Multi-Objective Optimization for Irrigation Canal Water Allocation and Intelligent Gate Control Under Water Supply Uncertainty

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Current Research Progress and Limitations

1.3. Main Research Content and Innovations

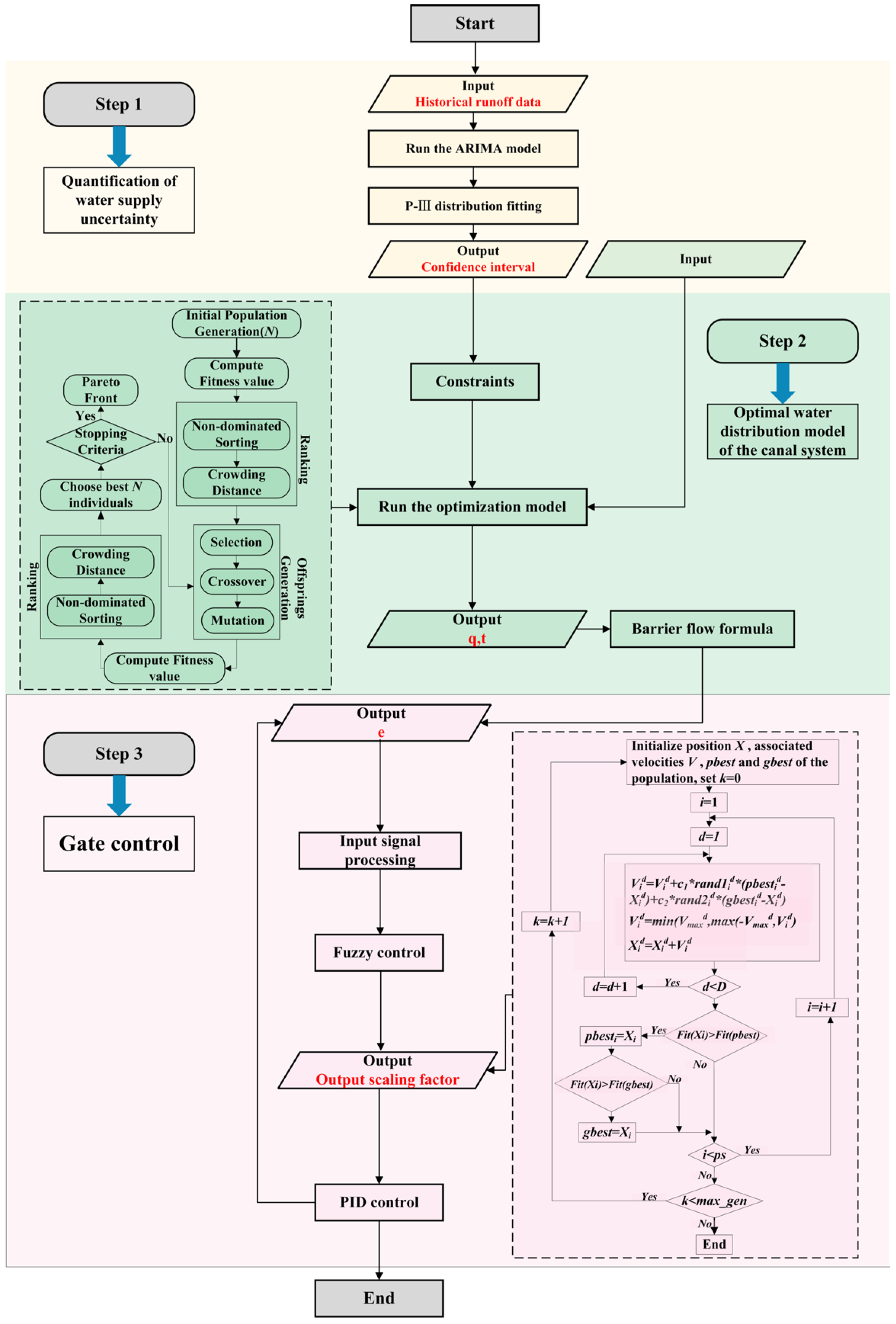

2. Methodology

2.1. Significance of the Study

2.2. Multi-Objective Optimization Model for Canal Water Allocation in Irrigation Districts

2.2.1. Objective Functions

- (1)

- Primary objective: Seepage minimizationSeepage volume was quantified using a modified Kostiakov infiltration equation [12]where β denotes the seepage reduction coefficient after anti-seepage measures are applied to the canal; A represents the permeability coefficient of the canal bed; l indicates the water conveyance length of the canal (km); m signifies the seepage exponent of the canal bed; qn (where N = 1, 2, …, n) refers to the water distribution flow rate of canal N (m3/s); Δtn corresponds to the water distribution duration (s), where tsn and ten represent the initiation and termination times (s) of water distribution for canal N, respectively.

