Abstract

The primary strata of western Taiwan are Cenozoic sedimentary rocks. Characterized by low cementation and high porosity, these rocks exhibit a pronounced wetting–softening effect. Long-term exposure to warm, humid tropical and subtropical climates significantly degrades their engineering geological properties due to weathering. This study, based on a sandstone-shale interbedded highway slope in central Taiwan that has repeatedly collapsed, investigated the slope’s failure mechanism using remote-sensing image interpretation of previous landslides, surface geological surveys, kinematic analysis, photogrammetric mapping, laboratory artificial weathering experiments, and Distinct Element Method (DEM) simulations. The study revealed that the fundamental cause of collapse on this type of oblique-slope interbedded sandstone-shale is the sliding and toppling of sandstone blocks, driven by weathering and erosion of the shale. Based on artificial weathering experiments, the strength loss rate of the shale in the Kuantaoshan Sandstone Member of the Kueichulin Formation after weathering is 6.6 times that of the sandstone. The estimated collapse area from the two-dimensional Distinct Element Method analysis is consistent with the actual value from the photogrammetric model. This type of landslide caused by rock weathering always forms stepped surface where sandstone overhangs above shale. A shale erosion amount of 0.78–0.91 of the spacing of the joint approximately parallel to the slope surface was found to be the critical erosion before collapse and can serve as the early warning indicator.

1. Introduction

Globally, rainfall-induced landslides pose significant threats to infrastructure and public safety, necessitating a robust understanding of their triggering mechanisms in varied environments [1,2,3,4]. The critical role of precipitation is evident in the reliance of hazard early warning systems (LEWS) on intensity-duration thresholds [5], exemplified by the dependence of translational slides in Italy on antecedent cumulative rainfall [6]. The destabilization process is primarily driven by hydro-mechanical coupling: infiltration increases pore water pressure, reducing effective stress and shear strength [2]. This mechanism applies to both shallow landslides and deep-seated gravitational slope deformations (DSGSD) under extreme rainfall scenarios [7]. Crucially, the susceptibility of a slope is modulated by lithological heterogeneity. Specific failure mechanisms include reductions in shear strength parameters in red basalt soils [2], degradation of mudstone in bedding rock masses [8], and hydraulic conductivity contrasts at soil-sandstone interfaces [9]. To capture these complex dynamics, recent studies have adopted advanced modeling techniques. Fluid-solid coupling analysis [10] and integrated physically based models, such as TRIGRS and Scoops3D [11], have proven effective for quantifying stability variations. Notably, applications in the southeastern Tibetan region reveal that extreme rainfall events can rapidly reduce slope stability in weathered bedrock. Consequently, accurate landslide prediction requires a holistic approach that accounts for the multifaceted interactions between hydrological forcing, geological structure, and weathering conditions [3].

Taiwan lies within an active orogenic belt, where the western part is predominantly composed of weak Cenozoic sedimentary strata. Characterized by low cementation and high porosity, these weak rocks, particularly the Cholan and Mushan sandstones, exhibit nonlinear elastic and elastoplastic deformation behaviors that differ significantly from those of hard rocks [12,13]. Research indicates that macroscopic mechanical parameters, such as uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) and Young’s modulus, are strongly correlated with petrological characteristics, notably porosity and grain area ratio (GAR) [14,15]. Porosity has been identified as the governing factor for UCS, exerting a greater influence than either grain or matrix content [14]; specifically, UCS demonstrates an inverse relationship with porosity and a direct relationship with GAR [15]. In addition to their mechanical behavior, Taiwan’s weak sandstones display deleterious engineering properties, including shear dilation, creep, and wetting-induced softening (a reduction in strength upon saturation) [14]. Furthermore, argillaceous formations such as the Lichi Melange, a product of the Luzon Arc collision, undergo significant degradation due to prolonged exposure to the region’s warm, humid climate [16]. Although early-stage weathering may yield a temporary increase in strength, continued exposure inevitably compromises material stability [16]. Given the susceptibility of these poorly cemented, porous lithologies to weathering, elucidating their degradation mechanisms is critical for assessing regional geological hazards, as this material and structural deterioration is a primary driver of landslide potential [17].

Weathering involves complex chemical processes, such as silicate weathering [18,19] and pyrite oxidation [20,21]. In active orogenic belts such as Taiwan, high erosion rates can expose sulfide-containing rocks to the surface. Sulfate produced by sulfide oxidation accelerates chemical weathering rates and reduces the shear strength of the rock mass [1]. Material weathering is also a key indirect factor in earthquake-induced landslides. For example, in the large Donghekou landslide triggered by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, the combination of slate weathering and liquefaction of the runout path significantly enhanced the mobility of the sliding mass [22]. In non-seismic scenarios, rainfall infiltration combined with weathering can form preferential failure surfaces at the laterite-sandstone interface, thereby reactivating landslides [10]. Therefore, in geologically active areas with weak rock, such as Taiwan, studying how weathering degrades rock mass strength and stiffness [23] provides the scientific basis for assessing long-term slope stability risks.

Rock formations composed of alternating competent and incompetent strata present significant geotechnical challenges due to their heterogeneity [24,25,26,27,28]. The primary instability mechanism is differential degradation, where the weathering of soft lithologies undermines more complex layers, inducing failure modes ranging from rockfalls to DSGSDs [25,26,29,30]. These failures are frequently triggered by precipitation-induced fluctuations in pore pressure [27,30,31]. Accurate characterization requires a multi-disciplinary approach. Rock mass properties can be estimated using rock mass classifications and field tests. At the same time, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Structure-from-Motion (UAV-SfM) photogrammetry facilitates the generation of three-dimensional models and remote discontinuity mapping [26,27,32]. Subsurface geometries can be further delineated via geophysical surveys, such as Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) supported by seismic methods [30,33]. Synthesizing these investigations, quantitative stability assessment can be performed through integrated monitoring and numerical modeling [27,28,29,30,31].

This study focused on sedimentary rock slopes in central Taiwan that have repeatedly collapsed. The study combined remote sensing image interpretation to reconstruct the spatial and temporal distribution of collapses over the years and explore their relationship with rainfall. Based on geological surveys, it was initially concluded that the primary type of slope failure was block movement along discontinuities in the rock mass. At the same time, the collapsing deposits mostly originated from the collapse of highly weathered rock masses. To clarify the mechanism of the disaster, this study conducted discontinuity investigations, photogrammetric mapping, and rock sampling for artificial weathering experiments. The failure mechanism was comprehensively determined based on discontinuity orientation, morphological changes observed in photogrammetric models, and differences in weathering resistance between the interlayered sandstone and shale. Two-dimensional Distinct Element Method (DEM) analysis was then employed to simulate the landslide process, and the results were cross-validated against geomorphological variation data to investigate the causes of collapse in interlayered rock slopes under rainfall-induced differential weathering.

