A Century of Data: Machine Learning Approaches to Drought Prediction and Trend Analysis in Arid Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

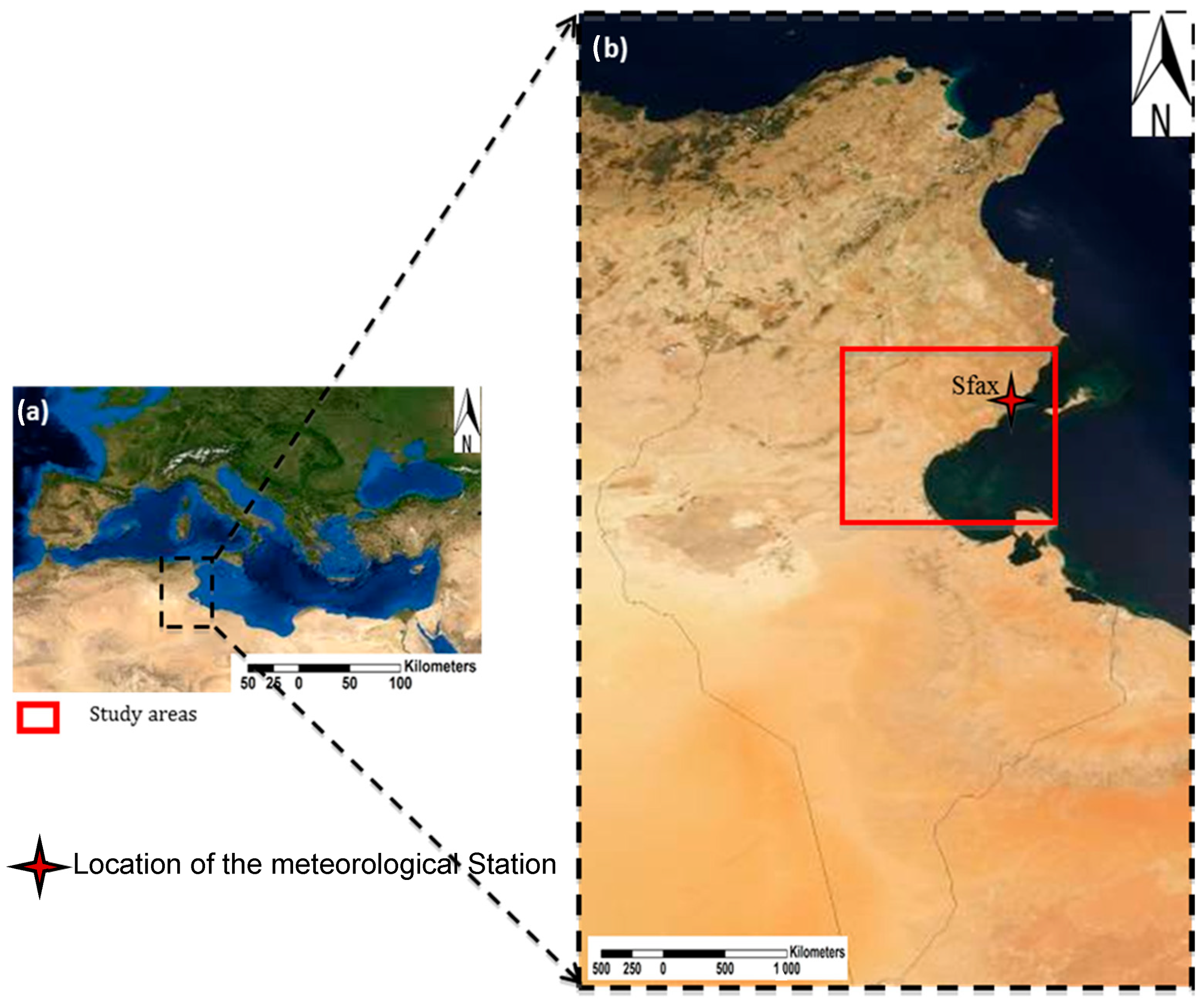

2. Study Region

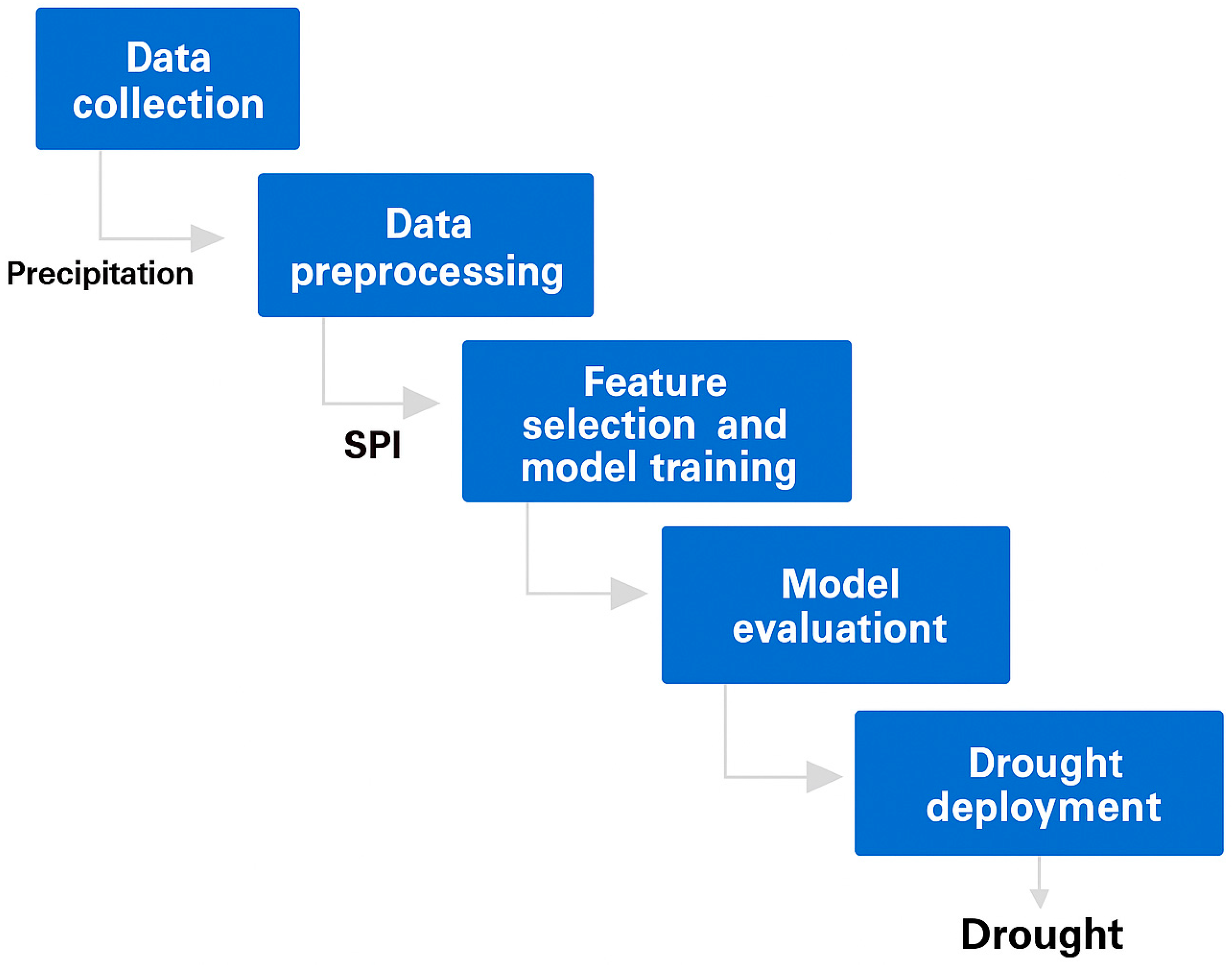

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

- Precipitation data:

