Virtual City Simulator: A Scenario-Based Tool for Multidimensional Urban Flood Long-Term Vulnerability Assessment and Planning in Mediterranean Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

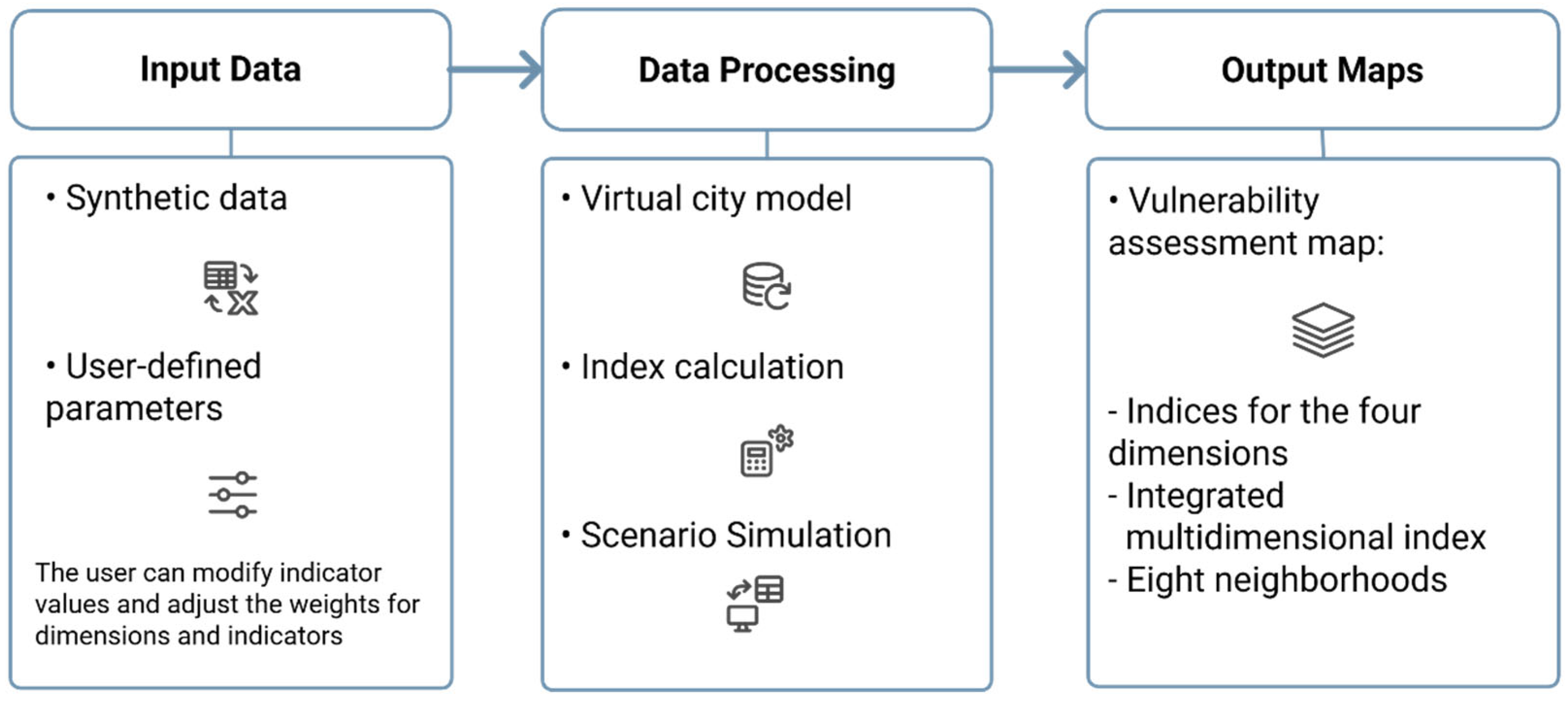

2. Methodology

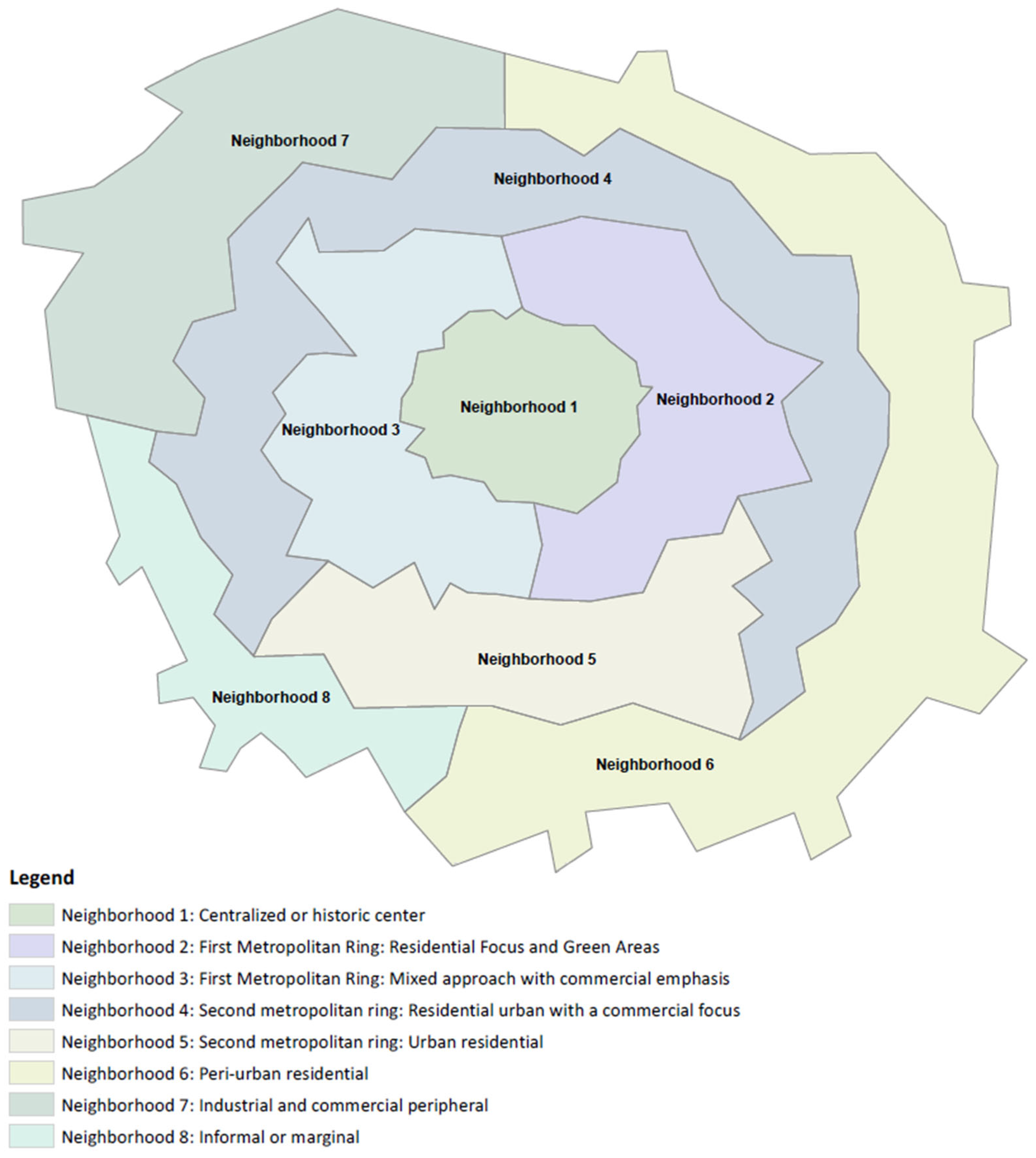

2.1. Design of the City

2.2. Data Estimation

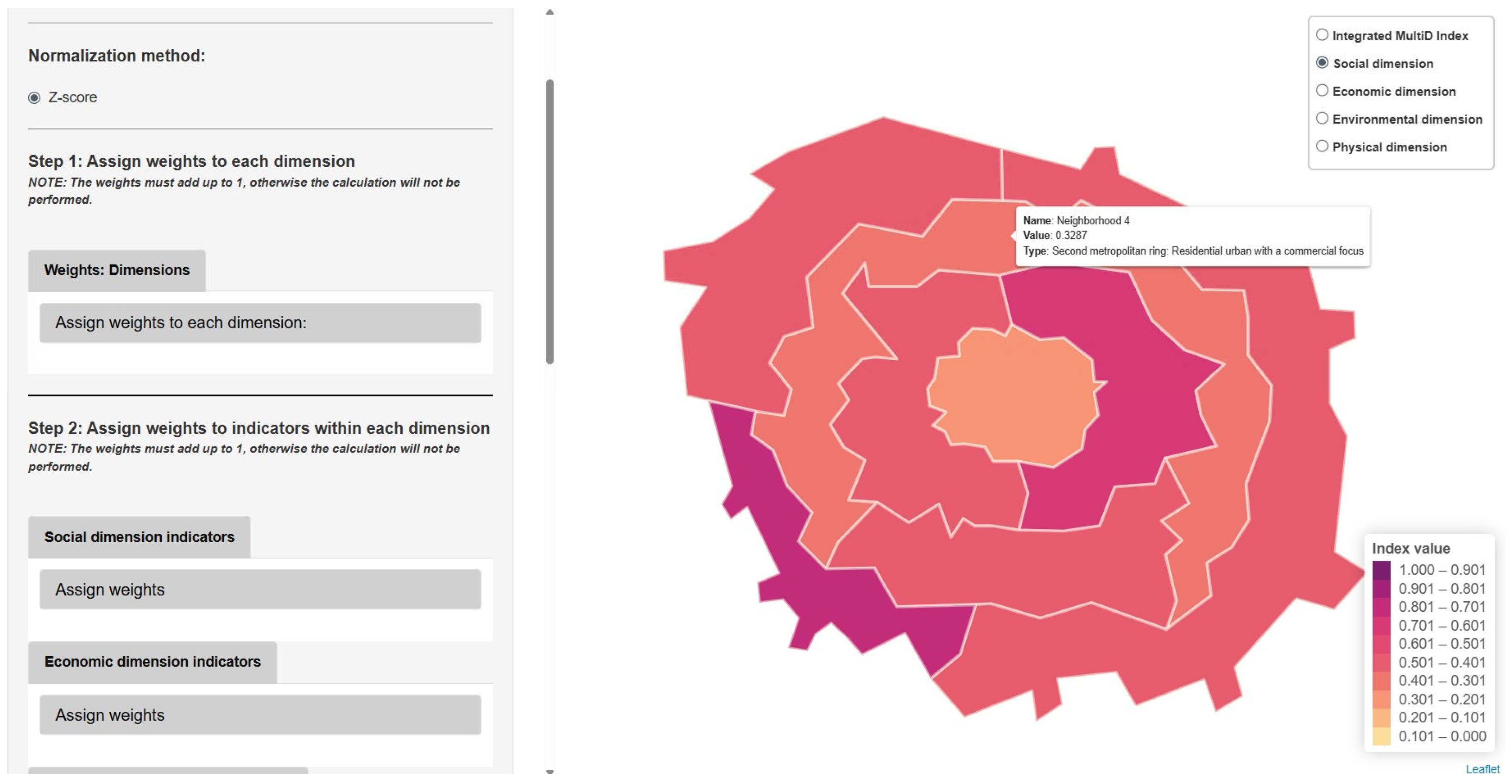

2.3. Interactive Tool Development

3. Results

3.1. Representative Virtual Mediterranean City

3.2. Database for Eight Types of Neighborhoods

3.3. Openly Accessible Virtual City Simulator

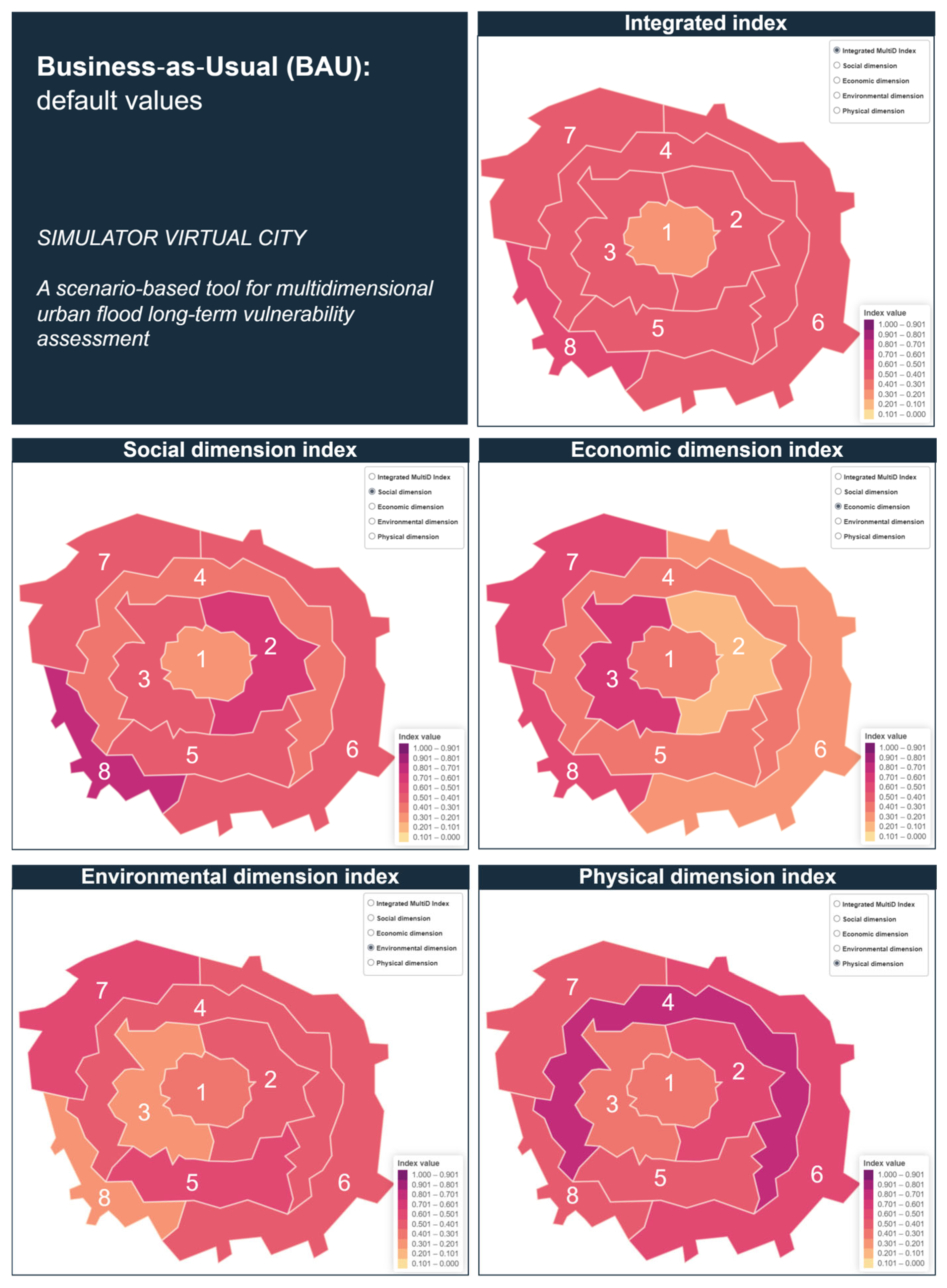

3.3.1. Case Study: Business-As-Usual (BAU)

3.3.2. Case Study: Resilience Intervention in Neighborhood 8

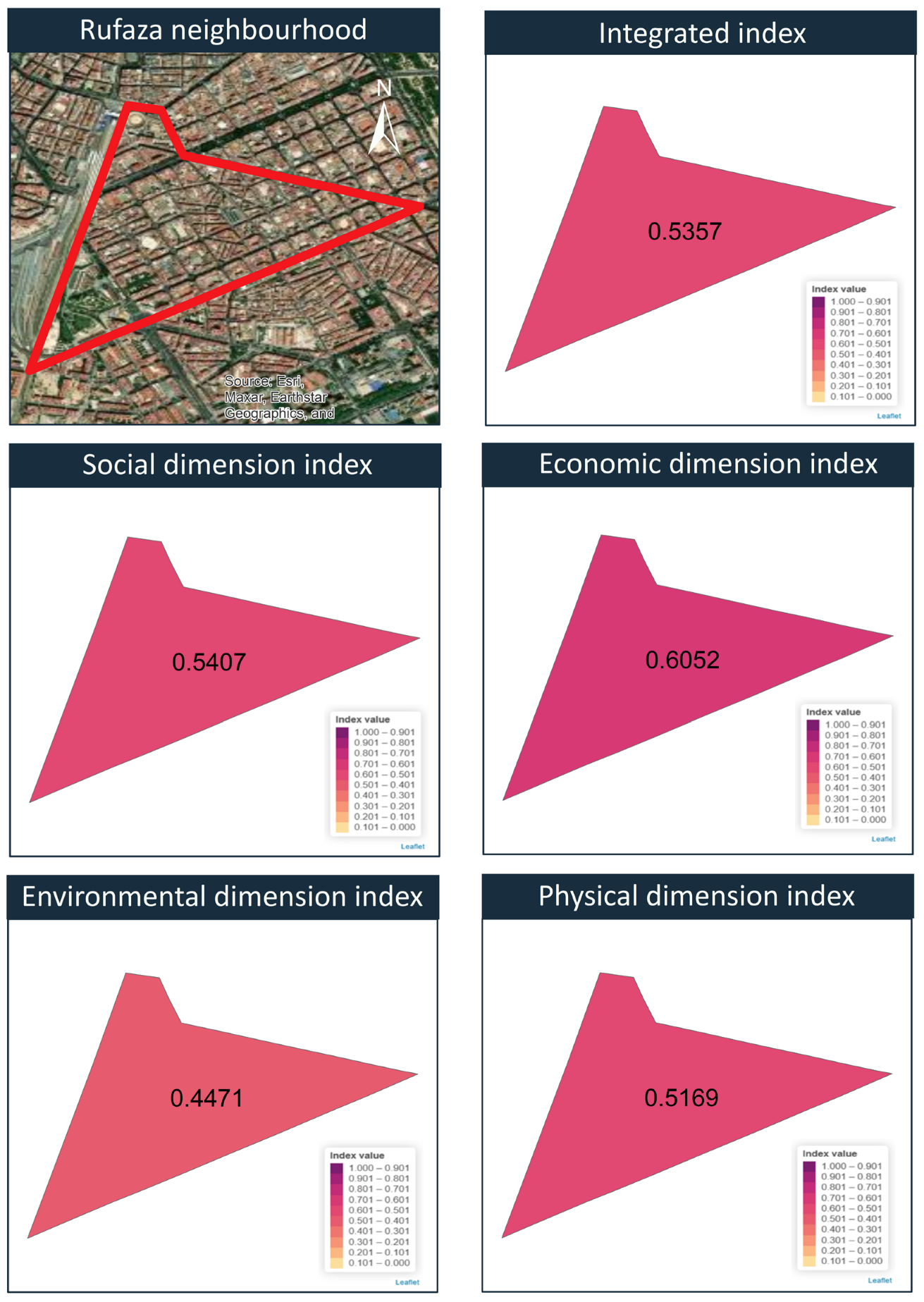

3.3.3. Case Study: Application to a Real Neighborhood: Ruzafa (Valencia)

4. Discussion

Limitations

- -

- Scope of the index: the integrated multidimensional vulnerability index (exposure, susceptibility, resilience across social, economic, environmental, and physical dimensions) does not integrate hazard; therefore, it does not estimate risk or expected damages. Without coupling to external hazard layers, risk-based prioritization is not yet possible. In practical applications, this limitation can be progressively overcome by linking the Simulator’s vulnerability outputs to existing flood-hazard products (e.g., EU Floods Directive maps) or to locally modeled inundation depth and velocity layers, thereby moving from a vulnerability-only perspective towards full risk assessment.

