); characterized by moisture transport through the Indian Peninsula northward to the TP, this path group includes 51,446 trajectories, representing 32.12% of the total EP trajectories.

Figure 5.

The clustering results of moisture trajectories for the EP events. The blue lines represent trajectories. (a) Path group 1 (the Far-Western Path group), comprising 9068 valid trajectories. (b) Path group 2 (the Near-Western Path group), comprising 38,391 valid trajectories. (c) Path group 3 (the Eastern China Path group), comprising 61,263 valid trajectories. (d) Path group 4 (the Arabian Sea and partial Bay of Bengal Path group), comprising 51,446 valid trajectories.

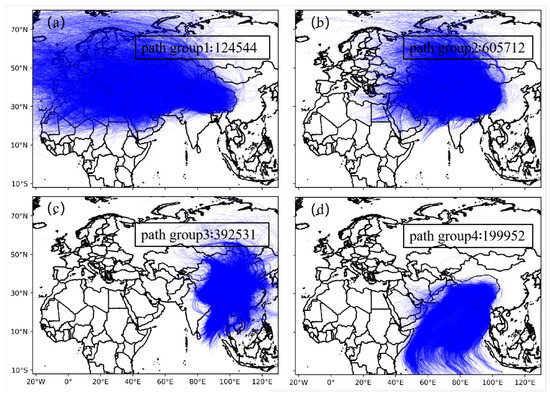

Figure 6.

The clustering results of moisture trajectories for the MP events. The blue lines represent trajectories. (a) Path group 1 (the Far-Western Path group), comprising 124,544 valid trajectories. (b) Path group 2 (the Near-Western Path group), comprising 605,712 valid trajectories. (c) Path group 3 (the Eastern China Path group), comprising 392,531 valid trajectories. (d) Path group 4 (the Arabian Sea and partial Bay of Bengal Path group), comprising 199,952 valid trajectories.

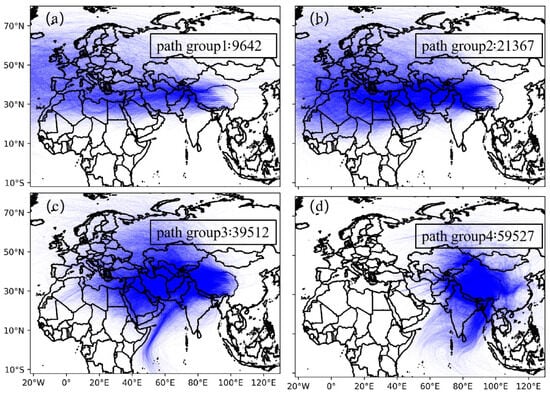

Figure 7.

The clustering results of moisture trajectories for the LP events. The blue lines represent trajectories. (a) Path group 1 (the Far-Western Path group), comprising 9642 valid trajectories. (b) Path group 2 (the Near-Western Path group), comprising 21,367 valid trajectories. (c) Path group 3 (the Eastern China Path group), comprising 39,512 valid trajectories. (d) Path group 4 (the Arabian Sea and partial Bay of Bengal Path group), comprising 59,527 valid trajectories.

In the MP events, Path group 1 is the Far-Western Path group (Figure 6a), which transports moisture along the westerlies to the TP. This path group comprises 124,544 trajectories, accounting for 10.90% of all trajectories associated with MP events. Path group 2, the Near-Western Path group (Figure 6b), primarily covers western Siberia, Central Asia, and northwestern China, containing 605,712 trajectories that represent 53.01% of the total. Path group 3 is the Eastern China Path group (Figure 6c), predominantly covering eastern China, with 392,531 trajectories constituting 34.35% of all MP trajectories. Pathway 4 represents the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal cluster (Figure 6d), characterized by moisture transport through the Indian Peninsula northward to the TP, this pathway includes 199,952 trajectories, representing 1.75% of the total MP trajectories.

In the LP events, Path group 1 (Figure 7a), Path group 2 (Figure 7b), and Path group 3 (Figure 7c) contain 9642, 21,367, and 39,512 trajectories, respectively, accounting for 7.41%, 16.43%, and 30.38% of all trajectories associated with LP events. The peripheral regions of the TP and Bay of Bengal cluster (Figure 7d) comprise 59,527 trajectories, representing 45.77% of total LP trajectories.

Clustering analysis of atmospheric moisture transport trajectories over the TP under different precipitation intensities reveals two principal path groups. The Western Path group (combining the Near-Western and Far-Western routes) along the westerlies accounts for 29.63%, 63.90%, and 54.23% of all trajectories in EP, MP, and LP events, respectively. The Indian Monsoon Path group, originating from the Bay of Bengal–Arabian Sea sector, constitutes 32.12%, 36.10%, and 45.77% of total trajectories across EP, MP, and LP events, correspondingly.

