Abstract

Hydrological droughts represent a growing challenge for northern watersheds in Thailand, where climate change is projected to intensify seasonal water stress and destabilize agricultural productivity and water resource management. This study employed the Composite Hydrological Drought Index (CHDI) to evaluate the spatiotemporal characteristics of future droughts under representative concentration pathway (RCP) scenarios. The findings revealed a pronounced seasonal contrast: under RCP8.5, the CHDI values indicated more severe drought conditions during the dry season and greater flood potential during the wet season. Consequently, the region faces dual hydrological threats: prolonged water deficits and increased flood exposure within the same annual cycle. Drought persistence is expected to intensify, with maximum consecutive drought runs extending up to 10–11 months in future projections. The underlying mechanisms include increased actual evapotranspiration, which accelerates soil moisture depletion, enhanced rainfall variability, which drives the sequencing of floods and droughts, and catchment storage properties, which govern hydrological resilience. These interconnected processes alter the timing and clustering of drought events, concentrating hydrological stress during periods that are sensitive to agriculture. Overall, drought behavior in northern Thailand is projected to intensify in a spatially heterogeneous pattern, emphasizing the need for localized, integrated adaptation measures and flexible water management strategies to mitigate future risks of drought.

1. Introduction

Hydrological droughts arise when a meteorological water deficit propagates through the terrestrial water cycle, leading to abnormally low levels of soil moisture, streamflow, groundwater, and reservoir storage [1]. This propagation is a complex and nonlinear process shaped by precipitation deficits, increased evaporative demand, and the filtering effects of catchment storage and groundwater systems [1,2,3]. Typically, deficits evolve sequentially from precipitation shortfalls to soil moisture depletion, reduced groundwater recharge, declining baseflow, and eventually reduced surface water availability, resulting in delayed but prolonged hydrological droughts that can persist long after meteorological conditions have recovered [1,2]. Key features of this propagation include lag, attenuation, and pooling, whereby multiple dry spells merge into a single extended drought event [1].

Climate change and its associated extreme events have emerged as critical global challenges in the 21st century [4]. Among these, hydrological extremes, such as severe droughts, prolonged water scarcity, and disruptions to rainfall and hydrological regimes, are considered substantial threats to ecosystems, agricultural productivity, and socio-economic stability [4,5,6,7]. Mid-century projections indicate significant global and regional impacts, particularly hydrological drought, as warming is expected to exceed 2 °C under high greenhouse gas (GHG) emission scenarios. Such warming is projected to intensify the global hydrological cycle, resulting in more frequent and severe hydrometeorological extremes [8,9]. Multi-indicator assessments using Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) models project increases in drought frequency and intensity across most regions [10], driven in part by higher atmospheric evaporative demand, which exacerbates soil moisture depletion and hydrological droughts, even when precipitation remains relatively unchanged [6].

Southeast Asia is among the most vulnerable regions to climate extremes, with projections indicating more frequent and intense heavy rainfall associated with monsoon dynamics at 1.5–2.0 °C of warming [8,9]. In the Mekong River Basin, dry seasons are expected to become drier, with more rainless days (precipitation < 0.1 mm/day) and fewer precipitation days [11]. Rising temperatures are also projected to intensify drought severity, with dry-season droughts comprising approximately 60% of events in the near future (2021–2055) and more than 80% in the far future (2061–2095) [12]. El Niño and the Southern Oscillation (ENSO) related variability is likely to compound these risks by increasing the likelihood of prolonged droughts while also elevating flood hazards [6,8]. These changes have profound implications for water security [13,14], agricultural productivity [15], ecosystem resilience [16,17], and public health [18], underscoring the need for robust climate assessments to better understand hydrological extremes and their cascading impacts.

Thailand, particularly its northern watersheds, is one of the most vulnerable subregions in Southeast Asia [9]. Historical evidence indicates recurring and prolonged hydrological droughts driven by insufficient rainfall, rising temperatures, increased evaporation, escalating water demand, and widespread off-season agricultural practices [19,20]. These interconnected drivers intensify drought severity and complicate mitigation and adaptation strategies [14,17,21]. According to the World Bank (2025) Thailand Country Climate and Development Report [22], one of the national priorities is to strengthen integrated provincial water resource management, particularly by enhancing water storage capacity in northern regions. The study area, northern Thailand, lies within the Asian monsoon region, which is characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons, and wet-season precipitation accounts for approximately 70–80% of the annual precipitation [23]. Despite this dominance, the characteristics of dry-season droughts have received limited attention, even though their impacts on regional water availability are substantial [12].

The behavior and severity of hydrological droughts are strongly governed by climate seasonality, catchment storage, and human activities such as groundwater abstraction and reservoir regulation [3,24]. In monsoon-dominated regions, strong wet–dry interactions mean that wet-season deficits directly constrain dry-season water availability [1,24]. Catchments with limited soil or aquifer storage tend to experience rapid drought intensification, whereas those with greater storage buffer short-term variability [1,3]. Although there is a broad consensus on these intensifying risks, accurately quantifying drought propagation at the catchment scale remains challenging. Previous studies have predominantly relied on single-variable indicators such as SPI, SSFI, SDI, and SRSI [25,26,27,28] which assume a linear translation of meteorological deficits into hydrological droughts and therefore cannot represent the nonlinear propagation processes shaped by evapotranspiration and catchment storage. Because no single indicator can capture all dimensions of drought propagation, recent studies have emphasized the need for multivariate integrated indices capable of characterizing system-wide hydrological responses [29].

To address this research gap, this study investigates future hydrological drought conditions in northern Thailand under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios by adopting a multivariate framework that couples physically based hydrological modeling with statistical dimensionality reduction. Specifically, we applied the Composite Hydrological Drought Index (CHDI) [30], synthesized through Principal Component Analysis (PCA), to transcend the limitations of single-indicator reliance. This approach represents a methodological innovation for monsoon-dominated basins in mainland Thailand in three main respects. First, the CHDI provides a comprehensive multidimensional representation of drought capable of detecting structural deficits driven by subsurface constraints, which are not captured by traditional single-indicator indices. Second, it explicitly bridges the gap between scientific diagnostics and operational practice by calibrating index thresholds against the Thailand’s Royal Irrigation Department’s (RID) water-level criteria, thereby embedding national drought management protocols within a process-based hydrological framework. Third, the utilization of high-resolution WRF-downscaled CMIP5 projections significantly enhances the representation of spatial heterogeneity across the complex terrain of northern Thailand. Collectively, this integrated WRF-VIC-CHDI framework constitutes a novel transferable template for basin-scale drought assessment and long-term water resource planning under a changing climate.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The northern watershed of Thailand (15°41′52″–20°27′47″ N, 97°20′42″–101°21′22″ E) encompasses four principal tributaries: the Ping (P.67 gauge), Wang (W.10A gauge), Yom (Y.20 gauge), and Nan (N.64 gauge) rivers (Figure 1). Collectively, these tributaries drain a basin of approximately 107,000 km2 [30]. The individual drainage areas for the Ping, Wang, Yom, and Nan sub-basins are 36,020 km2, 11,700 km2, 24,720 km2, and 34,560 km2, respectively. This region represents one of Thailand’s most critical hydrological systems, sustaining domestic consumption, agriculture, and other socioeconomic activities [31]. A land use analysis based on the 2020 MODIS IGBP classification indicates that croplands cover more than 24% of the watershed (approximately 18,000 km2) [32], encompassing both irrigated and rainfed farmland. Agricultural activities, particularly off-season farming, account for more than 70% of the total water demand [33] and are dominated by the cultivation of water-intensive crops. According to the 2023 Agricultural Census, rice is the predominant crop in northern Thailand (48.4%), followed by field crops (33.0%) and perennial or fruit crops (10.3%) [34]. These patterns underscore the critical dependence of regional livelihoods on consistent water availability.

Figure 1.

Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) map of the Northern Thailand region, delineated into four major watersheds. The classification utilizes the IGBP scheme, as defined in the color-coded legend. White labeled circles indicate the specific locations of the four streamflow gauging stations (P.67, W.10A, Y.20, and N.64) utilized for hydrological drought projections under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 climate scenarios.

Situated within the Southeast Asian monsoon domain [35], the basin experiences two distinct seasons: wet and dry. The timing of seasonal onset and retreat depends on the arrival and withdrawal of monsoon systems over the mainland. Following Moron et al. [36], the wet season is defined as May–October and the dry season as November–April. The northern watershed plays a strategic role in Thailand’s national hydrology as it constitutes a major upstream contributor to the Chao Phraya River Basin [37]. Consequently, water insecurity in the northern watershed, whether from droughts or floods, can trigger cascading impacts at the national level. A notable example is the 2011 extreme flood event in Bangkok, which was partly attributed to abnormally high rainfall in the northern watershed and the subsequent downstream flow into the Chao Phraya River, exacerbating flooding in the capital [38].

