Abstract

The Tarim Basin is currently the largest petroliferous basin in China, with hydrocarbons primarily hosted in Ordovician marine carbonate paleokarst fracture–vug reservoirs—a typical example being the Tahe Oilfield located in the northern structural uplift of the basin. The principle of “the present is the key to the past” serves as a core method for studying paleokarst fracture–vug reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield. The deep and ultra-deep carbonate fracture–vug reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield formed under humid tropical to subtropical paleoclimates during the Paleozoic Era, belonging to a humid tropical–subtropical paleoepikarst dynamic system. Modern karst types in China are diverse, providing abundant modern karst analogs for paleokarst research in the Tarim Basin. Carbonate regions in Eastern China can be divided into two major zones from north to south: the arid to semiarid north karst and the humid tropical–subtropical south karst. Karst in Northern China is characterized by large karst spring systems, with fissure–conduit networks as the primary aquifers; in contrast, karst in Southern China features underground river networks dominated by conduits and caves. From the perspective of karst hydrodynamic conditions, the paleokarst environment of deep fracture–vug reservoirs in the Tarim Basin exhibits high similarity to the modern karst environment in Southern China. The development patterns of karst underground rivers and caves in Southern China can be applied to comparative studies of carbonate fracture–vug reservoir structures in the Tarim Basin. Research on modern and paleokarst systems complements and advances each other, jointly promoting the development of karstology from different perspectives.

1. Introduction

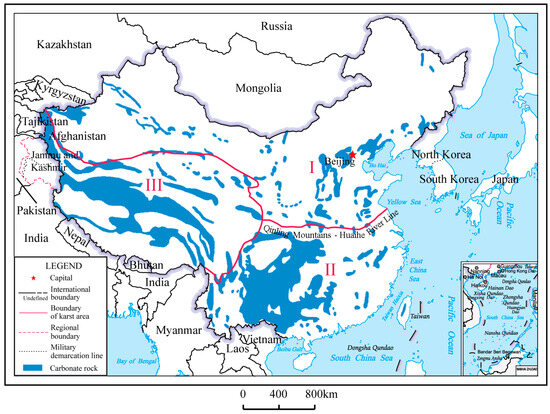

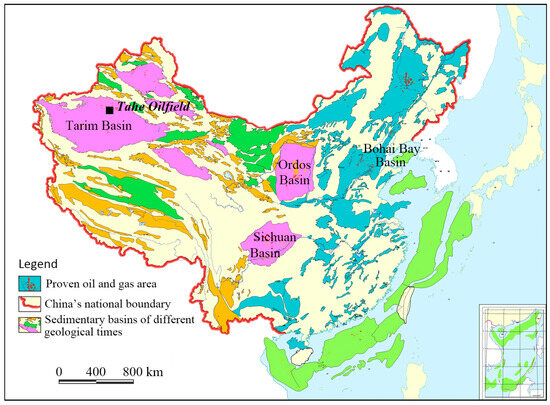

Karstification is a critical process in nature for the formation of fracture–vug aquifer media and oil and gas reservoirs in carbonate rocks. The global distribution extent of modern karst is approximately 20.274 million km2, accounting for about 15.2% of the Earth’s land surface [1]. China is one of the countries with the most extensive carbonate rock distribution and the richest variety of karst types worldwide, with a total carbonate rock distribution area of 3.44 million km2, constituting roughly one-third of its land area [2]. Influenced by factors such as lithology, tectonics, and climate, China exhibits diverse epigene karst types, with its surface karst systems and karst water resources demonstrating distinct differences between the southern and northern regions. Based on karst dynamic conditions, karst regions in China are typically divided into three major zones (Figure 1): the Northern Karst Zone (Zone I), the Southern Karst Zone (Zone II), and the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Karst Zone (Zone III) [3]. However, due to variations in disciplinary perspectives and industry priorities, the aforementioned statistical data on karst distribution in China do not include deep and ultra-deep paleokarst fracture–vug reservoirs relevant to the petroleum geology field. The Tarim Basin, Ordos Basin, Sichuan Basin, and Bohai Bay Basin are the four major onshore petroliferous basins in China (Figure 2). Deeply buried carbonate formations in these basins host paleokarst weathering crust reservoirs formed by tectonic uplift and exposure in geological history, which are typical of epigene karst hydrodynamic origin [4]. Among them, the Tarim Basin is currently the largest petroliferous basin in China, with deeply buried fracture–vug carbonate reservoirs in the northern part of the basin.

Figure 1.

Map of karst distribution in China.

Figure 2.

Map of petroliferous basin distribution in China.

In the exploration and production studies of such reservoirs, modern karst geological models and research methodologies are often referenced, incorporating the methodological principle of “the present is the key to the past” [5,6,7]. High-precision 3D seismic data are employed to establish seismic identification models of paleokarst caves, thereby revealing the spatial distribution patterns of paleokarst fracture–vug reservoirs. The insights gained into paleokarst geology not only provide support for oilfield exploration and production but also further enrich the current research scope of karstology [8].

This paper commences with an analysis of the commonalities between modern karst and paleokarst research. By synthesizing the characteristics of modern karst in China that are closely associated with typical paleokarst reservoirs in the Tarim Basin, it examines the current research status and karstological significance of deep and ultra-deep paleokarst fracture–vug hydrocarbon reservoirs, and further explores potential future research directions.

2. Paleokarst Characteristics of Fracture–Vug Hydrocarbon Reservoirs in the Northern Tarim Basin

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.1.1. Regional Geological and Tectonic Setting

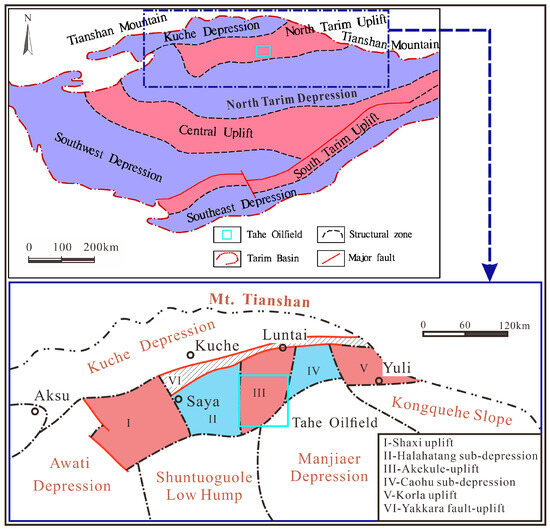

The carbonate fracture–vug reservoirs in the Tabei area are geologically situated in the Tabei Uplift—a structural unit in the northern part of China’s largest inland basin, the Tarim Basin (Figure 2 and Figure 3)—with burial depths exceeding 5000 m. This region is bounded by the Tianshan Piedmont and Kuqa Depression to the north, the Tarim River and Manjiaer Depression to the south, and the Kalayuergun Fault and Awati Depression to the west [9,10]. The Tabei Uplift extends approximately 480 km east–west and 70–110 km north–south, with significant structural differences between its eastern and western segments [9,10]. It can be divided into multiple secondary tectonic units, including the Shaxi Uplift, Halahatang Depression, Akequl Uplift, Caohu Depression, and Korla Nose Uplift [9,11,12,13] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Map of structural units of the Tabei Uplift in the Tarim Basin.

The Tabei Uplift is one of the most hydrocarbon-rich tectonic units in the Tarim Basin. Hydrocarbons are mainly distributed in the central and western parts of the uplift, and several 100-million-ton-class large- and medium-sized oil and gas fields (including the Tahe Oilfield) have been discovered so far [14,15]. However, the eastern part of the uplift has achieved relatively few hydrocarbon exploration results, which may be related to the damage caused by tectonic evolution and fault activity [15].

2.1.2. Overview of the Tahe Oilfield

Discovered in 1997 and subsequently put into production, the Tahe Oilfield is located in the central part of the Tabei Uplift. It currently ranks as the second-largest oilfield under the jurisdiction of Sinopec Group and is also China’s first Paleozoic marine 100-million-ton-scale oilfield [15]. The primary production target of this oilfield is the Ordovician carbonate reservoirs, with a burial depth of 5400–6600 m and formation temperatures of 125–150 °C. These reservoirs exhibit strong heterogeneity, with reservoir spaces mainly consisting of karst fractures and structural fractures—among which karst fractures serve as the predominant reservoir space [10,14,16].

After years of exploration and production, the Tahe Oilfield has gained in-depth comprehensive geological insights into paleokarst. This paper takes the Tahe Oilfield as a typical example of marine carbonate paleokarst fracture–vug reservoirs in the Tarim Basin. It systematically examines the karst characteristics of Ordovician carbonate fracture–vug reservoirs in the northern Tarim region from three aspects: the dominant karst periods that control fracture–vug reservoir structure, paleokarst zoning, and the characteristics of reservoir paleokarst systems.

2.2. Major Karstification Periods Controlling the Formation of Fracture–Vug Reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield

The primary karstification periods governing the formation of fracture–vug reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield are the Middle Caledonian Episode III and the Early Hercynian.

