Abstract

A prominent development in environmental engineering and water resource management is the growing adoption of the term “One Water,” which encompasses all categories of water. In practical terms, One Water Concept (OWC) suggests that some municipalities could benefit from combining their traditionally separate water supply and wastewater divisions into a single, unified department. This integration is believed to enable more strategic, efficient, and economically viable approaches to addressing future water challenges. The OWC promotes an integrated approach to water resource management, emphasizing the interconnectedness of water systems and the need for holistic governance. The focus of this paper is on an examination of the implementation of OWC in Greece based on an analysis of recent international case studies, and the identification of the methodological and epistemological challenges. Through critical engagement with current literature and policy frameworks, the study highlights the successes and obstacles in adopting OWC, offering insights into future directions for sustainable water management. The study identifies key challenges such as institutional fragmentation, insufficient reuse infrastructure, and fragmented policy frameworks, while also highlighting opportunities related to digital monitoring, stakeholder collaboration, and investment in green infrastructure. These findings underscore the need for coordinated strategies to advance the One Water approach in Greece.

1. Introduction

Water has shaped human societies and development since antiquity, including in ancient Greece, where communities managed and utilized water resources long before recorded history [1]. Today, access to clean and sufficient water is internationally recognized as a fundamental human right and a prerequisite for public health and sustainable development. At the same time, pressures on global water systems have intensified: nearly two billion people face severe water scarcity, freshwater species populations have declined by 83% since 1970, and one-third of wetlands—critical components of Earth’s hydrological and ecological balance—have disappeared [2,3]. These trends highlight an urgent need for governance approaches that protect freshwater ecosystems and strengthen resilience to mounting water demand. Organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) are actively involved in restoring rivers and wetlands, promoting protected areas, and supporting efforts to maintain free-flowing rivers and enhance ecological resilience [4].

Against this global backdrop, Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) has served as a key framework for coordinating water use across sectors, emphasizing efficiency, equity, and ecosystem protection. However, the extension of these principles to broader land and environmental management remains recent and still evolving [2]. Building on IWRM, the OWC advances a holistic view of all water—surface water, groundwater, wastewater, stormwater, and reclaimed water—as parts of a single, interconnected system. The OWC promotes cooperative governance across institutions and communities to provide secure, affordable, and sustainable water and sanitation services, while also generating social, economic, and ecological co-benefits.

At its core, the OWC is grounded in values of equity, accessibility, and affordability, recognizing that all water sources constitute a unified resource that must be managed collectively [2,5]. Implementing this approach requires a shift from reductionist to systems thinking, acknowledging the complex interdependencies within the water cycle and calling for interdisciplinary and cross-sector collaboration [2,6]. Recent scholarship on sustainability transitions further highlights that integrated water management is not only a technical challenge but also an institutional and epistemological one, demanding transformations in governance structures and decision-making practices [2,4,5].

In practical terms, the OWC has increasingly influenced the water sector by emphasizing strategic planning, long-term reliability, and resilience of water supplies. For example, efforts to expand water reuse exemplify the need to consider contaminants such as fecal matter, nutrients, pharmaceuticals, oils, and fats—factors that determine required treatment levels and safe applications of reclaimed water [7]. Such examples illustrate how operationalizing the OWC requires coordinated management of the entire water cycle.

The main aim of this paper is to critically examine how the OWC can be implemented in Greece through interdisciplinary and policy-oriented perspectives. Specifically, the paper seeks to: (a) identify methodological and institutional challenges; (b) synthesize insights from international case studies; and (c) propose pathways for advancing integrated water governance and reuse practices under the OWC framework. These aims correspond to three guiding research questions: (a) How can the OWC be contextualized within Greece’s fragmented water governance structure? (b) What interdisciplinary and policy pathways can enable its implementation? (c) Which lessons from international OWC cases are transferable to the Greek context? Addressing these questions provides practical insights for policymakers and utilities seeking to operationalize integrated and circular water management in Mediterranean settings (Figure 1). The paper also offers a historical and conceptual overview of the One Water approach, drawing on diverse international examples. A broad literature survey was conducted, complemented by publicly available materials such as commentaries, reports, visual data, and case-based evidence.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study framework highlighting the three guiding research questions addressed in this work.

The study is organized into seven main sections. Section 1 introduces the topic and outlines the structure of the paper. Section 2 discusses the significance of water on Earth and Greece’s hydrological profile, while Section 3 and Section 4 trace the evolution of water history and policy. Section 5 examines patterns of water use and management. Section 6 and Section 7 present international and Greek case studies, and Section 8 and Section 9 outline challenges and barriers to One Water implementation in Greece and conclude with key insights and perspectives for the future.

2. Water World and Greece Hydrological Profile

Our planet is often described as a “water world,” and for good reason. Approximately 71% of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, with the vast majority, around 96.569%, residing in the oceans. Water is also present in many other forms and locations: about 1.741% exists as water vapor in the atmosphere, in rivers and lakes, within glaciers and icecaps, underground as soil moisture or stored in aquifers, and even within living organisms, including humans and animals.

Groundwater accounts for roughly 1.69% of Earth’s water, while lakes hold about 0.013%, and a smaller fraction, approximately 0.0011%, is found in swamps, rivers, and biological sources. Altogether, Earth’s total water volume is estimated at 1.386 billion km3. Of this total, 97.5% is saline, and only 2.5% is classified as freshwater. However, just 0.3% of that freshwater is accessible in liquid form on the surface, such as in rivers and lakes [6].

The most recent data available (mid-2025) provide estimates of global river runoff, indicating its distribution across continents and regions, along with annual discharge volumes and their proportional contribution to total global flow, as summarized in Table 1. This information was based on model estimates and observational synthesis of hydrological data provided by AQUASTAT (FAO’s Global Water Information System) and UNESCO.

Table 1.

Distribution of river runoff across the Earth’s surface.