2.2. Regional Climate Model

The climate data used in this study were derived from the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model driven by the Community Earth System Model version 1 (CESM1), developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). The WRF model was used for dynamic downscaling. The simulations covered a historical baseline period (1976–2005) and a future projection period (2021–2050) under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios. The detailed WRF model configuration was described by Chotamonsak et al. [39]. The WRF computational domain spanned 5–21° N and 97–106° E (175 × 175 grid points) with a horizontal resolution of 12 km. For model evaluation, observational data from the Climatic Research Unit (CRU) monthly dataset for 1976–2005 at a 0.5° × 0.5° resolution were used. The baseline simulation reproduced precipitation and maximum and minimum temperatures with high accuracy, achieving correlation coefficients of 0.88, 0.83, and 0.91, respectively [39].

2.3. Hydrological Model

The Variable Infiltration Capacity (VIC) model [40] was employed to simulate hydrological variables relevant to drought analysis. The simulated variables included surface runoff (RO), baseflow (Base), soil moisture content across three discrete layers—surface (SL0, <0.1 m), shallow (SL1, 0.1–1.5 m), and deep (SL2, 1.5–2.0 m)—and actual evapotranspiration (ET). ET represents the sum of canopy evaporation, vegetation transpiration, and bare soil evaporation, which is computed using the Penman–Monteith formulation constrained by soil moisture availability and stomatal resistance. In addition to these simulated fluxes, precipitation (PPT) was recorded as an echoed forcing output rather than a variable simulated by the model to ensure water balance consistency and facilitate the verification of forcing–response relationships. For the analysis, all model outputs were aggregated to a monthly time step; precipitation, evapotranspiration, runoff, and baseflow were calculated as monthly sums, whereas soil moisture was calculated as the monthly mean for each layer. All variables were expressed in mm/month.

The model was forced with daily regional climate inputs generated by the WRF–CESM simulations, which provided precipitation, maximum and minimum temperatures, and horizontal wind components (u and v) [39]. All spatial datasets were prepared at a resolution of 0.0625° to align with the VIC model configuration (Table 1), using a subgrid approach with nearest-neighbor resampling, and refined using high-resolution land use/land cover (LULC) data based on the International Geosphere–Biosphere Programme (IGBP) classification scheme [32]. These datasets were compiled to characterize the land surface properties relevant to water storage and flow dynamics. The key parameters included leaf area index, rooting depth, and surface roughness, all of which strongly influenced the infiltration and evaporation processes. Elevation data were obtained from the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) Global Digital Elevation Model (GDEM) version 3 [41], which has a spatial resolution of 30 m at the equator, and were used to derive the slope and flow direction of the watershed. Soil data were sourced from the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD) version 1.2, developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) [42], which provides essential information on soil texture and structure for estimating infiltration capacity.

Table 1.

Specifications of the input datasets utilized for hydrological modeling in the Northern Thailand watersheds.

2.4. Composite Hydrological Drought Index

This study employed the Composite Hydrological Drought Index (CHDI), developed by Lapyai et al. [30], to assess hydrological droughts at gauging stations in Northern Thailand. The CHDI integrates multiple hydrological variables derived from the Variable Infiltration Capacity (VIC) model using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to capture basin-scale drought dynamics. Prior to index calculation, the raw VIC outputs underwent rigorous data-quality control. This process included the identification and removal of extreme values using standard outlier detection techniques to mitigate modeling uncertainty and ensure the robustness of PCA inputs. Subsequently, all variable data were aggregated to a monthly time step for analysis.

PCA was applied to synthesize these correlated variables into a single index. The contribution (or weight) of each variable was determined from the eigenvector loadings of the first principal component (PC1). PC1 was selected because it explained more than 50% of the total variance, thereby effectively representing the dominant surface-driven hydrological processes (precipitation, surface soil moisture, and runoff). The final CHDI values were computed using a linear regression model that translated the composite PC1 signal into an equivalent monthly water-level index. The CHDI is a dimensionless standardized index and therefore has no unit, defined as:

where PC1 is the weighted linear combination of standardized hydrological variables, and β0 and β1 are the regression intercept and slope, respectively, derived from the empirical relationship between PC1 and historical stream water-level observations (m MSL). Crucially, this regression equation was explicitly developed for each individual watershed to accurately capture local hydrological characteristics.

CHDI = β0 + β1 × PC1

The performance of the CHDI was rigorously evaluated in a previous study [30] by comparing the index with historical stream water-level data from the National Hydroinformatics Data Center (NHC) [43] using a calibration (1976–1995) and validation (1996–2005). The index demonstrated robust capability in reproducing observed hydrological conditions. During calibration, the model achieved Pearson correlation coefficients (r) ranging from 0.58 to 0.82 (p < 0.05) and Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) values from 0.32 to 0.66. Similarly, the validation phase exhibited strong agreement, with Pearson correlation coefficients (r) ranging from 0.52 to 0.79 (p < 0.05) and NSE scores from 0.28 to 0.62. The CHDI categories were defined using observed stream water-level percentages relative to the Low Negative Water Level (LNWL) at each station, following the Royal Irrigation Department’s (RID) operational classes of flood, normal, drought risk, and drought (Table 2). This classification framework effectively reproduces the timing, frequency, and duration of drought events by assigning CHDI-based categories that closely correspond to those derived from observed stream water-level records [30]. Such alignment demonstrates that the CHDI reliably reflects the hydrological conditions recorded at each station.

Table 2.

Classification scheme for CHDI categories based on observed stream water-level percentages relative to the LNWL (m MSL).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Time-series analyses were conducted on historical and projected datasets to assess the temporal evolution of the hydrological parameters. The Mann–Kendall (MK) test [44], Sen’s slope estimator, and linear regression trend test [45] were applied for trend detection, following the recommendations of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) [12]. A positive statistic (or slope) indicates an upward trend, whereas a negative statistic indicates a downward trend. These methods enable the identification of long-term trends, periodicities, and potential shifts in drought regimes over time. To characterize the distribution of drought-related variables and their projected changes, probability density functions (PDFs) and cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) were constructed for each simulation scenario [46]. These statistical tools provide insights into the frequency, variability, and extreme tails of drought indicator distributions under varying climatic conditions.

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Hydrological Parameters Under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5

We applied the Mann–Kendall test, a widely used nonparametric method for hydrological time series, to analyze trends in future VIC-simulated projections (2021–2050) at four stations in Northern Thailand. Under RCP4.5 (Table 3), precipitation increased at all stations, with the largest gains in the wet season (May–October); however, some stations (Y.20 and N.64) showed decreasing dry-season (November–April) totals. Neither the annual nor seasonal actual evapotranspiration exhibited a significant trend. Wet-season runoff generally increased, with the strongest signal at W.10A (+0.005 mm/month). Soil moisture increased most clearly in the surface layer (P.67, W.10A) and upper layer (P.67, Y.20, N.64), while increases in lower-layer soil moisture and baseflow were significant only at P.67. Seasonal diagnostics reinforce these patterns: wet-season precipitation increases at Y.20 (+0.077 mm/month) and N.64 (+0.086 mm/month) coinciding with rising runoff, implying elevated flood and flash flood risks in lowland areas. In the dry season, declining precipitation at Y.20 (−0.004 mm/month) and N.64 (−0.004 mm/month), together with limited changes in soil moisture storage, indicates heightened vulnerability of domestic and agricultural water supply.

Table 3.

Projected temporal trends (Mann–Kendall test) and Sen’s slope estimates for hydrological variables across four watersheds in Northern Thailand (P.67, W.10A, Y.20, and N.64) under the RCP4.5 scenario for the period 2021–2050. Trends are categorized by season: Annual, Wet Season (May–Oct), and Dry Season (Nov–Apr). Positive and negative values denote the direction and magnitude of the detected trends (Sen’s slope, mm/month).

Under RCP8.5 (Table 4), the trends were more variable. Annual actual evapotranspiration declined at P.67 (−0.001 mm/month) and N.64 (−0.002 mm/month), whereas wet-season actual evapotranspiration increased at N.64 (+0.115 mm/month). At P.67, precipitation decreased consistently on annual (−0.011 mm/month), wet (−0.064 mm/month), and dry (−0.002 mm/month) seasonal scales. In contrast, W.10A and Y.20 showed an increase in annual and seasonal precipitation. Wet-season runoff continues to increase at most sites. Surface and upper-layer soil moisture increased at W.10A and Y.20 but declined at P.67. Substantial baseflow gains were limited across the catchments.

Table 4.