- -

- Spatial aggregation and MAUP: operating at zone-level Neighborhood Typologies enhances interpretability but introduces potential aggregation bias (MAUP) and can mask micro-pockets of disadvantage within otherwise resilient areas. In the current version, sub-neighborhood grids (≈250–500 m) and stratified reporting are not yet implemented. This can be mitigated in applied studies by complementing typology-level results with local knowledge and finer-scale data where available, and, in future versions of the tool, by incorporating editable sub-neighborhood grids and stratified indicators (e.g., deprivation or service-access proxies) to better capture intra-neighborhood heterogeneity.

- -

- Data reliability and temporal updating: in rapidly developing Mediterranean cities, the update frequency of available datasets may affect the accuracy of indicator ranges and, therefore, the resulting vulnerability assessments. Although indicator bounds were parameterized using multiple open-access and regionally relevant sources (e.g., Copernicus Urban Atlas, Eurostat, GHSL, RESCCUE), these datasets differ in their temporal resolution and may not fully capture recent demographic, infrastructural or land-use changes. To mitigate this, the Virtual City Simulator treats these ranges as transparent typology-based priors that can be progressively replaced with more recent municipal, census or remote-sensing data. In practice, we recommend that users update the default database with the latest available statistics and spatial products before each application, so that reliability increases as updated data become available, while maintaining analytical coherence in data-scarce environments.

- -

- Minimum data requirements: a practical question concerns the minimum amount of data required for the index to produce meaningful and locally representative results. Technically, the index can always be computed as long as every indicator has a value, whether based on empirical data or on the default typology ranges. However, when applied to real neighborhoods, the reliability of the assessment increases as a larger share of indicators is informed by up-to-date local data rather than by defaults. As a general guideline, we consider that having data for at least one indicator per dimension, and approximately one-third of the 36 indicators overall, provides a reasonable minimum for producing a vulnerability profile that reflects local conditions rather than mainly the underlying typology. Below this threshold, the index remains operational, but the resulting neighborhood characterization should be interpreted with caution, given the higher dependence on synthetic estimates.

- -

- Temporal staticity: the Virtual City Simulator currently compares static scenarios (e.g., BAU vs. intervention) and does not model dynamic evolution (infrastructure decay, demographic drift, land-use transitions). As a result, relevant feedback and effects are not captured. This limitation can be partially addressed by defining contrasting medium- and long-term scenarios (e.g., densification, infrastructure upgrades, socio-economic change) and, in future developments, by coupling the Simulator with dynamic planning frameworks that explicitly represent temporal trajectories.

- -

- Dependence on normative weights without stability analysis: default weights at the dimension and indicator levels encode a prior planning. Although editable in the tool, the manuscript does not yet present a systematic sensitivity analysis (e.g., weight sweeps) or rank-stability tests, which may affect the robustness of neighborhood comparisons. In applied contexts, we encourage users to explore alternative weighting schemes with stakeholders and to check whether rankings are stable under plausible changes in weights. Future work will include formal global sensitivity analysis and rank-stability diagnostics within the Simulator interface to guide users towards more robust interpretations.

