Abstract

The risk of urban flooding has escalated with increasing rainfall intensity and the expansion of impervious surfaces. While commercial models such as XP-SWMM provide reliable hydraulic analyses, their closed-source structure limits transparency and integration with external tools. In contrast, the Grid-Based Urban Drainage System Analysis Model (GUDS), developed on the Weighted Cellular Automata 2D (WCA2D) framework, offers greater flexibility for process verification and coupling with platforms such as GIS and spreadsheets. This study presents a comparative assessment of numerical stability and velocity estimation schemes between XP-SWMM and GUDS. Moving beyond previous validation-focused studies, it quantitatively examines how algorithmic formulations—particularly in flow velocity computation and numerical treatment—affect inundation propagation and model stability under varying topographic conditions. Results demonstrate that XP-SWMM yields higher analytical precision but is prone to numerical instability on steep slopes, whereas GUDS maintains stable simulations due to its simplified water-level-difference approach, albeit with reduced responsiveness to rapidly changing flows. The differences in maximum inundation depth, inundation area, and propagation speed were relatively minor—approximately 11.6%, 10.7%, and 9.2% on average, respectively. This work provides a novel quantitative perspective on the trade-offs between precision and stability in urban flood modeling, highlighting GUDS’s robustness and practical applicability as an open and extensible alternative to conventional equation-based models.

1. Introduction

Climate change has led to increasing rainfall frequency and intensity, resulting in more frequent occurrences of localized heavy rainfall and flash floods. Consequently, urban flooding tends to expand rapidly within a short period. Urban catchments, in particular, are characterized by a high proportion of impervious surfaces and complex drainage systems, which increase the potential for rapid flood propagation and damage. Therefore, the need for accurate and computationally stable two-dimensional inundation models that can simulate a wide range of rainfall scenarios, including extreme events, has been continuously emphasized as a key research topic in urban flood management. In particular, balancing numerical precision and stability has become a critical challenge in developing reliable inundation analysis tools.

In practice, XP-SWMM, a commercial hydrodynamic model, has been widely used for urban drainage and inundation analysis [1]. However, due to its closed structure, it faces limitations in terms of reproducibility and interoperability with external analysis tools. As an alternative, recent studies have actively explored inundation models based on the Cellular Automata (CA) technique. CA divides space into grids, and each grid cell is updated at each time step based on interactions with neighboring cells. This approach has been applied as a simple rule-based flow propagation tool for inundation analysis.

Jamali et al. proposed a CA-based rapid inundation model that approximates flood propagation using water-level-difference transition rules without solving the Shallow Water Equations (SWEs) [2]. This model achieves speedy computation, making it suitable for real-time and large-scale simulations, but it has limitations in reproducing detailed hydraulic structures and flow dynamics. Similarly, the CADDIES-CAFLOOD model is fast and applicable to real terrains due to its simple rules. Still, its limited structural representation makes it more appropriate for flood warning and response support than for detailed design review [3]. In a city-scale simulation for Jinan, the computational efficiency and real-time forecasting potential of CA-based approaches were emphasized [4].

To enhance accuracy, Chang et al. developed SWFCA, which integrates SWE components into CA transition rules to improve the reproduction of inundation depth and morphology [5]. However, this increases computational costs, potentially reducing scalability for scenario analyses. Another approach, Hybrid CA + DEM, accelerates time propagation using CA and then refines the final distribution through DEM (Digital Elevation Model)-based terrain correction, improving accuracy compared to pure CA models. However, excessive correction can compromise model consistency, requiring a balance between accuracy and stability [6]. In a similar vein, Wijaya et al. proposed a Hybrid Inundation Model (HIM) that couples a CA-based zero-inertia solver with DEM-based refinement and a 1D drainage module, demonstrating that near-real-time urban flood simulations can be achieved while maintaining acceptable accuracy for urban flood early-warning applications [7]. More recently, Yu et al. developed a coupled river–overland (1D–2D) model that links a CA-based urban inundation solver (2D-OFM-CA) with a one-dimensional river flow model (1D-RFM) for fluvial flooding assessment, achieving accuracy comparable to the widely used HEC-RAS model while reducing computational time by approximately 40–50% [8]. Do Lago et al. proposed a CGAN (Conditional Generative Adversarial Network)-based model that enables rapid flood prediction with high accuracy when sufficient high-quality training data are available [9]. Nevertheless, this approach has inherent limitations in physical consistency, interpretability, and dependence on the quality and applicability of training datasets.

Beyond CA-based approaches, physically based two-dimensional hydrodynamic models such as HEC-RAS 2D, LISFLOOD-FP, TUFLOW-FV, and Iber-based solvers have undergone significant advancements to improve numerical stability, hydrodynamic fidelity, and computational scalability in urban flood modeling. Recent studies have demonstrated the applicability of HEC-RAS 2D to real-time pluvial flood forecasting through watershed-scale modeling frameworks and rapid inundation estimation [10,11,12]. LISFLOOD-FP has recently been extended to version 8.1, which introduces GPU-accelerated solvers that substantially reduce runtimes for fluvial and pluvial flood simulations [13]. Likewise, Iber+ and IberSWMM+ have enhanced dual-drainage coupling and high-performance computing capabilities to efficiently simulate pluvial flooding across complex urban catchments [14,15].

While the above advancements in physically based hydrodynamic models highlight their strengths in accurately resolving complex flow processes, they often involve substantial computational costs and rely on numerically intensive solvers. Consequently, such models may be less suited for applications requiring rapid scenario screening, real-time forecasting, or large-ensemble simulations. In contrast, CA-based models—including the WCA2D framework implemented in GUDS (Grid-Based Urban Drainage System Analysis Model)—offer a complementary modeling paradigm characterized by algorithmic transparency, computational efficiency, and ease of integration with urban drainage networks. Thus, the purpose of the present study is not to position CA as a replacement for fully dynamic hydrodynamic models but rather to quantitatively assess its performance relative to XP-SWMM within the context of urban inundation analysis. This comparative evaluation directly addresses the practical need for selecting appropriate modeling tools depending on the trade-offs between numerical stability, computational cost, and hydrodynamic detail.

Guidolin et al. introduced the Weighted Cellular Automata 2D (WCA2D) method, which incorporates not only water-level differences but also storage capacity and local gradients into the weighting scheme and uses Manning’s formula and critical flow-based upper limits for discharge, thereby ensuring numerical stability and efficiency [16]. Although its ability to capture dynamic hydraulic changes is limited, the WCA2D method provides physically consistent inundation results and, being open-source, offers advantages in process analysis and verification. However, most existing studies employing WCA2D-based or similar CA approaches have primarily focused on model validation or application testing, rather than quantitatively evaluating their algorithmic behavior or numerical performance compared with equation-based models.

