1. Introduction

Globally, water pollution issues have intensified due to climate change, industrialization, and urbanization, increasing the importance of water quality management for rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and groundwater resources [

1,

2]. To ensure sustainable water resource security and aquatic ecosystem conservation, monitoring systems capable of real-time surveillance and rapid response to water quality changes should be established. In alignment with this international trend, South Korea’s water quality management policy paradigm has shifted from post-treatment approaches to preventive and real-time management systems.

In South Korea, the Ministry of Environment operates various forms of automated water quality monitoring networks (including total automated water quality, load, and nonpoint source pollution monitoring networks) to systematically manage the quality of the water in major rivers nationwide. These networks continuously monitor and manage key water quality indicators including total organic carbon (TOC), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), turbidity, electrical conductivity (EC), and temperature [

3,

4]. These automated monitoring networks serve various purposes, such as signaling early warnings of water quality degradation, tracking pollution sources, and providing scientific evidence for water quality policy formulation [

4].

Currently, physicochemical parameters such as pH, DO, turbidity, and electrical conductivity in automated water quality monitoring networks can be measured in real time using multi-parameter sensors [

5]. These sensors are based on electrode or optical principles and can be miniaturized and automated, facilitating easy field installation and maintenance. In contrast, organic matter and nutrient indicators such as TOC, TN, and TP still rely on analytical instrument-based measurement methods [

6], which offer advantages such as automated measurement capability, high accuracy, and stability, but they possess several inherent limitations, including the following:

High initial purchase costs and maintenance expenses;

Large installation space and auxiliary equipment requirements;

Time requirements of 30 min to 1 h from sample collection to analysis results;

Secondary waste generation from large volumes of samples and chemical reagents;

Requirement for specialized personnel to maintain precise analytical conditions.

These limitations act as major constraints on policies to expand water quality monitoring networks for broader and more monitoring sites.

Against this background, the transition from analytical instruments to sensor-type measurement devices has recently become a global trend in the water quality monitoring field [

7]. In particular, optical sensors utilizing ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) absorbance principles are receiving attention as next-generation water quality monitoring technologies as they are reagentless, enable real-time measurement, and require simple maintenance [

8].

UV absorbance-based optical sensors utilize the principle that dissolved organic matter and nitrate in water absorb ultraviolet light at specific wavelengths [

9,

10]. Organic matter exhibits strong absorbance primarily at the 254 nm wavelength, while nitrate (NO

3−) shows characteristic absorption spectra in the 200–220 nm wavelength region [

11,

12,

13]. Using these spectroscopic characteristics, TOC and nitrate nitrogen (NO

3-N) can be simultaneously measured without complex chemical analysis [

7,

14].

Currently, sensors capable of directly measuring TN do not exist technologically, and the practical approach of measuring NO3-N, a major component of TN, is employed as an alternative. Particularly in oxidized river and lake environments, a significant portion of nitrogen compounds exists in the form of nitrate nitrogen (NO3-N). While ammonium or organic nitrogen may prevail near wastewater discharges, NO3-N measurement often functions as an effective surrogate indicator for total nitrogen (TN) in general surface water monitoring contexts.

However, South Korea’s technological capacity for optical sensors capable of simultaneously measuring TOC and NO3-N is severely limited, with products from a few global manufacturers dominating the market. This increases dependence on foreign equipment for water quality monitoring, causes difficulties in maintenance and technical support, and acts as a factor undermining the self-sufficiency of national water quality management infrastructure. Therefore, the development of simultaneous TOC·NO3-N measurement sensors based on domestic technology is a priority.