Despite water’s fundamental importance to life and its abundance on Earth, millions of people still face severe inequities in access and quality. According to recent global assessments, about 2.1 billion individuals lack safely managed drinking water, including more than one hundred million who rely directly on untreated surface sources. Moreover, approximately 3.4 billion people remain without adequate sanitation, with hundreds of millions still practicing open defecation. Finally, 1.7 billion individuals do not have basic hygiene facilities at home and over six hundred million have no access at all [8,9]. Growing awareness of these disparities has accelerated the adoption of non-conventional water sources, particularly through the expansion of desalination technologies and water reuse initiatives [9]. This uneven global and regional distribution reinforces the necessity of integrated and adaptive management frameworks such as the OWC, which recognizes water as a shared and finite resource that must be governed holistically across spatial and institutional boundaries.

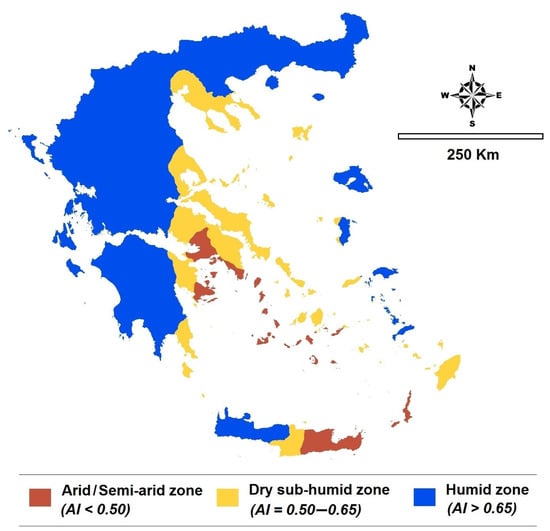

In the case of Greece, the country’s hydrological profile reflects strong regional contrasts, with high precipitation and runoff in western areas and pronounced aridity in east southern and island regions. These spatial disparities underline the necessity of adopting integrated management approaches such as the One Water framework, which follows the natural movement of water across the hydrological cycle—from mountain to sea—and supports decisions that enhance both environmental health and human water security. Greece is located in South Eastern Europe, bordering the Ionian Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. Within the Greek context, the total national area including the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) covers roughly 505,572 km2, with a land surface of about 131,957 km2 and an extensive coastline exceeding 13,676 km across the mainland, with an archipelago of about 3000 islands. The average annual precipitation, around 874 mm/yr, remains unevenly distributed: approximately 65% of the rainfall occurs in the northwestern regions, while only 35% is recorded in southeastern Greece, particularly in the southern Aegean Islands and eastern Crete [10]. The spatial variability of the Aridity Index (AI) in Greece (Figure 2) represents a clear climatic gradient, with semi-arid conditions dominating the south eastern regions, dry sub-humid zones concentrated in central areas, and humid conditions prevailing in the western and mountainous parts of the country. This pattern highlights regional differences in water availability, which is crucial for the OWC approach, emphasizing integrated management of water resources across diverse hydro-climatic regimes.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of the Aridity Index (AI) in Greece based on the UNEP (1997) classification, simplified into three classes: Arid to semi-arid (AI < 0.5), Dry sub-humid (AI = 0.50–0.65), and Humid (AI > 0.65) (after Kourgialas [10]).

3. The History of Water Policy in Greece: From Ancient Philosophy to Modern Practice

Water has always shaped the identity, prosperity, and politics of Greece. In the arid Mediterranean climate, water was never simply a natural resource—it was a foundation of civilization and an object of shared responsibility. Ancient Greek city-states developed remarkably advanced water management systems, from the aqueducts of Athens to the fountains of Corinth, built not just for utility but as civic symbols of balance between human ingenuity and nature’s gifts [11].

As Greek thought matured, philosophers began to link water to the essence of life and order. Thales of Miletus (ca 640/35–543 BC), a pre-Socratic philosopher, declared in the Ionian School of Philosophy at 600 BC that “all is water,” suggesting a unity between the natural and moral worlds. Aristotle (384–322 BC) advanced this line of thinking by treating water as one of the four fundamental elements essential to both natural and political harmony. For Aristotle, the management of water symbolized the prudent governance of all shared goods: moderation, balance, and rational oversight were the marks of a virtuous state. His emphasis on moderation (mesotes) would echo through centuries of Greek environmental philosophy [12].

In classical Athens, water distribution reflected the values of the polis itself. Public fountains were common property, accessible to all, and their maintenance was considered a duty of civic virtue. The Greeks understood that collective welfare depended on the stewardship of shared resources—an early expression of what we might now call “integrated water management.” City laws even regulated access and quality, with fines for waste or pollution, showing that governance and environmental ethics were deeply intertwined [12].

Fast forward to modern Greece, and these ancient principles still find resonance. Today, water policy is framed within the European Union’s Water Framework Directive, emphasizing sustainable use, ecosystem protection, and the integration of local communities into decision-making. Greece’s National Water Management Plans, established in the 21st century, seek to balance agricultural demand, tourism pressures, and climate adaptation—an echo of Aristotle’s ideal of balance and rational governance. From the marble fountains of ancient Athens to modern desalination projects on the Aegean islands, Greece’s water story reflects a continuous dialogue between nature, society, and philosophy. The challenges have evolved, but the underlying ethos remains familiar: water is not merely a resource to be consumed, but a shared trust to be understood, managed, and respected—a timeless reflection of the “one water” idea [10,13].

4. Integrated Water Policy and Governance

In developed regions such as the European Union, regulatory frameworks for water reuse are typically well-established, aiming to be comprehensive, adaptable, and effective. These frameworks are grounded in realistic risk assessments. However, existing national regulations for recycled water often require updates to reflect current scientific knowledge—particularly regarding the risks posed by pathogens and trace organic compounds. Revising these regulations with a practical, risk-based approach can help promote water reuse, minimizing unnecessary restrictions and regulatory barriers.

To be effective, regulations and guidelines should remain clear, adaptable, and user-friendly, ensuring they support intended performance goals. A more functional approach may involve setting quality standards based on the intended use of the water, regardless of its origin (such as freshwater or treated wastewater), rather than creating separate rules for each type of water source [11].