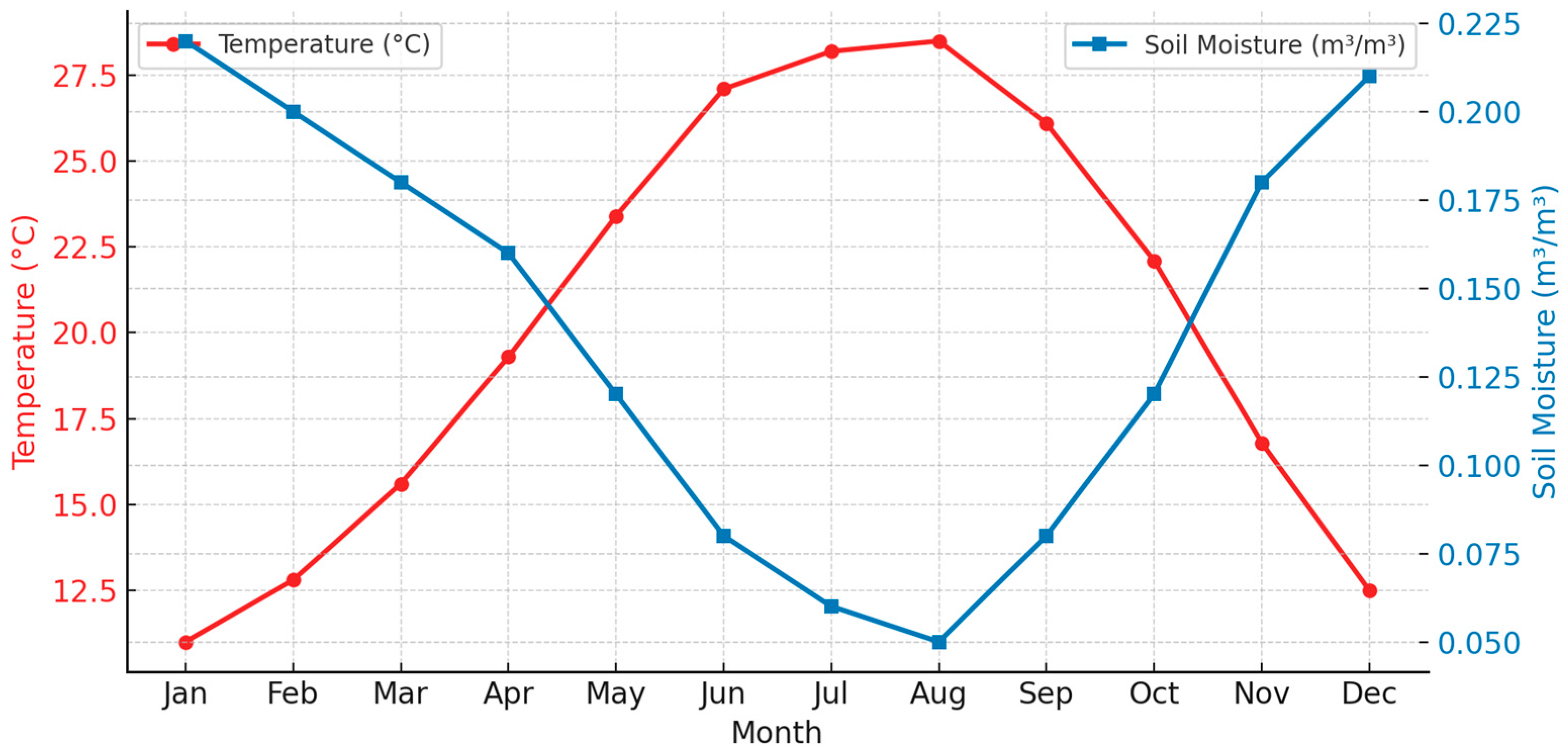

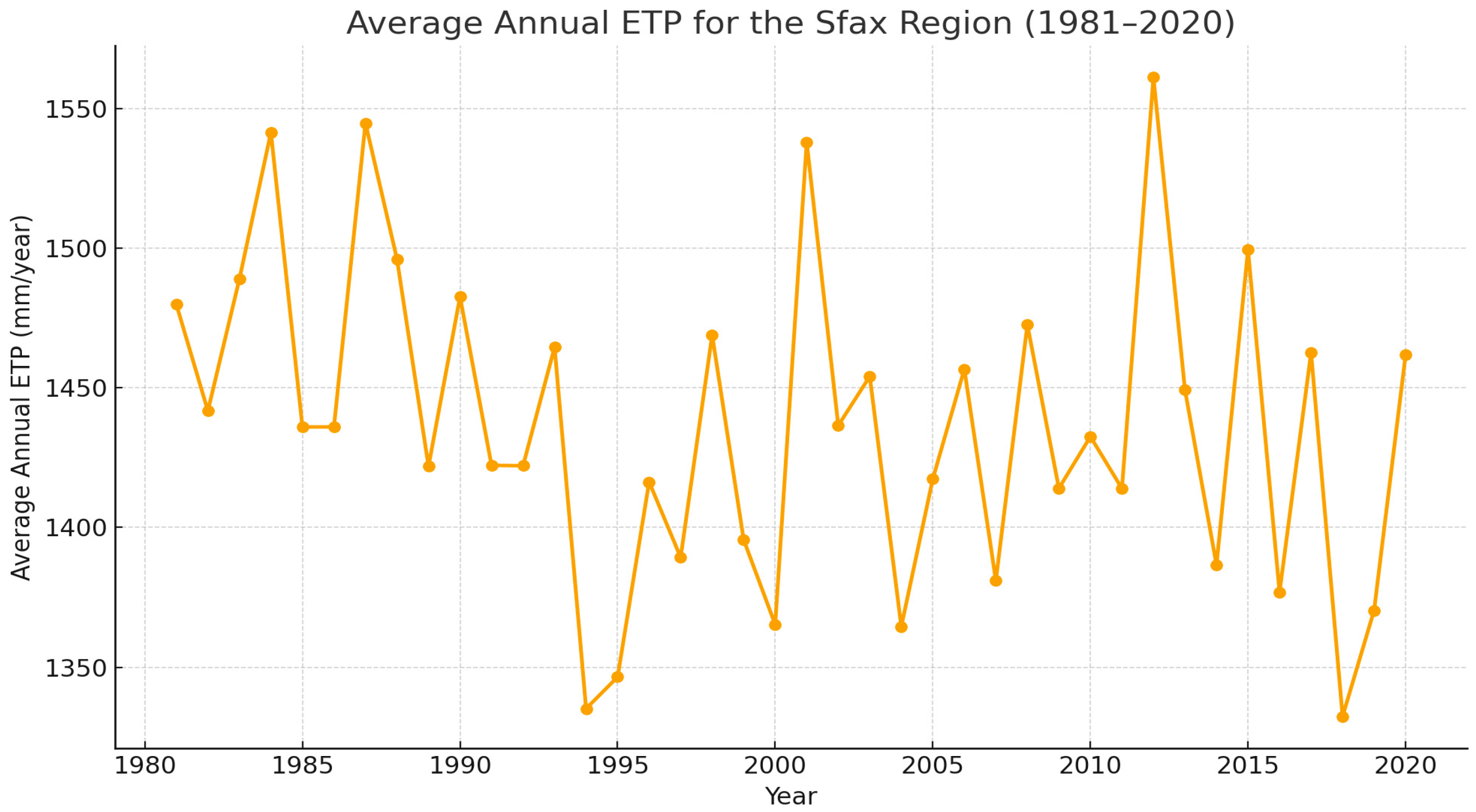

- Temperature and Evapotranspiration:

