Pico-Hydropower and Cross-Flow Technology: Bibliometric Mapping of Scientific Research and Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

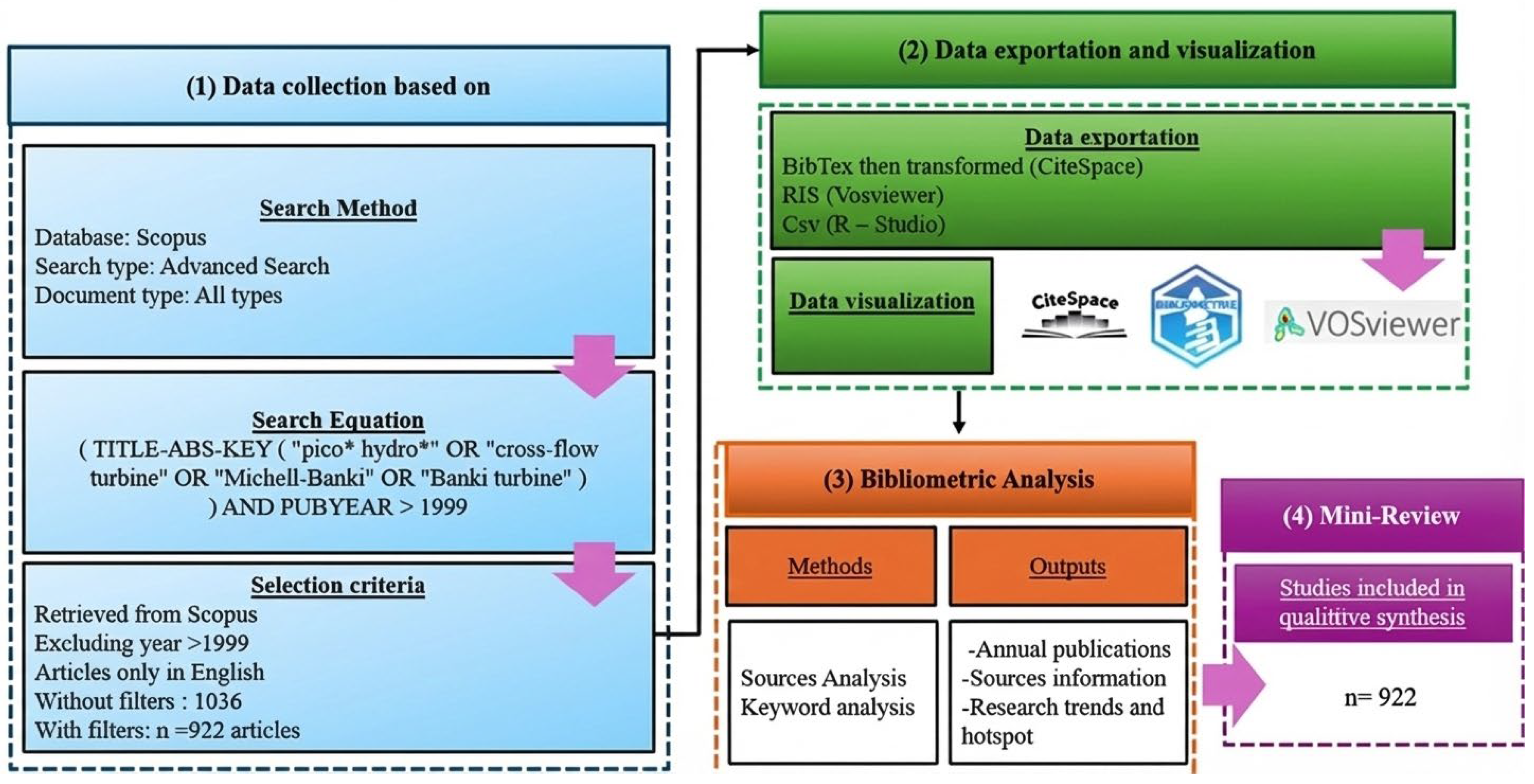

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

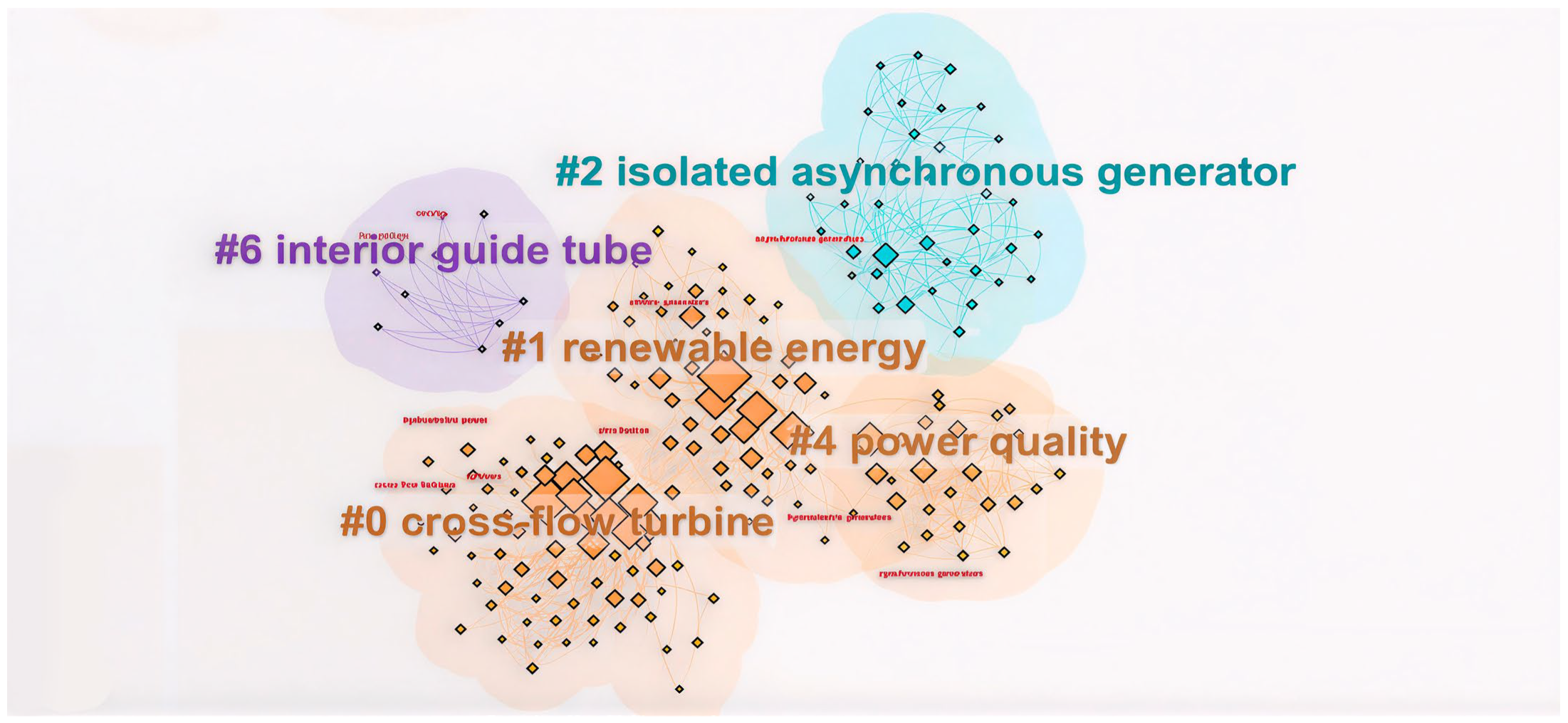

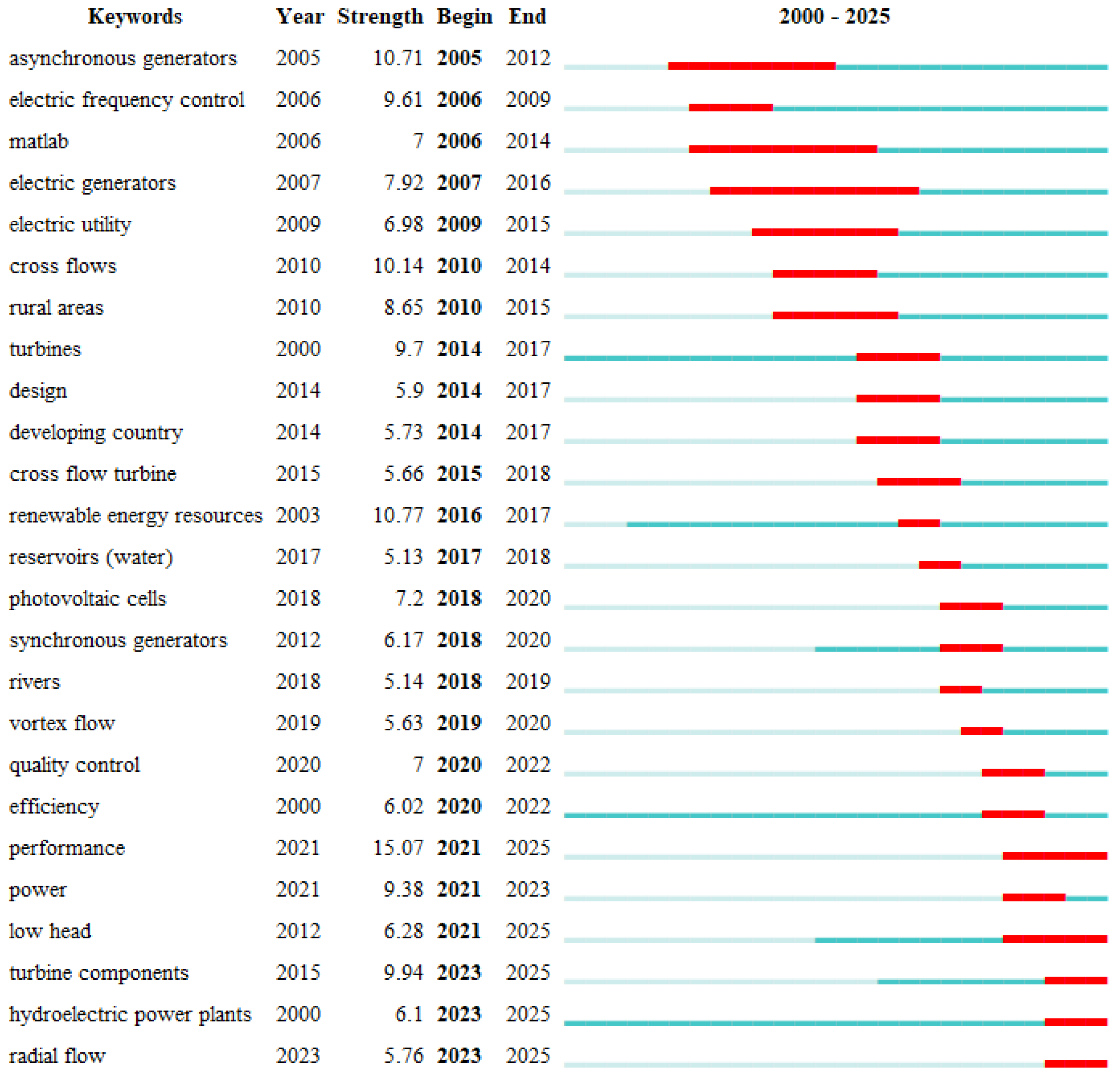

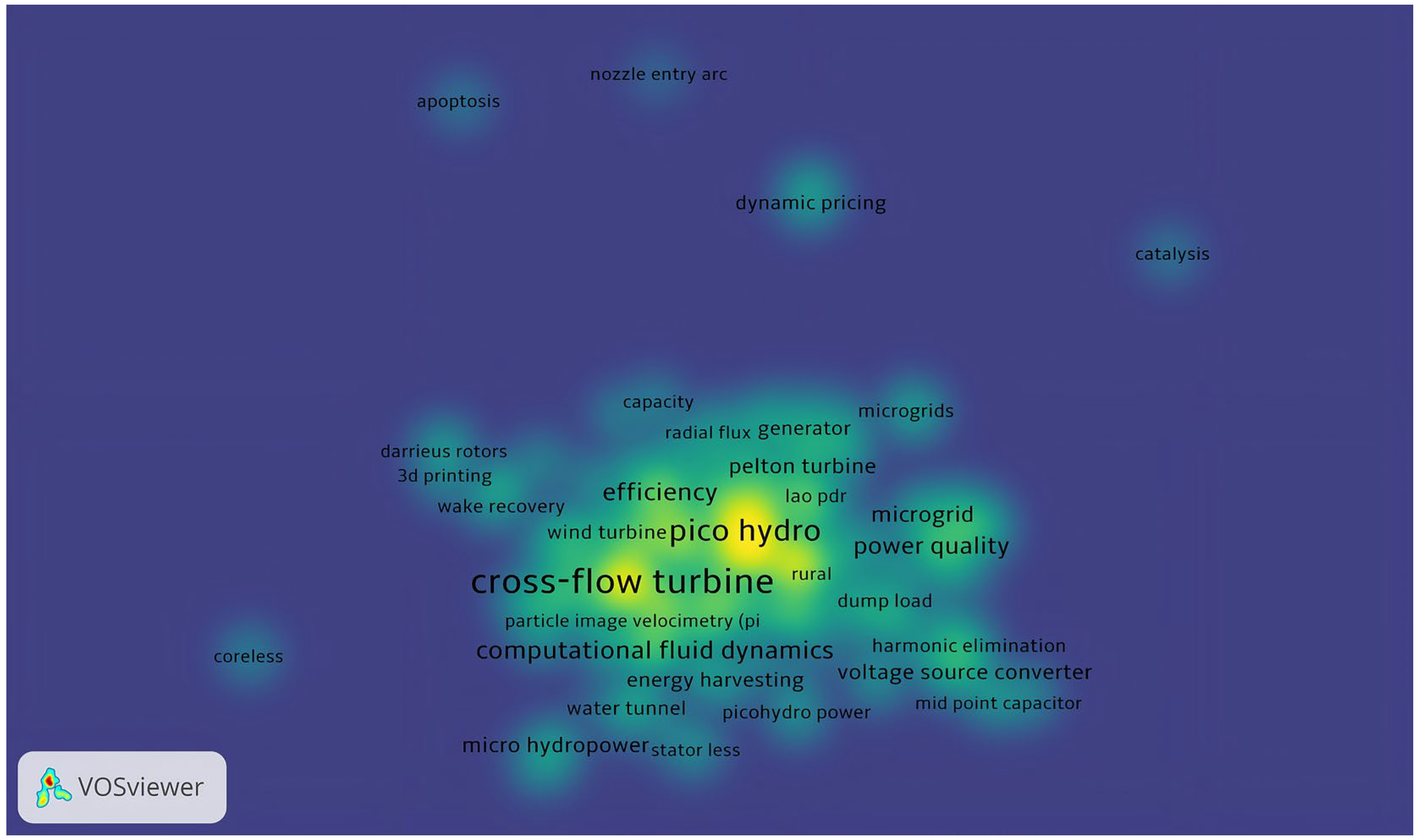

3.1. Keywords Analysis