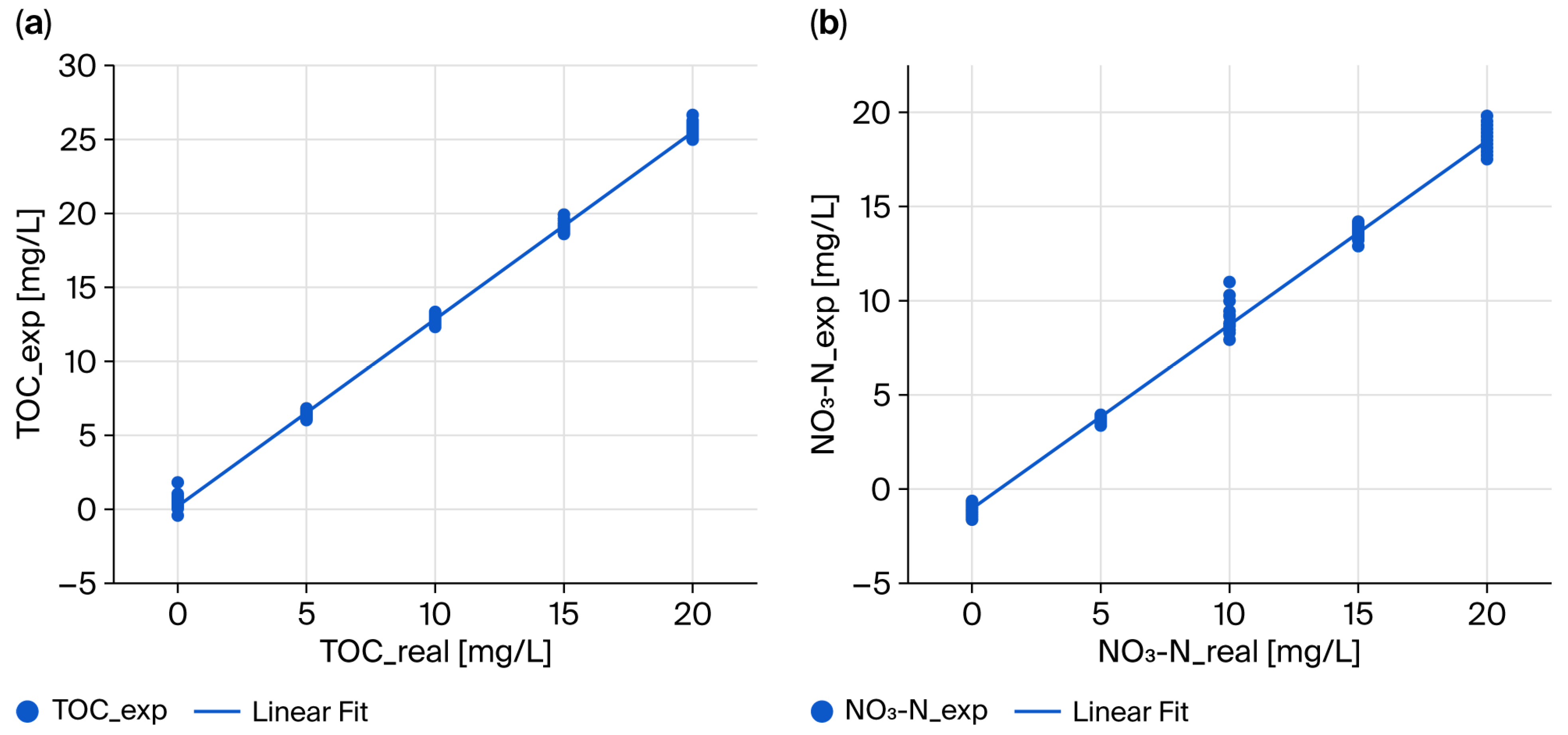

This study was conducted to evaluate the field applicability of TOC and NO3-N measurement methods using HASM-4000—a UV absorbance-based optical sensor developed with domestically developed technology—in response to these technical and policy needs. Specifically, the objectives were to (1) elucidate the measurement principles and structural characteristics of the HASM-4000 sensor; (2) establish calibration curves and conduct performance verification using standard materials under laboratory conditions; (3) assess measurement accuracy and reproducibility through comparative evaluation with certified analytical methods for actual river and lake water samples; and (4) identify potential applicability and limitations for field water quality monitoring. Although the calibration experiments were primarily based on standard and synthetic samples, the matrix-dependent nature of UV absorbance is well recognized. To partially address this limitation, ten river water samples collected from national monitoring sites in Korea were additionally analyzed, and comparisons between actual concentrations (TOC_real and NO3-N_real) and sensor-estimated concentrations (TOC_exp and NO3-N_exp) demonstrated preliminary but meaningful similarities (R2 = 0.819 for TOC; R2 = 0.868 for NO3-N). While the validation was performed using samples from Korean monitoring sites, the developed optical sensor platform addresses universal challenges in water quality monitoring such as high costs and reagent consumption. Thus, this study aims to contribute not only to local infrastructure but also to the global development of cost-effective, high-density monitoring networks.