5. Conclusions

- Integrated, scenario-ready framework. The Virtual City Simulator links the Virtual City (eight Neighborhood Typologies), a 36-indicator database with default values and ranges, and an interactive RStudio/Shiny interface to deliver a transparent, reproducible workflow for long-term, multidimensional flood-vulnerability assessment.

- Actionable diagnostics under data scarcity. By combining the observed neighborhood values with typology-based defaults, the simulator converts partial datasets into operational diagnostics, mapping indices with a multidimensional integrated approach and disaggregated by four dimensions (social, economic, environmental, and physical) on a common scale from 0 to 1.

- Interventions are effective. As shown in the second case study, editing five resilience indicators in the most vulnerable Neighborhood reduces the multidimensional integrated index from 0.5217 to 0.4898, confirming that targeted investments can lead to measurable reductions in vulnerability.

- Transferability to real cases. The application to Ruzafa (Valencia) yields an integrated multidimensional index of 0.5357 and a plausible dimension profile in which the economic dimension is the highest, the social and physical dimensions are similar and lower, and the environmental dimension is the lowest, corroborating the external validity of the Neighborhood Typology mapping and the Simulator’s usefulness in real-world planning.

- Estimated database for transfer/validation. We provide an estimated dataset structured in four dimensions and 36 indicators for eight neighborhood typologies, designed to support the application or validation of methodologies in contexts where access to data is limited, maintaining intensive units and traceability for replacement by municipal/census data when they exist.