It is also essential to recognize the distinction between developed and developing countries in this context. For regions with limited infrastructure or regulatory capacity, a gradual, step-by-step strategy is more practical. Improving existing risk conditions is often preferable to introducing overly strict legislation that may be difficult to enforce. Ultimately, as understanding of the biological and chemical risks associated with water reuse grows, regulatory updates will be necessary to reflect this progress [14]. To navigate future water management and reuse challenges effectively, cities must adopt the One Water approach as a guiding principle.

In the Greek context, the idea of water as a shared public resource has deep historical roots. During the Classical and Hellenistic periods (ca 480–31 BC), engineering, philosophy, and governance were closely aligned under a unified vision of integrated water management. Reviving this holistic perspective could help strengthen coherence across modern water policies.

Today, however, Greek water governance often remains fragmented, with policies differing by water type and use—such as supply, irrigation, industrial, or wastewater—across central, regional, and local levels [10]. On a global scale, establishing more integrated and unified water governance structures is essential. Consolidating agencies responsible for all water types, regardless of source or application, would advance the goals of the OWC and promote policy coherence [7,14].

In Greece, the implementation of the EU Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) through national River Basin Management Plans partially reflects the OWC principles of integration and sustainability. However, water governance remains fragmented across ministries and administrative levels, underscoring the need for unified institutional structures and coordinated policy actions [10,15].

5. Water Use and Integrated Water Resource Management

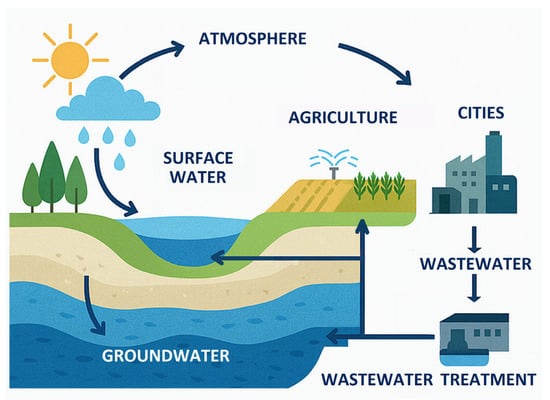

In today’s world, rapid urbanization, population growth, and higher living standards continue to intensify water demand. This growing pressure stems from rising populations, expanding irrigation areas, increasing industrial zones, and the movement of people in tourism and migration. To sustain life on a finite planet, humanity must recognize that there is only one interconnected water system on one Earth. Physical boundaries cannot be expanded, but collective awareness and cooperation can. Achieving water sustainability requires global solidarity and a systems-based understanding of the atmosphere, surface water, and groundwater as a unified cycle. Villholth [16] illustrates this holistic view in the One Water framework, emphasizing the continuous recycling of water through Earth’s atmosphere and subsurface layers. The One Water framework, which conceptualizes the hydrological cycle as a single, integrated system linking the atmosphere, surface water, groundwater, and human activities are illustrated in Figure 3. This holistic view underscores the importance of cooperation and systems thinking in achieving water sustainability.

Figure 3.

Conceptual representation of the One Water framework, highlighting the interconnected pathways between atmospheric, surface, and subsurface water systems and their interactions with human activities.

Information on water use by source involves surface water, groundwater and direct or indirect use of unconventional sources of water, i.e., treated municipal wastewater. Other unconventional sources are harvested and stored rainwater, desalinated water, and agricultural drainage water used mainly for irrigation purposes [17]. Water is used to grow our food, manufacture our favorite goods, and keep our businesses running smoothly. We also use a significant amount of water to meet the nation’s energy needs. WaterSense is an important example of a program to help reduce commercial and institutional water use [18]. The principal uses of water are: potable, agricultural, industrial, transportation, chemical, medical use, recreation, food processing, fire considerations, and heat exchange. Consequently, the water resources sector is encouraged to adopt the One Water philosophy, which calls for the integrated management of all water types and flows—beginning with rainfall as the origin of the hydrological cycle, and extending through stormwater, industrial effluents, domestic wastewater, and drinking water—ensuring that every drop of rain is valued throughout its entire path. This transformation depends on collaboration among professionals across the water sector to address emerging challenges through shared knowledge and coordinated action [17,18].

In Greece, approximately 85% of total water withdrawals are devoted to irrigation, followed by 12% for domestic use and 3% for industry [19]. This high dependence on irrigation, combined with limited rainwater harvesting and low levels of natural recharge, highlights the importance of integrated demand–supply management strategies and the relevance of the One Water approach, which begins with rainfall as the primary resource and promotes sustainable allocation across agricultural, urban, and industrial sectors.

While Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) has long served as a foundation for integrated water management, the OWC extends this framework by emphasizing circular economy principles, urban–rural linkages, and the co-management of natural and engineered systems. OWC thus moves beyond coordination among sectors toward a holistic governance model where all water is valued as a single, interconnected resource [20]. Angelakis et al. [21] stated that water management should be integrated with all sources of water (e.g., drinking water and wastewater). In the environmental engineering and water resources field must be used of the term “one water” to describe all forms of water. The implications of the OWC for municipalities would be to merge what are now typically individual water and wastewater departments into one department. By merging the two departments it is reasoned that more thoughtful, rational and cost-effective solutions can be developed to meet future water needs.

The IWRM approach promotes a comprehensive and cooperative framework for planning and delivering water-related services. The primary objective of this approach is to harmonize economic growth, social well-being, and environmental protection, by combining social, economic, and ecological dimensions into a unified management strategy [22]. Achieving this balance requires active participation of stakeholders, innovative financial mechanisms, and the application of nature-based infrastructure to strengthen water security, resilience to climate variability, and public health [2]. According to UNEP [3], sustainable water management should acknowledge the intrinsic connectivity among supply, wastewater, and stormwater systems rather than treating them as isolated domains.