2. Materials and Methods

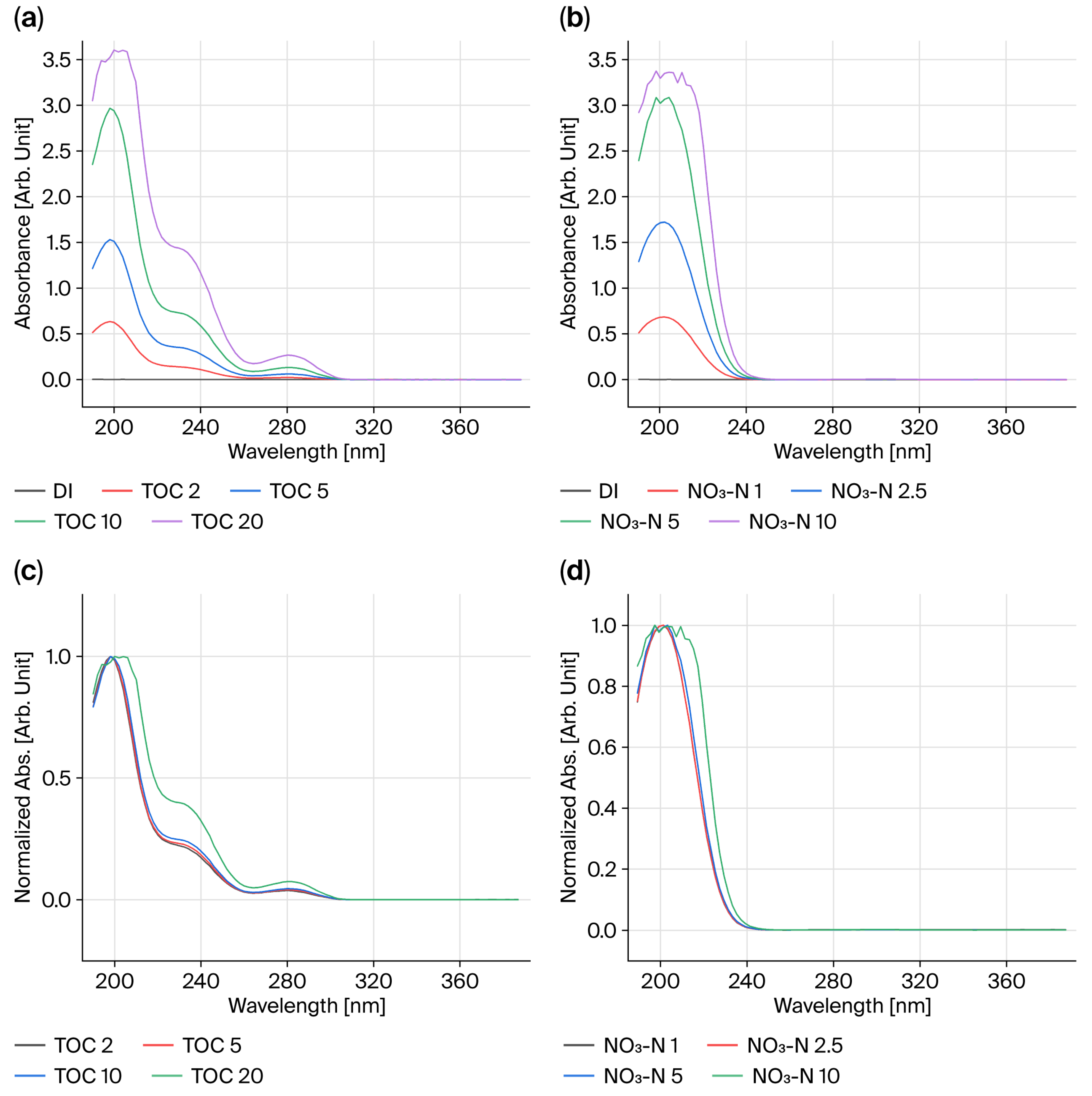

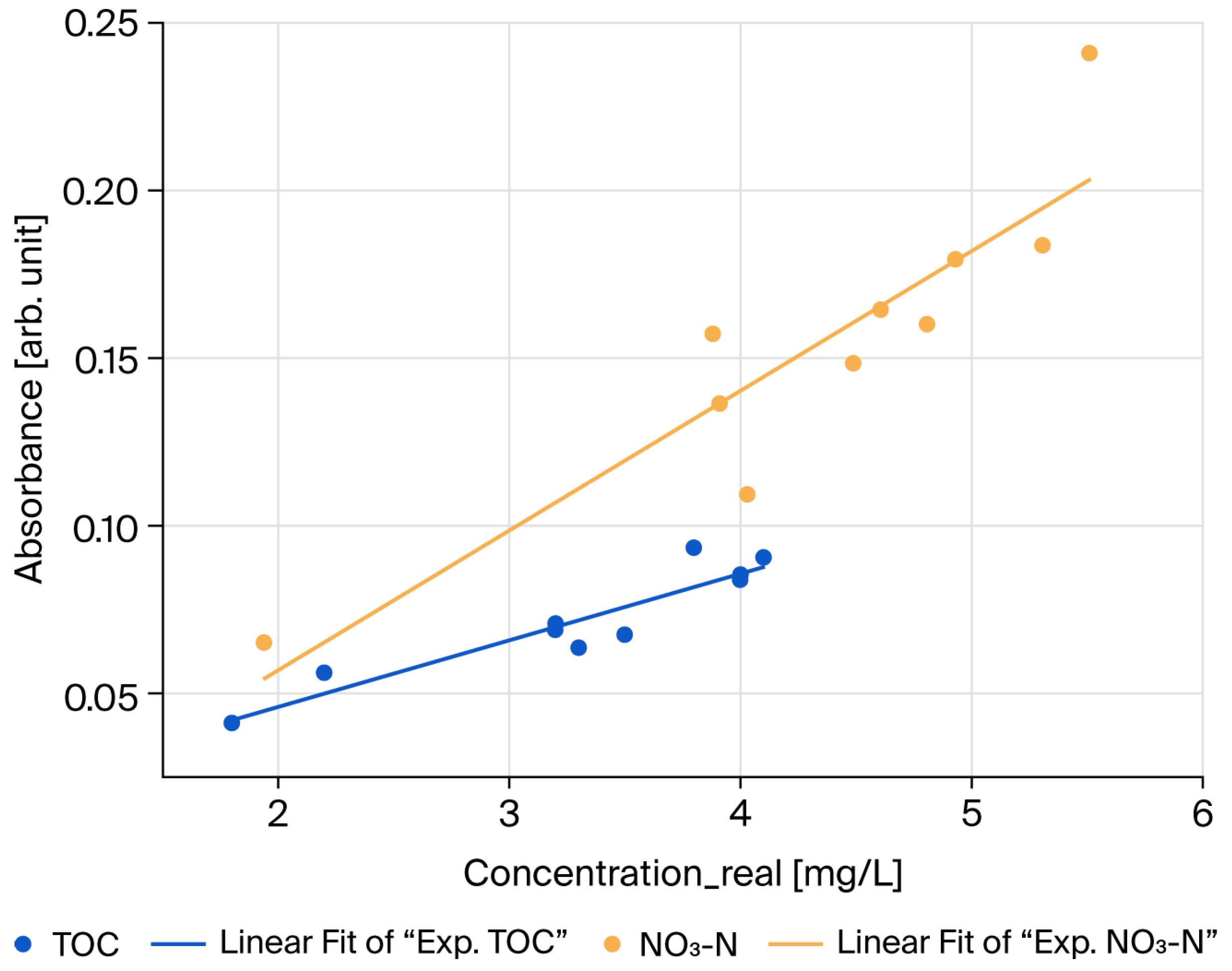

Methods of measuring total organic carbon (TOC) and nitrate (NO3-N) using UV absorbance were developed, utilizing both a commercial Agilent Cary 60 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a prototype HASM-4000 manufactured by HSKorea Co., Ltd. Absorbance (or optical density), representing the degree of light absorption in measured samples, was calculated from transmission spectrum information obtained from each instrument based on the Beer–Lambert law.