2. Study Case

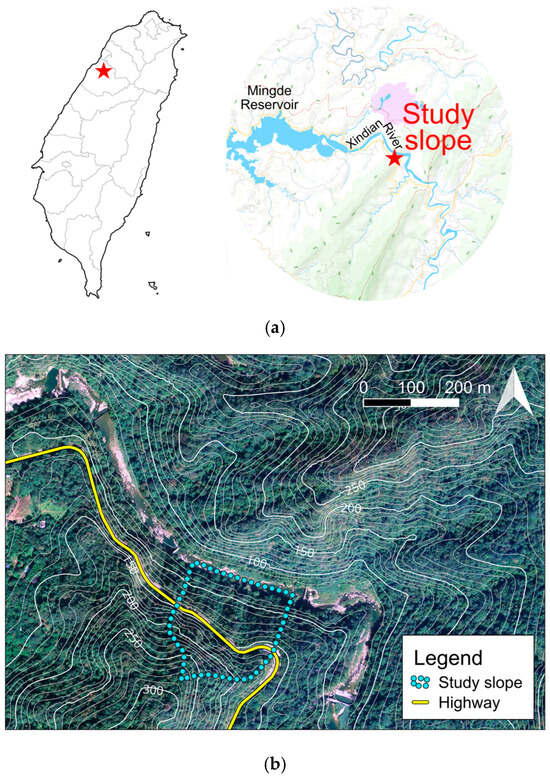

The case slope is located on the south bank of County Road 126, upstream of the Mingde Reservoir in central Taiwan (Figure 1). The lithology and thickness of each lithological unit along the highway vary significantly, ranging from shale to shale-sandstone, which makes slope failures common. Photos taken after the 30 March 2022, landslide reveal that the slope is composed of jointed rock masses. The residual colluvial deposits on the slope include weathered debris layers and blocks of varying sizes. The slope geometry is clearly controlled by several sets of discontinuities (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Location and topographic map of the study case, (a) regional topographical map and (b) local topographical map for the study slope.

Figure 2.

A photo taken before a landslide on (a) 27 July 2021, and (b) after that on 30 March 2022. The study slope is primarily composed of weathered, muddy sandstone and shale, and discontinuities significantly influence the landslide.

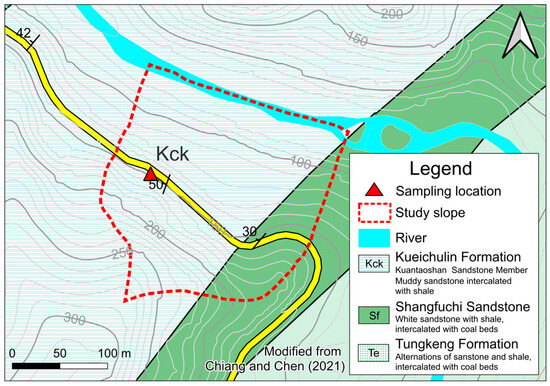

The study slope comprises the Late Miocene rock layers from the Kuantaoshan Sandstone Member (Kck) of the Kueichulin Formation, and the Shangfuchi Sandstone (Sf). According to Chiang and Chen (2021) [34], the lithology consists of muddy sandstone intercalated with shale, white sandstone intercalated with shale, and coal beds (Figure 2 and Figure 3). However, the major large-scale collapses in the western region occurred in the Kck; therefore, this study focuses on this formation. The bedding orientation in the region strikes approximately 210–220 and dips 30–50°, resulting in an oblique intersection of the rock formations and the slope surface. Sandstone forms relative protrusions, whereas shale forms depressions (Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Geological conditions and sampling location of the rock specimen. Modified after Chiang and Chen (2021) [34].

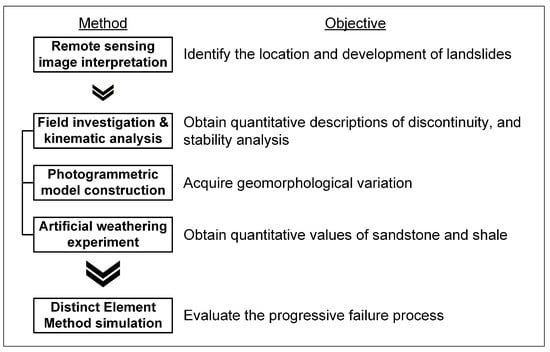

3. Methodology

It is found that the geometry of the study slope is dominated by several sets of discontinuities, composing an inclined stepwise appearance (Figure 2) that implies rock block movement. Before the landslide, the shale layer indented and the sandstone layer overhung, as shown in Figure 2a. Fallen sandstone blocks and shale fragments were scattered on the slope and on the road. The exposed slope surfaces are slightly to moderately weathered, but the colluvial deposits are likely a combination of highly weathered rock masses, both sandstone and shale. To investigate the relationship between rock weathering and collapses, this study combined remote sensing image interpretation, field investigation, kinematic analysis, photogrammetric model construction, artificial weathering experiment, and DEM simulation to clarify the mechanism and extent of the landslide (Figure 4). Remote sensing image interpretation is first used to identify the most frequent landslide locations and determine how they developed. During the field investigation, lithological units were identified, and orientation and spacing were measured and statistically analyzed for later DEM model building. Kinematic analysis provides preliminary confirmation of the possible collapse movement types. The photogrammetric method was used to generate the Digital Surface Model (DSM) to capture geomorphological variation. Sandstone and shale blocks were collected for artificial weathering experiments to assess the differences in weathering resistance between the two rock types. Applied the results from the field investigation, DEM simulations return the initiation and development of a collapse.

Figure 4.

Methods and their corresponding objectives in this study.

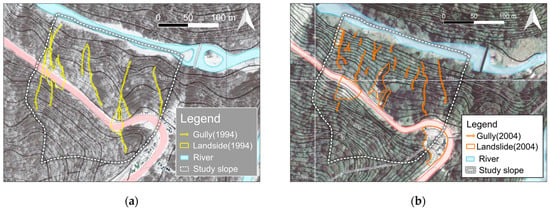

4. Remote Sensing Image Interpretation

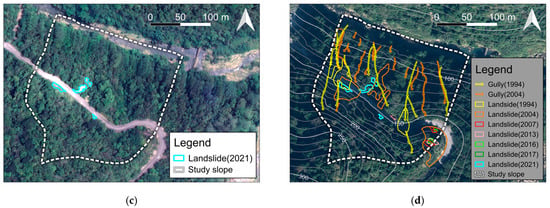

This highway was completed in 1986. Twelve aerial orthophotos collected from 1978, 1986, 1994, 2004, 2007, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2019, 2021, and 2022 show significant gully development on the lower slope of the highway in 1994. Landslides occurred on the western boundary in 2004, 2017, 2021, and 2022, with occasional small-scale landslides on the southeastern boundary (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Landslides and gullies developed from 1994 to 2022, as determined by aerial orthophotography interpretation. Results of (a) 1994, (b) 2004, (c) 2021, and (d) 1994 to 2022, where the underlying aerial photo was taken in 2022.