Projected temporal trends (Mann–Kendall test) and Sen’s slope estimates for hydrological variables across four watersheds in Northern Thailand (P.67, W.10A, Y.20, and N.64) under the RCP8.5 scenario for the period 2021–2050. Trends are categorized by season: Annual, Wet Season (May–Oct), and Dry Season (Nov–Apr). Positive and negative values denote the direction and magnitude of the detected trends (Sen’s slope, mm/month).

Overall, actual evapotranspiration appears particularly sensitive, with annual declines at P.67 and N.64, which may alter regional water cycling. Despite annual precipitation increases at many sites, localized dry season decreases, coupled with stagnant or declining soil moisture at P.67 and N.64, indicate increasing structural drought. Limited baseflow responses further suggest that groundwater reserves may not adequately buffer dry season shortages.

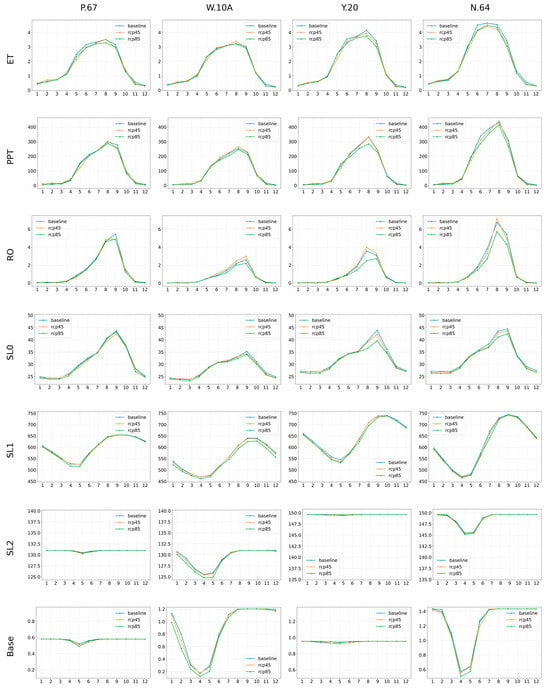

Future monthly projections relative to the baseline (Figure 2) indicated strong monsoonal control with distinct catchment-specific responses. At P.67, projections showed modest declines in precipitation and runoff, earlier dry-season soil moisture depletion, and reduced baseflow, especially under RCP8.5, which is consistent with earlier drought onset and weakened catchment storage buffering. At W.10A under RCP8.5, runoff and soil water storage remained persistently low, with pronounced troughs in shallow and deep layers; even small rainfall reductions caused disproportionate declines in runoff and baseflow, indicating high vulnerability to prolonged deficits. Under RCP4.5, W.10A remains broadly similar to the baseline; precipitation and runoff increase in the wet season, but higher actual evapotranspiration offsets some of the gains. Y.20 exhibited partial resilience under both scenarios, with precipitation and soil water near baseline; however, under RCP8.5, precipitation and runoff declined, reducing recharge and heightening sensitivity to mid-season dry spells. N.64 shows a contrasting response: RCP4.5 enhances peak runoff, whereas RCP8.5 intensifies pre-monsoon soil moisture and baseflow deficits, implying concurrent risks of flooding and severe drought.

Figure 2.

Monthly climatology of key hydrological variables simulated by the VIC model across four watersheds in Northern Thailand. The panels illustrate comparisons between the historical baseline period (1976–2005) and future projections (2021–2050) under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 climate scenarios at stations P.67, W.10A, Y.20, and N.64. The rows correspond to actual evapotranspiration (ET), precipitation (PPT), runoff (RO), baseflow (Base), and soil moisture at three different depths (SL0, SL1, SL2). All variables are expressed in mm.

Collectively, these results highlight the heterogeneous, catchment-specific hydrological responses across northern Thailand, and the hydrograph analysis demonstrates a prevalent surface-driven regime, where the system is primarily governed by rapid surface runoff generation. In contrast, baseflow shows markedly lower responsiveness to precipitation, implying limited natural storage capacity to buffer hydroclimatic variability. Consequently, systems with shallow storage and low baseflow (W.10A and P.67) are prone to rapid drought intensification, whereas higher storage systems (Y.20 and N.64) are more resilient in average years but remain exposed to extremes under the RCP8.5 scenario. This structural limitation exacerbates the intra-annual imbalance; while warming elevates evaporative demand and rainfall variability modulates runoff, the lack of substantial subsurface buffering means that elevated wet-season peak flows (at N.64 and P.67) can coexist with persistent drought (at W.10A) and dry season deficits across all the stations.

3.2. Hydrological Drought Projections Based on CHDI

3.2.1. Temporal Projections

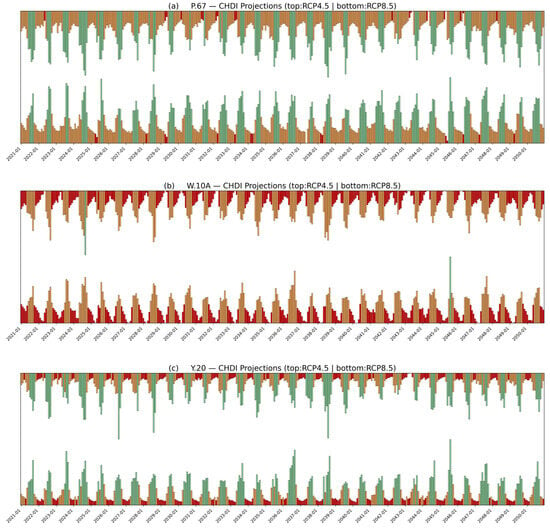

Temporal projections of the Composite Hydrological Drought Index (CHDI) revealed clear spatial and scenario-dependent contrasts across the four stations (P.67, W.10A, Y.20, and N.64). Under RCP4.5, the seasonal cycles remained comparatively stable. At P.67 (Figure 3a), the wet season is dominated by normal conditions with occasional drought-risk, and droughts are typically brief (1–2 months). W.10A (Figure 3b) is the most drought-prone, with multi-month drought episodes spanning both seasons (often 4–9 months) and only infrequent returns to drought-risk or normal. Y.20 (Figure 3c) shows pronounced seasonal stability: the wet season (May–October) is largely normal or drought-risk, followed almost every year by droughts that persist for several months. N.64 (Figure 3d) alternates between normal and drought-risk, with most droughts lasting for 1–2 months.

Figure 3.

Time series of projected monthly CHDI values for the period 2021–2050 across four watersheds in Northern Thailand. The panels illustrate projections under two climate forcing scenarios: RCP4.5 (top row) and RCP8.5 (bottom row). Results are shown for four distinct streamflow gauging stations: (a) P.67, (b) W.10A, (c) Y.20, and (d) N.64. The color-coded vertical bars denote hydrological status: red (drought), orange (drought risk), green (normal), and blue (flood risk).

Under RCP8.5, especially after 2040, wet-season drought intrusions become more frequent and intense. At P.67 (Figure 3a), droughts extend up to three months, drought- risk events increase by approximately one to two per decade, and flood-risk episodes intensify, indicating greater seasonal unpredictability. At W.10A (Figure 3b), both drought duration and severity increased, with dry spells occasionally spanning nearly the entire wet season. At Y.20 (Figure 3c), drought frequency and duration moderately intensified, with events recurring near the onset and cessation of the wet season almost every year; nevertheless, the persistence of normal conditions suggests substantial catchment buffering and soil moisture retention. At N.64 (Figure 3d), hydrological variability increased, with more frequent wet season drought intrusions and severe events (up to three months) becoming more common after 2040; wet season intrusions increased by approximately two to three events per decade relative to RCP4.5.

Overall, RCP4.5 preserves a relatively predictable seasonal cycle: wet seasons are largely normal, and dry seasons feature recurrent but brief droughts relative to the baseline, reflecting modest precipitation increases and broadly stable soil moisture storage. In contrast, RCP8.5 amplifies extremes by raising evaporative demand, advancing and deepening dry-season soil moisture drawdown, and increasing the frequency of wet-season drought intrusions, thereby lengthening drought residence times and shortening recovery intervals. The response is spatially heterogeneous: Y.20 remains comparatively resilient, retaining predominantly normal wet seasons with only moderate increases in drought frequency and duration; P.67 and N.64 exhibit growing instability, with more frequent transitions among normal, drought-risk, drought, and flood-risk, pre-monsoon baseflow deficits, and multi-month droughts becoming more common after 2040; and W.10A experiences the most persistent, long-duration droughts—at times spanning much of the wet season—indicating limited storage and weak baseflow buffering. These patterns highlight the escalating management challenges and the need for catchment-specific measures, such as targeted storage augmentation, conjunctive use of surface and groundwater, and revised off-season irrigation scheduling.