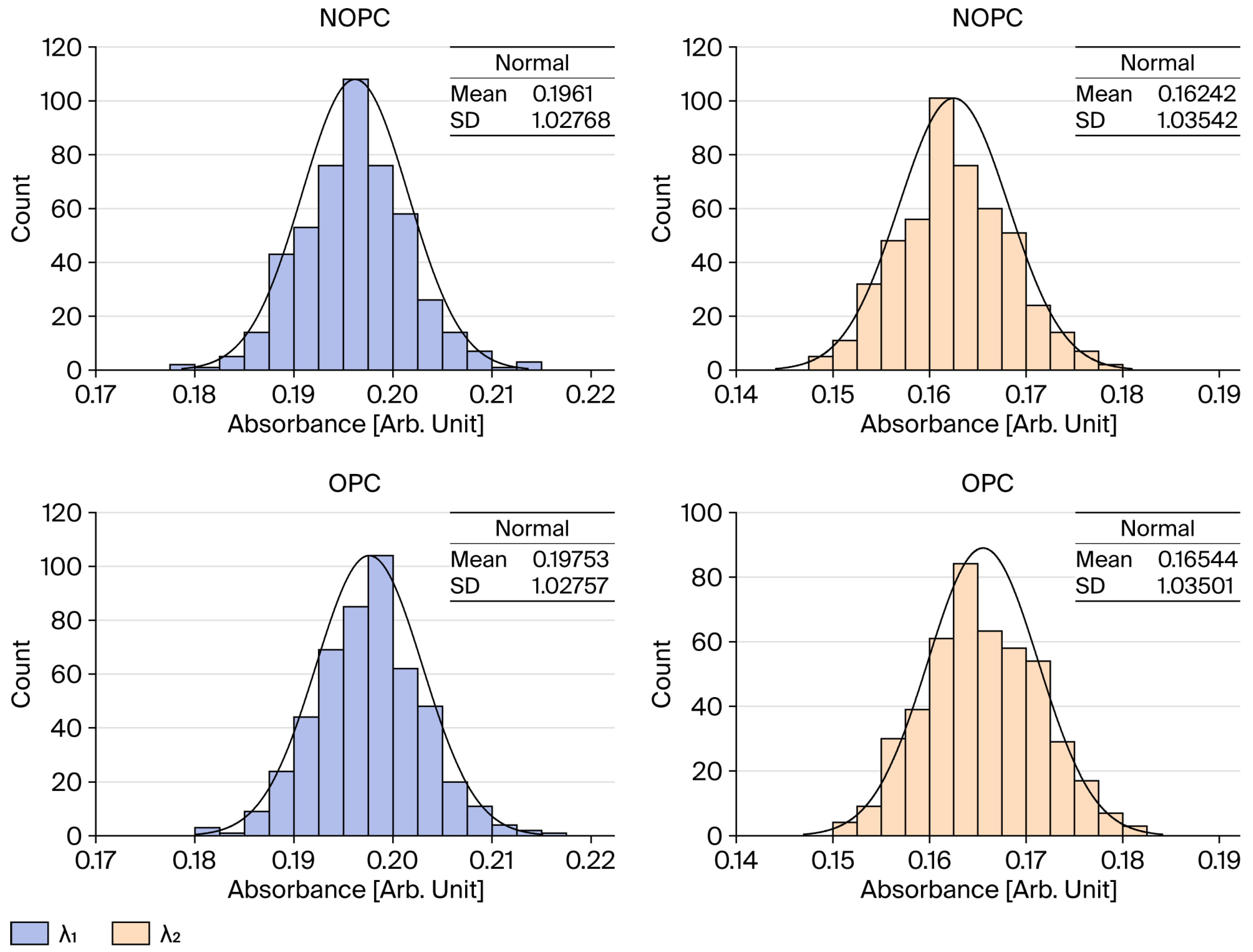

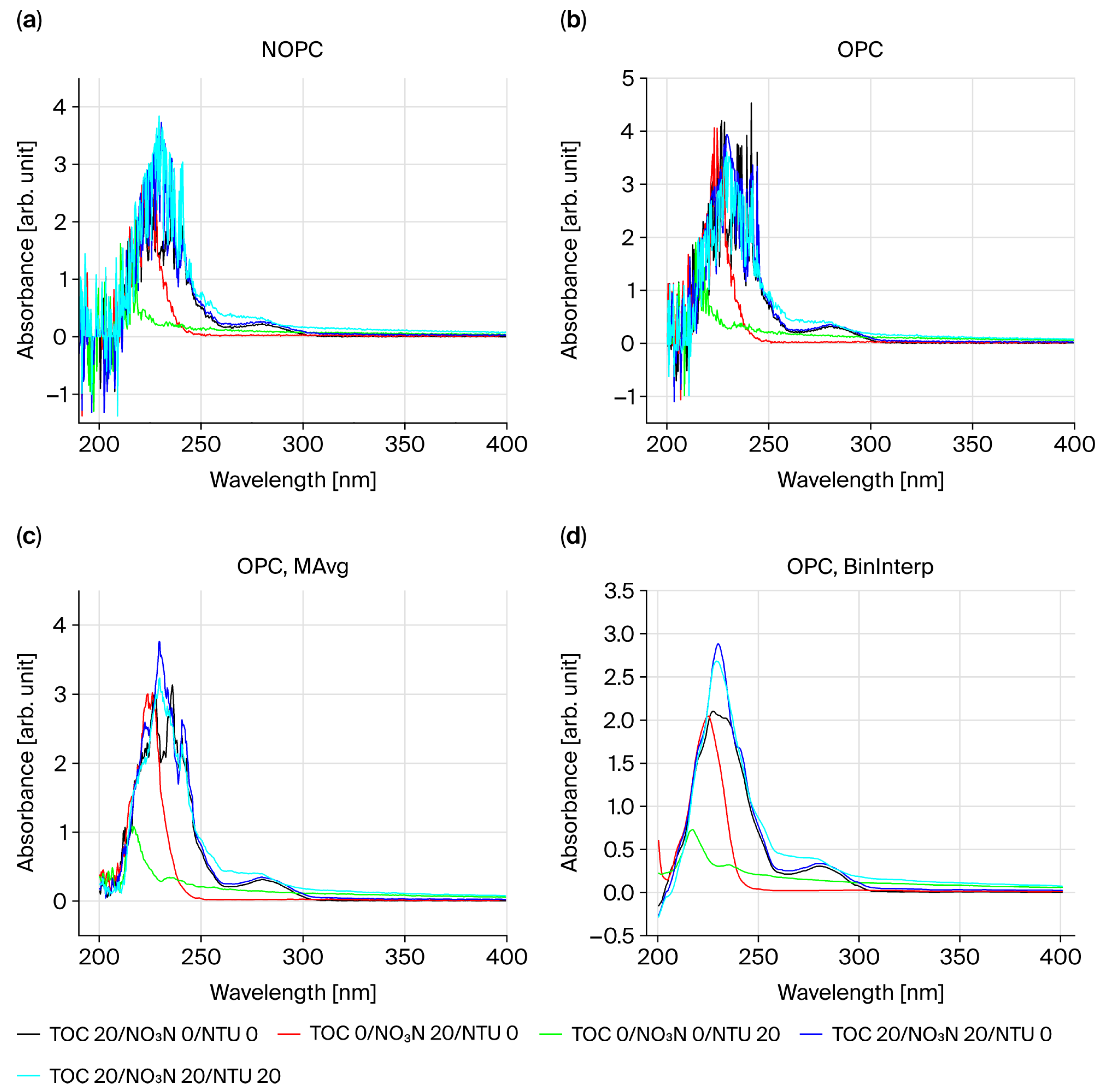

Absorbance was measured at various concentrations of total organic carbon (TOC), nitrate (NO3-N), and turbidity (NTU) using each instrument. These absorbance measurements were corrected via techniques such as optical power compensation (OPC) and Binning and Interpolation (BinInterp), and concentrations were calculated by deriving correlations.