6. Global Case Studies of One Water Implementation

Managing water resources in the 21st century presents increasingly complex challenges, shaped by urban growth, agricultural intensification, and climate variability [23]. Within the European Union (EU), integrated management of water resources forms a cornerstone of environmental policy, as reflected in the Water Framework Directive (WFD, 2000). The directive establishes a coordinated approach to managing water, land, and related ecosystems with the goal of achieving good ecological and chemical status for all water bodies while promoting sustainable use [24]. Although water reuse remains limited in many central and northern European countries, Mediterranean regions have made notable progress in recent years. Among EU members, Cyprus leads in wastewater reuse, achieving rates above 80% of treated effluent [25].

The global evidence shows a growing need for coordinated management to guarantee adequate and reliable water resources for all, while fostering innovation, job creation, and cost efficiency through circular use of water. Some notable case studies of applying OWC on a global scale, which can serve as examples for Greece are as follows:

- (a)

- Case study: Singapore—NEWater and IWRM.

Singapore is a global leader in implementing IWRM through its comprehensive “Four National Taps” strategy, which combines local catchment water, imported water, desalinated water, and reclaimed water known as NEWater. This approach reflects a holistic vision of national water security under conditions of limited natural resources and high urban density.

NEWater—produced through microfiltration, reverse osmosis, and ultraviolet disinfection—meets potable standards and is used for both industrial and indirect potable reuse. By closing the urban water loop, Singapore has transformed wastewater into a strategic resource, strengthening resilience against drought, pollution, and climate variability.

The integration of technological innovation, governance, and public acceptance makes Singapore’s model one of the most advanced examples of the OWC in practice—where every drop of water is valued, recycled, and reintegrated into the national supply system [26,27].

- (b)

- Case study: Los Angeles, USA—The One Water LA 2040 Plan.

The One Water LA 2040 Plan represents Los Angeles’ integrated vision for managing water supply, wastewater, and storm water within a single, coordinated framework. Developed collaboratively among multiple city departments and agencies, the plan seeks to maximize local water reuse, reduce reliance on imported supplies, and build climate resilience in one of the most water-stressed regions of the United States.

Los Angeles operates one of the world’s largest wastewater recycling networks, producing high-quality reclaimed water for non-potable and indirect potable uses. Water from several reclamation plants is distributed across hundreds of sites to support landscape irrigation, industrial operations, and groundwater replenishment. In parallel, the city promotes green infrastructure, storm water capture, and ecosystem restoration to enhance urban livability and watershed health.

The One Water LA 2040 Plan embodies the core principles of the OWC—treating all forms of water as interconnected resources, fostering interdepartmental collaboration, and integrating human, environmental, and infrastructural needs into a sustainable and resilient urban water future [28,29].

- (c)

- Case study: Orange County, USA—Groundwater Replenishment System (GWRS).

The GWRS in Orange County, California, is the world’s largest advanced water purification project for indirect potable reuse and a flagship example of the OWC. Developed jointly by the Orange County Water District and the Orange County Sanitation District, the system treats wastewater through microfiltration, reverse osmosis, and ultraviolet disinfection with hydrogen peroxide, producing ultra-pure water. This water is then injected into coastal barrier wells to prevent seawater intrusion and recharged into the local groundwater basin, which supplies drinking water to over 2.5 million people. Producing more than 130 million gallons (≈490,000 m3/day), the GWRS effectively expands local water resources while reducing dependence on imported water. The project illustrates how integrated planning, advanced technology, and public engagement can transform wastewater into a safe and sustainable source of potable water. It stands as a global model of circular and resilient water management, aligning with the One Water vision of treating all water as a single, interconnected resource [30,31].

- (d)

- Case study: Melbourne, Australia—Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD).

The city of Melbourne has been a global pioneer in implementing (WSUD), an approach that integrates water management directly into urban planning and landscape design. Through features such as bioretention systems, permeable pavements, rain gardens, and constructed wetlands, Melbourne captures and treats storm water locally, reducing runoff and enhancing groundwater recharge.

WSUD not only improves storm water quality and flood resilience, but also provides broader urban co-benefits—including urban heat mitigation, increased green space, and enhanced community livability. The strategy reflects the One Water philosophy, treating all forms of water—rainwater, stormwater, wastewater, and groundwater—as interconnected resources within a single urban cycle.

Melbourne’s success has influenced city planning across Australia and internationally, showcasing how nature-based and decentralized systems can promote both sustainability and resilience in urban environments under changing climatic conditions [31,32,33].

- (e)

- Case study: Dakar, Senegal—Circular Economy in Wastewater Management.

In Dakar, the National Office of Sanitation (ONAS) has developed innovative programs for fecal sludge treatment and wastewater reuse, advancing a circular economy approach to urban sanitation. Through decentralized treatment facilities, ONAS recovers valuable resources such as biogas for energy production and treated water for agricultural use, reducing both environmental impacts and operational costs.

These initiatives demonstrate how resource recovery and reuse can transform sanitation challenges into opportunities for economic growth, energy generation, and food security. By linking water management with social and economic development, Dakar’s model represents an emerging example of One Water in action—integrating human health, environmental protection, and sustainable resource use within a single management framework [34,35].

- (f)

- Case study: Hammarby Sjöstad, Stockholm, Sweden—Eco-District and Water-Energy Nexus.

The Hammarby Sjöstad district in Stockholm is an internationally recognized example of integrated water, energy, and waste management within an urban eco-district framework. Designed as part of the city’s environmental program, the area applies a closed-loop “Hammarby Model”, where wastewater, stormwater, and solid waste are treated as interconnected resources.

Energy is recovered from wastewater and biogas production, while stormwater is locally treated through green infrastructure such as wetlands and vegetated swales. The integration of renewable energy systems, efficient water reuse, and sustainable urban design reduces emissions and resource consumption, making Hammarby Sjöstad a benchmark for climate-resilient, low-impact development.

This project embodies the OWC, illustrating how coordinated management of water and energy flows can support urban sustainability, circular resource use, and enhanced quality of life in dense metropolitan contexts [36,37].

