Abstract

Accurate forecasting of agricultural drought is vital for enhancing agricultural resilience and optimizing water resource management. Although deep learning models like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) have shown promise in drought prediction, their performance is often constrained by the high dimensionality and varying relevance of input meteorological and soil variables. Standard models treat all input features equally, lacking a mechanism to dynamically prioritize the most informative drivers of soil moisture dynamics. To address this limitation, this study introduces a novel feature recalibration encoder placed between the input and the core prediction model. This encoder leverages a fully connected layer and Softmax activation to generate importance weights for input features, which are then used to enhance the original input via a residual connection, thereby guiding the model to focus on critical signals. We integrated this encoder into three drought forecasting frameworks (targeting soil moisture, SWDI, and drought levels) and four LSTM architectures (LSTM, AttLSTM, EDLSTM, and AEDLSTM) to forecast conditions 1–14 days ahead. Using SMAP-L3 and ERA5-Land data across Guangdong Province, our results demonstrate that models equipped with the proposed encoder consistently outperform their standard counterparts, particularly in capturing extreme drought events. For instance, the encoder-enhanced AEDLSTM model in framework B has significantly improved the 7-day prediction accuracy for severe drought situations. These results highlight that adaptive feature recalibration is a critical step for advancing regional drought forecasting, offering a refined approach that aligns data-driven insights with the dynamic nature of drought evolution.

1. Introduction

Drought is among the most destructive natural disasters, with wide-ranging impacts on agriculture, industry, and society [1,2]. It is typically classified into four types: meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and socio-economic drought [3]. This study focuses on agricultural drought, defined as a prolonged deficit in precipitation that leads to a significant reduction in soil moisture (SM), ultimately impairing crop growth and yields [4,5,6]. China is particularly vulnerable to agricultural drought, which threatens both food security and socio-economic stability. Government data indicate an average annual grain loss of 25.9 billion kilograms—enough to feed approximately 60 million people—due to drought [7]. Southern China, and especially Guangdong Province, frequently experiences seasonal droughts driven by complex monsoon patterns, topography, and hydrological conditions [8]. The 2020–2021 drought in Guangdong was the region’s most severe in nearly 60 years, marked by exceptionally low precipitation and widespread impacts [9]. These challenges highlight the urgent need for more accurate and timely drought prediction to strengthen local resilience, support water resource planning, and reduce the effects of drought events.

The core of agricultural drought monitoring lies in the accurate assessment of soil moisture (SM) dynamics [10,11,12,13]. Recent advances in satellite remote sensing (e.g., NASA’s SMAP-L3) and reanalysis datasets (e.g., ERA5-Land) have provided abundant, high-dimensional data for this purpose, encompassing atmospheric variables (e.g., temperature, precipitation, humidity), land surface states, and static features [14,15,16,17]. This data richness, however, presents a significant challenge: not all input features are equally relevant for predicting soil moisture and drought severity at all times. The drivers of drought evolution are dynamic; for instance, precipitation deficit might be the primary driver in the early stage, while high temperature and evapotranspiration become dominant during a prolonged event. Standard deep learning models, including LSTMs, typically process all input features uniformly without explicit prioritization [18,19]. This can lead to models being overwhelmed by redundant or less informative signals, thereby limiting their predictive accuracy and generalization ability, especially for extreme events.

While previous studies have focused on improving model architectures (e.g., using attention mechanisms to weight different time steps [20]) or comparing data sources [21], the fundamental issue of adaptive feature importance at the input level remains largely unaddressed in the context of drought forecasting. A model that can automatically and dynamically recalibrate its focus on the most pertinent input features could more effectively extract the true signals of impending drought from the complex, multivariate input space.

To bridge this gap, this study proposes a feature recalibration encoder that acts as an intelligent gateway between the raw input data and the subsequent sequence model. This module is designed to explicitly model the inter-dependencies between feature channels, assigning context-aware weights to amplify important features and suppress less useful ones before the sequence modeling stage. We hypothesize that this preprocessing step will significantly enhance the model’s representational power and focus.

Early drought prediction methods mainly relied on statistical models such as the Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA), Seasonal ARIMA (SARIMA), and regression analysis, commonly applied to forecast the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) [22,23]. With advances in machine learning, methods such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) have improved forecasting accuracy [24]. Hybrid models that integrate wavelet transforms with ARIMA and ANN have further enhanced performance [25]. Nonetheless, these approaches often struggle with data limitations, overfitting, and restricted generalizability [26,27]. In recent years, deep learning (DL) has emerged as a powerful tool for climate and drought prediction, benefiting from increased data availability and computing capacity [28,29]. Among DL architectures, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are particularly effective for time series modeling, as they can capture long-term dependencies through gated memory mechanisms [30,31]. LSTM-based models have shown superior performance in predicting drought-related variables such as SM [32,33]. However, most existing studies focus on continuous index prediction, offering limited support for converting these forecasts into discrete drought levels—an important need for practical, policy-oriented decision-making. Furthermore, few studies have assessed how different SM data sources influence model performance under varying conditions.

To address these gaps, this study introduces three deep learning frameworks designed to predict different drought-related targets: SM, SWDI, and drought severity levels. Each framework incorporates four LSTM variants: standard LSTM, Attention-based LSTM (AttLSTM), Encoder–Decoder LSTM (EDLSTM), and Attention-based Encoder–Decoder LSTM (AEDLSTM). Using rolling 365-day sequences of meteorological and soil data as inputs, the models forecast drought conditions from 1 to 14 days ahead. By systematically evaluating model performance across different input data sources (SMAP-L3 and ERA5-Land), this study aims to develop more accurate, timely, and actionable tools for agricultural drought forecasting.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

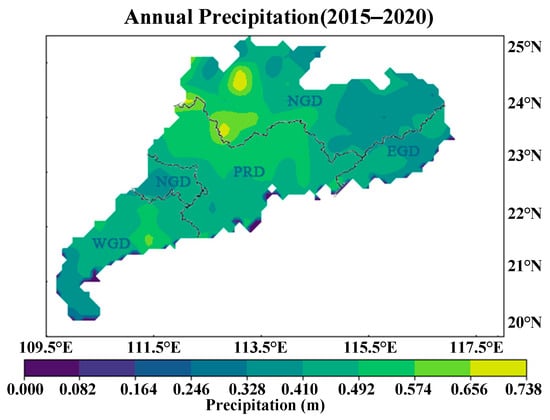

This study focuses on Guangdong Province and its surrounding regions, located along the southern coast of China between 20°–26° N latitude and 109°–118° E longitude. Situated within the East Asian monsoon zone—one of China’s three major climatic regions—Guangdong is particularly prone to meteorological hazards, including droughts and floods [34].

Climatological data indicate that Guangdong has a multi-year average temperature of 21.8 °C, characterized by hot summers, mild winters, and consistently high annual temperatures [35]. The province is commonly divided into four subregions based on geographic and socioeconomic characteristics: the Pearl River Delta (PRD), Eastern Guangdong (EGD), Western Guangdong (WGD), and Northern Guangdong (NGD). Figure 1 shows this regional division alongside the spatial distribution of annual precipitation derived from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset, illustrating generally abundant rainfall across the province. Despite the overall high precipitation, water resources in Guangdong are unevenly distributed, leading to frequent regional and seasonal droughts. Precipitation varies significantly across both space and time, with approximately 80% of annual rainfall concentrated in the monsoon season from April to September. The remaining months are considerably drier, increasing the likelihood of drought. Northern and western areas—particularly cities such as Heyuan and Meizhou—receive substantially less rainfall than southeastern coastal regions, making them more vulnerable to prolonged dry periods. In contrast, low-lying coastal zones are more frequently affected by flooding [36].

Figure 1.

The mean annual precipitation in Guangdong from 2015 to 2020.

Guangdong has a long history of drought events. One of the most severe in recent decades occurred from October 2020 to May 2021, lasting eight months and spanning three seasons: autumn, winter, and spring. During this period, the province received just 449.5 mm of precipitation—44% below the long-term average of 799.9 mm. This marked the second-lowest recorded precipitation for the same timeframe, following the 1962–1963 drought, when rainfall dropped to 309.2 mm [37]. The intensity and duration of the 2020–2021 drought were highly unusual, causing substantial impacts on agriculture, regional economies, and the ecological environment. These challenges underscore the urgent need for effective drought severity forecasting to support risk mitigation and resource planning in Guangdong.

2.2. Data Source

In this study, we utilize reanalysis and remote sensing data. Table 1 lists the input variables for model training including atmosphere data (e.g., temperature, wind speed, precipitation, surface pressure, specific humidity), land surface variables (e.g., radiation, soil temperature, evapotranspiration, NDVI), and static features (e.g., digital elevation model (DEM), land cover type, and soil texture). Surface SM is used as one of the prediction targets. The model is trained on data from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2019, and evaluated using data from 1 January to 31 December 2020.

Table 1.

Explanation of the variables employed.

2.2.1. ERA5-Land Dataset

The ERA5-Land dataset, developed by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), provides high-resolution reanalysis data on land surface variables from 1981 to near real-time. This dataset offers hourly observations at a spatial resolution of 0.1° × 0.1° (9 km × 9 km), covering a wide range of variables relevant to hydrologic modeling, including SM, soil temperature, precipitation, and evapotranspiration [38].

For this study, ERA5-Land data were extracted for Guangdong Province and adjacent regions (109°–118° E, 20°–26° N). To ensure consistency and quality, the data were subjected to a series of preprocessing steps. These included format conversion to standardize input structures, outlier removal to eliminate anomalous values, and normalization to scale variables for improved model performance. Following preprocessing, a subset of variables most relevant to drought analysis—such as precipitation and surface radiation—was selected to support the development of drought level prediction models.

2.2.2. SMAP-L3 Dataset

The SMAP-L3 mission, launched by NASA in 2015, is the first Earth-observing satellite designed to provide continuous global measurements of surface SM and freeze/thaw states. The SMAP-L3 product delivers gridded SM data every 2–3 days at a spatial resolution of approximately 36 km (0.4° × 0.4°) [3,39].

Despite its high temporal frequency, the satellite’s revisit cycle introduces spatial and temporal gaps between observations [40]. To address this limitation and ensure data continuity, we applied random forest interpolation to estimate missing values [41]. This step preserves the completeness of the dataset and minimizes disruptions to model performance.

2.2.3. AVHRR GIMMS-3G+

The GIMMS (Global Inventory Modeling and Mapping Studies) NDVI data is the latest global vegetation index change data launched by Pinzon et al. in November 2003 [42]. This dataset covers the global vegetation index changes from 1981 to 2022. It is in the ENVI standard format, with a time resolution of 15 days and a spatial resolution of 8 km. The GIMMS NDVI data records the regional vegetation changes over 22 years in the format of satellite data. Currently, there are two versions of GIMMS data: the NASA 2GSFC version and the University of Maryland version. The main difference between the two is the data file management, and the quality difference is not significant.

