Instantaneous Relief and Persistent Control of Sludge Bulking: Changes in Bacterial Flora Due to Freeze–Thaw and Carbon Source Conversion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Equipment and Operation Mode

2.2. Synthetic Wastewater and Experimental Process

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Water Quality Analysis Methods

2.5. EPS Extraction Methods and Component Analysis Methods

2.6. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Illumina Sequencing

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

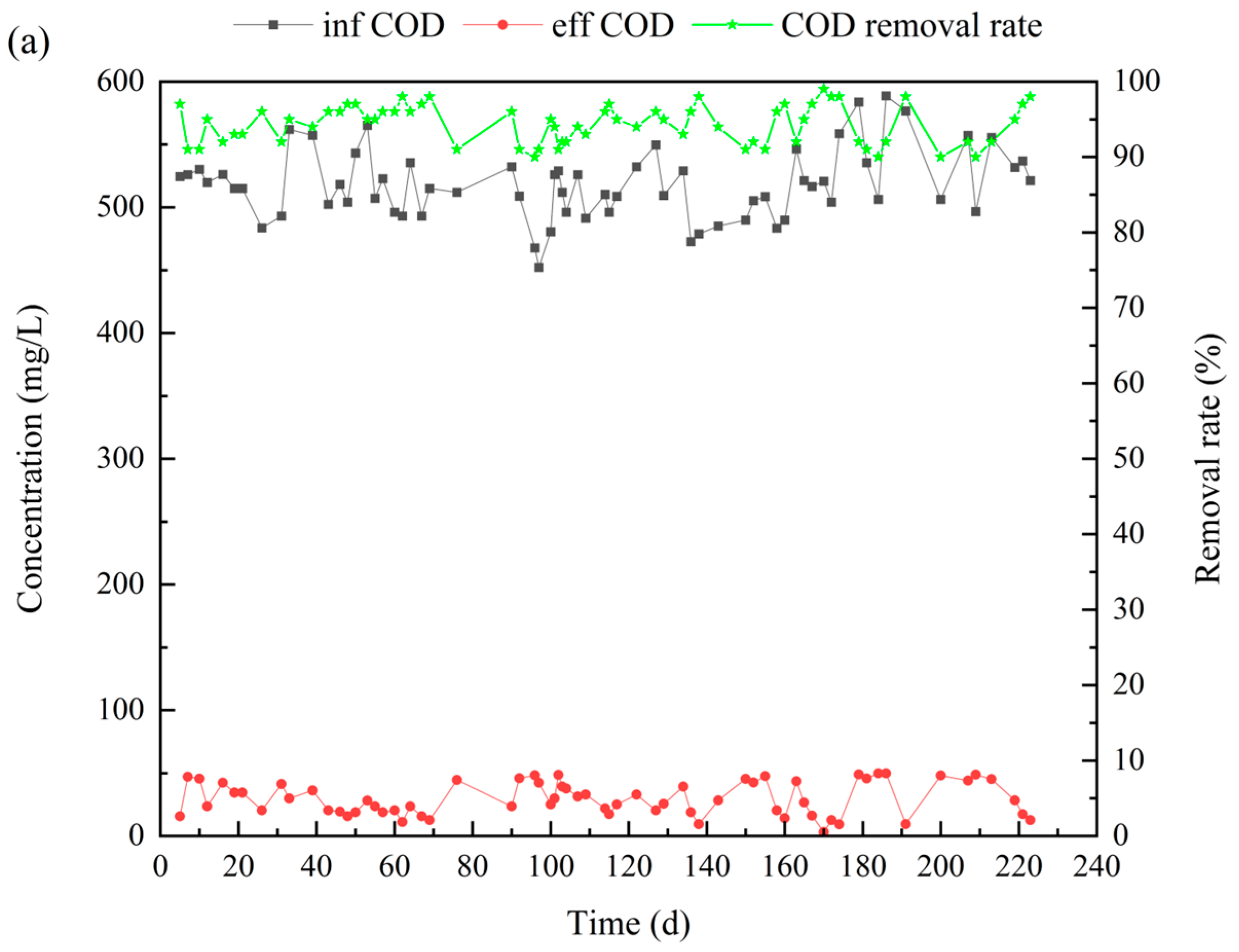

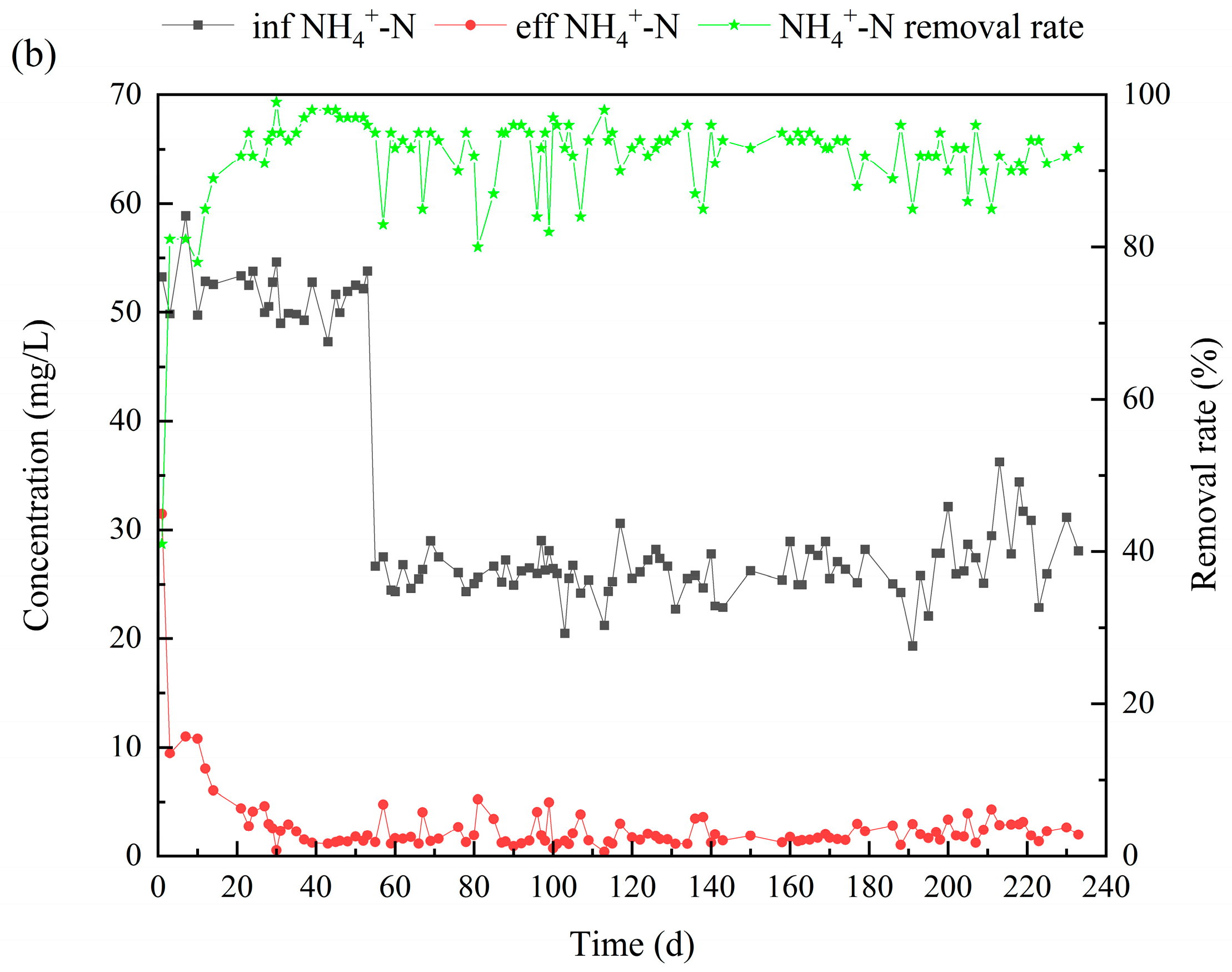

3.1. Performance of the Reactor

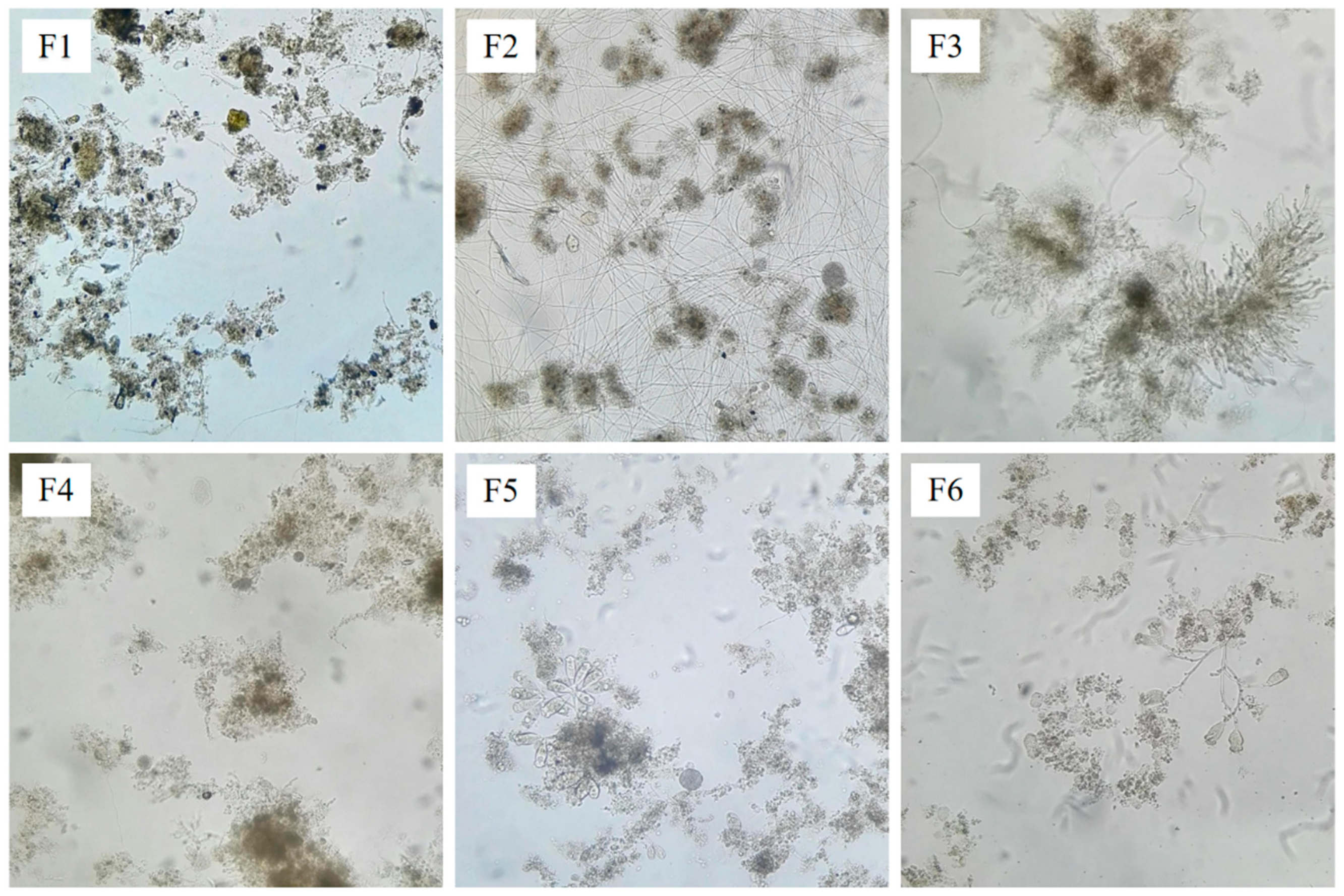

3.2. Microscopic Examination of Sludge

3.3. Structure of the Bacterial and Fungal Community

3.3.1. Bacterial Community Diversity

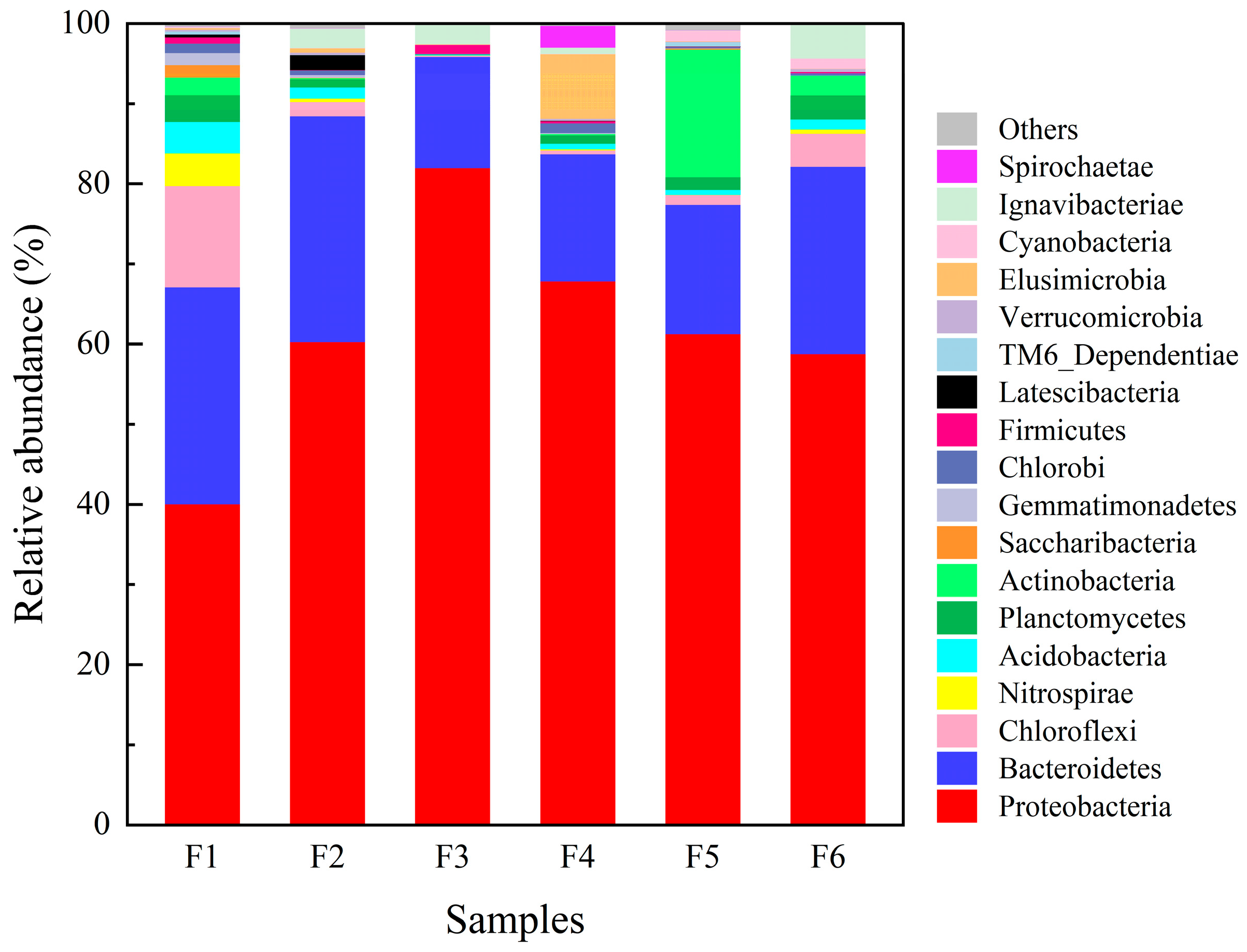

3.3.2. Bacterial Community Composition at the Phylum Level

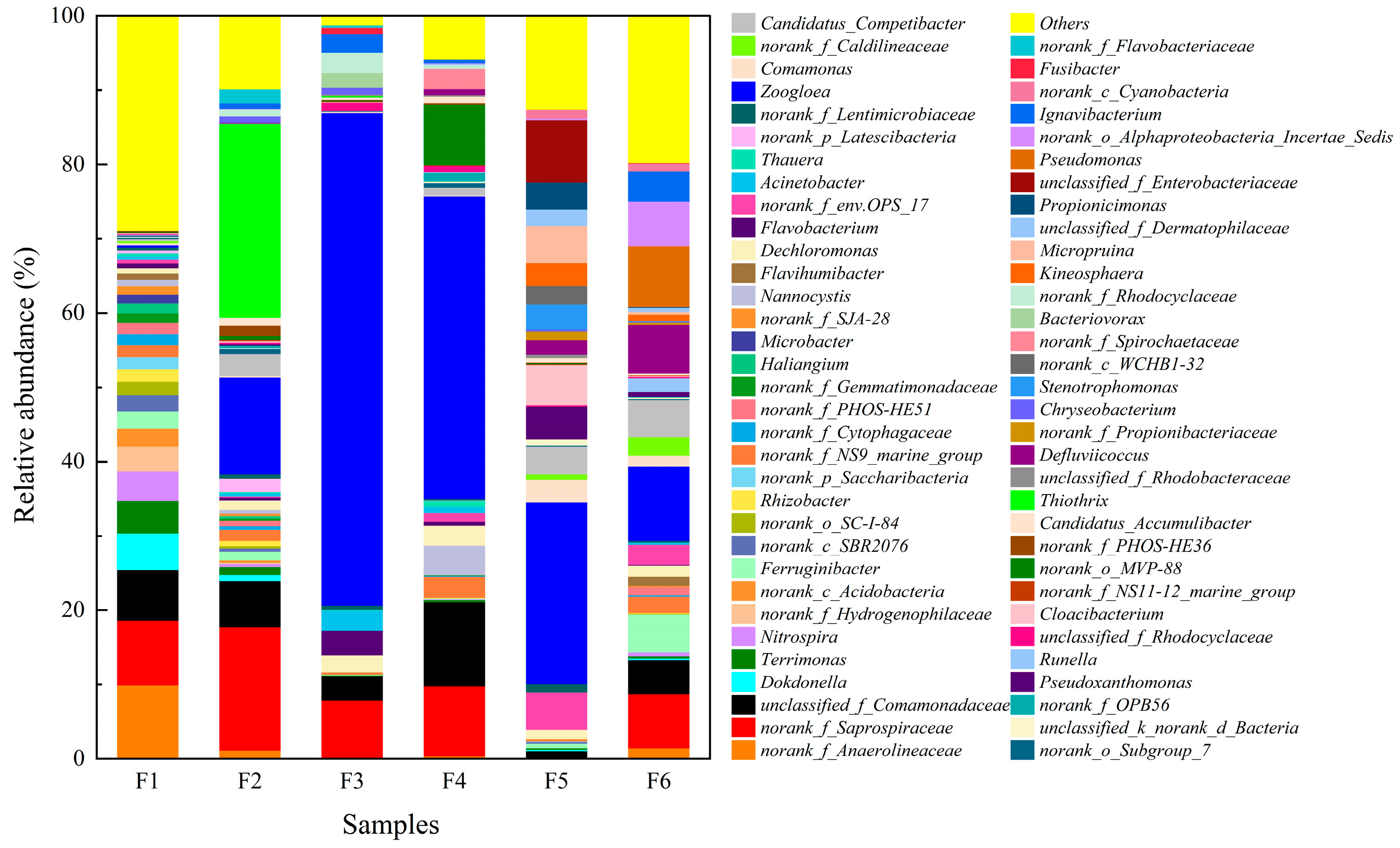

3.3.3. Bacterial Community Composition at the Genus Level

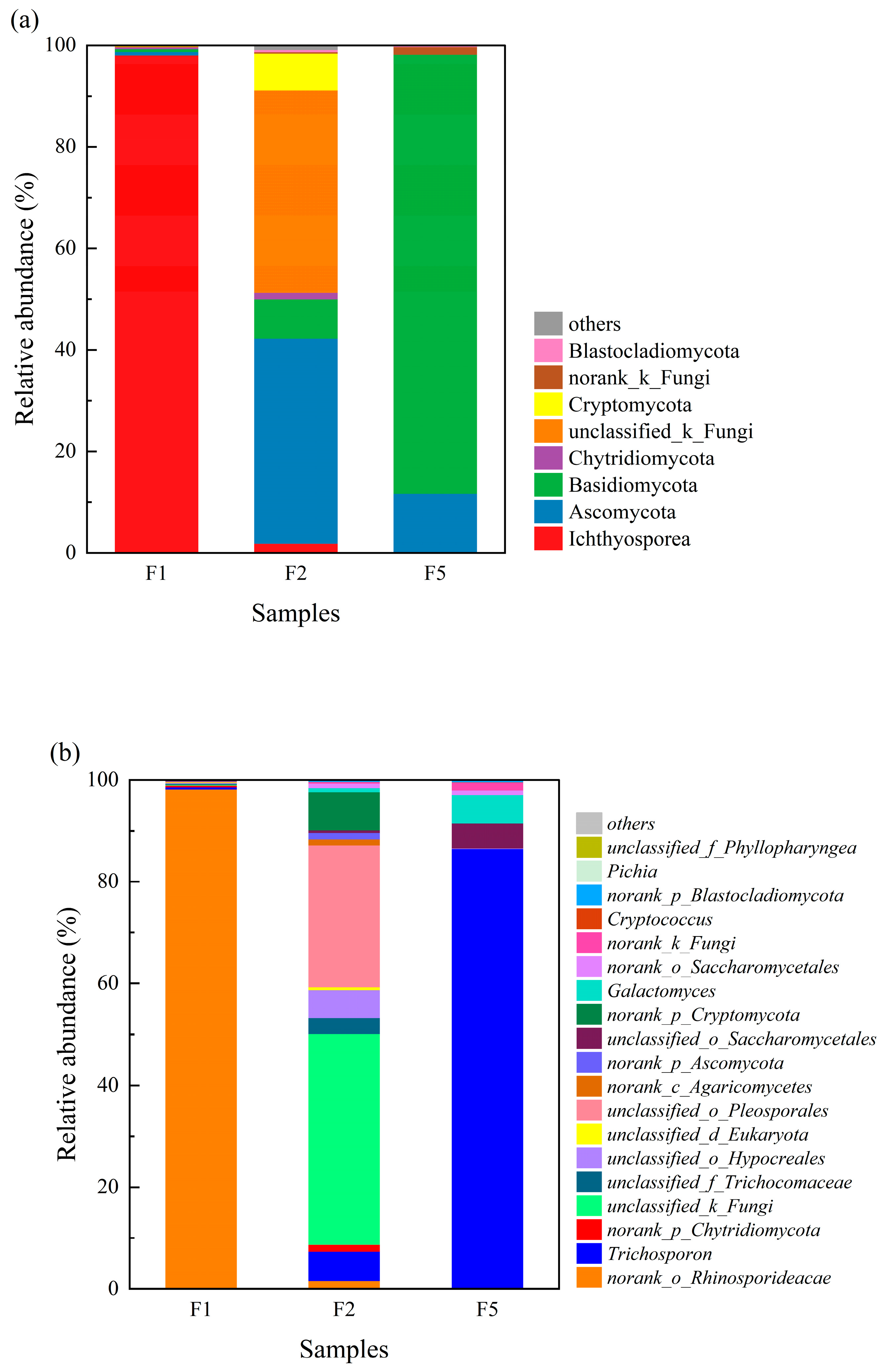

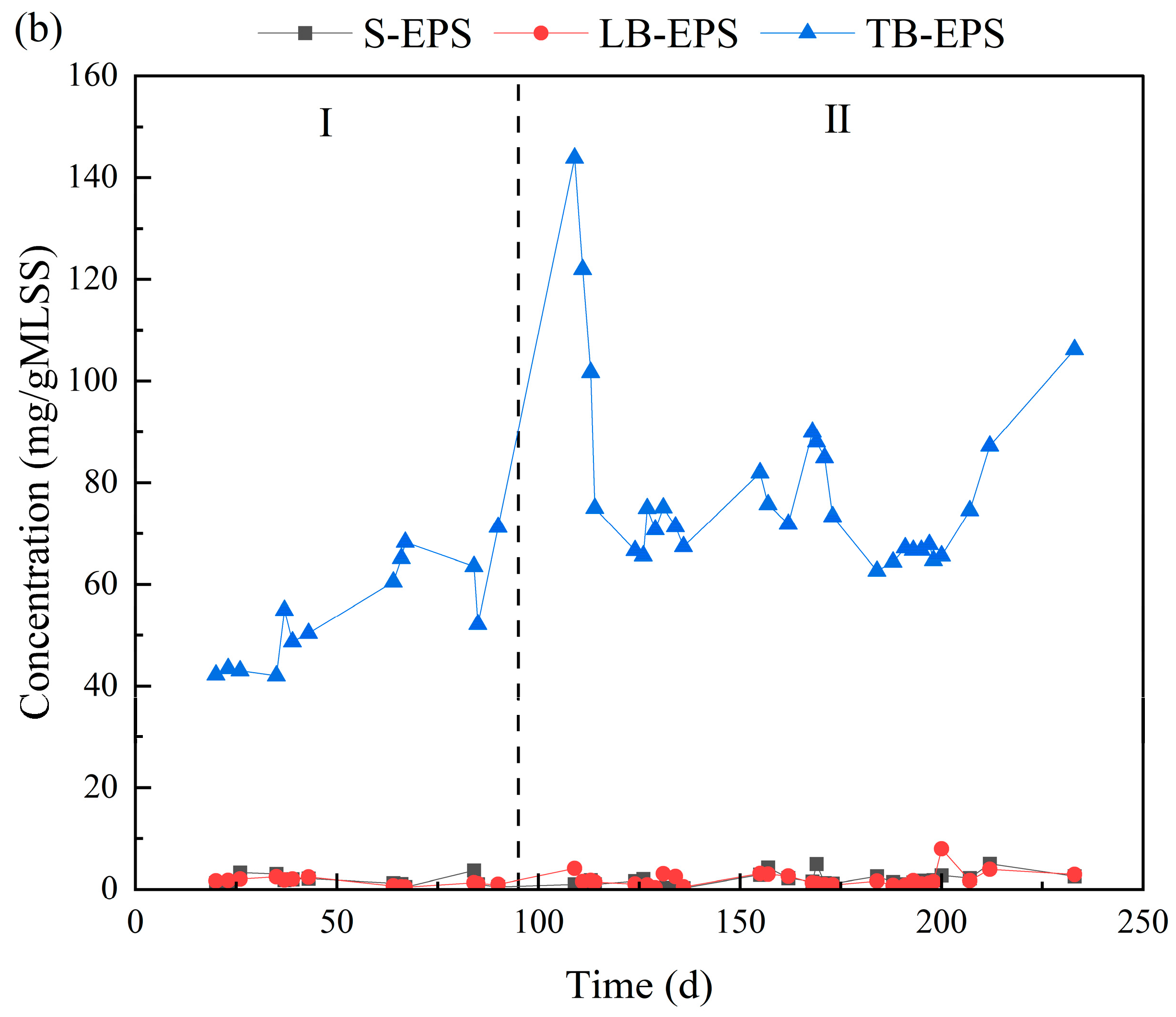

3.3.4. Fungal Community Composition at the Phylum and Genus Levels

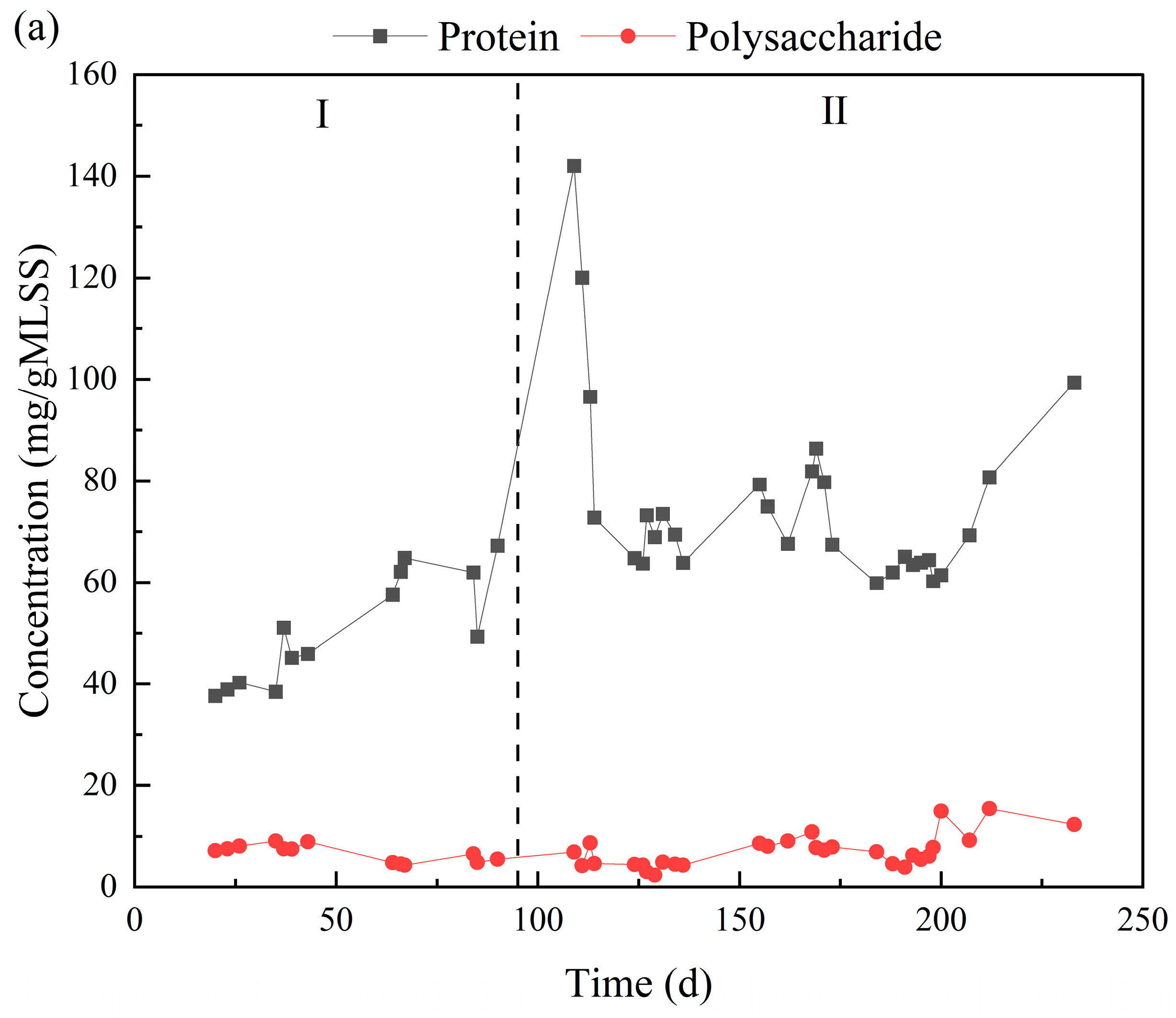

3.4. Changes in EPS Composition

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lv, T.; Wang, D.; Zheng, X.; Hui, J.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, Y. Study on specific strategies of controlling or preventing sludge bulking in S2EBPR process. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Tian, Z.; Yang, F.; Sun, D.; Liu, W.; Peng, Y. Absence of nitrogen and phosphorus in activated sludge: Impacts on flocculation characteristics and the microbial community. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 54, 103984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisterna-Osorio, P.; Calabran-Caceres, C.; Tiznado-Bustamante, G.; Bastias-Toro, N. Influent with particulate substrate, clean, innocuous and sustainable solution for bulking control and mitigation in activated sludge process. Water 2021, 13, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakos, V.; Gyarmati, B.; Csizmadia, P.; Till, S.; Vachoud, L.; Nagy Göde, P.; Tardy, G.M.; Szilágyi, A.; Jobbágy, A.; Wisniewski, C. Viscous and filamentous bulking in activated sludge: Rheological and hydrodynamic modelling based on experimental data. Water Res. 2022, 214, 118155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguel Suazo, K.; Dobbeleers, T.; Dries, J. Bacterial community and filamentous population of industrial wastewater treatment plants in Belgium. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Yue, Y.; Jiao, X.; Chi, Y.; Ding, Z.; Bai, Y. Effect of temperature on the relationship between quorum-sensing and sludge bulking. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 58, 104883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Bian, X.; Li, J.; Pei, Y.; Cui, Y.; Li, J. Non-filamentous bulking of activated sludge induced by graphene oxide: Insights from extracellular polymeric substances. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 399, 130574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, T.; Le Roes-Hill, M.; Hoosain, N.; Welz, P.J. Strategies for controlling filamentous bulking in activated sludge wastewater treatment plants: The old and the new. Water 2022, 14, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Yan, P.; Chen, Y.; Fang, F.; Guo, J. Non-filamentous sludge bulking induced by exopolysaccharide variation in structure and properties during aerobic granulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 876, 162786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Chen, C.; Fu, L.; Cui, B.; Zhou, D. Social network of filamentous Sphaerotilus during activated sludge bulking: Identifying the roles of signaling molecules and verifying a novel control strategy. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, S.; Tomei, M.C.; Nielsen, P.H.; Tandoi, V. “Microthrix parvicella”, a filamentous bacterium causing bulking and foaming in activated sludge systems: A review of current knowledge. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Fan, J.; Liu, R.; Zeng, G.; Chen, A.; Zou, Z. Removal of Cd(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) from aqueous solutions by live Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Environ. Technol. 2012, 33, 2653–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshniyat, R.; Asgari, G.; Ghahramani, E.; Daigger, G.T. Mechanisms of magneto-coagulation of the sludge in activated sludge bulking processes. Microb. Cell Fact. 2025, 24, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, R.; Sun, W.; Sun, Y. Advances in chemical conditioning of residual activated sludge in China. Water 2023, 15, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Hong, Y.; Chen, Y. Adding an anaerobic step can rapidly inhibit sludge bulking in SBR reactor. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.; Song, L.; Yin, Z.; Song, H.; Wang, Z.; Gao, W.; Xuan, L. Freeze–thaw combined with activated carbon improves electrochemical dewaterability of sludge: Analysis of sludge floc structure and dewatering mechanism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 20333–20346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Xiao, K.; Zhu, W.; Withanage, N.; Zhou, Y. Enhanced sludge solubilization and dewaterability by synergistic effects of nitrite and freezing. Water Res. 2018, 130, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G. Effects of freeze-thaw and chemical preconditioning on the consolidation properties and microstructure of landfill sludge. Water Res. 2021, 200, 117249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Su, X.; Sun, F.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, D.; Dong, F.