3.2. Analysis of Sources and Documents

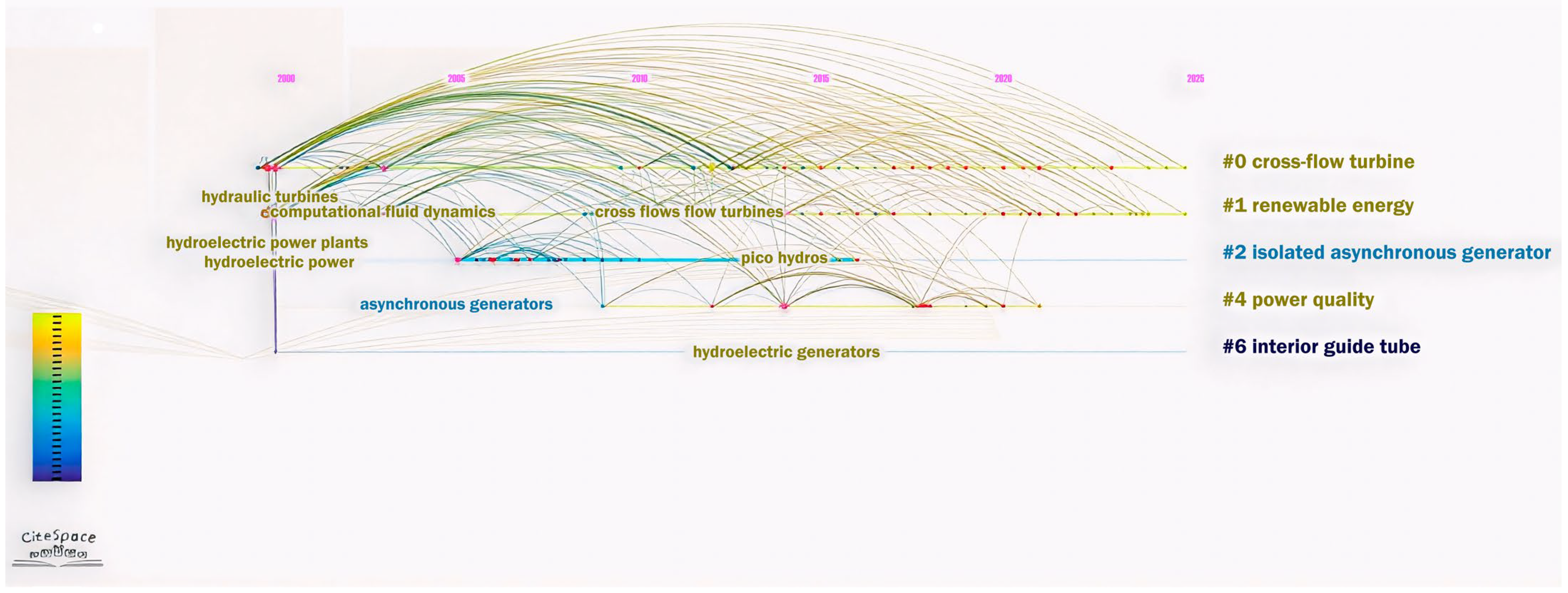

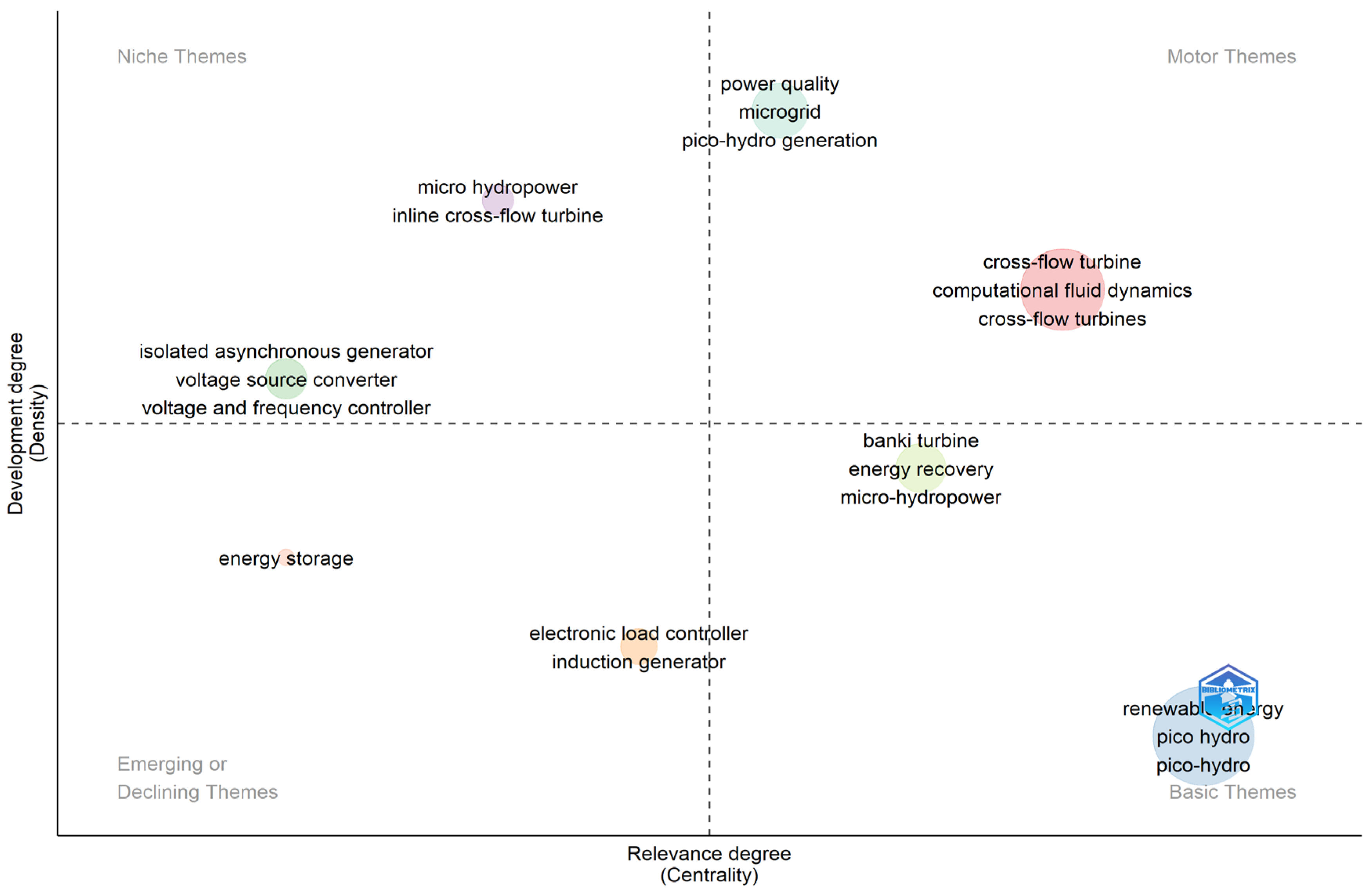

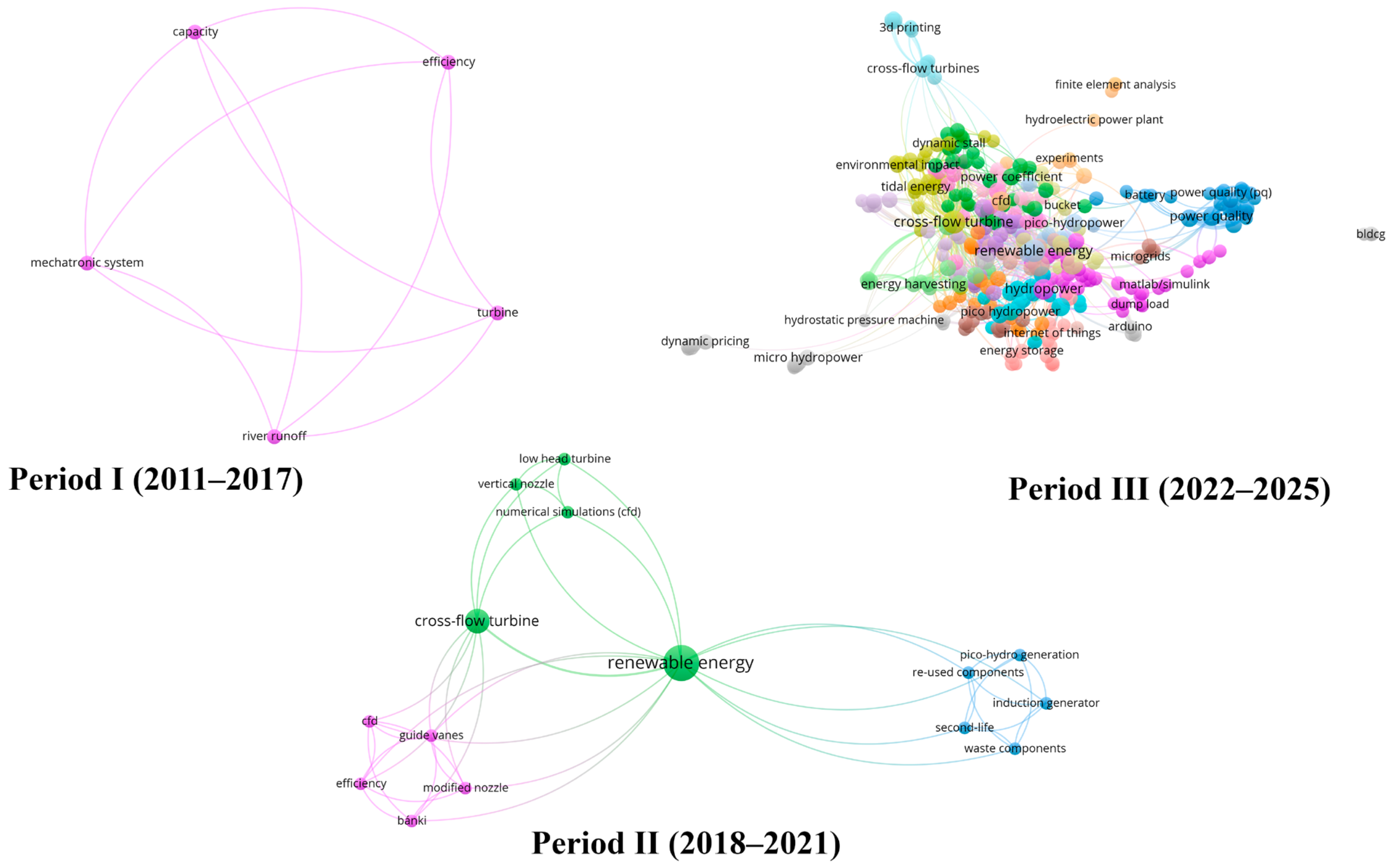

3.3. Conceptual Structure

3.4. Research Trends

4. Discussion

4.1. Dominant Research Lines

4.1.1. Geometric Optimization of the Turbine (Nozzle, Blades and Stages)

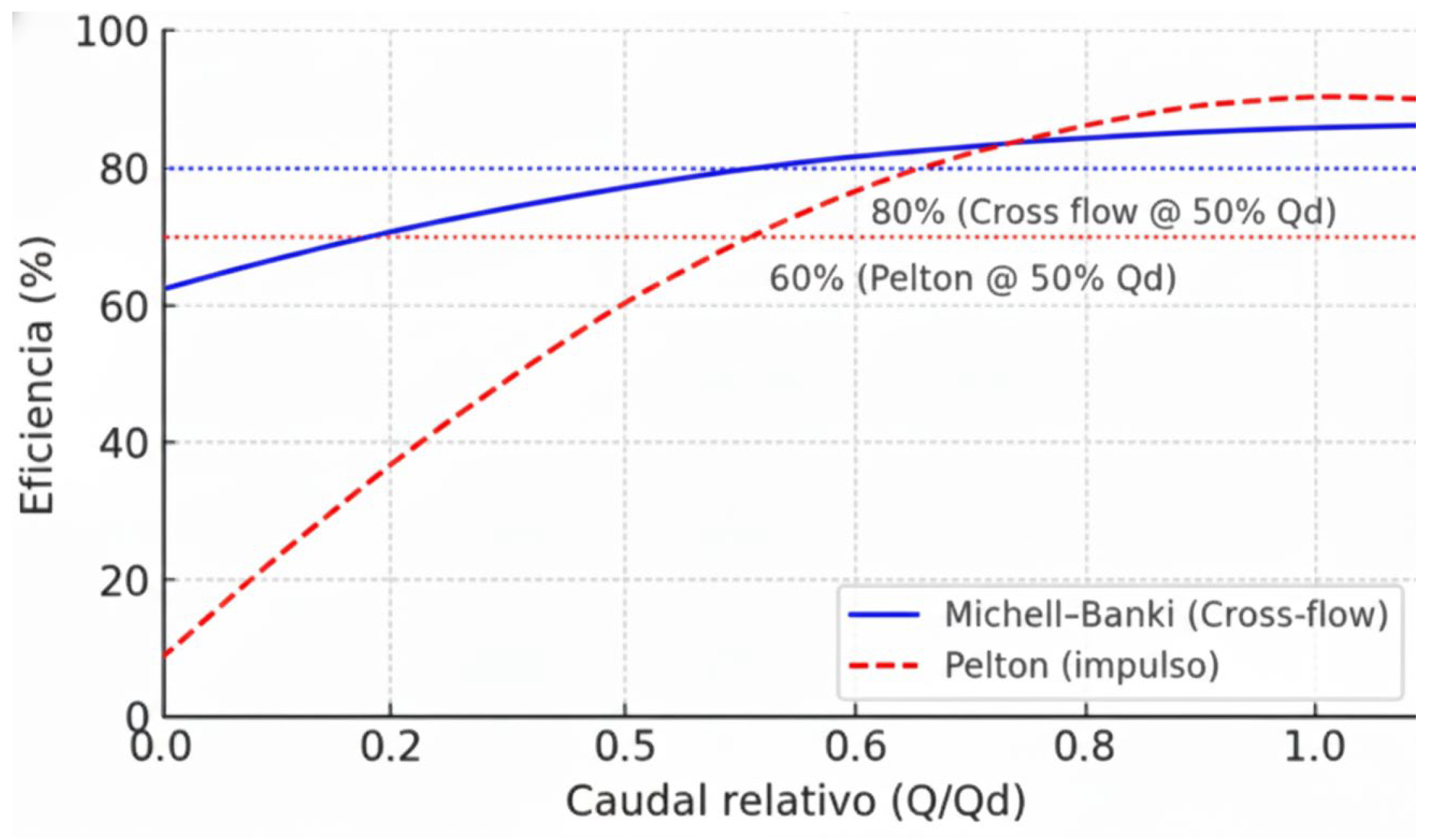

4.1.2. Hydraulic Parameters and Performance Curves (Head, Flow, Efficiency)

4.1.3. Socio-Economic Integration: Feasibility, Levelized Costs (LCOE) and Rural Applications

4.2. Gaps and Controversies

4.3. Technological Implications

4.4. Advanced Material and Coating Strategies for Pico-Hydro Turbines

4.5. Transfer to CAD/CAM Design and Local Manufacturing

4.6. Cavitation Phenomena in Michell–Banki (Cross-Flow) Turbines

4.7. Relevance for Andean Rural Electrification

4.8. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CAM | Computer-Aided Manufacturing |

| CDM | Clean Development Mechanism |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CNC | Computer Numerical Control |

| Q–H–η | Flow–Head–Efficiency performance curve |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Energy |