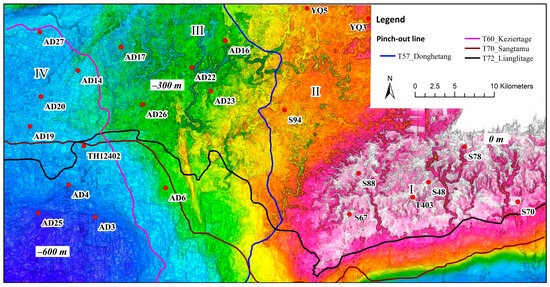

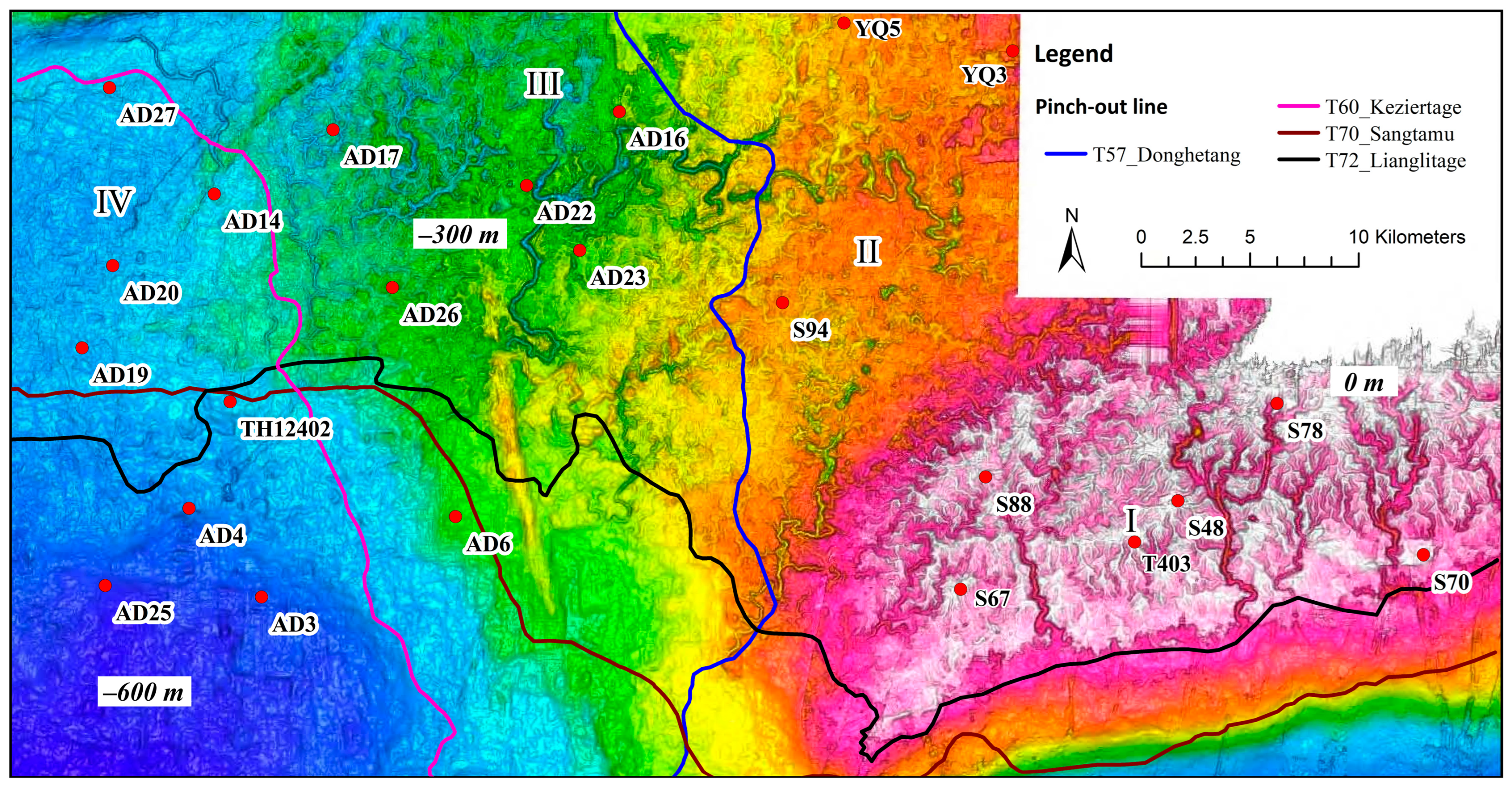

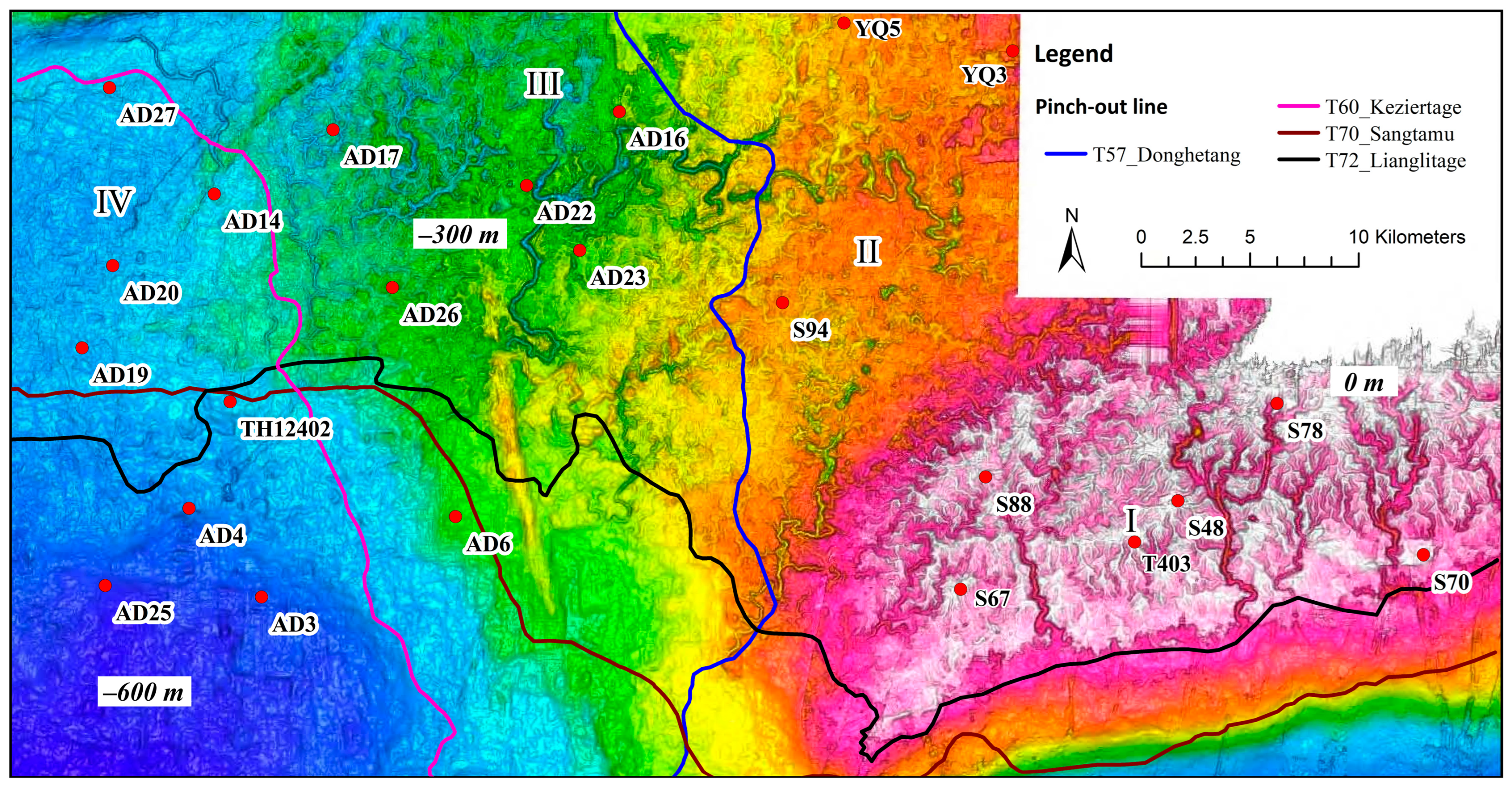

Middle Caledonian Episode III karst is predominantly distributed in the Silurian-covered areas of the western Tahe Oilfield (west of the pinch-out line of the Donghetang Formation, T57) (Figure 4). During this episode, Middle-Lower Ordovician carbonate rocks developed paleo-rivers along the top surface of the Upper Ordovician Santamu Formation mudstone. Under conditions of intense atmospheric precipitation, this led to syndepositional karstification. Additionally, Middle-Lower Ordovician strata north of the Santamu Formation pinch-out line were extensively exposed at the surface, where meteoric freshwater leaching drove significant karst development—particularly in the northwestern part of the Akekule Uplift [17].

The Early Hercynian represents a critical stage for the development of Ordovician fracture–vug reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield. During this period, tectonic activity triggered intense uplift of the Akekule Uplift, forming a regional angular unconformity and re-exposing Middle-Lower Ordovician strata to the surface. Intense karstification driven by meteoric water resulted in the formation of extensive weathering fracture systems and cave reservoirs. Notably, in the mudstone-covered area south of the pinch-out line, karstification—likely facilitated by fault-controlled groundwater circulation—developed high-quality fracture–vug reservoirs along fault zones [17,18].

2.2.1. Distribution of Middle Caledonian Paleokarst Reservoirs

Caledonian paleokarstification predominantly occurred and was preserved in the Upper Ordovician-overlain areas of the southern and southwestern Tahe Oilfield. Although Caledonian karstification was once extensive across the main Tahe Oilfield area, subsequent superimposition and modification by Early Hercynian karstification, combined with complete erosion of the karst host strata above the Caledonian karst erosion base level, have rendered Caledonian karst reservoirs in the main area difficult to identify [19].

The distribution of karst reservoirs is generally controlled by integrated factors including faults, unconformities, and lithology. Consequently, paleokarst reservoirs formed during this stage are specifically distributed in the overlapping zones of paleo-weathering crust denudation belts, Caledonian fault-intensive zones, and reef-shoal facies reservoir development belts. Current exploration data indicate these reservoirs are primarily concentrated at the plunge termination of the Akekule Uplift’s axis and within fault-intensive zones in the southern and southeastern Tahe Oilfield [20].

2.2.2. Distribution of Early Hercynian Paleokarst Reservoirs

The Early Hercynian paleo-karstification process developed three cycles of horizontal karst development, with reservoir distribution exhibiting distinct zoned characteristics. The spatial distribution of different reservoir types is significantly controlled by lithofacies and structural features [21]:

Cave-vug reservoirs are primarily developed within 0–250 m below the unconformity surface in the Ordovician carbonate section; weathering fracture reservoirs are concentrated near the Early Hercynian unconformity erosion surface and around cave layers; structural fracture reservoirs are widely distributed in fault zones.