3.5. Quantitative Importance of Major Moisture Transport Path Groups

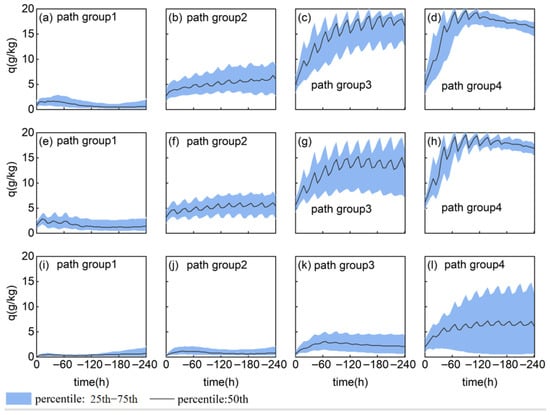

Changes in specific humidity along the trajectories reflect the net effect of moisture depletion through precipitation and replenishment via evaporation. As shown in Figure 8, the distinct moisture evolution patterns for each cluster indicate that many air masses experience a complex interplay of these processes before reaching the target region.

Figure 8.

The specific humidity of different moisture path groups for the TP. (a∓d) EP events; (e∓h) MP events; (i–l) LP events.

Figure 8a–d illustrate the along-track specific humidity variations in different path groups during EP events. During the 0–6 h period preceding precipitation onset, Path group 1 released 4849.2 g kg−1 (6 h)−1 of moisture, while Path group 2, 3, and 4 discharged 29,362.3, 96,525.2, and 89,200.8 g kg−1 (6 h)−1, respectively.

Figure 8e–h depict analogous variations for MP events, with moisture release quantities of 21,713.0 g kg−1 (6 h)−1 (Path group 1), 205,282.7 g kg−1 (6 h)−1 (Path group 2), 222,021.2 g kg−1 (6 h)−1 (Path group 3), and 176,641.0 g kg−1 (6 h)−1 (Path group 4).

Figure 8i–l characterize LP events, showing moisture contributions of 2923.1 g kg−1 (6 h)−1 (Path group 1), 8450.3 g kg−1 (6 h)−1 (Path group 2), 19,945.7 g kg−1 (6 h)−1 (Path group 3), and 46,186.1 g kg−1 (6 h)−1 (Path group 4) during the critical 6 h pre-precipitation phase.

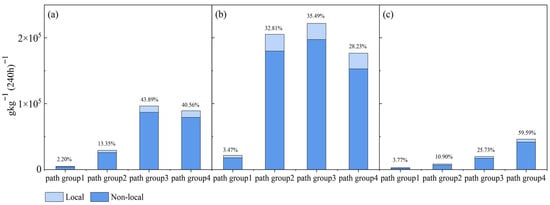

Source apportionment, as presented in Figure 9, quantifies the moisture contributions from different path groups by categorizing uptake into non-local and local sources. The total moisture release attributed to all major path groups is calculated as 415,106.09, 625,657.9, and 77,505.2 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1 for the three precipitation types, respectively.

Figure 9.

Quantified moisture release [g kg−1 (240 h)−1] attributed to various path groups for (a) EP, (b) MP, and (c) LP events. Values above bars denote the contribution of each category to the total. “Non-local” and “Local” labels classify the source origin as outside or inside the target region, respectively.

Figure 9a shows the moisture release amounts from local and non-local regions along different moisture transport paths for the EP events over the TP. Path 1, local and non-local moisture release is 946.90 and 15,627.27 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Path 2, local and non-local moisture release is 13,402.80 and 73,838.22 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Path 3, local and non-local moisture release is 23,502.41 and 198,587.69 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Path 4, local and non-local moisture release is 10,097.07 and 79,103.73 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Local and non-local moisture uptake contribute 11.55% and 88.45%, respectively.

Figure 9b shows the moisture release amounts from local and non-local regions along different moisture transport paths for the MP events over the TP. Path 1, local and non-local moisture release is 3979.52 and 17,733.48 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Path 2, local and non-local moisture release is 25,379.94 and 179,902.76 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Path 3, local and non-local moisture release is 24,657.43 and 197,363.77 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Path 4, local and non-local moisture release is 23,800.13 and 152,840.87 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Local and non-local moisture uptake contribute 12.44% and 87.56%, respectively.

Figure 9c shows the moisture release amounts from local and non-local regions along different moisture transport paths for the LP events over the TP. Path 1, local and non-local moisture release is 928.02 and 1995.08 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Path 2, local and non-local moisture release is 1735.36 and 6714.94 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Path 3, local and non-local moisture release is 2767.89 and 17,177.81 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Path 4, local and non-local moisture release is 4564.50 and 41,621.60 g·kg−1·(240 h)−1. Local and non-local moisture uptake contribute 12.90% and 87.10%, respectively.