This study builds upon the urban inundation analysis model GUDS developed by Yu et al. [17], which consists of three modules: surface runoff analysis, pipe flow conveyance, and inundation analysis. The surface runoff module applies the NRCS-CN method and Clark unit hydrograph, while the pipe flow conveyance module is coupled with EPA-SWMM. The inundation analysis module employs the WCA2D technique, with a fixed time step synchronized with the other modules. Yu et al. demonstrated the practical applicability of GUDS through simplified parameters and showed that differences in maximum inundation depth and inundation area compared with XP-SWMM were generally within 10% [18]. They also identified differences between the linear velocity distribution of GUDS and the trapezoidal distribution of XP-SWMM under increasing slopes.

However, the two models differ fundamentally in their governing equations for estimating flow velocity and discharge. WCA2D simplifies momentum calculations by applying weighted water-level differences and discharge limitations, thereby improving numerical efficiency. XP-SWMM, on the other hand, offers greater analytical precision but can exhibit numerical instability depending on input parameters such as time steps and grid resolution. These differences can result in variations in inundation propagation speed and pathways even under identical input conditions.

The objectives of this study are to: (i) clearly describe the computational structure and hydraulic formulation of GUDS; (ii) quantitatively compare the numerical stability and velocity estimation schemes of GUDS and the commercial XP-SWMM model; and (iii) evaluate their effects on inundation propagation speed, flow paths, maximum depth, and inundation area under controlled topographic conditions. Unlike previous studies that mainly validated GUDS performance, this study focuses on algorithm-level quantitative comparison to elucidate how analytical formulations influence numerical stability and flow dynamics. The findings aim to provide methodological insights into balancing precision and stability in urban inundation modeling.

2. Comparison of Flood Analysis Methods

This study adopts a quantitative comparative framework to evaluate the analytical differences between XP-SWMM and GUDS. The comparison focuses on two key aspects: velocity estimation schemes, which determine how each model calculates flow transfer between computational units, and numerical stability, which affects the reliability of results under varying topographic and boundary conditions.

Moreover, XP-SWMM (via TUFLOW) employs a staggered arrangement in which the u- and v-velocity components are solved on cell faces, while water level and depth are defined at cell centers [19]. In contrast, GUDS uses a fully cell-centered scheme. This difference in variable placement can introduce small spatial misalignments when face-based fluxes are mapped to cell-centered outputs—especially near boundaries or sharp slopes—and thus explains part of the larger discrepancies observed in peak depth and propagation speed.

2.1. Grid-Based Urban Drainage System Analysis Model

In this study, the inundation analysis methods and results of the commercial XP-SWMM model and the open-source GUDS model were compared and examined. GUDS consists of three modules: a surface runoff analysis module, a pipe flow conveyance module, and an inundation analysis module. The surface runoff and inundation analysis modules operate on a grid-based computational framework.

The surface runoff module estimates excess rainfall and overland flow using the NRCS-CN method and the Clark unit hydrograph method, following flood estimation guidelines, and calculates flow directions using the D8 algorithm [20,21]. The pipe flow conveyance module is based on EPA-SWMM, a one-dimensional hydraulic analysis model developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. In this study, the PySWMM API was utilized within a Python 3.1.3 environment to implement this module [22].

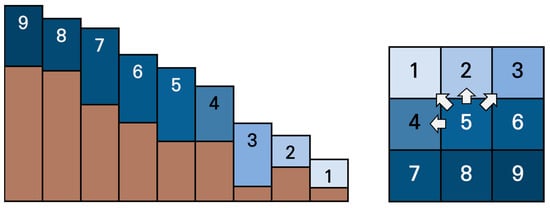

The inundation analysis module, which is the main focus of this study, employs the Weighted Cellular Automata 2D (WCA2D) technique based on the Cellular Automata (CA) method [16]. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of the CA method, in which the spatial variation of water levels is represented by color shading. The cell structure on the right applies the same shading scheme, and arrows indicate the possible directions of flow transfer from the central cell (Cell 5) toward neighboring cells based on the relative water levels.

Figure 1.

Concept of the CA Method (Yu et al., 2024 [17]).

The inundation analysis module of GUDS applies the Weighted Cellular Automata 2D (WCA2D) technique, a method based on the Cellular Automata (CA) approach. This technique uses a flow transfer mechanism that simulates interactions between adjacent grid cells. The proportion of flow transferred to neighboring cells is determined using weights based on the available storage capacity of each adjacent cell.

In addition, flow velocities are limited by applying Manning’s equation and critical flow conditions. The model adopts simplified rules that simultaneously compute flow velocities and discharges at each time step, enabling efficient parallelization through simple calculations. In GUDS, the time step for the two-dimensional inundation analysis module is fixed and synchronized with that of the one-dimensional analysis module to ensure consistency.

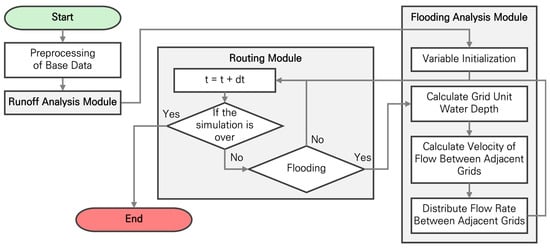

Figure 2 illustrates the interconnections between the modules of GUDS. The inundation analysis module is divided into four main steps. Equations (1)–(11) summarize the procedures for flow velocity estimation and flow distribution in the WCA2D technique proposed by Guidolin et al. [16].

Figure 2.

Workflow for the Routing Module and Flooding Analysis Module (adapted from Yu et al., 2024 [17]).

In the first step, grid-based information is initialized using input data, including ground elevation and rainfall.

In the second step, the inundation depth for each grid cell is calculated according to the rainfall inflow at each time step, following Equations (1)–(5). Here, denotes the number of adjacent cells; represents the index of the neighboring cells; (m) is the water level of the central cell; (m) is the water level of the adjacent cell; and (m) is the water level difference between the two cells. The critical water level difference (m) is set to 0.001 m in this study. (m2) represents the area of the adjacent cell. (m3) is the permissible flow volume transferable between the central and adjacent cells, among which (m3) and (m3) are the minimum and maximum permissible flow volumes, respectively, and (m3) is the total permissible flow volume.

In the third step, the flow velocity between adjacent grid cells is calculated. This is determined using Equations (6) and (7), by selecting the smaller value between the critical velocity and the Manning velocity. Here, (m/s) represents the critical velocity between grid cells, (m/s2) is the gravitational acceleration, and (m) is the water depth of the corresponding grid cell. The Manning velocity (m/s) is computed using Manning’s equation, which incorporates the roughness coefficient , the hydraulic radius (m), and the hydraulic gradient .