In the main area of the Tahe Oilfield, Early Hercynian paleokarst first eroded the upper sections of the Middle Caledonian karst host strata, followed by inherited karst evolution. Currently, Early Hercynian paleokarst reservoirs—strongly influenced by tectonic activity—are predominantly concentrated in karst slope zones along the axis of the Akekule Uplift [22].

2.3. Subdivision and Zonation Characteristics of Paleokarst

2.3.1. Heterogeneity in Horizontal Subdivision

Significant differences exist in the scale and genetic mechanisms of paleokarst development between the eastern core area and the western peripheral area of the Tahe Oilfield (Figure 4). The eastern core area is a karst highland, characterized by high-relief landforms (e.g., fengcong karst/peak clusters, karst hills) and intense vertical dissolution–erosion driven by surface runoff. This hydrological process has formed a composite drainage system consisting of dry valleys, blind valleys, and subsurface streams. In contrast, the western peripheral area is a karst depression with gentle topography. Here, lateral dissolution-dominated erosion governs the subsurface drainage system, resulting in low-relief landforms such as fenglin karst hills and meandering subsurface river networks [23,24].

Figure 4.

Karst paleogeomorphology of the early stage of the Hercynian Movement in the Tahe Oilfield (I-Karst plateau; II, III-Karst slope; IV-Karst basin) [25].

Figure 4.

Karst paleogeomorphology of the early stage of the Hercynian Movement in the Tahe Oilfield (I-Karst plateau; II, III-Karst slope; IV-Karst basin) [25].

2.3.2. Vertical Zonality of Paleokarst

Under the synergistic control of soluble rock lithology, tectonic activity, paleogeomorphology, and paleoclimate, distinct paleo-hydrodynamic conditions have led to prominent vertical zoning characteristics of paleokarst [26]. Vertically, the Ordovician carbonate fracture–vug reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield can be divided into four paleokarst zones, each with unique hydrological processes and karst features [27]:

- (1)

- Epikarst zone: Meteoric water primarily flows downslope, developing typical karst landforms such as sinkholes and dissolution furrows. This zone is closely associated with subaerial exposure, with a thickness generally ranging from 5 to 20 m, and its development is strongly constrained by surface paleotopography.

- (2)

- Vadose karst zone: Meteoric water infiltrates the Ordovician limestone through fractures and high-angle joints, driving vertical dissolution. This process forms vertical dissolution cascades, perched aquifer caves (perched water caves), and high-angle dissolution fractures. The zone is characterized by unsaturated water flow, and its thickness is controlled by the local paleo-water table (typically 20 to 80 m).

- (3)

- Phreatic karst zone: Meteoric water converges to form subsurface river systems, consisting of terminal caves, tributary caves, main channel caves, and large chamber caves. Dissolution here is dominated by horizontal water flow, accompanied by predominantly low-angle dissolution fractures and intergranular dissolution vugs. This zone is the primary interval for high-quality fracture–vug reservoir development, as the interconnected cave–conduit systems provide excellent hydrocarbon storage and seepage spaces.

- (4)

- Deep phreatic karst zone: Groundwater migrates via seepage from high-hydraulic-head areas to low-hydraulic-head areas. Due to reduced hydrodynamic intensity and limited carbonate reactivity, dissolution intensity is significantly weakened. Caves in this zone are often filled with sandy–muddy fillings (derived from overlying clastic strata) and authigenic calcite cements, resulting in relatively low effective porosity (generally <5%).

2.4. Characteristics of Paleokarst Systems

The paleokarst system in the Tahe Oilfield is a product of multi-stage tectonic evolution and karstification in the northern Tarim Basin. The overall karst features are characterized by large-scale, deeply buried cave–conduit networks in the eastern core area, whereas the western peripheral area exhibits less intense karstification, smaller reservoir scale, and poorer reservoir connectivity [23,24]. These macroscopic karst geological insights provide critical theoretical support for hydrocarbon exploration and production in the northern Tarim Basin [28,29].

2.4.1. Reservoir Characteristics

The Ordovician paleokarst reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield are characterized by great burial depth, strong reservoir heterogeneity, and complex reservoir space architecture. They are primarily distributed within approximately 250 m below the upper unconformity surface of the Lower Ordovician. Vertically, these reservoirs exhibit distinct vertical zonation, and their distribution is controlled by multiple factors, including paleokarst geomorphology, fracture intensity, and paleoclimate [26,30].

Reservoir development intervals are primarily concentrated in the overlapping zones of paleo-weathering crust denudation belts and Caledonian-aged fault belts—for example, the plunge termination of the Akekule Uplift axis and fault-developed regions in the southwestern and southeastern parts of the Tahe area [28]. The reservoir development exhibits both stratabound and fault-controlled attributes: the stratabound attribute is manifested by extensive yet shallow karstification, concentrated in the 0–35 m interval below the unconformity surface; the fault-controlled attribute is reflected in the distribution of large-scale dissolution vugs and caves along fault belts, where faults act as preferential channels for meteoric water infiltration and dissolution [27,28].

2.4.2. Fracture–Vug System Architecture

The karst fracture–vug system genetically originates from the dissolution of carbonate rocks driven by meteoric water (derived from atmospheric precipitation), manifested as a continuous fluid-conducting network that initiates at sinkholes in karst highlands or karst slopes and terminates at the outlets of subsurface rivers in karst depressions.

By referencing the vertical zoning models of vertical karst hydrodynamic profiles in modern karst regions with homogeneous pure soluble carbonate rocks, the fracture–vug system can be vertically divided into four functional zones: 1. Epikarst zone (encompassing surface runoff and sinkholes); 2. Vadose karst zone (also referred to as the vertical leaching zone); 3. Runoff karst zone (dominated by subsurface river systems); 4. Phreatic karst zone.

The formation and evolution of the fracture–vug system are synergistically controlled by paleotopography, paleo-water table fluctuations, and fault activity during the burial stage [27,31].

By applying high-precision 3D seismic technologies—including fine coherence analysis and amplitude variation rate analysis—and integrating field outcrop data, actual drilling data, and hydrocarbon production dynamic data, the fracture–vug system is classified into three primary categories: (1) the paleokarst residual hill fracture–vug system in the denudation zone; (2) the paleochannel fracture–vug system; (3) the fault-controlled fracture–vug system in the mudstone-covered area. Among these, the paleochannel fracture–vug system is subdivided into surface river-associated and subsurface river-associated subtypes; the paleokarst residual hill fracture–vug system is categorized into four types based on karstification intensity; the fault-controlled fracture–vug system is further divided into three morphological types: banded, sandwich-like, and plate-like.

Reservoir bodies at the junction of paleo-surface rivers and high-amplitude residual hills are characterized by large scales and exhibit “beaded” seismic reflection signatures—making them priority zones for well deployment. Meanwhile, pipeline-type reservoir bodies, formed by the coupling of paleo-subsurface rivers and faults, feature extensive lateral extensions and may host multi-layered dissolution caves [32,33].

2.4.3. Hydrogeomorphic Controls on the Development of Fracture–Vug Systems

During multiple tectonic events in the northern Tarim Basin, differential uplift amplitudes of carbonate blocks between the eastern and western Tahe Oilfield gave rise to distinct karst hydrodynamic regimes, resulting in significant differences in the fracture–vug architectures of the two areas.

The eastern core area of the Tahe Oilfield experienced significant uplift, which drove intense vertical erosion by paleo-surface water systems and the formation of a complete dual surface–subsurface water network. In contrast, the western area underwent minor uplift: paleo-hydrodynamic flow here was dominated by horizontal dissolution-dominated processes, and a continuous subsurface water network has not been established.

The hydrogeomorphic characteristics of the eastern core area reflect a long-term stable phase of karstification, whereas the western area remains in the juvenile phase of karst evolution [23,24].

The subsurface river system is a critical component of the fracture–vug system in the Tahe Oilfield, playing a pivotal role in deciphering the evolution of karst systems and reservoir distribution patterns. Previous studies have focused on four key aspects: (1) controlling factors for subsurface river system development; (2) geological evolution of karst hydro systems; (3) spatial architecture and development characteristics of subsurface river systems; (4) reservoir properties and connectivity of subsurface river-associated reservoirs.

Fracture characterization indicates that the fault system provides preferential dissolution pathways for subsurface rivers and exerts a facilitative role in hydrocarbon charging [34]. The Hercynian tectonic evolution acts as the primary internal dynamic geological driver controlling the karst distribution pattern in the Tahe Oilfield [35].

The paleokarst hydrogeological system in the Tahe Oilfield exhibits distinct hierarchical organization characteristics. Within this region, four secondary karst hydrogeological systems have developed, including karst highland–canyon hydrogeological systems and subsurface river–canyon hydrogeological systems (Zones I, II, and III in Figure 4). The hierarchical structure of these systems serves as critical geological evidence for deciphering the development of fracture–vug systems. Differential discharge and dissolution intensity of the karst hydrogeological systems have shaped diverse karst geomorphological features, such as karst canyons, subsurface rivers, and deeply incised karst meanders [26].

The spatial architecture of the paleokarst conduit system is complex: in plan view, the paleokarst conduits exhibit intricate reticular-dendritic patterns, and vertically, they can be divided into three vertical filling types from top to bottom: unfilled, sandy-mud-filled, and breccia-filled. Such structural characteristics lead to variations in hydrocarbon enrichment and reservoir connectivity across different zones [26,34]. The paleokarst conduit system comprises two primary categories based on hydrodynamic zones: water table conduits, including main trunk conduits, tributary conduits, and abandoned conduits; phreatic loop conduits, including ascending conduits and symmetrical conduits. This classification reflects the system’s diverse geological developmental environments [33,36].