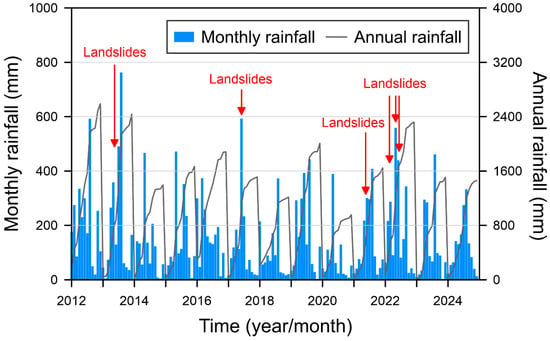

The nearest meteorological station is 7.68 km from the study slope. Annual rainfall from 2012 to 2024 ranged from 956.5 to 2590.5 mm (Figure 6), with an average value of 1738.3 mm. The maximum daily rainfall reached 402 mm, with an average of 9.4 rainy days per month, and the primary rainy season is from March to August. Comparing rainfall records from 2012 to 2024, the collapse events all occurred during March to June, when annual rainfall increased rapidly, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Monthly precipitation, yearly cumulative rainfall, and landslide events. Landslides typically occur between March and June, when the annual rainfall begins to increase.

5. Investigation, Survey, and Experiment

5.1. Field Investigations and Kinematic Analysis

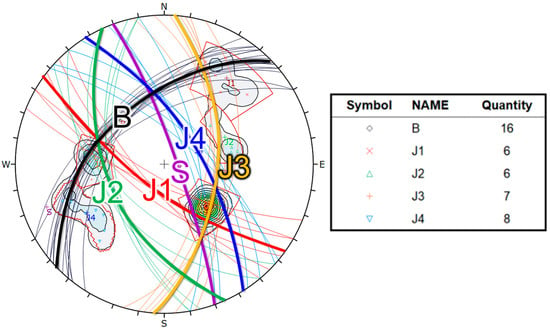

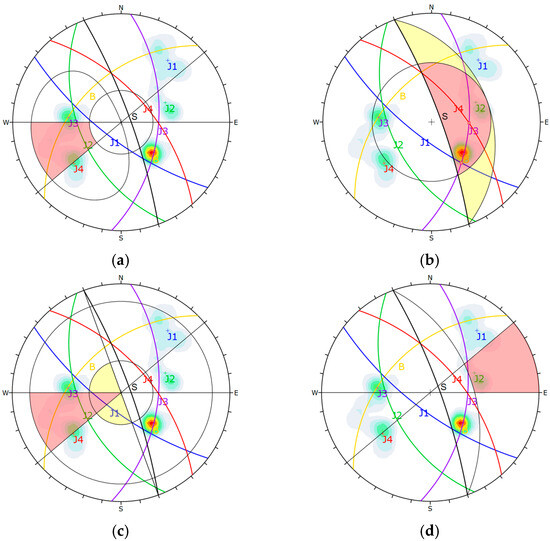

Based on the methods recommended by the International Society for Rock Mechanics (ISRM), a field survey of discontinuities was conducted [35]. Five groups of discontinuities, comprising 36 measurements in total, were studied. Assuming the weak plane orientations conform to a Fisher distribution, Rocscience Dips statistics were used to analyze the results, as shown in Figure 7. The average orientation of the bedding plane (B) is 225/44 (strike/dip, right-hand rule), the average orientation of joint 1 (J1) is 125/71, the average orientation of joint 2 (J2) is 136/49, and the average orientation of joint 3 (J3) is 004/50. The average orientation of joint 4 (J4) is 328/64. J4 has a similar orientation to the slope surface, with a dip angle difference of only 11°. Several J4 planes roughly parallel to the slope surface were also observed on site (Figure 2). Based on the results of the 36-discontinuity survey, a kinematic analysis was conducted to identify potential failure mechanisms (Figure 8). The friction angle was set to be 32.7° based on test results from the same stratum in the adjacent area. The analysis results showed that J3 and J4 in the case slope could lead to planar failure, wedge failure, direct toppling, and flexural toppling. The combinations of the bedding plane and J4, J1 and J3, and J3 and J4 could lead to wedge failure. J2 could lead to flexural toppling.

Figure 7.

Results of discontinuity investigation.

Figure 8.

Kinematic analysis of the study slope. Possible failure mechanisms include (a) plane failure, (b) wedge failure, (c) direct toppling, and (d) flexural toppling.

5.2. Photogrammetric Model

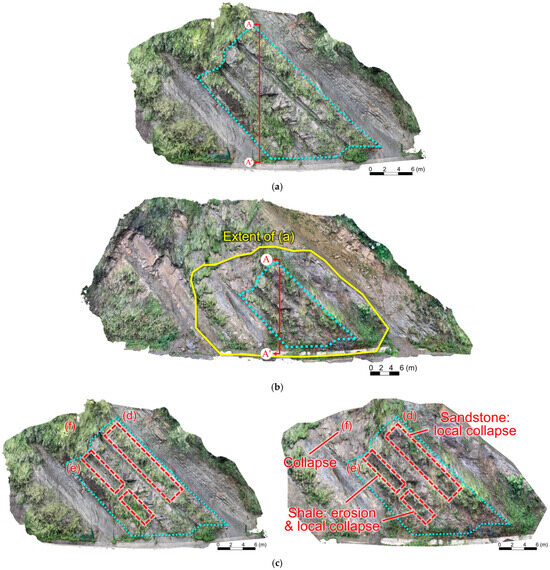

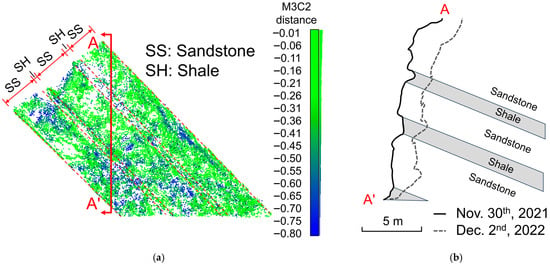

Figure 9a,b show a close-range photogrammetric model of the case slope, conducted on 30 November 2021, and 2 December 2022, respectively. The on-site images were used to generate 3D models in Agisoft Metashape. During the two photogrammetric mapping, landslides of varying sizes occurred on 28 March, 7 April, and 14 May 2022. Comparison of the A–A’ sections in the two images reveals that a new landslide developed laterally and upward, but some vegetation remained on the slope. Comparison of the two models reveals morphological variation near the A–A’ section, as shown in Figure 10a. The slope experienced a general retreat of 0.01 to 0.80 m, with larger collapses scattering at the upper left and the middle to lower right regions. Along profile A–A’, the collapse area was mainly contributed by sandstone layers (Figure 10b).