3.6. Discussion

The direction of clustered transport path groups. This study employed the K-Means clustering method recommended by the HYSPLIT model, which is designed specifically for clustering trajectories sharing identical starting points. When applying this method to cluster a large number of trajectories with distinct starting points, trajectories exhibiting shorter paths tend to be grouped into the same cluster. This results in clustered trajectories exhibiting poorly defined directionality, as illustrated in Figure 5a,b, Figure 6a,b and Figure 7a,b, both the Far-Western and Near-Western Path groups, which inherently follow the westerly flow, were erroneously clustered into two separate groups due to this methodological limitation. We propose that incorporating directional information from the trajectory front position and establishing a corresponding weighting factor could mitigate the excessive influence of the trajectory’s latter segments on the clustering outcome. This approach warrants further investigation.

The development of atmospheric water resources over the TP presents both significant potential and complex challenges. Many studies have based their assessment of this development merely on the distribution of water vapor flux over the plateau, ignoring the constraints imposed by water vapor transport characteristics on its feasibility [31,32]. Future research concerning atmospheric water resource development should systematically establish a comprehensive evaluation framework that integrates both water vapor flux distribution and transport characteristics [33].

4. Conclusions

In this study, we adopted the HYSPLIT model to simulate the main water transport pathways of three continuous precipitation types (EP, MP, and LP) over the TP, and quantified their contributions to precipitation using the Lagrangian moisture source diagnostic method, which was originally developed by Sodemann et al. (2008) [29] and modified by Sun and Wang (2014) [30].

Based on a comprehensive analysis of moisture transport pathway identification and source region diagnostics, this study reveals the moisture transport characteristics and their contributions to different precipitation types over the TP. The main findings are as follows: (1) Trajectory frequency analysis demonstrates that EP and MP events are predominantly controlled by the Indian monsoon system, while LP events are mainly influenced by the westerlies. (2) Trajectory clustering identifies two stable moisture transport pathways: the westerlies-dominated western pathway (combined near-west and far-west routes) and the Indian monsoon-driven Bay of Bengal–Arabian Sea corridor. Quantitative assessment shows that the western pathway contributes 15.55%, 36.28%, and 59.59% to EP, MP, and LP events, respectively, whereas the monsoon pathway accounts for 40.56%, 28.23%, and 31.21% correspondingly. (3) Moisture attribution analysis reveals that external moisture sources dominate precipitation processes (average contribution: 87.7%), with local evaporation contributions exhibiting a decreasing gradient from LP (12.90%) to MP (12.44%) and EP (11.55%) events. Conversely, external moisture contributions display an inverse increasing trend across precipitation categories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K. and Y.S.; methodology, B.K.; software, B.K.; validation, B.K.; formal analysis, B.K., Y.S. and X.Z.; data curation, B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.; writing—review and editing, B.K., X.Z., Y.R. and J.H.; project administration, funding acquisition, X.Z., W.B. and B.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Qinghai University Research Ability Enhancement Project [Grant Nos. 2025KTST07]; Kunlun Talent, High-end Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talents Program of Qinghai Province; the National Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2022YFC3202400).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the approval process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TP | Tibetan plateau |

| EP | Extreme precipitation |

| MP | Moderate precipitation |

| LP | Light precipitation |

| No. of Traj. | Number of trajectories |

| No. of Valid Traj. | Number of valid trajectories |

| K | Number of clusters |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Silhouette coefficients for different numbers of clusters.

Table A1.

Silhouette coefficients for different numbers of clusters.

| Event | K = 2 | K = 3 | K = 4 | K = 5 | K = 6 | K = 7 | K = 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP | 0.3039 | 0.3111 | 0.3829 | 0.3480 | 0.3363 | 0.2929 | 0.2929 |