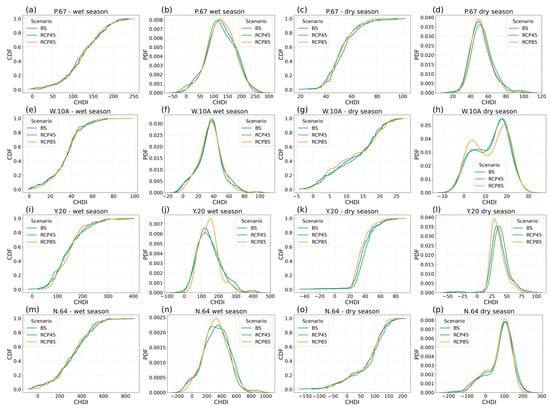

3.2.2. Variability and Extremes

Figure 4 presents the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) and probability density functions (PDFs) of the CHDI for the wet and dry seasons at four gauges—P.67 (Figure 4a–d), W.10A (Figure 4e–h), Y.20 (Figure 4i–l), and N.64 (Figure 4m–p)—under the baseline (1976–2005) and RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios (2021–2050), revealing clear seasonal and spatial contrasts in the central tendency, dispersion, and tail behavior. At P.67, wet-season distributions under RCP8.5 shifted modestly toward higher values: CDFs indicated a greater frequency of large CHDI, whereas PDFs showed a sharper peak near 120–140 and a heavier upper tail, consistent with elevated flood risk. In the dry season, both scenarios shifted toward lower values, most prominently under RCP8.5, which was centered below the baseline mean (~50) with an accentuated lower tail, indicating a higher probability of severe droughts. W.10A remains persistently drought prone: wet-season distributions are tightly clustered between 35 and 45 with minimal variance; under RCP8.5, the upper tail extends slightly, but wetter anomalies remain limited. Dry-season changes were more pronounced, with left-shifted CDFs and bimodal PDFs (peaks near 4–6 and 18–20); RCP8.5 strengthened the lower peak and weakened the higher one, implying more frequent, prolonged severe droughts and reduced recovery potential.

Figure 4.

Probability Density Functions (PDFs) and Cumulative Distribution Functions (CDFs) of monthly CHDI values for four watersheds in Northern Thailand (P.67, W.10A, Y.20, and N.64). The plots compare the historical baseline period (1976–2005, BS: blue lines) with future projections (2021–2050) under two climate forcing scenarios: RCP4.5 (green lines) and RCP8.5 (orange lines). The horizontal axis represents the dimensionless CHDI value, depicting shifts in the frequency and probability of dry (negative values) and wet (positive values) extremes (a–p). (a) P.67 wet-season CDF; (b) P.67 wet-season PDF; (c) P.67 dry-season CDF; (d) P.67 dry-season PDF; (e) W.10A wet-season CDF; (f) W.10A wet-season PDF; (g) W.10A dry-season CDF; (h) W.10A dry-season PDF; (i) Y.20 wet-season CDF; (j) Y.20 wet-season PDF; (k) Y.20 dry-season CDF; (l) Y.20 dry-season PDF; (m) N.64 wet-season CDF; (n) N.64 wet-season PDF; (o) N.64 dry-season CDF; (p) N.64 dry-season PDF.

At Y.20, the wet-season curves remain closely aligned across scenarios; under RCP8 At Y.20, the wet-season curves remain closely aligned across scenarios; under RCP8.5, the CDF shifts slightly rightward and the PDF sharpens around 100–150, indicating a higher frequency of moderately wet conditions, while a shortened upper tail suggests slightly reduced extreme-wet severity. In the dry season, both scenarios shifted toward higher values relative to the baseline, especially under RCP8.5: the CDF moved rightward and the PDF peaked at 25–30 (versus ~20–25 at baseline), indicating wetter dry-season conditions under warming. The RCP8.5 PDF was sharper and narrower, reflecting reduced variance and a tendency toward more persistent wet states. These features indicate greater moisture carryover from the wet season and a comparatively strong storage and buffering capacity in the Y.20 catchment. N.64 exhibited the strongest dual response. In the wet season, CDFs and PDFs shifted markedly toward higher values under both scenarios, especially RCP8.5, with peaks around 300–400 and extended upper tails beyond 800, indicating amplified wet extremes and higher flood risk, along with increased variance, suggesting stronger interannual fluctuations. In the dry season, both scenarios shifted toward lower values, with PDFs being bimodal and dominated by moderate-wet conditions (~100–120), but with an extended lower tail below zero, indicating an increased probability of extreme drought in the near future.

In summary, the results demonstrate pronounced seasonal contrasts and spatial heterogeneity in the projected CHDI behavior. Wet-season extremes intensified primarily at P.67 and N.64 (upper-tail extension), whereas dry-season drought severity increased at P.67, W.10A, and N.64 (enhanced lower-tail risk). Y.20 remains comparatively stable, with only modest wet season changes but a tendency toward wetter dry seasons. Across all stations, RCP8.5 consistently amplified extremes, narrowing distributions in some cases and extending tails in others, indicating that future hydrological drought and flood risks in northern Thailand will intensify in site-specific and seasonally non-uniform ways.

Table 5 summarizes seasonal variations in the CHDI across four stations (P.67, W.10A, Y.20, and N.64) for projection periods under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 (2021–2050) compared to the baseline (1976–2005), revealing distinct wet–dry contrasts and catchment-specific responses. At P.67, the wet-season CHDI remains broadly stable, with minor shifts across scenarios. Under RCP4.5, the 10th percentile increased slightly (0.70%), whereas the median (Q50) and upper bound (Q90) declined modestly (−2.52% and −1.52%, respectively). Under RCP8.5, the lower tail increased more (3.93% at Q10), but Q50 and Q90 decreased, indicating suppressed mid-to-upper variability. The wet-season mean was effectively unchanged (0.01%), suggesting limited alteration in average conditions, with possible implications for flood-prone extremes depending on tail behavior. In the dry season, both scenarios increased Q10 (3–4%), indicating reduced drought severity at the lower bound. The median and Q90 rise modestly (3.79%) under RCP4.5, whereas RCP8.5 shows slight decreases (−1.96%), yielding a negligible change in the seasonal mean.

Table 5.

Statistical comparison of seasonal CHDI characteristics between the historical baseline (1976–2005) and future projections (2021–2050) for four watersheds in Northern Thailand (P.67, W.10A, Y.20, and N.64). The table presents the 10th percentile (Q10; representing dry extremes), median (Q50), 90th percentile (Q90; representing wet extremes), and seasonal averages under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios.

W.10A presented a stronger drought-prone signal. Wet-season CHDI decreased slightly under RCP4.5 (−1.24% on average), whereas RCP8.5 showed only a marginal increase (0.47%). The 10th percentile diverged across scenarios, declining under RCP4.5 (−5.87%) but rising sharply under RCP8.5 (8.56%), indicating greater variability in lower-bound wet season conditions. Dry-season shifts were more pronounced: RCP4.5 reduced the median (−1.93%) but raised the mean (+3.59%), whereas RCP8.5 markedly amplified the lower tail (+80.64% at Q10) despite declines in Q50 (−10.10%). This pattern indicates more frequent and prolonged severe drought episodes alongside suppressed central tendencies, reflecting heightened drought intensity and recurrence.

At Y.20, the wet-season shifts were modest and mixed. Under RCP4.5, the lower bound (Q10) increased slightly (+0.84%), the median was essentially unchanged (−0.27%), and the upper quantile weakened (Q90 −5.26%), resulting in a slight decline in the seasonal mean (−1.96%). Under RCP8.5, the lower and central quantiles increased (Q10 +17.25%; Q50 +7.23%), whereas the upper quantile declined (Q90 −10.75%); the mean edges upward (+1.29%). Together, these changes suggest reduced drought severity at the lower tail and muted extreme wet anomalies at the upper tail in the wet season. In the dry season, RCP4.5 produced a coherent rightward shift across the distribution (Q10 +13.11%, Q50 +10.72%, Q90 +2.68%; mean +7.62%), indicating wetter conditions. In contrast, RCP8.5 shifted the distribution leftward (Q10 −4.09%, Q50 −7.66%, Q90 −7.82%; mean −5.03%), indicating overall drier conditions and heightened exposure to deficits. Overall, Y.20 retained relative resilience, with moderated extremes in the wet season and divergent dry-season responses—wetter under RCP4.5 but drier under RCP8.5.