Figure 9.

Three-dimensional model of the study slope, created using photogrammetry, before and after the landslides in early 2022. Models built from (a) 30 November 2021, (b) 2 December 2022, and (c) comparison of the geomorphological variation. The main differences including local collapse of sandstone at (d), erosion and local collapse of shale at (e), and collapse at (f).

Figure 10.

Morphological variation between 30 November 2021, and 2 December 2022, around profile A–A’ in Figure 8. (a) Front view and (b) profile view (Unit: m).

5.3. Artificial Weathering Experiment

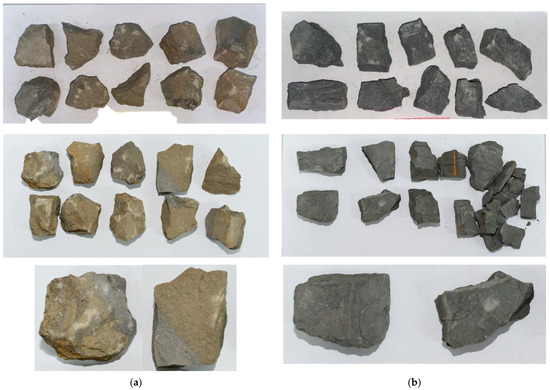

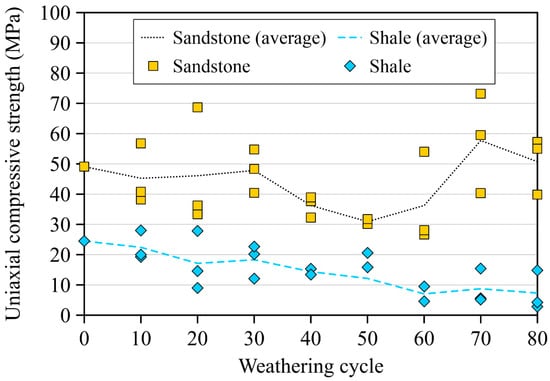

To quantify the weathering rates of sandstone and shale, specimens of the two lithologies were retrieved from the case slope and subjected to laboratory artificial weathering experiments (Figure 11). Field weathering conditions were simplified to two rainfall-related variables: temperature and humidity. The artificial weathering environment was designed based on the average monthly temperature and humidity of the coldest and warmest months in the study area. Based on meteorological data from the past decade, the average temperature in the coldest month of the study area is 10 °C, with a relative humidity of 50%. In contrast, the average temperature in the warmest month is 30 °C, accompanied by a relative humidity of 70%. The artificial weathering experiment cycled between 10 °C and 50% humidity and 80 °C and 90% humidity. Each condition was maintained for 12 h, with each cycle lasting 24 h. A maximum of 80 cycles was performed, with 10 cycles forming a cycle unit. After each cycle unit, three specimens were removed for point-load testing. The point-load indices were converted to uniaxial compressive strength [36], yielding a measure of rock strength change with weathering cycles (Figure 12).

Figure 11.

Rock specimens of (a) sandstone and (b) shale, before (upper one) and after (lower one) 70 and 80 artificial weathering cycles, respectively.

Figure 12.

Uniaxial compression strength with artificial weathering cycles from point load indices of sandstone and shale.

In the two lithologies studied, only the shale specimens showed significant changes in appearance during the weathering test. As shown in Figure 11a,b, the upper and lower figures compare specimens before and after 70 and 80 cycles. The sandstone exhibited no significant spalling or color change during the test. Based on the definition of ISRM on the weathering grade of rocks [35], the shale specimens were classified as slightly weathered after 80 cycles of weathering. However, differences in the weathering grade of the rocks between cycles can still be observed. After 10 and 20 cycles, the shale specimens showed only minor iron staining. After 30 cycles, the specimens developed noticeable iron staining and several visible microcracks. After 40 cycles, in addition to iron staining and microcracks, the specimens also showed localized spalling caused by the cracks. After 50 cycles, the shale specimens showed extensive iron staining and a powdery appearance. After 60 and 70 cycles, the number of cracks increased significantly, and some specimens broke into flakes, with localized surface iron staining and a pulverized appearance at the edges. After 80 cycles, all specimens showed visible cracks, and most specimens broke into several pieces, as shown in Figure 11b.

Figure 12 shows that the UCS of sandstone exhibits no downward trend in the initial weathering cycles (10 to 30 cycles). After 30 to 50 cycles, the strength continues to decline. A slight upward trend is observed between 50 and 70 cycles. The weathering environment then continues to weaken the specimen from 70 to 80 cycles. Figure 12 shows that the UCS of shale decreases with increasing weathering cycles, with a peak of 24.5 MPa at the beginning. Some specimens fractured and could not be used in point load tests at cycles 40, 50, and 60. The UCS of shale decreases to 7.31 MPa at 80 cycles, indicating that cracks within the specimens have led to a significant decrease in rock strength.

6. DEM Simulations of Landslide Process

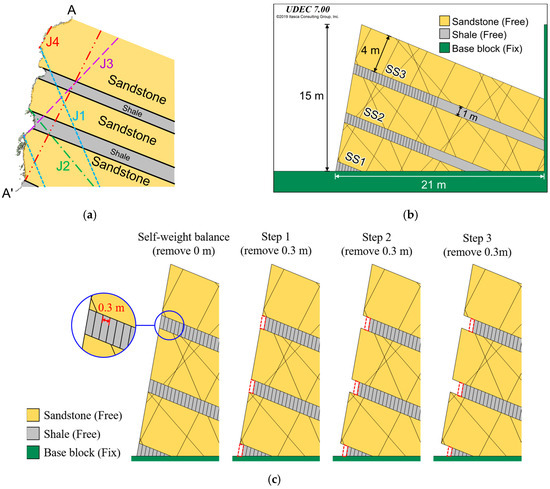

Itasca UDEC was used to assess progressive collapse failure in the study slope. The DEM numerical model is based on a 3D model constructed in November 2021. Section A–A’, where significant differential erosion occurs on the slope, was selected as the basis for model construction (Figure 9a). The slope bedding planes and joints were extended and simplified based on their orientations measured in the field investigation (Figure 13a). The model dimensions are 15 m in length and 21 m in width. The yellow blocks in the model represent sandstone with a thickness of 4 m; the gray blocks represent shale with a thickness of 1 m, resulting in a 4:1 sandstone-to-shale thickness ratio; and the green blocks represent the fixed base. To simulate the differential erosion of soft and hard rock layers in interbedded slopes, this study established erosion lines parallel to the slope surface in the shale, thereby simulating the gradual erosion of the weak rock layers over time.

Figure 13.