These international examples collectively demonstrate that the success of the One Water approach depends on institutional integration, cross-sectorial collaboration, technological innovation, and strong governance frameworks. Such lessons provide valuable guidance for adapting and advancing the OWC within the Greek context. Specifically, the global examples of Orange County, Melbourne, Dakar, Stockholm, Singapore, and Los Angeles offer valuable insights for shaping a Greek pathway toward One Water management. Translating these experiences requires a context-sensitive approach that reflects Greece’s fragmented governance, hydrological variability, and seasonal water scarcity. Adapting elements such as wastewater reuse and aquifer recharge from Orange County and Singapore could strengthen water resilience in islands and coastal regions, while nature-based solutions inspired by Melbourne and Stockholm could enhance urban stormwater management and climate adaptation in Greek cities. Likewise, Dakar’s circular sanitation model and Los Angeles’ collaborative planning underscore the need for resource recovery, cross-agency coordination, and public participation.

By promoting pilot projects through Greek local utilities (DΕYA), regional authorities, and research institutions such as ELGO DIMITRA, Greece could gradually advance toward an integrated and circular water framework. Embracing these principles would enable a transition toward a resilient, low-impact, and socially inclusive One Water future tailored to the Greek landscape.

7. Greece Case Studies of One Water Implementation

This study adopts a qualitative case study design combining document analysis, international case review, and semi-structured interviews to examine the potential for implementing the OWC in Greece. The approach aims to explore institutional conditions, governance challenges, and opportunities for integrated water management in diverse contexts.

Case studies were selected based on three criteria: (a) their relevance to emerging OWC principles (e.g., reuse initiatives, basin governance, decentralized systems); (b) the availability of publicly accessible documentation and technical reports; and (c) their representativeness of key governance scales in Greece (river basin, municipal utility, metropolitan region, and decentralized reuse projects).

These criteria ensured that the selected cases reflect different hydrological conditions, levels of urbanization, and institutional arrangements.

Data collection combined policy documents, technical reports, academic literature, and eight (n = 8) semi-structured interviews with water managers, policymakers, and researchers. Participants were selected through purposive sampling based on their direct involvement in water governance, reuse initiatives, or strategic planning. The interviews followed an open-ended guide that allowed for follow-up questions and inductive exploration of governance challenges, institutional fragmentation, reuse potential, and cross-sectoral coordination.

All qualitative material (documents and interviews) was analyzed through thematic coding. The analytical process consisted of four steps: (1) initial coding to identify recurring topics; (2) grouping codes into broader themes related to OWC principles (e.g., circularity, collaboration, basin governance, infrastructure efficiency); (3) cross-case comparison to identify converging or diverging patterns across Greek and international cases; and (4) synthesis of insights to derive policy and implementation pathways. This multi-source qualitative strategy enhances analytical rigor by combining institutional analysis, stakeholder perspectives, and international evidence.

The Greek case studies that follow—Evrotas River Basin, Drama Water Utility, Athens Nursery Sewer Mining Project, the Attica Region wastewater network, Eastern Attica reuse schemes, and the Heraklion reuse initiative—are explicitly examined through the lens of OWC principles such as cross-sectoral collaboration, circular resource use, and participatory governance.

7.1. Evrotas River Basin: Integrated River Basin Management and Participatory Governance

The Evrotas River Basin, located in the Peloponnese region, exemplifies the challenges and opportunities associated with implementing the OWC in a predominantly agricultural setting. The basin has experienced significant water quantity and quality issues, primarily due to over-extraction for irrigation and agricultural pollution. In response, the LIFE-EnviFriendly Project undertook restoration efforts, including the reinforcement of 120 m of riverbank near Sparta using stone hedges and the planting of 200 poplar trees to restore the riparian forest [38]. These nature-based solutions aimed to mitigate erosion and improve water quality.

Furthermore, the implementation of the Water Framework Directive (WFD) in the Evrotas Basin emphasized the importance of public participation in water governance. However, the centralized structure of the Greek state posed challenges to effective stakeholder engagement. Efforts to involve local communities in the development of the River Basin Management Plan highlighted the need for context-specific participatory processes to enhance water governance [39]. This case study illustrates the OWC principle of integrating ecological restoration with participatory basin governance, demonstrating how community involvement can enhance both environmental and institutional resilience.

7.2. Drama Water Utility: Urban Water Loss Management and Infrastructure Optimization

The city of Drama in northern Greece provides a compelling case study on urban water management within the OWC framework. The local water utility faced challenges related to non-revenue water losses, prompting the implementation of a comprehensive assessment of the water distribution network. By employing methods such as Minimum Night Flow analysis and the Bursts and Background Estimates (BABE) approach, the utility identified significant leakages and inefficiencies. Subsequent interventions included pressure management, network rehabilitation, and the installation of advanced metering infrastructure, leading to a substantial reduction in water losses and improved resource efficiency [40]. The Drama initiative embodies the OWC approach to optimizing urban water systems through cross-sectoral management, infrastructure modernization, and demand-side efficiency, resulting in measurable resource savings.

7.3. Athens Nursery: Decentralized Water Reuse Through Sewer Mining

A pilot initiative in Athens demonstrates how the OWC can be applied on a smaller, urban scale. The project employs decentralized treatment technologies based on sewer mining to recover water and nutrients from municipal wastewater for reuse in irrigation and compost production. Using a compact, container-based treatment system equipped with a membrane bioreactor (MBR) and ultraviolet disinfection, the facility provides recycled water directly on-site. Beyond its technical success, the project highlights the principles of the circular economy, reducing demand for freshwater while integrating water, energy, and material cycles within an urban environment [41]. The Athens Nursery project exemplifies decentralized reuse and circular water flows, aligning with OWC objectives of resource recovery, local resilience, and reduced dependency on centralized infrastructure.