N.64 exhibited the most pronounced dual response. Wet-season percentiles declined under RCP4.5 (Q10 −13.22%, Q50 −2.09%, Q90 −7.79%), whereas RCP8.5 showed smaller reductions at Q50 (−1.49%) and Q90 (−3.66%) and a slight decrease at Q10 (−2.49%). The mean change was minimal, implying stable seasonal averages, although heightened flood risk remains plausible because of the extended upper tail. In the dry season, responses diverge under RCP4.5, the median and Q90 increase by approximately 4 to 5%, raising the seasonal mean by +8.38%, while the lower bound decreases substantially (−26.83%); under RCP8.5, both Q50 and Q90 decline (−3.35% and −3.93%), and Q10 drops further (−37.15%). This pattern indicates intensifying drought severity under RCP8.5 through an expanded lower-tail risk, despite relatively stable means.

In summary, the wet-season flood risk is projected to increase primarily at P.67 and N.64 under RCP8.5, whereas the dry-season drought-risk intensifies at W.10A and N.64, driven by sharp reductions in the lower tail of the CHDI. Y.20 remains comparatively stable but shows mixed signals: in the wet season, projections indicate a slight decline in the mean; in the dry season, responses diverge—RCP4.5 shifts the distribution rightward, whereas RCP8.5 shifts it leftward. These findings indicate that under RCP8.5, extremes tend to be amplified rather than exhibiting uniform shifts in the mean, underscoring the value of percentile-based diagnostics for characterizing future droughts and flood hazards.

3.3. Projected Hydrological Drought Frequency

The frequency of drought-risk conditions (Figure 5; orange) showed clear seasonal and spatial contrasts across the four stations when comparing the baseline (BS) with RCP4.5 and RCP8.5. In the P.67, wet season occurrences increased under RCP4.5 (64 events) relative to BS (55 events) and decreased slightly under RCP8.5 (58 events), remaining above the baseline. The dry season is persistently drought prone, with counts near or above the baseline (168 events at BS and ≥169 events under projections). At W.10A, drought-risk is concentrated almost entirely in the wet season and remains high and stable (130 events at BS and RCP4.5; 128 events at RCP8.5); no dry-season drought-risk events are observed. Y.20 has relatively low exposure: wet season frequencies decline under RCP8.5 (65 events) compared with BS (80 events) and RCP4.5 (81 events), and dry season frequencies also fall under RCP8.5 (36 events) relative to BS (54 events) and RCP4.5 (62 events). N.64 exhibits dual-season vulnerability: wet-season frequencies increase slightly underr RCP8.5 (83 events) versus BS (77 events) and RCP4.5 (79 events), whereas dry-season countsremaind persistently high (145–148 events) with limited scenario sensitivity.

Figure 5.

Total frequency (number of months) of drought events identified by the CHDI across four watersheds in Northern Thailand (P.67, W.10A, Y.20, and N.64). The panels compare the historical baseline period (1976–2005) with future projections (2021–2050) under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 climate scenarios. The bars represent the total monthly count of months classified into critical categories: Drought (red bars) and Drought-Risk (orange bars).

The frequency of drought conditions (Figure 5; red) also revealed strong seasonal and spatial contrasts. At P.67, wet-season droughts increased slightly under RCP4.5 (10 events) relative to BS (9 events) but declined under RCP8.5 (6 events); dry-season counts were stable (11 events under projections versus 12 events at baseline). At W.10A, drought occurrence was consistently extreme in the dry season and unchanged across scenarios (180 events), whereas wet season drought was moderate and stable (49–51 events). Y.20 shows fewer wet season drought events under RCP8.5 (1 event) than under BS (4 events) or RCP4.5 (5 events), but dry season drought increases under RCP8.5 (144 events) compared with BS (126 events) and RCP4.5 (118 events), indicating a shift from milder to more severe dry season conditions. At N.64, wet-season drought peaks under RCP4.5 (11 events) relative to BS (9 events) and declines under RCP8.5 (4 events), whereas dry-season counts remained elevated and broadly stable (35 events in BS; 32–34 events under projection scenarios).

Overall, scenario-driven differences were most evident in the wet season, with RCP8.5 reducing wet-season exposure at Y.20, slightly elevating drought-risk at N.64, leaving W.10A largely unchanged, and producing modest, mixed changes at P.67. In the dry season, frequencies remained largely unchanged at P.67, W.10A, and N.64 but diverged at Y.20, with declining drought-risk and increasing severe drought under RCP8.5. These patterns underscore the localized, season-dependent drought behavior across northern Thailand.

3.4. Projected Hydrological Drought Duration

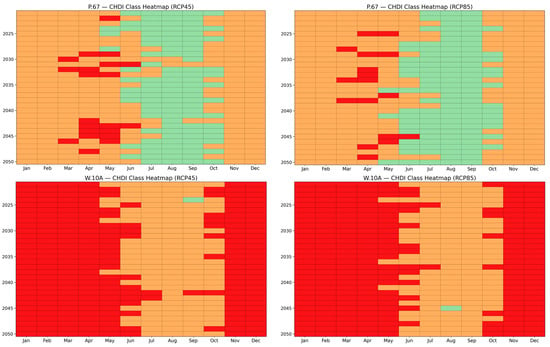

Table 6 reports the maximum consecutive months of drought and drought-risk at each gauge for the baseline, RCP4.5, and RCP8.5 scenarios, respectively. Figure 6 presents heatmaps that reveal distinct spatial and seasonal persistence patterns, including shifts in timing, duration, and intensity. At P.67, drought-risk sequence lengths (orange) increased, with the maximum run increasing from 9 months at baseline and under RCP4.5 to 10 months under RCP8.5. These episodes typically span October to February or March and begin earlier in the projections. Short, severe drought episodes (red) increased from 2 months at baseline to 3 months under RCP4.5, then decreased to 2 months under RCP8.5. The seasonal structure indicates an earlier onset in the late dry season (March–April), occasional incursions into the early monsoon (May–June), and a buffered period during July–September, when conditions are predominantly normal (green). At W.10A, the heatmaps were dominated by drought (red), reflecting severe and persistent conditions. The maximum consecutive drought-risk duration remained at 6 months, whereas the maximum drought duration reached 11 months under RCP4.5, compared with 10 months at baseline and 9 months under RCP8.5. These patterns indicate near-continuous drought in most years, with only brief relief in August–September, often limited to one month.

Table 6.

Maximum consecutive duration (in months) of hydrological drought and drought risk events for four watersheds in Northern Thailand (P.67, W.10A, Y.20, and N.64). The table compares the longest continuous events during the historical baseline (1976–2005) with future projections (2021–2050) under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 climate scenarios. Events are classified according to the CHDI categories.

Figure 6.

Heatmaps of CHDI classifications for four watersheds in Northern Thailand (P.67, W.10A, Y.20, and N.64). The panels illustrate monthly hydrological status during the future projection period (2021–2050) under the two climate forcing scenarios: RCP4.5 and RCP8.5. The color scheme represents the severity of hydrological conditions: red (drought), orange (drought risk), green (normal conditions), and blue (flood risk). The y-axis denotes the simulation years, while the x-axis represents the calendar months (January–December).

Y.20 exhibited a contrasting and more resilient pattern. Drought-risk persistence was 5 months at baseline, remained 5 months under RCP4.5, and decreased to 4 months under RCP8.5. These runs were clustered during the seasonal transitions of October–November and April–May. Drought episodes are centered on the core dry season, lasting several months and typically confined to December–April under RCP4.5 but extending from November to April under RCP8.5, while conditions outside these periods are predominantly normal (green). At N.64, both drought-risk and drought classes exhibited dual-season behavior. The maximum consecutive drought-risk duration reached 10 months at baseline and under RCP8.5, and 9 months under RCP4.5, generally spanning November–February and bridging adjacent pre- and post-monsoon periods. Consecutive drought episodes varied between 4 months at baseline, 5 months under RCP4.5, and 3 months under RCP8.5, with the longest events occurring from January to May under RCP4.5. Under RCP8.5, runs shortened but recurred more frequently, indicating fewer very long events alongside more frequent, intense short-duration events.

Heatmaps and consecutive month analyses showed that climate forcing reshapes not only the frequency but also the timing, duration, and seasonal placement of drought. P.67 shows an earlier onset and occasional intrusion into the early wet season. W.10A remains dominated by nearly year-round droughts with minimal relief. Y.20 exhibits shorter, more seasonally bounded drought-risk persistence under RCP8.5, alongside a longer core dry season drought window. N.64 retains long drought-risk spans with variable drought severity. Under RCP8.5, persistence tended to lengthen at P.67 and remain long at N.64, while W.10A remained chronically drought dominated and Y.20 shifted toward shorter, more confined drought-risk runs but an extended dry-season drought window, underscoring site-specific, seasonally non-uniform persistence under higher emissions.