- (2)

- Secondary objective: Minimization of discharge deviation between the main canal and actual flowwhere q1t represents the irrigation discharge (m3/s) in the main canal on day t; q1ta denotes the actual irrigation discharge (m3/s) in the main canal on day t.

2.2.2. Constraints

- (1)

- Capacity constraint: The water distribution flow rate should range between 0.6 and 1.0 times the designed channel capacity.where qmax represents the designed channel capacity, αd denotes the minimum flow reduction coefficient, and αu indicates the flow amplification coefficient.

- (2)

- Water balance constraint: The product of distribution flow rate and duration must equal the channel’s water demand.where W indicates the water demand (m3/s), and Δtn represents the distribution duration (s).

- (3)

- Temporal constraint: Both initiation and termination of water delivery must occur within the original irrigation period.where T denotes the distribution cycle (days).

- (4)

- Flow continuity constraint: The distribution flow rate in superior channels must equal the sum of subordinate channels’ flow rates.where qi represents the superior channel flow rate (m3/s), and qp indicates the flow rate of the i-th subordinate channel (m3/s).

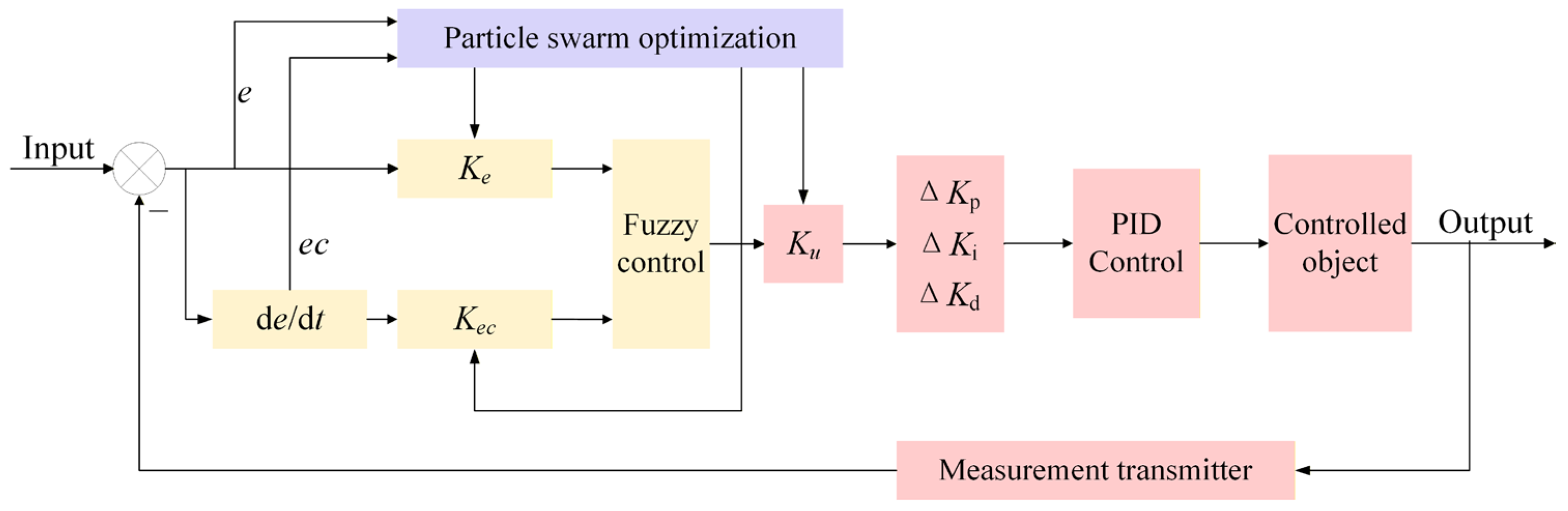

2.3. Gate Control System

2.3.1. Gate Control Mechanism

2.3.2. Mathematical Modeling of Gate Control System

2.3.3. Fuzzy PID Optimization Using Particle Swarm Algorithm

PID Control Algorithm

Fuzzy Logic Design

Control Algorithm Parameter Optimization

2.4. Water Supply Uncertainty

2.4.1. Runoff Simulation Using ARIMA Modeling

2.4.2. Interval Representation of Runoff Uncertainty

2.5. Model Solution Framework

3. Case Study Application

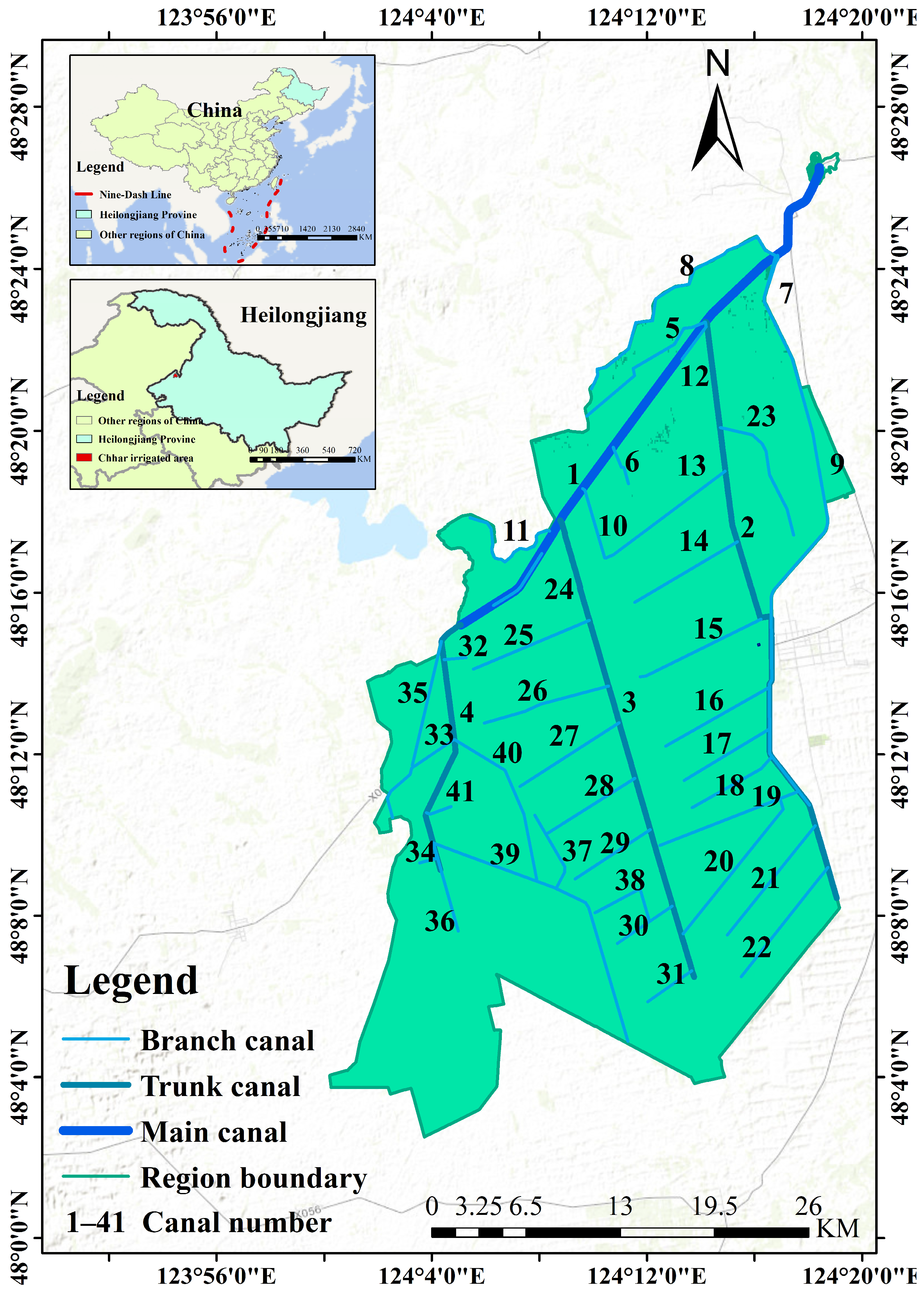

3.1. Study Area Overview

3.2. Data Sources

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Water Supply Uncertainty Quantification