The reservoir space is primarily composed of dissolution pores, vugs, and fractures. High-angle fractures are locally developed, which provide favorable connectivity for the vertical linkage between upper and lower paleokarst subsurface rivers and form an integrated paleokarst subsurface river system [36]. The connectivity of fractures and vugs can be evaluated via the hydrochemical properties of subsurface fluids: zones with good connectivity exhibit similar hydrochemical characteristics in groundwater bodies, whereas disconnected zones show significant hydrochemical differences [37].

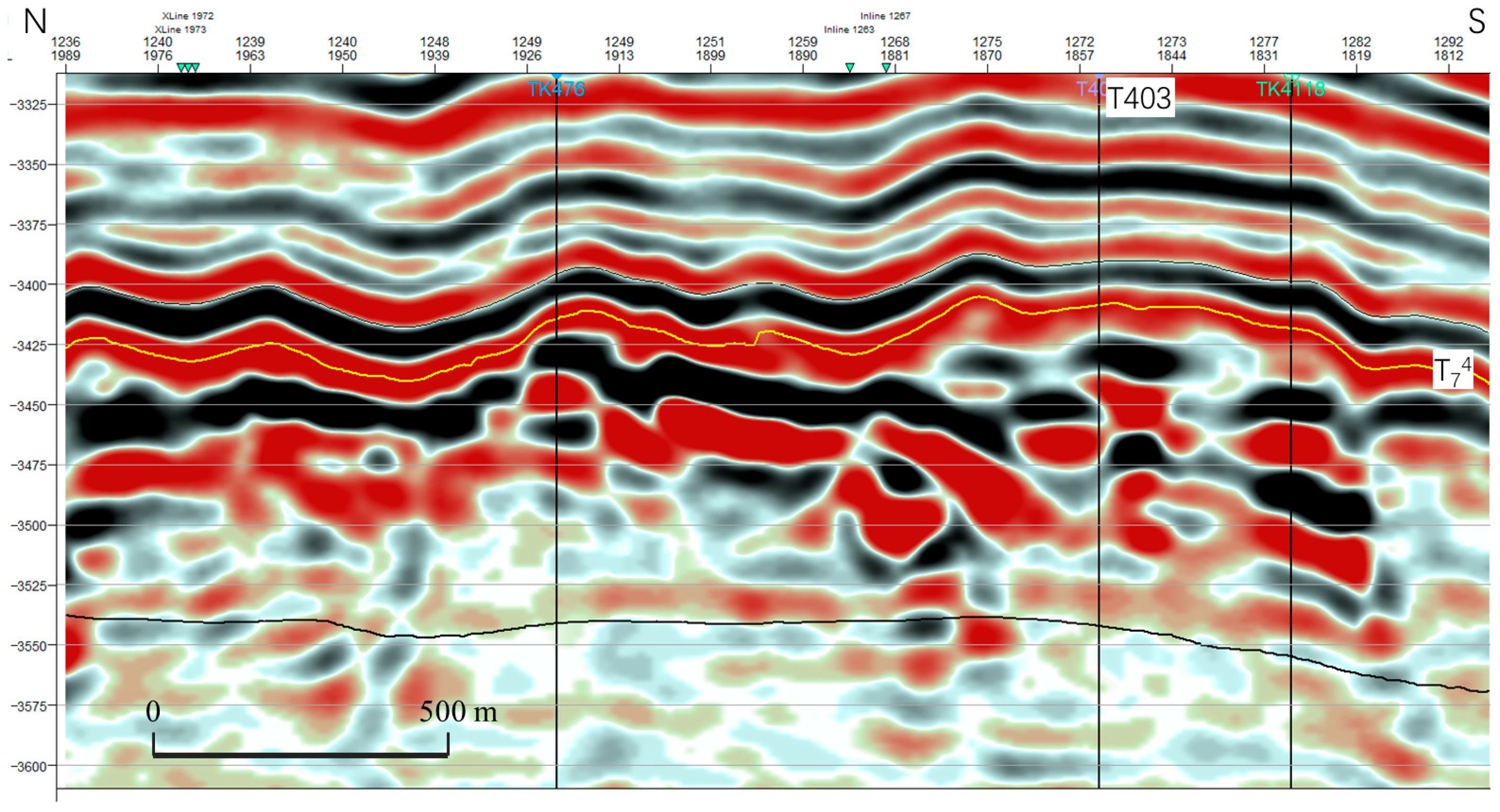

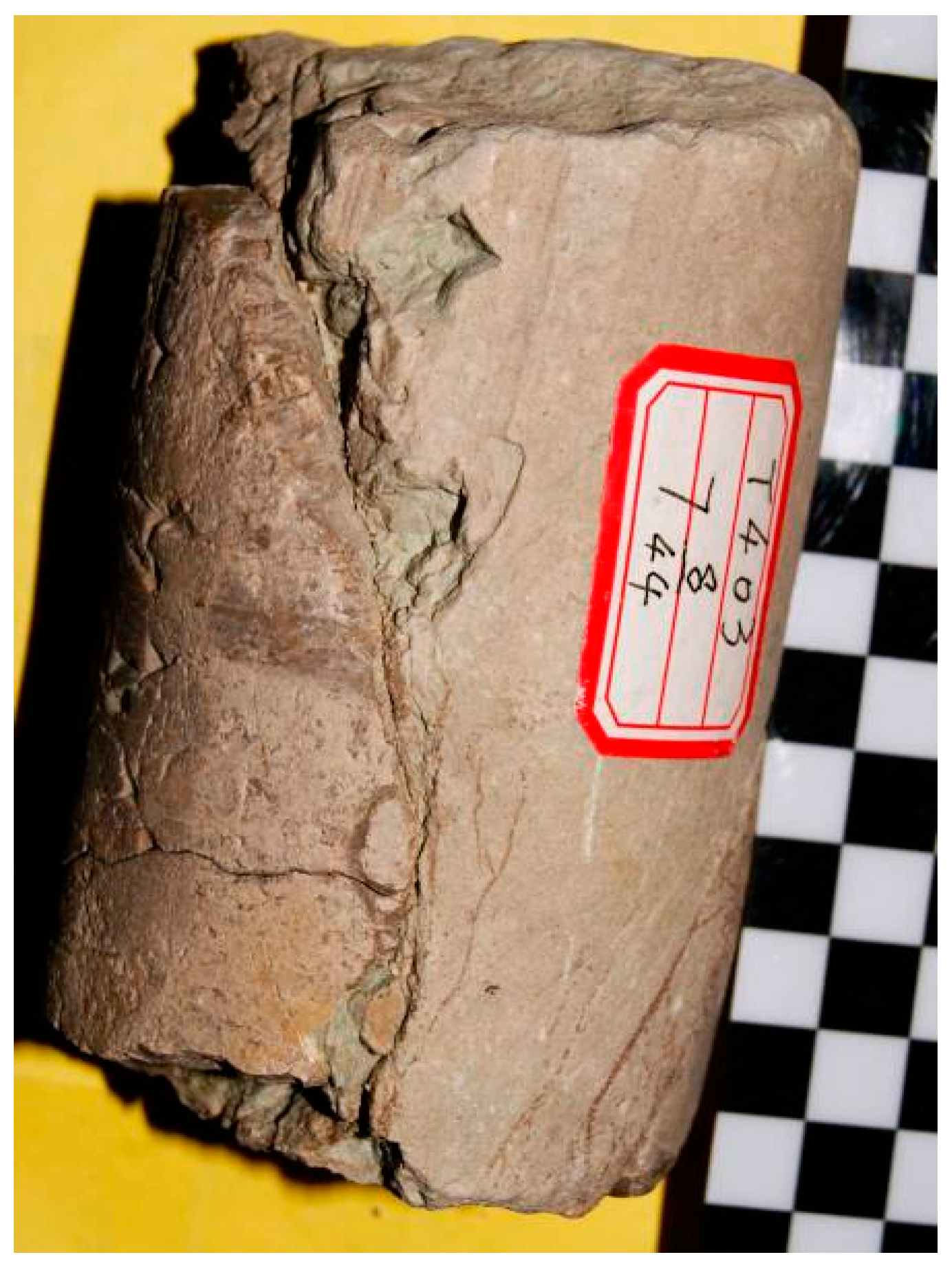

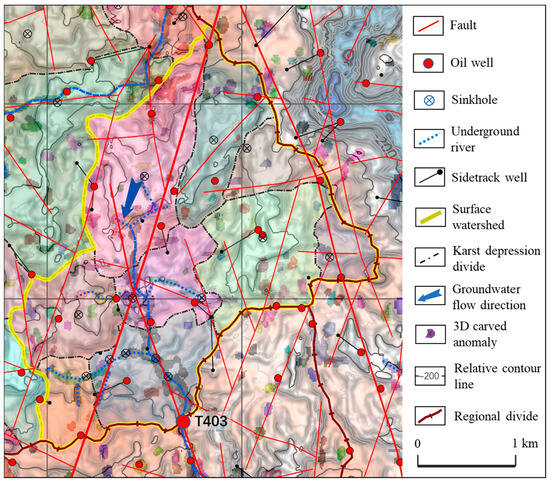

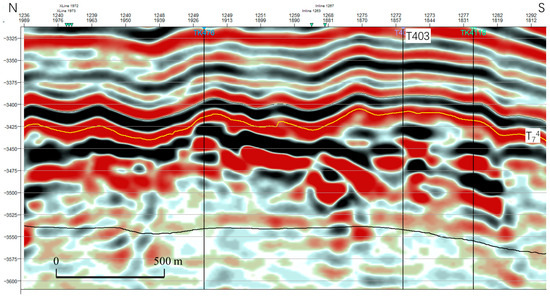

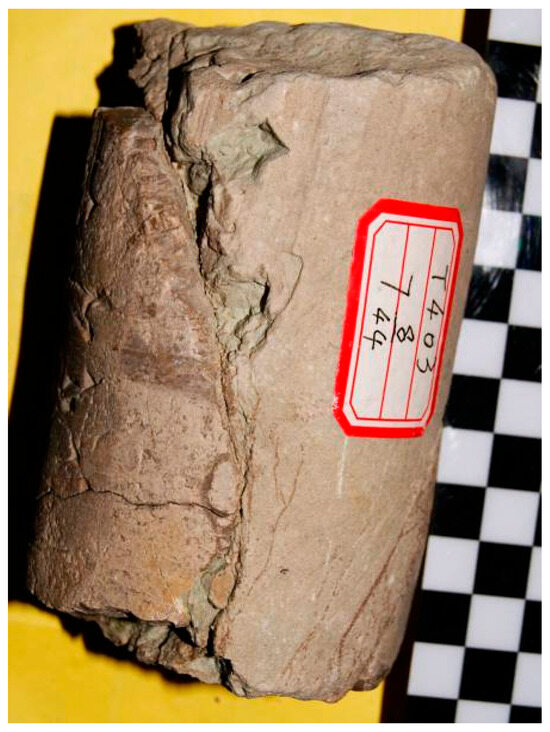

Taking the eastern main area of the Tahe Oilfield as an example, the karst underground river system where Well T403 is located (Figure 4) was identified through paleogeomorphology restoration maps and 3D seismic carving volumes. This paleo-underground river exhibits a dendritic pattern in plan view (Figure 5), and the seismic profiles along the paleokarst underground river show continuous strong reflection characteristics (Figure 6). Logging interpretation results indicate that Well T403 has unfilled and coarse-clastic reservoirs at depths from 5397 m to 5460 m. The filled sandy–muddy materials (Figure 7) are similar to the modern karst cave fillings observed today, thus providing good fracture–vug space for oil and gas accumulation.