3.5. Machanisms Driving Future Hydrological Drought Under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5

The future hydrological drought-risk in northern Thailand reflects the combined influence of seasonal water availability, climate variability, and catchment characteristics that govern drought persistence. Under both RCP4.5 and RCP8.5, the contrast between wet and dry season hydrology intensified, and RCP8.5 consistently amplified the extremes. The projected changes showed a pronounced seasonal asymmetry across all stations. During the wet season, the CHDI distributions at P.67 and N.64 shifted to higher values with longer upper tails, indicating a higher likelihood of high-flow or flood-like conditions. During the dry season, the distributions shifted lower, indicating intensified drought. Hydrological parameters supported this pattern. Higher atmospheric evaporative demand in the pre-monsoon period coincides with the earlier depletion of Soil0–Soil2, which advances drought onset and increases early-season event counts.

The station responses remained distinct; W.10A is dominated by chronic drought, with persistently low runoff and baseflow that provided little relief, even in wet months. Y.20 maintains a more balanced regime, with seasonally bounded drought runs and modest CHDI variability, indicating partial resilience. Under RCP4.5, wet-season precipitation increases, while dry-season totals decline, and upper-layer soil moisture rises. CHDI indicates mostly normal wet seasons, followed by dry season droughts lasting several months. Under RCP8.5, precipitation increases overall, but intra-seasonal redistribution reduces effective recharge and runoff near the onset and cessation of the monsoon, producing more frequent transition-season drought intrusions. Surface and upper layer soil moisture remained near baseline or slightly higher, baseflow responses were muted rather than declining, and vulnerabilities persisted during the core dry season and at seasonal transitions.

Variability at the interannual and intra-seasonal scales is projected to intensify. At P.67 and W.10A, even modest precipitation reductions caused disproportionately large declines in runoff and baseflow, increasing the frequency and counts of low-flow events. N.64 showed dual variability, with enhanced wet-season runoff peaks under RCP4.5 and extended dry-season deficits under RCP8.5, underscoring simultaneous flood and drought-risks. Y.20 retains a comparatively stable precipitation–runoff relationship in average years, but under RCP8.5, intra-seasonal redistribution reduces effective recharge near monsoon transitions. Soil moisture in the surface and upper layers remains near baseline or slightly higher, baseflow remains muted, and short, intense transition-season dry spells become more frequent. These changes reshape both the mean and variability of hydrological conditions, widening distributions, and amplifying both tails.

Local catchment attributes strongly shape these results. P.67, with shallow subsurface storage, is highly sensitive to rainfall deficits and tends to rapidly intensify drought. W.10A has weak buffering, with limited soil water and muted baseflow that sustain near-continuous deficits across scenarios and increase drought-event counts. In contrast, Y.20 benefits from greater storage, which delays the onset and buffers short-term variability. Under RCP8.5, intraseasonal redistribution extended the core dry-season drought window rather than producing a mid-monsoon drought, and July to September generally remained normal. At Y.20, the risk therefore concentrates during transition-season dry spells, which can disrupt agricultural operations in the region. N.64 showed a dual-risk profile. Relatively high storage supports resilience in average years, yet extremes are magnified, with strong wet-season runoff peaks under RCP4.5 and prolonged pre-monsoon deficits under RCP8.5, alongside higher counts of both short and occasional long drought events.

Temporal analyses indicate that drought events are likely to lengthen and cluster persistently. For P.67, maximum runs extend into early wet-season months and reach up to 10 consecutive months under RCP8.5. W.10A exhibits near-year-round drought, with spans up to 11 months under RCP4.5 and only brief interruptions during the monsoon peak period. At Y.20, runs shorten and become more seasonally bounded, concentrating in the core dry season and at seasonal transitions rather than in the mid-monsoon. Typical durations are several months from December to March, and they can extend from November to April under RCP8.5, whereas July to September generally remains normal. N.64 alternates between prolonged episodes of up to 10 months and frequent, shorter events. This persistence underscores the combined influence of higher atmospheric moisture demand, intermittent rainfall, and limited baseflow buffering on the structuring of drought clusters across catchments.

Across all stations, the convergence of the CHDI and hydrological analyses points to four dominant mechanistic drivers of future drought behavior. First, increasing atmospheric evaporative demand reduces effective water availability during dry months, shifting the CHDI toward more frequent and persistent drought states in storage-limited watersheds such as P.67 and N.64. Second, greater rainfall variability and short-duration extremes create seasonal asymmetry, with wet-season peaks coexisting with intensified dry-season deficits, particularly under RCP8.5. Third, persistent hydroclimatic regimes with weak buffering, exemplified by W.10A, arise from the combined effects of enhanced evaporative demand and intrinsic geological–geomorphological constraints (narrow and shallow channels, limited subsurface storage, and high sedimentation) [47], which together limit baseflow contributions and sustain long-term structural droughts. Fourth, catchment storage conferred partial resilience at Y.20 by delaying drought onset and buffering short-term variability; however, it could not fully prevent concentrated drought stress during transition periods and within the extended dry-season window under RCP8.5.

Overall, the projected hydrological regime in northern Thailand features amplified extremes, longer persistence, and catchment-dependent vulnerabilities. RCP8.5 increases the frequency and duration of drought episodes, compresses risk into critical agricultural periods, and raises the likelihood of consecutive drought years. These findings support site-specific adaptation, including early-warning systems for structurally drought-prone W.10A, integrated flood-drought management at N.64, and resilience enhancements at P.67 and Y.20 through improved storage, conjunctive use of surface and groundwater, and adaptive irrigation scheduling.

4. Discussion

Climate change is projected to deepen the imbalance between wet and dry seasons in northern Thailand’s watersheds, particularly under RCP8.5. Increases in actual evapotranspiration and greater precipitation variability intensify pre-monsoon and late-season deficits, while simultaneously amplifying wet-season runoff peaks. This pattern aligns with broader evidence that global warming intensifies both droughts and floods through an accelerated hydrological cycle [48,49,50], whereas in northern Thailand, these intensified extremes manifest in a distinctly heterogeneous and seasonally non-uniform manner. A similar imbalance has been reported across Asia, where altered monsoon onset and retreat increase the likelihood of concurrent wet-season flooding and dry-season water stress [51,52,53,54]. At P.67 and N.64, our analysis showed that elevated actual evapotranspiration coincided with declining soil moisture and extended pre-monsoon deficits, underscoring the growing challenge of managing water resources under conditions of simultaneous excess and scarcity in the future.

Beyond shifts in the mean conditions, our projections highlight the amplification of hydrological variability and extremes. Precipitation and runoff distributions broadened, whereas soil moisture and baseflow showed stronger fluctuations under RCP8.5. These dynamics suggest greater exposure to compound hazards, such as flash droughts and flood surges [55], which have been increasingly documented across monsoon-dominated regions [56,57,58]. This mirrors the findings in the Mekong Basin, where climate forcing has been linked to wider interannual variability and clustering of drought-flood sequences [59,60,61,62]. Such instability undermines conventional water management strategies that assume relatively predictable seasonal cycles, reinforcing the need for flexible reservoir operations, adaptive cropping calendars, and integrated drought-flood risk frameworks to ensure water security in the region.

The contribution of this study is the identification of heterogeneous catchment-specific sensitivities and risk profiles. W.10A exemplifies a structurally drought-prone watershed, with persistently low CHDI across scenarios, consistent with evidence that local hydrogeologic constraints can lock catchments into chronic water stress [63,64,65]. In contrast, Y.20 demonstrates relative resilience, as comparatively greater storage and buffering reduce the sensitivity to external forcing. Drought clustering occurs in the core dry season and at seasonal transitions, and under RCP8.5, the dry-season window can extend from November to April, creating episodic risks to agricultural production. N.64 highlights the dual-risk profile, with wet-season flood potential and dry-season drought vulnerability both intensifying, similar to the findings in the Yangtze basins, where watersheds exhibit exposure to multiple extremes under climate change [66,67,68]. These catchment-specific contrasts underscore the need for adaptation tailored to local hydroclimatic conditions rather than relying on uniform strategies.

The integration of CHDI trends with analyses of hydrological parameters points to several mechanistic drivers that shape future drought regimes. First, warming-induced actual evapotranspiration demand accelerates soil moisture depletion, particularly in shallow layers, advancing drought onset, a pattern that is consistent with global flash drought studies [69,70,71,72]. Second, precipitation variability and short-duration extremes promote an intra-annual imbalance in water availability, with compound drought-flood risk arising within the same hydrological year [73,74], consistent with observations from monsoon-dominated India [75,76]. Third, catchment storage and baseflow buffering are critical determinants of resilience, distinguishing stations such as Y.20 from W.10A, and echoing findings from drought resilience studies in the Mekong and Yangtze basins [77,78,79]. The temporal persistence of drought sequences reflects how climate forcing reorganizes not only intensity but also timing, compressing episodes into agriculturally critical months, such as July–September. This sequencing effect has been highlighted in Southeast Asian climate impact studies, where drought clustering threatens food security [80,81,82].