- Soil Moisture:

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Data Collection

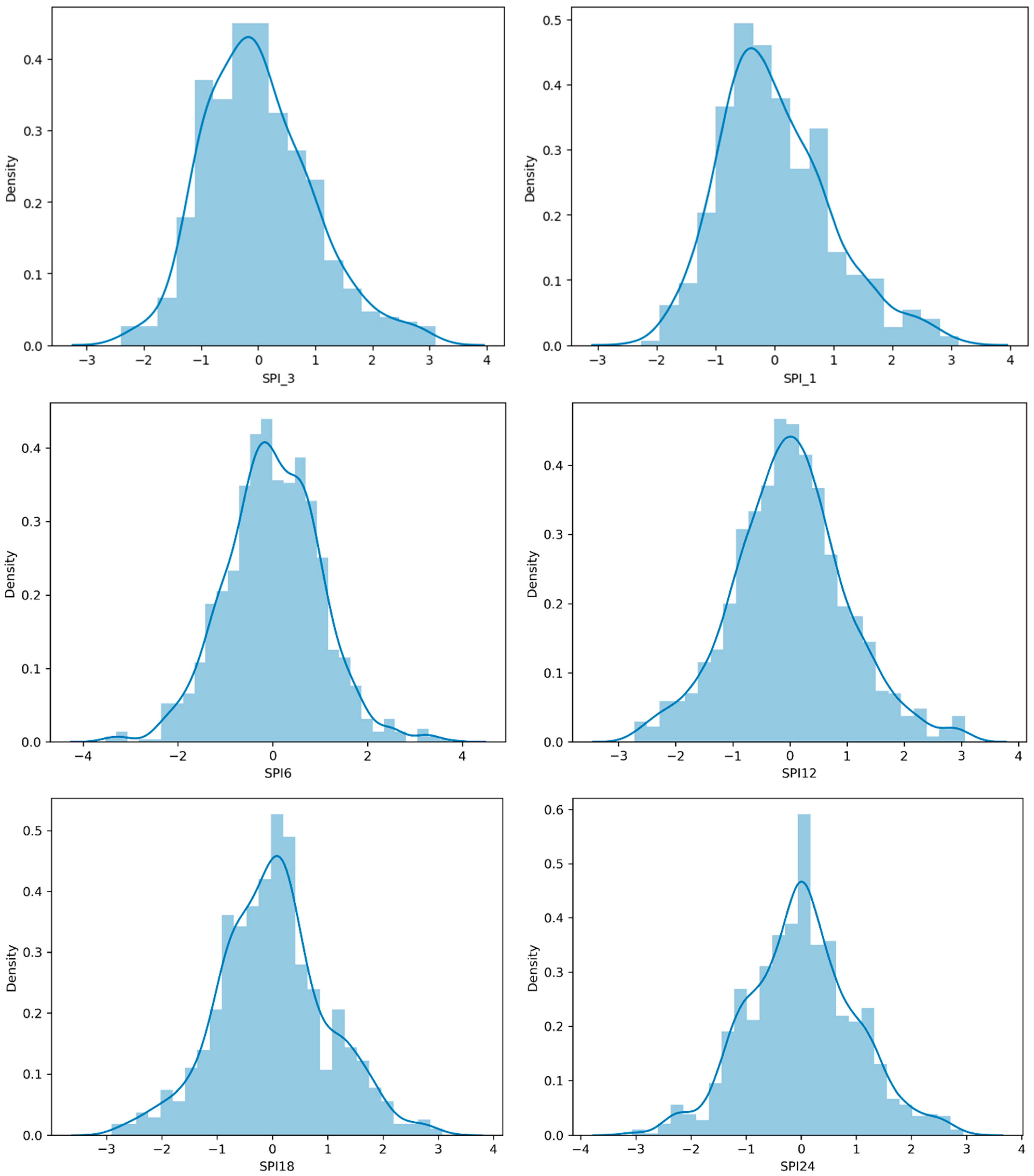

3.2.2. Calculation of the SPI

3.2.3. Machine Learning Framework for Reliable Drought Forecasting

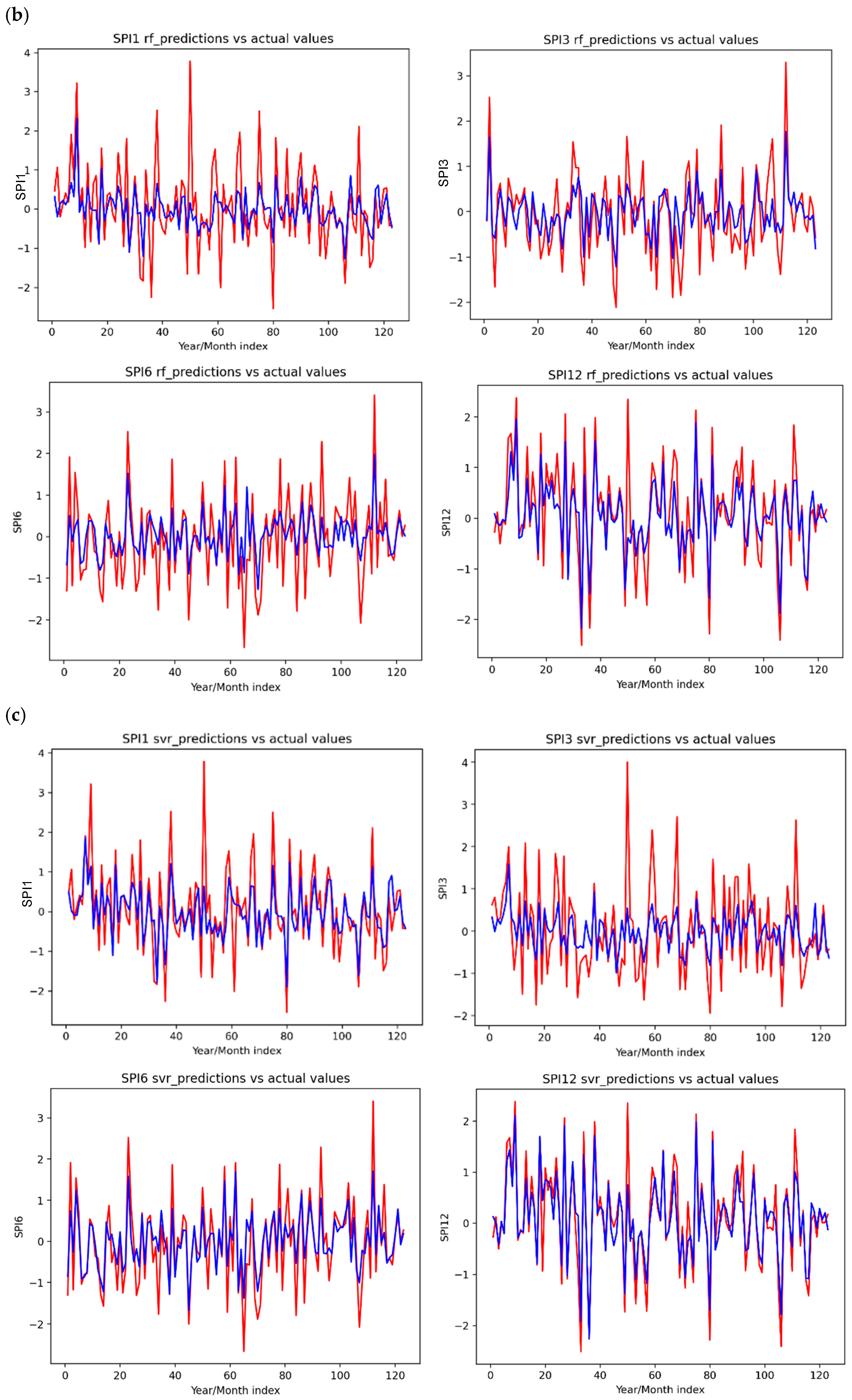

- Random Forest (RF):

- Draw a random sample of *k* data points from the training set.

- Grow a decision tree for that sample.

- Specify the desired number of trees (n-trees).

- Repeat the sampling and tree-building process.

- Make the final prediction by aggregating the outputs of all the trees.

- Support Vector Regression (SVR):

- SVR captures non-linear relationships using kernel functions. Common choices include linear, polynomial, sigmoid, and radial basis function (RBF) kernels. The RBF kernel was selected here for its ability to model complex non-linear dependencies, its computational efficiency, and its generally strong performance across diverse datasets.

- SVR performance depends on three key parameters: ε (tolerance margin), C (regularization/penalty), and γ (kernel parameter controlling the influence of data points), which are discussed in detail below [41].