In the fourth step, the relative weights between adjacent cells are calculated using Equations (8)–(11), and the distributed flow is subsequently determined. Here, represents the weight of the -th adjacent cell, and denotes the maximum weight among the adjacent cells. (m/s) is the flow velocity of the -th cell, (m) is the water depth of the central cell, (m) is the water level difference between the central cell and the -th adjacent cell, and (m) is the distance between the centers of the two cells. (m3) is the maximum transferable flow to the cell, (s) is the time step, (m) is the side length of the cell, and (m2) is the area of the central cell. The weight of the cell is then applied to determine the distributed flow volume (m3), which represents the flow transferred from the central cell to the -th adjacent cell during each time step. This calculation considers the storage volume determined by the central cell’s depth and area, the maximum storage capacity of the -th cell, and the permissible flow from the previous time step, thereby preventing excessive flow estimation and ensuring the numerical stability of the model.

2.2. XP-SWMM

XP-SWMM is a widely used commercial model for urban inundation analysis. Its hydraulic foundation is based on the continuity and momentum equations, which are used to calculate flow discharge and velocity. The continuity equation represents the balance between changes in water depth and inflow–outflow, while the momentum equation accounts for velocity variations caused by advection, pressure (water surface gradient), bed slope, friction, and external forces. Because the model includes inertial terms, it can simulate rapidly varying flows and wave propagation phenomena. However, as XP-SWMM is a commercial model, its internal algorithms are not publicly disclosed, and simulation results may become unstable depending on the time step and grid resolution. Due to these characteristics, there are limitations in analyzing the calculation processes and extending the model outputs.

Equations (12) and (13) represent the continuity and momentum equations, respectively, where (m) is the water depth, , (m/s) are the flow velocities in the - and -directions, (m) is the bed elevation, is the friction term, and is the external force term.

XP-SWMM determines flow velocity by numerically solving the continuity and momentum equations of the two-dimensional shallow water equations. In contrast, the WCA2D technique distributes flow between adjacent cells based on water level differences, while limiting the allowable velocity at each cell boundary to the smaller value between the critical and Manning velocities. Due to these differences in analytical approaches, discrepancies were observed in the temporal and spatial distribution of the simulation results.

3. Comparison of Inundation Analysis Characteristics Between Models

3.1. Configuration of Analysis Cases

The comparison between GUDS and XP-SWMM focused on flow velocity and inundation depth. For both models, a single node was placed within each catchment under the assumption of a constant inflow rate, and the node inflow was set identically in the two models as 0.1 m3/s for one hour. The catchments were discretized into grid cells of 10 m × 10 m, resulting in a total of 2704 cells and a corresponding catchment area of 27.04 ha, and two simplified and idealized topographic types were considered: inclined and funnel shapes.

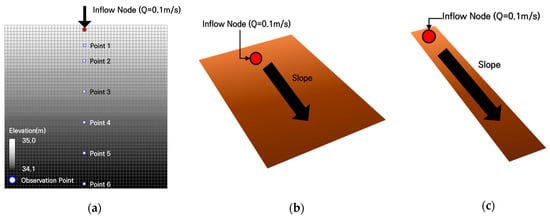

The inclined type was divided into two cases to analyze flood propagation. Case I (Inclined Type), shown in Figure 3, was designed to examine the propagation of inundation. Case II (Single Grid of Inclined Type) consisted of a single row of grids in the longitudinal direction on an inclined surface, allowing for a comparison of flow behavior in the absence of lateral spreading.

Figure 3.

The simplified watershed in Case I (Inclined Type) and Case II (Single Grid of Inclined Type): (a) Grid layout and observation points; (b) Case I (Inclined Type); (c) Case II (Single Grid of Inclined Type).

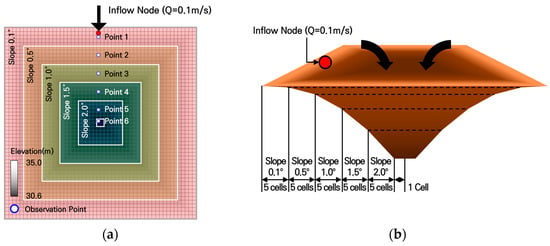

Case III (Funnel Type), illustrated in Figure 4, was constructed by dividing the slope into 0.1°, 0.5°, 1.0°, 1.5°, and 2.0°, with five grid cells assigned to each slope range. The slope becomes steeper toward the center of the catchment, while the center itself remains flat. This configuration was designed to reproduce inundation patterns typically observed in local depressions within urban catchments, where water tends to accumulate.

Figure 4.

The simplified watershed in Case Ⅲ (Funnel Type): (a) Grid layout and observation points; (b) Case Ⅲ (Funnel Type).

The classification of each case is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Slope conditions by case.

3.2. Case I (Inclined Type)

Case I (Inclined Type) represents a uniformly sloped surface and was designed to examine not only the maximum inundation depth and inundation area but also the propagation path and velocity of flooding.

3.2.1. Case I-1 (Inclined Type)

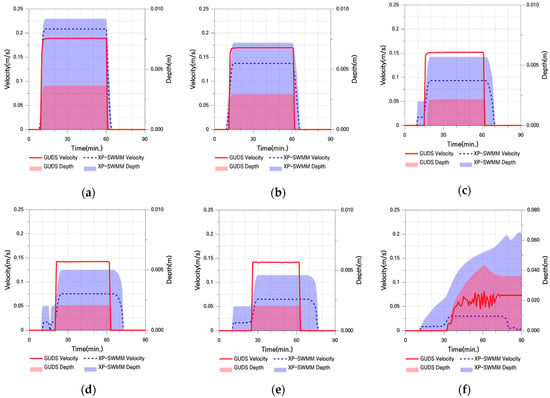

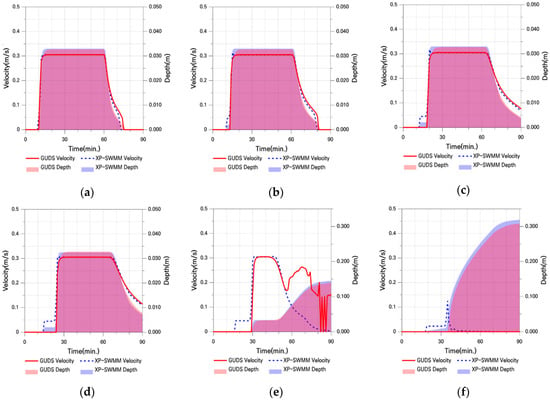

Case I-1 (Inclined Type) applies a slope of 0.1°. The maximum inundation depth and inundation area at each point are summarized in Table 2. Table 3 presents the extent of flood propagation in the X-direction for each point in terms of the number of cells, while Figure 5 shows the velocity and water depth at each point. Time-series inundation maps generated by GUDS and XP-SWMM are presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Table 2.

Maximum Velocity and Maximum Water Depth in Case Ⅰ-1.