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, Y. Freezing-activated oxidation with nitrite and H2O2 for efficient waste activated sludge solubilization and filterability. Water Res. 2025, 286, 124196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ye, P.; Fujii, M.; Kondo, G. The application of freeze-thaw cycle treatment on landfill sludge: Impact on physicochemical properties and physical-mechanical characteristics. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 468, 143106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.A.; Rahim, N.F.; Alias, J.; Ahmad, J.; Said, N.S.; Ramli, N.N.; Buhari, J.; Abdullah, S.R.; Othman, A.R.; Jusoh, H.H.; et al. A review on the roles of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) in wastewater treatment: Source, mechanism study, bioproducts, limitations, and future challenges. Water 2024, 16, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shan, Y.; Duan, P.; Wang, C. Steam explosion coupled with freeze-thaw cycles: An efficient and environmentally friendly method for deep dewatering of sewage sludge. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 51, 103462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, J. Effect of initial water content on the dewatering performance of freeze-thaw preconditioned landfill sludge. Environ. Res. 2023, 239, 117356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.; Gao, M.; Vuong, V.Q.; Quang, C.N.X. Improving sludge dewaterability through freeze-thaw pretreatment: Ice crystal morphology controls consolidation and rheological enhancement. Environ. Res. 2025, 286, 122758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Hu, A.; Ai, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, D. Changes in molecular structure of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) with temperature in relation to sludge macro-physical properties. Water Res. 2021, 201, 117316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhou, M.; Guan, S.; Ma, L.