4.2. Analysis of Optimized Canal Water Allocation Results

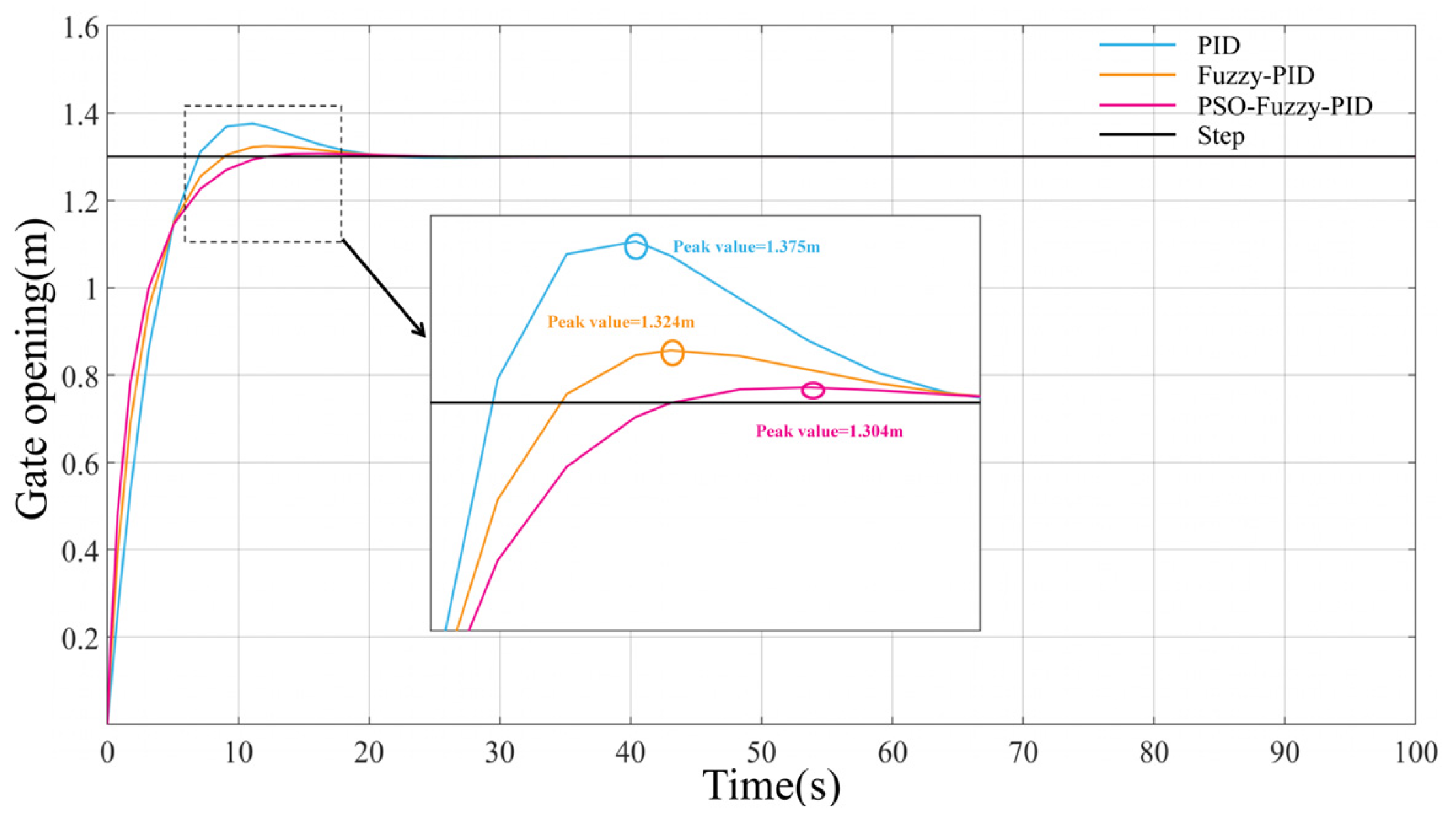

4.3. Gate Control Performance Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| e | ec | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB | NM | NS | ZO | PS | PM | PB | |