Table 3.

Inundation Propagation in Case I-1.

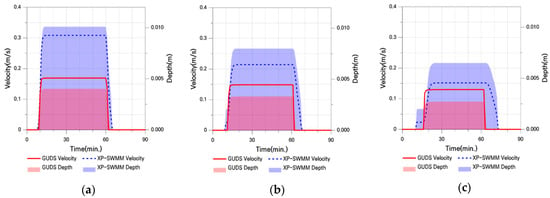

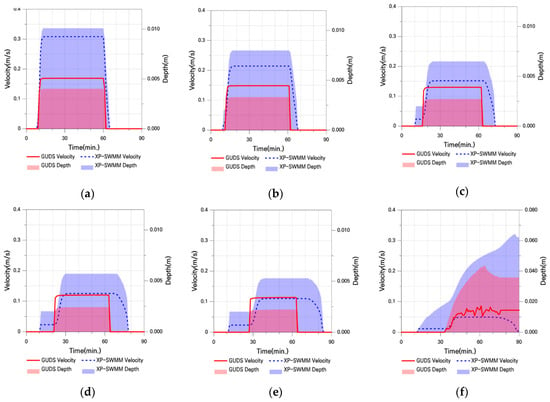

Figure 5.

Flow Velocity and Water Depth in Case I-1: (a) Point 1; (b) Point 2; (c) Point 3; (d) Point 4; (e) Point 5; (f) Point 6.

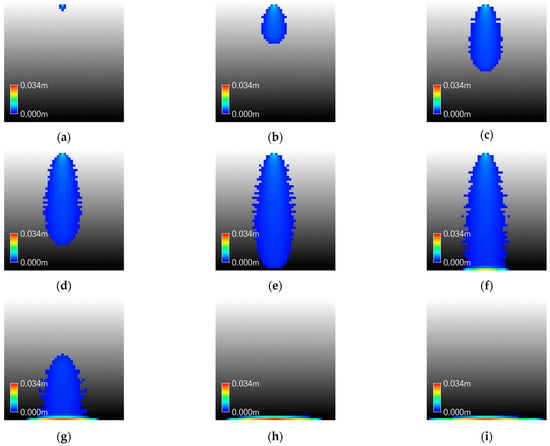

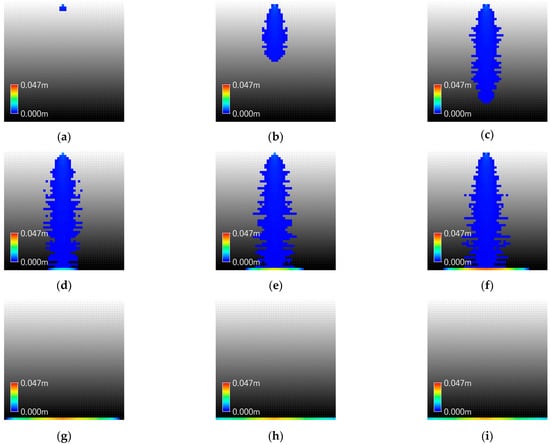

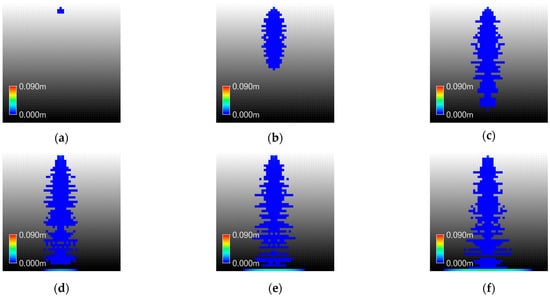

Figure 6.

Inundation Map of GUDS in Case I-1: (a) 00:10; (b) 00:20; (c) 00:30; (d) 00:40; (e) 00:50; (f) 01:00; (g) 01:10; (h) 01:20; (i) 01:30.

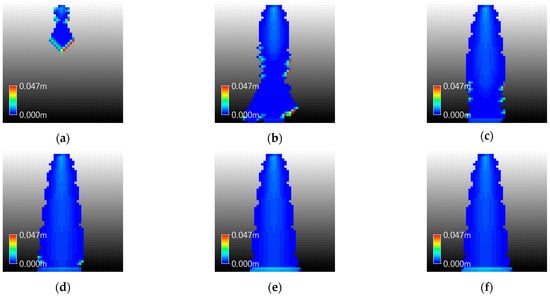

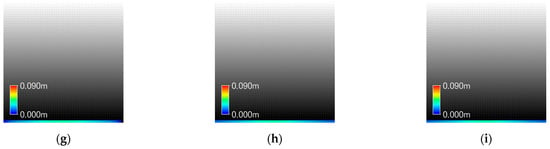

Figure 7.

Inundation Map of XP-SWMM in Case I-1: (a) 00:10; (b) 00:20; (c) 00:30; (d) 00:40; (e) 00:50; (f) 01:00; (g) 01:10; (h) 01:20; (i) 01:30.

The initial flow velocity calculated by GUDS was greater than that of XP-SWMM, and for both models, velocity decreased with increasing distance from the overflow point. At the downstream end of the catchment, XP-SWMM produced larger water depths. Under mild slope conditions, XP-SWMM, based on the shallow water equations, initially exhibited shallow and fast flows, followed by a rapid increase in water depth and velocity due to pressure buildup. In contrast, GUDS calculated relatively high velocities even under shallow water conditions due to its water level difference-based transfer rules.

Despite these analytical differences, the water depth difference at the downstream end (P6) converged to 13.7%. Table 3 shows that flood propagation extent tended to be greater in XP-SWMM than in GUDS from upstream to downstream, although the differences were relatively small, ranging from a minimum of 0% to a maximum of 20.7%.

3.2.2. Case I-2 (Inclined Type)

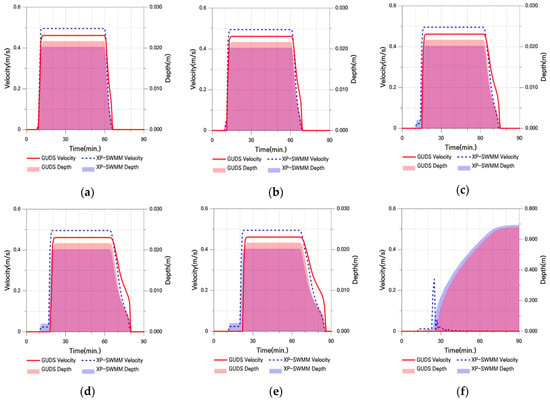

Case I-2 (Inclined Type) applies a slope of 0.5°. The maximum inundation depth, inundation area, and arrival time at each point are presented in Table 4. Table 5 shows the extent of inundation propagation in the x-direction, while Figure 8 illustrates the velocity and water depth at each point. The time series inundation maps generated by GUDS and XP-SWMM are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Table 4.