- Tool with open access. It facilitates prioritizing neighborhoods, evaluating BAU trade-offs vs. intervention, and communicating results transparently for public decision use and call to action.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pietrapertosa, F.; Olazabal, M.; Simoes, S.G.; Salvia, M.; Fokaides, P.A.; Ioannou, B.I.; Viguié, V.; Spyridaki, N.-A.; De Gregorio Hurtado, S.; Geneletti, D.; et al. Adaptation to Climate Change in Cities of Mediterranean Europe. Cities 2023, 140, 104452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cea, L.; Sañudo, E.; Montalvo, C.; Farfán, J.; Puertas, J.; Tamagnone, P. Recent Advances and Future Challenges in Urban Pluvial Flood Modelling. Urban Water J. 2025, 22, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, J.; Schüttrumpf, H. Risk-Based Early Warning System for Pluvial Flash Floods: Approaches and Foundations. Geosciences 2019, 9, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, P.C.; Bolten, J.D.; Kumar, S.V.; Cleary, B. Deep Convolutional LSTM for improved flash flood prediction. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1346104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abily, M.; Bertrand, N.; Delestre, O.; Gourbesville, P.; Duluc, C.-M. Spatial Global Sensitivity Analysis of High Resolution Classified Topographic Data Use in 2D Urban Flood Modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 77, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cea, L.; Bladé, E. A Simple and Efficient Unstructured Finite Volume Scheme for Solving the Shallow Water Equations in Overland Flow Applications. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 5464–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunge, J.A.; Erlich, M. Hydroinformatics in 1999: What Is to Be Done? J. Hydroinform. 1999, 1, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delestre, O.; Darboux, F.; James, F.; Lucas, C.; Laguerre, C.; Cordier, S. FullSWOF: Full Shallow-Water Equations for Overland Flow. J. Open Source Softw. 2017, 2, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourbesville, P. Data and Hydroinformatics: New Possibilities and Challenges. J. Hydroinform 2009, 11, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Solomatine, D. A Framework for Uncertainty Analysis in Flood Risk Management Decisions. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2008, 6, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, B.; Velasco, M.; Locatelli, L.; Sunyer, D.; Yubero, D.; Monjo, R.; Martínez-Gomariz, E.; Forero-Ortiz, E.; Sánchez-Muñoz, D.; Evans, B.; et al. Assessment of Urban Flood Resilience in Barcelona for Current and Future Scenarios. The RESCCUE Project. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Pallathadka, A.; Sauer, J.; Grimm, N.B.; Zimmerman, R.; Cheng, C.; Iwaniec, D.M.; Kim, Y.; Lloyd, R.; McPhearson, T.; et al. Assessment of Urban Flood Vulnerability Using the Social-Ecological-Technological Systems Framework in Six US Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 68, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Vaca, A.N.; Popartan, L.A.; Nuss-Girona, S.; Rodríguez-Roda, I. Spatial Approach for Assessing Vulnerability to Urban Flooding: A Proposal for a Multidimensional Index. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 16799–16825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroca-Jiménez, E.; Bodoque, J.M.; García, J.A.; Figueroa-García, J.E. Holistic Characterization of Flash Flood Vulnerability: Construction and Validation of an Integrated Multidimensional Vulnerability Index. J. Hydrol. 2022, 612, 128083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, Z.; Meng, X.; Rana, I.A.; ur Rehman, M.; Su, X. Holistic Multidimensional Vulnerability Assessment: An Empirical Investigation on Rural Communities of the Hindu Kush Himalayan Region, Northern Pakistan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 62, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, I.A.; Routray, J.K. Multidimensional Model for Vulnerability Assessment of Urban Flooding: An Empirical Study in Pakistan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2018, 9, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Roy, S.; Bose, A.; Chowdhury, I.R. Multiscale GIS Based-Model to Assess Urban Social Vulnerability and Associated Risk: Evidence from 146 Urban Centers of Eastern India. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Bose, A.; Majumder, S.; Roy Chowdhury, I.; Abdo, H.G.; Almohamad, H.; Abdullah Al Dughairi, A. Evaluating Urban Environment Quality (UEQ) for Class-I Indian City: An Integrated RS-GIS Based Exploratory Spatial Analysis. Geocarto Int. 2022, 38, 2153932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Majumder, S.; Bose, A.; Chowdhury, I.R. Spatial Heterogeneity in the Urban Household Living Conditions: A-GIS-Based Spatial Analysis. Ann. GIS 2024, 30, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Majumder, S.; Bose, A.; Roy Chowdhury, I. Does Geographical Heterogeneity Influence Urban Quality of Life? A Case of a Densely Populated Indian City. Pap. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 9, 395–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsari, R.; Nadizadeh Shorabeh, S.; Kouhnavard, M.; Homaee, M.; Arsanjani, J.J. A Spatial Decision Support Approach for Flood Vulnerability Analysis in Urban Areas: A Case Study of Tehran. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, O.D.; van Aalst, M.K.; Birkmann, J.; Fordham, M.; McGregor, G.; Mechler, R. Determinants of Risk: Exposure and Vulnerability. In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Field, C.B., Barros, V., Stocker, T.F., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rasool, S.; Rana, I.A.; Waseem, H.B. Assessing Multidimensional Vulnerability of Rural Areas to Flooding: An Index-Based Approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2024, 15, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Burton, C.G.; Emrich, C.T. Disaster Resilience Indicators for Benchmarking Baseline Conditions. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2010, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Tignor, M.M.B.; Poloczanska, E.S.; Mintenbeck, K.; Alegría, A.; Craig, M.; Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V.; et al. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M.M.B., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Birkmann, J.; Cardona, O.D.; Carreño, M.L.; Barbat, A.H.; Pelling, M.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Kienberger, S.; Keiler, M.; Alexander, D.; Zeil, P.; et al. Framing Vulnerability, Risk and Societal Responses: The MOVE Framework. Nat. Hazards 2013, 67, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Our City Plans: An Incremental and Participatory Toolbox for Urban Planning|UN-Habitat. 2020. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/our-city-plans-an-incremental-and-participatory-toolbox-for-urban-planning (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- UN-Habitat. The Challenge of Slums. In World Cities Report; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Bank’s Fall 2023 Regional Economic Updates, 2023. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/10/04/world-bank-fall-2023-regional-economic-updates (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Eurostat/DEGURBA. Methodology–Degree of Urbanisation–Eurostat, 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/degree-of-urbanisation/methodology (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Antofie, T.E.; Salvi, A.; Sibilia, A.; Salari, S.; Rodomonti, D.; Corbane, C. Evidence for Disaster Risk Management from the Risk Data Hub- Analytical Reports on Natural Hazards, Vulnerabilities and Disaster Risks in Europe Based on the DRMKC–Risk Data Hub; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Taubenböck, H.; Debray, H.; Qiu, C.; Schmitt, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.X. Seven City Types Representing Morphologic Configurations of Cities across the Globe. Cities 2020, 105, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero Gómez, L.A. La Segunda ola de la España Vaciada: La Despoblación de las Ciudades Medias en el Siglo XXI; Edicions de la Universitat de Lleida: Lleida, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tascón-González, L.; Ferrer-Julià, M.; Ruiz, M.; García-Meléndez, E. Social Vulnerability Assessment for Flood Risk Analysis. Water 2020, 12, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufat, S.; Tate, E.; Burton, C.G.; Maroof, A.S. Social Vulnerability to Floods: Review of Case Studies and Implications for Measurement. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 14, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobkova, E.; Berghauser Pont, M.; Marcus, L. Towards Analytical Typologies of Plot Systems: Quantitative Profile of Five European Cities. Environ. Plan. B Urban. Anal. City Sci. 2021, 48, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, P.P.; Serrano, V.R.D.Á.; Salamanca, A.M.E.D.; Trapero, E.S.; Tordesillas, J.M.C. Identificación, clasificación y análisis de las formas urbanas en ciudades medias: Aplicación a las capitales provinciales de Castilla-La Mancha. An. Geogr. Univ. Complut. 2018, 38, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. A Critical Review of Selected Tools for Assessing Community Resilience. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 69, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Vaca, A.N.; Popartan, L.A.; Nuss Girona, S.; Rodríguez-Roda, I. Multidimensional Urban Flood Vulnerability Dataset: Indicators from Girona, Spain, 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15703616 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- European Union; Bank; FAO; UN-Habitat; OECD; The World. Applying the Degree of Urbanisation: A Methodological Manual to Define Cities, Towns and Rural Areas for International Comparisons: 2021 Edition; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2021.

- OECD. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2008.