7.4. Centralized Wastewater Management in the Attica Region

The Attica region—covering approximately 3808 km2—is the most densely populated and urbanized part of Greece, home to nearly 3.9 million residents, accounting for almost 40% of the country’s total population. The Greater Athens area is served by several biological nutrient removal (BNR) wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). The largest facility operates on Psyttalia Island, designed for about 3.5 million population equivalents (p.e.), followed by the Metamorphosi WWTP in the northwest, with a capacity of 500,000 p.e., and the Thriasio WWTP to the west, designed for 117,000 p.e. In addition, three new treatment plants are either under construction or in advanced planning along the eastern Attica coast [17]. The Psyttalia WWTP, commissioned in 1995, remains the country’s largest wastewater facility, with a hydraulic capacity of about 300 million m3 per year. Its system incorporates advanced secondary treatment for nutrient removal, as well as sludge stabilization and energy recovery through biogas utilization [25]. This large-scale system exemplifies the integration of treatment efficiency, energy recovery, and environmental protection within Greece’s most urbanized region.

7.5. Regional Reuse Projects in Eastern Attica

Several large-scale projects are simultaneously being implemented in Rafina–Artemida, Marathonas, and Koropi–Paiania. These systems are designed to produce high-quality reclaimed water intended for agricultural irrigation during the dry season and for groundwater recharge during the wetter months, thereby helping to restore local aquifers. When completed, this collective effort will represent the second-largest water reuse initiative in Greece, following the Thessaloniki project in the northern region [17]. The Eastern Attica projects demonstrate how coordinated, multi-site planning can achieve regional-scale water reuse with direct benefits for agriculture and aquifer sustainability.

7.6. Large-Scale Reuse Initiative in Heraklion, Crete

In Heraklion, the capital of Crete, one of Greece’s largest water reuse initiatives is currently under development. The facility is designed to treat approximately 36,000 m3 of wastewater per day to high-quality standards, with a total budget of 18.6 million €, and is scheduled for completion in the near future. Once operational, the project will irrigate about 2883 ha of farmland located south and southwest of Heraklion during the dry season. An additional 1000 m3/d will support the irrigation of urban and peri-urban green spaces covering roughly 18 ha. During winter months, the reclaimed water will be used for aquifer recharge, helping to restore degraded groundwater reserves. Despite such promising developments, less than 10% of treated urban wastewater is currently reused in Greece, underscoring the need for broader implementation of similar projects [17,42].

Overall, these case studies reveal a gradual but uneven alignment of Greek water practices with EU policy objectives. While progress has been achieved in reuse and efficiency measures, fragmentation across administrative jurisdictions remains a barrier to full implementation of the OWC principles, echoing broader challenges observed across Mediterranean EU Member States.

8. Challenges and Barriers of One Water Implementation in Greece

The implementation of the OWC in Greece brings both opportunities and challenges. Progress has been observed in the areas of circular water use, digital monitoring, and stakeholder engagement, yet further action is required to remove institutional constraints and strengthen cross-sectorial collaboration. Future research should focus on adaptive frameworks that integrate technical, social, and policy dimensions to advance the OWC agenda [43,44].

In the Attica Region (area 3808 km2) according to the 2021 census, 3,814,064 inhabitants or 36.39% of the total population of the country live with a density of 1001.60 inhabitants/km2. In Athens, the largest city in Greece, drinking water is transported from the NW country from a distance of 220 km [17]. In southeastern Greece, potable water reuse is a key component in advancing sustainable strategies for enhancing water supply, particularly in densely populated urban regions.

In the case of Athens, the cycle in which water is withdrawn from inland areas, transported to city, treated, consumed with the resulting wastewater transported to the island of Psyttalia for treatment and dispersal to coastal sea waters is unsustainable [17]. The disposed treated wastewater is about one third of the total produced treated wastewater in the country, which is estimated 1000 million m3/yr. These case studies illustrate the multifaceted approaches to implementing the OWC in Greece, encompassing rural watershed management, urban infrastructure optimization, and innovative water reuse technologies [3,4,7]. Each example underscores the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, stakeholder engagement, and context-specific strategies in advancing IWRM.

Across the examined cases, several cross-cutting patterns emerge that highlight both the opportunities and limitations of One Water implementation in Greece. The Greek examples generally align with key OWC principles—such as cross-sectoral collaboration, circular resource use, and integrated basin management—but progress remains uneven across governance levels and geographical contexts. Compared to international leaders such as Singapore, Orange County, or Melbourne, Greek initiatives demonstrate strong potential in areas like wastewater reuse (Heraklion, Eastern Attica) and participatory basin governance (Evrotas), yet they face persistent challenges related to institutional fragmentation, limited coordination among agencies, and inconsistent long-term planning. By contrast, countries with advanced One Water frameworks exhibit more mature governance structures, clearer division of responsibilities, and stable investment pathways that enable technological innovation and systemic integration. Overall, the comparative evidence suggests that Greece is moving toward One Water principles, but broader institutional reforms, improved operational capacities, and strengthened inter-agency cooperation will be essential to support a fully integrated and resilient water management transition.

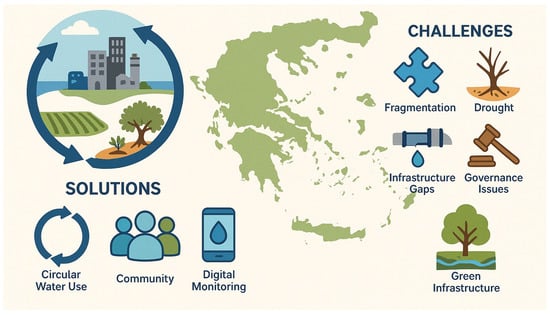

The analysis reveals that while notable advances have been achieved, particularly in wastewater reuse and digital monitoring, the adoption of OWC principles in Greece remains constrained by institutional fragmentation, inconsistent policy enforcement, and limited cross-sectorial coordination. The dynamic relationship between key barriers—such as institutional fragmentation, funding gaps including infrastructure gaps and lack of investments in green infrastructure, climate-water effects, and limited financial resources or stakeholder engagement—and the corresponding solutions proposed within the One Water framework, including governance integration, innovation funding, and enhanced participatory planning is depicted in Figure 4. Addressing these issues requires coordinated efforts and policy reforms. The transition to OWC necessitates methodological innovations that embrace complexity and uncertainty. Epistemologically, it calls for integrating diverse knowledge systems and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration [45,46].