| NB | PB/NB/PB | PB/NB/PB | PM/NM/PM | PM/NM/PM | PM/NM/PM | PB/NB/PB | PB/NB/PB |

| NM | PB/NB/PB | PB/NB/PM | PM/NMN/PS | PM/NM/PS | PM/NM/PS | PB/NB/PM | PB/NB/PB |

| NS | PM/NM/PM | PS/NM/PS | PS/NS/PS | ZO/NS/PS | PS/NS/PS | PM/NM/PS | PM/NM/PS |

| ZO | PM/NM/PM | PS/NM/PS | PS/NS/PS | ZO/NS/PS | PS/NS/PS | PS/NM/PS | PM/NM/PM |

| PS | PM/NM/PM | PM/NM/PS | PS/NS/PS | PS/NS/PS | PS/NS/PS | PM/NM/PS | PM/NM/PM |

| PM | PB/NB/PB | PB/NB/PM | PM/NM/PS | PM/NM/PS | PM/NM/PM | PB/NB/PM | PB/NB/PB |

| PB | PB/NB/PB | PB/NB/PB | PM/NM/PM | PM/NM/PM | PM/NM/PM | PB/NB/PB | PB/NB/PB |

| Channel Number | Length (m) | Design Flow (m3/s) | Water Demand (m3) | Gate Size (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27.31 | 72.65 | 146.87 × 106 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 2 | 26.81 | 30.50 | 477.70 × 105 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 3 | 21.70 | 11.50 | 232.72 × 105 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 4 | 12.67 | 20.50 | 284.02 × 105 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 5 | 7.17 | 3.66 | 226.24 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 6 | 3.25 | 0.40 | 52.74 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 7 | 2.50 | 1.60 | 129.12 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 8 | 5.00 | 4.51 | 162.33 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 9 | 17.5 | 14.30 | 674.52 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 10 | 5.00 | 3.20 | 662.58 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 11 | 4.70 | 3.05 | 743.17 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 12 | 2.70 | 2.13 | 415.53 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 13 | 6.78 | 4.50 | 396.92 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 14 | 6.23 | 4.11 | 583.98 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 15 | 4.89 | 4.75 | 518.40 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 16 | 4.20 | 4.56 | 493.69 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 17 | 3.60 | 3.50 | 407.12 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 18 | 3.40 | 3.05 | 389.15 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 19 | 6.80 | 2.54 | 327.11 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 20 | 7.20 | 2.10 | 270.95 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 21 | 6.50 | 2.10 | 290.48 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 22 | 6.50 | 2.10 | 245.20 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 23 | 1.25 | 6.79 | 540.17 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 24 | 6.25 | 5.60 | 560.08 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 25 | 5.00 | 4.90 | 295.57 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 26 | 5.20 | 2.48 | 226.84 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 27 | 5.30 | 1.98 | 167.27 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 28 | 3.30 | 3.10 | 284.08 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 29 | 3.30 | 1.69 | 159.71 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 30 | 1.30 | 1.10 | 114.26 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 31 | 2.50 | 1.10 | 148.13 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 32 | 3.90 | 2.73 | 225.44 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 33 | 5.00 | 2.15 | 175.01 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 34 | 1.30 | 1.21 | 119.64 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 35 | 7.00 | 4.08 | 335.92 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 36 | 2.00 | 1.10 | 103.30 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 37 | 3.70 | 4.51 | 703.17 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 38 | 4.20 | 1.93 | 214.11 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 39 | 5.90 | 2.70 | 566.28 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 40 | 6.60 | 2.33 | 579.37 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| 41 | 2.00 | 1.51 | 350.87 × 104 | 1.5 × 1.5 |