References

- UN. Ensure Access to Affordable, Reliable, Sustainable and Modern Energy. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/energy/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2020 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Sovacool, B.K. Deploying off-grid technology to eradicate energy poverty. Science 2012, 338, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monyei, C.G.; Jenkins, K.; Serestina, V.; Adewumi, A.O. Examining energy sufficiency and energy mobility in the global south through the energy justice framework. Energy Policy 2018, 119, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, A.; Olu-lawal, K.A.; Okoli, C.E.; Usman, F.O.; Usiagu, G.S. Sustainable energy solutions and climate change: A policy review of emerging trends and global responses. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, S.J.; Lubitz, W.D.; Williams, A.A.; Booker, J.D.; Butchers, J.P. Challenges facing the implementation of pico-hydropower technologies. J. Sustain. Res. 2019, 2, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, E.; Davies, P. Emerging and innovative materials for hydropower engineering applications: Turbines, bearings, sealing, dams and waterways, and ocean power. Engineering 2022, 8, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenevê, G.H. Design of a Small-Scale Pico-Hydro System Using Pumps as Turbines. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Politecnico de Braganca, Bragança, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Subedi, T.R.; Shakya, S.R.; Bhattarai, S. Innovations in Toroidal Propellers and Ultra-Low-Head Turbines: Applications, Performance, and Future Prospects. J. Eng. Issues Solut. 2025, 4, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.; Kauppert, K. Performance characteristics of water wheels. J. Hydraul. Res. 2004, 42, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, E.; Revelli, R. Gravity water wheels as a micro hydropower energy source: A review based on historic data, design methods, efficiencies and modern optimizations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 97, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzon, D.S.; Židonis, A.; Panagiotopoulos, A.; Petley, S.; Aggidis, G.A.; Anagnostopoulos, J.S.; Papantonis, D.E. Experimental Investigation and Analysis of Three Spear Valve Designs on the Performance of Turgo Impulse Turbines. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Audrius-Zidonis/publication/320517934_Experimental_investigation_and_analysis_of_three_spear_valve_designs_on_the_performance_of_Turgo_impulse_turbines/links/59e9a6050f7e9bc89bcad133/Experimental-investigation-and-analysis-of-three-spear-valve-designs-on-the-performance-of-Turgo-impulse-turbines.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Adhikari, R.; Wood, D. The design of high efficiency crossflow hydro turbines: A review and extension. Energies 2018, 11, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudsuansee, T.; Phitaksurachai, S.; Pan-Aram, R.; Sritrakul, N.; Tiapled, Y. Design and Hydrodynamic Performance of Low Head Propeller Hydro Turbine for Wide Range High Efficiency Operation. Int. J. Thermofluids 2025, 27, 101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Gu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wu, Y.; Yao, Z.; Mou, J. Improved prediction model of energy performance for variable-speed pumps-as-turbines (PATs) in micro-hydropower schemes. J. Energy Storage 2025, 120, 116388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.V.; Patel, R.N. Investigations on pump running in turbine mode: A review of the state-of-the-art. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 841–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschnigg, S.; Patauner, D.; Böhm, H.; Doujak, E.; Müller, C. Digitalization and hydropower integration in water supply systems: Unlocking energy potential, efficiency, and resilience. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 29, 101098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvis-Holguin, S.; Sierra-Del-Rio, J.; Hincapié-Zuluaga, D.; Chica-Arrieta, E. Numerical validation of a design methodology for cross-flow turbine type Michell-Banki. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua 2021, 12, 111–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, A. Design and Scaling of Cross-Flow Turbines in Variable Confinement. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sammartano, V.; Aricò, C.; Carravetta, A.; Fecarotta, O.; Tucciarelli, T. Banki-Michell optimal design by computational fluid dynamics testing and hydrodynamic analysis. Energies 2013, 6, 2362–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlehdar, M.; Yousefi, H.; Noorollahi, Y.; Mohammadi, M. Energy recovery from water distribution networks using micro hydropower: A case study in Iran. Energy 2022, 252, 124024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odou, O.D.T.; Bhandari, R.; Adamou, R. Hybrid off-grid renewable power system for sustainable rural electrification in Benin. Renew. Energy 2020, 145, 1266–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, E.; Perrier, J.P.; Revelli, R. Optimal design process of crossflow Banki turbines: Literature review and novel expeditious equations. Ocean Eng. 2022, 257, 111582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Gong, S.; Zu, H.; Guo, W. Multi-objective optimization study on the performance of double Darrieus hybrid vertical axis wind turbine based on DOE-RSM and MOPSO-MODM. Energy 2024, 299, 131406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprovitola, A.; Dyblenko, O.; Pezzella, G.; Viviani, A. Aerodynamic analysis of a supersonic transport aircraft at low and high speed flow conditions. Aerospace 2022, 9, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Крупа, Є.С.; Демчук, Є.О. Modern software for the numerical study of flow in hydraulic machines. In Bulletin of the National Technical University “KhPI”; Series: Hydraulic Machines and Hydraulic Units; NTU “KhPI” Publ.: Kharkiv, Ukraine, 2022; pp. 