Figure 5.

Paleogeomorphology and paleokarst underground river system map of the main area in the Tahe Oilfield.

Figure 6.

Typical seismic profile along the paleo-underground river.

Figure 7.

Argillaceous semi-filled dissolution fracture at 5506.32 m in Well T403.

Overall, although notable advancements have been achieved in the research on paleokarst subsurface river fracture–vug systems in the Tahe Oilfield, future studies should further integrate findings from karst hydrogeological studies of modern karst hydrogeological systems. By integrating key factors including fault systems and paleokarst hydrodynamic conditions, a more in-depth comprehension of the spatial development patterns of paleokarst subsurface river systems can be attained.

3. Characteristics of Karst in China

3.1. Overall Characteristics of Modern Karst in China

As previously noted, the total distribution area of carbonate-bearing strata in China amounts to 3.44 million km2, including 2.06 million km2 of exposed carbonate-bearing strata and 907,000 km2 of exposed carbonate rocks [2]. Compared with Mesozoic carbonate rocks in the European Mediterranean–Alpine region, and Paleogene–Neogene carbonate rocks in Southeast Asia, central Australia, the North American Platform, and the Caribbean region, most carbonate rocks in China belong to pre-Triassic ancient formations. These rocks are characterized by high diagenetic maturity, extremely low porosity, and high mechanical strength [38].

Owing to the extensive distribution of carbonate rocks across diverse environments in China, significant variations in geological conditions and climatic backgrounds give rise to distinct karst hydrodynamic regimes across different regions (Table 1). Consequently, China exhibits a high diversity of karst types. Overall, the most representative karst types on mainland China can be categorized into three primary groups: (1) tropical–subtropical humid-type karst in southern China [39]; (2) arid–semiarid temperate-type karst in northern China [40]; (3) alpine-type karst on the Tibetan Plateau. Among these, the karst regions of southern and northern China are located in eastern China, bounded by the Qinling–Huaihe Line.

Table 1.

Comparison of karst characteristics between northern and southern China [41].

The fracture–vug system in the core area of the Tahe Oilfield formed during the Early Hercynian under humid tropical–subtropical climatic conditions [42]. From the perspective of karst dynamics, the paleokarstification period of the Tahe Oilfield shares similar climatic conditions with the modern karst in southern China. Given the well-developed paleo-subsurface river system in the Tahe Oilfield’s core area, the modern karst in southern China can be used as an analog for paleokarst research in the Tahe Oilfield. The method of inferring ancient conditions using modern analogs is of great significance for paleokarst studies.

3.2. Characteristics of Karst in Southern China

Carbonate rocks are widely distributed in southern China. Influenced by multiple phases of tectonic movements, most carbonate stratigraphic sequences exhibit intense folding and well-developed fractures. Coupled with humid tropical–subtropical monsoon climatic conditions, these sequences have undergone high karstification intensity.

Geological surveys indicate that the Devonian, Permian, and Middle-Lower Triassic carbonate stratigraphic sequences in southern China exhibit the highest karstification intensity [43]. Under the synergistic control of lithology, geological structure, and climatic conditions, complex and diverse karst landforms and karst hydrogeological systems have formed in southern China—characterized by well-developed subsurface river systems, high karstification intensity, and complex karst hydrogeological architectures.

3.2.1. Karst Landform Characteristics

The karst region in southern China is characterized by tropical–subtropical karst landform assemblages, such as peak forest plains and peak cluster depressions. Geographically, from the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the Guangxi Basin, the elevation gradually decreases from approximately 2000 m to below 100 m. Across a horizontal distance of nearly 1000 km, a sequence of karst landform assemblages is distributed from northwest to southeast—including dissolution plateaus, peak cluster depressions, deeply incised valleys, karst hill valleys, and peak forest plains—forming diverse landscape features [44,45].

Individual karst morphologies exhibit high diversity, including stone teeth, stone pillars, stone forests, dissolution flutes, dissolution furrows, dissolution fissures, sinkholes, vertical shafts, dolines, collapse dolines, and karst skylights. These morphologies reflect complex genetic relationships (e.g., dissolution vs. collapse origins) [44,46]. Karst landforms show significant regional variability, particularly between dissolution plateaus and peak forest plains: influenced by tectonic activity, precipitation, and lithology, they exhibit distinct developmental characteristics and spatial distribution patterns [44,45].

The aforementioned karst landform assemblages can be broadly categorized into two primary types: peak forest and peak cluster. The peak forest type includes subtypes such as peak forest valleys, peak forest poljes, peak forest plains, and isolated peak plains. It is characterized by dispersed stone peaks and connected pedestal peaks (in block-, island-, or strip-shaped forms) distributed across relatively flat terrain. The peak cluster type can be subdivided into high-elevation, mid-elevation, and low-elevation peak clusters. It consists of aggregated peak groups with connected pedestals, interspersed with numerous sinkholes, vertical shafts, dolines, depressions, and valleys. Notably, the developmental patterns of subsurface karst rivers vary across different karst landform assemblage zones [47].

Karst development also exhibits distinct vertical zonation, with significant differences in karstification intensity and morphological characteristics among different stratigraphic units. From top to bottom, it can be divided into the epikarst zone, vadose karst zone, runoff karst zone, and phreatic karst zone—this zonation system serves as a critical reference for paleokarst research in the Tahe Oilfield. Among these zones, the epikarst zone is widely developed in southern China’s karst regions: its formation results from intense surface karstification processes, with strong dissolution dynamics and rapid hydrodynamic dissolution being the key controlling factors [48].

3.2.2. Karst Hydrogeological Characteristics

Karstification is highly developed in the karst regions of southern China. Carbonate rocks are widely distributed, predominantly occurring in Sinian to Triassic stratigraphic systems (excluding the Silurian System) with thicknesses of 3000–10,000 m. Under the synergistic control of tectonic movements and abundant precipitation, these rocks undergo intense karstification [43,46]. The carbonate aquifer media primarily consist of dissolution pores, caves, and subsurface river conduits, forming complex network architectures. In areas with well-developed fault structures, subsurface river systems are particularly prominent and exhibit extensive drainage areas [43,45].

The development of karst subsurface rivers is the most distinctive feature of southern China’s karst regions. These rivers are subsurface karst conduits that exhibit the key hydrological characteristics of surface rivers, forming subsurface river systems composed of main streams and tributaries [49]. A large number of karst subsurface river systems have developed in the exposed karst areas of southern China: 3358 systems have been documented, with a dry-season discharge of up to 420 × 108 m3/a. These subsurface river systems are generally controlled by fold and fault structures, maintain close hydrological connections with surface water systems, and exhibit significant dynamic fluctuations in water levels—a sign of active hydrological cycling. Particularly between the rainy and dry seasons, pronounced fluctuations in water level and discharge reflect complex karst hydrodynamic characteristics and hydraulic connectivity [43,50,51].

An intrinsic correlation exists between karst subsurface rivers and karst landform assemblages: specifically, peak cluster mountainous areas are typically development zones for large, complex karst subsurface river systems, whereas peak forest plains primarily host small, simple karst subsurface river systems [47]. This pattern also reflects, to a certain extent, the controlling role of karst hydrodynamic regimes in shaping karst landforms. For example, within the same karst hydrogeological system along the Li River in Guilin, Guangxi, both peak cluster depressions and peak forest plains coexist as karst landscape features; however, significant differences in groundwater storage and flow regimes are observed across these distinct karst landform assemblage zones [47,52].

4. Results

As noted earlier, the vast majority of karst caves and fracture–vug systems worldwide are primarily formed by dissolution and erosion by atmospheric precipitation and its derived surface water and groundwater [53], belonging to a typical epigenetic karst dynamic system origin type. From the perspective of karst dynamics, modern karst in southern China can be compared with the paleokarst system of the Ordovician in the Tahe Oilfield under a hot and humid climate. Moreover, by integrating the geological characteristics of deep reservoirs in the Tarim Basin and multi-source data (such as drilling, logging, seismic, fluid geochemical analysis, etc.), the commonalities and differences between paleo- and modern karst in terms of karst dynamic mechanisms, fracture–vug structures, and structural controls on reservoirs can be clarified.