The standard materials used in this study included distilled water (DI) with TOC and NO3-N concentrations of 0 mg/L or a turbidity of 0 NTU as the blank, and pure unmixed standard materials of 5 mg/L, 10 mg/L, and 20 mg/L were prepared. For mixed TOC and NO3-N solutions excluding turbidity (TU), TOC/NO3-N/TU concentrations were mixed at 5/5/0, 10/10/0, and 20/20/0, while mixed solutions including turbidity were mixed at 5/5/5, 10/10/10, and 20/20/20.

2.1. UV Absorbance Method

The UV absorbance method is used to measure absorbance at specific UV wavelengths to quantify water pollutant concentrations. Sample concentrations can be measured using the Beer–Lambert law, which states that the light absorbed by a solution depends on the concentration and liquid layer thickness. Many substances present in wastewater or river water absorb ultraviolet (UV) light, so concentrations are measured using light in the UV region between 190 and 400 nm.

The UV absorbance method has low maintenance costs and short response times and is known to be particularly suitable for measuring organic matter at low concentrations. A narrow wavelength range of the light source passed through a monochromator or filter is selected and passed through the sample layer, and then absorbance is measured with a detector to quantify the concentration of the target component.

When light passes through a sample, its intensity decreases due to absorption. Transmittance (T) is defined as the ratio of the transmitted light intensity (I) to the incident light intensity (I

0), as shown in Equation (1):

According to the Beer–Lambert law, absorbance (A) is defined as the logarithm of the reciprocal of transmittance, which represents the light absorption capacity of the sample. This relationship is expressed in Equation (2):

2.2. Data Processing and Correction Techniques

When smooth absorbance spectra cannot be confirmed in the short wavelength region by the UV absorbance method, absorbance or transmission spectra can be corrected through arithmetic methods such as Moving Average (MAvg) and Binning techniques to improve this problem.

2.2.1. Moving Average Method (MAvg)

The Moving Average technique is a smoothing technique that sets a window of constant size for consecutive data sections, calculates the average value of the data in that section, and generates new time series or spectral data. It effectively removes high-frequency noise present in the data, allowing overall signal patterns to be more clearly identified.

The basic formula for MAvg is as follows, where the new value

yi at each position

i is calculated as the average of

n surrounding data points:

where

xk represents the raw data, and

yi denotes the new data with the Moving Average applied. The window size is defined as

n = 2

m + 1, where m indicates the number of data points included to the left and right of the center point.

Through this technique, abrupt fluctuations and random noise are mitigated, and in spectral data, the stability and reliability of the transmission and absorbance are improved.

Transmission spectrum data output from the spectrometer represents wavelength versus light intensity information in a 2500 pixel × 2-column array format (first column: wavelength; second column: transmittance intensity). In this study, absorbance was calculated using transmittance intensity (second column) and the Beer–Lambert law, and an improved absorbance spectrum was obtained by applying MAvg with avg_size (~2.14 nm = 0.36 nm × 6) to the calculated absorbance.

2.2.2. Binning and Interpolation (BinInterp)

Data Binning is the process of grouping or simplifying data, which reduces data complexity and smooths data by mitigating the effects of noise or minor observation errors. It is particularly used to convert continuous data, such as absorption spectra, into categorical data to simplify analysis or prevent overfitting.

After dividing a given data range into a specific number of bins (sections), original data values belonging to each bin are replaced with representative values (mean, median, etc.) of that bin. As a result, data precision may somewhat decrease, but there is an advantage in identifying overall patterns or trends.

Binning can be simply represented as a function

B that assigns an input variable

X to specific bins:

Here, x represents the value of the input data point (the original continuous variable), and B(x) is the label or representative value assigned to the bin containing x. The interval [Li, Ui] is defined by the lower bound Li and the upper bound Ui of the i-th bin.

Interpolation (Interp) refers to the process of estimating and filling missing values between data points. It maintains data continuity and supplements missing information by predicting values at unobserved points and is utilized in various fields, including signal processing, where sampled signals are reconstructed into continuous signals.

Values between known data points can be estimated using specific functions (e.g., linear functions, polynomial functions, splines, etc.) based on known surrounding data values, generating new data points within the range of the original data to increase the dataset density or supplement missing data.