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bor, A.; Szabo-Meszaros, M.; Vereide, K.; Lia, L. Application of Three-Dimensional CFD Model to Determination of the Capacity of Existing Tyrolean Intake. Water 2024, 16, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimakopoulos, A.; Longo, D.; Robinson, D.; Goater, A.; Harris, J.; Wood, M.; Cuomo, G. Modelling engineering applications using OpenFOAM at the riverine, coastal and marine environment. In Proceedings of the 12th OpenFOAM Workshop, Exeter, UK, 24–27 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kusriantoko, P.; Daun, P.F.; Einarsrud, K.E. A comparative study of different CFD codes for fluidized beds. Dynamics 2024, 4, 475–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadoo, A.; Cruickshank, H. The role for low carbon electrification technologies in poverty reduction and climate change strategies: A focus on renewable energy mini-grids with case studies in Nepal, Peru and Kenya. Energy Policy 2012, 42, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyer, S.; White, T. Energy recovery in a commercial building using pico-hydropower turbines: An Australian case study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal, A.; Khattak, A. Performance evaluation of micro hydro power plant using cross flow turbines in Northern Pakistan. Int. J. Eng. Work. 2021, 8, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Yan, B.; Lubitz, W.D. Performance evaluation of cross-flow turbine for low head application. In Proceedings of the World Renewable Energy Congress, Linköping, Sweden, 8–13 May 2011; pp. 1394–1399. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.; Xu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, W.; Wu, R.; Lin, X.; Cai, Q.; Chiu, M.-C. Research Status and Future Agenda in Small Hydropower from the Perspective of Sustainable Development Goals. ACS ES&T Water 2024, 4, 2212–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Aburto, C.; Poma-García, J.; Montaño-Pisfil, J.; Morcillo-Valdivia, P.; Oyanguren-Ramirez, F.; Santos-Mejia, C.; Rodriguez-Flores, R.; Virú-Vasquez, P.; Pilco-Nuñez, A. Bibliometric Analysis of Global Publications on Management, Trends, Energy, and the Innovation Impact of Green Hydrogen Production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achebe, C.H.; Okafor, O.C.; Obika, E.N. Design and implementation of a crossflow turbine for Pico hydropower electricity generation. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awandu, W.; Ruff, R.; Wiesemann, J.-U.; Lehmann, B. Status of micro-hydrokinetic river technology turbines application for rural electrification in Africa. Energies 2022, 15, 9004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahimer, A.A.; Alghoul, M.A.; Sopian, K.; Amin, N.; Asim, N.; Fadhel, M.I. Research and development aspects of pico-hydro power. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 5861–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Yang, H.; Guo, X.; Lou, C.; Shen, Z.; Chen, J.; Du, J. Development of inline hydroelectric generation system from municipal water pipelines. Energy 2018, 144, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Yan, B. Design of a low head pico hydro turbine for rural electrification in Cameroon. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eskin, D. On CFD-Assisted Research and Design in Engineering. Energies 2022, 15, 9233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Feng, Z. Numerical simulation on the effect of jet nozzle position on impingement cooling of gas turbine blade leading edge. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2011, 54, 4949–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, E.Y.; Tesfay, A.H. Effect of Blade Profile on Flow Characteristics and Efficiency of Cross-Flow Turbines. Energies 2025, 18, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Mirzamoghadam, A.V. Single vs. Two Stage High Pressure Turbine Design of Modern Aero Engines; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 78583. [Google Scholar]

- De Andrade, J.; Curiel, C.; Kenyery, F.; Aguillón, O.; Vásquez, A.; Asuaje, M. Numerical investigation of the internal flow in a Banki turbine. Int. J. Rotating Mach. 2011, 2011, 841214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldemariam, E.T.; Lemu, H.G.; Wang, G.G. CFD-driven valve shape optimization for performance improvement of a micro cross-flow turbine. Energies 2018, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, W.R. Small Michell (Banki) Turbine: A Construction Manual; Volunteers in Technical Assistance: Arlington, VA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Moreno, D.; Romero-Menco, F.; Velásquez-García, L.I.; Rubio-Clemente, A.; Chica, E. Recomendaciones para la realización y análisis de pruebas experimentales en turbinas hidráulicas tipo Michell-Banki. Rev. UIS Ing. 2024, 23, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiuzat, A.A.; Akerkar, B.P. Power outputs of two stages of cross-flow turbine. J. Energy Eng. 1991, 117, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, M.; Jorge, R. Optimización de los Factores de Operación para Mejorar el Rendimiento de la Pico Turbina Michell–Banki. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional del Centro del Perú, Huancayo, Peru, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire, A.; Dahal, D.R.; Pokharel, N.; Chitrakar, S.; Thapa, B.S.; Thapa, B. Opportunities and challenges of introducing Francis turbine in Nepalese micro hydropower projects. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; p. 12007. [Google Scholar]

- Cerquera, M.S.A.; Parada, M.M.Á.; Palmeth, L.H.M.; Marín, J.G.A.; Vargas, J.C.A. Evaluation of the influence of the number of blades on a Michell Banki turbine on the power generated under given flow and head conditions. EUREKA Phys. Eng. 2025, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, L.S.; Restrepo, J.D.P.; Hernández, C.M. Construction and Performance Evaluation of a Michell-Banki Turbine Prototype. In Proceedings of the First LACCEI International Symposium on Mega and Micro Sustainable Energy Projects, Cancún, Mexico, 15 August 2013; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Zdrojewski, W. Measuring Stand Tests of a Michell-Banki Waterturbine Prototype, Performedunder Natural Conditions. Pr. Inst. Lotnictwa 2018, 2, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve-Cifuentes, O.D.; Vélez-García, S.; Sanín-Villa, D.; Revuelta-Acosta, J.D. Fluid-Structure Numerical Study of an In-Pipe Axial Turbine with Circular Blades. Energies 2024, 17, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, R.C.; Wood, D.H. A new nozzle design methodology for high efficiency crossflow hydro turbines. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2017, 41, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, E.R.; Kishore, T.S.; Haghighi, A.T. Levelized cost of electricity generation by small hydropower projects under clean development mechanism in India. Energies 2022, 15, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temesgen, A.L.; Bekele, G. GIS-based assessment of economically feasible off-grid mini-grids in Ethiopia. Discov. Energy 2025, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irena, W. Hydropower; Renewable Energy Technologies: Cost Analysis Series; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2012; Volume 44. [Google Scholar]