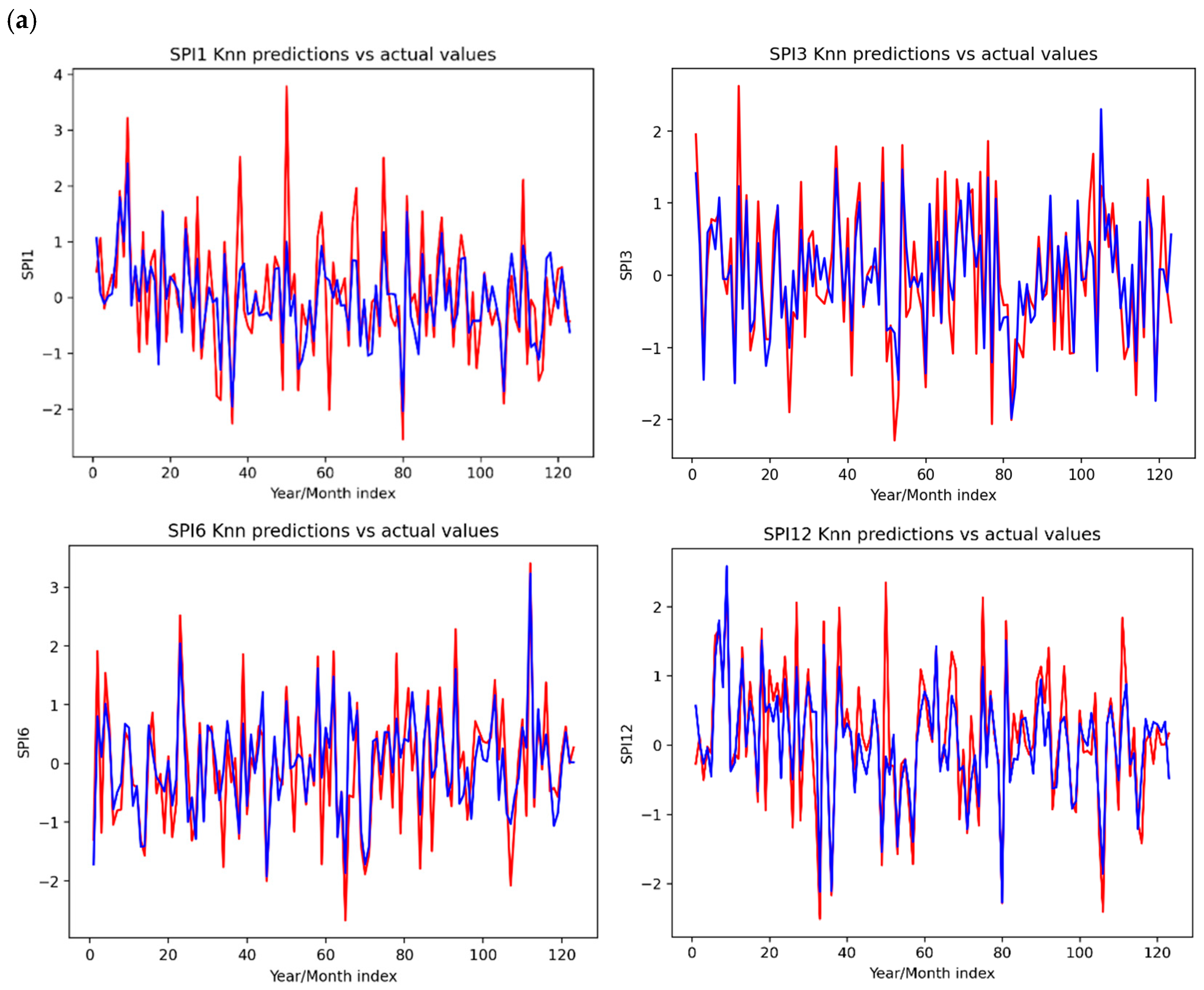

- The k-Nearest Neighbor: kNN

- A K value that is too large can cause the model to become overly generalized, allowing larger classes to dominate and bias the results.

- A K value that is too small increases the model’s sensitivity to noise and outliers, as it fails to leverage the smoothing effect of a larger sample.

3.2.4. Model Performance Evaluation

4. Results

4.1. Temporal Evolution of SPI in Different Timescales

4.2. Mann–Kendall Test

4.3. Performance Metrics

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SPI | Standardized Precipitation Index |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| kNN | k-Nearest Neighbor |

References

- Carter, R.; Parker, A. Climate change, population trends, and groundwater in Africa. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2009, 54, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A. Drought under global warming: A review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2010, 1, 45–56, Erratum in Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2012, 3, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to timescales. In Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Applied Climatology, Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–22 January 1993; pp. 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, M.; Svoboda, M.; Wall, N.; Widhalm, M. The Lincoln declaration on drought indices: Universal meteorological drought index recommended. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 92, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.N.; Li, Q.F.; Nguyen, L.B.; Xu, G.H. Comparing Machine-Learning Models for Drought Forecasting in Vietnam’s Cai River Basin. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 27, 2633–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.B.; Li, Q.F.; Ngoc, T.A.; Hiramatsu, K. Adaptive Neuro–Fuzzy Inference System for Drought Forecasting in the Cai River Basin in Vietnam. J. Fac. Agric. Kyushu Univ. 2015, 60, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zuo, D.; Song, J. Improving prediction accuracy of river discharge time series using a Wavelet-NAR artificial neural network. J. Hydroinform. 2012, 14, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbot, J.; Marohasy, J. Application of artificial neural networks to rainfall forecasting in Queensland, Australia. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2012, 29, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbot, J.; Marohasy, J. Input selection and optimization for monthly rainfall forecasting in Queensland, Australia, using artificial neural networks. Atmos. Res. 2014, 138, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.; Kaya, Y.; Uyar, M.; Yıldırım, S. Application of extreme learning machine for estimating solar radiation from satellite data. Int. J. Energy Res. 2014, 38, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraju, R.S. Artificial neural networks in hydrology. II: Hydrologic applications. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2000, 5, 124–137. [Google Scholar]