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sui, Y.; Jiao, X. Soil nitrogen-hydrolyzing enzyme activities respond differently to the freeze-thaw temperature and number of cycles. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.P.; Feng, W.C.; Chang, B.-V.; Chou, C.H.; Lee, D.J. Reduction of microbial density level in wastewater activated sludge via freezing and thawing. Water Res. 1999, 33, 3532–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Wang, C.; Abalos, D.; Guo, Y.; Pang, X.; Tan, C.; Zhou, Z. Seasonal response of soil microbial community structure and life history strategies to winter snow cover change in a temperate forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phalakornkule, C.; Nuchdang, S.; Khemkhao, M.; Mhuantong, W.; Wongwilaiwalin, S.; Tangphatsornruang, S.; Champreda, V.; Kitsuwan, J.; Vatanyoopaisarn, S. Effect of freeze–thaw process on physical properties, microbial activities and population structures of anaerobic sludge. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2017, 123, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Su, F.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Qian, J. Effects of freeze-thaw intensities on N2O release from subsurface wastewater infiltration system. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Yang, T. Experimental study of a solar-assisted ground-coupled heat pump system with solar seasonal thermal storage in severe cold areas. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 2104–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Yao, J.; Ma, H.; Peng, W.; Xia, X.; Chen, Y. A sludge bulking wastewater treatment plant with an oxidation ditch-denitrification filter in a cold region: Bacterial community composition and antibiotic resistance genes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 33767–33779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Peng, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, X.; Yuan, Z. Filamentous and non-filamentous bulking of activated sludge encountered under nutrients limitation or deficiency conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 255, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yan, P.; Guo, J.; Fang, F. Differences in responses of activated sludge to nutrients-poor wastewater: Function, stability, and microbial community. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 457, 141247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, D.; Liu, L.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y. A review of the role of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in wastewater treatment systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, C.; Görner, T.; Lartiges, B.S.; Abdelouhab, S.; de Donato, P. Characterization of activated sludge exopolymers from various origins: A combined size-exclusion chromatography and infrared microscopy study. Water Res. 2005, 39, 3044–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, O.F. Role of exopolymeric protein on the settleability of nitrifying sludges. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 94, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Peng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, M.; Wang, S. Illumina MiSeq sequencing reveals the key microorganisms involved in partial nitritation followed by simultaneous sludge fermentation, denitrification and anammox process. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 207, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousk, J.; Bååth, E.; Brookes, P.C.; Lauber, C.L.; Lozupone, C.; Caporaso, J.G.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J. 2010, 4, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB 18918-2002; Discharge Standard of Pollutants for Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants. Ministry of Environmental Protection of China: Beijing, China, 2002. (In Chinese)