| Definition | Value |

|---|---|

| Hydraulic conductivity coefficient of channel bed soil A | 1.9 |

| Seepage reduction factor post anti-seepage measures β | 0.5 |

| Permeability index of channel bed m | 0.4 |

| Discharge coefficient μ | 0.6 |

| Gravitational acceleration g/m/s2 | 9.81 |

| Water distribution cycle T/d | 45 |

References

- Gao, Z.; Wang, H. Strategy of Grain Security and Irrigation Development in China. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2008, 39, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z. Technical Achievement and Prospection in Irrigation Scheme Development and Management in China. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2019, 50, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, A.; Raghuwanshi, N.; Singh, R. Development and Application for Irrigation of Hydraulic Simulation Model Canal Network. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2008, 134, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, C.; Nan, Z. A Decision Support System for Irrigation Water Allocation along the Middle Reaches of the Heihe River Basin, Northwest China. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 47, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanooni, A.; Monem, M. INTEGRATED STEPWISE APPROACH FOR OPTIMAL WATER ALLOCATION IN IRRIGATION CANALS. Irrig. Drain. 2014, 63, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Bayraksan, G. A Multistage Distributionally Robust Optimization Approach to Water Allocation under Climate Uncertainty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 306, 849–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Zheng, N.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C. Robust Optimization for Sustainable Agricultural Management of the Water-Land-Food Nexus under Uncertainty. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 403, 136846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Z.; He, Y.; Feng, C.; Han, C.; Shi, Y.; Qi, W. Multi-Objective Modeling and Optimization of Water Distribution for Canal System Considering Irrigation Coverage in Artesian Irrigation District. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 301, 108959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Fan, Y.; Gao, Z.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. An Optimal Water Distribution Model for Canal Systems Based on Water Level. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hao, C.; Zhang, X.; Yu, H.; Sun, Y.; Yin, Z.; Li, X. Sluice Gate Flow Model Considering Section Contraction, Velocity Uniformity, and Energy Loss. J. Hydrol. 2025, 656, 133020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsen, R.; Di Bitonto, P.; Novielli, P.; Magarelli, M.; Romano, D.; Diacono, D.; Monaco, A.; Amoroso, N.; Bellotti, R.; Tangaro, S. Harnessing Digital Twins for Sustainable Agricultural Water Management: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostiakov, A.N. On the dynamics of the coefficient of water percolation in soils. In Transactions of 6th Committee International Society of Soil Science; International Society of Soil Science: Moscow, USSR, 1932; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Munson, B.R.; Young, D.F.; Okiishi, T.H.; Huebsch, W.W. Fundamentals of Fluid Mechanics, 8th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-119-08070-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata, K. Modern Control Engineering, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-13-615673-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, J.G.; Nichols, N.B. Optimum Settings for Automatic Controllers. Trans. ASME 1942, 64, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, S.; Li, Q. Variable Universe fuzzy PID Control of Horizontal Vibration of High-Speed Elevator Cars Based on BP-NSGA-II Optimization. Noise Vib. Control 2024, 44, 63–69, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, P.; Xiong, W.; Wu, Q.; Li, R.; Huang, G. pH Optimization for Precursor Reactor Based on Particle Swarm Optimization and fuzzy PID Control. Min. Metall. Eng. 2021, 41, 221–225. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Xiao, W.; Zeng, L.; Ma, L. Analysis and Prediction of Effects of Three Gorges Reservoir Water Level Scheduling on the Outflow Water Quality. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 2020, 31, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Song, S. Estimation of Confidence Interval for Hydrologic Design Values. J. Northwest A&F Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2016, 44, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 22482-2008; Standard for Hydrological Information and Hydrological Forecasting. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Fan, Y.; Chen, H.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J. Optimal Water Distribution Model of Canals Considering the Workload of Managers. Irrig. Drain. 2023, 72, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Xiong, L. Research on a Hybrid Controller Combining RBF Neural Network Supervisory Control and Expert PID in Motor Load System Control. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2022, 14, 16878132221109994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, J.; Li, W.; Luo, K. CFHBA-PID Algorithm: Dual-Loop PID Balancing Robot Attitude Control Algorithm Based on Complementary Factor and Honey Badger Algorithm. Sensors 2022, 22, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Confidence Level | Confidence Interval |

|---|---|

| 90% | [416.12, 624.35] × 106 m3 |

| 95% | [390.59, 650.43] × 106 m3 |

| 99% | [364.18, 676.36] × 106 m3 |

| Control Algorithm | Step Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | Settling Time (s) | |

| PID Control | 5.38 | 16.45 |

| Fuzzy PID Control | 1.92 | 12.06 |

| PSO-Fuzzy-PID Control | 0.54 | 9.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, Q.; Xu, X.; Li, M.; Ye, X.; Liu, W.; Lian, H.; Zhou, Y. Multi-Objective Optimization for Irrigation Canal Water Allocation and Intelligent Gate Control Under Water Supply Uncertainty. Water 2025, 17, 3585. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243585

Cai Q, Xu X, Li M, Ye X, Liu W, Lian H, Zhou Y. Multi-Objective Optimization for Irrigation Canal Water Allocation and Intelligent Gate Control Under Water Supply Uncertainty. Water. 2025; 17(24):3585. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243585

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Qingtong, Xianghui Xu, Mo Li, Xingru Ye, Wuyuan Liu, Hongda Lian, and Yan Zhou. 2025. "Multi-Objective Optimization for Irrigation Canal Water Allocation and Intelligent Gate Control Under Water Supply Uncertainty" Water 17, no. 24: 3585. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243585

APA StyleCai, Q., Xu, X., Li, M., Ye, X., Liu, W., Lian, H., & Zhou, Y. (2025). Multi-Objective Optimization for Irrigation Canal Water Allocation and Intelligent Gate Control Under Water Supply Uncertainty. Water, 17(24), 3585. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243585