Maximum Velocity and Maximum Water Depth in Case Ⅰ-2.

Table 5.

Inundation Propagation in Case Ⅰ-2.

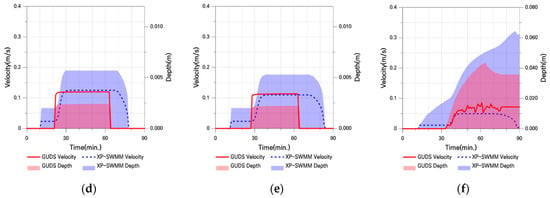

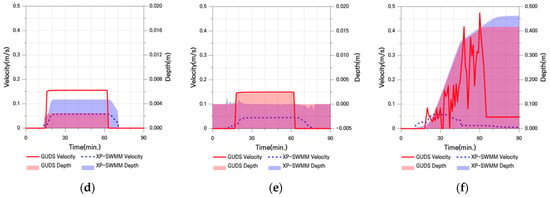

Figure 8.

Flow Velocity and Water Depth in Case I-2: (a) Point 1; (b) Point 2; (c) Point 3; (d) Point 4; (e) Point 5; (f) Point 6.

Figure 9.

Inundation Map of GUDS in Case I-2: (a) 00:10; (b) 00:20; (c) 00:30; (d) 00:40; (e) 00:50; (f) 01:00; (g) 01:10; (h) 01:20; (i) 01:30.

Figure 10.

Inundation Map of XP-SWMM in Case I-2: (a) 00:10; (b) 00:20; (c) 00:30; (d) 00:40; (e) 00:50; (f) 01:00; (g) 01:10; (h) 01:20; (i) 01:30.

In the upstream region, XP-SWMM exhibits higher flow velocities than GUDS, while the difference diminishes and even reverses at certain mid-to-downstream points (P4 and P5). Overall, XP-SWMM shows greater water depths and larger inundation areas compared to GUDS. This is because XP-SWMM rapidly propagates flows downstream due to fast initial inflows and increases in velocity and depth driven by advection, but experiences significant increases in water depth in downstream areas due to friction and energy losses.

In contrast, GUDS maintains relatively uniform velocities and shallower water depths because of the saturation of transferable flow between cells. At the downstream point (P6), where water depths of the two models converge, the maximum water depth difference between XP-SWMM and GUDS was 32.3%, which is relatively large. This difference is attributed to flow losses in XP-SWMM under increased slope conditions and can be interpreted as a form of numerical instability.

The extent of inundation propagation tends to diverge between the two models toward the downstream direction; however, the differences remain relatively similar, ranging from a minimum of 0% to a maximum of 25.8%.

3.2.3. Case I-3 (Inclined Type)

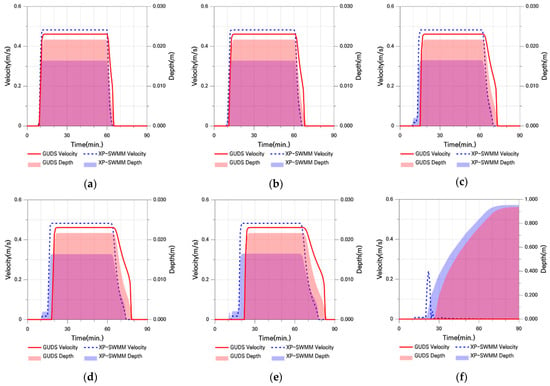

Case I-3 (Inclined Type) applies a slope of 1.0°. The maximum inundation depth and inundation area at each point are summarized in Table 6, while the number of inundated cells in the x-direction is shown in Table 7. The velocity and water depth results are presented in Figure 11, and the inundation maps from GUDS and XP-SWMM at 10 min intervals are shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Table 6.

Maximum Velocity and Maximum Water Depth in Case Ⅰ-3.

Table 7.

Inundation Propagation in Case Ⅰ-3.

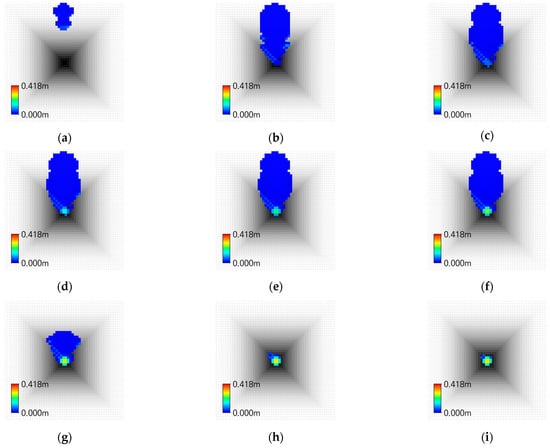

Figure 11.

Flow Velocity and Water Depth in Case Ⅰ-3: (a) Point 1; (b) Point 2; (c) Point 3; (d) Point 4; (e) Point 5; (f) Point 6.

Figure 12.

Inundation Map of GUDS in Case Ⅰ-3: (a) 00:10; (b) 00:20; (c) 00:30; (d) 00:40; (e) 00:50; (f) 01:00; (g) 01:10; (h) 01:20; (i) 01:30.

Figure 13.

Inundation Map of XP-SWMM in Case Ⅰ-3: (a) 00:10; (b) 00:20; (c) 00:30; (d) 00:40; (e) 00:50; (f) 01:00; (g) 01:10; (h) 01:20; (i) 01:30.

Overall, the results are similar to those of Case I-2; however, as the catchment slope increases, the point at which velocity magnitudes between the two models reverse occurs earlier, at P3. GUDS generally exhibits higher velocities than XP-SWMM, but XP-SWMM shows consistently greater water depths. This is because increased pressure leads to deeper water depths and higher friction, which in turn reduces velocities in XP-SWMM.

In particular, numerical instability was observed in the downstream area of Case I-3, where water depths were lost due to the increased slope. GUDS tends to yield relatively higher velocities because its water-level-difference-based velocity estimation simplifies the effects of slope. Similar to Case I-2, at the downstream convergence point (P6), the maximum water depth difference between the two models reached 33.1%, which is relatively large. This can be interpreted as numerical instability in XP-SWMM under steep slope conditions.

Unlike Case I-1 and Case I-2, the inundation propagation pattern in Case I-3 is generally similar between P1 and P5, but numerical instability in XP-SWMM caused water depth loss in the downstream area. Nonetheless, in the upstream region, where flows are concentrated, the differences remained relatively small, ranging from 0% to 13.3%.

3.3. Case II (Single Grid of Inclined Type)

Case II (Single Grid of Inclined Type) consists of a single grid aligned in the longitudinal direction and was designed to compare water depth and flow velocity without considering lateral flow diffusion.