The fracture–vug systems in the Tahe Oilfield can be classified into three main types: the paleokarst residual hill fracture–vug system in the denudation area, the paleochannel fracture–vug system, and the fault-controlled fracture–vug system in the mudstone-covered area. Due to space limitations, we cannot discuss all types exhaustively. Herein, we focus on the paleochannel fracture–vug system to present the results of the paleo and modern karst comparison of the fracture–vug reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield, as follows:

4.1. Genetic Relationship and Differences Between Paleo- and Modern Karst Dynamic Systems

The formation of paleokarst reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield is controlled by the multi-stage coupling effect of “structure and fluid”. Its core dynamic processes have clear analogies with modern karst, while also possessing the particularities of deep karst. Meteoric freshwater dissolution during the Late Caledonian–Early Hercynian is the main formation cause of paleokarst reservoirs [54]. This process is similar to the “precipitation infiltration—phreatic zone dissolution” mechanism of modern karst in southern China: both take faults and fractures as preferential fluid flow paths, ultimately forming reservoir spaces centered on dissolution vugs and underground river channels, and the effectiveness of reservoirs depends on long-term fluid circulation [55].

However, hydrothermal activity in the Late Hercynian has led to certain differences between the paleokarst in the Tahe Oilfield and modern epigenetic karst [54]. These differences are mainly reflected in the upwelling of hydrothermal fluids carrying acidic components such as CO2 and H2S along strike-slip faults, which on the one hand expanded early fractures and vugs, and on the other hand caused calcite and quartz filling [55], forming a complex evolution of “dissolution—modification—filling”. As a result, the heterogeneity of paleokarst reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield (e.g., porosity 1~3.1%, permeability 0.002~1.52 mD) is higher in some areas than that of modern karst [9,10]. Nevertheless, due to the limited scale of circulation of these deep hydrothermal fluids, the main framework of fracture–vug reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield is still controlled by the paleo-epigenetic karst dynamic system.

4.2. Paleo- and Modern Underground Rivers Show Consistency in Morphology and Structure

The Ordovician paleo-underground river systems in the Tahe Oilfield share morphological similarities with modern karst underground rivers. In the Swabian Alb carbonate aquifer, Germany, modern phreatic loop underground rivers develop within 50 m below the water table, forming continuous tunnels along NW-SE trending faults. These tunnels exhibit a “U”-shaped cross-section and a three-segment structure of descending–horizontal–ascending [26,33]. This three-segment cave structure is also found in the Bilian Cave system in Yangshuo County, Guilin, Guangxi, China.

Similarly, in the Tahe S67 well area, phreatic zone underground rivers develop ascending and symmetric reflux structures. The ascending underground rivers have horizontal phreatic channels in the deep part, with a horizontal segment length of 1–1.5 km and an upward tunnel dip angle of 8°. The symmetric underground rivers have a complete descending (dip angle of 26°), horizontal (length of 1.78 km), and upward loop, with a total length of 4.8 km [33]. Both demonstrate the control of fracture networks on the trend of underground rivers, and the formation of phreatic loops is closely related to hydraulic gradients.

The Bullita Cave system in the Judbarra region, Australia, is a typical epigenetic karst diffusive infiltration maze structure. Restricted by the underlying shale aquiclude, it develops near-horizontal grid-like tunnels, presenting a closed-loop network without a main trunk in the plane. The maze-type paleo-underground river system in the Lianglitage Formation of Tahe Block 11 is affected by the Qiaerbake Formation mudstone aquiclude, forming closed pipelines along NNE and NW trending faults. On seismic profiles, it shows short and strong peak-trough reflection events, with a single cave height of up to 5.26 m [56]. Both reflect the constraint of the “soluble layer—aquiclude” superimposed structure on the lateral expansion of underground rivers, confirming that the sedimentary lithological association is the fundamental controlling factor of underground river morphology.

4.3. Control of Structural–Hydrodynamic Coupling on Reservoir Formation and Connectivity

The types of fault-controlled paleokarst systems in the Tahe Oilfield show a high degree of consistency with the spatial differentiation patterns of dissolution spaces observed in modern karst areas of southern China [55]. “U-shaped fault-karst systems” can be compared to the large cave clusters found at modern fault intersection zones. Their formation requires faults to provide long-term water-conducting pathways and sufficient dissolution time. “Layered fault-karst systems” correspond to the bedding-parallel dissolution zones of modern interstratal karst, controlled by lithological differences (e.g., limestone and marl interbedding), resulting in layered distribution of dissolution spaces. “V-shaped” and “complex” systems reflect the combined control of faults and stratum interfaces under the tectonic stress field, which is consistent with the geological modeling results of the Ordovician reservoirs in the northern Tarim Basin [57].

The distance from the fault zone exerts a consistent control law on reservoir spaces between paleo- and modern times: in the paleokarst of the Tahe Oilfield, the near-fault zone (<100 m) is dominated by caves, the mid-distance zone (100~300 m) by fracture–vugs, and the far-fault zone (>300 m) by small dissolution pores [55]. This is fully consistent with the spatial differentiation pattern of “fault-core dissolution zone—transitional dissolution zone—weak dissolution zone” in modern southern karst, indicating that faults play a dominant control role in dissolution space development.

In addition, the development of modern karst underground rivers is not only related to regional tectonic uplift but also closely linked to water circulation constrained by structural conditions. In the Jiudongtian modern canyon, Guizhou Province, China, the underground river system experienced roof collapse due to crustal uplift, forming an evolutionary sequence of “surface river—underground river—open river”. The combination of sinkholes and natural bridges in the knickpoint underground river section reflects the rapid decline in the karst erosion base level [58]. In the Middle-Lower Ordovician of Tahe Block 12, the curvature of paleo-incised meanders ranges from 2.20 to 10.51, and the curvature of the SN-trending meander belt is 1.87. Meander cores and natural bridges formed by cut-off are developed. Their evolution is driven by Early Hercynian tectonic uplift, and the decline in the base level prompted the surface water system to incise downward and transform into underground rivers [59]. Both confirm that tectonic movements drive the vertical dissolution of underground rivers by changing the base level of erosion. However, due to multi-stage tectonic superposition, the structure of paleokarst underground rivers is more complex.

In terms of the hydrodynamic system, the modern underground river in Luota, Hunan Province, China, features an independent recharge–runoff–discharge system. Surface water converges into the underground river through sinkholes, forming a dendritic network [60]. Similarly, the underground river system in the YQ5 well area of the Tahe Oilfield exhibits dendritic convergence, with a main underground river 6.9 km long and dendritic tributary underground rivers flowing into the main trunk. Surface dry valleys are connected to the underground river via sinkholes [26,61]. The difference between the two lies in that the hydrodynamic field of modern underground rivers is controlled by the current landform, while the hydrodynamic system of the paleo-underground river in the Tahe Oilfield experienced base-level migration due to tectonic uplift, which may have led to the abandonment or modification of some underground river sections.

In terms of reservoir connectivity, the connectivity of paleokarst reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield is mainly controlled by fault orientation and the current in situ stress direction [54,55]. The current maximum horizontal principal stress is in the NE–SW direction. NE-trending faults, being parallel to the stress direction, exhibit high fracture aperture (width: 2.0~2.5 mm) and good connectivity. In contrast, NW-trending faults, nearly perpendicular to the stress direction, show high fracture closure (width: 0.5~1.0 mm) and poor connectivity [55]. This pattern is consistent with the characteristic of “fractures parallel to the regional stress direction being more prone to developing dissolution channels” observed in modern karst areas of southern China.

Furthermore, the structural position of strike-slip faults also influences connectivity. In the Tahe Oilfield, the extensional–torsional segments of extensional faults have better connectivity than pure strike-slip segments, while compressional–torsional segments exhibit the poorest connectivity [54]. This aligns with the mechanism in modern strike-slip faults where extensional segments form wide fractures due to tensile forces, facilitating fluid circulation. This partially confirms that paleo- and modern karst share commonalities in terms of connectivity controlled by geological structures.

4.4. Comparison of Filling Mechanisms and Paleo-Modern Differences in Reservoir Spaces

The filling degree of modern karst underground rivers is significantly lower than that of paleo-underground rivers. In Guilin, Guangxi, the filling rate of modern phreatic zone caves is only 15–20%, with fillings mainly composed of chemically deposited travertine, and a large number of unfilled tunnels remain [60]. In contrast, the filling rate of underground river caves in the karst hill valley area of the Tahe Oilfield reaches 86.8%, with fillings dominated by argillaceous sandstones and collapse breccias transported by surface rivers, and only 23.2% of the tunnels are unfilled [56,60]. This difference stems from the multi-stage tectonic compression and epigenetic modification of paleo-underground rivers during the Caledonian—Hercynian periods. For example, a 51 m fully filled underground river cave drilled by Well YQ3 exhibits horizontal bedding and sliding deformation structures in the fillings, indicating a multi-stage sedimentary filling process [33].

The differences in reservoir space types between paleo and modern times significantly influence petrophysical properties. In the modern underground river of Luota, Hunan, the effective reservoir spaces are dominated by unfilled karst caves with a porosity of 25–30% [60]. In the karst hill highland area of the Tahe Oilfield, the paleo-underground river fracture–vug system has a filling rate of 36%, with reservoir spaces consisting of small to medium fracture–vugs and dissolution pores, showing a porosity of 12–18%. Moreover, the reservoir thickness is positively correlated with fracture density [33].

Additionally, in the paleokarst basin area of the Tahe Oilfield, fault–karst breccias developed along faults are filled with fault breccias and travertine, with intergranular pores serving as the main reservoir spaces. These can be buried as deep as 600 m below the weathering crust [61]. In contrast, modern underground rivers are typically buried at depths less than 200 m, indicating that burial depth has a significant impact on the types of fillings and the preservation of reservoir spaces.

5. Discussion

5.1. Practical Value of Paleo-Modern Karst Comparison for Deep Reservoir Exploration in the Tahe Oilfield

Paleo-modern karst comparison provides an operational analog framework for predicting deep fracture–vug reservoirs in the Tarim Basin, addressing the challenge of “disconnection in Paleo-modern karst analogy” [54]. On the one hand, the “fault intersection zone-phreatic zone” dissolution hotspots in modern karst of southern China can be directly analogized to predict high-quality reservoir development areas in the Tahe Oilfield [55]. On the other hand, the vertical dissolution zoning of modern karst (epikarst zone–vertical percolation zone–phreatic zone) can guide the vertical evaluation of paleokarst reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield. Combined with formation rock mechanics analysis [57], the high-brittleness strata in the Lower Member of the Yingshan Formation (calcite content > 80%, brittleness index > 0.6) correspond to the modern easily soluble pure limestone segments, serving as the main development horizons for paleokarst reservoirs and providing a basis for horizon optimization in well deployment.