2.3. Model Development

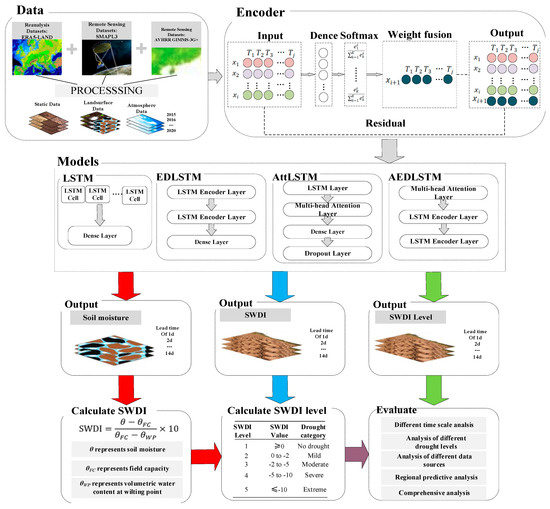

Although deep learning has demonstrated strong potential in agricultural drought forecasting, most existing studies have focused on predicting continuous drought indices, with limited efforts to translate these predictions into actionable drought level classifications. Additionally, few have systematically assessed the influence of different SM data sources—such as remote sensing and reanalysis products—on prediction performance. This limits the operational utility of such models in early warning systems and decision-making tools. To address these gaps, this study proposes three deep learning-based forecasting frameworks, before this, we inserted a feedforward attention mechanism (FAM), which implements a “dynamic feature re-calibration”, enabling the model to automatically learn and emphasize important features while suppressing secondary features, each targeting a different prediction objective: surface SM, the SWDI, and drought severity level (SWDI Level). By varying the target variable, the frameworks are designed to explore the strengths and limitations of different modeling strategies. Each framework is implemented using four LSTM-based architectures—standard LSTM, AttLSTM, EDLSTM, and AEDLSTM—to evaluate the impact of network structure on drought prediction accuracy and robustness.

To ensure the robustness and reliability of our comparative results, each unique model configuration—defined by the combination of forecasting framework (FWA, FWB, FWC), LSTM architecture (LSTM, AttLSTM, EDLSTM, AEDLSTM), input data source (ERA5-Land, SMAP-L3, AVHRR GIMMS-3G+), and forecast lead time (1, 3, 7, 14 days)—was trained and evaluated using a 5-fold cross-validation scheme. Additionally, to account for the inherent randomness in deep learning model initialization and training, we conducted three independent runs for each experiment with distinct random seeds.

The performance metrics reported in the Results section—including Accuracy (ACC), Correlation Coefficient (R), unbiased Root Mean Squared Error (ubRMSE), and Bias—are presented as the mean values averaged across all five folds and three runs, accompanied by the standard deviation (e.g., 0.878 ± 0.015). This approach mitigates the risk of conclusions being based on a single, potentially anomalous model run and provides a more stable and trustworthy assessment of model performance.

2.3.1. Soil Water Deficit Index (SWDI)

Agricultural drought is primarily driven by insufficient SM, making soil water content a key variable for monitoring drought conditions in agricultural settings. The SWDI, introduced by Martínez-Fernández et al. (2015), quantifies drought severity by measuring the degree of soil water deficit [43]. Because it is derived directly from SM and fundamental soil hydraulic properties, SWDI has been recognized as a reliable indicator of agricultural drought [44]. In this study, SWDI is used to evaluate agricultural drought conditions. It is calculated using the following equation:

where θ represents SM, θFC, represents field capacity and θWP represents volumetric water content at the wilting point. This formulation captures the relative deficit of soil water available to crops. Based on the SWDI values, drought severity is further classified into discrete categories (SWDI LEVEL), as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Categorization of the Soil Water Deficit Index (SWDI) for various drought levels.

2.3.2. Frameworks

In this study, we propose three distinct deep learning frameworks for forecasting agricultural drought severity, each leveraging different aspects of SM dynamics and the SWDI.

Framework A (FWA) uses SM as the prediction target, as illustrated by the red arrows in Figure 2. The model first forecasts SM values, which are then used to compute SWDI. Based on the computed SWDI, drought severity levels (SWDI LEVEL) are determined. Model performance is evaluated using correlation coefficient (R), Bias, and unbiased root mean square error (ubRMSE) across various forecast lead times, datasets, and regions. This framework provides detailed insight into soil water availability, offering a more granular understanding of drought development.

Figure 2.

The Structure of three frameworks using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models: standard LSTM, Attention-based LSTM (AttLSTM), Encoder–Decoder LSTM (EDLSTM), and Attention-based Encoder–Decoder LSTM (AEDLSTM). The red arrows in the figure indicate Framework A (FWA), which directly predicts soil moisture; the blue arrows indicate Framework B (FWB), which directly predicts the SWDI; and the green arrows indicate Framework C (FWC), which directly predicts drought severity levels.

Framework B (FWB), shown by the blue arrows in Figure 2, predicts the SWDI directly, bypassing the intermediate step of forecasting SM. The resulting SWDI values are then classified into severity levels using the same procedure as in FWA. This approach is particularly advantageous in cases where SM observations are limited or less reliable, as it focuses directly on the degree of water deficit.

Framework C (FWC), represented by the green arrows in Figure 2, directly forecasts the drought severity level (SWDI LEVEL) as a categorical output. In this framework, SWDI values—derived from SM—serve as input features, and the model is trained to classify drought conditions directly. While this method simplifies the prediction pipeline and may improve computational efficiency, it requires robust classification strategies to ensure high accuracy.

Each framework offers distinct benefits depending on data availability, prediction objectives, and operational needs. In the sections that follow, we detail the structure, implementation, and performance of each framework, highlighting their applicability under varying agricultural and climatic scenarios.

2.4. Baseline

LSTM networks are widely recognized for their effectiveness in time series forecasting [45], particularly in hydrologic applications such as SM prediction [46]. To enhance the input feature representation before temporal modeling, we introduce a lightweight Feedforward Attention Mechanism prior to the LSTM layers. This mechanism employs a fully connected layer, a Softmax activation, and a residual connection to non-linearly transform the input features and adaptively recalibrate the importance of each feature element, thereby providing a more discriminative input for subsequent sequence learning. To evaluate the robustness and generalizability of the proposed drought prediction frameworks, we implement four LSTM-based architectures built upon this enhanced input: standard LSTM, EDLSTM, AttLSTM, and AEDLSTM. Each model is applied during both training and testing phases to support a comprehensive comparison.

All experiments were run on a high-performance server with an Intel® Xeon® Gold 6330 CPU (2.00 GHz), a single NVIDIA A800 GPU (80 GB), and Linux 5.4.0.

2.4.1. Feedforward Attention Mechanism

Before feeding the input sequence into the core LSTM model, we introduce a lightweight feedforward attention [47] mechanism as a preprocessing and enhancement module for the input features. This mechanism aims to automatically learn and emphasize the feature elements that are more critical for the drought prediction task from the high-dimensional input data, thereby providing a more discriminative input representation for the subsequent time series modeling.

Its structure is shown in Figure 2 and consists of three core steps: Feature projection and nonlinear transformation: The original input sequence X = [, , …, ] is first projected into a new feature space through a fully connected layer to capture the complex nonlinear relationships among features. Attention weight generation: Subsequently, the Softmax function is applied to the transformed features Z along the feature dimension for normalization, generating an attention weight between 0 and 1 for each feature. These weights represent the relative importance of each feature element in the current prediction task. Feature weighting and residual connection: The generated attention weights A are element-wise multiplied with the original input X to obtain a weighted feature representation. Finally, a residual connection is used to add the original input and the weighted features. This approach not only retains the complete original information but also highlights the key features, effectively alleviating the vanishing gradient problem and stabilizing the training process.

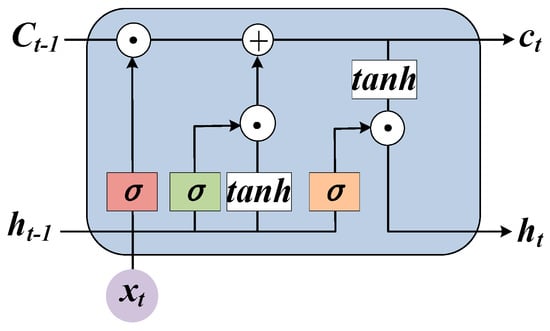

2.4.2. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

LSTM networks are a type of recurrent neural network (RNN) designed to capture both short- and long-term dependencies in sequential data. Their architecture makes them especially suitable for drought forecasting, where historical patterns in SM can inform future trend [48]. In our study, the LSTM model is configured with a hidden layer size of 128 and a dropout rate of 0.15 to prevent overfitting. It processes a rolling window of 365-day input sequences to generate 14-day forecasts of SM and related variables. Outputs from the LSTM are passed through fully connected layers to produce daily predictions over the forecast horizon. The structure of the LSTM architecture is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The architecture of the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network.

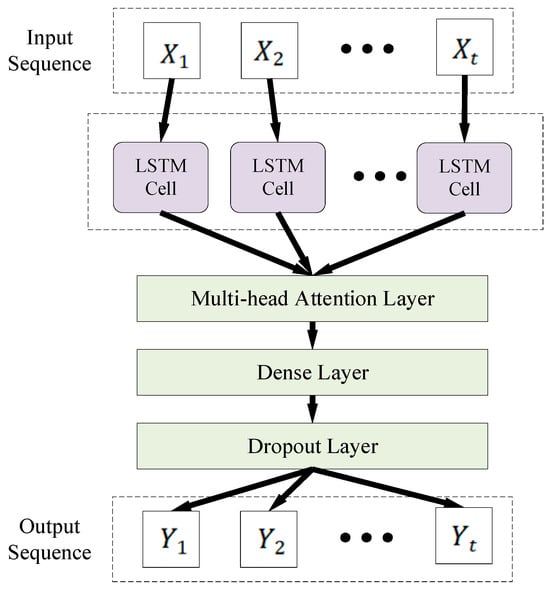

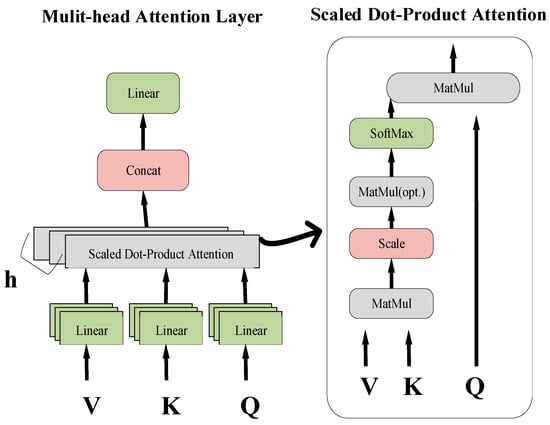

2.4.3. Attention-Based LSTM (AttLSTM)

The AttLSTM model enhances the standard LSTM by incorporating a Multi-Head Attention mechanism [49], allowing the model to dynamically assign greater importance to the most relevant time steps in the input sequence. As shown in Figure 4, the architecture comprises an LSTM layer, a Multi-Head Attention block, a fully connected layer, and a dropout layer. Attention scores are computed for each time step, enabling the model to focus on informative temporal features. The attention mechanism follows the equations below:

Figure 4.