3.3.1. Case II-1 (Single Grid of Inclined Type)

Case Ⅱ-1 assumes a catchment with a uniform slope of 0.1°, identical to Case I-1. The maximum inundation depth and inundation area at each point for XP-SWMM and GUDS are presented in Table 8, while the velocity and water depth graphs are shown in Figure 14.

Table 8.

Maximum Velocity and Maximum Water Depth in Case Ⅱ-1.

Figure 14.

Flow Velocity and Water Depth in Case Ⅱ-1: (a) Point 1; (b) Point 2; (c) Point 3; (d) Point 4; (e) Point 5; (f) Point 6.

In Case II-1, GUDS exhibits a constant flow velocity and a relatively uniform water depth distribution due to its simplified water level difference-based rules and flow limitations. The XP-SWMM results also show a nearly constant velocity from P1 to P4, reflecting the effects of inertia and pressure. The differences between the two models are very small: velocity differences range from 0.1% to 3.8% between P1 and P5, and water depth differences are between 0.8% and 4.1% across the entire section.

3.3.2. Case II-2 (Single Grid of Inclined Type)

Case II-2 assumes a catchment with a uniform slope of 0.5°, identical to Case I-2. The maximum inundation depth and inundation area at each point for XP-SWMM and GUDS are presented in Table 9, while the velocity and water depth graphs are shown in Figure 15.

Table 9.

Maximum Velocity and Maximum Water Depth in Case Ⅱ-2.

Figure 15.

Flow Velocity and Water Depth in Case Ⅱ-2: (a) Point 1; (b) Point 2; (c) Point 3; (d) Point 4; (e) Point 5; (f) Point 6.

In Case II-2, GUDS exhibits a constant flow velocity and a relatively uniform water depth distribution, similar to the results of Case II-1. The XP-SWMM results also show a nearly constant maximum velocity from P1 to P4, reflecting the effects of inertia and pressure associated with the slope, as observed in Case II-1. The differences between the two models are moderate: velocity differences are around 6% between P1 and P5, and water depth differences range from 2.0% to 7.3% across the entire section.

3.3.3. Case II-3 (Single Grid of Inclined Type)

Case II-3 assumes a catchment with a uniform slope of 1.5°, identical to Case I-3. The maximum inundation depth and inundation area at each point for XP-SWMM and GUDS are presented in Table 10, and the velocity and water depth graphs are shown in Figure 16.

Table 10.

Maximum Velocity and Maximum Water Depth in Case Ⅱ-3.

Figure 16.

Flow Velocity and Water Depth in Case Ⅱ-3: (a) Point 1; (b) Point 2; (c) Point 3; (d) Point 4; (e) Point 5; (f) Point 6.

In Case II-3, GUDS exhibits a constant flow velocity and a relatively uniform water depth distribution, similar to the results of Case II-1 and II-2. In the XP-SWMM results, as the slope increases, the influence of inertia and pressure extends from P1 to P5, leading to a larger section where maximum velocity remains constant. However, the maximum inundation depth shows relatively large differences of around 30% between P1 and P5. Nevertheless, at the downstream end of the catchment (P6), the maximum inundation depth difference between the two models converges to 1.8%, indicating very similar results.

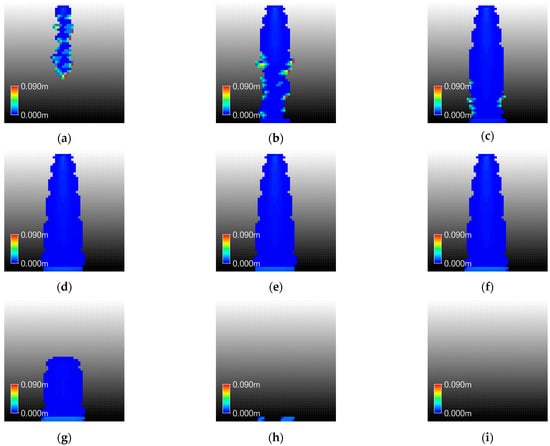

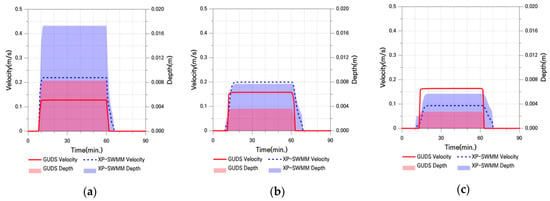

3.4. Case III (Funnel Type)

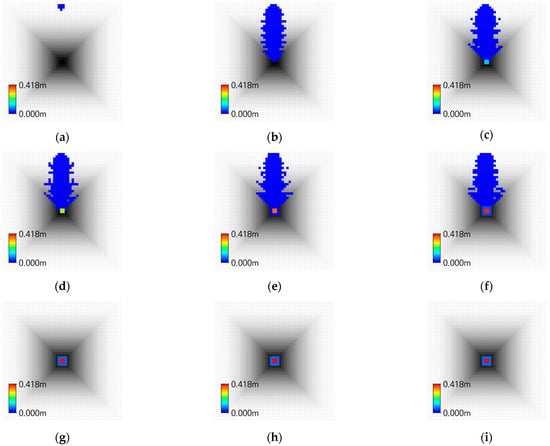

Case III (Funnel Type) was designed to compare inundation behavior in local low-lying areas that can occur in actual catchments. Five grids were assigned to each zone with varying slopes, which increased toward the center of the catchment. The slopes of each zone were set to 0.1°, 0.5°, 1.0°, 1.5°, and 2.0°, respectively. The maximum inundation depth and inundation area at each point for XP-SWMM and GUDS are presented in Table 11, the velocity and water depth comparison graphs are shown in Figure 17, and the 10 min interval inundation maps for GUDS and XP-SWMM are shown in Figure 18 and Figure 19.

Table 11.

Maximum Velocity and Maximum Water Depth in Case Ⅲ.

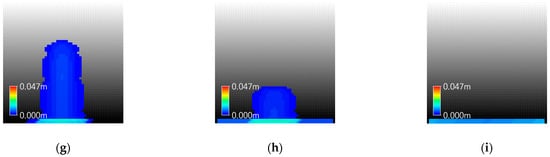

Figure 17.

Flow Velocity and Water Depth in Basic Case Ⅲ: (a) Point 1; (b) Point 2; (c) Point 3; (d) Point 4; (e) Point 5; (f) Point 6.

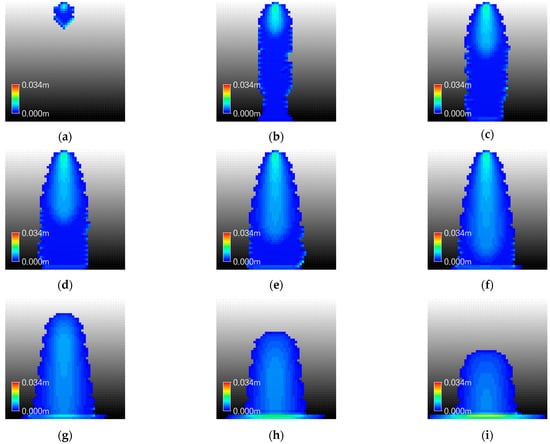

Figure 18.