In this study, a 2500 × 2 data array, identical to RawData, was reconstructed using Binning and Interpolation (BinInterp). When using Binning, the total number of RawData decreases by the number divided by ‘Bin(2.14 nm, 6)’ (2500/6). To compensate for this data reduction, Interpolation was applied to the binned data in this study to convert it to a 2500 × 2 data array.

2.3. Spectral Analysis Equipment

2.3.1. Agilent Cary 60

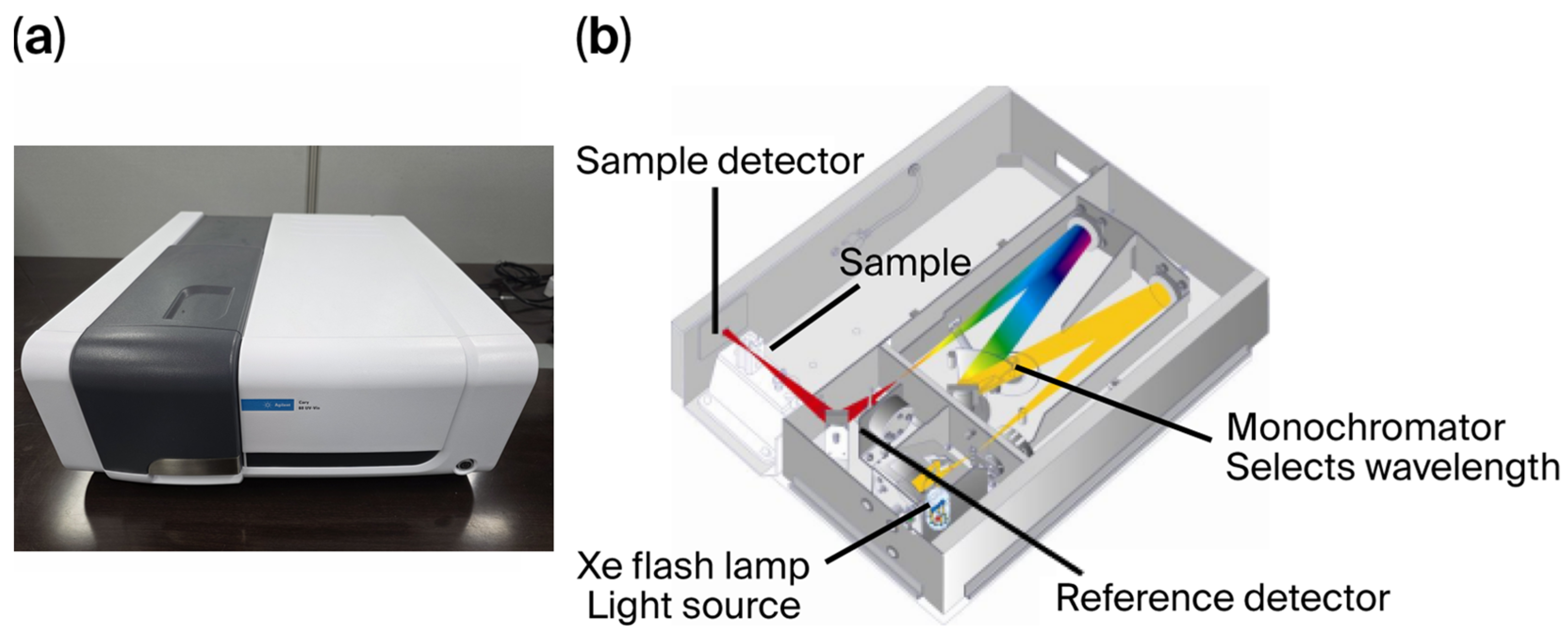

The commercial product used for absorbance analysis in this study was the Agilent Cary 60 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (

Figure 1). This laboratory-grade equipment utilizes two optical paths and a photomultiplier tube (PMT) to simultaneously measure light transmitted through a blank (empty cuvette) and a sample at a single wavelength. This dual-beam configuration provides stable absorbance readings by minimizing noise generated by light-source-intensity fluctuations.

For the analysis of TOC and NO3-N standard samples, absorbance spectra were acquired in the wavelength range of 190–390 nm, with a scanning step size of 2 nm and an integration time of 0.1 s at each wavelength.

TOC and NO3-N standard samples were analyzed using the Cary 60 with a step size of 2 nm and an integration time of 0.1 s at each wavelength, measuring absorbance spectra while varying standard sample concentrations from 190 nm to 390 nm.

2.3.2. HSKorea Co., Ltd. HASM-4000

The ultimate goal of this study was to develop a sensor-type device capable of measuring TOC and NO

3-N in a manner suitable for in situ applications. Unlike the Cary 60 described above, the prototype HASM-4000 (

Figure 2) employs a single optical path and a 1D-array optical detector (1 × 2500 pixels).