- SCS. Turbines. Available online: https://www.sustainablecontrol.com/sustainablelive/Products/TurbinesAndGenerators.html#:~:text=The turbines supplied by SCS,UK and have 30%2B Installations (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Gurung, A.; Bryceson, I.; Joo, J.H.; Oh, S.-E. Socio-economic impacts of a micro-hydropower plant on rural livelihoods. Sci. Res. Essays 2011, 6, 3964–3972. [Google Scholar]

- de Brito, R.B.; Santos, B.R.; Alexandrino, C.H.; Ferreira, T.A.A. Use of rainwater and water supply to produce electrical energy for homes. Obs. Econ. Latinoam. 2024, 22, e8145. [Google Scholar]

- Svrkota, D.; Tašin, S.; Stamenković, Ž. Transient-state analysis of hydropower plants with cross-flow turbines. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2022, 14, 16878132221098836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.J.W.; Fox, E.L.B. A review of small hydropower performance and cost. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-López, E.; Matitos-Montoya, V.; Marrero, M. Rehabilitation or Demolition of Small Hydropower Plants: Evaluation of the Environmental and Economic Sustainability of the Case Study” El Cerrajón”. Environments 2024, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penche, C. Layman’s Guidebook on How to Develop a Small Hydro Site; DG XVII; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, B.; Maley, J.; Parton, K.; Morrison, M. Factors influencing the sustainability of micro-hydro schemes in Nepal. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, M.A.; Sudjono, P.; Sato, T.; Onda, N.; Endo, I.; Takada, A.; Muntalif, B.S.; Ide, J. Assessing the sustainable development of micro-hydro power plants in an isolated traditional village west java, indonesia. Energies 2021, 14, 6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinagra, M.; Creaco, E.; Morreale, G.; Tucciarelli, T. Energy recovery optimization by means of a turbine in a pressure regulation node of a real water network through a data-driven digital twin. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37, 4733–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Menco, F.; Pineda-Aguirre, J.; Velásquez, L.; Rubio-Clemente, A.; Chica, E. Effects of the Nozzle Configuration with and without an Internal Guide Vane on the Efficiency in Cross-Flow Small Hydro Turbines. Processes 2024, 12, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, T.; Irazusta, B.; Reyna, S.; Labaque, M.; Riha, C. Development of micro hydro turbines as renewable energy applications for educational purposes. In Proceedings of the 38th IAHR World Congress, Panama City, Panama, 1–6 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Elbatran, A.H.; Yaakob, O.B.; Ahmed, Y.M.; Shehata, A.S. Numerical and experimental investigations on efficient design and performance of hydrokinetic Banki cross flow turbine for rural areas. Ocean Eng. 2018, 159, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capera, F.S.; Marín, J.G.A.; Sandoval, C.C. Numerical Study of the Opening Angle Incidence in Michell-Banki Turbine’s Performance without Guide Blades. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. 2023, 67, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, T.; Thakur, R.; Ngo, G.H.; Lee, D.; Fekete, G.; Kumar, R.; Singh, T. Silt erosion and cavitation impact on hydraulic turbines performance: An in-depth analysis and preventative strategies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ge, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Li, G.; Zheng, Y. Research on synergistic erosion by cavitation and sediment: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 95, 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butchers, J.; Williamson, S.; Booker, J.; Tran, A.; Karki, P.B.; Gautam, B. Understanding sustainable operation of micro-hydropower: A field study in Nepal. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2020, 57, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasore, G.; Ahlborg, H.; Ntagwirumugara, E.; Zimmerle, D. Progress for on-grid renewable energy systems: Identification of sustainability factors for small-scale hydropower in rwanda. Energies 2021, 14, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza Kashyzadeh, K.; Ridha, W.K.M.; Ghorbani, S. The influence of nanocoatings on the wear, corrosion, and erosion properties of AISI 304 and AISI 316L stainless steels: A critical review regarding hydro turbines. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2025, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.G.; Chen, D.R.; Liang, P. Enhancement of cavitation erosion resistance of 316 L stainless steel by adding molybdenum. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 35, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, R.; Xiang, J.; Hou, D. Characteristics of mechanical properties and microstructure for 316L austenitic stainless steel. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2011, 18, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Qin, Y.; Lin, J. Ultrasonic cavitation erosion of high-velocity oxygen-fuel (HVOF) sprayed near-nanostructured WC–10Co–4Cr coating in NaCl solution. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 26, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Singh, V.; Singla, A.K.; Bansal, A.; Singla, J.; Goyal, D.K. Cavitation Erosion Investigations of Hard Carbide and Nitride Based Novel Coatings Manufactured by Plasma Spraying. Tribol. Trans. 2024, 67, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhilkashinova, A.; Abilev, M.; Zhilkashinova, A. Microplasma-sprayed V2O5/C double-layer coating for the parts of mini-hydropower systems. Coatings 2020, 10, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.H.; Cheng, F.T.; Kwok, C.T.; Man, H.C. Improvement of cavitation erosion resistance of AISI 316 stainless steel by laser surface alloying using fine WC powder. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 165, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, S. Research Progress of Laser Cladding Coating on Titanium Alloy Surface. Coatings 2024, 14, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, R.C.; Vaz, J.; Wood, D. Cavitation inception in crossflow hydro turbines. Energies 2016, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirojuddin, S.; Wardhana, L.K.; Kholil, A. Investigation of the draft tube variations against the first stage and the second stage flow of banki turbine. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; p. 62077. [Google Scholar]