Inundation Map of GUDS in Case Ⅲ: (a) 00:10; (b) 00:20; (c) 00:30; (d) 00:40; (e) 00:50; (f) 01:00; (g) 01:10; (h) 01:20; (i) 01:30.

Figure 19.

Inundation Map of XP-SWMM in Case Ⅲ: (a) 00:10; (b) 00:20; (c) 00:30; (d) 00:40; (e) 00:50; (f) 01:00; (g) 01:10; (h) 01:20; (i) 01:30.

In the upstream region (P1–P2), XP-SWMM exhibited faster flow velocities and flood propagation compared to GUDS. However, as the distance from the overflow point increased, both velocity and water depth decreased, and GUDS tended to exceed XP-SWMM downstream. Overall, XP-SWMM produced greater water depths than GUDS. Due to its consideration of inertia and pressure, XP-SWMM showed rapid initial flood propagation immediately after inflow, and in the steep slope section (P5), numerical instabilities occurred, leading to negative water depths. In contrast, GUDS showed slower propagation speeds but a tendency toward greater water depths due to flow saturation imposed by the upper limit of transferable flow.

Despite these analytical differences, at point P6—where inundation depths converged—the maximum inundation depth differed by only about 10% between the two models, confirming the reliability of the GUDS simulation results.

3.5. Maximum Water Depth and Inundation Area by Case

The maximum inundation depth and inundation area were compared for Case I (Inclined Type) and Case III (Funnel Type), excluding Case II (Single Grid of Inclined Type). As shown in Table 12, the difference in maximum inundation depth between GUDS and XP-SWMM was smallest in Case III at 9.8%, while the largest difference occurred in Case I-3 at approximately 32.4%. It should be noted that XP-SWMM exhibited numerical instabilities with increasing slope in Case I-2 and Case I-3.

Table 12.

Maximum Water Depth and Inundation Area by Case.

The difference in inundation area was smallest in Case I-3 at 0.3% and largest in Case I-2 at 19.1%. These results indicate that despite the differences in flow velocity estimation methods between the two models, the final inundation depths and inundation areas were estimated to be relatively close. XP-SWMM tends to propagate rapidly during the initial flow due to the inclusion of inertia and pressure terms, whereas GUDS smooths velocities through water-level-difference-based flow distribution and flow limitations. Over time, however, both models converged within practical tolerances in terms of inundation depth and area. This confirms that GUDS, despite its simplified computational structure, can produce results comparable to those of the commercial XP-SWMM model.

4. Validation and Limitations

Although this study provides a detailed quantitative comparison between XP-SWMM and GUDS under controlled conditions, no validation against observed flood data was conducted at this stage. The purpose of the current analysis was to isolate and evaluate the effects of the two models’ algorithmic differences—particularly in velocity estimation and numerical stability—under idealized terrain settings. As a result, the findings demonstrate methodological consistency and numerical behavior rather than direct real-world performance.

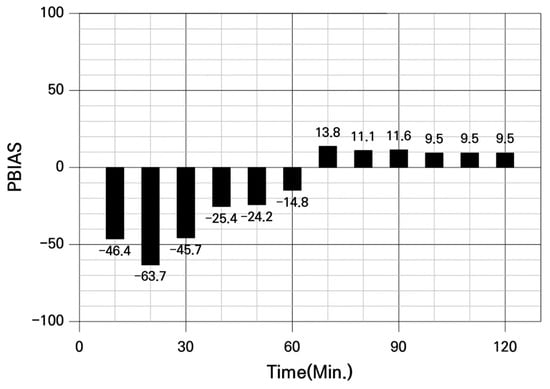

In this study, PBIAS-based evaluation was carried out only for Case III (Funnel Type), which represents a simplified localized depression. The constant-slope case was designed primarily to examine the overall pattern of flood propagation, but numerical instabilities made it unsuitable for reliable PBIAS-based assessment. As shown in Figure 20, PBIAS exhibits stable values from approximately 60 min after the end of node inflow, indicating that GUDS maintains a stable level of bias relative to XP-SWMM during the later ponding stage. According to widely used criteria in flood modeling, |PBIAS| < 25% is generally regarded as within the “satisfactory” performance range [23], and the Case III results fall within this range.

Figure 20.

Time-series PBIAS between GUDS and XP-SWMM for Case Ⅲ.

Future work will extend this framework to real urban flood events to confirm the practical applicability of the models. Observed data sources such as water level records, post-event field surveys, observed flood inundation maps, and hydrologic reports will be used for validation. Validation will be performed quantitatively using three key indices: the Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) and Percent Bias (PBIAS) for water depth, and the time of concentration. NSE evaluates the predictive accuracy of simulated water depth time series relative to observations, whereas PBIAS quantifies the average tendency of the model to over- or under-estimate observed depths. The time of concentration error represents the difference between the observed and simulated times of initial or peak inundation. Together, these metrics provide a robust assessment of both the accuracy and the temporal responsiveness of the models.

In addition, the spatial discretization schemes of the two models may cause localized discrepancies when comparing model outputs with observed inundation data. This limitation will be explicitly considered in future validation efforts to ensure fair and consistent assessment.

5. Conclusions

This study compared the open-source GUDS model, which adopts the WCA2D technique as its inundation analysis module, with the commercial XP-SWMM model under identical conditions, to evaluate how differences in flow velocity calculation affect flood propagation speed, flow paths, maximum inundation depth, and inundation area. Three idealized catchment types were considered: Case I (Inclined Type) representing a uniformly sloped surface, Case II (Single Grid of Inclined Type) consisting of a single longitudinal grid, and Case III (Funnel Type) with increasingly steep slopes toward the center to represent local low-lying areas.

The structural differences between the models determine the characteristics of flood propagation. XP-SWMM solves both the continuity and momentum equations, incorporating advection, pressure, friction, and external forces for a fully dynamic analysis. Consequently, it exhibits rapid flood propagation and spatial spread immediately after inflow due to inertia and pressure effects, followed by sharp increases or decreases in water depth as friction and topography become dominant downstream. In contrast, GUDS applies water-level-difference-based weighted flow transfer between adjacent cells, with velocity limited to the smaller of the critical and Manning velocities. It also conservatively estimates total transferable flow by including minimum and previously transferred flow volumes. As a result, GUDS shows pronounced flow flattening and terminal stopping behavior, with high numerical stability.