For each sample, light emitted from the light source (Xenon flash lamp L4622, 10 W, Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan) in the 200–1100 nm range passes through the sample on the 10 mm optical beam path and enters an optical fiber with a core diameter of 1 mm, and the transmitted light then propagates to the spectrometer, which provides transmission spectrum (optical transmittance) information about the sample in the wavelength region from 150 nm to 1050 nm (0.36 nm/px × 2500 px) inside the spectrometer.

To achieve relatively uniform distribution of light intensity emitted from the light source, the light propagation direction was changed to become similar to parallel light, and unnecessary external light was reduced. Then, a diffuser (DF) and a pinhole (PH) were placed in front of the light source and optical fiber, respectively. Although the Beer–Lambert law theoretically requires monochromatic light and the absence of stray light, practical in situ sensors often utilize broadband light sources (e.g., Xenon flash lamps) and array detectors to achieve real-time monitoring. This approach is widely adopted in both academic research and industrial applications [

15]. For instance, Kim et al. [

16] and Li et al. [

17] successfully quantified organic compounds using similar optical configurations, and Shi et al. [

18] validated the use of submersible UV-Vis spectrophotometers for environmental monitoring. Furthermore, commercial sensors from major manufacturers (e.g., YSI) also calculate absorbance based on the fundamental relationship A = log(I

0/I) [

5]. To ensure the validity of this approach in HASM-4000, we incorporated a diffuser and pinhole to minimize stray light and ensure quasi-collimation, and applied optical power compensation (OPC) to correct for light source fluctuations, thereby securing sufficient linearity (R

2 > 0.99) for quantitative analysis.

2.4. Concentration Calculation Model

The concentrations of TOC and NO

3-N were derived using the absorbance values at specific wavelengths processed through OPC and BinInterp. The calculation models are based on the following equations:

Here, Abs

254 and Abs

230 represent the absorbance values at 254 nm and 230 nm, respectively. The empirical constants and ratio factors used in these equations are summarized in

Table 1, where the ratio factors (R

TOC and R

NO3) serve as slope correction coefficients derived from the calibration curves to minimize the deviation between the estimated and actual concentrations.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

In this study, the sensor-type optical analytical equipment HASM-4000—capable of simultaneously analyzing TOC and NO3-N and suitable for underwater immersion and portability—was manufactured, and optical measurements were performed on actual TOC and NO3-N standard samples using the device. Measurement data were obtained as light emitted from the light source passed through samples placed in a 10 mm optical path, and light incident on the spectrometer was dispersed into transmission spectrum information in the 200–1050 nm region. After data preprocessing via optical power compensation (OPC) and Binning and Interpolation (BinInterp), sample absorbance spectra were derived according to the Beer–Lambert law, which were used to determine TOC and NO3-N concentration calculation equations. By confirming a high R2 value of 0.999 between actual sample concentrations and experimental sample concentrations, TOC and NO3-N measurement capabilities were verified using standard samples with HASM-4000. Additionally, preliminary validation using actual river water samples showed promising correlations (R2 > 0.8), suggesting the method’s feasibility for field application.

However, the correlations observed in the pure standard samples could not be confirmed in mixed samples of turbidity with TOC and NO

3-N, likely due to the optical measurement limitations of the HASM-4000 equipment, which was designed with a 10 mm optical path. To quantitatively assess the impact of pathlength on scattering interference, we conducted a supplementary experiment comparing absorbance spectra using 1 mm and 10 mm pathlengths (see

Supplementary Information, Figure S1). The results demonstrated that reducing the pathlength to 1 mm decreased the turbidity-induced absorbance signal to approximately 6.5% of that observed at 10 mm. This confirms that shortening the optical path is a physically effective strategy for mitigating scattering interference.

To overcome these limitations in field application, future research is needed to develop new concentration calculation methods that utilize absorbance ratio (AR) values of λ1/λ2 and λ2/λ1 and have non-linearity according to concentration for constants used in the final calculation equation.

Furthermore, based on the findings from our supplementary pathlength experiment, we plan to transition the optical path from 10 mm to 5 mm and incorporate collimating lenses to parallelize the emitted light, along with focusing lenses to collect the transmitted light. Moreover, replacing currently used self-manufactured diffusers and pinholes with commercial products for additional research is expected to improve absorbance below 250 nm and enhance performance. While this study confirmed the sensor’s potential through standard and preliminary field samples, further research is needed to conduct comprehensive field validation across diverse hydrological conditions to identify and mitigate interference effects leading to its commercialization. In addition to standard and synthetic solutions, preliminary testing using ten river water samples demonstrated reasonable consistency between actual laboratory-measured concentrations and sensor-estimated concentrations (R2 = 0.819 for TOC; R2 = 0.868 for NO3-N). These findings suggest that the optical–computational framework has potential for field application; however, comprehensive validation across diverse water bodies, seasonal variations, and matrix conditions remains essential for reliable deployment.