The architecture of the Attention-based LSTM (AttLSTM) network.

Here, Q (Query), K (Key), and V (Value) represent feature vectors of the input sequence, while the projection matrices , , and and output matrix define the dimensional transformations. In this study, we set the model dimension dmodel = 512 and use h = 16 attention heads.

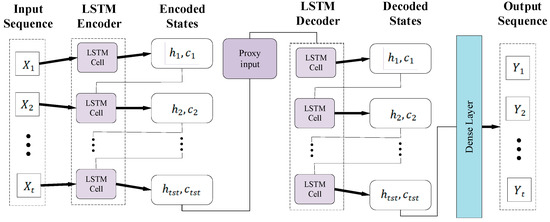

2.4.4. Encoder–Decoder LSTM (EDLSTM)

The EDLSTM model is a sequence-to-sequence architecture consisting of two LSTM networks: an encoder and a decoder [50]. As illustrated in Figure 5, the encoder processes the input sequence and condenses it into a fixed-length vector representing the temporal features of the drought-related inputs. These encoded vectors are passed as initial states to the decoder, which then generates the forecasted sequence. During inference, the decoder predicts the output sequence step-by-step using the encoder’s states and its own previous outputs.

Figure 5.

The Multi-Head Attention (on the left) consists of multiple attention layers that operate in parallel, each using Scaled Dot-Product Attention (on the right).

2.4.5. Attention-Based Encoder–Decoder LSTM (AEDLSTM)

The AEDLSTM combines the strengths of the encoder–decoder framework with a multi-head attention mechanism to improve sequence-to-sequence prediction. By incorporating attention in both the encoding and decoding stages, the model can selectively focus on the most relevant parts of the input sequence, enhancing its ability to capture complex temporal patterns.

As illustrated in Figure 6, the encoder first applies multi-head attention to identify key features across the input sequence, assigning higher weights to time steps that are more influential for the prediction task. This attention-refined sequence is then processed by the LSTM encoder to generate hidden states that summarize the input information. In the decoding phase, the AEDLSTM re-applies the attention mechanism to the encoder’s hidden states, enabling the model to focus on critical encoded features during each step of output generation. This dual attention process improves the accuracy and reliability of drought level forecasts by ensuring the model remains aligned with the most informative temporal signals throughout the prediction sequence.

Figure 6.

The architecture of the Attention-based Encoder–Decoder LSTM (AEDLSTM) network.

2.5. Model Evaluation

To comprehensively assess model performance, four evaluation metrics are employed: Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R), unbiased Root Mean Squared Error (ubRMSE), Bias, and Accuracy (ACC).

These metrics are used to evaluate the performance of each model. Pearson’s R assesses the strength and direction of the linear relationship between predicted and observed values. ubRMSE, a modified form of RMSE, eliminates systematic bias and offers a more accurate measure of prediction variability. Bias indicates whether a model tends to systematically overestimate or underestimate values, providing insight into the model’s accuracy. ACC reflects the model’s overall effectiveness in correctly classifying drought severity levels. This study calculates the ACClevel for each SWDI level as well as the overall ACCoverall. The calculation methods for each metric at the grid level are described as follows:

where denotes the observed SM at time step i, and represents the corresponding predicted value generated by the deep learning model. The symbols and indicate the mean values of the observed and predicted SM, respectively, computed across all N time steps. For classification-based evaluation, we introduce an indicator function I(), which returns 1 if the predicted drought severity level matches the observed level, and 0 otherwise. Here, L denotes the total number of drought severity categories, and Nj represents the number of samples within category j. These definitions establish a consistent framework for evaluating both continuous prediction accuracy and categorical classification performance. This dual approach ensures that the metrics reliably capture the model’s capability to reflect temporal dynamics as well as distinguish between varying levels of drought severity.

2.6. Uncertainty Analysis of Data Interpolation

Due to the revisit period and sensor limitations of SMAP-L3 data, there are inherent spatiotemporal discontinuities in densely vegetated areas (such as the northern mountainous regions) and urbanized areas (such as the core area of the Pearl River Delta). To ensure data integrity, this study employed a random forest model to interpolate the missing values. However, this interpolation process may introduce uncertainty and further affect the accuracy of drought prediction.

In the 2020 test set data, we simulated different degrees of data missing scenarios: mild missing (10–20%): simulating regular cloud cover or short-term sensor noise; moderate missing (30–50%): simulating typical situations where continuous vegetation cover or urban building clusters cause obstruction; severe missing (>50%): simulating extreme conditions, such as prolonged rainy weather or areas with strong terrain interference. For each scenario, we used the random forest model to interpolate and generate complete SMAP-L3 datasets, and retrained and evaluated the FWB-EDLSTM model, which performed optimally in medium- and long-term predictions. To quantify the propagation of interpolation uncertainty to the prediction results, we adopted the Bootstrap method, conducting 100 repeated samplings of the interpolation process for each missing scenario, generating 100 interpolated datasets. We calculated the coefficient of variation (CV) of the prediction results based on these 100 datasets to measure the stability of the predictions.

The results show that the impact of interpolation on prediction accuracy is positively correlated with the data missing rate. In the general farmland areas and coastal transition zones with a relatively low missing rate (<30%), the impact of interpolation on model accuracy (ACC) is small (decrease < 3%), and the coefficient of variation (CV) of the prediction results is less than 0.1, indicating good prediction stability. However, in the densely vegetated areas and urban areas with a high missing rate (>40%), interpolation leads to a 5–8% decrease in model ACC, a decrease in the correlation coefficient R of more than 0.08, and a significant increase in prediction uncertainty (CV > 0.15). This confirms that in areas with discontinuous data, the interpolation process is an important source of prediction error.

2.7. Sensitivity Analysis of Drought Grade Thresholds

Although the Standardized Water Deficit Index (SWDI) and its fixed thresholds have been widely used in agricultural drought monitoring, the diverse climate zones, soil types, and farming systems in Guangdong Province may require drought classification standards that are more regionally specific. To assess the robustness of the existing thresholds and explore better alternatives, this study conducted a sensitivity analysis of the thresholds:

We fine-tuned the critical thresholds for “moderate drought” and “severe drought” of SWDI within the range of [−1, −10], setting them to −4.5 and −5.5, respectively, from the original −5. Subsequently, we calculated the proportion of grid points classified as “severe drought” during the 2020 drought event under different thresholds and evaluated their impact on the 7-day prediction accuracy (ACC) within the framework of the FWB.

The results of the sensitivity analysis indicated that when the “severe drought” threshold was adjusted from −5 to −4.5, the area identified as severely drought-stricken increased significantly (+15.2%), but the prediction accuracy declined. This was because more grid points on the verge of drought were included in the “severe” category, increasing the difficulty of model prediction. Conversely, when the threshold was relaxed to −5.5, the severely drought-affected area became more concentrated, achieving the highest prediction accuracy, but at the cost of underreporting some actual drought-affected areas. This demonstrated that the original threshold of −5 was a compromise point that achieved a good balance between identification capability and prediction reliability.

2.8. Analysis of Traditional and Baseline Model

To objectively evaluate the performance of the proposed deep learning framework, this study selected representative statistical models and traditional machine learning models as baselines for comparison. All baseline models were trained and tested using the same dataset, input sequence length, and prediction target as the deep learning model to ensure the fairness of the comparison. ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average): As a classic linear time series prediction model, it is widely used in the field of hydrology and meteorology. We established an ARIMA model for each grid point, using the SWDI sequence of the past 365 days to predict the values for the next 1 day and 7 days. Support Vector Regression (SVR): As a powerful nonlinear machine learning model, it maps the data to a high-dimensional space through a kernel function to find the optimal separating hyperplane. We used the radial basis function (RBF) as the kernel function. Random Forest (RF): An ensemble learning algorithm that improves the generalization ability and robustness of the model by constructing multiple decision trees and summarizing their prediction results.

On all prediction time scales and evaluation metrics, the deep learning models consistently and significantly outperformed the traditional baseline models, as shown in Table 3. For instance, in the 1-day prediction, the best-performing AEDLSTM model had an R value of 0.84, which was 12% higher than that of the optimal baseline model (RF, R = 0.75), while the ubRMSE was reduced by 21.7%. In the more challenging 7-day prediction, the deep learning models maintained high correlation (R > 0.69) while their errors (ubRMSE) were much lower than those of the traditional models. This clearly demonstrates that LSTM and its variants, due to their inherent sequence modeling capabilities and their ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships, have an irreplaceable advantage in the drought index prediction task.

Table 3.

Performance Comparison of Different Models in the SWDI Prediction Task (Average Value of Test Set).

3. Results

This section provides a comprehensive evaluation of the predictive performance of four deep learning models—LSTM, AttLSTM, EDLSTM, and AEDLSTM—across three forecasting frameworks (FWA, FWB, and FWC). By utilizing two input datasets, ERA5-Land and SMAP-L3, we examine how each model performs under various temporal settings and data conditions. The primary focus is on assessing their effectiveness in predicting drought severity, as quantified by SWDI levels.

To ground our evaluation in a real-world scenario, we focus on a significant drought event that struck Guangdong Province in early 2020. From January 1 to January 24, the region faced an acute precipitation deficit, with rainfall averaging just 1.9 mm—94% below the historical average of 34.0 mm. By the end of January, more than 45 counties had been affected by extreme drought, with 20 counties experiencing severe conditions. To assess the effectiveness of our models, we have set the experiment period from January 10 to 24, 2020, capturing the progression of this event and the models’ ability to forecast it.

3.1. Multi-Temporal Framework Assessment

In the 1-day prediction task (Table 4), models using ERA5-Land data demonstrated significantly higher overall prediction accuracy compared to those based on SMAP-L3 data. Among the ERA5-Land models, the FWB-LSTM achieved the highest overall accuracy (ACCoverall) of 0.805. In contrast, the three SMAP-L3-based frameworks generally showed weaker performance, likely due to the lower spatial and temporal resolution of the SMAP-L3 SM product, as well as intermittent data gaps and inherent uncertainties in remote sensing retrievals. These factors likely hindered the models’ ability to capture short-term variability.