Numerical model and the modeling process of weathering-induced landslides. (a) Profile A–A’ from the three-dimensional model of 30 November 2021, and interpretations of discontinuities. (b) UDEC model simplified from (a). (c) At the beginning of each step, shale is assumed to be weathered and eroded to a depth of 0.3 m.

Differential erosion simulation was performed in a staged manner. The distance between erosion lines in shale is 0.3 m (Figure 13) to create a continuous erosion effect within an acceptable computation time. The simulation is divided into several stages. Stage 0 is a state of self-weight equilibrium. Each subsequent stage removes 0.3 m of shale from the slope. The specific process is as follows: Stage 0, self-weight equilibrium; Stage 1, 0.3 m of erosion; Stage 2, 0.6 m of erosion; Stage 30, 9 m of erosion; and so on. Each stage is calculated until force equilibrium is achieved; once that is achieved, the next stage is simulated. The process is shown in Figure 13c. During the simulation, the sandstone and shale are free to move without any boundary constraints, while the base rock is restricted in all directions. The physical properties and mechanical properties of intact rocks, and the mechanical parameters of joints, including density, Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, peak and residual friction angle, are based on experimental results [37] and drilling reports [38,39,40] as listed in Table 1. Rock materials were assumed to be elastic, and joints were modeled using the Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion, with cohesion neglected. However, the normal stiffness (kn) and shear stiffness (ks) of discontinuities are difficult to determine; therefore, they are estimated using the recommended equations by Itasca (2019) [41]. First, the Rock Mass Rating estimation in the field investigation yields an average value of 49.8, corresponding to a Modulus Reduction Factor (MRF) of 0.18 according to Singh (1979) [42].

: Young’s modulus of rock masses; : Young’s modulus of rock material.

Normal stiffness of joints was derived after Equation (2) [39] and Equation (3):

where s: spacing, : shear modulus of rock masses, : shear modulus of rock material.

Table 1.

Material properties used in the DEM model.

Table 1.

Material properties used in the DEM model.

| Rock Type | Density (kg/m3) 1 | Young’s Modulus (Pa) 1 | Poisson’s Ratio 1 | Normal Stiffness (Pa/m) 2 | Shear Stiffness (Pa/m) 2 | Peak Friction Angle (°) 3 | Residual Friction Angle (°) 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandstone | 2547 | 7.4 × 109 | 0.33 | 3.6 × 108 | 1.35 × 108 | 32.7 | 27.1 |

| Shale | 2280 | 1.28 × 108 | 0.33 | 6.66 × 107 | 2.5 × 107 | 24.4 | 22 |

Notes: 1. Sandstone: Chang (2014) [37]. Shale: Kenkul Corporation (2011) [38]. 2. Itasca (2019) [41]. 3. Sandstone: Kuang-I Engineering Co., Ltd. (2013) [39]. Shale: Hsin Yi Chang Construction Co., Ltd. (2016) [40].

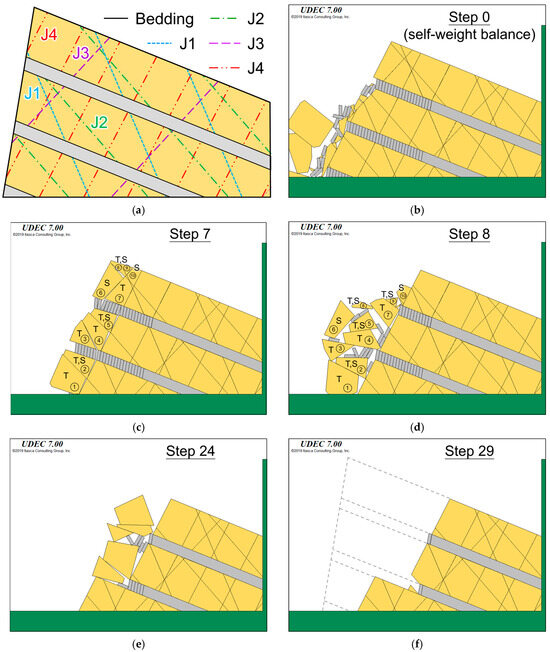

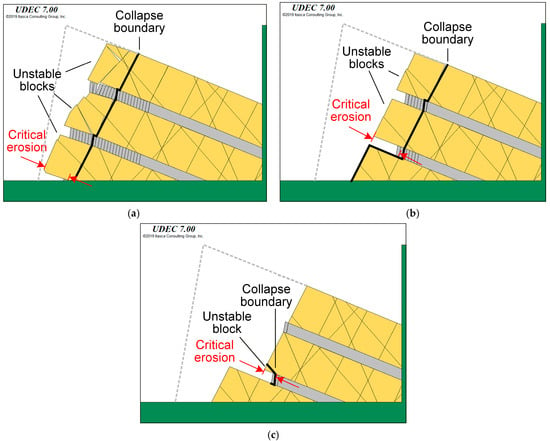

Figure 14 illustrates the numerical results for case slope failure due to differential erosion. After each analysis stage, all loose blocks on the slope surface were removed before the next simulation stage. Therefore, the figure only shows the rock blocks that collapsed during that stage. Figure 14 lists only the stages where failure occurred. From self-weight equilibrium (stage 0) to stage 30, it is found that shale erosion damage causes joints J3 and J4 to form a new slope surface for the next stage. In stage 0, after self-weight equilibrium, the sandstone blocks at the slope toe slid down along J4 due to insufficient support at the bottom, causing a large number of rock blocks above to slide along joints J3 and J4 (Figure 14a). In stage 1, the slope remains stable (Figure 14b). In stage 8, after the shale eroded for another 2.1 m compared to stage 1, the rock blocks in the sandstone layer SS1 (see Figure 13b for location) first rotate outward, causing the rock blocks in SS2 and SS3 that J4 cuts to rotate outward and fall forward (Figure 13c). In Stage 22, the slope had not yet failed, but the joints between SS2 and SS3 remained open (Figure 14d). In Stage 24, the sandstone blocks in SS2 topple forward when the underlying shale erodes to within 0.3 m of the joints, causing the rock blocks cut by the joints in SS3 to rotate forward (Figure 14e). In Stage 29, sandstone blocks in SS2 fell due to the shale erosion, similar to Stage 1 (Figure 14f).

Figure 14.

Progress of rock weathering-related landslide failure. (a) Discontinuity set numbers (b) step 0, right after self-weight balance, (c) step 7, (d) step 8, (e) step 24, and (f) step 29. In (c,d), S: sliding, T: toppling, F: falling.