| MP | 0.3532 | 0.3813 | 0.3718 | 0.3414 | 0.3459 | 0.3021 | 0.2991 |

| LP | 0.3752 | 0.3638 | 0.3696 | 0.3682 | 0.3659 | 0.3129 | 0.3069 |

References

- Zhang, R.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, E. The impact of regional uplift of the Tibetan Plateau on the Asian monsoon climate. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2015, 417, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geen, R.; Lambert, F.H.; Vallis, G.K. The Asian Monsoons as a Unified System. ESS Open Arch. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geen, R.; Bordoni, S.; Battisti, D.S.; Hui, K. Monsoons, ITCZs, and the Concept of the Global Monsoon. Rev. Geophys. 2020, 58, e2020RG000700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Jiang, J.; Ma, T.; Mao, J.; Wu, G. The Tibetan Plateau bridge: Influence of remote teleconnections from extratropical and tropical forcings on climate anomalies. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 2024, 17, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Man, W.; Wang, S.; Esper, J.; Meko, D.; Büntgen, U.; Yuan, Y.; Hadad, M.; Hu, M.; Zhao, X. Southeast Asian ecological dependency on Tibetan Plateau streamflow over the last millennium. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Bolch, T.; Chen, D.; Gao, J.; Immerzeel, W.; Piao, S.; Su, F.; Thompson, L.; Wada, Y.; Wang, L. The Imbalance of the Asian water tower. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Long, D.; Scanlon, B.R.; Mann, M.E.; Li, X.; Tian, F.; Sun, Z.; Wang, G. Climate change threatens terrestrial water storage over the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Wen, J.; Masood, M.; Masood, M.U.; Adnan, M. Impacts of climate and land-use changes on hydrological processes of the source region of Yellow River, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolenaars, W.J.; Dhaubanjar, S.; Jamil, M.K.; Lutz, A.; Immerzeel, W.; Ludwig, F.; Biemans, H. Future upstream water consumption and its impact on downstream water availability in the transboundary Indus Basi. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 861–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lian, W.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, F. Status and problems of water resources on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Adv. Water Sci. 2023, 34, 812–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curio, J.; Maussion, F.; Scherer, D. A 12-year high-resolution climatology of atmospheric water transport over the Tibetan Plateau. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2015, 6, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, H.; Xu, M.; Zhao, C.; Zhong, L.; Li, R.; Fu, Y.; Gao, Y. Impacts of Topographic Complexity on Modeling Moisture Transport and Precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau in Summer. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 39, 1151–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Wei, J.; Ayantobo, O.O.; Yang, H. Determination of Transport Pathways and Mutual Exchanges of Atmospheric Moisture between Source Regions of Yangtze and Yellow River Basins. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI, H.; Xiaoduo, P. An overview of research methods on water vapor transport and sources in the Tibetan Plateau. Adv. Earth Sci. 2022, 37, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhou, T. Water vapor transport for summer precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau: Multidata set analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2012, 117, D20114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, W.; Yang, S.; Xu, X. Identifying and contrasting the sources of the water vapor reaching the subregions of the Tibetan Plateau during the wet season. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 53, 6891–6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhong, D. Major moisture pathways and their importance to rainy season precipitation over the Sanjiangyuan region of the Tibetan Plateau. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 6837–6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayantobo, O.O.; Wei, J.; Hou, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, G. Characterizing potential sources and transport pathways of intense moisture during extreme precipitation events over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Y.; Wang, L.; Li, X.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, X.Y. Study on water vapor transport source and path of rainstorm in Sanjiangyuan area. Plateau Meteorol. 2022, 41, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Zheng, D. Datasets of the boundary and area of the Tibetan Plateau. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2014, 69, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Pan, X.; Sun, L.; Yu, L. Influence of rainfall division method on capture ratio of rainfall. China Water Wastewater 2019, 35, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draxler, R.; Hess, G. Description of the HYSPLIT_4 Modeling System; NOAA Technical Memorandum ERL ARL 224; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA): Washington, DC, USA, 1997; 224p.

- Draxler, R.; Hess, G. An overview of the HYSPLIT_4 modelling system for trajectories, dispersion, and deposition. Aust. Meteorol. Mag. 1998, 47, 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, T.; Andreae, M.O.; Beirle, S.; Dörner, S.; Mies, K.; Shaiganfar, R. MAX-DOAS observations of the total atmospheric water vapour column and comparison with independent observations. Atmos. Mesa. Tech. 2013, 6, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K.E. Atmospheric Moisture Recycling: Role of Advection and Local Evaporation. J. Clim. 1999, 12, 1368–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K.E. Atmospheric Moisture Residence Times and Cycling: Implications for Rainfall Rates and Climate Change. Clim. Change 1998, 39, 667–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.D.; Stunder, B.J.B.; Rolph, G.D.; Draxler, R.R.; Stein, A.F.; Ngan, F. NOAA’s HYSPLIT Atmospheric Transport and Dispersion Modeling System. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 96, 2059–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of 146 cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1986, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodemann, H.; Schwierz, C.; Wernli, H. Interannual variability of Greenland winter precipitation sources: Lagrangian moisture diagnostic and North Atlantic Oscillation influence. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D03107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Wang, H. Moisture Sources of Semiarid Grassland in China Using the Lagrangian Particle Model FLEXPART. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 2457–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.F.; Zhao, K.; Lu, H.L.; Wang, G.Q.; Qiu, J. Modes of exploitation of atmospheric water resources in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 3237–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, P.; Jia, S.; Zhao, J.; Gao, L.; Liu, Z. Regional characteristics and exploitation potential of atmospheric water resources in China. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 3225–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, T.; Chen, C.; Su, Y.; Zhong, D.; Shao, S.; Wang, G. Azure water: The reference atmospheric water under non-precipitation condition [version 1]. Hydrosphere 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).