- Rosselló-Mora, R.A.; Wagner, M.; Amann, R.; Schleifer, K.H. The abundance of Zoogloea ramigera in sewage treatment plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Castillo, A.M.; Garcia-Barrera, A.A.; Garrido-Hernandez, A.; Martinez-Valdez, F.J.; Cruz-Romero, M.S.; Quezada-Cruz, M. Ciliated peritrichous protozoa in a tezontle-packed sequencing batch reactor as potential indicators of water quality. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2022, 71, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajdak-Stós, A.; Kocerba-Soroka, W.; Fyda, J.; Sobczyk, M.; Fiałkowska, E. Foam-forming bacteria in activated sludge effectively reduced by rotifers in laboratory- and real-scale wastewater treatment plant experiments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 13004–13011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.T.; McDougald, D.; Klebensberger, J.; Al Qarni, B.; Barraud, N.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S.; Schleheck, D. Glucose starvation-induced dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms is cAMP and energy dependent. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Hou, R.; Yang, P.; Qian, S.; Feng, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, F.; Yuan, R.; Chen, H.; Zhou, B. Application of external carbon source in heterotrophic denitrification of domestic sewage: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 153061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Gao, C.; Hu, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Peng, Y. Effects of oleic acid on activated sludge systems: Performance, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and microbial communities. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Rui, D.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X.; Ye, L. Large-scale comparative analysis reveals different bacterial community structures in full- and lab-scale wastewater treatment bioreactors. Water Res. 2023, 242, 120222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Yao, J.; Liu, W.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Liang, M.; Ma, H.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y. Comparison of bacterial communities and antibiotic resistance genes in oxidation ditches and membrane bioreactors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, W.; Liu, R.; Li, Q.; Li, B.; Wang, S.; Song, C.; Qiao, C.; Mulchandani, A. Phylogenetic diversity and metabolic potential of activated sludge microbial communities in full-scale wastewater treatment plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7408–7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Zhao, J.; Lu, Z.; Wang, M.; Guo, C.; Song, X.; Guo, X.; Cai, M.; Wu, Z. The effects of different temperature conditions on sludge characteristics and microbial communities of nitritation denitrification. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 50, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speirs, L.B.M.; Rice, D.T.F.; Petrovski, S.; Seviour, R.J. The phylogeny, biodiversity, and ecology of the Chloroflexi in activated sludge. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Zhou, J.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Hu, X.; Peng, Y. Characteristics of microbial communities and extracellular polymeric substances during Thiothrix-induced sludge bulking process. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpfer, P.; Weltin, D.; Hoffmeister, D.; Dott, W. Growth requirements of filamentous bacteria isolated from bulking and scumming sludge. Water Res. 1995, 29, 1585–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yu, Z.; Qi, R.; Zhang, H. Detailed comparison of bacterial communities during seasonal sludge bulking in a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 2016, 105, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Fei, X.; Chi, Y.; Cao, L. Impact of the acetate/oleic acid ratio on the performance, quorum sensing, and microbial community of sequencing batch reactor system. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 296, 122279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Martinez, A.; Muñoz-Palazon, B.; Maza-Márquez, P.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, A.; Gonzalez-Lopez, J.; Vahala, R. Performance and microbial community structure of a polar Arctic Circle aerobic granular sludge system operating at low temperature. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 256, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; He, Y.; Wang, W.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.X.; Wang, D. Temporal differentiation in the adaptation of functional bacteria to low-temperature stress in partial denitrification and anammox system. Environ. Res. 2023, 244, 117933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Sun, Z.; Li, T.; Li, B.; Wang, J. Investigation of the cold-adapted membrane-aerated biofilm reactor: Performance analysis and community dynamics characterization. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Liu, Y.; Feng, K.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Jin, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Yin, H.; Xu, M.; et al. The divergence between fungal and bacterial communities in seasonal and spatial variations of wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628–629, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabardina, V.; Dharamshi, J.E.; Ara, P.S.; Antó, M.; Bascón, F.J.; Suga, H.; Marshall, W.; Scazzocchio, C.; Casacuberta, E.; Ruiz-Trillo, I. Ichthyosporea: A window into the origin of animals. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maza-Márquez, P.; Vilchez-Vargas, R.; Kerckhof, F.M.; Aranda, E.; González-López, J.; Rodelas, B. Community structure, population dynamics and diversity of fungi in a full-scale membrane bioreactor (MBR) for urban wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2016, 105, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouari, R.; Leonard, M.; Bouali, M.; Guermazi, S.; Rahli, N.; Zrafi, I.; Morin, L.; Sghir, A. Eukaryotic molecular diversity at different steps of the wastewater treatment plant process reveals more phylogenetic novel lineages. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 33, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.; Lu, X.; Chen, C.; Huo, Y.; Zhou, D. Transboundary intercellular communications between Penicillium and bacterial communities during sludge bulking: Inspirations on quenching fungal dominance. Water Res. 2022, 221, 118829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwugwa, V.H.; Oyetibo, G.O.; Amund, O.O. Taxonomic profiling of bacteria and fungi in freshwater sewer receiving hospital wastewater. Environ. Res. 2021, 192, 110319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yao, J.; Wang, X.; Hong, Y.; Chen, Y. The microbial community in filamentous bulking sludge with the ultra-low sludge loading and long sludge retention time in oxidation ditch. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Sun, J.; Han, H. Effect of dissolved oxygen changes on activated sludge fungal bulking during lab-scale treatment of acidic industrial wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 8928–8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovski, S.; Tillett, D.; Seviour, R.J. Isolation and complete genome sequence of a bacteriophage lysing Tetrasphaera jenkinsii, a filamentous bacteria responsible for bulking in activated sludge. Virus Genes 2012, 45, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Tian, C.; Ma, X.; Ji, L.; Zhao, B.; Danish, M.E.; Gao, F.; Yang, Z. Seasonal temperature effects on EPS composition and sludge settling performance in full-scale wastewater treatment plant: Mechanisms and mitigation strategies. Fermentation 2025, 11, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.; Yu, H.; Li, X. Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) of microbial aggregates in biological wastewater treatment systems: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, C.; Meng, F.; Chen, G. Spectroscopic characterization of extracellular polymeric substances from a mixed culture dominated by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Water Res. 2015, 68, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kong, F.; Fu, Y.; Si, C.; Fatehi, P. Improvements on activated sludge settling and flocculation using biomass-based fly ash as activator. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuvaraj, M.; Fein, J.; Liss, S.N. Protein and polysaccharide content of tightly and loosely bound extracellular polymeric substances and the development of a granular activated sludge floc. Water Res. 2015, 82, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z. Role of extracellular polymeric substance in determining the high aggregation ability of anammox sludge. Water Res. 2015, 75, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, A.; Quintelas, C.; Ferreira, E.C.; Mesquita, D.P. The role of extracellular polymeric substances in micropollutant removal. Front. Chem. Eng. 2022, 4, 778469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Deng, D.; Li, R.; Guo, C.; Ma, J.; Chen, M. Investigation of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in four types of sludge: Factors influencing EPS properties and sludge granulation. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 40, 101924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Composition | Weighing Dosage (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| FeSO4·7H2O | 20 |