Figure 4.

A graphical representation of the OWC implementation in Greece including challenges and solutions.

9. Conclusions and Future Prospects

The six Greek case studies demonstrate that the OWC can be applied across diverse contexts—from river basin management to urban distribution systems and decentralized reuse—revealing both significant opportunities and persistent institutional constraints. The Evrotas Basin highlights the value of participatory governance for basin-scale integration, while the Drama Water Utility illustrates how infrastructure optimization can enhance efficiency and reduce losses. Decentralized reuse in Athens and large-scale agricultural and regional schemes in Attica and Heraklion show growing interest in circular practices that link treatment, reuse, and aquifer recovery. Together, these cases indicate a gradual transition from conventional wastewater management toward more integrated and circular approaches aligned with OWC principles.

The findings underscore the need for stronger cross-sectoral cooperation, improved coordination between governance levels, and stable long-term planning. At the municipal scale, collaboration among hydrologists, engineers, ecologists, farmers, and local utilities is essential for designing context-specific solutions. At the regional and national levels, clearer institutional responsibilities and consistent policy frameworks are crucial for enabling reuse, reducing fragmentation, and supporting integrated planning.

Based on the analysis, several policy directions can support OWC implementation in Greece [47,48,49,50]: (a) adopting water-cycle planning approaches across national, regional, and local scales;(b) improving coordination and communication within the water sector when engaging regulatory authorities; (c) strengthening collaboration with agriculture to address source water quality and manage runoff; (d) establishing stable financial mechanisms that support infrastructure, monitoring, and reuse; (e) promoting standardized water quality guidelines developed in cooperation with industry stakeholders; and (f) advancing public awareness of the value of water, ensuring affordability while supporting necessary investments.

Greece has made strides in adopting OWC principles, yet unified policies and institutional frameworks at central, regional, and local levels are still needed. Strengthening these frameworks in both management and education can foster a holistic, resilient, and integrated water governance system, in line with SDG 6 and global efforts to secure universal access to safely managed water and sanitation.

Overall, the study contributes to ongoing debates on integrated water governance by situating the OWC as both a practical and epistemological framework. It demonstrates that Greece possesses promising examples of integration, but institutional reform, capacity building, and cross-agency coordination remain essential to fully realize a One Water transition. By promoting unified governance structures and interdisciplinary research and education, Greece can advance toward a coherent, circular, and sustainable water system capable of addressing future challenges in a Mediterranean context increasingly shaped by climate pressures and competing demands.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N.K. and A.N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.N.K., A.N.A. and G.T.; writing—review and editing, N.N.K., A.N.A. and G.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data and additional information are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tvedt, T.; Oestigaard, T. A History of the Ideas of Water: Deconstructing Nature and Constructing Society. In History of Water; I.B. Tauris: London, UK, 2010; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognesi, T.; Gerlak, A.K.; Giuliani, G. Explaining and Measuring Social-Ecological Pathways: The Case of Global Changes and Water Security. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP (Unite Nation Environment Program). Progress on Implementation of Integrated Water Resources Management; UN-Water: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.unep.org/topics/fresh-water/water-resources-management/integrated-water-resources-management (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Koundouri, P.; Papandreou, N.A. Water Resources Management Sustaining Socio-Economic Welfare: The Implementation of the European Water Framework Directive in Asopos River Basin, Greece; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, A. One Water and Regenerative Land Practices: The Power of Partnership Through Yahara WINS; US Water Alliance: Federal Way, WA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://uswateralliance.org/one-water-and-regenerative-land-practices-the-power-of-partnership-through-yahara-wins/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Shiklomanov, L.A. World Freshwater Resources. In Water in Crisis: A Guide to World’s Freshwater Resources; Gleick, P.H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kourgialas, N.N. How Does Agricultural Water Resources Management Adapt to Climate Change? A Summary Approach. Water 2023, 15, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siliman, A. ‘Unacceptable’: A Staggering 4.4 Billion People Lack Safe Drinking Water, Study Finds. Nature 2024, 632, 964–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 1 in 4 People Globally Still Lack Access to Safe Drinking Water; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/philippines/news/detail-global/26-08-2025-1-in-4-people-globally-still-lack-access-to-safe-drinking-water---who--unicef (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Kourgialas, N. A critical review of water resources in Greece: The key role of agricultural adaptation to climate-water effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 145857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranychianakis, N.V.; Salgot, M.; Snyder, S.A.; Angelakis, A.N. Quality Criteria for Recycled Wastewater Effluent in EU-Countries: Need for a Uniform Approach. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 1409–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoyiannis, D.; Angelakis, A.N. Hydrologic and Hydraulic Sciences and Technologies in Ancient Greek Times. In Encyclopedia of Water Science; Stewart, B.A., Howell, T., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 415–417. [Google Scholar]