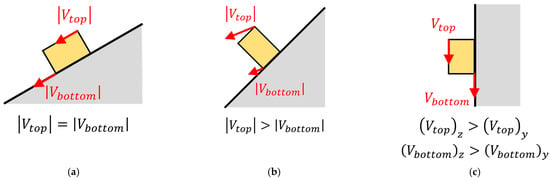

By observing changes in the sandstone block failure area at each stage and summarizing their regularity, the simulation from self-weight equilibrium to Stage 30 revealed three large collapses with failure areas exceeding 10 m2. The landslide process shows that the failure phenomena at each stage are closely related to the geometry of the rock blocks cut by the joints. Based on the numerical results and references Cano & Tomás (2013) [25,26] and Lin (2019) [43], the failure modes can be categorized into three: sliding, toppling, and falling. Revised from Line (2019) [43], block movement of each failure mode can be written as Figure 15, where sliding contains equal velocity of the top and the bottom edge of the block, toppling involves larger velocity in the top edge than the bottom edge and falling refers to movement with higher vertical velocity than horizontal velocity. Based on the categorization, it is found that a collapse event usually begins with the toppling of sandstone blocks above shale layers, such as blocks 1 and 3, but sometimes with a sliding block, like block 6 (Figure 14c). Toppling occurs when the line of gravity of the rock block passes beyond the toe of its base because of shale erosion. Rock blocks taking J3 or J4 as their inner boundary should overcome the shear strength along this surface to initiate sliding, as in block 10 in Figure 14c,d. Some blocks consist of both toppling and sliding. Block 2 slides along the interface between blocks 1 and 2 as it topples. As blocks detach completely from the slope surface, falling begins.

Figure 15.

Equations defining block movement in three failure modes. (a) Sliding, (b) toppling, and (c) falling, where : velocity of the highest corner, : velocity of the lowest corner, , . , are the two components of in x and z direction, where x refers to the horizontal direction, and z to the vertical direction. The highest and lowest corner are defined according to the original state or the state right after previous collapse of a rock block (modified from Lin, 2019 [43]).

Therefore, the initial failure in the simulation is often triggered by instability at the toe of the sandstone block, which in turn causes the rock blocks in the middle and upper parts of the slope to fail. As erosion deepens, the center of gravity of the rock slope gradually shifts upward, transforming into a failure mode dominated by the middle sandstone block.

7. Discussion

Rainfall and landslide records show a strong correlation between these two. Over the past 12 years, all landslides on the case slope have occurred during the rainy season. Although the rock mass after the slope collapse was only slightly to moderately weathered, the remaining colluvial deposits on the slope surface are the result of highly weathered rock mass, indicating that when weathering reaches a certain level, a landslide will occur. Results from artificial weathering tests show that the average UCS of shale decreased continuously from 24.5 MPa to 7.31 MPa, representing a 70.16% decrease. The average UCS of sandstone decreased from an initial 49.1 MPa to a minimum of 30.91 MPa, before ultimately returning to 50.72 MPa. This is likely due to uneven initial weathering grade within the collected rock samples. In particular, the point load tests required small, individual samples weighing approximately 400–600 g, making them susceptible to localized heterogeneity and property variation. The sandstone has only slightly degraded following artificial weathering experiments; therefore, an average UCS across all 80 cycles was calculated at 43.87 MPa, which is considered the strength after weathering. This represents a 10.65% decrease compared to the initial strength of 49.10 MPa. Comparing the strength reduction ratios of sandstone and shale, the weathering strength reduction ratio of sandstone to shale is approximately 1:6.6. This ratio is considered the weathering resistance ratio of sandstone to shale.

Since considering sandstone weathering in the UDEC simulation would make the model too complicated, the numerical model only considered shale weathering. Therefore, the numerical collapse volume was added to the sandstone weathering volume, and the three-dimensional collapse volume was corrected based on the width of the comparison range. The collapse volume of the two-point cloud variations was 258 m3. During the simulation process, the sandstone collapse areas at Steps 8 and 24 were 34.8 m2 and 23.9 m2, respectively. The shale weathering erosion at the time of collapse was 2.4 m2 and 4.8 m2. Using the sandstone-to-shale weathering rate ratio and the rock layer thickness, the sandstone weathering areas were calculated to be 1.45 m2 and 2.91 m2. The corrected numerical collapse areas, after totaling, were 38.65 m2 and 31.61 m2. The collapse area of profile A–A’ from photogrammetric DSMs is 34.53 m2 (Figure 10b). Hence, the simulated collapse areas are 1.12 and 0.92 times the actual collapse area, accounting for 8–12% error.

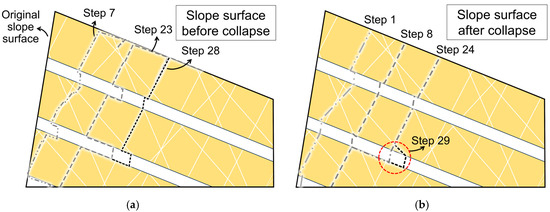

Kinematic analysis results show four potential failure modes for the case slope: plane failure, wedge failure, direct overturning, and flexural overturning (Figure 8). The UDEC analysis results (Figure 14) show plane failure along J3 and J4, direct toppling of the rock block with J3 and J4 as the base, and flexural toppling of the rock block with J2 as the boundary. Wedge failure, in which the rock block slips along the intersection of two weak planes, is challenging to observe in two-dimensional analysis. In addition to wedge failure, the other failure modes identified in the kinematic analysis are also observed in the UDEC simulation. The slope stability degrades gradually in three steps: shale erosion, sandstone blocks losing stability, and collapse. According to DEM analysis, toppling is the dominant failure mode in the collapse of the study slope, followed by sliding and falling. Toppling, however, occurs when shale erosion exposes the block’s line of gravity. One step before collapse, there are always erosions more than half the spacing of J4 (hereafter denoted as S4), as shown in Figure 16a,b. To obtain a quantitative measure of shale erosion leading to collapse, the outlines before and after a collapse are compared in Figure 17. Until the collapse in step 8, a critical erosion of 2.71 m occurs, equivalent to 0.78S4 (Figure 17a). The other two collapses occur at shale erosion levels of 3.16 m and 1.42 m, corresponding to 0.91S4 and 0.41S4, respectively (Figure 17b,c). Exclude the local collapse in step 29, the critical erosion is approximately higher than 0.75S4. It is fair to replace S4 with the spacing of the release joint or tension cracks that grow parallel to the slope surface. To estimate the critical erosion of an interbedded slope, key factors include joint orientation, joint spacing, joint shear strength, and the weathering resistance of intact rock.

Figure 16.

Development of slope surfaces (a) a step before collapse, and (b) after collapse.

Figure 17.

Comparison of slope features before and after collapse. (a) Step 7 to step 8, (b) step 23 to step 24, and (c) step 28 to step 29, where only a rock block falls. The gray dashed lines indicate the original slope surface.