- Maître, T.; Pellone, C.; Sansone, E. Cavitating flow modeling in a cross-flow turbine. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Ocean Energy (ICOE 2008), Brest, France, 15–17 October 2008; pp. 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, E.; Pellone, C.; Maître, T. Modeling the unsteady cavitating flow in a cross-flow water turbine. J. Fluids Eng. 2010, 132, 071302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrope, H.A.; Chande Jande, Y.A.; Kivevele, T.T. A review on computational fluid dynamics applications in the design and optimization of crossflow hydro turbines. J. Renew. Energy 2021, 2021, 5570848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, H.; Sasso, J. Proyectos hídricos y ecología política del desarrollo en Latinoamérica: Hacia un marco analítico. In European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies/Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe; CEDLA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Butchers, J.; Williamson, S.; Booker, J.; Pradhan, S.R.; Karki, P.B.; Gautam, B.; Pradhan, B.R.; Sapkota, P. A Methodology for Renovation of Micro-Hydropower Plants: A Case Study Using a Turgo Turbine in Nepal. J. Sustain. Res. 2023, 5, e230015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khennas, S.; Barnett, A. Best Practices for Sustainable Development of Micro-Hydro Power in Developing Countries. UK. 2000. Available online: http://reca-corp.com/files/57897266.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Nouni, M.R.; Mullick, S.C.; Kandpal, T.C. Techno-economics of micro-hydro projects for decentralized power supply in India. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyissa, E.A.; Tibba, G.S.; Binchebo, T.L.; Bekele, E.A.; Kole, A.T. Energy potential assessment and techno–economic analysis of micro hydro–photovoltaic hybrid system in Goda Warke village, Ethiopia. Clean Energy 2024, 8, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iweh, C.D.; Semassou, G.C.; Ahouansou, R.H. Optimization of a Hybrid Off-Grid Solar PV—Hydro Power Systems for Rural Electrification in Cameroon. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2024, 2024, 4199455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahputra, R.; Soesanti, I. Planning of Hybrid Micro-Hydro and Solar Photovoltaic Systems for Rural Areas of Central Java, Indonesia. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2020, 2020, 5972342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsengimana, C.; Han, X.T.; Li, L. Comparative Analysis of Reliable, Feasible, and Low-Cost Photovoltaic Microgrid for a Residential Load in Rwanda. Int. J. Photoenergy 2020, 2020, 8855477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-C.; Hagumimana, N.; Zheng, J.; Asemota, G.N.O.; Niyonteze, J.D.D.; Nsengiyumva, W.; Nduwamungu, A.; Bimenyimana, S. Standalone and minigrid-connected solar energy systems for rural application in Rwanda: An in situ study. Int. J. Photoenergy 2021, 2021, 1211953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias Rodas, C.A.; de Paz, P.L.; Lastres Danguillecourt, O.; Ibáñez Duharte, G. Analysis and optimization to a test bench for Micro-hydro-generation. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sources | h-Index | g-Index | m-Index | TC | NP | PY-Start |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renewable Energy | 23 | 42 | 1 | 1891 | 58 | 2003 |

| Energy Procedia | 9 | 13 | 0.818 | 262 | 13 | 2015 |

| Ocean Engineering | 9 | 9 | 0.75 | 163 | 9 | 2014 |

| Journal of Advanced Research in Fluid Mechanics and Thermal Sciences | 8 | 13 | 1 | 204 | 26 | 2018 |

| International Journal of Marine Energy | 7 | 7 | 0.636 | 106 | 7 | 2015 |

| Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy | 7 | 11 | 0.7 | 164 | 11 | 2016 |

| Water (Switzerland) | 7 | 8 | 0.778 | 155 | 8 | 2017 |

| CFD Letters | 6 | 9 | 0.75 | 119 | 9 | 2018 |

| Energies | 6 | 13 | 0.462 | 339 | 13 | 2013 |

| Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews | 6 | 7 | 0.316 | 358 | 7 | 2007 |

| References | Research Gap | Analytical Implication | Solution Strategy | Key Studies/Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [64] | Lack of comparable Q–H–η curves | The lack of normalized hill charts makes it difficult to compare dice, calibrate CFDs, and extrapolate performance across scales; it leads to oversizing and efficiency losses. | Unified testing protocols and open data repositories; parametric metamodels for generating standard curves from a few experimental points. | Database of 270 plants compiled by Svrkotaetal as an initial attempt at synthesis. |

| [65,66] | Economic Analysis Sub-Report (LCOE) | Without energy cost metrics, technical results lack context: policy and financing decisions are based on conjecture. | Integrate LCOE/IRR templates into articles and design software; editorial requirement to include a minimum techno-economic evaluation. | Klein & Fox’s review shows dispersion of LCOE (0.02–0.30 USD/kWh) and lack of homogeneous data. |

| [67] | Poor validation at altitudes >3000 m | The real-world performance of these systems in the Andes and Himalayas is still uncertain, as reduced atmospheric pressure can affect cavitation and net head, posing risks of unforeseen failures and escalated costs. | Portable test benches and in situ monitoring campaigns; altitude correction factors in design guides. | ESHA manuals warn of suction lift reduction, but dedicated testing on Banki turbines is lacking. |

| [68,69] | Lack of post-installation sustainability analysis | Without follow-up of ≥5 years, the true failure rates, community management, and social returns are unknown; projects can collapse without registration. | Periodic technical audits + socio-productive surveys; case banks with lessons learned to inform design and policies. | A longitudinal study by Poudeletal identifies 30% of plants inoperative due to a lack of spare parts and training. |

| [70,71] | Limited integration of IoT, digital twin and ML | Lack of sensor technology and predictive models limits real-time optimization, preventive maintenance, and collective learning; Industry 4.0 is underutilized. | Implement low-cost sensors, lightweight SCADA, and digital twins; train ML algorithms for predictive maintenance and adaptive control. | Sinagraetal created a digital twin for cross-flow turbine valves; still scarce in pico hydro. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanchez-Cortez, L.; Salvador-Gutierrez, B.; Pantoja-Carhuavilca, H.; Tinoco-Gomez, O.; Montaño-Pisfil, J.; Chávez-Sánchez, W.; Gutiérrez-Tirado, R.; Poma-García, J.; Santos-Mejia, C.; Vara-Sanchez, J. Pico-Hydropower and Cross-Flow Technology: Bibliometric Mapping of Scientific Research and Review. Water 2025, 17, 3524. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243524

Sanchez-Cortez L, Salvador-Gutierrez B, Pantoja-Carhuavilca H, Tinoco-Gomez O, Montaño-Pisfil J, Chávez-Sánchez W, Gutiérrez-Tirado R, Poma-García J, Santos-Mejia C, Vara-Sanchez J. Pico-Hydropower and Cross-Flow Technology: Bibliometric Mapping of Scientific Research and Review. Water. 2025; 17(24):3524. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243524

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanchez-Cortez, Lozano, Beatriz Salvador-Gutierrez, Hermes Pantoja-Carhuavilca, Oscar Tinoco-Gomez, Jorge Montaño-Pisfil, Wilmer Chávez-Sánchez, Ricardo Gutiérrez-Tirado, José Poma-García, Cesar Santos-Mejia, and Jesús Vara-Sanchez. 2025. "Pico-Hydropower and Cross-Flow Technology: Bibliometric Mapping of Scientific Research and Review" Water 17, no. 24: 3524. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243524

APA StyleSanchez-Cortez, L., Salvador-Gutierrez, B., Pantoja-Carhuavilca, H., Tinoco-Gomez, O., Montaño-Pisfil, J., Chávez-Sánchez, W., Gutiérrez-Tirado, R., Poma-García, J., Santos-Mejia, C., & Vara-Sanchez, J. (2025). Pico-Hydropower and Cross-Flow Technology: Bibliometric Mapping of Scientific Research and Review. Water, 17(24), 3524. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243524