| Na2MoO4·2H2O | 10 |

| CaCl2·6H2O | 50 |

| CuSO4·5H2O | 50 |

| H3BO3 | 50 |

| Sample | Days of Operation (d) | SV (%) | SVI (mL·g−1) | MLSS (mg·L−1) | Carbon Source | DO (mg·L−1) | Water Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 1 | 26 | 99 | 5652 | sodium acetate | - | 19 |

| F2 | 69 | 91 | 228 | 3984 | sodium acetate | 4.2 | 19 |

| F3 | 110 | 35 | 169 | 2070 | sodium acetate | 5.7 | 18 |

| F4 | 150 | 81 | 260 | 3109 | sodium acetate | 4.2 | 21 |

| F5 | 197 | 35 | 78 | 4079 | glucose | 2.4 | 22 |

| F6 | 222 | 30 | 76 | 2639 | glucose | 3.5 | 23 |

| Sample | Sequences | OUTs | Coverage | Chao | Shannon | Heip |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 31,717 | 565 | 0.997 | 604 | 4.988 | 0.258 |

| F2 | 42,819 | 517 | 0.996 | 537 | 3.762 | 0.083 |

| F3 | 42,006 | 225 | 0.996 | 315 | 1.783 | 0.022 |

| F4 | 41,104 | 355 | 0.996 | 418 | 2.867 | 0.047 |

| F5 | 42,377 | 331 | 0.997 | 396 | 3.581 | 0.105 |

| F6 | 42,889 | 356 | 0.997 | 379 | 4.330 | 0.213 |

| Scheme | Sequences | OUTs | Coverage | Chao | Shannon | Heip |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 31,238 | 44 | 0.999 | 44 | 0.161 | 0.004 |

| F2 | 30,958 | 52 | 0.999 | 52 | 2.023 | 0.131 |

| F5 | 39,396 | 16 | 0.999 | 17 | 0.619 | 0.057 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Yao, J.; Yan, H.; Xu, S. Instantaneous Relief and Persistent Control of Sludge Bulking: Changes in Bacterial Flora Due to Freeze–Thaw and Carbon Source Conversion. Water 2025, 17, 3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243553

Li H, Yao J, Yan H, Xu S. Instantaneous Relief and Persistent Control of Sludge Bulking: Changes in Bacterial Flora Due to Freeze–Thaw and Carbon Source Conversion. Water. 2025; 17(24):3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243553

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Haoran, Junqin Yao, Hui Yan, and Shuang Xu. 2025. "Instantaneous Relief and Persistent Control of Sludge Bulking: Changes in Bacterial Flora Due to Freeze–Thaw and Carbon Source Conversion" Water 17, no. 24: 3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243553

APA StyleLi, H., Yao, J., Yan, H., & Xu, S. (2025). Instantaneous Relief and Persistent Control of Sludge Bulking: Changes in Bacterial Flora Due to Freeze–Thaw and Carbon Source Conversion. Water, 17(24), 3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243553