Although the two models showed noticeable differences in flood-wave propagation, their overall inundation outcomes were broadly comparable. Across the inclined catchments (Case I), maximum inundation depth and area at the downstream end generally differed by about 10–15%, with larger discrepancies only under the steepest slopes where XP-SWMM exhibited numerical instability. In the funnel-type catchment (Case III), differences were more modest—around 10% for maximum depth and below 10% for inundation area—indicating that both models produced similar results for localized depressions. In the single-grid inclined case (Case II), XP-SWMM showed stronger acceleration–deceleration behavior while GUDS maintained an almost constant flow velocity, yet the maximum depth differences across all cases remained within roughly 3.5%, suggesting that GUDS delivers practically acceptable accuracy despite its simplified computations. A preliminary PBIAS analysis conducted for the funnel-shaped catchment (Case III) further showed that the two models converge toward similar bias levels after the early-time fluctuations, suggesting stable relative behavior during later ponding periods.

To substantiate the claims under realistic conditions, future work will quantitatively compare simulations against inundation footprints derived from observed real-storm rainfall, and will systematically analyze sensitivity and uncertainty with respect to grid resolution and time step. Performance will be evaluated using metrics such as NSE and PBIAS, alongside map-based agreement of flood extent. These additions will delineate the regimes in which each formulation is most robust and bound expected errors under practical roughness, topography, and boundary conditions.

This study and previous comparative analyses confirm that GUDS maintains close agreement with XP-SWMM in terms of maximum inundation depth and inundation area. However, due to differences in flow velocity formulations, discrepancies in flood propagation paths and speeds may arise even under identical input conditions. Future research should focus on incorporating dynamic time stepping and applying calibration procedures when necessary to further enhance the accuracy and applicability of GUDS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Y., J.L. (Jungho Lee) and J.L. (Jungmin Lee); methodology, D.Y., J.L. (Jungho Lee) and D.K.; software, D.Y.; validation, D.Y., D.K. and J.L. (Jungmin Lee); formal analysis, D.Y. and D.K.; investigation, D.Y.; resources, J.L. (Jungmin Lee) and D.Y.; data curation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.L. (Jungmin Lee), D.Y. and J.L. (Jungho Lee); visualization, D.Y.; supervision, J.L. (Jungmin Lee) and D.Y.; project administration, J.L. (Jungmin Lee); funding acquisition, J.L. (Jungmin Lee). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00259995).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Choo, Y.-M.; Sim, S.-B.; Choe, Y.-W. A Study on Urban Inundation Using SWMM in Busan, Korea, Using Existing Dams and Artificial Underground Waterways. Water 2021, 13, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, B.; Bach, P.M.; Cunningham, L.; Deletic, A. A cellular automata fast flood evaluation (CA-ffé) model. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 4936–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidolin, M.; Duncan, A.; Ghimire, B.; Gibson, M.; Keedwell, E.; Chen, A.S.; Savic, D. CADDIES: A new framework for rapid development of parallel cellular automata algorithms for flood simulation. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Hydroinformatics (HIC 2012), Hamburg, Germany, 14–18 July 2012; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10036/3742 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Feng, S.; Li, Q. Simulation of urban flood in Jinan City based on Caflood. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Energy and Environmental Protection (ICEEP 2017), Zhuhai, China, 24–26 April 2017; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; 143, pp. 1427–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.J.; Yu, H.L.; Wang, C.H.; Chen, A.S. Dynamic-wave cellular automata framework for shallow water flow modeling. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, O.T.; Yang, T.H. A novel hybrid approach based on cellular automata and a digital elevation model for rapid flood assessment. Water 2021, 13, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, O.T.; Yang, T.H.; Hsu, H.M.; Gourbesville, P. A rapid flood inundation model for urban flood analyses. MethodsX 2023, 10, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.L.; Chang, T.J.; Wang, C.H.; Maa, S.Y. A coupled river–Overland (1D-2D) model for fluvial flooding assessment with cellular Automata. Water 2024, 16(18), 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Lago, C.A.; Giacomoni, M.H.; Bentivoglio, R.; Taormina, R.; Junior, M.N.G.; Mendiondo, E.M. Generalizing rapid flood predictions to unseen urban catchments with conditional generative adversarial networks. J. Hydrol. 2023, 618, 129276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, J.N.; Gyamfi, C.; Arthur, E. Impacts of retention basins on downstream flood peak attenuation in the Odaw river basin, Ghana. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 47, 101364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, G.D.A.; Ferreira, C.M.; Kinter, J.L., III; Cassalho, F. Real-time short-range flood forecasting based on a watershed scale 2-D hydrodynamic model and high-resolution precipitation forecast ensemble. J. Hydrol. 2025, 650, 132564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafri, S.A.; Cherhabil, S.; Hafnaoui, M.A.; Madi, M. Flood modeling using HEC-RAS 2D and IBER 2D: A comparative study. Water Supply 2024, 24, 3061–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifian, M.K.; Kesserwani, G.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Neal, J.; Bates, P. LISFLOOD-FP 8.1: New GPU accelerated solvers for faster fluvial/pluvial flood simulations. Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss. 2022, 16, 2391–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sañudo, E.; Cea, L.; Puertas, J. Modelling Pluvial Flooding in Urban Areas Coupling the Models Iber and SWMM. Water 2020, 12, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sañudo, E.; García-Feal, O.; Hagen, L.; Cea, L.; Puertas, J.; Montalvo, C.; Hofmann, J. IberSWMM+: A High-Performance Computing Solver for 2D–1D Pluvial Flood Modelling in Urban Environments. J. Hydrol. 2025, 651, 132603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidolin, M.; Chen, A.S.; Ghimire, B.; Keedwell, E.C.; Djordjević, S.; Savić, D.A. A weighted cellular automata 2D inundation model for rapid flood analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 84, 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.H.; Kim, D.J.; Jeon, J.H.; Song, Y.H.; Lee, J.H. Study of a grid-based urban drainage system analysis model. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2024, 24, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.H.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, J.H. Applicability assessment of a grid-based urban drainage system analysis model. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2025, 25, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TUFLOW. TUFLOW Classic/HPC User Manual, Version 2025.0; BMT Commercial Australia Pty Ltd.: Brisbane, Australia, 2025.

- Ministry of Environment (ME). Standard Guidelines for the Calculation of Flood Volume; Ministry of Environment: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan, J.F.; Mark, D.M. The extraction of drainage networks from digital elevation data. Comput. Vis. Graph. Image Process. 1984, 28, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, B.E.; Ratliff, K.; Tryby, M.E.; Wu, J.J.X.; Mullapudi, A. PySWMM: The Python interface to Stormwater Management Model (SWMM). J. Open Source Softw. 2020, 5, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Binger, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model Evaluation Guidelines for Systematic Quantification of Accuracy in Watershed Simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).