Furthermore, volume development practices from the frontline of fracture–vug oilfield development have verified the effectiveness of this analogy. In a wellblock of the Tahe Oilfield predicted based on paleo-modern comparison, horizontal wells crossing NE-trending fault-controlled fracture–vug zones achieved stable single-well oil production of 75 t/d, confirming the exploration guiding value of paleo-modern karst comparison [62].

5.2. Complexity of Paleokarst Evolution Driven by Multi-Agent Superposition

Unlike modern epigenetic karst, which is dominated by single meteoric freshwater dissolution, the Tahe paleokarst experienced multi-stage evolution characterized by “structure-controlled pathways, fluid-controlled dissolution, and hydrothermal-controlled reformation” [54,55]. This complexity makes the reservoir more intricate than modern karst systems. During the Caledonian period, strike-slip faults formed the initial fracture network. In the Early Hercynian epoch, meteoric freshwater dissolution along these fractures created underground river systems. In the Late Hercynian epoch, hydrothermal fluids caused further expansion and filling of fractures and vugs. This multi-agent superposition resulted in the interdistribution of effective spaces and fillings within the reservoir. Accurate identification of effective reservoirs therefore requires combined fluid inclusion thermometry and carbon–oxygen isotope analysis [55].

This suggests that future paleokarst research needs to break through the limitations of traditional modern karst analogy and establish a coupled model of tectonic evolution, fluid activity, and hydrothermal reformation. In subsequent studies, important research directions will include investigating the influence of tectonic deformation on organic matter structure, further analyzing the control of strike-slip fault slip rate on dissolution rate, and improving the dynamic evolution mechanism [63].

5.3. Current Research Limitations and Suggestions

According to the literature, the limitations in current research are mainly reflected in the following:

Firstly, unquantified temperature–pressure environment differences: The ultra-deep reservoirs in the Tahe Oilfield (burial depth > 6000 m, T > 120 °C) have significant temperature–pressure differences compared with modern surface karst, making it difficult to accurately analogize hydrothermal dissolution intensity. Future research should quantify the relationship between pore fractal dimensions and dissolution rates under different temperature–pressure conditions through high-temperature and high-pressure dissolution experiments combined with fractal methods.

Secondly, lack of micro-scale pore comparison: Fractal analysis of shale pores can be extended to carbonate rocks [64]. By comparing the fractal dimensions of micro-pores in ancient and modern karst, the influence of microscopic heterogeneity on seepage can be quantified.

Thirdly, insufficient dynamic evolution models: Dynamic data from oilfield development can be integrated to establish a dynamic coupling model of structure–fluid–reservoir [62], thereby improving prediction accuracy.

In the future, an integrated technical system of modern karst analogy–3D seismic carving [54]–reservoir sweet spot prediction can be constructed. Constrained by modern karst laws, parameters such as fault scale, in situ stress, and brittle strata can be input to achieve the leap from qualitative analogy to quantitative prediction, providing theoretical support for ultra-deep oil and gas development in the Tarim Basin.

6. Conclusions

Research on deep and ultra-deep fracture–vug reservoirs in the northern Tarim Basin, represented by the Tahe Oilfield, holds great significance for the advancement of karstology. Modern epigenetic karst, exemplified by karst in southern China, provides geological models for studying paleokarst fracture–vug reservoirs in deep and ultra-deep formations. Conversely, paleokarst research can also promote the development of karstological theories. The geological method of “ the present is the key to the past “ offers important insights for paleokarst studies.