Table 4.

Performance of Different Models in FWA Across Various Drought Levels on a 1-Day Timescale Using the ERA5-Land and SMAP Datasets. Bold values indicate the best results for each drought level under both driving datasets.

Notably, for severe drought prediction, both the ERA5-Land-based FWA-LSTM and FWA-AEDLSTM performed exceptionally well, achieving an accuracy of 0.878. The strength of the FWA framework lies in its direct prediction of soil moisture (SM), which minimizes cumulative errors from intermediate variable transformations, thus ensuring high predictive stability under extreme drought conditions. This highlights the critical importance of combining a well-designed framework with high-quality input data to accurately identify drought events across various time scales.

When the prediction lead time was extended to 3 days (Table 5), the overall accuracy of models based on ERA5-Land data showed a moderate decline, with ACCavg decreasing by more than 21%. This reduction may be attributed to the accumulation of uncertainties in future meteorological and SM variations as the lead time increases, thereby affecting overall predictive accuracy. Despite the notable decline, the FWB-AttLSTM still achieved a relatively high accuracy of 0.718 in extreme drought prediction, benefiting from the attention mechanism’s ability to dynamically assign weights to different time steps, thereby enhancing sensitivity to extreme events. When the prediction lead time was extended to 3 days (Table 4), the overall accuracy of models based on ERA5-Land data showed a moderate decline, with ACCavg decreasing by more than 21%. This reduction may be attributed to the accumulation of uncertainties in future meteorological and SM variations as the lead time increases, thereby affecting overall predictive accuracy. Despite the notable decline, the FWB-AttLSTM still achieved a relatively high accuracy of 0.718 in extreme drought prediction, benefiting from the attention mechanism’s ability to dynamically assign weights to different time steps, thereby enhancing sensitivity to extreme events. In contrast, the three SMAP-L3-based frameworks experienced only a slight drop in accuracy for the 3-day prediction compared with the 1-day forecast. This may be due to SMAP-L3’s inherent capability, as a remotely sensed retrieval product, to stably capture large-scale SM variations, making short-term extensions in lead time have relatively limited impact on overall accuracy. Among them, the FWB-EDLSTM performed particularly well under severe drought conditions, achieving a prediction accuracy of 0.860. This advantage likely stems from Framework B’s direct use of the drought index as the prediction target, combined with EDLSTM’s strengths in modeling both short- and long-term dependencies and suppressing error accumulation, enabling it to maintain strong recognition of extreme drought events even when using low-resolution remote sensing data.

Table 5.

Different Models’ Accuracy in FWA Across Various Drought Levels on a 3-Day Timescale Using the ERA5-Land and SMAP-L3 Datasets. Bold values indicate the best results for each drought level under both driving datasets.

To conduct a more comprehensive evaluation of the performance of each forecasting framework over a longer prediction period, we have separately listed the 7-day and 14-day prediction results in Appendix A Table A1 and Table A2. Overall, in medium and long-term predictions, the models based on SMAP-L3 data generally outperformed those based on ERA5-Land data. This conclusion is consistent with the trend observed in the short-term prediction analysis, further indicating that the SMAP-L3 data has a lower dependence on short-term meteorological fluctuations and is less susceptible to the accumulation of errors over longer prediction periods, thus demonstrating better stability and applicability in medium and long-term drought predictions. In some FWC frameworks, certain models exhibited notably strong performance at specific drought severity levels. This may be attributed to the FWC framework’s direct use of drought categories as the prediction target, enabling the models to focus on critical features near classification boundaries and thereby enhancing predictive specificity and robustness under different drought scenarios. Notably, in the 14-day lead prediction, the SMAP-L3-based FWB-EDLSTM still achieved an accuracy of 0.825. This advantage is likely due to two factors: first, Framework B directly targets the drought index, reducing error amplification caused by intermediate variable conversion; second, EDLSTM’s strengths in modeling long-sequence dependencies and extracting features across temporal scales allow it to preserve critical drought signals even under ultra-long lead conditions, effectively avoiding the cumulative error issues often encountered by conventional LSTM models in long-term forecasting. These results clearly demonstrate that the FWB-EDLSTM has significant potential for agricultural drought early warning over medium- to long-term horizons, particularly in regions lacking high-frequency meteorological or reanalysis data, where it can provide a longer decision-making window for agricultural management and disaster prevention.

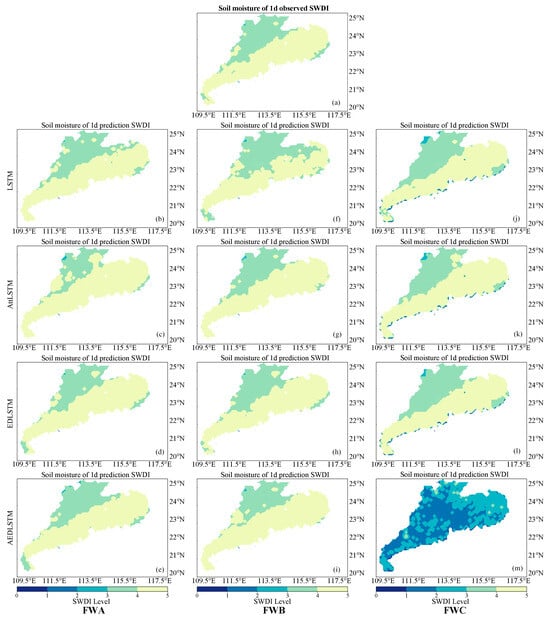

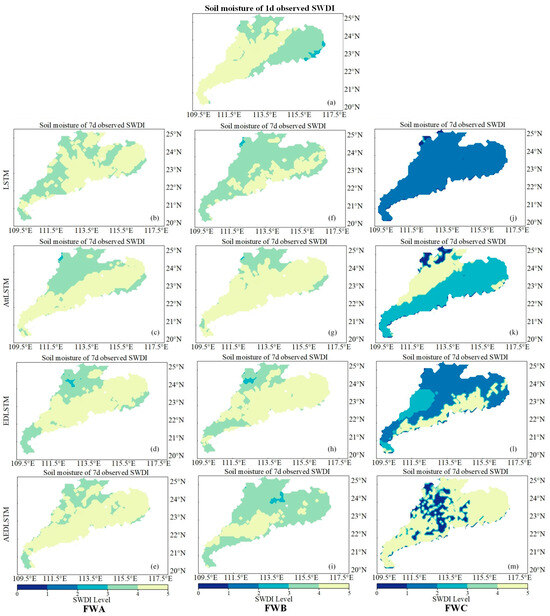

3.2. Spatial Pattern Comparison Across Different Forecasting Frameworks

Figure 7 and Figure 8 provide spatial comparisons between observed and predicted drought patterns across Guangdong Province using the ERA5-Land dataset. Three predictive frameworks (FWA, FWB, FWC) and four deep learning models (LSTM, AttLSTM, EDLSTM, AEDLSTM) were evaluated for both 1-day and 7-day forecasts. Drought severity is classified into five levels: 1 (No drought), 2 (Mild), 3 (Moderate), 4 (Severe), and 5 (Extreme). Figure 7a presents the 1-day observed baseline, while Figure 7b–e, f–i, and j–m display the predictions from the FWA, FWB, and FWC frameworks, respectively. These comparisons allow for a visual assessment of model performance across different drought intensities.

Figure 7.

Spatial Distribution of the Prediction Accuracy for Each Model with a 1-Day Lead Time in FWA, FWB, and FWC Using the ERA5_Land Dataset. Subfigure (a) shows the observational baseline, while subfigures (b–e), (f–i), and (j–m) present the prediction results of the four models under the FWA, FWB, and FWC forecasting frameworks, respectively.

Figure 8.

Spatial Distribution of the Prediction Performance for Each Model with a 7-Day Lead Time in FWA, FWB, and FWC Using the ERA5_Land Dataset. Subfigure (a) shows the observational baseline, while subfigures (b–e), (f–i), and (j–m) present the prediction results of the four models under the FWA, FWB, and FWC forecasting frameworks, respectively.

The observed 1-day drought pattern (Figure 7a) reveals clear spatial variability. Northern Guangdong (NGD) and the western Pearl River Delta (PRD), including cities such as Shaoguan, Qingyuan, Zhaoqing, and Yunfu, experienced widespread severe drought (SWDI = 4). In contrast, Eastern (EGD) and Western Guangdong (WGD), as well as the eastern PRD, were affected by extreme drought (SWDI = 5). Model predictions for the 1-day forecast capture these patterns with varying success. Along the PRD coast, most models accurately represent extreme drought areas (SWDI = 5), aligning closely with observations and indicating strong signal recognition. However, model performance diverges in specific regions. In the Chaozhou-Shantou area (EGD), where observations indicate severe drought (SWDI = 4), the FWA-EDLSTM, FWA-AEDLSTM, and FWB-EDLSTM models show the closest agreement. Other models tend to overestimate drought severity. In the Zhanjiang region (WGD), FWA-based models fail to identify localized extreme drought, while FWB-EDLSTM captures the spatial gradient from severe to extreme drought more accurately. In inland areas, particularly around Heyuan and Meizhou in NGD, observations show widespread extreme drought (SWDI = 5). Baseline LSTM models consistently underestimate severity in this region. Attention-based models, especially AttLSTM and EDLSTM, provide more accurate spatial representation. Among them, FWB-EDLSTM offers the highest spatial accuracy, effectively reproducing the observed drought intensity.

Overall, most models successfully identify the general distribution of severe and extreme drought, though regional accuracy varies. Notably, the FWC-AEDLSTM model underperforms in spatial consistency. These discrepancies highlight the sensitivity of each framework to regional characteristics and drought intensity levels.

Figure 8 shifts the focus to 7-day forecasts. Observations (Figure 8a) show a clear east–west divide in drought conditions. Extreme drought (SWDI = 5) dominates the western PRD, WGD, and northern regions (e.g., Yunfu, Qingyuan, Shaoguan, Heyuan). Severe drought (SWDI = 4) appears across EGD, eastern PRD, and eastern NGD. Moderate drought (SWDI = 3) is mainly found along the EGD coast, suggesting a gradient from inland to coast. Compared to 1-day forecasts, 7-day predictions show greater spatial variability. Most models underestimate drought intensity in western Guangdong. An exception is FWB-AttLSTM (Figure 8g), which accurately captures extreme drought in WGD, Yunfu, and the western PRD, and severe drought in western NGD. However, this model tends to overestimate severity in eastern regions, misclassifying SWDI = 4 areas as SWDI = 5. FWB-AEDLSTM (Figure 8i), while underestimating drought in the west, performs well in reconstructing severe drought in EGD. A consistent weakness across all models is the inability to detect the moderate drought transition zone along the EGD coast, where overestimation by 1–2 severity levels suggest inadequate representation of coastal microclimatic effects.