- Chang, W.; Cheng, J.; Allaire, J.J.; Sievert, C.; Schloerke, B.; Xie, Y.; Allen, J.; McPherson, J.; Dipert, A.; Borges, B.; et al. Shiny: Web Application Framework for R, 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/shiny/index.html (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Schimpf, C.; Castellani, B. COMPLEX-IT: A Case-Based Modeling and Scenario Simulation Platform for Social Inquiry. JORS 2020, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, P.; Serrano-Estrada, L.; Nolasco-Cirugeda, A.; Baeza, J.L. Revisiting the Spatial Definition of Neighborhood Boundaries: Functional Clusters versus Administrative Neighborhoods. J. Urban. Technol. 2022, 29, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Ortiz, C.; Marquet, O.; Mojica, L.; Vich, G. Barcelona under the 15-Minute City Lens: Mapping the Accessibility and Proximity Potential Based on Pedestrian Travel Times. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Gascon, M.; Martinez, D.; Ponjoan, A.; Blanch, J.; Garcia-Gil, M.D.M.; Ramos, R.; Foraster, M.; Mueller, N.; Espinosa, A.; et al. Air Pollution, Noise, Blue Space, and Green Space and Premature Mortality in Barcelona: A Mega Cohort. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Masip, L.; Pearsall, H. Assessing Green Gentrification in Historically Disenfranchised Neighborhoods: A Longitudinal and Spatial Analysis of Barcelona. Urban. Geogr. 2018, 39, 458–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Garcia-Ramon, M.D.; Prats, M. Women’s Use of Public Space and Sense of Place in the Raval (Barcelona). GeoJournal 2004, 61, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gianoli, A.; Palazzolo Henkes, R. The Evolution and Adaptive Governance of the 22@ Innovation District in Barcelona. Urban. Sci. 2020, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-López, M.-À. Urban Spatial Structure, Suburbanization and Transportation in Barcelona. J. Urban. Econ. 2012, 72, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliarin, S. Linking Processes and Patterns: Spatial Planning, Governance and Urban Sprawl in the Barcelona and Milan Metropolitan Regions. Urban. Stud. 2018, 55, 3650–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Carlucci, M. Urban Growth and Land-Use Structure in Two Mediterranean Regions: An Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 2158244014561199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egidi, G.; Cividino, S.; Vinci, S.; Sateriano, A.; Salvia, R. Towards Local Forms of Sprawl: A Brief Reflection on Mediterranean Urbanization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca Cladera, J.; Burns, M.; Alhaddad, B.E.; Carreras Quilis, J.M. Monitoring Urban Growth Around the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona with Spot Satellite Imagery; Semana de geomática: Bogotá, Colombia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Henriquez Urena, S. Analysis of Strategic Locations for Urban Logistics in the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona, 2024. Available online: https://upcommons.upc.edu/entities/publication/ec5280ab-b3f4-47b5-9780-4226db2556b1 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Kuffer, M. Monitoring Slums and Informal Settlements in Europe; JRC Publications Repository; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC130204 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- UNECE. Formalizing the Informal: Challenges and Opportunities of Informal Settlements in South-East Europe|UNECE. 2015. Available online: https://unece.org/housing-and-land-management/publications/formalizing-informal-challenges-and-opportunities-informal (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- UN-Habitat. Guide to the City Resilience Profiling Tool|UN-Habitat. 2018. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/guide-to-the-city-resilience-profiling-tool (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Geoportal València|Ajuntament de València. Ajuntament de València. Available online: https://geoportal.valencia.es/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Cook, B.R.; Cornes, I.; Satizábal, P.; de Lourdes Melo Zurita, M. Experiential Learning, Practices, and Space for Change: The Institutional Preconfiguration of Community Participation in Flood Risk Reduction. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2025, 18, e12861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, I.; Fernández-Casal, R. tvReg: Time-Varying Coefficients in Multi-Equation Regression in R. R J. 2022, 14, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array Programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkel, J.M. Challenge to Scientists: Does Your Ten-Year-Old Code Still Run? Nature 2020, 584, 656–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligtermoet, E.; Munera-Roldan, C.; Robinson, C.; Sushil, Z.; Leith, P. Preparing for Knowledge Co-Production: A Diagnostic Approach to Foster Reflexivity for Interdisciplinary Research Teams. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Puy, A. What Can Mathematical Modelling Contribute to a Sociology of Quantification? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antofie, T.-E.; Luoni, S.; Tilloy, A.; Sibilia, A.; Salari, S.; Eklund, G.; Rodomonti, D.; Bountzouklis, C.; Corbane, C. Spatial Identification of Regions Exposed to Multi-Hazards at the Pan-European Level. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 25, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchiorri, M.; Freire, S.; Schiavina, M.; Florczyk, A.; Corbane, C.; Maffenini, L.; Pesaresi, M.; Politis, P.; Szabo, F.; Ehrlich, D.; et al. The Multi-Temporal and Multi-Dimensional Global Urban Centre Database to Delineate and Analyse World Cities. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, X.; Aerts, J.C.J.H.; Wang, J.; Yin, J.; Lin, N.; Wright, N.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Wen, J.; Qiu, F.; et al. Dynamic Flood Adaptation Pathways for Shanghai under Deep Uncertainty. NPJ Nat. Hazards 2025, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian, F.; Delavar, M.; Morid, S.; Jamshidi, S. Designing Climate Change Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways for Agricultural Water Management Using a Socio-Hydrological Modeling Approach. J. Hydrol. 2023, 627, 130398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, M.; Darch, G.; Denisart, B.; Roberts, D.; Wilkes, M.; Brown, S.; Kruitwagen, L. A Robust Decision-Making Approach in Climate Policy Design for Possible Net Zero Futures. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 162, 103886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo-Aguilar, C.; Agulles, M.; Jordà, G. Frontiers|Introducing Uncertainties in Composite Indicators. The Case of the Impact Chain Risk Assessment Framework. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 1019888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Aleksankina, K.; Becker, W.; Fennell, P.; Ferretti, F.; Holst, N.; Li, S.; Wu, Q. Why so Many Published Sensitivity Analyses Are False: A Systematic Review of Sensitivity Analysis Practices. Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 114, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbard, K.; Kyessi, A.G.; Limbumba, T.M. How Co-Production Contributes to Urban Equality: Retrospective Lessons from Dar Es Salaam. Environ. Urban. 2022, 34, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Typology of Neighborhood | Functional Profile | Planning Challenges | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood 1: Centralized or historic center Area: 9 km2 Population: 85,000 inh. | Dense mixed-use: residential, commercial, administrative, and cultural in an irregular layout; high economic activity and average income; lack of green space. | Modernization with heritage preservation; reduction in inequality; improvement of infrastructure without loss of cultural value. | [27,48,49] |

| Neighborhood 2: First Metropolitan Ring: Residential focus and green areas Area: 13 km2 Population: 70,000 inh. | Residential area with good transport links, tree-lined streets, and high livability; moderate economic activity. | Maintain green residential balance; protect green areas from overdevelopment; strengthen connections with the city center. | [11,27,50] |