The projected amplification of droughts and floods has significant implications for water resources and agricultural planning. Prolonged droughts under RCP8.5, particularly at W.10A, threaten irrigation security and staple crop yields, whereas enhanced wet-season peaks at N.64 complicate reservoir operations and downstream floodplain management. Similar challenges have been documented in the Chao Phraya Basin, where intensified extremes strain multipurpose reservoir systems [83,84,85]. From a governance perspective, these findings support catchment-specific adaptation [86,87]. Early warning systems and drought contingency planning are critical for structurally vulnerable watersheds (e.g., W.10A), whereas integrated flood- and drought-risk frameworks are required for dual-risk sites such as N.64. Long-term adaptation should also align agricultural strategies with the emerging temporal clustering of drought episodes to ensure resilient cropping systems under shifting monsoon dynamics.

Limitations and Future Work

This study advances drought assessment by integrating VIC-based hydrological modeling with a composite drought hydrological index (CHDI) and catchment-specific diagnostics to capture the multidimensional nature of future drought risks. However, several limitations warrant caution. First, regarding climate inputs, residual biases in climate forcing may persist despite bias corrections. Moreover, the baseline period (1976–2005) reflects the most reliable dataset available at the time of the model development; however, more recent multi-decadal climate datasets should be incorporated into future studies to capture post-2005 warming signals. Second, dynamic land use change, groundwater–surface water interactions, and socioeconomic drivers were not explicitly represented. Consequently, the modeled hydrological drought does not capture demand-side feedback that may amplify or attenuate drought impacts. Third, the spatial resolution of the projections may obscure local heterogeneity, while sparse long-term observations constrain independent validation. Uncertainties inherent in bias-corrected climate inputs, particularly in rainfall intermittency, extremes, and persistence, inevitably propagate into the simulated hydrological responses. Furthermore, the decision to use CMIP5–RCP forcing introduces scenario uncertainty. While this choice maintains consistency with the VIC–CHDI development framework and existing hydrological datasets in Thailand, it is acknowledged that future studies should incorporate CMIP6–SSP projections as soon as hydrology-ready bias-corrected datasets become available.

Regarding the index structure, the CHDI was designed as a context-specific drought index, with thresholds calibrated to the operational water-level criteria of Thailand’s Royal Irrigation Department (RID). This design ensures strong local relevance but limits its broader generalizability. Although preliminary analyses indicate that seasonal drought patterns are robust, modest shifts in catchment-specific thresholds may influence categorical assignments near transition boundaries. Given the hydraulic dependence of water levels on channel geometry, future studies with improved data availability should prioritize converting water levels to discharge using verified rating curves. In addition, systematic benchmarking against established drought indices was beyond the scope of the present study and should be pursued in future studies to more fully situate the CHDI within broader hydrological and drought assessment frameworks. The PCA-based weighting scheme and multistep processing chain also introduce cumulative sources of uncertainty that should be carefully considered when interpreting the results.

Finally, the persistence of long-term structural droughts in basins such as W.10A likely reflects a combination of climatic forcing and intrinsic geological–geomorphological constraints (e.g., limited storage capacity, shallow channels, and sedimentation). Rigorous separation of climate-driven and structural contributions was not feasible within the current modeling framework. Therefore, future research should incorporate CMIP6–SSP scenarios, explicitly represent land use and groundwater processes, refine spatial downscaling, conduct multi-index intercomparisons, and validate CHDI-based diagnostics through sustained field monitoring and catchment-specific water-balance attribution analyses.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that future hydrological droughts in northern Thailand will be increasingly shaped by seasonal imbalances, amplified variability, and catchment-specific vulnerabilities. Under RCP8.5, higher atmospheric evaporative demand and greater rainfall variability led to concurrent wet-season peaks at some stations and deeper dry-season deficits, alongside more frequent wet-season drought intrusions near the onset and cessation of the monsoon. P.67 and N.64 exhibited dual exposure to floods and droughts, W.10A remained persistently drought prone, and Y.20 showed relative resilience owing to stronger storage and buffering. At Y.20, drought clustering is concentrated in the core dry season and at seasonal transitions rather than in the mid-monsoon, and under RCP8.5, the dry-season window can extend from November to April. The governing mechanisms include seasonal imbalance with earlier onset and more frequent transition-season intrusions, amplified variability reflected in larger fluctuations in runoff and soil water, and catchment properties such as storage depth and baseflow buffering. These factors explain the persistent drought propensity at P.67 and W.10A, conditional resilience at Y.20, and dual susceptibility at N.64, highlighting the need for localized analyses and tailored adaptation.

Integrating CHDI projections with hydrological simulations indicates that climate forcing alters not only the mean water availability but also the timing, duration, and clustering of drought events. Prolonged dry spells compressed into agriculturally sensitive months, together with the co-occurrence of flood peaks and extended pre-monsoon deficits, suggest that hydrological droughts will increasingly manifest as a compound hazard. These dynamics arise from a combination of atmospheric drivers and catchment-scale controls. On the atmospheric side, higher evaporative demand and more intense rainfall pulses play a central role, whereas at the catchment scale, limited storage, weak baseflow response, and heterogeneous soil–aquifer properties reduce the buffering capacity of the system. Together, these factors underscore that total annual precipitation alone is insufficient to explain future water stress in the region. The study also highlights that the CHDI provides a physically based and operationally relevant metric for identifying shifts in drought persistence and seasonal timing, although its application remains region-specific and would benefit from future benchmarking against additional hydrological indices and expanded climate baselines.