- Kourgialas, N.N. Hydroclimatic Impact on Mediterranean Tree Crops Area—Mapping Hydrological Extremes (Drought/Flood) Prone Parcels. J. Hydrol. 2021, 596, 125684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourgialas, N.N. Reconsidering the Soil–Water–Crops–Energy (SWCE) Nexus Under Climate Complexity—A Critical Review. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WED. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy. In Official Journal of the European Communities; WED: Brussels, Belgium, 2000; Volume L 327, pp. 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Villholth, K.G. One Water: Expanding Boundaries for a New Deal and a Safe Planet for All. One Earth 2021, 4, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Tzanakakis, V.A.; Capodaglio, A.G.; Dercas, N. A Critical Review of Water Reuse: Lessons Learnt from Prehistoric Greece for Present and Future Challenges. Water 2023, 15, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). WaterSense Program: About the Program. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/climate-change-water-sector/watersense-program (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT). Statistical Data and Reports. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/statistics (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Beckett, R.C.; Terziovski, M. Integrating Circular Economy Principles in Water Resilience: Implications for CorporateGovernance and Sustainability Reporting. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Asano, T.; Bahri, A.; Jimenez, B.E.; Tchobanoglous, G. Water Reuse: From Ancient to Modern Times and Future. Front. Environ. Sci. 2018, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, N.S. Stormwater Management: An Integrated Approach to Support Healthy, Livable, and Ecological Cities. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M.; Shah, T. From IWRM back to integrated water resources management. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2014, 30, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rijswick, M.; Keessen, A. The EU Approach for Integrated Water Resource Management. In Routledge Handbook of Water Law and Policy; Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Zafeirakou, A.; Kourgialas, N.; Voudouris, K. Evolution of Unconventional Water Resources in the Hellenic World. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PUB Singapore. NEWater—Recycled Water. Available online: https://www.pub.gov.sg/Public/WaterLoop/OurWaterStory/NEWater (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Bai, Y.; Shan, F.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y.; Luo, X.; Wu, Y.; Hu, H.-Y.; Zhang, B. Long-Term Performance and Economic Evaluation of Full-Scale MF and RO Process—A Case Study of the Changi NEWater Project Phase 2 in Singapore. Water Cycle 2020, 1, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Los Angeles Bureau of Sanitation. One Water LA 2040 Plan; City of Los Angeles Bureau of Sanitation: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://carollo.com/solutions/one-water-la-2040-plan/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Poosti, A.; Marrero, L.; Falcon, P.; Wiersema, I.; Reed, J. One Water LA: A Collaborative Approach to Integrated Water Management. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 2019, 111, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orange County Water District. Groundwater Replenishment System. 2022. Available online: https://www.ocwd.com/gwrs/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Clark, J.F.; Hudson, G.B.; Davisson, M.L.; Woodside, G.; Herndon, R. Geochemical imaging of flow near an artificial recharge facility, Orange County, CA. Ground Water 2004, 42, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T.D.; Shuster, W.; Hunt, W.F.; Ashley, R.; Butler, D.; Arthur, S. SUDS, LID, BMPs and More: The Evolution and Application of Terminology Surrounding Urban Drainage. Urban Water J. 2014, 12, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melbourne Water. Water Sensitive Urban Design. Available online: https://www.melbournewater.com.au/water-and-environment (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- World Bank. Water in Circular Economy and Resilience: The Case of Dakar; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/be099caa-001a-5ee4-8493-dff1ba54252b/content (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Diaw, M.T.; Cissé-Faye, S.; Gaye, C.B.; Niang, S.; Pouye, A.; Campos, L.C.; Taylor, R.G. On-Site Sanitation Density and Groundwater Quality: Evidence from Remote Sensing and In Situ Observations in the Thiaroye Aquifer, Senegal. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2020, 10, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarby Sjöstad, Stockholm, Sweden. Available online: https://urbangreenbluegrids.com/projects/hammarby-sjostad-stockholm-sweden/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Beatley, T. Green Cities of Europe: Global Lessons on Green Urbanism; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- LIFE05ENV/GR/000245 EnviFriendly. Environmental Friendly Technologies for Rural Development—Integrated Management Plan of the Evrotas River Basin & Coastal Zone. Prefecture of Laconia, Greece. Available online: https://www.up2europe.eu/european/projects/environmental-friendly-technologies-for-rural-development_128942.html (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Kampa, E.; Bressers, H. Evolution of the Water Framework Directive Implementation in Greece: Introducing Participation in Water Governance—The Case of the Evrotas River Basin Management Plan. Environ. Policy Gov. 2008, 18, 284–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kanakoudis, V.; Tsitsifli, S. Estimating Water Losses and Assessing Network Management Intervention Scenarios: The Case Study of the Water Utility of the City of Drama in Greece. Procedia Eng. 2016, 162, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevri, A.; Monokrousou, K.; Makropoulos, C.; Lioumis, C.; Tazes, N.; Lytras, E.; Samios, S.; Katsouras, G.; Tsalas, N. Sewer Mining as a Distributed Intervention for Water-Energy-Materials in the Circular Economy Suitable for Dense Urban Environments: A Real World Demonstration in the City of Athens. Water 2021, 13, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalis, E.S.; Municipal Water Supply & Sewerage Company of Heraklion (DEYAI). Addition of Tertiary Treatment at the Heraklion Wastewater Treatment Plant and Reuse of the Effluent for Irrigation. Region of Crete. 2024. Available online: https://thalis-es.gr/en/projects/water-cycle/1654774225-expansion-of-heraklion-waste-water-plant-for-the-treatment-of-the-wastewater-of-gazi-settlement-/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Kourgialas, N.N. A Holistic Irrigation Advisory Policy Scheme by the Hellenic Agricultural Organization: An Example of a Successful Implementation in Crete, Greece. Water 2024, 16, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Implementing Water Economics in the EU Water Framework Directive; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Water. Progress on Implementation of Integrated Water Resources Management; UN-Water: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.unwater.org/publications/progress-implementation-integrated-water-resources-management-2024-update (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Moleaer. Why One Water is Key for Successful Climate Action. Moleaer Blog. 2023. Available online: https://www.moleaer.com/blog/nanobubbles/one-water (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Dyson, J. ‘One Water’: Concept for the Future? WaterWorld Magazine: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2016; Available online: http://www.wwema.org (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Kalfas, D.; Giannarakis, G.; Paschalidou, M. Integration of Water Resources Management Strategies in Land Use Planning towards Environmental Conservation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezfooli, D.; Bolson, J.; Arabi, M.; Sukop, M.C.; Wiersema, I.; Millonig, S. A Qualitative Approach to Understand Transitions toward One Water in Urban Areas across North America. Water 2023, 15, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, A.N. One Water; Patris Newspaper: Iraklion, Greece, 2025; Available online: https://www.patris.gr/stiles/proektaseis/ena-nero/ (accessed on 21 June 2025). (In Greek)

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).