The spatial analysis reveals clear, scale-dependent differences in model performance. In 1-day forecasts, coastal–inland contrasts are particularly pronounced. While models generally agree on detecting extreme drought in the coastal areas of the Pearl River Delta (PRD), they diverge in capturing the coastal drought in Zhanjiang. Among them, FWB-EDLSTM consistently delivers the most accurate results by effectively integrating multi-scale spatial features. For 7-day forecasts, the drought pattern shifts to an east–west divide. FWB-AttLSTM performs exceptionally well in identifying extreme drought areas in the west, aligning closely with the underlying karst topography. However, predictions for coastal transition zones, particularly in the eastern Guangdong region (EGD), remain problematic for most models, with the exception of FWB-AEDLSTM. This highlights the ongoing challenges in modeling land–sea interaction processes and capturing the complex dynamics of coastal areas.

3.3. Evaluation of Predictive Performance Across Different Forecasting Frameworks

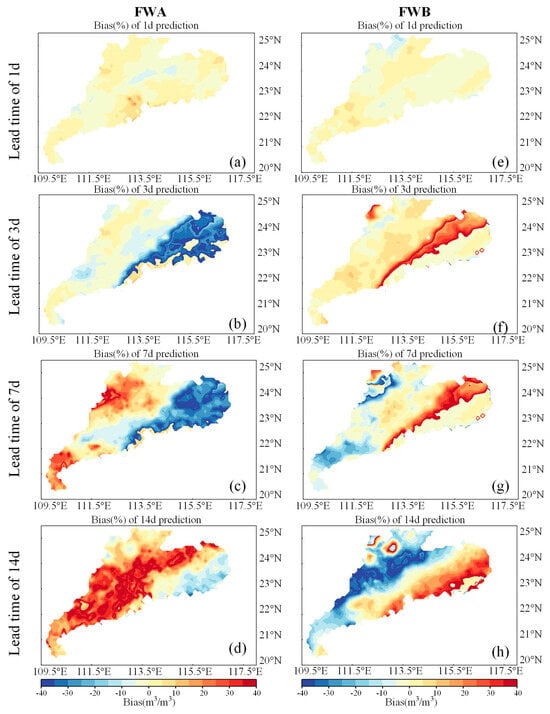

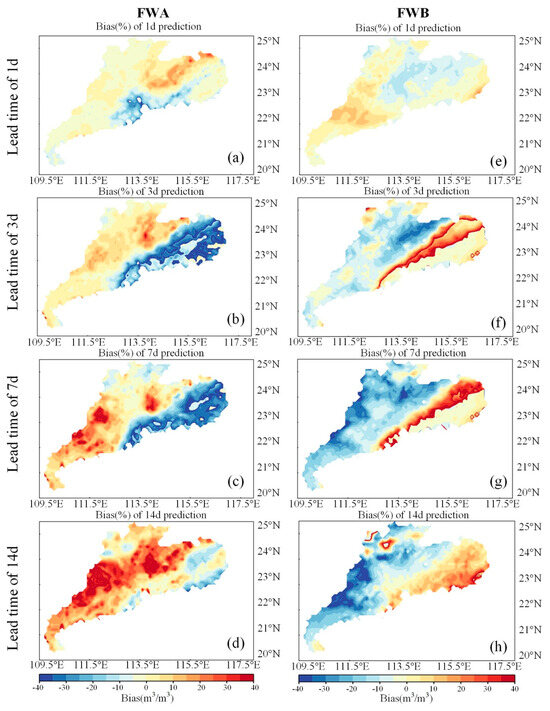

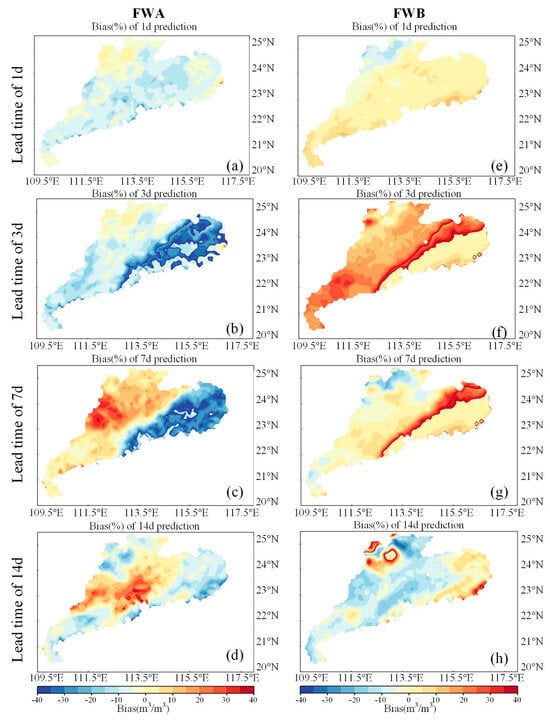

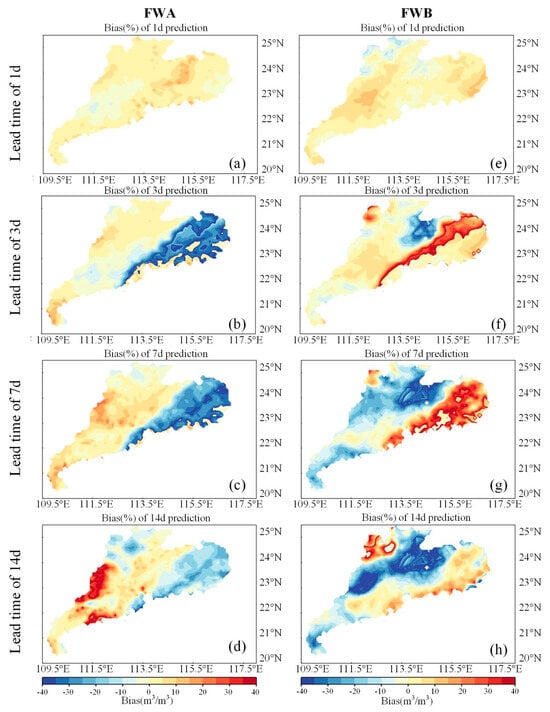

Based on the excellent predictive performance of the FWA and FWB frameworks, we selected Guangdong Province as the research object and utilized the ERA5-Land dataset to conduct a systematic evaluation of four deep learning models: LSTM, AttLSTM, EDLSTM, and AEDLSTM. Figure 9, Figure A1, Figure A2 and Figure A3 illustrate the spatial distribution of prediction bias under both frameworks. For short-term forecasts (1–3 days), Bias values were generally low, with EDLSTM under the FWB framework showing the best performance, indicating high accuracy at shorter lead times. As the forecast horizon extended to 7 and 14 days, spatial biases increased. Under FWA, models tended to overpredict in western and northern Guangdong, while FWB models underpredicted more often in the same regions. Overall, FWB demonstrated smaller and more spatially balanced biases, underscoring its advantage in medium- to long-term predictions.

Figure 9.

The Bias of the EDLSTM model in FWA and FWB for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d based on the ERA5_Land dataset. The first column shows the EDLSTM model’s predictions at different time scales in FWA (a–d), while the second column displays its predictions in FWB (e–h). Each row corresponds to a different lead time: 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d.