The CHDI emerges as a robust alternative index that reliably reflects the hydrological conditions at each station because the thresholds are grounded in RID’s water-level definitions. The CHDI can also serve as a decision-support tool for other government agencies, including the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, the Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, and local administrative organizations. This capability effectively bridges the gap between scientific findings and practical, cross-sectoral water resource planning. Overall, the findings emphasize that adaptation strategies must be tailored to local hydroclimatic regimes rather than being applied uniformly. Strategic priorities must therefore include strengthening early warning systems, enhancing water storage and retention capacities, and adopting integrated flood and drought management strategies to sustain water security and agricultural productivity under future climate scenarios. Future research should incorporate multi-index comparisons, groundwater–surface water interactions, and threshold-sensitivity analyses to further refine drought diagnostics and support basin-specific planning under a warming climate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L. and C.C.; methodology, D.L. and C.C.; software, D.L. and C.C.; validation, D.L.; formal analysis, D.L. and C.C.; investigation, D.L.; resources, C.C.; data curation, D.L. and C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.; writing—review and editing, D.L., C.C., A.L. and S.C.; visualization, D.L.; supervision, C.C., A.L. and S.C.; project administration, C.C. and funding acquisition, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Thailand–China collaborative research project “Climate Change and Climate Variability Research in Monsoon Asia (CMON3)”, funded by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), grant numbers N10A640315 and N10A650843, with partially supported by Chiang Mai University (CMU).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article materials. Further inquiries should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to express their sincere gratitude to Wang Lin from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), for supporting a visiting scholar position that enabled collaborative research on drought studies in the Southeast Asia. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, 2025) to refine the academic writing and enhance the readability. The authors have thoroughly reviewed, verified, and edited all AI-assisted outputs and take full responsibility for the final content of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van Loon, A.F. Hydrological Drought explained. WIREs Water 2015, 2, 359–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meresa, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, J.; Faiz, M.A. Understanding the role of catchment and climate characteristics in the propagation of meteorological to hydrological drought. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 128967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Deng, Q.; Fan, J.; Wang, X. Temporal and Spatial Propagation Characteristics of the Meteorological, Agricultural and Hydrological Drought System in Different Climatic Conditions within the Framework of the Watershed Water Cycle. Water 2023, 15, 3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Palomino, C.A.; Hattermann, F.F.; Krysanova, V.; Vega-Jácome, F.; Lavado, W.; Bronstert, A. Climate Change Impact on Water Budget and Hydrological Extremes across Peru. In Proceedings of the EGU23, the 25th EGU General Assembly, Vienna, Austria, 23–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kassaye, S.M.; Tadesse, T.; Tegegne, G.; Hordofa, A.T. Quantifying the climate change impacts on the magnitude and timing of hydrological extremes in the Baro River Basin, Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 2024, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Peña-Angulo, D.; Beguería, S.; Domínguez-Castro, F.; Tomás-Burguera, M.; Noguera, I.; Gimeno-Sotelo, L.; El Kenawy, A. Global drought trends and future projections. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2022, 380, 20210285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Chen, J.; Shi, X.; Kim, J.; Xia, J.; Zhang, L. Impacts of Global Climate Warming on Meteorological and Hydrological Droughts and Their Propagations. Earth’s Futur. 2022, 10, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Future Global Climate: Scenario-Based Projections and Near-Term In-formation. In Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Tu, X.; Singh, V.P.; Chen, X.; Lin, K. Global data assessment and analysis of drought characteristics based on CMIP6. J. Hydrol. 2021, 596, 126091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Xiao, Z.-N.; Nguyen, M. Projection on precipitation frequency of different intensities and precipitation amount in the Lancang-Mekong River basin in the 21st century. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2021, 12, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Liu, H.; Baiyinbaoligao; Hu, H.; Khan, M.Y.A.; Wen, J.; Chen, L.; Tian, F. Future projection of seasonal drought characteristics using CMIP6 in the Lancang-Mekong River Basin. J. Hydrol. 2022, 610, 127815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promping, T.; Tingsanchali, T. Effects of Climate Change and Land-Use Change on Future Inflow to a Reservoir: A Case Study of Sirikit Dam, Upper Nan River Basin, Thailand. GMSARN Int. J. 2022, 16, 366–376. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, B.; Yang, D.; Wang, T.; Yang, Y.; Ma, T.; Santisirisomboon, J. Future changes in water resources, floods and droughts under the joint impact of climate and land-use changes in the Chao Phraya basin, Thailand. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amognehegn, A.E.; Nigussie, A.B.; Adamu, A.Y.; Mulu, G.F. Analysis of future meteorological, hydrological, and agricultural drought characterization under climate change in Kessie watershed, Ethiopia. Geocarto Int. 2023, 38, 2247377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Han, Z.; Wang, Y. Projection of Future Droughts across the Lancang-Mekong River under a Changing Environment. Shuikexue Jinzhan/Adv. Water Sci. 2022, 33, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyhirun, C.; Promping, T. Future hydrological drought hazard assessment under climate and land use projections in Upper Nan River Basin, Thailand. Eng. Appl. Sci. Res. 2021, 48, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, C.; Nieto, R.; Linares, C.; Díaz, J.; Gimeno, L. Effects of droughts on health: Diagnosis, repercussion, and adaptation in vulnerable regions under climate change. Challenges for future research. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 134912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiguchi, M.; Takata, K.; Hanasaki, N.; Archevarahuprok, B.; Champathong, A.; Ikoma, E.; Jaikaeo, C.; Kaewrueng, S.; Kanae, S.; Kazama, S.; et al. A review of climate-change impact and adaptation studies for the water sector in Thailand. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 23004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojpratak, S.; Supharatid, S. Regional extreme precipitation index: Evaluations and projections from the multi-model ensemble CMIP5 over Thailand. Weather. Clim. Extremes 2022, 37, 100475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammadid, W.; Nantasom, K.; Sirksiri, W.; Vanitchung, S.; Promjittiphong, C.; Limsakul, A.; Hanpattanakit, P. Future Projections of Precipitation and Temperature in Northeast, Thailand using Bias-Corrected Global Climate Models. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2023, 50, e2023041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Thailand Country Climate and Development Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. Flood Prevention and Drought Relief in Mekong River Basin. In Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hund, S.V.; Allen, D.M.; Morillas, L.; Johnson, M.S. Groundwater recharge indicator as tool for decision makers to increase socio-hydrological resilience to seasonal drought. J. Hydrol. 2018, 563, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangthong, S.; Chaowiwat, W.; Sarinnapakorn, K.; Chaibandit, K. Prediction of Future Drought in Thailand under Changing Climate by Using SPI and SPEI Indices. Mahasarakham Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2020, 6, 14456. [Google Scholar]

- Pandhumas, T.; Kuntiyawichai, K.; Jothityangkoon, C.; Suryadi, F.X. Assessment of Climate Change Impacts on Drought Se-verity Using Spi and Sdi over the Lower Nam Phong River Basin, Thailand. Eng. Appl. Sci. Res. 2020, 47, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thavorntam, W.; Saengavut, V.; Armstrong, L.J.; Cook, D. Association of farmers’ wellbeing in a drought-prone area, Thailand: Applications of SPI and VCI indices. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, H. An Wiener Process Perfermance Degradation Model with Two Transformed Time Scales Function. Hangkong Dongli Xuebao/J. Aerosp. Power 2018, 33, 2235–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.; Tian, L.; Disse, M.; Tuo, Y. A new approach to quantify propagation time from meteorological to hydrological drought. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapyai, D.; Chotamonsak, C.; Chantara, S.; Limsakul, A. Developing a Composite Hydrological Drought Index Using the VIC Model: Case Study in Northern Thailand. Water 2025, 17, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, D.; Holman, I.; Sutcliffe, C.; Salmoral, G.; Pardthaisong, L.; Visessri, S.; Ekkawatpanit, C.; Rey, D. The contribution of a catchment-scale advice network to successful agricultural drought adaptation in Northern Thailand. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2022, 380, 20210293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, M.; Sulla-Menashe, D. MCD12C1 MODIS/Terra+Aqua Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 0.05Deg CMG V006 [Data Set]; NASA Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwanmuang, P.; Chinram, R.; Panityakul, T. The hydrological and water level data in Yom River basin of Thailand. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2020, 10, 3026–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistical Office Thailand (NSO). The 2023 Agricultural Census: Northern Thailand; National Statistical Office Thailand (NSO): Bangkok, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ummenhofer, C.C.; Geen, R.; Denniston, R.F.; Rao, M.P. Past, Present, and Future of the South Asian Monsoon. In The Indian Ocean and its Role in the Global Climate System; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 49–78. [Google Scholar]

- Moron, V.; Oonariya, C.; Siwapornchai, C.; McBride, J.L. Reconciling Different Views on the Onset of Boreal Summer Monsoon: The Example of Thailand. Int. J. Clim. 2025, 45, 8862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanapakpawin, P.; Boonya-aroonnet, S.; Chankarn, A.; Chitradon, R.; Snidvongs, A. Chapter 7 Thailand Drought Risk Management: Macro and Micro Strategies; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2011; pp. 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Komori, D.; Nakamura, S.; Kiguchi, M.; Nishijima, A.; Yamazaki, D.; Suzuki, S.; Kawasaki, A.; Oki, K.; Oki, T. Characteristics of the 2011 Chao Phraya River flood in Central Thailand. Hydrol. Res. Lett. 2012, 6, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotamonsak, C.; Lapyai, D.; Limsakul, A.; Torsri, K.; Thanadolmethaphorn, P.; Nakapan, S. Evaluation of WRF-Downscaled CMIP5 Climate Simulations for Precipitation and Temperature over Thailand (1976–2005): Implications for Adaptation and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Wood, E.F.; Burges, S.J. A Simple Hydrologically Based Model of Land Surface Water and Energy Fluxes for GSMs. J. Geophys. Res. 1994, 99, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Crippen, R. ASTER GLOBAL DEM (GDEM) VERSION 3. ISPRS-Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, XLIII-B4-2, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IIASA; ISRIC; ISSCAS. JRC Harmonized World Soil Database; Version 1.2; ESDAC: Ispra, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Hydroinformatics Data Center (NHC). Hydro Situation: Water Level. Available online: https://www.thaiwater.net/water/wl (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Emons, W.; Sijtsma, K. Nonparametric Statistical Methods. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Helsel, D.R.; Hirsch, R.M.; Ryberg, K.R.; Archfield, S.A.; Gilroy, E.J. Statistical methods in water resources. In Techniques and Methods; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; p. 458. [Google Scholar]

- Anis, M.R.; Sauchyn, D.J. Ensemble Climate and Streamflow Projections for the Assiniboine River Basin, Canada. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenlerkthawin, W.; Namsai, M.; Bidorn, K.; Rukvichai, C.; Panneerselvam, B.; Bidorn, B. Effects of Dam Construction in the Wang River on Sediment Regimes in the Chao Phraya River Basin. Water 2021, 13, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Working Group I Contribution to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Trenberth, K.E.; Fasullo, J.T.; Shepherd, T.G. Attribution of Climate Extreme Events. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beevers, L.; White, C.J.; Pregnolato, M. Editorial to the Special Issue: Impacts of Compound Hydrological Hazards or Extremes. Geosciences 2020, 10, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.P.; Shrestha, D.; Adhikari, M. Characterizing natural drivers of water-induced disasters in a rain-fed watershed: Hydro-climatic extremes in the Extended East Rapti Watershed, Nepal. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, Y.; Felfelani, F.; Satoh, Y.; Boulange, J.; Burek, P.; Gädeke, A.; Gerten, D.; Gosling, S.N.; Grillakis, M.; Gudmundsson, L.; et al. Global terrestrial water storage and drought severity under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]