Although the numerical results provide an accurate estimation of the collapse amount for Profile A–A’, many aspects must be considered when extending to a broader range. For instance, current numerical analysis assumes that all discontinuities are 100% persistent, that the rock mass is homogeneous, and that discontinuity orientations are consistent. However, discontinuities are often not completely fractured but instead partially connected by rock bridges, which provide additional strength, unlike in numerical models. These rock bridges significantly enhance the slope’s stability. The weather conditions differ from the surface to the interior of the slope, making the exterior part more vulnerable. Therefore, failure may occur at the boundary between different weather conditions within a rock block, rather than at its boundaries, and result in less collapse. Variation in the orientations of discontinuities is also inherent. However, the mean vector directions of each set of discontinuities are used to generate the DEM model, producing a representative estimate of the slope failure and amount. There is also a difference between two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) analysis. In 2D analysis, a profile of the slope was taken as the representative. But from Figure 10a, it is clear that the collapse areas are unevenly distributed, and that a simple estimate of the 3D collapse volume by multiplying the 2D collapse area by the slope width can produce considerable error. The error arises from the assumption that all joints along the slope width extend infinitely, with a relative geometry consistent with the slope surface; this implies that all discontinuities are parallel to the slope surface but differ only in dip, which is inconsistent with the actual 3D situation. For this case, a reduction factor of 0.44–0.63 should be taken to obtain an acceptable estimation of 3D collapse volume. Based on the results, this study concludes that UDEC has made a significant contribution to the analysis of the failure mechanism and stability assessment in this case. The failure of the slope in this case was primarily due to the toppling of the sandstone after the loss of the supporting shale layer, as well as to sliding at the interface between the sandstone and shale layers and at other intersecting joint lines. The occurrence of collapse also has a specific periodic pattern.

8. Conclusions

To clarify the mechanism of the collapse of interbedded sandstone and shale slopes in central Taiwan, this study investigated the connection between rainfall records and collapse events. From the slope’s appearance, the case exhibited significant patterns of block movement. The rock layers were relatively young Taiwanese sedimentary rocks characterized by poor cementation and susceptibility to wetting–softening. This study investigated potential failure modes by examining discontinuity orientations and conducting kinematic analysis. Photogrammetry was used to construct two three-dimensional models of the case, during which multiple collapses occurred. Geomorphological changes before and after the collapses revealed an inward retreat of 0.01–0.80 m in the lower slope. To quantify the weathering rates of sandstone and shale under rainfall, rock samples were collected from the site and subjected to an artificial weathering experiment designed using temperature and humidity records from a nearby meteorological station. The rock specimens were subjected to cycles of high temperature and low humidity, followed by low temperature and high humidity. The change in the uniaxial compressive strength of the two rock types with the number of weathering cycles indicated a weathering rate ratio of 6.6:1 between shale and sandstone.

Kinematic analysis revealed four potential failure modes: planar failure, wedge failure, direct toppling, and flexural toppling. Each failure type contained multiple sets of catastrophic joints, resulting in a diverse group of unstable rock blocks. The DEM model, based on a cross-sectional analysis of the case study, considered the process by which sandstone blocks in a sandstone-shale interbedded slope destabilize due to continuous shale weathering and rainfall-induced erosion. This type of landslide follows three steps: shale erosion, sandstone blocks lose stability, and collapse. The block movement includes sliding, toppling, and falling. Although the appearance of the slope surface remains similar over time, the amount of shale erosion can serve as an indicator of a landslide. As the slope is about to collapse, shale erosion reaches 0.78 to 0.91 times the spacing of the joint that is approximately parallel to the slope surface. But the values still vary according to joint orientation, joint spacing, joint shear strength, and the weather resistance of intact rock.

The DEM-simulated failure mechanism broadly matched the kinematic analysis results, detailing the sliding and toppling of sandstone blocks along the joints after shale erosion, and presenting good agreement with the 2D-actual collapse area. Transforming the 2D collapse area to the 3D collapse volume, one needs to multiply the numerical collapse area by the width of the extent, 17 m, and by a reduction factor of 0.44 to 0.63. This difference is due to the DEM’s assumption of complete joint continuity, whereas rock bridges are actually present in the site’s joints. The heterogeneity from degrees of weathering and the inherent randomness of joint orientation also contribute to the difference. In practical applications, the reduction factor between the 2D-estimated and the 3D-actual collapse volume should be determined for each case. In general, this study investigated a typical landslide case controlled by rainfall-induced shale weathering, revealed the failure modes of rock blocks, and proposed a quantitative index of critical erosion to identify collapses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.C.; Data curation, C.Y.L., Y.L.T. and H.C.L. Formal analysis, C.Y.L.; Methodology, all authors; Software, C.Y.L. and H.C.L.; Visualization, Y.C.C., C.Y.L. and H.C.L.; Writing—original draft, C.Y.L., Y.L.T. and H.C.L.; Writing—review and editing, Y.C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, grant number MOST 109-2221-E-005-008-MY2. The APC was funded by National Chung Hsing University.