- Gacu, J.G.; Monjardin, C.E.F.; Mangulabnan, R.G.T.; Pugat, G.C.E.; Solmerin, J.G. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Surface Water Management: A Comprehensive Review of Methods, Applications, and Challenges. Water 2025, 17, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, W.U.A.; Ni, J.; Ke, C.; Xie, Y. BloomSense: Integrating Automated Buoy Systems and AI to Monitor and Predict Harmful Algal Blooms. Water 2025, 17, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masinde, M. Artificial neural networks models for predicting effective drought index: Factoring effects of rainfall variability. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2013, 19, 1139–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastos, P.; Paliatsos, A.; Koukouletsos, K.; Larissi, I.; Moustris, K. Artificial neural networks modeling for forecasting the maximum daily total precipitation at Athens, Greece. Atmos. Res. 2014, 144, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, N.; Shrivastava, N.A.; Panigrahi, B.; Mohanty, U. Development of an artificial neural network based multi-model ensemble to estimate the northeast monsoon rainfall over south peninsular India: An application of extreme learning machine. Clim. Dyn. 2013, 43, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.K.; Pandey, R.P.; Jain, M.K.; Byun, H.R. Comparison of drought indices for appraisal of drought characteristics in the Ken River Basin. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2015, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondol, M.A.H.; Ara, I.; Das, S.C. Meteorological drought index mapping in Bangladesh using Standardized Precipitation Index during 1981–2010. Adv. Meteorol. 2017, 2017, 4642060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallear, J.W.; Valadares Galdos, M.; Zeri, M.; Hartley, A. Evaluation of machine learning approaches for large-scale agricultural drought forecasts to improve monitoring and preparedness in Brazil. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 25, 1521–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyaneshwar, A.; Mishra, A.; Chadha, U.; Raj Vincent, P.M.D.; Rajinikanth, V.; Pattukandan Ganapathy, G.; Srinivasan, K. A Contemporary Review on Deep Learning Models for Drought Prediction. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandgude, N.; Singh, T.P.; Nandgude, S.; Tiwari, M. Drought Prediction: A Comprehensive Review of Different Drought Prediction Models and Adopted Technologies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, I.D.; Grayson, R.B.; Ladson, A.R. Digital Terrain Modelling: A Review of Hydrological, Geomorphological, and Biological Applications. Hydrol. Process. 1991, 5, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yao, Y.; Feng, Z.; Ou, M. Hydrological drought prediction and its influencing features analysis based on a machine learning model. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 25, 4299–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yin, J.; Slater, L.; Kang, S.; Yang, Y.; Liu, P.; Guo, J.; Gu, X.; Zhang, X.; Volchak, A. Machine-learning-constrained projection of bivariate hydrological drought magnitudes and socioeconomic risks over China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 3305–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, A.; Chakraborty, J. Analysis of machine learning algorithms in drought prediction. Comput. Res. Dev. 2023, 23, 52–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. DroughtSet: Understanding Drought Through Spatial-Temporal Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.15075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.; Habaieb, H. Agro-climatic characterization of the Sfax region based on long-term observations from the Ezzitouna station. Tunis. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 34, 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Lazcano, A. Walking back the data quantity assumption to improve time series forecasting. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.R.; Chopra, P.; Dadhwal, V.K. Analyzing spatial patterns of meteorological drought using standardized precipitation index. Meteorol. Appl. 2007, 14, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRoberts, D.B.; Nielsen-Gammon, J.W. The use of a high-resolution standardized precipitation index for drought monitoring and assessment. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2012, 51, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, M.; Liu, X. Evaluation of Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite precipitation products for drought monitoring over the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.F.; de Sentous, P.J.G.M.; Blain, G.C. Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) calculation using the incomplete gamma distribution function: Monthly rainfall fitting, gamma-distribution parameters and transformation to a standard normal variable. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 30, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, T.B. Drought monitoring with multiple time scales. In Proceedings of the 9th Conference on Applied Climatology, Dallas, TX, USA, 15–20 January 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Bagging Predictors. Mach. Learn. 1996, 24, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacanli, U.; Firat, M.; Dikbas, F. Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System for drought forecasting. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2009, 23, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2018; ISBN 978-0987507112. [Google Scholar]