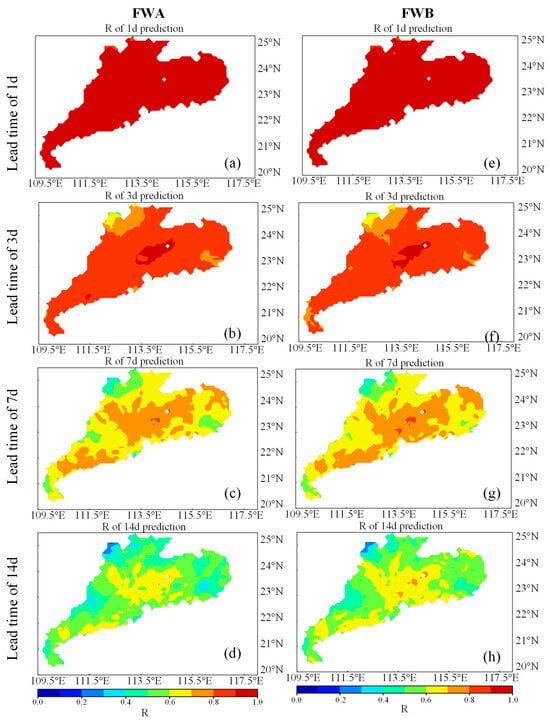

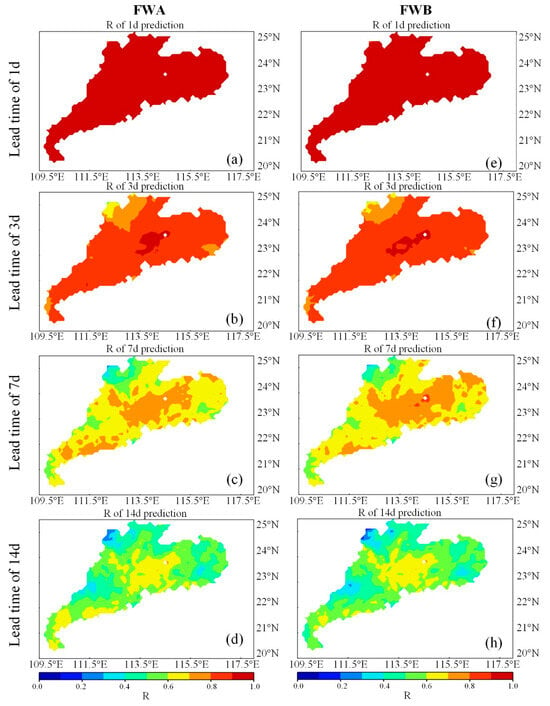

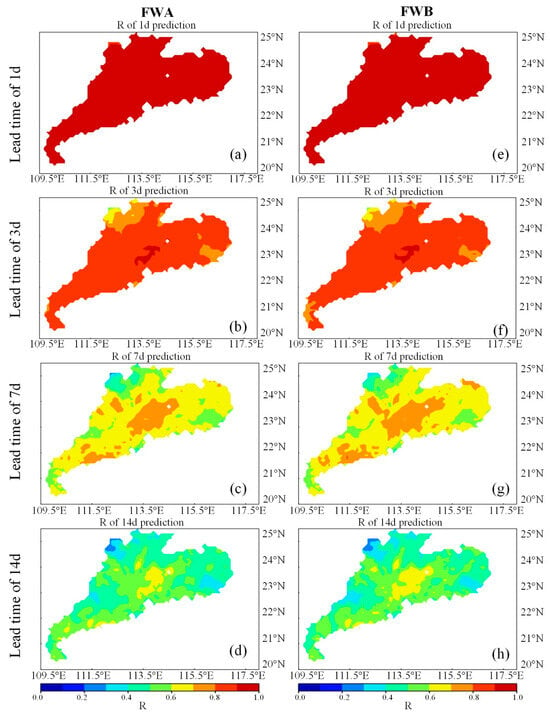

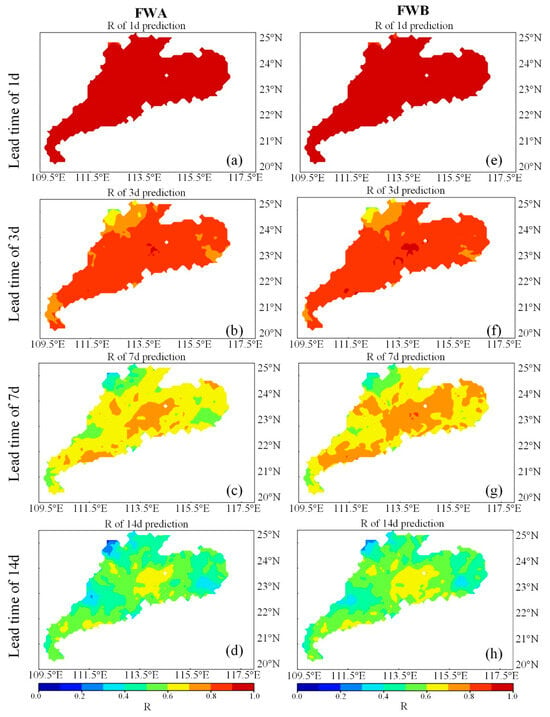

To evaluate the temporal and spatial generalization ability of the models, we examined the distribution of correlation coefficients (Figure 10, Figure A4, Figure A5 and Figure A6). Across all time horizons, AttLSTM consistently achieved the highest correlation values. For 1-day forecasts, R values commonly ranged from 0.7 to 1.0, indicating strong predictive skill. However, model performance declined with increasing lead time, with R dropping below 0.5 in some regions at 14 days. Despite this, FWB maintained higher overall correlation values than FWA, suggesting it better preserves relevant features for extended forecasts.

Figure 10.

The R values of the AttLSTM model in FWA (a–d)and FWB (e–h) for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d based on the ERA5_Land dataset.

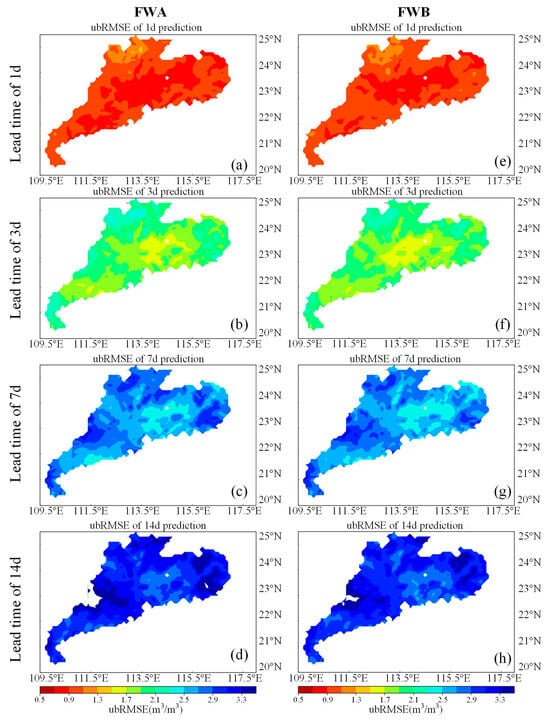

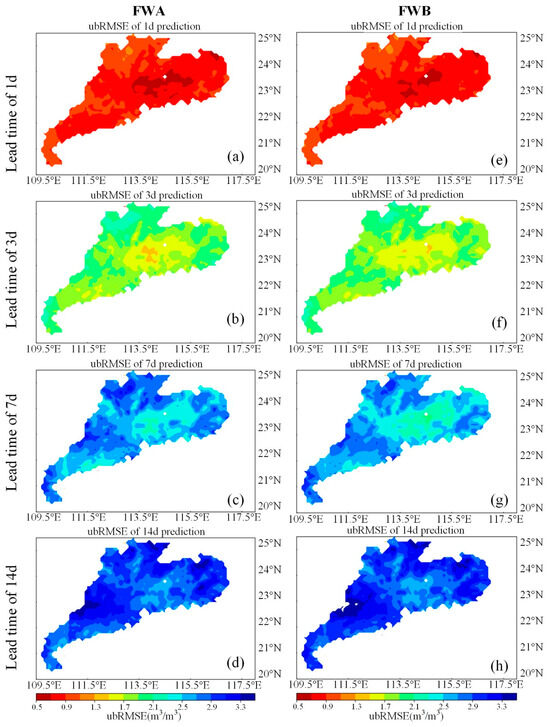

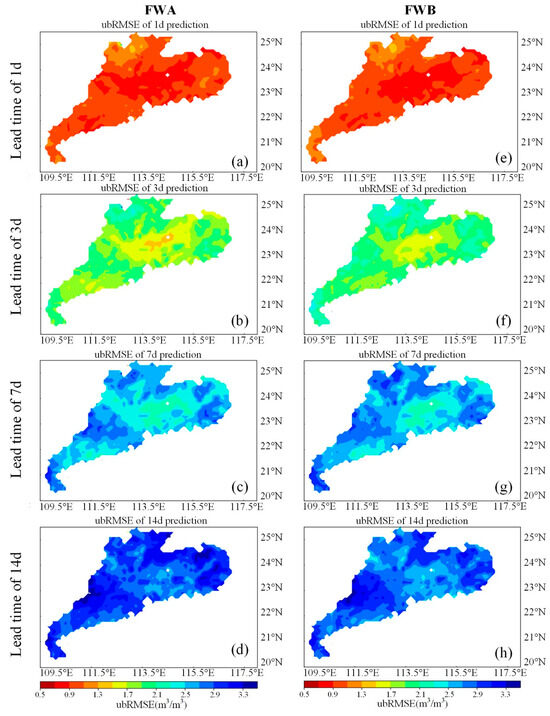

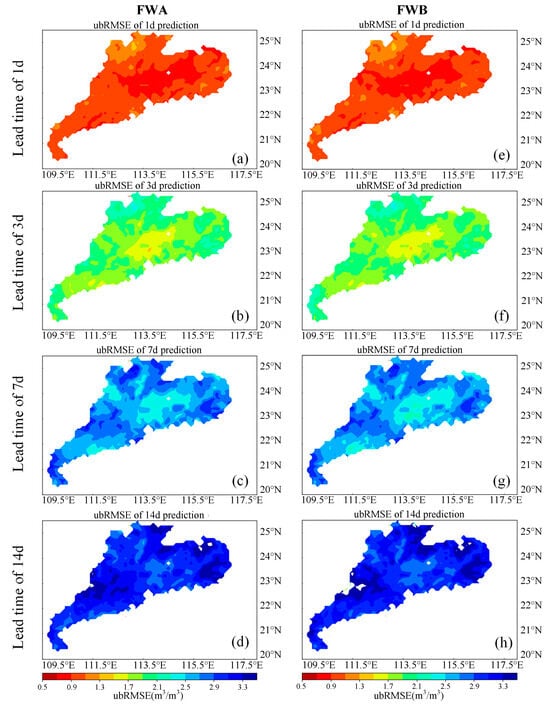

The spatial distribution pattern of ubRMSE (Figure 11 and attached Figure A7, Figure A8 and Figure A9) is consistent with the deviation and correlation trends. In short-term predictions, the ubRMSE values of the FWB framework are lower, especially in key areas of Guangdong Province, such as Shantou and Qingyuan in the north, Guangzhou and Foshan in the Pearl River Delta, and coastal cities like Jieyang and Shantou in the east. For longer time scales, FWA is only superior to FWB in some local coastal areas (such as Yangjiang and Maoming). It is worth noting that in all time periods and locations, the AEDLSTM model under the FWB framework always performs better than the similar models under the FWA framework (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

The ubRMSE of the AEDLSTM model in FWA (a–d) and FWB (e–h) for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d based on the ERA5_Land dataset.

In summary, the combined results from Bias, correlation, and ubRMSE analyses consistently highlight the superior performance of the FWB framework. While FWA offers limited advantages for simpler models like LSTM or EDLSTM in specific regions, FWB proves more effective for complex models—particularly AttLSTM and AEDLSTM—especially at longer forecast horizons.

4. Discussions

This study presents the first comprehensive comparison of three deep learning drought prediction frameworks—FWA (SM-driven), FWB (SWDI-driven), and FWC (drought classification-driven)—combined with four model architectures (LSTM, AttLSTM, EDLSTM, AEDLSTM) across Guangdong Province. By integrating ERA5-Land reanalysis data with SMAP-L3 satellite observations, we evaluate how data sources, model designs, and prediction frameworks jointly influence drought forecasting accuracy across varying time scales and regional environments.

4.1. Impact of Forecast Horizon

Forecast horizon strongly influences model performance. ERA5-Land-driven models, benefiting from high temporal resolution, excel in short-term (1–3 day) forecasts, making them ideal for rapid drought response, such as emergency irrigation scheduling with the FWA-LSTM model. However, accuracy declines markedly as forecast length increases, due to error accumulation. In contrast, SMAP-L3-driven models maintain greater stability over medium to long terms (7–14 days). Notably, the FWB-EDLSTM model experiences only a modest (~5.5%) accuracy drop, underscoring its suitability for ongoing drought monitoring and water resource management. For forecasts beyond 14 days, the ERA5-Land-based FWC-AEDLSTM model effectively identifies extreme drought zones, supporting proactive disaster preparedness efforts.

4.2. Model Response to Drought Severity

Model performance varies considerably with drought intensity. The FWB framework performs reliably under moderate drought but struggles to capture nonlinear SM dynamics during extreme drought. Conversely, the classification-based FWC-AEDLSTM excels in identifying severe drought events, offering valuable early warnings—especially for compound cold–dry risks during sensitive periods like fruit tree dormancy. The simpler FWA-LSTM model remains robust under prolonged drought stress, demonstrating strong generalization, particularly during critical crop stages such as rice heading.

These results suggest that agricultural drought monitoring should employ flexible prediction frameworks tailored to crop growth phases. For instance, the FWB framework is recommended during rice’s critical growth periods for sustained drought tracking, while the FWC framework suits perennial crops during dormancy for capturing compound extreme events.