Data Availability Statement

The data underpinning the study’s conclusions are maintained by the host institution. In compliance with institutional and funding guidelines, the datasets are not publicly accessible but can be acquired from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The funding by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, is acknowledged. The contributions of Wei Chen Lo and Yu Cheng Tsai to establishing the foundation of artificial weathering experiments, as well as the support of Wei Chen Lo, Yu Cheng Tsai, Kuan Yu Shih, and Chun Tai Weng on field investigations, rock specimen collection and processing, are also greatly appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hilton, R.G.; West, A.J. Mountains, erosion and the carbon cycle. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.S.; Khau, T.L.; Huynh, T.T. Investigation of natural and human-induced landslides in red basaltic soils. Water 2025, 17, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, R.J. Landslide processes and landslide susceptibility analysis from an upland watershed: A case study from St. Andrew, Jamaica, West Indies. Eng. Geol. 1993, 34, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toll, D.G. Rainfall-induced landslides in Singapore. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Geotech. Eng. 2001, 149, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, F.; Gariano, S.L.; Peruccacci, S.; Brunetti, M.T.; Marchesini, I.; Rossi, M.; Melillo, M. Geographical landslide early warning systems. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 200, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiranti, D.; Rabuffetti, D.; Salandin, A.; Tararbra, M. Development of a new translational and rotational slides prediction model in Langhe hills (north-western Italy) and its application to the 2011 March landslide event. Landslides 2013, 10, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaseñor-Reyes, C.I.; Dávila-Harris, P.; Hernández-Madrigal, V.M.; Figueroa-Miranda, S. Deep-seated gravitational slope deformations triggered by extreme rainfall and agricultural practices (eastern Michoacan, Mexico). Landslides 2018, 15, 1867–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Y.; Dai, Z.W.; Luo, X.D.; Jiao, W.Z.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.X.; Zhang, N.; Xiong, Q.H. Deformation and failure mechanism of bedding rock landslides based on stability analysis and kinematics characteristics: A case study of the Xing’an Village Landslide, Chongqing. Water 2025, 17, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Liao, J.; You, Y.C.; Li, Z.B.; Zhou, C.Y.; Liu, Z. Mechanisms controlling multiphase landslide reactivation at red soil–sandstone interfaces in subtropical climates: A case study from the Eastern Pearl River Estuary. Water 2025, 17, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.Z.; Lu, G.Y.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Wu, L.R.; Zhang, L.; Luo, S.; Dong, J. Deformation and stability characteristics of layered rock slope affected by rainfall based on anisotropy of strength and hydraulic conductivity. Water 2020, 12, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.R.; Ma, X.M.; Wang, H.J.; Jia, L.Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.H. Spatio-temporal prediction of three-dimensional stability of highway shallow landslide in Southeast Tibet based on TRIGRS and Scoops3D coupling model. Water 2024, 16, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.C.; Jeng, F.S.; Hsieh, Y.M.; Tsai, L.S. An associated elastic–viscoplastic constitutive model for sandstone involving shear-induced volumetric deformation. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2010, 47, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.C.; Ling, H.I. Modeling the behavior of sandstone based on generalized plasticity concept. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Meth. Geomech. 2013, 37, 2154–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, F.S.; Weng, M.C.; Lin, M.L.; Huang, T.H. Influence of petrographic parameters on geotechnical properties of tertiary sandstones from Taiwan. Eng. Geol. 2004, 73, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.C.; Li, H.H. Relationship between the deformation characteristics and microscopic properties of sandstone explored by the bonded-particle model. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2012, 56, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.H.; Allison, R.J.; Jones, M.E. Weathering effects on the geotechnical properties of argillaceous sediments in tropical environments and their geomorphological implications. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 1996, 21, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, D.; Parise, M. Landslide types and their relationships with weathering in a Calabrian basin, southern Italy. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2005, 64, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.C.G.; Hays, P.B.; Kasting, J.F. A negative feedback mechanism for the long-term stabilization of Earth’s surface temperature. J. Geophys. Res. 1981, 86, 9776–9782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, R.A.; Lasaga, A.C.; Garrels, R.M. The carbonate- silicate geochemical cycle and its effect on atmospheric carbon dioxide over the past 100 million years. Am. J. Sci. 1983, 283, 641–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Chung, C.H.; You, C.F. Disproportionately high rates of sulfide oxidation from mountainous river basins of Taiwan orogeny: Sulfur isotope evidence. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blattmann, T.M.; Wang, S.L.; Lupker, M.; Märki, L.; Haghipour, N.; Wacker, L.; Chung, L.H.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Plötze, M.; Eglinton, T.I. Sulphuric acid- mediated weathering on Taiwan buffers geological atmospheric carbon sinks. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.H.; Huang, R.Q.; Lourenço, S.D.N.; Kamai, T. A large landslide triggered by the 2008 Wenchuan (M8.0) earthquake. Eng. Geol. 2014, 180, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ching, J.; Li, K.H.; Phoon, K.K.; Weng, M.C. Generic transformation models for some intact rock properties. Can. Geotech. J. 2018, 55, 1702–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segina, E.; Komac, B.; Zorn, M. Factors influencing the rockwall retreat of flysch cliffs on the Slovenian coast. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2012, 52, 304–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.; Tomas, R. Assessment of corrective measures for alleviating slope instabilities in carbonatic Flysch formations: Alicante (SE of Spain) case study. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2013, 72, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.; Tomas, R. Characterization of the instability mechanisms affecting slopes on carbonatic Flysch: Alicante (SE Spain), case study. Eng. Geol. 2013, 156, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Y.; Topal, T. Evaluation of rock slope stability for a touristic coastal area near Kusadasi, Aydin (Turkey). Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 4187–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, M.; Bertello, L.; Bernardi, A.R.; Caputo, G. Back analysis of a large landslide in a flysch rock mass. Landslides 2017, 14, 2041–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pánek, T.; Hartvich, F.; Jankovská, V.; Klimeš, J.; Tábořík, P.; Bubík, M.; Smolková, V.; Hradecký, J. Large Late Pleistocene landslides from the marginal slope of the Flysch Carpathians. Landslides 2014, 11, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalupa, V.; Pánek, T.; Šilhán, K.; Břežný, M.; Tichavský, R.; Grygar, R. Low-topography deep-seated gravitational slope deformation: Slope instability of flysch thrust fronts (Outer Western Carpathians). Geomorphology 2021, 389, 107833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, Z. Identification of flysch landslide triggers using conventional and ‘nearly real-time’ monitoring methods—An example from the Carpathian Mountains, Poland. Eng. Geol. 2018, 244, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.H.; Zhang, Z.S.; Wang, C.G.; Zhu, C.J.; Ren, Y.P. Multistep rocky slope stability analysis based on unmanned aerial vehicle photogrammetry. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tábořík, P.; Lenart, J.; Blecha, V.; Vilhelm, J.; Turský, O. Geophysical anatomy of counter-slope scarps in sedimentary flysch rocks (Outer Western Carpathians). Geomorphology 2017, 276, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.C.; Chen, P.T. Geological Map of Taiwan: Miaoli, 2nd ed.; Central Geological Survey, MOEA: New Taipei, Taiwan, 2021. Available online: https://gpi.culture.tw/books/1011002099 (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- International society for rock mechanics commission on standardization of laboratory and field tests: Suggested methods for the quantitative description of discontinuities in rock masses. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1978, 15, 319–368. [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.A. Suggested method for determining point load strength. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1985, 22, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.Y. Investigating the Injection Pressure for CO2 Geological Sequestration in Kuantaoshan Sandstone Formation. Master’s Thesis, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kenkul Corporation. Geotechnical Drilling Report for the Covered Playground of Dharma Drum Institute of Liberal Arts; Kenkul Corporation: New Taipei, Taiwan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Itasca Consulting Group, Inc. UDEC—Universal Distinct Element Code, Version 7.0 User’s Guide; Itasca Consulting Group, Inc.: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang-I Engineering Co., Ltd. Geotechnical Drilling and Test Excavation Works for the Year 2012 (Section A)—Foundation Drilling Report for Tower Nos. #98B, #98C, and #100 of the Tongxiao–Emei 345 kV Transmission Line; Kuang-I Engineering Co., Ltd.: Taoyuan, Taiwan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hsin Yi Chang Construction Co., Ltd. Geotechnical Drilling Report for Tower Nos. #49, #59, and #62 of the Tongxiao–Yiho 345 kV Transmission Line; Hsin Yi Chang Construction Co., Ltd.: Taichung, Taiwan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B. Geological and Geophysical Investigation in Rocks for Engineering Projects. In Proceedings of the International Symposium of In Situ Testing of Soils and Performance of Structures, Roorkee, India, 19–22 December 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.R. Characteristics of Joint Sets Affecting Wedges Deformation and Failure in Obsequent and Oblique Slopes. Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, June 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).