- Deo, R.C.; Şahin, M. Application of the extreme learning machine algorithm for the prediction of monthly Effective Drought Index in eastern Australia. Atmos. Res. 2015, 153, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achite, M.; Elshaboury, N.; Jehanzaib, M.; Vishwakarma, D.K.; Pham, Q.B.; Anh, D.T.; Abdelkader, E.M.; Elbeltagi, A. Performance of Machine Learning Techniques for Meteorological Drought Forecasting in the Wadi Mina Basin, Algeria. Water 2023, 15, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V.N. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dibike, Y.B.; Coulibaly, P.; Anctil, F. Comparison of Support Vector Machines and Neural Networks for the Prediction of Water Levels in the Mackenzie River. J. Hydrol. 2001, 253, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Smola, A.J.; Schölkopf, B. A Tutorial on Support Vector Regression. Stat. Comput. 2004, 14, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukas, A.; Vasiliades, L. Probabilistic analysis of drought spatiotemporal characteristics in Thessaly region, Greece. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2004, 4, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M.; Hart, P.E. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakowitz, S. Nearest-neighbor methods for time series, with applications to rainfall/runoff prediction. J. Time Ser. Anal. 1987, 8, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M. Nearest-neighbor methods for nonparametric rainfall-runoff modeling. Water Resour. Res. 1987, 23, 1300–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, U.; Sharma, A. A nearest neighbor bootstrap for resampling hydrologic time series. Water Resour. Res. 1996, 32, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.L.; Tan, K.C.; Chua, V.P.; Chan, N.W. Evaluation of TRMM Product for Monitoring Drought in the Kelantan River Basin, Malaysia. Water 2017, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabaei, S.; Sharafati, A.; Yaseen, Z.M.; Shahid, S. Copula based assessment of meteorological drought characteristics: Regional investigation of Iran. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 276, 107611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, J.M.; Silva, A.R.; Rodrigues, M.A. A machine learning model for drought tracking and forecasting using satellite-based precipitation data. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 86, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Cui, N.; Gong, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L. Evaluation of random forests and generalized regression neural networks for daily reference evapotranspiration modelling. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 227, 117834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Abdelmalek, M.; Nouiri, I. Study of trends and mapping of drought events in Tunisia and their impacts on agricultural production. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 139311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouaziz, M.; Medhioub, E.; Csaplovisc, E. A machine learning model for drought tracking and forecasting using remote precipitation data and a standardized precipitation index from arid regions. J. Arid Environ. 2021, 189, 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, I.; Pal, S. Modelling human health vulnerability using different machine learning algorithms in stone quarrying and crushing areas of Dwarka river Basin. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 66, 1351–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods; Charles Griffin: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

| SPI Value | Drought Category |

|---|---|

| 2.0, +∞ | Extreme wet |

| 1.5, 2.0 | Severe wet |

| 1.0, 1.5 | Moderate wet |

| −1.0, 1.0 | Normal |

| −1.5, −1.0 | Moderate drought |

| −2.0, −1.5 | Severe drought |

| −∞, −2.0 | Extreme drought |

| Data Base: 1223 Observations for 100 Years | |

|---|---|

| Learning: 978 obs. | Testing: 245 obs |

| 80% of the data base | 20% of the data base |

| SPI Time Scale | Trend | Slope | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPI24 | Increasing | 0.000205 | 0.013160 |

| SPI18 | Increasing | 0.000204 | 0.011759 |

| SVR Model | Model Performances | |||

| RMSE | MSE | r | R2 | |

| SPI_1 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.85 | 0.70 |

| SPI_3 | 0.66 | 0.43 | 0.81 | 0.61 |

| SPI_6 | 0.61 | 0.37 | 0.84 | 0.65 |

| SPI_12 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.93 | 0.85 |

| RF Model | Model Performances | |||

| RMSE | MSE | r | R2 | |

| SPI_1 | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.48 |

| SPI_3 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.43 |

| SPI_6 | 0.71 | 0.51 | 0.81 | 0.53 |

| SPI_12 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.88 | 0.73 |

| kNN Model | Model Performances | |||

| RMSE | MSE | r | R2 | |

| SPI_1 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 0.84 | 0.72 |

| SPI_3 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.81 | 0.60 |

| SPI_6 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.83 | 0.67 |

| SPI_12 | 0.51 | 0.26 | 0.84 | 0.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bouaziz, M.; Abid, M.A.; Medhioub, E.; John, A. A Century of Data: Machine Learning Approaches to Drought Prediction and Trend Analysis in Arid Regions. Water 2025, 17, 3567. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243567

Bouaziz M, Abid MA, Medhioub E, John A. A Century of Data: Machine Learning Approaches to Drought Prediction and Trend Analysis in Arid Regions. Water. 2025; 17(24):3567. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243567

Chicago/Turabian StyleBouaziz, Moncef, Mohamed Amine Abid, Emna Medhioub, and André John. 2025. "A Century of Data: Machine Learning Approaches to Drought Prediction and Trend Analysis in Arid Regions" Water 17, no. 24: 3567. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243567

APA StyleBouaziz, M., Abid, M. A., Medhioub, E., & John, A. (2025). A Century of Data: Machine Learning Approaches to Drought Prediction and Trend Analysis in Arid Regions. Water, 17(24), 3567. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243567