4.3. Impact of Spatial Heterogeneity on Prediction Performanc

Prediction accuracy varies across Guangdong’s diverse regions. In the Pearl River Delta, characterized by flat terrain and stable climate, all models perform well, supporting the use of model-guided precision agriculture and automated irrigation. However, in coastal Zhanjiang and northern mountainous areas, complex topography and variable climate cause sparse data features and reduced model accuracy. For these challenging regions, tailored strategies are needed: incorporating typhoon path forecasts to refine short-term coastal drought predictions and expanding ground-based SM networks in mountainous areas to complement remote sensing, thereby enhancing model reliability.

By integrating spatial and temporal analyses, this study highlights the essential roles of multi-source data fusion and model architecture in improving agricultural drought prediction. The findings provide both a scientific foundation for optimizing predictive frameworks and practical guidance for drought risk management and regional agricultural meteorological services in Guangdong Province.

4.4. Attribution Analysis of Prediction Deviations and Model Limitations

The spatial assessment results of this study (Section 3.2) revealed systematic deviations in the model’s predictions within specific regions. To explore the underlying causes, we conducted an in-depth attribution analysis from three levels: data, environment, and model architecture, aiming to provide directions for future model improvements.

Data uncertainty-induced deviations: The overestimation of drought severity observed in the core urban agglomeration of the Pearl River Delta was mainly attributed to the systematic errors in the ERA5-Land reanalysis data itself. These highly urbanized areas have extremely complex underlying surfaces, and the reanalysis data, due to its simplified physical model, is unable to accurately simulate the energy and water exchange within the urban canopy, often overestimating soil moisture. Our prediction model learned this biased “truth” and inherited this systematic error in the predictions, resulting in overcorrection, that is, overestimation of the severity of drought.

Underrepresented environmental characteristics-induced deviations: The underestimation of drought severity in the northern mountainous areas of Guangdong can be attributed to the absence or insufficient representation of two key environmental characteristics. Firstly, the extensive karst landform in this region leads to shallow soil layers and extremely poor water-holding capacity. However, the spatial resolution of the soil texture data used by the model is insufficient to capture the highly heterogeneous “soil funnel” effect, thus overestimating the available water in the soil. Secondly, the model does not consider human irrigation activities. During drought periods, the concentrated irrigation in river valley agricultural areas significantly increased regional soil moisture, while the model is oblivious to this, thus its predictions reflect an unirrigated natural state, which appears overly optimistic compared to the actual situation.

Model architecture limitations: The performance differences of different model architectures in complex regions also reflect their inherent limitations. This study found that models equipped with attention mechanisms (such as AttLSTM and AEDLSTM) exhibited smaller deviations in coastal and mountainous areas. This indicates that the Attention mechanism, by dynamically focusing on the key information in the input sequence (such as specific drought precursors), can partially compensate for the inaccuracy of input data, demonstrating stronger environmental adaptability and robustness compared to the standard LSTM that treats all historical information equally.

Future improvements in the prediction framework should focus on the following aspects: Integrating higher-resolution soil attributes and land use data; Introducing human activities (such as irrigation) as model features or post-processing constraints; Prioritizing the use of model architectures with dynamic feature selection capabilities (such as attention mechanisms), to better cope with the heterogeneity of the geographical environment and the uncertainty of input data.

5. Conclusions

Agricultural drought substantially reduces soil water content, directly threatening crop growth and food security. Therefore, accurately representing drought severity is crucial for optimizing irrigation scheduling, strengthening regional water resource management, and formulating agricultural disaster-mitigation measures. This study proposes three drought forecasting frameworks—FWA (predicting soil moisture), FWB (predicting the Soil Water Deficit Index, SWDI), and FWC (directly outputting SWDI drought categories)—and compares the predictive performance of four LSTM-based architectures (LSTM, EDLSTM, AttLSTM, AEDLSTM) driven by SMAP-L3 and ERA5-Land data. Results indicate that all frameworks perform well across mild to extreme drought conditions; in particular, FWA and FWB deliver especially reliable predictions, validating the effectiveness of our approach for accurate and timely agricultural drought forecasting.

In order to convert the predictive performance of the model into practical value, we took the main grain crop in Guangdong Province, rice, as an example to simulate the potential consequences of using different models for irrigation decision-making guidance during the drought event in January 2020. The analysis shows that the optimal model proposed in this study (FWB-AEDLSTM) with its higher prediction accuracy can avoid approximately 7 million yuan of potential yield loss and generate about 1.7 million yuan of water-saving benefits, with a total economic gain expected to reach 8.7 million yuan. Moreover, the higher prediction accuracy also brings far-reaching social benefits: it can provide a longer warning period for water resource management departments to optimize regional water resource allocation and alleviate water shortage problems.

Future work will focus on incorporating additional meteorological and soil variables to increase the models’ sensitivity to different drought types, and on exploring dynamic adjustment methods that integrate climate model outputs to improve long-term forecast accuracy [47,48,49]. These improvements are expected to further enhance the precision and practical value of drought predictions, providing more effective decision-support tools for agricultural drought management in Guangdong and similar regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L.; methodology, J.Z., Z.Z., and S.Y.; software, J.W.; validation, J.Z. and X.Z.; formal analysis, S.Y. and J.Z.; investigation, X.Z. and J.Z.; resources, J.W. and Q.L.; data curation, J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z., Z.Z., X.Z. and S.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.W. and Q.L.; visualization, X.Z. and J.Z.; supervision, Q.L.; project administration, X.C.; funding acquisition, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Development Plan Project under grant 20230101370JC, the Scientific Research Project of the Education Department of Jilin Province under grant JJKH20261802KJ, the Natural Science Foundation of Changchun Normal University under grant CSJJ2024008ZK and the Jilin Province Education Science “14th Five-Year Plan” Project under grant BRJ25073.

Data Availability Statement

I have shared the link to my data at https://doi.org/10.11888/Atmos.tpdc.300294.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the colleagues and collaborators who provided valuable feedback and support throughout the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Performance of Different Models in FWA Across Various Drought Levels on a 7-Day Timescale Using the ERA5-Land and SMAP-L3 Datasets. Bold values indicate the best results for each drought level under both driving datasets.

Table A1.

Performance of Different Models in FWA Across Various Drought Levels on a 7-Day Timescale Using the ERA5-Land and SMAP-L3 Datasets. Bold values indicate the best results for each drought level under both driving datasets.

| Data | Framework | Model | No Drought | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Extreme | ACCoverall |

| ERA5-Land | FWA | LSTM | 0.005 | 0.526 | 0.410 | 0.558 | 0.209 | 0.467 |

| AttLSTM | 0.018 | 0.536 | 0.432 | 0.539 | 0.128 | 0.463 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.014 | 0.563 | 0.419 | 0.521 | 0.187 | 0.466 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.013 | 0.556 | 0.383 | 0.544 | 0.231 | 0.466 | ||

| FWB | LSTM | 0.011 | 0.527 | 0.406 | 0.600 | 0.116 | 0.474 | |

| AttLSTM | 0.021 | 0.551 | 0.407 | 0.527 | 0.347 | 0.474 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.018 | 0.534 | 0.423 | 0.547 | 0.178 | 0.467 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.003 | 0.544 | 0.396 | 0.559 | 0.139 | 0.463 | ||

| FWC | LSTM | 0.210 | 0.132 | 0.163 | 0.204 | 0.120 | 0.167 | |

| AttLSTM | 0.225 | 0.079 | 0.153 | 0.198 | 0.449 | 0.174 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.092 | 0.143 | 0.231 | 0.228 | 0.135 | 0.194 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.125 | 0.084 | 0.105 | 0.655 | 0.001 | 0.285 | ||

| SMAP-L3 | FWA | LSTM | 0.035 | 0.098 | 0.297 | 0.313 | 0.599 | 0.322 |

| AttLSTM | 0.118 | 0.048 | 0.300 | 0.400 | 0.553 | 0.365 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.007 | 0.068 | 0.260 | 0.604 | 0.518 | 0.472 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.007 | 0.135 | 0.263 | 0.596 | 0.471 | 0.468 | ||

| FWB | LSTM | 0.039 | 0.097 | 0.371 | 0.496 | 0.553 | 0.438 | |

| AttLSTM | 0.036 | 0.076 | 0.435 | 0.791 | 0.039 | 0.557 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.010 | 0.137 | 0.409 | 0.835 | 0.051 | 0.584 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.019 | 0.062 | 0.372 | 0.828 | 0.117 | 0.575 | ||

| FWC | LSTM | 0.104 | 0.230 | 0.319 | 0.208 | 0.099 | 0.217 | |

| AttLSTM | 0.000 | 0.624 | 0.540 | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.163 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.000 | 0.538 | 0.040 | 0.122 | 0.004 | 0.124 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Table A2.

Performance of Different Models in FWA Across Various Drought Levels on a 14-Day Timescale Using the ERA5-Land and SMAP-L3 Datasets. Bold values indicate the best results for each drought level under both driving datasets.

Table A2.

Performance of Different Models in FWA Across Various Drought Levels on a 14-Day Timescale Using the ERA5-Land and SMAP-L3 Datasets. Bold values indicate the best results for each drought level under both driving datasets.

| Data | Framework | Model | No Drought | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Extreme | ACCoverall |

| ERA5-Land | FWA | LSTM | 0.022 | 0.456 | 0.442 | 0.481 | 0.045 | 0.417 |

| AttLSTM | 0.017 | 0.406 | 0.465 | 0.483 | 0.092 | 0.413 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.018 | 0.467 | 0.389 | 0.445 | 0.100 | 0.398 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.009 | 0.438 | 0.401 | 0.476 | 0.187 | 0.411 | ||

| FWB | LSTM | 0.019 | 0.496 | 0.430 | 0.459 | 0.043 | 0.417 | |

| AttLSTM | 0.011 | 0.410 | 0.480 | 0.532 | 0.057 | 0.433 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.018 | 0.473 | 0.384 | 0.444 | 0.156 | 0.402 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.009 | 0.489 | 0.424 | 0.464 | 0.069 | 0.418 | ||

| FWC | LSTM | 0.218 | 0.126 | 0.122 | 0.148 | 0.068 | 0.131 | |

| AttLSTM | 0.145 | 0.145 | 0.262 | 0.107 | 0.091 | 0.157 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.163 | 0.193 | 0.171 | 0.127 | 0.139 | 0.159 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.053 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.214 | 0.719 | 0.133 | ||

| SMAP-L3 | FWA | LSTM | 0.000 | 0.090 | 0.274 | 0.306 | 0.589 | 0.310 |

| AttLSTM | 0.085 | 0.015 | 0.255 | 0.446 | 0.493 | 0.372 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.002 | 0.041 | 0.253 | 0.655 | 0.395 | 0.483 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.003 | 0.088 | 0.264 | 0.637 | 0.342 | 0.472 | ||

| FWB | LSTM | 0.003 | 0.064 | 0.308 | 0.437 | 0.553 | 0.387 | |

| AttLSTM | 0.015 | 0.059 | 0.260 | 0.805 | 0.122 | 0.541 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.004 | 0.110 | 0.386 | 0.805 | 0.038 | 0.559 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.333 | 0.825 | 0.070 | 0.557 | ||

| FWC | LSTM | 0.367 | 0.110 | 0.318 | 0.048 | 0.044 | 0.110 | |

| AttLSTM | 0.000 | 0.652 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.037 | 0.067 | ||

| EDLSTM | 0.000 | 0.242 | 0.114 | 0.077 | 0.129 | 0.103 | ||

| AEDLSTM | 0.000 | 0.233 | 0.510 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.120 |

Figure A1.