| Neighborhood 3: First Metropolitan Ring: Mixed with commercial emphasis Area: 13 km2 Population: 100,000 inh. | Dense, dynamic, and economically active; extensive coverage of services and commerce; exposure by density and soil sealing (imperviousness). | Growth and soil sealing (imperviousness) control; sustainability measures while maintaining economic dynamism. | [27,51,52] |

| Neighborhood 4: Second Metropolitan Ring: Residential urban with commercial focus Area: 17 km2 Population: 150,000 inh. | High density of multifamily housing; diverse local economy; relatively developed drainage system; limited biodiversity. | Manage density; promote urban biodiversity; maintain and strengthen drainage system. | [27,28,53] |

| Neighborhood 5: Second Metropolitan Ring: Urban residential Area: 10 km2 Population: 40,000 inh. | Exhibits a dispersed urban morphology, characterized by predominant single-family dwellings and moderate commercial intensity within comparatively green environs. | Preserve tranquility; improve resilience with infrastructure; contain commercial growth. | [27,51,54] |

| Neighborhood 6: Peri-urban residential Area: 18 km2 Population: 30,400 inh. | Low density and abundant green space/leisure; high income; limited services/infrastructure. | Prevent degradation of green areas; improve connectivity and infrastructure without compromising environmental quality. | [27,55,56] |

| Neighborhood 7: Industrial and commercial peripheral Area: 12 km2 Population: 10,200 inh. | Industrial economic hub; low residential density; strong road network; shortage of open spaces. | Economic diversification; mitigation of environmental impacts; improved access to services. | [27,57] |

| Neighborhood 8: Informal or marginal Area: 9 km2 Population: 14,400 inh. | Informal settlements; poor infrastructure; subsistence economies; strong social cohesion. | Basic infrastructure; social inclusion; and economic formalization to reduce systemic vulnerability. | [27,58,59] |

| Dimension/ Neighborhood | Social Index | Economic Index | Environmental Index | Physical Index | Integrated Index |

| Neighborhood 1 | 0.2418 | 0.3224 | 0.3211 | 0.3072 | 0.2935 |

| Neighborhood 2 | 0.6118 | 0.1541 | 0.4148 | 0.5087 | 0.4369 |

| Neighborhood 3 | 0.4333 | 0.6668 | 0.2355 | 0.3075 | 0.4243 |

| Neighborhood 4 | 0.3287 | 0.3734 | 0.4179 | 0.7085 | 0.4672 |

| Neighborhood 5 | 0.4814 | 0.3283 | 0.5932 | 0.4578 | 0.4528 |

| Neighborhood 6 | 0.4594 | 0.2322 | 0.4774 | 0.5091 | 0.4202 |

| Neighborhood 7 | 0.4546 | 0.5357 | 0.5674 | 0.4112 | 0.4788 |

| Neighborhood 8 | 0.7063 | 0.5147 | 0.2610 | 0.4733 | 0.5217 |

| Dimension | BAU | Resilience Intervention | ∆ Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Index | 0.7063 | 0.6909 | −0.0154 |

| Economic Index | 0.5147 | 0.3830 | −0.1319 |

| Environmental Index | 0.2610 | 0.2610 | 0.0000 |

| Physical Index | 0.4733 | 0.460 | −0.0157 |

| Integrated Index | 0.5217 | 0.4898 | −0.0423 |

| ID | Dimension | Indicator | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Social | Population: density (inh./km2) | ≈27,800 |

| 2 | Social | Immigration: percentage of population (%) | ≈21.8% |

| 3 | Social | Gender condition: percentage of femininity (%) | ≈53.6% |

| 4 | Social | Age extremes: percentage of population (%) | ≈33.8% |

| 7 | Social | Population with low level of education: percentage of population (%) | ≈33% |

| 12 | Economic | Income per person (EUR/person × year) | 14,000 |

| 13 | Economic | Active workers: percentage of population (%) | ≈48% |

| 16 | Economic | Average prices (EUR/useful m2) | ≈4000 |

| 20 | Environmental | Tree species: (number) | 400 |

| 22 | Environmental | Spaces with permeability deficit: compact areas (m2/inh.) | 50 |

| 23 | Environmental | Areas with a deficit of vegetation: areas with little presence of urban trees (m2/inh.) | 7 |

| 26 | Environmental | Specific plans: (number) | 2 |

| 27 | Physical | Urban context: density of the built environment (km/km2) | ≈130 |

| 36 | Physical | Urbanization plans and projects: (number) | 34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomez Vaca, A.N.; Popartan, L.A.; Selvas, G.A.; Nuss-Girona, S.; Abily, M.; Rodríguez-Roda, I. Virtual City Simulator: A Scenario-Based Tool for Multidimensional Urban Flood Long-Term Vulnerability Assessment and Planning in Mediterranean Cities. Water 2025, 17, 3538. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243538

Gomez Vaca AN, Popartan LA, Selvas GA, Nuss-Girona S, Abily M, Rodríguez-Roda I. Virtual City Simulator: A Scenario-Based Tool for Multidimensional Urban Flood Long-Term Vulnerability Assessment and Planning in Mediterranean Cities. Water. 2025; 17(24):3538. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243538

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomez Vaca, Ana Noemí, Lucía Alexandra Popartan, Guillem Armengol Selvas, Sergi Nuss-Girona, Morgan Abily, and Ignasi Rodríguez-Roda. 2025. "Virtual City Simulator: A Scenario-Based Tool for Multidimensional Urban Flood Long-Term Vulnerability Assessment and Planning in Mediterranean Cities" Water 17, no. 24: 3538. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243538

APA StyleGomez Vaca, A. N., Popartan, L. A., Selvas, G. A., Nuss-Girona, S., Abily, M., & Rodríguez-Roda, I. (2025). Virtual City Simulator: A Scenario-Based Tool for Multidimensional Urban Flood Long-Term Vulnerability Assessment and Planning in Mediterranean Cities. Water, 17(24), 3538. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243538