In the exploration and development of marine carbonate oil and gas, high-precision 3D seismic technology serves as the methodological foundation for investigating the developmental patterns of paleokarst fracture–vug reservoirs. Combined with karst geological theories, it has given rise to the methodological framework of seismic paleo-karstology. Among these, numerous modern karst fracture–vug pattern samples from Southern China are the foundation for interpreting seismic data into paleokarst geological models. Seismic exploration techniques and karst geological theories complement each other, further deepening our geological understanding of karst occurrence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z.; methodology, C.Z. and D.X.; software, Y.D. and Q.Z.; formal analysis, C.Z. and Y.D.; investigation, D.W.; data curation, Y.D. and Q.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z. and D.X.; writing—review and editing, C.Z. and Q.Z.; visualization, Y.D. and D.W.; supervision, C.Z. and D.X.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was sponsored by the Open Fund Project entitled “Multi-Scale Fracture-Vug Structure Characterization of Deep Reservoirs Based on Modern Karst” of Key Laboratory of Marine Oil & Gas Reservoirs Production, SINOPEC (33550000-22-ZC0613-0304); Guizhou Provincial Major Scientific and Technological Program ([2024]013); the National Key R & D Program of China (2016YFC0502300); the National Science Foundation of China (U1612441); the High-Level Talent Introduction Program for the Guizhou Institute of Technology (2023GCC085); the Guizhou Provincial Key Technology R&D Program (QKHZC(2023)-General 143); and the Provincial Higher Education Teaching Content and Curriculum System Reform Project of Guizhou Province (2023223).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Dongling Xia and Yue Dong were employed by the company China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation Limited. The authors declare that this study received funding from SINOPEC. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Goldscheider, N.; Chen, Z.; Auler, S.A.; Bakalowicz, M.; Broda, S.; Drew, D.; Hartmann, J.; Jiang, G.H.; Moosdorf, N.; Stevanovic, Z.; et al. Global Distribution of Carbonate Rocks and Karst Water Resources. Hydrogeol. J. 2020, 28, 1661–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.T.; Luo, Y. Measurement of Carbonate Rocks Distribution Area in China. Chin. Karst 1983, 2, 147–150. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.Z.; Qin, X.Q.; Cao, J.H.; Jiang, X.Z.; He, S.Y.; Luo, W.Q. Calculation of Atmospheric CO2 Sink Formed in Karst Processes of the Karst Divided Regions in China. Chin. Karst 2011, 30, 363–367. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Song, J.M.; Zhou, G.; Sun, P.; Wang, D.C. Characteristics of Marine Carbonate Hydrocarbon Reservoirs in China. Front. Geosci. 2008, 15, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Loucks, R.G. Paleocave Carbonate Reservoirs: Origins, Burial Depth Modifications, Spatial Complexity, and Reservoir Implications. AAPG Bull. 1999, 83, 1795–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, R.G. A Review of Coalesced, Collapsed-Paleocave Systems and Associated Suprastratal Deformation. Acta Carsolog. 2007, 36, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.L.; Loucks, R.; Janson, X.; Wang, G.Z.; Xia, Y.P.; Yuan, B.H.; Xu, L.G. Three-Dimensional Seismic Geomorphology and Analysis of the Ordovician Paleokarst Drainage System in the Central Tabei Uplift, Northern Tarim Basin, Western China. AAPG Bull. 2011, 95, 2061–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Liu, Q.; Li, H.Y.; Deng, G.X.; Peng, J. Theory and Application of Seismic Palaeokarst. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 35, 9–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.Y.; Li, J.H.; Zhao, X. Paleozoic Structural Styles and Evolution of the North Tarim Uplift. Geol. China 2009, 36, 314–321. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.B.; Cui, W.J.; Tao, X.W.; Dong, H.K.; Xu, Z.H.; Li, T.T.; Chen, X.Y. Structural Characteristics and Evolution Process of Faults in the Lunnan Low Uplift, Tabei Uplift in the Tarim Basin, NW China. Nat. Gas. Geosci. 2020, 31, 647–657. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.T.; Hao, J.M.; Wang, X.L. Reservoir Characteristics and Controlling Factors of Lower-Middle Ordovician Yingshan Formation in Tahe Area. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2022, 52, 348–362. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.L. Comparison of Reservoir Geological Conditions of Ordovician Carbonatite Between Tazhong and Tabei Palaeohighs. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2014. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- An, H.T.; Li, H.Y.; Wang, J.Z.; Du, X.F. Tectonic Evolution and Its Controlling on Oil and Gas Accumulation in the Northern Tarim Basin. Geotecton. Metall. 2009, 33, 142–147. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. Geological Architecture and Tectonic Evolution in the Eastern Segment of the Tabei Uplift. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Compil. Comm. of the Tarim Oil & Gas Region (SINOPEC). Petroleum Geology of China, 2nd ed.; Pet. Ind. Press: Beijing, China, 2022; Volume 20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.H. Analysis about Oil-Water Distribution in Ordovician Buried Hill Reservoir, Tahe Oilfield. Nat. Gas. Geosci. 2009, 20, 425–428. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.T.; Zhang, D.J.; Yang, Y.C. Stages of Paleokarstic Hypergenesis in Ordovician Reservoir, Tahe Oilfield. Geol. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2009, 28, 71–75+83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liao, M.G.; Pei, Y.; Chen, P.Y.; Liu, X.L.; He, J. Formation and Controlling Factors of Karst Fracture-Cave Reservoir in the 4th Block of Tahe Oilfield. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 35, 51–58. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. Quest for Distribution Rule of Ordovician Carbonate Karst Fractural-Cavern Reservoir Development in Tahe Oilfield. Inner Mongolia Petrochem. Ind. 2011, 37, 262–268. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.G.; Zhang, T. Ordovician Caledonian Karst and Reservoir Distribution Prediction in Tahe Oilfield. In Proceedings of the 2nd Annual Conference China Petroleum Geophysical, Beijing, China, September 2006; Petroleum Geology Committee of China Petroleum Society, Veterinary Geology Committee of Geological Society of China, Eds.; Pet. Ind. Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 133–139. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.B.; Han, Z.H.; Li, Y.H. Reservoir Characteristics and Formation Mechanisms of the Ordovician Carbonate Pools in the Tahe Oilfield. Geol. Rev. 2002, 48, 619–626. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. The Research on Characteristics of Ordovician Palaeokarst and Reservoir in Tahe Oilfield [Dissertation]. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2007. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.B.; Gao, B.Y.; Chen, S.M. Study on Characteristics of Paleokarst Reservoir in Lower Ordovician Carbonate of the Tahe Oilfield. Miner. Rocks 2008, 28, 87–92. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Lu, X.B.; Cai, Z.X.; Zhang, H. Hydrogeomorphologic Characteristics and Its Controlling on Caves in Hercynian, Tahe Oilfield. Acta Pet. Sin. 2016, 37, 1011–1020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.B.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.; Cai, Z.X.; Li, D.Z. Hydrogeomorphologic Characterization and Evolution of the Early Hercynian Karstification in Tahe Oilfield, the Tarim Basin. Oil Gas. Geol. 2016, 37, 674–683. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.J.; Yang, D.B.; Lu, Y.P.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Ding, L.M. Division and Characteristics of Karst Water System in Early Hercynian Movement in Tahe Oilfield, Tarim Basin. Pet. Geol. Xinjiang 2023, 44, 646–656. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Jin, Q.; Zhong, J.H.; Zou, S.Z. Karst Zonings and Fracture-Cave Structure Characteristics of Ordovician Reservoirs in Tahe Oilfield, Tarim Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2016, 37, 289–298. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Cai, X.Y. Caledonian Paleo-Karstification and Its Characteristics in Tahe Area, Tarim Basin. Acta Geol. Sin. (Engl. Ed.) 2007, 81, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, X.X.; Yun, L. Review of Geological Characteristics and Exploration Ideas of Tahe Large Oilfield in Tarim Basin. Oil Gas. Geol. 2008, 29, 565–573. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Z.H. The Karst Palaeogeomorphology of Carbonate Reservoir in Tahe Oilfield. Pet. Geol. Xinjiang 2006, 27, 522–525. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.M.; Zhang, J.J. Early Hercynian Karst Reconstruction and Ancient Landform Recovery: Take Area 2 in Tahe Oilfield as an Example. Geol. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2015, 34, 51–56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.G.; Lu, X.B. Characterization and Classification of Carbonate Fractured-Cavity Reservoirs in Tahe Oilfield. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Oil and Gas Field Exploration and Development, Xi’an, China, 20–21 September 2015; Xi’an Shiyou University, Shaanxi Pet Society, Eds.; Sinopec Northwest Oilfield Branch, Xi’an Huaxian Network Information Service Co., Ltd.: Xi’an, China, 2015; pp. 1041–1050. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.J.; Jiang, L.; Wen, H.; Lu, J.; Chang, Q. Development Characteristics of Ordovician Ancient Subterranean River System in Thrust Anticline Area of Tahe Oilfield, Tarim Basin. Pet. Explor. Geol. 2024, 46, 333–341. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Bao, D.; Yang, M.; He, C.J.; Deng, G.X.; Zhang, H.T. Analysis on Fracture-Cave Structure Characteristics and Its Controlling Factor of Palaeo-Subterranean Rivers in the Western Tahe Oilfield. Pet. Geol. Oil Recov. 2018, 25, 33–39. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.L.; Kang, Z.H.; Yuan, L.L.; Chen, C.H.; Yang, Y.D. Analysis of Characteristics and Causes of Karst in Tahe. Coal Technol. 2015, 34, 131–133. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Li, X.B.; Tan, T.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.G.; Zang, Y.X. Remaining Oil Distribution and Potential Tapping Measures for Palaeo-Subterranean River Reservoirs: A Case Study of TK440 Well Area in Tahe Oilfield. Reserv. Eval. Dev. 2020, 10, 43–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R.; Lou, Z.H.; Lu, X.B.; Jin, A.M.; Su, D.Y. Chemical Characteristics of Underground Water and Development Performance of Fracture-Cave Units in Tahe Oilfield. Acta Pet. Sin. 2019, 40, 567–572. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, D.X.; Zhu, D.H.; Weng, J.T.; Zhu, X.W.; Han, X.R.; Wang, X.Y.; Cai, G.H.; Zhu, Y.F.; Cui, G.Z.; Deng, Z.Q. Karstology of China; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1994. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xia, R.Y. Investigation and Evaluation of Groundwater Resources in Karst Mountainous Areas of Southwest China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.P. The Problems of Karst Groundwater Environment and Its Protection in North China; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2013. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.Q.; Liang, X.; Jin, M.G.; Wan, L.; Yu, Q.C. Fundamentals of Hydrogeology; BGeological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2011. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, C.; Li, Z.J.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.Y. Early Paleozoic Tropical Paleokarst Geomorphology Predating Terrestrial Plant Growth in the Tahe Oilfield, Northwest China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 122, 104674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.X. Some Experiences in Compiling Hydrogeological Maps of Karstic Terrains in China. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 1988, 15, 29–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xia, R.Y.; Zou, S.Z.; Tang, J.S.; Liang, B.; Cao, J.W.; Lu, H.P. Technical Key Points of 1:50,000 Hydrogeological and Environmental Geology Surveys in Karst Areas of South China. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2017, 44, 599–608. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.P.; Zhang, F.W.; Zhao, C.H.; Xia, R.Y.; Liang, B.; Chen, H.F. Differences Between Southern Karst and Northern Karst Besides Scientific Issues That Need Attention. China Min. Mag. 2018, 27 (Suppl. S2), 317–319. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F. Progress in Comprehensive Investigation of Hydrogeological Environmental Geology in Karst Area. World Nonferrous Met. 2018, 22, 224 + 226. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.Q.; Fang, R.J.; Yu, Y.H. Complex Water Movement in Underground River System in South China Karst Area. J. Guilin Univ. Technol. 2010, 30, 507–512. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.C. Features of Epikarst Zone in South China and Formation Mechanism. Trop. Geogr. 1988, 18, 322–326. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yi, L.X.; Xia, R.Y.; Wang, Z. Detection and Evaluation of Karst Subsurface Rivers; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018; p. 241. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.R.; Zhang, F.E.; Liu, C.L.; Tong, G.B.; Zhang, Y. Karst Water Resources in Typical Areas of China and Their Eco-Hydrological Characteristics. Acta Geosci. Sin. 2006, 5, 393–402. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.J.; Hao, A.B.; Cui, Y.L. Review the Feature and Resource Evaluation Methods for Karst Groundwater in North China. In Geological Environmental Protection for Geological Disaster Prevention, 30th Anniversary of the Establishment of the Chinese Institute of Geological Environment Monitoring, 2004; China Land Press: Beijing, China, 2004; pp. 100–104. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.W. New Considerations on Characteristics and Evolution of Fenglin Karst. Chin. Karst 2015, 34, 4–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ford, D.; Williams, P.W. Karst Hydrogeology and Geomorphology; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2007; p. 576. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.B.; Song, Y.C.; Han, J.; Han, J.F.; Yao, Y.T.; Huang, C.; Zhang, Y.T.; Tan, X.L.; Li, H. Control of Structure and Fluid on Ultra-Deep Fault-Controlled Carbonate Fracture-Vug Reservoirs in the Tarim Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.B.; Wang, G.W.; Li, Y.H.; Bai, M.M.; Pang, X.J.; Zhang, W.F.; Zhang, X.M.; Wang, Q.; Ma, X.J.; Lai, J. Fault-Karst Systems in the Deep Ordovician Carbonate Reservoirs in the Yingshan Formation of Tahe Oilfield, Tarim Basin, China. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 231, 212338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.J.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Q.Y.; Ma, X.J. Characteristics of Maze Karst Cave System in Lianglitage Formation of Tahe Oilfield, Tarim Basin. Pet. Geol. Xinjiang 2024, 45, 522–532. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ni, X.F.; Shen, A.J.; Pan, W.Q.; Zhang, R.Z.; Yu, H.F.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, Y.F.; Wang, C.F. Geological Modeling of Excellent Fracture-Vug Carbonate Reservoirs: A Case Study of the Ordovician in the Northern Slope of Tazhong Palaeouplift and the Southern Area of Tabei Slope, Tarim Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2013, 40, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.J.; Lv, Y.P.; Ma, H.L.; Geng, T.; Zhang, X. Fracture-Cave System in Collapsed Underground Paleo-River with Subterranean Flow in Karst Canyon Area, Tahe Oilfield. Pet. Geol. Xinjiang 2023, 44, 9–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.J.; Deng, G.X.; Wang, Z.; Wen, H.; Ma, H.L. Development Characteristics and Genetic Evolution of Carbonate Karst Ancient River: Example from the Middle-Lower Ordovician in Block-12 of Tahe Oilfield, Tarim Basin. Northwest Geol. 2024, 57, 150–160. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Karst Facies Analysis of Ordovician Carbonate in Tahe Area, Tarim Basin. Bachelor’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.J.; Yang, D.B.; Jiang, L.; Jiang, Y.B.; Chang, Q.; Ma, X.J. Characteristics and Origin of Over-Dissolution Residual Fault-Karst Reservoirs in the Northern Tahe Oilfield, Tarim Basin. Oil Gas. Geol. 2024, 45, 367–383. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, F.Z. Practice and Knowledge of Volumetric Development of Deep Fractured-Vuggy Carbonate Reservoirs in Tarim Basin, NW China. Petrol. Explor. Develop. 2019, 46, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.J.; Ju, Y.W.; Lu, Y.J.; Yang, M.P.; Feng, H.Y.; Qiao, P.; Qi, Y. Natural Evidence of Organic Nanostructure Transformation of Shale During Bedding-Parallel Slip. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2025, 137, 2719–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.P.; Pan, Y.Y.; Feng, H.Y.; Yan, Q.; Lu, Y.J.; Wang, W.X.; Qi, Y.; Zhu, H.J. Fractal Characteristics of Pore Structure of Longmaxi Shales with Different Burial Depths in Southern Sichuan and Its Geological Significance. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).