The Bias of the LSTM model in FWA and FWB for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d based on the ERA5_Land dataset. The first column presents the LSTM model’s predictions at different time scales in FWA (a–d), while the second column shows its predictions in FWB (e–h). Each row corresponds to a specific lead time: 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d.

Figure A2.

The Bias of the AttLSTM model in FWA and FWB for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d based on the ERA5_Land dataset. The first column displays the AttLSTM model’s predictions at various time scales in FWA (a–d), while the second column shows its predictions in FWB (e–h). Each row corresponds to a specific lead time: 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d.

Figure A3.

The Bias of the AEDLSTM model in FWA and FWB for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d based on the ERA5_Land dataset. The first column shows the AEDLSTM model’s predictions at various time scales in FWA (a–d), while the second column presents its predictions in FWB (e–h). Each row corresponds to a different lead time: 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d.

Figure A4.

The R values of the LSTM model in FWA and FWB for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d based on the ERA5_Land dataset. The first column presents the LSTM model’s predictions at various time scales in FWA (a–d), while the second column shows its predictions in FWB (e–h). Each row corresponds to a specific lead time: 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d.

Figure A5.

The R values of the EDLSTM model in FWA and FWB for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d based on the ERA5_Land dataset. The first column shows the EDLSTM model’s predictions at different time scales in FWA (a–d), while the second column displays its predictions in FWB (e–h). Each row represents a specific lead time: 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d.

Figure A6.

The R values of the AEDLSTM model in FWA and FWB for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d using the ERA5_Land dataset. The first column presents the AEDLSTM model’s predictions across various time scales in FWA (a–d), while the second column shows its predictions in FWB (e–h). Each row corresponds to a specific lead time: 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d.

Figure A7.

The ubRMSE values of the LSTM model in FWA and FWB for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d based on the ERA5_Land dataset. The first column displays the LSTM model’s predictions at different time scales in FWA (a–d), while the second column shows its predictions in FWB (e–h). Each row corresponds to a specific lead time: 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d.

Figure A8.

The ubRMSE values of the AttLSTM model in FWA and FWB for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d based on the ERA5_Land dataset. The first column shows the AttLSTM model’s predictions at various time scales in FWA (a–d), while the second column presents its predictions in FWB (e–h). Each row corresponds to a different lead time: 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d.

Figure A9.

The ubRMSE values of the EDLSTM model in FWA and FWB for lead times of 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d based on the ERA5_Land dataset. The first column displays the EDLSTM model’s predictions at different time scales in FWA (a–d), while the second column shows its predictions in FWB (e–h). Each row corresponds to a specific lead time: 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 14 d.

References

- Wilhite, D.A. Droughts: A Global Assesment; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, X.; Pan, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y. Agricultural drought monitoring: Progress, challenges, and prospects. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 750–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Vu, T.; Veettil, A.V.; Entekhabi, D. Drought monitoring with soil moisture active passive (SMAP) measurements. J. Hydrol. 2017, 552, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Huang, S.; Huang, Q.; Leng, G.; Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; Fang, W.; Li, P.; Zheng, X. Assessing agricultural drought risk and its dynamic evolution characteristics. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 231, 106003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Sun, X.; Sun, H.; Chen, L.; Lu, M.; Xue, J.; Ban, X.; Yan, B.; Tuo, Y.; Qin, H.; et al. Mechanisms of meteorological drought propagation to agricultural drought in China: Insights from causality chain. npj Nat. Hazards 2025, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Singh, V.P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 2010, 391, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Shangguan, W.; Liu, J.; Dong, W.; Wu, D. Assessing meteorological and agricultural drought characteristics and drought propagation in Guangdong, China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 51, 101611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Li, K. Spatial characteristics of drought hazard in Guangdong Province. J. Lake Sci. 2012, 24, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, W.; Zhang, R.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, F.; Li, J.; Liu, W. Assessment of agricultural drought based on reanalysis soil moisture in Southern China. Land 2022, 11, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Wiese, D.N.; Reager, J.T.; Beaudoing, H.K.; Landerer, F.W.; Lo, M.-H. Emerging trends in global freshwater availability. Nature 2018, 557, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolten, J.D.; Crow, W.T.; Zhan, X.; Jackson, T.J.; Reynolds, C.A. Evaluating the utility of remotely sensed soil moisture retrievals for operational agricultural drought monitoring. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2009, 3, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyantash, J.; Dracup, J.A. The quantification of drought: An evaluation of drought indices. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2002, 83, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, W.; Wagner, W.; Albergel, C.; Albrecht, F.; Balsamo, G.; Brocca, L.; Chung, D.; Ertl, M.; Forkel, M.; Gruber, A.; et al. ESA CCI Soil Moisture for improved Earth system understanding. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 203, 185–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, E.G.; Entekhabi, D. Passive microwave remote sensing of soil moisture. J. Hydrol. 1996, 184, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Jia, G. Monitoring meteorological drought in China using remote sensing drought index. Nat. Hazards 2013, 67, 127–144. [Google Scholar]

- AghaKouchak, A.; Farahmand, A.; Melton, F.S.; Teixeira, J.; Anderson, M.C.; Wardlow, B.D.; Hain, C.R. Remote sensing of drought: Progress, challenges and opportunities. Rev. Geophys. 2015, 53, 452–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, F.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Mao, T.; Xiong, Z.; Shangguan, W. Assessment of agricultural drought using soil water deficit index based on ERA5-land soil moisture data in four southern provinces of China. Agriculture 2021, 11, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Dai, X.; Ehsan, M.A.; Deksissa, T. Development of a drought prediction system based on long short-term memory networks (LSTM). In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Networks–ISNN 2020: 17th International Symposium on Neural Networks, ISNN 2020, Cairo, Egypt, 4–6 December 2020; Proceedings 17. Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Z.; Xu, L.; Chen, N. Combining graph neural network and convolutional LSTM network for multistep soil moisture spatiotemporal prediction. J. Hydrol. 2025, 651, 132572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization; ICLR: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, J.; Im, J.; Carbone, G.J. Monitoring agricultural drought for arid and humid regions using multi-sensor remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 2875–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A multi-scalar drought index sensitive to global warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. JMLR 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate; NIPS: Noida, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Q.; Zhao, M.; Running, S.W. Improvements to a MODIS global terrestrial evapotranspiration algorithm. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 115, 1781–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, J.; Wood, E.F.; Roderick, M.L. Little change in global drought over the past 60 years. Nature 2012, 491, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J. Deep learning in neural networks: An overview. Neural Netw. 2015, 61, 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Dai, Y.; Wei, Z.; Shangguan, W.; Wei, N.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, X.-X. Enhancing deep learning soil moisture forecasting models by integrating physics-based models. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 41, 1326–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhu, J. Enhancing soil moisture forecasting accuracy with REDF-LSTM: Integrating residual en-decoding and feature attention mechanisms. Water 2024, 16, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fernández, J.; González-Zamora, A.; Sánchez, N.; Gumuzzio, A. A soil water based index as a suitable agricultural drought indicator. J. Hydrol. 2015, 522, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigkas, D.; Vangelis, H.; Tsakiris, G. DrinC: A software for drought analysis based on drought indices. Earth Sci. Inform. 2015, 8, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. In Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Applied Climatology, Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–22 January 1993; pp. 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, K.; Chai, H.; Ye, Y.; Liu, W. Characterizing extreme drought and wetness in Guangdong, China using global navigation satellite system and precipitation data. Satell. Navig. 2024, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fan, J.; Luo, R. Drought risk analysis and zoning in Guangdong Province based on AHP and GIS. China Flood Drought Manag. 2023, 33, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Y. Cause Analysis of Drought in Autumn, Winter and Spring in Guangdong from 2020 to 2021. Meteorol. Mon. 2022, 48, 783–793. [Google Scholar]

- Trenberth, K.E.; Dai, A.; Van Der Schrier, G.; Jones, P.D.; Barichivich, J.; Briffa, K.R.; Sheffield, J. Global warming and changes in drought. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, Z.; Yan, S.; Peng, J. Do ERA5 and ERA5-land precipitation estimates outperform satellite-based precipitation products? A comprehensive comparison between state-of-the-art model-based and satellite-based precipitation products over mainland China. J. Hydrol. 2022, 605, 127353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entekhabi, D.; Njoku, E.G.; O’Neill, P.E.; Kellogg, K.H.; Crow, W.T.; Edelstein, W.N.; Entin, J.K.; Goodman, S.D.; Jackson, T.J.; Johnson, J.; et al. The Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) mission. Proc. IEEE 2010, 98, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, S.; Liu, J. Integrating remote sensing and machine learning for agricultural drought prediction: A review. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 253, 106939. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzon, J.E.; Pak, E.W.; Tucker, C.J.; Bhatt, U.S.; Frost, G.V.; Macander, M.J. Global Vegetation Greenness (NDVI) from AVHRR GIMMS-3G+, 1981–2022; ORNL DAAC: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Fernández, J.; González-Zamora, A.; Sánchez, N.; Gumuzzio, A.; Herrero-Jiménez, C. Satellite soil moisture for agricultural drought monitoring: Assessment of the SMOS derived Soil Water Deficit Index. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 177, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablos, M.; Martínez-Fernández, J.; Sánchez, N.; González-Zamora, Á. Temporal and spatial comparison of agricultural drought indices from moderate resolution satellite soil moisture data over Northwest Spain. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Jin, X.; Zhang, C.; Shangguan, W.; Wei, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, P.; Dai, Y. Improving global soil moisture prediction based on Meta-Learning model leveraging Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Catena 2025, 250, 108743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9, December 2017; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Shangguan, W.; Wei, Z.; Yuan, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Liu, P.; et al. LandBench 1.0: A benchmark dataset and evaluation metrics for data-driven land surface variables prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 243, 122917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Lin, R.; Zhang, R.; Wu, G. Attention-based LSTM (AttLSTM) neural network for seismic response modeling of bridges. Comput. Struct. 2023, 275, 106915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anshuman, A.; Eldho, T.I. A parallel workflow framework using encoder-decoder LSTMs for uncertainty quantification in contaminant source identification in groundwater. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).